Introduction

Biodiversity conservation, as a social, political and normative endeavour, has a strong foundation in the sciences. The ‘synthetic’ discipline of conservation biology was originally conceived to provide ‘principles and tools for preserving biological diversity’ (Soulé Reference Soulé1985). Since then, what is now more commonly known as ‘conservation science’ (Kareiva & Marvier Reference Kareiva and Marvier2012) has broadened and diversified to draw on many more fields of research, most notably from the social sciences and humanities (Sandbrook et al. Reference Sandbrook, Adams, Büscher and Vira2013, Moon & Blackman Reference Moon and Blackman2014, Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Roth, Klain, Chan, Christie and Clark2017). Despite considerable changes in the framing and narratives of conservation (Louder & Wyborn Reference Louder and Wyborn2020), its key ideas and the relative dominance of particular scientific approaches over time (Mace Reference Mace2014), the importance of science has remained deeply entrenched within the mainstream conservation community. Indeed, the vast majority of conservationists agree that conservation goals should be based on science (Sandbrook et al. Reference Sandbrook, Fisher, Holmes, Luque-Lora and Keane2019).

Science has provided unequivocal evidence of the impacts of human activities on biodiversity (Godet & Devictor Reference Godet and Devictor2018, Mace et al. Reference Mace, Barrett, Burgess, Cornell, Freeman, Grooten and Purvis2018). An estimated 1 million species of terrestrial, freshwater and marine plants and animals (vertebrate and invertebrate) are threatened with extinction, with an average of c. 25% of species at risk of extinction within each of these taxonomic groups. Nature’s contributions to people (Díaz et al. Reference Díaz, Pascual, Stenseke, Martín-López, Watson and Molnár2018) have similarly declined globally over the past 50 years (Díaz et al. Reference Díaz, Settele, Brondízio, Ngo, Agard and Arneth2019, IPBES Reference Díaz, Settele, Brondízio, Ngo, Guèze and Agard2019). Science has also showed that conservation investments and measures implemented to date have not yet translated into a reversal of global biodiversity decline (Hoffmann et al. Reference Hoffmann, Hilton-Taylor, Angulo, Böhm, Brooks and Butchart2010, Waldron et al. Reference Waldron, Miller, Redding, Mooers, Kuhn and Nibbelink2017, Bolam et al. Reference Bolam, Mair, Angelico, Brooks, Burgman and Hermes2021), threatening the likelihood of achieving the Aichi Targets under the Convention on Biological Diversity and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Díaz et al. Reference Díaz, Settele, Brondízio, Ngo, Agard and Arneth2019, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity 2020).

Despite an abundance of scientific evidence that biodiversity loss is a clear, worsening and pervasive global problem, humanity’s collective response to this crisis has been insufficient. It is this apparent paradox that the Biodiversity Revisited initiative has sought to interrogate through deep, creative reflection on the constructs of ‘biodiversity’ itself (Wyborn et al. Reference Wyborn, Davila, Pereira, Lim, Alvarez and Henderson2020a, Reference Wyborn, Kalas and Rust2020b). The science underpinning biodiversity is one of several themes that Biodiversity Revisited aimed to critically examine, alongside narratives (Louder & Wyborn Reference Louder and Wyborn2020), systems (Davila et al. Reference Davila, Plant and Jacobs2021), governance and futures (Wyborn et al. Reference Wyborn, Louder, Harfoot and Hill2021a). Scientific knowledge, actors and institutions are but small components of global systems that must be transformed to reverse biodiversity loss (IPBES Reference Díaz, Settele, Brondízio, Ngo, Guèze and Agard2019), yet they are far more within the control of the conservation science community than powerful global economic, social and political factors. It is this spirit of self-reflection, humility and curiosity that has motivated the Biodiversity Revisited process and its collective outputs (Wyborn et al. Reference Wyborn, Davila, Pereira, Lim, Alvarez and Henderson2020a, Reference Wyborn, Kalas and Rust2020b, Reference Wyborn, Montana, Kalas, Clement, Cisneros and Knowles2021b).

This review aims to critically examine the science of biodiversity conservation. Specifically, this review seeks to identify any hidden assumptions that, once interrogated and explored, may assist in improving conservation science, policy and practice. It does so by examining historical trends in the conservation science literature with respect to its major themes, frames and dominant philosophies. It also considers how the goal(s) and role(s) of conservation science have been conceptualized over time and how these terms may be more consistently defined in future. As the conservation science community frequently engages in debate over its approaches and efficacy, numerous detailed literature reviews (Table 1) and critical commentaries already exist. Rather than conduct another comprehensive or systematic analysis of the conservation science literature, this review is purposely selective and considers existing reviews and seminal works to explore major themes and identify potential gaps. Such an iterative and reflexive scoping review approach is appropriate in this context given this review’s aims to identify knowledge gaps, examine how existing research has been conducted and clarify terminology (Arksey & O’Malley Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005, Munn et al. Reference Munn, Peters, Stern, Tufanaru, McArthur and Aromataris2018).

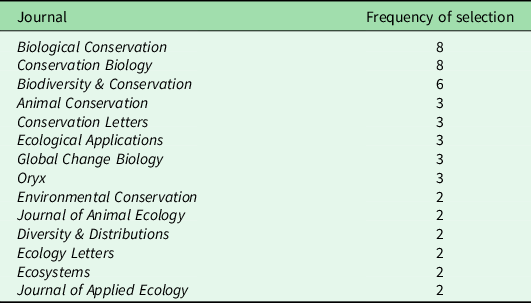

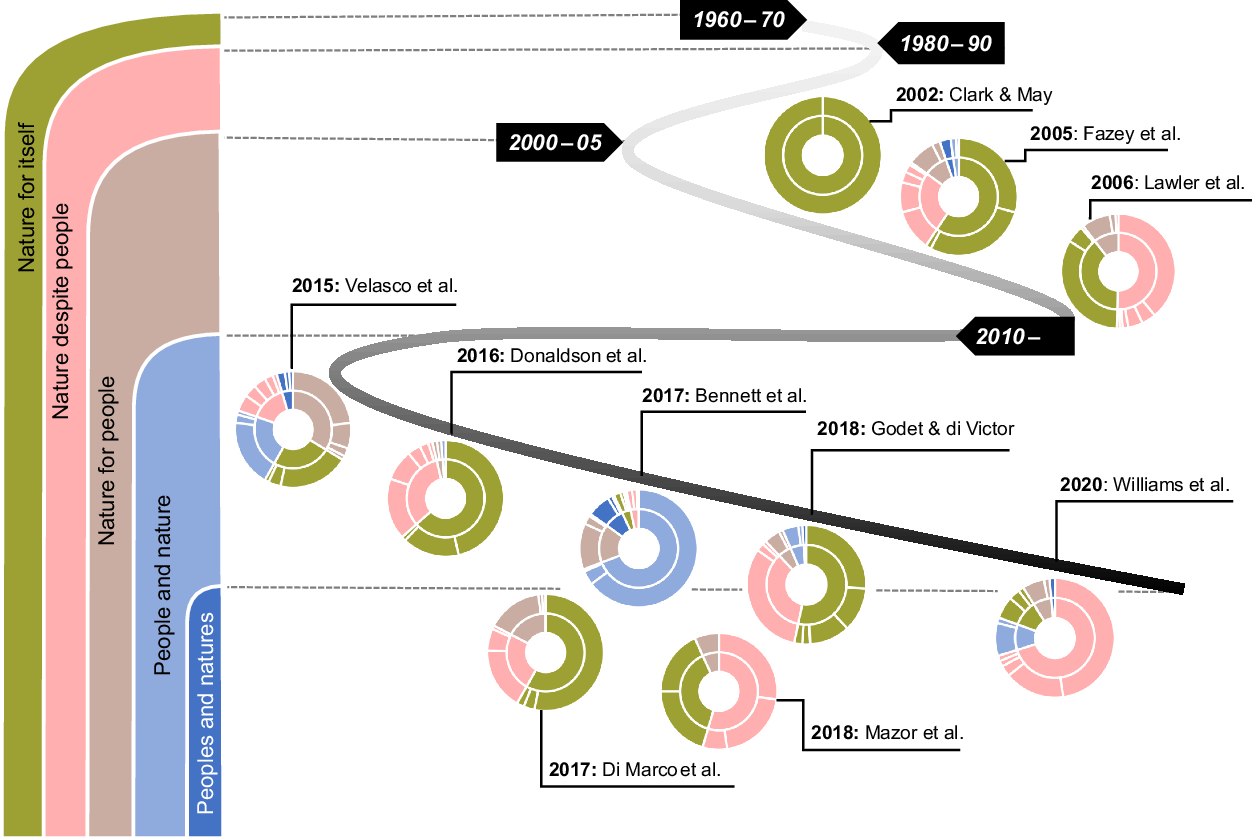

Table 1. Existing reviews of the conservation science literature, including their stated aims and how their findings are organized. Reviews were identified through a literature search and by cross-examining reference lists (most reviews cited previous review articles). Reviews were selected for consideration in this scoping review if they: (1) aimed to review the conservation science literature; and (2) conducted a systematic review or examined a representative sample of the literature. Bennett et al. (Reference Bennett, Roth, Klain, Chan, Christie and Clark2017) does not neatly fit these criteria, but it is included here for the sake of completeness since no other review article has specifically focused on the conservation social sciences. Narrative reviews (e.g., Meine et al. Reference Meine, Soule and Noss2006) and opinion pieces (e.g., Doak et al. Reference Doak, Bakker, Goldstein and Hale2014) were not selected for detailed analysis, but are drawn on elsewhere in this review.

In the first section, the present review describes major themes of the conservation science literature, including its conceptualization as a crisis discipline and historical trends in conservation priorities. Next, existing reviews of the conservation science literature (Table 1) are examined in greater detail by considering their stated aims and findings in the context of the four main historical phases in the framing of conservation (Mace Reference Mace2014). A quantitative content analysis of key terms identified by Mace (Reference Mace2014) is used to showcase the emergence and relative dominance of these four framings and to explore how conservation science as a whole has been conceptualized over time. This review then interrogates how the goal(s) and role(s) of conservation science have previously been described in the literature and proposes a simple framework that may assist in re-conceptualizing the role(s) of science in biodiversity conservation for the benefit of conservation science, policy and practice. This review concludes with a discussion of emerging trends and suggestions for the future.

Science for a global crisis

Conservation science has been characterized by crisis and urgency since its inception (Soulé Reference Soulé1985, Reference Soulé1991, Meine et al. Reference Meine, Soule and Noss2006), given the sheer scale and complexity of the world’s conservation challenges and the rate at which biodiversity is being eroded. Biodiversity itself, encompassing the genes, species and ecosystems that make up life on Earth, is an incredibly fertile area for scientific research, irrespective of the conservation crisis. The collective knowledge of biodiversity has exponentially expanded over the past 50 years (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Zhang and Hong2011), yet it remains woefully incomplete. For example, most of the estimated 8.7 million species in existence worldwide have yet to be described (Mora et al. Reference Mora, Tittensor, Adl, Simpson and Worm2011, Pimm et al. Reference Pimm, Jenkins, Abell, Brooks, Gittleman and Joppa2014). Which components – and what amount – of biodiversity need to be maintained in order to avoid dangerous feedbacks at the ecosystem and planetary scales, and whether it is possible to detect such thresholds in time is also not fully understood (Mace et al. Reference Mace, Reyers, Alkemade, Biggs, Chapin and Cornell2014, Knapp Reference Knapp, Reid, Fernández-Giménez, Klein and Galvin2019).

Science has also provided evidence that conservation efforts, such as protected area expansion (Butchart et al. Reference Butchart, Clarke, Smith, Sykes, Scharlemann and Harfoot2015, Visconti et al. Reference Visconti, Butchart, Brooks, Langhammer, Marnewick and Vergara2019), have contributed to slowing some species extinction trends (Hoffmann et al. Reference Hoffmann, Hilton-Taylor, Angulo, Böhm, Brooks and Butchart2010, Bolam et al. Reference Bolam, Mair, Angelico, Brooks, Burgman and Hermes2021). It is clear that investment in conservation reduces biodiversity loss and existing global conservation funding is wholly inadequate (McCarthy et al. Reference McCarthy, Donald, Scharlemann, Buchanan, Balmford and Green2012, Waldron et al. Reference Waldron, Miller, Redding, Mooers, Kuhn and Nibbelink2017). Yet the conservation community is still learning what interventions and governance systems are most effective for maintaining different aspects of biodiversity over a range of socio-political and landscape contexts (Miteva et al. Reference Miteva, Pattanayak and Ferraro2012, Sutherland et al. Reference Sutherland, Ockendon, Smith and Dicks2015, Godet & Devictor Reference Godet and Devictor2018). The questions and answers that science might uncover about biodiversity and its conservation are arguably limitless, but the resources and time available to do so are not. This juxtaposition has underpinned repeated calls within the literature to prioritize conservation research and action on particular geographical locations, threatening processes or components of biodiversity.

What is a conservation priority?

What is, and is not, regarded as a conservation priority is highly contested and has changed considerably over time as conservation itself has evolved (Marris Reference Marris2007, Game et al. Reference Game, Kareiva and Possingham2013, Mace Reference Mace2014). Conservation prioritization is arguably one of the most prominent and influential themes in the literature, with the global ‘hotspots’ analysis by Myers et al. (Reference Myers, Mittermeier, Mittermeier, da Fonseca and Kent2000) being the best-known example (Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Baquero, da Fonseca, Gerlach, Hoffmann and Lamoreux2006). The growth of conservation decision science (Moilanen et al. Reference Moilanen, Wilson and Possingham2009, Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Carwardine and Possingham2009, Game et al. Reference Game, Kareiva and Possingham2013) occurred partly in response to this proliferation of global priority maps in an effort to support the identification of conservation priorities more objectively, transparently and cost-effectively (Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, McBride, Bode and Possingham2006, Marris Reference Marris2007).

Calls to focus on ‘conservation priorities’ in the literature can broadly be divided into priorities for research (i.e., provision of information about taxa, geographical areas, threats or management responses that are currently understudied) and priorities for action (i.e., funding, locations, conservation or management of particular biodiversity components or combinations thereof). In many cases, the underlying logic is that research into these understudied components is necessary to inform conservation action. For example, Clark and May (Reference Clark and May2002) identified taxonomic biases in conservation research and argued that ‘Saving all these parts [of biodiversity] necessarily requires research on each of them’. Other reviews highlight mismatches between the availability of research on major drivers of biodiversity loss, taxonomic groups according to conservation status or threatened geographical areas (Lawler et al. Reference Lawler, Aukema, Grant, Halpern, Kareiva and Nelson2006, Di Marco et al. Reference Di Marco, Chapman, Althor, Kearney, Besancon and Butt2017, Mazor et al. Reference Mazor, Doropoulos, Schwarzmueller, Gladish, Kumaran and Merkel2018). Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Balmford and Wilcove2020) point to a scarcity of research on policy and management responses relative to the drivers of biodiversity decline.

Conservation research priorities are typically identified in the literature for the sake of other researchers (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Balmford and Wilcove2020), funders, journals (Di Marco et al. Reference Di Marco, Chapman, Althor, Kearney, Besancon and Butt2017) or conservation science as a whole (Lawler et al. Reference Lawler, Aukema, Grant, Halpern, Kareiva and Nelson2006, Godet & Devictor Reference Godet and Devictor2018). In contrast, there is often less clarity over for whom conservation action priorities are intended, other than a broad reference to policymakers, managers or non-governmental organizations (NGOs). More recently, some scientists have contested the notion that any particular taxa, location or threatening process can be considered a ‘conservation priority’, unless they are tied explicitly to an action (Game et al. Reference Game, Kareiva and Possingham2013). Some scholarship, and particularly during the growth phase of global conservation prioritization (Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Baquero, da Fonseca, Gerlach, Hoffmann and Lamoreux2006), fails to explicitly consider how a conservation priority should be actioned, such as by assuming protected areas are the primary (Margules & Pressey Reference Margules and Pressey2000) or most important conservation tool (Godet & Devictor Reference Godet and Devictor2018). As a conservation strategy, protected areas have been a prominent feature of conservation discourse since the 1960s (Mace Reference Mace2014), and they are still considered to be a ‘cornerstone’ of global conservation efforts (Gaston et al. Reference Gaston, Jackson, Cantú-Salazar and Cruz-Piñón2008, Watson et al. Reference Watson, Dudley, Segan and Hockings2014).

Shifts in the framing of conservation

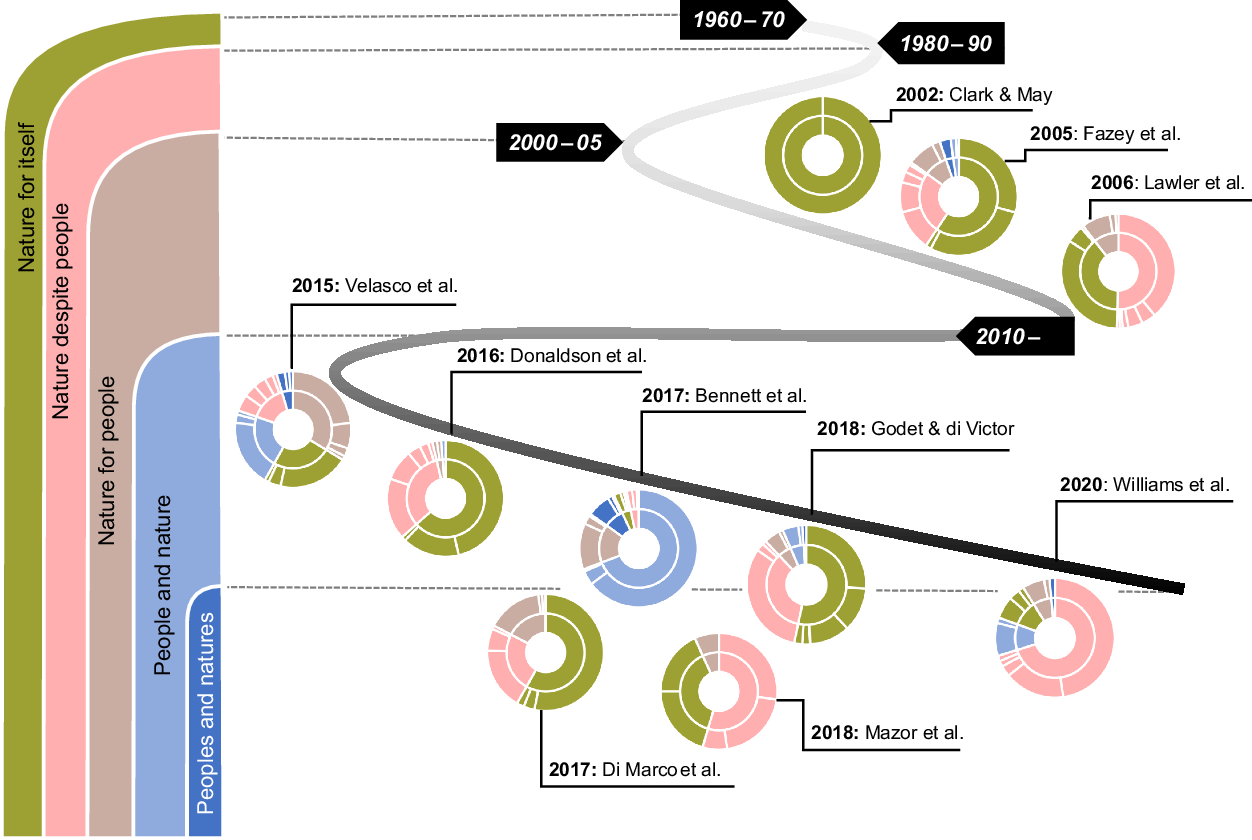

Mace (Reference Mace2014) previously documented four major shifts in the framing and goal(s) of conservation over time, from an early focus on species, habitats and protected areas in the 1960s–1970s, to the most recent emphasis on interdisciplinarity and socioecological systems. These four frames primarily relate to how the relationship between biodiversity and people is viewed – from wholly separate to intimately connected (Mace Reference Mace2014). Frames are powerful, as they provide a lens through which to define a problem, articulate goals and identify relevant actions (Pregernig Reference Pregernig2014). As described by Rein and Schön (Reference Rein and Schön1996), framing also ‘provides conceptual coherence, a direction for action, a basis for persuasion, and a framework for the collection and analysis of data – order, action, rhetoric, and analysis’. As such, the four frames documented by Mace (Reference Mace2014) are used here as a conceptual framework to examine how conservation science has been conceptualized over time (Fig. 1), using the content of existing reviews of the conservation science (Table 1) literature as a heuristic.

Fig. 1. A timeline illustrating how 10 existing reviews of the conservation science literature (Table 1) align with the key ideas and four major frames of conservation identified by Mace (Reference Mace2014). Starburst diagrams show the frequency of key terms in each review (see Supplementary Materials) according to how Mace (Reference Mace2014) categorized these terms with respect to the four frames. A fifth frame, ‘Peoples and natures’, aims to capture terms not identified by Mace (Reference Mace2014), but that correspond to more recent emergent themes within the conservation literature, such as co-production and transdisciplinarity.

Mace (Reference Mace2014) argued that shifts in the framing of conservation over time have not displaced the focus on ‘traditional’ topics, and so multiple frames exist in current conservation science and practice. This phenomenon is illustrated (Fig. 1) using a quantitative, directed content analysis of the selected review articles (Supplementary Table S1, available online) (Dixon-Woods et al. Reference Dixon-Woods, Agarwal, Jones, Young and Sutton2005, Hsieh & Shannon Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005). The progression of key ideas and underpinnings over time has not been strictly linear, since some earlier reviews considering topics related to the more recent ‘People and nature’ frame (Fazey et al. Reference Fazey, Fischer and Lindenmayer2005), while newer reviews focus primarily on topics that are more indicative of ‘Nature for itself’ and ‘Nature despite people’ (Di Marco et al. Reference Di Marco, Chapman, Althor, Kearney, Besancon and Butt2017, Godet & Devictor Reference Godet and Devictor2018).

A simple frequency analysis of key terms within these selected literature reviews risks missing crucial context (Morgan Reference Morgan1993, Vaismoradi et al. Reference Vaismoradi, Turunen and Bondas2013), and so a more detailed examination is warranted. Yet these results (Fig. 1) are corroborated by considering the scope and aims of the selected literature reviews (Table 1), which have broadened from an initial focus on taxonomic and geographical bias (Clark & May Reference Clark and May2002) towards emphasizing the need for more research on specific threatening processes (Lawler et al. Reference Lawler, Aukema, Grant, Halpern, Kareiva and Nelson2006, Di Marco et al. Reference Di Marco, Chapman, Althor, Kearney, Besancon and Butt2017) and policy and management responses (Godet & Devictor Reference Godet and Devictor2018, Williams et al. Reference Williams, Balmford and Wilcove2020). The next section describes three additional emergent themes: the dominance of research philosophies that view conservation through a primarily ecological lens; shifts and a lack of agreement over the goal(s) of conservation; and a lack of clarity over the role(s) of science in biodiversity.

Research philosophies in conservation science

It is clear when considering the selected reviews of conservation science (Fig. 1 & Table 1) that biodiversity is the primary object of study, rather than the social and policy systems with which it interacts. It should be noted that the authors of more recent reviews (Velasco et al. Reference Velasco, García-Llorente, Alonso, Dolera, Palomo, Iniesta-Arandia and Martín-López2015, Di Marco et al. Reference Di Marco, Chapman, Althor, Kearney, Besancon and Butt2017) have sought to ensure continuity and comparability of findings, and so they have maintained many of the original categories devised by early reviews (Clark & May Reference Clark and May2002, Fazey et al. Reference Fazey, Fischer and Lindenmayer2005). Bennett et al. (Reference Bennett, Roth, Klain, Chan, Christie and Clark2017) note that conservation – as a set of social phenomena, processes or human attributes – can be researched according to relevant units of analysis at multiple spatial scales (e.g., global and regional, national and subnational, to local and individual), just as biodiversity can be understood at multiple levels of organization. And yet, to date, it appears that no other existing reviews of conservation science have organized their findings according to this perspective.

Viewing conservation science primarily through an ecological lens is not unexpected given the history of the discipline (Meine et al. Reference Meine, Soule and Noss2006) and the well-documented underrepresentation of the social sciences that is still in the process of being corrected (Mascia et al. Reference Mascia, Brosius, Dobson, Forbes, Horowitz, McKean and Turner2003, Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Roth, Klain, Chan, Christie and Clark2017). A primary focus on biodiversity itself within conservation science is also not necessarily problematic, as long as there is explicit consideration of theories of change (Pilbeam Reference Pilbeam, Wyborn, Kalas and Rust2019) and likely pathways between knowledge and action (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Davila, Toomey and Wyborn2017, Toomey et al. Reference Toomey, Knight and Barlow2017). But the dominance of an ecological perspective does point to the centrality within conservation science of a particular way of thinking and knowing that is ubiquitous within the natural, physical and some social sciences, but does not necessarily align with how other conservation actors see and understand the world (Roebuck & Phifer Reference Roebuck and Phifer1999, Moon & Blackman Reference Moon and Blackman2014, Moon et al. Reference Moon, Blackman, Adams, Colvin, Davila and Evans2019, Latulippe & Klenk Reference Latulippe and Klenk2020). Far from being an esoteric, academic issue, research philosophy has a very real impact on how conservation is framed (Mace Reference Mace2014, Díaz et al. Reference Díaz, Demissew, Carabias, Joly, Lonsdale and Ash2015), the extent to which values and preferences are considered to be within the domain of science (Barry & Oelschlaeger Reference Barry and Oelschlaeger1996, Noss Reference Noss2007) and what are considered to be legitimate goal(s) of conservation science (Sandbrook Reference Sandbrook2015).

Diverse goal(s) of conservation science

The explicitly normative nature of conservation science and the presence of diverse values and ways of seeing and understanding the world (Moon & Blackman Reference Moon and Blackman2014, Green et al. Reference Green, Armstrong, Bogan, Darling, Kross and Rochman2015, Kohler et al. Reference Kohler, Holland, Kotiaho, Desrousseaux and Potts2019) mean that there is ample scope within the discipline for a wide range of goals (also referred to as aims, objectives or purpose). Sandbrook (Reference Sandbrook2015) described this vision of conservation as ‘a forest rather than a single tree – a parliament not a corporation’. But the conceptualization of diverse goals in conservation science is not universally accepted, as authors often point to how conservation biology was originally defined not by a discipline, but by its goal (Soulé Reference Soulé1985, Ehrenfeld Reference Ehrenfeld1992). As such, articles within the mainstream literature will usually refer to the seminal works of Soulé, Ehrenfeld, Noss or Wilcox to describe the goal(s) of conservation (science), but they will often make subtle yet crucial adjustments to reflect their own views and study aims (Table 1) (Doak et al. Reference Doak, Bakker, Goldstein and Hale2014, Sandbrook Reference Sandbrook2015).

For example, Lawler et al. (Reference Lawler, Aukema, Grant, Halpern, Kareiva and Nelson2006) identified research gaps according to threatened taxa and key threats, and they emphasized that ‘… understanding the primary threats to biodiversity is a central goal in conservation biology’. Fazey et al. (Reference Fazey, Fischer and Lindenmayer2005) considered the policy and management relevance of the literature they examined and described conservation biology as ‘… an applied discipline that aims to inform practitioners about how best to understand and manage species and habitats’. Di Marco et al. (Reference Di Marco, Chapman, Althor, Kearney, Besancon and Butt2017) focused on underrepresented taxa, threats and geographical locations, and they acknowledged that while conservation science has undergone shifts in its goals and approaches over time, ‘… the overall purpose of increasing our understanding of what threatens biodiversity, and what actions and policies are needed to preserve it, has remained unchanged’.

In their review of the conservation social sciences, Bennett et al. (Reference Bennett, Roth, Klain, Chan, Christie and Clark2017) explicitly acknowledged the possibility of multiple conservation (science) goals (Sandbrook Reference Sandbrook2015) by explaining that ‘Social science researchers can have a number of objectives, including to understand, describe, theorize, deconstruct, predict, imagine or plan’. They aimed to foster a better understanding of ‘the role that the social sciences can play in guiding and improving conservation’, which is ‘often misunderstood’ (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Roth, Klain, Chan, Christie and Clark2017). Yet within the literature there appears to be a lack of clarity and explicit discussion regarding the role(s) of science in conservation and the extent to which these may align with or differ from the goal(s) of science in conservation.

Clarifying the role(s) of science in meeting conservation goal(s)

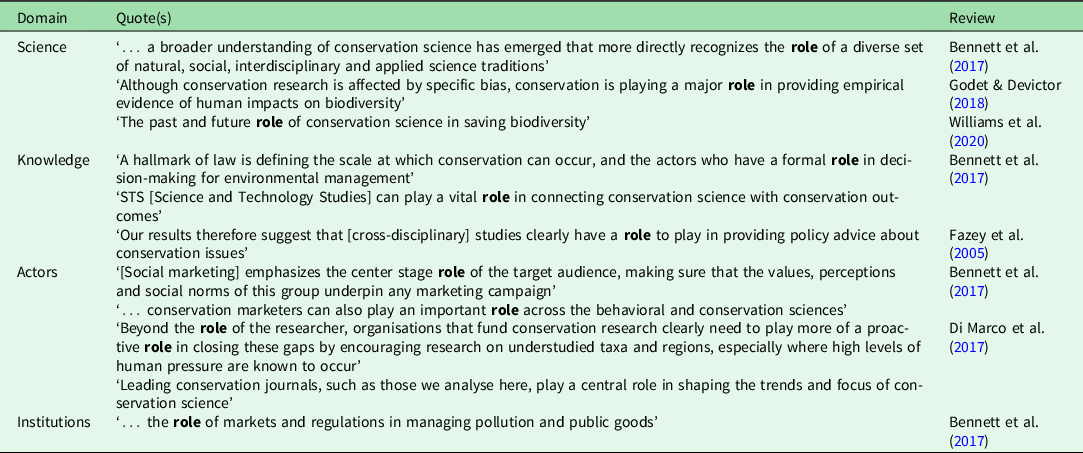

The Oxford English Dictionary defines ‘role’ as ‘the function performed by someone or something in a particular situation or process’. ‘Role’ is distinct from ‘goal’, which is ‘an aim or outcome which a person, group, or organization works towards or strives to achieve’. With the existence of multiple conservation goals, it logically follows that there may be multiple roles or ‘function(s) performed by someone or something’ for science in biodiversity conservation. None of the selected reviews (Table 1) explicitly referred to the possibility of multiple roles for science, but collectively they point to a range of roles for science (as a whole), as well as knowledges, actors and institutions (Table 2).

Table 2. Explicit references to the role(s) of science in biodiversity conservation within selected reviews (Table 1) according to a directed content analysis (see Supplementary Materials). Statements are categorized according to whether review authors broadly referred to ‘science’, or more specifically to knowledges, actors or institutions associated with science. Note that Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Balmford and Wilcove2020) explicitly referred to the role of science in the title, but not in the paper’s main text.

The role of science has certainly been discussed within the conservation literature, but this has largely occurred as part of rather dichotomous debates (Garrard et al. Reference Garrard, Fidler, Wintle, Chee and Bekessy2016) over whether scientists can legitimately engage with values (Barry & Oelschlaeger Reference Barry and Oelschlaeger1996, Noss Reference Noss2007), public policy discussions (Robertson & Hull Reference Robertson and Hull2001) or protest and civil disobedience (Castree Reference Castree2019, Gardner & Wordley Reference Gardner and Wordley2019, Hagedorn et al. Reference Hagedorn, Kalmus, Mann, Vicca, van den Berge and van Ypersele2019). There has also been considerable discussion regarding the skills that conservation scientists should develop over their careers, such as policy implementation, outreach and communications (Jacobson Reference Jacobson1990, Noss Reference Noss1997, Jacobson & McDuff Reference Jacobson and McDuff1998, Muir & Schwartz Reference Muir and Schwartz2009), which do not neatly fit within a traditional ‘knowledge provision’ role of science. But explicit analysis of the role(s) of science in society has typically been the domain for scholars of science and technology studies (Jasanoff Reference Jasanoff2004, Miller & Wyborn Reference Miller and Wyborn2018) and knowledge governance (Turnhout et al. Reference Turnhout, Stuiver, Klostermann, Harms and Leeuwis2013, van Kerkhoff & Lebel Reference van Kerkhoff and Lebel2015), and it has only entered the mainstream conservation literature in the past decade (Colloff et al. Reference Colloff, Lavorel, van Kerkhoff, Wyborn, Fazey and Gorddard2017, Evans et al. Reference Evans, Davila, Toomey and Wyborn2017).

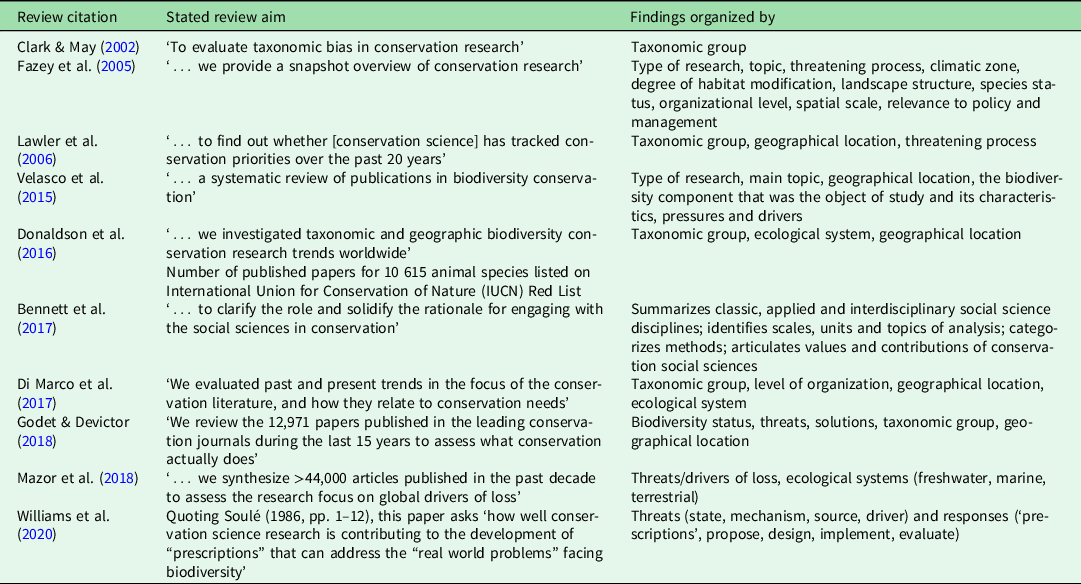

For the sake of clarity, the framework in Fig. 2 is offered to illustrate the possible role(s) of science in meeting biodiversity conservation goal(s). In a simple conceptualization of the role of science in biodiversity conservation (Fig. 2(a)), ‘science’ encompasses actors (scientists, researchers, practitioners), institutions (journals, NGOs, research organizations) and knowledge (scientific evidence), which each play a role in meeting a conservation goal. When only a single conservation goal is considered, only one or a small number of roles may be considered legitimate. Once a plurality of conservation goals are recognized (Fig. 2(b)), it becomes more apparent that there may be multiple legitimate roles and pathways for science in biodiversity conservation, depending on the values embedded within conservation goals and the actors, institutions and knowledges (including traditional, Indigenous, local) associated with different fields of research, policy and practice.

Fig. 2. A simple framework illustrating the relationship between conservation goal(s) and role(s) for science (encompassing actors, knowledges and institutions). (a) When conservation is conceptualized as having only a single goal and science is considered as monolithic, only one or a small number of roles may be considered legitimate for science. (b) With more explicit recognition of the actors, knowledges and institutions associated with diverse fields of research, policy and practice that contribute to multiple conservation goals (which may not necessarily be considered as be part of conservation science), a more nuanced conceptualization of the roles for ‘science’ in conservation is possible.

Conservation science itself has always been explicitly multidisciplinary (Meine et al. Reference Meine, Soule and Noss2006, Kareiva & Marvier Reference Kareiva and Marvier2012), but some fields (Fig. 2(b), shaded grey circles) are more dominant than others (Velasco et al. Reference Velasco, García-Llorente, Alonso, Dolera, Palomo, Iniesta-Arandia and Martín-López2015, Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Roth, Klain, Chan, Christie and Clark2017). Indeed, it is telling that Soulé (Reference Soulé1985) emphasized the ‘dependence of the biological sciences on social science disciplines’, yet social science terminology only really began to appear in reviews of the conservation science literature 30 years later (Fig. 1) (Velasco et al. Reference Velasco, García-Llorente, Alonso, Dolera, Palomo, Iniesta-Arandia and Martín-López2015, Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Roth, Klain, Chan, Christie and Clark2017). Other fields (Fig. 2(b), white circle with grey outline) may not be widely recognized as being part of conservation science itself, but nonetheless may play a role in meeting conservation goals. For example, it may be that social science and humanities disciplines are more greatly represented in conservation than existing reviews of conservation science would indicate (Fig. 1 & Table 1), simply because the selection of journals considered by previous review authors as being broadly representative of conservation science are often heavily skewed towards ecological journals (Table 3 & Supplementary Materials).

Table 3. Journals that were selected for analysis by more than one of the existing reviews of the conservation science literature (Table 1). Note that the maximum frequency is 8, as neither Donaldson et al. (Reference Donaldson, Burnett, Braun, Suski, Hinch, Cooke and Kerr2016) nor Bennett et al. (Reference Bennett, Roth, Klain, Chan, Christie and Clark2017) selected literature to review according to journal title. Further information is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Discussion

Clearly, the 10 reviews of the conservation science literature examined here are not fully representative of the discipline at large, even though most have broadly aimed to evaluate trends and biases in conservation research, policy and practice (Table 1). Analysis of the aims, findings and frames embedded in each review nevertheless provides a useful insight into how conservation science has been conceptualized by at least a portion of the community. The present review points to the dominance of a positivist research philosophy in conservation science (Roebuck & Phifer Reference Roebuck and Phifer1999, Sandbrook et al. Reference Sandbrook, Adams, Büscher and Vira2013, Moon et al. Reference Moon, Blackman, Adams, Colvin, Davila and Evans2019), as well as the existence of multiple, legitimate conservation goals (Sandbrook Reference Sandbrook2015, Sandbrook et al. Reference Sandbrook, Fisher, Holmes, Luque-Lora and Keane2019). While there is already an expansive body of work that corroborates these first two claims, this review has also highlighted a lack of clarity and explicit discussion over the role(s) of science in biodiversity conservation within the mainstream literature.

What does it mean to re-conceptualize the role(s) of science in biodiversity conservation and how could this assist in improving conservation science, policy and practice? In the first instance, deeper and more explicit recognition of the complex spaces in which science operates (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Davila, Toomey and Wyborn2017, Toomey et al. Reference Toomey, Knight and Barlow2017) could help to clarify roles and pathways for science in meeting conservation goals. The framework offered in Fig. 2 might assist conservation scientists (including those who conduct future reviews of the literature) in conceptualizing which conservation goal(s) they are envisioning as they go about their work, as well as the goal(s) of their colleagues working within and outside their own particular field of research, policy or practice. For example, considering a range of conservation goals and broadening study aims (Table 1) to encompass social, economic and policy systems in addition to biodiversity itself may assist in creating more space for contributions from diverse social science and humanities traditions (Sandbrook et al. Reference Sandbrook, Adams, Büscher and Vira2013, Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Roth, Klain, Chan, Christie and Clark2017).

Acknowledging the diversity of views within conservation science (Sandbrook et al. Reference Sandbrook, Fisher, Holmes, Luque-Lora and Keane2019) does not devalue or discredit the conservation goals articulated by Soulé (Reference Soulé1985) and other authors (Sandbrook et al. Reference Sandbrook, Adams, Büscher and Vira2013). Rather, a too-narrow focus on particular goal(s), role(s) and research philosophies may inadvertently ‘close down’ conversations that could generate novel insights for biodiversity conservation (Stirling Reference Stirling2008, Lövbrand et al. Reference Lövbrand, Beck, Chilvers, Forsyth, Hedrén and Hulme2015). It is common for scientists to adopt a particular way of thinking and knowing (Moon & Blackman Reference Moon and Blackman2014), as well as a view on the role(s) of science and scientists in society. But individual worldviews do not negate the existence of the multiple ways in which scientists can legitimately engage in society (Pielke Jr Reference Pielke2007, Turnhout et al. Reference Turnhout, Stuiver, Klostermann, Harms and Leeuwis2013). As a normative dilemma, a conclusive answer to ‘what is the role of science?’ is impossible to obtain, and so a broad range of views will continue to exist.

Discussion of the ways in which knowledge shapes action (and vice versa) has been part of scientific discourse to varying degrees over the past four decades (Funtowicz & Ravetz Reference Funtowicz and Ravetz1993, Knapp et al. Reference Knapp, Schröter, Bonn, Klotz, Seppelt and Baessler2019, Wyborn et al. Reference Wyborn, Datta, Montana, Ryan, Leith and Chaffin2019), although it has only become prominent within conservation science relatively recently (Robertson & Hull Reference Robertson and Hull2001, Tengö et al. Reference Tengö, Brondizio, Elmqvist, Malmer and Spierenburg2014, Colloff et al. Reference Colloff, Lavorel, van Kerkhoff, Wyborn, Fazey and Gorddard2017). Co-productive research processes often require significant investment by non-research stakeholders, skilful facilitation and coordination, long-term commitment and recognition that the role(s) and primacy of science itself may necessarily change (Lövbrand et al. Reference Lövbrand, Beck, Chilvers, Forsyth, Hedrén and Hulme2015, Norström et al. Reference Norström, Cvitanovic, Löf, West, Wyborn and Balvanera2020, Rose et al. Reference Rose, Evans, Jarvis, Sutherland, Brotherton, Davies, Ockendon, Pettorelli and Vickery2020).

Given the urgency, scale and resource-limited nature of the biodiversity crisis, investment in such adaptive, inclusive and often messy processes may seem infeasible (Sutherland et al. Reference Sutherland, Shackelford and Rose2017). This is not to suggest that all scientific research can – or should – be actively and deliberately co-produced (Lemos et al. Reference Lemos, Arnott, Ardoin, Baja, Bednarek and Dewulf2018, Knapp et al. Reference Knapp, Schröter, Bonn, Klotz, Seppelt and Baessler2019, Oliver et al. Reference Oliver, Kothari and Mays2019). However, it must be recognized that science is inevitably co-produced within spaces where multiple knowledges and values exist, with or without the direct involvement of scientists (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Davila, Toomey and Wyborn2017, Miller & Wyborn Reference Miller and Wyborn2018). This means that it is beneficial to – at the very least – consider exactly how science may ultimately influence conservation outcomes (Pilbeam Reference Pilbeam, Wyborn, Kalas and Rust2019), including what other actors, knowledges and institutions may play a role (Reed et al. Reference Reed, Graves, Dandy, Posthumus, Hubacek and Morris2009, Colvin et al. Reference Colvin, Witt and Lacey2016, Evans & Cvitanovic Reference Evans and Cvitanovic2018).

Effective co-production explicitly acknowledges the role of power and its effects on engagement processes and outcomes and seeks a more equitable role for science and scientists alongside other actors and knowledge systems (Benham & Daniell Reference Benham and Daniell2016, Norström et al. Reference Norström, Cvitanovic, Löf, West, Wyborn and Balvanera2020, Rose et al. Reference Rose, Evans, Jarvis, Sutherland, Brotherton, Davies, Ockendon, Pettorelli and Vickery2020). Conservation science has been complicit in historical and ongoing discrimination against marginalized peoples, and calls for recognition and correction of inequities and injustice are growing in prominence (Mammides et al. Reference Mammides, Goodale, Corlett, Chen, Bawa and Hariya2016, Salomon et al. Reference Salomon, Lertzman, Brown, Wilson, Secord and McKechnie2018, Chaudhury & Colla Reference Chaudhury and Colla2020). Actively creating space for the consideration of diverse voices, values and approaches, even when critical or in conflict, can only serve to strengthen conservation (Green et al. Reference Green, Armstrong, Bogan, Darling, Kross and Rochman2015, Gould et al. Reference Gould, Phukan, Mendoza, Ardoin and Panikkar2018, Latulippe & Klenk Reference Latulippe and Klenk2020). Crucially, conflicting views must be made explicit and openly deliberated (Sandbrook et al. Reference Sandbrook, Fisher, Holmes, Luque-Lora and Keane2019), since even good-willed attempts to focus only on the common ground amongst diverse voices may suppress innovation and serve to further entrench dominant views ‘by denying the very existence of margins’ (Matulis & Moyer Reference Matulis and Moyer2017).

Finally, conservation science can provide crucial insights into how and why social changes occur (Isgren et al. Reference Isgren, Boda, Harnesk and O’Byrne2019) and where leverage points may exist to facilitate transformations to sustainability (Díaz et al. Reference Díaz, Settele, Brondízio, Ngo, Agard and Arneth2019, Fischer & Riechers Reference Fischer and Riechers2019, Chan et al. Reference Chan, Boyd, Gould, Jetzkowitz, Liu and Muraca2020). Numerous opportunities exist for conservation scientists to engage in transformational change (Pereira et al. Reference Pereira, Frantzeskaki, Hebinck, Charli-Joseph, Drimie and Dyer2020, Scoones et al. Reference Scoones, Stirling, Abrol, Atela, Charli-Joseph and Eakin2020, Wyborn et al. Reference Wyborn, Davila, Pereira, Lim, Alvarez and Henderson2020a), including with narratives (Louder & Wyborn Reference Louder and Wyborn2020), systems (Davila et al. Reference Davila, Plant and Jacobs2021) and futures thinking (Wyborn et al. Reference Wyborn, Louder, Harfoot and Hill2021a). This necessarily requires scientists and science as a whole to ‘… become more reflective about [their] own assumptions and paradigms, including those relating to how change comes about’ (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2012). It is therefore crucial that conservation scientists continually reflect on how their own values and ethics shape their science, have an appreciation of and respect for other ways of thinking and knowing and understand that there are multiple, legitimate pathways to achieving conservation goals.

Conclusions

Conservation science emerged due to the need for a ‘more comprehensive, better-integrated response’ (Meine Reference Meine2004, p. 75, Meine et al. Reference Meine, Soule and Noss2006) to understanding and solving complex conservation problems that traditional scientific disciplines had ‘failed’ to adequately address (Noss Reference Noss1999). This review has shown that although conservation science has clearly diversified in its ideas, frames, philosophies and goals over the past four decades (Mace Reference Mace2014), this diversity is not often represented within existing reviews of the literature. An overwhelming focus on biodiversity as the primary object of study (Table 1) and the identification of primarily ecological journals by review authors (Table 3) are indicative of the historical and contemporary biases that still occur within conservation science as a discipline.

In future, broader and deeper recognition that conservation science can accommodate a diversity of goal(s), values and ways of knowing could assist in ‘opening up’ novel insights and pathways. Within these complex spaces are opportunities to co-produce solutions that are appropriate to specific contexts, as well as ample scope to study whether and how change occurred, to learn and to adapt. In the face of multiple urgent global crises, it may seem indulgent to critically reflect on what logics and assumptions have been embedded within mainstream conservation science to date. But just as conservation occurs within highly contested and complex socio-political environments, so too does conservation science. What better way to learn how science can better facilitate transformational change than to turn the lens onto ourselves?

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892921000114

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the Country in which this work was completed, including the Turrbal and Jagera peoples of Meanjin (Brisbane) and the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples of Canberra. I honour their Elders past and present and acknowledge that sovereignty was never ceded. I thank the Biodiversity Revisited Symposium participants for challenging and shaping my thinking, and especially Carina Wyborn and Federico Davila for their crucial feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript. I also thank two reviewers who provided comments that assisted in greatly improving this manuscript.

Financial support

This work was financially supported by the Luc Hoffmann Institute and an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Award (DE200100190). The Biodiversity Revisited Symposium was supported by generous funding from the MAVA Foundation, the NOMIS Foundation and WWF.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

None.