INTRODUCTION

Across the globe biodiversity is declining and the ‘2010 target’ of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) has not been met (CBD 2010). The destruction and fragmentation of habitat along with overexploitation are the main causes of the global biodiversity crisis (MA [Millennium Assessment] 2005; Brook et al. Reference Brook, Sodhi and Bradshaw2008; Ehrlich & Pringle Reference Ehrlich and Pringle2008). Old-growth forests play a key role in maintaining biodiversity and are irreplaceable for sustaining biodiversity (Gibson et al. Reference Gibson, Lee, Koh, Brook, Gardner, Barlow, Peres, Bradshaw, Laurance, Lovejoy and Sodhi2011). Moreover, old-growth forests play an important part in the response to climate change. Contrary to the long standing view that they are carbon neutral, they continue to sequester carbon for long time periods, but also store more carbon per unit area than any other ecosystem or forest successional stage (Luyssaert et al. Reference Luyssaert, Schulze, Borner, Knohl, Hessenmoller, Law, Ciais and Grace2008; Knohl et al. Reference Knohl, Schulze, Wirth, Wirth, Gleixner and Heimann2009; Wirth Reference Wirth, Wirth, Gleixner and Heimann2009; Keeton et al. Reference Keeton, Whitman, McGee and Goodale2011), though future sequestration dynamics under altered climate remain uncertain. Old-growth forests in the Carpathian Mountain region of Europe, in particular, store very high levels of carbon in comparison to younger and managed forests (Holeksa et al. Reference Holeksa, Saniga, Szwagrzyk, Czerniak, Staszynska and Kapusta2009; Keeton et al. Reference Keeton, Chernyavskyy, Gratzer, Main-Knorn, Shpylchak and Bihun2010).

Despite their ecological importance, old-growth forests around the globe are vanishing at an alarming rate mainly due to deforestation, unsustainable logging practices, and increases in fire frequency (Achard et al. Reference Achard, Eva, Mollicone, Popatov, Stibig, Turubanova, Yaroshenko, Wirth, Gleixner and Heimann2009). Ecosystem services they provide (such as genetic resources, protection from natural hazards and riparian functionality) are thereby diminished (Keeton et al. Reference Keeton, Kraft and Warren2007; Wirth et al. Reference Wirth, Gleixner, Heimann, Wirth, Gleixner and Heimann2009a) and biodiversity they harbour is threatened. In the industrialized countries of northern Europe especially, land-use changes and conversion of primary forests to managed plantations have almost completely eradicated old-growth forests (Wirth et al. Reference Wirth, Messier, Bergeron, Frank, Fankhänel, Wirth, Gleixner and Heimann2009b). Of the total forest area in central Europe, only 0.2% of old-growth forests have survived, mainly in remote, mountainous areas or within nature reserves (Frank et al. Reference Frank, Finckh, Wirth, Wirth, Gleixner and Heimann2009; Schulze et al. Reference Schulze, Hessenmoeller, Knohl, Luyssaert, Boerner, Grace, Wirth, Gleixner and Heimann2009).

Goods and services from European temperate forests, such as clean water, wood products and recreation opportunities in relation to the large number of people living in close proximity, make these forests socioeconomically important (Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Mackey, McNulty and Mosseler2009). One area where forests are particularly valuable in this respect is the Romanian Carpathians, comprising the eastern and southern extension of the mountain range. Here, vast forests including large tracts of old-growth forests, provide important habitat for the largest European populations of brown bear (Ursus arctos), gray wolf (Canis lupus), and lynx (Lynx lynx). Moreover, these old-growth forests have been recognized for their exceptional biodiversity harbouring many endemic, rare and threatened species (Biriş & Veen Reference Biriş and Veen2005; Ioras & Abrudan Reference Ioras and Abrudan2006; Biriş et al. Reference Biriş, Doniţă and Teodosiu2010).

While using the term ‘old-growth forests’, we follow Wirth et al. (Reference Wirth, Messier, Bergeron, Frank, Fankhänel, Wirth, Gleixner and Heimann2009b) and Burrascano (Reference Burrascano2010) in including widely accepted criteria for moist temperate old-growth forests: relatively old stand age, abundance of large old tree species, deadwood components (both standing and downed), dominance by late-successional tree species, vertically complex canopies and horizontal structural heterogeneity (namely gap mosaics). These elements of stand structural complexity correlate with a variety of habitat functions for late-successional forests; these are frequently missing or under-represented in younger or managed forests (Keeton Reference Keeton2006; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Keeton, Twery and Tobi2008).

Assessing the status of old-growth forests in the Carpathians is difficult due to often outdated, incomplete and fragmented forest resource information. The last official national forest inventory for Romania was carried out in 1984 (Brandlmaier & Hirschberger Reference Brandlmaier and Hirschberger2005; Marin et al. Reference Marin, Bouriaud, Marius, Nitu, Tomppo, Gschwanter, Lawrence and McRoberts2010). Nevertheless, a comprehensive scientific assessment of the status of old-growth forests was performed in Romania between 2001 and 2004 (Veen et al. Reference Veen, Fanta, Raev, Biriş, de Smidt and Maes2010), identifying approximately 210 000 ha of old-growth forest, comprising 3.5% of total Romanian forest cover. This is more than in any other Central European country. However, the extent of Romania's old-growth forest has decreased substantially from approximately 2 million ha at the end of the 19th century to 700 000 ha in 1945 and 400 000 ha in 1984 (Veen et al. Reference Veen, Fanta, Raev, Biriş, de Smidt and Maes2010). Severe threats for these forests include illegal logging, invasive species and climate change (Biriş & Veen Reference Biriş and Veen2005; Price et al. Reference Price, Gratzer, Duguma, Kohler, Maselli and Romeo2011).

Following the collapse of communism in 1989, the next two decades in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) were characterized by a weakening of civil societies and a decline in political participation (Howard Reference Howard2003). Especially in Romania, biodiversity governance remained challenging due to weak collaboration between the environmental sector and state administration (Börzel & Buzogány Reference Börzel and Buzogány2010). Protecting biodiversity often competes with forestry, constrains other land uses, and may foster conflicts with livelihoods (Niedziałkowski et al. Reference Niedziałkowski, Paavola and Jędrzejewska2012). Thus, a key challenge for CEE countries remains the goal of increasing public involvement in biodiversity governance (Niedziałkowski et al. Reference Niedziałkowski, Paavola and Jędrzejewska2012).

In this context, one of the most pressing recent threats in Romania relates to the changes in forest ownership pattern (Nijnik et al. Reference Nijnik, Nijnik and Bizikova2009; Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Kuemmerle, Kennedy, Abrudan, Knorn and Hostert2012; Knorn et al. Reference Knorn, Kuemmerle, Radeloff, Szabo, Mindrescu, Keeton, Abrudan, Griffiths, Gancz and Hostert2012). Large areas of state forest have been restituted to prior owners, and often this has resulted in forest management changes (MCPFE [Ministerial Conference on the Protection of Forests in Europe] 2007; Barbier et al. Reference Barbier, Burgess and Grainger2010; Lambin & Meyfroidt Reference Lambin and Meyfroidt2010). Economic hardship accompanied by weak political institutions encouraged land owners receiving restituted forests to liquidate their timber assets through harvesting (Turnock Reference Turnock2002; Nichiforel & Schanz Reference Nichiforel and Schanz2011). The combination of an uncertain institutional environment (Lambin et al. Reference Lambin, Turner, Geist, Agbola, Angelsen, Bruce, Coomes, Dirzo, Fischer, Folke, George, Homewood, Imbernon, Leemans, Li, Moran, Mortimore, Ramakrishnan, Richards, Skanes, Steffen, Stone, Svedin, Veldkamp, Vogel and Xu2001), poverty and the high timber value of old-growth forests additionally increased exploitation beyond sustainable levels (Anfodillo et al. Reference Anfodillo, Carrer, Valle, Giacoma, Lamedica and Pettenella2008). Moreover, the fast growing number of small-scale forest holdings (approximately 800 000 by the end of the restitution process) (Ioras & Abrudan Reference Ioras and Abrudan2006) has hampered the establishment of sustainable forest management practices and hindered biodiversity governance (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Wear and Flamm1996; Nijnik et al. Reference Nijnik, Nijnik and Bizikova2009; Żmihorski et al. Reference Żmihorski, Chylarecki, Rejt and Mazgajski2010). Lastly, weak law enforcement fosters logging practices and magnitudes outside legal norms (Brandlmaier & Hirschberger Reference Brandlmaier and Hirschberger2005; Knorn et al. Reference Knorn, Kuemmerle, Radeloff, Szabo, Mindrescu, Keeton, Abrudan, Griffiths, Gancz and Hostert2012). These continuing threats and losses reinforce the need for an up-to-date estimate of old-growth forest disturbances in Romania and further analysis of protected area governance aimed at safeguarding these forests.

Satellite image interpretation is the most accurate and comprehensive approach for assessing forest cover changes across large areas (Achard et al. Reference Achard, Eva, Mollicone, Popatov, Stibig, Turubanova, Yaroshenko, Wirth, Gleixner and Heimann2009; FAO [Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations] 2011). Images from the Landsat Thematic Mapper (TM) and Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) sensors are able to capture canopy removal reliably across large regions (Young et al. Reference Young, Sanchez-Azofeifa, Hannon and Chapman2006; Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Olthof and Pouliot2009; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Goward, Schleeweis, Thomas, Masek and Zhu2009), including for parts of the Carpathians (Mihai et al. Reference Mihai, Savulescu and Sandric2007; Kozak et al. Reference Kozak, Estreguil and Ostapowicz2008; Kuemmerle et al. Reference Kuemmerle, Chaskovskyy, Knorn, Radeloff, Kruhlov, Keeton and Hostert2009; Main-Knorn et al. Reference Main-Knorn, Hostert, Kozak and Kuemmerle2009). Satellite analyses are particularly well suited to map forest disturbances because the reflectance of a given pixel apparently changes when the structure of a forest canopy is significantly impacted, either due to harvesting or due to natural disturbance (Coppin et al. Reference Coppin, Jonckheere, Nackaerts, Muys and Lambin2004). In contrast, it is much harder to distinguish old-growth forests from other forests, because the spectral difference between the two is subtle (Wulder Reference Wulder1998). Consequently, mapping old-growth disturbances based on satellite imagery is feasible only in areas where an accurate map of old-growth forest distribution already exists.

Our goal here was to quantify disturbance (defined in our case as full canopy removal due to either natural disturbances, such as wind or insects, or anthropogenic disturbances, such as logging) in Romanian old-growth forests, based on the delineations from the last assessment in 2004. We recognize that low to moderate intensity wind disturbances and other natural mortality events result only in partial canopy disturbance, with abundant residual live and dead trees (Splechtna et al. Reference Splechtna, Gratzer, Black and Franklin2005; Nagel et al. Reference Nagel, Svoboda and Diaci2006). In primary systems, and where salvage logging does not occur, these biological legacies are incorporated into recovering forests, often producing multi-aged stands containing remnant old-growth elements (Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Lindenmayer, MacMahon, McKee, Magnuson, Perry, Waide and Foster2000; Keeton et al. Reference Keeton, Chernyavskyy, Gratzer, Main-Knorn, Shpylchak and Bihun2010). However, for the purpose of our study, we were most concerned with the combined effects of deliberate forest clearing by people and high-intensity (sometimes termed ‘catastrophic’) natural disturbances. Specifically, we asked the following research questions: (1) To what extent did disturbances occur in Romanian old-growth forests between 2000 and 2010? (2) How were disturbances distributed among vegetation zones, and along gradients in elevation and slope? (3) How effective have protected areas been in safeguarding old-growth forests in Romania?

METHODS

Study area

The Carpathians are Europe's largest mountain range, encompassing the continent's largest continuous temperate forest ecosystem (UNEP [United Nations Environment Programme] 2007). Approximately half of the Carpathian forests are located in Romania. Our study area comprised all of the Romanian Carpathian forests (Fig. 1). In the study region, elevation (height above sea level) ranges from 0 m to >2500 m and the climate is transitional temperate-continental. The natural vegetation of the Carpathian chain generally occurs within altitudinal layers (Donita et al. Reference Donita, Ivan, Coldea, Sanda, Popescu, Chifu, Paucă-Comănescu, Mititelu and Boşcaiu1993, Reference Donita, Popescu, Paucă-Comănescu, Mihăilescu and Biriş2005) (Table 1).

Table 1 Potential natural vegetation of the Carpathian chain based on data from Donita et al. (Reference Donita, Ivan, Coldea, Sanda, Popescu, Chifu, Paucă-Comănescu, Mititelu and Boşcaiu1993, Reference Donita, Popescu, Paucă-Comănescu, Mihăilescu and Biriş2005), Cristea (Reference Cristea1993), Muica and Popova-Cucu (Reference Muica and Popova-Cucu1993) and Feurdean et al. (Reference Feurdean, Wohlfarth, Björkman, Tantau, Bennike, Willis, Farcas and Robertson2007). Numbers in squared brackets refer to the Southern Carpathians, otherwise to the Northern Carpathians.

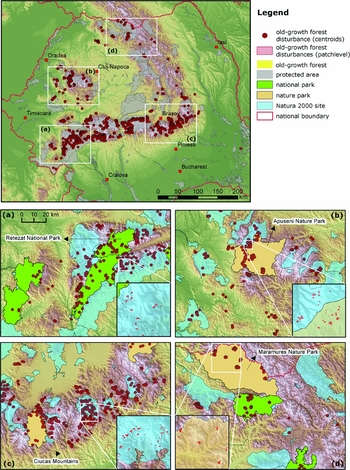

Figure 1 Study area in the Carpathian Mountains in Romania including the distribution of old-growth forest patches (Source: SRTM digital elevation model, see URL http://srtm.csi.cgiar.org; ESRI Data and Maps Kit, see URL http://www.esri.com/data/data-maps).

The 2001–2004 old-growth forest assessment (Veen et al. Reference Veen, Fanta, Raev, Biriş, de Smidt and Maes2010) identified 3402 sites of old-growth forest larger than 50 ha. These old-growth forests were located mainly in montane areas (92% above 600 m) and predominately within the Carpathian Ecoregion (Fig. 1) (Anfodillo et al. Reference Anfodillo, Carrer, Valle, Giacoma, Lamedica and Pettenella2008; Veen et al. Reference Veen, Fanta, Raev, Biriş, de Smidt and Maes2010). European beech as the dominant old-growth forest type (58%), followed by coniferous forests, including Norway spruce, silver fir, Swiss stone pine (Pinus cembra) European larch (Larix decidua) and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) (dwarf pine habitats were not included in the assessment) (Biriş & Veen Reference Biriş and Veen2005; Veen et al. Reference Veen, Fanta, Raev, Biriş, de Smidt and Maes2010).

Datasets used

We used digital maps of areas of old-growth forests (polygon layer) in Romania recorded between 2001 and 2004 (Biriş & Veen Reference Biriş and Veen2005) as our baseline, provided by the Romanian Forest Research and Management Institute (ICAS).

Forest cover changes from 2000 to 2010 were mapped across Romania using Landsat TM/ETM+ images including SLC-off imagery (thermal bands were not incorporated) for 16 footprints with a spatial resolution of either 28.5 or 30 m. Whereas most of the images had already been orthorectified by the United States Geological Survey (Level 1T), several uncorrected images (Level 1G) needed to be co-registered to the others. To do so, 1500 tie points were located using an automated point matching tool (Leica Geosystems 2006) considering both the acquisition geometry and relief (Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Kuemmerle, Kennedy, Abrudan, Knorn and Hostert2012). Results showed an overall positional error below 0.5 pixels.

Additional spatial data included administrative boundaries (ESRI Data and Maps Kit 2008, see URL http://www.esri.com/data/data-maps), protected area boundaries including Natura 2000 sites (digital datat supplied by ICAS), forest ecozones (digital data supplied by ICAS) (Fig. 2) and an enhanced digital elevation model (DEM) based on the Shuttle Topography Mission (SRTM, see URL http://srtm.csi.cgiar.org) resampled from 90 to 30 m. Forest-ecozones delineate Romania's major forest ecosystem regions (Fig. 2), and these were assessed from existing maps and ancillary data provided by ICAS, derived using guidelines provided by the Joint Research Center (JRC) (Gancz & Pătrăşcoiu Reference Gancz and Pătrăşcoiu2000).

Figure 2 Map of Romania's forest-ecozones. 1A = beech and sessile oak mixed forests, Hungarian oak (Quercus frainetto) and mixtures, on high and medium hills; 1B = forests with pedunculate oak (Quercus robur), Turkey oak (Quercus cerris), Hungarian oak and other species, on low hills and plains; 2A = spruce forests; 2B = coniferous and beech mixed forests; 2C = beech mountainous forests; 2O = alpine grasslands and/or bare rocks; 3A = xerophyte oak forests in silvosteppe; 3B = steppe (no natural forest vegetation); 4A = floodplain forests with poplar (populus), willow (Salix), alder (Alnus) and some pedunculate oak; and 4B = high floodplain forests with pedunculate oak and ash (Fraxinus excelsior).

We conducted extensive field visits in northern, central-eastern and south-western Romania, and interviews with park administrations, stakeholders, non-governmental organizations, and several scientists and other partners during 2008, 2009 and 2010.

Forest disturbance mapping

Forest disturbance maps were obtained from three previous studies with foci on different regions in Romania. The first study (Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Kuemmerle, Kennedy, Abrudan, Knorn and Hostert2012) focused on central-eastern Romania (Landsat footprint path/row 183/028) and assessed forest disturbances on an annual basis between 1984 and 2010. The second study (Knorn et al. Reference Knorn, Kuemmerle, Radeloff, Szabo, Mindrescu, Keeton, Abrudan, Griffiths, Gancz and Hostert2012) analysed forest disturbances in northern Romania (path/row 185/27) between 1987 and 2010. The third study (Olofsson et al. Reference Olofsson, Kuemmerle, Griffiths, Knorn, Baccini, Gancz, Blujdea, Houghton, Abrudan and Woodcock2011) assessed forest disturbances between 1990 and 2010 for all of Romania. Based on those maps, we assembled a single map representing forest disturbances from 2000–2010 for all of Romania. Incorporating each of the studies was necessary since the map by Olofsson et al. (Reference Olofsson, Kuemmerle, Griffiths, Knorn, Baccini, Gancz, Blujdea, Houghton, Abrudan and Woodcock2011) partly missed data due to cloud coverage. All three maps were generated using either Support Vector Machines (Pal & Mather Reference Pal and Mather2005), the Disturbance Index (Healey et al. Reference Healey, Cohen, Yang and Krankina2005), the LandTrendr (Landsat-based detection of trends in disturbance and recovery) set of change detection algorithms (Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Yang and Cohen2010) and/or Chain Classification (Knorn et al. Reference Knorn, Rabe, Radeloff, Kuemmerle, Kozak and Hostert2009). Detailed descriptions of the specific approaches are found in the original studies of Griffiths et al. (Reference Griffiths, Kuemmerle, Kennedy, Abrudan, Knorn and Hostert2012), Olofsson et al. (Reference Olofsson, Kuemmerle, Griffiths, Knorn, Baccini, Gancz, Blujdea, Houghton, Abrudan and Woodcock2011) and Knorn et al. (Reference Knorn, Kuemmerle, Radeloff, Szabo, Mindrescu, Keeton, Abrudan, Griffiths, Gancz and Hostert2012). The original forest disturbance maps were subject to individual rigorous accuracy assessments, based on independent ground reference points. Reported overall accuracies of 86.5% (Olofsson et al. Reference Olofsson, Kuemmerle, Griffiths, Knorn, Baccini, Gancz, Blujdea, Houghton, Abrudan and Woodcock2011), 94.9% (Knorn et al. Reference Knorn, Kuemmerle, Radeloff, Szabo, Mindrescu, Keeton, Abrudan, Griffiths, Gancz and Hostert2012) and 95.7% (Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Kuemmerle, Kennedy, Abrudan, Knorn and Hostert2012) provided proof of the reliability of each map. To build a single area-wide forest disturbance map covering all of Romania's old-growth forests, maps from the three original studies were aggregated and the original classes merged to ‘permanent forest’, ‘permanent non-forest’ and ‘forest disturbance’ from 2000 to 2010. While assembling, the maps from Knorn et al. (Reference Knorn, Kuemmerle, Radeloff, Szabo, Mindrescu, Keeton, Abrudan, Griffiths, Gancz and Hostert2012) and Griffiths et al. (Reference Griffiths, Kuemmerle, Kennedy, Abrudan, Knorn and Hostert2012) were prioritized due to higher accuracies and temporal resolution. Finally, a minimum mapping unit of c. 0.4 ha (4 pixels) was applied on the compiled map (Knorn et al. Reference Knorn, Kuemmerle, Radeloff, Szabo, Mindrescu, Keeton, Abrudan, Griffiths, Gancz and Hostert2012).

Comparison of old-growth forest disturbances

Using the area-wide forest disturbance map, we summarized old-growth forest disturbances based on the polygons from the digital baseline map. We derived proportions of old-growth forest disturbances in relation to both forest ecozones and protected areas. For the protected area comparison, we first assessed the total amount of old-growth forest area and old-growth forest disturbances within protected areas independent of the protection status. Second, we differentiated disturbance rates by protected area type (whether Natura 2000, National Park or Nature Park). In Romania, National Parks are in IUCN category II whereas Nature Parks are in IUCN category V. However, there is a significant overlap between Natura 2000 sites and other protected areas (Fig. 3) (Ioja et al. Reference Ioja, Patroescu, Rozylowicz, Popescu, Verghelet, Zotta and Felciuc2010). In the study area, c. 85% of National/Nature Park areas were also Natura 2000 sites, making the protection status of Natura 2000 sites variable. Natura 2000 sites (terrestrial area) covered 42 650 km2 (17.89% of Romania) and National/Nature Parks covered 10 800 km2 (4.5%). We also assessed the distribution of old-growth forest disturbances with respect to altitude and slope by categorizing the DEM into 100-m wide elevation classes and eight slope classes each 5° wide.

Figure 3 Distribution of old-growth forest disturbance patches in Romania. White squares highlight specific areas: (a) the South-Western Carpathians, (b) the Apunseni Mountains, (c) the Curvature Carpathians, and (d) the Maramures and Rodna Mountains.

In addition to the situation inside old-growth forest patches, the degree of fragmentation of the surrounding forest matrix is also important. Discontinuities and contrast in patch edges enhance the vulnerability of tall old forests to natural disturbances, alter propagule dispersal, and facilitate movement of invasive species and domesticated fauna (Foster et al. Reference Foster, Orwlg and McLachlan1996). To determine the intactness of the surrounding landscape, we summarized the area of forest disturbances within 250 m of each old-growth forest patch. The total area of these buffer zones was equal to the total area of the old-growth forest in the baseline map (c. 210 000 ha).

RESULTS

In total, 1.3% (2720 ha) of old-growth forest was disturbed during the last decade, taking into account that 7238 ha (c. 3.4%) of the inventoried 210 882 ha old-growth forest stratum could not be classified owing to clouds or cloud shadows in the satellite imagery. Old-growth forest disturbances were mainly concentrated along the interior mountain complexes of the Carpathian Ecoregion (Fig. 3). Clusters of disturbance occurred in the Maramures Mountains in the north, the Apuseni Mountains in the west and the south/south-western rim of the Carpathian mountain chain (Fig. 3).

The old-growth forest disturbance map revealed considerable differences in the distribution of disturbance among forest ecozones (Fig. 4a). Disturbances were most prevalent in the forest ecozone ‘beech mountainous forests’ (850.2 ha), followed by ‘coniferous and beech mixed forests’ (726.2 ha) and ‘spruce forests’ (457.7 ha). Fractions of disturbances among forest ecozones were similar to the respective fractions of the original old-growth forest area. However, coniferous forests generally exhibited higher disturbance rates and deciduous forests lower disturbance rates than the respective distribution of old-growth forests would have let expect (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4 Fractions of old-growth forest disturbances and original old-growth forest area in relation to: (a) forest ecozones (abbreviations for forest-ecozone types are described in Fig. 2), (b) altitude, (c) slope, and (d) protected area type (N2000 = Natura 2000 site).

The highest amount of old-growth forest disturbances was found at altitudes between 1200 and 1600 m, whereas their occurrence sharply decreased above 1600 m and gently towards hilly and plain areas below 800 m (Fig. 4b). Fractions of disturbances among altitude were broadly similar to the respective fractions of the original old-growth forest area (Fig. 4b). Old-growth forest disturbances occurred most frequently at slope gradients of between 15 and 25°, whereas just over 6% of all disturbances were found at slopes steeper than 35° (Fig. 4c).

Approximately 77% of the old-growth forest area was embedded within the Romanian protected area network. This included National Parks (23%; 37 917 ha old-growth forests), Nature Parks (14%; 22 435 ha old-growth forests), and Natura 2000 sites (63%; 161 565 ha old-growth forests, exclusive National/Nature parks) (Fig. 4d). In total, 72% of all disturbances in old-growth forests were found within a protected area. Of these, 8.5% (167 ha) were in National Parks, 22.1% (432 ha) in Nature Parks and 69.4% (1359 ha) in Natura 2000 sites (exclusive National/Nature parks) (Fig. 4d). Therefore, National Parks effectively prevent logging within old-growth forests.

Disturbances which occurred within a 250-m buffer from the old-growth forest patches sum up to 3290 ha. This corresponded to c. 1.6% of the entire area within 250 m and is thus 0.3% higher than the respective disturbed area within the original old-growth forests area.

DISCUSSION

Our remote sensing survey of old-growth forest stands in Romania revealed that disturbances in these stands occurred across the country, but were especially clustered in some areas, for example, in the Apuseni Mountains, the Maramures Mountains, the Curvature Carpathians and the South-Western Carpathians (Fig. 3). Disturbances seem triggered by high-value timber in old-growth stands, institutional changes in the Romanian forest sector and new ownership structures. Moreover, as cuttings in old-growth forests are predominantly in accordance with forest management plans, legal harvesting activities are obviously responsible for their diminishment. Protected areas, including recent expansions under the Natura 2000 framework, do not safeguard these forests as originally envisioned. Finally, disturbances in the matrix of forest communities surrounding old-growth forest patches additionally affect these old-growth forests negatively (Foster et al. Reference Foster, Orwlg and McLachlan1996). Biodiversity and specifically protected area governance continue to face serious challenges with respect to their ability to safeguard old-growth forests.

Distribution of old-growth forest disturbances

Most old-growth forest stands and related disturbances were found in mountainous regions dominated by beech forests (Fig. 2 and 3, zones 1A, 2B and 2C), followed by spruce forests (zone 2A). Only very small fractions (0.92%) of disturbances occurred in the foothills or plains (zone 1B), including the Danube flood plain (Fig. 2 and 3, zone 4A), partly because these are areas where few old-growth forests remain. Approximately 50% of all disturbances occurred at altitudes between 1100 and 1500 m (Fig. 4b). Nevertheless, as disturbance fractions correspond to the distribution of the remaining old-growth forest portions, there were only minor deviations in the distribution of disturbances among forest ecozones (slightly more in the coniferous ecozones), altitude (slightly more between 1200 and 1600 m), or slope (slightly more on slopes with less than 25°). It is conspicuous though that more than 6% of all old-growth forests disturbances were found on slopes >35°. These forests are protected by law for flood and soil protection (Veen et al. Reference Veen, Fanta, Raev, Biriş, de Smidt and Maes2010).

Natural versus anthropogenic disturbances

Natural stand-replacing forest disturbances, including insect infestation, windthrow, avalanches and sporadic fires, do occur in the Romanian Carpathians (Schelhaas et al. Reference Schelhaas, Nabuurs and Schuck2003; Toader & Dumitru Reference Toader and Dumitru2005). However, most of these disturbance types are either rare or only affect very small areas (i.e. smaller than our minimum mapping unit). Forest fires, for example, are not widespread in the Romanian Carpathians and are a negligible cause of disturbances (Anfodillo et al. Reference Anfodillo, Carrer, Valle, Giacoma, Lamedica and Pettenella2008; Rozylowicz et al. Reference Rozylowicz, Popescu, Pătroescu and Chişamera2011). Windthrow events are both relatively frequent and can cause severe disturbances. Nevertheless, Savulescu and Mihai (Reference Savulescu and Mihai2011) suggested that wind disturbances in Romania mainly affected forests with features different from their natural or primary structure. Thus, old-growth forests are more resistant to larger wind impacts. Moreover, climate data suggest that windthrow events in general have a declining frequency for Romania since 1975 (Popa Reference Popa, Anfodillo, Dalla Valle and Valese2008). In other words, large-scale natural disturbances are often related to forest management or the legacies from past management (Schelhaas et al. Reference Schelhaas, Nabuurs and Schuck2003; Mollicone et al. Reference Mollicone, Eva and Achard2006; Schulze et al. Reference Schulze, Hessenmoeller, Knohl, Luyssaert, Boerner, Grace, Wirth, Gleixner and Heimann2009). In the Carpathians, for example, spruce plantations often consist of genetically non-native spruce variants (Keeton & Crow Reference Keeton, Crow, Soloviy and Keeton2009; Kuemmerle et al. Reference Kuemmerle, Chaskovskyy, Knorn, Radeloff, Kruhlov, Keeton and Hostert2009; Macovei Reference Macovei2009) that are more susceptible to disease and pests. Although impacts of windstorms on old-growth Norway spruce in the region have also been documented (Panayotov et al. Reference Panayotov, Kulakowski, Laranjeiro Dos Santos and Bebi2011; Svoboda et al. Reference Svoboda, Janda, Nagel, Fraver, Rejzek and Bače2012), the area affected remained relatively small. Old-growth spruce forests account only for 15% of our total old-growth forest area. Taken together, natural disturbances are therefore unlikely to explain the majority of forest cover changes in the old-growth stands that we observed.

Underlying causes of anthropogenic disturbances

We suggest that major socioeconomic transformations resulted in considerable economic hardship that, combined with the restitution process and insufficient protected area enforcement, may have resulted in logging of old-growth stands. Moreover, most logging activities are in accordance with forest management plans. Although we caution that a causal connection cannot be established based on our analyses alone, our results, expert interviews, our own previous studies (Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Kuemmerle, Kennedy, Abrudan, Knorn and Hostert2012; Knorn et al. Reference Knorn, Kuemmerle, Radeloff, Szabo, Mindrescu, Keeton, Abrudan, Griffiths, Gancz and Hostert2012) and extensive field visits all suggest that the observed disturbances are closely related to the forest restitution process (Irimie & Essmann Reference Irimie and Essmann2009; Mantescu & Vasile Reference Mantescu and Vasile2009). Widespread clear-cutting was witnessed after the first restitution law in 1991 (Nichiforel & Schanz Reference Nichiforel and Schanz2011). Most of the restituted forests (approximately 300 000 ha) were cleared in the following years by new owners (Mantescu & Vasile Reference Mantescu and Vasile2009). Similar trends occurred in the subsequent restitution phases following the respective laws in 2000 and 2005 (Ioras & Abrudan Reference Ioras and Abrudan2006). When the restitution process will be finalized, about two-thirds (50% by 2011, according to the Romanian Ministry of Environment and Forests) of Romania's forests will be in private ownership (Ioras & Abrudan Reference Ioras and Abrudan2006). Doubts about the permanence of the newly gained property rights, lack of knowledge regarding sustainable forest management and nature conservation principles (UNDP [United Nations Development Programme] 2004), as well as the chance to gain short-term profits during times of economic hardship all possibly catalyse the harvesting of restituted forests (Nichiforel Reference Nichiforel2010; Nichiforel & Schanz Reference Nichiforel and Schanz2011). Moreover, institutional adjustments necessary to cope with the new ownership structure lag far behind the actual rate of restitution (Irimie & Essmann Reference Irimie and Essmann2009).

Furthermore, lack of transparency, corruption, and inadequate legal proceedings likely resulted in illegal harvesting activities (Brandlmaier & Hirschberger Reference Brandlmaier and Hirschberger2005). Harvested timber volumes were higher than official statistics indicate (Bouriaud Reference Bouriaud2005) and estimates of wood volume and quality were incorrect (Brandlmaier & Hirschberger Reference Brandlmaier and Hirschberger2005). Economic hardship was identified as the main driver of unauthorized logging in the region, as illegal logging was highly correlated with unemployment in rural areas (Bouriaud Reference Bouriaud2005). Moreover, the intensity of illegal logging and over-harvesting has been found to be higher in private forests compared to state forests (Bouriaud Reference Bouriaud2005). Last but not least, lack of resources and limited staffing within protected areas (Knorn et al. Reference Knorn, Kuemmerle, Radeloff, Szabo, Mindrescu, Keeton, Abrudan, Griffiths, Gancz and Hostert2012) and in forest districts may hamper law enforcement of illegal harvesting in protected forests.

Protected area governance and old-growth forests

Nearly 80% of the remaining old-growth forests in Romania are found in protected areas, but 72% of the disturbances happened within their boundaries (Fig. 4d). Moreover, disturbance only differed slightly when comparing rates in protected (1.20%) versus unprotected (1.59%) old-growth forests. Only National Parks effectively prevented disturbances in old-growth forest (Fig. 4d).

Several reasons for the apparent shortcomings in protected area governance can be postulated. Although Romania has substantially increased its network of protected areas (Ioja et al. Reference Ioja, Patroescu, Rozylowicz, Popescu, Verghelet, Zotta and Felciuc2010), many still appear to be ‘protected on paper’ only (Börzel & Buzogány Reference Börzel and Buzogány2010). Although the establishment of the Natura 2000 areas was seen as an opportunity to direct biodiversity governance towards more inclusive policy-making, serious capacity problems undermined this idea (Börzel & Buzogány Reference Börzel and Buzogány2010). To date, owing to inappropriate administrations, the effective enforcement and implementation of conservation goals in Natura 2000 areas remains unachieved (Ioja et al. Reference Ioja, Patroescu, Rozylowicz, Popescu, Verghelet, Zotta and Felciuc2010). Moreover, wood harvesting in old-growth forests is strictly prohibited only inside the core zones of protected areas. Old-growth forests located outside these core areas, but inside buffer areas or completely outside protected areas, are exposed to legal harvesting conducted in accordance with forest management plans. The same applies for old-growth forests included in the Natura 2000 network, where the protection regime allows active forest management. According to forest management plans, by 2004 > 13 000 ha of old-growth forests had been included in the functional group of ‘productive forests’. This implies that some forest removal had been foreseen; with few exceptions, harvesting in old-growth forests in Romania is therefore in accordance with the law. The only true safeguard from potential harvesting for many remaining old-growth forest patches is their inaccessibility due to the lack of necessary infrastructure.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study highlights that intact old-growth forest landscapes continue to disappear in the temperate zone. In Romania, more than 2720 ha of old-growth forests were lost from 2000 to 2010 (1.3% of the total old-growth forest cover). Although our remote sensing approach could not distinguish between natural and anthropogenic disturbances, extensive field visits, interviews with foresters and local experts, and our own previous studies (Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Kuemmerle, Kennedy, Abrudan, Knorn and Hostert2012; Knorn et al. Reference Knorn, Kuemmerle, Radeloff, Szabo, Mindrescu, Keeton, Abrudan, Griffiths, Gancz and Hostert2012), suggest that natural disturbances alone cannot explain this loss. To the contrary, the observed decline in old-growth forest cover seems to result largely from logging.

Romania's protected area governance has not been successful in safeguarding these forests, confirming recent concerns about the effectiveness of nature protection in this region (UNEP 2007; Knorn et al. Reference Knorn, Kuemmerle, Radeloff, Szabo, Mindrescu, Keeton, Abrudan, Griffiths, Gancz and Hostert2012). Therefore, a continued monitoring of old-growth stands is necessary, and, as shown in this analysis, satellite image interpretation offers a promising and valuable tool for doing so. Besides strengthening protected area governance, equally important is the protection of old-growth forests against legal cutting, potentially necessitating changes to current forest management plans. We recommend that old-growth forests be incorporated into core protected areas (for example IUCN category Ia), given that aims and principles of protected areas are rated more highly than the guidelines and regulations of forest management plans. Alternatively, a direct protection through forestry technical provisions stipulated in forest management planning should also be considered.

In a more general context, local institutions should be established to promote the vertical and horizontal participation of multiple stakeholders to address the underlying social and economic challenges. In doing so, a sustaining multifunctional forest management and protected area governance may emerge, incorporating biodiversity, sustainable production, livelihoods and cultural heritage (Nijnik Reference Nijnik2004; Bizikova et al. Reference Bizikova, Nijnik and Kluvanková-Oravská2011). Additionally, incentives for private forest owners may encourage them to manage their forests sustainably and compensate them for the loss of opportunities, for example in the case of old-growth forests (Brandlmaier & Hirschberger Reference Brandlmaier and Hirschberger2005; Dragoi Reference Dragoi2010). Similarly, forest carbon management should be taken into account in biodiversity governance, as it offers alternative financial benefits (Olofsson et al. Reference Olofsson, Kuemmerle, Griffiths, Knorn, Baccini, Gancz, Blujdea, Houghton, Abrudan and Woodcock2011; FAO 2012). Furthermore, government interventions may be justified for biodiversity governance because forestry in countries that are going through the transition from communism to market-economics is often characterized by weak institutions and profit seeking (Nijnik Reference Nijnik2004). Finally, capacity–building and social learning (Schneider & Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1990) would be extremely valuable, including the raising of public awareness (Biriş & Veen Reference Biriş and Veen2005) with respect to the exceptional biodiversity and value of the ecosystem goods and services that Romania's old-growth forests provide.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge support by the European Union (VOLANTE FP7-ENV-2010-265104), the NASA Land Use and Land Cover Change Program of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (grant number NNX09AK88G), the Belgian Science Policy, Research Program for Earth Observation Stereo II (contract SR/00/133, as part of the FOMO project), the Czech Science Foundation (grant number GACR P504/10/1644) and the Einstein Foundation.