1. Introduction

The Malian climate in recent years has been characterized by changing conditions and a growing number of drought events with varying degrees of severity (Masih et al., Reference Masih, Maskey, Mussá and Trambauer2014). Although droughts are not extraordinary events in Mali, but rather are a natural part of the Western Sahel ecosystem, this low-income country is particularly vulnerable to such one-off climatic hazards. It is heavily reliant on its crop production sector which represents a main source of the livelihoods and food available to households. But this mainly rainfed agriculture is relatively unproductive and finds it difficult to meet the needs of the rapidly growing population. Living conditions are therefore highly precarious, especially in rural areas, characterized by endemic poverty, chronic food insecurity and poor adaptive capacities (Eozenou et al., Reference Eozenou, Madani and Swinkels2013).

In this context of substantial exposure together with high economic and social vulnerabilities, where any drought event may turn into a disaster with immediate but potentially long-lasting consequences for the economy and households’ welfare (de Sherbinin et al., Reference de Sherbinin, Chai-Onn, Giannini, Jaiteh, Levy, Mara and Trzaska2014; Shiferaw et al., Reference Shiferaw, Tesfaye, Kassie, Abate, Prasanna and Menkir2014; Gautier et al., Reference Gautier, Denis and Locatelli2016), this study seeks to assess the risk of droughts hazards in Mali and the potential benefits of some coping strategies. To our knowledge, such assessments have not been conducted previously for this country; extant studies mainly investigate the adverse consequences of projected long-run average temperature or precipitation trends and their associated impacts on yields or land or water availability (for example, Butt et al., Reference Butt, McCarl, Angerer, Dyke and Stuth2005; FAO, 2012; Giannini et al., Reference Giannini, Krishnamurthy, Cousin, Labidi and Choularton2017). But focusing on such mean shifts probably leads to underestimation of Mali's vulnerability to changing climatic conditions, which also depends on questions of variability and, in particular, of drought events.

We use a dynamic recursive computable general equilibrium (DRCGE) model including various specifications of the potential effects of droughts on the Malian crops sector. Such a framework seems indeed better adapted to an economy-wide analysis of agro-climatic shocks than other frameworks (for example, Ricardian or partial equilibrium analyses). Grounded on the Walrassian theory, it does not restrict the effects of shocks to agriculture alone, but also captures their influences in the overall economy, through linkages among prices, income, supply and demand. Moreover, with a dynamic specification, it also can generate time paths of the effects of successive shocks on economic and social variables. In economic literature, a growing number of CGE studies assess the vulnerability of low income countries, where agricultural production is weather sensitive and adaptive capacities are low. Most of them adopt a deterministic approach to long-run climate change related conditions (for example, Bezabih et al., Reference Bezabih, Chambwera and Stage2011; Calzadilla et al., Reference Calzadilla, Zhu, Rehdanz, Tol and Ringler2013; Gebreegziabher et al., Reference Gebreegziabher, Stage, Mekonnen and Alemu2016); others try to include variability features using stochastic or probabilistic scenarios (for example, Arndt et al., Reference Arndt, Robinson and Willenbockel2011; Arndt et al., Reference Arndt, Schlosse, Strzepek and Thurlow2014; Arndt and Thurlow, Reference Arndt and Thurlow2014).

However, very few studies focus on the risks that one-off climatic events represent for a country, by adopting either ex post historical approaches (for example, Al-Riffai et al., Reference Al-Riffai, Breisinger, Verner and Zhu2012) or ex ante hypothetical future approaches (for example, Pauw et al., Reference Pauw, Thurlow, Bachu and Van Seventer2011; Sassi and Cardacci, Reference Sassi and Cardacci2013). We chose in our study the latter approaches and simulate the impacts of various sequences of drought events in Mali over a 15-year period. We first focus on the effects of different categories of drought (mild, moderate, or intense) when they occur, as observed in past years in the country. But, because global warming threatens increases in intense droughts in the Sahel (Dai, Reference Dai2011; Zhao and Dai, Reference Zhao and Dai2017), we also investigate the effects of such potential changes for Mali. Finally, we explore some risk management strategies to determine how they might contribute to reducing the adverse consequences of droughts.

Section 2 details Mali's current vulnerability to drought hazards. Section 3 describes the main features of the DRCGE model and our hypotheses pertaining to defining the drought scenarios. Section 4 contains the results of the simulations, and section 5 outlines some effective coping policies that could be implemented in the country.

2. Background

Located on the southern edge of the Sahara desert, Mali is a land-locked country listed amongst the least developed economies and ranked near the bottom of the UN's human development index. The agricultural sector is the backbone of its economy, accounting for 41 per cent of the national gross domestic product (GDP) and employing 75 per cent of the workforce. However, this sector suffers many handicaps (FAO, 2012). Crop production is geographically highly concentrated in limited arable lands where climatic conditions are the most favorable, mainly in the Southern Sudanic zone and the inlet delta of the river Niger. It is also poorly diversified (see table 1). Cash-crop cultivates focus on cotton and rice. Subsistence crop production, by far the most important sector, is mainly devoted to millet, rice, sorghum, and maize, which represent nearly 80 per cent of total production and are the basic staples of the Malian diet. But with its rainfed, small-scale, traditional farming techniques, this subsistence sector provides particularly low yields.

Table 1. Share of different cultivars in total crop production in Mali (average values for 2001–2010

Source: Own calculations from FAOSTAT data.

The livestock sector, which includes millions of cattle, sheep and goats, is also of key importance, accounting for 14 per cent of Malian GDP. But most of this sector relies on small-scale, nomadic, pastoral systems with a low average rate of herd utilization and low productivity levels. In this context, living conditions of the fast-growing Malian population are particularly poor. Although Mali experienced an overall drop in poverty in the 2000s, it remains endemic, especially in rural areas, where 77 per cent of the overall population lives and which contribute 90 per cent to the national poverty rate. These rural areas are also affected by chronic malnutrition representing 84 per cent of the overall malnourished population of the country (Eozenou et al., Reference Eozenou, Madani and Swinkels2013).

In such a fragile situation, any shock to the agricultural sector thus can have serious implications for economic performance and households’ welfare. Figure 1 indicates, for instance, how prices and quantities of the main cereals cultivated and consumed in the country (millet, rice-paddy, maize and sorghum) have been particularly unstable over the last decades. Across a wide range of shocks (for example, locust invasions, livestock and plant diseases, price instability, political instability and insecurity), the risk related to climatic conditions may be the most severe (de Sherbinin et al., Reference de Sherbinin, Chai-Onn, Giannini, Jaiteh, Levy, Mara and Trzaska2014; Birkel and Mayewski, Reference Birkel and Mayewski2015; Padgham et al., Reference Padgham, Abubakari, Ayivor, Dietrich, Fosu-Mensah, Gordon, Habtezion and Traore2015; Sultan and Gaetani, Reference Sultan and Gaetani2016).

Figure 1. Annual variation of prices and of availability of main crops in Mali(a).

Mali's climate is indeed changing, along with the whole Western Sahel – one of the world's climate change hotspots (Turco et al., Reference Turco, Palazzi, von Hardenberg and Provenzale2015). In the past 50 years, Mali has experienced an increase in mean temperatures, changes in rainfall patterns, and variations in the onset and end of the growing season in many parts of the country (McSweeney et al., Reference McSweeney, New and Lizcano2010), with direct, adverse impacts on its yields, production, land dryness and water availability. Furthermore, Mali's climate has also been characterized by significant high annual variability, particularly noteworthy with regard to the steep increase in drought events (Dai, Reference Dai2011; Kotir, Reference Kotir2011; Masih et al., Reference Masih, Maskey, Mussá and Trambauer2014).

The primary effects of such events are well identified in economic literature – for example, lower yields, harvest failures, water scarcity, epizootic diseases, rises in food prices, food scarcity, exacerbated conflicts, rural-to-urban migrations (Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Ericksen, Herrero and Challinor2014; Gautier et al., Reference Gautier, Denis and Locatelli2016) – yet producing reliable estimations of past direct or indirect impacts in Mali is difficult. First, drought has a creeping nature, and its onset and end are sometimes difficult to determine. Second, each event is unique, depending on its location within the country, its period of occurrence and duration, and the potential co-occurrence of associated risks that increase its impact (for example, locust invasions). Third, there is a general lack of updated and accurate data on agricultural production or on long-run series of households’ living conditions indicators, which makes it even more difficult to evaluate the impacts of droughts on Malian households’ welfare. However, such events and the resulting year-to-year variations of agricultural production and prices clearly seem to be closely intertwined with poverty and food security issues. Eozenou et al., (Reference Eozenou, Madani and Swinkels2013) show for instance that, following the 2011 drought, the number of poor people in Mali increased by 610,000 (from 22 to 26 per cent of the population), due to both price increases and diminished cereal production.

3. Methodology

To generate time paths for the evolution of the Malian economy under different drought scenarios, we use the standard PEP-1-t model proposed by Decaluwé et al., Reference Decaluwé, Lemelin, Robichaud and Maisonnave2013. We describe the main features of this DRCGE model, as well as the modifications we made to include the effects of droughts on the Malian crops sector, in the online appendix. For the time horizon of our simulations, we deliberately set a relatively short 15-year period to exclude the potential effects of significant structural changes in the economy and thus maintain the consistency of the initial calibration of the model.

To define drought scenarios, we started with what has been observed in the country in recent decades. In scientific literature, drought can refer to deficits of precipitation (meteorological drought), negative anomalies in water levels (hydrological drought) or deficits of soil moisture (agricultural drought). Given the objective of this study, we chose here to focus on the latter and to build a National Agricultural Drought Index by using the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) improved with the Penman-Monteith (pm) equation.Footnote 1

In the last decades, PDSI-pm have been calculated monthly at a regional level for Mali. But, given that a drought affects agriculture mainly during growing seasons, we only retained the relevant months for each region, according to their respective crop calendars. Moreover, given that the regions do not account for the same weight in the nation's overall crop production, our National Agricultural Drought Index is a weighted average of the regional PDSI-pm. Results are presented in figure 2. They show that between 1982 and 2011 Mali experienced six intense (three extreme and three severe), four moderate and nine mild agricultural droughts.

Figure 2. Estimated historical weighted National Agricultural Drought Index for Mali.

On this basis, our drought scenarios are defined according to two key parameters: the intensity of each annual drought-related shock on the crop sector (on yields and on land stock) and the frequency of occurrence of events over the simulation period. We chose here a two-pronged approach. As a first step, we will run the model to evaluate the effects generated by three categories of events (intense, moderate and mild) when they occur as observed in recent years. Regarding their annual impacts, FAO data indicate that in the past ten years, these events have been characterized by annual average deviations from agricultural crop yields close to −27, −18, and −11 per cent, respectively, as well as by annual average losses of harvested lands close to −20, −4, and 0 per cent respectively.

Regarding the frequency of occurrence of each category of event, we have no choice but to develop a subjective prior distribution and consider a binomial distribution with a probability p. As observed in recent decades with the National Agricultural Drought Index, this probability has been close to p = 0.2, p = 0.13, and p = 0.30 for intense, moderate and mild droughts, respectively. For each scenario, we thus use these probabilities p to generate a significant number (100) of annual weather sequences, including events at random over the next 15 years. Each sequence will be simulated with the DRCGE model and compared with a business as usual (BAU) scenario, which is here defined by updating, from one period to the next, some constants and exogenous variables of the model (see online appendix). Within this framework, the mean of the 100 simulations thus will provide an average of the representative impacts of a ‘normal’ occurrence of each category of drought in Mali. It should be noted that such impacts will be evaluated ceteris paribus by comparing between what happens with and without the events, and that simulation results should not be understood as forecasts but only as differences of the evolution of the economic system that can be attributed to droughts.

As a second step, we will consider the impacts of increased frequencies of intense agricultural droughts. At this stage, we focus on these events because they are those for which farmers cannot really adapt, such that they represent greater risks for Malian agriculture. Furthermore, they are the threats most likely to increase due to ongoing global climate change (IPCC, Reference Field, Barros, Stocker, Qin, Dokken, Ebi and Midgley2012). However, climate models are not really able to predict them accurately, because the factors that influence a drought in the Western Sahel are complex (see for example, Burke and Brown, Reference Burke and Brown2008, or Zhao and Dai, Reference Zhao and Dai2017). In such an uncertain context, we thus rely on a conservative approach with distinct hypotheses about the future higher occurrence of intense droughts: optimistic (p = 0.27, n ≈ 4), medium (p = 0.33, n ≈ 5), and pessimistic (p = 0.40, n ≈ 6). Here again, we will simulate 100 annual weather sequences, generated at random, for each probability level. But, at this stage, results will be compared with those of the normal intense drought scenario and the mean of the 100 simulations thus will provide an average of the representative impacts of a ‘higher than normal’ number of intense droughts in the country.

4. Results

4.1. Scenarios with ‘normal’ occurrences of mild, moderate and intense droughts

Table 2 presents selected results of the simulations for the scenarios where mild, moderate and intense droughts occur at random as observed in past years. These results are comparable to what has been observed in Mali during the last decades. Though we obtained them with a different framework and methodology, they also align with the results of other CGE studies that have focused on extreme events (for example, Pauw et al., Reference Pauw, Thurlow, Bachu and Van Seventer2011, for Malawi; Al-Riffai et al., Reference Al-Riffai, Breisinger, Verner and Zhu2012, for Syria). We first note that, when it occurs, one mild, moderate and intense event causes an average one-off reduction from the BAU in the agricultural GDP of −5.4, −10.3, and −22.4 per cent, respectively, along with an increase in agricultural prices of 11.8 per cent, 24.2 per cent, and as much as 58.9 per cent in the intense drought scenario. These effects cascade down through the entire national economy.

Table 2. Selected average impacts of different categories of drought occurring with a‘normal’ frequency over a 15-year period (deviation in % from the BAU scenario)

Source: Own calculations with GAMS software (results computed from the simulations of 100 randomized drought sequences for each category of drought).

In a drought year, the real GDP deviates from the BAU by −2.8, −5.6, and −13.1 per cent, and the price index shifts by 5.1, 10.6, and 25.9 per cent in the three respective scenarios. In this context, social indicators also degrade sharply. Drought events have strong impacts on real income per capita for all households, and this decrease is logically greater in rural than in urban areas. The effects on food security are particularly striking: Due to decreased agricultural production, per capita supplies of foodstuffs fall by −4.4, −8.0, and −16.7 per cent, depending on the drought intensity. Similarly, as a result of food price increases and income per capita decreases, per capita food consumption decreases, especially in rural areas (−6.3, −11.9, and −25.3 per cent) relative to urban areas (−2.5, −5.2, and −12.5 per cent). Finally, each drought event exerts a strong impact on annual migration processes (15.8, 30.9, and 66.9 per cent), because lower purchasing power in rural areas (cf. urban areas) induces households to migrate to cope with the drought.

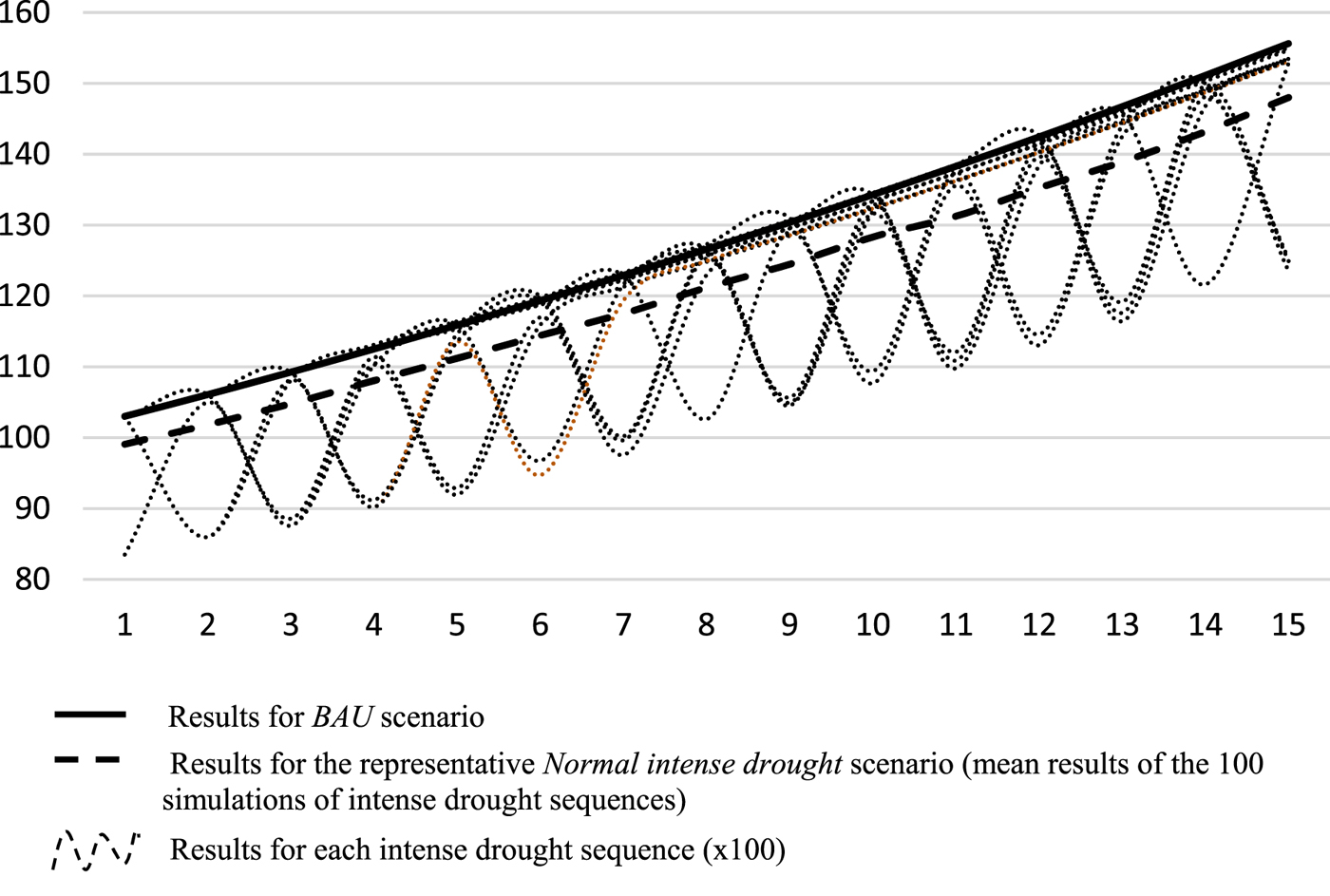

If we focus now on the average deviation from the BAU scenario that each sequence of drought generates over the period, it should be noted that, although they have lesser one-off annual impacts than moderate droughts, mild droughts generate higher mean impacts over the period, because they are more numerous. For example, relative to the BAU scenario, successive events cause an average decrease in the national GDP of −0.8, −0.7, and −2.6 per cent and in the agricultural GDP of − 1.6, −1.4, and −4.5 per cent, for mild, moderate and intense drought scenarios, respectively. Such average effects are illustrated, for instance, in figure 3 for the agricultural GDP under the intense drought scenario. The impacts on prices are also powerful; on average, each sequence of events prompts relative average increases in national prices (1.5, 1.4, and 5.2 per cent) and agricultural prices (3.5, 3.2, and 11.8 per cent). In this context, households’ welfare degrades sharply, with strong average decreases of real income per capita for rural households (−1.2, −1.1, and −3.6 per cent) and urban households (−0.3, −0.3, and −1.2 per cent), as well as degraded food security indicators and increased migration flows.

Figure 3. Evolution of real agricultural GDP for the BAU and 30 randomized sequences of intense droughts with ‘normal’ frequency (base of 100 at initial equilibrium).

4.2. Scenarios with increased frequency of intense droughts

Table 3 presents selected results of the simulations for the scenarios assuming different increases in the number of intense droughts. To separate out the effects due to changing climatic conditions from the effects due to ‘normal’ occurrences of intense droughts, it should be remembered that we now compare the simulations’ results with the representative normal intense drought scenario estimated in the previous section. These results show how the higher than ‘normal’ number of intense droughts would increase their average impacts on the macroeconomic and welfare indicators, according to the level of climate variability considered.

Table 3. Selected average impacts of intense drought sequences over a 15-year period under different hypotheses for events’ frequency (deviation in% from the Representative normal intense drought scenario)

Source: Own calculations with GAMS software (results computed from the simulations of 100 randomized drought sequences for each probability of occurrence p).

In the most unfavorable scenario, an average number of six events over the next 15 years (p = 0.40) would cause mean deviations of −2.4 per cent in the national GDP (−4.5 per cent for agricultural GDP) and 4.6 per cent for national prices (9.0 per cent for agricultural prices). Similar shifts would emerge among the social indicators. Rural households would suffer an average decrease in their income per capita of −3.5 per cent and diminished food security indicators (−5.1 per cent for food access index, −2.3 per cent for food availability), along with increased migration flows (9.9 per cent).

5. Exploring drought adaptation strategy options

There is little Malian farmers can do to alter their drought exposure, yet some coping strategies aimed at reducing their vulnerability could help minimize, over time, the adverse consequences of the events. In agro-economic literature, a broad spectrum of options has been identified as efficient in drought-prone areas: adopting suitable farming practices enables the restoration of degraded drylands and increased soil fertility (Zaï pit technique for instance), adjusting cropping patterns and planting date, intercropping different crops species, selecting drought tolerant varieties of crops, improving water management, using weather forecasts or early warning systems, etc. Most of these strategies are already used by farmers in places to deal with drought hazards. But, in the context of an increase in the occurrence of droughts, these strategies would deserve to be fostered to enhance resilience and strengthen adaptive capacities of farmers (see, for instance, Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Jalloh and Diouf2014; Shiferaw et al., Reference Shiferaw, Tesfaye, Kassie, Abate, Prasanna and Menkir2014; USAID, 2014; Wilhite et al., Reference Wilhite, Sivakumar and Pulwarty2014; Giannini et al., Reference Giannini, Krishnamurthy, Cousin, Labidi and Choularton2017).

In this spirit, following the Climate-Smart Agriculture Framework, a prioritization process has recently been led in Mali (from October 2014 to October 2015) in order to identify the best practices that could transform and reorient Malian agricultural systems in the face of climate change (Andrieu et al., Reference Andrieu, Sogoba, Zougmore, Howland, Samake, Bonilla-Findji, Lizarazo, Nowak, Dembele and Corner-Dolloff2017). We choose here to focus on three promising options which are also part of the Malian National Policy on Climate Change (AEDD, 2011) and of the Malian National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2011 (see République du Mali, 2007, or Padgham et al., Reference Padgham, Abubakari, Ayivor, Dietrich, Fosu-Mensah, Gordon, Habtezion and Traore2015): a wider use of drought-tolerant crop varieties, an improvement of drought early warning systems and an extension of irrigation capacities.

5.1. Fostering the use of drought-tolerant crop varieties

For a long time, selecting crop varieties better adapted to drier conditions and to a shorter agricultural calendar has been a strategy used by West-African farmers to manage drought risk. Such traditional breeding has, over time, provided a lot of varieties with higher drought tolerance and stable productivity. However, with the ongoing higher climate variability, a more systematic use of new varieties now appears necessary (see, for instance, Shiferaw et al., Reference Shiferaw, Tesfaye, Kassie, Abate, Prasanna and Menkir2014; USAID, 2014; Wilkinson and Peters, Reference Wilkinson and Peters2015). Recently, new agronomical technologies based on genetic improvement (for instance, marker-assisted breeding or genetic engineering) have opened great opportunities for plant selection and, in many parts of Africa, several national and international research institutions have scored important gains in improving the drought tolerance of major crops (for an overview, see Xoconostle-Cazares et al., Reference Xoconostle-Cazares, Ramirez-Ortega, Flores-Elenes and Ruiz-Medrano2010; Shiferaw et al., Reference Shiferaw, Tesfaye, Kassie, Abate, Prasanna and Menkir2014; or Sultan and Gaetani, Reference Sultan and Gaetani2016). In Mali, a lot of early and resilient varieties of main crops (millet, sorghum, cotton, sesame, rice, maize, corn, cowpea, groundnut or market gardening) have, for instance, already been identified by the Institute of Rural Economics for different agro-ecological areas of the country (FAO, 2018). But, although they demonstrate a certain tolerance compared to climatic variations, they are still currently little used by farmers (CGIAR, Reference Walker and Alwang2015).

In this context, our first drought adaptation scenario considers an extension of the use of such drought-tolerant crop varieties in the country. This scenario relies on three main hypotheses. First, we chose to consider that the introduction of new cultivars only concerns the main crops which are the basic staples of the Malian diet (millet, rice, sorghum and maize), that is, 80 per cent of total crop production. Second, regarding the yield gains that could be expected with these new varieties, we chose to rely on a conservative approach. Although substantial progress has been made in the assessment of the potential for adaptation of new cultivars in West Africa, their responses to changing climatic conditions remain largely uncertain. Large gaps exist in studies based on process-based crop models because of a lack of sufficient data for accurate validation of models or inappropriate assumptions for low intensive agricultural systems (see, for instance, Hertel and Lobell, Reference Hertel and Lobell2014; Sultan and Gaetani, Reference Sultan and Gaetani2016).

Moreover, varietal change doesn't automatically result in substantial average productivity change without complementary good agricultural practices. CGIAR, (Reference Walker and Alwang2015) indicates for instance that, for most African countries, the use of shorter duration varieties that escape drought could lead to potential productivity gains of 30–50 per cent in high production potential environments, where soil fertility is not as constraining and where agriculture is supported by favorable input policies. But, in most rainfed environments, where agricultural input (such as chemical fertilizers or pesticides) are not readily available, it seems more reasonable to expect relative yields of 10–30 per cent. In the most unassured production zones, the increase could even be as small as 10 per cent. In this context, given the low production potential environment of the crops sector in Mali, our scenario assumes a conservative average yield gain attained from using improved varieties of 20 per cent.

Third, we also consider different adoption rates by farmers (that is, different percentages of land under use for the new cultivars) ranging from 25 to 100 per cent at the end of the 15-year period. The adoption of new crop varieties by farmers depends indeed on various socio-economic and institutional considerations at the local and national level. For example, it could not be achieved without a considerable political commitment in awareness campaigns, technical assistance, strengthening of seed systems to ensure an availability and affordability of seeds, improving of access to credit for farmers (see, for instance, Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Ericksen, Herrero and Challinor2014).

Table 4 depicts some potential buffering effects of such a strategy under the different climatic scenarios for intense droughts. For conciseness, we only present the results for rural areas, which are the areas most affected by drought events. Results show that, as expected, a wider use of new crop varieties could reduce drought-related impacts according to the extent of land surface considered. In some cases, the average impacts over the period of each drought sequences could even be overcome. Under the normal scenario, the negative impacts of current climate variability on agricultural GDP, rural income and rural food security could be neutralized from a threshold level between 75 and 100 per cent of land area sown with new varieties. Under climate change scenarios, the mean impacts on agricultural GDP of a higher than ‘normal’ number of intense events could be neutralized at land surface thresholds close to 50 per cent under the optimistic scenario and between 75 and 100 per cent under the medium scenario. However, this neutralization threshold cannot be achieved under the pessimistic scenario.

Table 4. Selected effects of an improved crop variety substitution strategy under various drought scenarios (% of reduction of drought impacts compared with the same scenario without adaptation strategy)

aResults for deviations from the BAU scenario.

bResults for deviations from the representative normal intense drought scenario.

Source: Own calculations with GAMS software (mean results computed from the simulations of 100 randomized drought sequences for each scenario).

In turn, rural households would benefit from the strategy though, with potential offsets of the average negative impacts of additional droughts on their real income and food security for a neutralization threshold of 50 per cent for the optimistic scenario, and between 75 and 100 per cent for the medium scenario. These thresholds would, however, never be achieved for the pessimistic scenario, even if the adverse impacts of an increased number of droughts diminished substantially compared with the scenario without any cultivar adaptation. Results in table 5 show that such a strategy could also be worthwhile according to cost-benefit criteria, although it should be stressed that estimating this cost is quite difficult. We use the data from the Technology Needs Assessment report prepared by Mali for UNFCC (Ré)publique du Mali, 2012 which assessed average costs of using new varieties; on this basis, an achievement of 100 per cent rate of utilization of new cereals variety could, for instance, represent an overall investment of US$52 million. On this basis, whatever the scenarios, the results show that each dollar invested in the use of new crop varieties would generate an average net return close to US$100 in terms of national GDP.

Table 5. Cost-benefit analysis of an improved crop variety substitution strategy under various scenarios for intense droughts

aGains in real GDP over the period compared to the BAU scenario for normal scenario or to the representative normal intense drought scenario for climate change scenario.

Source: Own calculations with GAMS software (mean results computed from the simulations of 100 randomized drought sequences for each scenario).

5.2. Extending the use of drought early warning systems

Drought early warning systems (EWS) are designed to identify climate and water supply trends and thus to detect the emergence or probability of occurrence and the likely severity of a drought event. Multiple studies clearly demonstrate that, by providing farmers the timely and reliable information necessary to make appropriate decisions regarding the management of water and sowing, EWS could be a key element for reducing drought disaster risk (see, for instance, Pulwarty and Sivakumar, Reference Pulwarty and Sivakumar2014; Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Jalloh and Diouf2014; Shiferaw et al., Reference Shiferaw, Tesfaye, Kassie, Abate, Prasanna and Menkir2014; Wilhite et al., Reference Wilhite, Sivakumar and Pulwarty2014).

In Mali, the national meteorological agency (Mali-Météo) and the Système d'Alerte Précoce (SAP) are the key organizations responsible for such early warning and disaster risk management. SAP monitors the food availability situation, determines areas at risk and identifies vulnerable populations. Mali-Météo (together with AGRHYMET, the regional center of the Permanent Interstates Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel), has the mandate to provide forecasts of seasonal rainfall for different geographical zones as well as other potential climate information relevant for rainfed agriculture (onset and cessation dates of the rainy season, duration of dry spells during the critical growth stages of the major crops, etc.). But Mali-Météo is currently experiencing a precarious financial situation and an obsolescence of its stations network and therefore faces difficulties in fulfilling its tasks.

In this context, our second adaptation scenario considers an improvement and a wider use of this drought EWS in Mali. Here again, we use a conservative approach. First, we assume a progressive geographical coverage of the EWS with different rates of adoption by farmers ranging from 25 to 100 per cent at the end of the 15-year period. Second, using data from the Technology Needs Assessment report for Malian NAPA (Ré)publique du Mali, 2012, we assume that, during an event, using an EWS provides an average yield gain of up to 30 per cent compared to a situation where it is not used.

Table 6 presents some potential effects of the strategy under scenarios for intense droughts. Here again, these results show that such a strategy could reduce the potential adverse consequences of droughts. However, compared to the previous strategy, improving the use of an EWS has lower buffering effects because it is only relevant for a year of occurrence. Under the normal scenario, for a geographical coverage rate of 100 per cent, the average impacts of the drought sequences over the period on agricultural GDP or prices could for instance be reduced by 17 and 22 per cent respectively. Under changing climatic conditions scenarios, they would be reduced by 42 and 58 per cent for the optimistic scenario, by 32 and 43 per cent for the medium scenario and by 26 and 34 per cent for the pessimistic scenario.

Table 6. Selected effects of a drought early warning system improvement strategy under various drought scenarios (% of reduction of drought impacts compared with the same scenario without adaptation strategy)

aResults for deviations from the BAU scenario.

bResults for deviations from the representative normal intense drought scenario.

Source: Own calculations with GAMS software (mean results computed from the simulations of 100 randomized drought sequences for each scenario).

Table 7 evaluates the effect of the policy with regard to costs-benefit criteria. In the absence of better information, the cost of the strategy has been estimated using data from the Climate Risk and Early Warning System (CREWS) initiative.Footnote 2 In 2017, together with the World Bank and the Green Climate Fund, the CREWS initiative indeed launched a modernization project of the Malian EWS (including capacity building and development of Malian institutions as well as improvement of hydro-meteorological and warning infrastructures or enhancement of service delivery and warnings to communities at risks) and has estimated that a full modernization of the Malian EWS system would require US$45 million (CREWS, 2017). On this basis, results show the strategy would potentially be worthwhile. Its profitability would be greater as the number of drought events is supposed to increase over the period. For instance, one dollar invested in order to achieve a 100 per cent coverage rate of farmers could generate a national real GDP gain of about US$48.9 under the pessimistic scenario and US$21.6 under the normal scenario. These results align with the studies (for instance, Hallegatte, Reference Hallegatte2012) which argue that, because some of the most expensive components of EWS already exist (e.g., earth observation satellites, global weather forecasting system), the investments needed to improve EWS are relatively modest compared to the expected benefits.

Table 7. Cost-benefit analysis of a drought early warning system improvement strategy under various scenarios for intense droughts

aGains in real GDP over the period compared to the BAU scenario for normal scenario or to the representative normal intense drought scenario for climate change scenario.

Source: Own calculations with GAMS software (mean results computed from the simulations of 100 randomized drought sequences for each scenario).

5.3. Extending irrigation capacities

By extending the growing season in normal years, providing a supplemental water supply at critical times in the crop's life cycle during drought periods, or even allowing off-season cultivation, irrigation infrastructures are likely not only to increase mean agricultural yields but also to reduce their fluctuations and to remove the farmers’ dependence on precipitation. But irrigation capacities still remain limited in Mali (only 5.3 per cent of land) despite a huge estimated irrigation potential (about 2.2 million hectares).

In this context, our third drought adaptation scenario considers an extension of irrigated land (at the expense of unirrigated land) over the next 15 years. However, the technical and financial difficulties associated with this policy led us to adopt a pragmatic approach. First, we only consider the objective of 560,000 hectares (8.1 per cent of total Malian harvested area) which have been identified as being easily irrigated with persistent surface water resources by the FAO. Second, we consider different levels of achievement of this objective, ranging from 25 to 100 per cent at the end of the 15-year period (see, for instance, Beyene and Engida, Reference Beyene and Engida2013, for a similar approach). In each case, the extension of irrigated lands is assumed to be progressive over the period. Third, we only consider an extension of rural small-scale irrigation techniques.

Currently, a majority of Malian irrigated lands (86 per cent) benefit from large-scale dam-based systems. But such technology needs huge initial investment costs and human resources or equipment for its functioning. In comparison, small-scale village level technologies, including mechanical lifting of water from source (micro-dam, groundwater or run-off-river) as well as distribution systems to plots (gravity irrigation, Californian system, sprinkling system or drip irrigation system)Footnote 3 appear relatively easier to finance and to manage by rural communities and have often been shown to be less expensive and more efficient than large-scale irrigation systems (You et al., Reference You, Ringler, Wood-Sichra, Robertson, Wood, Zhu, Nelson, Guo and Sun2011; Qureshi and Shoaib, Reference Qureshi and Shoaib2016). The Malian Small-Scale Irrigation Promotion Programme 2012–2021 provides us the main data for our scenario. It indicates that equipping 1 hectare could generate a threefold average increase of land productivity for an average cost of approximatively US$8,000 (Ré)publique du Mali, 2012.

Table 8 presents some potential effects of such a strategy under the different climatic scenarios for intense droughts. They indicate that increasing irrigated land area could not only contribute to improving economic and social indicators but also to entirely compensating for the current effects of intense droughts and potential effects of future increases in the number of events. Under the normal scenario, reaching a 75 per cent level of the irrigation objectives would be sufficient to offset almost all the negative effects that droughts currently generate in Mali. Similarly, under the optimistic (respectively medium and pessimistic) climate change scenario, reaching a 50 per cent (respectively 75 and 100 per cent) level would neutralize the additional adverse effects generated by an increasing number of events. Morever, table 9 shows that, although very expensive, this strategy could remain profitable. Whatever the scenario, the average gain in national GDP would still exceed the costs of the policy, even if this profitability is sharply reduced compared to the two previous adaptation strategies.

Table 8. Selected effects of an irrigation extension strategy under various drought scenarios (% of reduction of drought impacts compared with the same scenario without adaptation strategy)

aResults for deviations from the BAU scenario.

bResults for deviations from the representative normal intense drought scenario.

Source: Own calculations with GAMS software (mean results computed from the simulations of 100 randomized drought sequences for each scenario).

Table 9. Cost-benefit analysis of an irrigation extension strategy under various scenarios for intense droughts

aGains in real GDP over the period compared to the BAU scenario for normal scenario or to the representative normal intense drought scenario for climate change scenario.

Source: Own calculations with GAMS software (mean results computed from the simulations of 100 randomized drought sequences for each scenario).

6. Conclusion

In Mali's current context, marked by great exposure and vulnerability to agricultural drought, this study uses a DRCGE model to assess the potential risks of such events for this country, as well as to evaluate some adaptation policies. With simulations of various drought scenarios over a 15-year period, we show first how the impact on crop production of each mild, moderate and intense drought currently experienced by the country contributes to hindering its economic performance and considerably degrading its households’ welfare. Furthermore, we depict how these negative impacts likely will be aggravated by the increased number of intense drought events threatened by global climate change. However, we show that there are some options for Mali to cope with these adverse current or future climatic conditions, if it were to implement coping strategies such as adopting drought-tolerant crop varieties, using drought early warning systems or extending irrigated areas.

These results offer some indications of Mali's vulnerability to agricultural drought and its options for adaptation, yet some caution is required in terms of interpreting their estimated absolute magnitudes. First, our economy-wide analysis does not really account for regional differences within the country. Moreover, the low disaggregation of the agricultural sector in our model, which is constrained by the structure of the Malian SAM, prevents us from assessing more detailed potential impacts of drought events. Second, our methodology does not fully address uncertainty regarding the nature and amplitude of future climate variability or regarding its effects on agriculture. Third, our modelling framework cannot account for all the effects associated with a drought event; certain collateral effects (for example, health risks, conflict over water resources, external migrations) clearly could alter economic performance and households’ welfare.

Fourth, although some autonomous responses to drought are endogenously determined in the DRCGE model (accumulation dynamics, inter-sectoral or inter-regional migrations, changes of relative prices or patterns of consumption), the reality may be more flexible. For example, in addition to government climate policies, farmers could employ a wide range of autonomous coping strategies (increasing self-consumption, liquidating productive assets, changing crop patterns or agricultural calendars, etc.), which do not appear in our economy-wide model but that are options already available in Mali. Fifth, the coping strategies that we consider include various institutional, social, technological and financial dimensions that our macro-level economic CGE approach cannot address exhaustively. For instance, we did not examine the critical question of funding, which was beyond the objectives of our study, although it is an important policy question in the Malian context of reduced fiscal space available for the government, or lack of financial resources of farmers.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X19000160