The perennial complaint from publicly listed firms is that their strategy and performance is evaluated over an increasingly short-term time horizon due to the oversight and undue influence of capital markets. Family ownership and control diminished in the post-World War II era in the United Kingdom as professional managers replaced family members in the day-to-day running of former family organizations. However, since the 1980s, professional managers have operated increasingly under the constraint of the bankers and investors whose patronage they seek to retain; a phenomenon encapsulated in the term “financialization.” Footnote 1 Against this backdrop, corporate strategies that might otherwise make sense in the fullness of time may never come to fruition: activist shareholders and financial entrepreneurs make their presence felt in the boardroom, prompting frequent and abrupt changes in strategic direction.

Whitbread is a UK “blue chip” firm with a long and proud heritage in the UK brewing industry. The name is synonymous with its founder Samuel Whitbread (1720–1796) and the brewing firm he established in London in 1750. It was from this base that successive descendants of the family built a national brewer–retailer with operations spanning various leisure industries. The era of direct family involvement in the firm ended in 1992 with the retirement of Sam Whitbread as chairman. Only a decade later, Whitbread had exited both brewing and more traditional pub-retailing activities. The Whitbread of today is a leisure retailer with activities centered on the coffee shop brand Costa Coffee; budget hotel chain Premier Inn; and a small portfolio of restaurants with brands including Beefeater Grill, the first of which was opened in 1974. Footnote 2

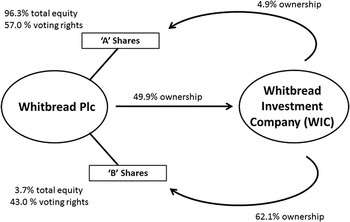

This article focuses on a key period in the evolution of the firm in the post-World War II era. The institutional setting for the analysis is the 1948 Companies Act legislation and the evolving market for corporate control in the 1950s. It was during this decade that the UK brewing industry and its traditional family firms came increasingly to the attention of financial entrepreneurs. Whitbread assumed a statesman-like protector status for a group of smaller family-oriented regional brewers whose independence was compromised. It formed the so-called Whitbread Umbrella as a novel structural arrangement that incorporated a dual-voting shareholding structure aligned to a controlling interest in the publicly listed Whitbread Investment Company (WIC), an investment trust that housed minority shareholdings in some twenty regional brewers. The umbrella protected the Whitbread family legacy as well as Whitbread’s aim to be a national brewer–retailer. The structure remained intact during the mergers and acquisitions frenzy of the 1960s, from which the “Big 6” national brewers—Allied Breweries, Bass, Courage, Scottish & Newcastle, Watney Mann, and Whitbread—came to dominate the UK brewing industry Footnote 3 ; as well during the leveraged buyout era of the 1980s, when Whitbread’s major UK competitors, Allied-Lyons and Scottish & Newcastle, came to the attention of aggressive suitors, most notably the Australian conglomerate Elders IXL. Footnote 4 The umbrella was dismantled in the early 1990s in the immediate aftermath of the competition policy intervention, known as the 1989 “Beer Orders.” This ended the dominance of the Big 6, which at the time accounted for some 75 percent of UK beer production. Footnote 5 By this stage, not only had the umbrella outgrown its original purpose, but also institutional investors were pressing increasingly for the residual former family firms to enfranchise non-voting or reduced-voting shareholders.

This study of strategic decision making in an evolving institutional environment seeks to inform the long-term versus short-term performance debate that continues to challenge academics and practitioners alike. Its theoretical grounding is in the ownership and control literature that guides business history scholarship and contemporary strategic management and finance. This article first charts Whitbread from its offer for sale on the UK stock market in 1948, with a dual-voting shareholding structure, and then it gives an account of how and why the Whitbread Umbrella was completed in 1956 with the formation of WIC. The relationships within the umbrella, and how it operated from a strategic and behavioral perspective, are important features of the study, as is describing Whitbread’s wider role in an industry that was struggling to adapt to the increasing influence of the financial markets. In concluding, the article assesses whether Whitbread’s survival, and subsequent strategic transformation from its brewing heritage, can be attributed to the protection of the umbrella, which afforded Whitbread the ability to ignore short-term institutional factors in favor of carving a long-term growth trajectory that underpins the firm today.

Background

The study of post-World War II Whitbread, and the structure and operation of the Whitbread Umbrella, engages with two key discussions in the business and management literature: the status of family firms in social and economic development, given their distinct organizational attributes, and the role of the capital markets in supporting or constraining firm decision making. With histories that transcend sequential financial and economic crises, family firm research is a contemporary theme in the general management literature. Footnote 6 For business historians, organizational structure and performance have guided empirical study since the scholarship of Alfred Chandler. Footnote 7 The pros and cons of the U.S.-style multidivisional, or M-form, structure emanating from Chandler’s analysis of post-World War II U.S. multinational corporations (the “Harvard Program”) have been studied extensively in other institutional settings, including in the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Italy. Whittington and Mayer have charted the continuing progress in ownership, management, and performance in Europe after 1970. Footnote 8 These authors support the continuation of Chandler’s theory of the contemporary organization, Footnote 9 at a time when some have queried whether its predictions of superior financial performance are supported by empirical analysis of Chandler’s own exemplary firms. Footnote 10

The Chandlerian thesis, considered by some institutional theorists as a coincident correlation between managerialism and diversification, Footnote 11 is that one of the most significant economic phenomena of modern times is the transformation of business enterprise from personally managed partnerships to large firms that are administered through extensive hierarchies of managers. Footnote 12 Such an organizational design has an analogy to conventional military practice, where structure follows from strategy, with the latter reserved for, and devised by, a small group of senior officers for disciplined implementation by the lower ranks. Footnote 13 In contrast to the United States, family enterprise and control persisted in the United Kingdom, it has been claimed, with adverse consequences for British economic development, Footnote 14 particularly in creating organizations capable of maintaining and expanding their positions in technologically supported and capital-intensive industries that underpin internationalization. Footnote 15

Although there was no legal constraint to the adoption of a U.S.-type corporate form, Footnote 16 the failure to change direction, management, and ownership prior to World War I or World War II owes much to the high proportion of shareholdings that remained in the hands of the original partners of Victorian firms. Footnote 17 In certain industries and geographic areas, an economic aristocracy of interlocking business interests emerged. Footnote 18 In several key sectors, such as brewing and shipbuilding, founding families retained considerable power and influence right up to 1948. Footnote 19 All but a small number of the largest firms were either family managed, albeit with a large base of individual shareholders afforded voting rights, Footnote 20 or were federations of family firms legally unified under the control of a holding company that acted as the conduit for “gentlemanly” competition. Footnote 21

Three theoretical frameworks—Principal–Agent Theory, Stewardship Theory, and Resource-Based View (RBV)—both join and divide current opinion regarding the specificities of family firms and family firm governance. Footnote 22 Principal–Agent (or Agency) Theory is the normative approach to assessing the impact of specific types of owners on strategic decisions. Footnote 23 Drawing on the seminal work of Berle and Means in the 1930s, Jensen and Meckling’s Reference Jensen and Meckling1976 treatise anchors much of the contemporary financial and economic analysis of ownership structures. Footnote 24 Although founder-managed firms are considered effective in managing relational contracts, this is at the expense of an increased cost of capital attributable to the reduction or elimination of the monitoring and disciplinary influence that the capital markets provide. Footnote 25

Stewardship Theory reflects a softer, or potentially more strategic, framework for organizational analysis, with its underlying premise of goal alignment and trust reflecting family firms’ organizational social capital that exceeds their own family domain, Footnote 26 as a result of their interactions with diverse external stakeholders and their position in family networks. Footnote 27 From this perspective, Agency Theory fails to incorporate the “special role of family principals” in the pursuit of noneconomic objectives. Footnote 28 There is a complex relationship between family influence and business performance that is related not just to the riskiness of the external environment, but also to the degree to which a business and its primary executive actors are socially embedded in a family. Footnote 29

To bridge the divide between these two competing perspectives, scholars have been drawn to the extensive literature of the Resource-Based View for theoretical guidance and a deeper understanding of why family firms are ubiquitous and demonstrate such longevity. Footnote 30 Anchored in the work of Edith Penrose, and the strategic management literature of the 1980s, Footnote 31 the RBV is one of the core theories in strategic management. Its theoretical premise is that sustainable competitive advantage is grounded in the availability of idiosyncratic strategic resources and capabilities of firms, and how these resources and capabilities are deployed.

The debate continues as to whether family-owned/-controlled firms or professionally managed publicly listed firms are more efficient allocators of capital and better business models, despite numerous studies based on a range of methodologies that have used datasets from both developing and advanced economies. Footnote 32 At the very heart of the debate is the nature of, and efficacy of, diversification and the associated impact on earnings volatility. Footnote 33 When firms are burdened by transient ownership, they are under pressure to focus on consistency and the delivery of positive quarterly earnings. Footnote 34 In contrast, family ownership, with the associated protection from the market for corporate control, can promote or encourage extreme risk aversion that restricts investment decisions in the interest of protecting the family legacy. Footnote 35 Yet, their very endurance and ubiquity, if not role in the social and economic landscape, argues their case. In the United States, family firms account for some 80 percent of the workforce, and approximately half of the gross national product. Footnote 36 In Germany, they are “hidden champions” and world leaders in their chosen industries. Footnote 37 In France, one of the largest and most successful industrial groups is the family-controlled Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy, with its strong links to the dynastic banking empire of Lazard Frères. Footnote 38 This latter example illustrates how the structure of the capital markets is especially important in explaining the persistence of forms of personal capitalism. Footnote 39

One of the mechanisms firms have historically adopted to protect their legacy family interests, while retaining the benefits of a public listing, is an ownership arrangement with multiple classes of shares with differential voting rights. Such complex arrangements in the United Kingdom trace their history to the late 1800s and to the issue of preference or debenture stock to raise funds without ceding absolute voting control. Footnote 40 This created a sizeable number of ordinary shareholders who could be called on to subscribe additional capital if needed, in return for some say over how the firm was managed. Footnote 41 Parallels are in the pyramid structures, common in Europe, where one family controls multiple firms through a chain of ownership. Footnote 42 Although now more likely to be associated with emerging market family networks, Footnote 43 as well as Canadian and European largely family firms, Footnote 44 dual-voting share structures have emerged more recently in the United States, particularly with U.S. technology entrepreneurs who have sought to expand their firms without ceding control to outsiders. Footnote 45 Notwithstanding criticism from corporate governance specialists, the empirical evidence is not conclusive that these multiple class-voting structures have destroyed shareholder value. Footnote 46

The Evolution of the UK Brewing Industry Structure

Traditionally, the UK brewing industry was vertically integrated, with brewers controlling through a property or loan tie the greater proportion of the UK’s pubs. This integration secured the distribution of their beer, and it emerged as the dominant operating and organizational structure in eighteenth-century London, with half of London’s publicans tied through loan arrangements to brewers by 1830. Footnote 47 Direct ownership of pubs in London was less common, with firms such as Whitbread and Barclay Perkins largely shunning this as part of their “high-minded, free-trade stance.” Footnote 48 Changes in licensing in the late-nineteenth century saw brewers acquire chains of pubs, which were operated usually by third-party tenants. Footnote 49 The wholesale acquisition of pubs in the 1880s and 1890s was part of a scramble for scarce property assets that emanated from legislation empowering the issue of future public house licenses to local magistrates. Footnote 50 The scale of finance required by brewers to acquire public houses and invest in new brewing technology exhausted the funding available from the earlier extension of partnerships to bankers and financiers. Footnote 51 The exuberant new issues market in the 1880s and 1890s underpinned public interest in the industry, Footnote 52 which was brought to public attention in the “unprecedented” stampede to obtain prospectuses that accompanied Guinness’s 1886 offer for sale. Footnote 53 For brewers seeking outside capital, investors found comfort in the collateral backing of the pub estates. Footnote 54

A restrictive licensing regime shaped the structure and operation of the UK brewing industry for more than a century, as the brewers consolidated ownership such that they controlled more than half of all pubs by 1967, Footnote 55 although the type of ownership—tenanted or managed—varied considerably by region. Footnote 56 In contrast to the London brewers (where with the exception of Whitbread, Barclay Perkins, and Watney Mann, through their association to the “improved public house movement” Footnote 57 ), the large Midlands and Northern brewers Ansells, Mitchells & Butlers, and Newcastle Breweries were the “giants of the managerial system.” Footnote 58 Further, the Big 6’s stranglehold that prompted two antitrust inquiries in 1969 and 1989 was apparent in the supposed “free trade” of some 34 percent of beer consumption also being tied through brewery loans. Footnote 59 Although the brewers argued that this element of the market was genuinely free, UK regulatory authorities did not share this view. Footnote 60

The fact that the industry survived into the 1990s with a traditional organizational design owed as much to the political influence of “The Beerage” of family firms that controlled the industry Footnote 61 as to an ineffective market for corporate control that tended to deter debt-fueled hostile bids. Footnote 62 It was a second antitrust investigation into industry structure and practice, and the subsequent 1989 Beer Orders, that finally forced a separation of brewing and pub retail assets. Over the course of the next decade, all of the brewery operations of the former Big 6 were subsumed into the international brand owners Anheuser Busch InBev, Carlsberg, or Heineken. Footnote 63 For firms seeking to remain in pub retailing, trends were equally challenging for those with more traditional organizational cultures built around production supremacy, such as Allied Footnote 64 and Bass. Footnote 65 Whitbread, having already experimented and transitioned toward a more contemporary leisure-retailing approach, survives; all other pub assets were amalgamated into other operators, many of which emerged in the 1990s.

The long history of industrial organization and sociopolitical influence explains why the UK brewing industry has been featured prominently in empirical studies on regulatory economics; Footnote 66 UK social, economic, and business history; Footnote 67 brand marketing and internationalization; Footnote 68 as well as on the industry’s coevolution with the UK political system. Footnote 69 Post-World War II Whitbread, considered longitudinally and with its micro-foundation, offers additional insight on family firm organizations in the context of (1) the evolving sociopolitical system, (2) the role of the evolving market for corporate control and regulatory oversight, and (3) the institutional factors that influence implementation of long-term strategies.

Whitbread and the Whitbread Umbrella

Between 1799 and 1889, Whitbread was run in a cautious manner by a succession of partners from six families, of which three were prominent: the Whitbreads, Martineaus, and Godmans. Footnote 70 In 1920, three of the ten board directors were members of the Whitbread family, a number that remained unchanged until 1955. Of the remaining seven directors in 1920, the only one who was not a member of one of the families, and who remained throughout this thirty-five-year period, was the “redoubtable” Sir Sydney Nevile. Footnote 71

The first time Whitbread ordinary share capital was offered to the public was on July 5, 1948, five days after the Companies Act of 1948 gained Royal Assent. In addition to modernizing the preexisting ownership structure following the death of four family members, Footnote 72 the share offer was designed to secure the injection of much-needed capital. Footnote 73 However, approximately 30 percent of the “A” Ordinary Stock Units (one vote for every £1 stock) and 60 percent of the “B” Ordinary Stock Units (one vote for every 1s stock) remained in the beneficial ownership of the firm’s directors as a deliberate strategy to protect the firm’s independence in an evolving market for corporate control. Creating something of a precedent by issuing two classes of ordinary shares, a number of other companies in the brewing industry followed suit, notably fellow London brewer Fuller, Smith, and Turner, which still retains this structure. Footnote 74 Whitbread’s chairman at the time, Colonel W. H. Whitbread, struck a note in favor of the family ownership arrangement:

My earnest wish that the connection between my family and the Company may be maintained unbroken and that the very strong sense of tradition engendered by this long connection through generations may also continue hand in hand with the reputation for progressive management of the business. Footnote 75

The Companies Act of 1948 was legislation that enforced more substantial financial disclosure, and the traditional firms were aware of the pitfalls of a public listing. In July 1948, in proposing an increase in the firm’s share capital through the capitalization of a Special Reserve Account, Whitbread reflected a concern shared by other property-rich brewers:

[The g]reat disparity between the values of the Company’s properties taken as a whole (particularly the licenced houses) and the figures at which these assets appear in the Balance Sheet … might fail to give a true picture of the Company’s position. Footnote 76

This was a nervous era for a UK brewing industry that was laden with extensive and attractive property assets. In particular, the smaller family-controlled regionals were concerned that they would fall prey to unwelcome approaches from financial entrepreneurs. Footnote 77 By 1955, with an increasing incidence of the previously unheard of hostile takeover bid, several of the smaller brewers turned to Whitbread as the leading family brewer with its own protective share structure. Footnote 78 Whitbread obliged with equity investments, struck usually with formalized trading agreements for one or more of the firm’s beer brands. A relationship with Wadworth & Co. was typical: the smaller brewer agreed to bottle and offer for sale Whitbread’s stout beer, Mackeson, across its licensed estate as part of a twenty-one-year agreement, which had a six-month notice of termination. Footnote 79 In other cases, the relationship extended to an invitation for a Whitbread director to join the board of the smaller brewer, such as occurred with Oxfordshire-based brewer Morland & Co., to which Col. Whitbread joined the board. Footnote 80 Whitbread entered such agreements with some twenty smaller brewers, and the decision was made to consolidate them into a dedicated investment vehicle: the Whitbread Investment Company (WIC). WIC was established on March 8, 1956, under the terms of the Companies Act of 1948, and with Articles of Association stating an objective to undertake and carry on the business of an investment trust, with a wide-ranging brief to acquire stocks, shares, and bonds in any government or public or private company. Footnote 81

The relationship between Whitbread, WIC, and the Whitbread family formed a complex and bid-proof organizational structure known as the Whitbread Umbrella. The structure remained in place for nearly four decades, until it was dismantled subsequent to a second competition policy inquiry—the 1989 Beer Orders—that ended the large brewers’ control of the UK beer industry. Figure 1 illustrates the umbrella and shareholdings between Whitbread Plc and WIC. In addition to the large cross-shareholdings between Whitbread and WIC, the Whitbread family retained a number of A shares and approximately 20 percent of the B shares, with the remainder held by institutional investors.

Figure 1 The Whitbread Umbrella in 1993.

Source: Adapted from Shepherd, “Whitbread Sells Regional Stakes”; and Monopolies and Mergers Commission, The Supply of Beer.

Although WIC was listed as an independent entity on the UK stock market, it was clearly under the control of Whitbread. This was a “curiously incestuous relationship,” Footnote 82 with the chairman of Whitbread operating as a main board director of WIC, which, for all intents and purposes, was the banker in the umbrella structure. WIC accepted Whitbread A shares in lieu of payment so Whitbread could consolidate control of WIC’s regional brewing investments. It also purchased the high-voting B shares from Whitbread family members who wanted to sell some or all of their shareholding. Consequently, protection of the group was cemented through tight control of the B shares.

By the early 1970s, Whitbread had consolidated the majority of the original twenty regional brewery investments incorporated in WIC. Footnote 83 This gradual consolidation resulted in Whitbread becoming one of the Big 6 national brewer–retailers. This was achieved without needing to acquire investments or seek capital from the market; and it remained protected through its dual-voting share structure. Successive generations of managers looked favorably on the umbrella as integral not only to the Whitbread group, but also as a “powerful force for stability in the beer market.” Footnote 84 It is therefore conceivable that had the Beer Orders intervention not occurred, with its very specific complications for Whitbread, the umbrella might have remained in place for a longer period of time. By the 1990s, some UK institutional shareholders were becoming increasingly vocal in their criticism of complex shareholding arrangements, Footnote 85 although other UK firms resisted the pressure to enfranchise, notably the London brewer Fuller, Smith, and Turner, and the City of London investment firm Schroders.

How the Whitbread Umbrella Operated in Practice

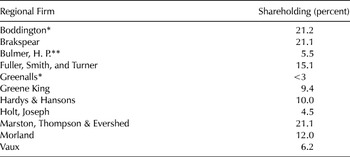

Whitbread’s position as a Big 6 national brewer–retailer was a function of the sequential absorption of the regional and family brewers who entered the umbrella during the 1950s and early 1960s. Starting with a tied estate of 808 pubs, of which only 4 percent were managed in 1948, Footnote 86 by 1967 Whitbread’s estate included 7,260 outlets, of which nearly 20 percent were managed. Footnote 87 The total size of the estate had shrunk to 6,483 pubs by the time of the second inquiry, although 29 percent were managed. Footnote 88 Table 1 shows the extent of the umbrella’s ownership of the regional brewing sector at the point it was dismantled in 1993. Prior to that, and as discussed above, many of the umbrella’s initial shareholdings and relationships had already been subsumed into the Whitbread group over the course of consolidation in the 1960s and 1970s.

Table 1 Whitbread Umbrella Investments, as of March 1994

Source: Shepherd, “Whitbread Sells Regional Stakes”; Monopolies and Mergers Commission, The Supply of Beer.

* Pub companies that were formerly brewers

** Cider producer

The decline in brewery firms, with many being subsumed into the enlarged portfolios of the Big 6 during the consolidations of the late 1950s and early 1960s, predated the increasing domination of lager over traditional ale producers (see Figure 2). The decline was also affected by growth in the take-home, or “off-trade,” sector. As lager increased in popularity, overall sales of beer in specialized off-license retailers and supermarkets grew from minimal levels to more than 20 percent by 1990. Footnote 89 Progressing to levels customary in most other developed markets, off-trade growth followed liberalization of licensing under the Licensing Acts of 1961 and 1964, as well as through social and economic changes, in particular the emergence of female drinkers (a demographic that generally shunned consumption in traditional public houses), and a rapid increase in the 15–24 age group. Footnote 90

Figure 2 UK brewing market, 1930 to 2010.

Source: British Beer & Pub Association Statistical Handbook, 2012.

On reflection, portfolios of large and well-sited pubs that could support a range of managed leisure-retail formats had the winning edge, particularly as casual dining and the café culture emerged in 1980s Britain. A successful pub had to be able to deliver a range of goods and services in an environment where regional identity and tradition was subordinate to a definitive retailing culture. Footnote 91 In contrast to the production orientation that continued to drive the retail strategies of Allied and Bass, Footnote 92 Whitbread recognized the need for structural change before the Big 6 consolidation era. Footnote 93 Whitbread demonstrated its openness to external ideas through its recruitment, training, and assimilation of outsiders who brought a genuine shift to a retailing orientation. The opportunity in retailing was also foreseen by financial entrepreneurs Charles Clore, of Sears Holdings, and Sir Maxwell Joseph, of Grand Metropolitan, whose paths crossed the brewing industry through their interest in fellow London brewer Watney Mann. Grand Metropolitan became a key mover in establishing a sound base for the 1980s pub–restaurant movement. Footnote 94

Whitbread’s post-World War II modernization was credited largely to the actions of Col. Whitbread following his promotion to the role of group chairman in 1944. Footnote 95 Whitbread had been a managing director of the group since 1927, and as the chairman he led both the offer for sale in 1948 and the formation of WIC in 1956. Yet, it is clear that his strategies were implemented with the assistance of a powerful accomplice: the “retired” managing director of the interwar period, Sir Sydney Nevile. Nevile had been Whitbread’s mentor and predecessor in the drive to make the UK brewing industry more socially acceptable. This was necessary because of the temperance movement, which had threatened to restrict, if not destroy, the brewing industry in the years before World War I. Footnote 96 As Mutch has argued, Nevile was uniquely placed as part of the “downwardly mobile gentry” to bridge the gap between the aristocratic partners of the family-controlled brewing sector and their patrons. Footnote 97 Nevile was one of the first external recruits into a traditional industry struggling to balance the need for professional management with the need to maintain family control. Footnote 98

Nevile was central to the high-level affairs of Whitbread for fifteen years after his supposed retirement from the firm. Although notionally retiring as Whitbread’s managing director on December 31, 1948, he remained a director under a renewable “services agreement,” a role that gave him a floating investment banking/deal-making brief. Footnote 99 He fulfilled his role as director while retaining his wider industry status as a senior vice president and life member of the Institute of Brewing. Footnote 100

The esteem with which the small family brewing sector of the time viewed Whitbread and Nevile is apparent from the tone of correspondence, sent to Nevile at his home: “Yes, I am sure our companies are going to get on very well together and we are looking forward to improving our efficiency and products through the ‘know-how’ of Whitbreads.” Footnote 101

This was an era when close personal relationships and affiliations were important in UK corporate life, extending to the very heart of the political and banking establishment. Footnote 102 The brewing industry, whose family firms, as noted above, were known affectionately as The Beerage, displayed what a later generation of corporate raiders described as an overly “cosy” culture that restrained performance. Footnote 103 An amateur style that characterized the industry since the second half of the nineteenth century was cast as traditionalist, paternalistic, inbred, and secretive. Footnote 104

The relationships among prominent brewers and the upper echelons of the British Army, The City of London, and Parliament were embedded in the history of Whitbread. Footnote 105 This was true as well for the other Big 6 brewers and their earlier incarnations Footnote 106 (and the similarly patriarchal City, whose influential merchant banking advisers were also family controlled). Footnote 107 Family influence remained a strong feature of the industry in the immediate post-World War II period. Footnote 108 Although Whitbread had a more established strategy of promoting outsiders, it was, nevertheless, very careful to ensure its managers fit with the company’s particular style. If Nevile charted an unorthodox course to the top, Footnote 109 Sir Charles Tidbury was more typical of the era, if not the firm: he attended Eton, followed by 60th Rifles, the Royal Green Jackets, and the “pure nepotism” of a wife whose aunt was married to Col. Whitbread. Footnote 110

Yet, despite the apparent coziness, the actions of Whitbread might best be described as strategic behavior. Footnote 111 In the months after WIC was established in 1956, Nevile received a “Highly Confidential” letter from the legal representative of a small family firm inquiring as to whether Whitbread might be interested in buying the firm. Footnote 112 Nevile’s file note to then–Managing Director Charles Tidbury displays a somewhat harder, or less cozy, edge:

I think we need from Winter the list of houses by Mackays with their addresses and trades. We should then have the houses inspected from the outside and some of them visited as ordinary customers inside avoiding as far as possible any idea of Whitbread’s interest. Footnote 113

That Whitbread might have operated with strategic intent is encapsulated in a poster campaign of the era by the consumer group the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) as part of its lobbying ahead of the 1989 competition policy inquiry. Referring to the umbrella, and documenting the subsequent closure of ale breweries and pubs when Whitbread consolidated control, CAMRA described the umbrella as “a fine idea in principle, but as the murdered diplomat Gregory [sic] Markov discovered, an Umbrella can be a pretty nasty weapon in the wrong hands.” Footnote 114

Referring to the assassination of Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov in a London street in 1978, CAMRA conjured an image of subterfuge and a Whitbread motivated by self-interest rather than those of the smaller brewers that had turned to it for help. It categorized WIC as the agent of takeover manipulation. While it is certainly true that there was a transfer of assets within the umbrella, this tended to occur subsequent to a request for help. This was the case, for example, when Boddingtons—a beer brand that under direct Whitbread control found a new lease on life in the 1990s Footnote 115 —feared it would be subsumed into Allied Breweries. Footnote 116 However, institutional investors, not Whitbread, made the ultimate decision on ownership. Whitbread was responding as much to market forces as to the strategies of its larger would-be national competitors, Allied, Bass, and Scottish & Newcastle. Rather than replicate their strategy for national coverage, played out largely through brewing efficiency, the military-trained managers of Whitbread likened their approach to the more nimble tactics of the Green Jackets. Footnote 117

By the early 1960s, the impact of financial entrepreneurship and the attraction of the property assets of the UK brewing industry were already evident in the hostile approach of Charles Clore’s Sears Holdings for London-based Watney Mann. Whitbread sought to promote and encourage a longer-term view on industry structure and organization, with Nevile stating in correspondence:

I cannot help but feel the concentration of so many family businesses into large concerns in which the public interest is subordinated to immediate profit making and profit taking not only robs business of much of its pleasure, but in the long run militates against the continuous security and prosperity. Footnote 118

The disapproval of the finance-motivated consolidation that led to the emergence of the Big 6 was apparent in discussions with leading financiers, who, as well as fellow brewers, Nevile sought to influence. In a file note recording a meeting with a senior financier he wrote: “In conversation he [Mr. Dudley Robinson] referred to the present fever of finance in the brewing industry, and I mentioned Whitbread’s policy to associate ourselves with other companies and keep them alive rather than completely absorbing them.” Footnote 119 In a letter to the chairman of a small brewer a month later he commented:

“I deplore the present concentration of the brewing industry, and the consequent loss of personality and goodwill between the individual brewer, with his sense of citizenship, and the public. … [I]t is Whitbread’s policy to co-operate with moderate sized businesses so that their individuality may not be lost. Footnote 120

There is, therefore, little evidence to support CAMRA’s view that the smaller firms were unwilling partners, or that Whitbread was a particularly unscrupulous asset-stripper. Footnote 121 Some relationships continued in an arms-length trading relationship over several decades, with minority equity participation through the umbrella. This is illustrated by the relationship between Whitbread and Henley-based brewer Brakspear. The relationship was precipitated by an unwelcomed approach to Brakspear from a property speculator in 1962. The Brakspear family contacted Whitbread, which bought enough shares to thwart the aggressor. In return, Brakspear offered Whitbread a board seat and a supply agreement for Whitbread’s Mackeson stout beer in Brakspear’s 124 pubs. Although Whitbread sought to acquire Brakspear in 1973, Brakspear declined the offer, as well as bids from Truman, a subsidiary of Grand Metropolitan, and neighboring brewer Morland. Footnote 122 The relationship between Whitbread and Brakspear continued on an arms-length basis for more than twenty years.

The association between Whitbread and the regional brewery sector was prised apart as a result of regulatory policy intervention to curtail the UK brewing industry’s vertical tie. It was deemed that the Big 6 brewers were engaged in monopolizing practices that acted against the public interest. This could only be mitigated through a forced reduction in the size of their pub estates and the granting of a “guest beer” provision to support the smaller brewers. Footnote 123 Whitbread’s unique structure brought specific and additional complications. Whitbread and WIC were deemed to represent a “brewery group,” meaning that, if WIC owned more than 15 percent of the voting shares of any other brewer, that brewer’s pubs were amalgamated with Whitbread’s for the purposes of the Tied Estate Order (one of the two statutory elements of the 1989 Beer Orders that restricted the number of public houses that the Big 6 brewers were able to own or control after November 1992). Consequently, a decision had to be made ahead of the November 1992 compliance deadline regarding equity ownership in several regional brewers as an alternative to Whitbread selling or untying pubs from its directly controlled pub estate.

Notwithstanding the impending legislation, reduction in ownership came naturally as a result of inter-regional consolidation. Greene King’s hostile bid for Morland in the summer of 1992 was significant for the umbrella in more than one way, including causing WIC to become mired in a tense battle between two core investments. Morland was one of the longest standing in the umbrella, with Col. Whitbread joining the board of directors in the late 1950s. Greene King approached WIC directly to acquire its stake as the platform for a hostile approach at a time when WIC had little choice but to offload the larger proportion of its 43.4 percent shareholding of Morland. Footnote 124 After this experience, and to avoid further piecemeal divestment and potentially failed bids, Whitbread chose to restructure the umbrella. In November 1993, it acquired the 50 percent of WIC that it did not own for £234m and simultaneously collapsed the dual-voting share structure. Footnote 125 Then, in March 1994, Whitbread sold the portfolio of regional brewers (see Table 1) for approximately £230m. Footnote 126

The process of structural change corresponded with the appointment of a new chairman, industrialist Sir Michael Angus, who previously was the chairman of Unilever. Footnote 127 Although Angus had been a non-executive director of Whitbread for five years, he showed himself to be responsive to the growing criticism from UK institutional investors of dual-voting share structures, and sought to establish that Whitbread was now “different” from the firm of 1948. Footnote 128 Of course, having already witnessed substantial change in the ownership and structure of the UK brewing industry in the aftermath of the Beer Orders, with Grand Metropolitan and Allied Domecq merging their UK brewing operations, with Elders (Courage) and Carlsberg, respectively, Footnote 129 the dual-voting share structure that had served Whitbread well as a protection from the capital market was now seen as a barrier to it taking part in future consolidation that would undoubtedly require access to equity capital.

The Whitbread Umbrella and Whitbread’s Performance

Whitbread’s structure and the way the umbrella operated was often criticized for deterring the creation of an efficient national brewing operation, in contrast to the rationalization benefits the other Big 6 brewers achieved through the mergers of the early 1960s. From 1961 to 1971, Whitbread acquired twenty-three brewing companies across the country, although most were left intact in accordance with promises made on merger. This left much to do in the 1970s to rationalize production. Footnote 130 Between 1966 and 1985, Whitbread’s output per brewery rose from 0.194 to 0.503 million barrels, bringing the firm to within a whisker of the output statistics for Allied Breweries, Bass, and Watney Mann. However, it remained far short of Courage, Guinness, and Scottish & Newcastle, all of which operated fewer breweries. Footnote 131 Whitbread was sensitive to its apparent poor operating performance relative to its competitors, as is evident in its comments to the 1979 Price Commission investigation into its beer pricing strategy, Footnote 132 where it noted that its return on capital employed remained below management expectations. Footnote 133

In 1969, during the first competition inquiry into the operation of the UK beer market, the Big 6 national brewer–retailers provided confidential information on their financial performance. They gave details of sales, costs, profits, and capital employed relating to the sale of beer in licensed premises. Footnote 134 In defense of the centuries-old vertical tie, the Brewers’ Society, the industry’s trade association, cautioned about the artificial apportionment of profit and returns of one activity relative to another within the vertically integrated structure. Footnote 135 In the second competition inquiry of 1989, Whitbread presented evidence showing a wide variation in open market rental returns for pubs as a function of their specific location, quality, and whether they were located in a city. Footnote 136 By this stage, the firm had embarked on a heavy capital investment program designed to upgrade the pub estate to larger managed houses, with an increased focus on food and other leisure activities that was cast as a “substantial change of course.” Footnote 137 The shift to a managed house retail focus was already occurring in Whitbread.

Starting in the 1950s, the relative attraction of the property portfolios of brewers with prime city center assets underpinned interest from financial entrepreneurs and motivated the possibility of unlocking capital from the changing shape of retailing. This was particularly significant in the south of England, and especially in London. Watney Mann, for example, had been considering alternative proposals, including the sale of a long lease for its central London brewery, months before Charles Clore made a hostile approach in 1959. Footnote 138 What Clore spotted, as indeed did successive generations of financial entrepreneurs, was that the aggregate valuation of the pub estate masked assets that were large enough to be converted into more modern, and consequently higher-value pubs; or, in the alternative, could be converted into shops or other types of cash-generating assets, including residential property. Footnote 139

Whitbread’s weak position as a national brewer continued beyond the 1980s (see Table 2). However, this was increasingly subordinate to its managed retail performance, as well as the potential opportunity presented by the Beer Orders legislation. Bass and Allied continued to struggle with the legacy of pub estates (which were both culturally and operationally anchored to the production-led focus of the past Footnote 140 ), notwithstanding the far-reaching reviews of retail strategies that took place in both firms. Footnote 141 As is clear now, none of the Big 6 brewers were able to embed a powerful base in the United Kingdom in the 1990s. Without this, they could not survive and prosper in the internationally consolidating brewing industry of the 2000s. Footnote 142 Whitbread forged an alternative path that can be traced to the changing attitude that began in Col. Whitbread’s era: a focus on managed retail and the development and expansion of concepts such as Beefeater (steak restaurants) and Travel Inn (budget hotels). This path was pursued even with considerable criticism from the UK stock market. Footnote 143

Table 2 Operating performance of major brewers in 1999

Source: All calculations have been made from data sourced from firm official documents as detailed below. The documents were downloaded from the firms’ websites in the period 2002–2006 for a related statistical study.

Allied Domecq: UK Annual Report and Accounts for the years ended August 31, 1996, 1998, and 1999. Brewing operating margin is for 1996, which is the last year of Allied Domecq’s part-ownership of the Carlsberg-Tetley joint venture. Pub Retailing operating margin is adjusted to remove Victoria Wine off-license subsidiary.

Bass: US Securities and Exchange Commission Form 20-F Annual Report for fiscal year ended September 30, 1999.

Scottish & Newcastle: UK Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended April 30, 2000.

Whitbread: UK Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended February 27, 1999. Pub Retailing incorporates the separately disclosed Whitbread Inns (managed pubs) and Pub Partnerships (tenanted pubs) but excludes Restaurants and Off-Licenses.

By the time Angus became Whitbread’s chairman in 1992, the firm was heading firmly in the direction of leisure retailing, under Chief Executive Officer Peter Jarvis. His successor, David Thomas, was also intent on breaking with the past. Thomas, who joined Whitbread in 1984, had been responsible for the firm’s restaurants and leisure-related activities. Footnote 144 Although responsible for the 1995 acquisition of Costa Coffee, he is, unfortunately, more readily associated with the proposed acquisition of Allied Domecq’s (the former Allied-Lyons) retail operations in 1999. Footnote 145 The failure to complete this major acquisition, which had underpinned the decision to collapse the post-World War II protective shareholding structure, prompted the major strategic review from which today’s Whitbread owes its continued existence. Footnote 146

Whitbread is a rare example of a firm that has undergone a major and successful strategic transformation, emerging from a long history as a London-based vertically integrated brewer to become one of Europe’s leading leisure operators. It is of particular interest to business history because, of the Big 6 national brewer–retailers that dominated the UK brewing industry in the 1960s to 1980s period, it is the only one to survive independently in the public domain.

Conclusions

This article highlights the role of the institutional environment in the evolution of Whitbread in the post-World War II era. Central in the narrative is a unique organizational structure, the Whitbread Umbrella, and how it supported both Whitbread and the wider family brewing sector, which was under attack from financial entrepreneurship. A fundamental question is: Can Whitbread’s transformation be attributable to the protective organizational structure that was in place from 1948 to 1993? Although much happened subsequent to the unwinding of the umbrella, most notably the failed attempt to acquire Allied Domecq’s pub estate in 1999, a cursory glance at today’s share price offers support for the strategy of the 1980s that promoted retail over brewing, which, in its infancy, was unconstrained by short-termism and the market for corporate control (given the protection of the dual-voting shareholding structure and complex arrangement with WIC).

Post-World War II, traditional UK ale brewing was in decline. The pub, as a newly defined leisure outlet, with its wider social appeal, may have been under consideration by Whitbread, although it was not immediately apparent that the firm contemplated anything other than a brewing-based future. Under the guidance of Col. W. H. Whitbread and Sir Sydney Nevile, Whitbread exemplified many of the attributes underpinning Stewardship Theory, Footnote 147 exploiting organizational social capital at the center of a family network of like-minded, if smaller, brewing firms. Footnote 148 While there is some evidence of strategic behavior in contemporaneous notes and letters, many of the trading relationships and investments in the smaller family brewing sector led naturally to a marriage with Whitbread. There was inevitability in this absorption, given the structural shift to lager consumption and the take-home trade, the economics of which favored scale in brewing that the family brewers were unable to provide. Footnote 149 Whitbread consequently incorporated and consolidated its position on a smaller and gradual basis, without needing access to the capital market. At the same time, it was protected from the capital market because of the Whitbread Umbrella and its dual-voting shareholding structure.

An active discussion concerning the efficacy of complex share ownership arrangements, and the position of family firms and their strategic development, continues to challenge academic debate in finance, economics, and the general management literature. The timeframe against which strategies are developed and evaluated aligns naturally to the debate concerning optimal ownership structure and the Agency Theory. Footnote 150 In practitioner circles, attention has been drawn to the adverse consequences of shareholder activism that follows high-profile decisions, such as reengineering structures similar to the Whitbread Umbrella: Google’s decision to issue a special class of untraded shares, Footnote 151 France’s legislation to double the voting rights of shares held in public firms for more than two years, Footnote 152 and Hong Kong’s unexpected neutrality on whether its stock exchange should allow dual-class shares. Footnote 153 Policymakers will draw comfort from U.S. analysis that shows that privately held firms, free to take a longer-term approach, invest at more than twice the rate of their listed contemporaries. Footnote 154 Researching firms such as Whitbread, which have survived and ultimately prospered through a long period of socioeconomic and political change, informs both academic and practitioner debates, pointing to a positive role for protective ownership structures in assisting the implementation of long-term strategy development.