Introduction

Since the mid-twentieth century, the footwear industry has been a significant economic activity in southern Europe. Although its importance has declined significantly in recent decades, both in terms of employment and contribution to gross domestic product, the sector continues to have a considerable size in Italy, Spain, and Portugal, and these three countries maintain a very high share in the world footwear trade. The development of the sector, absolutely dependent on foreign markets, shows many common features in the three countries. However, if the analysis is deepened, it can be seen that in each of them the process had a different chronology and some peculiar characteristics. These differences caused the competition of footwear coming from Asia and other areas with very low labor costs, which would increase continuously since the early 1970s, to not have the same impact on all three countries. Nor were the responses to the crisis identical, which also contributed decisively to the fact that each country's industry has different levels of resilience. This paper comparatively analyzes the trajectory followed by the footwear industry of Italy, Spain, and Portugal between 1970 and 2007, paying special attention to the strategy followed by companies to deal with international competition. The study sets its time limit just before the beginning of the Great Recession, as we still lack sufficient historical perspective to properly assess this last depressive juncture.

Economic history has traditionally placed crisis and recovery processes among its main research topics. In recent decades, this interest has become widespread in the social sciences, which have adopted the term resilience from other scientific disciplines to name these processes. In a broad sense, resilience is the ability to react and recover from an adverse shock,Footnote 1 but there are different interpretations of the precise meaning of the term. We can find at least three different conceptions of resilience: the engineering, the ecological, and the evolutionary conceptions. The engineering resilience focuses on the ability of a system to resist external shocks and recover its previous state. The ecological conception emphasizes how external impacts push a system beyond its “elasticity threshold” to a new stable configuration or path. The evolutionary conception focuses on the ability of the system to reorganize and adapt to changes, in a dynamic process of continuous renewal.Footnote 2 Although most empirical studies on economic resilience have adopted a territorial approach, focusing on regional or local economies, several works have demonstrated the usefulness of also analyzing the ability of industrial sectors to cope with crises.Footnote 3 These studies indicate that resilience depends not only on the territory's economic assets and weaknesses and the performance of public authorities, but also on the strategy followed by companies. For example, with a business history approach, Valdaliso has highlighted the importance of the “high levels of learning and of absorptive capacities” of machine tool companies to explain the resilience of this industry in Spain between 1960 and 2015.Footnote 4

This paper applies the evolutionary conception of resilience to the footwear industry, analyzing how the southern European production has been adapting to the erosion of its competitive position in the world market, what strategies it has followed, and what factors have been most decisive in this process. Comparing the evolution of the sector in the three main footwear producing countries of southern Europe over a long period, crossed by several major crises, allows us to assess which strategies and characteristics of the industry have had a more positive effect on adaptation to disturbances and therefore have contributed to increased resilience.Footnote 5 Footwear companies did not consciously adopt a common resilience strategy. However, the measures taken by companies to face the challenges in the international market did have a decisive effect on the adaptation of the sector to these challenges and, consequently, on the sector's greater or lesser resilience in each country.

Export figures have been used to determine the main periods of crisis suffered by the footwear industry in the three countries analyzed. The concept of crisis has been widely used by history, economics, and the rest of the social sciences, but not always with the same meaning.Footnote 6 In economics, crisis is considered to be the turning point that separates the ascending phase of the business cycle from the descending phase, but very frequently the term is used to describe the entire descending phase of the cycle, that is, as a synonym for recession or depression. The theoretical analysis of economic crises has been carried out from very different approaches, ranging from Marxism to business-cycle analysis. Whereas the "orthodox" approach interpreted fluctuations as the result of external forces that temporarily altered the equilibrium toward which the economic system tended, for authors such as Schumpeter and Keynes or, more recently, Minsky and Kindleberger, crises would be a consequence of the unstable nature of capitalism.

The periods of economic crisis are usually determined mainly by looking at the evolution of production or, with a broader perspective, also taking into account employment, real income, and real wholesale and retail sales. When considering a specific industrial sector, the variables used to establish the chronology of the crises are mainly production and employment, but other indicators are also used, such as number of companies, market shares, and exports.Footnote 7 We have used export value data as the main indicator because the footwear industry in southern Europe is mainly export oriented, allocating more than 90 percent of its production to the foreign market. These data are more reliable than production or employment data, because they have better statistical control and are less affected by the phenomenon of the underground economy, which has traditionally had a strong presence in this industry. On the other hand, it is preferable to use the export value, instead of the quantity, because footwear is not a homogeneous product, but there are large differences in quality and price within this product category.

After this introduction, the paper examines the characteristics of the development of the footwear industry in southern Europe since the mid-twentieth century. The following section identifies the main periods of crisis suffered by the sector in Italy, Spain, and Portugal, and deepens its causes. Next, we study how the industry responded to the crises in each country: Section four reviews the measures adopted to reduce costs and maintain price competitiveness, whereas section five analyzes the measures to differentiate the product. We have tried to assess the effectiveness of both types of strategies in each country using the method of local projections. Finally, some conclusions are offered on the differences in the responses to the crisis and their impact on the resilience of the industry in each of the three countries.

The Footwear Industry in Southern Europe

Although this is a traditional industry in an advanced stage of its life cycle, with a high degree of unskilled labor, which has experienced a marked shift toward Southeast Asia since the last decades of the twentieth century, the footwear industry has continued to be a relevant activity in Europe. European countries maintain a very prominent role in the world trade of this product in the first decades of the twenty-first century. In 2012 there were 21,000 footwear manufacturing companies in the European Union employing around 280,000 workers, with 24,000 million euros of invoicing and an added value of 6,200 million euros, around 0.5 percent of the added value from the European manufacturing industry as a whole.Footnote 8

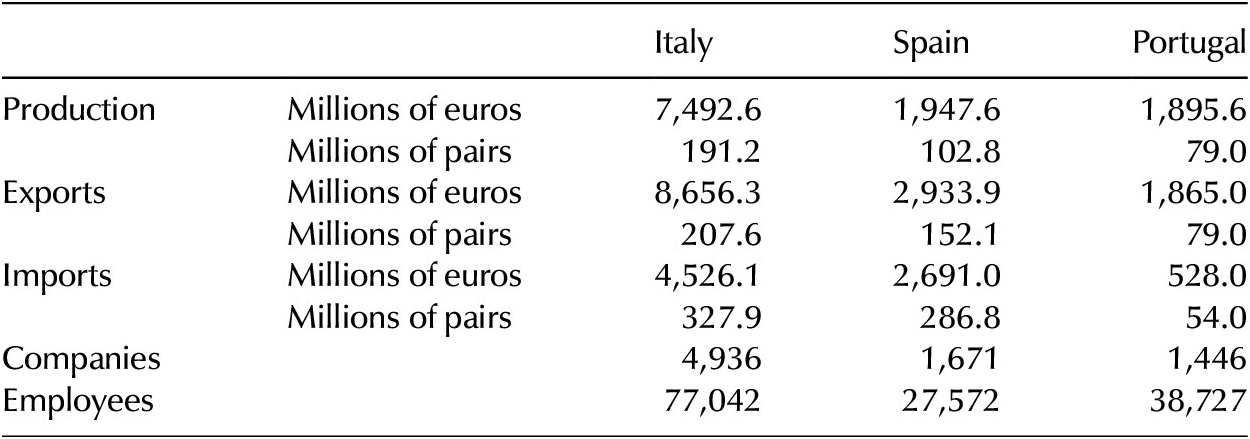

The European footwear production is mostly concentrated in three southern countries (Table 1), Italy, Spain, and Portugal, which account for almost three-quarters of the output. In the three countries the industry is mainly aimed at the foreign market, essentially toward the other countries of the European Union, to which over 80 percent of exports are destined. Particularly noteworthy is Italy, which in 2015 was still the world's third largest footwear exporter, only behind China and Vietnam, with the highest average price per exported pair out of all the major footwear exporters.

Table 1. Basic characteristics of the footwear industry in Italy, Spain, and Portugal in 2015

Sources: Assocalzaturifici, FICE and APPICAPS.

The footwear industry had a rapid development in southern Europe since the mid-twentieth century, thanks to external demand. The international footwear trade began to grow rapidly during the 1950s and expanded greatly since the 1960s. This growth was boosted by the United States and the European countries with higher income levels, which then became the major consumers of imported footwear and experienced drastic reductions in the number of businesses and workers in their own footwear industries.

France, and particularly Italy, took maximum advantage of the opportunity that the evolution of the international market gave to their footwear industries and dominated leather footwear exports with very little competition until the middle of the 1960s. French footwear exports increased at an average annual rate of 25 percent between 1950 and 1960.Footnote 9 The growth rate slowed down in the 1960s, while imports increased, but until the middle of the following decade France held its position among the top three world exporters of footwear. The Italian industry, which began with a much lower level of exports, increased its international sales even quicker, at an average annual rate of above 60 percent in the decade of the 1950s and became the world leader in footwear exports since the beginning of the 1960s, specializing in a medium-high product range, mainly ladies’ footwear. The penetration of Italian footwear in the international markets had the backup of the intensive international promotion of Italian fashion from the 1950s onward.Footnote 10 This promotion, the competitive price, and the attractive design allowed Italian footwear to conquer both the European and the U.S. markets in the 1960s.

The development of the sector was centered in the industrial areas specializing in footwear, which had been establishing themselves in Italy since the end of the nineteenth century, but the relative weight of each of them was gradually changing. In 1971 Tuscany was already the region with the largest number of workers in the sector; Lombardy, which had been the main shoemaker concentration until the previous decade, still occupied the second position, but was closely followed by the Marches and the Veneto. Three decades later, the districts situated in Le Marche and the Veneto had become the principal manufacturing centers, together accounting for half the value of Italian footwear production. Tuscany, with its industry around Florence, Pisa, and Pistoia, occupies third place with almost 20 percent of production, and Lombardy had gone down to fourth place, with a little over 10 percent.Footnote 11

Spanish exportation took off in the second half of the 1960s, following the progressive liberalization of the country’s foreign trade, state backup through grants and credits for exports, and a drastic devaluation of the peseta. Footwear exports grew at an average annual rate close to 70 percent between 1966 and 1971, the last year resulting in around 60 million pairs and making footwear the principal product of Spanish industry from the value of its exports. This expansion came about in direct competition with the Italian footwear, mainly in the American market. The United States absorbed almost three-quarters of foreign sales in the second half of the 1960s and therefore was the market which was most decisive in the takeoff of exports for this industry. However, the fact that Spain was not part of the European Economic Community meant that its exports within this area were very reduced, this situation not changing until 1970 when Spain signed a preferential trade agreement with the EEC.Footnote 12 The competitiveness of Spanish footwear essentially lay in its price which, comparing similar quality levels, made it considerably lower than the prices of its European competitors. This price advantage was the result of lower labor costs in an intensive manufacturing sector in which labor represented nearly 40 percent of the production costs.

As in Italy, the development of the sector was also located in the industrial districts established in earlier decades. The industry was mainly concentrated in the province of Alicante, whose contribution to Spanish footwear production as a whole increased until it accounted for over half the total output at the beginning of the 1970s, when it was also supplying 60 percent of exports. The other large-scale production was on the islands of Mallorca and Menorca, which in 1970 accounted for 17 percent of Spanish footwear production, although in these locations the development of the sector was soon slowed down due to the rapid expansion of the tourism sector, which offered more attractive investment opportunities and raised the cost of labor.Footnote 13

Portugal also based the expansion of its footwear industry on the existence of a traditional manufacturing structure and very low salary levels,Footnote 14 far less than those of Italy and Spain. However, Portuguese industry did not start exporting until later, in the second half of the 1970s, and did not reach any considerable level until the second half of the 1980s. The link to foreign markets, driven by the commercial agreement with the EEC of 1972 and reinforced by the country's entry into this economic space in 1986, boosted the growth of the sector and its progressive modernization.Footnote 15 In 1973, footwear contributed 1.2 percent of the value of Portuguese exports, but in 1985 it already represented more than 5.3 percent, and in 1994 it approached 10 percent.Footnote 16 Between 1974 and 1984, exports rose from 5 to 31 million pairs, and in 1994 were in excess of 89 million. The expansion of exports was directed by multinational companies in other countries, principally Germany, attracted to Portugal by the low salaries, the proximity to its markets, and the entry of Portugal into the single European market. Exports were mainly directed toward the markets of central and northern Europe, with the Federal Republic of Germany, France, and the United Kingdom as the principal target markets.Footnote 17

The growth of the Portuguese industry was concentrated in the north of the country, mainly in two areas: the Aveiro district, around the cities of Sao Joao da Madeira, Santa Maria da Feira, and Oliveira de Azeméis, with a productive structure characterized by small businesses; and the district around Felgueiras and Guimarães, characterized by medium-sized companies and where large foreign companies were located.Footnote 18

Therefore, the footwear industry shows many similar characteristics in the three countries in the last four decades, among which stand out the strong orientation toward the foreign market and the high concentration of the sector in a few specialized industrial districts. Notwithstanding these similarities, important differences can also be seen in the comparison, mainly in the structure of the industry, the type of product, and the existence of intangible assets. Undoubtedly, these differences have influenced the evolution of the sector in each of the countries. A significant difference is found in the size of the companies: In Italy and Spain, the sector is mainly made up of very small companies, while in Portugal, although small and medium enterprises also predominate, the proportion of medium and large companies is considerably higher, particularly until the end of the twentieth century. The type of product exported is also different: Portugal and especially Italy have had much higher average export prices than Spain since the 1990s, which indicates that they are specialized in a higher quality type of footwear. In addition, Italy has a powerful country brand, which provides footwear with a very positive country of origin effect, far superior to that of the labels “made in Spain” and “made in Portugal.” The greater prestige of Italian footwear is reinforced by the existence of very influential Italian brands with a long presence in the international footwear market.

Crises in the Footwear Industry

The takeoff of Portuguese footwear exports served to increase competition and reduce the demand for the Italian and Spanish industries, but since the middle of the 1970s, the predominance of the European Mediterranean countries in the international footwear trade had been rapidly eroding due to the development of this industry in Asia and, on a smaller scale, in Latin America. The participation of the Far East in the value of the international leather footwear trade, which in the mid-1970s still represented less than 5 percent of the total, by the year 2000 had risen to above 39 percent. In a first stage, up until 1990, the expansion of Asian footwear exports was mainly led by Taiwan and South Korea, and sports shoes were the absolute majority of their output. From then on, however, the footwear manufacture and exports of both countries went steadily down, and it was China who relaunched the penetration of the Asian countries with footwear of all kinds. In 2000, China had already become the top world exporter of leather footwear, with almost a third of the total. Also, from the 1990s onward, Vietnamese footwear exports began to take off and, to a lesser extent, that of India, Thailand, and Indonesia. The growth of South American exports was much slower and mainly featured Brazil, which since the mid-1970s was positioned among the top world exporters.Footnote 19 Since the mid-1990s, some of the Eastern European countries, such as Romania, have also become prominent footwear exporters, taking advantage of the low salaries and their proximity to the markets of western Europe.Footnote 20

The difference in labor costs between Italy and Spain on the one hand, and those of the recently industrialized countries on the other, is so great that, since the end of the 1970s, the footwear industry of the European Mediterranean area has been in constant decline. The problem was transferred to the Portuguese industry at the end of the 1990s. The difficulties and the reduction of the sector have been intensifying while the European Union market opens up toward imports coming from outside. Between 1974 and 2014, the footwear industries in Italy and Spain saw the number of workers decrease by more than 40 percent, while their relative share of world footwear exports was reduced by almost 70 percent. In Portugal, the number of workers in 2014 had fallen by more than a third compared to 1994, and its share of global exports for the sector was little over half.

Given that, in the three countries, the industry is essentially export orientated, we can use the export data to determine the main periods of recession in the sector. By adopting a similar approach to that used by Catalan and Sánchez in their analysis of industrial crises in Spain,Footnote 21 the periods of crisis would be those in which the actual export value was less than the maximum achieved previously. However, in order not to attribute the crisis character to the short-term export fluctuations, it has been established as minimum requirements to obtain the crisis consideration that the decline in export figures has a duration of more than one year and that it is below the average of the three years prior to the start of the export decline. The recovery would be completed when that average value of the three years prior to the crisis was reached or exceeded.

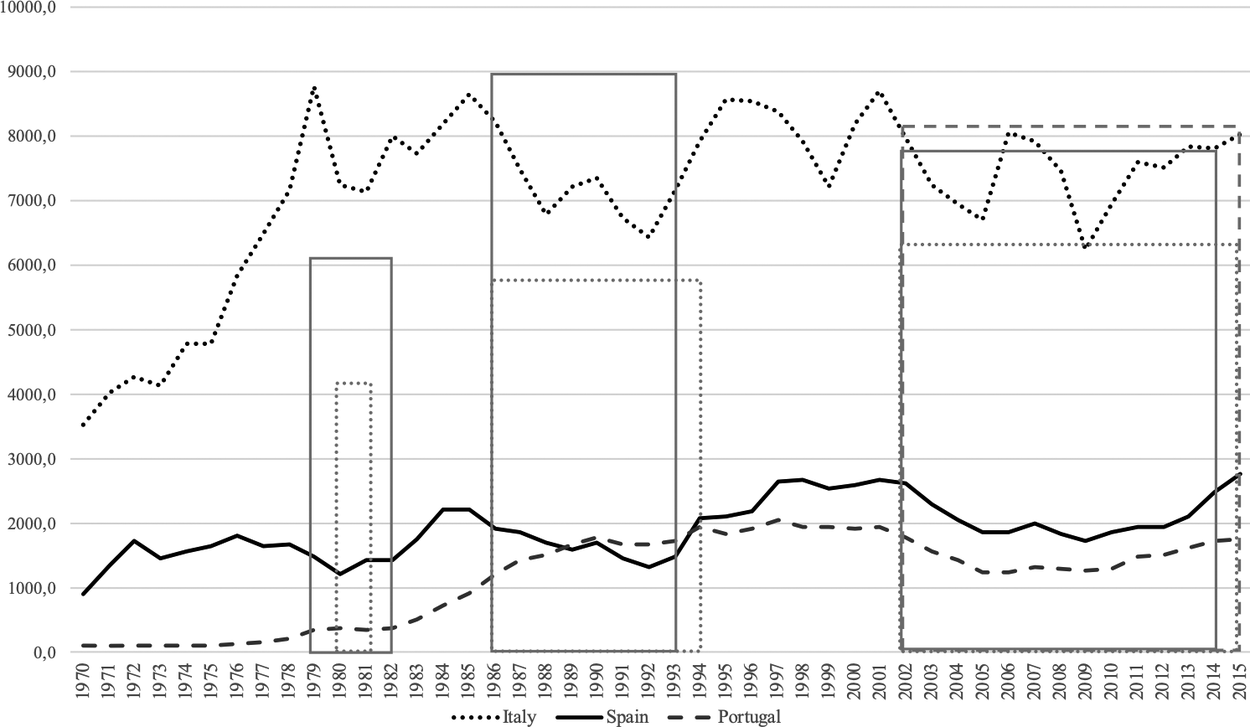

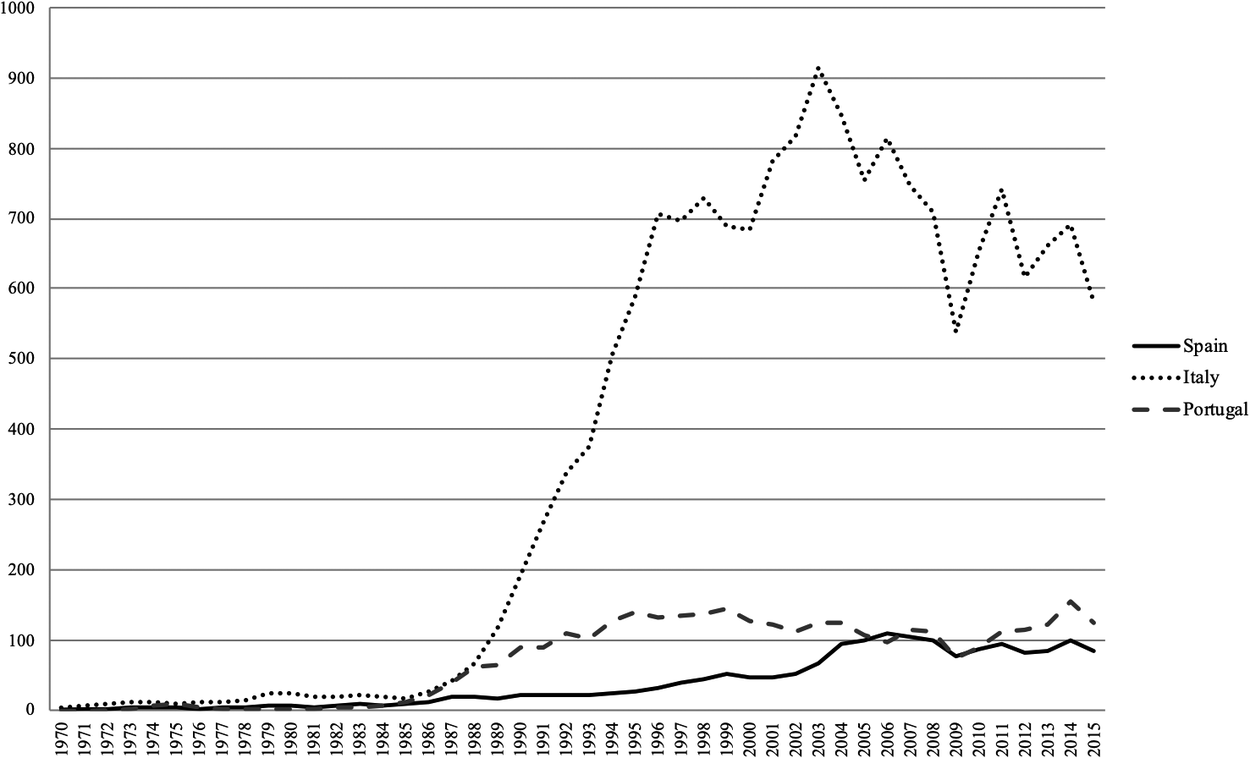

Following this criterion, in the footwear industry of Italy and Spain, three periods of serious recession can be observed: in the early 1980s, in the second half of the 1980s and in the early 1990s, and in the first decade of the twenty-first century. In Portugal, on the other hand, there would only have been a severe crisis in the last of the periods mentioned, starting in 2002, although the setback would then have been more intense and prolonged than in Italy and Spain. Figure 1 depicts these periods of crisis by means of rectangles, whose base is adjusted to the number of years of duration of the crisis and whose height is proportional to the maximum setback experienced in the export value.

Figure 1. Footwear exports from Italy, Spain, and Portugal, 1970–2015 (million of 2010 euros). Main periods of crisis.

In Italy, the crisis of the early 1980s caused a 19 percent drop in exports and was very short, only two years (1980–1981), but the real value of the export reached in 1979 would not recover in the next four decades. The partial recovery achieved in 1982 was interrupted by a new crisis in 1986, which would last for nine years, until 1994, and would cause a maximum decrease in exports of 26 percent. Exports would fall back again between 1996 and 1999 (when they fell by 16 percent), but the new important fall would take place from 2002 to 2005 (23 percent), and after a brief and rapid growth in 2006, exports would go down again between 2007 and 2009.

In Spain, the most intense crisis was in the period 1986–1993 (eight years in which the real value of exports fell by almost 40 percent). In 1979–1982 there had been a shorter and less profound recession (with a 28 percent decrease in exports), and exports had also experienced a sharp decline in 1973, although without being below the average of the previous triennium. The decline at the beginning of the twenty-first century was especially felt between 2002 and 2005 (with a fall of almost 34 percent), but actually the complete recovery of this long crisis would not come until 2015.

In the Portuguese footwear industry, there was no real recession until the beginning of the twenty-first century, although there were brief export setbacks in the mid-1970s, early 1980s, and at various times in the 1990s. The crisis initiated in 2002 would lead to a minimum in the real value of the export in 2006 (37 percent lower than the export of 2001), but the international economic crisis would sink exports again since 2008.

The severe economic recession at the end of the 1970s and early 1980s, closely linked to the increase in oil prices, brought about an important decrease in footwear exports as a whole for southern Europe, but its impact was different in each country, especially as regards the repercussions on the productive structure. Exports fell, first, because of the drop in demand, which meant that the actual value of global footwear exports as a whole went down, according to UN Comtrade data, by 20 percent between 1979 and 1983.

The fall of exports in Italy and Spain was greater than the decrease of global exports, to the extent that in 1982 both countries had shares of the world market lower than those of 1979. Conversely, the Republic of Korea and Brazil substantially increased the actual value of their footwear exports, which is a good indicator that the problem was not so much the fall in global demand but rather the competition from the emerging countries. The crisis was especially important for Spain, due to its heavy dependence on the North American market, where the footwear coming from the new exporting countries was penetrating more rapidly, and because it was more affected by the evolution of production costs and of the exchange rates. Portugal, on the other hand, thanks to its low salaries, became a growing competitor to Spanish footwear; its exports only decreased slightly in 1981, and its share in world exports did not go down but instead increased.

The productive structure of the Portuguese footwear industry continued to grow at a good pace during the 1980s. The Italian industry only underwent a very slight downturn in the number of workers in the first half of the 1980s and, although this trend would go further in the second half of the decade, in 1990 this number was only 6 percent lower than that of 1980. In Spain, however, there was an increase in suspensions of payments and businesses closing, to the extent that the production structure of the sector was considerably reduced, at least in official statistics. The labor force registered in the sector decreased by 14 percent between 1980 and 1985 and more than 40 percent between 1985 and 1990.Footnote 22 To address the situation, in May 1982, the Spanish Government passed a royal decree on measures for the conversion of the footwear manufacturing and associated industry sector, but this plan did not prove to be very effective in practice.Footnote 23

The competitiveness of the footwear industry of the southern European countries was adversely affected by the high inflation they suffered in those years and particularly by the rapid wage growth. Between 1972 and 1983, the hourly working wage in the leather and footwear industries went up by 583 percent in Italy, by 406 percent in Spain, and by 465 percent in Portugal, while in Korea the increase was only 167 percent. In 1983 that cost, compared to Korea, was sixteen times higher in Italy, almost twelve times higher in Spain, and only double in Portugal.Footnote 24 Furthermore, the loss of competitiveness was accentuated in Spain by the evolution of the peseta exchange rate, which went up slightly against the dollar (around 4 percent) between 1970 and 1979, while the Italian lira and the Portuguese escudo experienced a sharp depreciation against the dollar, and also depreciated more than the peseta against the German mark.

The collapse of footwear exports in Italy and Spain in the second half of the 1980s and early 1990s was linked to the evolution of exchange rates in both countries and also, in the 1990s, to a brief but widespread international depression. Between 1985 and 1992, the lira went up 55 percent against the dollar and the peseta by 66 percent, boosted by being linked to the German mark under the European Monetary System (EMS). However, the Portuguese escudo, outside the Exchange Rate Mechanism of the EMS until 1992, went up far less, around 25 percent. In the early 1990s, the problems caused by the reunification of Germany, the increase in oil prices due to the First Gulf War, and the instability of the European Monetary System led to a sudden deceleration of economic growth throughout Europe, which brought about negative growth rates in some of the principal markets for footwear exports from the south of the continent, such as in Germany and France. The European demand for imported footwear not only went down, but it was also largely diverted toward the emerging countries. German imports of footwear coming from Korea, Hong Kong, China, Indonesia, Vietnam, and India, which up to 1990 had not reached 10 percent of the total, from that date on grew rapidly, and in 1993 represented over 20 percent. In the United States, imports from those six Asian countries, which until 1985 had represented less than 20 percent, in 1991 were in excess of 50 percent and in 1993 more than 60 percent.Footnote 25

For all these reasons, the real value of footwear exports was 40 percent lower in 1992 (the lowest moment of this crisis) than in 1985 in Spain and the decline in Italy was 26 percent. In Portugal, in spite of the decrease in 1991 and 1993, in this latter year the value of exports was still higher than the average of the 1988–1990 triennium, although this meant greatly reducing the growth rate. In Italy and Spain, the sector continued losing businesses, which was accentuated in the second half of the 1990s, while in Portugal, growth was halted in the number of employees and a downturn began.

The third of the major crises suffered by the footwear industry of southern Europe began in the early twenty-first century. In all three countries, the new decline in exports began at the same time, in 2002, but had a different duration and intensity. The impact of the crisis was greater in Portugal, where the export levels of 2001 had not yet recovered in 2015 and where the real value of the exported footwear became 37 percent lower in 2006. In Spain, the lowest point of the crisis was reached in 2009, when exports were 34 percent lower than in 2001, but in 2015 a new maximum was achieved again in the real value of exported footwear. The crisis in Italy implied a lower export decline than in Spain (28 percent), but it lasted until 2015.

The drop in exports at the beginning of the twenty-first century was enhanced by the global economy deceleration suffered by Europe and the United States between 2001 and 2003, due to the crisis of technology companies and the impact of the terrorist attacks of 2001 in the United States, factors to which the appreciation of the euro against the dollar was added between 2002 and 2008. When exports were recovering, there was a sharp decline again in 2008 and 2009, due to the impact of the financial crisis. The world export of footwear, which had been close to 12,000 million pairs in 2007, fell below 11,000 in 2009. As in previous recessions, added to this downward trend was the increased competitiveness of Asian exports, due to the end of import quotas for footwear from China and Vietnam in the European Union in 2005, although the quotas were replaced by antidumping duties from 2006 until 2011. The competition of the footwear producing countries in Eastern Europe has also increased since the mid-1990s. Both Asian and Eastern European competition were strengthened by the increasing transfer of footwear production from European companies to countries in these areas with low labor costs.

The production structure continued to go down. In Italy, this reduction accelerated sharply since the beginning of the twenty-first century. If, between 1995 and 2000, production went down by an average annual rate of 4 percent and the number of workers at the rate of 2 percent, in the period 2000–2005 both rates increased to 3 percent and 8.5 percent respectively. In Portugal, from 1996 to 2005, the number of workers in the sector decreased at an average annual rate of 3.5 percent, so that in 2005 it was 30 percent less than in 1995. In Spain, the number of workers declined rapidly since 2001, and this process would not reverse until 2011, when the number of workers was practically half of that in 2001, and production, measured in pairs, was less than half.

The Industry’s Response to the Recession: Lowering Costs

As in other sectors, the footwear industry of southern Europe became more competitive with the various currency devaluations that were made before those countries became part of the European Monetary Union. Also decisive were the various protectionist measures applied by first the national, and later the European, authorities, such as import quotas and antidumping duties on Asian footwear. However, together with these actions taken by the public sector, the industry itself has followed a strategy for staying competitive and recovering from the successive crises. This strategy has basically consisted of two lines of action, at times complementary and other times contradictory. On the one hand, it has tried to contain production costs, mainly by keeping salaries low, resorting to the informal economy and to offshoring. On the other hand, it has sought to differentiate the product and position itself in segments of the market in which the pricing competition is less, by specializing in better quality footwear in which the design and fashion are very important. The industries of the three countries have coincided on the basic lines of this strategy, but these lines have not been applied the same way over time or in each of the countries.

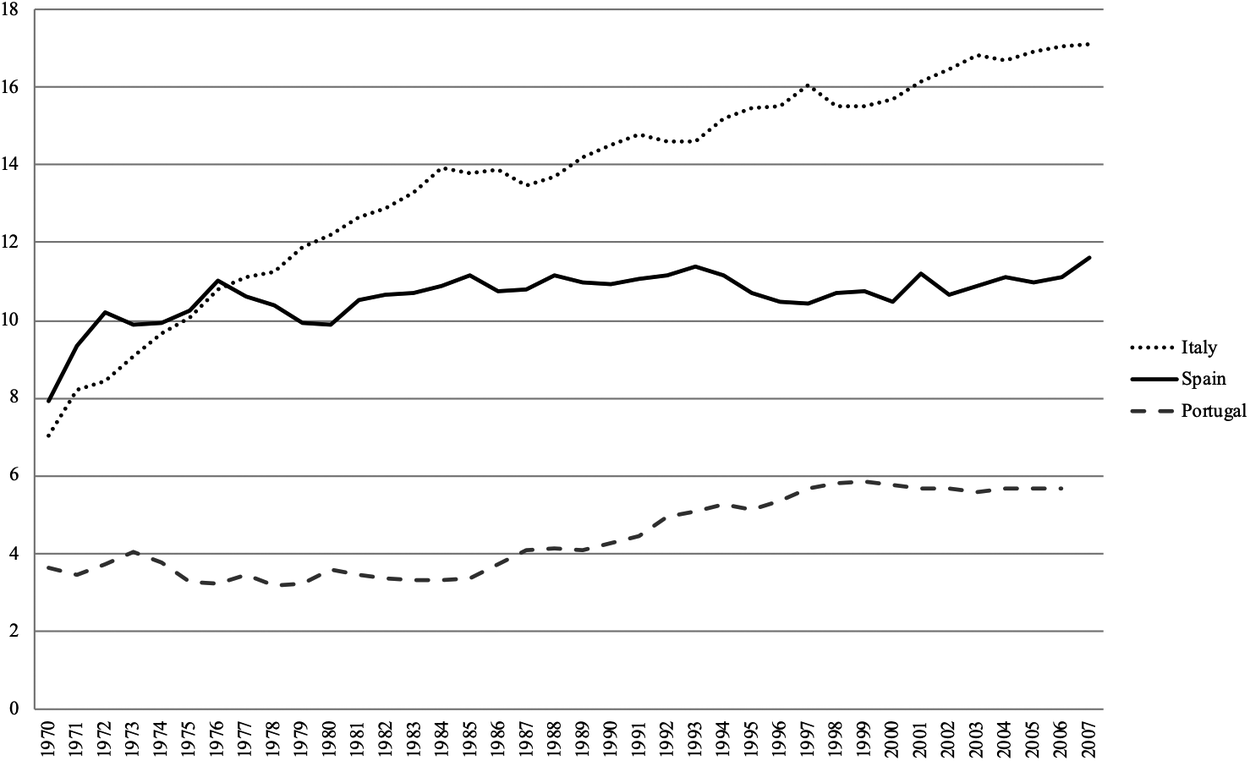

After the recession at the end of the 1970s, real salaries in the footwear industry were contained significantly in the three countries. This happened to a greater extent in Spain, where the hourly working wage in the leather and footwear industries in real terms remained practically stagnant between 1983 and 1990. In Italy it increased by around 10 percent, and in Portugal, which began at very low levels, it almost tripled (around 30 percent). The wage restraints were further emphasized following the recession of the early 1990s. Between 1993 and 2000, the hourly wage rate only grew in real terms by 3 percent in Italy and 9 percent in Portugal, while in Spain it went down by over 10 percent. The stagnation of real salaries continued in Spain in the first years of the twenty-first century and also extended to Portugal, while in Italy it increased 5.5 percent between 2001 and 2006 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Labor compensation per hour worked in leather and footwear industries, 1970–2007 (2010 euros).

Source: EU KLEMS Database.

To summarize, the strategy of wage restraints was mainly implemented by Spain, where the hourly wage rate only increased in real terms less than 4 percent in the twenty-three years from 1983 to 2006, and this strategy was particularly applied from the 1990s onward. In Italy, wage moderation was much less, as the real hourly wage went up by 28 percent in the same period. Following a very different path, salaries in the Portuguese footwear industry increased at a good rate until the end of the twentieth century, only becoming stagnant since the beginning of the twenty-first century.

The three countries also became more cost competitive through the growth in labor productivity. If we look at this variable through the added value per hour of labor, it can be seen that in Italy there has been continuous progress in this respect, only weakened in times of strong crisis. Portugal also saw a rapid growth in productivity until 1997. In Spain there was a spectacular growth in productivity in the 1970s and in the second half of the 1980s. However, this variable suffered a prolonged decline between 1990 and 2004, picking up again from 2005. Labor productivity in Spain, which had remained above the level of Italy until the end of the 1980s, lagged behind considerably compared to the level of the industry in Italy and saw its advantage undermined in respect of Portugal during the 1990s, until 2005 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Gross Valued Added per hour worked in leather and footwear industries (2010 euros).

Source: EU KLEMS Database.

One of the reasons for the different evolution of productivity in Spain as compared to Italy, and to a lesser extent Portugal, is the behavior of investment in machinery. This investment, even if weighted by the value of footwear production, was far higher in Italy and Portugal than in Spain. In the three countries, however, the introduction of technological innovations was very low, at least until the end of the twentieth century.Footnote 26

Another way of reducing costs was by concealing part of the activity, the so-called underground economy; this consists of avoiding labor and tax regulations by different procedures that range from employing workers with no contract and declaring a lower production than that actually achieved in legally established businesses, to the existence of small, totally clandestine factories. This underground economy historically is well rooted in the footwear industry of southern Europe, characterized by small production units, where it was very easy to hide part of the labor and the earnings. However, the crisis heightened the use of this resource as a way of lowering production costs and obtaining greater flexibility for adapting to a highly competitive international scenario.

Due to its very nature, the underground economy is very difficult to quantify. Nevertheless, a large amount of research shows the very significant presence of this phenomenon in the southern European footwear industry. These investigations indicate a constant presence of the phenomenon in the sector, but also an increase in the most critical periods. Thus, in Spain, where in 1979 concealed employment must have been around 13 percent of the total, in 1984 it was more than 40 percent and, according to some authors, clandestinity affected half of the workers of the sector and a third of the production.Footnote 27 Research carried out at the beginning of the twenty-first century shows similar levels of concealment: between 40 and 50 percent of manpower and between 35 and 50 percent of the production value.Footnote 28 Studies on the phenomenon in Italy reveal a very similar situation. In some shoe-manufacturing centers of Campania, the underground economy at the end of the 1990s was put at between 25 and 30 percent, and it was calculated that half the workers were in an irregular situation.Footnote 29 In the Puglia region, clandestine labor was around 50 percent in the district of Barletta and reached up to 80 percent in that of Casanaro-Tricase.Footnote 30 In Portugal, however, research on the subject shows less incidence of the underground economy in the footwear industry until the 1990s (13 percent of disguised employment),Footnote 31 probably due to the fact that, until then, there was a higher corporate concentration in the sector.

We do not have any series that would make it possible to compare the evolution of the weight of the underground economy in the footwear industry in Italy, Spain, and Portugal over the course of the last four decades, but we do have estimations on the evolution of the weight of this concealment in respect to the GDP of the three countries. The Schneider data, for example, show Italy as having the highest level of concealment of the three countries (in fact, the highest level in western Europe) and Portugal having the lowest level, which, since the mid-1990s, would be equivalent to that of Spain (Table 2). These data reflect significant growth of the underground economy during the 1990s and a slow decrease after that, which would stop with the recession of 2009. The same is seen, with considerably lower figures, in the estimations of the National Institute for Statistics (ISTAT) on the evolution of the underground economy in Italy: a rapid growth in the first half of the 1990s and a moderate drop afterward.Footnote 32 In consequence, if the footwear industry adapted to this general framework, the fact of resorting to the underground economy as a response to the recession would have been used throughout the whole period, but more intensely in the 1990s and somewhat more extensively in Italy.

Table 2. Size of the shadow economy (as percent of GDP)

Source: Schneider, "Shadow Economies,” 611, and “Size and Development,” 6.

A third strategy for reducing production costs has been to outsource to other countries with lower labor costs the most labor-intensive stages of the process using unskilled labor, or even the whole manufacturing process. This strategy has, on occasions, resulted in the incorporation of subsidiaries abroad, but it has more frequently consisted of subcontracting these tasks to independent companies abroad and substituting the domestic suppliers of components with suppliers in other countries. This remedy of offshoring began earlier and was more intensively used in Italy, the country with the highest salaries in the sector, while Portuguese businesses, with the lowest labor costs, have used it much less. In fact, during the decade of the 1980s, the industry grew in Portugal thanks to other European countries offshoring work to it, including Spain, but most of those companies abandoned Portugal at the beginning of the twenty-first century to operate in Asia, in the search for lower costs.Footnote 33

Already, as a response to the recession at the end of the 1970s, some Italian companies began subcontracting the more labor-intensive work to other countries, but it was in the decade of the 1990s when the main shoe-manufacturing districts generally adopted this practice, transferring a very significant part of the production process mainly to eastern European countries, with Romania at the top of the list.Footnote 34 Crestanello & Tattara have calculated, using figures from 2005, that the outsourcing to Romania of part of the footwear manufacturing of the Veneto created employment in that country for over 26,000 workers.Footnote 35 Offshoring initially affected the stages of the production process that were more labor-intensive, such as sewing, but it was gradually extended to other stages, and since the beginning of the twenty-first century it even affected the assembly of the shoe, while the geographical area was widened toward Asia, especially to China and Vietnam.Footnote 36

Studies on international offshoring in the Spanish footwear industry show that this was very rare in the 1980s and, although it rapidly increased in the following decade, it remained below the average of the manufacturing industry as a whole and below what happened in the footwear industry of other European countries, such as Italy. Nevertheless, it appears that subcontracting in countries with low labor costs intensified during the first decade of the twenty-first century.Footnote 37

The reflection of this growth in offshoring can be seen in the rapid increase in the importation of ready-made footwear parts, especially in Italy, starting in the mid-1980s. Between 1985 and 2004, the actual value of these imports was increased more than tenfold in Spain and Portugal, and about fifty-fold in Italy. These import levels later decreased, especially following the financial recession that began in 2008 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Imports of prepared parts of footwear in Italy, Spain, and Portugal, 1970–2015 (million of 2010 euros).

Source: Comtrade Database.

The Responses of the Industry to the Crisis: Differentiation of the Product

The footwear industry not only responded to the foreign competition with cost-reducing measures, but also tried to differentiate its offer from low-price footwear coming from the emerging countries. On the one hand, it improved the quality of the product by using better materials, generating and adopting technical innovations, achieving a better finishing, and incorporating an attractive design adapted to trends in fashion. On the other hand, it invested in marketing to strengthen brand names and improve distribution channels. Also, it changed the production structure to be able to offer a wide variety of different models and a quicker response to the demand.

The changes in the production structure mainly consisted of the disappearance of the large footwear companies and the disintegration of the production process, which was broken up into many small businesses specializing in specific stages of the process. This decentralized production organization was made possible by the concentration of the sector in heavily specialized industrial districts, where the dense production structure and the physical and social proximity between the businesses made it easier to outsource the work. In this structure, the central role of coordinating the whole process was held by the parent companies, which often only handled the initial stage (the product design) and the final stage of the process (the marketing).

This decentralized production played its part in reducing production costs as it facilitated the development of the underground economy and also the relocation of companies, because they now did not have to make any major changes to their production organization but simply had to replace their domestic suppliers and subcontractors with companies in other countries. Above all, however, decentralization allowed for greater flexibility in the production structure. On the one hand, it made it possible to adapt rapidly to variations in demand, regarding both quantity and type of footwear. On the other hand, it enabled the production of different products in short series, made within very short periods. The recent evolution of the market, during the last decade, has accelerated the life cycle of the product, meaning that many companies do not adapt their production to the traditional two seasons per year, but instead put out four or even six collections per year, with a multitude of different models, manufactured in short series, which have to be quickly replenished if they are successful on the market. This type of fast fashion has been encouraged by the major vertically integrated fashion chains such as Inditex, which create the design of their footwear and subcontract a large part of the manufacturing work to the countries of southern Europe, particularly Spain and Portugal, solving the difficulty of obtaining such rapid production in countries that are farther away.Footnote 38

The dense relationships between companies and the decentralized production are features intrinsic to the industrial footwear districts, but they intensified following the recession at the end of the 1970s in Italy and Spain and to a much lesser extent, since the beginning of the twenty-first century, in Portugal. This trend can be seen by observing the evolution of the average size of the footwear companies in each of these countries. In Spain, the average number of workers per company went down to practically half between 1980 and 1985, going from thirty-four to seventeen, and the average size continued to decrease until the mid-1990s, after which it went up slightly. In Italy, the average size was below twenty before 1980, but in 1990 it was reduced to little over ten, and although it went up again in the first half of the 1990s, it then established itself at around ten employees. In Portugal, however, the large foreign companies boosted the growth of the sector. This meant that the average company size grew until 1990 and remained high, above thirty employees, until 2000, later being reduced but always being much higher, almost double, the size of Italian or Spanish businesses.

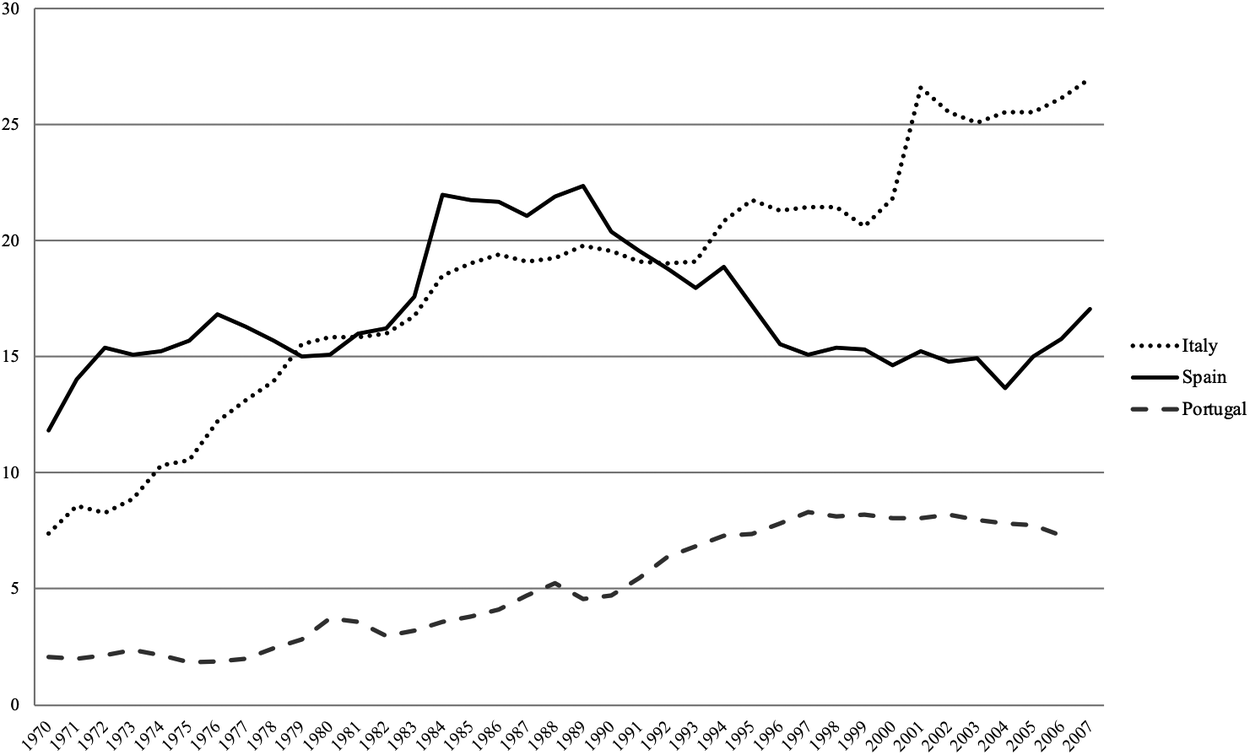

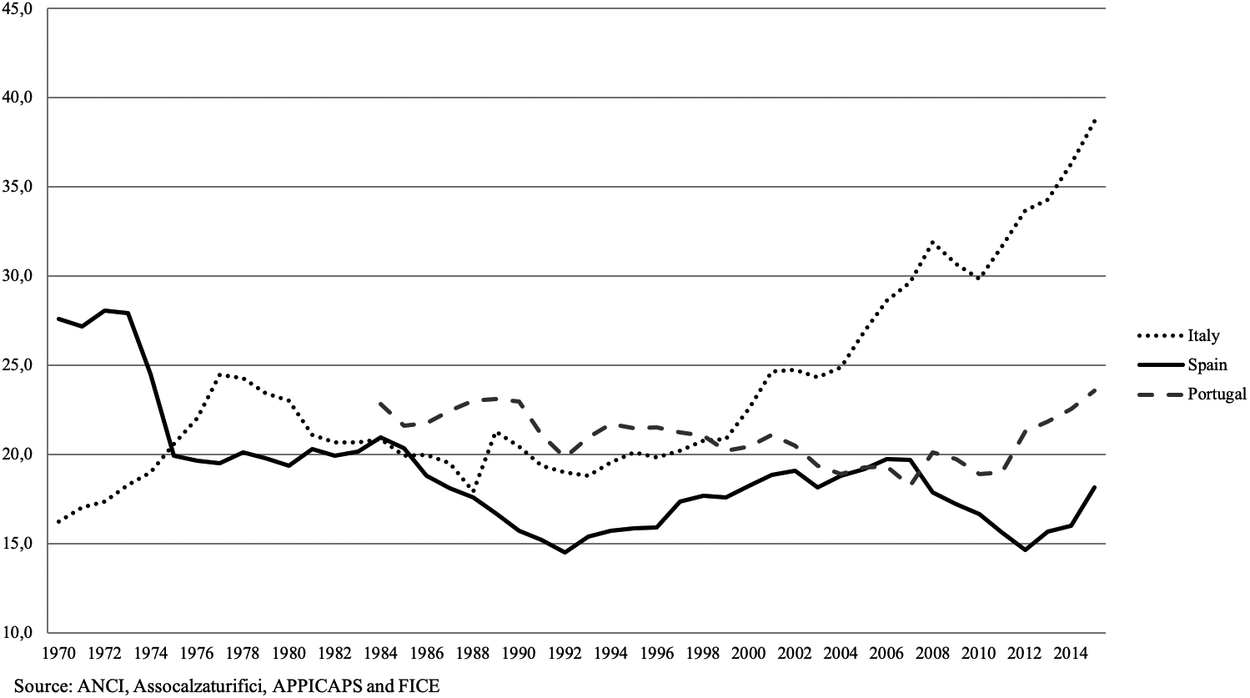

The strategy of raising the quality of the product, finding market niches less affected by the competition from Asian footwear, can be seen through the evolution of the unit values of exported footwear, that is, the ratio between the value in euros and the quantity in pairs, because if the industry manages to export products at a higher price in a competitive market it is probably because the quality is better. However, if we deflate these values to eliminate the effect of variations in production costs, what we see after the recession at the end of the 1970s and beginning of the 1980s is an initial tendency to compete by lowering prices. This is what happened in the Italian industry until 1988 and in Spain until the beginning of the 1990s. Then, in both countries, there was a clearly growing evolution in unit prices, which was especially pronounced in the case of Italy after the beginning of the twenty-first century. The increase in prices was halted by the economic recession in 2009 and 2010 in Italy and caused real prices to go down generally in Spain until 2012. The evolution in Portugal was very different. The takeoff of the Portuguese industry came about with footwear at a high average price and, therefore, footwear of an average high quality. The trend was for real unit prices to decrease until 2011, when they started going up again (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Unit values of exported footwear (2010 euros per pair), 1970–2015.

Source: ANCI, Assocalzaturifici, APPICAPS and FICE.

Therefore, the strategy of upgrading was essentially Italian. Spain joined in after the 1990s, but it was extensively interrupted when the Great Recession began. In Portugal, which was already specializing in medium quality footwear, only in the most recent years can this tendency be seen. In fact, if we consider that, in order to produce better quality goods and develop more complex production processes, increasingly more skilled labor is required, and therefore commanding much higher salaries, only Italy is seen to follow this line since the 1970s until the present day. Real salaries in Portugal improved since the mid-1980s until the end of the 1990s, but then remained stagnant, while in Spain salaries have been stagnant since the mid-1970s.

The process of upgrading went hand in hand with greater attention to creating own brands and the diffusion of those brands on the international markets. Similar to the trend toward higher quality, this strategy was particularly implemented as in the decade of the 1990s and was most notably reflected in Italian footwear. The phenomenon can be seen through international brand applications made by footwear companies through the so-called Madrid system, which are recorded in the Global Brand Database of the World Intellectual Property Organization. To obtain the data, we have reviewed all international trademark applications made by companies in Italy, Spain, and Portugal between 1975 and 2015 that are submitted within class 25 of the Nice classification, corresponding to clothing and footwear, to select brands referred only to footwear or presenting footwear as their main product. This implies that we have not taken into account the numerous brands of clothing and accessories, mostly Italian, which also include footwear. The data make it possible to see that the number of brands registered went up rapidly since the mid-1980s in Italy, the beginning of the 1990s in Spain, and at the beginning of the twenty-first century in Portugal. Italian footwear not only pioneered the registration of international brands, but has also maintained a clear leadership in this field for almost the entire period studied. However, if we calculate the ratio of brands by the amount of footwear exported, it is observed that the recourse to the international registration of the brand was used with more intensity by Spanish companies in the late 1990s and early twenty-first century, while it was from 2004 when Italian companies resorted to this strategy, much more than their competitors in southern Europe (Figure 6).

Figure 6. International footwear brands registered by companies in Italy, Spain, and Portugal, 1975–2015 (number of brands per 10 million pairs exported).

Source: WIPO Global Brand Database.

The Most Effective Resilience Strategies

An econometric analysis has been carried out to assess which strategies have been able to exert a greater influence on the behavior of exports and, therefore, be more effective in supporting the resilience of the industry in each country. The period analyzed is 1970–2007. The years after 2007 have not been included to avoid the strong distorting effect that the recent Great Recession could have. The method used has been the estimation of impulse responses by local projections, introduced by Jordà.Footnote 39 This method allows us to observe the effect of the analyzed variables on exports. We have used as variables those indicators of the different lines of business strategy from which we had enough data series for this type of analysis. To observe the cost reduction strategy, we have used the hourly wage (indicator of labor costs), the Gross Value Added per hour worked (indicator of productivity), and the value of imports of footwear parts (delocalization indicator), the three variables in real terms. To analyze the influence of the product differentiation strategy, we have used the real unit export prices (product quality indicators) and the number of international trademarks registered each year (which reflect the investment in marketing). We have also assessed the effect of variations in the exchange rate of national currencies, as a macroeconomic variable independent of the business strategy. The local projections method measures the dynamic response of exports to a shock in these variables. A shock means an increase in the variable. The responses to these shocks can be seen graphically in Figures 7, 8, and 9. In the figures, “joint” refers to the null hypothesis that all the response coefficients are jointly zero, and “cumulative” refers to the null hypothesis that the accumulated impulse response after four years is zero. Then, when the probability is under 0.05, we can assert that the response is different from zero.Footnote 40 We have calculated local projections and associated confidence bands. We use conditional error bands for local projections (gray dotted lines). They are 95 percent conditional confidence bands. They help to remove the variability caused by serial correlation, and they are consistent with the joint null of significance and more sensitive to the significance of individual responses. Local projections (black continuous line) show the responses to generalized one standard deviation shock.

Figure 7. Local projections for Italian exports.

Figure 8. Local projections for Spanish exports.

Figure 9. Local projections for Portuguese exports.

The econometric analysis shows that the exchange rate is a very significant variable to explain the evolution of footwear exports, which have tended to increase in the three countries in the years immediately following the depreciation of their currency against the dollar. As regards the variables linked to the resilience strategy, the two variables most related to the elevation of product quality (unit export prices and labor cost) seem to be the most positively influential in the growth of exports in Italy. On the other hand, one of the other indicators of the product differentiation strategy, the expansion of the number of international trademarks, seems to have had a counterproductive effect, probably because what increases competitiveness is having strong international brands, not many brands. In Spain, footwear exports seem to have been positively influenced by the improvement of labor productivity, which has allowed them to compete via prices, thanks to the excellent evolution of the Gross Value Added per hour worked until the end of the 1980s. On the contrary, offshoring seems to negatively affect Spanish exports during the first years after an increase in relocation. In Portugal, as in Spain, the increase in relocation seems to have had a detrimental effect, while the increase in productivity would have boosted export growth. The cost of labor also appears as a significant variable, but in the opposite direction of that observed for Italy: Exports respond negatively to the increase in wages, highlighting the importance of low labor costs in the competitiveness of Portuguese footwear. On the other hand, as in Italy, exports also respond positively to the increase in quality reflected in product prices and negatively to the increase in the number of international brands.

If the share in world exports and the evolution of employment are taken as a reference, Portugal has been the country whose footwear industry has shown greater resilience since the mid-1970s. Between 1974 and 2014, shares in world footwear exports from Italy and Spain decreased by around 70 percent, while Portugal’s share increased threefold. The relative decline of the Portuguese industry in the world market began in the 1990s, but between 1994 and 2014 its share of world exports decreased by less than 50 percent. A similar evolution can be observed in employment: In Italy and Spain the number of employees in the sector in 2014 was about 50 percent lower than in the mid-1970s, while in Portugal it had increased by more than two. In the latter country, the number of workers began to decline in the 1990s, but the maximum number of workers reached in 1990 had only been reduced by 36 percent in 2014 (Table 3). Undoubtedly, the greater resilience of the footwear industry in Portugal has been supported by its low labor costs, and this is a feature that can hardly be maintained in western European countries. However, as the econometric analysis shows, Portuguese competitiveness has also been reinforced by specialization in quality footwear, following the Italian example. In Italy, the decline experienced by the footwear industry since the mid-1970s has been important, but the strategy of prioritizing quality has allowed it to continue being the country of Europe with greater footwear production and a greater share in the international market, much greater than the share of any other non-Asian producer. The relocation strategy does not seem to have improved the competitiveness of European footwear producers, but, on the contrary, has been a cause of its weakening.

Table 3. Number of employees and share of world exports of the footwear industry in Italy, Spain, and Portugal, 1974–2014

* 1971 data; **1996 data.A: Employees. B: Percentage of world footwear exports.Sources: APPICAPS, ANCI, Assocalzaturifici, INE and FICE

Conclusions

The mature industries, with easily accessible technology and labor-intensivity, have suffered a notable setback in Europe in the last three decades, due to the very strong competition from the newly industrialized countries, with much lower labor costs, in a context of increasing liberalization of international trade. However, these industries continue to be important in the European Union, essentially for the number of people they employ and especially in those countries and regions with the most specialization. In the case of the footwear industry, Italy, Spain, and Portugal are the three countries that account for the largest part of European production. All three developed in the sector through their exports and continue to be prominent global exporters of footwear. However, at least since the end of the twentieth century, the three have undergone a severe reduction of their production structure and their relative share in global exports. This reduction has been produced basically in various periods of special crisis for the sector, where the principal cause has always been the difference in costs with the emerging countries, but in which the difficulties were further aggravated by other factors, such as the fall in demand as a result of situations of economic recession in the main markets and the evolution of the exchange rate.

Taking the real value of exports as an indicator, it is seen that the periods of crisis in the footwear industry have been basically the same in Italy and Spain in the last half century, and in Portugal since the late 1990s. These crises have responded to the same causes in all three countries, although the impact in each of them has been different, because there were also significant differences in the macroeconomic environment and in the characteristics of the sector in each country. The three particularly negative conjunctures for footwear exports in southern Europe were the years of the second oil crisis, the period from 1986 to 1993, and the first decade of the twenty-first century.

At the origin of the three crises we find both supply and demand factors. The former were particularly influential in the 1970s (due to the rise in the cost of energy, intermediate products, and labor) and in the second half of the 1980s (due to the loss of competitiveness caused by exchange rates), whereas the crisis of the first decade of the twenty-first century was mainly driven by declines in demand as a result of the 2001–2003 economic crises and the Great Recession. Nevertheless, the difficulties of the industry in the 1970s and early 1990s were also accentuated by the decrease in demand that the general economic recession caused in the main consumer markets, whereas the decline in the twenty-first century has been influenced by the elimination of trade barriers to Asian imports.

The crisis of the late 1970s and early 1980s barely affected Portugal, which was then protected by its extremely low salaries and did not yet have any significant presence in the international market. In Italy it was more serious because, from that point on, they would not recuperate the maximum exportation level of 1979, but its impact on the production structure, at least in the short term, was minor. In Spain, however, where salaries had gone up more and the evolution of the exchange rate had had a more unfavorable effect on exports, the crisis was very intense and forced a broad reconversion of the sector, with the disappearance of thousands of jobs.

The crisis of the second half of the 1980s and early 1990s also had much more effect on the Italian and Spanish industries, adversely affected by their currencies going up considerably against the dollar. The problems lasted until the early 1990s due to the international economic depression, so in the two Mediterranean countries, the number of businesses and workers in the sector continued to go down, while in Portugal, where the decrease in exports was small, only its growth was slowed down. However, in the third of the great recessions at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the Portuguese industry was the one that was most adversely affected, and by losing its advantage of labor costs, the multinationals that had launched the industry on the international market abandoned the country in search of more advantageous conditions elsewhere.

In the three countries, the footwear industry has responded to the situations of recession with a similar strategy. On the one hand, they have tried to reduce production costs, to increase competitiveness based on price, restraining salaries and improving productivity, recurring to the underground economy, and outsourcing the more labor-intensive phases abroad. At the same time, they have followed a strategy of differentiation of the product, through better quality, greater diversification of the offer, and more attractive designs that are more in line with fashion trends. In the three countries we have found all these responses to the crisis, but we also observe important differences in the intensity with which each response has been implemented and the moment when each has been used.

The restraints on wages, which went up in the footwear industry at a rate far below that of the manufacturing industry as a whole, were applied in Italy and Spain above all in the decade of the 1990s, whereas in Portugal this would not take place until the turn of the century. The use of this measure was particularly prominent in the Spanish footwear industry, although the country with lower labor costs has always been Portugal. It also appears that it was during the decade of the 1990s when the underground economy was most widely spread in the sector and that Italy was the country where the phenomenon reached its greatest scale, although its presence in Spain was also considerable. The offshoring of the more labor-intensive stages of the production process to countries with lower salaries was another strategy for reducing costs that was used more extensively since the 1990s and again in Italy particularly. Offshoring took place much less in Spain and less still in Portugal, at least until the first years of the twenty-first century.

The development of the underground economy and the resorting to offshoring, even by small and medium businesses, were facilitated by the sector being concentrated in highly specialist industrial districts and, mainly in the cases of Italy and Spain, by the decentralisation of production which became more widespread from the 1980s. The division of the production process among numerous small companies specializing in only some of the stages of the process, also gave the industry more flexibility and the ability to adapt to the demand, while at the same time allowing more diversification of the offer, making it possible to manufacture many models in small batches and for short periods of time. The strategy of differentiating the product was also based on raising the quality and the design and fashion content, to be positioned in a segment of the market less sensitive to labor costs. The course followed by the unit prices of exported footwear shows that this strategy was continued for more time and with more conviction by the Italian industry, while the tendency in this respect in the Spanish industry suffered a serious setback with the Great Recession. In Portugal, although the development of the industry was based on the export of high quality footwear since the 1980s, the upgrading strategy was not firmly adopted until the second decade of the twenty-first century. The same impression is obtained from looking at the investment of the companies of each country in the creation of internationally recognized brands. This strategy was implemented mainly from the end of the twentieth century, with the Italian industry taking the clear lead.

The econometric analysis that has been carried out confirms the strong short-term influence of the exchange rate on the competitiveness of the footwear industry and suggests that the resilience strategies of the sector had common elements in the three countries, but also distinctive features in each of them. The strategy of improving product quality and design (measured by average export prices) stands out in Italy and Portugal. In Spain, on the other hand, the most influential variable in export growth is the improvement in productivity, a variable that is also significant in Portugal. The wage restraint seems to have boosted the competitiveness of the Portuguese industry. In Italy, however, the increase in wages appears linked to the increase in exports, probably because higher wages imply higher production quality. Both in Spain and Portugal, offshoring seems to have limited export growth in the short term, perhaps because this strategy has made it easier for countries with lower labor costs to export finished footwear directly.

Comparing the evolution of the footwear industry in the three countries since the 1970s, Portugal is the case that shows greater resilience. Its competitiveness has been supported by very low labor costs, a strategy that is hardly sustainable over time in western Europe. However, Portuguese footwear exports have also benefited, as the econometric analysis suggests, from productivity improvements and specialization in a high quality product. Therefore, the resilience of the sector seems to have depended both on the ability to contain costs and to differentiate the product. Because competing in costs with emerging countries is impossible, the future of the sector will probably depend on the latter, mainly on strategies to raise quality and promote design and fashion. In fact, the Italian industry, which has focused on this strategy, is the European footwear industry that has managed to maintain the largest production structure and export capacity.