In June 1957, the New York City sales branch of the television manufacturer Admiral hosted an open house. Hundreds of appliance dealers from the area were invited to take a look at the models for the upcoming season. However, before the dealers were entitled to place their orders, they had to meet two requirements. First, they needed to sign a Dealer’s Agreement, in which they agreed to keep a representative stock of Admiral products, to place them in a favorable way, and to always “present the true quality, merits and user advantages of Admiral products to prospective buyers.” Footnote 1 Second, the ordered quantity had to reach a level set by the sales branch. If the dealer did not fulfill either of these two requirements, the dealer was cut off from the market of Admiral television sets. As if to compensate for the strict rules, the contract completions were comparatively pleasant. Dealers were led to a “Keeper of the Keys,” where they were allowed to draw a key from a fish bowl. The key opened one of three chests. In the first, the dealer found a $25 stock certificate from the Financial Industrial Fund. The second one yielded a 10-inch portable TV set. With a key to the third chest, the dealer hit the jackpot: it allowed two persons to spend one week in Bermuda. Footnote 2

The 1957 open house was not at all extraordinary for the way television sets in the 1950s changed hands along the distribution chain. Distributors and their dealers not only received stock certificates and portable TVs, but also watches, whiskey, sports gear, or turkeys. They also traveled to Bermuda, Florida, New York, Paris, Rome, Acapulco, Havana, Virgin Islands, French Riviera, and many other places. “Today’s appliance dealers,” a manager remarked somewhat disparagingly, “are the best traveled class of businessmen in the United States.” Footnote 3 Having recently spent one week in Las Vegas with 240 dealers and distributors of the manufacturer Westinghouse, the editor of the special trade journal, Merchandising Week, and a television dealer himself, was quick to defend the practice. Friends could be made, and experiences and information exchanged. Dealers and distributors who usually saw each other only for a short amount of time could finally meet on a personal basis. He concluded: “Incentives are the tinder that ignites the sales fire (…). There is that curious quirk in human nature that puts some things above dollars.” Footnote 4

Business historians have so far largely neglected the role of material incentives. The reason may be that incentives did not strike them so much as important as curious by-products of market transactions that carried little weight with respect to the relations of manufacturers, distributors, retailers and consumers. Historic treatment about incentives is often unsystematic and anecdotal, or it focuses on the premiums that final consumers received as part of a company’s sales strategy. Footnote 5 In economic terms, too, material incentives can be easily conceptualized as merely a “veil” that signifies a certain amount of financial concession. In this sense, a premium worth ten dollars is no different to a price reduction worth ten dollars. Both have the same effect of luring distributors, dealers, and consumers into a purchase but do not tend to otherwise change their behavior.

It is true that even in the 1950s material incentives were hardly “above dollars.” They involved monetary costs for the suppliers and reciprocal measures for the beneficiaries. However, they cannot be fully grasped with the concept of monetary incentives, either. Travel vouchers and turkeys differed from cash payments and price reductions because they responded to a specific constellation of distributors and retailers. They had a direct impact on competition in the market for television sets. They did not change the prices that distributors and retailers had to pay their suppliers, so they tended to stabilize prices on the sales floor as well.

The term “turkey economy” suggests that rather than being a curious by-product of market transactions, material incentives were an integral part of the market and how it functioned. It refers to a specific market culture that, in the case of television sets, had become established with the rise of the product in the late 1940s. The first aim of this article is to give context to the term and to provide an explanation of why material incentives had such a central importance in the American market for television sets.

Had the editor of Merchandising Week traveled to West Germany instead of Las Vegas, he would have looked for the “curious quirk in human nature” in vain. Those across the Atlantic were much more skeptical of the prospect of material sales incentives than those in the United States. Trade associations, brands producers, distributors, retailers, and even consumers shared in a common understanding that looked with suspicion on any kind of premium. A West German law that prohibited the use of giveaways on the sales floor substantiated this attitude. When American companies entered the West German market, one of the first things they learned was that this sales strategy did not fit the West German market culture. There was no turkey economy. If American companies wanted to avoid the hostility of their competitors and the prospect of legal charges, they had to adapt. Footnote 6

What explains the differences regarding material incentives? If business historians have paid attention to the country-specific use of material incentives at all, they have attributed it to two different kinds of competitive cultures in West Germany and the United States. Footnote 7 This paradigm is well established. Until well into the second half of the twentieth century, the West German business community was cartel-oriented, orderly, and conservative in trying to avoid competition at all costs. The American business community was free-market and competitive. Alfred Chandler captured the dichotomy in a nutshell by his contrast of German “cooperative” versus American “competitive” managerial capitalism. Footnote 8 Similar juxtapositions in comparative history and social studies are easy to find. Footnote 9 In this light, on the one hand, the role of material incentives reflects a cultural reluctance on the part of West German businesses to engage in any competitive behavior. On the other hand, it proves the aggressive behavior of American businesses in striving for market share.

This article will propose a different interpretation. It will confirm that West German businesses tried to eliminate price competition through means of a “television cartel,” including collective agreements about resale price maintenance and rebates. However, by providing a detailed comparison of market relations in the two countries, the article will also demonstrate that control and price stability, rather than aggressive competitive strategies, were the driving forces in the United States. While the means were undoubtedly different, the end was the same in both countries. The second aim of the article is to show that in a comparative perspective, the social embeddedness of markets shaped business relations and strategies in different ways without confirming the static dichotomy of the two competitive national cultures.

Means, however, were tied just as much to the country-specific institutional setting as they were to time. On the sales floor, material incentives in the form of bonuses, giveaways, or lotteries have remained an important part of consumer market transactions. Footnote 10 With respect to relations between manufacturers, distributors, and retailers, however, their importance has faded since the 1960s, giving rise to new kinds of market relationships. Why did the turkey economy cease to exist? The third aim of the article is to answer this question by analyzing the factors responsible for its decline, thereby adding to a growing literature on the changing roles of intermediaries along the distribution chain. Footnote 11 It will do so by maintaining a comparative perspective with the fate of the television cartel in West Germany, opening up venues for generalizations about the historical transformation of consumer markets in Western societies.

The turkey economy and the television cartel were specific in time as well as in space. They are two case studies to examine more closely the socio-cultural context and historicity of markets and market relationships. Roland Coase, some time ago, remarked that in economic theory, markets played an even more “shadowy role” than the firm. Footnote 12 Apart from some rare cases, they still play the same role in business history. Footnote 13 The article is an attempt to address this research gap and to add to a historical understanding of markets and market relations. It is structured around the three questions asked above. It first answers the question why material incentives played an important role in the relations between manufacturers, distributors, and retailers in the United States during the 1950s. It then explains why material incentives did not play a similar role in the West German market. Finally, it unfolds the reasons for why the turkey economy and the television cartel ceased to exist. The concluding statement will demonstrate that by analyzing the reasons for the emergence of the turkey economy and its decline, we can learn something about the meaning of institutions, the cultural specificity of markets, the role of structural change, and the historical transformation of markets.

Material Incentives and the Turkey Economy

To understand the importance of material incentives in the relations between manufacturers, distributors, and retailers during the 1950s, it is necessary to take a closer look at the way distribution, competition, and pricing in the market for television sets worked. Like most consumer goods, television sets reached the consumer by a three-step model of distribution consisting of manufacturers, distributors, and retailers. Footnote 14 Manufacturers designed and manufactured the product, organized information sessions for distributors, and carried out nationwide media campaigns. Distributors organized transportation, warehousing, and allocation of the sets from the manufacturer to the different retailers. They provided retailers with information, training, and credit; offered servicing and workshop services; and conducted regionally specific advertising campaigns of their own. Distributors could be independent businesses as well as factory or sales branches, although both performed essentially the same functions.

Retailers provided their customers with display of the products and buying advice, sold guarantee contracts, and took in trade-ins. They also frequently dealt with broken-down sets either in their own facilities or in cooperation with their distributors. Every actor along the distribution chain performed specific services that were reflected in the prices charged. Since the services were instrumental for the market to function, it is analytically useful to speak of a value chain instead of a distribution chain, which tends to suggest that the product was merely delivered from one place to the other.

Each of the three points of interaction constituted a market in its own right. At each point, there were buyers and sellers as well as distinct market prices. Unless they shipped TVs to their own factories, manufacturers sold their sets to independent distributors. Distributors sold the sets to retailers. Retailers sold them to consumers. However, unlike economic theory of market behavior would suggest, prices were not determined by the autonomous interaction of buyers and sellers. They were determined by a system based on manufacturers’ suggested list prices; that is, prices that were calculated by the manufacturers in the far distances of Chicago or New Jersey. Neither the distributors nor the dealers practiced an autonomous pricing policy. Most of them advertised the list prices in their regional advertising campaigns and tried to stick to them. Footnote 15

The effect of manufacturers’ list prices on competition was obvious. Sticking to a fixed price meant that every store was asking the same price for the same set. There was—ideally at least—no price competition between the distributors, and no price competition between the radio and television stores, either. Since trade margins were sufficient to secure profits along the value chain, the system was beneficial to everyone but the consumer. To be sure, the traditional specialty stores were not the only ones to sell television sets. Even at the beginning of the market for television sets, they were challenged by department stores and discounters. In the early 1950s, however, this kind of competition did not challenge the pricing policy of the traditional radio and television stores. The department stores were, for the most part, service-oriented and practiced a similar pricing strategy. The discounters were only a minor factor.

Most distributors and retailers were traditional, independent businesses that first surged when radios became a major consumer product during the 1920s. Radios diffused rapidly, despite their initially high prices, with “technophile” consumers leading the way. The number of radio manufacturers exploded, despite that most of the relevant patents were held by the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), which was unwilling to license its technology. Facing limited market share, RCA initiated a strategy that proved path breaking for the specialty trade in the long run. Along with suing its competitors, the corporation’s president, David Sarnoff, also implemented rigid control mechanisms that favored retailers and distributors that specialized in consumer electronics. Distributors that ordered only radio components, but not fully assembled sets, were dropped. New orders for radio tubes had to be legitimized by a return of the broken ones. Footnote 16

Sarnoff’s initial strategy to control the market for radios failed. The company proved unable to control the radio market and came increasingly under pressure for violations of antitrust regulations. Even in 1923, RCA dropped its strategy in favor of granting licenses, but it kept control of its distribution chain. By the mid-1920s, over 90 percent of radios manufactured in the United States were based on RCA technology. Footnote 17 Around that time, radios entered another stage in the product life cycle. Manufacturers now started to address households unfamiliar with the technology and willing to pay a premium for advice. Most major radio manufacturers of the 1920s adopted a distribution policy based on privileged independent wholesalers and authorized dealerships similar to Admiral’s dealer’s agreement. A good example is Philco, which had entered the radio market as early as 1928, and used its existing dealer organization from the time it produced radio batteries and Socket-Powers. The company soon became the leader in radio sales, and it introduced incentive schemes for “cultivating its distributor network” similar to the ones later known in the market for television sets. Footnote 18 The central role of the specialist trade remained intact throughout the rest of the 1920s, but it was threatened when the Depression and technological change led to a more price-sensitive market dominated by cheaper and smaller radio sets called “midgets.” Confronted with declining profits and competition from large retailers such as Montgomery Ward and Sears, many dealers threw in the towel. Footnote 19

The breakthrough of television starting in the mid-1940s led to a revival of the small specialty retailers in consumer electronics, which came to be considered “traditional” radio (and television) stores. Given the dramatic experience of falling profits during the 1930s, these dealers appreciated the list-price system that had been, as one appliance dealer remarked, “hallowed in tradition for over half a century in our industry.” Footnote 20 Their distaste of intensive price competition became most obvious in their characterization of those dealers who succumbed to it. The editor of a special trade magazine spoke of a “virus” having infected those dealers who sold off-list. Footnote 21 Another commentary spoke of “cannibalism,” “jungle tactics,” and a “cancerous condition.” Footnote 22

To some extent, the criticism of traditional dealers was directed at the discounters in the appliance trade that had made a business model out of charging prices below list. However, it also reflected the fact that even in the world of traditional retailers, ideal and reality were not necessarily the same. In most cases, list prices were merely suggested, not mandatory. If sales faltered, the most obvious strategy of the seller was to reduce the price of the seasonal product. Cutting prices across the board, however, was problematic. It meant not only a loss of profit and an organizational effort in reprinting list price sheets, but it also meant that dealers who had stocked the old-priced sets were put in a difficult position. A more elegant solution was to make some sort of special offer to those buyers who were willing to take on additional sets, although there were problems with that strategy, too. The first one was that regulatory agencies could see it as a price discrimination that was outlawed by the Robinson–Patman Act. The second one was that it endangered the list-price system. Footnote 23 As the case of television manufacturer Admiral shows, both problems did indeed exist. The way they were tackled, however, explains the central role of material incentives.

Admiral was confronted with the legally dubious nature of price discrimination when the Federal Trade Commission initiated a proceeding in the late 1950s. Based on the Robinson–Patman Act, the manufacturer was accused that its sales branches were charging different prices to their customers and granting selective and disproportional allowances to its dealers. Having collected extensive material from three Admiral sales branches (in New York, Milwaukee, and Washington, DC), the prosecution based its charges on a number of price sheets that showed different prices for different dealers. Admiral admitted to having discriminated in pricing, but defended itself by invoking the exemption of cost justification. Larger sales volumes made for lower transaction costs, and it was only the larger dealers that had the privilege of favorable price sheets. Cost justification, however, was difficult to prove in detail. Footnote 24 Unable to reach an agreement with the commission at this stage, hearings with employees of the sales branches and with Admiral dealers were arranged to answer the question whether Admiral had, in fact, violated the Robinson–Patman Act. Footnote 25

The hearings revealed a complex picture of pricing relations along the value chain. It soon became obvious that the price sheets had hardly any informative value. Instead, the transactions between the distributor and the retailers were superimposed by what the hearing examiner at one point called a “messy pricing system.” Footnote 26 The commission noticed in its final opinion: “The net prices to the various customers were so complicated and modified by a confusing welter of deals and discounts as to make respondent’s price lists almost useless.” Footnote 27 By “deals,” the commission meant relatively spontaneous adjustments of prices, and “discounts” referred to a special kind of price reduction that could take on many different forms. One of these were “promotional allowances,” which were initiated either at Admiral headquarters in Chicago or by regional sales branches. When Admiral introduced its new portable TV sets in 1956, for example, retailers had the chance of being granted a discount if they placed the sets in their windows for a specified length of time. Footnote 28 The discount was not granted in the form of a price reduction. Instead, dealers received a cash payment once the promotion was over. Footnote 29 Officially, promotional allowances were granted for the provision of promotional services on the part of the dealer. Footnote 30 Often, however, payments were received without any service. As the commission concluded in its opinion, the term “‘promotional allowance’ as it appeared on invoices was a fictional statement to cover up price reductions.” Footnote 31

Another example of “discounts” was the material incentives that were usually tied to the number of sets ordered. The Admiral sales branch in New York City, which had hosted the open house in 1957, offered turkeys, whiskey, watches, or travel vouchers for the popular Grossinger’s Resort Hotel in the Catskill Mountains. Footnote 32 It even made some suggestions as to how the material incentives might be used. Retailers could, for example, set a sales quota that, if met, would be rewarded with a little party, including turkey and whiskey. This would not only speed up sales, but it would also strengthen the morale of the staff. Retailers less inclined to socializing got the suggestion to initiate a competition between salespeople. The winner would receive a turkey and two tickets for a Broadway show in New York City. The retailer would have to buy directly the tickets for the show, but the cost would be “more than offset by two bottles of Five Star [whiskey] which the dealer could keep for himself.” Footnote 33 Often, manufacturers and distributors skipped the storeowner altogether, and gave incentives, called spiffs, directly to sales personnel, sometimes even behind the storeowner’s back. Footnote 34 These examples show that “above dollars” material incentives were clearly financial incentives, with a request for reciprocal measures working in the background.

The commission, however, had a hard time comprehending what turkeys and whiskey meant for competition in the market for television sets. It was obvious that they were mostly directed at the smaller traditional retailers and their sales personnel. Were smaller dealers at a disadvantage when they were granted material incentives instead of actual price reductions? The prosecution was critical:

We don’t agree that if a non-favored customer pays $105.00 for a television, but gets himself a ham or a bottle of whiskey, that is worth $5.00, that he in effect is paying the similar hundred dollars that the favored customer is paying. Footnote 35

The hearing commission was internally divided. On the one side stood Philip Elman, who claimed, “[I]f the cost is reduced by the value of the bottle of liquor that he [the dealer] got, the benefit would (be) increased.” On the other side stood Paul Rand Dixon, who argued the dealer was in the business of buying and selling television sets, not whiskey. Footnote 36

Admiral’s defense counsel tried to present material incentives as something actively demanded by the dealers. When one member of the hearing commission commented that Admiral had obviously granted price reductions to some dealers, but pushed turkeys on others, he countered:

They did not push the turkeys on them. They did not have to do that (…). They were good turkeys. And the only thing is that (…) when Christmas came around, the dealers said to the salesmen, “When are you going to have your turkey sale? Are you going to have it again this year?” They were in demand! Footnote 37

The statement of a favorable view of material incentives was not entirely wrong. It did not, however, have so much to do with a taste for turkeys. The more important reason was that by handing out turkeys, whiskey, or travel vouchers, manufacturers and distributors had found a way of getting rid of their seasonal products without increasing a dealer’s margin. What was crucial about material incentives, and what differentiated them from price reductions, was that they did not change the prices the retailers had to pay. The selling price stayed the same, so the retailer’s scope for price reductions remained limited. As the Federal Trade Commission summarized in its findings: “This was done so that the general price structure could be maintained since in this type of industry if prices are broken they can never be restored.” Footnote 38 Some dealers had more whiskeys and more turkeys, but their price competitiveness remained limited. Given their distaste of price competition at the retail level, it was precisely what they wanted. Discounts, in the sense of cash payments received at a later point, resembled price reductions, but at least they left the price structure intact.

If market transactions along the value chain had been isolated from each other, the wishes of traditional retailers would not necessarily have affected the pricing decisions of manufacturers and distributors. Why should they care about the fate of their transaction partners once they had been able to sell the product? Admiral, in particular, was known for pursuing a rather low-price, aggressive sales strategy that seemed at odds with the manufacturer’s extensive use of material incentives. Footnote 39 During the 1950s, the reason was that the interconnectedness of the value chain of television sets prevented manufacturers and distributors from adopting an uncaring attitude. There was a long-term aspect to the exchange that outlasted the single-market transaction. Appliance dealers did not spring up like mushrooms, and good ones were just as hard to find as to keep. The open house of 1957 symbolized the mutual dependency of actors along the value chain by combining quality control with pleasurable experience. It was documented by the franchise contract that strengthened relationships along the value chain. It turned market relationships into long-term affairs and tied them to specific conditions. At the same time, franchising provided protection against free-rider behavior. Footnote 40 Price discrimination as a short-term price competitive measure bore the risk of losing more dealers than winning in return. As a distributor for Crosley and Bendix stated, he would not discriminate in prices because he wanted retailers “that will stick by him over the long haul.” Footnote 41

Mutual dependency was strengthened further by the fact that traditional specialty stores were important for more than individual marketing prospects. Especially during the first years of the market for television sets, they were also important for the market in general. Television sets were new and exciting products. Footnote 42 In the late 1940s and early 1950s, most people who bought their first sets were unfamiliar with them. Given the potential risk of high costs for the wrong product, trust in the forms of reliable advice and services were crucial for the market to function. Because these responsibilities were divided along the value chain in a specific way, manufacturers and distributors had an interest in maintaining the profits of the dealers that offered advice, services, and credit. Performing these services distinguished the traditional radio and television stores from the discounters.

Since the traditional specialty stores appreciated the list-price system, manufacturers and distributors faced a dilemma. As soon as supply outstripped demand, they could either reduce the prices of their sets—upsetting the discriminated dealers—or they could stick to the prices and have television sets pile up in their warehouses. In this dilemma, we can find the answer to the question of why material incentives played an important role. They were a compromise that paid tribute to the interests of the smaller traditional radio and television stores, while at the same time they allowed manufacturers and distributors to compete.

The German Television Cartel

In West Germany, television sets reached households roughly ten years later than in the United States. Footnote 43 In many ways, the German market for television sets resembled the characteristics of the American market during the first years of its existence. Television sets were unfamiliar products to most people, and cost a substantial amount of income. Footnote 44 The three-step model of distribution and the retailing structure were basically the same. Footnote 45 Small traditional retailers that provided advice, servicing, and credit dominated the market. With respect to pricing along the value chain, however, there was a considerable difference from the United States. Material incentives played a small role, if any at all. One television dealer in the mid-1950s criticized the practice of handing over great and pompous gifts as “totally unbusinesslike.” Footnote 46 Although some material incentives may have been exchanged among manufacturers, distributors, and dealers, nothing in the sources suggests anything but a marginal importance.

The attitude of the dealer was substantiated by the official position of German trade associations and German law. The Markenverband stated in its voluntary rules of competition:

Manufacturers commit an offence against morality if they unduly influence their buyer’s employees or the buyer himself by organizing price competitions or tours, hand out prizes, premiums, or some other kind of pecuniary advantages with the aim of obtaining orders or some special handling of their product. Footnote 47

Law entered into the picture because an offense against morality was a justified reason for complaint, as stated in the German Unfair Competition Act. Also, the Ordinance on Bonuses (Zugabeverordnung, dated 1932) outlawed any free giveaways with a product because this would prevent the consumer from being able to judge the price and quality of different offers. Footnote 48

At first glance, the difference seems to be the direct effect of opposite cultural attitudes. Footnote 49 The hostility of West German businessmen toward material incentives, and the self-consciousness with which they rejected them, documents a deep-seated, widespread, and shared belief. However, in light of the reasons for material incentives in the United States, this belief is rather perplexing. Therefore, the more compelling—or complementary—reason for the difference was that West German retailers were embedded into a different system of pricing relations. At the center of this system stood resale-price maintenance, an institution that allowed manufacturers to legally bind their buyers to stick to the selling price dictated by them.

Since the same price needed to be asked of every retailer, the effect was to kill price competition for the same brand products at the retail level. In that way, it bore a close resemblance to the list-price system in the United States; the difference was that resale-price maintenance was legally enforceable. To be sure, resale-price maintenance had a long tradition in the United States, too. Footnote 50 For example, brand producers had practiced it in the late nineteenth century, and the Miller–Tydings Act of 1937 and the McGuire Act of 1952 had legislatively strengthened it. Although department stores, discounters, and mass merchandisers fiercely fought resale-price maintenance because they wanted an autonomous pricing policy, it still existed in the 1950s and 1960s. Footnote 51 Due to state law differences, however, it was fragmented, and most manufacturers had started losing interest in it because of difficulties in enforcement. Footnote 52 Sales of price-controlled television sets were limited to some models, temporary, and largely restricted to the state of New York. Especially with respect to national sales strategies of manufacturers, it played a limited role in the market for television sets, with Magnavox being an exception to the rule. Footnote 53 Even General Electric, an energetic supporter of the strategy for resale-price maintenance, refrained from it when it came to television sets. In West Germany, on the other hand, resale-price maintenance was at the core of the television set industry’s strategy.

In July 1958, representatives from the major German television manufacturers met to agree to a collective introduction of resale price maintenance. Covering about 80 percent of total market share, the group was soon known as the West German “television cartel.” Resale-price maintenance had been practiced in the consumer electronics industry since the beginning. After the law against restraints of competition had legalized resale-price maintenance, but outlawed most other means of collusion, the institution became a focal point for the cartel-minded West German industry. Footnote 54

The consumer electronics group in the West German electronic industries association (Zentralverband der Elektrotechnischen Industrie) had been adamant in pushing for resale-price maintenance because it was sure that, otherwise, the market would soon be in “shambles.” Footnote 55 In 1960, the collective agreement to practice resale-price maintenance was substantiated by a rebate cartel. The agreement set collectively binding rates of trade margins for distributors and retailers based on their total buying volumes. It was supposed to prevent manufacturers and distributors from competing against each other by granting higher discounts to their customers.

As with stable prices in the United States, resale-price maintenance had been a central demand of the traditional radio and television stores in West Germany. Even by the 1930s, the National Socialist Party’s economic policy had strengthened the position of specialty distributors and retailers (Fach-Groß- und Einzelhändler) by confining sales of radio sets to these stores. Additionally, it had also established compulsory resale-price maintenance in the retail sector. Footnote 56 Given this historical background, radio and television stores saw a collective agreement and centrally controlled prices as the only means to guarantee safe profits and stable markets. The collective structure of the agreement and mutual understandings of good business conduct made material incentives less likely and less popular. Retailers worried less about discriminatory price reductions and their effects on price competition. Since West German businessmen supposed material incentives would undermine and destabilize a cartel structure that was founded on collective rules, neither the manufacturers, nor the distributors or the retailers, had an interest in them. In fact, West German businessmen did not quite understand the idea of material incentives as it worked in the United States. Much to the contrary, they saw premiums as an especially brutal form of competition. In its one-sided perspective, this was precisely the interpretation later adopted in West German business historiography.

The Decline of the Turkey Economy

When the Federal Trade Commission carried out its investigation in the second half of the 1950s, it not only revealed the inner workings of a complex pricing system, but it also presented some evidence that the system was already on the decline. As it turned out, many traditional retailers had begun to dislike the turkeys. The reasons for the change can be broken down into two major lines of argument. The first refers to structural change in the value chain; the second to consumer behavior and the product-life cycle of television sets.

First, the mid-1950s saw the rise of a new kind of discounter, the so-called mass merchandiser. Discounters had always played a role, that is, there had always been price-competitive dealers charging lower prices than the traditional radio and television stores for the same branded merchandise. Early in the market for television sets, department stores such as Macy’s had engaged in price competition, but soon they adopted a sales strategy more in line with that of the specialty stores. Sears became an important competitor, but it did not engage in intrabrand competition because it sold its own private brand. Until the mid-1950s, price competition in the TV market, therefore, had mostly come from small, independent stores. They did not differ so much from the traditional radio and television stores in size and organization as they did in assortment and pricing. Providing neither guarantee nor service, and focusing on a small product line with high turnover, the traditional discounter was able to sell at below-list prices.

Mass merchandisers were different. They took credit and provided some rudimentary services. They also differed in organization. Mass merchandisers were much larger than the traditional discounters, and they were usually organized as regional chains. Their buying power was stronger and they could successfully lower the prices of their suppliers. Passing on at least some of these savings to the consumer was a central aspect of their competitive pricing strategy. Contrary to traditional discounters, however, mass merchandisers explicitly refrained from discounting off-list prices and from bargaining with consumers. Footnote 57 The organizational structure was professionalized to include accounting, inventory control, and the early introduction of electronic data processing systems. Footnote 58 Unlike in smaller stores, it was not the owner who acted as the buyer but someone in management who negotiated with the dealer’s suppliers. Being employed in a structure of bureaucratic control, the buyer was much less easily convinced by material incentives alone. Footnote 59

The traditional discounters had been a nuisance to the traditional radio and television stores. However, because their lower prices were the result of a lack of service more than anything else, they had not endangered the idea of the list-price system. The new discounters were an actual threat. Over the next fifteen years, mass merchandisers, such as the Polk Brothers in Chicago or the stores Vim, Masters, and E. J. Korvette in New York City, not only succeeded in capturing almost a fifth of the market for black-and-white television sets and 9 percent for color sets, Footnote 60 but they also changed the overall intensity of price competition. For example, stores like Vim, Masters, and Korvette were the favored customers of Admiral’s New York City sales branch. Given the special price sheets, they could order television sets at lower prices and sell them at lower prices than other stores. Footnote 61 A columnist for the Electrical Merchandising wrote critically at the outset of the discounters’ surge: “If all retailers had paid the same prices, I doubt if the growth of discount houses would have been as rapid as it has been.” Footnote 62

The loss of market share in itself is not sufficient to explain the decline of the turkey economy. The success of mass merchandisers was accompanied by, and indeed interrelated with, a change in consumer behavior that can be seen as typical in light of product life-cycle theory. The second reason why the turkey economy ended was that television sets had themselves become less of a novelty and more of a price-sensitive product. Footnote 63 “TV has become a decidedly unglamorous area of a glamorous industry,” Footnote 64 Fortune magazine remarked in 1957.

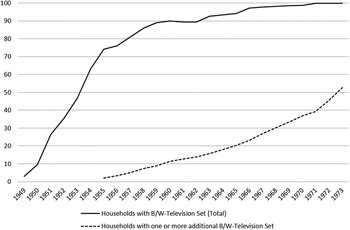

In the second half of the 1950s, the market for black-and-white sets was saturated and households started acquiring additional sets, as can be seen in Figure 1. Footnote 65 A drop in prices facilitated the rapid diffusion. In nominal terms, average retail prices dropped from $393 in 1948 to $299 in 1950, to $230 in 1955, and to $222 in 1960. In real terms, the development was more dramatic as household incomes increased, as did the average size of the sets and their quality. Taking the median family income as a proxy, an average American household in 1950 had to work about a month to purchase an average black-and-white TV set. By 1955, this figure had dropped to a little more than two weeks; and by 1960, it was about one and a half weeks. Footnote 66 Starting in 1956, more than half of all sales were replacements. Footnote 67 This shift was important because consumers who bought their second and third sets had become familiar with television’s technology and needed less advice. Mass merchandisers became a convenient alternative for consumers to trade off some (but not all) services for lower prices. Footnote 68

Figure 1 Diffusion of Black-and-White Television Sets in the United States, 1949–1973.

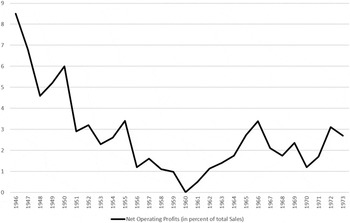

The pressure on consumer prices resulted in a dramatic decline in the net operating profit of traditional retailers. As Figure 2 Footnote 69 shows, average profits dropped from an abnormal high in the early years of television to a threatening low of less than 2 percent in the second half of the 1950s. This development was accompanied by a massive shake out of retailers. The number of radio and television stores had jumped from 7,231 in 1948 to almost 17,000 in 1958, but it fell to about 10,000 only five years later, echoing the decline of the specialty radio stores during the 1930s. Footnote 70

Figure 2 Net Operating Profits of U.S. Radio and Television Stores, 1946–1973.

The Federal Trade Commission’s investigation confirmed that competition at the retail level was rough. Although it was hard to believe in the case of television sets, some dealers stated that “small price differences at retail of as little as $.15, $.25 $.50 and $1.00 will switch a sale to another dealer.” Footnote 71 The keenness of competition put the traditional specialty stores in a quandary. Holding up the principle of stable list prices meant a potential loss of consumers. Starting in the mid-1950s, observers of the market noticed a decline in list pricing. Footnote 72 By the early 1960s, a list price was known as “the price nobody pays.” Footnote 73 An anonymous salesman who wrote a column for Electrical Merchandising Week expressed the same opinion, but somewhat more dramatically: “The average American would rather part with a vital organ before he pays list.” Footnote 74 The situation was more intense in metropolitan areas than in the countryside, and not every retailer was effected the same. Most consumers knew, though, that the competition had changed, and they started making extensive price comparisons as a basis for price negotiations. Footnote 75

Traditional radio and television stores were reluctantly drawn into a world of intensified price competition, and they lost interest in turkeys and whiskey because it more and more financially disadvantaged them to the point of bankruptcy. Confronted with price-conscious consumers and mass merchandisers grabbing for market shares, the existence of the turkey economy lost its rationale. As one retailer put it: “I could not use that [turkey and liquor] instead of profit.” Footnote 76 Like the television cartel, the turkey economy had relied on collective behavior and common understandings that had been facilitated, more or less, by a uniform retail structure. Its decline was a gradual process. Footnote 77 Once its stabilizing factors had disappeared, though, it was inevitable.

The decline of the turkey economy did not put an end to the franchise system. In many cases though franchises were granted even to dealers who barely fulfilled the criteria set by manufacturers and distributors. The generous distribution of franchises, sometimes called overfranchising, Footnote 78 and lax implementation of existing contracts, lessened the franchises’ ability to limit price competition and secure profits. Manufacturers such as Magnavox, which still put some effort into controlling the distribution channel of their products, became the minority. Footnote 79 Traditional retailers reacted by training their sales personnel to sell by quality instead of by price. Footnote 80 They also found intricate ways, such as designing code-based price tags, to prevent shoppers from bargaining and making price comparisons. Footnote 81 The measures may have slowed down structural change at the retail level, but they did not effectively stop the decline in the number radio and television stores. Some commentators, and later even economists, suggested that because the importance of advice and service was declining as the importance of price was increasing, radio and television stores lost their competitive edge. The history of television distribution, as Vincent LaFrance summarized his findings, “is a story of the growth of nontraditional outlets and decline of traditional dealers.” Footnote 82

Starting in the early 1960s, the breakthrough of color television changed that picture. If LaFrance had taken a long view on the development of radio and television stores, he would have seen a puzzling picture. By the mid-1960s, rather than declining, specialty stores were on the rise again. In 1977 their number set a new record at almost 25,000. The reason was that, similar to black-and-white television sets in its early years, color TV sets required a good amount of advice and service. It was also prestigious, which held price-conscious considerations in check. The importance of color television for the specialty dealers is confirmed by differences in market share with respect to black-and-white television sets. In 1975, the black-and-white market share of radio and television stores had dropped to around 40 percent, but it was nearly 60 percent for color television sets. Footnote 83

The introduction of color television increased the bargaining power of specialty stores, and franchises were protected more seriously. Distributors and retailers failing to comply were dropped. One manufacturer, Sylvania, even went to the Supreme Court to fend off allegations of antitrust violations after it had dropped one of its distributors in California. The distributor had violated the franchise agreement. After being dropped, however, it accused Sylvania of having acted “in restraint of trade,” as outlawed by the Sherman Act of 1890. The case became a landmark decision because it was considered a turning point in Supreme Court antitrust decisions. Footnote 84

The turkey economy, however, did not recover. List prices had lost their innocence. When they were still posted, it was mostly as a contrasting number to illustrate a bargain. Price stability, while still of some importance, was no longer a matter of stable mark-ups. “′Margins mean nothing. I have to pay expenses with dollars, not percent marks,” Footnote 85 one radio and television storeowner put it succinctly. There was also a change in organization. Most of the radio and television stores responsible for the increasing numbers since the 1960s were incorporated businesses, not proprietorships, and mid-sized businesses with yearly revenue of up to $2 million (in 1977) began to replace the smaller mom-and-pop stores of the 1950s. Both of these events suggest an increasing professionalization of accounting standards, which reduced the likelihood of material incentives; even travel vouchers had lost its popularity. Footnote 86

The End of the Television Cartel in West Germany

Just as with the turkey economy in the United States, the television cartel in West Germany proved to be an unstable and short-lived institution. The practice of resale-price maintenance ended rather abruptly in the early 1960s. Although it had a short comeback in the late 1960s, the cartel structure of the 1950s was never established again. The underlying reasons for the failure of price stability through means of price maintenance were similar to the ones that had led to the disappearance of material incentives in the United States.

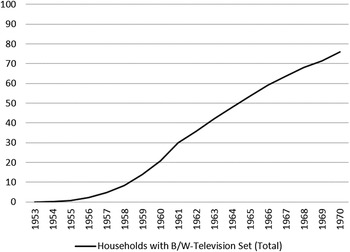

Compared to the United States, price statistics in the West German market for TV sets show much less of a downward slope. Until 1962, average prices were even rising because West German manufacturers had successively increased the average size of television sets to compensate for falling production prices and to avoid the risk of lower margins. The price of an average 53-centimeter set, however—the standard size between 1958 and 1961—fell from about DM 1.178 in 1954 to DM 858 in 1960. The price of a 59-centimeter set, which became the new standard, fell from DM 1.060 in 1961, to DM 782 in 1965, and to DM 576 in 1968. An average working-class household had to work less than two months to purchase a television set in 1956. In 1959, a TV cost the equivalent of about one and a half months’ income, and in 1964 the price fell below one month’s income. Footnote 87 Although this was a declining trend, it still meant that the purchase of a television set required a substantial sum of money. Compared to the United States, the diffusion of television sets was slow, as seen in Figure 3. Footnote 88

Figure 3 Diffusion of Black-and-White Television Sets in West Germany, 1953–1970.

By the late 1950s, retailers found themselves confronted with price-conscious consumers who demanded rebates. In 1959, for example, the city of Düsseldorf witnessed a price war when numerous dealers were forced to unilaterally (and illegally) reduce their final consumer prices. Footnote 89 Order was soon reestablished, but the television cartel remained conflict laden. By the early 1960s, it became obvious that the prices set by the manufacturers were too high to guarantee a steady demand to keep up with production. As television sets piled up in warehouses all over the country, the Federal Cartel Office became increasingly impatient. Retailers reacted with secret rebates. Consumers took a short cut; instead of buying their sets at the traditional radio and television store, many turned to a thriving “grey market” in which distributors sold directly to the consumers at prices well below the official ones. Like their American counterparts, West German retailers saw themselves in a quandary. It seemed the television cartel gave them a choice between infringement and lost sales. While individual reactions differed, agreement with resale-price maintenance plummeted. Retailers lost the belief that manufacturers and distributors were able to effectively control the distribution chain. As one dealer put it in a magazine commentary: “The fear of remaining stuck with inventories breaks down moral standards.” Footnote 90 The magazine’s estimation was that 15 percent to 40 percent of all market transactions had not been carried out according to the specifications of the television cartel. By 1962, the cartel was dissolved.

The end of the television cartel marked the beginning of a free market in the sense that, ideally, every actor along the value chain could pursue an autonomous pricing policy. However, there were two obstacles to this autonomy. First, many traditional retailers were reluctant to practice a pricing policy of their own because they saw themselves unable to do so. Instead, they oriented themselves to the list prices suggested by the manufacturer, giving rebates only when necessary. Second, manufacturers and distributors were confined in bargaining with individual buyers by the fact that price discrimination was seen as an illegitimate practice. The manufacturer Telefunken, for example, advised its sales branches to work with uniform discount rates because distributors and retailers had well-functioning, internal means of communication. Footnote 91 As one retailer expressed: “If I find out that my supplier grants better conditions to another customer, I get angry and shut down.” Footnote 92

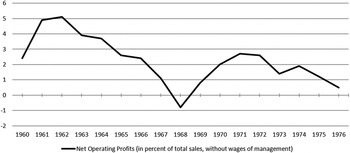

As Figure 4 Footnote 93 shows, for the radio and television stores, the “free market” for television sets proved less profitable than the television cartel. As (black-and-white) television sets entered the stage of maturity in the product life cycle, profits dropped. The number of stores, which had remained relatively stable during the cartel, fell from 7,016 to 6,503 between 1966 and 1968 alone. Approval rates of resale-price maintenance rose again, especially from the smaller stores. Footnote 94 Thanks to the introduction of color television starting in 1967, manufacturers were willing to listen to the needs of these stores. As the sales director of television manufacturer Deutsche Philips pointed out, the need for service and advice “almost inevitably” strengthened the position of the specialty stores. Footnote 95 While few West German manufacturers practiced resale-price maintenance after the end of the German television cartel, the number of models with binding prices shot up above 400 by 1970. Almost every manufacturer went back to resale-price maintenance for their color models. Some even included all or some of their black-and-white sets. Footnote 96

Figure 4 Net Operating Profits of West German Radio and Television Stores, 1960–1976.

From an organizational point of view, the second phase of resale-price maintenance differed considerably from the first one. Its introduction was neither a strategy that the industry had collectively agreed upon, nor was it substantiated by a rebate cartel. Instead, this time resale-price maintenance was the outcome of individual marketing strategies and bilateral negotiations. Distributors and retailers, however, paid a high price for the return to resale-price maintenance. The manufacturers were eager to recover research costs, so they set a high final sales price while simultaneously lowering trade margins. The high prices in the stores soon dampened consumer demand.

Given the stagnation of sales, West German manufacturers saw themselves confronted with a situation similar to the one American manufacturers had faced during the turkey economy: distributors and retailers became increasingly reluctant to take on new sets. Discriminating price reductions were problematic because, with resale-price maintenance in place, prices were part of a sales contract (a so-called Handelsrevers) that extended to all distributors and dealers. It was precisely at this point that special trade journals published reports about material incentives. In 1968, the Rundfunk-Fernseh-Großhandel reported that premiums such as travel vouchers existed more often than one would think. Footnote 97 Beginning in the 1970s, complaints about complimentary bottles of schnapps or wine, sweets, handkerchiefs, and folding bikes became widespread. Footnote 98 Although business practices changed, cultural attitudes remained the same. Manufacturers and distributors that gave away material incentives made sure to do so secretly. For example, sales representatives did not hand out written documentation of travel deals; instead, offers were made only verbally. Footnote 99 The Radio-Fernseh-Händler, another special trade journal, could only confirm “rumors about strange sales practices.” Footnote 100

From the consumers’ perspective, little had changed. Confronted with high prices in radio and television stores, on the one hand, and alternative opportunities, on the other, it did not take long before messages appeared of prices having been broken. While the so-called grey market still played a role, it was more firmly institutionalized dealers that acted as “price breakers.” Consumer markets or hypermarkets (Verbrauchermärkte), mostly on the western border of West Germany, led the way. They were able to circumvent the control mechanisms of the distribution chain by reimporting television sets. With consumer markets receiving considerable media coverage, department stores reacted by also discounting their prices. Given the chaotic circumstances, the Federal Cartel Office decided to revoke the validity of the price-maintenance contracts for the models affected. Footnote 101

Overall, the second decline of resale-price maintenance was not as sharp as the first one. The federal government decided to revise the German Law against Restraints of Competition by outlawing resale-price maintenance in 1973. Until that point, some manufacturers stuck to the practice at least for some of their models. However, material incentives did not stop immediately. The Handelsblatt reported in 1971 that a large proportion of sales revenue was still being generated by unfair business practices. Footnote 102 In 1972, the Rundfunk-Fernseh-Großhändler even spoke of a “system.” Footnote 103 Cay-Baron Brockdorff, of the manufacturer Loewe-Opta, expressed a widely held opinion when he told the journal: “I think we would be all more than happy if we could ban this ghost, which we have called for, as soon as possible.” Footnote 104 With the definite end of resale-price maintenance in West Germany, the practice of offering material incentives in the television set market retreated to an even more minor aspect of exchange relations than it had been before.

Conclusion

In the first few decades of television’s existence, the use of material incentives underwent drastic changes, and they differed greatly between West Germany and the United States. Both these changes and differences are hard to grasp from a purely monetary understanding of premiums or of financial incentives. Being embedded into different market systems, with specific distribution structures and common understandings of competition and pricing, the meaning of material incentives was tied to two different worlds.

The turkey economy in the United States placed material incentives at its center. The reason was that in a world with a uniform retail structure and with pricing conducted by manufacturers, it was an appropriate compromise between competition and control. Material incentives in the United States were used not only as a competitive tool, but also as a check on price competition. The German television cartel offered a different solution for stabilizing prices and maintaining profits. Characterized by the idea of collective agreements, the members of the cartel condemned deviant behavior of any kind. Given their hostile attitudes toward material incentives, the practice would have been destabilizing rather than stabilizing. In the West German market, material incentives were used as a competitive tool, but not as a check on price competition.

The decline of the turkey economy was the result of transformations in consumer behavior and a structural shift in retailing that resulted in a new kind of competition and pricing. Both factors were interdependent and eroded the basis on which the turkey economy had been built. Mass merchandisers were not responsive to material incentives, and the intense price competition at the retail level changed material incentives from being a stabilizing factor to being a financial threat to profits. Changes in retailing proved also important in the long run. When consumer prices stabilized during the rise of color television, dealers became less responsive to material incentives because the decline of list prices and the threat of mass merchandisers had taken away their key advantages.

The decline of the television cartel was more clear-cut because of its more formal dependence on collective agreements. The reasons, however, can be found in the same forces of markets maturing. It is telling that material incentives spread under the surface when the introduction of color television was backed by resale-price maintenance but not by the collective sanctioning of a television cartel. As seen with the turkey economy, resale-price maintenance was a specific way of channeling the competition of suppliers without affecting prices. From the point of view of West Germany’s long hostility toward material incentives, however, this was not the kind of narrative established. History mattered in the sense of providing interpretive frameworks that were not easily changed. Material incentives remained a strange, unwelcome strategy, so the system never solidified.

The meaning of material incentives, then, was derived from a twofold context. It was semantic as well as material, cultural as well as structural. Material incentives could spread even in a hostile cultural environment, and they could cease to exist even in a world in which they were generally appreciated. In the history of the market for television sets, the turkey economy marks a singular period in which both structural and cultural contexts worked in favor of handing out turkeys and whisky instead of price reductions. This finding is important because it suggests that when historians analyze markets, they need to make sure to place practices and institutions in the wider context of the historically specific markets in which they were embedded. A mere economic interpretation of material incentives as guiding some agent’s behavior by providing individual benefits is, therefore, a bar to gaining a historical understanding of markets.

Three further conclusions can be drawn from this discussion. First, the comparison of the market for television sets in West Germany and the United States suggests that consumer markets are not free in the sense that market actors pursue autonomous pricing and competitive strategies. One could argue that franchises were simply not markets (or hierarchies) evading the analytical economic tools of market analysis in the first place. Footnote 105 Although the difficulty of drawing on economic theory is obvious, there is no reason why the kinds or transactions described here should not be viewed in the broader context of changing market relationships. Economic sociologist Neil Fligstein has suggested to conceptualize markets as “stable worlds” with governance structures, rules of exchange, and conceptions of control rather than simply as competitive and efficiency enhancing institutions. Footnote 106 The case study presented here provides convincing evidence in this direction. It also underlines, however, the fragility of “stable worlds” in light of structural change and shifting consumer demand and its international differences.

In comparative perspective, first, the findings here not so much negate the established paradigm of a competitive dichotomy as they place it in a different, more substantiated light. The cartel-mindedness of West German businessmen is hard to miss, and indeed marks a distinction with respect to their American counterparts. Second, in comparing the turkey economy with the West German television cartel, it is possible to conclude that the use of material incentives did not reflect different cultural attitudes toward competition. Rather, the actual difference was in their specificity of solving the problem of competition. Footnote 107

Third, this case study highlights the importance of value chains for the analysis of market relations. Some business historians have already recognized the importance of distribution chains and of intermediaries such as retailers in shaping whole industries and market relations. Footnote 108 Overall, though, the perspective of autonomous actors in a closely connected economy remains underexplored. The case study in this article provides further evidence for the importance of seeing consumer markets as interconnected value chains and shows that singular, sector-based perspectives pose the risk of failing to fully account for business strategies and scope for action.

The turkey economy was specific in time as well as in space, but it was not any less genuine than the “stable worlds” established thereafter. If markets are to leave their shadowy role behind, historians will have to sharpen their tools and account for their historicity and their specificity. Differences lie just as well in times and places as they lie in different products. Even today, a few product markets, like those for pharmaceuticals, have some of the characteristics that the American market for television sets had during the 1950s. The uniform retail structure in the pharmaceuticals market, and a seeming avoidance of price competition, favors alternative competitive strategies on the part of manufacturers to giving dealers an incentive for handling and selling their product. The culture of markets in this sense evades grand narratives of national business cultures. Rather, it looks for the ways in which governance structures, rules of exchange, and conceptions of control were put in place along a more or less stable value chain.