In 1984, mountaineers Lou Whittaker, John Roskelley, and their teammates attempted to climb the north face of Everest. As they trekked, they carried $15,000 worth of equipment and clothing from JanSport, including red and yellow packs adorned with patches a few inches wide of a white cartoonish mountain that signaled the JanSport brand.Footnote 1 The partnership of an outdoor equipment manufacturer with adventurers might seem self-evident: Companies such as JanSport got a “public relations windfall” for their sponsorship—the logo captured in expedition photographs, the company name mentioned on television—and the athletes got free equipment.Footnote 2 In the second half of the twentieth century, this was a common pattern. Extreme athletes in the United States embarking on expeditions to climb the world’s tallest mountains or traverse remote regions on skis turned increasingly to commercial sources to support their ventures. By 1990, America’s outdoor industry—not governments, media, or private organizations—was the primary financier of large-scale expeditions led by Americans.Footnote 3 But logoed packs did not appear naturally on Mount Everest. This article shows how the relationship between athletes and corporate sponsors, rather than being inevitable or obvious, developed over decades from the 1950s to the end of the century.

The Everest expedition coincided with a much more well-known event in the history of sports sponsorship. 1984 was also the year of Los Angeles Olympics, recognized by scholars of marketing as a crucial turning point in the history of sponsorship because it was the first Olympics to make use of corporate sponsors such as American Express and Coca-Cola on a large scale, and because of that, only the second Olympics to make a profit.Footnote 4 Corporate spending on sponsorship did indeed boom after 1984. That year, sponsors spent $5.6 billion, while their spending increased to $25 billion by 2000, an almost fivefold increase in just sixteen years.Footnote 5 Yet this article rejects marketing scholars’ use of 1984 as a turning point, because those studies ignore important sponsorships earlier in the century.Footnote 6 The work of historians of science has been attentive to the funding streams for expeditions, arguing that modern expeditions have long been commercial enterprises that balanced the interests of the media, celebrities, and the nation-state.Footnote 7 But previous work has argued that even an “outstandingly successful expedition” was not necessarily a “platform for the outdoor brands which supplied it.”Footnote 8 In other words, the carefully sewn patches of the JanSport name in red letters with a white outline did not inevitably appear on the mountainside in 1984 and did not inevitably result in clear benefits for the company. The question, then, is how the relationship between companies and the events they sponsored evolved over time to—eventually—become platforms for brands.

While following the money has been important to scholars of expeditions and sports marketing, few have linked sponsorship to studies of where innovation comes from. Sponsorship history is also the story of the successes and failures of technological development by lead users, highly proficient performers who innovate for their own use.Footnote 9 The business literature on users who innovate often assumes that users operate outside company norms, sharing information freely because they do not intend to profit from it.Footnote 10 While cutting-edge designs in extreme adventure sports did indeed come from experimental users at the height of their respective sports, the history of sponsorship shows how companies sought to fit the insights of lead users into corporate structures and timelines. Examining lead users within the context of the sponsorship relationship points to the communication breakdowns that precluded innovation.

What is missing from assessments of sponsorship from the vantage point of sports marketing, history of expeditions, and history of innovation is an examination of the agreements that govern sponsorship. Contracts between companies and sponsored athletes are the key to understanding nuances of the evolving, reciprocal relationship. Both participants and funders experimented with ways to structure contracts to make sponsorship worthwhile. The outlay for an outdoor company in 1963 might have been in the thousands of dollars or simply goods in-kind in exchange for good public relations, an arrangement governed by personal letters. By the 1990s, companies sought detailed formal contracts to govern their investment of millions in cash in addition to product donations for highly publicized expeditions. The contracts that shaped the distribution of funds reflect a shift in how companies saw expeditions as useful to their marketing goals and searches for innovation.

This article draws primarily on three archives—two previously unexplored by historians—that offer an unprecedented chance to compare sponsorship relationships in a single industry across decades. First, the Gore Corporate Archive, which until recently has served internal business functions for the chemical manufacturer W. L. Gore & Associates and has not been available to visiting historians, includes material on how the corporation perceived and made use of sponsorship for the Trans-Antarctica Expedition of 1989–1990. Second, the Trans-Antarctica records at the Minnesota Historical Society have been sealed for twenty-five years and were opened for the first time when I accessed them in 2018. These records include expedition management details the public-facing Gore materials do not reveal. Finally, the Eddie Bauer Corporate Archive reveals what the company received in exchange for dozens of expedition sponsorships and internal business communication about the value of pursuing sponsorship. This kind of coverage—multiple companies and scores of contracts—enables assessments of the broad changes in the landscape of sponsorship in a way that looking at just one famous athlete or a larger company with more closed records would not.

Focusing a history of expeditions on sponsorship contracts rather than on sporting feats on the side of a mountain can help historians understand the capital behind sports. The business side of sports is as important as social and cultural analyses, because entrepreneurs and investors, alongside athletes, shaped the development of sports and sports products.Footnote 11 Popular work on the outdoor industry often focuses on histories of innovation by lead users who start niche lifestyle brands.Footnote 12 This story focuses instead on heavily capitalized manufacturers and retailers that dominated the industry by the 1970s. For business historians, sponsorship history bridges the gap between corporate public relations and advertising. Contemporary sports marketing scholars recognize that sponsorship is, in fact, marketing, but business historians have retained a focus on the public relations era of sponsorship to show how companies created general goodwill rather than looking at specific products companies hoped to promote.Footnote 13 Looking to corporate sponsorship over a longer period reveals how sports and corporations shifted their approach from PR to advertising, from building corporate soul to seeking out logo-plastered images for ad campaigns or field testing results from expert users. Finally, for scholars of innovation, this article shows the limits of the lead user concept within an industry often closely associated with it. In practice, systematizing lead user innovations rarely worked, as the sponsored athletes were notoriously unreliable when it came to actually giving equipment feedback.

The changing landscape of the business of expeditions ultimately reveals how the most long-lasting legacies of these extreme adventures happened far from the trail and much closer to company boardrooms, sponsorship managers’ offices, and retail stores where consumers learned to engage with the narratives companies and athletes had crafted together. The very notion that a JanSport jacket should have a visible logo or that a JanSport-sponsored climber would bother to pose for a photograph that shows off that logo during a climb are all relatively new phenomena. Many consumers now expect—indeed seek out—jackets emblazoned with particular brand logos, though few recognize the influence sponsored athletes have had on gear design and marketing. This article shows how businesses brought their logos to the top of Everest and to other extreme environments, and what that meant for sports, marketing, and consumers.

“Eddie Bauer, Expedition Outfitter,” 1950s–1970s

Eddie Bauer Inc. was a Pacific Northwest–based hunting and fishing manufacturer and retailer for decades before the company sought to evolve into “Eddie Bauer, Expedition Outfitter.” It had garnered national and international exposure as a supplier for the U.S. military during World War II and wanted to maintain a national rather than regional profile. To that end, as American companies increasingly appeared on mountaineering packing lists after World War II, Eddie Bauer began sponsoring international expeditions in the early 1950s, mostly by donating equipment in exchange for testimonials.Footnote 14 Vague contracts that allowed athletes or expedition teams to exert their will over how they would be represented—a textbook description of public relations, where the company did not fully control the message—governed its relationship with expedition teams. Athletes controlled the language and the release of images. A firsthand account of how equipment withstood extreme conditions was the most common way Eddie Bauer used sponsorship in catalog copy (Figure 1).Footnote 15 These accounts were especially useful because they appeared as the company’s eponymous founder—who had once personally tested many of the products—transitioned out of a leadership role.

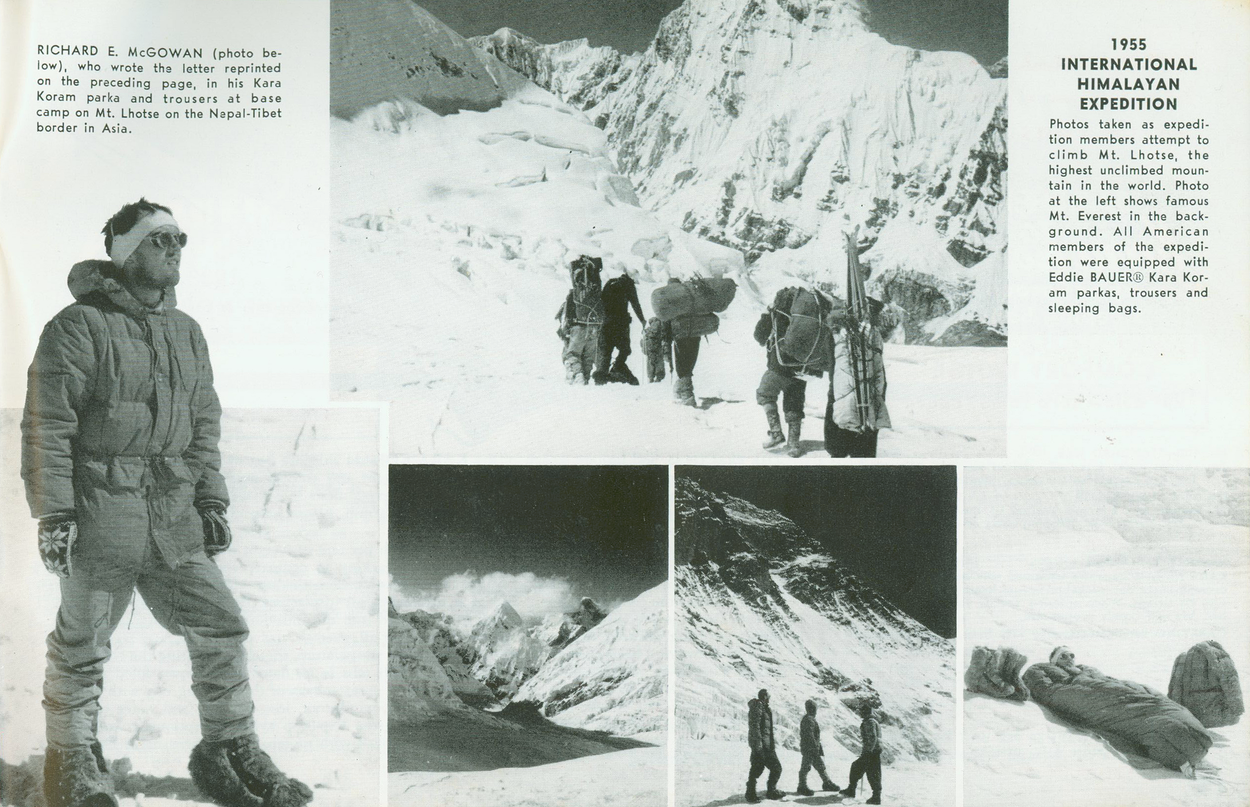

Figure 1 Eddie Bauer began sponsoring expeditions in the early 1950s. Company catalogs included images from the expeditions, like this one of climber Richard McGowan on Mount Lhotse in 1955 wearing an Eddie Bauer parka. The catalog also included a full-page testimonial, written by McGowan from base camp, attesting to the efficacy of the equipment.

Eddie Bauer catalog, 1955, EB.

In these years, athletes, not companies, drove the sponsorship relationship. Negotiations between William Niemi, Eddie Bauer’s partner in the firm, and climber Allen Steck, illuminate the vague contracts that undergirded the sponsorship relationship. On behalf of his California Himalayan Expedition team, Allen Steck wrote to Eddie Bauer to inquire about down jackets for a 1954 climb up Mount Makalu. After Eddie Bauer agreed to make specialized parkas at $10.00 per garment, Niemi asked how the expedition would “help us out as to advertising.” Importantly, Niemi did not require Steck’s help as “a stipulation to making the garments.” Indeed, he promised, “We will make them regardless.”Footnote 16 Steck responded that the company would have his team’s “full cooperation” in passing on “promotional material,” without specifying what that might look like.Footnote 17 In practice, catalogs ran expedition photographs accompanied by athlete endorsements.Footnote 18 Rather than writing copy, the company used letters written by the climber verbatim, as a way to suggest that the message came directly from the sponsored athlete.

How Eddie Bauer advertised its expedition sponsorship in the 1950s and 1960s shows its narrow understanding of how to use sponsorship for PR and a narrow understanding of its target market. At the most basic level, the company saw providing equipment or funds to expeditions as useful, because it shored up relationships with expert outdoorspeople who bought its gear and allowed it to boast of equipment tested in the field. The benefits that both athletes and sponsoring companies expected were governed by personal correspondence that served as a contract. One area rarely formalized by these contracts was any feedback from the users about equipment design. Companies such as Eddie Bauer did not expect athletes to contribute design insights that would trickle back down to ordinary consumers. Indeed, the requests of climbers like Charles Houston for modifications such as a specific diameter of jacket drawstrings seemed more like pesky details to be accommodated than the brilliant insight of a lead user to be exploited.Footnote 19 Companies likewise did not expect a broad audience for any material resulting from an expedition. Eddie Bauer was a specialty company, and the masses of Americans just beginning to camp and hike had little use for an expensive, expedition-weight sleeping bag suitable for Everest.

Eddie Bauer’s sponsorships coincided with a booming outdoor industry focused mostly on family tourism. After World War II, increased vacation time and car ownership helped fuel participation in outdoor activities in the United States.Footnote 20 Millions of Americans preferred pleasure drives and car camping to extreme mountaineering, but they nonetheless read about high achievers in sports magazines, which were in high circulation.Footnote 21 Though it might seem obvious from a twenty-first-century vantage point that outdoor companies would seek out casual recreationists to supplement their focus on extreme athletes, this was not a given when Eddie Bauer began sponsoring expeditions. The outdoor industry was a risky business. There were not that many participants in extreme sports, and most people bought from army surplus stores, not niche specialty stores.Footnote 22 Companies’ use of sponsorship to reach broader and less specialized markets tracks with important social changes: the increasing participation in outdoor sports and the increasing resonance of outdoor clothing and equipment in popular style. These broader changes help explain the evolution in sponsorship’s purpose and efficacy for companies.

One example of the uncertainty resulting from informal and vague sponsorship contracts is how companies made use of the photograph of climber Jim Whittaker standing triumphantly at the top of Everest. Like the long list of commercial sponsors for the 1963 American Everest Expedition, Eddie Bauer saw the expedition as a chance to promote the company name and to assess its products.Footnote 23 The image captured the day when Whittaker became the first American to stand on the world’s tallest peak. It shows Whittaker wearing a shiny red down jacket, puffy blue pants, and yellow knee-high boots. The National Geographic Society, the trip’s largest sponsor, had secured rights to all images from the expedition, so access to these snapshots for smaller sponsors like Eddie Bauer was uncertain. The expedition’s leader explained to an Eddie Bauer executive that the company’s image requests “must be cleared through expedition headquarters.”Footnote 24 Given that the photographs were the best way to highlight the role of Eddie Bauer equipment on the Everest climb, company executives were attentive to the conditions of use. The company relied on the letters from mountaineers to say what the photographs themselves could not: that the bright red, logo-less parka in question was an Eddie Bauer garment. Eddie Bauer used the Whittaker photograph in its catalog as the company sought to translate the expedition’s success into goodwill from customers who would never climb Everest but would be happy to buy a product proven there.

Private complaints from a Bauer competitor about that very photograph reflect the challenge of sponsorship relationships not governed by precise contracts. “How do we get a shot of a Gerry parka on the summit?” asked Gerry Cunningham, owner of Gerry Mountain Sports, an Eddie Bauer competitor in Colorado. In a letter to the expedition leader, Cunningham suggested that Whittaker had “slipped on his Bauer jacket for the picture,” intentionally removing a Gerry parka supplied to the expedition so it would not appear in any photographs. The accusation was without merit, as the Gerry parkas that Cunningham had donated arrived too late to be taken on the initial assaults up the peak. To Cunningham, however, it seemed as though the expedition members were deliberately sabotaging his company’s chance at good publicity by not producing an image that displayed the Gerry products.Footnote 25 The contracts with sponsoring companies had promised no specific photographs, however, and expedition leader Norman Dyhrenfurth made clear he resented the implication that his team had gone back on a promise. Dyhrenfurth wrote that the “thought that Big Jim [Whittaker] would have either the time or inclination to think about such matters while standing on the summit of the world, close to total exhaustion, seems rather ludicrous.”Footnote 26 Sponsors’ concerns about how their goods were represented in iconic photos could hardly be expected to be on the minds of elite athletes who were focused on reaching their goals, the expedition leader suggested.

Within a few years, however, sponsors’ concerns were precisely what athletes in similar positions needed to consider. Eddie Bauer executives were privy to the argument between Norman Dyhrenfurth and Gerry Cunningham about the Everest summit photograph because Dyhrenfurth forwarded the company the correspondence when negotiating another sponsorship contract in 1971. Kenneth Wherry, an Eddie Bauer marketing vice president, wanted to work out a clearer “mutual agreement” to avoid the “rash of unscrupulous and untrue advertising claims” that he had seen in the years after the 1963 expedition.Footnote 27 The lesson for companies like Eddie Bauer was to increase the formality of the relationship between commercial supporter and expedition team, so each party would know its particular obligations to the other. The company also saw firsthand increased interest in outdoor recreation in the 1960s and 1970s, influenced in part by press coverage of the 1963 Everest expedition.Footnote 28 In sponsorship agreements in the following decade, Eddie Bauer clarified its status as the exclusive supplier of down in order to guard against other outdoor companies’ advertising claims.Footnote 29 It began to ask for specific numbers of pictures and the rights to use them how it wanted.Footnote 30 By the early 1970s, Eddie Bauer, a national mainstream and main street retailer, would no longer issue parkas to climbers and simply hope for a good word about the product to the public based on a promise of “credit.” Instead, the company developed strategies for making sponsorship worthwhile beyond PR as it increased its cash and equipment outlay and sought to reach a mass market. The most important of these developments was clarifying how to systematize lead user insights.

“Business Partners,” 1970s–1980s

Outdoor equipment and clothing manufacturers flourished in the 1970s due to a growing interest in outdoor recreation, and sponsored, heavily publicized expeditions played a role. Companies sponsored numerous climbing expeditions and individual athletes, contributing to an increased commercialization of adventure sports, a proliferation of logos on Everest, and the new status of professional adventure athlete. Whereas in previous decades sponsorship had been characterized by informal personal relationships and a vague exchange of promises, by the 1970s companies like Eddie Bauer sought more detailed contracts to increase control over the expeditions. Eddie Bauer, like other regional outdoor clothing and equipment companies in the 1970s, was bought out during this time by a large corporation, General Mills, and this too shaped the corporate bent of the sponsorship relationship.Footnote 31 Rather than relying on inconsistent testimonials from expedition members, as companies had in the 1950s and 1960s, sponsoring companies began to require that athletes complete feedback forms to give input on tent or sleeping bag design. By the end of the 1970s, athletes and companies together had created a relationship of “business partners,” revolving around individual sponsored athletes whose celebrity would be good for advertising and whose expert insights would be good for design.Footnote 32 Companies only slowly began to consider sponsorship as a part of a broader marketing strategy, and began to invest cash in addition to the sponsorship itself, all in an effort to reach the booming population of outdoor recreationists. Overall, by the 1970s, companies were often run by professionally trained managers in search of a mass rather than specialized market and had more control in shaping the goals of expeditions and the agreements with the athletes they sponsored.

To make sponsorship worthwhile, as Eddie Bauer increased its cash and equipment outlay upfront, it delineated what it wanted in more specific terms. For the 1973 trip to Dhaulagiri, Eddie Bauer asked expedition members for regular communications, reports, and photographs that could later be used in companies advertisements.Footnote 33 The 1974 Peak Lenin contract negotiated between Kenneth Wherry of Eddie Bauer and Pete Schoening on behalf of the expedition members, specified that Eddie Bauer would provide 50 percent of the expedition cost, up to $25,000. In return, the expedition would grant the company the right to approve of other sponsors to ensure they would be “compatible with the Eddie Bauer goals.”Footnote 34 Schoening, the expedition leader, also agreed that expedition members would “advise Eddie Bauer on the performance of the equipment and generally provide council [sic] on equipment.”Footnote 35 In 1976, Eddie Bauer once again negotiated the status of exclusive supplier of down equipment and clothing for the Nanda Devi expedition. In this case, the company asked for a written critique of each product used and for the team to return much of the equipment after the trip so the company could study it. Each trip inspired Eddie Bauer executives to add new requirements to contracts for sponsorships to come, most of these revolving around getting feedback on gear modifications or trying out new products.Footnote 36

The tone of the letters exchanged between company employees and expedition members highlights how their relationship changed to focus more on advertising and innovation potential. In the 1950s and 1960s, company executives were deferential to the expedition equipment managers, hoping for favorable returns in the form of photographs and testimonials. By the mid-1970s, Eddie Bauer representatives took a more assertive approach. For the 1976 Nanda Devi climb in India, Eddie Bauer’s Ken Wherry insisted that in addition to returning the equipment, the climbers provide a “complete written critique of each product used” and furnish the company with at least eighty photographs of the training and expedition itself. Furthermore, Wherry explained, Eddie Bauer was “free to promote our involvement in whatever ways we deem appropriate.”Footnote 37 Rather than relying on the goodwill and the memory of expedition leaders, Wherry instead wrote out these clear expectations, which gave the company free rein to advertise its involvement.

At the core of these contracts was language about what field testing athletes would do for companies that loaned or gave them equipment. In earlier decades, the company’s request for feedback from the field was general. The company provided no prompting questions. Its requests therefore yielded sporadic impressions based on what stood out to particular athletes, such as “the red parkas were plenty warm, but too heavy and bulky for technical climbing” and “the fur around the [parka] hoods bothered most of us when it became wet and soggy.”Footnote 38 Eddie Bauer realized it could benefit from more targeted feedback, and drafted questions for later sponsored expeditions, such as “Does the synthetic multi-layered bottom in the sleeping bag maintain loft or flatten with frozen moisture through extended use?”Footnote 39 Though Eddie Bauer drafted ever-more-detailed questions, that did not guarantee the company would receive answers.

Athletes mostly failed to provide useful information.Footnote 40 The needs of lead users often did not extend beyond the expedition itself, while company executives sought feedback for longer-term innovations.Footnote 41 Months after one expedition, Eddie Bauer only had one team member’s equipment questionnaire, despite a contractual obligation for all team members to submit them.Footnote 42 John Roskelley, a DuPont- and Gore-sponsored climber, argued that it was difficult to combine the needs of testing with the greater challenges of being on the side of a mountain. He shared that “unless a company specifically asks for certain kinds of input,” climbers did not pay attention to details of design except in cases of failure. The physical effort of an expedition could “take all the energy the participants have.”Footnote 43 Another concern was that athletes did not respond usefully. Larry Pearcy, a marketing manager who worked for Kelty, explained that “many of the few suggestions we get are quite esoteric.” He suggested that many comments from athletes are not useful for products aimed at “the average consumer.”Footnote 44 An Eddie Bauer executive summed up the concern the company had with field testing this way: “Feedback from the mountains has generally been insufficient, incorrect, incapatible [sic] with production capeabilities [sic] and totally inconsistent.”Footnote 45 Lead users, in other words, did not always live up to their promises. Given all the problems of field testing, even as contracts became more specific about what athletes were required to do, why keep sponsoring if little useful testing data came from it?

The answer was marketing. Eddie Bauer, like other companies, publicly affirmed that field testing was a crucial factor in sponsorship decisions, because it was a central part of its marketing strategy. A DuPont spokesperson said that expeditions brought the company “feedback on our products as well as some publicity.”Footnote 46 The real purpose, though companies rarely stated it directly, was not to get climber John Roskelley’s expert feedback, but rather to highlight that Roskelley’s sleeping bag was “proved on Everest” and was now available for purchase.Footnote 47 Backpacker magazine ran many other advertisements that made similar claims. One declared that “Madden packs and clothing went to the top of 21,130-ft. Cholatse.”Footnote 48 One gear manufacturer, Wilderness Experience, used both expeditions and full-time professional testers for feedback. As the company’s president explained, “It’s good promotion to support expeditions, but ‘we get better hard data from our five pro[fessional tester]s than any fifty adventurers.’”Footnote 49 Wilderness Experience, like many other outdoor companies, supported dozens of expeditions, but it used those relationships to boost sales, not to generate useful feedback. It was worth it if an athlete could link the company name with Everest by carrying the pack or jacket with the company logo to the summit.

Until the 1970s, athletes could not rely consistently on outdoor companies for cash or free equipment, as they worked out the details of each sponsorship agreement on a per-expedition basis. Support was for teams, not an individual, and the amount of support companies furnished was low enough that no explorer could consider himself a professional climber or mountaineer—no one was reliant on sponsorship deals to support his career. They might have been experts, but no one was paying them to do their sport. They did not see themselves as partners in a business arrangement with sponsors. As sponsors recognized the need to invest more to promote their sponsorship, they realized that potential consumers connected with individual athletes with good stories.Footnote 50

Climber John Roskelley’s rise to fame partly as a spokesperson for DuPont’s synthetic insulation Quallofil is a case in point.Footnote 51 A DuPont sponsorship allowed Roskelley to do what he saw as his “real job” of climbing, but ironically the relationship required Roskelley to be more of a businessman to fulfill his obligations to his sponsor.Footnote 52 DuPont was no stranger to sponsorship. In the 1930s, the company had sponsored a radio program in an effort to combat a reputation as a “merchant of death” born out of World War I.Footnote 53 The work with Roskelley was different, however, because it focused on a particular DuPont technology, rather than the reputation of the company as a whole. Sponsorship pioneers like Roskelley and DuPont laid the groundwork for similar relationships in the years that followed. In 1986, Outside Business, an outdoor industry publication, named a few of the sponsored athletes who worked as business partners with sponsors. Just as DuPont relied on Roskelley, Kelty partnered with Rick Ridgeway, The North Face with Ned Gillette, JanSport with Lou Whittaker, Quabuag Rubber Company—which manufactured Vibram soles in the United States—with Jim Whittaker, and Patagonia with “a collection of leading-edge adventure veterans.”Footnote 54

By the 1980s, athletes and companies saw the benefits of a business relationship built on sponsorship, but the power in the relationship had shifted. For instance, in 1979 and 1980, Eddie Bauer underwrote multiple expeditions that it had designed and set the terms of itself—with lead user innovation at the forefront. Eddie Bauer even recruited athletes who would embark on the expedition.Footnote 55 For that expedition, the participants had thirty days to submit their assessments of gear, effectively writing the user feedback into the contract. They also agreed to supply photographs of each Bauer garment in use during the exploration. Even the exploration trip plans themselves had to be approved by Eddie Bauer before the company would transfer funds. Footnote 56

Sponsors were careful to protect their interests by carefully negotiating details like brand logo placement and by making specific advertising plans. This attention to how TV viewers or newspaper readers would encounter a brand name led to marketers to develop a new concept to help quantify the value of a sponsorship: brand impressions. While the impact of a sponsorship could never be certain, given that companies did not sponsor in isolation from other advertising, marketers suggested that measuring how often a potential consumer encountered the brand name was a good indicator of the success of a sponsorship deal. For DuPont’s sponsorship of adventurer Will Steger’s trip to the North Pole in 1985, for instance, the company promoted its sponsorship so the brand impression number would increase. For DuPont, that meant hosting press conferences, planning company logo appearances, and arranging for Steger to help market products.Footnote 57

The effort was successful: News coverage of the expedition appeared in at least 400 newspapers and in television reporting. DuPont estimated that coverage yielded 240 million brand impressions worth about $6.7 million.Footnote 58 Other companies were equally attentive to the possibility of reaching broad audiences through television. Because TV and movie footage was “the best payback” for a 1983 Everest expedition, an Eddie Bauer executive reasoned that “it is especially important that every Bauer item be clearly identified.”Footnote 59 In a follow-up to the promotional agreement Eddie Bauer signed with climber Chris Kopczynski, the company specified that the climber’s clothes should have “an expedition label large enough to clearly identify Eddie Bauer in any news coverage.”Footnote 60 Together with color brochures and press releases displayed in store windows and on clinic signs, Eddie Bauer executives hoped that the branded clothing items would increase consumers’ awareness of the link between an Everest climber and the company.

Despite the increasing formality of business relationships, companies were ambivalent about the ultimate goal of sponsorships. Was it public relations, advertising, or product innovation? The answers depended on who companies saw as an ideal market. Company executives wondered what exactly linking a brand to an extreme athlete or landscape would suggest to ordinary American consumers. Some companies argued sponsorship was worthwhile, because they were selling the allure of adventure and the exact clothing or equipment that that been tested in extreme conditions. For other companies, sponsorship was not worthwhile, because consumers did not need the same clothes as extreme athletes. Gear designers knew the majority of backpack or sleeping bag owners would never climb Everest. The sales manager for Southern California outdoor retailer Adventure 16 suggested that the Everest-tested equipment might actually turn their customers away. “About 95 percent of our business is from weekend consumers going out to have a good time,” he explained, and an advertisement showing “some guy with a backpack on Mount Everest, freezing his ass,” might make that casual participant wary.Footnote 61 While it is difficult to know how consumers responded to these ads, a 1985 letter to the editor in Backpacker magazine offers some insight: A reader called the Everest field tests “meaningless” for ordinary consumers, given that expeditions get new equipment and use it only for a few months, as opposed to regular consumers who used equipment for years.Footnote 62 Judging from the popularity of the products with ordinary readers and the increase in sponsorships overall, however, most consumers and companies did not agree.

Though Eddie Bauer stepped away from sponsorship by the end of the 1980s in recognition of its mainstream and less expedition-oriented market, overall sponsoring increased in the 1980s, reflecting the broad popularity of sponsorship as a marketing tool across industries.Footnote 63 One marketer directly tied the increase in funding requests to Steger, Roskelley, and “other explorers embarking on frigid extravaganzas.” In 1987, his company received requests nearly every workday from “people who want to hang glide off Everest” or “walk to the North Pole.”Footnote 64 The scale of the requests was so great that some companies had to build new structures to support the processing of requests. Some created sponsorship committees to assess requests. Others created formal application processes for named grants that athletes could apply to with a uniform set of documents. Still others turned to sponsorship marketing managers to help manage the relationship with potential sponsees.Footnote 65 While the impact of sponsorship on sales was unclear, the continuing expansion of sponsorship programs suggests that companies found the visibility and press associated with sponsorship valuable.

In 1989, when Will Steger sought support for another grand plan—this time a traverse of Antarctica—companies’ marketing managers understood how to communicate the value of sponsorship to their bosses. They had new ideas for leveraging sponsorship, and with those tactics, it would matter very little that their target customers would never ski across Antarctica.

Athletes as “Advertising Boards,” 1990s

In 1989, W. L. Gore & Associates became a multimillion-dollar investor in the Trans-Antarctica Expedition with a carefully negotiated and precise sponsorship contract. The expedition was one of many large-scale expeditions financed by the outdoor industry in the late 1980s and early 1990s. L.L. Bean, the Maine-based catalog retailer, sponsored the Mount Everest Earth Day 1990 International Peace Climb.Footnote 66 JanSport had tripled its sponsorship budget the year before to finance a climb up Kangchenjunga. Sponsorship as a form of marketing had come of age. Overall, in 1989, nearly four thousand companies across many industries spent $2.1 billion on sponsorships.Footnote 67 The biggest spenders on sports events were the beer industry and tobacco companies. In 1990, for instance, the tobacco industry spent $125 million on events such as the Virginia Slims tennis tournament and the Camel GT Series car races.Footnote 68 DuPont and Gore, with their sponsorship of Steger and Roskelley, were comparably big players in the expedition world. According to an analyst of sponsorship relationships in the 1980s, outdoor companies were “big players” in expedition sponsorship because “it [made] sense. It’s their business.”Footnote 69 But it only “made sense” because of decades of work to establish the boundaries of the relationship and strategies for making the sponsorship profitable.

How chemical manufacturer Gore worked to make the sponsorship of the Trans-Antarctica Expedition profitable shows three important shifts. First, the company’s relationship with the expedition shows the evolution from the more passive and vague sponsorship days of the midcentury to the notion that sponsored athletes should be business partners. Second, Gore, like other sponsoring companies, recognized it had to spend far more money than the deal itself to reap the benefits of sponsorship. The most important products to come out of the sponsorship were not the eye-catching neon snow suits designed by The North Face and branded with the large logo of Gore-Tex manufacturer Gore, but rather the dog toys and school lunch boxes that represented a new era of merchandising. Finally, the influence of a chemical manufacturer, founded by a former DuPont scientist and with only a tiny portion of its overall business in the outdoor market, reflects radical shifts in the technologies and corporations involved in the outdoors by the end of the twentieth century. Gore joined DuPont, Celanese, 3M, and other chemical companies in manufacturing ingredient products for insulation or waterproofing in outdoor goods like sleeping bags and tents. The chemical compound ePTFE that became known as Gore-Tex also had applications in the space, industrial, and medical fields, and Gore’s research, development, and marketing budget outpaced even General Mills–owned Eddie Bauer and the privately owned L.L. Bean.

In the outdoor world, consumers knew W. L. Gore & Associates because of the company’s synthetic laminate, Gore-Tex. This waterproof, breathable material had been among the most recognizable technological innovations in the outdoor industry since it entered the consumer market in 1976. Gore had dabbled in sponsorship before, backing cross-country walker Rob Sweetgall and using climber John Roskelley to promote Gore-Tex in store appearances and in short training videos.Footnote 70 But its connection to the Trans-Antarctica Expedition was not guaranteed. By the late 1980s, commercial sponsors interested in pursuing adventure sponsorships worried that there was not much left of the world to explore. “There’s been a fast disappearance of potentially important discoveries,” recounted the president of Rolex Watch U.S.A., a longtime expedition sponsor. “There’s only one Everest. There’s only one circumnavigation of the globe. There’s only one deepest cave network.”Footnote 71 Companies like Rolex, DuPont, and Gore, therefore, remained reliant on new narratives of firsts by explorers.Footnote 72

The trip supposedly aimed to call attention to the expiring 1959 treaty that had designated Antarctica a nonmilitary space not claimed by any nation.Footnote 73 Steger was also concerned about global warming and its effect on the future of the continent.Footnote 74 These political aims, alongside the presentation of the traverse as an adventuring “first,” helped Steger and his French partner in adventure, Jean-Louis Etienne, secure millions of dollars in support. After a few years of fundraising, Steger and Etienne assembled an international team that included men from the U.S.S.R., Great Britain, Japan, and China.

Jack Dougherty was the expedition’s champion at Gore. His activities show how marketing, a new licensing and co-branding arrangement with outdoor manufacturers, and personal interest shaped the sponsorship deal far more than the possibility of field testing. Dougherty thought that the expedition was of international importance, valuable to the company, and most of all, that images of dogs pulling sleds would attract new customers.Footnote 75 He was also intrigued about the possibility of connecting a new marketing campaign at Gore with the expedition. Dougherty’s decision to sponsor the expedition related to marketing plans already in motion. Whereas Gore had previously guaranteed only the Gore-Tex membrane, in 1990 it planned to feature the trademark on clothing produced with Gore-Tex and would offer a new guarantee: “Gore-Tex Outerwear, Guaranteed to Keep You Dry.”Footnote 76 Effectively, Gore licensed the right to use its logo on a garment to a manufacturer like The North Face in exchange for more control in the production process.Footnote 77 For Jack Dougherty and his team, a major sponsorship would offer publicity about the new guarantee and co-branding relationship, and further proof of Gore-Tex’s performance in extreme conditions, at just the right time. As a Gore spokesperson explained, “What better testimony can there be to the warmth and comfort of the Gore-Tex fabric… than to dress men and dogs in it as they travel 4,000 miles across Antarctica.”Footnote 78 Dougherty saw the expedition as “focal point of our 1989–1990 marketing program at Gore. It is a return to our heritage, our functional roots, taken to a huge audience.”Footnote 79 Dougherty did not simply rely on old strategies for marketing the sponsorship. Instead, he helped Gore leverage the sponsorship relationship in a new way.

Dougherty’s plan for marketing the sponsorship evolved over many meetings with Steger and the expedition support team, which brought carefully organized packets that introduced the team’s mission, its scientific and social goals, and the opportunities it had for sponsors to promote their products. The expedition promised sponsors would benefit from “the essential association with a spectacular international event” and access to “a unique testing opportunity” both during the training expedition in Greenland in 1988 and during the Antarctica event itself.Footnote 80 The fact that Steger hired an expedition executive director, Cathy de Moll, and had a support team for these sponsorship requests shows how far explorers’ individual fundraising had evolved into a business negotiation. Steger essentially needed someone to handle the business, because so much work happened far removed from the ski trail. De Moll was the staff person at the expedition responsible for the sponsorship contracts with Gore and DuPont.Footnote 81 She received faxes from Target marketers about what products bearing the Will Steger label would grace the company’s shelves.Footnote 82 She found spaces for meetings to discuss how sponsors’ “active involvement” would increase the companys’ visibility.Footnote 83 She shared estimates that sponsors and licensors were spending between $50 and $60 million “on promotion of the expedition.”Footnote 84 Together, de Moll and her team helped suggest pathways for promotion for the sponsoring partners.

Most sponsors saw the expedition as a marketable product that would help them sell jackets, lunch boxes, or bags of dog food. After negotiations with Steger and de Moll, Dougherty agreed that Gore would donate $2 million as well as equipment for the participants and sled dogs.Footnote 85 DuPont, Steger’s primary sponsor for his 1985 trip to the North Pole, added $250,000 and an agreement to work with Gore on equipment and clothing.Footnote 86 Other sponsors included Hill’s Pet Products, which hoped to sell dog food proven to fuel huskies at the South Pole, and Target, which had plans to license the expedition name and paste it on “thermoses, crayons, [and] lunch boxes.”Footnote 87 From Gore’s perspective, this expedition was “unlike any other” that the company had sponsored, because it was “highly commercial and will be seen by upwards of one billion consumers all over the world—not just climbing enthusiasts.”Footnote 88 This deal was the marker of a new era of sponsorship, in which the money spent on promotion far exceeded cash and donations in-kind to the athletes themselves. This also shows a change in what products ultimately came from the sponsorship. It was not only the specific jacket style that Steger wore, but also more mundane products like headbands branded with the sponsors’ and expedition’s names.

Gore’s contract with the expedition did not simply appear because it was a manufacturer that sold extreme equipment. Instead the contract reflected decades of evolving practice about managing the sponsor–athlete relationship. It asked more of the athletes than contracts had in previous decades. The $2 million in financial support garnered Gore the title of “lead sponsor” and the position as the exclusive supplier of “breathable, waterproof, windproofing material.” The sponsorship contract detailed the precise positioning of the brand name on expedition wear: on the front and back of the outerwear and on the back of the sled, with the Gore-Tex logo included on dog clothing. Gore got three “free” appearances from Steger and Etienne, along with a commitment from all team members that they would not endorse a competitor through the end of 1991. The team members also promised written testimonials about the Gore-Tex equipment. With an eye to the consumers who would follow this adventure, the sponsorship contract also stipulated that Gore had an option on an “exclusive dog toy” and the “approval of license for authentic expedition clothing.” It was in these final descriptions of licensed products that Gore anticipated making most of its money. To leverage its investment, Gore also hired a Philadelphia-based publicity agency and committed to a multimillion-dollar promotional budget.Footnote 89

The deal between Gore and the Trans-Antarctica Expedition further reflected the evolution in the promotional work companies planned. The amount sponsoring companies spent promoting their sponsorships, especially through merchandising, far exceeded the advertising budgets of the expedition and the cost of the sponsorships themselves. When Jack Dougherty committed $2 million to the Steger-Etienne expedition, he recognized the need to manage the marketing himself, rather than simply relying on the media traffic generated by the explorers. The company planned tie-ins and media coverage to get the most out of the investment. For the first time, Gore paid for television ads that ran when sponsor ABC gave the expedition coverage. Gore hired a jazz musician, Grover Washington Jr., who promptly “dedicated his 1989 national tour to the trip to the South Pole.”Footnote 90 Gore set up a bus that traveled to schools to visit children; the classroom entourage included a version of the Gore suit for children to try on, and popular visitor Zipper the sled dog.Footnote 91 Gore also committed to print advertising for consumers and in the trade press, special promotional events, and coordination with retail promotions at Target and Dayton’s department stores.Footnote 92 There was no waiting and hoping for positive responses from athletes. By the end of the expedition, expedition manager de Moll estimated that when she tried “to think corporate” about all the money “spent in whirling concentric circles” around the expedition itself, it was likely around $100 million.Footnote 93

Expedition members expressed concern about how the visual placement of sponsor logos would change the meaning of the journey. Expedition member Etienne voiced his concern with: “We’re not advertising boards. We don’t want to look like race cars.”Footnote 94 His concern echoed the idea from the 1963 American Everest expedition that climbers were too focused to consider the promotion needs of particular brands. The team nonetheless later acquiesced to the prominent placement of UAP—a French insurance agency and the other lead sponsor—on the chest, with the Gore-Tex brand stitched on the other side of the garment. For some athletes, wearing a brand name represented the culmination of fears of crass commercialism seeping into what had been, at least to some, an arena of pure sport. As historian Thomas Barcham recounts, mountaineers Ken Wilson and Mike Pearson worried in 1971 “that the pervasive aura of commercialism might one day lead to climbers being required to display the manufacturer’s name prominently on the equipment they are using.”Footnote 95 By 1990, this no longer seemed like much of a problem, not with the millions that UAP and Gore provided in support.

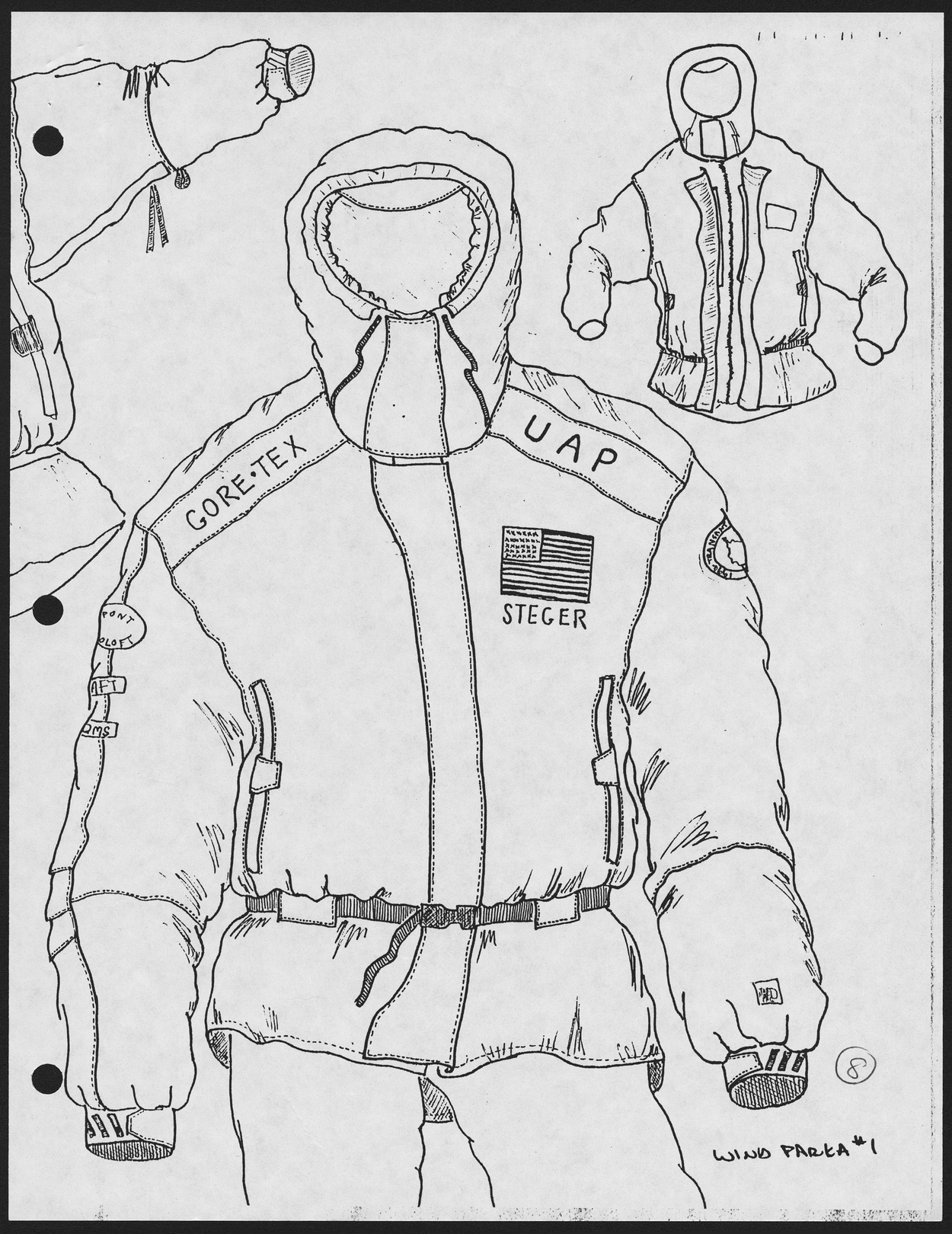

The equipment that Etienne, Steger, and their teammates wore was of particular interest to sponsors, because it would be filmed and photographed for broadcast worldwide.Footnote 96 For Gore, which provided the waterproof, breathable laminate, DuPont, which provided the Quallofil, Thermoloft, and Thermolite insulation, and The North Face, which provided the design and manufacturing expertise, the clothing and equipment mattered because it would get international coverage and testing in extreme conditions.Footnote 97 To the managers of the sponsorship relationship at Gore, the “most important aspect of visibility [was] the design and coloring of the garments and equipment. It must shout out TNF and GORE-TEX.”Footnote 98 Gore had specifically solicited The North Face’s help in manufacturing the garments, because Gore saw The North Face, a new licensee, as a crucial partner in promoting the “Guaranteed to Keep You Dry” tagline.Footnote 99 The logos in particular were the subject of much negotiation (Figure 2). Another lead sponsor, UAP, for instance, wanted the suits to have a logo high up on the chest, so the company name would appear in photographs in newspapers and magazines around the world. These companies’ negotiations proved useful, as newspapers articles covered the precise details of the garment design and logo placement.Footnote 100

Figure 2 The North Face worked on the design of the expedition’s clothing in consultation with DuPont, Gore, and other sponsors. This drawing of the Wind Parka suggests that initial design proposals carefully considered how to integrate brand names into the design. The exact size of the lettering for the final garments was determined by contracts that stipulated where and precisely how big the brand names would be.

14,418 Polar Expedition Promotional Materials, The North Face Clothing Equipment 2, box 4, TAE.

While the size of logos mattered most for public coverage of the expedition, the clothing design collaborations also reflected the more ambivalent relationship Gore had with lead user innovation and field testing. To design the expedition snow suits, Steger worked alongside Gore, DuPont, and The North Face, eventually going through nearly thirty design changes over many months to create an appropriate outfit.Footnote 101 To outdoor manufacturers, it seemed that the North Face gear made with Gore-Tex, designed “to withstand the rigors on Antarctica,” would be of great interest to consumers. “The consumer can buy next fall exactly what they see explorers wearing on T.V.,” wrote Jack Dougherty of Gore. These new customers, Dougherty assumed, would seek out outdoor clothing not just because it was well-designed, but also because “authentic, rugged gear” was “in.”Footnote 102 And yet this description of consumer purchases does not fully capture the equipment: Steger’s activity was so niche, his input so specific, that ordinary consumers had little use for the snow suits that it took months to design. The North Face ended up selling not an exact replica of the Steger outfit, but rather a commercial version, uninsulated (Figure 3).Footnote 103 Subsequent advertising referenced the specially designed equipment, but the actual insights and specifications of the expert in the field were less valuable to sponsoring companies than the logo placement.

Figure 3 Jack Dougherty of W. L. Gore & Associates was excited about the sponsorship relationship his company developed with the expedition because of the potential for selling merchandise related to the journey. “The consumer can buy next fall exactly what they see explorers wearing on T.V.,” he exclaimed before the expedition even began. The advertisement shows the “The North Face Official Antarctica Expedition Parka” for sale through outdoor retailer Eastern Mountain Sports, exactly as Dougherty had envisioned.

14,418 Polar Expedition Promotional Material Gore Tex 1, box 4, TAE.

One plan sponsoring companies made was to track the effect of their sponsorship relationships and advertising on the consuming public.Footnote 104 The results did not suggest a clear, measurable benefit of sponsorship. Instead, they showed that sponsorship had little to no impact on consumers’ knowledge of brands like Gore-Tex and DuPont’s Quallofil. Gore paid for a market research study from the Gallup Organization in 1989. Of the 1,007 respondents, only 10 percent of adults were aware of Gore-Tex as a sponsor of the expedition.Footnote 105 The DuPont Fiberfill department’s marketing research told a similar story. Respondents were most aware of ABC as an expedition sponsor, because television was “the main source of awareness” for most of them. Overall, “sponsors of the expedition receive little credit from the public,” with Gore known by 12 percent of responders, Kodak by 12 percent, Target by 10 percent, and DuPont by 8 percent. The DuPont poll showed that “recognition for most brands of insulated clothing and sleeping bags … was not significantly impacted over the last year.”Footnote 106 In other words, both the Gore and DuPont surveys suggested that the hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars invested in the expedition did not lead to a notable increase in consumer awareness.

Despite differing assessments of the usefulness and effectiveness of sponsorships, many companies continued to pursue those relationships, because they were personally compelling to company CEOs or marketing managers. When decision makers at companies felt like a sponsorship relationship made their work fulfilling, they often supported donating funds to athletes regardless of the business sense of the endeavor. Dog-lover Jack Dougherty at Gore is one good example. Expedition manager de Moll later recalled how Dougherty was personally invested in making the sponsorship relationship worthwhile. Similarly, Vieve Gore, whose late husband had founded W. L. Gore & Associates, was enthusiastic about the value of her company’s sponsorship, more because of the relationships that came with it, than because it was a measurable marketing success. Gore was feted at the Explorer’s Club for her sponsorship of the expedition and received personal thanks from members of the expedition; these moments of connection helped Vieve Gore feel part of the project beyond the financial and marketing benefits to her company. How decision makers like Jack Dougherty or Vieve Gore felt about an expedition could make a sponsorship possible, regardless of the financial reasoning behind pursuing such a project.

One final reason why companies pursued sponsorships even when quantitative evidence suggested it had little impact on their profits was the way that famous athletes might speak out on behalf of company’s beleaguered reputations. The collateral benefits of Steger speaking out on behalf of DuPont when the press questioned the corporation’s effect on the environment as a producer of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) was incalculable. There was a parallel between outdoor companies and cigarette companies who attempted to create goodwill through sports sponsorship.Footnote 107 Companies could draw the focus to consumer goods and adventure and away from the role that chemicals in those products had in contributing to global warming and the ozone hole in particular. Sponsoring meant funding someone who might then voluntarily defend the company when these charges came up.

Steger was (and is) a dedicated climate activist. One of his original goals of the 1989–1990 trip was to call attention to environmental degradation. And yet he also consistently offered a public defense of DuPont’s role as a producer of CFCs as a result of the sponsorship relationship. The irony of having DuPont as sponsor and top producer of CFCs—about which the expedition was trying to raise awareness—was not lost on Steger. But he believed that the financial support these companies offered committed him to speaking publicly. He spoke about how the company attempted to do no harm, and argued that DuPont was working to phase out CFCs in favor of alternatives that did not damage the ozone layer.Footnote 108 In press interviews, Steger suggested that individuals, rather than DuPont itself, should be responsible for their use of chemicals in day-to-day life. “‘It’s up to each individual—including the one who flushes chemicals down the toilet. Everybody has to look at what they are doing and be responsible. DuPont is aware of it, and they’re working on the problem,” explained Steger. For DuPont, the Antarctica expedition was an investment in getting a public figure to speak out for their greening efforts as much as it was a promotional vehicle for Fiberfill synthetic insulation.Footnote 109 At stake in the sponsorship arrangement was not just the changing nature of extreme adventure but also a shift in the conversation about the impact that companies had on the environment on a global scale.

By the mid-1990s, sponsors and sponsees came to their relationships with similar expectations about how their mutual business interests would develop. Steger took his role as business partner very seriously, and—just as his contract specified—participated in the equipment debriefings with designers and technicians at Gore.Footnote 110 Both the company and the adventurer recognized that the most important objects to come out of sponsorship deals were not snow suits custom-designed to an expert explorer’s specifications, but rather plush dog toys, lunch boxes, or T-shirts. For a few consumers, that was a reason to be cynical. One New York Times letter to the editor in 1989 argued that Steger’s rising star would simply be used by slick PR men to sell “dog food, freeze-dried soup and the latest in wash-it-yourself parkas.”Footnote 111 The less cynical responded that men like Steger would cross Antarctica “no matter what.” That corporate sponsors paid for the expeditions was “more a commentary on the way the world turns today.”Footnote 112 Both boosters and detractors of the Steger expedition recognized that sport could not be separated from commercialism, because it was corporations that helped shape the scale and scope of the adventures these athletes embarked on.

“The Animating Force of Exploration in Our Age: Gear”

The Trans-Antarctica Expedition was one of many large-scale expeditions that helped solidify sponsorship as a core component of outdoor adventure sports. By the mid-1990s there was a “surge in corporate sponsorship of expeditions” that mirrored a broader expansion of sponsorship as a marketing tool.Footnote 113 Americans consumed information—and merchandise—related to expeditions with longing and excitement. While companies spent $10 million on expedition sponsorships in 1986, by 1993 that number had increased to $200 million.Footnote 114 This reflected an increased number of sponsor-backed expeditions overall—more than one thousand in 1997.Footnote 115 One journalist called the 1990s the “exploromercial” era, highlighting the commercialization of extreme athletes’ experiences for everyday consumption.Footnote 116 Ultimately, toting logos from the Disney Channel, Hershey’s, or Novartis up Mount Everest or to the North or South Pole to display in a photograph rendered exploration a commercial made for print advertisement and television (Figure 4).Footnote 117 No potential image of a branded jacket going up to Everest is left to chance; instead, sponsorship is part of a clear, planned marketing campaign.

Figure 4 The performance of DuPont’s synthetic insulation fibers in extreme conditions was important, but the company also paid careful attention to how its brand name would be represented in photographs. The Trans-Antarctica Expedition team carried sleeping bags, jackets, and banners that sported DuPont product logos, highlighting how this journey of exploration was also designed as an advertisement for consumers.

“Across a Frozen Desert,” Du Pont Magazine, 85, no. 1 (1991), Hagley ID 1991_85_01, Du Pont Magazine Collection, Hagley Museum and Library.

Sponsorship remains a symbiotic relationship, but outdoor gear manufacturers and chemical companies increasingly have the upper hand. In the twenty-first century, they offer less to more athletes while still asking for marketable images and product input. Companies learned from the structured lead user relationships via sponsorship throughout the second half of the twentieth century, eventually finding low-cost ways to implement regular expert feedback about design as a part of both their marketing and R&D. This relationship does shape sports equipment innovation, but not as much as previous stories of lead users suggest. Companies such as Gore and Patagonia developed relationships with individual gear testers and promoters—often called gear “ambassadors”—akin to the relationship John Roskelley developed with DuPont in the 1980s.Footnote 118 While the nature of these relationships vary from company to company, few involve cash donations of hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars, as did the biggest expeditions in the second half of the twentieth century. Instead, contracting already-successful skiers, climbers, and other athletes as gear ambassadors allowed these outdoor companies to provide equipment and exposure but little cash.Footnote 119 In return, they got brand-loyal athletes and their active social media platforms, and when all went well, feedback from lead users. Expeditions vary wildly in size and the amount of support they garner, and ultimately it is sponsors’ involvement that determines how ambitious an athlete can be. The uneven power of the corporate sponsor is evident when sponsors readily drop athletes who act in ways at odds with corporate values.Footnote 120

There is an institutionalized expectation that acquiring a sponsor is a prerequisite for becoming a professional outdoor athlete.Footnote 121 Athletes are more business-savvy but also ambivalent about the way this engagement with the marketplace appears. One athlete had a sponsor that specifically sought photographs that “get the logo in” while at the same time appearing “authentic.” He recalled feeling “quite awkward about that” because it “looks daft” to pose in an action shot with a company logo visible on a chest pocket.Footnote 122 But he did it. Unlike Jim Whittaker on Everest in 1963, with no logo on his jacket and no thought of pleasing his sponsors, athletes of the twenty-first century know they are advertising boards. Logos on their jackets help fuel the sponsorship funds they seek.

While some athletes and journalists expressed a clear distaste for the era of commercial sponsorship, the outdoor industry continued to invest in sponsorship because consumers responded. Unlike in the middle of the twentieth century, sponsors’ attention has moved to consumers who might be casual climbers or hikers, but who are attracted to “the fantasy of a mountain experience” as much as mountain experience itself.Footnote 123 At the core of the increase in sponsorship over the last seventy years, then, are the jackets, sleeping bags, and stuffed animals that Americans continue to buy. Gear, especially gear for the average consumer, was the “animating force of exploration in our age.”Footnote 124 It was what explorers and everyday consumers alike read about, obsessed over, tested, acquired, and discussed. The ultimate destination for an everyday fan of Everest climbers and continent-crossers was an outdoor equipment store. It was there that consumers, who knew they would not climb Everest, embraced goods that had been tested or photographed on the world’s tallest mountain.