Introduction

The aim of this article is to analyze the transfers of tacit knowledge between countries and continents. Using a case study from the shipbuilding industry—the establishment of Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI), the first internationally competitive shipyard in South Korea—we show the important role of personnel sent abroad. Around 1970 the market for new ships was dominated by Japan and European countries, and the tonnage exported from South Korea was negligible. Fifteen years later, South Korea was the world’s largest shipbuilding nation, and HHI the leading shipbuilder. How did South Korean shipyards learn the tricks of the trade so rapidly?

The shift and spread of manufacturing production to and within Asia has been one of the most important developments in the world economy since World War II. Much of the debate about the basis for “the East Asian miracles” has focused on the relative importance of productivity and factor accumulation, as well as the role of industrial policy. The question of how the technological gap was closed has received less attention.Footnote 1

Japan and, subsequently, the East Asian “tigers” and China have managed to gain substantial market shares within several manufacturing industry segments: textiles, steel, consumer electronics, and automotive products. However, the first major industry in which the East Asian countries became globally “dominant”—with more than half of the world market—was shipbuilding. This was originally a Japanese, not a “pan-Asian,” endeavor; shipbuilding increased rapidly in Japan in the first postwar decades, and in 1956 the country replaced the United Kingdom as the leading nation in terms of tonnage launched. The country then steadily increased its market share and by 1975 had amassed a 50 percent share of world shipbuilding completions.Footnote 2 Japan’s only serious competitors were South Korea from the 1980s and China after 1990.

Following the oil price hikes of 1973–1974 and the consequent shipping crises of the mid-1970s, the demand for large crude oil tankers temporarily collapsed. As a result, over the next ten years many European yards closed and high-volume shipbuilding practically disappeared from Europe. In 1970 British shipyards produced almost 700 times more tonnage than the small, domestically oriented yards in South Korea. Five years later, after HHI had established South Korea’s first internationally competitive yard in Ulsan and rapidly increased output, production in Great Britain was still three times higher. This was soon to change. By 1985 the tonnage produced in South Korea was fifteen times larger than what British yards produced, while HHI alone completed ten times as much tonnage as all the British shipbuilders put together.Footnote 3

This picture remains unchanged today. In 2015 South Korea received more than a third of all new shipbuilding contracts, while China and Japan each received slightly less than 30 percent, implying that more than 90 percent of all shipbuilding contracts went to those three countries.Footnote 4 The case of shipbuilding is therefore a good example of the manner in which market shares within manufacturing moved from Europe to Asia.

The aim of this article is to establish how HHI transferred shipbuilding skills from Europe to newly industrializing South Korea in connection with the establishment of the first large-scale shipyard in the country. In 1970, Ulsan was a small inconsequential fishing village and no shipbuilding facilities existed there. However, by the middle of the 1980s, HHI’s Ulsan shipyard had become the world’s largest, a position it still holds. This article presents the early history of HHI, with emphasis on the personnel who traveled to Europe to acquire the technical and practical know-how that was necessary to establish and operate a world-class shipyard.

The construction arm of the Hyundai conglomerate had long experience in civil engineering projects, such that building a greenfield shipyard was well within its sphere of expertise. However, in the case of shipbuilding, specific knowledge was mostly lacking. HHI partly solved this by bringing in some engineers from South Korea’s only shipyard of note, Korea Shipbuilding and Engineering Company (KSEC) at Busan, a yard that had only built comparatively small ships, focusing on the home market.Footnote 5 While KSEC had no experience of projects of this size, it was familiar with some of the technology and processes. To put the scale of the new plans in perspective: Before 1972 the existing shipyards in South Korea had never produced more than 43,000 gross register tons in a single year. From the outset, HHI was designed to produce more than 700,000 gross register tons annually.

Hyundai’s founder and entrepreneurial chairman, Chung Ju-yung (1915–2001), realized that Hyundai needed to learn from foreign experience by assimilating bought-in technology and utilizing international expertise. The aim was to avoid many, if not all, of the inevitable pitfalls of “learning by doing,” an iterative process wherein prior mistakes are not repeated. Shipbuilding is a material-intensive assembly industry, and such mistakes would be inherently costly.Footnote 6 Chung Ju-yung was, in many respects, a classic entrepreneur from a poor background who went on, after many trials and tribulations, to establish a world leader conglomerate in construction, engineering, motor cars, and shipbuilding.Footnote 7

Theories on knowledge transfer often make a distinction between codified (explicit) knowledge and tacit knowledge.Footnote 8 The difference between the two types of knowledge is not necessarily clear-cut, and there has been considerable debate about their definition and application.Footnote 9 While codified knowledge typically is easily transferable because it is documented, organized, and accessible, tacit knowledge is mainly transferred through observation, demonstration, practice, and hands-on experience.

It is evident that Chung was aware of the need to supplement codified knowledge by tacit knowledge when establishing the new shipyard facilities. He realized that it would be virtually impossible to conduct the production work in the shipyard only with the acquisition of codified knowledge, such as design templates and manuals. Although technology and codified knowledge are necessary for building ships, “knowledge in the shipbuilding industry is mostly tacit knowledge and highly based on individuals’ experience and perceptions.”Footnote 10

This aspect has important implications for knowledge transfer within shipbuilding. The fact that tacit knowledge tends to be context specific makes it more difficult to diffuse than other types of knowledge. This leads to “stickiness,” as the tacit knowledge must be verbalized within its original context before it can be transferred to other people and, ultimately, other contexts.Footnote 11 Consequently, with a two-step transfer process, there are more potential barriers or restraints, and thus additional factors that can impede or reduce the quality of the transfer.

A recent case study from the shipbuilding industry suggests that tacit knowledge tends to be “deeply embedded in individuals or companies and is often difficult to articulate, it tends to diffuse slowly, and only with effort and the transfer of people.”Footnote 12 This was undoubtedly the case in the early 1970s as well, and international exchange of personnel came to play a key role in the establishment of the Hyundai yard. Foreign managers were transferred to South Korea, and South Korean personnel were sent abroad to learn.

In 1972 two groups of employees from the Hyundai Construction Company traveled to the shipbuilding towns of Greenock and Port Glasgow on the lower Clyde in Scotland, where they would be spending the next twenty-three weeks. The employees came from various backgrounds but had one common aim: to learn how to build oil tankers of 250,000 deadweight tons (dwt) and above, so-called very large crude carriers (VLCCs), and to get a better understanding of how to organize production in a shipyard. Based on archival material from Scotland and South Korea, as well as interviews with some of the Korean and British participants, this article provides information about the personnel who received training in Scotland, the way training was organized, and the means by which the knowledge was transferred back to South Korea.

The South Korean archival sources about the early days of Hyundai yard and the knowledge transfer from the United Kingdom are very limited. Our main primary source has therefore been the Scott Lithgow archives at the Business Archive Centre, University of Glasgow. This archive contains internal and external correspondence with regard to the South Korean visit. The archival information has been complemented by five additional sources. First, the authors have conducted one lengthy interview with Jeong Je Kim, professor emeritus in the Department of Naval Architecture of Ulsan University, who was part of the first cohort to visit Greenock. Second, we have circulated a questionnaire among some of the surviving participants and received four answers. Third, we have used information from a contemporary interview with three of the Korean workers in the Scott Lithgow company magazine, which sheds light on their stay there. Fourth, Hwang’s Let There Be a Yard—an autobiography by one of the participants—has been used to gather information about the stay in Scotland. Finally, in addition to these South Korean sources, we have used the recollections of five non-Korean observers.

The Korean shipyard workers who went to Scotland were an all-male group, all of whom had completed higher education, usually within engineering. Their backgrounds varied; some had experience from other smaller Korean shipyards, while some had worked on different types of projects in other parts of the Hyundai Construction Company group. After working full days alongside their Scottish colleagues at the Scott Lithgow shipyards and associated marine-engine building works, the Koreans retreated to a rented boarding house in Greenock, where they processed the day’s work.Footnote 13 This included preparing documentation and reports for their colleagues who were simultaneously building the shipyard facilities and the first VLCC in South Korea. In addition, a large up-to-date Xerox copying machine was purchased to photocopy technical plans and work schedules daily—a classic example of distribution of codified knowledge.Footnote 14 Local management drily joked that such was the copier’s overuse that the town’s power supply was frequently interrupted.Footnote 15

In addition to presenting the workers and the manner in which their learning was organized, we address two elements of knowledge transmission. The first is the practical side: How were the skills transferred between workers who had little common language and thus had potential difficulties communicating? The second is the social side: How was life in Scotland perceived by this somewhat “unusual” group of expats?

Shipbuilding and Economic Development in South Korea

Shipbuilding played a crucial role in the industrialization efforts of Japan, South Korea, and China.Footnote 16 The industry’s backward linkages to steel production and easy access to export markets implied that shipbuilding became a favored part of public policy.Footnote 17 Shin and Ciccantell refer to steel production and shipbuilding as “generative sectors.”Footnote 18 These were at the center of the modernization of South Korea and functioned as models for firms and for state–firm relations in other sectors. When the partly state-owned Pohang Iron & Steel Company (POSCO) steel mill commenced production in 1973, deliveries to shipbuilders were intended to be one way to ensure efficient use of the output.Footnote 19

When deciding on Ulsan’s Mipo Bay as the site for the Hyundai yard, “easy access to various raw materials, domestic and imported, especially to Pohang Iron and Steel Company, Limited,” was listed as one of the four main reasons for the location. The other elements were favorable climate, the availability of an abundant labor force, and “optimum conditions in terms of harbour, soil and ground.”Footnote 20

Hyundai purchased the site with its own funds and covered the costs for moving expenses and rehousing of the local citizenry. A quay, dock, fabrication shed, administrative office, and steel stockyard were built in succession. Two building docks with 700,000 dwt capacity each were built, straddled by Goliath cranes, and a 700 meter breakwater to protect the shipyard in inclement weather was begun in March 1973. In addition to construction projects, Hyundai was already involved in the manufacture of motor vehicles and would later incorporate ship repair in 1975 (Hyundai Mipo Dockyard—a joint venture with Kawasaki Heavy Industries) and marine-engine building in 1978 (under foreign license) in tandem with their shipbuilding facilities.

Shipbuilding was one of the strategic industries targeted by the Korean authorities in the third and fourth five-year plans (1972–1976 and 1977–1981). Although this government encouragement was important, for instance, in connection with access to foreign finance, it was far from sufficient for the successful growth and competitiveness of the industry. South Korea’s attempt at penetrating the highly competitive international market for ships depended upon the ability to acquire industry-specific skills in addition to technology and customers. As in other areas of economic development, the Koreans took a leaf out of the Japanese book.

In connection with the build-up of shipbuilding competence and capacity in Japan in the late nineteenth century, missions abroad, whereby Japanese personnel received training, played an important role: “The aim of overseas missions evolved from general inspection of the foreign shipbuilding industry to searching for technologies to import and training in the technologies imported under license agreements.” Such “missions abroad were often sent for the purpose of having engineers and workers trained in technologies being imported”—a practice followed both during the establishment of Japanese shipbuilding in the late nineteenth century and its modernization after World War II.Footnote 21 For Japanese shipbuilders, missions abroad complemented licensing contracts when technology was imported. In the 1970s, South Korean business groups followed the same modus operandi, spearheaded by Hyundai for its shipyard facilities in Ulsan.

Hyundai’s renowned founder, Chung Ju-yung, had identified the shipbuilding industry as a sector in which South Korea might have a comparative advantage, particularly due to low labor costs. This coincided well with the overall industrial policies in South Korea but necessitated foreign involvement. In the late 1960s, Chung had discussed possible joint ventures with Japanese and Norwegian shipbuilders, but these discussions came to nothing.Footnote 22 In 1969 the Akasawa report, written by a team of Japanese experts, recommended that Japanese shipbuilders should refrain from cooperating with South Korean yards, as building large ships in that country would be unlikely to be viable.Footnote 23

Chung nevertheless decided to change the manner of technology acquisition from joint ventures, where he would have had less control, to licensing. This was a move that was better aligned with the main political directives for the financing of Korean industrialization.Footnote 24 He entered into negotiations with a West German yard, A.G. Weser, but their high price for ship design and consultation, combined with a demand for a 5 percent commission on future contracts, scuppered the deal.Footnote 25 The solution, however, was found in the sunset shipbuilding nation par excellence, the United Kingdom.Footnote 26

The British Connection

In March 1971 Hyundai established an office in London. Here, Chung met with Charles Brook Longbottom, a former Conservative Party member of Parliament with considerable influence in British shipping circles. One of Longbottom’s positions was chairman of the board of A&P Appledore International Ltd. (APAI), a recently formed company specializing in shipyard design and shipbuilding consultancy.Footnote 27 APAI offered Hyundai a “package” including market research, marketing, project development, design and engineering of a shipyard, development and implementation of production systems, and training of personnel and recruitment of foreign management.Footnote 28 APAI also secured the rights to exclusive export sales representation for the first twelve Hyundai vessels at a 0.5 percent commission.Footnote 29

Established in January 1971, APAI did not even have its own office facilities when the discussions with Chung began.Footnote 30 Moreover, as APAI’s skill set was not fully compatible with Hyundai’s desire to build VLCCs, management contended that they needed someone to “fill a gap in our expertise.”Footnote 31 Only three yards in the United Kingdom—Harland & Wolff in Belfast, Swan Hunter on the Tyne, and Scott Lithgow on the Clyde—had the capacity to build tankers larger than 250,000 dwt. APAI therefore “outsourced” the ship design and personnel training part of the agreement to Scott Lithgow Ltd., and the contract also included the drawings and specifications for a 260,000 dwt VLCC of a kind that was currently under construction in Scotland. Having lost money on similar projects before, the Scottish company was initially apprehensive, but decided to enter a “loose-knit non-binding association” with APAI.Footnote 32 At that stage, Scott Lithgow had already completed Gold Star, a 136,867 dwt oil tanker for the Korean Samyang Navigation Company of Incheon, with a sister vessel, King Star, near to launching. The contractual details and negotiations for both had been exhausting and protracted, particularly with respect to legal and payment terms, which explains Scott Lithgow’s initial apprehension.Footnote 33

On September 10, 1971, Chung and Longbottom signed the “technical assistance” agreement, with Scott Lithgow’s managing director Alexander Ross Belch as witness. That month, Chung also visited the Scott Lithgow facilities.Footnote 34 After returning to South Korea, he met with the “government authorities concerned and fully explained to them about the contents” of the agreements, to which the “government authorities expressed an affirmative reaction in general.” The final, formal approval, however, was not as uncomplicated as Chung had anticipated, because the Korean authorities wanted the foreign loan agreements submitted at the same time as the project plans.Footnote 35

Longbottom and APAI helped to arrange a US$14.4 million loan from Barclays Bank in the United Kingdom and assisted Hyundai in its negotiations with the British Export Credit Guarantee Department (ECGD).Footnote 36 This was a crucial part of the agreement, and one that APAI took very seriously. If no publicly guaranteed financing from the United Kingdom was available, there could be no deal, as Chung would not be able to obtain the necessary licenses in South Korea. Based on previous experience, APAI was fully aware that the question of export guarantees could be a deal breaker. The company had previously tried to arrange a similar project with South American interests, but a “remarkable credit deal” from Norway and delays in the ECGD legal department had resulted in the loss of the contract.Footnote 37

In addition to the British funding, Chung ensured foreign financing by linking purchases of equipment for the shipyard to credit provided in other European countries that were eager to export machinery. In the beginning of December 1971, the 62nd Foreign Capital Inducement Committee approved more than US$50 million of loan agreements between Hyundai and “lenders of Spain, France, West Germany and the United Kingdom.”Footnote 38 The committee simultaneously approved the technical assistance agreement between APAI and Hyundai.

By the beginning of 1972, Hyundai had entered into agreements about technical assistance, foreign funding, and shipyard equipment purchases. This last included cranes from West Germany; boilers, pumps, and presses from the United Kingdom; jib cranes and gas cutting machines from France; automatic welding machines and Stal Laval turbines from Sweden; and ordinary welding machines from Spain.Footnote 39 The company had also managed to sign crucial newbuilding contracts with a Greek shipowner, George Livanos, for two VLCCs of the Scott Lithgow design at a purchase price of US$30,950,000 each.Footnote 40 The company’s plans were ambitious—the tankers would be more than ten times larger than any ship previously built in South Korea and the shipyard would be constructed at the same time as the first vessels were being built. Moreover, although Hyundai had a “Shipyard Project Department,” the excavation of the shipbuilding facilities and the training of key personnel had not yet begun.

The technology purchased abroad ensured that Hyundai had the technical foundation needed for the establishment of the yard. The technology in some ways embodied the codified knowledge, through technical communication documents such as manuals, user guides, and instructions. However, while the company had been able to obtain the machinery needed to construct ships, the workforce lacked any practical experience in building large vessels. This tacit knowledge was also “imported” to South Korea, partly through the employment of foreign expertise, but primarily through the training of South Korean workers abroad.

The Training Program

The original plan, as outlined in the agreement between APAI and Hyundai, was that “two groups of thirty will be trained and each group will be in our establishment [Scott Lithgow] for approximately six months.”Footnote 41 Hyundai would cover all expenses in connection with the training, and the instruction would not begin before Hyundai had paid the first installment to Scott Lithgow via APAI.Footnote 42

In the early spring of 1972, Hyundai rented a guesthouse that could accommodate twenty members of their party plus a female Korean cook; the remainder were put up in hotels and private accommodations around Greenock.Footnote 43 As late as March 24—the day after ground had been broken at the yard in Ulsan—the Scottish yard did not know when the Koreans would be arriving, only that they had booked the guest house as of April 1.Footnote 44 Twenty Koreans arrived on April 10, 1972, with an additional seven arriving at various times during the next four weeks. The second cohort started progressively from the beginning of October.Footnote 45

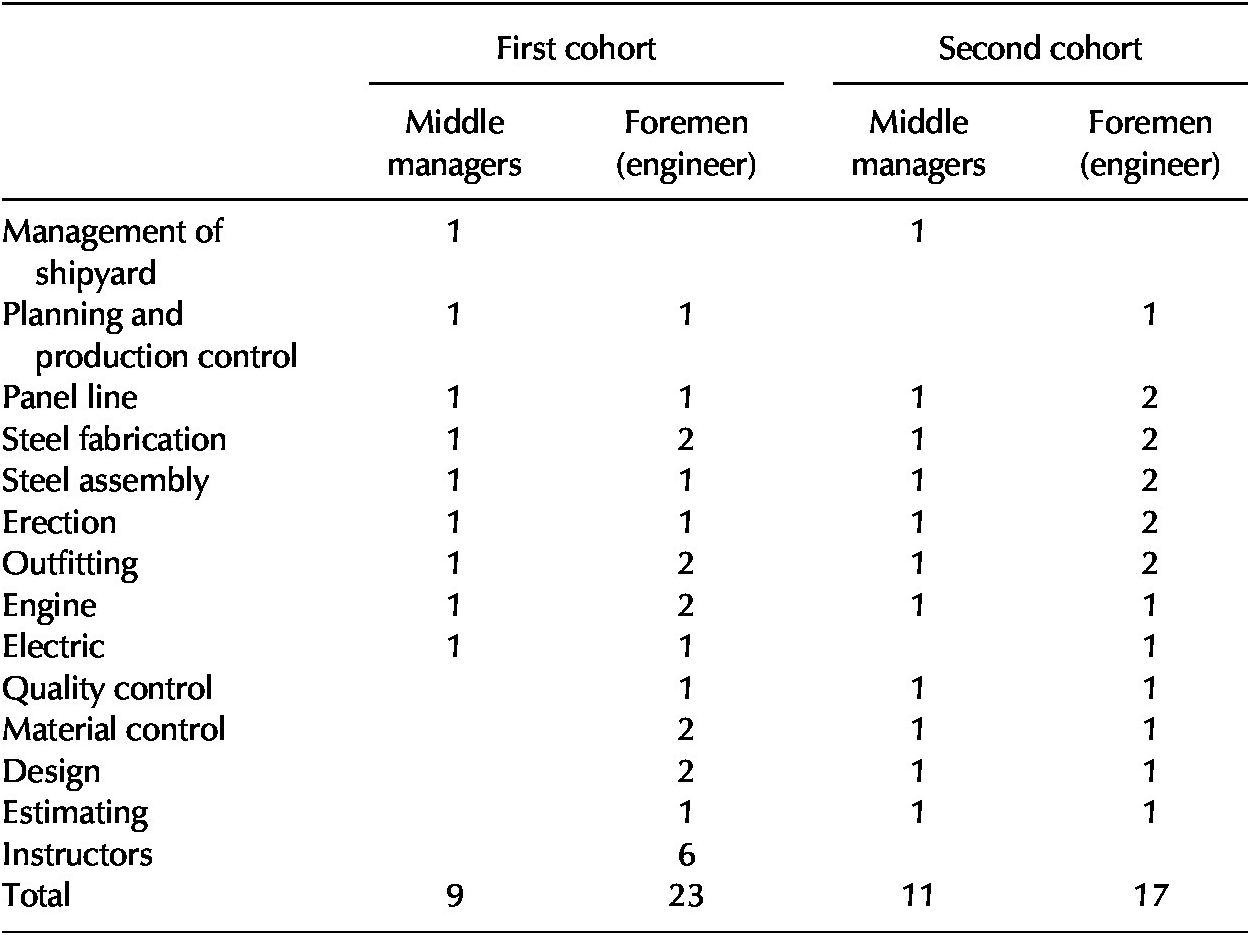

The training schedule that Scott Lithgow arranged for the Koreans was originally intended to provide facilities for training twenty middle managers and thirty-four foremen. The training was included as part of the “design package” that the Koreans had bought.Footnote 46 In the end, a training program was developed for sixty Koreans, whereby they would be allocated to specific departments, with each receiving training for up to twenty-six weeks. Table 1 details the areas in which the various employees would work.

Table 1 Scheduled fields of work

Source: Over-sea training programme, undated file, Scott Lithgow Papers, GD 323/13/3/17, UGBAC. Note that the number of participants varies from the number of people who participated in the training, particularly for the second cohort, which had a shortfall in the number of people sent from Korea. Moreover, transfer of personnel between Scotland and the London office makes it difficult to give a precise estimate of the total number of people involved.

The Koreans were distributed across shipyard and engine-building departments according to their previous experience, their knowledge, and their intended duties upon returning to the new yard in South Korea. Regarding the organization of the work, there was partly a system of “job rotation,” with the aim of workers becoming familiar with several parts of the production process. Although the main tasks were determined upon arrival in Scotland, many of the workers, particularly in the second cohort, had received an indication of which kind of work they would be performing before their departure from South Korea. Consequently, there were some who had consulted relevant materials before leaving for Scotland.Footnote 47

The construction of the facilities in South Korea progressed so rapidly (or, alternatively, with such challenges), that it became necessary for some of the first cohort—five instructors—to leave earlier than originally intended.Footnote 48 Their British partners referred to the South Korean project as “an extremely ambitious production programme”—within the span of two years, the Koreans would build one of the world’s largest shipyards, as well as its first VLCC, Atlantic Baron. Footnote 49 The amount of learning involved created a need for close cooperation, and the Koreans in Scotland sent reports more or less daily, both to the London office and to their home country.Footnote 50 At the same time, the early departure of the five instructors shows that the written documentation was insufficient. Priority was clearly given to getting someone with practical experience—tacit knowledge—on the spot in Ulsan.

In addition to daily communication, which often solved short-term problems and answered specific questions, there was the more fundamental knowledge exchange. Every single Friday, except for holidays, a new set of plans, arrangements, and drawings would be transferred to South Korea. In total more than 100 large dispatches were sent in the period from February 1972 to May 1974, and the effect on the recipients in South Korea was overwhelming. They signaled to the Scottish yard that they found the plans “difficult to follow” and simultaneously complained that they would prefer to receive everything at once as soon as possible.Footnote 51 However, Scott Lithgow was building an identical ship, although by a different build method, and forwarded the information as it was created.Footnote 52 Given that the production occurred in a parallel manner in the two countries, the Scottish yard was unable to change its manner and timeline of production to speed up the transfer of technical information. Moreover, Korean personnel at Ulsan were unable to read design drawings from overseas, necessitating the hiring of foreign technical consultants proficient in English.Footnote 53

The builders of the ships in South Korea were not the only ones who were overwhelmed. For the workers who travelled to Greenock, the facilities, particularly the gigantic Goliath crane, 287 feet high, capable of lifting to 225 tons, and straddling an inclined concrete mat (1:24 declivity) at the Glen yard in Port Glasgow, made a big impression: “The scale of the yard, large blocks, Goliath crane, large slipway facilities, skilled workers, design skills were all new to me.”Footnote 54 At Ulsan, HHI purchased two West German–built Goliath cranes, 269 feet high and 459 feet in width, each with double the lifting capacity of the Glen yard crane. These were better suited to HHI’s building-dock method of construction and its aim of building ultra large crude carriers (ULCCs) up to 550,000 dwt. Both were operational by April 1974.Footnote 55 This expensive purchase showed Hyundai’s ambition to be a major player in world shipbuilding; not only could the cranes be used to build ULCCs, they could also be used to construct several smaller vessels simultaneously in building docks if the market required it.

Scott Lithgow had a far greater product mix and technological capability than Hyundai. VLCCs were, in shipbuilding terms, relatively easy to build. However, Scott Lithgow’s move into VLCC construction was not without difficulty. Its method of separately building the fore and aft sections of the ship and then welding them together on the water with the aid of a specially constructed cofferdam at the join was technically demanding. Hyundai’s building-dock method, wherein prefabricated welded block sections of the ship constructed in adjacent prefabrication sheds were placed in the dock by the Goliath crane and then welded together, was a more efficient method of construction, and in line with modern Japanese methods. Scott Lithgow had considered plans to build a giant covered shipyard on two occasions but found the cost prohibitive, especially as government funding was not forthcoming to cover a substantial part of the cost. Footnote 56

Although they were impressed by the sheer scale of the ship under construction, the equipment, and the operation in general, the Koreans had a more ambiguous attitude toward the shipyard facilities in general. Specifically, several of the participants refer to the Greenock yard as “old-fashioned,” using “old methods of ship construction,” and relying on “traditional ways of work.”Footnote 57 Interestingly, some interviewees—without prompting—suggested that the outdated production system and the fact that “productivity was not high” were the result of strong labor unions.Footnote 58

This link between the backwardness and low productivity at Scott Lithgow and the prominent role of the labor unions might have roots in the South Korean experience. In the South Korean case, unionization was “explicitly banned” until the late 1980s, with the exception of the government-sanctioned unions belonging to the Federation of Korean Trade Unions.Footnote 59 As Hwasook Nam has explained, KSEC became the “loser” in the South Korean foray into the shipbuilding industry.Footnote 60 Before Hyundai, KSEC had been the country’s leading shipbuilder (though on a much smaller scale and without an international orientation). Nam suggests that the “militant, democratic and powerful” union at KSEC might have been one of the reasons that it was lagging in terms of productivity and business and never managed to participate when the South Korean shipbuilding venture took off.Footnote 61 In fact, several of the workers Hyundai sent to Scott Lithgow had some experience at KSEC.

Management at the Scottish yard was also clearly apprehensive about the labor unions and their influence. In connection with the press release that was sent out when the contract was made public, Scott Lithgow’s managing director Ross Belch specifically asked A&P Appledore “not to use the expression ‘the low labour rates and high productivity in Korea.’” The reason for this was his fear that such an association would create problems in the relationship with the local unions at Scott Lithgow.Footnote 62

The Greenock Cohort

The Scott Lithgow archives contain detailed information about the background of twenty-seven of the workers. They were all male, spanning in age from twenty-seven to forty-two years with an average age of thirty-three years.Footnote 63 Eight of the men were single, while nineteen were married. All of the participants had completed higher education in advance. Although we should ideally have had information about all the workers who went to Scott Lithgow, there is no reason to expect that our sample (more than half of the total) differed from the rest of the workers along dimensions such as age, education, and employment background.

Table 2 shows that the educational background varied, though—unsurprisingly—with a bias toward naval architecture and engineering. With one exception, all the workers had completed four-year degrees; the exception was one who held a six-year degree. All had degrees in various types of engineering and naval architecture, except for one, who had a law degree. He had, however, vast and valuable experience in logistics and supply from the Korean army, including a stint of training in the United States. In fact, the proportion of personnel with experience from abroad—eight of the twenty-seven—is surprisingly high.Footnote 64 It is likely that Hyundai actively sought out people with experience from foreign work. They would be less susceptible to “culture shock” and were also likely to have a working level of English.

Table 2 Korean cohort in Greenock by type of university education

Source: Database compiled based on personnel information in Scott Lithgow Papers, GD 323/13/3/14, UGBAC. Due to rounding, the numbers add up to more than 100 percent.

The workers that Hyundai sent to Scott Lithgow were among the best educated in the corporation, not only in terms of the type of education, but regarding the institutions where they had studied. Table 3 shows that more than half of the workers had been educated at two of the most respected seats of higher learning in South Korea.

Table 3 The Greenock worker’s education by institution

a The five other universities were Seoul University, Republic of Korea Naval Academy, Dong-A University (Busan), Yonsei University, and Pusan National University.

Source: Database compiled based on personnel information in Scott Lithgow Papers, GD 323/13/3/14, UGBAC. Due to rounding, the sum exceeds 100 percent.

Eight of the personnel, almost a third of those about whom we have detailed information, came from Seoul National University—the most prestigious university in South Korea. The Korean–American collaboration, In-Ha [Incheon Hawaii] Institute of Technology, which was awarded university status in 1971, was the second most common alma mater.

It has been claimed that Hyundai “enticed” skilled workers from other yards to join the project by offering them higher wages.Footnote 65 The fact that more than half of the workers had shipyard experience—and that Hyundai was new to the shipbuilding industry—suggests that this might be the case. However, a closer look at the information in the Scott Lithgow personnel file suggests that the extent of direct poaching was limited in the case of the Scottish cohorts; only four people came directly from other shipyards to Hyundai Construction Company’s shipbuilding project.

The others—more than three-quarters of those with shipyard experience—had worked in other industries between their shipyard employment and being hired by Hyundai. This reflected the fact that the existing small- and medium-sized South Korean shipyards had difficulties securing work and operated at only around 20 percent of capacity. Of course, the ex–shipyard workers’ education and experience were valuable. However, their interim employment in other sectors suggests that they had been unable to utilize it properly before the construction of the Hyundai yard.

The Hyundai project was in many respects a new start both for the workers and for the city of Ulsan. An article in the Wall Street Journal in early 1974 points out that “two years ago a bumpy dirt road meandered through rice paddies to a small fishing village. The road is still there, but the paddies and village have been replaced by a mammoth $100 million shipyard, capable of producing the biggest and most sophisticated supertankers.”Footnote 66 The workers were part of a great modernization and urbanization project. By the time they went to Scotland, none of them had their main residencies in Ulsan. Four of the twenty-seven workers for whom we have information lived in “nearby” Busan, 45 kilometers away, and another four in other cities and villages in southwestern Korea, while around half the workers were residents of Seoul, more than 300 kilometers from Ulsan.Footnote 67

The theoretical and practical backgrounds of the workers sent to Scotland to learn how to build ships suggests that they were carefully chosen by Hyundai. That all were university graduates was in stark contrast to Scott Lithgow and British shipbuilding generally. Apart from naval architects, many of whom were also managing directors, graduates were in very short supply in British shipyards. The cult of the practical man (a man hewn from the rock of applied practical experience) still held sway.

The limited role of formal qualifications in the British shipbuilding industry illustrates that tacit knowledge, learned through apprenticeships and via on the job training, clearly was an important means of developing skills within shipbuilding. However, acquiring such knowledge was usually a time-consuming process—Scott Lithgow’s skilled manual workforce had to undertake low-wage, nonunionized apprentice training for four years. The first year of the apprenticeship was spent at a purpose-built training center at the Great Harbour in Greenock, and the last three in on the job training supervised by (five-year) qualified tradesmen and foremen.Footnote 68 The South Koreans, in contrast, would only spend six months at the yard. Moreover, during this period, there were practical challenges. One potential problem was communication.

Communication Challenges

The Korean workers had limited experience with the English language, particularly the spoken kind: “Before we left home we worried about how we would learn—we all spoke English, but we wondered if we would be able to speak it well enough.” Practically all of those interviewed refer to problems—in particular, initially—of understanding the very strong Scottish accent and local dialect. However, none of them saw this as particularly problematic in relation to the actual training: In the “technological” setting, and aided by drawings and materials, the language barriers were overcome. In an interview in the Scott Lithgow company magazine, one of the workers pointed out that “our instructors have been very kind very warm-minded, and they have made it easy for us.”Footnote 69

The extent to which language was a barrier varied among the Koreans. Eung Sup Kim, a member of the second cohort, points out that “since all of us were college graduates we had basic ability in English. As our communication on the job was concerned with things and technical matters there was no major problem in language.”Footnote 70 However, initially, there were some difficulties “in understanding the Scottish pronunciation and accent, which would take some time to overcome.”Footnote 71 Given that “there were many who had a hard time to understand the Scottish accent,” the second group specifically included a manager who had studied abroad and worked in the company’s London office. “Thanks to his function as a problem-shooter there were no major problems in our communication with the Scots,” according to one member of the second cohort.Footnote 72

While casual conversation might have been difficult due to the strong West of Scotland accents and dialect, as well as the prevalence of shipyard workers’ slang, this was unproblematic in the more formal setting. Discussions about technical matters were relatively straightforward; “We had no particular problem because our communication on the job was done while looking at materials and drawings.”Footnote 73 This manner of knowledge transfer illustrates the complementarity between the codified knowledge (documents and manuals) and the tacit knowledge transfer (hands-on supervision and face-to-face exchanges).

Moreover, one ingenious solution to overcome the pronunciation problems was to resort to nonverbal communication. In addition to pointing and “sign language,” the Koreans and the Scots were “writing messages to each other, to better understand,” and this type of communication was widely used. Preparation could also help: “Thanks to my experience in design and production prior to my employment with Hyundai, however, I was able to manage rough communication about matters of concern. […] When I had difficulties communicating, I tried to use easy words and talk slowly. That helped. In this way we could achieve mutual understanding.”Footnote 74 This is a prime example of the manner in which the Koreans’ preparations and their previous experience facilitated the transfer of tacit knowledge. The criteria for selection (background, education) ensured that there was a good match between the existing and the new knowledge, implying a high “absorptive capacity.”

Although several of the Koreans refer to the language barrier as the one thing that they were most skeptical about before going, it is evident that language learning complemented the technical knowledge transfer. The author of an article in the Scott Lithgow company magazine was indeed impressed by the speed with which the Koreans picked up Scottish phrases and accents.Footnote 75

All Work and Some Play—The Social Dimension

The experiences in a foreign country undoubtedly played a formative role for the workers that went to Scotland—the fact that several of them still meet regularly is testament to the bonds that were formed, both abroad and when they returned to South Korea to build up the yard. Although they worked long days, there were also some diversions.

When they were in Scotland, the South Korean workers followed their Scottish counterparts and worked at least eight hours a day, six days a week. In addition to the regular “Scottish working week,” after returning home, they would spend around two hours writing reports for South Korea and London. Still, this was not a big burden compared with what they met when they returned to Ulsan, where they would typically work twelve to thirteen hours daily, seven days a week.Footnote 76

In an interview with the Scott Lithgow company magazine, one of the Koreans explained their motivation: “We are trying to do in a few years what western countries took many years to do.”Footnote 77 Similarly, Eung Sup Kim today emphasizes the collective project: “We worked long hours voluntarily without a complaint because we were convinced that it would be impossible to upgrade our technology fast and to meet our production schedule without working such long hours. Probably it was possible as we were all young then.” Footnote 78 The workers were particularly intrigued by the Scottish idea of weekend getaways; “In our country we could not expect our families to go away at the weekends as you do here.… Weekends must come later … we are not yet a developed country.”Footnote 79

Although almost a third of the workers in our sample had previous experience outside South Korea, it is evident that there was a culture shock involved when they arrived in Scotland. Originally, the Koreans had a certain curiosity about “the country of Auld Lang Syne” and famous inventors such as the Greenock-born James Watt.Footnote 80 They were impressed by the kindness and welcome of the local people: “You are kind and polite, and the weather is terrible.”Footnote 81 And the sentiment was mutual; the Scottish workers refer to their colleagues’ “friendliness, easiness and sense of humour” and also “admired their capacity for work.”Footnote 82 One Scots engineer said that they reminded him of the work ethic of his father’s generation.Footnote 83

The good relationship and mutual appreciation among the Scots and the South Koreans were not a given. The Scottish shipyard employees worked side-by-side with a group of foreigners who in the future would become competitors, threatening their own jobs. However, an engineering director working at Scott’s had a pragmatic attitude to the transfer of skills, stating that “if we did not train them, then someone else would. We were perhaps nevertheless contributing to our own eventual downfall.”Footnote 84

The Koreans were fascinated by the foreign customs and culture that they encountered, but “there is one very strange thing about Scotland, this competition that you have between religions, between your Catholics and your Protestants.”Footnote 85 Aside from the sectarian issue, another unexpected element was the food; most of the Koreans were vegetarians, more for economic than for health or religious reasons. They were pleased to have pork and beef, and they thought that “your mashed potatoes are very interesting. We had never tasted potatoes before.”Footnote 86 They had the high-calorie Scottish breakfast and lunch in the shipyard canteen, but in order to reduce the level of the culture clash, they had brought “a Korean lady” to cook the evening meal.Footnote 87

The relationship between the Scottish and South Korean workers appears to have been extremely amicable. However, it was difficult for the workers from the two countries to socialize on a private basis. Several Scottish workers would have liked to have a closer relationship, but “you couldn’t invite one of them to your house in the evening and leave the others.”Footnote 88 This was solved by arranging a “Scot’s Night” at a local club to give the Koreans a glance of their short-term home country and enable them to socialize with the locals.

In June 1972, the Scott Lithgow directors chartered an airplane, and a group that included all twenty-eight Koreans and more than thirty Scots were flown up to Oban and back to show the visitors the scenic Scottish west coast and western islands. In the evening of that same day, a huge party was arranged in the clubroom of the local Celtic Supporters’ Club. Here, the Koreans were “welcomed” by a local band playing bagpipes, before they were treated to food and drinks. After the meal, there was more entertainment, with local youths presenting Highland dancing being one of the highlights.Footnote 89

The Further Training of the Shipbuilding Personnel

The two contingents sent to Greenock played an important part in the acquisition of skills in the initial days of Hyundai’s foray into the shipbuilding industry. The sheer scale of the ships and the shipyard in the market segment that Hyundai entered implied that it would be impossible to acquire the skills simply by expanding the local knowledge base. As such, the tacit knowledge acquired by shipyard workers and middle management abroad was a vital component and an important complement to the purchase of foreign equipment and licenses.

In addition to the fifty or so people that were sent to Scotland, Hyundai utilized two other channels of knowledge transfer. First, the top management of the new yard was recruited from Europe. The Dane, Kurt Schou, who at the time was technical director at the Danish VLCC yard, Odense Shipbuilders, became the first president of the new yard. He also brought four colleagues from Denmark, who were given responsibility for four of the most important departments: scheduling, hull production, outfitting, and machinery.Footnote 90 Another three Europeans—two from Great Britain and one from France—were also recruited. Among these were Robert L. Wilson, who was recruited through A&P Appledore, and who became the director of the in-yard vocational training center in September 1972. By the end of 1975, 2,172 personnel had completed full training there, while a further 1464 had completed short courses of training.Footnote 91

The rapidity of training at Ulsan was in stark contrast to the training requirements of Scott Lithgow’s own personnel, whose apprenticeships lasted for four years. Initially, training in South Korea was complemented by European expertise on the spot. However, the skills, drawings, design, and organization acquired via Scott Lithgow were not intuitively compatible with the experiences of the Danish engineers employed in Ulsan. This paved the way for the second, and ultimately superior in the production sense, channel of knowledge transfer—from Japan to South Korea. Earlier attempts at pan-Asian cooperation had stalled due to the South Korean fear that Japan would limit the type of ships they could build, as well as lukewarm interest on the Japanese side. In 1973 the contact was reestablished.

The preferred partner became Kawasaki Heavy Industries (KHI). The deal was much the same as the one that Hyundai had with the Europeans. Engineers—including many who had been trained in Scotland—were sent on short trips to the yard in Japan to observe and learn.Footnote 92 Language, in this case, presented less difficulty. Hyundai also bought the design of a 230,000 dwt VLCC, as an alternative to the 260,000 dwt design bought from Scotland. Moreover, as in the Scottish case, a broker agreement was signed, whereby KHI would receive a commission as ships were ordered.Footnote 93

The most important difference between the Scottish and the Japanese solutions was that KHI stationed engineers in Ulsan to aid production and improve training. These engineers had direct experience with the ships that were built and the methods that were used, as opposed to the Danes, who had to adapt to slightly outdated British ideas. A simple problem can illustrate the disadvantage: while the HHI (and KHI) work and systems were based on metric measures, Scott Lithgow’s drawings and instructions were in the imperial system (feet and inches). In tandem with unified systems of measurement and work practices, cultural and language difficulties between Japanese and Koreans were much less than between Scots and Koreans.

The change in the relationship between the South Korea and Japanese shipbuilders can be explained by developments in both countries. From the South Korean side, the need for a more “integrated” solution, with technical assistance on the spot, rather than the piecemeal consulting from the United Kingdom, can explain the arrangement. Japanese shipbuilding, with its early concentration on oil tankers and bulk carriers was in a dominant position, with all major yards using the large building-dock method of construction. This was unlike the British yards, which largely constructed on building berths. As early as 1966, the output of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries’ five shipyards exceeded that of the British shipbuilding industry combined.Footnote 94

With the involvement of KHI, it became evident to Hyundai that the Scottish yard where the skills had been acquired was lacking in modern methods of work organization and technology, and the aforementioned differences in measurement systems led to additional problems.Footnote 95 As a member of the second Scottish cohort points out: “On our return home many of the second group also went to the Sakaide yard of KHI, where we were highly impressed by the cleanliness and tidiness of the facilities and workers. This was a different kind of work environment and work attitude.”Footnote 96 Consequently, Hyundai realized that cooperation with the Japanese—if possible—would be useful in making the yard more competitive.

From the Japanese side, the timing is important to explain the change in attitude. The deal between Hyundai and the Japanese was signed in April 1973.Footnote 97 By this time, two factors had changed since 1969 when Akasawa and the other Japanese bureaucrats had reported that South Korean shipbuilding would not be viable. The first was that the Koreans had proven that they could acquire the technology, and hence become potential competitors, even without Japanese support. The fear of “creating” a new competitor had outweighed the benefits of Japanese exports to South Korea in 1969. By 1973 the competitor was already a reality, and there was no need to deny the Japanese shipyards and shipyard equipment producers potentially profitable engagements.

The second change was the extreme boom in the shipping market. From 1962 to 1973 the demand for oil transports increased 17 percent annually. The order book for new ships increased tremendously, equaling almost 90 percent of the current tanker fleet at the end of 1973. This implied that the waiting time from order to delivery of newbuildings could exceed three years. The price of a new 210,000 dwt tanker shot up from US$19 million in 1970 to US$47 million four years later.Footnote 98 The Japanese willingness to cooperate should therefore be seen independently from the decision by two companies affiliated with KHI—Kawasaki Lines and Japan Line—to order a total of six new VLCCs from Hyundai. By cooperating with the Koreans, the Japanese would then get access to valuable ships, while their presence and on-site supervision would ensure the quality of the tonnage.

It is evident that the Koreans regarded the Japanese manner of production more favorably than the skills they had learned in the Scotland. For instance, the Koreans were eager to use some of the production methods and organization learned from the Japanese for the ships built to the Scottish design as well. Scott Lithgow politely declined giving too many details, saying that they considered “this information to be within our commercial confidence” and that they “do not see how our building programme will be of relevance to Kawasaki.”Footnote 99 In the short and long run, however, the KHI method of building was more suitable for the Ulsan yard. Their Scottish experiences had provided the workers with basic knowledge of shipbuilding technology, processes, and methods. Turning to Japan, they acquired more relevant and up-to-date know-how.

Creating a Competitor

Very few records of any substance from the years under consideration survive at Ulsan. Consequently, no viable comparison of productivity can be made between Scott Lithgow and Hyundai during the period of their cooperation. Nonetheless, it is clear that the initial cohort of Koreans at Scott Lithgow did learn much that was of use to them in building their first two VLCCs to the Scottish design. Hyundai’s subsequent cooperation with KHI allowed that cohort to learn alternative shipbuilding techniques more in keeping with their yard layout and product strategy. This, allied with the iterative effects of learning by doing, was beneficial to the company’s future.

Initially, the limited experience of South Korea in the international market for ships meant that foreign shipowners were apprehensive of the quality, both of the ship itself and of the production process. Shipping is an international industry, and regulation is based on a mixture of national, international, and private institutions. HHI used Lloyds Register of Shipping surveyors to monitor the quality of build of their first two VLCCs. All later orders were also subject to scrutiny by the major international classification societies, and the yards subsequently actively sought out International Organization for Standardization quality assurance certificates. As the quality of the South Korean ships became recognized internationally, the country’s shipyards, spearheaded by Hyundai, took large market shares. With the competitive advantage of low-cost production, and aided by national policies, the yards were able to expand in a declining market.

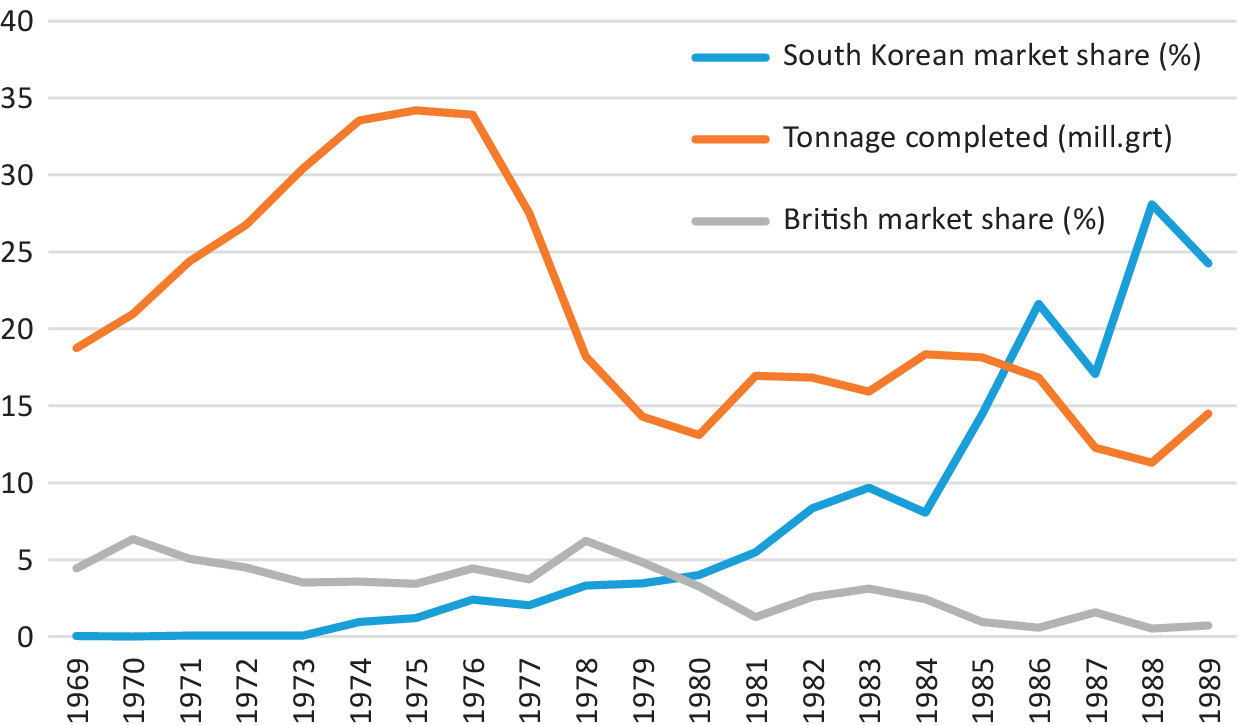

Figure 1 shows the manner in which South Korea, during the international shipping recession of the late 1970s and early 1980s, managed to grab an increasingly larger share of the shipbuilding market. At the same time, HHI’s old “teacher,” Great Britain, was practically wiped out. By 1986 HHI completed almost two million gross tons of new ships, giving the yard an 11.4 percent share of the world market. That year all British yards produced less than 100,000 gross tons. The British decline—from a market share of more than 90 percent at the start of the twentieth century—was spectacular.Footnote 100

Figure 1 World shipbuilding completions and South Korean and British market shares, 1969–1989.

In their early days, HHI specifically made a point of the skills transferred from abroad when promoting its ships. In a 1974 promotional brochure, its president, Kurt Schou, emphasized “the international conglomerate of shipbuilding technology and expertise” when “selling” the HHI to potential customers. He emphasized that the engineers and technicians “were trained at the first-rate overseas shipyards” and are working “under the close supervision of top-notch foreign staffs.”Footnote 101

Conclusion

A large number of factors played crucial roles when HHI, and South Korea, entered the international shipbuilding market. The first contract with a foreign shipowner for two large tankers was the “door opener” needed to start the project. Foreign loans made it possible to finance the imports of plant and equipment, thus ensuring that the technology needed to build ships was in place. The Hyundai conglomerate’s expertise in construction and project management was matched with shipyard consultants from the United Kingdom, and foreigners employed in key management positions were important in the first years of the yard’s existence.

Nevertheless, shipbuilding is a labor-intensive industry and the end product relies on the skills and competence of the workers. The training of workers at yards in Scotland was an important supplement to the imported technology and the codified knowledge acquired from abroad. Hyundai sent personnel with relevant higher education and often with experience from working abroad. Thus it ensured high absorptive capacity by matching initial experience with the tacit knowledge acquired during face-to-face contact. On their return to Ulsan, the workers with experience from Scotland would oversee a massive training program in the new yard facility.

The adroit use of human capital and transfer of tacit knowledge, initially from abroad and subsequently within the yard, is one explanation of how HHI could become the world’s leading shipbuilder.Footnote 102 Allied with the drive and vision of Chairman Chung to construct a vast greenfield shipyard in Ulsan, the technology and knowledge transfer enabled the birth of an internationally competitive shipbuilding industry in South Korea. Subsequently, in addition to becoming the world’s leading shipbuilding nation, South Korean shipyards have undertaken substantial foreign direct investments abroad.Footnote 103

The movement of manufacturing production from Western Europe to East Asia is not only a question of wage levels, export promotion, government policies, and technology transfer. We have provided a case study from the early days of South Korean shipbuilding, one of the industries in which Asian countries are world leaders today. Our research shows that the transfer of tacit knowledge, across cultural barriers, from one continent to another, ultimately depends on the people involved, their backgrounds, and their ability to absorb new knowledge through face-to-face contact.