An important explanation of the 2008 financial crisis is the credit market participants’ belief that mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and the structured financial instruments derived from them are bonds.Footnote 1 In a study documenting the differences in performance between bonds and MBS, Coval, Jurek and Stafford concluded that the belief that MBS were bonds was questionable because the two types of securities had different risk profiles:

The fact that corporate bonds and structured finance securities carry risks that can, both in principle and in fact, be so different from a pricing standpoint casts significant doubt on whether corporate bonds and structured finance securities can really be considered comparable, regardless of what the credit rating agencies may choose to do [emphasis added].Footnote 2

These authors argue that the belief that MBS belonged in the same category as bonds contributed to the 2008 financial crisis by obscuring the differences between MBS and bonds. Furthermore, they suggest that such obfuscation of risks associated with MBS led to underpricing of structured financial products and, consequently, greater demand for MBS, which resulted in the market bubble that burst in 2008. Other scholars also observed that the investor belief that MBS were bonds helped drive demand for both MBS and the derivative securities:

The demand among investors around the world for bonds backed by American mortgages appeared to be insatiable in the early 2000s. … Key players on Wall Street found ways to turn plain-vanilla mortgage-backed securities into more exotic financial instruments, tailored to the demands of investors seeking higher returns and willing to take on higher risks.Footnote 3

In addition to empirical studies documenting the role played by the investor beliefs in the lead-up to the 2008 crisis, scholars have also developed theoretical models exploring how investor beliefs link financial innovations and financial crises. In one such model, the belief in an innovation’s comparability to existing products contributes both to the innovation’s diffusion and the subsequent crisis:

In response to demand, financial intermediaries create new securities offering the sought after pattern of cash flows, usually by carving them out of existing projects or other securities that are more risky. By virtue of diversification, tranching, insurance, and other forms of financial engineering, the new securities are believed by the investors, and often by the intermediaries themselves, to be good substitutes for the traditional ones and are consequently issued and bought in great volumes. At some point, news reveals that the new securities are vulnerable to some unattended risks and, in particular, are not good substitutes for the traditional securities. Both investors and intermediaries are surprised by the news, and investors sell these false substitutes, moving back to the traditional securities that have the cash flows they seek [emphasis added].Footnote 4

Applied to the 2008 crisis, this model suggests that—much like the empirical work has shown—the belief that MBS were bonds helped grow demand for the securities. Furthermore, the differences between MBS and bonds, ignored before the crisis, played a prominent role in triggering the crisis.

These accounts of the 2008 crisis suggest that the question of how market participants came to believe that MBS were bonds is fundamental to understanding the development of both the MBS market and the 2008 crisis. However, the existing literature offers little insight into the origins of this belief. A rich literature on the antecedents of the 2008 financial crisis has considered the previous episodes of mortgage securitization, the role of government in shaping the housing markets, the evolution of mortgage lenders, and the role of financial innovation in shaping regulation.Footnote 5 To date, however, little is known about the emergence of the market participants’ beliefs about MBS. Such oversight is especially surprising given that the very language used to refer to credit markets invokes the role of beliefs. Indeed, the word “credit” itself traces its etymology to the past participle of the Latin verb credere (to believe).Footnote 6

To address this fundamental question, I use a historical approach to investigate the process by which bond investors came to accept MBS as a legitimate tradable instrument, namely, bonds. Specifically, this article traces the emergence, evolution, and acceptance of MBS by bond investors in the United States between 1968 and 1987. In analyzing this question, I consider two approaches MBS issuers employed to promote the acceptance of MBS as bonds: (1) changing the attributes of MBS to make them more bond-like, and (2) changing the meaning of the bond category by expanding its boundaries to include securities with mortgage features. In undertaking this study, my purpose is to contribute to the historiography of the 2008 financial crisis, the historiography of credit markets more broadly, and the emerging field of financial history.

This article is structured as follows. The first section situates the contribution of this article in the existing literature. The second section describes my sources and methods. The third section considers the attempts to sell mortgages to bond investors that predate the MBS market. The fourth section examines the MBS issuers’ attempts to make MBS more bond-like by changing the features of mortgage-like MBS to resemble bonds. The fifth section describes MBS issuers’ efforts to change the boundaries of the bond category by issuing mortgage-backed bonds and gradually infusing them with mortgage features. The sixth section analyzes the process of investor belief evolution. The seventh section discusses the implications of my findings and concludes.

Existing Literature

The existing literature on the history of securitization makes three important assumptions. One, it takes for granted the successful diffusion of MBS—an assumption that implies the immutability of the structure of MBS and precludes the investigation of how MBS structures evolved. Two, its analysis of the process by which the successful diffusion of MBS was achieved focuses on the role played by the U.S. government without considering the role played by the investors’ beliefs. Three, it assumes that MBS issuers achieved the bond category membership for their products by changing the products to conform to the category boundaries. Below, I describe in detail these assumptions and how my work fills the gaps in the literature. I then discuss how my work relates to the broader literature on financial innovation.

Taking for Granted the Success of MBS

With notable exceptions, the post-2008 literature on the role of securitization in the financial system takes for granted the successful diffusion of MBS and the acceptance of MBS as bonds. For example, Greta Krippner writes, “The securitization of housing finance was enormously successful, and as policymakers had hoped, it helped to stabilize the mortgage market.”Footnote 7 Here, the success of securitization is measured against the goal of stabilizing the mortgage market, achieved through the successful diffusion of MBS. This assertion fits well with Krippner’s argument about the role played by financialization in today’s society; however, it does not shed light on the process by which the success was achieved.

Another important aspect of the MBS success that scholars have taken for granted is the securities’ membership in the bond category. For example, Gerald Davis describes home mortgages as the prototype source material for other kinds of securitization. The membership of MBS in the bond category serves as a building block for his argument that “securities can be created out of nearly any kind of actual or potential stream of cash. Home mortgages are perhaps the prototype: mortgage-backed securities are bonds backed by the mortgage payments of homeowners.”Footnote 8

Neither Krippner nor Davis purport to unpack the processes by which MBS achieved their success. However, the assumption of securitization’s success permeates this literature, creating a sense of the immutability of MBS over time. One piece of evidence for this sense is that neither Krippner nor Davis mention which type of MBS they are referring to. The extent to which other researchers do specify the type of MBS they refer to, they typically do not articulate either the relationship between the different types or the different instruments’ role in promoting the acceptance of MBS.Footnote 9

In response to this taken-for-grantedness of MBS success, some scholars have called for investigating the process by which MBS won acceptance. Sarah Quinn, for example, argues for the importance of a historically grounded understanding of the process by which MBS gained acceptance:

The decisions firms made about securitization in the 1970s and the 1980s have had profound global consequences. As money poured through American firms and into American homes at previously unheard of levels, the unchecked largesse eventually had a devastating effect. But in the aftermath of these events it is easy to forget that until the 1980s many financial companies were unwilling to buy mortgages under any circumstance, believing that securitization was overly complicated and risky. Firms had to learn to stop worrying and love securitization. How did this happen? How exactly did the structure of these instruments change? [emphasis added]Footnote 10

This call for future research highlights the importance of investigating the evolution of investor beliefs and the evolution of financial instrument structures in understanding the success of MBS.

As Quinn points out, one of the challenges of understanding the history of securitization and the acceptance of MBS as bonds is the need to keep track of the evolving structure of the instruments. Tracking this evolution points to a puzzle in the existing literature. On the one hand, Sellon and VanNahmen argue that the evolution of MBS securities was shaped by an imperative to fit MBS into the bond category: “All mortgage-backed securities share a common goal: to create a security that is similar to and competitive with other debt instruments in the capital market.”Footnote 11 On the other hand, while the efforts to convince investors that MBS were bonds succeeded, the acceptance of MBS as bonds is remarkable because the structure of the securities is markedly different from that of conventional bonds. Indeed, Quinn articulates how the structure of MBS differed from that of financial instruments in prior mortgage securitization attempts: “An important thing to note about the use of securitization at the end of the twentieth century in the U.S. is that the process does not just entail the creation of debt instruments backed by a pool of assets like mortgages, but that those collateralizing assets are removed from the issuers’ balance sheets.”Footnote 12

As this description makes clear, the structure of MBS is at odds with the understanding of debt as an obligation between two parties—in the case of bonds, an issuer and an investor. Once the collateral is removed from the issuer’s balance sheet, the resultant product ceases to be an obligation of the issuer. This means that MBS were accepted as bonds by investors despite not fitting the definition of debt, leaving open the question of how this acceptance came about.

The Role of the U.S. Government

The extent to which the existing literature has an explanation for how MBS became bonds, it focuses on the role of the government in helping facilitate this acceptance:

The U.S. government was not the only entity to use complex debt instruments to sell mortgages and shuffle around assets in the postwar period. Still, at the end of the 1960s, it put its weight behind the market, and doing so, the government played an important role in helping mortgage bonds enter the mainstream. In the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s the government and a select group of investors worked hard to convince the business world at large that it was a good idea to invest in these securities and, through them, in the housing market [emphasis added].Footnote 13

This account articulates the rationale behind the government’s securitization efforts as attracting private investment to the housing market.Footnote 14

Other scholars share this understanding of the government’s goal with respect to promoting securitization. Carruthers and Stinchcombe describe the emergence of government agencies with the explicit mandate of creating a secondary market in mortgages:

As a commodity, a mortgage on a specific home is hard to know, and if known, that knowledge is difficult to communicate publicly in a credible fashion. Given this complexity, one would expect the secondary market to be rather illiquid. But through the deliberate intervention of government agencies like Fannie Mae (established in 1938), Ginnie Mae (founded in 1968), and Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, founded in 1970), illiquid home mortgages have been transformed into liquid commodities.Footnote 15

Carruthers and Stinchcombe claim success on behalf of the government agencies in making mortgages more liquid, that is, more acceptable as tradable investments.

The issuance of MBS became a critical step in helping the government agencies achieve this goal. Black, Garbade, and Silber offer the following description of the emergence of pass-through securities, one of the earliest forms of MBS:

In 1970, the Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA), a division of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, innovated a modified pass-through program for FHA mortgages [mortgages the repayment of which was insured by the Federal Housing Administration]. The program sought primarily to reduce yields on FHA mortgages by improving their marketability. More specifically, GNMA sponsored the issuance of relatively homogeneous pass-through securities, that is, claims on interest and principal payments given off by pools of specific FHA mortgages, modified by a guarantee that payments on those mortgages would be made promptly, even in the event of mortgagor delay or default. It was hoped that non-traditional mortgage investors would be willing to hold the GNMA pass-throughs because of their marketability (stemming from the reduced need for credit evaluation and from greater homogeneity of the instrument). This would, in turn, reduce the cost of credit for FHA mortgages [emphasis added].Footnote 16

Their description frames the role of the government in the creation of MBS as trying to improve the marketability of government-insured loans while implicitly acknowledging the role played by investor beliefs in the process.

Two things are notable in this description of the government’s role. One is the emphasis on standardization or greater homogeneity of the resultant instrument as a path to marketability, that is, the diffusion of innovation. The efficacy of this path hinges critically on the investors’ acceptance of the government standardization efforts. The second is the description of the government’s action in aspirational terms (“It was hoped that non-traditional investors would be willing to hold” MBS). This description acknowledges the limits of the government’s control over financial markets. The government can engage in standardization or offer credit guarantees; however, it does so in the hope that investor demand materializes.

Quinn articulates an extreme version of the government-control hypothesis in her enumeration of the questions left unanswered by securitization researchers:

If correct, this would cause us to rethink what some of the innovation in the 1970s and 1980s was really about. It could be that the real trick might not have been in managing risk or sweet talking investors, but in changing laws. One important question then becomes why investors move to get certain laws changed at certain times.Footnote 17

Even this extreme version of the hypothesis cannot help but acknowledge investor agency in the story. Without a historically grounded account of the role played by the investors, the understanding of the process by which investors came to believe that MBS were bonds is incomplete.

Complying with the Bond Category Boundaries

In its coverage of the role the government played in turning MBS into bonds, the literature to date has focused on the process of standardization as a means of fitting MBS into the bond category. Carruthers and Stinchcombe argue that standardization of mortgages was a necessary condition for the government agencies’ success in their mission of creating a market for mortgages:

People in the highly liquid secondary mortgage market won’t accept mortgages on particular homes as homogeneous goods that will always have a price. Instead, individual mortgages have to be turned into homogeneous goods by a government agency set up to make a market out of mortgage payments. Liquidity, in other words, is a problem of public knowledge about economic assets, of how in the case of financial assets, “facts” about future income streams become sufficiently standardized and formalized, so that people know that they can be bought and sold on a continuous basis [emphasis added].Footnote 18

According to this description, government agencies standardized mortgage investments to make them palatable to the investors. Implicit in this argument is the idea that compliance with a standard would ensure success of the securitization enterprise.

Krippner argues that this standard came from other fixed-income securities traded on the market:

Policy makers reasoned that one way to bring new capital into housing would be to transform the mortgage instrument from a loan into a security that could be traded in the capital markets. This was done by assembling a pool of mortgages, standardizing them by requiring that they meet certain criteria, and then selling participations entitling each investor to a prorated share of the cashflow generated by the underlying mortgages.Footnote 19

In other words, compliance with the form of other fixed-income securities, which I conceptualize as the boundaries of the bond category, was critical to the acceptance of MBS as bonds.

Other scholars, for instance, Smith and Taggart, have argued that making MBS more bond-like drew bond investors to the mortgage market:

In this case, securitization is helped by the standardized features of the pass-throughs. … The government guarantee and restrictions on the mortgages eligible for the pool made pass-throughs far more homogeneous than the typical direct mortgage investment. This homogeneity in turn allowed the growth of secondary trading, making pass-throughs more liquid. Pass-throughs helped to satisfy investors’ increased demand for real estate-related securities. Thus, the mortgage market was opened to a broader spectrum of investors and national integration of the market was furthered [emphasis added].Footnote 20

In addition to viewing standardization as a primary approach by which MBS entered the bond category, what the three accounts above have in common is the implicit assumption that the acceptance of MBS as bonds began and ended with pass-through securities, an assumption my work seeks to unpack.

Innovation–Acceptance Process as a Change in Beliefs

Taking a step back from the context of MBS, the existing literature on financial innovation also pays limited attention to the innovation–acceptance process. Existing work in finance assumes innovations to be driven by demand, supply, or financial intermediaries’ efforts to match demand and supply.Footnote 21 To date, the literature has assumed away the need for research on the innovation–acceptance process, that is, the process by which the innovation suppliers match the needs of innovation’s target customers by postulating that the same processes that apply to technological innovations also apply to financial innovations.

Scholars of technological innovation have argued that the development of customers’ conceptual framework about innovation is a key prerequisite for innovation acceptance.Footnote 22 Paired with an observation that “in the early stages, the new product is defined largely in terms of the old,”Footnote 23 this argument implies that framing an innovation in terms of existing products may play an important role in the innovation–acceptance process. The empirical work on innovator strategies has found support for this argument; however, this work did not investigate the changes in beliefs associated with such framing.

Specifically, the empirical studies of the innovation–acceptance process have considered the use of design and labeling strategies by the innovators. In their study of Edison’s efforts to facilitate the adoption of electricity, Hargadon and Douglas make the case for the role of product design in helping facilitate innovation acceptance.Footnote 24 Edison’s design, for example, framed electricity in terms of gas by transferring lampshades—an element technically unnecessary with electric lighting—from gas lamps to electric lamps. The authors used the Edison case to argue that innovation design affects how customers fit the innovation into their conceptual frameworks and, consequently, the likelihood of innovation acceptance.

In their study of the use of category labels in framing innovations, Zunino and his coauthors observe that the labels used to categorize innovations exhibit persistence.Footnote 25 In other words, rather than inventing new labels for each new product generation, innovators consistently opt to use existing labels. This finding suggests that innovators’ choices of labels are limited by the usefulness of these labels in helping the customers make sense of the innovation.

The research to date has not directly examined the evolving relationship between innovators’ design and labeling strategies and customers’ beliefs. Thus, the question of how these interact in the innovation–acceptance process remains unanswered.

Contribution

This article seeks to offer a perspective that complements existing accounts of how MBS diffused. While acknowledging the role of government in the diffusion of MBS, I focus on the role of investors and investor beliefs in shaping the development of securitization. In so doing, I seek to understand how and when MBS became accepted as bonds by investors. My approach conceptualizes the design of individual securities as an outcome of negotiations between MBS issuers and investors. I fill the gap in the existing literature’s understanding of the evolution of MBS over time by considering the six MBS designs issued between 1970 and 1983.Footnote 26 Taken together, the different product designs represent a record of how the negotiations evolved over time. Tracing the design of multiple generations of products enables me to explain how investors came to believe that MBS were bonds. This comprehensive analysis also allows me to shed light on the role played by mortgage-backed bonds (a type of MBS that has received little attention in the existing literature) in promoting the acceptance of MBS as bonds.Footnote 27

The focus on the securities’ design allows me to resolve the puzzle of how securities with unbond-like features came to be accepted as bonds. To the extent that the literature on securitization acknowledges the evolution of MBS, it follows the logic of the category imperative literature in economic sociology, which implicitly assumes the boundaries of the target category to be fixed. Presented with fixed boundaries, an innovator has two options: either change the product to fit it into an existing category or create a new category.Footnote 28 The existing literature on securitization assumes that MBS issuers followed the former path because “designers of securities will be so concerned with marketability that they will have more than enough incentives to adhere to standards.”Footnote 29

Examining the designs of the different MBS generations led me to a different conclusion about the process by which MBS became accepted as bonds from the standardization accounts found in the existing literature. Specifically, as I argue in the remainder of the article, MBS issuers achieved acceptance for their products by changing the boundaries of the bond category. They accomplished this by introducing mortgage-backed bonds—securities with features that at first closely conformed to those of the bond category. They then gradually added mortgage features to the products while continuing to claim membership in the bond category. I argue that the introduction of multiple generations of these securities over time helped shift the boundaries of the bond category to include MBS.

My work contributes to the existing literature on financial innovation and the innovation literature more broadly by shedding light on the role of customer beliefs in the innovation–acceptance process. Specifically, my work documents the evolving relationship between the design and labeling strategies deployed by innovators and customers’ beliefs. Indeed, my work highlights the importance of language in the innovation–acceptance process. Marc Bloch articulated the historians’ professional frustration that people fail to change their language when they change the meaning of the words.Footnote 30 I find that in the context of innovation, such failure can be strategic in facilitating acceptance of the innovation.

Tracing the Evolution of MBS

My research on the emergence, evolution, and acceptance of MBS as bonds draws on nearly four hundred primary and secondary source documents, which I collected between 2010 and 2016. The data collection for this project proceeded in two stages. I began by interviewing a select group of current and former industry participants and regulators who were involved in the development of the MBS market.

Between 2008 and 2010, I conducted twenty-one semistructured interviews to understand which organizations participated in the evolution of MBS, what roles these organizations played, and how they interacted with each other. In choosing the individuals I interviewed and the organizations they represented, I relied on theoretical sampling, continuing to recruit interviewees until I covered the entire MBS value chain.Footnote 31 To improve my understanding of the decision-making processes of practitioners in the field, I also read ethnographies of financial markets,Footnote 32 transcripts of National Public Radio interviews with mortgage-industry players and consumers, and published practitioner accounts.Footnote 33 I used these materials along with transcripts of my detailed notes from the interviews to compile lists of organizations, individuals, and securities instrumental in the evolution of the MBS market.

In the second stage of document collection, I searched online databases ABI Inform/Global and ProQuest Historical Newspapers, using as keywords the names of the organizations,Footnote 34 individuals,Footnote 35 and securitiesFootnote 36 associated with the development of the MBS market. I also searched WorldCat, an online bibliographic catalog, for manuals, pamphlets, and white papers either authored by or describing the activities of the securities’ issuers, rating agencies, regulators, and industry trade associations. I supplemented my searches of the online databases with reading published academic manuscripts dealing either with MBS directly or the history of mortgage lenders.Footnote 37 I followed the reading by crosschecking the references of these papers against the sources in my document collection and adding the relevant sources to it. When specific industry publications were not available from public sources, I requested copies directly from the authors.

These efforts yielded a collection of 379 publications, including 13 books and 366 industry documents and periodicals spanning the period from 1960 to 2008. The industry documents included prospectuses of individual securities, annual reports of the securities’ issuers and the issuers’ regulators, as well as listings of the individual securities in regulatory filings and rating agencies’ publications. The periodicals section of the document collection includes stories from major newspapers,Footnote 38 general interest business magazines,Footnote 39 magazines focusing on investing,Footnote 40 as well as trade publications for the different industry groups involved in creating, buying, and selling MBS.Footnote 41 The resultant combination of primary and secondary sources enabled me to trace how the investor beliefs and the MBS products evolved from 1970 to 1987.

Specifically, I used these documents to trace the lineage of each MBS product design in order to compare and contrast the features over four generations. To understand these features, I catalogued the six designs of MBS products issued between 1970 and 1983 (the study period), with the sixth finally accepted as a bond by the bond investors. Because I am interested how the evolution of MBS shifted the boundaries of the bond category, I also include a seventh design, which was launched in 1987 after the bond category expanded to include MBS. I examine these seven designs, their features, how each design differed from its predecessor, and the resultant products’ appeal or lack thereof to bond investors and mortgage lenders.

My findings suggest that the MBS issuers succeeded in part due to their reliance on a process complementary to Bloch’s articulation of how word meanings change.Footnote 42 In the case of MBS, the change in the meaning of the word “bond” was a result of continuously labeling MBS as bonds while changing the attributes of the products to include more mortgage attributes. After sketching out the background for the emergence of MBS between 1960 and 1970, I make the case for a change in the meaning of the bond category. I first present the historical narrative as if such a change had not taken place and highlight the questions such a narrative would leave open. I then present the more complete historical narrative with evidence of change in the meaning of the category.

From Mortgages to Mortgage-Backed Securities, 1960–1970

Starting in the 1960s, mortgage lenders and government officials charged with housing policy in the United States saw attracting bond investors and, more specifically, pension fund capital to the mortgage market as critical to helping mortgage lenders meet the growing demand for housing.Footnote 43 Pension fund capital was needed in the mortgage markets because without it the markets went through cycles of funding shortages.

This was because cycle after cycle of interest rate increases created the expectation of rising interest rates, which drove investors out of the mortgage market, thus grinding residential mortgage lending to a halt.Footnote 44 This expectation triggered investor flight from mortgages because investors did not want their money locked-up in the then predominant long-term fixed-interest-rate mortgages, which, after interest rates went up, would pay lower interest rates than other securities in the market. The investor flight left mortgage lenders with limited capital for financing residential mortgages, thus making housing credit unavailable to consumers. This flight from the mortgage market would eventually lead to the Savings and Loan crisis in the late 1980s–early 1990s.Footnote 45

Mortgage lenders and government officials believed that the mortgage investors’ sensitivity to fluctuations in interest rates was due to the their short-term investment horizons. The solution to this problem was seen in attracting new investors with longer time horizons who would thus be less sensitive to interest rate fluctuations.Footnote 46 Pension funds’ long investment horizons made them less sensitive to interest rate changes,Footnote 47 and their access to large sums of capital made them ideal candidates for remedying mortgage-funding shortages.

However, pension funds resisted investing in mortgages because they viewed mortgages as inferior investments compared to bonds, the securities into which pension funds traditionally invested.Footnote 48 The smaller denominations of mortgages meant that bond investors had to buy a greater number of mortgages than bonds in order to invest the same amount of money. Buying more securities involved more effort that translated into higher staffing costs per dollar invested.Footnote 49 The credit quality of individual mortgage loans was also hard to analyze because in lieu of an explicit credit rating, each mortgage included a voluminous file of documents, the contents of which varied from loan to loan. Moreover, the mortgage loan buyers were responsible for collecting the principal and interest payments from the end mortgage borrowers—a responsibility the pension funds viewed as inconvenient.

By contrast, bonds came in large denominations, had easy-to-understand credit ratings, and standardized documentation. Bond investors also received the interest and principal payments from the bond issuers without having to invest in a separate payment–collection function. Pension funds resisted the mortgage lenders’ sales efforts in part because they lacked the capabilities (that is, staff and functional expertise) necessary for investing in mortgages. Pension funds were not willing to make organizational changes and spend money on developing new areas of expertise in order to invest in mortgages.

As a result of these differences between mortgages and bonds, the efforts to frame mortgages as either an attractive investment from an economic perspective or a way for pension funds to fulfill their social obligations fell on deaf ears.Footnote 50 The cost differential between investing in mortgages and bonds translated into a lack of liquidity in the mortgage markets that mortgage lenders and government officials sought to remedy.

The Kaiser Commission, appointed by President Lyndon Johnson in 1968 to analyze the problems of financing housing, described the problem of selling mortgages to investors as follows:

A mortgage is not the most appealing investment to many investors. Often it is not easily converted into cash without a substantial discount. ... Mortgages require investors or their servicing agents to have special staffs which add to the cost of investing in them, costs that may prove prohibitive for smaller investors. A Federally guaranteed debenture would overcome all of these problems and prove attractive to all lenders.Footnote 51

In keeping with the commission’s recommendation, the desire to attract bond investors’ capital to the mortgage market led to the creation of MBS, securities that addressed the bond investors’ objections to investing in mortgages directly while channeling money into the mortgage market. The MBS proponents were explicit about the new securities’ purpose: “The new financing device would aim at capturing larger portion of the investment portfolios of pension and trust funds for housing.”Footnote 52 Thus, the creation of MBS was rooted in these efforts to attract pension funds’ capital to the mortgage market. For a timeline of MBS market events, see Table 1.

Table 1 Timeline of MBS market developments

Mortgage-backed securities were created in response to pension funds’ resistance and were designed to address their specific objections to mortgage investing. The groundwork for the creation of new securities was laid in the 1968 Housing and Urban Development Act, in which Congress authorized (quasi-) government agencies to issue, and government agencies to guarantee the repayment of, certain types of MBS, thus making MBS more attractive to the bond investors. The act split the activities of the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA, or Fannie Mae), the government agency charged with buying mortgages from mortgage banks, into a new federal agency called the Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA, or Ginnie Mae). It then spun off the remainder of Fannie Mae as a private corporation with a congressional charter. Both Fannie Mae and Ginnie Mae were authorized to issue mortgage-backed securities, and Ginnie Mae was also authorized to provide federal guarantees to securities issued by (quasi-) government agencies, including Fannie Mae and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC, or Freddie Mac).Footnote 53 The federal government’s guarantee of MBS repayment enabled MBS issuers to claim that MBS were comparable to government bonds and thus should be treated as such.Footnote 54

Between 1970 and 1983, MBS issuers pursued two different approaches to convince bond investors to invest in MBS—one entailed bringing the design of MBS closer to that of bonds and the other focused on expanding the boundaries of the bond category to include products that incorporated mortgage features. To showcase the differences between the two approaches, I first discuss the evolution of the market as if MBS issuers only employed the first approach and highlight the questions that this narrative would leave open. I then present evidence for the combined use of both approaches and show how the incorporation of the second approach into the narrative helps enrich the understanding of the process by which MBS were accepted as bonds. Such exposition provides an opportunity for a counterfactual analysis of the efforts to turn bonds into mortgages and to convince bond investors to accept MBS.

Turning Mortgages into Bonds: Evolution of Mortgage-Type MBS, 1970–1983

In responding to bond investors’ objections to mortgage investing, a range of federal and state laws, regulatory rulings, and consumer preferences constrained mortgage lenders’ ability to redesign residential mortgages. Consequently, instead of changing the features of individual mortgages, in 1970 mortgage lenders responded to bond investors’ objections to the small denomination and complex documentation of individual mortgages by pooling multiple mortgages. They then used these pools to issue pass-through certificates—standardized securities, with the mortgages serving as securities’ collateral. The new securities were called pass-through certificates because they passed through the principal and interest payments from the mortgage borrowers, whose mortgages were pooled, to the investors. Pass-through certificates represented fractional ownership in a pool of mortgages and were guaranteed by GNMA.Footnote 55

Such pooling allowed mortgage lenders to aggregate enough mortgages to match the minimum denomination size of bonds, to which the pension funds were accustomed,Footnote 56 thus removing the bond investor objections to mortgage denomination size and lack of standardized documentation and credit ratings. Also, the servicing of the securities was assigned to a third party, thus obviating the need for the investors to develop a separate payment–collection function.

MBS issuers had high hopes for the prospects of pass-through certificates capturing a share of the bond investors’ portfolios.Footnote 57 Bundy Colwell, board chairman and president of the Colwell Company, at that time the fifth-largest mortgage bank in the United States active in the issuance of pass-throughs, remarked, “More and more, this is the way mortgages will be marketed. They will tap markets, particularly pension funds and other institutions that are not equipped to handle mortgages as such. All they have to do is treat them like bonds.”Footnote 58

Others in the mortgage industry shared Colwell’s enthusiasm for pass-through certificates. Louis Nevins, a director at the National Association of Mutual Saving Banks, described the function of pass-through certificates as follows: “What the security does is to transform the mortgage into a bond-type instrument.”Footnote 59 This suggests that pass-through certificates were the first attempt by the MBS issuers to turn mortgages into bonds.

Despite these claims of similarity of the new securities to bonds, pass-through certificates differed from bonds on three significant attributes. As a result of the securities’ cash flows being closely tied to the cash flows of the underlying mortgages, the new securities retained mortgage features such as monthly payment frequency and uncertainty in when the mortgages backing the securities would be repaid. First, the monthly payment frequency differentiated pass-through certificates from bonds that typically made semiannual interest payments.

Second, the uncertainty in pass-through certificate repayment dates was introduced by a provision in most U.S. government-insured mortgages that borrowers could repay their mortgage loans at any time without incurring a penalty. Such early repayment, also known as prepayment, could occur, for instance, if borrowers chose to refinance their loans. The prepayment risk was a problem because it exposed investors to the possibility that they would not receive the interest for which they had paid upfront when buying the mortgage. This could happen, for instance, if an investor who paid for the mortgage as if payments would be made over the next thirty years, but the mortgage was repaid after only ten years. In this case, investors would have paid for twenty more years’ worth of interest payments than they received. The other facet of prepayment risk was that more such early repayments or refinancings occurred when interest rates went down as compared with when the mortgage was originally issued. This meant that the investors would have to reinvest the repayments they received in a lower interest rate environment than the one in which they had originally invested.

Third, like individual mortgages, pass-through certificates did not constitute a debt obligation of their issuer. In issuing the securities, the mortgage lender sold assets to the investors rather than incur a debt obligation. By contrast, bonds made semiannual payments of interest, returned their principal once at a predetermined date, and were issued as debt obligations.

As the evidence I present below indicates, bond investors’ resistance to accepting new securities focused on the first two issues: the monthly payment frequency and the prepayment risk.

Addressing Beliefs about the Monthly Payment Frequency and Prepayment Risk

Bond investors were reluctant to invest in securities that made monthly payments. Lewis Ranieri, a bond trader who became one of the driving forces behind MBS market development, later recalled:

We created problems for the accountants because the pass-throughs were monthly pay securities and all the other bonds were semiannual. In fact, after John Hancock bought a mortgage security, my customer came back two months later and said, ‘Gee, Lewis, I love this stuff but I can’t buy anymore because my back office is threatening to quit.’ We needed to overcome the bookkeeping inconvenience of a security that paid interest monthly.Footnote 60

As this suggests, even bond investors who could be sold on the idea of MBS were deterred by the mismatch between the securities’ payment patterns and the bond investors’ back office processes. Even the compounding advantage the monthly payment frequency offered over the semiannual payments, that is, the interest would compound twelve times a year rather than only two times was insufficient to overcome the investors’ reluctance to deal with securities making monthly payments.Footnote 61

In addition to payment frequency as a major barrier to the acceptance of pass-through certificates, even mortgage bankers promoting the acceptance of the new securities acknowledged the bond investors’ concerns about prepayment risk. The acknowledgment is evident in the language that mortgage lenders adopted to describe the issue, specifically their use of bond terms such as “accelerated payments” and “call protection” (protection from prepayment risk). Phillip Kidd, the assistant director of research for the Mortgage Bankers’ Association, characterized the problem of prepayment risk as follows:

The only feature the “bond” man looks for today that the mortgage banker [issuing pass-through securities] cannot provide is assurance of call protection. Accelerated cash flows through prepayments and foreclosures can be estimated from FHA statistics, but the bond man would still fear a further acceleration if interest rates fell sharply and borrowers refinanced their mortgages. Neither FHA nor VA [Veterans Administration] mortgages permit a prepayment penalty. Historically, this type of prepayment is rare and a drop so sharp as to induce refinancing in interest rates seems unlikely in the foreseeable future.Footnote 62

Kidd’s characterization suggests that the prepayment risk in pass-through certificates stemmed from a mortgage attribute that pass-through certificates inherited from mortgages and that MBS issuers could not control: the absence of prepayment penalties. Nevins’s analysis echoed Kidd’s description of bond investors’ prepayment risk concerns, suggesting that prepayment risk hindered the acceptance of MBS by the bond investors: “The modified pass-through security is more like a bond than a mortgage, but the holder still has no protection against accelerated payments.”Footnote 63

Thus, the features of pass-through certificates that were closely related to mortgages interfered with bond investors’ acceptance of MBS. The monthly payments of principal and interest posed accounting and back office challenges, which hampered investors’ ability to handle new securities using their existing processes. The combination of monthly payments and prepayment risk made it more difficult to calculate yield, an important metric on which bond investors compare and price securities.Footnote 64 The investors’ inability to compute yield hindered the development of the MBS market because it made it difficult for the investors to buy and sell mortgages. The mortgage securities traders addressed the challenge of computing yield in the presence of prepayment risk by developing industry wide conventions about prepayment expectations.

[One such convention that gained popularity] assumed that no loan [in the pool backing pass-through securities] prepays for the first twelve years, and that one the first day of the thirteenth year, every loan prepays. Everyone understood that the yield produced by this formula could be the real investment yield only by accident. … This formula, which was used for the better part of the decade, was never intended to reflect true investment return. It was simply a convention that enabled Lehman Brothers, Salomon Brothers, Merrill Lynch, and others to compute prices and yields on a consistent basis. It simply enabled traders to talk to each other.Footnote 65

Bond investors rejected pass-through certificates because of these problems; however, traditional mortgage investors familiar with the monthly payment and prepayment risk challenges switched their mortgage investments from buying individual mortgage loans to pass-throughs to benefit from the cost savings associated with the larger denominations, standardized documentation, and government repayment guarantees offered by the new securities. MBS issuers anticipated this development:

Most likely, traditional single-family mortgage investors—mutual savings banks and savings and loan associations—will give the warmest reception to the instrument. These financial institutions already know the drawbacks of direct investment in single-family mortgages—costly review of mortgage documents, loss of income due to long foreclosure litigation, and low liquidity. Moreover, they have lived for years with the problem of reinvesting monthly amortization and know how to tie it into their cash flow needs.Footnote 66

The new securities’ appeal to traditional mortgage investors made their failure to attract new investors even more obvious, leading to a search for other solutions:

The purchase of GNMA securities by [traditional] mortgage buyers has always distressed the architects of the program and the government officials who intended that GNMAs [pass-through certificates] would be used to tap the vast wealth of pension funds. In 1971, many market observers openly charged issuers and dealers with taking the easy way out, selling to the same old mortgage buyers instead of devoting the time and effort required to bring new money into the mortgage market.Footnote 67

MBS issuers responded to the lack of bond investor interest in pass-through certificates by issuing new securities with different attributes and positioning these securities as responding to bond investors’ concerns about investing in pass-through certificates. The evolution of MBS from mortgages toward bonds and how each subsequent generation of mortgage-type MBS became more bond-like in its attributes is shown in Figure 1. The attribute values of pass-through certificates closely matched those of mortgages on the mortgage–bond spectrum.

Figure 1 Turning mortgages into bonds.

Note: Each row in the figure represents a year in which a new type of security was issued. Each column represents a different type of security, with each of the three rows representing the security’s value along the attributes of conventional bonds. The bond values of the attributes are shaded in dark gray, the mortgage values in light gray, and the values between those of bonds and mortgages in medium gray. If a security was discontinued, it was removed from the figure in the years following the discontinuation.

Moving Ever Closer to Bonds

In 1975 the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC, or Freddie Mac), a quasi-government agency created for the purpose of securitizing mortgages, issued the first pay-through certificate, a security structured like a pass-through certificate but with semiannual rather than monthly interest payments.Footnote 68 To switch the securities from monthly to semiannual payments, the securities’ issuers accumulated and reinvested the monthly payments received from the mortgage borrowers before passing the payments on to the investors. The pay-through certificates explicitly targeted bond investors whose accounting systems did not allow them to invest in pass-through certificates.Footnote 69 The switch in the securities’ payment frequency from monthly to semiannually (depicted in Figure 1) made pay-through certificates more like bonds and less like mortgages on the payment frequency dimension, thus becoming another step in turning mortgages into bonds.

Despite Freddie Mac’s success in recruiting Wall Street’s most prominent bond dealers to distribute pay-through certificates,Footnote 70 the new securities failed to generate sufficient bond investor interest to make up for the additional costs incurred by the issuer in transforming the monthly mortgage payments into semiannual payments to the investors. When mortgage origination volumes fell in 1979, pay-through certificates were discontinued.Footnote 71

Undeterred by their lack of success with the first generation of pay-through certificates, in the next generation MBS issuers sought to address bond investors’ objections to the presence of prepayment risk in MBS. They accomplished this through the development of tranching, an approach that divided the prepayments received from mortgage borrowers among different classes or tranches of investors.Footnote 72 Prior to the development of tranching, each pool of mortgages backed a single security with a single stated maturity. This structure, employed in pass-through and pay-through certificates, divided the prepayment risk among the investors in proportion to the size of their investment, with all investors incurring prepayments at the same time.

By contrast, the securities with tranched prepayment risk were designed as multiclass pay-through certificates. This meant that instead of a pool of mortgages backing a single class or tranche of securities, the issuer directed the cash flows from a single pool of mortgages to multiple security classes or tranches with different maturities. To make this structure work, at first, all the prepayments were applied to the outstanding principal of the shortest-maturity tranche until its holders were paid off in full. After that, the prepayments would be applied to the principal of the next-shortest maturity tranche, and so on. In theory, this mechanism offered the longer-maturity tranches a degree of protection from prepayment risk as long as the shorter-maturity tranches remained outstanding.Footnote 73 The multiclass pay-through certificates column of Figure 1 depicts the attributes of these securities.

In 1983, as it was preparing to issue this new type of pay-through certificate, Freddie Mac obtained a letter from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS, the federal agency responsible for tax policy enforcement and interpretation) allowing the agency to issue the new security without exposing security investors to undesirable tax consequences. Originally, both pass-through and pay-through certificates were issued through grantor trusts, which are legal structures that allow the securities to avoid the problem of double taxation. Without grantor trusts, the interest payments on the mortgages could have been taxed twice: once when they were received by the entity managing the security and then again when they were disbursed to the investors. The use of the grantor trust structure, borrowed from inheritance law, was contingent on passive pass-through of the cash flows from the mortgage borrowers to the investors. In other words, the use of the grantor trust structure limited the trustees’ ability to manipulate cash flows. The IRS letter permitted the splitting of the prepayment cash flows among investor tranches without annulling the grantor trust status of the investment vehicle.Footnote 74 However, an hour before Freddie Mac was expected to register the new security with the Securities and Exchange Commission, it received notice that the IRS had withdrawn the letter. Industry participants attributed the withdrawal to the Reagan administration’s desire to take credit for the new security solving the mortgage market shortages.Footnote 75 Specifically, the administration was hoping to take credit for the new security by sponsoring legislation that at the time was titled Trusts for Investments in Mortgages.Footnote 76

The withdrawal left Freddie Mac with three possible courses of action: cancel the issue entirely, proceed with the issuance of the security as designed with investors incurring adverse tax consequences, or change the security design by structuring it as a debt obligation of the issuer rather than as a sale of assets (the typical design of both pass-through and pay-through certificates) to avoid adverse tax consequences for the investors. Freddie Mac had already bought $1 billion worth of mortgage loans in order to issue the new securities, so canceling the issue was not an option. The second option was unlikely to appeal to investors, so it opted for the third course of action.Footnote 77

Laurence Fink, one of the participants in the transaction, later reflected on the ease with which the transformation of the pay-through certificates into debt obligations occurred: “Basically what we did was to take the prospectus, scratch out GMC [Guaranteed Mortgage Certificate, Freddie Mac’s proprietary name for pay-through certificates] and write in CMO [collateralized mortgage obligation].”Footnote 78

Fink’s account is corroborated by the major newspaper coverage of the securities’ transformation. Articles in three major newspapers, reproduced in Figure 2, document the transformation of the security from a pay-through certificate to a collateralized mortgage obligation, occurring in only two weeks’ time.

Figure 2 The timeline of Freddie Mac’s pay-through certificates turning into pay-through bonds.

The May 16 New York Times article in Figure 2 previewed the issuance of a new type of pay-through certificates. The May 17 Wall Street Journal article warned of a one-week delay in the issuance of pay-through certificates to resolve what Freddie Mac termed “technical tax issues.” The June 1 Los Angeles Times article heralded the issuance of collateralized mortgage obligations. Bond investors accepted the resultant CMO securities as bonds. Such acceptance was manifest in the pension funds’ demand for the new securities and the inclusion of CMOs in indexes of corporate bonds, which served as benchmarks for evaluating the bond investors’ performance.Footnote 79 Thus, the bond investors’ acceptance of the 1983 issue of CMOs as bonds marked success for the MBS issuers’ efforts to turn MBS into bonds.

The acceptance of MBS by the bond investors was embodied in investor demand for MBS. By 1991 MBS comprised more than half the assets of an average mutual fund specializing in government bonds.Footnote 80 By 1992 commentators listed MBS as the largest segment of the U.S. bond market.Footnote 81

Making Sense of Mortgage-Type MBS Success

The narrative of mortgage lenders’ success at selling MBS to bond investors presented so far, while linear and accurate, is incomplete. This narrative leaves unanswered questions of interest to scholars interested in the evolution of bond investors’ beliefs with respect to MBS. These questions include: Why were CMOs accepted as bonds despite offering bond investors only tenuous protection from prepayment risk? Why were CMOs accepted as bonds instead of forming their own category of securities? What role, if any, did the seemingly incidental change in the securities’ debt obligation attribute play in the acceptance of CMOs by the bond investors?

In keeping with my focus on the importance of reconstructing the history of innovation acceptance, this narrative can be thought of as what market participants may remember after they accept the innovation.

To gain insight into the questions that the narrative leaves open so far, it is necessary to understand the second approach MBS issuers employed to facilitate the acceptance of MBS by bond investors; namely, the efforts directed at expanding the bond category boundaries outward toward mortgages. I now turn to this task.

Turning Bonds into Mortgages: Evolution of Bond-Type MBS 1970–1983

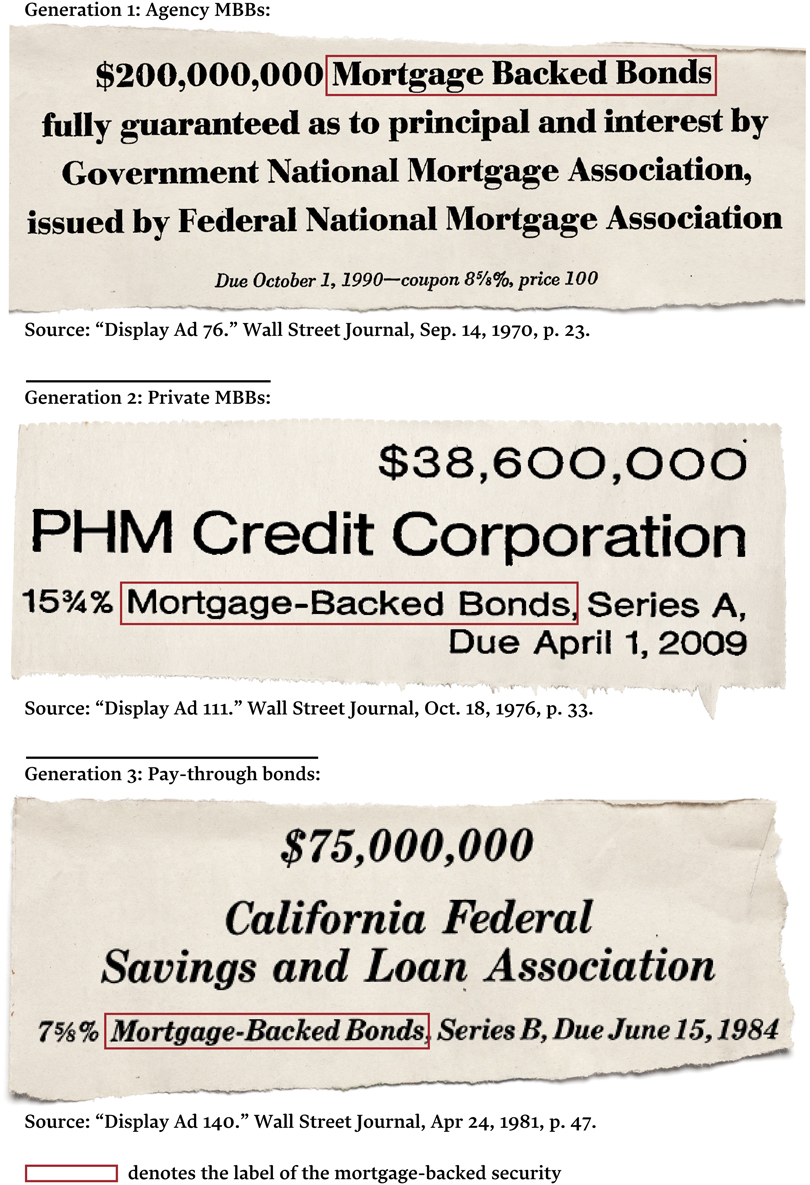

In 1970, in addition to pass-through securities (mortgage-type MBS), the evolution of which was described earlier, MBS issuers also introduced mortgage-backed bonds (MBBs). The features of these securities initially closely conformed to the bond category, which is why I refer to the different generations of MBBs as bond-type MBS. The evolution of these securities alongside mortgage-type MBS is depicted in Figure 3, which also presents the issuance numbers for all seven MBS designs discussed in this article.

Figure 3 Turning mortgages into bonds and turning bonds into mortgages.

* Total issuance divided by the number of years during which the securities were issued.

1 For the period 1970–1982, see Hu (“Secondary Market,” 15).

2 For the period 1975–1979, see Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Secondary Market in Residential Mortgages, 50).

3 For the period 1981–1985, see Sullivan, Miller, and Kiggins (“Mortgage-Backed Bonds,” 159).

4 For the period 1983–1992, this includes the issuance of REMIC and non-REMIC type CMOs; see Kuhn (“Pass up CMO Pass-Throughs,” 23–24).

5 For the period 1975–1984, this number includes both public and private securities issued; see Fisk, Walrath, and Robinson, (“Mortgage Securities Open the Door to Many New Financing Techniques,” 40).

6 For the period 1970–1973, see Ganis (“All about the GNMA Mortgage-Backed Securities Market,” 57).

1970 Generation 1: Bonds with Mortgage Collateral

In announcing the first generation of mortgage-backed securities to the business press, Woodward Kingman, president of the Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA or Ginnie Mae), the federal agency guaranteeing the securities’ repayment, focused on the salience of payment frequency and certainty of repayment timing attributes in making a distinction between two types of MBS (mortgage-type and bond-type):

The first securities to be issued, [Kingman] said, will be of the “pass through” type in which mortgage principal and interest payments are passed through as they are collected to holders of the securities. … Another new type of mortgage-backed security expected from the Federal government is the bond-type security. It is designed, like other bonds, to pay interest regularly and principal at maturity.Footnote 82

Like the pass-through certificates first issued in 1970, bond-type MBS came in larger denominations than mortgages, carried government repayment guarantees, and assigned servicing to a third party, with the latter two features obviating the need for the investors to either analyze the securities’ creditworthiness or create and manage their own servicing functions.

The first generation of bond-type MBS was issued by quasi-government agencies, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and were consequently referred to by market participants as agency MBBs. Agency MBBs were positioned as an attractive option for pension funds interested in mortgage investing. In speaking to the press, the GNMA officials focused on the advantages of investing in agency MBBs as compared with buying mortgages directly: “What makes the bonds more attractive than actual mortgage loans to pension funds, according to GNMA officials, is the absence of a need for the pension funds to service the mortgages—collect monthly payments, and, if the homeowner defaults, foreclose on the loan.”Footnote 83 Agency MBBs were targeted explicitly at bond investors: they bore the mortgage-backed bond label and offered protections from both credit and prepayment risks. The business press echoed GNMA officials’ description of the similarities between agency MBBs and bonds: “Like normal bonds, the new securities will pay interest rates at regular intervals (semiannually) and the principal on the maturity date.”Footnote 84

While both mortgage-type and bond-type MBS were backed by a federal government repayment guarantee, the bond-type MBS was structured in a way that made the issuing agencies responsible for bearing prepayment risk. The investors were protected against this risk unless the agency issuing the security defaulted. By contrast, pass-through certificates transferred the prepayment risk to investors, which meant that the government guarantee in pass-through certificates only covered credit risk (the risk that a mortgage would default), in which case the government would repay the principal of the mortgage.

To further the securities’ similarity with conventional bonds, the agencies issuing bond-type MBS also recruited investment banks to structure and distribute the new securities. This recruitment helped shape technical aspects of the new securities, such as the deal’s cash flows, the amount of collateral used for issuing the agency MBBs, and the price that the issuers charged for the securities. The participation of investment banks in the MBS issuance also had symbolic value: bond-type MBS were structured and distributed by the same actors who structured and distributed conventional bonds. Investment banks became the first bond value chain participants to take part in MBS issuance.

Much work went into issuing bond-type MBS. The agencies designed the securities to address bond investors’ objections to investing in mortgages by making the attributes of the resultant securities match those of conventional bonds. Moreover, the agencies also secured explicit government repayment guarantees, recruited investment bankers, and involved senior government officials in marketing the securities.Footnote 85 The issuers’ hard work to enable the securities’ success notwithstanding, the bond investors’ response to the securities proved discouraging.

Originally, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, at the time both government-sponsored entities (that is, private companies with congressional charters) were authorized to issue the securities and were planning to bring to market MBBs with both short-term (one- to five-year) and long-term (twenty- to twenty-five-year) maturities.Footnote 86 The bond investors bought the short-term MBBs, but the agencies were not able to sell long-term MBBs except at eyebrow-raising losses. Fannie Mae’s issuance of long-term MBBs was first postponed, and then shelved for good.Footnote 87 In discussing one of the few long-term MBB issues that Freddie Mac was able to sell, industry participants were positive that the issue would be sold at a loss:

One incredulous mortgage banker noted privately: “[The interest Freddie Mac was paying to the investors was] more than the yield on the mortgages underlying the [Freddie Mac’s twenty-five-year MBBs] bonds. How can they pay interest they don’t earn?” … No one, including top FNMA (Federal National Mortgage Association, or Fannie Mae) officials who held a directors’ meeting in Miami Beach concurrently with the MBA [Mortgage Bankers’ Association] convention, thought that the FHL Mortgage Corp. [FHLMC or Freddie Mac] could possibly break even on its first offering of mortgage-backed bonds.Footnote 88

The investors’ lack of interest in long-maturity MBBs meant that securities’ issuance failed to solve the problem of attracting long-term capital to the mortgage market. The issuance of short-term bond-type MBS proved impractically costly for the agencies because they could issue non-collateralized short-term bonds without incurring the expense of structuring and maintaining collateral for the securities. Consequently, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac discontinued the issuance of agency MBBs in 1973.Footnote 89

Unlike pass-through certificates, the features of which were closely tied to mortgages, agency MBBs possessed all the attributes of conventional bonds, as depicted in Figure 3, and claimed membership in the bond category by carrying the bond label. Pairing the bond label with mortgage collateral was the first step in opening the boundaries of the bond category to securities with mortgage features. In the ensuing generations of bond-type MBS, the MBS issuers worked to shift the boundary of the bond category further toward mortgages by changing the design of bond-type MBS to make them more mortgage-like while continuing to carry the mortgage-backed bond label and, thus, claiming membership in the bond category.

1975 Generation 2: Bonds with Mortgage Collateral and Prepayment Risk

The agencies’ withdrawal from the issuance of MBBs was driven by a combination of market response to agency MBBs and the impetus for developing private solutions to the mortgage funding problems, which continues to animate U.S. policymaking.

After the agency MBBs were discontinued, private mortgage lenders started issuing their own mortgage-backed bonds. First issued in 1975, private MBBs addressed the bond investors’ objections to investing in agency MBBs by offering securities with shorter maturities than the long-term issues of agency MBBs. Private MBBs’ maturities of eight to ten years fell between the short- and the long-term versions of the first generation of bond-type MBS.Footnote 90 In the words of William Scheu, president of First Federal Savings & Loan of Rochester (New York), one of the first mortgage lenders to issue private MBBs: “The maturity [of private MBBs] and average life happened to fit very well with the requirements of our investors.” Scheu here used the bond term “average life” to refer to the period over which a conventional thirty-year mortgage remained outstanding before it was repaid. The match between the mortgage average life and the maturity of the MBBs meant that the issuance of private MBBs helped the securities’ issuers achieve a match between the duration of their assets—mortgage loans in their portfolios—and liabilities—mortgage-backed bonds.Footnote 91

The issuance of private MBBs required a series of regulatory and institutional changes. The collaboration among mortgage lenders, investment bankers, government regulators, and rating agencies was instrumental in spurring these changes. The following describes the role of the Loeb, Rhoades & Co., an investment bank, in helping bring about such collaboration:

[Loeb, Rhoades had] “already developed its concept for mortgage-backed bonds to the point where it felt it would be acceptable to the Federal Home Loan Bank Board and would meet the requirements being defined for the Board’s [then] proposed mortgage-backed bond regulations,” explained association President Scheu in his case study. “Just as importantly, Loeb, Rhoades had been working closely with Standard & Poor’s rating agency in developing a rationale for rating such bonds. As a result, Standard & Poor’s policy of not rating any security issue of a savings association was modified.”Footnote 92

The change in Federal Home Loan Bank Board (FHLBB) regulations helped bridge the gap between mortgages and bonds by allowing mortgage lenders to issue debt obligations, something mortgage lenders were previously not allowed to do.Footnote 93 Standard & Poor’s decision to rate the resultant securities further legitimated mortgage lenders’ role as bond issuers, marking the acceptance of the mortgage lenders’ new role by yet another group of bond value chain participants, an acceptance that helped further narrow the gap between mortgage lenders and bond issuers.

In switching the type of issuer from quasi-government agency to private firms, MBS issuers changed the template to which the bond-type MBS conformed from that of government bond to that of corporate bond. In practice, this translated into the introduction of credit and prepayment risk into bond-type MBS. Agency MBBs, which were modeled on government bonds, were treated by the markets as not needing a credit risk rating because “it is considered inappropriate to apply a credit rating, which implies a non-zero probability of default to securities issued or guaranteed by the United States Treasury or one of its agencies.”Footnote 94 By contrast, private MBBs, like corporate bonds, were subject to credit risk (the risk of investors not being paid back), so their issuance necessitated credit rating agency participation.

What differentiated private MBBs from both corporate bonds and agency MBBs was the presence of prepayment risk. Like corporate bonds, private MBBs had credit risk. However, unlike most corporate bonds, private MBBs had collateral, the existence of which translated the presence of the credit risk in the securities into the presence of prepayment risk. This was because a default of the issuer could trigger the sell-off of the collateral to pay off the bondholders before the bonds were due.Footnote 95 While agency MBBs in theory could have had this problem, government repayment guarantees effectively took care of the issuer-default scenario, thus protecting the investors from prepayment risk.

Bond investors were wary of private MBBs because they were not familiar with the credit quality of the mortgage lenders issuing the securities.Footnote 96 Private MBBs issuers attempted to make up for this lack of familiarity and concerns about prepayment risk by overcollateralizing the securities they issued by 75 percent to 100 percent and replenishing this collateral as mortgages were paid off. This meant that the issuers had to provide up to twice as much collateral as the amount of the bonds that they were issuing.Footnote 97 Mortgage lenders’ willingness to do this won over the rating agencies, which assigned the highest credit rating to the new securities, but failed to sway most bond investors. Despite the changes in the securities’ design to address bond investors’ objections to the length of the securities’ term and concerns about the mortgage lenders’ credit-worthiness, bond investors continued to reject mortgage-backed bonds as an investment vehicle.Footnote 98

As noted earlier, private MBBs addressed the bond investors’ objections to the long maturity periods of agency MBBs, and the recruitment of credit agencies furthered the similarity between private MBBs and corporate bonds. However, even as these changes made the securities more appealing to bond investors, the securities also increased the investors’ exposure to prepayment risk, thus simultaneously moving the securities closer to the position of mortgages along the prepayment risk dimension.

The change in the type of issuer took the value of the prepayment risk attribute from an outright “No” in agency MBBs to a conditional “No, if the issuer is solvent” in private MBBs. Despite introducing prepayment risk into bond-type MBS, private MBBs retained the “mortgage-backed bond” label. The private MBBs’ issuance introduced the notion that a security could combine the bond label with exposure to prepayment risk, thus moving the securities closer to mortgages on the mortgage-bond spectrum. This introduction took MBBs another step in the journey toward making bonds more mortgage-like (see Figure 3).

The acceptance of private MBBs was hindered by bond investors’ lack of familiarity with the mortgage lenders’ credit quality and the bond investors’ perception of the overcollateralization and collateral replenishment provisions as insufficient to make up for these concerns. While bond investors were concerned about the quality of private MBBs, the securities’ issuers were dissatisfied with having so much of their loan portfolios tied up in overcollateralization.

1981 Generation 3: Bonds with Mortgage Collateral and Prepayment Risk Issued by Shell Corporations

Pay-through bonds, the third generation of bond-type MBS, first issued in 1981, attempted to address both investor and issuer concerns. Investment bankers described pay-through bonds as a hybrid of bond-type and mortgage-type MBS.Footnote 99 Pay-through bonds were issued as debt obligations but passed the mortgage prepayments to the investors as they occurred. In the previous MBB design, the mortgage lenders replenished the securities’ collateral as mortgages were paid off, thus, at least in part, protecting the investors from prepayment risk. However, the design of pay-through bonds addressed the bond investors’ concerns about the mortgage lenders’ credit quality by legally separating the mortgage lenders’ finances from the securities’ collateral.

This separation meant that instead of issuing the securities directly, the mortgage lenders set up shell corporations and transferred the mortgage loans, constituting the securities’ collateral, to these entities. The shell corporations issued the securities and transferred the proceeds from securities’ issuance to the mortgage lenders as payment for the mortgage loans in the collateral. The legal separation between the mortgage lenders and the shell corporations, holding the pay-through bond collateral, meant that the mortgage lenders could no longer replenish the securities’ collateral as the borrowers paid off the loans. The mortgage lenders’ inability to replenish the collateral translated into the full transfer of prepayment risk associated with the mortgage loans in the MBBs’ collateral to the investor.

Thus, the efforts to address bond investors’ concerns about the credit risk associated with the MBBs triggered two changes in the attributes of MBBs. The first was that the securities now fully transferred the prepayment risk associated with mortgages in the securities’ collateral to the investors. The second was that the use of shell corporations diluted the meaning of the debt obligation attribute. As a result of these changes, the attributes of pay-through bonds approached those of pay-through certificates (see Figure 3). The new securities carried more prepayment risk than their predecessor bond-type designs; were issued as debt obligations of shell corporations rather than of mortgage lenders; and some issues even featured monthly payment frequencies typical of mortgages, rather than semiannual payment frequencies of bonds.

Like the predecessor bond-type securities, the pay-through bonds also helped shift the boundary of the bond category closer to MBS by retaining the bond label, despite acquiring more mortgage features. Marc Bloch famously observed: “To the great despair of historians, men fail to change their vocabulary every time they change their customs.”Footnote 100 In case of the evolution of MBS, failure to change the vocabulary that described the different generations of mortgage-backed bonds was strategic. In mortgage lenders’ trade publications, the MBS issuers referred to different generations of MBBs by the securities’ trade names, cautioning the readers not to confuse the different security types. For example, one commercial banking textbook warned: “There are two types of bonds backed by mortgage loans and they should not be confused. This section deals with the mortgage-backed bond [private MBB] while the pay-through bond is covered in the next section.” Footnote 101 By contrast, in marketing the securities to investors, the issuers consistently used the same label to present all three generations of the bond-type securities. Excerpts of tombstones—advertisements for the three generations of MBBs—are reproduced in Figure 4. Note the use of the same “mortgage-backed bond” label in all three generations of MBBs.

Figure 4 The use of “mortgage-backed bonds” label in marketing three generations of bond-type MBS (1970–1981).

In labeling MBBs, the issuers deployed two different strategies. They changed the securities’ trade names to communicate the differences in the different generations of securities to the trade insiders. However, they preserved the same label when presenting the securities to the general public. The disconnect between the two labeling strategies suggests that the MBS issuers strategically used the “mortgage-backed bond” label to change the meaning of the bond category and thus to expand the category’s boundaries.

The pay-through bonds did not achieve commercial success, despite addressing some issuer concerns and the needs of some bond investors.Footnote 102 However, the use of the bond label in pay-through bonds shifted the perception of what it meant to be a bond. As the quote below suggests, by the 1980s market participants saw the differences in the debt obligation attribute as the only remaining difference between mortgage-type and bond-type MBS and, by extension, between mortgage-type MBS and bonds: