Introduction

In a 1939 letter written to Detroit Housewives League president Christina Fuqua, local merchant Lincoln Gordon recognized “the ability of the Housewives League to boost race business.” Gordon manufactured a household cleaning product called Gordon’s Quality Cleanser, a mineral water softener and solvent, and he wanted the League’s help in boosting sales. He wrote, “I shall be very pleased to have this body of business makers select or recommend to me [agents and consumers].” Gordon assured Fuqua, “As far as it is possible, I shall function for the mutual benefit of business for the race.” Lincoln Gordon closed his letter by letting Fuqua know that he subscribed to the League’s principles, asserting, “This is a written statement to display my willingness to cooperate and promote a bigger and better Racial Business.”Footnote 1 As an up-and-coming entrepreneur, Gordon acknowledged that the women of the Detroit Housewives League were important leaders in Detroit’s black business community.

Figure 1. Joint organizational letterhead ca. 1933. Courtesy of the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.Footnote 42

Figure 2. Bristol & Bristol Advertisement featuring photographs of Vollington and Agnes Bristol.Footnote 69

Figure 3. Helen Malloy working in the family business. Courtesy of the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.Footnote 78

Figure 4. Grocery store advertisement noting Bertha Gordy as the proprietor. Courtesy of the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.Footnote 86

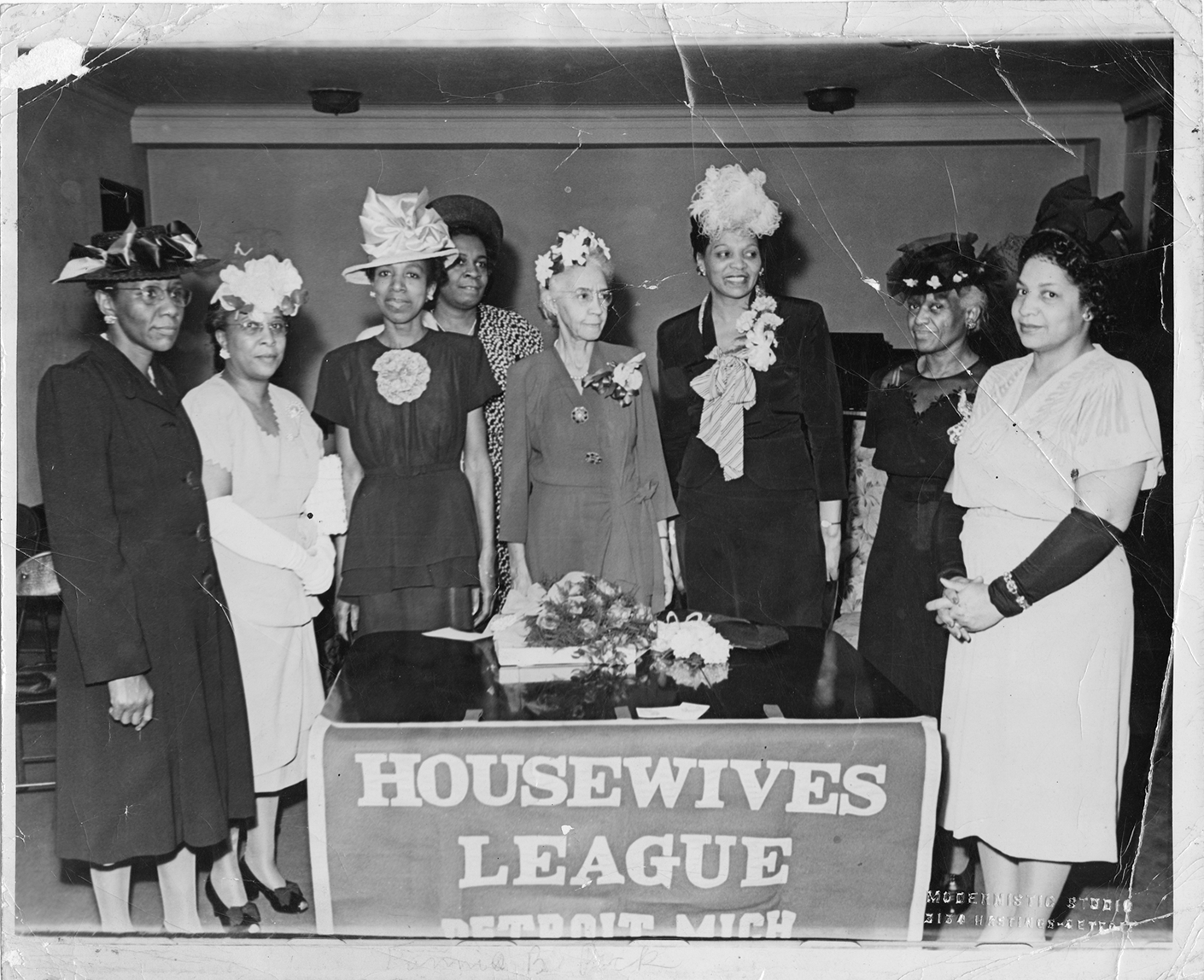

Figure 5. Members of the Detroit Housewives League. Violet Lewis is third from the right. Courtesy of the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.Footnote 167

In the 1930s and 1940s, the Detroit Housewives League (DHL) and the Booker T. Washington Trade Association (BTWTA) were dedicated to enriching local African American business in Detroit, Michigan, through commercial efficiency, networking, employment, and education.Footnote 2 Unlike other organizations that focused on a specific industry such as beauty culture, banking, or real estate, these partner organizations were established to promote black business more broadly. In reframing the Detroit Housewives League as a business-centered organization, I posit that DHL members were pioneers in black women’s business organizing.

Historians have not depicted the Detroit Housewives League as a business organization, and previous scholarship has not emphasized the centrality of black women entrepreneurs to the DHL and the success of Detroit’s black business community. One reason for this omission is that most historical discussions uncouple the Detroit Housewives League from its partner organization, the Booker T. Washington Trade Association. This disconnection is partly due to the physical separation of the organizations’ papers in the archive.Footnote 3 Still, many items in the DHL’s manuscript collection, especially those dating from the earliest decades of the DHL’s existence, were jointly produced by both organizations. There are also numerous items in the collection that were created under the auspices of the BTWTA but whose authors or compilers, upon closer inspection, were members of the Detroit Housewives League. Moreover, DHL women participated in obscuring their entrepreneurial backgrounds by choosing the name “Housewives League” for their organization.

Examining the Detroit Housewives League through its partnership with the Booker T. Washington Trade Association facilitates a deeper understanding of DHL women’s actions and philosophy. Black women were not simply involved as wives, mothers, or consumers concerned with their households but were entrepreneurs and business experts in their own right. Analyzing DHL members as businesswomen and focusing on their entrepreneurial activities demonstrates both that they were engaged in Detroit’s black business development all along, and they were instrumental in generating the business information and networking structures that would allow the black business community to not only survive the Great Depression but also continue to grow into one of the most prosperous African American business communities in the 1940s.

Another major reason the Detroit Housewives League has not been regarded as a business organization is that scholars tend to frame the DHL as an extension of the black women’s club movement or as part of the women-driven consumer movements of the 1930s and 1940s, particularly highlighting the organization’s philosophies on black women’s purchasing power.Footnote 4 Both Darlene Clark Hine and Victoria Wolcott maintain that in forming the organization, DHL leaders drew on their past experiences and organizational skills as middle-class women with ties to Progressive Era activism.Footnote 5 Certainly there was overlap, as many DHL members were involved with organizations that were part of the Michigan State Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. For example, DHL member Rosa Slade Gragg served as president of the Detroit Association of Colored Women’s Clubs and later as president of the National Association of Colored Women (she was also an entrepreneur and established a trade academy in Detroit).Footnote 6 Wolcott builds on Hine to further emphasize the working-class component of DHL’s membership, framing the organization as a “more popular and broad-based movement.”Footnote 7 However, key DHL leaders also had entrepreneurial experience prior to forming the Detroit Housewives League. I argue that entrepreneurial DHL women brought this business knowledge to their organizing and were significant black business experts and leaders.

Previous histories have deemed the DHL’s primary purpose as organizing women’s spending power and working to empower and educate black women consumers. According to Wolcott, “recognizing the powerful role that African American women played in business as consumers,” DHL founder Fannie Peck “issued a call for interested African American women to join her in forming a sister organization to the Trade Association.”Footnote 8 This statement corresponds with scholars’ tendency to link the Detroit Housewives League to consumer activism in this period. DHL women did engage in this type of activism. In fact, Fannie Peck was inspired to create the organization after learning that housewives in Harlem had collaborated with the Colored Merchants Association (CMA) on spending initiatives.Footnote 9 Nevertheless, the organization’s main goals were to boost and build black business, which they did through a variety of means.

There are noteworthy differences between the DHL’s appeal to consumers and the work of other black women consumer activists. Other black consumer activism often took the form of “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaigns that sought to leverage black buying power to contest racist hiring practices in white-owned companies. Unlike “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaigns, the Detroit Housewives League and the Booker T. Washington Trade Association did not focus their efforts on getting white-owned businesses to hire blacks or improving white stores’ treatment of African Americans.Footnote 10 According to Helen Malloy, longtime member, onetime DHL president, and the organization’s historian, “We never said don’t patronize whites.”Footnote 11 The DHL’s actions and philosophy regarding women’s purchasing power fit into the category of a buycott. A consumer buycott is the opposite of a boycott, as boycotts often seek to punish businesses for past wrongs, whereas buycotts aim to reward them for good deeds.Footnote 12 The Detroit Housewives League did not openly advocate boycotting white-owned businesses, but rather encouraged spending in black businesses. In their principles and bylaws, the DHL declared, “We are not engaged in any efforts of protest against business operated by other racial groups that may have a large percentage of Negro patronage. We feel that OUR BUSINESS is to support our own.”Footnote 13 Both the DHL and BTWTA believed that “to throw support to Negro business in this way is a duty we owe the race. It is not a form of boycott against other groups. It is a legitimate and essential act of self-preservation.”Footnote 14 They encouraged the “double duty dollar” as part of consumers’ pledge to support black-owned businesses, and reasoned that the entire black community would benefit from this type of spending—consumers procured the goods and services they needed and their dollars would strengthen black-owned businesses.Footnote 15

It is crucial for scholars to recognize the distinction between the DHL’s actions and other types of consumer activism. Although it is true that members of the DHL did engage in consumer activism and some were involved in black clubs, framing the DHL as an outgrowth of either Progressive Era women’s clubs or 1930s and 1940s consumer movements pushes DHL women’s role as entrepreneurs, business experts, and producers of economic knowledge into the background. As the case of the Detroit Housewives demonstrates, black businesswomen are sometimes obscured in the accounts of other economic, political, and social organizing. I suggest that reevaluating other histories of women's activism has the potential to reveal more insight on black women’s entrepreneurship and business leadership. Additionally, by looking for hidden black female entrepreneurship, scholars might uncover deeper layers of black women’s strategies and contributions to activism in the early civil rights era. For example, the DHL continued to underscore boosting black business in the 1940s and 1950s, a time when many organizations emphasized integrating industry and obtaining employment for blacks in white-owned businesses.

In this article, I posit that Detroit Housewives League members were pioneers in black women’s business organizing. The DHL became a model for the National Housewives League, which was formed in 1933 in direct response to the success of the Detroit league.Footnote 16 Although other black female business organizations existed prior to the DHL, they tended to focus on a specific industry. In contrast, black women in the DHL organized to stimulate black business more broadly. Entrepreneurial DHL women came from a range of fields, and their knowledge and connections led to the Detroit Housewives League being a driving force behind the rise of Detroit’s African American business community in the 1930s and 1940s.

Launching the BTWTA and DHL: The Great Migration, the Emergence of Detroit’s Black Business Community, and the Great Depression

Between 1910 and 1970, more than six million African Americans left the U.S. South. This Great Migration had a transformative demographic impact on Detroit and black business in the city. In January 1914, Henry Ford made his famous offer of five dollars a day for unskilled laborers in his automobile factory in Highland Park, Michigan, just outside Detroit. This was a substantial amount of money at the time—more than most black workers had ever dreamed they could earn—and Ford’s offer drew workers from all around the world.Footnote 17 During the Great Migration years, Detroit as a whole was experiencing a boom. In 1910, Detroit had a total population of 465,766. This grew to 993,675 in 1920 and 1,568,662 by 1930. Detroit developed a reputation as a city of unsurpassed economic opportunity, and migrants came with the hope that they could make good in this flourishing northern city.Footnote 18 Although cities like New York and Philadelphia had longstanding and sizable black communities before the Great Migration, Detroit had a small black population, little more than 1 percent of the city’s total population. However, between 1910 and 1920, Detroit’s black population increased by 611 percent, more than any other major city in the United States.Footnote 19 In 1925, the number of blacks living in Detroit was 85,000, and by 1930 this had increased to 120,000. In 1940, the total had jumped to nearly 150,000. By June 1943, between 190,000 and 200,000 African Americans lived in the Motor City. In 1950, there would be more than 300,000 blacks in Detroit.Footnote 20

The boom in Detroit’s black population created distinct opportunities for African Americans to pursue business. It created a sizable black consumer base and made Detroit an extremely attractive place for southern migrant entrepreneurs. High wages in the automotive industry nurtured the black business climate by increasing black industrial laborers' wages and their families’ disposable income. Black laborers settling in Detroit needed goods and services, and black business owners could provide these things, especially in fields in which whites were not willing to serve black customers. The large increase in Detroit’s black community meant that consumers could support black entrepreneurs operating in a wide range of business sectors.Footnote 21 Detroit’s black business community developed quickly, particularly in the Black Bottom neighborhood where many migrants settled. In the decades that followed, Detroit’s black business community, made up mostly of southern migrants, grew to become one of the largest in the country.

However, all was not rosy for the growing black migrant community or for black entrepreneurs who established businesses in the city. As Detroit’s black population increased, the race line hardened and African Americans’ presence was met with hostility from whites. In 1920, Forrester B. Washington, the first director of the Detroit Urban League, noted that the influx of blacks prompted “the growth of race prejudice on the part of white people.”Footnote 22 Racial prejudice and tensions took many forms, including police harassment, destruction of black property, and mob violence. In the 1920s, when black entrepreneurs sought to build a business community, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was experiencing a rebirth in midwestern cities, including Detroit. By 1924, Detroit’s KKK had 35,000 members.Footnote 23 However, antiblack attitudes spread beyond the Klan. White shopkeepers increasingly banned black customers from their stores and restaurants. Moreover, white real estate agents refused to show houses in white neighborhoods to African Americans, bankers declined to offer them mortgages, and insurance agents would not provide them with coverage.Footnote 24 Whites in Detroit and other northern cities also used discriminatory real estate practices such as restrictive covenants to keep blacks out of white neighborhoods.Footnote 25 Although increased segregation created less competition with whites and enabled black entrepreneurs in Detroit to grow their businesses, it also created a hostile environment.

Heightened racial tensions directly impacted black business owners and professionals. A notable example is Ossian Sweet, a Detroit doctor originally from Bartow, Florida, who purchased a home in a white neighborhood in 1925. Sweet was attacked by a white mob and later charged with murder after acting in self-defense. Sweet was not the only black entrepreneur to experience racial violence in the 1920s. Earlier in 1925, several other prominent black entrepreneurs also experienced violent responses to their arrival in white neighborhoods.Footnote 26 One of these incidents involved Agnes and Vollington Bristol, a married couple who would later become leaders in the Booker T. Washington Trade Association and Detroit Housewives League.

Agnes and Vollington Bristol operated the Bristol & Bristol Funeral Home and owned multiple residential properties. In July 1925, the Bristols rented a house that they owned (but did not live in) to a black couple, who subsequently received threatening notes. When Vollington Bristol arrived at the property, a delegation of twenty-five white neighbors warned him not to rent to black tenants anymore. After the encounter, the Bristols decided to move into the house themselves. The next day, a white mob formed outside their house and began stoning the Bristol home and firing guns. Police were able to disperse the crowd, but tensions in the area remained high for several days, and the Bristols continued to face death threats and hostile encounters with whites until they moved out of the neighborhood.Footnote 27 The cases of Ossian Sweet and Agnes and Vollington Bristol exemplify the physical violence and threats that black entrepreneurs experienced for buying property in segregated neighborhoods.

There were other forms of racial hostility and discrimination as well, and Detroit’s black entrepreneurs had to overcome a variety of obstacles in order to run profitable and long-lasting businesses. In fact, black entrepreneurs experienced discrimination at almost every stage of business, including exorbitant rents for retail space, difficulties obtaining loans from white banks, and problems receiving licenses from state regulatory agencies. They also encountered geographical restrictions—white Detroiters denied black entrepreneurs access to downtown locations, where other racial and ethnic groups were allowed to set up business.Footnote 28

The depressed economy of the 1930s exacerbated this discriminatory business climate. The Great Depression hit the Motor City especially hard because consumers across the country had less money to spend on luxury items like automobiles. Hundreds of factories were forced to close, and black industrial workers especially suffered widespread unemployment because African Americans tended to be the last hired and first fired.Footnote 29 Black business owners relied on black wage laborers as patrons. Consequently, as unemployment rates increased, black entrepreneurs’ profits declined. In 1930, 60.2 percent of Detroit’s black male workers were unemployed—nearly double the 32.4 percent unemployment rate for white male workers. The unemployment rate for black female workers was a staggering 75 percent, compared with 17.4 percent for white female workers. Black unemployment rates in Detroit were higher than in the Great Migration centers of Manhattan (25.4 percent for black males and 28.5 percent for black females) and Chicago (43.5 percent for black males and 58.5 percent for black females).Footnote 30 Additionally, during the Depression, domestic work became increasingly scarce and paid less. Domestic workers’ wages stagnated or dropped to as little as one dollar a day in the 1930s.Footnote 31 These trends in domestic labor likely drew more black women in Detroit toward entrepreneurship.

The economic downturn pushed African American entrepreneurs toward a variety of survival strategies. A key strategy was forming organizations to promote black self-help and boost black business. This strategy was indicative of a strong organizational impulse in black Detroit. During the 1910s and 1920s, African Americans involved with churches, clubs, fraternal orders, and the Detroit Urban League helped foster community and garnered communal power in their attempts to shape the economic trajectory of the city’s expanding black population. In the early 1930s, the efforts of newly formed black business organizations helped alleviate black entrepreneurs’ economic suffering and were crucial to maintaining Detroit’s business community in a time of economic crisis. The Detroit Housewives League and the Booker T. Washington Trade Association were the largest and most influential of these organizations.

Reverend William H. Peck was the driving force behind the Booker T. Washington Trade Association. As pastor of Bethel AME Church in Detroit, Rev. Peck felt the need to do something about the negative effects the Great Depression was having on his two thousand–member congregation. Unemployed laborers were struggling to survive without work, and black entrepreneurs were fighting to remain in operation. After discussing this predicament with his wife, Fannie B. Peck, the pastor decided that Detroit needed a black business organization. In April of 1930, Rev. Peck called a meeting of black business owners and professionals and formed the Booker T. Washington Trade Association.Footnote 32

Fannie Peck was involved in the BTWTA from its inception.Footnote 33 According to an organizational history, after Rev. Peck proposed the idea of a business organization over breakfast, Fannie Peck voiced her support and replied, “You may depend on me doing my part.”Footnote 34 Two months after the BTWTA’s first meeting, Fannie Peck issued her own call, and on June 10, 1930, a group of fifty black women gathered to establish the Detroit Housewives League, an organization to foster self-help and build black economic institutions in the community.Footnote 35 The DHL grew to have 10,000 members by 1935 and several neighborhood units within the city that belonged to the Central Committee.Footnote 36 The BTWTA and the DHL were established as partner organizations and remained intertwined throughout the 1930s and 1940s.

The two organizations made their partnership explicit, regularly referring to the BTWTA and DHL as a pair and offering unified messages and goals. They jointly published several periodicals including the Detroit Economist, which specified that its contents reflected “the interest of the Booker T. Washington Trade Association and the Detroit Housewives League.”Footnote 37 Their annual directory of black businesses stated, “The Booker T. Washington Trade Association and the Detroit Housewives League are endeavoring to bring together in this little book the names, location[s] and telephone number[s] of those men and women who are engaged in business and the profession[s].”Footnote 38 The organizations also had a General Council composed of elected officers from both groups. Its objective was to unify the programs, operations, and plans among the BTWTA and the different units of the DHL throughout the city, and “to agree upon united actions for furthering of the work.”Footnote 39 Together, the BTWTA and DHL sponsored annual trade exhibits, business booster drives, educational events for entrepreneurs and consumers, and a general “program of support and improvement of Negro business.”Footnote 40 The DHL rejected the idea that it was an auxiliary organization of the BTWTA. Rather, according to member Helen Malloy, they felt that the two groups were “like husband and wife,” equal parts of a whole.Footnote 41

The BTWTA acknowledged women’s significant role as business leaders and experts in the community and their participation in the organization itself. For example, when promoting the organization’s 1933 Spring Drive—an event to help black businesses “get a larger share of the general business in the metropolitan area of Greater Detroit”—BTWTA president Rev. William Peck stressed, “We can carry out this order only through the cooperation of our Business, Artisan, and Professional men and women.”Footnote 43 The 1933 directory characterized the BTWTA as “an organization of Business and Professional men and women organized to stimulate and improve their business.”Footnote 44 Therefore, the BTWTA appointed chairmen for different industries, such as insurance, laundry products, and beauty manufacturing, with whom business owners could consult. Despite using the term “chairmen,” the role was filled by both men and women.Footnote 45 As black women dominated the beauty industry, certainly a female entrepreneur would have been appointed as chairman for this field. In addition, the BTWTA’s weekly Luncheon Club presented lectures from prominent business leaders, “men and women of high standing,” and the club’s membership was “made up of persons who are actually engaged in business professions of some sort.”Footnote 46 As one member highlighted, “Over a plate of food or cup of coffee we have been able to learn [from] the real men and women” in the business community.Footnote 47 This indicates that black women were not only operating local businesses but were also members of the Booker T. Washington Trade Association. An advertisement for the 1944 BTWTA membership drive stated, “Every woman and man interested in a business profession should carry a membership.”Footnote 48 The DHL had male members as well; Willis Eugene Smith, a mortician and funeral director, was a member of both the BTWTA and the Detroit Housewives League.Footnote 49 The BTWTA published the Voice of Negro Business monthly, yet Helen Malloy was the publication’s editor and its executives included a woman, Gonzella Porter, who later became chairman of the BTWTA Membership Committee.Footnote 50 Thus, the two groups were not only partner organizations with a shared vision for Detroit’s black business community, but were also interconnected in terms of leadership, programming, and membership.

Even though many were leaders in the black business community, the DHL founders’ decision to use the term “housewives” in the title of the organization helped obscure black women’s business leadership and activism. The name “Housewives League” is a misnomer, as most DHL members worked outside of the home. Certainly, some members of the DHL identified as housewives, but the gendered culture of the time also influenced the naming of the Detroit Housewives League. Victoria Wolcott notes that “the feminine nature of the league’s work, the emphasis on women’s roles as consumers, marked the movement as ‘respectable’ in spite of its militant tactics.”Footnote 51 In the early twentieth century, middle-class black women often espoused a politics of respectability as a strategy to navigate the racism and sexism in their lives.Footnote 52 To combat negative stereotypes of black women, middle-class leaders endorsed the popular belief that women were more nurturing, moral, and altruistic than men, and that women were better suited for social welfare work because men’s nature was selfish and aggressive.Footnote 53 Women embodying characteristics like assertiveness, ambition, or shrewdness in business did not fit into this model. Respectability politics also shaped the way black women could enter into public space and lead on public platforms, limiting how they could lay claim to public business leadership roles.Footnote 54

Anxieties about how black businesswomen would be viewed or treated by men in their community were real concerns in the 1930s and 1940s. DHL member and entrepreneur, Violet T. Lewis, experienced firsthand the issues that could come with being a successful entrepreneur and prominent female business leader. Lewis’s business success and stature were direct factors in the breakup of her marriage. According to Violet Lewis’s daughters,

Daddy was married to a woman with a strong personality. Not having a comparable or complementing personality, Daddy’s ego could not endure his perceived subservient role in the marriage. The more mother grew in stature in the community, the more successful her business became, the more she became empowered, the less Daddy felt like a partner in her success. Mother tried to be inclusive and Daddy tried to support her, but he was always playing the second role and people rarely asked or knew about Mr. Lewis.Footnote 55

DHL women likely obscured their entrepreneurial prowess, perhaps to help their spouses save face or because it was necessary to placate businessmen in the community. Calling themselves “housewives” even when they were entrepreneurs could have protected business-minded DHL members from inter- and intra-racial social backlash and provided them with political, social, and economic benefits. Nevertheless, by choosing the name “Housewives League” for their organization, entrepreneurial DHL women facilitated the erasure of their business backgrounds and expertise from historical narratives.

Entrepreneurial “Housewives”: DHL Women’s Business Expertise

The Detroit Housewives League was not the first local organization to bring black businesswomen together to advocate for their own entrepreneurial interests. In September 1928, two years before Fannie Peck launched the DHL, black women who worked in Detroit’s black business and professional offices established the Elliotorian Business Women’s Club (EBWC). The EBWC was the first women’s club in Michigan to focus solely on African American businesswomen. Its leader, Elizabeth Nelson Elliot, was a secretary who realized that black women secretaries, bookkeepers, and clerks needed more support in order to fulfill their potential of becoming a “viable community force.” She also wanted to encourage young women to enter business careers.Footnote 56 The EBWC’s goals were to “stimulate interest” in Detroit’s businesses, build an educational program, study businesswomen’s needs, develop leadership qualities, and facilitate professional women’s entry into public and private white-collar occupations.Footnote 57 By 1931, EBWC had 33 members (all women, some of whom were also DHL members) and 118 patrons, prominent leaders who supported the organization but were not official members. These patrons included several people who were involved in the newly established DHL and BTWTA. In 1936, William and Fannie Peck became Elliotorian patrons while simultaneously leading the BTWTA and DHL.Footnote 58

These links between the DHL and the Elliotorian Business Women’s Club are important. First, the EBWC demonstrates that black business women had their own ideas about how to improve black Detroit’s economic life prior to 1930. They would bring this background and knowledge to their work with the DHL and BTWTA. Second, that the Elliotorian Business Women’s Club was founded in 1928 shows that black women were organizing to build up the black business community before the Great Depression struck, and that they were organizing for their own interests as entrepreneurs. Neither the Elliotorian Business Women’s Club nor the Detroit Housewives League was comprised solely of businessmen’s “housewives.”

In the 1930s, most of the DHL’s ten thousand members were working-class women. However, the leadership—those who shaped the organization’s philosophy and strategies and who collaborated with the BTWTA—consisted largely of businesswomen. A review of early DHL member lists as well as minutes from organizational meetings reveals that many of the women in leadership roles were entrepreneurs or had experience working in family businesses. Helen Malloy’s oral history confirms that women were often recruited to be involved with the DHL because of their business experience. Malloy indicated that she spent a lot of time working in the shoe business with her husband before beginning her work with the Detroit Housewives League. According to Malloy, the DHL “came and got me” because of her affiliation with the family business.Footnote 59 She also indicated that most of the early DHL members were either in business for themselves or had husbands who owned businesses.Footnote 60 For example, DHL founder Fannie B. Peck established the Fannie Peck Credit Union, the first black credit union to receive a state charter in Michigan. Peck’s credit union provided vital loans to black community members until at least 1985.Footnote 61 A 1943 publication on black Detroit reported that the four largest and best-known black credit unions operating in Detroit included the Fannie Peck Credit Union.Footnote 62 In addition, in her capacity as DHL president and later as president of the National Housewives League, Fannie Peck maintained a reputation as a businesswoman. In a 1933 letter to an officer of the National Negro Business League, DHL vice-president E. L. Hemsley described Fannie Peck as “woman of a business concern” and “a woman leading a business organization.”Footnote 63

Other DHL members were business partners with their spouses or worked in family-owned businesses. For example, Charles C. Diggs Sr. was a prominent Detroit businessman (and later politician) known for running a successful funeral business. The Diggs Funeral Home would grow to be the largest funeral business in Michigan. Although the business was associated with Mr. Diggs, his wife, Mamie Diggs, was actively involved in running it. Recognizing Mamie Diggs’s role in building the family business, their son, Charles Diggs Jr., recalled, “My father came [to Detroit] from Mississippi, with my mother, and built the largest black business in the city with nothing but their bare hands.”Footnote 64 Furthermore, a 1924 profile of the funeral business stated that Mamie Diggs “acts as a woman assistant to her husband and is thoroughly interested in the business.” The same article reported, “In the making of the remarkable success which he now enjoys, Mr. Diggs attributes as much to the sagacity and foresight of Mrs. Diggs, as he does to any contribution which he himself has made.”Footnote 65 Although such public acknowledgement of women’s labor in family businesses was rare, scholarship on women’s business history shows that women have always been deeply involved with family businesses or businesses legally owned by their spouse.Footnote 66 The Diggses were greatly involved in the Booker T. Washington Trade Association and the Detroit Housewives League, and Mamie Diggs was just one of many black women who had business experience prior to organizing with the DHL.

In some cases, women appear to be the driving force behind family business ventures. Long-term DHL member Agnes Bristol, for example, co-owned the Bristol & Bristol Funeral Home with her husband Vollington Bristol, and both were active members of the Booker T. Washington Trade Association. However, it seems that it was actually Agnes Bristol who had the initial experience and qualifications in the mortuary field. She apprenticed under a Scottish undertaker for several years before passing the state board exam and receiving her license for embalming in 1922, becoming the first black woman in Michigan to be a licensed mortician, and the first black mortician to receive a Special Diploma in Mortuary Sciences from the University of Michigan.Footnote 67 Although her husband began his mortuary studies in 1920 and applied to take the state examination for an embalmer’s license in 1922, the same year as his wife, he worked as a shoe shiner until 1918.Footnote 68 It is probable that Agnes Bristol entered the mortuary field prior to her husband, if not at the same time, and was central in facilitating the start of the family business.

Agnes and Vollington Bristol were also involved with many other black businesses in Detroit, particularly those in the financial and insurance industries. However, it was Agnes Bristol who served as a director of the Great Lakes Mutual Insurance Company in the 1930s.Footnote 70 After Vollington Bristol’s death, Agnes Bristol maintained the Bristol & Bristol Funeral Home until her additional work as vice president and secretary of the Great Lakes Mutual Insurance Company began to take up too much of her time.Footnote 71 She approached Willis Eugene Smith, another funeral director and her late husband’s close friend, and asked him to manage the day-to-day operations of her mortuary business. Smith initially declined, seemingly unwilling to have a female boss, saying he “couldn’t get along with her at first because she was a woman.” In an attempt to dissuade her, Smith made Agnes Bristol an offer: “I said, I’ll tell you what I’ll do. If you buy me a Cadillac, give me 25 percent off the top, then I’ll do it. But I thought I was getting rid of her.” About three days later, Smith received a call from Ed Davis, a local African American car dealer, informing him that Mrs. Bristol “came in and gave me six thousand dollars and told me she was buying [the car] and to give you the keys.”Footnote 72 Smith took the job and the business continued until 1975.Footnote 73 This story says a lot about Agnes Bristol’s acumen as a businesswoman; she made smart business decisions and knew how to get what she wanted. Surely she brought this entrepreneurial savvy to her ongoing participation in the Detroit Housewives League.

Although women were not always the face of the businesses in which they were involved, the DHL was committed to acknowledging their business expertise. For example, the organization held a “Get Acquainted Tea” that featured “women in business and women who are contributing largely to the success of their husband’s business.”Footnote 74 One such woman was Helen Malloy, a key Detroit Housewives League organizer who served as the group’s “chairman of publicity,” writing articles and overseeing the production of all DHL bulletins. She went on to become DHL president as well as the organization’s historian.Footnote 75 Helen Malloy became involved with the DHL and BTWTA due to her experience at Malloy’s Shoe Repair, a family business established by her husband, Lorenzo Malloy. Helen Malloy was initially reluctant to accept his marriage proposal because “shoemaking was not much of a business,” in her opinion. However, after she began working in the shop and helping her husband run the business, her opinion changed. Helen Malloy realized that Lorenzo Malloy “made good” and earned much more money than she had working as a schoolteacher in Alabama, where she was from originally. She gained significant business experience participating in the shop’s day-to-day affairs, maintaining the inventory and dealing with customers, and applied her expertise to her work with the DHL.Footnote 76 Malloy made a reputation for herself as a businesswoman. In the BTWTA and DHL’s 1935 directory, Helen Malloy was listed as a “stockings” sales agent.Footnote 77 She was also featured working in the family business in the organizations’ Picture Book of Business.

Likewise, Bertha Gordy was a DHL member who operated a business associated with her husband. She and her husband Berry Gordy Sr. migrated to Detroit in 1921 from Sandersville, Georgia. The couple’s business experience began there, as Berry Gordy Sr. owned a farm and raised and sold chickens and pigs as well as cotton, vegetables, and fruit.Footnote 79 It is likely that Bertha Gordy was involved with these ventures, as farm work required family effort and women were often responsible for selling farm goods to peddlers and merchants.Footnote 80 When Berry Gordy Sr. went to Detroit and saw that there were many opportunities to launch a successful business in this northern city, he wrote to his wife asking her to join him. He later recalled, “I told her to sell out everything.”Footnote 81 His instructions indicate that Bertha Gordy was probably handling the family’s business affairs in Georgia while her husband was in Detroit. According to Gordy Sr., “I meant for her to sell the cows, our home, the chickens, mules, horse, wagon, and buggy, sell everything! But she didn’t sell nothin’!!”Footnote 82 Instead, Bertha Gordy took matters into her own hands and decided to err on the side of caution, leaving the farm under the care of family members when she went to Detroit. Her decision would prove to be a critical one once the Great Depression was under way.

In Detroit, Bertha Gordy was a deciding factor in the family’s economic success. After working for wages for a time, Berry Gordy Sr. established a contracting business doing plastering and carpentry and also purchased a grocery store. In his memoir Movin’ Up: Pop Gordy Tells His Story, Gordy Sr. describes the family grocery store as his business.Footnote 83 However, it was Bertha Gordy who actually operated the store with the help of their children, who would arrive after school.Footnote 84 Working in the family business and learning much of their business acumen from their mother, many of the Gordy children went on to become successful entrepreneurs, most notably Motown Records’ founder Berry Gordy Jr.Footnote 85

The Gordys continued to experience growth in their businesses until the Great Depression. Berry Gordy Sr. began receiving fewer contracts, and those he could secure were for small jobs. He ultimately had no choice but to close the contracting business.Footnote 87 As the Gordys’ income dwindled, their family connections in the South came in handy, especially Bertha Gordy’s decision not to sell all of their property when she migrated to Detroit. One day, the family received one hundred dollars in the mail. Bertha Gordy’s father had sold two of the cows the family had left in Georgia. Gordy Sr. remembered, “We was so happy! I wish he’d sold all of ‘em! We got that hundred dollars; seemed like five hundred dollars at that time. But then again, I thought anything was big money in the Depression years.” In addition to the money from the cows, the Gordys received a steady stream of income from renting the property they still owned in Georgia.Footnote 88 Bertha Gordy’s keen business sense had saved the family. Furthermore, her connections with the BTWTA and DHL likely also helped the family business survive during this difficult time. Bertha Gordy was a member of the BTWTA and she also served as the BTWTA corresponding secretary.Footnote 89

As these examples demonstrate, even though they were not always the public face of the operation, entrepreneurial DHL women had business experience and expertise. They did not only see themselves as housewives, nor did others in the black business community. Importantly, they used their business knowledge to help the Detroit Housewives League and the Booker T. Washington Trade Association formulate strategies to achieve their goal of boosting black-owned business.

One such strategy was for DHL women to act as intermediaries between consumers and entrepreneurs, as researching consumers’ attitudes was necessary for black businesses to better appeal to their clientele. According to DHL president Fannie B. Peck, “Bringing the producer and consumer into closer relationship cannot but bring about an understanding that will be beneficial to all. Working together, trying to solve our many problems, will go a long way toward helping us to attain our goal—an equal opportunity to take our place in the economic life of this nation.”Footnote 90 As business “boosters,” DHL members went door to door to solicit information from black consumers and explain the benefits of supporting black-owned businesses. Because their position as respectable women allowed them to enter strangers’ homes, they had access to the community’s main purchasers: black women. As black women themselves—consumers who also wanted the best for their households—their message likely engendered a sense of trust that made people open up about what they felt were the problems with certain black businesses or why they preferred to go to a white-owned enterprise. DHL women then took this information back to merchants to help them improve and grow their businesses. The DHL’s role of interlocutor between consumers and business owners was key to the organization’s importance in cultivating Detroit’s black business community.

The Detroit Housewives League also studied and compiled information about black commercial institutions in the city. The March 14, 1931, issue of the Detroit Economist reported that the Housewives League was planning a “survey of Negro business of every kind in Detroit.”Footnote 91 Conducting business research would serve the DHL and BTWTA’s mission—namely, to build and boost black-owned businesses—and indeed the DHL’s survey did provide valuable insight into the economic situation of African American entrepreneurs in the city. In 1933, the DHL again planned a “complete survey of Negro business of every kind in Detroit.” The survey was designed to serve the community by creating knowledge about existing businesses, and business owners “expressed great satisfaction in learning that the housewives have undertaken this work.” Collecting information on every black-owned business in the city was a massive assignment. However, according to the DHL, “That the task is a hard one all agree and this is perhaps why the housewives are better fitted to do the job than any other group.”Footnote 92 Black entrepreneurial women in the Detroit Housewives League occupied a unique position as both business and consumer experts.

The League published the findings from their consumer surveys, and in an article titled “Why Do We Buy What We Buy?” member Gertrude J. Tolbert laid out several factors that governed black women’s consumer decisions. These factors, listed in order of importance, were (1) quality, (2) quantity, (3) price, (4) brand, (5) confidence in merchant, and (6) attractiveness of wrappers and containers. The article advised women shoppers to test different brands and consult circulars and newspaper advertisements for the best prices. Tolbert also opined, “Buying regularly of one merchant is an advantage to the dealer and customer as a better understanding is derived between the two.”Footnote 93 Speaking to both consumers and business operators, this article exhibits the DHL’s position as a go-between for these two groups. Moreover, the data they gathered and distributed about black business was no doubt useful for understanding black entrepreneurs’ representation in specific business sectors and for planning conferences and other events to benefit the black business community. DHL’s interlocutor role between consumers and entrepreneurs continued throughout the organization’s history. In the late 1930s, DHL offered a list of tips “to improve business.” This list included the following: “Offer slow moving stock at reduced prices or combination sales”; “Shelf arrangements for quick and efficient service”; “Notice all special radio offers in your line of goods and demand them from your wholesaler”; “Polite sales people, with good memory, both of stock placements and customers [sic] needs”; and “Offer specials every three months.”Footnote 94 Thus, the DHL’s astute initiatives produced important knowledge to support business owners as well as consumers.

When DHL members felt that their work was unappreciated by male entrepreneurs, they made their role in developing black businesses explicit. An article in the Detroit Economist stated that the Housewives League “accused some of our businesses and professional men of being a bit indifferent to the interests of the League and its members.” The DHL wondered “how some men in business (we shall not call them business men) think they can bite the hand that is feeding them and expect to be fed very long.” The organization warned, “One thing is certain. Any Negro business or professional interest who thinks it [can get] very far without the support of Negro housewives and the influence they have is a plum fool.”Footnote 95 Nannie Black, who served as DHL president after Fannie B. Peck, reiterated the point, stating, “Women [hold] the key to economic success or failure, it may be turned right or left.”Footnote 96 The DHL understood their influence on black business success in Detroit and threatened to remove their support if male business owners did not respect their leadership and cooperate with them. Making their position clear, a 1935 publication claimed, “It can be said that the life of the Trade Association is really found in the Housewives League.”Footnote 97 It can only be assumed that some male business owners had trouble accepting the women’s authority. It is certainly possible that black businessmen resisted black women acting as business leaders, as women in business with spouses were often expected to play a supportive role and not be too assertive with male colleagues. In general, black business leadership was imagined as a masculine endeavor.Footnote 98 It is also possible that some businessmen minimized DHL women’s contributions, which annoyed DHL members. As Detroit Housewives Leaguer Helen Malloy indicated, DHL members did not like being thought of or treated as an auxiliary to the BTWTA.Footnote 99

However, many male proprietors did recognize and respect the DHL’s positive impact on black business growth. As mentioned in the introduction of this article, black entrepreneur Lincoln Gordon recognized the DHL’s power as “business makers,” and asked for the group’s assistance. The Detroit Housewives League did end up supporting Gordon’s product. In the September 1940 issue of the Voice of Negro Business, an advertisement for Gordon’s Quality Cleanser stated that it was “endorsed by the Housewives League of Detroit.”Footnote 100 This exposure and endorsement undoubtedly resulted in increased sales for Lincoln Gordon. Gordon’s Quality Cleanser was just one business that the DHL and BTWTA assisted during the 1930s and 1940s. Richard Austin, who struggled to establish his practice as Michigan’s first black certified public accountant, later remembered the Detroit Housewives League as an effective “band of non-violent militants” who promoted patronage of black-owned businesses like his.Footnote 101 Many other enterprises founded or expanded during the 1930s found success because of the proprietors’ close ties with the DHL and BTWTA, and these businesses would go on to impressive success in the 1940s and 1950s.Footnote 102

Job Creation and Business Education: Beauty Schools, Commercial Institutes, and Business Colleges

DHL women worked to create business opportunities for all, but their business leadership and networks especially aided black women. The institutions they established to train the next generation of black entrepreneurs especially supported one of the Detroit Housewives League’s key objectives: to improve the career prospects of young African Americans. Scholars have shown that early civil rights activism in urban migration sites in the 1930s and 1940s was often linked to opening up job opportunities in white-owned companies. Black women in different cities such as Washington, DC, Chicago, and St. Louis advocated for hiring black women workers and fairer working conditions. They also fought discrimination against black women workers in the defense industries after Executive Order 8802 officially banned such treatment in 1941.Footnote 103 In Detroit, too, black women’s organizations advocated an integrationist approach to expanding economic opportunities. During World War II, Detroit women pushed to advance the civil rights movement to a new level, especially in demanding equal opportunity in defense jobs. Black women politicized the meaning of employment and equated the right to work with other forms of citizenship.Footnote 104 The Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) received a large number of complaints against Detroit automobile companies including Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler for discriminating against black women.Footnote 105 For the women of the Detroit Housewives League, black employment was an important concern. However, they did not focus on integrating white-owned businesses, but rather on growing black enterprises as a way to expand job opportunities for African Americans. This strategy was no doubt shaped by the organization’s mission to increase black business, but also by DHL women’s own experiences as business owners and personal beliefs that enterprise was the most promising avenue for improving the economic conditions of African Americans. As key promoters of black business and creators of business education venues, entrepreneurial DHL women illuminate another facet of black women’s contributions to the goal of black economic development in this era.

In 1933, the Detroit Housewives League stated, “The problem of getting on in the progressive age is largely centered about commercial developments. Opportunities to earn a livelihood, to secure an education and to do everything worthwhile come in the final analysis through jobs.” They continued, “Jobs are essential for our group. These jobs can be acquired in proportion to our ability to mobilize the dollars we earn and spend. Spending these dollars intelligently, we will create places for our boys and girls in the commercial world.”Footnote 106 The DHL approached the matter of black youth partly through their endeavors to strengthen black businesses, working to ensure that growing enterprises could provide more employment opportunities for black workers in Detroit. They sought “to encourage many in business to improve their businesses, and instill in our youth the fact that all work well done is honorable.”Footnote 107 The League adopted the slogan, “Find a job, or make one and make your dollar do Triple duty.” A dollar “doing triple duty” would “get you what you need, give the Race what it needs—Employment, and bring what all investments should bring—Dividends.”Footnote 108

The beauty industry provided the best opportunities for black women entrepreneurs and by the 1930s, it was one of the strongest business sectors in black Detroit.Footnote 109 Because black women had even fewer opportunities for lucrative employment than black men in the 1920s, they began choosing entrepreneurship to gain the economic benefits and autonomy not possible through other jobs in which they often faced long hours, violence, sexual harassment, and meager wages. These challenges were particularly acute for black women who worked as domestic servants, and working-class southern migrants longed to escape the degrading aspects of domestic labor.Footnote 110 The 1930s saw an explosion in the number of black women who established beauty culture businesses in Detroit, as thousands of women trained in cosmetology opened shops or provided beauty services in their homes as a survival strategy during the Depression.Footnote 111 Despite economic hardship, the demand for cosmetologists’ services increased during this period. Beauty salons in northern migration sites like Detroit were important venues in which southern migrant women could shed the stigma of being “rural folk” and reconstruct themselves as sophisticated and modern. Donning the latest hairstyles (such as waved or dyed hair) enabled them to become “modern women” and “New Negroes.”Footnote 112 Additionally, the high demand for beauty culture created opportunities for entrepreneurs to manufacture hair and cosmetic products to sell to burgeoning salons and their patrons.

One such cosmetics entrepreneur was Vivian Nash, founder of Bee Dew Laboratories. Nash was a southern migrant from Locust Grove, Georgia. Her father was a prosperous farmer and, having grown up on the farm, young Vivian developed an interest in canning produce, a skill she learned from her grandmother.Footnote 113 After attending Spelman College and completing her training as a nurse at Grady Hospital in Atlanta, Nash worked in public health.Footnote 114 In 1920, she migrated to Detroit because of the many job opportunities she heard were available.Footnote 115 However, after settling in the city, Nash was disappointed to find that there were few prospects for African Americans in the field of nursing, and she had trouble obtaining permanent work in her profession. The field of beauty culture seemed to be a lucrative alternative, and Nash saw great possibilities in manufacturing cosmetics for African American consumers. Because cosmetics involved preparing vegetables and chemicals in various combinations, she decided to merge her canning skills and training as a nurse to create cosmetic products.Footnote 116

Nash established her business in 1924.Footnote 117 After the U.S. Patent Office rejected her applications for more than a dozen possible names, she finally hit upon an acceptable tag in “Bee Dew.” She sold her products door-to-door until she rented her first basement office, and later purchased the entire building at 615 East Forest Street. She hired two staff members and trained them to “sell, sell, sell.”Footnote 118 A firm believer in the value of advertising in black newspapers, Nash consistently placed advisements promoting the benefits of Bee Dew products in leading black periodicals. By advertising in the black press, she built up a mailing list of almost one hundred thousand names. This extensive mailing list covered not only the United States, but other countries as well, and drastically increased her mail-order business.Footnote 119 By 1934, ten years after founding Bee Dew Laboratories, Vivian Nash had the largest black-owned manufacturing business in the state of Michigan. At the company’s Detroit headquarters, 47 employees manufactured and sold Bee Dew products, while 452 agents and representatives were employed throughout the United States, the Canal Zone, and South Africa. Most of Bee Dew’s sales agents were black women.Footnote 120

The DHL and BTWTA were key to Vivian Nash’s continued success throughout the 1930s. She was a lifelong member of the Booker T. Washington Trade Association and was deeply involved in the organizational work from the start. In a 1935 joint publication, the BTWTA and DHL thanked several people, including Nash, for being “outstanding men and women who have contributed their part in the development of this work.”Footnote 121 Nash regularly advertised in DHL and BTWTA’s publications and directories. A 1935 advertisement for Bee Dew Laboratories stated, “Together we work for a common cause—Employment and Economic Security.”Footnote 122 This shows that Bee Dew and the Detroit Housewives League shared a common goal: increasing black economic development by creating job opportunities within the black business community. In 1938, Vivian Nash hosted “Beauticians Night” for the DHL and BTWTA’s Eighth Annual Trade Exhibition. In this program, beauticians from all over the city displayed their skills for a chance to win a prize. This event also provided exposure for beauty shop owners.Footnote 123 Thus, Vivian Nash was not only a successful entrepreneur herself, she also exemplified the DHL’s mission of creating jobs and other economic opportunities for members of her community.

In addition to encouraging job creation through business development, the DHL thought it vital for blacks to not only get an academic education, but also get a professional and business education to acquire the necessary skills to establish successful enterprises. Many DHL women identified as mothers who took seriously the need to create business opportunities for their children and future generations. The DHL established Junior Units of the DHL for boys and girls from the ages of six to sixteen. These Junior Units were designed to develop an interest in establishing future businesses and fostering economic security among black youth.Footnote 124 At the 1940 National Housewives League annual meeting, one of the program highlights was a discussion led by DHL member Gertrude Tolbert. Women who were “Housewives and Business Women” served as discussants, including DHL member and future DHL president Nannie Black, who operated a real estate business. Discussants debated the meeting theme, “A Business Educational Program The Negro’s [sic] Need,” from the standpoints of merchants, professionals, parents, and youth.Footnote 125 Additionally, a DHL informational pamphlet from the early 1940s included in a list of the organization’s purposes, “To develop opportunity for our youth,” and espoused the slogan “Forward Today For Tomorrow Through Youth, Service, Education and Business.”Footnote 126 Creating educational opportunities was a primary strategy for the organization, and entrepreneurial DHL women led the charge. By establishing successful black-owned business and commercial colleges in Detroit, they worked to reflect their reputation as “a body of noble women working unselfishly to increase the opportunities of the youth of tomorrow.”Footnote 127

Due to black women’s success in the beauty industry, some of the city’s first institutions for business training were beauty colleges. By 1937, African American women ran eight cosmetology or beauty schools in Detroit. Although three of them were branches of national organizations—such as those originally established elsewhere by Jessie Morton Williams, Madam C. J. Walker, and Myrtle Cook—the other five were founded in Detroit.Footnote 128 One of them was the Bee Dew Beauty College, which Vivian Nash started in 1936 to instruct trainees in the proper methods of using Bee Dew merchandise.Footnote 129 She purchased a building at the corner of Hastings Street and Forest Avenue, which, in addition to the college, housed the manufacturing plant, the Bee Dew Beauty Shop, and the company’s general offices.Footnote 130 Nash embraced (and likely shaped) the DHL’s goal of encouraging young black women to pursue business as a road to racial and economic uplift. An advertisement for the Bee Dew Beauty College exclaimed, “Girls! Women! Men! Learn a Profession, Become Independent, Own your own Business.”Footnote 131 By creating schools to train black women to become professionals in the beauty industry, Nash and other women entrepreneurs helped them to expand their own careers and further enhanced Detroit’s black business community.Footnote 132

The onset of World War II in the 1940s saw an expansion of black women’s economic opportunities. The war carried the United States out of the grips of the Great Depression and also spurred a second wave of the Great Migration that brought tens of thousands of black southerners to Detroit. The rapid expansion of wartime production drastically reduced unemployment in the city. Between 1940 and 1943, the number of unemployed workers in Detroit fell from 135,000 to 4,000.Footnote 133 Moreover, the war effort drew women into defense industries to replace men who had joined the military.Footnote 134 The shifting nature of women’s work and increased financial independence opened up a discussion among DHL women about the changing economic landscape for women entrepreneurs. In 1942, DHL founder and National Housewives League president Fannie Peck wrote a piece for Service Magazine entitled, “Negro Housewives What Now?” Peck pointed out, “Because of world conditions, women find doors of opportunity for participation open to them,” and asked, “Will we be wise enough to take advantage of the many opportunities that are being made available to us at this time?”Footnote 135 Relatedly, in 1944, Iota Phi Lamda, a sorority for black businesswomen, held its northern regional meeting in Detroit. Discussion topics at the meeting included “Opportunities for Negro Women in the Post-War Business World” and “What Business Women Can Do To Retain Present Employment.”Footnote 136

With World War II stimulating the city’s economy, the DHL and BTWTA focused on how to take advantage of emerging opportunities for black businesses and how to plan for the postwar economy. The Detroit Housewives League’s vision for economic advancement through education came to fruition when women entrepreneurs established a business school and two commercial institutes in Detroit. The founders of these institutions, Rosa Slade Gragg, R. Louise Grooms, and Violet T. Lewis, all had strong ties with the Detroit Housewives League and the Booker T. Washington Trade Association. These schools—the Slade-Gragg Academy of Practical Arts, the Detroit Institute of Commerce, and Lewis Business College—significantly boosted the local black business community by providing crucial skills to future entrepreneurs and training workers who went on to secure jobs as bookkeepers, typists, and secretaries in Detroit’s expanding black enterprises. By the end of the 1940s, Detroit’s business community was larger and more prosperous than ever before, in large part due to the work of DHL women.

Prior to establishing these black business institutions, African Americans did not have the opportunity to attend business school in the state of Michigan. However, recognizing the strengthening economy and influx of new migrants, women entrepreneurs saw the writing on the wall. They understood that there would be greater opportunities for black entrepreneurship, and as black businesses grew, so too would the demand for African Americans trained to work in business offices. Rosa Slade Gragg explained that she founded the Slade-Gragg Academy in 1947 in order to provide displaced and uneducated persons with opportunities for careers beyond unskilled labor once the war ended.Footnote 137 She envisioned Slade-Gragg Academy graduates who were poised, confident, and able to achieve financial independence and dignity.Footnote 138

Likewise, according to R. Louise Grooms, founder of the Detroit Institute of Commerce, “When we started even the public schools discouraged blacks from taking business courses on the theory that there was no point in it. But I always urged our students to be prepared for the opportunity that would come.”Footnote 139 Grooms had a long career before opening the Detroit Institute of Commerce in 1941, working for more than twenty years in business administration in some of Detroit’s most prominent black-owned businesses. Grooms was the longtime bookkeeper and cashier for the Great Lakes Mutual Insurance Company and had served as the BTWTA’s auditor.Footnote 140 She also spent six years as a public school teacher and decided to use her knowledge and experience in both business and education to prepare young black women and men to earn a livelihood.

The Detroit Institute of Commerce had a modest start, residing in two rooms in the Tobin Building in downtown Detroit, but throughout the 1940s it grew to occupy the entire sixth and eighth floors. R. Louise Grooms was no doubt aided by the Detroit Housewives League and the Booker T. Washington Trade Association in her efforts to establish the institute. Grooms was an active DHL member. In December 1943, the DHL and BTWTA held a Better Business Conference with the theme “Doing More with Less,” and R. Louise Grooms was on the planning committee and also gave the conference’s closing remarks. She was a member of the BTWTA’s Executive Committee, serving as the recording secretary, and the Detroit Institute of Commerce was a member of the BTWTA as well.Footnote 141 The Detroit Institute of Commerce offered stenography, executive secretarial, finishing secretarial, junior accounting, and business administration courses. The institute was licensed by the Michigan State Board of Education and authorized to train World War II veterans under the GI Bill. After ten years of operation, Grooms considered her school a success, declaring, “Negroes now own more, larger, and better organized businesses.”Footnote 142

Lewis Business College (LBC) was the largest and most successful of Detroit’s black business schools. It was also the first, established by Violet T. Lewis in 1939, and paved the way for both the Slade-Gragg Academy and the Detroit Institute of Commerce. Like Rosa Slade Gragg and R. Louise Grooms, Violet T. Lewis had a strong business background, which undoubtedly contributed to the success of her college. After graduating from the secretarial program at Wilberforce University in her home state of Ohio, she obtained her first professional job as secretary to the president of Selma University in Alabama. While there, she also taught secretarial classes in the university’s business department. Lewis eventually landed a job as a bookkeeper at the Madam C. J. Walker Company in Indianapolis, Indiana, and also operated several small businesses on the side. She enjoyed her work, but after she noticed an abundance of unemployed local young people, Lewis got the idea to start her own secretarial school to train African Americans for business careers. In January 1928, Lewis opened the Lewis Business College in Indianapolis.Footnote 143

After operating the school for almost ten years, Lewis decided that she needed to increase her income in order to send her two daughters to college. She reasoned that opening another school in a nearby city would be a viable solution. A family friend and distant cousin, Cortez Peters, suggested Detroit, noting that there were more black-owned businesses there than in any other major city. Moreover, Detroit had a large black community but no business schools that accepted African Americans.Footnote 144 Lewis decided to visit Detroit to explore this option and, with the help of some local family, found a suitable location for the college. She signed a one-year lease on an administrative building at West Warren and McGraw Avenues.Footnote 145

However, it was not only her family’s help that enabled Lewis to set up the Detroit branch of her school. Assistance from black entrepreneurs and organizations proved crucial to her success in breaking into the Detroit market, particularly the Detroit Housewives League and the Booker T. Washington Trade Association. Lewis had researched Detroit’s black community and learned of the BTWTA and DHL’s significance for local black enterprises and community belonging. She met with the organizations to discuss her plans for a new business college and solicited their advice before establishing the school. Members of both organizations pledged to support her, and DHL women promised to help promote the new Lewis Business College.Footnote 146

The DHL made good on their promise. After the state of Michigan approved her educational program and issued her a license to operate a business school, Lewis got to work advertising to Detroit’s black youth. She ran full-page ads in all three black local newspapers; members of the Detroit Housewives League canvased neighborhoods distributing flyers; and pastors of Detroit’s major black churches (many of whom were associated with the BTWTA) placed inserts in their Sunday bulletins.Footnote 147 When the doors of Detroit’s LBC opened in September 1939, Lewis was surprised and delighted to see that more than fifty students had showed up and registered for classes—more than the number of students enrolled for an entire year at the Indianapolis campus.Footnote 148 Lewis Business College became a member of the BTWTA.Footnote 149

LBC originally educated women who wanted to gain the necessary skills to work in “business careers,” which typically meant being a secretary or stenographer. These skills could also be used in operating one’s own enterprise. The college offered nine-month courses in topics such as typewriting, shorthand and stenography, bookkeeping, filing, and office machines, and later expanded its curriculum with programs in business administration and accounting.Footnote 150 Demand for the school’s services was so high that after the first year, Lewis Business College had to move from its original Detroit location and eventually occupied three adjacent properties. Although those first fifty students in 1939 gave Lewis a tremendous sense of affirmation that her Detroit venture would be a success, by 1942 the college had grown to almost three hundred students, and attendance would continue to increase.Footnote 151 Between September 1942 and August 1943, the college enrolled 514 students, and registration for the 1944–1945 school year totaled 626.Footnote 152 LBC also became coeducational when World War II veterans wanted to take advantage of the GI Bill, and had to add more class sessions to keep up with increased enrollment. On average, 350 students attended classes daily.Footnote 153

LBC’s expansion did not come without challenges and failures. For example, in the first year of operating the Lewis Business College in Detroit, Violet Lewis trusted a manager who ended up embezzling money from the college.Footnote 154 There were other challenges as well. In the early 1940s, racial tensions in Detroit were growing, and the city would ultimately erupt into a race riot in 1943. A story Violet Lewis relayed to her daughters provides insight on the racial climate that DHL entrepreneurs had to navigate when pushing boundaries in the business world. When Lewis expanded the Detroit college from its original location and moved into the historic East Ferry Avenue District in 1940, Lewis chose to move into the building at night. She framed this story as having to do with money being tight and being unable to afford to hire a moving company. She gathered a group of family and friends who brought their cars and trailers to transport the school’s equipment and furniture. They supposedly chose to do this in the middle of the night so that Lewis’s elegant new neighbors would not see the caravan of cars pulling trailers.Footnote 155 Although there were certainly times when money was tight and Lewis Business College’s working capital was minimal, the act of moving at night could also speak to Lewis’s fears that relocating to a majority white neighborhood would be met with resistance. Violet Lewis would not have been the only black entrepreneur in Detroit to use this strategy. In his memoir, Sunnie Wilson, who operated the Forest Club in Detroit, mentioned that he, too, moved into his property at night when he started the business in 1941. According to Wilson, “My acquiring the Forest Club upset my white competitors who owned established bars on adjacent corners. In an effort to block my purchase, the local [white] businessmen signed petitions in protest against me. I told my friend Police Inspector Edwin Morgan about the situation and he told me to move in at night.”Footnote 156 It is probable that white resistance was a concern for Violet Lewis as well.

Violet Lewis did experience antagonism from whites in the neighborhood once she moved into the new building. One day, when she was sitting in the college’s office, Lewis received a registered letter containing a summons from the city of Detroit instructing her to “cease and desist the operation of Lewis Business College at 5450 John R. Street, Detroit, Michigan in the County of Wayne, within 24 hours.”Footnote 157 The white citizens of the community had filed a petition against her for violating a zoning ordinance (the area where the school was located was a residential zone). However, Lewis and others in Detroit’s black community believed that the petition was racially motivated and white neighbors simply did not want black people in the neighborhood. Violet Lewis described the moment she received the summons: “I felt as if the whole world had caved in upon me.… Here I was, riding this wave of prosperity and success, and ‘bang’ its [sic] all wiped away in one crushing moment.”Footnote 158 Lewis met with Reverend Horace White of Plymouth Congregational Church, who was able to draw on his political connections and obtain a ten-day extension. Then Lewis called on Herbert Dudley and Carleton Gaines, board members of the Great Lakes Mutual Insurance Company. Dudley was a black attorney, and Carlton Gaines had a real estate business and was president of Detroit’s Victory Loan and Investment Company. Importantly, Gaines was also a charter member of the Booker T. Washington Trade Association and served as BTWTA president in the 1940s.Footnote 159 Dudley researched the zoning laws and found that a for-profit business could not operate in the area. From there, Lewis worked with Gaines and Dudley to incorporate Lewis Business College as a nonprofit organization so that Lewis could avoid eviction and the college could continue to operate. Surely working with Carlton Gaines (who subsequently served on LBC’s Board of Directors) and accessing the Booker T. Washington Trade Association’s network helped save Lewis Business College.Footnote 160

With true entrepreneurial spirit, Lewis recognized a lucrative untapped market for the training she could offer, and Lewis Business College provided bookkeepers, typists, and secretaries that enhanced the black business community in Detroit.Footnote 161 While white companies would not hire African Americans as office workers in the college’s earliest years, Detroit’s black professionals wanted black secretaries and bookkeepers, but had a hard time finding them prior to the founding of the school. Now they sought out and employed Lewis Business College graduates, acquiring the staff they needed to expand their businesses, which they did throughout the 1940s.Footnote 162 Moreover, the school provided hundreds of young African Americans with qualifications for career success. In March 1943, Lewis Business College was happy to report, “We have young men and women scattered throughout the city of Detroit, able to make their living, and to hold their own in the business world.”Footnote 163 By the early 1950s, graduates were working as personal secretaries to executives, doing administrative work for the government and private companies, and operating their own small businesses.Footnote 164

Violet T. Lewis attributed much of her success in founding Lewis Business College in Detroit to the DHL and BTWTA, and she repaid them by contributing to the organizations. Lewis advertised in DHL and BTWTA publications and participated in organizational events. For instance, she led a panel discussion on the topic “Can Victory Be Achieved on the Economic Home Front by the Housewives?” at the DHL’s annual council meeting in 1942.Footnote 165 LBC also had relationships with black women entrepreneurs involved in the Elliotorian Business Women’s Club; the Elliotorians contributed money to help Lewis Business College purchase library books.Footnote 166 In establishing Lewis Business College, Violet Lewis advanced the Elliotorians’ vision to encourage young women to enter business careers and the Detroit Housewives League’s efforts to grow black-owned business in Detroit through education.

Conclusion

This article has examined the Detroit Housewives League in the 1930s and 1940s, concentrating on DHL members’ actions as businesswomen. Despite the devastation of the Great Depression, Detroit gained a reputation for having one of the strongest black-owned business communities in the 1930s and 1940s in the United States. Reporting in 1940 on the progress of the black business community, attorney Herbert Dudley noted, “Negroes own and operate perhaps more business of their own in Detroit, than in any other of the large Metropolitan cities.”Footnote 168 This was due in large part to the work of the Detroit Housewives League and the Booker T. Washington Trade Association, partner organizations committed to boosting and building local black business. A deeper investigation into the lives of key organizational leaders reveals that DHL women were not merely “housewives” nor did they only offer supplementary support to the BTWTA. Rather, they were businesswomen and entrepreneurs in their own right, drawing on their business knowledge and experience to enact essential strategies to improve black-owned businesses. Entrepreneurial DHL women occupied the unique position of being both businesswomen and primary household consumers, which enabled them to serve as intermediaries between merchants and the larger population of black women consumers in Detroit. In this capacity, they conducted research that produced valuable business information for their community. Black entrepreneurs relied on the DHL, recognizing the organization’s importance for generating business success.