With a rapid increase of electronic communication and online social media, the English language has become a ubiquitous element in global communication. Although change is an inevitable phenomenon in any living language, an infiltration of a foreign language is often resisted by those who fear that a foreign influence would disintegrate the purity of their language, sabotaging its integrity and distinctiveness.

In Korea, this fear is manifested in a top-down national impetus to keep the Korean language ‘pure’ by urging people to avoid using foreign words. Recent proliferation of neologisms that incorporate English words has prompted ‘말다듬기 위원회’ (Language Purification Committee), a subcommittee of the National Institute of the Korean Language (NIKL), to launch a nationwide campaign to find replacement terms for frequently used anglicized expressions by soliciting the participation of the general public. The NIKL (2014) states the purpose and the mission of the Institute as follows:

The Korean language purification committee holds a monthly meeting and conducts surveys to find appropriate Korean replacements for terms that include foreign words … We are committed to keeping foreign words from entering the Korean lexicon by involving the active participation of the general public … .

In one of their latest postings, they announced their decision to adopt ‘공유 주택’ (gong-yu-ju-taek), ‘황금 시간’ (hwang-geum-si-gan), ‘일일 강좌’ (il-il-gang-juwa) and ‘해독’ (hae-dok) as appropriate Korean replacements to be used instead of widely used ‘셰어 하우스’ (sye-eo-ha-u-seu: share house), ‘골든 타임’ (gol-deun-ta-im: golden time), ‘원데이 클라스’(won-de-i-ceul-la-seu: one day class), and ‘디톡스’(di-tok-seu: detox)” respectively.

셰어 하우스(sye-eo-ha-u-seu: share house) is a new housing trend in Korea, in which single residents share the bathroom, the living room, and the kitchen, while occupying separate bedrooms. ‘골든 타임’ (gol-deun-ta-im: golden time) refers to the critical window of time in which important emergency procedures must be performed for survival. This term appeared numerous times in the recent media concerning the Sewol Ferry tragedy as the government was severely criticized for failing to act within the 90 minute critical window of time as the following headlines illustrate (boldface added):

-

• <세월호참사> ‘안이한 대응으로 놓쳐버린 골든타임’ (<Sewol Ferry Tragedy> ‘Lost Gol-deun-ta-im Due to Slow Response’, May 15, 2014, Yonhap News)

-

• ‘세월호 골든 타임, 국가는 없었다, (‘Sewol Ferry Gol-deun-ta-im, There Was No Government’, Sewol Ferry 100 Day Anniversary Documentary by Newstapa).

‘원데이 클라스’ (won-de-i-ceul-la-seu: one day class) refers to hands-on trainings sessions provided in a single day for those who wish to quickly learn simple skills such as baking and flower arrangements.

Regardless of the institutionalized efforts to curve the usage of anglicized terms, English has a growing influence on the daily communication of Korean people as new words using English continue to be created and widely used by the people as well as various channels of media. Considering that many of these expressions have become staple lexical resources for the Korean people, examining the development of neologisms could provide invaluable insights into the development of nativized words as well as a candid view of the dynamic sociocultural and sociolinguistic façade of the country at the present time. The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of anglicized neologisms that were coined in the new millennium. In doing so, this study seeks to demonstrate the pivotal role of English in the daily communication of Koreans and the linguistic creativity exhibited by these expressions.

Data

Neologisms discussed in this paper are drawn from three sources: Neologisms Not Included in the Dictionary (NNID 2007), ‘2014 Neologisms’ (NIKL 2015), and Online Youth Slang Dictionary (OYSD 2014). The stated purpose of the first two sources, both compiled under the auspice of NIKL, is to ‘understand language usage and to examine the birth and death of vocabulary in Korea’ (NNID 2007: 6) and ‘to provide convenient service for contemporary Korean users, hoping to resolve problems of unequal share of information and communicative conflicts between generations and social classes’ (NIKL 2015: 3). The two combined sources contain around 4000 neologisms which have appeared in various media channels since 2002, and they include slang, specialized jargon, as well as non-specialized neologisms used by the general public.

NNID (2007) includes neologisms which first appeared between 2002 and 2007, and there is a few years of gap between the publications of the two NIKL sources. Therefore, it was necessary to find an additional resource that contains more recent items. Because there were no published sources on neologism created during this period at the time of the study, OYSD (2014) was selected to partially fill this gap. Originally developed in 2010 by a youth pastor as a smart phone application for the purpose of helping older generation to communicate better with young people, OYSD (2014) has received wide attention from various channels of news media. Unlike typical printed dictionaries compiled by lexicographers, entries in OYSD (2014) are updated periodically and participation is open to the public. The entries included in this study were taken from the list available as of December, 2014. Despite what the title suggests, several expressions listed in OYSD (2014) are currently used by the general public (e.g., 돌싱, 득템, 치맥, 고터, and 선톡), not just by youth, illustrating that the label ‘slang’ is often loosely used by common people. In this paper, all entries are considered under a broad category of neologisms. However, when certain expressions seem predominantly used by the youth, such information is mentioned in the discussion. Example sentences that contain those expressions are drawn from various media sources to demonstrate their usage.

Among around 4000 expressions listed in these sources, approximately one-third of them contain English in various forms. Since the purpose of this paper is to identify trends and patterns, not to provide an extensive list, a limited number of examples are introduced in this paper. The data sources, especially the first two, include a large number of direct English loan words, such as ‘camera phone’, ‘blog’, ‘chef’, ‘board game’, ‘spam message’ and numerous others that are used by Koreans with nativized pronunciations. However, direct loan words were not included in the discussion because the study focused on nativized neologisms that exhibit modifications at the morphological and semantic levels, not just at the phonological level. Also excluded are blends which seem to have originated from other countries (e.g., ‘manny’: man + nanny; and ‘sellsumer’; sell + consumer).

Categories

Based on their grammatical structure, most neologisms fall into the existing categories of nativized loan words, such as mixed-code combinations, clipping, creative compounding, and semantic shift. However, there are a number of new innovations found in recently created neologisms, such as inverse phonetic translation, pictographic representations, and Romanized initialism. The categories established in this study, however, do not represent exclusive, fixed categories because neologisms may fall into multiple categories when more than one morphological process is involved in the formation. For example, clipping is involved in the creation of many mixed-code combinations words. However, expressions categorized as clipping in this study are confined to those that do not combine Korean words. In case multiple morphological adaptions are manifested, items have been categorized based on the most salient and meaningful feature in the process of formation. The Romanization of Korean words presented in this study follows the guidelines established by the NIKL. Hyphens are added to distinguish syllables.

Mixed-Code Combinations

Sornig (Reference Sornig1981: 78) noted that mixing vernacular with foreign words tends to create delight and humor, and Park (Reference Park2008: 515) observed that most neologisms coined and used by the 21st Korean youth utilize creative wordplay. Words that belong to this category are coined by combining Korean and English, often creating a humorous effect. Most of them fall into two types of structure: Korean + English or English + Korean. But some items follow a more complex structure such as Korean + English + Korean and English + English + Korean.

Structure 1: Korean + English

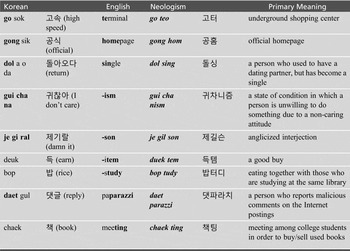

The structure of the first type combines clipped Korean adjectives or nouns followed by clipped English nouns. Many of these expressions consist of two syllables, Korean providing the first syllable, and English the second. English words that provide the suffix are commonly used English loan words, such as ‘homepage,’ ‘computer’, and ‘character,’ but sometimes, clipped English syllables (e.g., i tem , pa parazzi , and mee ting ) serve as suffixes, producing a series of derivatives (See Table 1).

Table 1: Korean + English

Note. The syllables of the clipped Korean and English words are bolded to show the formation of new words.

Although most of these terms are self-explanatory, some items have expanded in their meanings and may require additional cultural or contextual information in order for readers to understand the meaning. For example, the meaning of the term ‘고터’ (go-teo) (the first example in Table 1) has expanded to mean shopping centers under or around the bus terminal. Although it initially referred to the long-distance (‘고속’, go-sok) bus terminal ( teo -mi-nal: terminal), go-teo is now used as a favorite shopping venue for many people because a variety of affordable merchandise is available. An example of a rather ‘formal’ usage of this term is shown in the following newspaper headline:

-

• ‘권리금 없이 쫓겨날 위기에 놓인 “고터” 상인들’ (‘Go-teo Merchants at the Brink of Being Dispersed without Receiving Deposit,’ March 5, 2009, Ohmy News).

‘돌싱’ (dol-sing) is another popular term. It is formed by combining ‘돌아오다’ (dol-a-o-da: return) and the first syllable of ‘single’ and is used for a person who once had a dating partner, but has reverted to a single status.

‘제길슨’ (je-gil-seun) is an anglicized interjection, which combines an existing Korean interjection, ‘제기랄’ (je-gi-ral: similar to ‘damn it’), with an English affix ‘-son,’ and is used euphemistically to express disappointment or frustration. Although it is not known why ‘-son’ is used among others, one could speculate that ‘-son’ has the effect of euphemizing the negative interjection through personifying and anglicizing, thereby ameliorating the term as it conjures up an image of a popular Anglo person (e.g., Johnson, Wilson, or Thompson, which are rather common and well known English names for Koreans).

‘귀차니즘’ (gwi-cha-ni-seum) is created by combining ‘귀찮아’ (gwi-cha-na: ‘I don't care’ or ‘I don't want to be bothered’) and the English suffix ‘-ism’, used to express a state of condition in which a person is unwilling to do something due to a non-caring attitude. One university library website had a blog entry entitled, ‘귀차니즘을 없애는 21 가지 방법’ (21 Ways to Get Rid of Gwichaniseum) intended to help students overcome inertia and achieve success.

‘득템’ (deuk-tem), ‘댓파라치’ (daet-parazzi), and ‘책팅’ (chaek-ting) use clipped English syllables as suffixes and have gained several related expressions. ‘득템’ (deuk-tem) combines ‘득’(deuk: to earn) and ‘템’ (tem: from ‘item’) and is said to originate from the Internet games in which winning equals earning more items. However, this term is now also used to mean situations that are perceived to be lucky such as having a good buy, or getting a boy friend or a girl friend who seems undeserved. One online shopping mall advertised, ‘득템찬스 기획특가’ ( deuk-tem -chan-seu-gi-hoek-teuk-ga: Special Promotional Sale for Deuk-tem Chances). It has produced two other forms, ‘레어템’ (re-uh-tem: a rare item) and ‘필수템’ (pil-su-tem: an essential item).

‘댓파라치’ (daet-pa-ra-chi) combines the first syllable of ‘댓글’ ( daet -geul: comments/replies to internet postings) and the last three syllables of ‘paparazzi’. This term is used when referring to a person who reports malicious comments on the Internet postings. There are several related expressions using the same construction: ‘실파라치’ (sil-pa-ra-chi: ‘sil up’-job loss + paparazzi), for instance, is a person who makes money by reporting those who receive workers’ compensation through fraud; ‘카파라치’ (ka-pa-ra-chi: car + paparazzi) is someone who reports traffic violations; ‘쓰파라치’ (sseu-pa-ra-chi: ‘sseu-re gi’-garbage + paparazzi) is someone who reports littering; and ‘팜파라치’ (pam-pa-ra-chi: pharmacy + paparazzi) is someone who reports illegal pharmaceutical practices. In all these cases, the first syllable provides a cue as to what kind of illegal action is being observed/reported.

Other interesting examples include derivatives of ‘애드립’ (ae-deu-rip: ad lib). It is not clear how a Latin-based word gained popularity in Korea. A shortened form, ‘드립’ (deu-rip: -d lib) is thought to have surfaced on the Internet several years ago, and two other forms soon followed: ‘개드립’ (gae-deu-rip) and ‘패드립’ (pae-deu-rip). ‘개드립’ (gae-deu-rip: nonsensical, worthless remark) combines ‘개’ (gae: dog), with the first coda and the second syllable of ‘ad lib.’ ‘패드립’ (pae-deu-rip), with the prefix ‘패’ (pae: ingrate, shameful) means a shameful remark or comment. Along with resyllabification (‘a dlib’), the syllable initial liquid /l/ changes to a tap /r/. As Heo and Lee (Reference Heo and Lee2004: 47) noted, an onset liquid of the English word becomes a tap in loanword phonology in Korean (e.g., lobby: ro-bi, outline: au-teu-rain), which is illustrated in this example. The final devoicing of /b/ to /p/ also conforms to the native Korean constraint of no-voiced stops in coda position (Kang, Reference Kang2003: 224).

Structure 2: English + Korean

Words that belong to this category are created by combining English and Korean. The English part provides a noun, and the following Korean also uses a noun, thus forming compound nouns. Although typical English words are nouns, there are variations as in ‘아웃오브안중’ (a-u-do-bu-ahn -jung: out of sight) and ‘리즈시절’(li-zeu-si-jeol: liz time, meaning one's best days), suggesting that grammatically more diverse structures are being utilized in the creation of recent neologisms. The English nouns used in all other cases include common loan words such as ‘bus card’, ‘internet’, ‘chicken’, ‘profile’, and ‘chatting,’ but may also include a word that has semantically changed such as ‘code’ (See Table 2).

Table 2: English + Korean

‘버카충’ (beo-ka-chung: adding money to a bus card) combines two English words ‘bus’ and ‘card’ with chung from ‘충전’ (chung-jeon: to fill) and those not familiar with the term may erroneously think that it is a name of a bug, as chung also means a bug in Korea. Two years ago, participants of the ‘Live One-hundred Thousand Won Quiz Show’ (SBS, Jan. 6, 2012) who were able to tell the meaning of this term were entered into a drawing for a cash prize, but it now seems to be understood by most people thanks to the media. The title from the entertainment section of Chosun.com on June 8, 2014 may frustrate those who are trying to learn Korean as it describes a brief conversation between two female TV stars using two neologisms. It says, '김대희, '버카충'하라는 김지민 말에 '멘붕' (‘Kim Dae-Hee has men-bung when Kim Ji Min tells her to do beo-ca-chung.’) Telling someone to do bu-ca chung means to add money to their account to make the bus card usable, and Kim Dae Hee, upon hearing the remark, experiences men-bung, a temporary brain freeze, not having understood the term.

‘치맥’ (chi-maek: chicken and maek-ju, beer) is probably one of the most popular terms frequently appearing in the media. The City of Daegu recently hosted a ‘Chi-Maek Festival.’ SBS news featured a special report on February 27, 2014 on how chi-maek (with the emphasis not so much on beer but on the Korean style fried chicken) has become increasingly more popular in Beijing and Shanghai thanks to the popular Korean drama, 별에서 온 그대 (My Love is from Another Planet). ‘The popularity of chi-maek has dispelled the fear of bird flu in China!’ a Chinese reporter remarks in the news, reporting on a rather unusual phenomenon as customers line up to buy Korean style fried chicken. The term was introduced by Jun Ji Hyun, the lead actress, when she said, ‘눈오는 날엔 치맥인데’ (‘On a snow day, I need chi-maek’) in the drama. Chosun.com featured an article entitled '치맥'의 굴욕’ (‘The Humiliation of Chi-Maek’), describing extremely low sales of chicken when the Korean Worldcup team lost.

‘코드인사’ (co-deu-in sa: code + ‘insa’) started appearing in the newspaper headlines during the presidency of the late Rho Moo Hyun, referring to his staff appointment decisions, which some have criticized for being based on shared political views and personal affinity. ‘코드’ (co-deu: code) is widely used by Koreans to refer to ‘chemistry’ or ‘affinity’ between people, collocating with a verb “맞다’ (to agree), producing ‘코드가 맞다’ (to have agreeable ‘codes’; to have similar chemistry). Combined with ‘인사’ (in sa: staff appointment), ‘코드인사’ (co-deu-in-sa) is used when a person with a dominant position or a highest authority appoints a staff because of shared political views or personal affinities rather than based on a person's objective qualifications.

Structure 3: Korean + English + Korean or English + English + Korean

Some expressions exhibit more complex constructions. In this case, the last part is usually a Korean suffix denoting groups of people, such as ‘남’ (nam-man), ‘녀’ (nyo-woman), or ‘족’ (jok-type of people). For instance, ‘뇌색남’ (neo-sek-nam) combines ‘뇌’ ( noe : brain), clipped English word ‘sek’ from ‘sexy,’ and ‘남’ ( nam : man). It is broadly defined as a man who has a ‘sexy brain’, possessing intelligence, humor, independent thinking, and other intellectually attractive qualities. Other examples that belong to this category use the previously introduced word, ‘돌싱’ (dol-sing: a person who once had a dating partner, but has reverted to a single status), which has produced two other forms, such as ‘돌싱남’ (dol-sing-nam) for men and ‘돌싱녀’ (dol-sing-nyeo) for women, using a clipped English syllable ‘sing’ from ‘single.’

‘워런치족’ (weo-run-chi-jok) combines ‘워’ (weo) from ‘walk’, ‘런치’ (reon-chi) from ‘lunch’, and the Korean suffix ‘족’ jok (type of people). This term is used to describe office workers who take a walk during a lunch break. In Korean, the phonemes /r/ and /l/ are non-contrastive in prevocalic positions (Borden et al., Reference Borden, Gerber and Milsark1983: 507–510). ‘런치’ (reon-chi) shows a common phonological adaptation of English onset liquids in which a liquid becomes a tap in English-based Korean loanword phonology (Heo & Lee, Reference Heo and Lee2004: 49; Kang, Reference Kang2012: 43). Also, an epenthetic vowel is inserted after ‘-ch’ creating /ɾʌnt͡ʃɪ/ instead of /lʌnt͡ʃ/.

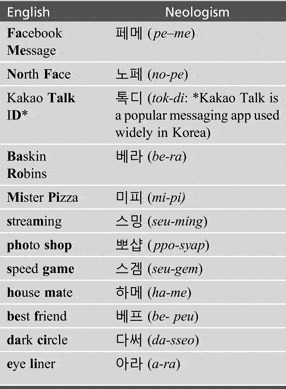

Clipping

Although most anglicized neologisms contain some form of clipping, words considered in this category include those expressions which consist entirely of clipped English words and no semantic change (See Table 3). OYSD (2014) particularly includes many examples in this category, suggesting that clipping is a common characteristic of youth language.

Table 3: Neologisms Created with Clipped English Words

Since the Korean language does not allow labiodental fricatives in the syllable initial position, phonological adaptations are made in the clipping process, as dental fricatives /f/ and /v/ change to a labial /p/ and /b/ respectively. Also, diphthongs are monophthonized, the first vowel taking precedence. The last example ‘아라’ (a-ra: for ‘eye liner’) is another example in which the liquid phoneme becomes a tap intervocalically as previously illustrated. Another consistent pattern is that words ending with bilabial or velar consonants are always pronounced in their entirety, whereas the postvocalic /r/ is always dropped. For example, the pronunciation of word final consonants in ‘shop’, ‘game’, ‘up’, ‘team’ is preserved, but /r/ is not manifested at all, as ‘circle’ becomes ‘sseo’, ‘dark’ becomes ‘da’, and ‘mart’ becomes ‘ma’. This is because when /r/ is preceded by a vowel and functioning as a coda, English /r/ is dropped in Korean (Heo & Lee, Reference Heo and Lee2004: 50).

Creative Compounding

Words in this category may sound like English, but will be incomprehensible to most English speakers outside Korea since the terms include either non-idiomatic combination of English words, or some novel creations.

For example, ‘파덜어택’ (pa-deul-eo-taek: father attack) models after ‘heart attack’ and is used for situations when one is in the middle of playing games and has to stop because of fathers’ sudden appearance. It could also mean getting in trouble with father in the middle of games or online activities. A columnist of Kyunghyang Shinmoon, a Korean newspaper, presents the following hypothetical conversation between two teens that is like to occur in everyday conversations, asking the readers to test their knowledge of teen slang terms (taken from a Dec. 31, 2011 column. Boldface added):

-

A: 어제는 미안, 엄크 떠서 GG했어

Sorry about yesterday, I did GG because of eom-ku.

(I said ‘Good Game’ --meaning leaving the game-- because my mom suddenly came in.)

-

B: 난 또 너 파덜어택 당해서 오늘 학교 못 나오는 줄 알았다.

I thought you'd be absent today because you had a pa-deul-eo-tek.*

*father attack: getting into trouble by father

‘티처보이’ (ti-cheo-bo-i: teacher boy) is a nativized expression that epitomizes the current educational dilemma in Korea. Modeling after a pejorative English term ‘mama's boy’ (called ‘mama boy’ in Korea), ‘teacher boy’ refers to a student who cannot study on his or her own without receiving help from a private tutor or a commercial institute (hagwon). As the majority of Korean students attend these private institutions after school, concerns have been raised that many students these days seem unable to study on their own. A newspaper title demonstrates this phenomenon: ‘Cannot study alone: 50% of students are teacher-boys’ (Hangyore, Dec. 16, 2003).

‘OME’, reminiscent of ‘OMG,’ means ‘Oh My Eyes’ and is used when one expresses displeasure, embarrassment, or a mild form of disgust upon seeing something inappropriate. Although it is initialism (later discussed), ‘OME’ is considered in this category in that it models after ‘OMG,’ and the meaningful and salient feature concerning the formation is the fact the expression creates a Korean version of ‘OMG’, whereas the initialism is not a novel feature.

Some words are created by combining two clipped English words. For example, ‘에바’ (e-ba) combines ‘error’ and ‘over’, with retroflex r dropped and /v/ changed to /b/, and is used to describe someone who has an erroneous belief and thinks that the other party (usually a person of the opposite sex) likes them. ‘셀카’ (sel-ka) combines ‘self’ and ‘camera,’ to mean a ‘selfie.’ ‘비조트’ (bi-so-teu) combines ‘business’ and ‘resort,’ ‘호캉스’ (ho-kang-seu) combines ‘hotel’ and ‘vacance’ (loan word from French, meaning vacation), and ‘셀러던트’ (sel-leo-deon-teu) combines ‘salary man’ and ‘student,’ referring to someone who has a job and also goes to school.

‘골드미스’ (gol-deu-mi-seu: gold miss) is used for women aged between 30s and 50s who have achieved strong financial, career achievements and are unmarried. It is created by altering the onset consonant of an existing term, ‘old miss,’ which is widely used by Koreans when referring to a woman who is unmarried beyond the ‘usual’ age of marrying. ‘골드미스’ is now used in the marketing field as well as other types of media as shown below:

-

• ‘골드미스 결혼 시장의 불편한 진실’ (‘An Inconvenient Truth in the Gol-deu-mi-seu Marriage Market,’ Magazine.hankyung.com, April 27, 2011)

-

• ‘골드미스, 좀더 일찍 돌싱남성에게 마음 열면 …’ (‘Gold-deu-mis-seu, if she could open her heart to dol-sing-nam a little earlier …,’ from a remarriage matching service website, ionlyyou.co.kr, Sep. 3, 2012)

Semantic Shift

Other expressions exhibit semantic change. ‘루저’ (lu-jeo: loser) is used for people who are perceived to be inferior and is also used specifically to refer to a short man, after a female character in KBS TV program used the term to refer to a short man. ‘뽐뿌’ (ppom-ppu: from ‘pump’) is used for something that triggers a desire to purchase a certain product. An online gamer recently posted, ‘I feel a strong ppom-ppu watching my brothers’ games,’ indicating a strong urge to purchase those games.

Another term used among teens is ‘슈퍼 선데이’ (super Sunday). Super Sunday in the U.S.A. typically refers to a NFL Super Bowl Sunday, but it has a totally different meaning for the Korean youth. Many last-year Korean high school students are required to attend school on Sundays in order to study for the college entrance exam, which is known to be highly competitive. For these students, super Sunday is an occasional Sunday when they do not have to go to school.

Another example is ‘스펙’ (spek: from ‘specifications’), which has become an integral Korean vocabulary word for the current Korean youth who are seeking jobs. Unlike previous examples that undergo no morphosyntactic change, ‘spek’ is used as a clipped form and also exhibits semantic change. Originating from ‘specifications’ of an electronic merchandize (e.g., properties or features), ‘spek’ is used to refer to a person's qualifications, credentials, or abilities for a job. ‘Spec’ collocates with ‘쌓다’ (‘build’), and ‘building one's spek’ means gaining knowledge, education, and experience to qualify for employment. A recent newspaper headline is only one of the many examples in which this word appears:

-

• ‘스펙이 약해서? 취업실패 진짜 이유 있다’ (‘Because of a weak spek? A real reason for failed employment’, Korea Times, March 11, 2015)

Inverse Phonetic Translation

Several terms are created by ‘translating’ the perceived English sounds, (not the actual meaning of the words) to Korean words that sound somewhat similar to the pronunciation of the English words, and these words are mainly used by youth. These expressions are compound words originally consisting of two English words, such as ‘H-Mart,’ ‘G-Mart,’ and ‘PC Room,’ but the first part of the words undergoes an inverse translation, from English to Korean.

For example, H /eitʃ/ in H-Mart is an onomatopoeia for a sneezing sound in Korean. Sneezing, associated with cold, links H to ‘cold.’ Cold is in turn translated to the Korean word, ‘감기’ (gam-gi), and ‘mart’ is changed to a one syllable ‘mall’ to create ‘감기몰’ (gam-gi-mol), a ‘cold mall.’ In the same way, ‘G’ in ‘G mart’ sounds like ‘쥐’ (jwi: a mouse) in Korean, so ‘a G mart’ becomes a ‘쥐마트’ (jwi-ma-teu), a ‘mouse mart’. ‘Mart’ becomes ‘ma-teu’ dropping the /r/ and adding an epenthetic vowel. A PC room is a gaming center, equipped with multiple computers for people to play games at an hourly rate. The pronunciation of PC is similar to Korean way of pronouncing ‘fish’ /pi si/ conforming to the CV syllabic structure through epenthesis, so it becomes a ‘물고기방’ (mul-go-gi-bang), ‘a fish room.’ Considering that PC rooms usually have a negative image due to frequently reported gaming addiction among youth, this term seems to euphemize the negative image of PC rooms by using a creative wordplay.

Pictographic Representation

‘KIN’ utilizes pictographic representation and manipulation. Somewhat similar to English imperative, ‘scram,’ it is used as a multipurpose interjection to show disgust, disinterest or disapproval. Originating from the new Korean youth interjection ‘즐’ (jeul), it was first used by online gamers and was later ‘anglicized’ by rotating the word 90 degrees to the left, replacing each Korean alphabet character with an English alphabet character of similar appearance:

![]()

‘KIN’ has produced another neologism, ‘펌킨족’ (peum-kin-jok). It is a creative word play, utilizing a pun for ‘pumpkin’, although it has nothing to do with the gourd. ‘펌킨족’ (peum-kin-jok) combines three parts: ‘펌’ ( peom - copying someone else's internet posting and sharing it on another site), ‘KIN’ (즐, from 즐기다-enjoy), and ‘족’ ( jok -Korean suffix for types of people), forming a complex noun used as an epithet for those who enjoy copying an online material what someone else has posted and posting it elsewhere. The second part ‘KIN’ is an example of back-formation, as KIN is used for ‘즐’ as mistakenly assumed to be a derivative of 즐기다 (jeul-gi-da: enjoy) rather than of the neologism ‘즐’ (jeul: scram). This word showcases a highly sophisticated process that some recently created words exhibit, as it utilizes pictographic representation, mixed-code combination, back-formation as well as pun in a single word.

Romanized Initialism

Some adjectives used as epithets for peers who seem ‘arrogant’, ‘appearing all knowing’, ‘pretending to be strong’ take the form of two-letter initials. All of the examples are drawn from the OYSD (2014) and include JC, from ‘잘난척’ ( j al-nan-cheok: arrogant), AC from ‘아는척’ ( a- neun-cheok: prentending to know it all), and SC from ‘쎈척’ ( s sen-cheok: pretending to be strong), all of which taking the first initials of the first and the last syllables of the Korean words and Romanizing them. SM from ‘실망’ ( s il-mang: disappointment) is another example that utilizes Romanized initialism. These initials serve as a masquerading device to precisely and quickly label peers’ behaviors or the speakers’ own feelings about them without being explicit.

Conclusion

This study has illustrated various creative processes in which anglicized neologisms are created. Also, it has demonstrated that seemingly random creations exhibit phonological regularities. The increased usage of Anglicism undoubtedly reflects the rapidly changing reality, in which English plays a pivotal role in daily communication of Korean people. New words are often created in order to close lexical gaps that may exist in a given language (e.g., creation of ‘prepone’ in Indian English as an antonym for ‘postpone’). Various neologisms introduced in this paper demonstrate linguistic ingenuity and creativity of the Korean people, and some creative expressions presented in this paper could potentially become useful additions to the English lexicon as Korean English.

The author finds it interesting that there are some unique commonalities between English-based Korean and Japanese youth language. For example, according to Stanlaw (Reference Stanlaw and Coleman2014: 161–165), truncation (clipping), abbreviation, and other phenomena such as inverse phonetic translations, graphic linguistic wordplay, and various examples of Romanized initialism are also found in Anglicized Japanese youth language. Similar studies conducted in other languages will help researchers to take the scholarly endeavors beyond identifying the trends of anglicized neologisms of a single language and perform comparative studies, which may reveal emergent typologies of English-based neologisms. Studies involving languages with similar linguistic structures may yield potentially useful information concerning common trends in new-word formation.

Although a number of existing English-based loan words have long been in use in Korea, neologisms in the new millennium exhibit more complex morphosyntactic processes, with many expressions not fitting existing categories of loan words. This suggests that modern day Koreans consider the English vocabulary as a handy tool that helps enrich their lexical repertoire and do not hesitate to borrow, clip, and bend them to fit their needs. As innovative languagers, they navigate between two very different linguistic codes and boldly manipulate them in order to create an alternate code which they can use with expediency, thereby showing their joint ownership of the English language as a global lingua franca.

Eun-Young Julia Kim is an Associate Professor of English at Andrews University, USA. She holds a Ph.D. in English from Northern Illinois University and has worked with English language learners both in the U.S. and Korea for a number of years. She currently directs the graduate program in the Department of English at Andrews University. Her research interests include sociolinguistics and second language writing. Email: keun@andrews.edu

Eun-Young Julia Kim is an Associate Professor of English at Andrews University, USA. She holds a Ph.D. in English from Northern Illinois University and has worked with English language learners both in the U.S. and Korea for a number of years. She currently directs the graduate program in the Department of English at Andrews University. Her research interests include sociolinguistics and second language writing. Email: keun@andrews.edu