1 Introduction: the issue

The variety of English spoken in the city of York in northern England has three non-standard determiners: the zero article (Ø) (Christophersen Reference Christophersen1939), reduced determiners (Wright Reference Wright1905), represented by ? in (2), and complex demonstratives of the type this here NP (Bernstein Reference Bernstein1997). The three constructions all occur in York English and they are illustrated in (1)–(3) from the York English Corpus (YEC) (Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte1996–8):

(1)

(a) You know, Ø night life’s brilliant. (Nancy Heath, 20)Footnote 2

(b) You used to have to walk across Ø floor and ask a girl to dance. (Bradley Lowe, 62)

(c) Were you here before Ø Barbican got converted? (Nick Hudson, 17)Footnote 3

(2)

(a) Our street was better than ? next street. (Bradley Lowe, 62)

(b) We loved going to ? Lake District. (Elise Burritt, 82)

(c) I'll come down for ? last hour, for a nice quiet drink with the regulars. (Louise McGrath, 27)

(3)

(a) Oh yes yes, she can sit on– on that there trolley and go up. (Gladys Walton, 87)

(b) ’Course . . . you know what these here police are. (Reg Fielding, 87Footnote 4)

(c) So I er, I hear tell about this here draining coming off. (Reg Fielding, 87)

While our earlier studies considered reduced determiners and the zero article (Rupp Reference Rupp2007; Tagliamonte & Roeder Reference Tagliamonte and Roeder2009), we now turn to the complex demonstrative. Several questions immediately arise: When did the complex demonstrative construction emerge, what is its function, and what has been its place in the English determiner system over time? Moreover, why does it occur in York English, and what is its function in the York community in the twentieth century? We will address these questions within the framework of the grammaticalization ‘cycle of the definite article’ and the Definiteness Cycle as proposed in the seminal works by Greenberg (Reference Greenberg, Greenberg, Ferguson and Moravcsik1978) and Lyons (Reference Lyons1999), respectively, and aptly outlined and applied to a range of different languages by Epstein (Reference Epstein and Andersen1995) and Van Gelderen (Reference Gelderen2007). In English, the Definiteness Cycle arguably applied in the north of England as this is where the definite article developed from the demonstrative paradigm (Millar Reference Millar2000). Note also that northern English continues to preserve historical features such as verbal -s, the Northern Subject Rule (Klemola Reference Klemola and Tristam2000), the for to complementizer, and deictics yon and thon, among others (see Tagliamonte et al. Reference Tagliamonte, Smith and Lawrence2005: 82). It is thus plausible to inquire whether the complex demonstrative construction in York English can be understood as a reinforcing stage in a definiteness cycle, such that the locative adverbials here/there came to reinforce demonstrative determiners that were phonetically reduced. In this context, we will argue that the reduced determiner in York English, a phenomenon that in the existing literature has commonly been analysed as Definite Article Reduction (DAR; e.g. Jones Reference Jones1952), is in fact best seen as derived from Demonstrative Reduction (DR). We will also examine to what extent the coexistence of different historical demonstrative forms and functions in York English fits Hopper's (Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991) notion of ‘layering’.

The structure of this article is as follows. Before we explore the emergence and function of complex demonstratives, we first describe the mechanism of the Definiteness Cycle in section 2. In section 3 we introduce the complex demonstrative construction and present an overview of existing research on this vernacular determiner. In section 4 we describe our data and our analytic method. Section 5 presents the results and in section 6 we discuss the implications of the findings. We will demonstrate that an investigation of the complex demonstrative construction in the YEC offers a window on evolution of the determiner system in English at large and elucidates grammaticalization trajectories.

2 The Definiteness Cycle

Models of the evolution of determiner systems have frequently focused on the grammaticalization of demonstratives into definite articles. Greenberg's (Reference Greenberg, Greenberg, Ferguson and Moravcsik1978) cycle contains four stages. Stage 0 in the cycle is the demonstrative. In Stage I, the demonstrative develops into a definite article that indicates the accessibility of a referent. In Stage II, the definite article has become near obligatory, except in a few cases including proper names and generic nouns. In Stage III the article is fully grammaticalized; it is indiscriminately attached to nouns and functions only as general marker of nominality. As pointed out by Epstein (Reference Epstein and Andersen1995), Greenberg does not address European languages at any length. However, Epstein cites Harris (Reference Harris, Traugott, Labrum and Sheperd1980) as demonstrating that French most fully illustrates the sequence of development described by Greenberg. First, the Latin distal demonstrative ille gave rise to the French definite article in Stage 1. Further, French (Harris claims) is currently approaching Stage III; one of the arguments in favour of this view being that the definite article is used with generic nouns (e.g. j'aime le fromage ‘I like (*the) cheese’). At the same time, the cycle of the definite article is undergoing renewal as the expressions ce/cette/ces have come to be used without their reinforcing particles (ci/là ‘here/there’) as simple demonstratives (e.g. cette femme(-ci)), perhaps on their way to turning into definite articles.

Building on Greenberg's (Reference Greenberg, Greenberg, Ferguson and Moravcsik1978) work and Traugott's (Reference Traugott, Lehmann and Malkiel1982) view of the cyclic nature of grammaticalization, Lyons (Reference Lyons1999) has proposed a Definiteness Cycle on the model of Jespersen's (Reference Jespersen1917) Negative Cycle. In the Definiteness Cycle, the form and the meaning of a definite article may weaken, until it is reduced to a suffix and ultimately zero. The weakened article is reinforced by another definite form that progressively takes over the range of definite meanings and generalizes throughout the entire domain, until it ultimately replaces and ousts the original article. Meanwhile, an intermediate stage can occur that is characterized by coexistence of old and new forms (a.k.a layering; Hopper Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991) and an ‘overlap’ in use or meaning; a phenomenon that we will return to in the context of the complex demonstrative in section 6. Finally, the new form may itself become reinforced and eventually lost in the next step in the diachronic process. The cycle will then be repeated. Lyons (Reference Lyons1999: 78) illustrates his cycle with, amongst other examples, so-termed ‘double determination structures’ in Scandinavian. The example in (4) is from Swedish.

(4)

Swedish has two articles: a bound-form article and a free-form article. In Swedish, the bound-form article (-an in (4a)) is thought to be a reduced form that has derived from a free-form determiner that no longer exists (Dahl Reference Dahl and Kortmann2004). The bound form has been reinforced by a new free form (den in (4b)) and the old and the new co-occur in the presence of an adjective (see Delsing Reference Delsing1993 and Hankamer & Mikkelsen Reference Hankamer and Mikkelsen2002 for different accounts of this phenomenon).

Turning to the specific case of English, most scholars assume that there were no articles in Old English (see, for instance, Traugott Reference Traugott and Hogg1992). It is also commonly agreed that the definite article (the) arose in early Middle English and evolved from the simple demonstrative paradigm. The simple demonstrative paradigm had pronominal and adjectival use (Traugott Reference Traugott and Hogg1992: 171) and is shown in table 1.

Table 1. Simple demonstrative paradigm in Old English

In late Old English, many previously distinct forms of the simple demonstrative paradigm began to fall together into a lesser number of distinctive forms. The <sV> forms were levelled with the initial voiceless þ of the other cases. The nominative masculine and feminine forms of the simple demonstrative paradigm sē, sēo fell together into þe (the), while the neuter form þæt gave rise to the contemporary distal demonstrative that. In his corpus study of a variety of historical texts from a range of different regions, Millar (Reference Millar2000) has shown that this new demonstrative-article system first took hold in the north of England. From there it gradually spread, progressively working its way through the Midlands, and reaching completion in the south-east of England around 1350.Footnote 5 Following Harris (Reference Harris, Traugott, Labrum and Sheperd1980), Epstein (Reference Epstein and Andersen1995) notes that English is currently in Stage I: the definite article developed from a demonstrative element and its basic function in English is to mark the identifiability of a referent from a previous mention in the discourse or retrieval from the physical environment.

Following an inquiry into the grammatical properties of the complex demonstrative construction, we will explore the place of different demonstrative forms in the cycle.

3 Complex demonstratives

In their basic use, demonstrative pronouns serve to create a joint focus of attention for the speaker and the addressee, indicating the location of a referent relative to a deictic centre (Diessel Reference Diessel2006: 464, 494). ‘In contrast to content words, deictic expressions do not evoke a concept of some entity . . . but establish a direct referential link between world and language . . .’(Diessel Reference Diessel, Maienborn, von Heusinger and Portner2012: 1). The deictic centre may be a point in the physical world (situational deixis) or a particular point in the unfolding discourse (discourse anaphoric deixis). Accordingly, demonstratives are used to refer to concrete entities in the surrounding situation and they may also refer to linguistic elements in the ongoing discourse (Reference Diessel2006: 481). Diessel (Reference Diessel, Maienborn, von Heusinger and Portner2012) points out that the discourse use may seem more abstract to the extent that it is not a concrete act of reference. However, he goes on to explain that in language, discourse is commonly conceptualized in spatial terms: ‘Discourse consists of words and utterances that are processed in sequential order . . . [T]he deictic centre of discourse deixis is defined by the location of a deictic word in the ongoing discourse, from where the interlocutor's attention is directed to linguistic elements along the string of words and utterances’ (Reference Diessel, Maienborn, von Heusinger and Portner2012: 19). In this way, place deixis provides the conceptual and linguistic foundation for more abstract varieties of deixis. The two basic uses of demonstratives are illustrated in (5a, b) (Diessel Reference Diessel, Maienborn, von Heusinger and Portner2012: 12, 20):

(5)

(a) I like that one better. (situational deixis)

(b) I really didn't like [science]. I mean I'm too lazy for that, I think . . .

(discourse anaphoric deixis)

Diessel (Reference Diessel2006: 474) reports that in some languages, demonstratives have been combined with context words to reinforce their pragmatic function. Very often, the reinforcing element is another demonstrative. (Diessel illustrates with French celui-ci vs celui-là.) In York English, demonstratives may be combined with here and there; deictic adverbs of place. This gives rise to constructions of the type dem adv n that may in principle turn up in four manifestations: this/these here NP and that/those there NP (e.g. this here town).Footnote 6 The construction is illustrated in (6).

(6)

(a) What is that there red book do you know. (Albert Jackson, 66)

(b) Oh! Well when these here gangs went out they had three acre to pick a day. (Reg Fielding, 87)

(c) . . . thing that sticks out mainly in mind is about this here er- air craft (Samuel Clark, 75)

(d) Aye, aye and by God, you talk about two bombs, them there were (Reg Fielding, 87)

While this construction has been labelled in different ways (for example, Bernstein Reference Bernstein1997 calls them ‘demonstrative reinforcement constructions’), for reasons of transparency we will refer to it using the neutral label ‘complex demonstrative’. Scholars agree that ‘complex demonstratives’ as in (7a) constitute an adjectival construction that should be distinguished from Standard English examples such as (7b) with a true, locative adverbial. Note, for example, that in (7a) but not in (7b), the adverbial is dependent on the demonstrative (example from Bernstein Reference Bernstein1997: 91):

(7)

(a) this (*the) here guy (non-standard English)

(b) this (the) guy here (standard English)

Thus far, research on complex demonstratives has been largely in the field of theoretical linguistics, where researchers have attempted to establish its status and have been challenged to unravel the DP structure of the construction.

Kayne (Reference Kayne, Leclère, Laporte, Piot and Silberztein2004) adduces further evidence that ‘here/there’ in the non-standard English construction is demonstrative here/there rather than locative here/there. Among the arguments that he raises for this view is that the construction behaves differently from (reduced) relative clauses with locative here/there (viz. this book (that/which is) over there vs *that over there book) and the fact that demonstrative here/there cannot be stressed (viz. *This here letter is more important than that there one).

Bernstein (Reference Bernstein1997) has examined the construction from a cross-linguistic perspective, focusing on word-order differences between Germanic and Romance languages. Using the generative framework, she assumes that the word-order contrast can be explained by the presence or absence of movement of nominal constituents. (8a, b) below compares English to French, where the adverbial precedes and follows the head noun, respectively:

(8)

(a) this here guy

(b) cette femme-ci (French)

this women-here

We refer to Bernstein (Reference Bernstein1997) for the details of her account. We turn here to her interesting observation that like simple demonstratives, complex demonstrative constructions in English are generally ambiguous between their basic deictic (situational and discourse-anaphoric) reading and an indefinite specific interpretation (Reference Bernstein1997: 95). This is illustrated in (9a–c).

(9)

The indefinite specific reading was first identified by Prince (Reference Prince, Joshi, Webber and Sag1981), who argued that they serve to introduce new information in the discourse: a topic that is going to be talked about (see her work for discussion of more features of the construction). The indefinite specific reading becomes apparent when the complex demonstrative is construed with a restrictive relative clause, as in (10a, b), in which case the deictic interpretation is unavailable. In order to obtain a deictic interpretation for the demonstrative, the accompanying relative clause must be non-restrictive as in (10c, d) (1997: 102):

(10)

Leu (Reference Leu2007) in his discussion of Germanic demonstratives attempts to provide a unified analysis of determiner phrases that includes demonstratives. He proposes that determiner phrases are morphosyntactically complex in involving an adjectival modification structure (FP) that contains a determiner, an adjectival modifier and an agreement head (AgrA). In plain definites the determiner may occur with a range of different adjectives, as illustrated in (11a) from Norwegian. In demonstratives, the demonstrative modifier is here/there and contributes demonstrativity (an index and an deictic feature). The modifier remains silent in simple demonstratives like (11b) where the determiner is stressed and has a demonstrative interpretation (Reference Leu2007: 142–3; both examples cited from Vangsnes Reference Vangsnes1999: 120).

(11)

In colloquial Norwegian as well as in Swedish, the demonstrative modifier can be overt, as shown in (12) (Leu Reference Leu2007: 145).

(12)

Leu argues that there is morphological evidence and semantic reason to distinguish between a (c)overt demonstrative modifier here/there and a reinforcer here/there. First, it is possible in Norwegian and Swedish for the demonstrative modifier here/there, which will be inflected like other adjectives, to co-occur with a reinforcer here/there (see (13) from Vangsnes Reference Vangsnes2004: 13). Second, while demonstrative here/there can have both a locative deictic and a discourse anaphoric reading, only the locative reading is available in the presence of reinforcer here/there. This is shown (14a, b) below (Reference Leu2007: 151):

(13)

(14)

Leu notes that demonstrative here/there is not obligatorily associated with locativeness and suggests that the construction contains a complement place or thing. He points out that a counterpart of here/there as a component of demonstratives is well-attested in Scandinavian, Germanic and also in non-Indo-European languages such as Australian and native American languages (Leu Reference Leu2007; see references therein). We also refer the reader to Van Gelderen (Reference Gelderen2007) for an overview of languages that have a complex demonstrative construction including Afrikaans.

Summarizing, there is evidence that complex demonstratives constitute a separate construction from one that combines a demonstrative with adverbial (locative) here/there. The complex demonstrative behaves like a simple demonstrative to the extent that the construction conveys the same range of meanings: situational, discourse anaphoric and indefinite specific.

4 Method

The 1.2 million words in the YEC offer an ideal opportunity to examine this phenomenon. The data set comprises conversations with the indigenous population of the city of York in north-east England. At the time of data collection (1997) York was a relatively small city with a population of only 177,000. The cultural and economic conservatism and monolithic population base of York at the time (see Wenham Reference Wenham1971; Feinstein Reference Feinstein1981) made it a unique situation for linguistic study (see e.g. Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte1998; Tagliamonte & Ito Reference Tagliamonte and Ito2002; Tagliamonte & Roeder Reference Tagliamonte and Roeder2009).

The individuals represented in the YEC were chosen on the basis of their native status in the community. Each person was required to meet the sampling criteria of having been born and raised in York. Anyone who had spent more than a cursory amount of time away from the city (i.e. for university education or military service or other) was excluded (see also Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte1998). The sample design represents a broad range of ages and a balance of males and females. From these materials we manually extracted all tokens of complex demonstratives and examined the context in which each one occurred in order to establish their interpretation.

5 Results

The literature provides little detail of the historical origin, current distribution or use of complex demonstratives. The construction is not attested in the Linguistic Atlas of Early Middle English (Laing Reference Laing2013) and therefore seems not to have occurred in this period 1150–1325 (M. Laing p.c.). The earliest example cited in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED 1989) dates from the late fourteenth century just after the Early Middle English period. This and another OED example are shown in (15a, b) (963, 160):

(15)

(a) God forbede þat ony Cristene man understonde, þat þis here synsynge and criyinge . . . be þe beste servyce of a prest. (c.1380 Wyclif Sel. Wks. III. 203)

‘May God forbid that any Christian man should suppose that this very censing and singing . . . might be the best service of a priest.’

(b) Now what experience will be greter than this heare? (1556 Aurelio & Isab. (1608) H viij)

The OED distinguishes between two uses of the complex demonstrative construction: an adverbial (locative) use and an adjectival use. The OED states that in the adverbial use, here and there are ‘used for the sake of emphasis after a sb. qualified by this, these, or after the demonstratives themselves when used absolutely’. The adverbial use of this here can be seen in (15a–b) above. In the adjectival use, the OED maintains that here and there are used ‘dialectally or vulgarly appended to this, these . . . (Cf. F. ce livre-ci, ceci, celui-ci)’ (1989: 160), but the OED does not look at the precise meaning that is conveyed.Footnote 7 The OED also postulates an adverbial and adjectival use of that there (p. 870) but only presents an illustrating example of the adjectival use. The adjectival use of the complex demonstrative construction is shown in (16a, b) below (OED 1989: 906).

(16)

(a) I should be glad to know how my client can be tried in this here manner. (1762 Foote Orators II. Wks. 1799 I. 210)

(b) Did you ever get a ducking in that there place? (1778 Miss Burney Evelina (1791) II. xxxvii. 244)

As pointed out to us by Margaret Laing (p.c.) and evident by the dating of the sources, the adjectival use is of later occurrence than the adverbial use. We note that only for the adverbial use of the complex demonstrative does the OED state that the NP can remain implicit. We will return to these observations in our analysis of the complex demonstrative in section 6.

A search amongst a number of historical corpora corroborates the date of occurrence of the complex demonstrative sketched above. We did not find examples of the complex demonstrative in The Penn–Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Middle English (PPCME2; 1150–1500) (Kroch & Taylor Reference Kroch and Taylor2000) nor in The Parsed Corpus of Early English Correspondence (PCEEC; 1350–1710) (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Nurmi, Warner, Pintzuk and Nevalainen2006). The earliest examples in The Penn–York Computer-annotated Corpus of a Large Amount of English (PYCCLE; 1473–1800) (Ecay Reference Ecay2015) are from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries but not straightforward for independent reasons. Some subsequent examples are given in (17). They all seem to have a deictic reading.

(17)

(a) Howbeit this here note in the, that these Fathers auouch Christ feared not his (bodily) death or / . . . (1546 or 7 – 1616 Thomas Bilson)

(b) This here one ring can witnesse, when I parted, / Who but seewte Maister Goldstone, / . . . (Thomas Middleton, d. 1627; [By George Eld] for Richard Bonlan, 1608)

The Corpus of Late Modern English Texts (CLMET3.0; 1710–1920) (De Smet et al. Reference De Smet, Diller and Tyrkkö2013) covers a later period. The tokens of this here NP date from 1751. Tokens of these here NP occur somewhat later. Apparently in accordance with the dating of the adjectival use of the OED, some of them, such as (18b), seem to allow for a non-deictic reading.

(18)

(a) you have the conscience, I wonder now, to charge me for these here half-dozen little mats to put under my dishes? (1796-1801 Maria Edgeworth The Parent's Assistant, or Stories for Children)

(b) Now that they've begun to favour these here Papists, I shouldn't wonder if they went and (1839 Charles Dickens Barnaby Rudge)Footnote 8

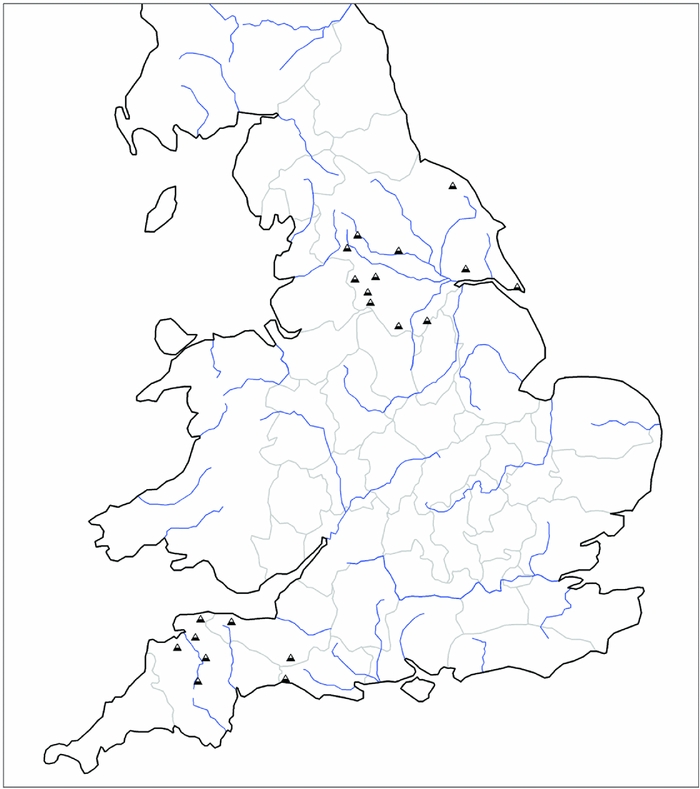

It is suggestive that the earliest texts that the OED names as including tokens of the complex demonstrative construction are from Yorkshire. The provenance of later texts extends into the East Midlands and further. Particularly significant in this relation and the context of our present study is that consultation of the Survey of English Dialects (SED; Orton & Dieth Reference Orton and Dieth1962–71) demonstrates that in the 1950s, complex demonstratives were only found in localities across the historic county of Yorkshire, as well as a few localities in the southwest.Footnote 9 The distribution of complex demonstratives attested in the SED is shown in map 1.

Map 1. Distribution of complex demonstratives in the SED (Orton & Dieth Reference Orton and Dieth1962–71)

The YEC contains sixteen occurrences of the complex demonstrative construction amongst six speakers. All six speakers were older speakers of 63–, 64–, 66–, 75– and two of 87 years of age, three men and three women. The sixteen tokens are presented below according to one of the four possible readings that were conveyed: situational deictic, discourse anaphoric, indefinite specific, and the later, adjectival use of the OED, the precise sense of which we will address in section 6. In order to make the reading salient, part of the discourse context in which the complex demonstrative occurred has been included.

In (19a, b), the complex demonstrative is used in a standard demonstrative manner to indicate elements that are physically present in the speech context (Diessel Reference Diessel, Maienborn, von Heusinger and Portner2012). Note that (19b) shows the complex demonstrative being used without an overt NP.

Situational deixis

(19)

(a) (Albert Jackson, 66)

<081> Er I- I 'll show you. (inc). What is that there red book do you know? </081>

<082> Don 't know. </082>

<081> I 'll get it. </081>

(b) (Maria Griffith, 63)

<043> It was him and a couple of his friends you-know that had er been having a go at the nicotine lollipops in the garage. Oh deary me. And once when I was changing his bed and I found an air gun under his er- and air rifle under his bed. I thought ‘What in heaven's name is this here for?’ <043>

The examples in (20a, b) illustrate another use that is central to the category of demonstratives (Diessel Reference Diessel, Maienborn, von Heusinger and Portner2012); namely, for the hearer to keep track of referents that have been mentioned in the prior discourse (two bombs and a hymn, respectively) (discourse anaphoric use).

Discourse anaphoric deixis

(20)

(a) (Reg Fielding, 87)

<1> ’Cos in the second world war, you said there was a big bomb dropped here. </1>

<092> Oh tell me. Two, two. This house of Frenchies, where David is now. </092>

<1> Spring-Villa. </1>

<092> Spring- Villa yes. Aye, aye and by God, you talk about two bombs, them there were. </092>

(b) (Gladys Walton, 87)

<1> What do you like to listen to? (20.8) </1>

<011> Um, well these is all my s– tapes you- know, and- but the one she gave me was Rosemary- </011>

<1> Oh yeah. </1>

<011> Singing. And then there's er (music starts playing quite loudly in the background). Cross- you know that there hymn about cross. </011>

The examples in (21a, b) illustrate a perhaps less well-known interpretation of demonstratives: the indefinite specific interpretation, as first identified by Prince (Reference Prince, Joshi, Webber and Sag1981; see section 3). In this use, the demonstrative serves to indicate a topic shift; i.e. to direct the addressee's attention to a new discourse participant (Diessel Reference Diessel, Maienborn, von Heusinger and Portner2012: 21). Note that the complex demonstratives in (21a, b) can indeed be replaced by the indefinite article a; one of Prince's criteria for identifying an indefinite specific.

Indefinite specific reading

(21)

(a) (Reg Fielding, 87)

<1> Yes. Why were these cottages condemned? </1>

<092> Well because, look at them, look at the condition. There was great wall built up at back there. </092>

<1> That's right yeah. </1>

<092> You-see there was no- no back. There were just this here outlet to um– up that passage. (8.1) </092>

(b) (Samuel Clark, 75)

<080> Anyway, er, there was this book. There were two or three books about like and this was er, H.G.Wells's er, Shape of Things To Come. And by God what a- what a- what a man had to have- thing that sticks out mainly in mind is about this here er, air craft of some description a huge thing which you couldn't hear it until it had gone had- and it came to pass before war finished. </080>

The final use that has been identified for the complex demonstrative is the later, adjectival use of the OED. To the best of our knowledge, the adjectival use has not been associated with the simple demonstrative, unlike the previous three uses. The OED (1989: 160) describes the adjectival use as ‘dialectal’ and ‘vulgar’, but does not detail any pragmatic or semantic properties. Johannessen (Reference Johannessen, Solstad, Grønn and Haug2006) has identified a new use of complex demonstratives in Norwegian. She coins this use ‘psychological deixis’. In this use, the complex demonstrative invokes psychological distance to the person referred to by the noun. We tentatively ascribe the data in (22a, b) to this use, noting that the speaker appears to express a negative attitude to the referent of the NP. In (22a), he characterizes policemen as misbehaving and in (22b) he describes the complaining behaviour of a workforce. We will explore the sense of the adjectival use/‘psychological deixis’ more closely in section 6.Footnote 10

Adjectival use

(22)

(a) (Reg Fielding, 87)

<092> Oh yes, I la– I think that was really why- why she went. By. Ee, aye, well I w– I tell you I were talking to [. . .] about it and I said to him well I said ‘It were you to blame as much as her really.’ </092>

<1> Yeah. </1>

<092> ’Course he- you see he we– you- know what these here police are. They can (inc) and er he- he used to go to- they said he could sup a bottle of whisky a day. </092>

(b) (Reg Fielding, 87)

<092> Well er, he was manager. And they said he was a sod to work for. </092>

<1> Yeah </1>

<092> These l– these here lads you know. (10.0) And I remember- 'course he was one of them that liked a bit you-know, a reg- sergeant major. Oh, 'course he was a- he was a Sergeant. </092>

<1> He always prided himself on having been a Sergeant. </1>

We now summarize the two main findings from the YEC. First, we found few tokens of complex demonstratives in the corpus (16 tokens: 1.2 million words) and no younger speakers use the construction. The scant tokens of the complex demonstrative used only rarely and restricted to the older speakers in the corpus suggests that these constructions are destined for moribundity.Footnote 11 Second, despite the fact that there were only few tokens, all four semantic/pragmatic types were represented. This included a putative extended adjectival use of a later date. The apparent synchronic diversity suggests a different sense of Hopper's (Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991) ‘layering’ in that various historical forms of the demonstrative coexist (DR, complex) in a range of different functions. These forms correspond to successive phases in the grammaticalization process and they show a differential use across generations of speakers. In the next section, we will explore in more depth the implications of these findings for our understanding of the diachronic development of English demonstratives within the Definiteness Cycle in particular and grammaticalization processes at large.

6 Discussion: evidence for the historical development of the determiner system

We will now return and address the questions that we posed at the beginning of the present article: When did the complex demonstrative construction emerge, what is its function, and what has been its place in the English determiner system over time? Moreover, why does it occur in York English, and what is its function in the York community in the late twentieth century? Synthesizing across all the information and findings, we seem to arrive at a paradox regarding the place of the complex demonstrative in the determiner system over time. If the Definiteness Cycle is correct, we should not find a complex demonstrative in these data. Instead, it would be expected at some earlier stage in the history of York English, during which time it served to strengthen a simple demonstrative that had earlier weakened phonetically and/or lost concrete meaning. If so however, it should have disappeared in the next phase of development. Such a regular stepwise progression does not seem to have been the case. We would like to argue that the complex demonstrative actually strengthens the evidence for the Definiteness Cycle and current views of the nature of grammaticalization.

Specifically, we suggest that the English demonstrative has undergone the following phases in the Definiteness Cycle (adapted from Hopper & Traugott's Reference Hopper and Traugott2003: 2–3 characterization of the grammaticalization process).Footnote 12

(i) phonological reduction

(ii) loss of concrete meaning

(iii) reinforcement

(iv) acquisition of new, more abstract and speaker-based meanings

(v) layering

First, Rupp (Reference Rupp2007) has in fact argued for the occurrence of a reduced form of the demonstrative in the history of English; namely, DAR. In the context of analysis that is presented here, it is important to note that DAR is a characteristic feature of dialects in the north of England, including York English (see Rupp Reference Rupp2007, Tagliamonte & Roeder Reference Tagliamonte and Roeder2009, and references therein for details). Previous research (e.g. Jones Reference Jones, Upton and Wales1999) has documented a variety of different DAR forms, amongst which [t, θ, ʔ] and other phonetic variants are attested, but in writing it is customary to represent DAR as t’, as in examples like (23) below. The examples are from Rupp & Page-Verhoeff ’s (Reference Rupp and Page-Verhoeff2005: 335–6) study of the use of the reduced form by eight speakers in a number of villages situated at the Yorkshire–Lancashire border.

(23)

Whereas DAR is commonly taken to be a reduced form of the definite article, Rupp (Reference Rupp2007) maintains that the most plausible perspective on the reduced form is that it derived from the final [t] of the distal demonstrative (a possibility previously contemplated by Brunner Reference Brunner1962). For this reason, Richard Epstein (p.c.) suggests that DAR is best renamed DR (Demonstrative Reduction). Among the arguments that Rupp (Reference Rupp2007) presents for the DR view is that the range of different variants in which the reduced form may occur – [t, θ, ʔ] – follows naturally from a process of lenition, while the DAR perspective needs to make a special assumption to be able to account for the occurrence of [t]: the so-called ‘assimilation theory’ (see Jones Reference Jones2002 for a description of and problems with this theory as an adequate explanation for the occurrence of [t]).Footnote 13

Second, while this may not be immediately obvious, the meaning of the demonstrative does appear to have weakened over time. Recall from section 3 that simple demonstratives currently have two basic uses: situational deixis and anaphoric deixis (Diessel Reference Diessel, Maienborn, von Heusinger and Portner2012: 12, 20). However, Millar (Reference Millar2000) and Epstein (Reference Epstein2011) have shown that at an earlier stage in the history of English, the distal nominative neuter demonstrative þæt and the distal nominative masculine demonstrative se (see table 1 again) had a much wider range of uses than the demonstrative has today. This suggests that some of the original meaning of the demonstrative paradigm was lost.Footnote 14 Epstein (Reference Epstein2011) has analysed the use of the nominative masculine distal demonstrative se as a discourse marker in the Old English epic Beowulf. He reports that in addition to its more commonly recognized meanings (deictic distinctions), se also displayed properties that are different from modern English uses of both that and the. Namely, se was also used to convey the relative importance of a participant, to signal the topicality of a referent (especially topic continuity or topic persistence over a portion of the text in the sense of Givon Reference Givon1983) and to indicate episode boundaries in noun phrases appearing at either the end of a chapter or the beginning of a new one. These uses are shown in (24a, b) from Epstein (Reference Epstein2011: 123, 132), respectively.

(24)

Taking all of these observations and the facts from the YEC into account, we propose the following scenario. þæt and þe broke away from one another in the demonstrative paradigm in early Middle English. The split in the demonstrative paradigm first happened in the north of England. (We refer the reader to section 2.) Following Millar (Reference Millar2000), the English demonstrative shifted in usage towards ‘pure’ distal demonstrative meaning as a result of the split. þæt lost the functions with which it had earlier been associated (as identified by Millar Reference Millar2000, see footnote 14), including the article meanings which þe came to carry. Traugott (Reference Traugott, Lehmann and Malkiel1982: 252) writes that once the new form the developed, the demonstrative was effectively relieved of article functions and continued primarily in its alternative uses including establishing the speaker's (a) physical distance from the objects in the situation outside the text (at the propositional level), or (b) evaluative distance (at the expressive level). It is to the latter use that we will turn shortly. Millar (Reference Millar2000) assumes that Old English þæt specialized towards a distal demonstrative meaning earlier than the collapse of forms into þe, which he dates back to early Middle English. In the north of England, the semantic specialization of þæt led to a reduction in form, which we have termed DR (Demonstrative Reduction) rather than DAR (Definite Article Reduction). In this relation, we would like to point out that Rupp & Verhoeff (Reference Rupp and Page-Verhoeff2005) found that while the speakers of their study used the reduced DR forms in all current article functions, they were deployed most frequently for situational deixis (as in (23a) above), where the referent of the noun is visible and directly identifiable in the extra-linguistic physical context, and for discourse-anaphoric deixis, (as in (23b)), where the referent of the noun has been introduced in the preceding discourse. Note that these are precisely the two basic functions of the demonstrative (Diessel Reference Diessel, Maienborn, von Heusinger and Portner2012) and that these basic uses form an early extension area for demonstratives to develop into definite articles (e.g. Pass me that/the stool, please; Lyons Reference Lyons1999: 164). Moreover, a study of D(A)R in the YEC (Rupp & Tagliamonte forthcoming) found that discourse context was a significant predictor: situational and discourse-anaphoric reference favoured the D(A)R forms.

We envisage that in third phase in the Definiteness Cycle, the demonstrative, under the pressure of DR, came to be reinforced by the locative adverbs here and there. This development gave rise to the complex demonstrative construction. Following Diessel (Reference Diessel2006), who credits Lehmann (Reference Lehmann1995), reinforcement is a mechanism of language change that strengthens linguistic expressions that have lost some of their phonetic substance and/or pragmatic force. We might speculate that reinforcement occurred by the end of the Middle English period, and that it happened in northern England, in Yorkshire in particular. Note that the earliest examples of DR cited in the Oxford English Dictionary (1989) are of a similar date as the examples of the complex demonstrative; namely, 1350–1400 following the early Middle English period. The complex demonstrative examples were given in (15) and the DR data are presented in (25) below. Note also that the sources of the examples are written in a dialect of the north of England and come from letters between the members of the Yorkshire-based Plumpton family, respectively.

(25)

(a) Sua sais te prophete (c.1400 Rule St Benedict 12)

(b) The said lands . . . & t'office of the Steward (1496 Plumpton Corr. P ci)

The data from the elderly York speakers suggest that the complex demonstrative continued to be used in the regular deictic meanings (situational deixis (see (19a, b)) and discourse anaphoric deixis (see (20a, b))). However, more detailed empirical investigation into the history of the northern ME dialect is needed to established the date of emergence of the complex demonstrative.

It seems that the complex demonstrative itself has subsequently weakened in both form and meaning/function to the extent that here/there cannot be stressed (for at least some speakers; Kayne Reference Kayne, Leclère, Laporte, Piot and Silberztein2004) and no longer conveys (concrete) deictic reference in a later, adjectival use. In an analysis of complex demonstratives in Norwegian, Johannessen (Reference Johannessen, Solstad, Grønn and Haug2006) has identified a new use that she coins ‘psychological deixis’. This use indicates some distance by the speaker towards the referent. In (26), according to Johannessen, ‘[t]he effect is not only one of psychological distance [with respect to] how well the speaker knows the referent, but is one of a somewhat negative attitude towards that person’ (Reference Johannessen, Solstad, Grønn and Haug2006: 102).

(26)

This use looks like the type of use found in the YEC (see (22a, b)).Footnote 15 We acknowledge that the categorization is based on interpretation only. We are currently not aware of other distinctive – for example, grammatical – features that independently show the putative use (similar to the morphosyntactic properties that Leu (Reference Leu2007) has identified for the adjectival complex demonstrative in Norwegian and Prince (Reference Prince, Joshi, Webber and Sag1981) for the indefinite specific reading, as we have shown in section 3). In the historical and YEC data under consideration, a grammatical feature that seems to separate the ‘situational deictic’ use from the adjectival/‘psychological deictic’ use is that only in the first use can the NP be covert/absent. However, the adjectival/‘psychological deictic’ use patterns with the discourse anaphoric and indefinite specific use in this respect. Therefore this aspect of the analysis must remain speculative. Following Diessel (Reference Diessel1999), other languages show alternative outcomes of the grammaticalization of complex demonstratives, such as the occurrence of new demonstrative forms that consist of an old demonstrative determiner and a locative adverb. ‘Afrikaans, for instance, has two demonstratives, hierdie “this” and daardie “that”, which are historically derived from the Dutch demonstrative/article die and the demonstrative adverbs hier “here” and daar “there”’ (Reference Diessel1999: 74).

What seems clear is that rather than giving way in turn, according to the traditional view of the cyclic nature of the Definiteness Cycle, the complex demonstrative was not a transitional phenomenon, but a productive part of an evolving system and developed an extended use in a fourth stage in the Definiteness Cycle. Much recent work has indeed shown that grammaticalization is not a process that solely involves loss. Instead, grammatical development involves gains and losses, with shifts of meaning. An element that was once restricted to a particular range of contexts may develop new uses. Hopper & Traugott (Reference Hopper and Traugott2003) have argued that while characterizations of grammaticalization typically refer to the weakening of semantic meaning, in early stages of the grammaticalization process it is actually not adequate to speak of a lexical item showing semantic ‘bleaching’. ‘Rather, there is a balance between loss of older, typically more concrete, meanings, and development of newer, more abstract ones that at a minimum cancel out the loss.’ (Reference Hopper and Traugott2003: 101). The newer, more abstract meanings emerge by ‘grammaticalization through inference’ (Reference Hopper and Traugott2003: 3). Note that there is an inference of ‘psychological deixis’ from the situational deictic use of a locative expression. The notion of location conveyed, however, is a more ‘abstract’ location: a mental space. That is to say that when the complex demonstrative further grammaticalized, it did not result in across the board re-semanticization of here and there but retained a vestige of spatiality. One way of putting it is that the function of indicating psychological distance was in fact dormant. (This is reminiscent of Hopper's (Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991: 28–9) Principle of Persistence in grammaticalization.)

Epstein (Reference Epstein and Pagliuca1994) has argued that extended, non-canonical uses of a lexical item in grammaticalization are primarily motivated by pragmatic or discourse considerations and in fact serve expressive purposes, such as conveying subjective judgments. He states (p. 75):

the factors that motivate grammaticalization at the end of a cycle – the need to increase processing speed, achieved through the spread of one grammatical element . . . at the expense of others with which it contrasts paradigmatically should be distinguished from the motivating factors that typify the initial stages of a cycle, where a grammaticalizing element is used in unexpected contexts for expressive purposes.

Indeed, Epstein (Reference Epstein and Pagliuca1994, Reference Epstein and Andersen1995) incorporates these ideas into his analysis of the grammaticalization process of the zero and the definite article in the history of French. He cites Traugott & Koning (Reference Traugott and Köning1991: 190–1), who have similarly maintained that especially in the early stages of grammaticalization, new meaning may be added to an element in the form of a pragmatic ‘strengthening of the new expression of speaker involvement’. Traugott (Reference Traugott, Stein and Wright1995: 32) has described this pragmatic-semantic process as ‘subjectification in grammaticalization’ ‘whereby meaning becomes increasingly based in the speaker's subjective belief/state/attitude about the problem’. Traugott (Reference Traugott, Stein and Wright1995: 49) argues that it is specifically the subjective stance of the speaker that is strengthened. The assumption is that the more grammaticalized, the more subjective a form or phrase will be in meaning; that is, the more abstract, pragmatic, interpersonal, and speaker-based functions it will develop. Traugott (Reference Traugott, Davidse, Vandelanotte and Cuyckens2010) illustrates the process in a sketch of the historical trajectory of three partitive expressions, including a shred of. She shows that in Old English, a shred of meant ‘a fragment cut off from fruit or vegetable . . .’, while by the twentieth century it came to imply a negatively evaluated degree modifier (as in not a shred of intelligence) (Reference Traugott, Davidse, Vandelanotte and Cuyckens2010: 50). This explanation of the grammaticalization process fits the facts of the complex demonstrative. While functioning as part of the Definiteness Cycle, it developed this new nuanced meaning.

The question is: what processes of linguistic variation and change have led to the current situation where, at least in York in the late twentieth century, complex demonstratives can still be found? The scenario we have in mind aligns with current thinking regarding the process of grammaticalization. Epstein (Reference Epstein and Andersen1995: 159) writes:

One of the most important findings to have emerged from the study of the development of grammatical forms is the hypothesis of unidirectionality, which claims, among other things, that ‘there are strong constraints on how a change may occur and on the directionality of the change’ (Hopper & Traugott 1993: 95) and more specifically, that ‘grammaticalization clines are irreversible’ (126) . . . However, not all changes reach the natural endpoint of their grammaticalization paths; ‘A particular grammaticalization process may be, and often is, arrested before it is fully “implemented”’ (Hopper & Traugott 1993: 95).

Our findings from the YEC afford a particular interpretation of Hopper's (Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991) Principle of Layering in grammaticalization. Hopper & Traugott (Reference Hopper and Traugott2003: 124) define layering as ‘the persistence of old forms and meaning alongside newer forms and meanings . . . at any synchronic moment in time’. As Hopper (Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991: 22) first put it: ‘Within a broad functional domain, new layers are continually emerging. As it happens, the old layers are not necessarily discarded, but may remain to exist with and interact with the new layers.’ Layering typically involves various forms with the same function. However, in the YEC: (1) the reduced demonstrative (DR), the simple demonstrative and the complex demonstrative coexist, and (2) each one of them has a range of different functions. For example, despite there being only few tokens, all four uses of the complex demonstrative are represented, partly overlapping with the uses of the simple demonstrative and partly newly emerged. This corroborates the view of the Definiteness Cycle as part of a grammaticalization trajectory in which forms do not rise and fall in neat pathways as one function leads to the next, but sometimes undergo detours and sidetracks, producing extended uses that linger along the way. It remains to be seen what variegated functions the complex demonstratives serve in other dialects and how they may play into the building picture we have presented here on the evolution of the determiner system in English.

To conclude, we have documented the use of a complex demonstrative construction in a small city in northeast England, York, at the end of the twentieth century and provided a qualitative analysis of forms. The results add to the descriptive inventory of non-standard-determiners in English dialects and added new insights into the Definiteness Cycle and grammaticalization theory. Moreover, we have demonstrated the usefulness for multidisciplinary research, unifying language variation and change, historical linguistics and discourse-pragmatics, for advancing the understanding of how the construction evolved synchronically and diachronically.