1 Introduction

This article investigates English proper nouns used as premodifiers and their German and Swedish correspondences. The interest in such premodifiers reflects ongoing changes in English that may also be affecting the other languages. In English, premodifying nouns have tripled over the last two centuries (Biber, Grieve & Iberri-Shea Reference Biber, Grieve, Iberri-Shea, Rohdenburg and Schlüter2009: 187), and proper nouns are increasing in frequency in writing, a change which is particularly noticeable with acronyms (Leech et al. Reference Leech, Hundt, Mair and Smith2009: 212). Other languages have been discussed as points of comparison in some of the previous studies on English proper noun modifiers. Koptjevskaja-Tamm (Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Börjars, Denison and Scott2013) contrasts Swedish usage with English, Zifonun (Reference Zifonun, Scherer and Holler2010) and Schlücker (Reference Schlücker2013: 464–5) compare German with English, while Breban (Reference Breban2018: 393) contains observations on Dutch and German. Instead of proper noun modifiers, German and Swedish use either solid or hyphenated compounds.Footnote 1 Such compounds appear to be on the increase also in German (Zifonun Reference Zifonun, Scherer and Holler2010) and Swedish (Koptjevskaja-Tamm Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Börjars, Denison and Scott2013). However, in spite of these previous comparative approaches and potential cross-linguistic influences, no large-scale systematic contrastive study has been conducted so far.

Example (1) illustrates the English proper noun modifiers found in the Linnaeus University English–German–Swedish Corpus (LEGS) and the kinds of translation strategies available in German and Swedish. Modifiers referring to organizations (Yale) and places (US) are here rendered as prepositional phrases (einen Juraabschluss in Yale), left-hand (non-head) elements of compounds (Rhodesstipendium) and genitives (USA:s president). These translations show that German and Swedish share many structural means for translating proper noun modifiers.

(1) President Clinton had the self-control […] to win a Rhodes scholarship, attain a Yale law degree, and be elected to the U.S. presidency, apparently combined with little desire […] to exert self-control for particular temptations like junk food and attractive White House interns. (LEGS; English original)

Präsident Clinton besaß die Selbstkontrolle […] um eines der renommierten Rhodes-Stipendien [‘one of the prestigious Rhodes-scholarships’] zu ergattern, einen Juraabschluss in Yale [‘a law degree at Yale’] zu machen und zum US-Präsidenten [‘US-president’] gewählt zu werden. Anscheinend in Verbindung mit einem nur schwach ausgeprägten Verlangen […] sich bei bestimmten Verlockungen wie Junkfood und attraktiven Praktikantinnen im Weißen Haus [‘attractive interns in-the White House‘] in Selbstbeherrschung zu üben. (German translation)

President Clinton hade självkontroll […] som förlänade honom ett Rhodesstipendium [‘a Rhodes-scholarship’], lät honom ta en juristexamen vid Yale [‘a law degree at Yale’] och bli vald till USA:s president [‘USA's president’], uppenbarligen kombinerad med ringa önskan […] att utöva självkontroll inför vissa frestelser som skräpmat och attraktiva Vita hus-praktikanter [‘attractive White-House-interns‘]. (Swedish translation)

The aim of this article is to investigate English proper noun modifiers denoting organizations, people and places. The following research questions will be addressed:

(i) What German and Swedish structures are used to render English proper noun modifiers denoting people, places and organizations in translations?

(ii) How do the semantic types of the proper nouns affect translations?

(iii) What German and Swedish structures are translated into English proper noun modifiers?

This study is based on a parallel corpus of popular non-fiction texts with English originals and translations from German and Swedish. The material has different advantages for the aims at hand: the corpus is consistently trilingual, its texts are recent and it contains a genre that promotes the use of proper noun modifiers.

The outline of this article is as follows. Section 2 presents previous work on English proper noun modifiers with a particular focus on comparisons with German and Swedish. Section 3 outlines the material and methods used. Section 4 presents the results, section 4.1 giving an overview of the German and Swedish correspondence types, section 4.2 focusing on the frequencies of these types in English originals and translations, and section 4.3 showing the German and Swedish correspondences of English proper noun modifiers. Section 4.4 investigates the extent to which the German and Swedish correspondences are (non-)congruent, section 4.5 presents the correlations between semantic types and translations, section 4.6 discusses the German and Swedish structures rendered as English proper noun modifiers, and finally, section 4.7 addresses how noun phrase complexity impacts translation strategies.

2 Background

While English prefers juxtaposed N + N sequences (Rhodes scholarship), German and Swedish lack this option and instead use compound nouns (Rhodesstipendium) (regarding hyphenation, see footnote 4). Despite these formal differences, the two constructions are discussed in a similar vein in previous work on proper noun modifiers. Thus, Koptjevskaja-Tamm (Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Börjars, Denison and Scott2013: 256) in her seminal work on Swedish ‘proper name compounds’ (Mozartsonat) refers to constructions where the nouns are juxtaposed such as the Obama government as ‘the English correspondence to PropN-compounds in Swedish’, and, according to Zifonun (Reference Zifonun, Scherer and Holler2010: 168), the increasing use of German compounds is strongly influenced by the English counterpart (see below).

Premodifying proper nouns comprise different semantic types, denoting for example people, places and organizations. However, previous studies have largely focused on personal name modifiers, contrasting their use to the partly overlapping construction with a genitive determiner, e.g. the Bush administration versus Bush's administration mentioned by Rosenbach (Reference Rosenbach2007: 143). Rosenbach (Reference Rosenbach2007: 166) covers a wider range of types and her historical British English newspaper data from ARCHER suggest that place names were the first to be used as modifiers and still remain the most frequent category. Personal name modifiers are the rarest and only seem to have appeared in the twentieth century, while ‘collectives’ are of intermediate frequency. Rosenbach (Reference Rosenbach2007) is one of few studies based on a large data set, most previous studies having relied heavily on qualitative observations (see Breban Reference Breban2018: 383 on a similar note).

One consequence of the narrow focus on personal name modifiers is that acronyms which denote organizations (the NLF movement) and places (the US economy) have been overlooked. Conversely, those who have investigated the increasing use of acronyms, such as Leech et al. (Reference Leech, Hundt, Mair and Smith2009: 212–13), do not comment on the use of acronyms as premodifiers. However, because of their frequent use in our material, often as premodifiers, acronyms deserve special attention.

In some cases, common nouns modified by proper nouns (or their equivalent German and Swedish compounds) have instance reference and in others type reference.Footnote 2 For instance reference, Schlücker (Reference Schlücker2013: 461) provides the example (die) Wulff-Villa (‘the Wulff villa’), which identifies a specific villa as belonging to the Wulff family, and for type reference she gives Hitler-Bärtchen (‘Hitler moustache’), which does not refer to a specific moustache but to a subtype similar to that of Hitler's. Breban (Reference Breban2018: 390) concludes that the typifying use is very rare in her material from the Collins WordBanks Online corpus. Moreover, Rosenbach (Reference Rosenbach2007: 149) points to some ambiguous cases. The Major plan can both refer to a specific plan and to a typical plan made by John Major, suggesting that the two interpretations sometimes coexist or, as suggested by Schlücker (Reference Schlücker2013: 468), an instance reading may over time become ‘typified’.

Some contrastive observations have been made in predominantly monolingual studies, mainly comparing German or Swedish with English. Schlücker (Reference Schlücker2013: 465) observes that location-based proper noun modifiers are more common in English than the equivalent German compounds. German translations instead often use deonymic adjectives with the suffix -er derived from proper nouns, or prepositional phrases. An example of the former option is (the) Brussels landscape translated as (die) Brüsseler Landschaft (‘the Brussels-adj landscape’) and of the latter (the) New York stage translated as (die) Bühne in New York (‘the stage in New York’). According to Zifonun (Reference Zifonun, Scherer and Holler2010: 168), compounds such as die Kohl-Regierung (‘the Kohl government’) are less common in German than in English and largely restricted to German journalese (as also proposed by Campe Reference Campe, Lenz and Plewnia2010: 210). Otherwise German is more likely to use appositional structures (die Regierung Kohl (‘the government Kohl’)), and Swedish seems to share this preference (regeringen Erlander (‘the government Erlander’) from Teleman et al. Reference Teleman, Andersson and Hellberg1999: III, 120). Campe (Reference Campe, Lenz and Plewnia2010: 208) discusses the translation of (proper) noun compounds into less ‘compound-prone’ languages, suggesting that a genitive may be a more suitable option when, for example, translating from German into Dutch (‘van’-PP), i.e. ein Arsenal-Funktionär (‘an Arsenal-official’) translated as een functionaris van Arsenal. Apart from these structural and semantic differences, it has also been suggested that English unlike Swedish allows for recursiveness, meaning that the head in English, but not in Swedish noun phrases, can be complex or ‘heavy’, as argued by Koptjevskaja-Tamm (Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Börjars, Denison and Scott2013: 284–5) (a Mozart violin sonata as opposed to Swedish ???en Mozart-violinsonat) (see section 4.7).

3 Material and method

The Linnaeus University English–German–Swedish Corpus (LEGS) (Ström Herold & Levin Reference Ström Herold and Levin2018) consists of recently published (2010s for English originals, 2000s for German and Swedish originals) popular non-fiction texts in English, German and Swedish. The subgenres included (e.g. biographies, popular science, self-help books and books on history) are by necessity restricted to those that are read widely enough to be translated. As indicated by (1) above, the genre seems to be conducive to the use of English proper noun modifiers, but it has nevertheless not been covered in previous studies.

The corpus is balanced for the three languages, every original always being accompanied by two target texts, and each author and translator being represented only once. The corpus currently (version 0.2) comprises about 272,000 English source-text words, and 284,000 English words translated from German and 238,000 from Swedish. The present study is based on extracts from five books for each source language. The five English original texts are extensive, ranging from 300 to 900 pages, and therefore these corpus source-texts consist of extracts of about 50,000 words each (about 200 pages). Some of the German books are short, which means that the German originals comprise three complete texts and two extracts. The Swedish texts are the shortest and therefore five entire books were included, averaging slightly below 50,000 words each. There is a close, but not perfect match of the texts in the subcorpora – biographies and popular science books are represented in all three subcorpora, history books in English and German and self-help books in German and Swedish originals.

One of the main advantages of LEGS is that each source-text segment is aligned with two translations. This makes it possible to compare how the very same instance is translated into two target languages, thereby allowing identification of language-specific and translation-specific features. A further advantage is that the corpus consists of non-fiction texts, which minimizes the incidence of author-specific, idiosyncratic features.

Using Laurence Anthony's parallel corpus tool AntPConc,Footnote 3 a tagged version of the corpus was searched for English proper nouns immediately followed by common nouns in both originals and translations. The material for this study only covers instances where the English original or translation contains a proper noun + a common noun. Thus, instances consisting of, for example, the simple English noun administration rendered as the explicitated German compound Obama-Regierung fall outside the scope.

Our study excludes the rare instances with intervening elements between the nouns (University of Leeds ecological economist). Furthermore, instances such as [Stanford] + [University] where the second noun is part of the proper noun are not included unless immediately followed by a common noun ([Stanford University] + [undergraduates]). These delimitations differ slightly from those in previous studies. Apart from her categories ‘human’ (Bush administration), ‘collective’ (FBI director) and ‘locative’ (Ghana government), Rosenbach (Reference Rosenbach2007: 165–6) also includes time (Saturday review) and other inanimates (Fox [ship name] privateer). Koptjevskaja-Tamm (Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Börjars, Denison and Scott2013) is restricted to personal names and Breban (Reference Breban2018: 389) includes examples of the Stanford University type but excludes a type we include, examples such as a Chunnel shuttle loading dock, where the second noun (shuttle) itself is a modifier.

The irrelevant hits were weeded out, and all examples were classified jointly by both authors. Typical instances of personal names in this study refer to individuals (Wordsworth), but some also refer to groups (Adamczyk (family)). Place names typically denote countries (US) or cities (Pittsburgh), and less commonly other kinds of locations (Hampshire; (the) Black Sea). The organization names cover multinational organizations (UN), military units (RAF), brands (Braun) and company names (Apple). In all, 583 English source-text instances translated into German and Swedish were included in the study, and 270 instances translated from German and 187 from Swedish.

4 Results

4.1 Translation categories identified in the material

Twelve different correspondence types were identified in the German and Swedish translations, and two additional categories in the German and Swedish originals. Three of the categories – compound noun, genitive and prepositional phrase – account for the majority of instances. The following sections will therefore mainly concern these three with some brief comments on the minor correspondences conflated into the ‘Other’ category.

Example (2) below exemplifies the structurally most similar correspondence, German and Swedish compound nouns, where the English proper noun modifier corresponds to the first part of the compound. In German and Swedish, compounds are written either with hyphens (as in the German translation in (2)) or solid (as in the Swedish translation).Footnote 4 Example (3) illustrates genitives, which are usually postposed in German and always preposed in Swedish. (4) contains an English proper noun modifier rendered into postmodifying prepositional phrases in German and Swedish.

Compound

(2) Rolex watches (LEGS; English original)

Rolex-Uhren (German translation) [‘Rolex-watches’]

Rolexklockor (Swedish translation) [‘Rolex-watches’]

Genitive

(3) the Obama presidency (LEGS; English original)

der Amtszeit Obamas (German translation) [‘Obama's presidency’]

Obamas presidentperiod (Swedish translation) [‘Obama's presidency’]

Prepositional phrase

(4) in his Palo Alto garden (LEGS; English original)

in seinem Garten in Palo Alto (German translation) [‘in his garden in Palo Alto’]

i sin trädgård i Palo Alto (Swedish translation) [‘in his garden in Palo Alto’]

Most of the other categories are rare. Adjectives mostly occur as correspondences of place-name acronyms, as in (5). Example (6) illustrates the translation of English proper noun modifiers into adverbials. Compared to postmodifying prepositional phrases exemplified in (4), adverbials are a minor category. As in the present study, Levin & Ström Herold (Reference Levin, Ström Herold, Egan and Dirdal2017: 162) found that English premodifiers are only rarely transposed into German and Swedish adverbials. The instances we refer to as apposition involve restrictive apposition, exemplified in (7) (cf. Teleman et al. Reference Teleman, Andersson and Hellberg1999: III, 120; Campe Reference Campe, Lenz and Plewnia2010: 195; Zifonun Reference Zifonun, Scherer and Holler2010: 178). Extended attributes consist of participles or adjectives taking one or more complements (cf. Fagan Reference Fagan2009: 125). This is seen in (8) where a participle has been added in the translation. Loans, as in (9), involve cases where the original English proper noun and head are transferred verbatim to the target language.Footnote 5 In omissions, all the information relating to the proper noun and its head is lost. This is exemplified in (10) where the translation omits an entire sentence containing a noun phrase with a proper noun modifier. In paraphrases, illustrated in (11), the information is retained but restructured into finite clauses. The reduction category is particularly interesting from a translation perspective. In these instances either of the constituents of the English noun phrase is omitted. In (12) the noun phrase is thus reduced to the head noun and in (13) the proper noun modifier is shifted into the head. In some rare cases, the English proper noun modifier has been moved to a postmodifying relative clause, as in (14).

Adjective

(5) none of our UK bees (LEGS; English original)

keiner der britischen Hummelspezies (German translation) [‘none the-gen British bumblebee-species’]

Adverbial

(6) found an Oregon midwife (LEGS; English original)

engagierten in Oregon eine Hebamme (German translation) [‘hired in Oregon a midwife’]

Apposition

(7) the Merkel government (LEGS; English original)

die Regierung Merkel (German translation) [‘the government Merkel’]

regeringen Merkel (Swedish translation) [‘the government Merkel’]

Extended attribute

(8) a Los Angeles psychotherapist named Arthur Janov (LEGS; English original)

dem in Los Angeles praktizierenden Psychotherapeuten Arthur Janov (German translation) [‘the in Los Angeles practising psychotherapist Arthur Janov’]

Loan

(9) large amounts of Cragmont cream soda (LEGS; English original)

stora mängder Cragmont Cream Soda (Swedish translation) [‘large amounts of Cragmont Cream Soda’]

Omission

(10) You might by now be wondering as to the relevance of the Darwin quotation at the start of this chapter. (LEGS; English original)

Ø (German translation)

Paraphrase

(11) as Luftwaffe attacks on Britain mounted (LEGS; English original)

Luftwaffe genomförde allt fler anfall mot Storbritannien (Swedish translation) [‘Luftwaffe launched more and more attacks on Britain’]

Reduction

(12) the Mac office (LEGS; English original)

kontoret (Swedish translation) [‘the office’]

(13) a Picasso painting (LEGS; English original)

einem Picasso (German translation) [‘a Picasso’]

Relative clause

(14) shooting for Museum of Modern Art quality (LEGS; English original)

med sikte på en konstnärlig kvalitet som skulle platsa på Museum of Modern Art (Swedish translation) [‘with the aim of an artistic quality that would qualify in the Museum of Modern Art’]

Extension and addition occur in translations into English. These explicitation strategies (for explicitation, see Blum-Kulka Reference Blum-Kulka, House and Blum-Kulka2004 [1986]: 292) are the mirror images of reduction and omission. In extensions, translators add an English proper noun modifier to the translation that was not present in the original (see (15), where the modifier CDU is added), while in additions both a head noun (professor) and its modifier (Harvard) are included, as in (16).

Extension

(15) ins Parteiprogramm (LEGS; German original) [‘into-the party-manifesto’]

in the CDU party manifesto (English translation)

Addition

(16) Ø John Kenneth Galbraith (LEGS; Swedish original)

Harvard professor […] John Kenneth Galbraith (English translation)

It is not only extensions, additions, reductions and omissions that affect the degree of explicitness; this also holds true for the other translation categories above. For example, prepositional phrases and relative clauses clarify the relationship between the noun-phrase parts, while German and Swedish compounds and adjectives are as (in)explicit as the English proper-noun noun phrases.

The German and Swedish translations / translation categories are also compared to each other (see section 4.5). As in Ström Herold & Levin (Reference Ström Herold and Levin2018: 117), the term ‘congruent’ is used to refer to instances where the two translations belong to the same structural category, such as both being compounds, and ‘non-congruent’ when they belong to different categories such as a German genitive and a Swedish prepositional phrase.

Section 4.2 below presents the distributions of English originals and translations from German and Swedish.

4.2 English originals and translations from German and Swedish

In the LEGS corpus, English proper noun modifiers are more than twice as common in English originals (21.4/10,000 words; 583 instances) as in translations from German (9.5/10,000; 270 instances) and Swedish (7.9/10,000; 187 instances). The substantial differences between individual texts and genresFootnote 6 seen in figure 1 are consistent both within and across the subcorpora.

Figure 1. Raw frequencies of English proper noun modifiers per text

The highest frequency of English proper noun modifiers in each subcorpus is found in biographies. The main reason for their frequent use in biographies is that this genre contains many names of companies, brands and organizations relevant to the people portrayed (the first Macintosh computer, SPD politician, the hard-line VAM activists). Proper noun modifiers are also quite frequent in the two books on history (English original and translation from German), but consistently rare in popular science. The English and German books on (World War) history frequently mention military organizations and geographic locations (RAF airfields, the Smolensk region), while the popular science texts deal with physiology, psychology and ecology – topics that do not seem to be conducive to the use of proper noun modifiers. The rare examples that occur relate to names of universities (the Columbia studies) or places (in Dalarna province). A further notable finding is that the highest frequencies for individual texts for biographies, history and popular science all occur in the English originals. The tendency for higher frequencies in originals will be discussed in section 4.6.

In figure 1 we saw that English originals differ considerably from translations frequency-wise. The distributions of semantic types in figure 2 present a similar picture. The distribution is very different in the originals compared to the translations. The translations are not significantly different from each other, but both are significantly different from the English originals.Footnote 7 The preference for place names in translations from German largely originates in one text, and the preference for place names in translations from Swedish in two. More studies are needed to verify to what extent the distributions seen in the translations hold true for other translated texts. The low frequency of personal names is nevertheless established for all three subcorpora, as for Rosenbach's (Reference Rosenbach2007: 166) British newspaper material. The preference in LEGS for organization names instead of place names in English originals is nevertheless very different from Rosenbach's results. Only one (popular science) text of our five English originals conforms to Rosenbach's distributions of place names being more frequent than organizations.Footnote 8 It is not immediately clear what causes these differences. It could be a reflection of genre preferences (newspapers in ARCHER and non-fiction in LEGS) or diachronic change (Rosenbach's most recent time interval being 1950–99). Newspapers may promote certain creative place name modifiers that are rare in popular non-fiction. An example of this is Salisbury poisoning (The Sun, 3 April 2018), where the noun phrase is used to refer to a current newsworthy event having occurred in Salisbury. Such naming practices would seem to be particularly frequent in headlinese (see Breban (Reference Breban2018: 392), who records a large number of examples in newspaper headlines).

Figure 2. Semantic types in English originals and translations from German and Swedish

Related to the frequent use of organization names is the frequency of acronyms. In the English originals, 17.7 per cent of the proper nouns are acronyms, which is significantly lower than in the translations from German (28.9 per cent) and Swedish (24.6 per cent).Footnote 9 Although acronyms are less frequent in translations into English than in English originals, they account for larger proportions in the translations. The frequent German use of acronyms in compound nouns (cf. Fleischer & Barz Reference Fleischer and Barz2012: 283) probably promotes the frequency in translations from German. As will be seen in the following sections, the use of acronyms is one of the factors influencing translation choices.

4.3 German and Swedish translation correspondences of proper noun modifiers

The distributions of German and Swedish translations are given in table 1. The three major categories compound, genitive and prepositional phrase account for a large majority of the instances in both target languages, which suggests that German and Swedish have fairly similar preferences in spite of noteworthy differences in the proportions.

Table 1. German and Swedish translations of English proper noun modifiers

Compounds are by far the most frequent correspondences in German and more narrowly so in Swedish translations. The similarity between English N + N sequences and German and Swedish compound nouns facilitates ‘word-for-word’ translation, and such structures are therefore obvious solutions for translators. An additional factor promoting the use of German and Swedish compounds is that compounds allow a wide range of interpretations and therefore are highly context-dependent, as argued by Campe (Reference Campe, Lenz and Plewnia2010: 210). By adhering to a structure that is more or less as semantically opaque as the English N + N sequences, translators can avoid having to pin down the exact meaning relationship in the translation. Compounds are nevertheless used in fewer than half of the German instances and a third of the Swedish ones, which shows that German and Swedish compounds are by no means one-to-one correspondences of English proper noun modifiers and their heads. It is possible that the typification effect of compounds in German and Swedish is stronger than in English noun phrases modified by proper nouns. Examples of this potential difference in typification are given in (17) and (18). In both target languages, the English original in (17) is rendered as prepositional phrases and in (18) as genitives.

(17) The Yale researchers (LEGS; English original)

Die Forscher aus Yale (German translation) [‘the researchers from Yale’]

Forskarna vid Yale (Swedish translation) [‘the researchers at Yale’]

(18) the total Luftwaffe loss (LEGS; English original)

der Gesamtverlust der Luftwaffe (German translation) [‘the total-loss the-gen Luftwaffe’]

Luftwaffes sammanlagda förluster (Swedish translation) [‘Luftwaffe's total losses’]

Compounds are syntactically possible alternatives in both cases but are semantically or pragmatically less likely. Google searches indicate that the German compound alternative for (17) (Yale-Forscher) is about as frequent as the prepositional phrase, but the Swedish compound (Yale-forskarna) is much rarer than the prepositional option. German and Swedish compounds for (18) (?Luftwaffe-(gesamt)verlust; ?Luftwaffe(-)förluster) are virtually non-existent, and if they did exist, type readings would be likely. Cultural factors may also be at play. Compounds seem more likely with domestic, well-established names of organizations, while foreign ones are disfavoured. For example, researchers from the Swedish universities at Lund and Uppsala are more often referred to as Lundaforskare and Uppsalaforskare than forskare från Lund/Uppsala, according to Google searches.

The second-most-used correspondence, the genitive, expresses a subset of the meanings that are possible with compounds. We thus find cases where a compound or a genitive are interchangeable, as when the Luftwaffe attack can be rendered in German as Luftwaffe-Angriff or Angriff der Luftwaffe. However, there are also cases where the genitive would be precluded as an alternative to a compound. The German compound Norwegenfeldzug is unproblematic as the correspondent of the Norway campaign (i.e. ‘the German invasion of Norway’), while the genitive option *Feldzug Norwegens is unavailable.Footnote 10

The third-most-frequent alternative, the prepositional phrase, is the most explicit and least condensed of the three major target-text constructions. Translations are thus affected by the tension between practical expediency and a desire for condensed information on the one hand and a tendency towards explicitation on the other. Of the prepositions in prepositional phrases, German mostly uses either von [‘of, from’] (36/85; 42%) or in [‘in’] (25/85; 29%), while Swedish relies about almost equally heavily on the two prepositions i [‘in’] (65/138; 47%) and från [‘from’] (21/138; 15%).Footnote 11 These preferences indicate that prepositional phrases largely relate to locations, as illustrated in (19):

(19) the Fukushima disaster (LEGS; English original)

der Katastrophe von Fukushima (German translation)

katastrofen i Fukushima (Swedish translation)

While the Swedish i has a locative function, the German von is part of a cline where in is the most clearly locative, expressing where something happened (die Katastrophe in Fukushima), whereas a compound names the event (die Fukushima-Katastrophe). The prepositional phrase with von in (19) forms a middle ground, partly expressing place and partly naming the incident with a meaning similar to English of, as in the battle of Waterloo. The varied meanings of von are discussed by Schlücker (Reference Schlücker2013: 454), who suggests that German von has a localizing/anchoring as well as a qualifying function. Google searches (12 April 2018) indicate that there is an ongoing shift in German away from in towards von and the noun compound to refer to the events in Fukushima in that there is an increased use of naming (‘Fukushima disaster’) rather than description (‘the disaster in Fukushima’).

In the Other category, the three most common correspondence types, adjective, reduction and apposition, merit some brief comments. Adjectives are more common in German than in Swedish translations due to a more frequent use of adjectives related to place names. German translators use place name adjectives where the Swedish either use prepositional phrases or genitives (US politics > in der amerikanischen Politik (German) / USA:s politik (Swedish)). In addition, in 11 instances German translators resort to deonymic adjectives (as suggested by Schlücker Reference Schlücker2013: 465), an option not available in Swedish (the Warsaw government > die Warschauer Regierung (German) / Warszawa-regeringen (Swedish)).

The correspondence type referred to as Reduction is an implicitation strategy (Ingo Reference Ingo2007: 124) used when the omitted parts can either be (i) inferred from the immediate context, (ii) expected to be known by readers, or (iii) expected to be unknown or less important to readers. The English noun phrase in (20) is the fourth mention of the borough in that paragraph, which means that hardly any information is lost in the translation. In (21), the German warplane is at least as well known in the target-language culture as in English and is conventionally referred to only as Stuka (short for Sturzkampfflugzeug) in German.Footnote 12 The brand of the juicer in (22) is only mentioned in passing. It is not highly relevant for the narrative and largely unknown in the target-language cultures and can thus be omitted without considerable information loss. In about half the examples of reductions, it is the proper noun that has been left out, and in about half the head noun.

(20) Once inside the Bronx school, […] (LEGS; English original)

Kaum hatte ich die Schule betreten, […] (German translation) [‘hardly had I entered the school’]

(21) the Stuka divebombers (LEGS; English original)

seine Stukas (German translation) [‘his Stukas’]

(22) he got a Champion juicer (LEGS; English original)

er besorgte sich einen Entsafter (German translation) [‘he got himself a juicer’]

skaffade han en mixer (Swedish translation) [‘he got a blender’]

The German and Swedish use of restrictive apposition in translations is quite similar. Of the 24 German and 31 Swedish instances, 15 are translated congruently into appositions in both languages (see (7) above), which indicates that there is a high degree of similarity in German and Swedish usage preferences. (The (non-)congruency of translations is discussed in detail in section 4.4.)

The distributions in table 1 are visualized in figure 3 with indications of the levels of statistically significant differences.

Figure 3. German and Swedish translations of English proper noun modifiers

There are two significant findings: compounds are more common in the German than in the Swedish translations, while prepositional phrases are more frequent in Swedish. Similarly, non-significant tendencies for more compounds in German and more prepositional phrases in Swedish translations are observed by Levin & Ström Herold (Reference Levin, Ström Herold, Egan and Dirdal2017: 162, 168–70) for translations of English hyphenated premodifiers such as six-inch nails. Moreover, Carlsson (Reference Carlsson2004: 75) found two-part compound nouns to be used significantly more often in German than in Swedish newspapers. There are three potential factors for the higher frequency of compounds in German in the LEGS data: (i) a greater German tolerance for ad hoc compounds (see Carlsson Reference Carlsson2004: 138)Footnote 13 (which may be linked to compounds having a weaker typifying effect in German than in Swedish, as seen in, for instance, (18) above), (ii) acronyms more often being used as left-hand elements in German compounds (see Levin, Ström Herold & Tyrkkö, in prep.)Footnote 14 and (iii) heavy head compounds being allowed in German (see Koptjevskaja-Tamm Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Börjars, Denison and Scott2013: 284–5 and section 4.7 below).

One of the German ad hoc compounds is given in (23), referring to Britain's failed attempt to stop the 1940 Nazi invasion of Norway. An ad hoc compound is also possible in Swedish (Norgefiaskot) but is more likely to occur in condensed and creative headlinese, as indicated by Google searches (e.g. the headline Saabs Norgefiasko from the newspaper Svenska Dagbladet (svd.se)).

(23) the Norway fiasco (LEGS; English original)

das Norwegen-Fiasko (German translation)

fiaskot i [‘in’] Norge (Swedish translation)

It should be noted that some Swedish compounds in the Swedish translations are potential examples of translationese (Gellerstam Reference Gellerstam, Wollin and Lindquist1986), decreasing the difference between the languages. For instance, the NKVD man and an HP engineer are rendered as the Swedish compounds NKVD-mannen and en HP-ingenjör, which come across as marked translations to the present authors, an assessment which is supported by Google searches.Footnote 15

Regarding the second tendency, Fleischer & Barz (Reference Fleischer and Barz2012: 283) argue that acronyms are particularly common in German compounds (AOK-Mitglied (‘AOK member’)). Fleischer (Reference Fleischer1997: 189) (cited in Fleischer & Barz Reference Fleischer and Barz2012: 284) suggests that the frequent use of acronyms in compounds can be explained by their compressed form. Thus, DRK-Mitglied (‘DRK member’) is more flexible than its full-form pendant, *Deutsches-Rotes-Kreuz-Mitglied (‘German Red Cross member’). In contrast to German, Swedish acronym compounds are more marginal; in 20 cases, Swedish translators use genitives when German translators use compounds, as exemplified in (24).

(24) the WTO ruling (LEGS; English original)

die WTO-Entscheidung (German translation)

WTO:s beslut (Swedish translation)

This section has discussed differences between German and Swedish correspondences at the corpus level. Section 4.4 investigates to what extent German and Swedish translators choose congruent translations.

4.4 (Non-)congruent German and Swedish translations

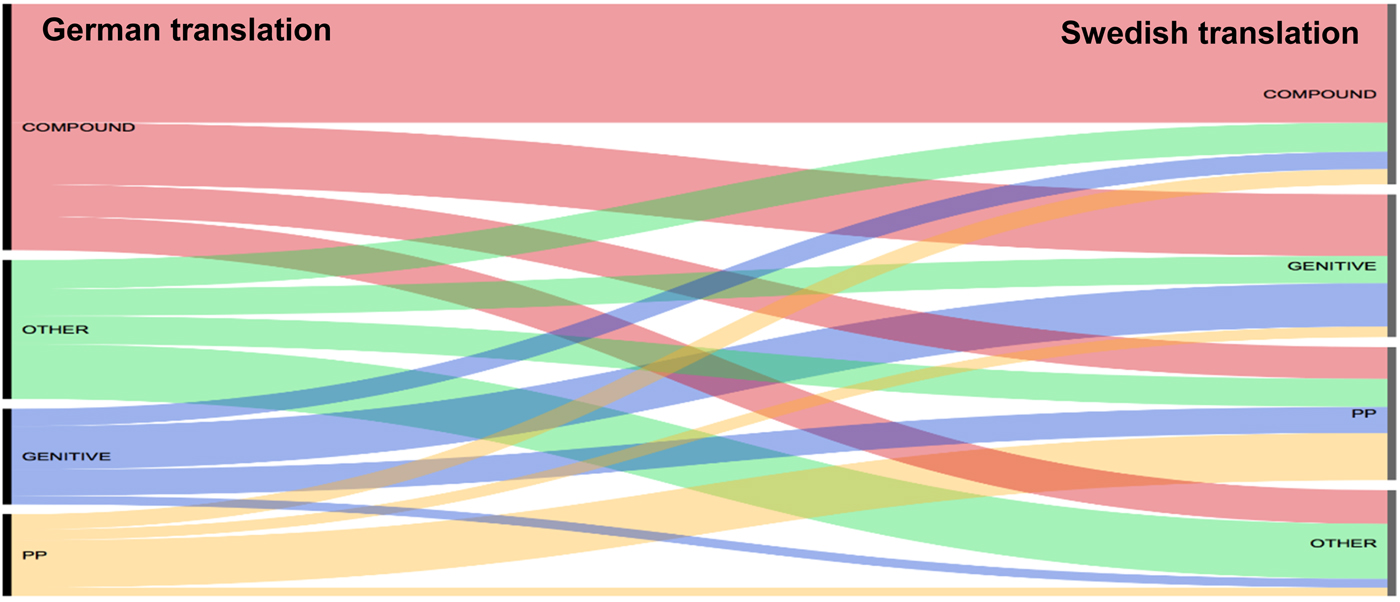

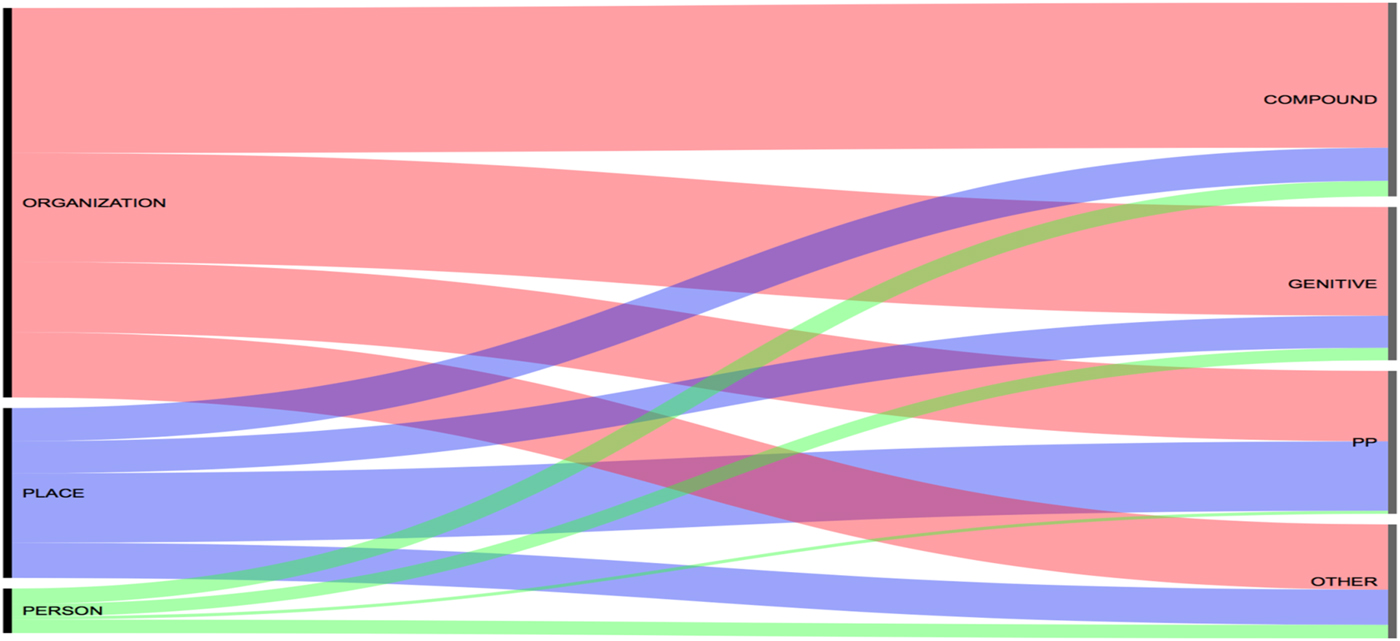

The alluvial chart in figure 4 compares the degree of congruent translations in German and Swedish. The largest number of congruent translations occurs in the most frequent category, compounds, which indicates a certain degree of overlap in the uses of compounds in the two target languages. Perhaps surprisingly, the second highest proportion is found in the Other category. This is partly due to some spurious instances where, for instance, an English modifier has been translated into a German relative clause and a Swedish adverbial, and partly to congruent instances occurring with the most frequent subcategories discussed above: adjectives (9 instances), appositions (15 instances) and reductions (6 instances). Prepositional phrases and, in particular, genitives produce lower levels of congruency, as will be discussed below.

Figure 4. Comparison between German and Swedish translations of English proper noun modifiers

We approached the task of comparing the German and Swedish translations as an analogy to interrater reliability analysis. Although the two target languages are different, the fact that translations of the same original are analysed, and that the two target languages are typologically closely related and therefore offer the same choices, makes this methodology feasible. In this setup, we thus compare agreement between two sets of paired variables that have an equal number of the same nominal levels.

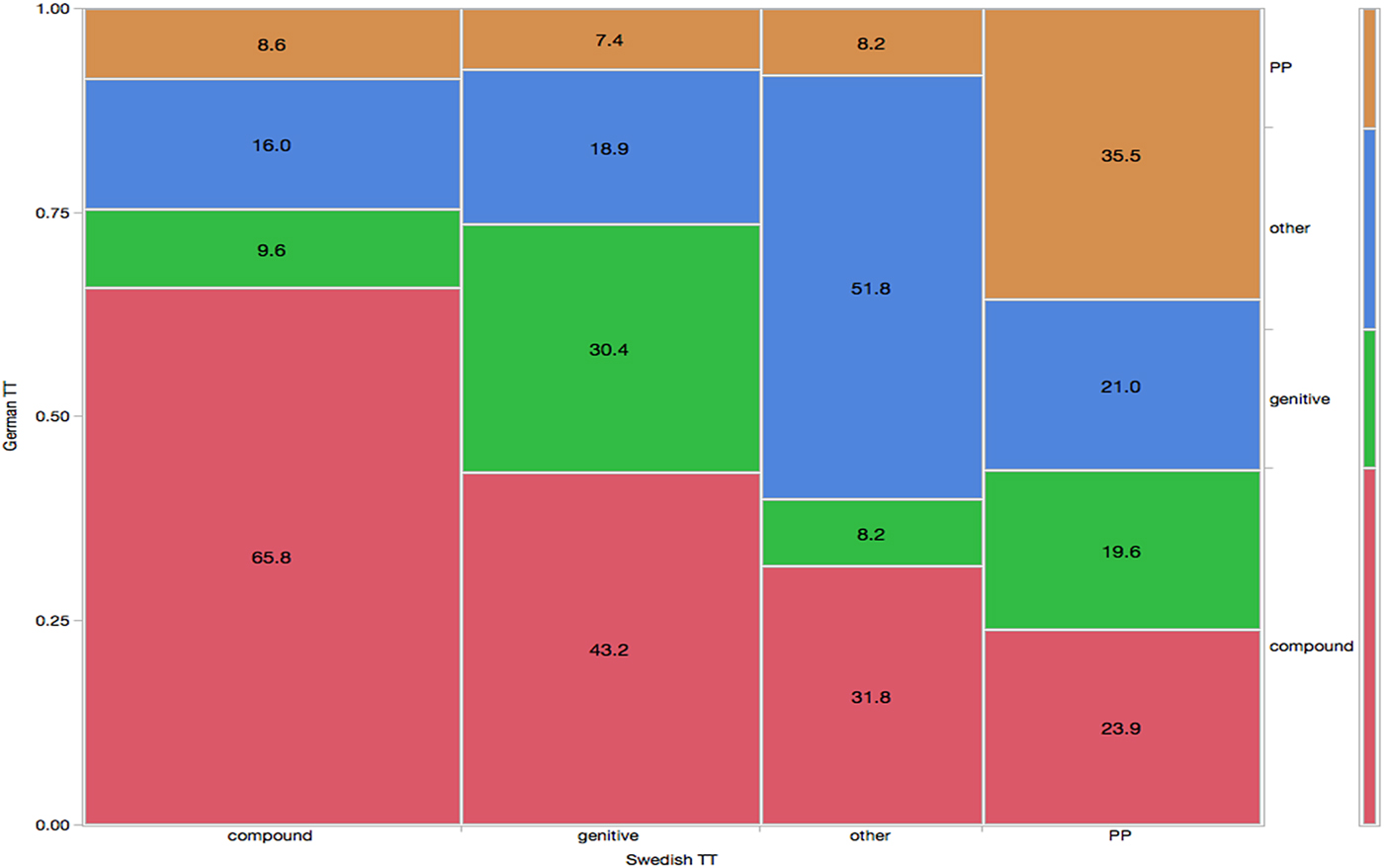

Cohen's kappa (ϰ), also known as the kappa coefficient, usually measures the precision, or agreement, between scores given by two raters (Cohen Reference Cohen1960). In the comparison of the 583 German and Swedish translations, Cohen's test gives us a kappa value of 0.279 (p = ***),Footnote 16 indicating that the two target languages show slight agreement but that the agreement is not merely coincidental. The proportions of agreement for each item can be seen in the mosaic plot in figure 5. The Swedish translations are shown on the x-axis and the German on the y-axis. The bottom left box indicates that almost two- thirds (65.8) of all Swedish compounds are also rendered as German compounds, and the top right corner indicates that more than one-third (35.5) of all Swedish prepositional phrases are also represented by prepositional phrases in German.

Figure 5. Mosaic plot of (non-)congruent German and Swedish translations of English proper noun modifiers

Compounds show the greatest value for congruent translations (65.8), while genitives show the lowest (30.4). The large proportion of congruent translations for compounds suggests not only that compounds are the most frequent correspondence type in the target languages, but also that German and Swedish compounds are preferred in similar contexts. The low correlation between German and Swedish genitives is an effect of genitives typically being resorted to in Swedish translations when a compound would be marginal, disallowed (see section 4.7 on heavy head compounds) or is in competition with a conventionalized target-language correspondence. German and Swedish prepositional phrases as correspondences of English proper noun modifiers will be discussed further in the next section.

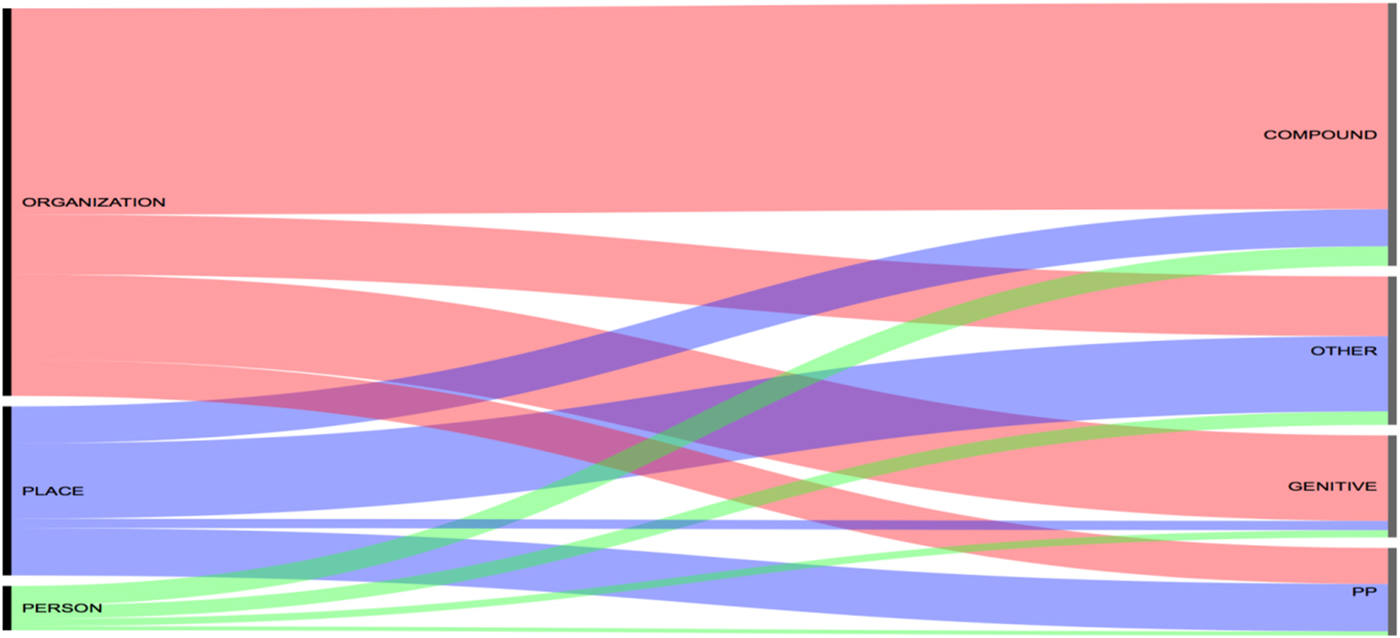

4.5 Semantic types and translations

Figures 6 and 7 show the correlations between semantic types and translations. There are significant findings for modifiers based on organizations and places, but not for the smallest category, person-based modifiers. In the German data, there are significant differences for every correspondence category (compound, genitive, prepositional phrase and Other) for modifiers based on organizations and places. For the translations into Swedish, compounds and prepositional phrases show significant differences for organizations and places.Footnote 17 There is a highly significant preference in both target languages for organization-based English proper noun modifiers to be translated into compounds, and for those based on place names to be translated into prepositional phrases. Many organization name modifiers can readily be translated word-for-word into German and Swedish compounds (the Stanford studies > der Stanford-Studien; Stanfordstudierna). Thus, compounds are here ‘default’ translations, and translators usually choose other alternatives only when special conditions apply. For Swedish, this can concern acronyms, as discussed above, and for German this may involve proper nouns consisting of more than one word. This is exemplified in (25), where ?Harvard-Medical-School-Studie would be marginal.

(25) a 2009 Harvard Medical School study (LEGS; English original)

einer Studie der [gen] Harvard Medical School von 2009 (German translation)

Figure 6. German translation correspondences according to semantic types

Figure 7. Swedish translation correspondences according to semantic types

The German preference for prepositional phrases with location-based modifiers is in line with Schlücker's suggestion (Reference Schlücker2013: 465) about the translation preferences for such modifiers. The significant German preference for Other correspondences with location-based modifiers also supports Schlücker's second proposal regarding adjectives being frequent with location-based modifiers. Of 164 instances based on place names, 35 (21%) are translated into German adjectives.

We also tested the congruency between the German and Swedish translations with the semantic types. The results show that congruency differs depending on whether the modifier denotes an organization, a person or a place. Translations of place names show the highest congruency level while translations of person names show the lowest.Footnote 18

4.6 German and Swedish structures rendered as proper noun modifiers in English translations

Table 2 presents the German and Swedish structures translated into English proper noun modifiers. In contrast to table 1 above, there are no adverbials and relative clauses, nor loans, omissions and reductions, which, by definition, do not occur in translations into English because of our search string being restricted to occurrences of proper nouns preceding common nouns in the English texts. Instead of omissions and reductions, their ‘mirror images’, additions and extensions, occur.

Table 2. German and Swedish source-text structures translated into English proper noun modifiers

Only the Other category produces a significant difference between the originals.Footnote 19 This is a result of appositions, adjectives and additions being more common in German originals. At least the stronger preferences for appositions and adjectives can be explained by language-specific norms. Some appositions, such as (26), are also frequently used in Swedish (as in (7) above), but for many German place-name instances, such as (27), Swedish does not allow appositions (*området Warszawa) and instead use other structures such as compounds. The difference regarding adjectives is partly related to German deonymic adjectives, as seen in (28).

(26) Die Regierung Schröder (LEGS; German original)

The Schröder administration (English translation)

(27) im [‘in-the’] Raum Warschau (LEGS; German original)

the Warsaw area (English translation)

(28) ins Pariser Stadthaus (LEGS; German original) [‘into-the Paris-adj townhouse’]

the Paris townhouse (English translation)

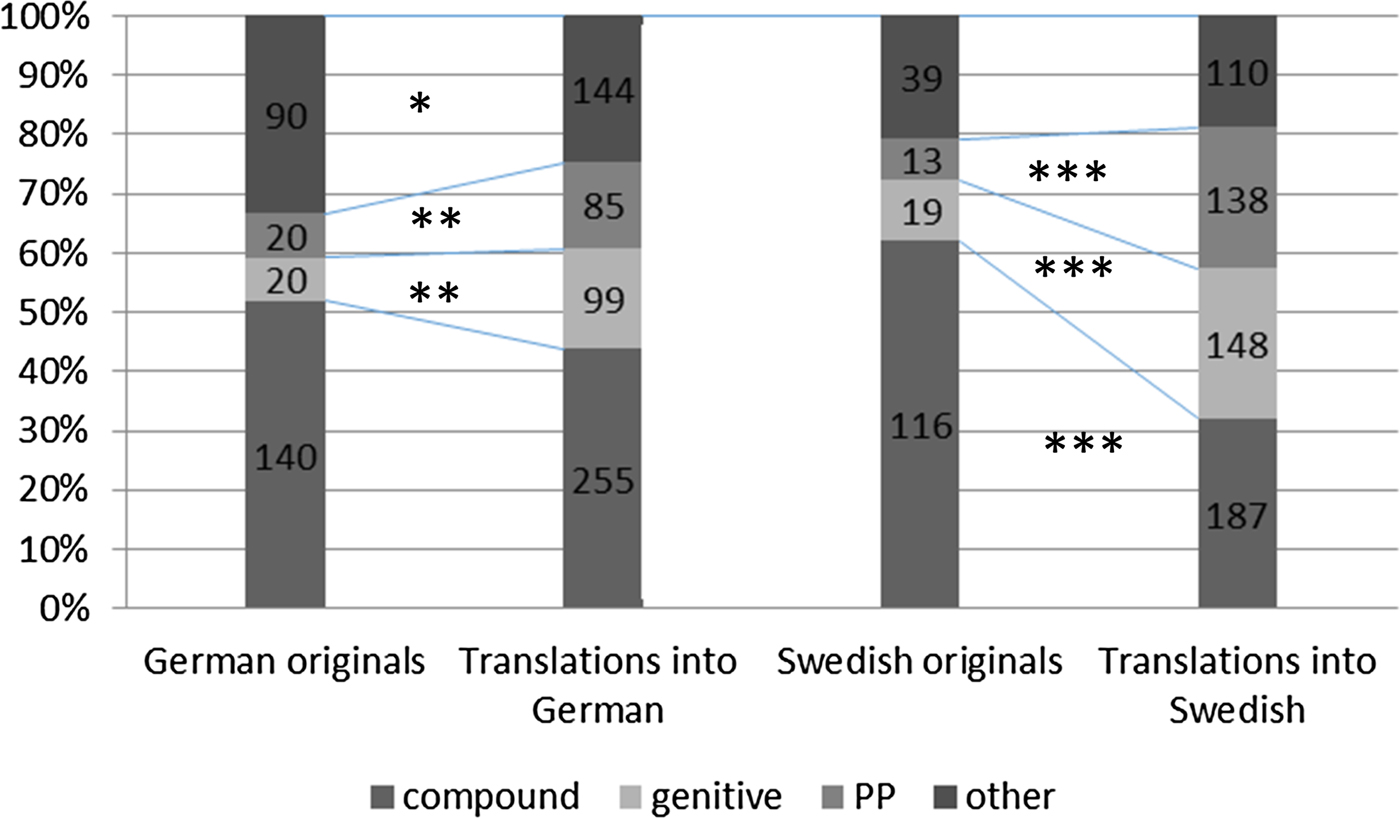

Figure 8 compares results from tables 1 and 2, showing that there are significant differences between originals and translations in most categories,Footnote 20 and also that there are similarities between the two translation directions. English proper noun modifiers are even more frequently translated into, than from compound nouns. A translation from a German or Swedish compound into an English proper noun modifier seems like a default translation option (Stalingrad-Katastrophe (German) > Stalingrad catastrophe; Vietnamdemonstrationerna (Swedish) > Vietnam demonstrations). This difference is highly significant for Swedish but not significant for German. Furthermore, English proper noun modifiers may often be translated into German and Swedish genitives and prepositional phrases, but they are very rarely translated from such structures into English. Similarly, Levin & Ström Herold (Reference Levin, Ström Herold, Egan and Dirdal2017) found that German and Swedish postmodifiers are rarely translated into English premodifiers. Finally, English proper noun modifiers are slightly more often translated from, than into, the Other category, a difference which is weakly significant for German.Footnote 21

Figure 8. Correspondences of English proper noun modifiers in German and Swedish originals and translations

German and Swedish compound nouns are the most frequent correspondences of English proper noun modifiers in both translation directions. Translations from German and Swedish into English produce equally many proper noun modifiers (c. 5/10,000 words). The highly significant difference between Swedish originals and translations (coupled with the non-significant difference in the English–German data in figure 8) is therefore caused by Swedish translators often choosing to translate English proper noun modifiers into genitives and prepositional phrases. Swedish more strongly than German disprefers ad hoc compounds (as noted in section 4.3), compounds with acronyms and heavy head compounds (see next section).

Even though compounds account for a larger proportion of the instances in the German and Swedish originals, they are rarer in the originals than in translations as counted per 10,000 words.Footnote 22 This is partly explained by English proper noun modifiers being less likely as translations of culture-specific elements, as when the Swedish compound Expressenjournalisten Jan Lindström is translated into an English prepositional phrase, Jan Lindström, a journalist on Expressen newspaper, in spite of similar constructions often being written as premodifiers in English originals (the Time reporter).Footnote 23

German and Swedish prepositional phrases and genitives are rarely translated into English proper noun modifiers and are instead usually translated word-for-word. Also, a proper noun construction would be more condensed and thus less transparent, making it a less likely choice. In addition, prepositional phrases and genitives are not subject to the ‘typification effect’ associated with many English proper noun modifiers (see, e.g., Schlücker Reference Schlücker2013: 468). Examples (29)–(33) illustrate why there are fewer English proper noun modifiers in translations than in originals. In (29) and (30) the modifiers are translated into Swedish prepositional phrases and a German adjective and genitive. The German and Swedish original prepositional phrases in (31) and (32), however, are rendered word-for-word, although these could have been transposed into English proper noun modifiers. More compressed and less transparent translations of prepositional phrases, as in (33), are quite rare.

(29) the same Washington think tanks (LEGS; English original)

denselben Washingtoner [adj] Denkfabriken (German translation)

tankesmedjor i [‘in’] Washington (Swedish translation)

(30) an Associated Press article (LEGS; English original)

in einem Artikel der [gen] Associated Press (German translation)

en artikel av [‘by’] Associated Press (Swedish translation)

(31) des großen außenpolitischen Think Tanks aus [‘from’] Berlin (LEGS; German original)

the main foreign-policy think tank in Berlin (English translation)

(32) en uppmärksammad artikel i Dagens Nyheter (LEGS; Swedish original) [‘a much-noted article in Dagens Nyheter’]

a much-cited article in Dagens Nyheter (English translation)

(33) ett hotell i [‘in’] Florida (LEGS; Swedish original)

a Florida hotel (English translation)

German and Swedish genitives are also rarely translated into more compressed premodifiers. The most noticeable factor for genitives is illustrated in (34): about half the instances involve acronyms.Footnote 24

(34) Die letzte Regierung der [gen] DDR (LEGS; German original)

The last GDR government (English translation)

This section has shown that the translation direction is an important factor affecting the likelihood of which type of correspondence occurs with which type of English proper noun modifier. This is also seen in the final feature investigated in this article, heavy heads.

4.7 Proper nouns modifying heavy heads

As noted in section 2, heavy heads such as ???Mozart-violinsonat are disfavoured in Swedish (Koptjevskaja-Tamm Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Börjars, Denison and Scott2013). In our English originals, 15.1 per cent (88/583) of the noun phrases involve heavy heads, such as the Luftwaffe staff officer and the US tobacco industry. Of these 88, 29 (33 per cent) of the German and 10 (11 per cent) of the Swedish instances are translated into compounds in which the English proper noun is a constituent. This is significantly lower than in the material as a whole,Footnote 25 which shows that greater noun phrase complexity makes translators choose other alternatives than compounds. Two instances of English heavy head noun phrases rendered as German three-part compounds are given below. The Swedish translators instead choose a prepositional phrase, as in (35), and a genitive, as in (36). These German compounds are unproblematic, but the Swedish equivalent compounds are different: *USA-nyhetsprogram is unidiomatic and not found on Google,Footnote 26 while, interestingly, both Mac-operativsystem and Macintosh-operativsystem occur. It is likely that these forms are due to English influence on Swedish (cf. Zifonun's (Reference Zifonun, Scherer and Holler2010) suggestion that proper noun compounds are increasing in German due to English influence).

(35) a U.S. news show (LEGS; English original)

einer US-Nachrichtensendung (German translation) [‘a US-news-programme‘]

ett nyhetsprogram i USA (Swedish translation) [‘a news programme in the USA’]

(36) the Macintosh operating system (LEGS; English original)

des Macintosh-Betriebssystems (German translation) [‘the-gen Macintosh-operating-system’]

Macens operativsystem (Swedish translation) [‘the Mac's operating-system’]

It is noteworthy that of the instances translated into compounds, only 21 German and one (marginal) Swedish instance contain heavy heads. The remaining instances are ‘simplifications’ where sequences of three English nouns have been reduced to German and Swedish two-part compounds, as in (37).

(37) an HP company man (LEGS; English original)

ein HP-Mann (German translation)

en HP-anställd (Swedish translation) [‘an HP employee’]

As exemplified in (35) and (37), acronyms are frequently the first element in noun phrases with heavy heads – 31 per cent (27/88), which is significantly higher than for the instances with simple heads.Footnote 27 The frequency of acronyms can partly explain the greater German preference for compounds, as discussed earlier (see Fleischer & Barz Reference Fleischer and Barz2012: 283).

Heavy heads are less common in translated English than in English originals: 12.2 per cent (33/270) in translations from German and 5.3 per cent (10/187) from Swedish. The frequency in translations from Swedish is significantly lower than in English originals and translations from German.Footnote 28 Two factors are at play here: on the one hand, a translation effect of English translators rarely producing condensed and less explicit N + N+N sequences, and on the other, heavy-head compounds being more frequent in German than in Swedish originals. English noun phrases with heavy heads mostly occur as translations of compounds (as in (38)) and genitives (as in (39)).

(38) Åhlénskoncernen (LEGS; Swedish original) [‘the Åhléns corporation’]

Åhlens department store (English translation)

(39) Parteizentrale der [gen] FDP (LEGS; German original)

FDP party headquarters (English translation)

A majority of the English heavy-head instances translated from German (61 per cent; 20/33) involve acronyms, as illustrated in (39).

5 Conclusions

Although many previous studies on English proper noun modifiers have taken contrastive aspects into account, the present study is the first systematic corpus-based investigation of its kind. Our study is based on three contrasting languages featured in some of the previous, more eclectic studies. The LEGS corpus thus allows us to shed new light on proper noun modifiers, from both a monolingual English perspective and an English–German–Swedish contrastive perspective.

Proper noun modifiers are more frequent in English originals than in translations into English. It is reasonable that a feature that is possibly English in origin and spreading to other languages (see Zifonun Reference Zifonun, Scherer and Holler2010: 168) would be more frequent in English originals. Similar tendencies for English-specific constructions being more common in English originals than in translations have been identified by, e.g., Levin & Ström Herold (Reference Levin, Ström Herold, Egan and Dirdal2017) and Ström Herold & Levin (Reference Ström Herold and Levin2018).

Previous studies have largely focused on modifiers based on personal names, but our data show that this type is much rarer than those based on organizations or places. The semantic types have a strong influence on the choice of correspondences with organization-based English proper noun modifiers typically being translated into compounds, and location-based ones into prepositional phrases in both German and Swedish. There is a natural connection between location-based modifiers and prepositional phrases in that the latter explicitate the position or origin of the head noun.

There is a fairly strong correlation between the German and Swedish translations of English proper noun modifiers. Compounds, genitives and prepositional phrases are the most frequent in both languages, but the proportions differ. Compounds are the most common correspondence in both languages and translation directions, which shows that the compound is the closest structural equivalent to English nouns premodified by nouns. Like the English proper noun modifiers, German and Swedish compounds are condensed structures allowing the labelling of various phenomena. The typifying effect may even be slightly weaker in German than in Swedish compounds, which would partly explain why compounds are rarer in Swedish than in German translations.

The greater German preference for compounds and the Swedish predilection for prepositional phrases reflect general language-specific preferences. Compounds are more common in German (Carlsson Reference Carlsson2004: 75) and postmodifiers in Swedish (Levin & Ström Herold Reference Levin, Ström Herold, Egan and Dirdal2017). One reason for the lower frequency of compounds in Swedish is, as found by Koptjevskaja-Tamm (Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Börjars, Denison and Scott2013), that Swedish disallows compounds with heavy heads.

Translation texts are generally characterized by explicitation rather than implicitation (see Baker Reference Baker, Baker, Francis and Tognini-Bonelli1993), but, at least in our data, the translation direction must be taken into account. Translations into Swedish contain more instances of explicitationFootnote 29 (54%) than German (38%),Footnote 30 while German uses structures as (in)explicit as those in the target languageFootnote 31 (55%) more often than Swedish (40%).Footnote 32 ImplicitationFootnote 33 is rare overall (7% in German; 6% in Swedish).Footnote 34 The main reason for the difference between the target languages is that German often makes use of compounds which are as (in)explicit as English proper noun constructions, whereas Swedish has a preference for more explicit genitives and prepositional phrases. When translating from German and Swedish into English proper noun modifiers, however, cases of implicitation clearly outnumber cases of explicitation. The reason for this is that proper noun modifiers are so condensed that they are unlikely to be more explicit than any other structure.Footnote 35 These findings indicate that the translation direction and the type of structure investigated are paramount when considering explicitation and implicitation.

The present study has illustrated that it is particularly fruitful to use contrastive data to investigate language structures that are increasing in use and spreading to other languages. However, in such studies it is important to distinguish between language-specific and translation-specific features. As indicated in previous studies, contrastive data shed new light on the meanings, uses and interpretations of English proper noun modifiers while also highlighting features associated with the particular translation process. The findings call for future studies of contrastive data from other languages and genres apart from popular non-fiction.