1 Introduction

That English is a contact language is widely acknowledged (e.g. Hundt & Schreier Reference Hundt and Schreier2013). Through its history in England and the larger British Isles, speakers of Celtic and Scandinavian languages as well as French shifted to English, and in the course of doing so contributed to language change (Fischer Reference Fischer2013). The effect on English vocabulary is widely recognised, but the grammatical effects have only been acknowledged in more recent reappraisals of the evidence (Hundt & Schreier Reference Hundt and Schreier2013: 3–4). Since the onset of the colonial diffusion of English, two specific kinds of contact-induced change have attracted attention: koineisation or convergence in contact between transplantedFootnote 1 dialects of English, for instance in New Zealand (Trudgill Reference Trudgill2004), and transfer of first-language (L1) features to English as a second language (L2). The latter scenario includes English as used in the Outer Circle (Kachru Reference Kachru1985), or language-shift Englishes such as Irish English (Hickey Reference Hickey2013) and Indian South African English (Mesthrie Reference Mesthrie1992).

Notably absent from most discussions is the possibility of language change in modern and contemporary L1-varieties of English through contact with other languages in the same multilingual environment. In this article, we investigate a situation of sustained contact between two languages in a multilingual setting, to analyse how a less dominant language, Afrikaans, may have affected English over the course of two centuries in the South African context. Our focus is on the native variety of English (termed White South African English, or WSAfE), transplanted to South Africa with the arrival of the British settlers in 1820.

The particular nature of settings of language contact is important. Thomason & Kaufman (Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988: 35) postulate as point of departure that the sociolinguistic history of speakers, rather than the structure of the languages, is the primary determinant of the outcome of language contact. Matras (Reference Matras2009: 47) points out that ‘[a]symmetry in the social roles of languages and in the directionality of bilingualism is a crucial factor in determining the impact that contact is likely to have on the structures of the relevant languages’. Generally, the assumption is that languages of high status, used across a wide range of domains by mainly monolingual speakers, are less likely to be affected by crosslinguistic influence (CLI) in contact settings than languages of lower status used by highly bilingual speakers in intensive contact with high-status languages (Thomason Reference Thomason2001: 66; Matras Reference Matras2009: 47; Fischer Reference Fischer2013: 19–20). Under these conditions, it seems unlikely that Afrikaans would have considerable influence on WSAfE, given that speakers of WSAfE are not on average more bilingual than Afrikaans speakers, and English has enjoyed a higher status than Afrikaans for most of their shared history (Van Rooy Reference Van Rooy2017: 513–15).

The extent to which Afrikaans has influenced the grammatical features of English has, indeed, been a matter of debate. Lass & Wright (Reference Lass and Wright1986) argue that the case for Afrikaans influence is overstated for a number of features where they identify endogenous sources. Mesthrie (Reference Mesthrie2017: 535-9) reviews previous work and concludes that a selection of informal features of Afrikaans (associative plurals, reduplication, diminutives and the invariant tag nè) made their way to English, but that not all cases of parallelism between the two languages have necessarily been shown to be contact-induced. Wasserman & Van Rooy (Reference Wasserman and van Rooy2014) argue that semantic and pragmatic uses of modal constructions have been transferred to WSAfE from Afrikaans, alongside increased frequency of use of some modals.

Studies of language change, including changes that are influenced by language contact, are underpinned by the assumption that face-to-face interaction is a required mediating factor for language change to spread (Sayers Reference Sayers2014). Written sources are typically analysed for the evidence they yield about the spoken language of earlier times (e.g. Mesthrie Reference Mesthrie1996). While we do not deny the importance of spoken interaction, in this article we argue that it is crucial also to consider written communication as a possible site of language change (see also Biber & Gray Reference Biber and Gray2011). In the usage-based paradigm (especially Bybee Reference Bybee2010) which we adopt in this article, written input, just like spoken input, serves to cognitively entrench grammatical constructions – which, in turn, raises the accessibility of constructions for users, who will then be more inclined to use these constructions in both spoken and written settings, where appropriate, setting in motion a frequency-entrenchment cycle that cuts across written and spoken language. In highly literate communities, exposure to written texts (particularly of widely disseminated genres like newspapers and magazines, or, more recently, online communication) forms an important component of the language input that users receive alongside spoken interaction, as argued by Kruger & Van Rooy (Reference Kruger and van Rooy2017).

In other words, in contexts where contact may introduce grammatical changes (in whichever dimension), such changes may be taken up and disseminated in written as much as in spoken language, setting in motion the dynamics of change. A further dimension to the process of dissemination of changes in writing, as Kruger & Van Rooy (Reference Kruger and van Rooy2016) argue, can be identified in the case of edited published writing, where favourable conditions for language contact may exist within the publishing landscape of a society. This, certainly, has been the case in South Africa, where the local English and Afrikaans publishing industries have developed alongside each other for approximately two centuries – often from within the same publishing houses (Kantey Reference Kantey1990), which opens up the opportunity for shared text-production norms to emerge. However, there is scant historical research on publishing and editorial practices in South African news, magazine and book publishing.

The dynamics of contact in the written medium of course also need to be considered from the broader perspective of the changing language ecology of South Africa over the course of the two centuries in which English and Dutch/Afrikaans have co-existed. A complete survey of the historical development of English and Afrikaans in South Africa is not possible within the scope of this article (see Van Rooy Reference Van Rooy2017: 509–11 for the most recent survey). For the purposes of the argument here, it will suffice to point out that clear shifts in the nature of the contact can be identified, accompanied by shifts in power relationships and attitudes of animosity and reconciliation.

A Dutch colony at the Cape was established in 1652, and under the influence of various factors, the settlers’ Dutch gradually diverged from metropolitan or continental Dutch. By the early nineteenth century, a local Cape Dutch vernacular was recognised as distinct from metropolitan Dutch. Afrikaans gained recognition as a language separate from Dutch in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The British captured the Cape Colony in 1795, and in 1814 the Cape became a British territory. As a result, the Cape Dutch settlers had to yield to the British in all domains of public life. In 1820 the first sizeable group of British settlers arrived at the Cape, and in 1822 English was declared the only official language of the Cape, accompanied by aggressive Anglicisation policies (Van Rooy Reference Van Rooy2017: 509–10). In 1910, the Union of South Africa was formed out of the various separately governed territories under British rule, adopting a bilingual policy with Dutch and English as official languages, with the former replaced by Afrikaans in 1925. Afrikaans and English remained the official languages of South Africa (through the establishment of the Republic of South Africa in 1961) until 1994, when eleven languages (including Afrikaans, English and nine African languages) were recognised as official languages.

The linguistic features we investigate in this contact setting are three syntactic constructions associated with the representation of direct and indirect speech and thought: the order of the reporting and reported clause in direct speech reporting; inversion of subject and verb in reporting clauses that are not in sentence-initial position; and the omission of the complementiser that in indirect speech and thought representation. These are more formal syntactic features, and perform linguistic functions that are more commonly expressed in writing than in speech, which have particular partially similar and partially distinct forms as well as pragmatic associations and functions in Afrikaans and non-contact varieties of English. In a previous study of these features, Kruger & Van Rooy (Reference Kruger and van Rooy2016) found that, synchronically, WSAfE and BrE differ from each other in respect of their preferences for variants of these constructions. In this article, we investigate these constructions in comparable diachronic corpora of WSAfE and BrE, with reference also to a diachronic corpus of Afrikaans, to determine whether CLI (of different kinds) from Afrikaans may account for divergences between WSAfE and its British parent variety. Before turning to these constructions, we first briefly outline our view of how contact potentially influences language change. Subsequent to this, we briefly discuss the diachronic corpora used in the study, and the quantitative analysis methods. This is followed by the presentation and discussion of findings, and a summary and concluding perspective on the results of the study.

2 Crosslinguistic influence

If a linguistic change occurs under the influence of a grammatical construction from another language, then the change is called contact-induced (Thomason & Kaufman Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988; Thomason Reference Thomason2001). This process of change has been referred to in various terms, including borrowing, interference, code-copying, and replication (see Weinreich Reference Weinreich1979; Thomason & Kaufman Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988; Thomason Reference Thomason2001; Johanson Reference Johanson2002; Heine & Kuteva Reference Heine and Kuteva2005), but in this article, we refer to the general process as CLI.Footnote 2 Our approach to CLI is functional in that it extends to change in use and not only change in form, and aligned with the usage-based view of grammar developed by Bybee (Reference Bybee2010), in terms of which a change in the frequency of a construction or of its context of use is an important part of language change.

Thomason & Kaufman (Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988: 36-9) propose a sharp distinction between borrowing, which typically involves specific lexical elements, and interference, which typically affects grammatical patterns. The latter is characterised by imperfect acquisition of a second language, a factor that is absent from the first manifestation of contact-induced change.Footnote 3 They highlight the importance of social factors such as the intensity of contact and the asymmetry in the relation between the speakers in the contact setting. They also show that borrowing affects lexical items first, and only after much more intense contact are phonological or morphosyntactic forms borrowed. Where a non-dominant population approximates the target language of a dominant speech community, phonological and syntactic patterns of their native language may be transferred in the first instance, to the degree that they do not converge on the target language as spoken by the dominant population.

Matras (Reference Matras2009) distinguishes between the replication of linguistic matter and linguistic patterns, where the former is identifiable as discrete morphs, and the latter are more abstract structures for the organisation of linguistic matter, or grammatical constructions (Matras Reference Matras2009: 234). Heine & Kuteva (Reference Heine and Kuteva2005) hold a similar view. Their point of departure is that the early stages of grammatical change through contact take place through the replication of use patterns drawn from the other language known by the speakers. While it is possible for a new use pattern to be introduced to a language through contact, Heine & Kuteva (Reference Heine and Kuteva2005: 45–50) argue that one possibility that is sometimes overlooked is where CLI enables a ‘minor use pattern’ in the replica (or target) language to develop into a ‘major use pattern’ under the influence of contact with a model (or source) language where a similar pattern exists. In other words, there is an increase in the frequency of an existing use pattern (or construction) under the influence of the frequency pull of a pattern in another language in the contact situation that is perceived to be similar. Such a change is therefore a quantitative development only, and corresponds to what Mougeon et al. (Reference Mougeon, Nadasdi and Rehner2005: 102–3) refer to as covert transfer: contact causes an increase in the frequency of a construction in a target language that shows similarity with one in the source language. Exemplars of a construction from the source language are categorised with exemplars of a similar construction in the target language (based on similarities in form and function) – compounding the entrenchment of the construction and leading to an increase in frequency of use. These frequency changes may at later stages lead to an extension to new contexts and the development of new functions (Heine & Kuteva Reference Heine and Kuteva2005: 45).

Overt transfer, in contrast, is a ‘qualitative development’ (Mougeon et al. Reference Mougeon, Nadasdi and Rehner2005: 102) in the target language, introducing a construction into the target language that did not exist prior to contact. Such a language change presupposes that the languages in question differ in some respect in the inventories of constructions available to users. A construction from the source language must occur with such frequency of use that it becomes so cognitively salient that it transfers across the two languages in the form of an innovative structural pattern or innovative functional use in the target language.

There are a number of reasons why a change emanating from CLI may disseminate further. In the case of second-language speakers who transfer features to a target language, the degree of bilingualism and intensity of contact act as constraining forces, while limitations of access to the target language and attitudes towards the target language from the side of the shifting population may facilitate greater divergence from the pre-existing form of the target language (Thomason & Kaufman Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988: 43-8). When the speech of the target-language speech community itself is considered, the default option is the borrowing of elements from the speakers of the other language in the contact situation, which are usually lexical features first, with grammatical features only following after very intense and prolonged periods of contact (Thomason & Kaufman Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988: 41–3).

The grammatical constructions under investigation in this article are, however, features of the dominant language that appear to be influenced by the less dominant language in the contact situation, which raises questions about the kinds of mechanisms that may promote CLI in this case. Thomason (Reference Thomason2001: 142) identifies the possibility of implicit ‘negotiation’ between speakers who aim to reproduce a pattern from another language. In more general terms, this may be framed as accommodation between speakers in a face-to-face contact situation, as proposed by Trudgill (Reference Trudgill2004) for dialect contact.

Alongside such social factors, two possible psycholinguistic factors may also play a role. The first of these is frequency of exposure, where even (extensive) passive exposure to a form may eventually lead to a speaker adopting it (Thomason Reference Thomason2001: 140). This ties in more generally with Bybee’s (Reference Bybee2010) view of the importance of frequency of exposure as part of the emergence of grammatical constructions beyond the context of language contact: the more a particular construction is encountered, the more it is reinforced in the mind of an individual user, which in turn leads to higher frequencies of use for that speaker. The likelihood of frequency entrenchment in contact situations is increased by the higher intensity of such contact.

Matras (Reference Matras2009: 151) identifies another psycholinguistic factor. He notes that the cognitive effort of keeping apart structures or preferences for use of constructions across two languages may be eased by simplifying the choices to be made. Bilingual individuals may opt to treat elements from different languages they perceive to be similar in the same way (e.g. use articles in the same way) even if monolingual speakers of the two languages use them in different ways. This could, in theory, extend to stylistic homogenisation of registers across two languages in contact, where similar constructions are selected in similar frequencies in the corresponding registers of two languages in contact as a way of simplifying different crosslinguistic register preferences.

In this article, we investigate the possibility that CLI effects from Afrikaans may account for some of the divergences of WSAfE from its parent variety, British English (BrE). We investigate three grammatical constructions associated with the representation of direct and indirect speech and thought in written texts, which demonstrate differential frequency distributions among variants in contemporary synchronic corpora of written BrE and WSAfE (Kruger & Van Rooy Reference Kruger and van Rooy2016). This analysis investigates the proposal made by Kruger & Van Rooy (Reference Kruger and van Rooy2016) that these frequency differences may be the result of prolonged contact with Afrikaans. It proceeds from the assumption that in considering contact explanations for change, it is necessary to consider the historical trajectories of change of all three language varieties in question: the model language (Afrikaans) and two variants of the target language: the one in contact with the model language (WSAfE) and one that is not (BrE).

3 Three reported-speech constructions in Afrikaans and non-contact varieties of English

Our selection of reported-speech constructions as an area of investigation is motivated not only by the synchronic differences observed by Kruger & Van Rooy (Reference Kruger and van Rooy2016), but also by the fact that speech and thought reporting is an area in which not only lexical but also structural aspects have been ‘fundamentally reorganized’ over the course of the past 150 years (D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015: 56), which creates an opportunity to observe whether CLI plays a role in a change that is ongoing in any case. A further motivation is the fact that speech and thought reporting have very specific functions across different written registers, and therefore offer opportunities to investigate the effects of language contact in different registers – which may, in themselves, be more or less receptive to change (Hundt & Mair Reference Hundt and Mair1999; Biber & Gray Reference Biber and Gray2013).

3.1 The position of the reporting clause in direct speech and thought reporting

In both English and Afrikaans, reporting clauses are syntagmatically variable. The reporting clause can occur before the reported clause, be inserted ‘within’ the reported clause, or occur after the reported clause, as illustrated in (1) to (3) (where the reporting clauses are underlined).

(1) She then said, ‘I am going to set the house on fire tonight, at seven o’clock.’ (WSAfE, Reportage, 19th-1)Footnote 4

(2) ‘Perhaps,’ I said, ‘she was anxious to be married, and he was her only suitor’ (BrE, Fiction, 20th-2)

(3) ‘The streets presented a very “sulphury” appearance,’ said our informant. (WSAfE, Reportage, 19th-2)

Although these positional variants are formally identical in English and Afrikaans, they demonstrate distinct register preferences in the two languages, particularly in reportage and fiction. According to Biber et al. (Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999: 923), the final position is preferred in British and American English news and fiction, but the initial choice is the preferred option in fiction. In Afrikaans, data from the Taalkommissiekorpus Footnote 5 reveal a consistent preference of slightly more than two-thirds for the final position in both reportage (68%) and fiction (70%).

Kruger & Van Rooy (Reference Kruger and van Rooy2016) found that the same pattern reported by Biber et al. (Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999) also holds for ICE-GB, but that ICE-SA, representing WSAfE, is different. That difference makes WSAfE very similar to Afrikaans: the final position for the reporting clause is the dominant pattern in reportage and fiction.

3.2 Quotative inversion in reporting clauses in non-initial position in direct and indirect speech and thought

Quotative inversion is one of the few vestiges of historical verb-second (V2) word order in English syntax (D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015: 47). In English, quotative inversion occurs freely in medial or final reporting clauses containing a noun phrase subject and a simple verb (Biber et al. Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999: 921), in both direct and indirect speech and thought. In the inverted form, the reporting clause has VS order, as in (4a) and (5a), with the corresponding non-inverted form with SV order in (4b) and (5b).

(4) (a)‘We feel a bit hard done by to have lost,’ said Clark. (BrE, Reportage, 20th-2)

(b) ‘I’ve wanted you for a long time,’ counsel added. (BrE, Reportage, 20th-2)

(5) (a) But these new mystery signals, said Mr. Garratt, seemed to be coming from nowhere… (WSAfE, Reportage, 20th-2)

(b) High real interest rates, Manuel said, were harmful to economic growth and job creation… (WSAfE, Reportage, 20th-2)

D’Arcy (Reference D’Arcy2015: 47) points out that these kinds of reporting structures are strongly associated with written rather than spoken language, and that inversion, in particular, ‘is maintained in more formal, reflective usage’.

Biber et al. (Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999: 922) note that where the subject is an unstressed pronoun, the non-inverted order is ‘virtually the rule’, except where used for stylistic effects. The questionable current acceptability of inversion with a pronoun-subject reporting clause is illustrated in (6b) (which was, however, acceptable in the nineteenth century).

(6) (a) ‘We are not seeing any reduction in the amount of downgrading activity,’ he said. (BrE, Reportage, 20th-2)

(b) ?‘Stay a minute’, said he, as she was on the point of departure. (BrE, Fiction, 19th-2)

In non-initial reporting clauses in Afrikaans, however, no alternation is possible, and the order is obligatorily inverted VS, as in (7a). The SV construction in (7b) is therefore ungrammatical.

(7) (a) ‘Ek is seker die vrou is nie van hier nie,’ sê Ana-Linda. (TK)

‘“I am sure the woman is not from here,” says Ana-Linda.’

(b) *‘Ek is seker die vrou is nie van hier nie,’ Ana-Linda sê.

‘“I am sure the woman is not from here,” Ana-Linda says.’

Kruger & Van Rooy (Reference Kruger and van Rooy2016) identify these formal asymmetries as presenting opportunities for both overt and covert transfer in contemporary usage. Overt CLI would occur if the less acceptable or archaic verb-pronoun structure occurred more frequently in contemporary WSAfE than in BrE, under influence of the obligatory inverted order in Afrikaans. Covert CLI would be evident in the higher frequency of the inverted VS order with noun subjects, and corresponding lower frequency of SV order in WSAfE. They find no evidence of overt CLI, but do find a stronger preference for the VS order in WSAfE compared to BrE with non-pronoun subjects. Given D’Arcy’s (Reference D’Arcy2012, Reference D’Arcy2015) comments on changes in the system of English speech and thought reporting, this raises questions about the extent to which, during an ongoing language change in English, there is evidence of a CLI effect from Afrikaans that slows down the change in WSAfE.

3.3 The presence or absence of the complementiser that in indirect speech and thought

In English and Afrikaans indirect speech and thought reporting, the complementiser introducing the complement clause (that or dat) is optional. This represents a recent language change in Afrikaans, since its Early Modern Dutch ancestor and Contemporary Dutch sibling do not allow complementiser omission freely (Van Bogaert & Colleman Reference Van Bogaert and Colleman2013: 496). Contact with English is identified as an important factor in the dissemination of this construction in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Afrikaans (Feinauer Reference Feinauer1990: 119). There is a syntactic difference in that Afrikaans has verb-final subordinate clause word order, so that when the complementiser is present, all verbs in the complement clause are clustered together in the final position. Where the complementiser is omitted, the complement clause has main-clause (V2) word order. This alternation is illustrated in (8). In contrast, English has no word-order alternation to mark dependency, and word order is the same for cases where the complementiser is absent or present (see (9)).

(8) (a) Hy het erkendat hy alkohol gedrink het. (TK)

He have.aux admit.pst.ptcp comp he alcohol pst.ptcp-drink have.aux

‘He admittedthat he had drunk alcohol.’

(b) Hy het erkenø hy het alkohol gedrink.

He have.aux admit.pst.ptcp ø he have.aux alcohol pst.ptcp-drink

‘He admittedø he had drunk alcohol.’

(9) (a) … and it is saidthat motions will be made to rescind these appointments. (BrE, Reportage, 19th-1)

(b) … and it is saidø motions will be made to rescind these appointments.

Afrikaans and English both demonstrate a high frequency of complementiser omission, with Afrikaans demonstrating a particularly strong preference for the form without the complementiser even in written registers. Van Rooy & Kruger (Reference Van Rooy and Kruger2016) find an omission ratio of 67 per cent in contemporary written Afrikaans, based on an analysis of the Taalkomissiekorpus.

In British and American English, the form without the complementiser is the dominant option in speech, but in writing, the form with the complementiser is overall more frequent (Biber et al. Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999). In respect of preferences in specific registers, Biber et al. (Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999: 680) find that in news reportage the form with the complementiser is strongly preferred, but in fiction, the form without the complementiser is slightly more frequent than the form with the complementiser. In Afrikaans, the form without the complementiser is the dominant choice in both fiction and reportage. Based on this difference, Kruger & Van Rooy (Reference Kruger and van Rooy2016) predict a higher omission rate in WSAfE reportage in comparison to BrE as a consequence of covert CLI at the pragmatic (register) level, possibly supported by convergence in publishing norms. They do not find support for this specific effect, but they do find that WSAfE, across all registers except the instructional register, tends towards a higher omission rate than BrE. They propose that given the particularly high omission rate in Afrikaans across written registers, the higher rate of omission in WSAfE may be the consequence of contact with Afrikaans more generally (Kruger & Van Rooy Reference Kruger and van Rooy2016: 129), but this hypothesis needs to be evaluated against diachronic data.

4 Method

4.1 Corpora

The primary analysis for this study was carried out using two comparable diachronic corpora of BrE and WSAfE. For the WSAfE component, we used selected registers from the corpus compiled by Wasserman (Reference Wasserman2014), as well as the most recent version of the International Corpus of English for South Africa (ICE-SA). The registers selected were dependent on the availability of comparable registers in the diachronic BrE corpus, for which we used ARCHER-3.2 (A Representative Corpus of Historical English Registers, 2013) and the International Corpus of English for Britain (ICE-GB; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Wallis and Aarts2002). The registers included in the corpora are letters (social and business), reportage and fiction.

Speech-reporting constructions fulfil distinct functions in these registers. A full appraisal of these functions falls outside the scope of this article; for the purposes of the argument it will suffice to point out that while in letters and reportage a shared core function of reporting the words of others can be identified, the encoding of evaluative stance is also an important function in these registers (see Jullian Reference Jullian2011). In fiction, the function is quite different, as speech reporting forms part of the representation of the interaction of characters in a narrative world. The representation of speech and thought is widely researched in literary stylistics (see, for example, Jahn Reference Jahn1992; Short Reference Short2012).

An important distinction between these registers is that letters tend to be unedited, whereas reportage and fiction are subject to editorial processes, which may be affected by publishing conventions in particular contexts (in themselves subject to change). Moreover, it is well known that different written registers are more or less receptive to linguistic change (Hundt & Mair Reference Hundt and Mair1999; Biber & Gray Reference Biber and Gray2013), with reportage generally identified as a register that is particularly apt to take on innovative forms relatively quickly.

The period covered by the two corpora is roughly 1800–2000, divided into four fifty-year periods. The composition of the corpora used is reported in tables 1 and 2.

Table 1 Word counts for BrE corpus

Table 2 Word counts for WSAfE corpus

In the discussion, we also make reference to the Taalkommissiekorpus of contemporary written Afrikaans (see footnote 5), and a diachronic corpus of Afrikaans compiled by Kirsten (Reference Kirsten2016), where relevant, to compare diachronic changes in Afrikaans. This corpus contains 250,000 words of data for each of three decades: the 1910s, 1940s and 1970s.

4.2 Analysis

4.2.1 Data extraction

To identify cases of direct and indirect speech and thought reporting, we used the same verb list as in Kruger & Van Rooy (Reference Kruger and van Rooy2016) as search items. This list includes all the public and suasive verbs listed by Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 1180–3), as well as an additional selection of verbs identified as introducing speech and thought reporting, which correspond to the verbs used in the analysis of Afrikaans complementation patterns by Van Rooy & Kruger (Reference Van Rooy and Kruger2016): think, moan, mumble, mutter, whisper, yell, admonish, joke, snarl, warn, respond, wish and guess. Using the concordances of all these verb lemmas, we analysed the entire data set to identify and code the following grammatical variants:

1. Direct speech with the reporting clause in (a) initial, (b) medial and (c) final position.

2. In all instances of direct and indirect speech with the reporting clause in medial and final position, constructions with the following word orders in the reporting clause: (a) noun phrase + verb, (b) verb + noun phrase, (c) pronoun + verb, and (d) verb + pronoun.

3. Indirect speech with the reporting clause in initial position, with the complementiser (a) present or (b) absent.

A total of 13,951 English concordance lines were analysed, which yielded 4,870 relevant cases included in the analysis, with frequencies of all variants of the three constructions under investigation ranging between 357 and 771 per 100,000 words per period per variety. Since the focus in this study is on proportional changes, raw frequencies rather than normalised frequencies are reported in most cases. Data for Afrikaans are taken from ongoing work on Taalportaal, an online grammar of Afrikaans (www.taalportaal.org), as well as Van Rooy & Kruger (Reference Van Rooy and Kruger2016). The total sample of concordance lines on which the analysis of Afrikaans is based exceeds 60,000, but includes a wider range of written registers than the data for English.

4.2.2 Data analysis

For all three constructions, the analysis proceeds in two steps. The first step compares the diachronic changes in the relative (proportional) preferences of one option over the other(s) for each of the three constructions, across the two varieties, to identify whether there are overall patterns of divergence in the frequency with which certain options are selected. Only if such divergence is demonstrated, can we consider whether it reflects grammatical changes related to CLI through comparison with the Afrikaans data. Register differences are considered, where relevant to the construction in question. The Afrikaans data are not included in the statistical analysis, however, because of differences in the way they were extracted, and also because the Afrikaans historical data go back only to the beginning of the twentieth century and have a different register composition.Footnote 6

Following this, a statistical evaluation of the differences in development across the two varieties and three registers in question is carried out. For this purpose, we use conditional inference trees, a method for regression and classification using binary recursive partitioning (see Tagliamonte & Baayen Reference Tagliamonte and Baayen2012), as implemented in the R-package ‘partykit’ (Hothorn & Zeileis Reference Hothorn and Zeileis2016). Hothorn & Zeileis (Reference Hothorn and Zeileis2016: 7–8) explain that conditional inference trees

estimate a regression relationship by binary recursive partitioning in a conditional inference framework. Roughly, the algorithm works as follows: 1) Test the global null hypothesis of independence between any of the input variables and the response (which may be multivariate as well). Stop if this hypothesis cannot be rejected. Otherwise select the input variable with strongest association to the response. This association is measured by a p-value corresponding to a test for the partial null hypothesis of a single input variable and the response. 2) Implement a binary split on the selected input variable. 3) Recursively repeat steps 1) and 2).

Conditional inference trees offer several advantages for linguistic analysis. They are suited to conditions of data sparseness, deal well with high-order interactions and highly correlated predictors, do not assume normal distribution of data, and are robust to outliers (Levshina Reference Levshina2015: 292). Importantly, they straightforwardly visualise how multiple predictors (or independent variables) operate together in conditioning the selection of a linguistic choice (Tagliamonte & Baayen Reference Tagliamonte and Baayen2012: 135).

We use conditional inference tree modelling to determine the relative importance of the three factors (or independent variables) of Variety, Register and Period in conditioning the choice between the options for the three constructions (the dependent variable). Given Thomason’s (Reference Thomason2001) recommendation that multiple causation should be considered when dealing with contact-induced language change, we formulate the following principles for interpreting the conditional inference trees. Evidence that Period significantly conditions the choice between alternatives indicates that there is change over time. A statistically significant contribution of Variety to the inference tree structure, coupled with correspondence of WSAfE to the Afrikaans frequency distributions, is accepted as evidence for language contact.

One limitation of the current research design should be highlighted. Other factors, especially grammatical ones, are also likely to play a role in the choice between variants. These factors are not included in the current analysis, but in section 6 we reflect on the implications that the inclusion of such factors may have for the current findings, and outline some future research possibilities.

5 Findings and discussion

5.1 The position of the reporting clause in direct speech and thought reporting

Positional variation for the reporting clause is rare in letters. The non-initial position is attested only thirteen times across the two corpora and four periods, and therefore the analysis in this section includes only fiction and news reporting. The two registers are analysed separately, because the distributions in fiction in contemporary BrE and SAfE are similar, while the distributions in reportage are quite different.

5.1.1 Fiction

The assumption in the analysis that follows is that the initial position is the most conservative option that resembles the syntax of complementation most, while the alternative positions are regarded as parenthetical, but are interpretable in terms of their correspondence, or, in a loose sense of the word, derivational relationship, with the initial variant (see Huddleston Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1024–9). Houston (Reference Houston2013: 203) argues that the non-initial variants developed during the course of the eighteenth century in tandem with the development of the conventions of the novel, specifically its need for direct speech as a more dramatic way of presenting the words of characters. Figures 1 and 2 compare the proportional (relative) frequency of the three positional variants (initial, medial and final) across the four periods in BrE and WSAfE respectively, with raw frequencies also provided in data tables.

Figure 1 Proportional frequency of positional variants for the reporting clause across four periods: BrE fiction

Figure 2 Proportional frequency of positional variants for the reporting clause across four periods: WSAfE fiction

In BrE, the initial position is a marginal choice in fiction throughout the period under investigation, which means that it had already receded quite dramatically by the end of the eighteenth century as the novel became an established genre. The medial position shows very strong representation in the first half of the nineteenth century, but thereafter gradually declines. The final position vies with the medial position as the dominant pattern in the first half of the nineteenth century, after which it gradually increases to the major use pattern in this register in the second half of the twentieth century.

In comparison, the conservative initial position is very dominant in the first half of the nineteenth century in WSAfE fiction, with just one case of the final position. However, a note of caution should be sounded: in this period, there is, strictly speaking, no published fiction in WSAfE, and this register consists mostly of autobiography and journals, where the established conventions of fiction did not play such an important role. Nevertheless, the initial position remains a comparatively strongly preferred option across at least the first three periods compared to BrE, converging with BrE norms only in the second half of the twentieth century. The medial position is never as strongly represented in WSAfE fiction as it is in BrE fiction, although it also converges with the decline in BrE in the second half of the twentieth century. The increase in preference for the final position evident in BrE is also evident in WSAfE, but the rate of increase is much steeper, and by the late twentieth century, what was a decidedly minor use pattern has become strongly dominant.

5.1.2 Reportage

What emerges clearly from a comparison of relative frequency of the three positional variants of the reporting clause in reportage (figures 3 and 4) and fiction (figures 1 and 2) is that across both varieties the initial position is much more strongly preferred in reportage than in fiction, and compared to fiction, the medial variant is very marginal in reportage by the end of the twentieth century.

Figure 3 Proportional frequency of positional variants for the reporting clause across four periods: BrE reportage

Figure 4 Proportional frequency of positional variants for the reporting clause across four periods: WSAfE reportage

There is a gradual increase in the prevalence of the final position in reportage in both WSAfE and BrE, starting in the first half of the twentieth century in both varieties. However, in BrE this increase does not continue to the second half of the twentieth century, and the initial position remains the major use pattern in this register in this variety. By contrast, in WSAfE the change is quite extensive. As pointed out in section 3.1, in contemporary Afrikaans, the preference in news reportage is strongly in favour of the final position (in contrast with BrE, which prefers the initial position), and Kruger & Van Rooy (Reference Kruger and van Rooy2016) propose that the differences in preference in contemporary BrE and WSAfE may be the consequence of contact with Afrikaans. The diachronic data allow us to refine this analysis: the proportional frequency of the final position increases much more in WSAfE, making it very similar to contemporary Afrikaans, where the final position is the major use pattern in this register.

The conditional inference tree analysis (see figure 5) both supports this overall analysis and allows us to further refine it.Footnote 7

Figure 5 Conditional inference tree for the choice of positional variant (Fin=final, In=initial, Med=medial), with Register, Period and Variety as predictors

The highest-level predictor identified is Register, confirming that fiction and reportage demonstrate different preferences across time and variety. When we consider news reporting (the right main branch of node 1), it is clear that the divergence between BrE and WSAfE in positional preferences emerges only in the second half of the twentieth century (node 17): WSAfE strongly prefers the final position, and BrE retains a comparatively stronger preference for the more conservative initial position. Prior to this, the two varieties share the same diachronic developments (see nodes 13, 14), and Period is a higher-level predictor of the choice than Variety. An external factor, contact with Afrikaans in this case, is likely, given the quite dramatic divergence in the rate of change between WSAfE and BrE. The timeline is consistent with the development of joint publication houses for Afrikaans and English primarily in the second half of the twentieth century (see Kantey Reference Kantey1990).

In fiction, the subsequent split is for corpus. British English (see node 3) follows a relatively straightforward diachronic development, in which the final position gradually increases at the expense of the medial position, with the nineteenth and twentieth centuries distinct in this respect. WSAfE shows a more complex, but still coherent development, with a slower and more gradual change in the shift in preference from initial to final position, without going through a phase where the medial position is particularly important.

Written Afrikaans (see figure 6) shows a gradual increase in the choice of the initial variant, at the expense of the final variant for most of the twentieth century, but this trend is reversed sharply after the 1970s. Contemporary Afrikaans uses the initial variant slightly less than 30 per cent of the time, and the final variant around 60 per cent of the time. Despite the direction of change, though, the final variant has remained dominant throughout the twentieth century in written Afrikaans, and thus potentially exerted covert CLI on WSAfE to follow suit. A further similarity is that in Afrikaans and WSAfE, the register differentiation between fiction and reportage is quite small (see section 3.1 above), whereas BrE maintains a considerable differentiation between the two registers.

Figure 6 Proportional frequency of positional variants for the reporting clause: Afrikaans

5.2 Quotative inversion in reporting clauses in non-initial position in direct and indirect speech and thought

5.2.1 Non-initial reporting clauses with pronoun subjects

As discussed in section 3.2, quotative inversion is the only feature where the possibility of overt transfer exists, if the archaic V-Pronoun construction is retained in WSAfE under the influence of the obligatory V-Pronoun order of Afrikaans. The relative frequencies of the V-Pronoun versus Pronoun-V order over the four periods in the two varieties (for all three registers) are shown in figures 7 and 8.

Figure 7 Proportional frequency of inverted vs non-inverted order in reporting clauses with pronoun subjects across four periods: BrE

Figure 8 Proportional frequency of inverted vs non-inverted order in reporting clauses with pronoun subjects across four periods: WSAfE

There is a similar pattern across the two varieties of a feature receding in the nineteenth century, and all but gone by the twentieth century, although the change in WSAfE lagged behind in the second half of the nineteenth century, as illustrated in (10).

(10) ‘Hadn’t we better change the name, Bain,’ said I when he had gone, ‘and call this “Orthis Kloof?”’ (WSAfE, Fiction, 19th-2)

The conditional inference tree (see figure 9)Footnote 8 shows that the effect of Period is the highest-level predictor, distinguishing the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (node 1). The left branch of the tree (the nineteenth-century data) further shows that BrE and WSAfE underwent somewhat distinct developments in this time period. BrE was advanced in the change relative to WSAfE, whereas in WSAfE this pattern was distinguished by register. Contact with Afrikaans is unlikely to explain the delay in the disappearance of the V-pronoun inversion, since the contact would have been at its lowest in the second half of the nineteenth century, and publishing in Afrikaans (and even Dutch) was very limited in the nineteenth century.

Figure 9 Conditional inference tree for quotative inversion with pronoun subjects, with Register, Period and Variety as predictors

The register distinction in the nineteenth century in WSAfE (though with relatively small numbers) provides some support for the notion that some registers are more ‘conservative’ and others more receptive to ongoing change. Letters and reportage had already been closer to selecting only the non-inverted word order than fiction as far as pronoun subjects were concerned. As noted earlier, fiction established itself later in WSAfE, and register conventions might still have been in flux in this period.

5.2.2 Non-initial reporting clauses with noun subjects

Figures 10 and 11 summarise the relative frequency of quotative inversion in reporting clauses with noun subjects in BrE and WSAfE respectively.

Figure 10 Proportional frequency of inverted vs non-inverted order in reporting clauses with noun subjects across four periods: BrE

Figure 11 Proportional frequency of inverted vs non-inverted order in reporting clauses with noun subjects across four periods: WSAfE

In the case of this feature, there is a clear shared historical diffusion of minor to major use pattern across the two varieties. The language change is in the opposite direction to the pattern that would be influenced by the obligatory Afrikaans word order. The non-inverted N+V construction is all but absent in the earlier nineteenth century (a definite minor use pattern), but is adopted at reasonably similar rates by both BrE and SAfE. By the second half of the twentieth century, the N+V pattern has developed to a major use pattern in BrE – but not quite in WSAfE, where the inverted V+N pattern is still more strongly represented. The stronger representation of the V+N pattern can perhaps be attributed to covert, rather than overt, CLI from Afrikaans, in that for contemporary written English by Afrikaans speakers, as reported by Kruger & Van Rooy (Reference Kruger and van Rooy2016: 127), the inverted form is favoured strongly in reportage, and thus may exert a pull in the opposite direction from the general change in English on WSAfE (no results were reported for fiction, since there is very little fiction produced originally in English by Afrikaans speakers).

The conditional inference tree (figure 12)Footnote 9 confirms that this feature is most strongly conditioned by Period, with a split on node 1 setting the second half of the twentieth century apart from the earlier periods, where the V-N construction dominates. However, WSAfE seems to be somewhat ahead of BrE in adopting the innovative N-V construction in the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. In the second half of the twentieth century, reportage and letters (on the one hand) and fiction (on the other) behave somewhat differently across the two varieties: reportage and letters, across the two varieties, have a relatively high frequency of the innovative N-V pattern. In fiction (the left branch of node 9), BrE and WSAfE behave differently: BrE is more advanced in the change towards the N-V pattern, whereas in WSAfE, the change lags somewhat behind, with a frequency similar to that in letters and reportage. The relative similarity of registers in WSAfE, compared to a larger degree of divergence across registers in BrE, again emerges as a finding from the diachronic data.

Figure 12 Conditional inference tree for quotative inversion with noun subjects, with Register, Period and Variety as predictors

5.3 The presence or absence of the complementiser that in indirect speech and thought

For this analysis, only complement clauses with the reporting clause in initial position were analysed, since for the medial and final positions the version without the complementiser seems to be required almost categorically.Footnote 10 Summarising across the registers, the proportion of complement clauses with the overt complementiser decreases in favour of the option with zero complementiser in both BrE and WSAfE. The same pattern is evident in Afrikaans (see figure 13).

Figure 13 Proportional frequency of dat present and absent: Afrikaans

However, the patterns in English are quite different across registers, and therefore each register is considered separately in the following discussion.

WSAfE fiction (figure 15) shows a very steep change in frequency, with an almost inverted preference for that/zero for the early nineteenth century compared to the late twentieth century. For BrE fiction (figure 14) the pattern is the same, but far more moderate – starting out with a preference for zero, and slowly increasing this preference.

Figure 14 Proportional frequency of that present and absent across four periods: BrE fiction

Figure 15 Proportional frequency of that present and absent across four periods: WSAfE fiction

For reportage, by the late twentieth century, very similar omission ratios are observed for the two varieties, with WSAfE slightly higher (as shown by figures 16 and 17), perhaps reflecting the development of a more general global shift to increased colloquialisation in reportage in native varieties of English. Prior to this, however, BrE demonstrated a strong preference for that, throughout the nineteenth and earlier twentieth century, whereas for WSAfE the increase has been more gradual in the direction of favouring the zero form – and with a stronger preference for zero from the beginning.

Figure 16 Proportional frequency of that present and absent across four periods: BrE reportage

Figure 17 Proportional frequency of that present and absent across four periods: WSAfE reportage

As far as letters are concerned, the data show that BrE participates in the overall change towards the zero complementiser (figure 18), but this is not the case for WSAfE, which continues to prefer the that form (figure 19). Considering the differences in register distribution, there is some evidence that in edited written registers, WSAfE and Afrikaans converge on similar omission preferences, whereas the unedited letters maintain a separate identity, further affirming our contention that the publishing environment is an important site of contact between English and Afrikaans. The evidence points to the likelihood of mutual reinforcement between Afrikaans and English; both varieties undergo the same change, but Afrikaans changes more extensively than WSAfE.

Figure 18 Proportional frequency of that present and absent across four periods: BrE letters

Figure 19 Proportional frequency of that present and absent across four periods: WSAfE letters

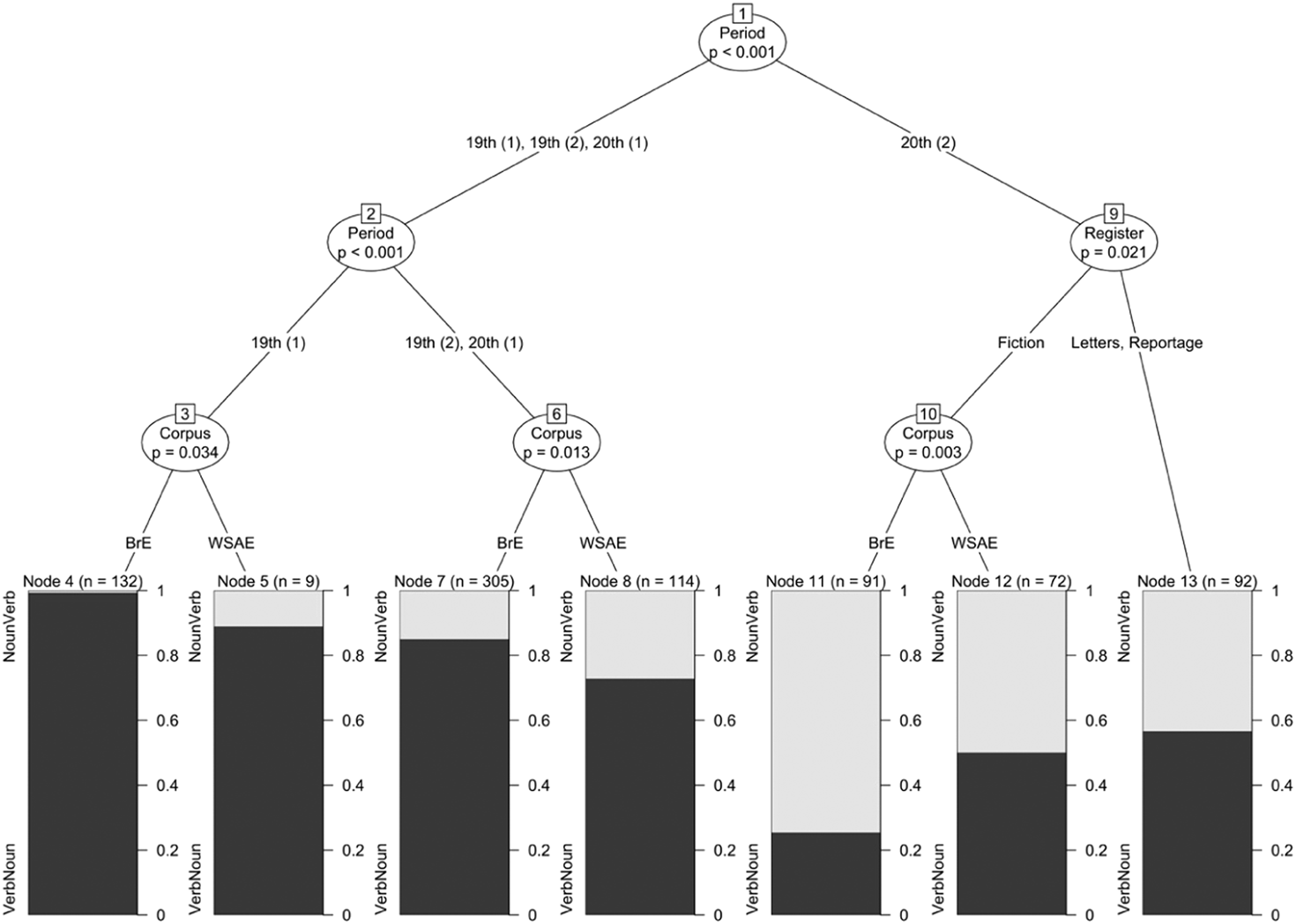

The conditional inference tree (figure 20)Footnote 11 demonstrates that the highest-level predictor of the choice between that/zero is register (node 1). For reportage (the right branch of node 1), there is a distinct diachronic development (node 15), which sets the latter half of the twentieth century apart from the preceding periods. In the earlier periods, BrE and WSAfE are significantly different (see node 16), with WSAfE demonstrating a stronger preference for zero, but both varieties converge on the zero variant by the latter half of the twentieth century.

Figure 20 Conditional inference tree for complementiser omission, with Register, Period and Variety as predictors

For fiction and letters, the following split is on period (node 2), isolating the first half of the nineteenth century (left branch of node 2). In this period, BrE and WSAfE also demonstrate distinct preferences, with WSAfE overall more conservative in selecting the form with that, but more so in fiction than in letters (see node 5). In the subsequent periods, BrE and WSAfE are also significantly different (see node 8). BrE, for the whole duration of this period, demonstrates a strong preference for zero, whereas in WSAfE, there are further distinctions: in the latter part of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century (node 10), the preference is mostly for zero, whereas in the second part of the twentieth century, there is a register differentiation (node 11), with fiction demonstrating a far higher omission ratio than letters. In this case, it appears as if the role of CLI in the development of WSAfE is quite marginal, and it is more likely that Afrikaans has been influenced by English. Both varieties are also likely to be influenced by other, presumably grammatical, factors – a point taken up in the following section.

6 Summary and conclusion

A set of related language changes in WSAfE and BrE were investigated in this article to determine the degree to which contact with Afrikaans is required to explain the changes in WSAfE. In the case of the position of the reporting clause in direct reported speech and thought, there is a move from minor to major use pattern (in the increasing preference for the final position of the reporting clause) across both BrE and WSAfE. The pattern of change in relative frequency is more extensive in WSAfE reportage, which strongly prefers this position in comparison to BrE reportage. The same pattern of change is evident in Afrikaans, with a strong increase in preference for the final position after the 1970s, which suggests mutual reinforcement between English and Afrikaans in the South African publishing industry, leading to a similar frequency change in both languages, and at the same time, divergence between WSAfE and BrE. In this case, an existing change in progress from minor to major use pattern in English is amplified by contact with Afrikaans. Covert CLI, due to reinforcement of the frequencies with which the construction is encountered in texts in Afrikaans and/or the second-language English of Afrikaans speakers, is the main reason for the difference in the rate of change and the more advanced endpoint of the change in WSAfE. Afrikaans and WSAfE also turn out to have very similar frequencies in both reportage and fiction, which points to a simplification of the register differentiation within and between the two languages in the contact situation.

As far as quotative inversion is concerned, for pronoun subjects, inversion disappears in both varieties, and contact with Afrikaans in the form of overt CLI does not appear to play an important role. The ongoing change continues until its end in the categorical loss of a grammatical variant in both BrE and WSAfE.

For quotative inversion with noun subjects, there is a clear diffusion from minor to major use pattern in both varieties, with the inverted V+N form initially dominant and then gradually supplanted by the non-inverted N+V form. In BrE the latter develops as clear major use pattern by the 1990s, but the change in WSAfE is slower, and the inverted pattern with V+N is still strongly represented. Contact with Afrikaans (and its obligatory V+N pattern) therefore appears to slow the rate of change in WSAfE in the late twentieth century (when contact between the two languages increased), but the effect of Afrikaans is, given the current data, not strong enough to arrest the ongoing change in English.

For the third construction, the alternation between that/zero, a similar change from minor to major use pattern in the preference for zero is evident across the English varieties, as well as in Afrikaans. There appears to be mutual reinforcement in the rate of change between Afrikaans and WSAfE, and similar proportional frequencies emerge in fiction and reportage. Differences in published and unpublished registers are also suggestive of a convergence in publishing norms, with published registers demonstrating a higher omission rate, as is also the case for Afrikaans. The influential Afrikaans style guide by Müller (Reference Müller2003: 664), which is based on the in-house guide of the largest multilingual publishing house in the country, Media24, explicitly advocates the omission of the complementiser in certain contexts.

In sum, the analysis demonstrates that sustained contact can lead to linguistic change even with a less dominant language affecting the shape of a more dominant language. The data in this study show that such change happens at a covert rather than overt level: the frequencies with which variants are selected converge below the level of conscious awareness, which points to a cycle of reinforcement between the exposure to texts in WSAfE, Afrikaans English, and perhaps to a lesser degree, Afrikaans; and the production of such texts. In the case of the contact between Afrikaans and WSAfE, it is clear that the site of contact is in the publishing industry.

Besides the role of the cycle of frequency reinforcement, the data also show evidence of simplification of register differences of those registers that are in contact in the publication environment, which ties in with the second of the covert forces identified in section 2. It is likely that the processing strain that competing preferences can put on text producers is mitigated by choosing constructions in similar ways across registers and across the two languages.

As pointed out in section 4.2.2, a limitation of the current study is that it does not consider additional variables, particularly grammatical variables, that may condition the choice between variants of a construction. The classification accuracy of the statistical models for complementiser omission and the relative position of the reporting and reported clause are above chance, but not as high as the models for quotative inversion, pointing to other factors that also play an important role in conditioning the ongoing change. The role of grammatical variables in conditioning, for example, the presence or absence of the complementiser is well researched (see, for example, Torres-Cacoullos & Walker Reference Torres Cacoullos and Walker2009). Investigating the role of these grammatical factors over time is an important next step in this research. Moreover, as Szmrecsanyi (Reference Szmrecsanyi2016) argues, it is important to consider that the frequencies of linguistic features may be conditioned by changes to the textual environment – and thus may be a collateral effect of other changes in discourse patterns in different registers.