1 Background and aims

This article sheds new light on the usage constraints and semantic profile of be able to, by combining empirical evidence from the British National Corpus (BNC, Davies Reference Davies2004–) with theoretical insights on the semantics–pragmatics interface. First a detailed, quantitative overview will be given of the modal meanings communicated by be able to in a 1,000-token sample extracted from the BNC and the same dataset will be used to determine if be able to typically refers to actualised situations. The empirical analysis of actualisation will be embedded in a discussion about the status of actualisation: is it a semantic or a pragmatic feature of the modal expression?

The main challenge involved is that of differentiating the context(s) of use of be able to from that of can and could: what are the syntactic, semantic and/or pragmatic factors that trigger the use of be able to?

There are some syntactic environments in which be able to is required; accounting for these is unproblematic. For instance, in the sentences in (1) and (2), be able to is needed to make up for the lack of non-finite forms in the paradigm of the modal auxiliaries can and could:Footnote 1

(1) Will he be able to walk again? (*Will he can walk again?)

(2) He wanted to be able to speak French. (*He wanted to can speak French.)

The key issue, though, is to get a grip on its use and meaning when there is no formal or structural trigger, as in the sentences in (3) to (5):

(3) Despite the competition, four years later she was able to (?could) purchase a wooden cart with small wheels. (BNC, written)

(4) As nationalised suppliers, the electricity boards in the past were able to (could) limit their liability for negligence to a trivial sum. (BNC, written)

(5) I'm very glad to say that we are able to (can) recruit occupational therapists in this county. (BNC, spoken)

When it comes to semantic and/or pragmatic constraints, the first question to be answered concerns the range of meanings communicated by be able to: does be able to only express ‘ability’ or can it be used to communicate some, or even all of the possibility meanings usually associated with can and could? Traditionally, an onomasiological approach is adopted and the use of the three modal expressions is compared in the context of ‘ability’ only, which can be defined as ‘the physical, intellectual or perceptual capacity to do something’ (Depraetere & Langford Reference Depraetere and Langford2020: 279). Coates (Reference Coates1983: 124–5) adds ‘permission’ and ‘possibility’ (examples (6) and (7)) to the list of meanings of be able to. Facchinetti (Reference Facchinetti, Mair and Hundt2000) likewise observes that, in the genre of imaginative writing, be able to communicates meanings that can be qualified as ‘some kind of “circumstantial possibility”’ (p. 128; see example (8)) or ‘permissive meanings’ (p. 129); and Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 208) also list ‘objective permission’ as one of the meanings of be able to (example (9)).

(6) But it's a bit ridiculous that I should be able to work in another college and not allowed to work in my own. (permission) (Coates Reference Coates1983: 124)

(7) The editor thanks you for submitting the enclosed ms but regrets that he is unable to use it. (possibility) (Coates Reference Coates1983: 124)

(8) If only she were able to stay here for the reminder of the holiday; but perhaps with Mum and Dad away, even here might start to haunt her. (circumstantial possibility) (Facchinetti Reference Facchinetti, Mair and Hundt2000: 128)

(9) Undergraduates are able to borrow up to six books. (objective permission) (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 208)

Clearly, in these examples the capacity to do something does not lie within the subject referent (only) but it is specific circumstances that make it possible for the subject referent to do something. While observations have been made to the effect that ‘ability’ is not the only meaning communicated by be able to, it is not clear what the relative proportion of each of the modal meanings is, the general assumption being that be able to most typically communicates ‘ability’. The aim of this article is to arrive at a more explicit picture on the basis of empirical evidence. Starting from the taxonomy of possibility meanings argued for in Depraetere & Reed (Reference Depraetere and Reed2011), we analysed a large dataset from the BNC. The results are presented in section 4.

Our second research question concerns actualisation, which is often put forward as the principal characterising trait of be able to. This feature is in the foreground in empirical studies and reference grammars (see e.g. Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 232; Ziegeler Reference Ziegeler2001, Reference Ziegeler, Panther and Thornburg2003; Aijmer Reference Aijmer, Lindquist and Mair2004) and, since Bhatt (Reference Bhatt, Shahin, Blake and Kim1999), it has been treated under the heading of ‘actuality entailment’ (see Hacquard Reference Hacquard, Gutzmann, Matthewson, Meier, Rullmann and Zimmermannto appear and references cited therein) in formal semantics.Footnote 2 In the examples in (3) to (5), there is reference to a situation that materialised: ‘she’ actually purchased a wooden cart with small wheels (example (3)); the electricity boards actually managed to limit their liability for negligence (example (4)); ‘we’ are in the process of recruiting and have recruited occupational therapists (example (5)). When be able to is replaced by could in (3) and (4) or by can in (5), the meaning changes: there is reference to the theoretical possibility of actualisation.Footnote 3

The question of actualisation has been addressed in work by Bhatt (Reference Bhatt, Shahin, Blake and Kim1999), Piñón (Reference Piñón, Garding and Tsujimura2003, Reference Piñón2009), Hacquard (Reference Hacquard2006, Reference Hacquard2009, Reference Hacquard, Gutzmann, Matthewson, Meier, Rullmann and Zimmermannto appear), Borgonovo & Cummins (Reference Borgonovo, Cummins, Eguren and Fernández-Soriano2007), Mari & Martin (Reference Mari, Martin, Aloni, Dekker and Roelofsen2007), Portner (Reference Portner2009), Homer (Reference Homer, Washburn, McKinney-Bock, Varis, Sawyer and Tomaszewicz2011), Giannakidou & Staraki (Reference Giannakidou, Staraki, Mari, Beyssade and Prete2013), Mari (Reference Mari2017), Vallejo (Reference Vallejo2017) and Carrasco (Reference Carrasco2019). Their work differs in terms of the formalisms used, but the authors agree on the origins of actualisation, which they argue is expressed whenever a root modal is used in the perfective:

A number of researchers, in particular Bhatt (Reference Bhatt, Shahin, Blake and Kim1999) and Hacquard (Reference Hacquard2006, Reference Hacquard2009), have observed that in languages which distinguish the perfective and the imperfective aspects morphologically, whenever an ability or a circumstantial modal appears in the perfective in a positive matrix clause, it is possible to infer the truth of its complement in the actual world. (Homer Reference Homer, Washburn, McKinney-Bock, Varis, Sawyer and Tomaszewicz2011: 106)

In the papers cited, perfectivity is morphologically marked in the languages that are the main focus of attention (French, Greek, Hindi, Italian and Spanish). It is difficult to assess whether this hypothesis also applies to be able to as English does not have similar perfective markers. First, the perfective/imperfective dichotomy is often linked to the non-progressive/progressive distinction in English (Declerck Reference Declerck2007: 53; see also Comrie (Reference Comrie1976) for a discussion of (im)perfectivity and the (non-)progressive). As the progressive is usually not compatible with stative verbs (such as be), it follows that, on this approach, be able to should be perfective by definition. However, not all scholars agree that simple verb forms in English indicate perfective marking (cf. Brinton Reference Brinton1988: 16; Declerck Reference Declerck2006: 30, Reference Declerck2007: 53; Binnick Reference Binnick1991: 296, Reference Binnick, Aarts, McMahon and Hinrichs2021: 248). Simple past forms are most often considered to be perfective, but Declerck, for instance, argues that this is not necessarily the case in examples like [They decided to write a letter.] Jane dictated while Mary wrote, in which ‘the nonprogressive form wrote is assigned a progressive (i.e. imperfective) meaning’ (Declerck Reference Declerck2007: 53). Binnick (Reference Binnick, Aarts, McMahon and Hinrichs2021: 248) likewise argues that examples like The children played and John was hungry can be understood as referring to incomplete (i.e. imperfective) events. The claim that simple present tense forms are perfective is likewise controversial (cf. e.g. De Wit Reference De Wit2017: 63). What is important for the topic at hand is that in a recent paper, Hacquard (Reference Hacquard, Gutzmann, Matthewson, Meier, Rullmann and Zimmermannto appear) argues that perfective morphology ‘alone doesn't guarantee an actualization of the ability’. Additional factors need to be brought in to explain how actualisation and modality can co-occur in the same sentence. Therefore, the intricate question as to what constitutes (im)perfective marking in English will not be in the foreground in this article.

In our view, there is a pressing empirical issue that needs to be addressed first, before accounting for the mechanism at work: it needs to be established whether actualisation is a conventional feature of be able to or whether it is a pragmatic inference that hearers make in particular contexts. While Bhatt (Reference Bhatt, Shahin, Blake and Kim1999: 86) considers actualisation to be part of the semantics of be able to, Piñón (Reference Piñón2009: 5) argues that it results from an abductive inference, and Hacquard (Reference Hacquard2006: 45f.) develops a hybrid model in which actualisation is the result of both convention and inference. In each case, the discussions are mainly theory-driven and little empirical data is provided to support the claims made. Although formal theories provide useful analytical tools, it is doubtful whether they alone can be used to determine the cognitive status of phenomena such as actualisation. Here, the use of corpus data seems comparatively more fitting.Footnote 4 This is a further empirical gap which we aim to fill in this article. In order to determine the nature of actualisation, we checked the BNC sample mentioned above to ascertain the extent to which the tokens refer to actualised situations. The results of this analysis will be presented in section 5. It will be argued that actualisation is indeed a conventional feature of be able to and thus not solely the product of inferential processes.

Eventually, the theoretical implications of this empirical analysis will be discussed. The analysis of be able to indeed poses a number of theoretical challenges with regard to the semantics–pragmatics interface. In particular, the claim that be able to conventionally communicates actualisation seems to result in a contradiction in terms: how can non-factuality, a defining feature of modality (Narrog Reference Narrog2005; Collins Reference Collins2009: 11; Portner Reference Portner2009: 1; Declerck Reference Declerck, Patard and Brisard2011: 27), and actualisation of the possibility (factuality) both be encoded by the same expression? One of the principal aims of this article is to spell out exactly what is semantic/pragmatic about actualisation. It will be argued that actualisation is a generalised conversational implicature (GCI), and that a conventional pragmatic layer of meaning is crucially needed to account for our empirical findings as well as to accommodate previous theoretical observations in a convincing way.

In other words, the new light we shed on the meaning of be able to results from method triangulation, whereby extensive empirical evidence is interpreted in the light of specific theoretical insights. The main research questions can be summarised as follows:

1 What modal meanings are communicated by be able to?

2 Does be able to conventionally refer to an actualised situation?

3 How can the empirical observations be accounted for from the point of view of the semantics–pragmatics interface?

The article is organised as follows. In section 2, we introduce the conceptual tools needed to interpret the data and we defend an approach to the semantics–pragmatics interface against which the empirical findings will be assessed. Section 3 is methodological in nature and describes the corpus and the features that were annotated. The results of the annotation process are presented and discussed in sections 4 and 5. We first look in detail at the semantic range of be able to: it is shown that be able to shares meanings with can and could other than that of ‘ability’ (section 4). Then we analyse in detail the notion of actualisation (section 5). The empirical findings feed into a theoretical discussion on the semantics–pragmatics interface in section 6.

2 Conceptual distinctions

A number of conceptual tools will be required to address each of the research questions. This section introduces them in turn: the taxonomy of modal meanings used in the corpus analysis (section 2.1), our approach to what constitutes semantics and pragmatics (section 2.2), and the differences between types of implicatures (section 2.3).

2.1 Taxonomy of modal meaning

In order to pin down more precisely the semantic range of be able to, a clear taxonomy of modal meaning is needed. In this article, we adopt the taxonomy developed by Depraetere & Reed (Reference Depraetere and Reed2011), which we present in this section.

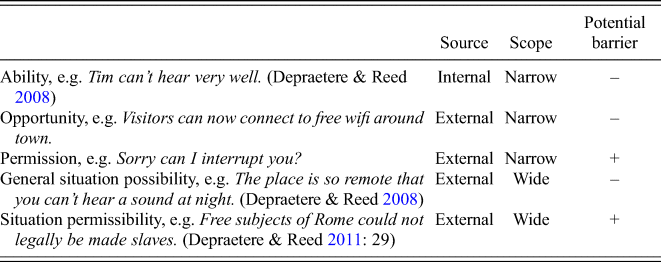

A first major distinction is that between epistemic and root (non-epistemic) meaning: epistemic modality indicates to what extent the speaker considers the proposition to be possible/necessary, while root modality crucially relates to the possibility or necessity of actualisation of a situation. We used Depraetere & Reed's (Reference Depraetere and Reed2011) taxonomy of root possibility meaning to classify the examples in our dataset. In their classification, five different root possibility meanings (‘ability’, ‘permission’, ‘opportunity’, ‘general situation possibility’ (GSP) and ‘situation permissibility’) are identified on the basis of three independent criteria: scope of the modality, source of the modality and potential barrier. Source of the modality refers to the person or circumstance in which the possibility originates. The source may be subject-internal (as in I can touch my nose with the tip of my tongue) or subject-external (e.g. You can apply for a passport online and avoid the queue). The scope of the modality may be wide, in which case it scopes over the entire proposition (e.g. Cracks can appear overnight, i.e. ‘cracks appearing overnight is a possibility’), or it may be narrow, in which case it scopes over the VP only (e.g. I can speak Russian). Finally, the third distinguishing feature in Depraetere & Reed's taxonomy is ‘potential barrier’, which is described as follows: in some root possibility meanings, the source of the possibility owes its status to the fact that it can preclude the subject referent from performing a particular action or prevent the actualisation of a situation (see Depraetere & Reed (Reference Depraetere and Reed2011: 13–16) for a detailed discussion of this feature). When the scope of the modality is narrow and when the feature of ‘potential barrier’ applies, the meaning is that of permission. For instance, in You can just call me Billy, the speaker constitutes the source of the modality because he can potentially prevent his interlocutor from calling him Billy. When the scope of the modality is wide, and when the feature of ‘potential barrier’ applies, permissibility meaning is communicated, as in We hope that all the Bangladeshi refugees can be repatriated in mid-August 2015 (www) (There is a potential barrier to the situation of the Bangladeshi refugees being repatriated in mid-August 2015). Further examples are given in table 1, which shows how the different meanings can be analysed in terms of the defining features (see the appendix in Depraetere & Reed (Reference Depraetere and Reed2011: 26–9) for an extensive list of examples).

Table 1. A taxonomy of non-epistemic possibility (based on Depraetere & Reed Reference Depraetere and Reed2011)

This taxonomy proves particularly useful in the context of the current corpus study since it provides very explicit criteria that are systematically applied. Another major advantage of this taxonomy is the level of detail of the semantic distinctions made. In most approaches, root possibility is usually divided into ‘ability’, ‘permission’ and ‘(other) root possibility’ meanings. This final category subsumes what is left of root modality when ability or permission are set aside, and labels such as ‘dynamic possibility’ (e.g. Huddleston & Pullum Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002), ‘neutral or circumstantial possibility’ (Palmer Reference Palmer1990) have been used (see Depraetere & Reed (Reference Depraetere and Reed2021: 217) for an overview of categorisations of root possibility). The defining criteria used by Depraetere & Reed enable them to identify and differentiate three further subcategories, namely ‘opportunity’, ‘general situation possibility’ and ‘situation permissibility’. In this way they tease apart the main strands of meaning that make up the region of root possibility meaning that is neither permission or ability.

2.2 Semantics and pragmatics

Another central aim of this article is to determine more precisely what is semantic/pragmatic about actualisation. To this end, it is necessary to define our view on what exactly constitutes semantics and pragmatics, terms which have become increasingly ambiguous and which cover different loads. In this article, we adopt the approach defended in Depraetere (Reference Depraetere2019) and Leclercq (Reference Leclercqto appear).

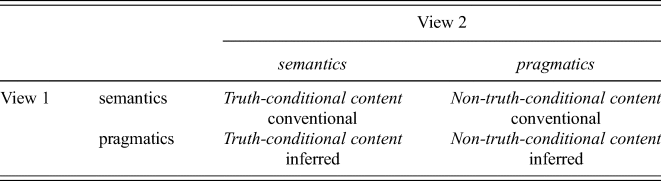

Among the different approaches to the semantics–pragmatics distinction, two views particularly stand out (see Huang Reference Huang2014: 299): one considers conventionality to be a defining criterion (view 1: conventional meaning whether truth-conditional or not is semantic, inferred meaning is pragmatic), the other builds on truth-conditions (view 2: truth-conditional meaning whether conventional or inferred constitutes semantics, non-truth-conditional meaning is pragmatic in nature). Following Leclercq (Reference Leclercqto appear), we assume that a more explanatory alternative can be obtained when these two approaches are combined (see table 2)

Table 2. Integrated view on the semantics–pragmatics interface (Leclercq Reference Leclercqto appear)

.

In other words, we systematically differentiate four (rather than two) types of content that can be communicated, and table 2 shows that each type of content results from the combination of the two views just presented (conventional truth-conditional meaning, conventional non-truth-conditional meaning, inferred truth-conditional meaning, inferred non-truth-conditional meaning). The question as to what we mean by the ‘semantics/pragmatics’ of actualisation will be addressed against the theoretical background just sketched. Our corpus analysis will show that actualisation is a conventional property of be able to (section 5). Accordingly the question will be to determine in what sense exactly actualisation counts as a convention: is it a pragmatic (i.e. non-truth-conditional) or a semantic (i.e. truth-conditional) convention? We will argue that actualisation is a pragmatic (i.e. non-truth-conditional) convention (see section 6).

2.3 Implicatures: particularised conversational, generalised conversational and conventional

Our empirical observations will lead us to argue that actualisation contributes to the pragmatic (i.e. non-truth-conditional) layer of the modal expression in the form of a generalised conversational implicature (see section 6). In this section, we offer a brief sketch of the different types of implicatures and their main features.

Implicatures are examples of pragmatic content par excellence. According to Grice (Reference Grice1989), who coined the term, there are three types of implicatures: particularised conversational implicatures, generalised conversational implicatures and conventional implicatures. The difference between them is primarily a question of conventionality and context dependence. Particularised conversational implicatures (PCI) (e.g. (10a)) are non-lexicalised (one-off) implicatures tied to a specific context of utterance (Grice Reference Grice1989: 37). One of the distinguishing features of particularised conversational implicatures is that they are directly cancellable (see Grice Reference Grice1989: 44), as in example (10b).

(10)

(a) Mike: Sarah, I made cookies, do you want some?

Sarah: I've eaten too much already.

Implicature: No, thanks.

(b) I've eaten too much already, but yes, I will have some.

Cancellability resides in the fact that the proposition implicated by the first clause (‘I don't want cookies’) in (10b) can be negated (‘but I will have some’) without resulting in a contradiction.

By contrast, a conventional implicature is not cancellable in any way (Huang Reference Huang2014: 76). As the name indicates, this type of implicature is conventionally associated with a particular linguistic item, and each use of this item systematically results in the recovery of the associated implicature. For instance, anyone using the sentence in (11) will be taken to endorse the implicated premise that French people are not kind (due to the use of but), and any attempt to cancel this implicature will result in a contradiction.

(11) Benoît is French but he is kind.

The category of generalised conversational implicatures (GCI) shares properties with the two previous types, in that GCIs are both conventional and context-dependent. Like conventional implicatures, they are conventional in the sense that they ‘are supposed to be the norm for specific types of expressions’ (Ariel Reference Ariel2010: 127). In (12), for instance, the use of a triggers the GCI that the referent of the NP ‘does not belong or is not otherwise closely related in a certain way to some person indicated by the context’ (Grice Reference Grice1989: 38). Like particularised conversational implicatures, however, GCIs are context sensitive in the sense that there may be contexts in which the implicature cannot be generated. GCIs ‘go through unless a special context is present’ (Horn Reference Horn2004: 5; original emphasis). This means that GCIs are less systematic than conventional implicatures, since they can be contextually banned. This is the case, for instance, in the example in (13): in (13a), it is possible that the speaker has been sitting in her own car and in (13b), the most likely interpretation is that the speaker broke her own arm and not that of another (which would require a specific context, e.g. the speaker has moved a statue and in the process of doing so the plaster arm has come off):

(12) I was sitting in a garden one day. A child looked over the fence. (Yule Reference Yule1996: 41)

Implicature: The speaker was not sitting in her own garden. The child is not her own.

(13)

(a) I have been sitting in a car all morning. (Grice Reference Grice1989: 38)

(b) I have broken an arm. (Grice Reference Grice1989: 38)

It is important to underline at this stage that the ‘contextual banning’ in the case of GCIs is not entirely similar to cancellability in the case of PCIs. Explicit cancellation in the case of (12) would imply that the speaker can say something like ‘? I was sitting in a garden one day, and/but it was my own garden’, the acceptability of which is at least questionable. What is at stake here is that, in particular contexts, GCIs do not arise (cf. examples in (13)).Footnote 5

3 Methodology

Having spelled out the research questions and defined the necessary conceptual distinctions, we will now describe the methodology used in the empirical part of the article. In order to examine the meaning potential of be able to, we compiled and analysed a dataset with 3,000 examples from the BNC (Davies Reference Davies2004–). The sample results from the random selection of 1,000 sentences of be able to, can and could (500 sentences in the spoken register and 500 sentences in the written register), the data with can and could having been added for comparative purposes in order to foreground the distinctive properties of be able to.

We first want to determine more precisely the semantic range of be able to and the meanings it typically communicates. In order to do so, we used the fine-grained taxonomy of possibility meanings put forward in Depraetere & Reed (Reference Depraetere and Reed2011) (see section 2.1). Accordingly, each example was assigned to one of the following classes: epistemic possibility, ability, opportunity, permission, general situation possibility (GSP), or situation permissibility.

We then zoomed in on actualisation. The main goal was to determine whether actualisation is a conventional property of be able to and whether it constitutes a distinguishing feature in the modal paradigm. Each example in the dataset was annotated in terms of four different criteria:

• Finiteness (This applies only to be able to: is the verb form finite (e.g. They were able to …) or non-finite (e.g. I might be able to …, just to be able to …, in terms of actually being able to …)?)

• Polarity (Does the modal expression feature in an affirmative or in a negative clause?)

• Sentence type (Is the sentence in which the modal occurs declarative or interrogative?)

• Actualisation (Is there reference to a specific instantiation of the residue?)Footnote 6

We coded the tokens in terms of finiteness, sentence type and polarity as we hypothesised that these features can potentially explain certain cases of (non-)actualisation.

For each of the research questions addressed, we carried out chi-square tests to identify significant patterns.

4 Meanings of be able to: results and discussion

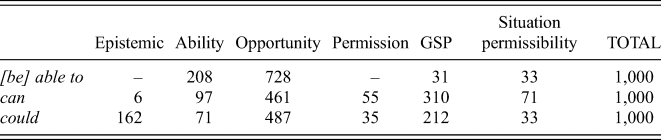

Table 3 gives an overview of the meanings communicated by be able to, can and could in our dataset.

Table 3. Meanings expressed by be able to, can and could in a sample from the BNC

Be able to is clearly polysemous: it does not express only ‘ability’, contra the general assumption, but shares several of the other meanings communicated by can and could. In our dataset be able to never communicates ‘epistemic possibility’ and ‘permission’, but it is used to communicate ‘opportunity’ (e.g. (14)), ‘general situation possibility’ (e.g. (15)) and ‘situation permissibility’ (e.g. (16)):

(14) As I climbed, so the cloud lifted and I was soon able to shed my waterproofs. (BNC, spoken)

(15) I presume you must be able to get an application form from somewhere. (BNC, spoken)

(16) The officers of the council are able to get on with the instructions of the committee without waiting for confirmation by the council of the decisions of the committee. (BNC, spoken)

These results adjust previous accounts because first of all, they bring to light the full semantic potential of be able to on the basis of a quantitative data analysis. The observation that be able to can communicate meanings other than ‘ability’ is not new (see section 1), but this survey is the first to provide solid empirical evidence that proves that its most frequent meaning is ‘opportunity’ rather than ‘ability’. Second, a chi-square test reveals that be able to expresses ‘opportunity’ significantly more often than any other meaning (see table 4).Footnote 7 The following are some further examples of be able to with an opportunity interpretation.

(17) By having four officers here it means that they will be able to man the police car for those shifts seven days a week. (BNC, spoken)

(18) One big advantage of self-sufficiency in food and clothing was that the demand on the public purse was much reduced. The state legislature was thereby able to be much more generous in capital grants for future building, and for improving the salaries of correctional officers. (BNC, written)

(19) ‘We are second from bottom and we need to get a result. I know a win for us will increase the pressure on them but that's football.’ From a personal point of view, I'd like their bad run to continue for another week. ‘Graeme Souness is the man to turn it around but he's not been able to pick a settled team because of injuries.’ (BNC, written)

Table 4. Opportunity vs other modal meanings expressed by can, could and be able to

p value < 0.00001

Thirdly, while it has been argued in previous work that be able to occasionally expresses ‘permission’, in the BNC sample, it is only used in examples in which the modality has wide scope and hence communicates ‘situation permissibility’ (see section 2.1).

Having identified the range of meanings communicated by be able to, we will now address the notion of actualisation.

5 Actualisation: results and discussion

Our second research question is concerned with actualisation: can actualisation be analysed as a conventional feature of be able to? For this part of the quantitative analysis, we excluded formal contexts which systematically coerce a non-actualised interpretation.Footnote 8 When be able to is non-finite (as in (20)), when it appears in an interrogative or in an imperative (as in the examples in (21)), or when it occurs in a negative context (as in the examples in (22)), the situation is presented as non-actualised (see e.g. Karttunen Reference Karttunen1971: 356; Palmer Reference Palmer, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1980: 92; Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 232):

(20) (a) He may be able to ask a favour or two from the West. (BNC, spoken)

(b) He doesn't seem to be able to concentrate. (BNC, spoken)

(c) But like all students, disabled students will benefit from being able to defer payments if their income falls below 11,500 pounds. (BNC, spoken)

(21) (a) Are you able to give us an estimate of the time that elapsed between breaking the door in and being called away by your team leader? (BNC, spoken)

(b) Be able to get yourself back into position. (BNC, spoken)

(22) (a) He hadn't been able to see Topaz for over two weeks because Virginia had been ill. (BNC, written)

(b) We were never able to get young miners. (BNC, spoken)

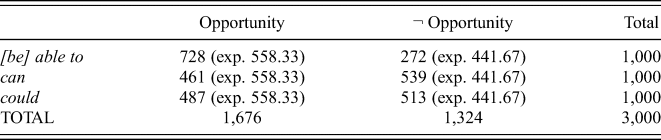

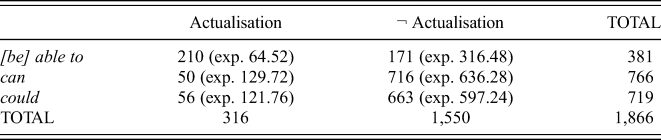

A total of 619 examples with be able to, 234 examples with can and 281 examples with could were in this way not taken into account. The coding results of the remaining examples in terms of actualisation/non-actualisation are summarised in table 5.

Table 5. Be able to, can, could and actualisation

p value < 0.00001

The chi-square test proves that be able to expresses actualisation significantly more often than expected, which justifies the hypothesis that actualisation is a conventional feature of this modal expression. The comparison with the other modals of the paradigm, can and could, provides additional evidence to this effect: actualisation is expressed significantly more often when be able to is used than when either can or could is used. As we see it, frequency of occurrence of a feature reflects the degree of conventionalisation, and as actualisation occurs significantly more often in sentences with be able to compared to those with can or could, we can conclude that it is (at least) a conventional feature of be able to. That is, from a usage-based approach (see Bybee Reference Bybee2010), these observed (and significant) differences must be represented in the speaker's mind, hence the view defended here that actualisation is a conventional property of be able to.

In section 4, it was shown that ‘opportunity’, rather than ‘ability’, is the most frequent meaning communicated by be able to. The question that is raised is whether the pattern is similar when there is actualisation (that is, whether there are significantly more cases of ‘actualised opportunity’ than cases of ‘actualised ability’). Here, we are interested to know exactly which of the different modal values of be able to is expressed when there is actualisation. Both Piñón and Hacquard assume that actualisation falls out from the ability reading of the verb. This is a theoretical claim that we want to test. Let us look again at the dataset from the BNC, as presented in table 6.

Table 6. Be able to, actualisation and modal meaning

Table 6 shows that reference to an actualised situation typically occurs in a context with ‘opportunity’ meaning. This observation has significant consequences. First, it goes against the standard assumption that be able to communicates actualised ‘ability’. While innate capacity or skill is an indispensable requirement for a situation to actualise, the external circumstances have to be such that the skill can be made use of. And it is external circumstances that are in the foreground when be able to expresses actualisation:

(23) The fall of Cromwell in 1540 improved Throckmorton's position, and he was able to see his family of eight sons and eleven daughters well established. (BNC, written)

(24) Chance plays a large part in shaping evolution. In Madagascar, lemurs evolved to fill all the niches that are occupied elsewhere by monkeys and apes. But they were able to do so only because – by chance – monkeys and apes failed to reach this island. (BNC, written)

(25) Thanks to generous support from the Mayfield Valley Arts Trust, we are able to offer students and young people tickets as indicated for just 3.00. (BNC, written)

Second, the results in table 6 also enable us to fine tune our analysis of be able to in another way. While actualisation and opportunity were independently identified as central features of this modal expression in the previous sections, table 6 suggests that they are tightly related and that it is in fact the combination of these two features (i.e. ‘actualised opportunity’) that constitutes a crucial distinguishing property of the modal verb.

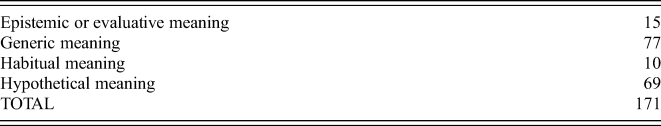

The remaining issue to be addressed relates to the 171 sentences in our sample (table 5) in which be able to does not convey actualisation. If actualisation is conventionally expressed by be able to, how can the exceptions to the general rule be explained? A more qualitative analysis of the relevant data shows that non-actualised be able to occurs in four contexts:

(a) Epistemic or evaluative meaning

In 15 tokens of the subset, be able to is embedded in a context in which epistemic or evaluative meaning is expressed. In the cases at hand, epistemic meaning is established by an adverb: example (26), for instance, can be paraphrased as ‘I might be able to write to her’; example (27) as ‘She must be able to throw it off’. It will be clear that epistemic meaning, which refers to the likelihood of actualisation, is incompatible with actualisation.

(26) Maybe now I'm able to write to her to reduce some of that isolation. (BNC, spoken)

(27) I mean she's obviously able to throw it off. I mean, she's in there Mick. (BNC, spoken)

(b) Generic meaning

In the examples below, there is reference to a generic situation, which implies by definition non-actualisation (see Bhatt (Reference Bhatt, Shahin, Blake and Kim1999) and Mari (Reference Mari2017) for similar observations):

(28) Few sufferers are able to stop and many of them end up with multiple amputations. (BNC, written)

(29) We do have erm some discussions seminars where between ten and fifteen students are able to discuss matters relating to the course. (BNC, spoken)

(30) The discount market is one in which (by debt sales) the monopolist is able to determine the position of the demand curve! (BNC, written)

(c) Habitual meaning

The following examples refer to a habitual situation, without reference to specific instantiated instances that make up the habit.

(31) It is important to be able to measure distances within several millimetres. (BNC, written)

(32) When he was able to be put in a wheelchair he was strapped upright and wore a collar. (BNC, written)

(33) If the Irish are to prosper Down Under, they will certainly have to improve their ball retention in contact situations, where Cabannes and Tordo were constantly able to rob ball on the deck. (BNC, written)

(d) Hypothetical meaning

In a final set of examples, there is reference to a hypothetical situation: the actualisation of the situation in the main clause depends on the potential actualisation of the situation in the subclause. The condition takes the form of an if-clause in (34); in (35) it is lexicalised by then; it is clear from the use of be able to in the purpose clause in (36).

(34) If you are able to prevent the things you have been doing, then you are already half-way to your goal. (BNC, written)

(35) Maybe you should take a map with you Cath, because then you're able to follow the, where you are. (BNC, spoken)

(36) I've not had the experience perhaps of teaching so many dyslexic children to be able to comment on this. (BNC, spoken)

Table 7 provides an overview of the distribution of these factors across the 171 instances in which be able to does not express actualisation.

Table 7. 171 ‘exceptions’ to actualisation with be able to: underlying principles

6 Be able to and actualisation: a GCI account

Now that we have established that be able to conventionally communicates actualisation, we need to decide if this automatically implies that this feature constitutes the semantics of be able to, in which case the paradox to be resolved is the following: how can one form communicate both non-factuality (modality) and factuality (actualisation)? Put differently, how can apparently intrinsically incompatible truth conditions be reconciled? It was shown in section 2.2 that not all meaning conventions are necessarily semantic (i.e. truth-conditional): alongside semantic conventions there are also pragmatic (i.e. non-truth-conditional) conventions. We will argue that there is no incompatibility between modality and actualisation when actualisation is analysed as a pragmatic convention. The hypothesis defended is that the pragmatic convention at stake here takes the form of a generalised conversational implicature (GCI).

Panther & Thornburg (Reference Panther, Thornburg, Panther and Radden1999) address this question but their stance is fundamentally different from ours. As we see it, the conflict occurs at the conventional level: the (modal) meaning of opportunity encoded by be able to is non-factual by definition, and actualisation is likewise a conventional property of the modal expression. This is not the case in Panther & Thornburg's account, in which the authors consider that both non-factuality and actualisation are not encoded by the modal expression but arise as implicatures. Non-factuality is a result of the exploitation of the maxim of quantity (‘make your information as informative as is required’): ‘if a speaker says that something is potential or possible then it is not actual’ (Panther & Thornburg Reference Panther, Thornburg, Panther and Radden1999: 352). Actualisation results from the exploitation of the potentiality for actuality metonymy and arises as ‘a (generalised) conversational implicature’ (Panther & Thornburg Reference Panther, Thornburg, Panther and Radden1999: 334). In other words, they argue that the tension between non-factuality and actualisation occurs at the inferential level and it is the Gricean maxims that explain which interpretation strategy makes it possible to avoid the conflict.Footnote 9 As we see it, Gricean maxims do not suffice to explain a paradox that rather concerns these two facets of the conventional meaning of be able to. This calls for a different line of argumentation. Furthermore, Panther & Thornburg do not explain in detail why the implicature might be a generalised conversational implicature (see quote above).

The idea that actualisation constitutes a GCI has also been alluded to by Westney (Reference Westney1995: 86), who points out that even though be able to communicates actualisation, it is cancellable in context (see also Horn (Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984) and Ziegeler (Reference Ziegeler2001) for a similar observation):

(37) I ran fast, and was able to catch the bus, but then I changed my mind and I walked instead.Footnote 10 (Westney Reference Westney1995: 86)

(38) She was able to solve the problem but (she didn't, as) she didn't have enough time. (Horn (Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984: 21) in Ziegeler (Reference Ziegeler2001: 279))

(39) She was able to speak, but chose not to. (Bert Cappelle, p.c.)

In these examples, the use of a but-clause seems to cancel the implication of actualisation conveyed by the main clause. There are a number of issues with this approach, however. First, this type of explicit cancellation is usually considered to be an uncontroversial distinguishing feature of PCIs rather than GCIs (see section 2.3), so we need to be cautious when using them uncritically as a distinguishing feature of GCIs. Furthermore, as we see it, there is a phenomenon other than cancellation of actualisation at stake in the examples in (37) to (39). These examples are special; there clearly is no actualisation of the ability. Our data analysis has shown that (a) be able to is polysemous (table 3) and (b) that actualisation systematically hinges on the modal meaning of ‘opportunity’ (table 6). In examples (37) to (39), the addition of the but-clause makes it clear that an ‘ability’ interpretation of be able to is intended. It therefore seems to us that these examples rather illustrate the general challenge which is that inherent in any interpretation process: because the words we use are ambiguous or polysemous, speakers need to guide the hearer to recover the intended interpretation.Footnote 11 Here, rather than explicitly cancelling actualisation, the speakers use the adversative clauses as a pragmatic strategy to disambiguate the sentence and thus enable the hearer to arrive at the ability reading of be able to. Those examples illustrate an explicit process of (speaker) disambiguation rather than the cancellation of an implicature, and can therefore not be used to determine the exact status of actualisation.

Bhatt's observations (Reference Bhatt, Shahin, Blake and Kim1999: 80) about cancellability are also relevant here: he argues that actualisation with be able to cannot, as a matter of fact, be explicitly cancelled, which shows that a semantic account is necessary (see Hacquard (Reference Hacquard2006) for a similar view). He discusses examples such as (40) to show that explicit cancellation systematically leads ‘to a certain oddness’ (Reference Bhatt, Shahin, Blake and Kim1999: 75).

(40) Last night, a masked assailant attacked me on my way home. I was able to wrestle him to the ground. #But I didn't do anything since I am a pacifist.

It is for this reason that Bhatt uses the term entailment to capture the conventional nature of actualisation. We agree with Bhatt that explicit cancellation leads to rather incongruous, if not contradictory, interpretations. The sentences in (41), which illustrate opportunity meaning and which have been taken from our dataset, are similar. The opportunity meaning resides in the fact that in both cases, external circumstances (subject-external source) make it possible for the subject referent to do something (narrow scope): discover something in (41a) and put an arm back and restoring movement in (42b). When explicitly cancelled (sentences in (42)), the resulting sequences seem hardly acceptable. In other words, the meaning that is communicated has a crucial role to play: if be able to is understood in terms of ‘ability’, the ‘cancelled’ readings are fairly natural. If, however, there is an ‘opportunity’ reading, it is harder to conceptualise the cancellation of actualisation.

(41) (a) But it was almost, think wonderful, that they were able to discover this. (BNC, spoken)

(b) Roy Tapping became the most famous microsurgery patient in the country, after his arm was severed in a work accident. He picked it up and carried it a mile across a field for help. Surgeons at nearby Stoke Mandeville Hospital were able to put it back on and have restored some movement. (BNC, written)

(42) (a) But it was almost, think wonderful, that they were able to discover this. ?But they didn't.

(b) Roy Tapping became the most famous microsurgery patient in the country, after his arm was severed in a work accident. He picked it up and carried it a mile across a field for help. Surgeons at nearby Stoke Mandeville Hospital were able to put it back on (?but didn't) and have restored some movement.

The question therefore is not whether actualisation arises as a (cancellable) particularised conversational implicature, but whether it should be analysed as a conventional implicature or as a GCI, both of which are triggered by specific linguistic expressions. The previous observations could be taken to suggest that actualisation is a conventional implicature, since this type of implicature cannot be explicitly cancelled (section 2.3).Footnote 12 While this view might be appealing at first, there are reasons to believe that a GCI account of actualisation is to be preferred. The previous discussion shows that actualisation with opportunity be able to seems to resist cancellation with adversative but-clauses. This does not mean that actualisation is generally cancellation-proof, however. As Jaszczolt (Reference Jaszczolt2009: 261) points out, Grice (Reference Grice1989: 44) originally identified two types of cancellability tests: explicit cancellation and contextual cancellation. The use of a but-clause is a prime example of explicit cancellation, which was shown not to be possible with actualised opportunity be able to. Alternatively, contextual cancellation ‘occurs when potential implicatures are “cancelled” in virtue of background information pertaining to the situation of discourse or widely understood context including co-text’ (Jaszczolt Reference Jaszczolt2009: 261) (also see Horn Reference Horn and Ward2004: 5, quoted in section 2.3).Footnote 13 It appears that actualisation with be able to is sensitive to this second type of cancellation. We listed in section 5 four different types of environments in which be able to does not communicate actualisation. The factors identified above (epistemic meaning, genericity, habituality, hypotheticality) constitute such cancellation contexts. This means that actualisation is, after all, not entirely cancellation-proof. More importantly, these contexts look exactly like the kind of contexts that GCIs are sensitive to. Indeed, contextual cancellation is said to relate to implicatures ‘which would have arisen for a particular construction had they not been prevented by the context’ (Jaszczolt Reference Jaszczolt2009: 261). This is exactly how GCIs were defined in section 2.3. In the case of actualised be able to, the notion of GCI therefore seems rather fitting as it enables us to capture both the conventional and pragmatic nature of actualisation. Context permitting, ‘opportunity be able to’ communicates actualisation. This is consistent with our findings in section 5 that actualisation is a conventional feature of the modal expression. And this is also consistent with our observation in section 6 that actualisation is sometimes not expressed because be able to falls under the scope of semantic categories that are by definition non-factual (i.e. epistemic modality, habituality, genericity, hypotheticality) and thus trigger non-actualised interpretations. The actualisation reading is generalised but does not arise in the specific contexts that we have identified.

An analysis of actualisation as a GCI thus enables us to explain the paradox identified in the introduction with regard to the truth-values of be able to. If both modality (non-factual) and actualisation (factual) are described as semantic properties of the modal expression, then one inevitably faces the challenge of reconciling apparently contradicting semantic values. When actualisation is understood as a GCI, there is no longer a paradox. When using be able to, only the modal value of possibility affects the truth of one's utterance. Actualisation, on the contrary, does not contribute to the truth conditional content of the modal sentence. While conventional, it is all the same pragmatic (i.e. ‘encoded non-truth-conditional’ content, in the four-class taxonomy to meaning presented in section 2.2). A theoretical framework which provides space for conventional pragmatics within particular constructions (e.g. Construction Grammar, cf. Leclercq Reference Leclercqto appear) seems particularly well suited to address the challenges discussed in this article. Actualisation is a conventional functional property of be able to, but it does not contribute to the truth-conditional content of the proposition expressed by the speaker. In Cappelle & Depraetere (Reference Cappelle and Depraetere2016), it is argued that a construction can short-circuit pragmatic meaning (cf. Morgan Reference Morgan1977). It could indeed be argued that by convention ‘opportunity be able to’ short-circuits the recovery of an actualisation implicature. That is, as opportunity conventionally communicates actualisation, there is no longer an inferential process that leads the addressee to recover actualisation, but there is a cognitive short-cut in the sense that ‘opportunity be able to’ is directly linked to the function of actualisation.

7 Conclusion

This article has shed new light on the meaning of the modal expression be able to. It is based on the empirical analysis of a large sample of examples from the BNC and on theoretical considerations concerning the semantics–pragmatics interface. First, it has been shown that be able to is mainly used to communicate ‘opportunity’ (Depraetere & Reed Reference Depraetere and Reed2011) rather than ‘ability’; it can also communicate the meanings of ‘permissibility’ and ‘general situation possibility’, which are usually associated with can and could. In other words, be able to is polysemous. Secondly, the empirical analysis has revealed that actualisation is a defining (and distinguishing) property of be able to, and that there is a firm link between actualisation and opportunity meaning. The next question was then to understand in what sense exactly actualisation is conventional. In the theoretical investigation we conducted it was argued that actualisation with be able to is best analysed as a generalised conversational implicature, which contributes to the conventional pragmatic layer of the modal expression. A view in terms of GCI also explains how be able to can encode two seemingly incompatible features: while modality is a conventional semantic feature of the modal expression, actualisation is a conventional pragmatic feature of be able to.