1 Introduction

The evidence from historical dictionaries is that 44–48 per cent of headword entries are borrowings from French and/or Latin into Middle English (ME) (Durkin Reference Durkin2014: 256–7). This is also the period when Norse borrowings, which must have entered the spoken language much earlier, appear in the textual record. It is generally accepted that large numbers of existing Old English-origin terms were replaced by these new borrowings in the late medieval period. In his study of the ME religious lexis up to 1350, Käsmann (Reference Käsmann1961: 31) observed that a considerable part of the Old English (OE) stock was lost and also noted areas where foreign lexis did not make any inroads at all, or else did so only later. He considered that loans and new formations are parallel processes, which occur when words become obsolete and need to be replaced (Reference Käsmann1961: 285). His focus was therefore on lexical replacement but he was concerned that the way that loans work within the ecology of existing words had not previously been investigated.

Studies of the lexicon of Middle English have generally conceptualised the relationship between incoming loanwords and native terms as one of competition; see, for example, Rynell (Reference Rynell1948), who examined the ‘rivalry’ of Scandinavian and native synonyms in Middle English. This perspective is also that adopted by Timofeeva (Reference Timofeeva2018), using a large religious lexis corpus. However, an initial study of a sample of 208 lexical ‘pairs’ (i.e. senses with two co-hyponyms in the ME period) conducted by the present authors suggested a different picture.Footnote 1 This study differed from Rynell's in not restricting the non-native lexis to terms of Scandinavian origin. The key findings were, first, that term replacement (of both native terms and loanwords) in the Middle English period is much less common than was expected. Secondly, when replacement did occur, loanwords were more likely to be replaced than native terms. Thirdly, fewer native words dropped out overall (up to 1800) than loanwords, though in the period pre-1500 they were proportionately more likely to drop out than were loanwords. It has been suggested that semantic shift, in particular specialisation and generalisation, were frequent consequences of the widespread borrowing of terms from French and Latin (Durkin Reference Durkin2014: 215, 409; Kay & Allan Reference Kay and Allan2015: 88). In our data, however, cases involving narrowing, broadening and metonymy, and those in which meanings were added without replacement of the core sense accounted for a very small proportion of outcomes of incoming lexis.

Those findings, though limited in scope, appeared to challenge established views concerning the effects of French and Latin vocabulary entering English in the late medieval period. We did not find evidence that the influx of loanwords resulted in a widespread relexification of Middle English (Schendl Reference Schendl and Trotter2000: 78; Trotter Reference Trotter, Bergs and Brinton2012: 1789). Instead of competition, we found co-existence between native and borrowed terms occupying the same semantic spaces as co-hyponyms, possibly contributing to the development of register variation in the emerging variety of Middle English.

The present article seeks to establish if this perspective is upheld when analysing a bigger dataset, and when senses with three and four co-hyponyms are also examined in order to track patterns of lexical replacement, retention and semantic change from the ME period to the present day to compare outcomes for native and non-native terms. A further reason for including larger sets of synonyms is to see if the link between lexical density and higher rates of word replacement observed in Present-day English (PDE) and some European languages (Vejdemo & Hörberg Reference Vejdemo and Hörberg2016) holds true for the ME period.

2 Dataset and methodology

The Technical Language and Semantic Shift project dataset comprises 5,276 ME words and 2,307 senses which have been organised into a semantic hierarchy based on the classification created for the Historical Thesaurus of English (HT).Footnote 2 This arranges words on the basis of hyponymic relations with superordinate (most general) terms at the top and technical (most specific) at the bottom. Vocabulary has been taken from the augmented dataset of the Bilingual Thesaurus of Everyday Life in Medieval England.Footnote 3 This includes the seven original occupational domains (Building, Domestic Activities, Farming, Food Preparation, Manufacture, Trade and Travel by Water) and two new ones (Hunting and Medicine), added to provide fuller coverage of medieval society. Studies of polysemy, obsolescence and replacement in the lexis of Middle English cannot hope to be exhaustive in the range of semantic domains they investigate. The selection of data for such studies has been undertaken in a number of different ways. Some studies focus on a single concept, for example Ehrensperger's (Reference Ehrensperger1931) examination of the ME vocabulary of dreaming.Footnote 4 Other studies have investigated a wider set of conceptualisations, but still within a certain semantic field, notably those by Diller, who focuses on the ME lexicon of Emotion, attempting to map the ME terms on to modern understandings of emotions. Changing conceptualisations motivate some studies of individual lexical fields, such as Diensberg's (Reference Diensberg1985) study of boy/girl-servant-child in ME. Rynell's approach was to study Scandinavian loanwords, across a wide range, without specification of semantic field (Reference Rynell1948: 13–17). The domains investigated in the present study, ranging over ordinary occupations, meant that we were able to include everyday vocabulary, known to have been influenced by Norse, as well as French, now shown to have substantially penetrated the domains in our study; and thanks to the inclusion of medicine we were also able to target the contribution of Latin. Further motivation to select a set of semantic domains came from the original aims of the HT. It was designed to enable us to consider the choices open to speakers, and which words were selected from the pool of available terms. The selection of a set of semantic domains, with language of origin information for each lexeme, allows us to offer some new evidence with which to address that question.

We recognise the difficulties associated with dating vocabulary items from the medieval period, and that historical dictionaries, such as the Middle English Dictionary (MED) and Oxford English Dictionary (OED) used here, are being employed for research in ways for which they were not designed. However, our interpretations are based on dates of attestation provided in the dictionaries, as these provide the best available information, particularly for a large-scale study that encompasses a variety of textual sources.Footnote 5 It should also be noted that despite the project's initial plan to focus on technical vocabulary, it quickly became clear that it is impossible to track semantic changes without including the general vocabulary at the higher levels of the semantic hierarchy, and so these terms were incorporated into the dataset.

Each subsection of the hierarchy is divided into levels of technicality (specificity) known as Category Levels (CLs), with superordinate senses at CL0 and hyponymic senses below at CL1 through to CL4. We now illustrate the structure with an extended example. The hierarchy extract begins with vocabulary below the superordinate term Manufacture of textile fabric (cloth-making, drapinge, draperi(e) ) at CL0, with the second most general lexis listed underneath at CL1: One who makes cloth (clother, draper, cloth-maker, teler) and Weaving (webbing(e), weving(e), texture, endrapering). Senses at CL3 represent the most specific in this subsection: Beam of a loom (web-bem, bem), Shuttle (shitel), Reed/Slay (sleie) and One who weaves tapestries (tapicer, tapistere).

It can be seen that some OE terms have lasted through to the present day, e.g. web-bem Footnote 6 or bem,Footnote 7 and sleie Footnote 8 (parts of a weaver's loom). The native word lome Footnote 9 (loom) is not attested in the sense ‘a machine in which yarn or thread is woven into fabric’ until the 1380s but is recorded c.900 in OE under the more general sense ‘an implement or tool of any kind’. A slightly earlier term for the weaver's loom is provided by the native compound web-lome,Footnote 10 first recorded in 1338. This is still in use but marked as historical and rare by the OED3, with the abbreviated form loom now the standard term in PDE.

Other native words are joined under a sense in the ME period by one or more loanwords. At CL1, under ‘weaving’, we find native webbing(e) Footnote 11 (which becomes obsolete in this sense in the 1600s),Footnote 12 and weving(e) Footnote 13 (still in use today), joined by the Latin borrowing texture Footnote 14 which remains in use in that sense until the 1700s. There is also a short-lived, fourth co-hyponym endrapering Footnote 15 attested once in c.1461 and derived from the French verb, endraper. Similarly, also at CL1, under ‘one who makes cloth’, we find two native terms, clother Footnote 16 and cloth-maker Footnote 17 (both of which have survived), supplemented by two French-origin borrowings in the late Middle Ages. The first loanword, draper,Footnote 18 is attested in an English-matrix citation c.1390 and then shifts in sense in the 1400s from ‘cloth maker’ to ‘cloth dealer’, its sense in PDE. The second, teler,Footnote 19 appears as a surname in English documentary sources from 1193 to 1332 before a final appearance in a literary text composed ?a.1400. In other cases, we find only non-native terms under a given sense, such as tapicer,Footnote 20 tapeter(e) Footnote 21 and tapistere,Footnote 22 all Latin and/or French borrowings meaning ‘one who weaves tapestries’. The first and third of these loanwords are cited in the 1800s but tagged as historical or rare terms, whereas the second became obsolete in the 1400s.

The hierarchy extract also highlights a variation in number of words per sense (lexicalisation). Shitel is the only word listed in the ME period under ‘shuttle’ whereas the sense ‘one who weaves’ has five co-hyponyms (webbe, webbester(e), webber(e), wever(e) and tapener). This study focuses on senses from across the hierarchy which have either two, three or four words attested up until 1500: these groups of words are referred to below as lexical pairs, trios and quads, and the availability of this information plays an essential part in the analyses presented in this study.

The pilot study leading to this investigation analysed replacement and retention patterns in a sample of 208 lexical pairs (i.e. 416 words) taken from four domains: Domestic Activities, Hunting, Manufacture and Medicine (Sylvester, Tiddeman & Ingham Reference Sylvester, Tiddeman, Ingham and Mazzonforthcoming). This article extends the dataset and analyses to a total of 1,606 words, divided across 453 two-item senses, 100 three-item senses and 100 four-item senses. These pairs, trios and quads are taken from all nine of the project's domains, as shown in table 1.

Table 1. Number of word and senses for lexical pairs, trios and quads analysed, per domain

Overall, two-item senses account for 474 out of 2,307 (or 21%) of those found in the project hierarchy. All two-item senses were examined, except twenty-one cases, which were eliminated from the data because one or both of the terms is of uncertain etymology or because the terms involved represent co-hyponyms within a category but are not synonyms (e.g. fesaunt/partrich(e) under the sense ‘Specific game birds’). This left a total of 453 pairs (906 words) included for analysis.

The total number of lexical trios in the project dataset is about half that of pairs: 236 senses (or 10% of the hierarchy) have three words. To collate a sample of 100 of these trios, twelve were taken from taken from Farming (the largest domain in our corpus) and eleven from each of the other eight domains. Senses with words with uncertain etymologies were again discarded.

The number of lexical quads available for analysis is much smaller again: only 129 senses (or 6% of the hierarchy) have four terms. In this case, it was not possible to balance examples from all nine domains as options were limited once four-item senses that included uncertain etymologies were excluded. For this reason, some domains (especially Farming and Manufacture) are more heavily represented than others in the sample of 100 quads.

Once the samples had been collated, each word in the pairs, trios and quads was tagged as either ‘native’ or ‘non-native’ based on their language(e)s of origin using the following system of categorisation:Footnote 23

N = Native:

-

Single terms of native origin, e.g. wode ‘wood’ (OE); harwen ‘to harrow land’ (OE)

-

Compound terms where both elements are of native origin, e.g. ston barwe ‘vehicle for moving stone’ (OE-OE); ei(e)-salve ‘preparation for treating the eyes’ (OE-OE).

-

Words of non-native origin attested in OE and therefore assumed to have been assimilated by the ME period, e.g. plastre ‘plastering’ (OE;Latin;Old French); ferie ‘ferry’ (OE;Old Scandinavian).

NN = Non-native:

-

Single terms of non-native origin first attested in the ME period, e.g. pelliper ‘worker with skins/hides’ (Latin); mincen ‘to cut food into small pieces’ (Old French).

-

Compound terms made up of two loanwords, e.g. dale-bagge ‘bucket for bailing out water from boat’ (Middle Dutch;Middle Low German-Old Scandinavian); fervent must ‘must to make alcoholic drink’ (Latin;Old French Latin;Old French).

-

Compound terms made up of a loanword and a native term, e.g. chaloun-makere ‘maker of blankets’ (Old French-OE); chaffe-net ‘net for catching birds’ (Old French-OE).

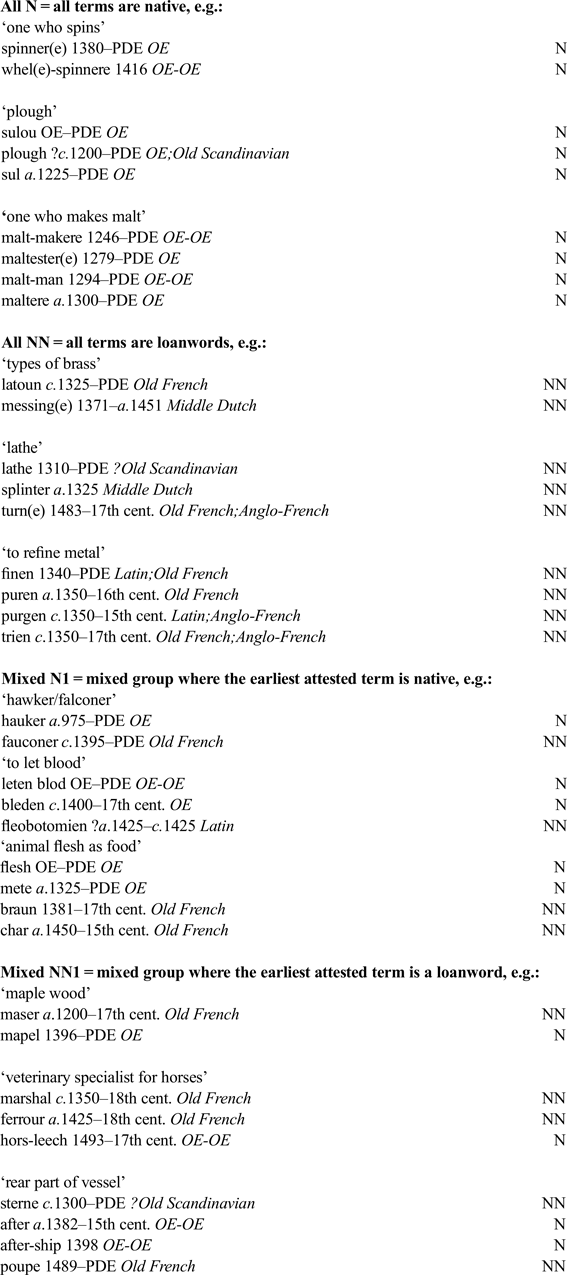

The next stage of the investigation involved categorising each pair, trio and quad based on whether it was composed of all native words, all loanwords or a mixture of the two. The focus of the categorisation remains the earliest attested term in any group of words and whether this term is native or a loanword. Thus, for example, in Mixed N1 trios and quads, the earliest attested term is always native but the incoming terms may be all loanwords or a mixture of non-native and native terms. The four language group types used are outlined below with examples given in each case from two-, three- and four-item senses:Footnote 24

Finally, once the dataset had been collated and categorised, a typology (below) was devised to compare long-term semantic outcomes across the lexical groups. As with the language labelling, the focus here is on the word in the group – tagged as Term 1 – which is attested first, using the dates given in the OED and MED. Term 2 is the second to be attested, with trios also having a Term 3 and quads, a Term 3 and Term 4. Outcomes track whether Term 1 is retained until PDE, whether it is replaced or shifts to another sense, following the arrival of incomers into the semantic space in the ME period.

A word is defined as occurring in PDE if it is attested in the nineteenth century or later, unless an OED entry with a final citation in the 1800s states that a word is obsolete, e.g. stopp(e) (‘pail/bucket’) or woodyer (‘forester’).Footnote 25 The ME period is defined as 1100–1500.

Note that in addition to tracking semantic shifts, where the original sense is entirely replaced, we have also included semantic changes in which new meanings develop as a result of broadening, narrowing or metonymy, and the original meaning continues in use. For example, mortar is found in PDE in both the original sense ‘paste-like material for joining stones/bricks’ and the additional, more generalised sense ‘any substance that resembles or serves a similar purpose to mortar’. Our study of narrowing and broadening in the domains of Farming and Trade found that considerably fewer than half the cases involved core sense replacement (31 out of 81), e.g. warren from ‘land enclosed for breeding game’ to ‘land enclosed for breeding rabbits’; grocer from ‘merchant who sells any item in gross/wholesale’ to ‘merchant who sells spices, dried fruits, sugar, wine etc.’. Additionally, only eighteen words in the dataset undergo shift involving core sense replacement within the Middle English period, e.g. mercer (from ‘merchant’ to ‘merchant who deals in textiles’); cattle (from ‘personal property in general’ to ‘livestock’). We now illustrate in detail the outcomes for the pairs, trios and quads in our dataset. The outcome types are described below, with examples specific to pairs, trios and quads given in tables 2–8. Note that an asterisk denotes restriction to regional or archaic use in PDE.

Type 1 outcome (a case of replacement): an existing term (Term 1) drops out of use in a particular sense (relevant to our domains) before the PDE period following the arrival of incoming terms (Terms 2–4) during the ME period, as shown in table 2.

Table 2. Type 1 outcomes for pairs, trios and quads

Type 2 outcome: an existing term (Term 1) is joined by incoming terms (Terms 2–4) in a particular sense during the ME period, all or some of which then drop out of use before the PDE period, as shown in table 3.

Table 3. Type 2 outcomes for pairs, trios and quads

Type 3 outcome: an existing term (Term 1) is joined by incoming terms (Terms 2–4) in a particular sense during the ME period. All terms go on to exist as (near) synonyms until the PDE period, as shown in table 4.

Table 4. Type 3 outcomes for pairs, trios and quads

Type 4 outcome: an existing term (Term 1) is joined by incoming terms (Terms 2–4) in a particular sense during the ME period. One or all of the incoming terms then undergoes semantic change through narrowing, broadening or metonymy prior to 1500, as shown in table 5.

Table 5. Type 4 outcomes for pairs, trios and quads

Type 5 outcome: an existing term (Term 1) is joined by incoming terms (Terms 2–4) in a particular sense during the ME period. Term 1 then goes on to undergo semantic change (through narrowing, broadening or metonymy) prior to 1500, as shown in table 6.

Table 6. Type 5 outcomes for pairs, trios and quads

Type 6 outcome: an existing term (Term 1) is joined by incoming terms (Terms 2–4) in a particular sense during the ME period. All terms go on to undergo semantic change (through narrowing, broadening or metonymy) prior to 1500, as shown in table 7.

Table 7. Type 6 outcomes for pairs, trios and quads

Type 7 outcome: all terms are hapaxes in a particular sense, attested once or in a single text during the ME period, as shown in table 8.

Table 8. Type 7 outcomes for pairs, trios and quads

Table 9 shows the distribution of these lexical group types across the dataset.

Table 9. Number and percentage of language group types for lexical pairs, trios and quads

In all lexical group types (pairs, trios and quads) we find that senses populated only by loanwords are more common than those populated by native terms only. When we isolate pairs (which form the bulk of our data), there is a roughly equal three-way split between all-native pairs, all-loanword pairs and mixed pairs (Mixed N1 and Mixed NN1 added together).

Mixed groups are the most common overall and their likelihood increases with the number of words per sense. This is to be expected since there is less chance of all terms being either native or non-native, the greater the number of words in a group. The earliest attested term in a mixed group is, understandably, more than twice as likely to be native (33%) than non-native (14%) across the dataset.Footnote 26 Additionally, in pairs and trios, all-loanword groups are more common than mixed groups where the earliest attested term is a loanword. However, once we move up to four words per sense (i.e. quads), all-loanword groups become less common.

3 Results

3.1 Overall outcome distribution across the dataset

First, we examine the proportions of each outcome type across the 653 lexical groups, regardless of the language(s) of origin of the words comprising each pair, trio or quad. Results, given in table 10, show that Type 2 outcomes (an existing term is joined by incoming terms in a particular sense during the ME period, all or some of which then drop out of use before the PDE period) are the most common across the pairs, trios and quads in all the semantic domains examined.

Table 10. Number and percentage of outcomes across dataset

3.2 Distribution of outcomes based on language(s) of origin

The next stage of the investigation examines proportions of each outcome type based on whether the component terms of each lexical pair, trio or quad were of native or non-native origin, or of a mixture of the two. Results are given in table 11.

Table 11. Number and percentage of outcomes in native, non-native and mixed pairs, trios and quads

Across the whole dataset, Type 2 (incoming terms fail to replace the existing term) remains the most common outcome, regardless of the language(s) of origin of the component terms involved, i.e. it is the most common outcome for All-N, Mixed N1, Mixed NN1 and All-NN subgroups when pairs, trios and quads are added together.Footnote 27 Similarly, proportions of outcomes involving narrowing, broadening and metonymy (Types 4, 5 and 6) are very low across all combinations of native and non-native terms.

There is no language subgroup where Type 1 (replacement of an existing term by incomers) is the most prevalent outcome. As in the pilot study, it is not the case that loanwords regularly oust native terms. In mixed pairs, there is no great difference in the rate of non-native terms replacing native ones, compared to the other way around. Mixed N1 pairs (i.e. N&NN) have only a 3 per cent higher rate of a Type 1 outcome at 26 per cent than Mixed NN1 pairs (i.e. NN&N) at 23 per cent. With trios and quads, an existing loanword in a mixed group (Mixed NN1) is much more likely to be replaced by incoming terms than is an existing native term. Hence when pairs, trios and quads are added together, 26 per cent of native Term 1s in mixed groups are replaced, compared to 35 per cent of loanwords.

Nevertheless, it is also important to note that Type 3 outcomes (where all terms remain in use until PDE as long-term synonyms) are much more common overall when all words under a sense are of native origin: 34 per cent for All N, compared to 25 per cent for All NN, 15 per cent for Mixed N1 and 12 per cent for Mixed NN1. Type 1 (replacement of Term 1) is also the least likely outcome (17%) when all the words are native, compared to 22 per cent for All NN, 26 per cent for Mixed N1 and 35 per cent for Mixed NN1.

In essence, whilst Type 2 outcomes (failed replacement of Term 1) are the most common across all language combinations, Type 1 (replacement of Term 1) is the second most common outcome in mixed language groups, whereas Type 3 (long-term synonymy) is the second most popular outcome in non-mixed language groups, be they all native terms or all loanwords.

Finally, out of the eighteen double hapaxes in the dataset (Type 7), the majority (eleven) are composed of two loanwords and a further five are mixed pairs. Only two out of the eighteen are composed of two native terms. This further suggests that loanwords have lower chances of becoming established in the language.

3.3 Revisiting attestation dates

The procedure adopted in this analysis involves classifying pairs of lexemes as Term 1 and Term 2 when the former was first attested before the latter, and similarly mutatis mutandis, for trios and quads. Our classification is of course only as good as the reliability of citation evidence for when lexical items entered the language. First citation dates have been used here as proxies for lexical developments in the language in the medieval period, which seemed inescapable if the question was to be considered at all. Nevertheless, we remain aware of the uncertainties involved in dating one item as ‘earlier’ than another on the basis of dictionary citations. Cases where the items are first recorded only within a short time span of each other must be seen as particularly problematic, especially bearing in mind the accumulation of ME texts in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth century.

It was therefore decided to sample how much of the data was derived from items first attested only twenty-five years or less apart, a figure traditionally taken as the span of a single generation. We wished to know how far our conclusions would remain valid if these were excluded. The issue seemed most significant where one of the two items is categorised in our analysis as replacing another, i.e. with Type 1 and Type 2 outcomes. Where both items remain in the language (Types 3–4), it matters less to our overall argument in favour of lexical co-existence which item entered English first.

Accordingly, all 80 mixed pairs in outcome Types 1 and 2 with a native first term (see table 11) were examined to see how many pairs of items showed citation dates within twenty-five years of each other. This was found to be the case with only 13 pairs out of 80 (16%). From this sample, it can be seen that the great majority of outcomes identified did not depend on the assignment of a lexeme to Term 1 status where the second term was attested only shortly afterwards.

3.4 Focus on Type 1, 2, 3 outcomes only, based on language of Term 1 and split by domain

The next stage of analysis considers the three main outcomes only (Types 1, 2 and 3) which, as seen in table 11, account for 93 per cent of the dataset. Results were divided into two subgroups labelled T1 N and T1 NN (depending on whether Term 1 in each lexical pair, trio or quad is of native or non-native origin), as given in table 12.

Table 12. Number and percentage of Type 1, 2 and 3 outcomes with native and non-native Term 1

Type 2 (Term 2 falls out of use without replacing Term 1) is the most common scenario in all cases, whether T1 is N (52%) or NN (49%). T1 is retained in 74 per cent of cases overall (i.e. Type 2 + 3 combined) and T1 is replaced in only 26 per cent of cases (i.e. Type 1): this result is identical to that of the pilot study.Footnote 28 Type 2 is the most common outcome across all nine domains. There are some variations, however: proportions of Type 2 rates range from 65 per cent in Travel by Water to 38 per cent in Farming. Similarly, among Type 1 outcomes, Food Preparation has a noticeably higher rate of T1 replacement (40%) than the other domains, whilst Building is particularly low at just 14 per cent.

Borrowed T1s are more likely to be replaced by incomers than are native T1s: the replacement rates for existing terms of OE origin is 23 per cent compared to 29 per cent for existing terms which are loanwords. Conversely, native T1s are slightly more likely to be retained whilst incomers drop out: Type 2 outcome rates are 52 per cent for native T1s and 49 per cent for non-native. Again, not all individual domains conform to this pattern. In Trade and Manufacture, native T1s are more likely to be replaced (Type 1) and in Hunting loanwords are proportionately more likely to remain in place whilst incomers become obsolete (Type 2). Reasons behind all these variations in replacement and retention per domain are not immediately evident, but seem unrelated to the percentage of non-native lexis in any given domain.Footnote 29

3.5 Dates of obsolescence for Term 1 in Type 1 outcomes in pairs/trios/quads combined

The final analysis considers the date of obsolescence of the 155 existing words (Term 1s) that are replaced by incoming words in Type 1 outcomes. Occurrences, divided into half-centuries, are given in table 13.

Table 13. Dates of obsolescence for native and non-native existing terms which are replaced (Type 1 outcomes)

The drop-out rate in the ME period is 7 per cent higher for native than for non-native T1s, a result which again closely matches that of the pilot study, discussed below.Footnote 30 Forty-six out of 82 native T1s (or 56%) are obsolete by 1500, compared with 36 out of 73 (or 49%) of non-native T1s. Overall, 82 out of 155 T1s (or 53%) have become obsolete by the end of the 1400s. Crucially, the time period with the highest drop-out rate for all T1s, regardless of language of origin, is the end of the Middle Ages, from 1400 to 1499. This indicates that obsolescence was not the immediate consequence of the lexical borrowing. This can be seen in figure 1. This presents the same results as table 13 but as percentages of native and non-native T1s, divided by full centuries.

Figure 1. Dates of obsolescence for Term 1s which are replaced (Type 1 outcome)

When obsolescence dates are divided into lexical groups, the dropout rate in the ME period becomes gradually higher as we move from pairs (51%) to trios (53%) to quads (59%), as shown in table 14. This suggests that there may be a link between lexical density in a semantic space and the likelihood of Term 1 replacement occurring prior to the sixteenth century, an interpretation which supports the functionalist theoretic idea of systemic regulation to prevent the proliferation of synonyms to facilitate communication (Samuels Reference Samuels1972: 65).

Table 14. Number and percentage of T1s in pairs, trios and quads which are replaced during and after the Middle English period

4 Discussion of main results

Analysis of the extended dataset confirms the key finding of the pilot study: replacement did occur but is rarer than expected, and wholesale relexification did not happen during the late Middle Ages. Overall, only 24 per cent of existing terms (see table 10) – or 26 per cent once outcomes involving shift or hapaxes are discounted – are ultimately replaced when one or more terms join the semantic space in the ME period. All lexical groups in all domains have Type 2 (Term 2 falls out of use without replacing Term 1) as their most common outcome, regardless of whether the terms are native or loanwords. In these cases, Term 1 remains in use until PDE and at least one incomer in the group drops out and becomes obsolete. This suggests that when an existing term is already established under a sense, it tends to be retained. Furthermore, Type 3 outcomes (long-term synonymy where Term 1 remains in use alongside an incoming term or terms) are the second most common outcome for pairs, and third most common for trios and quads (see table 10)

It is not the case that the outcomes are influenced by a scarcity of loanwords in the semantic domains we examined; on the contrary, loanwords are abundant in the dataset: 69 per cent of the lexical pairs include at least one non-native term and 34 per cent consist of two non-native terms. In trios, 89 per cent include at least one loanword, with 21 per cent consisting of all loanwords. In quads, equivalent figures are 71 and 29 per cent, respectively (see table 2). The extent of borrowing into Middle English, mainly from French and Latin, is well known so these high percentages are unsurprising. However, language of origin does not seem to have the effect on term replacement that might have been expected from standard accounts.

In mixed language groups, Term 1 replacement is more likely if the earliest attested word is a loanword (35%) in a mixed group, than if it is a native term in a mixed group (26%) (see table 11). This trend is reversed in pairs where native terms are 3 per cent more likely to be replaced by a loanword (e.g. native breden being replaced by borrowed frien under the culinary sense ‘to fry’) than vice versa (e.g. borrowed lof being replaced by native weder-side under the nautical sense ‘side of vessel towards the wind’). In trios and quads, loanwords have significantly higher replacement rates, however: 24 per cent more Type 1 outcomes for Mixed NN1 compared to Mixed N1 in trios, and 26 per cent more in quads. These statistics argue against widespread ousting of OE terms by loanwords entering the language in the ME period.

Outcomes were also examined on the basis of the language of Term 1 only, regardless of the language of incoming co-hyponyms. Here, it was found that again loanwords have a higher probability of being replaced in the long run (i.e. any time before the nineteenth century) than do native terms (see table 12), For example, in the pair under ‘vinegar’, borrowed aisel (Term 1) is replaced by borrowed vinegre (Term 2), and under ‘mop/swab’, borrowed mappel (Term 1) is replaced by native malkin (Term 2). The difference in the probability of a Type 1 outcome across pairs, trios and quads depending on language of origin is small (6%) but worth noting because it generally favours NN T1s as the item being lost: 29 per cent for non-native T1s and 23 per cent for native T1s overall. This trend is found in seven of the nine domains. The exceptions are Manufacture and Trade where Term 1s of OE origin have a higher rate of replacement, e.g. in the quad under ‘to melt metal’, Term 1, yeten (native), falls from use as does Term 2, wellen (native), whilst Term 3, melten (native), and Term 4 liquefien (borrowed) remain in use until PDE.

When dates of obsolescence for replaced Term 1s are examined (table 13), there is a distinction to be drawn. Although native terms are less likely than loanwords to drop out any time before PDE overall, they are proportionately more likely to fall from use prior to 1500 when they do become obsolete: e.g. in the trio under ‘one who combs textile material’, native tosere (attested 1249) falls from use in the second half of the 1400s, after having been joined by borrowed cardester and carder in the 1300s. The dropout rate in the ME period is 7 per cent higher for native Term 1s, compared to non-native. This difference is worth noting, but again does not represent a huge wave of native term replacement in the late Middle Ages. It is also important to recall that the peak period of Term 1 obsolescence up until the 1800s, for both native terms and loanwords alike, is 1400-99. This trend reflects the conventional view of the fifteenth century as an especially tumultuous time for English lexis with a high turnover of vocabulary; however, as has been noted, such cases of replacement are not in the majority across the dataset as a whole.

Results also show a link between the number of incoming terms joining Term 1 in the ME period and the likelihood of it being replaced at any time before PDE. The Type 1 outcome rate for two-item senses is 21 per cent but rises to 30 per cent for three-item and to 32 per cent for four-item ones (see table 10). Furthermore, the probability of Term 1 becoming obsolete prior to the sixteenth century also increases as the number of co-hyponyms under any given sense rises from two (51%) to three (53%) to four (59%) (table 14). This ties in with the findings of a study of modern English (and Swedish, Danish and German) which established a link between lexical density and higher word replacement rates (Vejdemo & Hörberg Reference Vejdemo and Hörberg2016). The results of our investigation seem to confirm the functionalist theory that ‘overcrowding’ in a semantic space can lead to terms becoming obsolete and falling from use.

Finally, proportions of outcomes involving narrowing, broadening and metonymy were low, regardless of language of origin and even when semantic changes that fall short of the replacement of the core sense are included (see table 11). Outcome types 4, 5 and 6 accounted for only 31 (or 6%) out of a total of 653 cases, e.g. borrowed wareine narrowing in sense from ‘enclosed land for breeding game’ to ‘enclosed land for breeding rabbits/hares’; native chiken broadening from ‘young chicken’ to ‘chicken’; native minte undergoing metonymic shift from ‘coins’ to ‘place where coins are made’. Our analysis supports findings regarding these kinds of shift from both the pilot study on a subset of lexical pairs and another focused on narrowing and broadening in a subset of two domains.Footnote 31 These too found that rates of autohyponymy, where the same word may be used as both a hypernym and a hyponym so that it is ‘polysemous with a broader and a narrower sense that occupy different levels in a taxonomic hierarchy’ (Koskela Reference Koskela and Benczes2011: 127), across their respective datasets were lower than expected, given that specialisation and generalisation of native terms have been noted as common consequences following the influx of French and Latin loanwords into the language the ME period (Durkin Reference Durkin2014: 215–17, 409; Kay & Allan Reference Kay and Allan2015: 88).

5 Conclusion

This investigation made use of a set of lexical data ranging from the most specific terms at the bottom of the lexical hierarchy to the most general terms at the top, in order to examine the effects of the extensive lexical borrowing of the ME period on both native terms and loanwords. Our data allow us to take up the challenge offered by Käsmann (Reference Käsmann1961: 18) of considering the effect of loans on the semantic system. The Bilingual Thesaurus and the additional work of our project meant that we were able to provide findings of much wider scope than Käsmann's examination of a single semantic field (remarkable though his work was for the period in which it was undertaken), and Rynell's (Reference Rynell1948) study of lexical pairs, which was confined to Scandinavian-origin loans and did not take account of other foreign-origin or native synonyms.

Our results show that the tendency in traditional accounts to highlight large-scale lexical replacement and semantic shift in the ME period resulting from extensive borrowing is not borne out. What we found, rather, is that loanwords did not generally oust native terms; indeed, there is not much difference in replacement rates for non-native terms replacing native ones and vice versa. Across all our data, the most common outcome is that the first term in any group of two, three or four co-hyponyms is likely to remain in the language, including when it is joined by a loanword.

The guiding metaphor of competition, most usually conceptualised as one in which incoming loanwords from French and Latin challenged the native terms for a place in the lexicon, turns out not to be representative of the majority of lexical replacement and obsolescence that we see in the ME period. This suggests that this metaphorical construct may be limiting our understanding of the relationship between the vocabularies of the languages in contact in medieval England. We see further evidence of this in the comparative rarity of semantic changes undergone by native terms, a surprising finding in view of the widespread idea that where they did not replace native terms, loanwords borrowed into ME caused native terms to shift into different areas of their variational space (Smith Reference Smith1996: 125; Kay & Allan Reference Kay and Allan2015: 86–8). It seems possible that the tolerance of a range of co-hyponyms to express particular concepts became more prevalent during the ME period as English began to be used more widely as a language of record. The extension of functions meant that English needed to develop its range of registers. This topic is beyond the scope of the present study, but it seems to us that this enlargement of the vocabulary was an essential part of its becoming a fully developed language variety and part of the process of standardisation, the beginnings of which we witness in the ME period (Sylvester Reference Sylvester and Wright2020).