1 Introduction

The derivational suffix -ish has undergone a remarkable development in the history of English, compared to both other English derivational affixes, as well as affixes from other European languages. As the title of this article indicates, -ish is characterized by a trajectory of change that leads from its original, nationality-denoting usage (as in englisc) to coexisting but semantically diverse usages in Present-day English (PDE) involving a wide array of bases (basically, whatever-ish). While the historical development of -ish derivation has been dealt with in various previous publications, a large-scale corpus-based investigation of data from all the main historical periods of English is still pending, particularly as regards an analysis of the suffix's changing productivity.

Previous empirical studies investigating -ish derivation at earlier stages of English are not genuinely diachronic in nature in that they focus on one language period only, rather than the large-scale development. For example, Mateo Mendaza (Reference Mateo Mendaza2015) compares Old English (OE) -isc to two other adjective-deriving suffixes, namely -ful and -cund, and shows that -isc is the most productive in terms of productivity scores such as Narrow Productivity and Global Productivity, which eventually led to the ousting of -cund, an otherwise functionally equivalent rival. Dalton-Puffer (Reference Dalton-Puffer1996) investigates the impact of French on Middle English (ME) morphology and contrasts newly added Romance affixes to the Germanic ones inherited from Old English. Based on the comparatively small ME sections of the Helsinki Corpus, she concludes that -isc declined in frequency after it had lost its original function of deriving ethnonymic adjectives, which led to -ish being ‘free to look around for other jobs in the derivational system and thus [beginning] to attach to more common nouns and to adjectives’ (Dalton-Puffer Reference Dalton-Puffer1996: 173), an idea that she admits has to remain ‘speculative’ for lack of conclusive data. Following up on Dalton-Puffer (Reference Dalton-Puffer1996), Ciszek (Reference Ciszek2012) seeks to shed further light on the alleged decline in frequency and productivity of ME -ish by comparing OE to ME. She underscores empirically that the nationality-denoting function of -ish derivation declined dramatically in ME as it came into serious competition not only with the Romance affixes -ian, -an, -ine and -ite, but also with periphrastic of NPs. Apart from these studies, those accounts that attempt at a diachronic sketch of the -ish suffix across the ages are not empirically validated (see, for example, Marchand Reference Marchand1969: 305f.). Our corpus study seeks to fill this research gap by empirically tracing -ish’s path of development over the timespan of more than ten centuries. What is more, the corpus findings are discussed against the backdrop of the theoretical literature on -ish, thus contributing to a reconciliation of empiricism and morphological theorizing.

The article is structured as follows: section 2 provides a brief outline of the characteristic features of the derivational affix -ish, as well as the more exceptional properties -ish displays vis-à-vis well-established morphological principles and constraints. In order to shed light on the out-of-limits behavior of -ish, we conducted an in-depth corpus-based analysis, the data and methodology of which is sketched in section 3. Section 4 presents the results of this analysis, with a thorough description of the spread of -ish derivatives from OE to twentieth-century English, while section 5 discusses the observable spread of -ish derivatives across time in terms of productivity. Against the backdrop of our corpus findings, section 6 then reassesses various theoretical accounts. Section 7 concludes with a brief summary and outlook.

2 On the crosscategoriality and multifunctionality of -ish

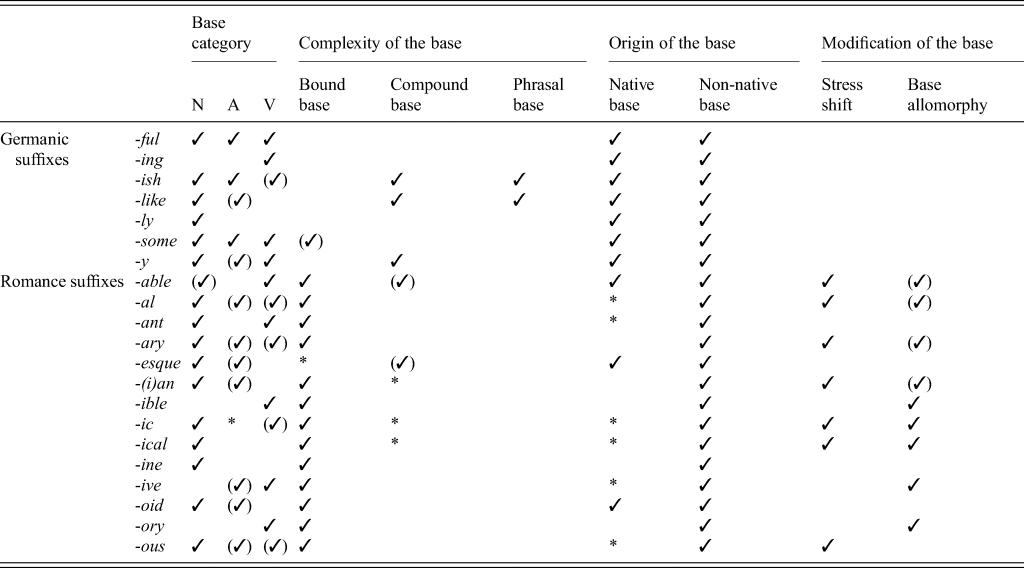

The fact that -ish is versatile in nature and relatively unrestrained is widely acknowledged in handbooks on English word formation (see, e.g., Marchand Reference Marchand1969: 305f.; Plag Reference Plag2003: 96; Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Lieber and Plag2013: 311, passim). Not only can -ish attach to a wide array of different word categories, the bases may also differ in degrees of complexity; albeit originally a Germanic suffix, it also readily combines with non-Germanic elements. Admittedly, such promiscuous behavior is not something exclusive to -ish derivation; on the contrary, it seems to be characteristic of quite a number of English affixes that they do not obey formal or etymological restrictions. Nevertheless, as the overview of adjective-deriving suffixes in table 1 below (adapted from Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Lieber and Plag2013: 290) illustrates, -ish is extraordinary in that it comes with the full package, so to speak, displaying all properties that are typical of Germanic suffixes across the board.

Table 1. Formal characteristics of adjective-forming suffixes

✓well-attested (✓) infrequently attested * isolated examples

Like its Germanic ‘siblings’ -ful, -some and -y, -ish attaches to nominal (1), adjectival (2) and verbal bases (3) (though only infrequently so in the latter case). Furthermore, as Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Lieber and Plag2013: 290) specify in a footnote to their table, -ish may also ‘occasionally’ take pronominal (4) and numeral bases (5) – yet this acknowledgement still does not give full merit to the wealth of base categories that -ish can combine with, for what is missing from the full picture as attested in PDE data are proper nouns (6), adverbs (7) and quantifiers (8):Footnote 2

(1) nominal bases: apish, clownish, feverish, hellish, liverish, popish, whorish

(2) adjectival bases: awkwardish, baddish, earlyish, pale-ish, quickish, warmish

(3) verbal bases: garish, snappish, ticklish,

(4) pronominal bases: selfish

(5) numeral bases: 7.30-ish, elevenish, forty-fiveish, one-ish

(6) proper noun bases: Al Caponish, James Deanish, Haydnish, Rossinish

(7) adverb bases: forever-ish, offish, uppish

(8) quantifier bases: more-ish

What is more, the base may differ in degrees of complexity: apart from simplex nominal bases (1), Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Lieber and Plag2013: 290) identify compounds (9) as complex nominal bases. Nominal derivatives (10) complete the list.Footnote 3 Moreover, -ish may attach to even more complex bases, viz. phrases (11), thereby surpassing its close rival -y (even though -y might not be too close behind in that respectFootnote 4):

(9) compound noun bases: eyebrowish, scout-masterish, nightmarish, tomboyish

(10) derived noun bases: lawyerish, bit-playerish, game-keeperish

(11) phrasal bases: no-howish ‘know-howish’, first-nightish, old-maidish, out-of-the-wayish, other-worldish

The versatility of -ish, as illustrated in (1) to (11), goes along with a conspicuous incapacity to combine with bound bases or to induce base modification by means of stress shift or base allomorphy.Footnote 5 At the same time, the fact that -ish does not combine with bound bases at all is exactly what makes it readily available for an extraordinary variety of bases, ranging from the monomorphemic kind via more complex word formations to the phrasal level. Moreover, the resulting abundance of -ish derivatives seems to have facilitated the development of clitic -ish in the nineteenth century.

As concerns the etymological origin of the base, we find Germanic roots (12) – which of course befits the Germanic origin of -ish – but also Romance roots from Latin or French (13), as well as roots ultimately originating in Greek or other languages (14), resulting in hybrid formations (which, however, is not too unusual for affixes of Germanic origin in general):

(12) Germanic roots: darkish, fattish, goodish, smartish, tightish, wildish, youngish

(13) Romance roots: amateurish, coquettish, vapourish, vinegarish, vulgarish

(14) Greek (via Latin and Germanic) devilish, Greek (via Latin) popish, Arabic ghoulish, Irish streelish

What clearly distinguishes -ish from its Germanic adjective-deriving siblings is the fact that it has come to serve several functions in the course of time, thus resulting in an overall more colorful career than, e.g., Dutch and German -isch or Scandinavian -(i)sk.Footnote 6 The original function of -ish is to derive ethnonymic adjectives, thus denoting nationalities such as English, British or Spanish, a characteristic feature that English -ish shares with its cognates in related Germanic languages. Today, the original nationality-denoting sense goes hand in hand with, to use Kuzmak's (Reference Kuzmack2007: 1) labels, the associative sense ‘of the character of X, like X’, as in summerish, monsterish or James-Deanish.Footnote 7 While this sense, too, is evidenced in the other Germanic languages, the approximative sense ‘somewhat X, vaguely X’ is clearly exclusive to English -ish; this sense is most prevalently instantiated when attached to adjectival bases as in freeish or greenish, in which cases -ish does not have a word class-changing effect, but ‘[i]nstead moderates or attenuates the reference of the adjective’ (Dixon Reference Dixon2014: 119). The same semantic effect can also be observed with numeral bases as in fourteenish or 1977-ish. It is important to emphasize that, in such cases, -ish does not serve to denote an unequivocal relatedness as with the associative sense, but on the contrary an ultimate dissimilarity. To spell this out, freeish is just kind of free (but actually implies that someone is still captivated), and something that is characterized as 1984-ish is vaguely reminiscent of Orwell's novel but definitely not something that is actually part of it.Footnote 8

Lastly, a further route of development that only English -ish has taken is the evolution of ish as a free lexical item, functioning as an epistemic marker (Traugott & Trousdale Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 236f.):Footnote 9

(15) Frank asked if they were linked, romantically […] Then he said yeah, he supposed they were, that was one way to put it, in a way. He paused. ‘Ish,’ he admitted. ‘Vaguely.’ (J. O'Connor, Cowboys & Indians, 1992 [OED])

Against the backdrop of the apparent crosscategoriality and multifunctionality of -ish, it will now be interesting to see how exactly these properties evolved in the course of English language history.

3 Data and methodology

Our study is based on data from a number of electronic corpora of prose texts covering the historical stages of English from Old English to the twentieth century (see table 2).

Table 2. Overview of the electronic corpora of texts used (* authors’ birth dates, m manuscript dates, p publication dates)

For Old English, we used the 3 million-word Dictionary of Old English Corpus (DOE, c.600–1150). As the ME period is not as well represented in electronic corpora as the other historical stages, data from this period were drawn from the electronic Middle English Dictionary (MED, m1175–1500).Footnote 10 For Early Modern English (EME) and the seventeenth century, we used the Early English Prose Fiction corpus (EEPF, *1460–1682) and Part 1 of the Eighteenth-Century Fiction corpus (ECF1, *1660–99) with a cumulative 15 million words. The data for the eighteenth century are extracted from part 2 of the Eighteenth-Century Fiction corpus (ECF2, *1700–52) and part 1 of the Nineteenth-Century Fiction corpus (NCF1, *1728–99), with a cumulative total of 17 million words. For the nineteenth century, we used part 2 of Nineteenth-Century Fiction (NCF2, *1800–69) with a total of 27 million words. Finally, the twentieth-century data are extracted from the written domain of the British National Corpus (wridom1, p1960–93). In this way, we were able to keep the factor genre constant at least from EME onwards, which allows for a higher degree of comparability:

From these corpora, we extracted all word-final occurrences of -ish (with variant spellings and inflectional endings for OE and ME). Hyphenated instances occur as of the seventeenth century and remain extremely scarce until the twentieth century; even the BNC contains only 33 instances.

In OE, the suffix generally appears as -isc [ɪʃ], occasionally -esc with a lowered vowel and no palatalization when followed by a back vowel (Campbell Reference Campbell1959: 155; Hogg Reference Hogg1992: 238), as in þa denescan ‘the Danes’, se mennesca ‘the human being’.Footnote 11 There are also a number of other spelling variants (-esh, -issc, -is, -iss, -sc, -ysc, -yssc), and we took meticulous care in searching the corpus to take all of these, with and without inflectional endings, into account.Footnote 12

Data from the MED, on the other hand, were retrieved by searching for entry forms (‘head words’) containing the string *ish*, and then looking up all the quotations provided under each relevant entry.Footnote 13

The output of the corpus searches was subsequently manually purged to exclude non-affixal -ish, as in the bases of nouns (e.g. OE fisc ‘fish’, ME blish ‘glimpse’, bishop) and the many ME and later verbs in -ish(en) from Old French -ir/Anglo-Norman -isse (cherishen, finish). While the inflectional variants of -ish formations, typical of the early periods, are included in our data (e.g. OE godspellesca, genitive plural of godspellisc ‘evangelical’), further deriviations with overt affixes are not, such as OE menniscness ‘humanity’, ME whitished(e) ‘whitishness’, lumpishli ‘awkwardly’ or EME assishness.

The relevant occurrences of -ish were analyzed and annotated for both the origin and the category of the base -ish attaches to (e.g. Germanic, Romance and N, A, VP, DP, respectively), the morphological makeup of the base (e.g. derivative, compound, phrasal), and the resultant category of the -ish form (if not adjectival).Footnote 14

A classification along these lines, in tandem with the quantification of all -ish formations in terms of type and token frequencies differentiated for the various base categories, allows us to gain an understanding of the diachronic development and productivity of -ish. The following section presents the results of our empirical study.

4 The diachronic development of -ish derivation in English language history

4.1 Old English

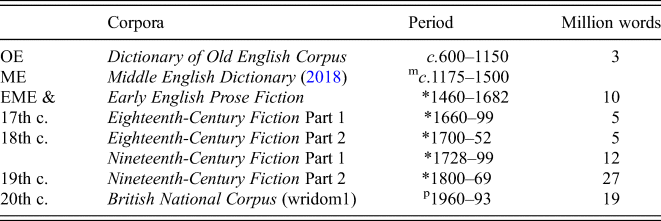

In our OE data, -ish derivatives amount to a total of 3,076 tokens, which constitute all in all 194 types. As figure 1 shows, all bases are nominal. They include both proper names and common nouns, and the latter can be simplex as well as compound. The proper names primarily denote geographical areas or ethnic groups (demonyms and ethnonyms, respectively).

Figure 1. Distribution of OE -isc derivatives across types

The lion's share of types (i.e. 74 percent) is represented by ethnonymic and demonymic formations, based on the names of countries, areas, cities and the like, and in some cases, persons (englisc ‘English’, lundenisc ‘from London’, madianitisc ‘Midianite; descendant of Midian’). This indeed is the well-known kind of -ish derivation, widespread in the Germanic languages, representing the original use of the affix.

Most forms with more than a few attestations are found both as adjectives and in nominalized uses representing either a person or persons of a certain nationality or origin, or their language (se denisca flota ‘the Danish fleet’, se denisca ‘the Dane’, on denisc ‘in Danish’). The fact that 55 of such forms identified in the corpus are hapax legomena should not be overinterpreted in the earliest period: it is hardly surprising that englisc ‘English’, denisc ‘Danish’, grecisc ‘Greek’, iudesic ‘Jewish’ and Nazarenisc ‘of Nazareth’ are highly frequent, whereas e.g. amalechitisc ‘Amalecite’, ethiopisc ‘Ethiopian’ and nyceanisc ‘of Nycene’ are each recorded only once. This merely reflects the topics dealt with in the preserved records and has little to do with any characteristics of the language at a stage when -ish had little competition as a marker of geographical or ethnic origin.

Closely related to this kind of -ish derivation is the one based on proper nouns, which amounts to six types in total and which results in adjectives denoting either a family relation (herodiasc ‘Herodian, [daughter] of Herodias’, pontisc ‘Pontian, of the Pontius family’) or an origin relating to the person in question (arrianisc ‘Arian, adhering to the doctrine of Arius of Alexandria’, davidisc ‘by David’).

The category of greatest interest, in view of -ish uses at later stages of the language, are the forms derived from nominal bases. In our data, these represent 32 types/641 tokens. With 462 tokens, mennisc ‘human’ is by far the most frequent type. As shown by the consistently mutated form of the base (spelt menn-, occasionally mænn-), this is a prehistoric formation, and richly attested also in nominalized uses (‘man’, ‘people’). Interestingly enough, i-mutation can still be found in a wide array of -ish derivatives, and also with bases of Latin origin; see, e.g., milisc ‘honeyed, sweetened with honey’, derived from Latin mel(l) ‘honey’. As can be expected, the members of the nominal category are primarily based on simplex common nouns (e.g. ceorlisc ‘churlisc’ < ceorl ‘churl’, eotenisc ‘made by a giant’ < eoten ‘giant’), though compounds are also attested (e.g. dun-lendisc ‘hilly’ < dun-land ‘hilly country’, god-spellisc ‘evangelical’ < god-spell ‘gospel’).

As for the etymological origin of the base, we find that the suffix -ish, as expected, primarily attaches to Germanic roots, but also to roots of Latin origin (e.g. puerisc ‘boyish’ < Latin puer), or Graeco-Latin bases (e.g. deóflíc ‘devilish’ < Greek διάβολος via Latin diabolus and early Germanic). Several of the base forms from Latin appear to be relatively well-established loans in OE, such as gimm ‘jewel’ (the base for gimmisc ‘jewelled, set with gems’) from Lat. gemma, laur ‘laurel’ (> laurisc ‘of laurel’) from Lat. laurus, and possibly also cristalla (> cristallisc ‘of crystal’) from Lat. crystallum.

All in all, then, there is evidence that already at this stage, English -ish was less particular in its choice of partners than many of the current adjective-forming suffixes, which, as noted above, more faithfully select bases of either English (i.e. Germanic) or Romance origin. In this respect, as Campbell (Reference Campbell1959: 219) points out, -isc, along with the agentive suffix -ere and the infinitival ending -ian, is more prone than other affixes to attach to foreign bases.

In a nutshell, although the attested OE ‘inventory’ of -ish derivatives is dominated by ethnonymic bases (74 percent), the remaining 26 percent foreshadow the variance of -ish derivatives as witnessed by hybrid formations and -ish suffixation to morphologically complex bases.

4.2 Middle English

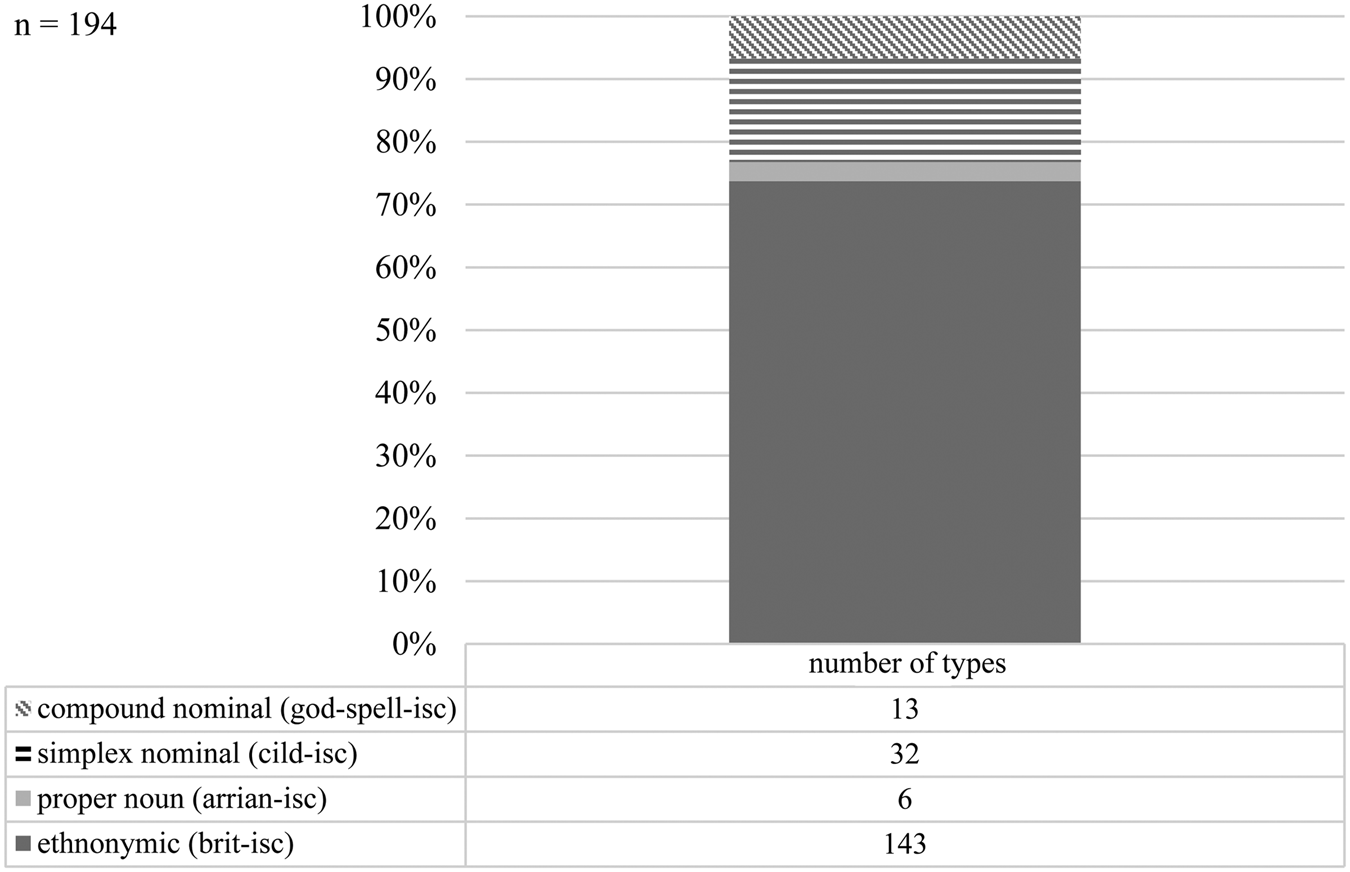

How did the word-formation pattern of -ish derivation change after OE times? Figure 2 offers various insights: adjectives established themselves as a fully fledged new word category available for -ish derivation, verbs also appeared on the scene, and concomitantly, the overall distributions changed considerably. It needs to be emphasized, though, that the statistics are to be taken with a pinch of salt: due to the nature of the database, the numbers are admittedly neither directly comparable to nor as reliable as the frequencies reported for OE or the post-ME eras. Therefore, in the following section on ME -ish derivatives, we will restrict our discussion to type frequencies as evidenced in the data at hand, which nonetheless allows us to draw conclusions as for the further development of -ish derivation.

Figure 2. Distribution of ME -ish derivatives across types

The data extraction revealed a total of 191 types, distributed over five different base categories: for nominal bases, we again differentiated between simplex and compound nouns, and as it is commonly argued that color adjectives are the entry route for adjectival bases in general (Marchand Reference Marchand1969: 305), we distinguished between color and common adjectives. As can be seen at first glance, the share of -ish types across word categories has changed enormously in the transition from OE to ME, with nominal bases now having overtaken the group of ethnonyms. From clear winner downgraded to runner-up, ethnonymic formations take second place in ME with 37 extracted types (19 percent), not too far ahead of the newcomer, i.e. the deadjectival type. The data for ethnonymic formations corroborate Dalton-Puffer's (Reference Dalton-Puffer1996) and Ciszek's (Reference Ciszek2012) observation that -ish loses ground in this domain as the nationality-denoting function is nowadays largely expressed by other suffixes that were added to the derivational system in ME, primarily -ian, -an and -ite. Nationality-denoting -ish, the only Germanic suffix used with ethnonyms (cf. Dixon Reference Dixon2014: 268), is by and large only used with those formations that have existed since OE but has ceased to be available for creating new ethnonymic adjectives.Footnote 15

Similarly, proper noun bases decline drastically in ME, with just two types attested in our data, namely Magdalenish and Pilatus Pontiuisce. These formations, which are probably remnants from OE Bible translations, bear a locational/relational sense (‘from Magdala’, ‘belonging to the Pontius family’) that would nowadays be absent with -ish forms derived from proper nouns. As shown below, proper noun bases disappeared completely for some time before they experienced a comeback in the nineteenth century.

A closer look at the 109 simplex noun bases reveals that this type of denominal -ish forms did indeed thrive in ME. In this respect, the data at hand do not confirm Dalton-Puffer's (Reference Dalton-Puffer1996: 173) intuition that with ‘common noun derivatives being rare in Old English … our data would indicate that the same was the case in Middle English.’ While a great deal of the OE ethnonymic formations did not survive into the ME period (e.g. affricanisc, bulgarisc and grecisc became obsolete), the vast majority of denominal ones did – and apart from that, a great number of new coinages can be found, with an observable extension of the nominal class. Whereas most OE formations denoted animate beings, ME formations go beyond persons (e.g. foolish, knavish, thievish) and animals (e.g. doggish, foxish, swinish) in that they also comprise a wide array of inanimate entities denoting substances, materials or shapes/appearances:

(16) When [blood] is o þe vesy it is mare lumpryssh & clumpryssh & cruddyssh & spottyssh … (a.1425) (MED)

‘When blood is in the urinary bladder, it is more lumprish & clumprish & cruddish & spottish …’

Interestingly enough, for many of the -ish derivatives we also find variant forms in -y/-i, e.g. cruddi vs cruddyssh in (16) or cloudi vs clowdyssh, which is indicative of a system in flux, with functionally equivalent suffixes competing. In this regard, it is also no surprise that very many attested ME -ish forms have later on been replaced by -ly derivatives, e.g. lifish vs lively, daiish vs daily, hevenish vs heavenly.

At the same time, we can observe lexicalization processes setting in, with -ish derivatives gaining an idiosyncratic meaning in some cases. A prime example is childish, which used to be perfectly interpretable as ‘childlike’ in the associative sense and which has now come to be negatively connotated as ‘not befitting maturity’ (OED); the pejorative sense has been attested since 1405. As for the claim that most denominal -ish formations are pejorative, which according to Marchand (Reference Marchand1969: 305) originates from OE nouns such as ceorlisc ‘churlish’ and hæþenisc ‘heathen’, there is indeed a conspicuous number of inherently negative bases (cf. fool, thief, knave). It remains doubtful, however, whether this suffices to claim that this ‘derogatory shade of meaning’ (Marchand Reference Marchand1969: 305) carries over to any person-denoting -ish derivatives (even though this might be appropriate for animal-denoting formations, as Malkiel (Reference Malkiel1977) claims in his investigation of the competition between -ish and -y with respect to zoonyms).

Moving on to deadjectival -ish formations, which make up the third largest group of base categories at 13 percent, we see an innovation that paves the way for the approximative sense ‘nearing, but not exactly X’ (Marchand Reference Marchand1969: 306), commonly associated with -ish formations derived from adjectives. The path of development that leads to the rise of this novel function is closely tied to the by then well-established associative sense of similitude; as Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Lieber and Plag2013: 313) put it,

the first meaning is derived by inference from the second. If we say something is similar to dull, baptismal, lunar, or modern, the inference is drawn that we cannot mean exactly dull, baptismal, lunar, or modern but rather must mean something not exactly the same as those qualities, that is, approximating those qualities.

It is often assumed that color adjectives are the forerunners in this development, dragging along all other kinds of adjectives (i.e. those that we subsumed under the label ‘common adjectives’) only later with a considerable delay. The claim is tentatively made in the OED entry for the suffix -ish, and reiterated in more concrete terms by Marchand (Reference Marchand1969), who specifies that ‘from its use with adjectives denoting color the suffix was extended to other adjectives with the same nuance of approximation (chiefly 16th century and later)’ (Reference Marchand1969: 306). This claim is definitely not corroborated by our data, which show that -ish formations derived from color adjectives (amounting to 11 types) were used at approximately the same time as others derived from common adjectives (26 types). The earliest formations based on a color adjective are whitish (1379), yelwish (1379) and reddish (1392), for those based on common adjectives, the earliest attestations are fattish (1369), palish (a.1398) and sourish (a.1398).

We might still object that the approximative sense is not as firmly established with common adjectives as it is with color adjectives. Indeed, there are some attestations where -ish seems to be pleonastic. For instance, sorwefullish is simply given as a variant for sorweful in the respective MED entry, and for adjectives such as palish and swolnish it might be argued that -ish rather serves to mark weakly entrenched adjectives more unequivocally as such, the first one being a new French loan, the second being an adjectivally used past participle. However, the following medical guideline from Liber uricrisiarum (a.1425) (Jasin Reference Jasin1983) can be taken as an early metalinguistic comment and evidence for the prevalence of the approximative sense with at least some adjectives such as thin or thick:

(17) For to wys how þis terme “thynnyssh” sall be takyn, undyrstand þat þare is difference betwen “thyn” and “thynnyssh”: “Thyn” […] is when þe uryn is fullyk thynne […] “thynnyssh”, when it is a party thyn or ellys menely thyn. (MED)

‘In order to know how this term “thinnish” shall be used, understand that there is a difference between “thin” and “thinnish”: “thin” is when the urine is fully thin […] “thinnish”, when it is partially thin or else slightly thin.’

Interestingly, nowadays such deadjectival formations are assumed to predominantly occur in journalistic prose and fiction (because they are perceived to be somewhat jocular); some of the first attestations, however, are found in medical texts.

Apart from deadjectival formations, deverbal ones emerge as another newcomer – albeit, with merely three attested types, a feeble one (and also one not destined to prosper in later periods). As Dixon (Reference Dixon2014: 293) remarks, -ish is nowadays represented ‘with a small number of Germanic verbs’ (e.g. snappish, ticklish); the earliest attestations of this type, however, are with Romance verbs, namely errish (< err), servish (< serve) and boudish (< from Old French bouder ‘sulk’ or ‘swell or protrude the lip’ (Godefroy Reference Godefroy1881: 349, s.v. bouder)). All of these early deverbal derivatives became obsolete and are not even recorded in the OED. The fact that -ish never quite succeeded in establishing itself with verbal bases is probably related to its competition with -y, which did indeed successfully conquer this domain (see Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Lieber and Plag2013: 306).

To wrap up the ME state of affairs, -ish combines with an extended inventory of bases, now comprising ethnonymic bases, proper, simplex and compound nouns, common adjectives and color adjectives, as well as verbs. The share of -ish derivatives from ethnonymic bases and simplex nouns has changed dramatically, with the former recessing and the latter booming. Also, the diversification and spread of -ish derivatives from adjectival bases is considerable, with color adjectives and common adjectives both well represented. It does indeed seem as if -ish found ‘a new purpose in life’, as Dalton-Puffer (Reference Dalton-Puffer1996: 198) puts it, on its way to turning into ‘a popular Similitudinal suffix in Modern English times’.

4.3 Post-Middle English: from Early Modern English to Present-day English

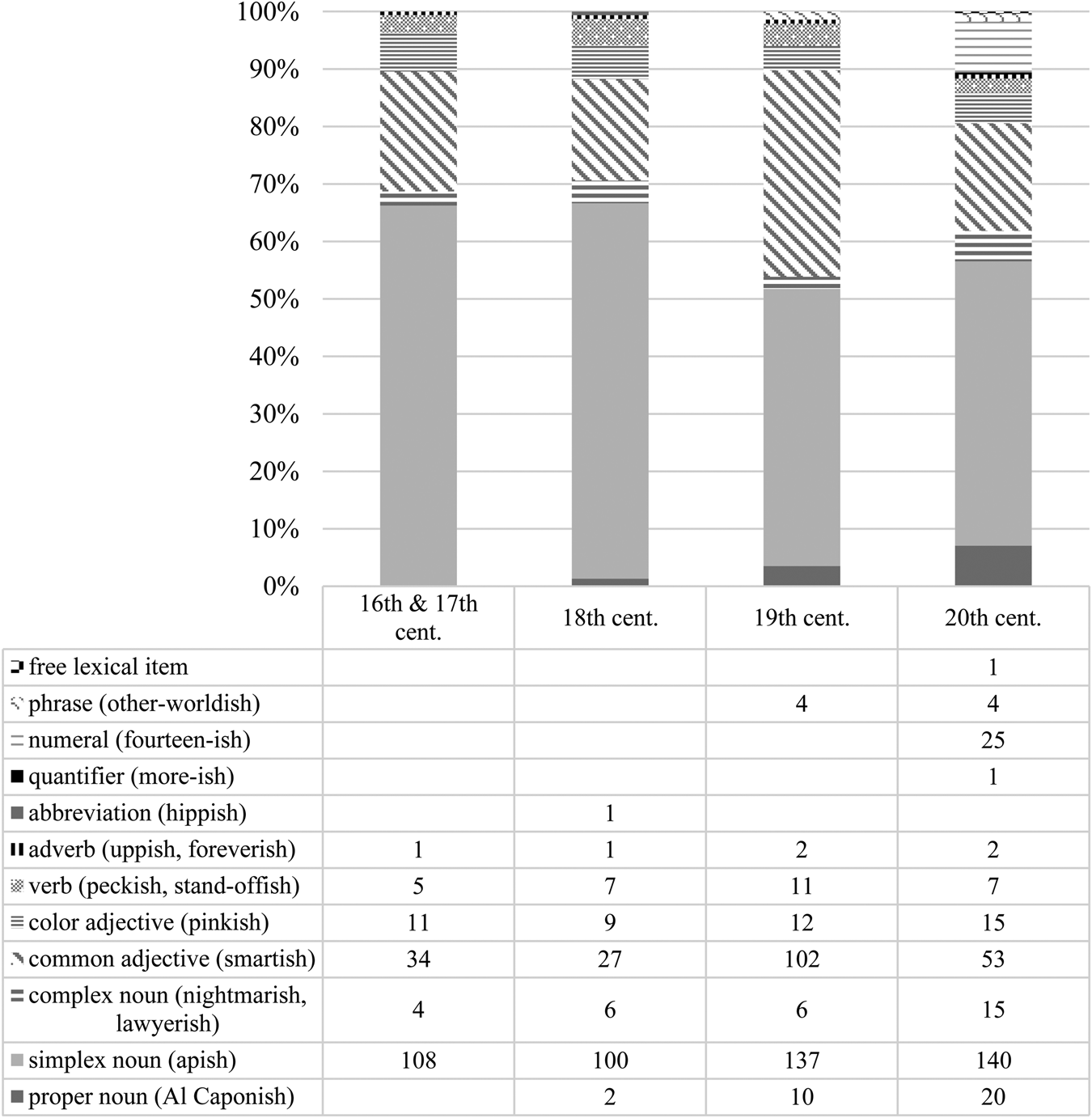

This section outlines the development after the ME era, i.e. from the sixteenth century to PDE. Figure 3 displays the distribution of -ish derivatives over various base categories. We see that the picture becomes increasingly more varied as we approach the twentieth century, indicating that the pattern of -ish derivation is in full bloom. It needs to be noted that, at this point, we decided to eliminate any nationality-denoting -ish derivatives from the tally. The reason for this is basically twofold: on the one hand, the type–token ratios reported on in section 5 would not have been a meaningful rate if we had kept the large numbers of ethnonymic adjectives in; and on the other hand, these large numbers would not have indicated productivity in any way because, as elaborated in section 4.2, -ish ceased to be available for creating ethnonymic adjectives once it had lost out to its Romance rivals.

Figure 3. Distribution of -ish derivatives across types from the sixteenth to the twentieth century

Overall, there is a sharp increase in -ish types already as of EME, with a true explosion in types as of the twentieth century. Still, the base categories that have been well established since ME continue to play a significant role, with denominal formations constituting the most dominant class across the board, and deadjectival formations defending their second place. The nineteenth century is particularly interesting in that deadjectival formations are almost as well represented type-wise as denominal ones, when, for the first time, their shares differ from each other by a mere 12 percent. Denominal formations from complex nouns continue to be comparatively sparse, even though there is some new input from derived nouns as of the eighteenth century (lawyerish [ECF2]). Deverbal derivatives, which made but a feeble entrance in ME, never gained a strong footing, with just a small number of them becoming well established, such as ticklish (EEPF), snappish (ECF2) or peckish (BNC), whereas other novel deverbal formations such as severish < sever (NCF1) or stiflish < stifle (NCF2) did not survive the nineteenth century:

Apart from the well-established base categories, additional word classes start to allow for -ish suffixation, i.e. adverbs (uppish [EEPF], offish [NCF2], forever-ish [BNC]), quantifiers (more-ish [BNC])Footnote 16 and most conspicuously, numerals (fortyfivish [BNC]), which constitute an innovation of the twentieth century that serves to consolidate the approximative sense of -ish.

A word category that experiences a comeback as of the eighteenth century is proper nouns. After they ceased to be frequently used in ME, they completely disappear from the picture in EME, until they resurface in Late Modern English, first with just two occurrences in our corpora (Quakerish [NCF1], tartufish [ECF2]). Crucially, though, their usage is entirely different to the one in OE and ME, i.e. -ish derivatives from proper nouns are no longer relational or ethnonymic (cf. davidisc ‘by David’, Magdalenish ‘from Magdala’), but now exclusively express the associative sense of similitude. This can nicely be illustrated by means of Quakerish, an -ish form derived from the name of a religious group:

(18) The consequence of this was, that at a very early hour, […] all who considered themselves as belonging to that class, were seen arriving in their very becoming sad-coloured suits, with their smooth braided tresses, and Quakerish bonnets and caps. (1837, F. Trollope, The Vicar of Wrexhill [NCF2])

The group of people arriving in the small hours, however, do not belong to the Quakers, which becomes clear from an earlier passage; indeed, the word Quaker is not used elsewhere in the entire novel. In other words, the bonnets and caps only resemble those worn by members of the Quaker community, but they do not indicate a direct relation. After the first reappearances in the eighteenth century, proper noun bases become more frequent in the next two centuries, with the associative similarity sense firmly taking hold as the following examples from the twentieth century demonstrate:

(19)

(a) a handsome chap in a sinister sort of way, Al Caponish with a dash of Dracula

(b) a huge Swansea-style computer keeping a Big Brotherish eye on every car

Apart from the extension of base categories, there is also a new degree of complexity added to the picture, when -ish starts to attach to the first phrasal bases from the eighteenth century onwards ((20) is taken from the NCF2, (21) from the BNC):

(20)

(a) Hale's was some temporary or fanciful [[fine-lady]NP ish]A indisposition …

(b) for Miss Coe answered questions with an [[old-maid]NP ish]A scream

(21)

(a) Aware that the dress had a fey, [[other-world]NP ish]A air …

(b) It was still dark, [[middle-of-the-night]NP ish]A, but I'd scribble something …

In all of these cases, the scope of -ish extends over the entire phrase: in fine-ladyish, the host of the affix is not just the noun lady but the whole noun phrase fine lady. While -ish in (20)–(21) displays clitic-like characteristics, such as attaching to phrases, it still derives adjectives. A further step in the development of -ish is the clitic stage at which -ish combines with any kind of phrasal base without inducing category change ((22a) from the BNC, (22b) from Kuzmack Reference Kuzmack2007: 5f.):

(22)

(a) and the [[forever]AdvP -ish]AdvP trickly sound of her high giggle

(b) So, yeah, we're [[friends]NP -ish]NP.

For the purpose of compatibility with the literature discussed in section 6, we refer to both -ish in (20)–(21) and (22) as clitic. Cliticization may have paved the way for the development of ish as a free lexical item in the twentieth century:

(23) You must try to remember that some people are normal. Ish. (BNC)

One characteristic trademark of free lexical ish, which seems to abound especially in spoken registers, is that it may modify a previous conversational contribution, thus functioning like an epistemic marker or hedging device (see, for example, Traugott & Trousdale Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 236f.). We return to this in section 6.

All in all, the developments during the five centuries after the ME period contribute essentially to -ish obtaining the extraordinary characteristics commonly attributed to this suffix in PDE, due to a concomitant gain of new base categories and a semantic bifurcation of the associative sense vis-à-vis the approximative sense.

5 Assessing the productivity of -ish diachronically

The developments in -ish derivatives as surveyed in the previous section suggest an increase in productivity, in the sense of both availability and profitability (Kastovsky Reference Kastovsky1986: 586; Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Lieber and Plag2013: 32ff., passim). On the one hand, the licensing of ever more base categories expanded the scope of the word-formation rule, thus enhancing the availability of -ish as an adjective-deriving element, and on the other hand, the actual implementation of this rule is reflected in ever new coinages, thus underscoring the high profitability of this affix.

In order to assess the productivity of -ish diachronically, we zoom in on the eras after ME, as the corpus material of these periods can shed light on this question more reliably, with the factor genre (i.e. prose fiction) kept in check.

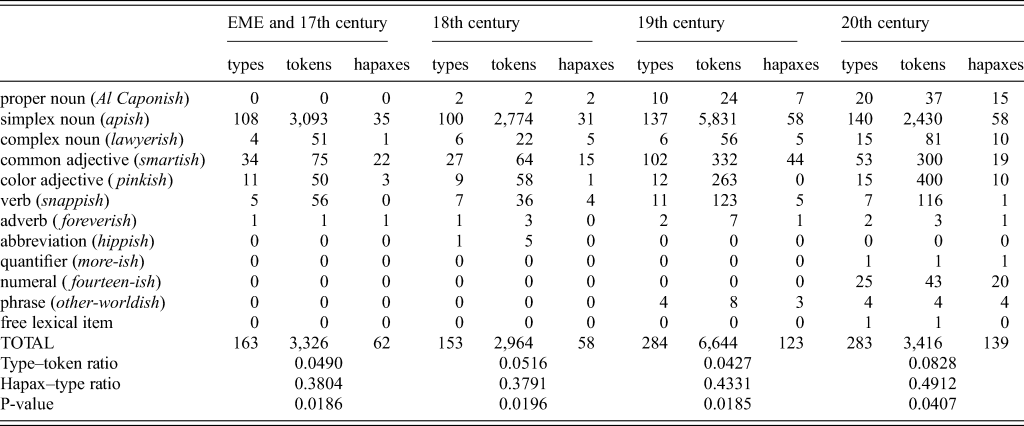

For the timespan from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, table 3 summarizes the numbers of types and tokens for each base category available for -ish suffixation, with the type frequencies giving a first impression of the realized productivity or ‘extent of use’ (Baayen Reference Baayen1993). Additionally, the table contains the number of hapax legomena for the various base categories; these one-time attestations are of particular interest as they are indicative of the availability of a given suffix for coining novel words – even though hapax legomena are not fully identical to neologisms (see Plag Reference Plag1999: 26ff.; Plag et al. Reference Plag, Dalton-Puffer and Baayen1999: 215f.; Baayen & Renouf Reference Baayen and Renouf1996: 74). The last three rows provide the statistics for type–token and hapax–type ratios as well as narrow productivity scores (so-called P-scores) for each era.

Table 3. Summary of -ish derivatives

While the type–token ratio per se is not a direct measurement of productivity, it offers tentative insight into how diverse the pattern of -ish derivation is, weighing the number of derivatives (from high-frequency ones to low-frequency ones) against the overall number of types. In contrast, the hapax–type ratio provides information on the share of hapaxes within the overall number of types; while in EME, 38 percent of all types are attested only once, this share has risen to almost 50 percent in the BNC data, thus suggesting a surge in productivity for the twentieth century, which also shows in the considerably higher P-score. This hapax-based productivity value, which is computed by dividing the number of hapaxes by the total number of tokens, measures ‘the probability of coming across new, unobserved types’ (Plag et al. Reference Plag, Dalton-Puffer and Baayen1999: 215; see also Plag Reference Plag2003: 56–57; Hilpert Reference Hilpert2013: 128–129); in the case of the twentieth-century data, this means that the likelihood of encountering a novel -ish derivative is 4 percent, or, put differently, every twenty-fifth -ish formation is a hapax.Footnote 17

However, as P-scores are highly susceptible to corpus size, a comparison of the different values across time proves to be problematic if taken at face value; after all, the underlying corpus sizes vary considerably, with the nineteenth-century corpus being one-and-a-half times larger than the ones from the century before and after. Nonetheless, the narrow productivity score for the twentieth-century data is markedly higher than those for the other periods, which points to a massive increase in productivity; indeed, it is more than twice as high in the twentieth century as for the period 1500–1700. Actually, a direct comparison of the contemporary data to the EME data is permissible insofar as they display roughly the same number of tokens, thus rendering an almost identical value in the denominator for the calculation of the respective P-score.Footnote 18 Also, it is remarkable that the twentieth century displays such a high P-score, despite of the comparatively smaller corpus size; and undoubtedly, the overall hapax–type ratio for the twentieth century as against the nineteenth century points to quite an impressive growth in contemporary novel -ish formations, a statistically sound conclusion due to practically the same number of types in both periods considered.

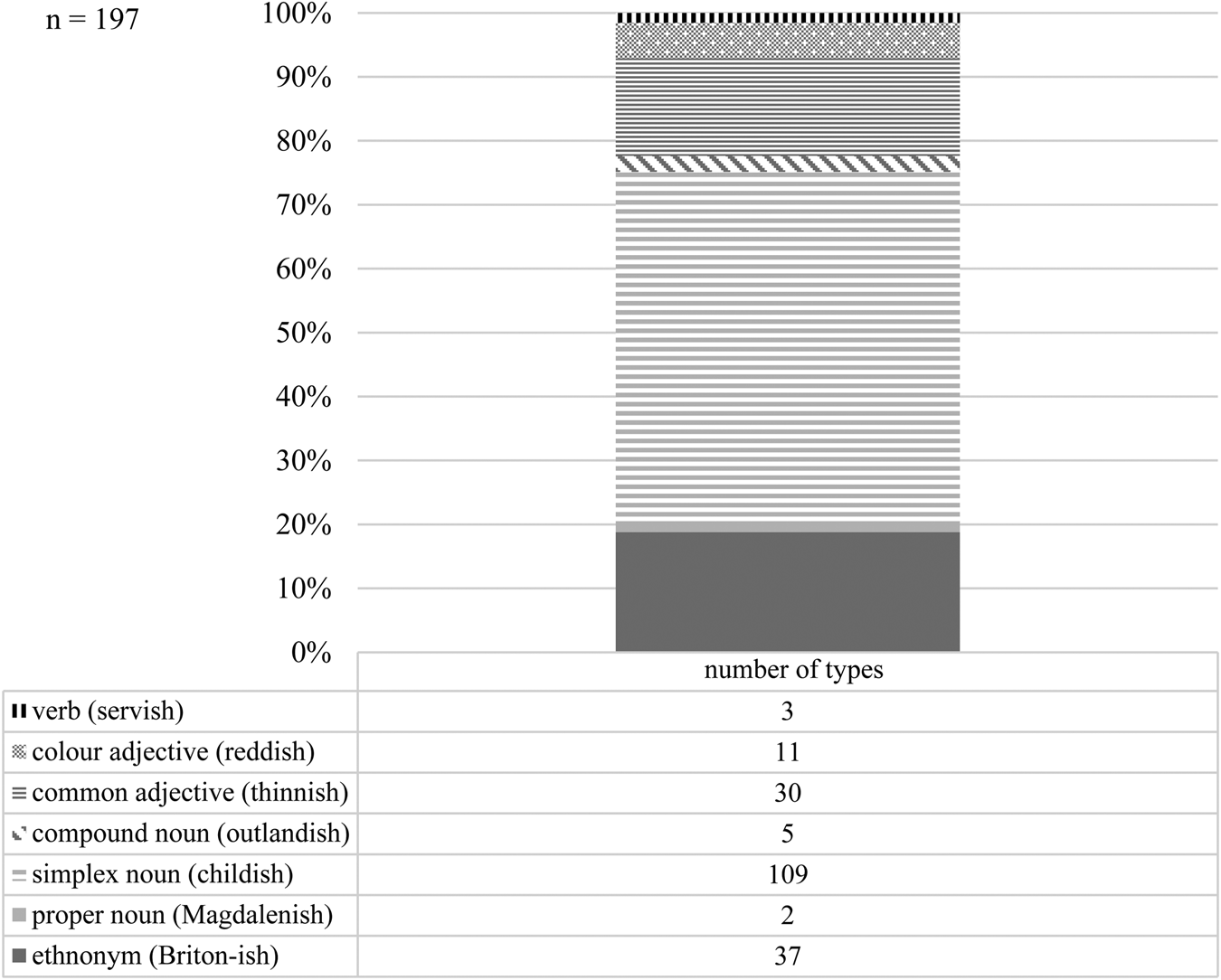

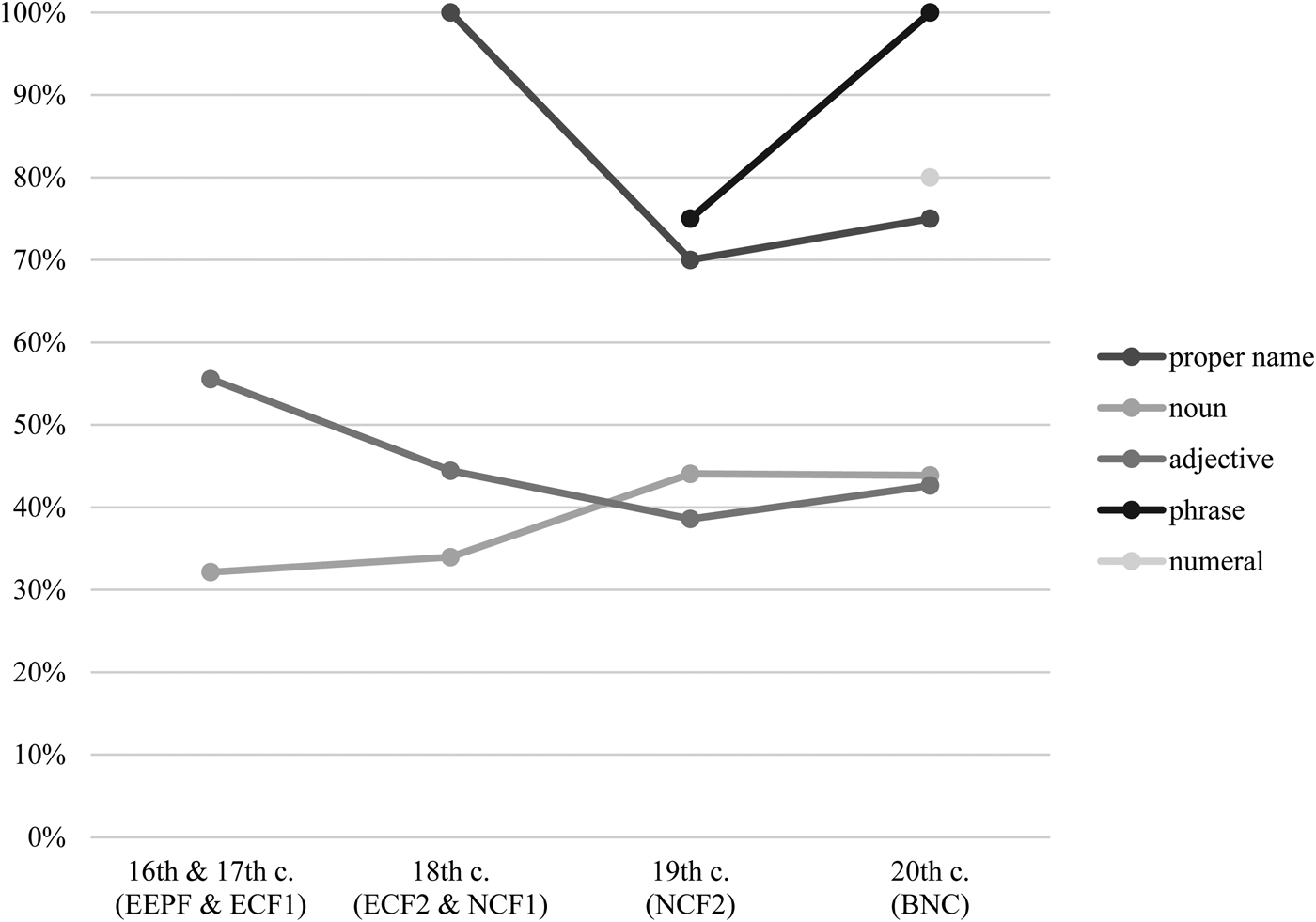

Zooming in on hapaxes in more detail, figure 4 tracks the diachronic trajectory of the hapax–type ratio, by displaying the share of hapaxes within the total number of types per base category. Note that for the following discussion we only considered those base categories for which a minimum of three hapaxes are attested at some point, thus excluding minor size categories such as verbs, adverbs or quantifiers. To provide a clearer overview of developing tendencies, the nominal type has not been differentiated for degrees of complexity and thus comprises both simplex and complex noun derivatives. Common adjectives and color adjectives have also been lumped together.

Figure 4. Hapax–type ratios from the sixteenth to the twentieth century according to base type

Across the board, denominal -ish formations prove to be continuously productive in that over a third of all denominal types are hapax formations, with an observable increase towards the twentieth century. Deadjectival types witness a remarkable hapax–type ratio in the initial period with over 50 percent of all types being hapaxes, yet the share decreases over time, until the score for the deadjectival type is on a par with that of the denominal type. As it seems, once adjectival bases became available from ME onwards, deadjectival and denominal -ish formations are equally productive, which manifests itself in stable hapax–type ratios. Apart from these base categories, which witness a fair degree of productivity across all centuries, the pattern of -ish derivation displays considerable innovations in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century data, with the re-emergence of proper noun bases and the addition of new types, i.e. phrasal bases in the nineteenth century and eventually numeral bases in the twentieth century. Indeed, in the twentieth-century data, more than two-thirds of all types of numeral and proper noun bases are hapaxes, and all of the four attested -ish-derived phrases are nonce-formations. It might not come as a surprise that all of these score quite highly in terms of hapax–type ratios; after all, the number of proper names, phrases and numerals is unlimited, which allows for an unrestricted possibility to come up with ad hoc formations.

To conclude, what our data show is an increase in variability, productivity and creativity, as witnessed by ad hoc formations which, by definition, are less rule-governed and thus less predictable: -ish types gain in variability as more and more base categories combine with the suffix, starting with nominal bases and then gradually spreading to all kinds of bases in differing complexity. In this respect, -ish is a fine illustration of the assumption that ‘the closer an affix is to being fully productive on non-compounds and phrases, the more likely it is to accept compounds and phrases as well’ (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Lieber and Plag2013: 515). Nominal and adjectival bases prove to be the most productive candidates, while later additions to the -ish paradigm such as phrases, numerals and revived proper nouns may be overall less frequent type-wise but display a high degree of creativity as witnessed in ad hoc formations hapax-wise.

Against this backdrop, it will now be interesting to see to what extent the empirically investigated development of -ish derivatives correlates with morphological and morphosyntactic theorizing.

6 (Re)Assessing theory through empirical evidence

In recent years, the diachronic trajectory of -ish formations has received ample attention from researchers in inverse grammaticalization theory and constructionalization theory. Also, from a synchronic perspective, the inventory of -ish formations has caught the attention of generative linguists. Employing -ish as a touchstone for theoretical claims and considerations, the various approaches differ not only in their aims and theoretical orientation, but also in coverage and focus. While inverse grammaticalization theory focuses on the development of -ish along a directed trajectory and thus, tendentially, more on the endpoint of the process, constructionalization theory focuses on the various shifts and changes that constitute diachronic change. Conversely, generative accounts of -ish formations focus on snapshots in the trajectory without (necessarily) taking the overall trajectory into consideration. In the following, we are going to revisit three main strands of theorizing and reassess the claims made in the literature in light of our empirical data. Thus, our empirical study not only serves as a Litmus test for the theoretical claims put forward in inverse grammaticalization theory (section 6.1), constructionalization theory (section 6.2) and Distributed Morphology (section 6.3). It also contributes to a more fine-grained and hence more varied picture of the diachrony of -ish.

6.1 Inverse grammaticalization theory

In the first strand, the diachronic journey of -ish from derivational suffix to clitic and ultimately to free lexical item is taken to be indicative of an inverse grammaticalization process. Both Kuzmack (Reference Kuzmack2007) and Norde (Reference Norde2009) focus on the inverse grammaticalization cline that -ish has been moving along since OE, with Kuzmack (Reference Kuzmack2007) referring to the process as antigrammaticalization and Norde (Reference Norde2009) as degrammaticalization.Footnote 19 Labels aside, both Kuzmack (Reference Kuzmack2007) and Norde (Reference Norde2009) argue that the development of -ish from a derivational suffix to ultimately a free lexical item is accompanied by resemantification, i.e. an increase in semantic content, with the suffix developing from a purely formal adjectivizer with a nationality/ethnicity/origin-denoting sense (OE egiptisc ‘Egyptian’, cristallisce ‘made of crystal’) into a derivational suffix expressing association/comparison (OE hæðenisc ‘heathen’, ME shepishse ‘sheep-like’) and later also approximation/qualification (easyish ‘somewhat easy’, nowish ‘vaguely now’). The three main types may be labeled ish 1, ish 2, and ish 3 ((24) adapted from Kuzmack Reference Kuzmack2007: 1):

(24) ish 1 expressing nationality/ethnicity/origin, i.e. ‘of X origin, made of X’

ish 2 expressing association/comparison, i.e. ‘of the character of X, like X’

ish 3 expressing approximation/qualification, i.e. ‘somewhat X, vaguely X’

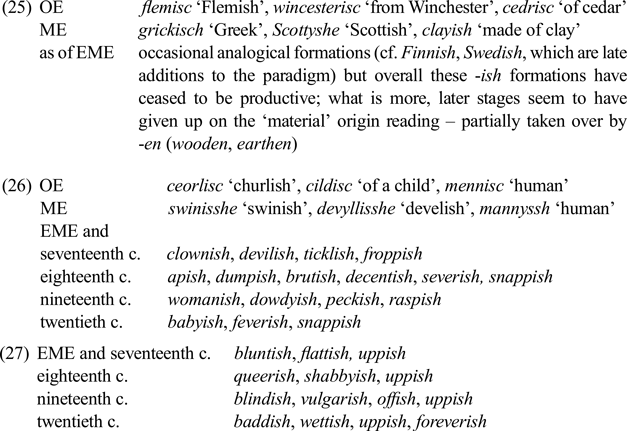

Our data corroborate Kuzmack's (Reference Kuzmack2007) claim that the three senses of -ish both overlap historically and persist into PDE, with ish 1 and ish 2 being attested since OE, the comparative sense of ish 2 developing in ME, and ish 3 being a later addition. The development of ish 2 and ish 3 coincides with a loosening of selectional restrictions. While ish 1 is restricted to selecting nominal bases (25), ish 2 and ish 3 gradually allow for a categorially varied array of bases. According to Kuzmack (Reference Kuzmack2007: 4f.), ish 2 derives adjectives from nouns and, as our data show, also from verbs (26), and ish 3 derives adjectives from adjectives and adverbs (27). These observations are borne out with the reservation that the few de-adverbial -ish derivatives in our data, notably offish, uppish and foreverish, all instantiate ish 3 (see (27)):

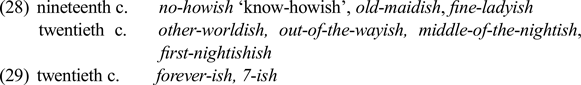

While ish 1 ceases to be productive, ish 2 and ish 3 see an increase in productivity, with ish 2 being more productive than ish 3 (cf. Kuzmack Reference Kuzmack2007: 2; Traugott & Trousdale Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 235ff.; see below for discussion). Not only are their selectional restrictions loosened with respect to the category of the base, they are also loosened with respect to the format of the base: in addition to combining with X0 elements, ish 2 and ish 3, as of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, respectively, also combine with phrasal elements. Kuzmack (Reference Kuzmack2007) analyzes occurrences of ish 2 as in (28) and ish 3 as in (29) as clitics:

Note, however, that ish 2 in (30), despite taking scope over the phrases it combines with, shares with the derivational -ish the property of deriving adjectives, whereas ish 3 in (31) does not affect the category of its host ((31a, b) from the BNC, (31c, d) from Kuzmack Reference Kuzmack2007: 5f.). Note also that, while the scope of -ish in (31a) is restricted to the adverb forever, the scope of -ish in (31b–d) could be either the Num(eral)P (7),Footnote 20 the NP (friends) or the PP (on their way), respectively, or the containing constituent:

(30)

(a) for Miss Coe answered questions with an old-maidish scream (NCF2)

(b) The programme had some good out-of-the-wayish music: (BNC)

(31)

(a) her back slender and white, and the forever-ish trickly sound of her high giggle

(b) Probably arrive about 7-ish, if that's OK.

(c) So, yeah, we're friends-ish.

(d) Happier still, Jessica, Brian and Erik are [on their way]…ish…

According to Kuzmack (Reference Kuzmack2007), the low degree of selection of ish 3 (in tandem with phonological strengthening) may have facilitated the later development of the clitic variant of ish 3 as in (31) and ultimately the development of the free lexical item ish 3 in (32) (adapted from Kuzmack Reference Kuzmack2007: 6; see also (23) above):

(32)

(a) Can you swim well? Ish.

(b) Is everyone excited? I am – ish.

All instances of the clitic variant of ish 3 in our data involve adverbs and numerals as host categories (31a, b); the free lexical item ish 3 occurs only once (see (23) above). The scarcity of these elements in our data may be due to the relatively early completion date of the BNC, 1993, rather than to accidental gaps. In other words, the development of both the clitic variant and the free lexical item may still only be incipient in the early 1990s. The variety examined, British English, may be a contributing factor, as may the fact that our investigation is limited to the written domain of the BNC, while ish 3 is still primarily a feature of informal, spoken language (see also Plag et al. Reference Plag, Dalton-Puffer and Baayen1999: 220) and, of course, written representations of such style.

All in all, the trajectory of change depicted in inverse grammaticalization theory is corroborated by our empirical study.

6.2 Constructionalization theory

A second strand of theorizing concerned with the diachronic trajectory of -ish formations involves proponents of constructionalization theory. In this framework, diachronic processes of constructionalization are conceived of as resulting in new form–meaning pairings, with the rise of new meanings being concomitant with changes in syntax or morphology and ‘accompanied by changes in degree of schematicity, productivity, and compositionality’ (Traugott & Trousdale Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 22).Footnote 21 Taking the typology of historically overlapping and persisting senses of -ish in (24) as a point of departure, Traugott & Trousdale (Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 234) suggest subsuming semantically similar ish 1 and ish 2 under the general OE word-formation schema in (33), with two specific subschemas covering ish 1 (33a) and ish 2 (33b).

(33) is a descriptive formalization of both the selectional properties of affixal ish 1 and ish 2 and the interpretation of the derived adjective: both ish 1 and ish 2 select nouns with the noun denoting either an ethnic group or some kind of entity; the property the derived adjective expresses depends on the denotational properties of the noun selected:

(33) OE ish schema: [[Ni.isc]Aj ↔ [having character of semi] property]j]

(a) Ethnic ish (ish 1):

[[Ni.isc]Aj↔ having character of ethnic groupi] property]j]

(b) Associative ish (ish 2):

[[Ni.isc]Aj↔ [having character of entityi] property]j]

According to Traugott & Trousdale (Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 234), the Ethnic ish subschema (33a) became recessive in late ME,Footnote 22 until it ultimately ceased to be productive. Our data corroborate the stipulated development of ish 1, both for the narrow origin interpretation, i.e. ethnic group, as well as for the wider interpretation including provenance in general, e.g. OE aquinensisc ‘from the town Aquino’, and material origin/substance, e.g. OE cedrisc ‘of cedar’ or ME clayish ‘made of clay’. Surviving ish 1-derivatives, e.g. English, Jewish, outlandish, are lexicalized with individual items displaying varying degrees of transparency, e.g. British (related to Britain) vs Cornish (related to Cornwall). Productive formations, such as Londonish (34), typically instantiate the Associative ish subschema (33b), which, after having laid somewhat dormant in OE and ME, gained ground and proliferated in EME:Footnote 23

(34) He was strolling down the steep narrow street towards the sea, his hands deep in his pockets and his shirt open at the throat, very pale and Londonish, looking about him with the fond, proprietorial air of an Englishman returning to a favourite spot abroad. (BNC)

Following Marchand (Reference Marchand1969: 305), Traugott & Trousdale (Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 234) point out that many of the surviving early -ish derivatives of the type in (33b) have undergone pejoration. The semantic shift from ‘typical of N’ to ‘typical of and with the negative characteristics of N’, e.g. childish ‘childlike’ > ‘childish’, indicates constructional change, i.e. a change within an existing construction rather than the emergence of a new construction. For Traugott & Trousdale (Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 235) both the loosening of the selectional restrictions of Associative ish 2 (33b) as well as the change from suffix to clitic, as in old-maidish (30), are instances of constructional change. Conversely, the development of approximative ish, as in 7-ish (31), gives rise to the formation of a new construction (35) and thus is an instance of constructionalization (see Traugott & Trousdale Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 234f.):

(35) Approximative ish schema

[[Ai/Ni.isc]Aj ↔ [having character like semi] property]j ]

Since Approximative ish sees a loosening of its selectional restrictions as well as the rise of the clitic variants in (30) and (31), the Approximative ish schema (35), like the Associative ish subschema (33b), is subject to constructional change. Our data support Traugott & Trousdale's (Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 237) claim that both schemata have seen an increase in productivity (see section 5).

Traugott & Trousdale (Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 236f.) see the rise of the free lexical item ish (32) as the result of a partially grammatical constructionalization process, with neoanalysis affecting both the formal properties of ish 3 (from clitic to free lexical item) and its meaning (from approximator to epistemic marker). Note that their postulate that the detachment of clitic ish 3 and thus the rise of the free lexical item ish is accompanied by a semantic shift from approximator to epistemic marker is irreconcilable with Kuzmack's (Reference Kuzmack2007: 1, 8) claim that both ish 2 and ish 3 preserve their respective identities as ‘comparer’ and ‘qualifier’ across construction types. Despite relevant data being extremely scarce in the BNC, free lexical ish clearly has an epistemic flavor as it codes the speaker's epistemic stance towards ‘veracity of the item as a member of a particular set’ (Traugott & Trousdale Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 236; see also Oltra-Massuet Reference Oltra-Massuet2016).

Even though expressing epistemic stances brings free lexical ish in the vicinity of evaluative adverbs, ish is not a representative of adverbial categories (pace Kuzmack Reference Kuzmack2007: 2, 8; see also below). Traugott & Trousdale (Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 236) argue that free lexical ish does not hold membership in any lexical category (see also Norde Reference Norde2009: 225), but rather is a functional item in the vicinity of scaling degree elements.

As with the first strand of theorizing, our empirical study again provides substantial support for the descriptive formalization of the diachronic trajectory of -ish, as outlined in constructionalization theory.

6.3 Distributed Morphology

While Traugott & Trousdale (Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 236) consider free lexical ish a degree element syntactically, Oltra-Massuet's (Reference Oltra-Massuet2017) morphosyntactic account, the third strand of theorizing, rests on the assumption that all instances of affixal -ish Footnote 24 represent degree operators semantically (see also Bochnak & Csipak Reference Bochnak and Csipak2014). The theoretical background for Oltra-Massuet's (Reference Oltra-Massuet2017) analysis is Distributed Morphology (see Marantz Reference Marantz1997, Reference Marantz2007), a syntactic model of morphology where roots are not specified for category until they are inserted into exoskeletal syntactic structures, so-called categorization structures, where an uncategorized root merges with a categorizing head. Essentially, in her analysis, ish 1, ish2 and ish 3 are spell-outs of one and the same underspecified root -ish that result from -ish being inserted into different category-defining functional head positions in clause structure, so-called phase heads, which are selected by a higher functional head endowed with the feature [approx(imator)].

Details aside, depending on the phase head that affixal -ish is inserted into, -ish derivatives from nominal and verbal bases receive one of three interpretations (see Oltra-Massuet Reference Oltra-Massuet2017: 65ff.):

(36)

(a) manner → like N/similar or close to a (proto)typical N

(b) central coincidence → have/with N

(c) undefined → idiosyncratic interpretation

The interpretation in (36a) is typically found with root nouns denoting humans or animals (37a,b), proper names (37c) and nationality-denoting bases (37d) (data from BNC):Footnote 25

(37)

(a) He pursed his big mouth into such a babyish pout …

(b) This, she thought with a sheepish giggle to herself, was ridiculous.

(c) He was a handsome chap in a sinister sort of way, Al Caponish with a dash of

Dracula and a smidgen of Rambo thrown in …

(d) Later in the year, when we visit the area again, we heard that the Swedish Lapps had fenced off an area of the Dividal National Park, with over five kilometres of wire.

Roots that are mass nouns typically trigger the interpretation in (36b):

(38)

(a) I rose, broke my fast and slipped the landlord some pieces of silver which made his vinegarish face look more congenial and subservient. (BNC)

(b) His temperature was high, almost feverish. (BNC)

The idiosyncratic interpretation (36c) is typically found with verbal roots (39), and the derivation process is synchronically unproductive (data from BNC):

(39)

(a) He's the nearest I've ever seen him to snappish …

(b) I don't want to know you're bound to feel a bit peckish when you wake up.

A property that is shared by all derivatives in (37)–(39) is that they are gradable adjectives and as such support degree modifiers, e.g. too, enough, slightly, a bit (data from BNC):

(40)

(a) For one thing it was too babyish – Moses Arkwright would never do anything

with so little risk attached to it …

(b) she found her slightly feverish and put her to bed.

(c) you're bound to feel a bit peckish when you wake up.

However, Oltra-Massuet (Reference Oltra-Massuet2017: 63ff.), essentially following Morris (Reference Morris1998), claims that -ish derivatives from adjectival bases, such as tallish, are non-gradable adjectives, and as such resist gradation and degree modification ((41) from Oltra-Massuet Reference Oltra-Massuet2017: 63):

(41)

(a) *more tall-ish, *tall-ish-er

(b) *very tall-ish, *extremely tall-ish

(c) *John is too tall-ish to become a miner.

(d) *I don't know how tall-ish Sue is.

Under her analysis, the strings in (41) are ruled out since the phase head that affixal -ish is inserted into is quantificational and categorizes ish as a degree operator on a par with degree expressions, such as comparative and superlative markers or very, too and how in (41) which Oltra-Massuet (Reference Oltra-Massuet2017: 63) takes to spell out the same head.

In her ‘descriptive typology of -ish’, Oltra-Massuet (Reference Oltra-Massuet2017: 57) lumps together -ish derivatives from adjectival bases with -ish derivatives from adverbial, numeral and phrasal bases, all incarnating ish 3 and all claimed to be non-gradable adjectives. Unfortunately, she does not provide any data in support of this claim. In fact, the assertion – perpetuated from Morris (Reference Morris1998) – that deadjectival -ish forms ‘refuse most attempts at intensification’ (Morris Reference Morris1998: 210) defies the empirical evidence. Instances of degree modifiers with -ish derivatives from adjectives (42), and to a lesser extent also adverbs (43), quantifiers (44) and phrases (45) are well-attested across our corpora as of (Early) Modern English:

(42)

(a) they thought that tasted a little Bitterish to the Palat (EEPF)

(b) She had an Angelical Countenance, onely somewhat brownish by the Suns

frequent kissing of it; (EEPF)

(c) This has been rather smartish, Mr. Simple. (NCF1)

(d) ‘Perhaps it was too prudish,’ she said repentantly. (NCF2)

(43) But then I was more uppish than I had ever been. (EEPF/ECF1)

(44) This stuff is very more-ish. (BNC)

(45)

(a) Lord, child, don't be so precise and [old maid]ish. (ECF2/NCF1)

(b) but Doleful, a very [cock-a-hoop]ish caller on his own account (NCF2)

Like Traugott & Trousdale (Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 236), Oltra-Massuet (Reference Oltra-Massuet2016) assumes that free lexical ish, which she refers to as propositional ish, is speaker-oriented (see also Bochnak & Csipak Reference Bochnak and Csipak2014: 435). Specifically, she argues that free lexical ish expresses the speaker's ‘lack of full commitment to the illocutionary force of the [assertive] speech act and [her] lack of full commitment to the proposition expressed’ (Oltra-Massuet Reference Oltra-Massuet2016: 312), which brings it into the vicinity of speaker-oriented adverbs, notably evaluative adverbs, such as fortunately or surprisingly, which she takes to be located in the specifier position of Sentient/Eval(uative)P (cf. Speas & Tenny Reference Speas and Tenny2003: 331ff.). The derivation of free lexical ish involves the insertion of the underspecified root into the head position of Sentient/EvalP, which is the complement of the head of SpeechActP ((46) adapted from Oltra-Massuet Reference Oltra-Massuet2016: 311):

(46) [SpeechActP SpeechAct0 [approx] [Sentient/EvalP Sentient/Eval0 […]]]

In Sentient/Eval0, ish establishes a relation between the propositional complement and ‘some sentient mind that evaluates it’ (Oltra-Massuet Reference Oltra-Massuet2016: 311). Since ish is in the immediate scope of SpeechAct0[approx], the propositional complement is evaluated as a weak assertion. Thus, free lexical ish as in (23) above, repeated for convenience in (47), reflects the speaker's lack of full commitment to the assertion that some people are normal:

(47) You must try to remember that some people are normal. Ish. (BNC)

Oltra-Massuet (Reference Oltra-Massuet2016, Reference Oltra-Massuet2017) aims at developing a unified morphosyntactic approach to both the affixal variants of ish and free lexical ish. Her analysis does not take into consideration the diachronic trajectory of ish, but rather presents synchronic (morpho-)syntactic snapshots of ish 2 and ish 3. By and large, her analysis is compatible with our empirical findings. Not tenable empirically, however, is Oltra-Massuet's (Reference Oltra-Massuet2017) claim that -ish derivatives from adjectives, adverbs, numerals and phrasal bases are non-gradable adjectives and thus incompatible with degree modifiers.

To conclude our empirically based reassessment of the theoretical accounts of -ish in sections 6.1 to 6.3, different theoretical credos and different emphases aside, both the diachronic trajectory of -ish from derivational suffix to free lexical item and the partial arcs that constitute the trajectory are surprisingly accurate and faithful to our empirical data. ‘Surprisingly accurate’ because none of the theoretical accounts discussed seems to have based their description and analysis on a large-scale empirical study.

7 Conclusion and outlook

This article has explored the path of development that -ish underwent in the diachrony of English, evolving from an originally nationality-denoting suffix with relational semantics to a suffix that came to take a wide array of different bases and extend the relational sense to an associative as well as approximative sense. The crosscategoriality and multifunctionality of -ish resulted in the evolution of more or less fully clitic uses, thus transgressing the borders between morphology and syntax. Against this backdrop, our analysis contributed to the research on the diachrony of -ish derivation in three respects. First, it provided a thorough empirical investigation of how -ish extended its range of application from OE to PDE (section 4). Second, the fine-grained analysis of the word-formation pattern of -ish differentiated for base categories allowed for the assessment of the increasing productivity of -ish (section 5), revealing which base categories are clear productivity winners (i.e. nouns as well as adjectives) and which contribute to the creativity of -ish (i.e. the more marginal base categories that comprise a considerable number of hapax legomena). Third, the present analysis made an attempt at triangulating empirical data with theoretical accounts of the diachrony of -ish, thereby providing support for most of the previous claims made in the literature and refuting others (section 6).

For future research, it would be of high interest to explore the diachronies of the full set of Germanic adjective-deriving suffixes, especially -y, which seems to be a close competitor to -ish. Surely, -ish displays some characteristic traits that its Germanic siblings are lacking, such as the attachment to adverbial and numeral bases since the eighteenth and twentieth centuries respectively or the ability to combine with phrasal bases since the nineteenth century, but the diachronic investigation of all Germanic adjective-deriving affixes might point out why -ish is so peculiar in this regard or to what extent, for example, -y is likely to catch up in the long run. Also, the competition between -ish and Romance -ic lends itself to a follow-up study in that the two suffixes are functionally equivalent but turn out to be distinctive in terms of the frequency of their bases; as Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Lieber and Plag2013: 496) observe, ‘-ish has many derivatives with low frequencies (such as housewifish, out-of-the-way-ish, or soupish) whereas -ic has few low-frequency words but many derivatives with higher frequencies (e.g. democratic, fantastic, terrific) so that -ish tends to be more separable than -ic’, a fact that awaits empirical validation in order to shed light on the impact that frequency has on the separability, cliticization and eventual severing/debonding of an affix.

Also, it will be interesting to keep track of -ish in PDE and further explore to what extent -ish continues to be used innovatively and creatively – and to what extent it displays a behavior as a word-forming element that is both rule-bending and theory-challenging. Particularly the approximative sense that -ish has developed over the course of time seems to lead to an ever increasing number of innovative word creations – maybe because, as reflected in a children's book, ‘[t]hinking ish-ly allow[s] ideas to flow freely’ (Reynolds Reference Reynolds2005: 20).