1 Introduction

There are two standard types of absolute constructions in English: one augmented with an expression like the with-ac, and the other with no such augmented expression (see, among others, Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 1106; Stump Reference Stump1985: 8; Kortmann Reference Kortmann1991: 103; Biber et al. Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999: 136; Huddleston & Pullum Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1265). The following are two corpus examples drawn from COCA (Corpus of Contemporary American English):Footnote 2

(1)

(a) [With nobody taller than 6–2], a lack of size will be a problem all season. (COCA 2003 NEWS)

(b) [Him being a physician], he's more pragmatic. (2010 NEWS)

The bracketed absolute clause in each case stands alone without any overt expression of a syntactic linkage, but it functions as a modifier to the matrix clause. Its meaning relation with the matrix clause is dependent upon the context (see, among others, Stump Reference Stump1985: ch. 6; Kortmann Reference Kortmann1991: 26–32; Huddleston & Pullum Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1255–6).

An additional construction is the so-called what-with ac, which is illustrated by examples from COCA:

(2)

(a) You've got papers coming in from your students, I'm sure, [what with Thanksgiving break next week]. (COCA 2012 FIC)

(b) [What with him being a physician], he's more pragmatic. (COCA 2010 NEWS)

As seen from these data, the expression what with combines with an NP or a nonfinite clause or verbless SC (small clause).Footnote 3

The what-with ac is thus similar to the two standard absolute constructions (acs) in the sense that the nonfinite clause, introduced by an augmented expression, functions as a modifier. However, its uses are more restricted than the standard acs. For instance, the what-with ac semantically functions as a ‘reason’ adjunct, meaning something like ‘in consequence of, on account of, as a result of, in view of, or considering’ (see Huddleston & Pullum Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 626; Felser & Britain Reference Felser and Britain2007). Pragmatically speaking, as pointed out by Kortmann (Reference Kortmann1991: 2002), the matrix clause modified by the what-with ac typically denotes some negative implications from the point of view of the speaker.

(3)

(a) He felt a bit dizzy [what with all the alcohol he'd consumed]. (COCA 1997 FIC)

(b) There hasn't been much opportunity, [what with Emily's wedding]. (COCA 1990 FIC)

In each of these two examples, the state of affairs (his alcohol consumption and Emily's wedding, respectively) described by the what-with ac could be the reason for the unfortunate situation (being dizzy and less opportunity) denoted by the matrix clause.

The what-with ac, whose key features we have noted here, has not received much attention, mainly because of its idiomatic properties. Fillmore et al. (Reference Fillmore, Kay and O'Connor1988), noting its unpredictable, peripheral properties, take the construction as an independent grammatical construction, whose form–meaning mapping relations do not follow from those of core constructions. McCawley (Reference McCawley1983) and Kortmann (Reference Kortmann1991) also note its distinctive behavior from standard acs, while pointing out its unique semantic and pragmatic functions. Huddleston & Pullum (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 626), emphasizing its idiomatic properties, add the following note:

One idiom that does not belong with any of the structural types considered above is what with, used to introduce a reason adjunct, as in [What with all the overtime at the office and having to look after his mother at home], he'd had no time for himself for weeks. This idiom has developed out of an otherwise almost obsolete use of what to introduce lists or coordinations …

In contrast to previous literature, which takes the what-with ac to be a special grammatical construction, Felser & Britain (Reference Felser and Britain2007) argue that the construction is highly compositional. Based on 313 tokens from the BNC (British National Corpus) and 300 tokens from the internet, their analysis offers a Minimalist approach (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1995), arguing that the absolute clause forms an array of functional projections, such as Evaluative Phrase headed by what while with functions as the head of CP, as shown in the following:

(4) [EVALP what [EVAL Ø[CP [C with [TP ….]]]]]

As represented here, their analysis takes both what and with to be in the functional projections. In particular, as given in the following, with is a prepositional complementizer that takes a TP complement, while what is an evaluative operator located in the Spec of CP (Eval P). The key to their analysis is that the syntactic and interpretive properties of the construction are neither idiomatic nor constructional; its syntax and semantics just follow the principals of not peripheral but core grammar. Trousdale (Reference Trousdale2012), arguing against such a compositional-based analysis, looks into the construction from a grammaticalization perspective. Based on 500 randomly selected tokens from COCA and 70 tokens of the construction from the Late Modern English corpus, CLMETEV (Corpus of Late Modern English Texts), Trousdale notes that the construction has become more ‘general’, ‘productive’ and ‘less compositional’, which has been taken to be key evidence for the process of grammatical constructionalization (Traugott Reference Traugott, Eckardt, Jäger and Veenstra2008; Trousdale Reference Trousdale, Trousdale and Gisborne2008; Traugott & Trousdale Reference Traugott, Trousdale, Traugott and Trousdale2010: 11–19).

This article, supporting a construction-based analysis (Trousdale Reference Trousdale2012), investigates the historical aspects of the what-with ac with much more representative data. In particular, we consider a total of 1,783 tokens from the historical corpus COHA (Corpus of Historical American English; 1820–2009). This is the main corpus that we use, but when necessary we also refer to 2,466 tokens from EEBO (Early English Books Online; 1470–1690), as well as 1,376 tokens from COCA. With this much larger set of historical data, we set out the following goals in this article:

• to investigate the historical development of the construction, together with its syntactic, semantic and pragmatic properties;

• to examine whether the construction has become more common or less common in English over time;

• to check whether there are any changes in the grammatical triggers for the uses of the construction;

• to examine the changes in the grammatical properties of the construction, focusing on its complement type, semantic compositionality and pragmatic constraints.

In addition to these analytic goals, we also attempt to offer an analysis that can account for the diachronic properties from a grammaticalization perspective, as well as the synchronic properties of the construction from the perspective of Construction Grammar.

This article is organized as follows. In the next section, we briefly describe the corpora that we use in this study and offer simple frequency information for the what-with ac. Section 3 then reviews various grammatical properties of the what-with construction while referring to the data we obtained from COHA. In this section, we discuss the syntactic, semantic and pragmatic properties of the construction that we observe from the historical corpus data. Section 4 sketches a Construction Grammar approach that can account for both the diachronic as well as the synchronic properties of the construction. After exploring ways to express generalizations for a family of absolute constructions – including the what-with ac – the section also discusses the historical development of the construction from a grammaticalization perspective.

2 Basic findings from corpora

The main corpus that we have used in this study is COHA. The corpus contains more than 400 million words of text from the 1810s–2000s. In addition, we also used two other corpora, COCA and EEBO, when necessary. COCA has 560 million words of American English in texts from 1990 to 2017, evenly divided between spoken, fiction, popular magazine, newspaper and academic. EEBO has 755 million words from nearly 30,000 texts from the 1470s–1690s.

In searching the data, we have adopted a simple string search ‘what with’, and then filtered out irrelevant examples like the following:

(5)

(a) Ah, what with that frame can he do? (COHA 1983 FIC)

(b) It must have something to do with that. But what with that? (COHA 1850 FIC)

In such examples, what and with are used as an interrogative pronoun and a preposition. After ‘cleaning’ the data in this way, COHA yielded 1,783 tokens and EEBO 2,466 tokens of the what-with ac, which we used for the quantitative as well as the qualitative portions of this study.

The frequency data from the two historical corpora EEBO (figure 1) and COHA (figure 2) indicate that the use of the construction is not overly high, but that it has been steadily used for the last 600 years, as seen from the (normalized) trend lines of the construction in EEBO (1470s–1690s) and COHA (1810s–2000s).

Figure 1. Trend line of the what-with ac in EEBO (total 2,466 tokens)

Figure 2. Trend line of the what-with ac in COHA (total 1,783 tokens)

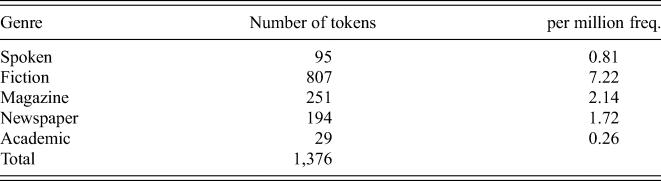

To check the usage of the what-with ac in PDE (Present-day English), we have also examined the data from COCA. Among the five registers (spoken, fiction, magazine, newspaper, and academic) in COCA, the what-with ac is predominantly used in the ‘fiction’ genre, as seen in table 1. In the historical corpus COHA as well, we observe that the what-with ac has the highest frequency in fiction, as shown in table 2.

Table 1. Frequency of the what-with ac in the four registers in COCA

Table 2. Frequency in the four registers of COHA

Felser & Britain (Reference Felser and Britain2007) note that the what-with ac is ‘more likely to occur in conversational data than in written data’. Kortmann (Reference Kortmann1991: 202) also notes that the what-with ac is mainly used in colloquial speech. In the five different registers of COCA, the spoken genre is the fourth in terms of the normalized frequency (tokens per million words). COHA does not have spoken data, but the construction is highest in fiction.Footnote 4 We may take fiction to be closest to spoken, but many instances of the what-with ac in fiction are narrative.Footnote 5 We conjecture that this preference for fiction has to do with the functional characteristics of the construction, as well as the characteristics of fiction. In fiction, an imaginary world is created in which the author helps us interpret events occurring there by explaining causal relationships (the main function of what-with ac) explicitly – e.g. why did Lee do X, how is it that Lee never even decided to Y, etc. It is true that these casual relations are spelled out in other genres as well (e.g. magazines), but they are more important in fiction (see Todorova Reference Todorova2013 also for a similar point).

3 Grammatical properties

Of the three corpora used in this study, COHA is the main corpus that we have used to investigate changes in the grammatical properties of the construction. This is mainly because COHA offers data from Late Modern English to Present-day English (1810s–2000s), which may show us both diachronic and synchronic aspects.Footnote 6

3.1 Syntactic properties observed in the diachronic data

As noted in the literature, the first thing we can observe from the corpus data is that the what-with ac has flexible distributional possibilities. It can occur in sentence-initial, medial or final position, functioning as a sentential modifier to the main clause:

(6)

(a) [What with Angela and his new book], he had simply not noticed. (COHA 1975 FIC)

(b) … but the subsidiary rights, [what with the TV and film], could go as high as three million, Mrs. Williams. (COHA 1981 FIC)

(c) None got killed which is more than I can say about what they want to do to him, [what with all these weapons]. (COHA 2001 FIC)

The position of the construction may lead to a difference in the ease or difficulty of processing (Kortmann Reference Kortmann1991: 138; van de Pol & Hoffmann Reference van de Pol and Hoffmann2016), but the distributional position does not determine its meaning relation with the matrix clause.Footnote 7 The expression after what with forms a syntactic constituent, which is evidenced by the fact that it can be an antecedent of a relative pronoun as in (7a), and it can be the locus of conjoining as in (7b).

(7)

(a) [What with [Carol out of work and all]I], whichI I didn't know, they didn't send any Christmas cards this year. (example from Kortmann Reference Kortmann1991: 203)

(b) [What with [[the prices being so high] and [my wife being out of work]]], I can't afford to buy a new refrigerator. (example from Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 1106)

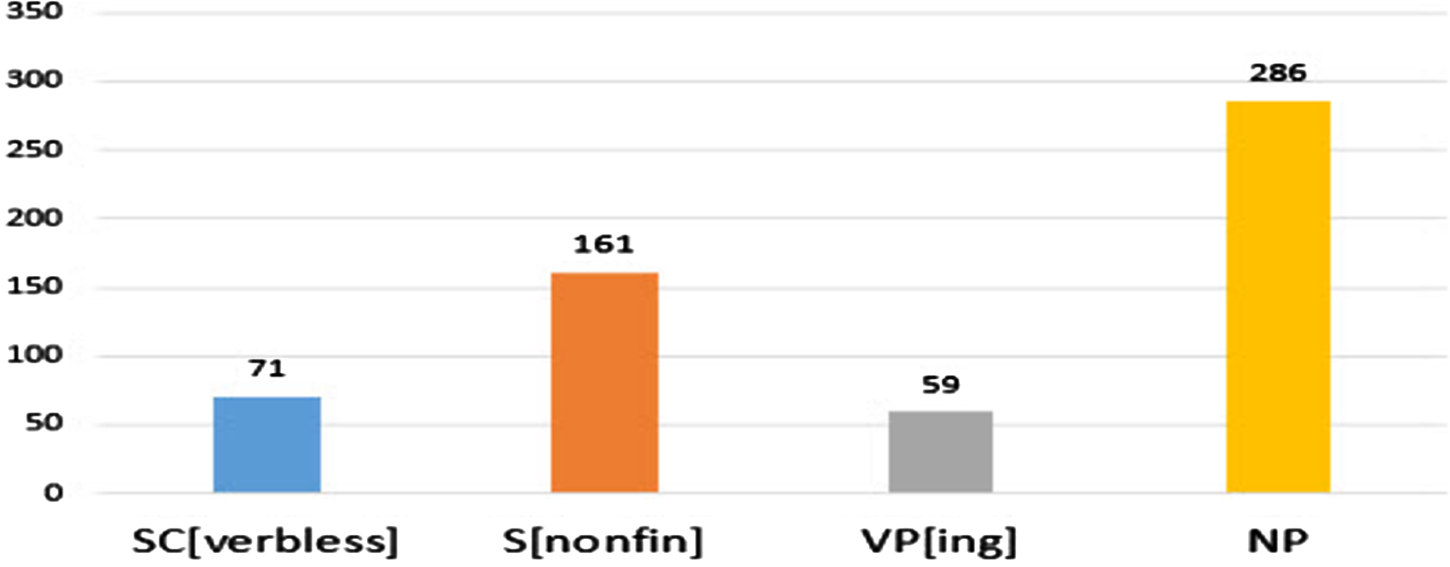

As for the complement type of what with, the construction allows a variety of syntactic categories: NP, VP headed by a gerundive verb, verbless SC (small clause), or nonfinite S headed by a participle en/ing verb (see figure 3 for the frequency of each complement type in COHA). Of these complement types, a simple NP or NP coordination is the most frequently used; examples are given in the following:

(8)

(a) [What with [these Alfas]], they might be trying to blockade our coast. (COHA 1983 FIC)

(b) [What with [the heat and the flies]], I dare say he would take it. (COHA 1873 FIC)

Figure 3. Frequency of each complement type of what with in COHA

The corpus data also illustrate that in addition to typical NPs, other nominal-like gerundive VPs can serve as the complement of what with.

(9)

(a) The poor President, [what with [preserving his popularity and doing his duty]], is completely bewildered. (COHA 1863 MAG)

(b) [What with [tending to his father]] it would be a rugged night. (COHA 1956 FIC)

As expected from the possibility of having a gerundive VP as the complement of what with, the corpus also yields data in which a sentential gerundive functions as the complement of what with:

(10)

(a) [what with [Rosy helping him with his plans and figures]], and so on, he got an extra good idea of mechanics (COHA 1857 FIC)

(b) [What with [everyone trying to say something smart and witty]], I got a bit sleepy and lost most of the threads (COHA 1941 FIC)

(c) [What with [him threatening all the time to blow my head off]]! (COHA 1930 FIC)

These examples have the accusative NP as the subject of the gerundive VP. Our corpora also yield some examples of sentential gerundives with the subject being marked with genitive:

(11)

(a) As for the shepherds, [what with [their setting off for Bethlehem]], well known for its good and bad thieves, keeping their watches was a very friendly gesture on the part of the angels. (COCA 1991 MAG)

(b) [What with [my being my father's son and all that]], my father is going to suffer. (COHA 1896 FIC)

In addition to these nonfinite S-gerundive examples, the corpus yields other examples in which the complement is a nonfinite S type:

(12)

(a) I was in pretty punk shape myself, [what with [the body cast and my head still wrapped in bandages]]. (COHA 1997 FIC)

(b) [What with [the heaviness attached to my body]], I experienced during that brief time great difficulty in keeping my head … (COHA 1894 MAG)

In these examples, the head of the nonfinite S complement is a perfect participial VP. The nonfinite S complement includes other verbless SCs whose predicate is an AP or a PP:Footnote 8

(13)

(a) it was all just a matter of love at first sight, [what with [him so dark and intense by that painting of his]], …. (COHA 2000 FIC)

(b) And [what with [Jonathan in the queer state he is in]]. I don't know what else to do. (COHA 1987 FIC)

The sentential properties of the clausal complement can be attested by many phenomena, as seen from the following examples (see also Geney Reference Geney1994; Felser & Britain Reference Felser and Britain2007; Trousdale Reference Trousdale2012):

(14)

(a) Passivization:

… [what with [convoys getting knocked off by submarine]] – but this came in – … (COHA 1951 FIC)

(b) Expletive it:

Yeah, well, you tell her it'll be five, [what with [it being not even nine in the night]]. (COHA 1973 FIC)

(c) Sentential negation:

… [what with [men not daring to venture upon wedlock]], and [what with men wearied out of it], all inordinate license might abound. (COHA 1869 FIC)

(d) Sentential adverb:

[what with [the votes actually given and the proxies]], the Opposition majority was immense. (COHA 1861 MAG)

These examples indicate that the clausal complement of what with can be a passive sentence and it can also include a sentential negation. Its subject can be not only a normal NP but also the expletive it. The complement can also include a sentential adverb. All of these phenomena support the fact that that what with can combine with a sentential complement.

With respect to the frequency ranking of the complement types (excluding coordination examples), the simple NP is the most predominant, followed by the nonfinite S[en/ing] complement, as shown in figure 3.Footnote 9

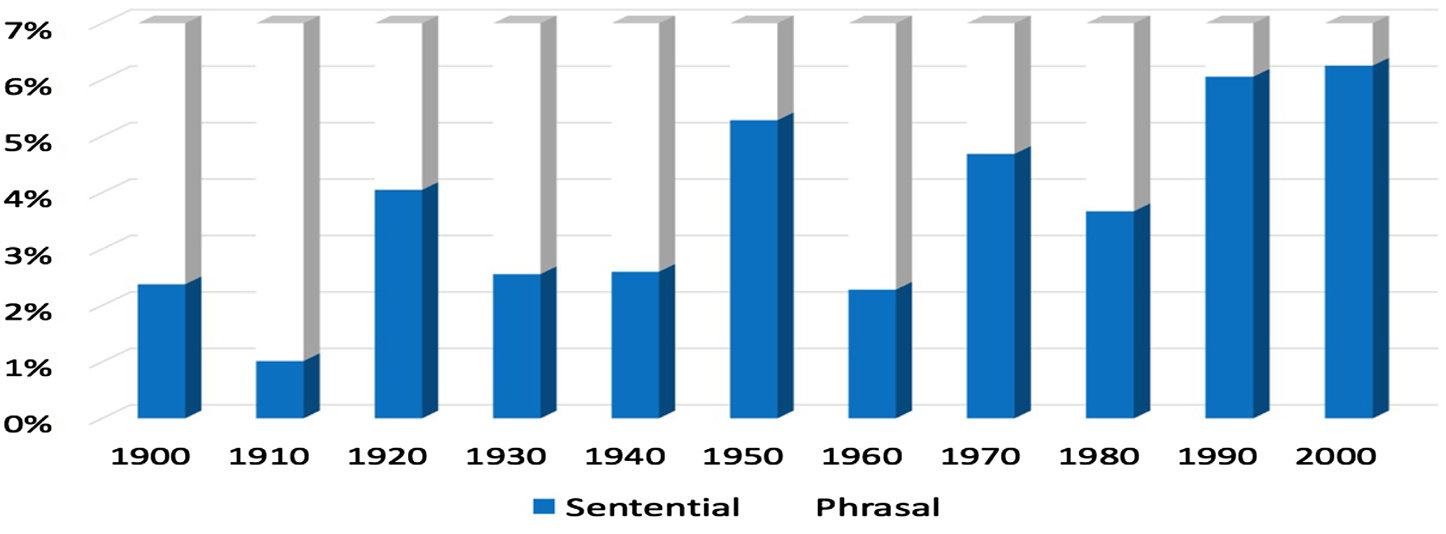

If we take the verbless SC (SC[verbless]), nonfinite S (S[nonfin]) and gerundive VP (VP[ing]) as types of ‘clausal’ complements, we would have no significant difference between the frequency of clausal complements and that of NP complements. One interesting trend from the COHA data is that the overall use of clausal complements (compared to phrasal complements) is increasing in frequency. Figure 4 shows the frequency of clausal complements (as a percentage of all complements) in each decade since the early 1900s. The figure shows that clausal complements typically constituted 2–3 percent of all complements 100 years ago, but they have nearly doubled since then, especially in the last twenty to thirty years. This implies that the preposition with started to gain sentence-introducing complementizer properties in the early twentieth century. Both the preposition and complementizer-like properties of with also seem to allow the coordination of unlike categories, which we will consider in detail in the following section.

Figure 4. Increased frequency of the clausal complement in COHA

3.2 Like and unlike category coordination

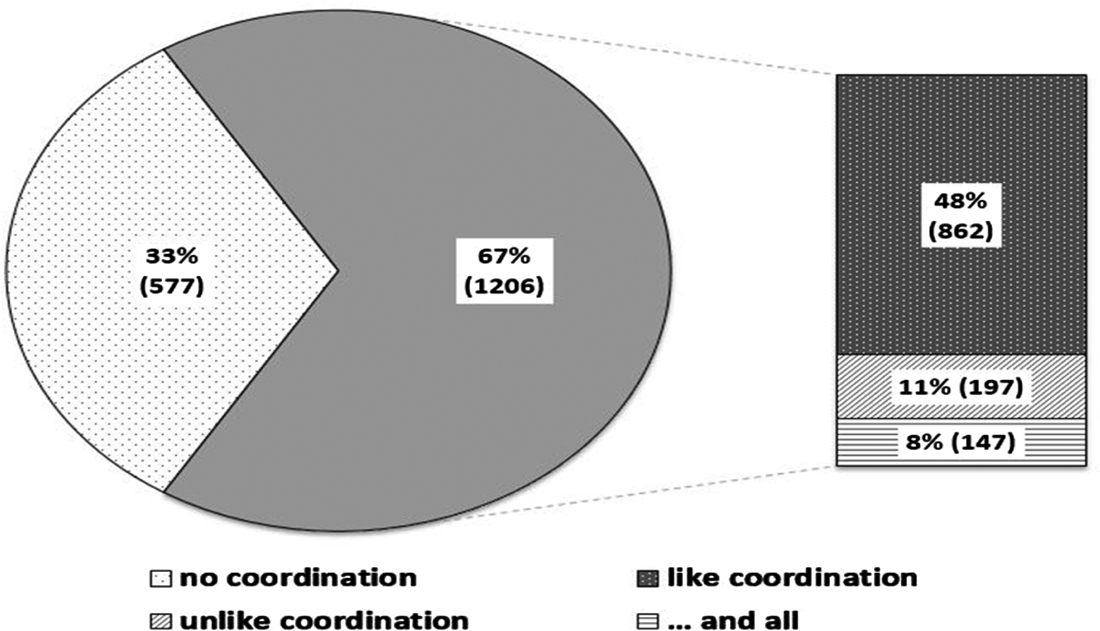

Unlike other types of absolutes, the what-with ac often introduces an NP coordination as well as other clausal coordination (Felser & Britain Reference Felser and Britain2007; Huddleston & Pullum Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 626). As seen from figure 5, more than two-thirds of the corpus data are examples of coordination.Footnote 10 Of the total 1,783 tokens of the construction in COHA, more than one thousand tokens are examples of coordination, which can be grouped into three different types: like category coordination (48%), unlike category coordination (11%) and and-all coordination (8%), which we will discuss below. Such a high frequency of (like or unlike) coordination data is not observed in the other type of acs. The high frequency of coordination seems to have to do with one of the pivotal functions of the what-with ac: the construction prefers to introduce more than one reason for the event or state described in the matrix clause.

Figure 5. Frequency of non-coordination and coordination of like and unlike categories in COHA

In the like category coordination data (862 tokens), we observe that the most typical type is the coordination of two NP conjuncts (699 tokens):

(15) [What with [[the stack-ups] and [the taxis]]], he's probably not home yet. (COHA 1973 FIC)

The other main type of coordination is the coordination of two clausal expressions (163 tokens):

(16)

(a) But you know my heart ain't in it so much, Willard, [what with [[Jimmy laid up] and [the place shut down]]]. (COHA 1956 FIC)

(b) I feel as creative as Leonardo da Vinci, [what with [[the baby going on inside] and [the house going up outside]]]. (COHA 1952 FIC)

The clausal conjunct can be either a verbless SC (small clause) or a nonfinite S.

An intriguing property of what-with ac coordination is that it licenses the coordination of unlike categories (total 197 tokens, 11%).Footnote 11

(17) NP and VP[ing]

but [what with [[the coffee] and [being scared out of her wits besides]]], she couldn't possibly sleep. (COHA 1957 FIC)

(18) NP and S[nonfin]

[What with [[limited housing] and [nobody on the island authorized to make a marriage legal]]], things had come to a pretty pass. (COHA 1955 MAG)

(19) NP and SC

We all asked one another where it was going to end, [what with [[the picnic next day], and [him always at the Mission house]]]. (COHA 1921 FIC)

All of these examples of coordination have an NP as their first conjunct and a nonfinite S as the second conjunct. Note that the corpus also yields data for coordination with the first conjunct being a gerundive VP and the second conjunct being a nonfinite S or an NP:

(20) VP[ing] and S[nonfin]

[what with [[driving the natives out] and [the war waged with Mexico]]], they have cost us millions of treasure and thousands of lives. (COHA 1862 MAG)

(21) VP[ing] and SC

[What with [[seeing him again] and [his kindly face behind its glasses]]], the cheerful faith in me which was his contribution to our friendship, … (COHA 1975 FIC)

(22) VP[ing] and NP

Up to that instant, [what with [[chanting and singing the many services], and [the noise of talking and walking]]], there was a wild babel. (COHA 1872 NF)

As expected from such variation, the corpus also allows the unlike coordination of a nonfinite S with an NP or a gerundive VP:

(23) S[nonfin] and NP

But he has had a bad time of it lately, [what with [[the Rainbow being banned] and [no money]]]. (COHA 1979 FIC)

(24) S[nonfin] and VP[ing]

who was in such a pickle, [what with [[my clothes torn to shreds], and [dripping with water]]], … (COHA 1839 MAG)

Figure 6 shows the frequency for the patterns of unlike coordination. As is shown here, the dominant pattern is the NP serving as the first conjunct. Of these, the most frequent type of unlike coordination is the coordination of an NP with a nonfinite S. The frequent use of unlike category coordination in the construction suggests the mixed properties of with: NP-introducing preposition and S-introducing complementizer.

Figure 6. Frequency of the coordination of unlike categories

Another type of coordination that we should mention is one in which the noninitial conjunct is underspecified with expressions like and all, and everything and and another.Footnote 12 A total of 8 percent of the unlike coordination examples (147 tokens) includes these extenders.Footnote 13

(25)

(a) I'm upset myself, [what with this going back and everything]. (COHA 1913 FIC)

(b) ADM is one of his great benefactors, [what with that Face-Off show and all]. (COHA 1990 MAG)

(c) And at the very worst time, [what with one thing and another], we had a larger income than my father had in Merleville. (COHA 1869 FIC)

The expression one thing and another is typically used to cover various unspecified matters or situations. Of these three, the most typical phrase is and all:

(26)

(a) You just can't tell, [what with my being a schoolteacher and all]. (COHA 1954 FIC)

(b) Actually, [what with being the captain and all], I can come and go as I wish (COHA 1999 FIC)

In this kind of example, the first conjunct introduces one reason, which is linked to the situation described by the matrix clause. This seems to be linked to the semantic/pragmatic functions of the construction, which we discuss in the following section.

3.3 Semantic and pragmatic properties

As noted earlier, syntactically the what-with ac behaves like the two other standard acs, with ac and nonaugmented ac. Its main differences from these two come from semantic and pragmatic properties. We have noted that the what-with ac serves as a reason adjunct. The most widely used ac, the with ac, in general can convey manner or accompanying circumstances, as illustrated in (27a) and (27b), respectively:

(27)

(a) She tried to conjure him, with her eyes closed. (COCA 2006 FIC)

(b) With his right hand put forth, he put it against it. (van de Pol & Hoffmann Reference van de Pol and Hoffmann2016:18)

The roles of absolute clauses, like other adjuncts, range from a temporal setting to a logical relation and to a speaker's attitude (Ishihara Reference Ishihara1982; Stump Reference Stump1985: 97; Kortmann Reference Kortmann1991: 142). As noted by van de Pol & Hoffmann (Reference van de Pol and Hoffmann2016) and others, the with ac can also express cause, condition, or concession, and simultaneity or anteriority (cited from van de Pol & Hoffmann Reference van de Pol and Hoffmann2016: (29)–(32)):

(28)

(a) With 40 million people starving and infant mortality rising at an alarming rate, doctors must start pressurising governments and banks to stop this spiral of deprivation and environmental degradation (BNC, 1985–1994) (reason)

(b) With you with us they'll've won the war before we've finished the movie. (KU Leuven drama corpus, 1971) (condition)

(c) With vital statistics rumoured to be 41–39-extra large, she will only admit that her dress size is the biggest. (BNC, 1985–1994) (concession)

(d) With my form filled in, I phoned. (BNC, 1989) (anteriority)

Unlike the diverse semantic relations in nonaugmented absolutes or the with ac, the what-with ac represents only the ‘reason’ (or cause) for the situation conveyed by the matrix clause. This is why in terms of temporal relations, the what-with ac does not describe a posterity relation, but in general has a sequential or simultaneous reading relation with the matrix clause, as shown in (29a) and (29b), respectively:

(29)

(a) [What with Monty tugging at him], Archie turned his bull neck. (COHA 1993 FIC)

(b) [What with Martha sitting on the cushioned brake in the middle], they went into town and bought a cold chicken. (COHA 1957 FIC)

A related meaning difference concerns the possibility of having a conditional meaning: unlike the with ac with a conditional meaning, the comparable what-with ac does not induce a conditional meaning (Felser & Britain Reference Felser and Britain2007). Consider the following data:

(30)

(a) With mother being sick and Ellen on holiday, I don't know how to keep the children under control. (⇒ If mother is sick and Ellen is on holiday, …)

(b) With the prices being so high and with my wife being out of work, I can't afford a new refrigerator. (⇒ If the prices are so high and my wife is out of work, …)

(31)

(a) What with mother being sick and Ellen on holiday, I don't know how to keep the children under control. (Kortmann Reference Kortmann1991: 203) (⇏ If mother is sick and Ellen is on holidays, …)

(b) What with the prices being so high and with my wife being out of work, I can't afford a new refrigerator. (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 1106) (⇏ If the prices are so high and my wife is out of work, …)

As observed here, the with ac in (30) can be paraphrased as an if-clause, but this is not possible in the what-with ac in (31). This semantic difference has to do with the fact that the what-with ac is linked only to a reason for the event denoted by the matrix clause. As pointed out by Felser & Britain (Reference Felser and Britain2007), the presence of what may restrict the construction to be interpreted as a factive.

There is another key difference between the with ac and what-with ac. The former in general offers an exhaustive list of the reasons while the latter allows a non-exhaustive list of reasons, even unspecified reasons (see Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 1106). This pragmatic implication is often encoded by examples of coordination. For instance, as we have seen, the second conjunct is often realized as all, everything and another:

(32)

(a) Thought you might need it, [what with the snow and all]. (COCA 1997 FIC)

(b) I know you must be a very busy man, [what with services and lectures and private counseling and house-hunting and all]. (COHA 1990 FIC)

(c) [What with one thing and another], I'd forgotten my already casual bookkeeping. (COCA 2011 FIC)

These extenders occur with the with ac much less frequently. Our corpus search yields only a few examples of the with ac with such extenders.Footnote 14

Kortmann (Reference Kortmann1991: 209) notes that a discourse property of the what-with ac is that it is typically used when the matrix proposition denotes some non-event or negative state, or evokes negative implications. Most of the examples from COCA also support this observation:

(33)

(a) Well, too expensive anyway, [what with the carbon taxes on long flights]. (COCA 2006 MAG)

(b) So maybe she was lonely, too, [what with her husband away so long]. (COCA 2006 FIC)

In these examples, the ac describes the reason for the situation of the matrix clause which in general describes failure or something unfortunate that has happened. COHA, however, also yields a number of examples with positive states or implications (see Felser & Britain Reference Felser and Britain2007 for a similar point):

(34)

(a) Life had gotten soft, he said, [what with having electricity since they laid the cables from the mainland after the hurricane] (COHA 2003 FIC)

(b) “You look cool and comfy yourself.” Wanda lifted a brow. “[What with you wearing a bathing suit and all].” (COHA 2009 FIC)

There are also neutral examples in the sense that the matrix clause cannot be interpreted as either positive or negative:

(35)

(a) Their houses look like spaceships, [what with all those Christmas lights]. (COCA 2002 NEWS)

(b) I remember when I first met them and was so surprised that Ernestine could weave colors and patterns, [what with her being blind and all]. (COCA 1994 FIC)

The increasing use of the construction with neutral and positive implications can be seen from the COHA data in each period. For instance, during the period 2000–9, there are 87 tokens of negative meaning, 16 tokens of neutral meaning, and 41 tokens of positive meaning. This indicates that non-negative uses are as frequent as negative uses. Figure 7 shows the frequency of the semantic prosody over time from 1810 to 2009.Footnote 15

Figure 7. Changes in the frequency per million of the semantic prosody in COHA

The dominant use of the what-with ac is for negative meaning, but the trend lines also indicate that the uses of positive and neutral connotation have been steadily increasing.Footnote 16 This kind of semantic/pragmatic shift seems to indicate that the construction has become more generalized semantically, suggesting some types of grammaticalization, which we will discuss in detail in section 4.2.

4 A Construction Grammar analysis

4.1 Key architecture

In accounting for the synchronic as well as the diachronic aspects of the what-with ac, we follow a CxG (Construction Grammar) approach, which can offer a streamlined way of addressing both the general and idiosyncratic properties of the construction. The main features of CxG can be summarized as follows (see, among others, Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995, Reference Goldberg2003, Reference Goldberg2006; Croft Reference Croft, Östman and Fried2005; Fried Reference Fried2009; Sag Reference Sag, Boas and Sag2012; Michaelis Reference Michaelis, Hoffman and Trousdale2013; Hilpert Reference Hilpert2014; Kim Reference Kim2016):

• All levels of description (including morpheme, word, phrase and clause) are understood to involve pairings of form with semantic or discourse functions.

• Constructions vary in size and complexity, and form and function are specified if not readily transparent.

• Language-specific generalizations across constructions are captured via inheritance networks, reflecting commonalities or differences among constructions.

Within this view, ‘constructions’ are thus taken to be the basic units of language and central to all linguistic descriptions and theories of language. Interpreted within the sign-based system, this means that all linguistic signs are taken to be ‘constructions’. A construction consists of a form and a meaning or a function connected with that form, which can be defined as follows (Goldberg Reference Goldberg2006: 5):

(36) Definition of grammatical ‘constructions’:

Any linguistic pattern is recognized as a construction as long as some aspect of its form or function is not strictly predictable from its component parts or from other constructions recognized to exist. In addition, patterns are stored as constructions even if they are fully predictable as long as they occur with sufficient frequency.

To put it simply, a construction is a form–meaning pair, whose meaning we cannot predict from syntactic combinations, as well as a form–meaning pair with high frequency whose meaning is compositional. Constructions are thus defined as not fully predictable form–function mappings or as sufficiently entrenched structures due to their high frequency.

The constructions identified in each language are related to each other through inheritance hierarchies in which sub-constructions can inherit constructional properties from their superconstructions (see Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995, Reference Goldberg2006; Ginzburg & Sag Reference Ginzburg and Sag2000; Sag Reference Sag, Boas and Sag2012; Traugott & Trousdale Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013; Hilpert Reference Hilpert2013; Kim Reference Kim2016). Within the system of inheritance hierarchy, superconstructions (macro)-express broad generalizations that are inherited by many other constructions; mid-constructions (meso)-posited at various midpoints of the hierarchical network capture limited patterns; low-level constructions (micro)-express exceptional patterns; the lowest level of constructions (‘constructs’) contains the largest amount of linguistic information. These four levels of constructions, summarized in the following, are thus hierarchically involved:

(37) Constructional schemas: a hierarchy (Traugott Reference Traugott, Eckardt, Jäger and Veenstra2008; Traugott & Trousdale Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 726)

(a) Macro-constructions: highly abstract, schematic constructions

(b) Meso-constructions: a network of related construction types which are still fairly abstract with similar semantics and/or syntax

(c) Micro-constructions: individual construction types

(d) Constructs: instances of micro-constructions, realizations of actual use.

In the present context, all absolute constructions can be taken as macro-constructions in which meaning–form pairings are defined by structure and function, while augmented and unaugmented absolute constructions are meso-constructions that include sets of similarly behaving constructions. The individual-construction what-with ac is a micro-construction, while each empirically attested token we have extracted from the corpora is a construct of the micro-construction (see (40)). In what follows, we will discuss how these four levels of constructions play a key role in capturing language-specific generalizations across absolute constructions.

4.2 A family of absolute constructions and constructional constraints

One key goal of CxG is to study language in its totality, without making any distinction between core and periphery (Goldberg Reference Goldberg2006; Sag Reference Sag, Boas and Sag2012; Michaelis Reference Michaelis, Hoffman and Trousdale2013; Kim Reference Kim2016). This also implies that the optimal investigation of a given phenomenon is to look into a family of related constructions, since we cannot separate each individual construction either as core or as peripheral. In what follows, we discuss how we can account for the what-with ac within this framework.

Throughout the article, we have seen that English has at least the following three acs:

(38)

(a) Non-augmented:

[Miami being a hot town], she has a light touch with fish. (COCA 2013 MAG)

(b) With augmented:

[With him being down], everybody on the other team piled on him. (COCA 2011 FIC)

(c) What with augmented:

I have no idea how I'm going to care for these kids, [what with Molly dying]. (COCA 2017 FIC)

In addition to these three, there is another augmented construction (Kortmann Reference Kortmann1991: 199):

(39)

(a) They left without a word, [and he so sensitive]. (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 944)

(b) She went first to her mother's state-room, [and the door being opened in answer to her gentle rap], … (COHA 1894 FIC)

This and ac is not frequently used in PDE, but it still exists. In the sense that this ac is a nonfinite clause unmarked for tense and mood and functions as a modifier, it is a type of ac whose existence we cannot ignore.

As we have discussed, inheritance hierarchies have long been found useful for representing all types of generalizations. Considering the properties of acs in English that we have discussed so far, we could posit the following inheritance network (see Riehemann & Bender Reference Riehemann, Bender, Bird, Carnie, Haugen and Norquest1999).Footnote 17

(40)

As seen from the hierarchical network, clausal constructions have two subtypes: independent (indep-cl) and dependent clauses (dep-cl). All acs belong to this second type of clause. acs (abs-cx) are again classified into two subtypes: augmented (aug-abs-cx) and unaugmented (unaug-abs-cx). Note that, being a subtype of the dependent clause, acs inherit their constructional constraints as modifiers, which can be represented in the following feature-structure format of SBCG (Sign-Based Construction Grammar):Footnote 18

(41) Dependent Clause Construction:

This constructional constraint specifies that, syntactically (syn), the dependent clause (dep-cl) modifies (mod) a finite S denoting the event e1, and requires neither a subject (subj) nor a complement (comps) (both of these have empty lists as their values). Semantically (sem), the construction, denoting the situation e0, is in a dependent relation (dep-rel) with the matrix clause (Se1) that it modifies.

In addition to the constraints in (41) inherited from its superconstruction, the acs carry their own constructional constraints, motivated by the fact that unlike other dependent clauses, acs need to be nonfinite. Consider the following:

(42)

(a) [Since everything blooms], spring is the season.

(b) Spring is the season [when everything blooms].

(43)

(a) *[With John is driving], we won't have a lot of fun.

(b) *[What with John is driving], we won't have a lot of fun.

The subordinate clauses in (42) are finite, but not the acs in (43). This contrast imposes the following constraints on the abs-cxt:

(44) Absolute Construction:

The ac (abs-cxt) thus is required to bear the feature (pred) which is assigned to the nonfinite VP functioning as the head of the nonfinite S, as well as to the AP, PP, or even NP serving as the head of a SC. The construction thus bears the constraint in (44) as well as the ones inherited from its supertypes including the Dependent Construction (dep-cl). This inheritance system, then, can offer us a simple account for unaugmented absolute constructions as well. Consider the following Google Web examples:

(45)

(a) [The bus driver being on strike], we will have to walk to the place.

(b) Old Ivar, [his white head bare], stood holding the horses.

In these unaugmented acs, there is no marker indicating that the nonfinite acs modify the matrix clause. Within the present system, the unaugmented ac, as a subtype of the Absolute Construction (abs-cxt), serves as a nonfinite clause modifying the matrix clause.

As we have noted several times, the key property of augmented acs is the presence of a marker like with, and and what with which combines with a clausal head, as shown in (46):

(46) Augmented Absolute Construction:

The construction has two constituents: a marker and a head clause. The marker bears the feature mrkg (marking) value, while the head clause is predicative, which is in fact inherited from the Absolute Construction. The marker forms a Head-Functor Construction with its predicative clausal head (see Van Eynde Reference Van Eynde and Müller2007; Kim & Sells Reference Kim and Sells2011; Sag Reference Sag, Boas and Sag2012).Footnote 19 The Augmented Absolute Construction has two subtypes:

(47) With Absolute Construction:

(48) What-with Absolute Construction:

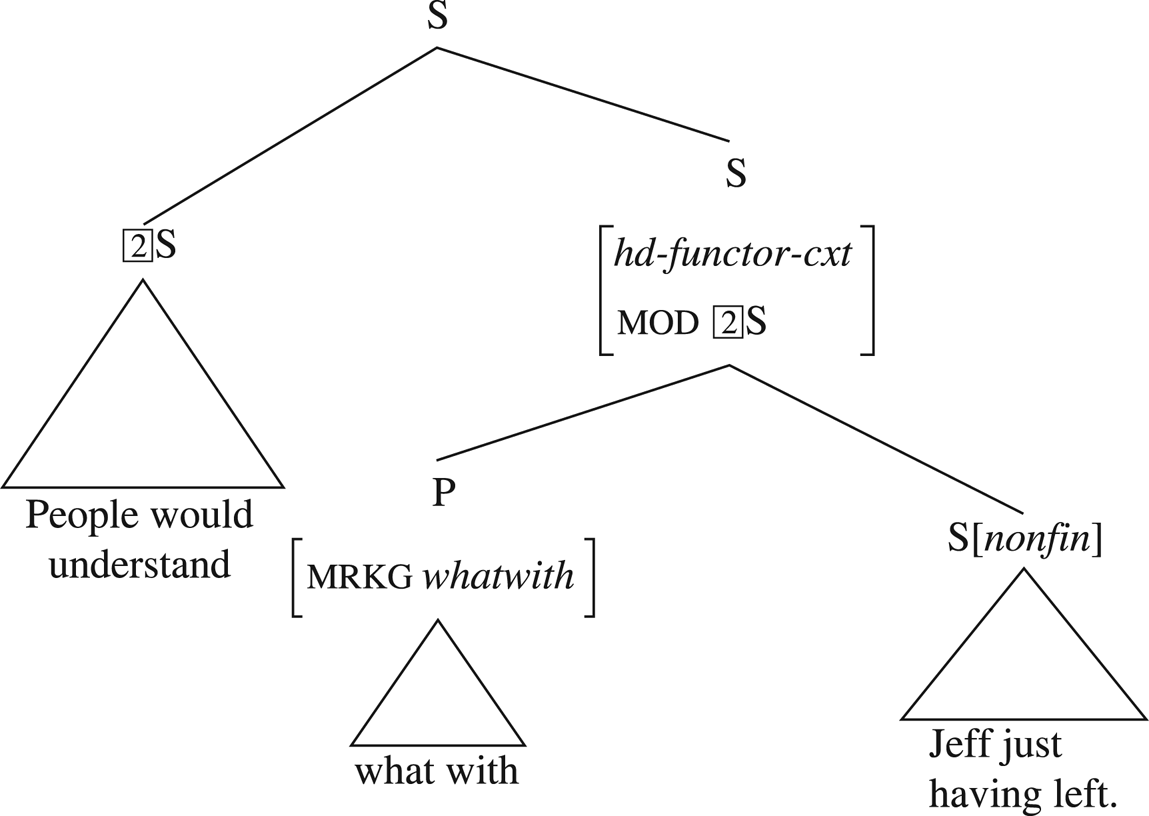

Leaving aside the semantic and pragmatic constraints of the what-with ac for a moment (see (52) below), these constructional constraints imply that the structure for the what-with ac is minimally different from the structure for the with ac with respect to the mrkg value. Consider the following simplified structure for a sentence involving the what-with ac:Footnote 20

(49)

The key motivation for this kind of constructional classification and schematization comes from the generalities as well as the peculiarities of acs in English, which we have discussed so far. Let us consider here again some of the relevant properties. As an adjunct, both the what-with ac, as seen in (6), and with ac, as given in (50), have the distributional freedom to occur at the beginning of the sentence, in the middle or at the end:

(50)

(a) [With you doing all the hard work], he can later steal it for Earth's use. (COHA 1998 FIC)

(b) The vision of the Temple, [with me standing on the highest ledge], was clearly before me. (COHA 1967 NEWS)

(c) I agreed. Couldn't help it, [with her looking at me that way]. (COHA 1991 FIC)

However, the and ac occurs only in non-initial position, as illustrated in (50). This positional restriction allows the and ac to function as an independent sub-construction of the absolute construction.

(51)

(a) They left without a word, and he so sensitive. (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 844)

(b) *And he so sensitive, they left without a word.

In terms of semantics, the what-with ac is much more restricted than other acs, which we have discussed earlier in section 3.3. Past studies have noted that the unaugmented and with augmented clause can be in a wide variety of semantic relations with the matrix clause involved (Kortmann Reference Kortmann1991; van de Pol & Cuyckens Reference van de Pol, Cuyckens, Giacalone, Ramat and Molinelli2013; Todorova Reference Todorova2013). The with ac expresses cause, condition, or concession and simultaneity or anteriority. We have also seen in section 3.3 that the induced meaning relation of the what-with ac is much more restricted than the with ac. We have noted that the licensed meaning relation of the what-with ac is confined to a ‘reason’ relation. The circumstantial what with may also refer to one or more given circumstances of an unspecified set, evidenced by its dominant preference for coordination structures. For instance, the construction, in contrast with other types of acs, allows the semantically unspecified conjunct and all, and everything and another. Such idiosyncratic semantic/pragmatic relations are not linked to any linguistic expression in the ac – the most plausible direction seems to assign these constructional constraints to the construction, as in (52):

(52) What-with Absolute Construction:

The constructional constraints here specify that the complex expression what with functioning as a marker combines with a clausal head. Semantically, it has a reason relation with the matrix clause and pragmatically (contextual information), it evokes the background information such that in addition to the situation of the absolute clause (e0), there are other reasons (non-empty set: neset) that cause the situation (e1) denoted by the matrix clause (see the constraints on the superconstruction dep-cl). Note the main difference between our analysis and that of Felser & Britain (Reference Felser and Britain2007). In our analysis, the meaning of evaluative function is not from the expression what but from the construction. The compositional analysis adopted by Felser & Britain runs into problems when there is no linguistic expression that marks the absolute clause's semantic relation with the matrix clause, as in unaugmented acs. In addition, as noted by van de Pol & Hoffmann (Reference van de Pol and Hoffmann2016), even the augmentor with is now bleached in terms of its meaning. That is, the with ac is used to convey the manner/accompanying situation in early stages of English, but in PDE, it has undergone a grammaticalization process as a semantically bleached absolute marker. This shift also affects the what with construction in which what with also functions as an absolute marker. We have seen that the evidence from increased syntactic productivity and generalization – as well as restricted compositionality – provides evidence for this grammatical shift.

One issue that we have not yet discussed is how to license the unlike coordination in the what-with ac. The categorically unlike coordination is rarely allowed in the with ac:Footnote 21

(53) *He has had a bad time of it lately, with [the Rainbow being banned] and [no money].

One way to account for the unlike coordination in the what-with ac is to take it as the coordination of ‘core’ expressions whose subtypes are nominal and verbal.Footnote 22 Kim & Sag (Reference Kim, Sag and Müller2005) note a generalization that verbs allowing a choice between a clausal complement and an NP object will license object extraposition:

(54)

(a) They didn't even mention his latest promotion/that he was promoted recently.

(b) They demanded justice/that he should leave.

(c) He said many things/that I was not the person he was looking for.

(55)

(a) They never mentioned it to the candidate that the job was poorly paid.

(b) They demand it of our employees that they wear a tie.

(c) He wouldn't dare say it that I am not the right man for the job.

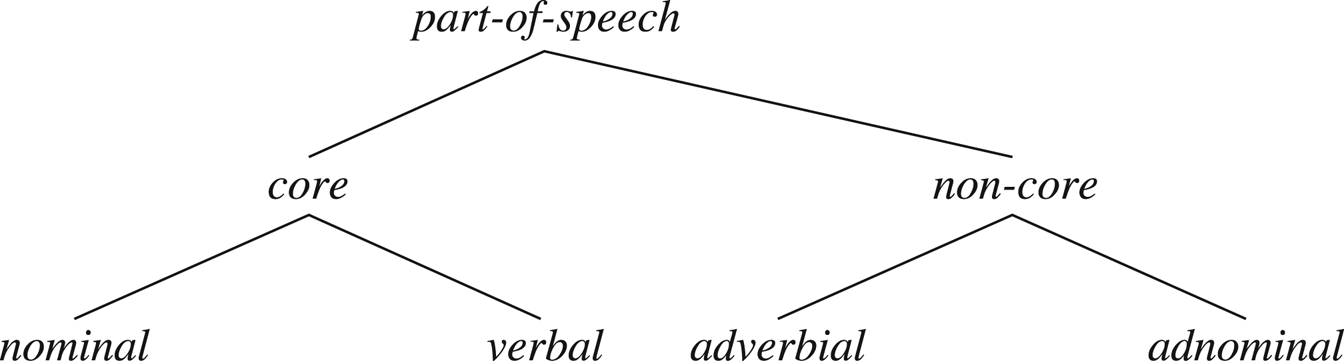

As a way of reflecting this generalization, Kim & Sag (Reference Kim, Sag and Müller2005) have suggested the following classification of English lexical categories:

(56)

The hierarchy implies that nominal and verbal are both subtypes of the category core.Footnote 23 Given this, we could allow the coordination of two nominal or core expressions as in (57), but not the coordination of core and noncore expressions.

(57)

(a) but what with [nominal the coffee] and [nominal being scared out of her wits besides], she couldn't possibly sleep. (COHA 1957 FIC)

(b) but what with [core her relations here], and [core her bein’ known], she didn't take. (COHA 1879 FIC)

Of course, this kind of high-level unlike coordination occurs only in the what-with ac, not in the with ac.Footnote 24 The flexibility of unlike coordination in the construction seems to be linked to the property of the marking what with, which used to be a prepositional-like marker but which later added sentential properties. The grammar then can allow the complement of what with to carry the core feature, which licenses even the unlike coordination.

4.3 A diachronic perspective: grammatical constructionalization

The corpus data show us that the what-with ac displays compositional as well as idiosyncratic properties as a subtype of the absolute constructions. We have discussed the fact that there are some interesting changes in the constructional properties over time, e.g. extending the available complement type to nonfinite Ss and the semantic prosody with positive senses. The semantic/pragmatic properties seem to be fairly constrained, with the predominant use of the construction in the ‘fiction’ genre – which tries to offer ‘factual narratives’ of the imaginative world to the prospective readers.

As noted by Kortmann (Reference Kortmann1991: 26) and van de Pol & Hoffmann (Reference van de Pol and Hoffmann2016), it appears that in earlier stages of English, there were practically no limitations on the possible inventory of augmentors for the ac. However, in PDE, this inventory has been reduced to only with, and and what with. In addition to this kind of change, the acs (in particular the what-with ac) have undergone constructional grammaticalization (Trousdale Reference Trousdale, Trousdale and Gisborne2008; van de Pol & Hoffmann Reference van de Pol and Hoffmann2016). As noted by Traugott (Reference Traugott, Eckardt, Jäger and Veenstra2008), Traugott & Trousdale (Reference Traugott, Trousdale, Traugott and Trousdale2010) and Hilpert (Reference Hilpert2013: 8), grammaticalization is a process in which there is a development or change of form–meaning pairings. The changes are associated with three key parameters: schematicity, productivity and compositionality (Trousdale Reference Trousdale, Trousdale and Gisborne2008; Traugott & Trousdale Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013; 13). Consistent with what van de Pol & Hoffmann (Reference van de Pol and Hoffmann2016) observe for the with ac and Trousdale (Reference Trousdale2012) for the what-with ac, our data from synchronic and diachronic corpora also indicate that the what-with ac has undergone the process of grammaticalization.

The first grammaticalization property that we have observed in the what-with ac is an increase in schematicity. Schematicity, a taxonomic generalization, concerns a process of abstract categorization. The what-with ac has become quite schematized in syntactic and semantic-pragmatic respects. As noted before, according to Traugott (Reference Traugott, Eckardt, Jäger and Veenstra2008: 236), constructions can be schematized with at least three different levels: macro-, meso-and micro-constructions. Macro-constructions are constructions at a fairly abstract level; they function as umbrella constructions that comprise several different lower-level schemas (see also Hilpert Reference Hilpert2013). With our system, absolute constructions could be viewed as macro-constructions. The next lower-level constructions are meso-constructions like the English possessive construction that unites the English genitives, the s-genitive and the of-genitive (Trousdale Reference Trousdale, Trousdale and Gisborne2008: 170). In the present system, the augmented absolute construction could be a good candidate for the meso-construction in the sense that it is a conglomerate of lower-level constructions like with ac and what-with ac. These two function as the lowest of the three levels, micro-construction, which is a formally specified pattern. The micro-construction is then instantiated in language use by constructs, many of which we could identify from the attested examples.

One important advantage of looking at grammaticalization processes from the schematic view of CxG is that we can take into consideration the form and the meaning of the construction as a whole, not separately. Within the perspective of CxG, grammaticalization has affected both form and meaning. In particular, as we have seen, the construction has undergone the following grammaticalization process:

(58) Development of the what-with ac

What this implies is that in terms of the form, the complement type of the construction has been extended from simple NPs to nominal expressions, which by definition include not only NPs but also nonfinite clausal elements that can function as nominal expressions. The construction has undergone the process of semantic and pragmatic grammaticalization. In terms of its semantic functions, it is now restricted to a reason relation, while in terms of pragmatic (contextual) information, the construction expands its uses from a negative to a positive or neutral evaluation of the matrix clause. As a micro-construction, the what-with ac thus obtains a sui generis status by extending its possible complement type and pragmatic prosody, while integrating itself with its meso- as well as macro-constructions.

As noted by Langacker (Reference Langacker, Heine and Narrog2011), Traugott & Trousdale (Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 13) and van de Pol & Hoffmann (Reference van de Pol and Hoffmann2016), the increase in schematicity is in general realized as an increase in semantic generality. The main semantic/pragmatic change that we have noted from the corpus data is that in the nineteenth century, the what-with ac is typically used to offer a reason for the ‘negative’ situation denoted by the matrix clause:

(59)

(a) [What with discharging such numberless debts and satisfying your prodigality], nearly all is swallowed. (COHA 1836 FIC)

(b) He has had a tough morning of it, [what with the heat and the hills]. (COHA 1824 FIC)

But in PDE, this negative implication has been extended to include positive as well as neutral implications, as represented in (58). The corpus data in the twentieth century often yield examples like the following:

(60)

(a) It's easy to leapfrog this month, [what with Nintendo delivering The Legend of Zeld]. (COCA 2017 MAG)

(b) This may be one of the best pairings of the fall, [what with former Doobie Brother McDonald's enigmatic voice and Cleveland's own Grammy winner]. (COCA 2017 NEWS)

In such examples, the matrix clause that is modified by the absolute clause does not denote a negative state. That is, it has no negative implication. This kind of change in the what-with ac, which relaxes the semantic-pragmatic constraints of the construction, has also been noted by Felser & Britain (Reference Felser and Britain2007) as well as by Trousdale (Reference Trousdale2012).

The second property of a grammaticalization process is an increase in syntactic productivity. We have identified evidence of the syntactic expansion: the complement type has been extended from NPs to nonfinite Ss as well as to verbless SCs:

(61)

(a) it was the hottest work, [what with [NP the weather]]. (COHA 1835 FIC)

(b) They made her too much work, for [what with [VP opening the dining-room and bringing out the silver]], (COHA 1871 FIC)

(c) [What with [S my being my father's son]], and all that, my father is going to suffer. (COHA 1896 FIC)

(d) [what with [SC his Auntie Helena's hand at one extremity] and [SC my boot at the other]], he was strained in his conversation, (COHA 1913 FIC)

A similar observation has also been made by Trousdale (Reference Trousdale2012). In the earlier time period (1710-80) of the corpus CLMETEV, the attested complement type is only simple NPs or coordinated NPs.

The expansion of possible complement types, as represented in (58), also accompanies the flexibility of coordination types. We have seen that the what-with ac is peculiar in that it allows a variety of unlike coordinations. The diachronic and synchronic data have also shown us the third characteristic of constructional grammaticalization: a decrease in compositionality. As pointed out by Kortmann (Reference Kortmann1991: 114) and others, the unaugmented acs are semantically indeterminate: their meaning relations with the matrix clause are context-dependent. However, the what-with ac only induces a reason relation. This decrease in compositionality relates to the increased idiomaticity of the construction. For instance, the meaning of ‘reason’ can hardly be predictable from any expression in the construction. As noted by one reviewer, one could suggest that the meaning of ‘reason’ is tied to what. But note that the with ac without what or even the unaugmented ac with no augmentors can have the meaning of ‘reason’ (data from van de Pol & Cuyckens Reference van de Pol, Cuyckens, Giacalone, Ramat and Molinelli2013):

(62)

(a) With the traffic thickening and the street lights coming on, it would be after four when I got there.

(b) Shifty-Eyes and Pointy-Beard were in the back, of course, the third cousin having disappeared with the Capri.

This implies, as we have pointed out in this section, that the meaning relation of an absolute construction with its matrix clause is not compositional, but rather indeterminate and context-dependent.

The observations that we have made so far, which also support the points made by Felser & Britain (Reference Felser and Britain2007), Trousdale (Reference Trousdale2012) and van de Pol & Hoffmann (Reference van de Pol and Hoffmann2016), indicate that the what-with ac, though less frequently used than with augmented acs or unaugmented acs, has undergone a grammaticalization process of micro-changes at several linguistic levels. In addition, it has obtained its status as an independent construction with a unique form–function mapping. The CxG explanation we have presented here allows us to look at how the construction is linked to other related constructions and what makes it an independent construction.

5 Conclusion

Throughout this article, we have seen that the uses of the what-with ac display quite distinctive properties, while sharing some properties with standard absolute constructions.

We have studied more than 5,600 tokens of the construction, which we extracted from the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA; 1810–2009), and supplemented by Early English Books Online (EEBO; 1470s–1690s) and the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA; 1990–2017). With this wealth of data, we have examined the synchronic and diachronic properties of the what-with ac in much more detail than has been done in previous studies (e.g. Felser & Britain Reference Felser and Britain2007; Trousdale Reference Trousdale2012). Our corpus data provide evidence for at least three diachronic shifts during the last 150–200 years, all of which suggests that the construction has undergone a process of constructional grammaticalization during this time. The first of these changes is an increase in schematicity. Whereas most examples of the construction in the 1800s had a negative meaning, over time there has been an increase in neutral and especially positive use. Second, there has been an increase in syntactic productivity, as the complement type has been extended from simple NPs to nonfinite clausal elements. Third, there has been a decrease in compositionality and a corresponding increase in idiomaticity.

As a way of accounting for both the diachronic and synchronic properties that we have observed here, we have adopted a simplified Construction Grammar approach. This approach, in which language-particular generalizations are expressed in terms of inheritance network systems, has allowed us to capture the distinctive properties of the construction itself, as well as properties that are shared with related constructions.

In terms of tying the theory and the data together, this model of inheritances has allowed us to consider how changes with what-with ac are related to diachronic shifts with other absolute constructions. In addition, a Construction Grammar approach, where all levels of linguistic description are understood to involve pairings of form with semantic or discourse function, accounts for the gradual changes that the construction has undergone in a streamlined way.