Few studies have identified coniferous fossil woods in Mexico. The only known taxa are Araucarioxylon mexicanum of the Rosario Formation (Lower Jurassic) of the Mixteca Alta region in Oaxaca described by Wieland (Reference Wieland1914–1916), Brachyoxylon sp. of the Nogal Unit (Lower Cretaceous) in Lampazos Sonora, and Podocarpoxylon sp. and Taxodioxylon sp. from the Olmos Formation (Upper Cretaceous) in Coahuila (Cevallos-Ferriz Reference Cevallos-Ferriz1992). There are other reports of coniferous fossil woods with anatomical descriptions, but they remain essentially unpublished. For instance, Castañeda Posadas (Reference Castañeda Posadas2004) identified a member of Podocarpus and suggested the presence of Taxus in Miocene rocks of the Tlaxcala Block in Panotla, Tlaxcala; Ortega Chávez (Reference Ortega Chávez2013) described some woods with characteristics of Agathoxylon Hartig, and others with attributes of Podocarpoxylon Gothan and Phyllocladoxylon Gothan, from the Tecomazúchil Formation (Middle Jurassic), Oaxaca; and Grajeda Cruz (Reference Grajeda Cruz2015) described two woods from the Otlaltepec Formation (Middle Jurassic) and five woods of the Magdalena Formation (Lower Cretaceous) in Puebla – fossil material that seems to represent members of Agathoxylon.

Other fossil conifers from the Olmos (Upper Cretaceous) Formation, northern Mexico, include Aachenia knoblochi (Weber Reference Weber1975), Kobalostrobus olmosensis (Serlin et al. Reference Serlin, Delevoryas and Weber1980), Raritania sp. cf. R. gracilis (Newberry) Hollick & Jeffrey, Brachyphylum macrocarpum Newberry, Sequoia cuneata Newberry and Geinitzia sp. Endlicher (Weber Reference Weber1980). From the Cabullona Group in Sonora, branch compressions with acicular leaves associated with an ovule cone have been tentatively assigned to Pinus (Huerta-Vergara et al. Reference Huerta-Vergara, Calvilllo-Canadell, Cevallos-Ferriz and Silva-Pineda2013; Huerta-Vergara Reference Huerta-Vergara2014).

From southern Mexico, reproductive and vegetative structures collected in the Sierra Madre Formation (Lower Cretaceous), Chiapas, have recently been studied and related to Pinaceae (Huerta-Vergara et al. Reference Huerta-Vergara, Calvilllo-Canadell, Cevallos-Ferriz and Silva-Pineda2013; Huerta-Vergara Reference Huerta-Vergara2014), Cupressaceae (González-Ramírez et al. Reference González-Ramírez, Calvillo-Canadell and Cevallos-Ferriz2013) and a cone in organic connection with branches that resemble that of Cheirolepidiaceae (Huerta-Vergara & Cevallos-Ferriz Reference Huerta-Vergara, Cevallos-Ferriz, Boura, Broutin, Chabard, Decombeix, Galtier, Gand, Jondot and Meyer-Berthaud2015). However, they have a mosaic of characters that suggest they may represent extinct taxa, and further collections are needed to achieve a better taxonomic understanding.

The scarcity of well-documented fossil conifers, despite their frequent occurrence in Mesozoic sedimentary rocks, from several localities in Mexico, highlights the importance of studying the wood palaeoflora that once grew in what are now the states of Chiapas (Todos Santos Formation/Upper Jurassic), Sonora (Packard Shale/Upper Cretaceous) and Coahuila (Las Encinas Formation/Lower Palaeocene). The report of some of these new plants will further document biodiversity during the Mesozoic and Palaeogene in low-latitude North America.

1. Material and methods

The material consisted of six wood pieces: four specimens collected by the authors near the town of Porvenir Jericó, central Chiapas (Fig. 1, Location 1); a specimen collected by René Hernández Rivera in Fronteras, northeastern Sonora (Fig. 1, Location 2); and a specimen collected by Francisco Vega Vera in the Parras Basin, southern Coahuila (Fig. 1, Location 3).

Figure 1 Localities where fossil wood was collected.

From these specimens, the three standard wood planes were obtained and, using the conventional thin-section technique, 126 slides were prepared. Observation of the anatomical features was made with a Carl Zeiss Primo Star optical microscope. The recognition of the anatomical characters and terminology for wood description follows IAWA (2004), García et al. (Reference García Esteban, de Palacios de Palacios, Guindeo Casasús, García Esteban, Lázaro Durán, Gonzáles Fernández, Rodríguez Labrador, Fernández García, Bodadilla Maldonado and Camacho Ayala2002) and Barefoot & Hankins (Reference Barefoot and Hankins1982). A total of 150 measurements were obtained to calculate the average and minimum and maximum values for each qualitative character. The observations and measurements of the characters were made based on the early wood. Microphotographs were obtained with a Canon PowerShot A640 camera. The taxonomic identification is based on comparisons with the wood of extant and fossil species informed by literature such as Greguss (Reference Greguss1955), García et al. (Reference García Esteban, de Palacios de Palacios, Guindeo Casasús, García Esteban, Lázaro Durán, Gonzáles Fernández, Rodríguez Labrador, Fernández García, Bodadilla Maldonado and Camacho Ayala2002, Reference García Esteban, de Palacios de Palacios, Guindeo Casasús and Fernández García2004), Bamford & Philippe (Reference Bamford and Philippe2001) and Philippe & Bamford (Reference Philippe and Bamford2008).

1.1. Locality 1. Porvenir Jericó, Chiapas

Located south of the town of Porvenir Jericó, in the municipality of Villa Corzo, Chiapas, at [16°15′37″N, 92°56′27″W] (Fig. 1). The material was collected in the northwestern arm of the Belisario Domínguez dam, where sedimentary rocks of the Todos Santos Formation outcrop (Godínez-Urban Reference Godínez-Urban2009). This formation was defined by Sapper in Guatemala (Sánchez-Montes de Oca Reference Sánchez-Montes de Oca1969) and has been identified in Mexico as a thin band of alternating polymictic conglomerates, sandstones, mudstones, volcanic rocks with a NW–SE orientation that outcrops from northern Oaxaca to the border with Guatemala, crossing Chiapas (Godínez-Urban Reference Godínez-Urban2009). Its thickness varies from place to place, but in Chiapas at Cerro el Encantado it measures 825m (Richards Reference Richards1963). According to Godínez-Urban et al. (Reference Godínez-Urban, Lawton, Molina Garza, Iriondo, Weber and López-Martínez2011), two members are distinguishable; in ascending order, they are El Diamante and Jericó. In general, its lithology suggests continental deposits of alluvial fans, fluvial systems and lacustrine environments (Blair Reference Blair1987). The Todos Santos Formation in the locality where the fossil material was collected is closely related to the La Silla Formation (Lower–Middle Jurassic) and underlies the Sierra Madre Formation (Lower Cretaceous), but near Cintalapa, it transitionally underlies the San Ricardo Formation of the Kimmeridgian-Thithonian (Castro-Mora et al. Reference Castro-Mora, Schlaepfer and Rodríguez1975; Alencáster Reference Alencáster1977; Godínez-Urban Reference Godínez-Urban2009). Its age varies as it extends laterally; however, volcanic rocks from its base (Castro-Mora et al. Reference Castro-Mora, Schlaepfer and Rodríguez1975) and rocks of the La Silla Formation and of the Member Diamante suggest an age of 170±3 to 148±6Ma, Middle to Upper Jurassic (Godínez-Urban et al. Reference Godínez-Urban, Lawton, Molina Garza, Iriondo, Weber and López-Martínez2011). As for the palaeontology, reports of Idoceras sp., Waagenia sp. and Halobia sp. (Müllerried Reference Müllerried1936), as well as leaf remains and siliceous woods (Müllerried Reference Müllerried1936, 1957; Blair Reference Blair1987), and bioclastic remains of brachiopods, foraminifera and bivalves (Blair Reference Blair1988) are also known from these outcrops.

1.2. Locality 2. Fronteras, Sonora

The locality is one kilometre east of the town of Fronteras, Municipality of Fronteras, northeast of Sonora, at [30°53′17″N, 109°32′15″W] (Fig. 1). René Hernández Rivera, of the Geology Institute, UNAM, collected the fossil material in 2012. The fossil specimen was recovered from a sandy stratum of the Packard Shale Formation (Hernández Rivera, pers. comm. 2013). This is part of the Cabullona Group where it represents the penultimate formation of the group; it overlies the Camas Sandstone Formation and underlies the Lomas Coloradas Formation. The Packard Shale Formation measures 1070m in its type section and is subdivided into eight members whose dominant lithology consists of finely laminated shale and limolite, massive lodolite and laminar, and wavy and cross-stratified sandstone (Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Kues, Gonzáles-León, Jacques-Ayala, Gonzáles-León and Roldán-Quintana1995). More detail of the lithology of all the members is given in Gonzáles-León & Lawton (Reference González-León, Lawton, Jacques-Ayala, Gonzáles-León and Roldán-Quintana1995). This formation represents deltaic and lake deposits whose sediments are intertwined with those of the El Cemento Conglomerate Formation; a unit laterally equivalent to the Packard Shale Formation and Lomas Coloradas north of the Cabullona basin (Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Kues, Gonzáles-León, Jacques-Ayala, Gonzáles-León and Roldán-Quintana1995). From the Packard Shale Formation, fossils of gastropods and freshwater pelecypods, vertebrates, leafy plant remains (Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Kues, Gonzáles-León, Jacques-Ayala, Gonzáles-León and Roldán-Quintana1995) and dinosaur footprints (Duarte Bigurra Reference Duarte Bigurra2013) have been identified. The age of the Group, based on its stratigraphy and the extensive fossil record, has been proposed as Santonian to Late Maastrichtian (Gonzáles-León & Lawton Reference González-León, Lawton, Jacques-Ayala, Gonzáles-León and Roldán-Quintana1995; Villanueva-Amadoz et al. Reference Villanueva-Amadoz, Gónzales-León, Solari, Calvillo-Canadell, Cevallos-Ferriz, Rocha, Pais, Kullberg and Finney2015).

1.3. Locality 3. Parras Basin, Coahuila

This is located north of the city of Saltillo, Coahuila, at [25°48′45.5″N, 101°08′58.2″W] (Fig. 1). Francisco Vega Vera, Geology Institute, UNAM, collected the silicified wood in 2013. The fossil material was recovered from the Cerro San Francisco in a stratum corresponding to the upper part of the Las Encinas Formation (Palaeocene) and close to federal highway 47 Saltillo–Castaños. The Las Encinas Formation was defined by Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Weidie, Boyd, Forde and Lewis1962) as part of the Difunta Group, which is composed of seven formations in the Parras basin, in ascending order as follows: Cerro del Pueblo, Cerro Huerta, Cañón de Tule, Las Imágenes, Cerro Grande, Las Encinas and Rancho Nuevo. It extends from eastern Torreón (Coahuila) to the northwest of Monterrey (Nuevo Leon) and south of Monclova (Coahuila) (Vega-Vera et al. Reference Vega-Vera, Mitre-Salazar and Martínez-Hernández1989). Its thickness varies from 82 to 136m (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Weidie, Boyd, Forde and Lewis1962), and its lithology consists of red calcareous limolites, shallow-grained mudstones, red calcareous sandstones, red and green mudstones, lodolites and medium-to-large-grain sandstones (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Weidie, Boyd, Forde and Lewis1962). Its fossil record includes, towards its top, freshwater gastropods like Vivipaparus mcbridei, V. cf. V. Leidyi, V. cf. V. raynoldsanus and Melenatrica cf. M. ypresiana (Perrilliat et al. Reference Perrilliat, Vega, Espinosa and Naranjo-García2008), as well as Ostrea (Ostrea) parrensis (Vega et al. Reference Vega, Perrilliat, Mitre-Salazar, Bartolini, Wilson and Lawton1999) and transported siliceous woods of large dimensions (Vega-Vera, pers. comm. 2013). Its fossil and lithology content suggest deposits of coastal and deltaic plains (McBride et al. Reference McBride, Weidie, Wolleben and Laudon1974). Based on its stratigraphic position and fossil record, its age ranges from the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) to the Lower Palaeocene.

2. Systematic descriptions

Family Araucariaceae

Genus Agathoxylon Hartig, 1848

Agathoxylon cordaianum Hartig, 1848

Agathoxylon gilii sp. nov. Ríos-Santos & Cevallos-Ferriz

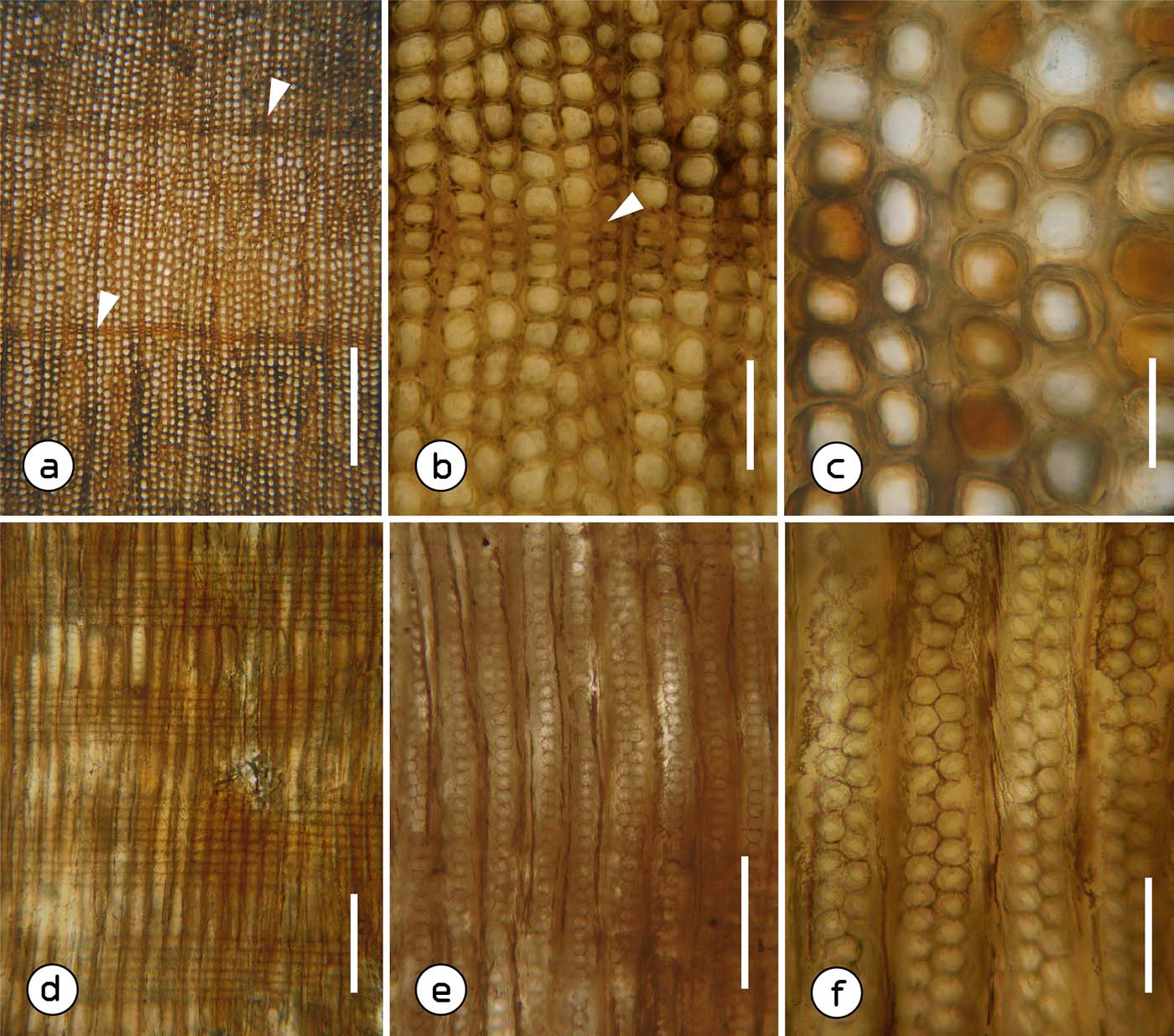

Figure 2 Agathoxylon gilii sp. nov. TR: (a) cross-section with distinct growth rings, arrows signal late wood; (b) close-up of the late wood (arrow) of a growth ring; (c) tracheids with mainly rounded contours. RL: (d) radial section, general view; (e) tracheids with uniseriate and biseriate bordered pits; (f) biseriate bordered pits with alternate arrangement, some with polygonal outline. Scale bars=580μm (a); 160μm (b); 80μm (c, f); 250μm (d); 190μm (e). Abbreviations: TR = transverse section; RL = radial longitudinal section.

Figure 3 Agathoxylon gilii sp. nov. RL: (a) biseriate bordered pits with opposite arrangement (arrow) and circular outlines; (b) circular openings of the bordered pits (arrows); (c) ray constituted only by parenchyma cells; (d) ray parenchyma cells with smooth horizontal walls (arrows); (e) ray parenchymal cells with smooth end walls (arrow); (f) cross-field pitting of araucarioid type; (g) close-up of pits on cross-fields, arrow points to the opening of one of them. TA: (h) tangential section with uniseriate rays; (i) ray cells with circular to oval contours, arrow points to a partially biseriate ray. Scale bars=80μm (a); 30μm (b); 100μm (c); 35μm (d–f); 10μm (g); 400μm (h); 170μm (i). Abbreviations: RL = radial longitudinal section; TA = tangential longitudinal section.

Location. Porvenir Jericó, Chiapas.

Stratigraphic horizon. Jericó Member of the Todos Santos Formation.

Age. Upper Jurassic.

Depository. Paleobotanical Collection of the Museum of Paleontology, Institute of Geology, UNAM.

Number of examined specimens. Two – IGM-CHP1 and IGM-CHP2.

Thin sections. Thirty-three in total (IGM-LPB-CHP1: 101–114; IGM-LPB-CHP2: 201–219).

Holotype. IGM-LPB-CHP1: 101–114.

Etymology. The specific epithet recognises M. Sc. Javier Avendaño Gil, a member of the Paleontological Museum ‘Eliseo Palacios Aguilera' of Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, for guiding us to the fossiliferous locality.

Diagnosis. Growth rings distinct; rounded tracheids in cross section with radial diameter of 56 (44–67)μm; tracheid pitting in the radial walls uniseriate and biseriate, with araucarian arrangement, occasionally opposite; bordered pits with rounded and polygonal outlines and diameter of 19 (15–23)μm; uniseriate, rarely partially biseriate rays, with 1–15 (23) cells high, composed of exclusively radial parenchyma; radial parenchyma cells with smooth walls; cross-fields pitting of araucarioid-type, with five (2–8) pits; resin canals, radial tracheids, axial parenchyma and bordered pits on the tangential walls of the tracheids absent.

Description. Fragments of secondary xylem at most 5cm in diameter by 10cm in length. Growth rings are distinct (Fig. 2a), though sometimes they are difficult to detect because late wood is composed of up to three rows of tracheids (Fig. 2b). The tracheids are rounded in cross section (Fig. 2c). The early wood tracheids have a wall thickness of 8 (4–13)μm and radial and tangential diameter of 56 (44–67)μm and 56.3 (35–79)μm, respectively. Tracheid pitting in radial walls is uniseriate to biseriate, always contiguous (Fig. 2e, f) and when the bordered pits are arranged in two series their arrangement is alternate (Fig. 2f) and occasionally opposite (Fig. 3a). The outlines of the bordered pits are polygonal and circular (Figs 2f, 3a), with a diameter of 19 (15–23)μm, while that of the circular apertures is 5 (4–7)μm (Fig. 3b). On average, this wood has 400 tracheids/mm2. The rays are uniseriate to occasionally partially biseriate (Fig. 3h, i), constituted by parenchyma cells (Figs 2d, 3c) with smooth horizontal and end walls (Fig. 3d, e). These cells measure 24.9 (19–35)μm in height and have circular outlines in tangential section (Fig. 3i). Rays are 1–15 (23) cells high and have a frequency of 5 rays/mm. Cross-field pitting are araucarioid-type, with five (2–8) pits whose diameter is of 9 (7–12)μm (Fig. 3f, g).

Agathoxylon jericoense sp. nov. Ríos-Santos & Cevallos-Ferriz

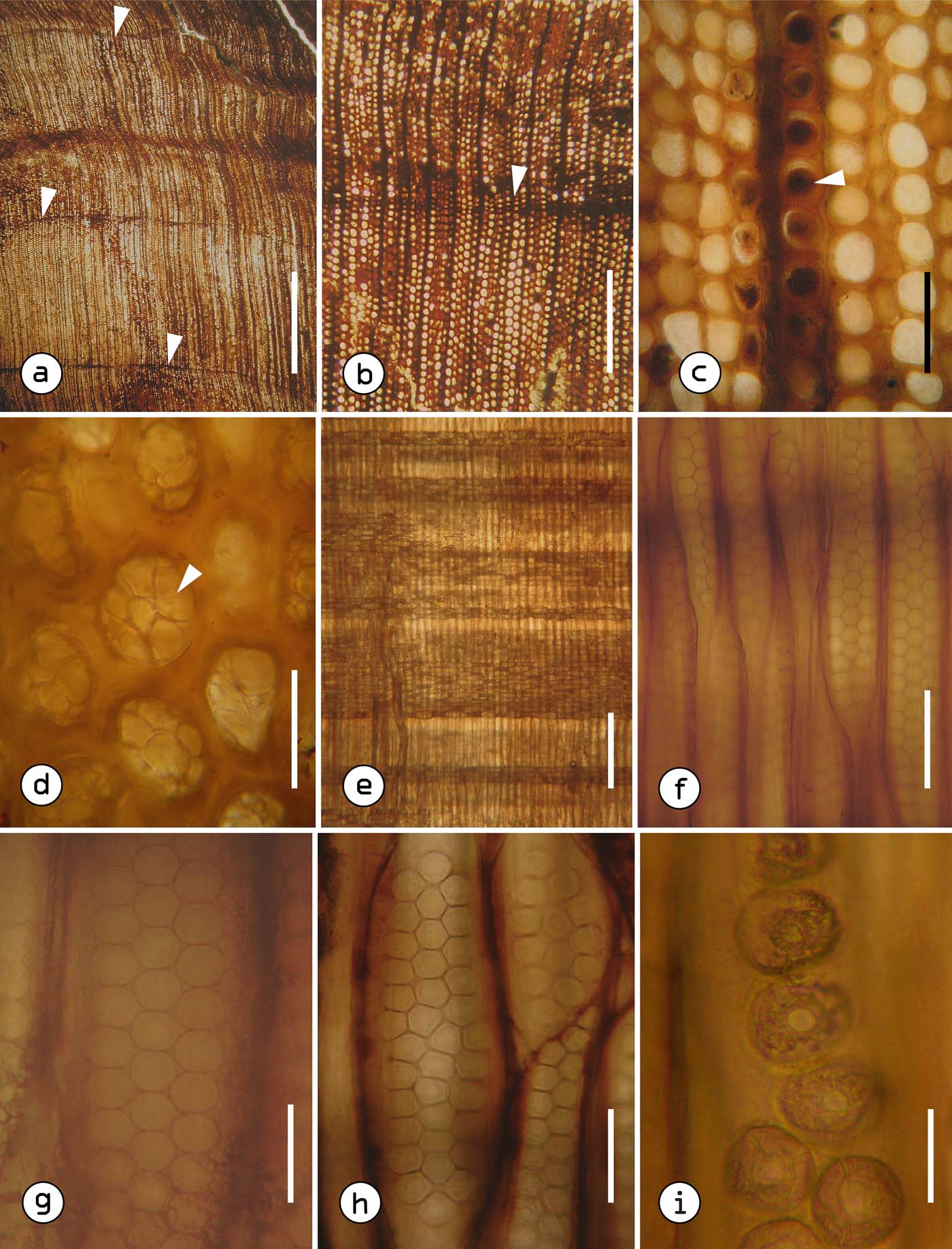

Figure 4 Agathoxylon jericoense sp. nov. TR: (a) cross-section with distinct growth rings, arrows indicate late wood; (b) narrow late wood shown by arrow; (c) tracheids with mainly rounded contours, arrow points to a tracheid with resin plug; (d) tracheids with tyloses (arrow). RL: (e) general view of a radial section; (f) tracheids with biseriate and triseriate bordered pits with alternate arrangement; (g) bordered pits with circular outline; (h) bordered pits with polygonal outline; (i) bordered pits with circular openings. Scale bars=5mm (a); 520μm (b); 100μm (c); 50μm (d, h); 560μm (e); 80μm (f); 40μm (g); 15μm (i). Abbreviations: TR = transverse section; RL = radial longitudinal section.

Figure 5 Agathoxylon jericoense sp. nov. RL: (a) tracheids with tyloses (arrow); (b) ray consisting exclusively of parenchymal cells; (c) ray parenchyma with smooth horizontal walls (arrows) – in the upper part, a parenchyma cell with a dark content; (d) ray parenchyma with smooth end walls (arrows); (e) general view of cross-field pitting, araucarioid-type; (f) close-up of the pits of cross-fields. TA: (g) tangential section predominantly uniseriate rays; (h) tracheids with resin plugs close to rays (white arrows), partially biseriate ray (black arrow); (i) ray parenchyma cells with oval outline and some with dark contents (black arrow), close-up of the resin plugs near to rays (white arrows). Scale bars=65μm (a); 310μm (b); 30μm (c–e); 25μm (f); 215μm (g); 215μm (h); 60μm (i). Abbreviations: RL = radial longitudinal section; TA = tangential longitudinal section.

Location. Porvenir Jericó, Chiapas.

Stratigraphic horizon. Upper member of the Todos Santos Formation.

Age. Upper Jurassic.

Number of examined specimens. Two – IGM-CHP4 and IGM-CHP5.

Thin sections. Thirty-seven in total (IGM-LPB-CHP4: 401–422; IGM-LPB-CHP5: 501–515).

Holotype. IGM-LPB-CHP4: 401–422.

Etymology. The specific epithet refers to the town of Porvenir Jericó, the closest populated area to the collection site.

Diagnosis. Growth rings distinct; rounded tracheids in cross section with radial diameter of 46.9 (32–63)μm; tracheids with resin plugs and tyloses; tracheid pitting in the radial walls are uniseriate to tetraseriate with typical araucarian arrangement; the bordered pits with circular to polygonal outline and diameter of 15.8 (13–19)μm on the radial walls of the tracheids; uniseriate to partially biseriate rays, 1–25 (39) cells high, composed of parenchymal cells; radial parenchyma cells with smooth walls and resinous contents; cross-field pitting of araucarioid-type, with seven (3–12) pits per field; resin canals, radial tracheids, axial parenchyma and bordered pits on the tangential walls of the tracheids absent.

Description. Two fragments of secondary xylem not more than 7cm in diameter and 10cm length. Growth rings are distinct, but are sometimes difficult to detect (Fig. 4a). Late wood consists of three to four rows of tracheids (Fig. 4b). Tracheids in cross section have rounded, occasionally polygonal, outlines (Fig. 4c) with sporadic intercellular spaces. The early wood tracheids have a wall thickness of 5.3 (3–8)μm, and radial and tangential diameters of 46.9 (32–63)μm and 42.2 (30–53)μm, respectively. These cells have uniseriate to tetraseriate araucaroid bordered pits in their radial walls, but mostly biseriate and triseriate ones (Fig. 4f). Their outlines are circular to polygonal (Fig. 4g, h), and have a diameter of 15.8 (13–19)μm, while the apertures are circular with an average diameter of 4μm (Fig. 4i). In some areas, tracheids have tyloses (Figs 4d, 5a) or resinous contents near the rays (Figs 4c, 5h, i). On average, these woods have 670 tracheids/mm2. Rays are uniseriate (Fig. 5g) to partially biseriate (Fig. 5h) and are constituted only by radial parenchyma (Fig. 5b). Radial parenchyma cells have thin and smooth horizontal (Fig. 5c) and end walls (Fig. 5d), occasionally resinous contents similar to those of tracheids (Reference Barefoot and HankinsFig. 5c, i), height of 27.6 (18–40)μm and oval outlines in tangential section (Fig. 5i). Rays are 1–25 (39) cells high and have a frequency of 7 (5–10)rays/mm. Cross-field pitting of araucarioid-type, with seven (3–12) pits whose diameter is of 7 (5–10)μm (Fig. 5e, f).

Agathoxylon parrensis sp. nov. Ríos-Santos & Cevallos-Ferriz

Figure 6 Agathoxylon parrensis sp. nov. TR: (a) general view of a cross-section, arrows indicate late wood areas of two growth rings; (b) late wood composed of a few rows of tracheids (arrow); (c) tracheids with rounded outline. RL: (d) general view of a radial section; (e) rays consisting exclusively of parenchymal cells; (f) tracheids with predominantly uniseriate and araucarioid bordered pits; (g) bordered pits with rounded outline; (h) alternate arrangement of biseriate bordered pits; (i) bordered pits with circular to oval openings. Scale bars=3.8mm (a); 550μm (b); 90μm (c); 225μm (d); 150μm (e); 180μm (f); 60μm (g, h); 40μm (i). Abbreviations: TR = tranverse section; RL = radial longitudinal section.

Figure 7 Agathoxylon parrensis sp. nov. RL: (a) ray parenchyma cells with smooth horizontal walls (arrows); (b) radial parenchyma cells with smooth end walls (arrows); (c) araucarioid cross-field pitting (arrows); (d) cross-field with four pits. TA: (e) general view of a tangential section with uniseriate rays; (f) close-up of a partially biseriate ray. Scale bars=25μm (a, c); 38μm (b); 18μm (d); 200μm (e); 75μm (f). Abbreviations: RL = radial longitudinal section; TA = tangential longitudinal section.

Location. Cuenca de Parras, Coahuila.

Stratigraphic horizon. Upper section of the Las Encinas Formation.

Age. Palaeocene.

Number of examined specimens. One – IGM-COA1.

Thin sections. 32 (IGM-LPB-COA1: 101–132).

Holotype. IGM-LPB-COA1: 101–132.

Etymology. The specific epithet makes reference to the Parras Basin.

Diagnosis. Growth rings distinct; rounded tracheids in cross section with radial diameter of 46.3 (31–65)μm; tracheid pitting predominantly uniseriate, rarely biseriate, with typical araucarian arrangement, the bordered pits with rounded to polygonal outlines and diameter of 21.8 (17–26)μm; rays uniseriate and sporadically partially biseriate, 1–12 (18) cells high and composed exclusively of radial parenchyma cells, with smooth walls; cross-field pitting of araucarioid-type, with four (2–6) pits per cross-field; resin canals, radial tracheids, axial parenchyma and bordered pits on the tangential walls of the tracheids absent.

Description. Fragment of secondary xylem of 9cm in diameter and 14cm in length. Growth rings distinct, though they are often difficult to distinguish (Fig. 6a). Late wood is composed of three rows of tracheids at most (Fig. 6b). Tracheids in cross section have deformed contours; however, they appear to have been predominantly rounded (Fig. 6c). Early wood tracheid wall thickness is 9.4 (5–18)μm, while that of late wood is 10.6 (7–16)μm. Radial and tangential diameter of early wood tracheids is 46.3 (31–65) and 65.2 (43–90)μm, respectively. Tracheid pitting in the radial walls is uniseriate and rarely biseriate, with typical araucarian arrangement (Fig. 6f, g, h). The bordered pits have mostly rounded outlines (Fig. 6g), with a diameter of 21.8 (17–26)μm and circular-to-oval openings with a diameter of 5.3 (4–7)μm (Fig. 6i). On average, this wood has 412 tracheids/mm2. Rays are uniseriate and rarely partially biseriate (Fig. 7e, f), consisting exclusively of parenchyma cells (Fig. 6e); these radial cells have smooth horizontal and end walls (Fig. 7a, b), a height of 25.8 (20–31)μm and oval outlines in tangential section (Fig. 7f). Ray height varies from one to 12 (18) cells and their frequency is of 4rays/mm. Cross-field pitting is of araucarioid-type, with four (2–6) pits per cross-field whose diameter is of 9 (7–12)μm (Fig. 7c, d).

Family Cupressaceae

Genus Taxodioxylon Hartig emend. Gothan

Type species Taxodioxylon goeppertii Hartig

Taxodioxylon cabullensis sp. nov. Ríos-Santos &

Cevallos-Ferriz

Figure 8 Taxodioxylon cabullensis sp. nov. TR: (a) distinct growth rings with gradual transition between early and late wood, and abundant axial parenchyma with dark content; (b) narrow growth rings and diffuse distribution of axial parenchyma; (c) tracheids with square outline and axial parenchyma with spherical and dark contents. RL: (d) general view of radial section; (e) rays constituted only by parenchyma cells, arrow points to square cell in ray margin; (f) tracheids with uniseriate and spaced bordered pits; (g) biseriate circular pits with opposite arrangement; (h) arrow points to a notched border; (i) bordered pits with oval openings. Scale bars=3.5mm (a); 320μm (b); 115μm (c); 450μm (d); 170μm (e); 80μm (f); 35μm (g); 30μm (h); 25μm (i). Abbreviations: TR = tranverse section; RL = radial longitudinal section.

Figure 9 Taxodioxylon cabullensis sp. nov. RL: (a) ray parenchyma cells with spherical and dark contents; (b) ray parenchyma cells with smooth end walls (arrows); (c) radial parenchyma cells with smooth horizontal walls (arrows); (d) general view of cross-fields with cupressoid pits; (e) close-up of three cupressoid pits. TA: (f) general view of a tangential section; (g) uniseriate, partially biseriate (white arrows) and biseriate (black arrows) rays; (h) ray parenchyma cells with triangular outline in the margins and quadrangular outline in the central zone, axial parenchyma cells with dark contents (arrows); (i) arrow points to the smooth transverse wall of the axial parenchyma. Scale bars=45μm (a, b); 30μm (c); 50μm (d); 15μm (e); 560μm (f); 360μm (g); 85μm (h); 25μm (i). Abbreviations: RL = radial longitudinal section; TA = tangential longitudinal section.

Locality. Fronteras, Sonora.

Stratigraphic horizon. Lutita Packard Formation.

Age. Upper Cretaceous.

Number of examined specimens. One – IGM-SON1.

Thin sections. Twenty-four in total (IGM-LPB-SON1: 101–124).

Holotype. IGM-LPB-SON1: 101–124.

Etymology. The specific epithet refers to the Cabullona Basin.

Diagnosis. Growth rings distinct; quadrangular tracheids in cross section, with radial diameter of 38.3 (25–62)μm; tracheid pitting in radial walls predominantly uniseriate, rarely biseriate, with spaced arrangement vertically, and opposite when are biseriate (abietinean radial pitting); bordered pits with rounded outlines, with diameter of 12.8 (10–16)μm and oval openings; occasionally bordered pits with notched borders; abundant and diffuse axial parenchyma, its cells with dark contents and smooth transverse end walls; uniseriate to biseriate rays, 1–18 (25) cells high, composed exclusively of parenchyma cells with dark contents and smooth walls; cross-field with cupressoid pits or rarely taxodioid ones, with 2–4 (1–9) pits per cross-field; resin canals, radial tracheids and bordered pits on tracheid tangential walls absent.

Description. Fragment of secondary xylem, 10cm in diameter and 5cm in length. Growth rings distinct (Fig. 8a), which vary from 0.17 to 4.82mm in width. The transition from early to late wood is gradual in most rings. Tracheids have square outlines in cross section (Fig. 8c). The radial diameter of early and late wood tracheids is 38.3 (25–62)μm and 27.1 (17–43)μm, respectively, while their wall thickness is 3.9 (2–7)μm and 4.6 (2–7.5)μm, respectively. Circular uniseriate bordered pits (Fig. 8f), and very scarcely biseriate ones with opposite arrangement (Fig. 8g), with a diameter of 12.8 (10–16)μm, are present on the radial walls of the tracheids. They rarely have notched borders (Fig. 8h), and their opening is exclusively oval (Fig. 8i), with a diameter of 4.4 (3–7)μm. This wood, on average, has 910 tracheids/mm2. Axial parenchyma is abundant and diffuse (Fig. 8a, b), has smooth transverse end walls (Fig. 9i) and dark contents (Figs 8c, 9h). Rays are uniseriate, partially biseriate and biseriate (Fig. 9f, g), composed exclusively of ray parenchyma cells (Fig. 8d). Most of these cells have procumbent form, but some cells at the margins are slightly squared (Fig. 8e); they measure 28.7 (20–41)μm and 44.8 (35–55)μm high, respectively; both types of cells have smooth end and horizontals walls (Fig. 9b, c); occasionally, some have dark contents (Fig. 9a). In the tangential section, marginal ray parenchyma cells have triangular outlines, while the central or body cells tend to have a quadrangular outline (Fig. 9h). Rays are 1–18 (25) cells high with a frequency is of 7rays/mm. Cupressoid and rarely taxodioid cross-field pitting (Fig. 9d, e), with 1–9 pits per cross-field; normally 2–4 pits in body cells and up to nine pits in marginal cells; their diameter is 7.5 (5–10)μm and they are organised up to four rows and four columns; they are never contiguous.

3. Comparisons with fossil taxa

According to Bamford & Philippe (Reference Bamford and Philippe2001), Philippe & Bamford (Reference Philippe and Bamford2008) and Rößler et al. (Reference Rößler, Philippe, van Konijnenburg-van Cittert, McLoughlin, Sakala, Zijlstra, Bamford, Booi, Brea, Crisafulli, Decombeix, Dolezych, Dutra, Esteban, Falaschi, Feng, Gnaedinger, Sommer, Harland, Herbst, Iamandei, Iamandei, Jiang, Kunzmann, Kurzawe, Merlotti, Naugolnykh, Nishida, Noll, Oh, Orlova, de Palacios, Poole, Pujana, Rajanikanth, Ryberg, Terada, Thévenard, Torres, Vera, Zhang and Zheng2014), fossil woods with an araucarioid-like anatomy should be included in Agathoxylon Hartig. Therefore, the new Mexican woods are compared with species included in Agathoxylon; however, because in the past many Mesozoic woods with this Agathoxylon anatomical structure were included in Araucarioxylon Kraus, this last taxon was also reviewed, recognising that many of its species must now be reassigned.

Agathoxylon gilii, from Chiapas, has an anatomical structure similar to that described for Agathoxylon protoaraucana (Brea) Gnaedinger & Herbst from the Lower Jurassic of Argentina, Agathoxylon liguaense Torres & Philippe from the Lower Jurassic of Chile, Agathoxylon sp. from the Lower Cretaceous of Argentina, Araucarioxylon kellerense Lucas & Lacey from the Upper Cretaceous of Chile and Antarctica, and Araucarioxylon pichasquense Torres & Rallo from the Upper Cretaceous of Chile (Table 1). It differs from Agathoxylon protoaraucana because it commonly has uniseriate and biseriate bordered pits on tracheid radial walls, which have larger diameter and only circular openings, and rays relatively higher (Gnaedinger & Herbst Reference Gnaedinger and Herbst2009). Agathoxylon gilii can be distinguished from Agathoxylon liguaense based on its lower rays measured in number of cells, higher pit number per cross-fields as well as an absence of bordered pits on tracheid tangential walls (Torres & Philippe Reference Torres and Philippe2002). Differences with Agathoxylon sp. include higher rays and larger number of pits per cross-field (Vera & Césari Reference Vera and Césari2012). Araucarioxylon kellerense is distinct from Agathoxylon gilii in the number of pits per cross-field, the presence of triseriate bordered pits, presence of vertically spaced bordered pits on tracheid radial walls and having bordered pits on the tangential tracheid walls (Nishida et al. Reference Nishida, Ohsawa, Rancusi and Nishida1990, Reference Nishida, Ohsawa, Nishida and Rancusi1992). Finally, this first Chiapas wood can be distinguished from Araucarioxylon pichasquense because the latter has relatively higher rays and up to ten pits per cross-field (Torres & Rallo Reference Torres and Rallo1981).

Table 1 Comparative wood anatomy of the three Mexican fossil Agathoxylon woods and wood of related fossil species. Abbreviations: (al) = alternate; (ar) = araucarioid; (c) = circular; (ct) = contiguous; (cu) = cupressoid; (ds) = distinct; (eh) = elongated horizontally; (hx) = hexagonal; (ids) = indistinct; (op) = opposite; (pl) = poligonal; (qd) = quadrangular; (sp) = distant. Symbols: (+) = present character; (++) = predominant character; (+–) = occasional character; (+––) = rare character; (-) = absent character; (?) = unknown character.

Secondary xylem organised in a similar way to that described for Agathoxylon jericoense can be found in Araucarioxylon doeringii Conwentz of the Upper Cretaceous and Palaeocene–Miocene of Chile, Patagonia and Antarctica, Araucarioxylon biseriatum Nishida, Nishida & Suzuki of the Cretaceous of Japan and Araucarioxylon ohzuanum Nishida, Ohsawa, Nishida & Rancusi from the Cretaceous of Chile (Table 1). Nevertheless, differences between these fossil woods are also important. This second Chiapas fossil wood can be distinguished from Araucarioxylon doeringii since it has a greater number of pits per cross-field and an absence of bordered pits on the tracheid tangential walls (Nishida et al. Reference Nishida, Ohsawa, Rancusi and Nishida1990). Also, it is distinguished from Araucarioxylon biseriatum based on the relatively lower rays in terms of cell number, a greater number of pits per cross-field, the absence of biseriate rays and horizontally elongated bordered pits (Nishida et al. Reference Nishida, Nishida and Suzuki1993). Finally, it is distinguished from Araucarioxylon ohzuanum because it has uniseriate to tetraseriate tracheid pitting in the radial walls, higher rays measured in cell number, a larger number of pits per cross-field and because it lacks bordered pits on tracheid tangential walls (Nishida et al. Reference Nishida, Ohsawa, Nishida and Rancusi1992).

The third fossil wood from Coahuila, Agathoxylon parrensis, is similar to A. antarcticus (Pool & Cantrill) Pujana, Santillana & Marenssi of the Antarctic Palaeocene, Araucarioxylon seymourense Torres, Marenssi & Santillana of the Eocene-Oligocene of Antarctica, Agathoxylon sp. Feng, Oskolski, Liu, Liao & Jin of the Oligocene–Miocene of China and Agathoxylon sp. Pujana, Panti, Cuitiño, García Massini & Mirabelli of the Miocene of Patagonia (Table 1). All of them represent Cenozoic plants and have characters in common. However, important differences distinguish this Coahuila wood from A. antarcticus, as it has bordered pits with a larger diameter on tracheid radial walls, with 2–6 pits per cross-field (Pujana et al. Reference Pujana, Marenssi and Santillana2015a). It is distinct from A. seymourense based on the lower number of tracheids per square millimetre, the larger diameter of tracheids, the presence of predominantly uniseriate bordered pits on radial walls with larger diameters and relatively lower rays (Torres et al. Reference Torres, Marenssi and Santillana1994). Compared with Agathoxylon sp., this wood from Mexico is singled out for having bordered pits on tracheid radial walls arranged predominantly in a single series, a smaller number of pits per cross-field, lacks tracheids with resin-like plugs and opposite bordered pits on tracheid radial walls (Feng et al. Reference Feng, Oskolski, Liu, Liao and Jin2015). It differs from Agathoxylon sp. because it has bordered pits with greater diameter ordered predominantly in a single series, and higher rays (Pujana et al. Reference Pujana, Panti, Cuitiño, García and Mirabelli2015b). It is worth mentioning that A. parrensis has an anatomical structure similar to the type I wood of Texas, USA, described by Wheeler & Lehman (Reference Wheeler and Lehman2005). They share tracheids of almost the same diameter, rays with almost the same height and a quite similar appearance. However, the Texas wood does not have a complete description (the seriation of its bordered pits and the type and number of pits per cross-field are not known); thus, further comparison has to wait. However, they may be related since they come from two relatively close localities and Palaeocene strata.

The recognition of three new species of Agathoxylon from Mexico is well supported by the similarities and differences found among fossil and extant woods (see the following section) with similar anatomical structure, and their presence suggests the occurrence of diverse and distinct communities during the Mesozoic and Palaeocene in this geographic region.

Blokhina et al. (Reference Blokhina, Afonin and Kodrul2010) mentions that Kräusel in Reference Kräusel1949, after analysing fossil woods with taxodioid-like structure, recommended using only Sequoioxylon for fossil woods which are undoubtedly related to Sequoieae (possibly a group that included members of the subfamily Sequoioideae), and, conversely, to use Taxodioxylon Hartig emend. Gothan for the rest of the woods with similar anatomy, both Cretaceous and Cenozoic. Based on a more critical observation of wood anatomical characters, Philippe & Bamford (Reference Philippe and Bamford2008) proposed that fossil woods that present a taxodioid structure are Sequoioxylon Torrey and Taxodioxylon Hartig, two genera that include woods with a very similar anatomy; although the first is characterised by traumatic canals (Torrey Reference Torrey1923).

The anatomical features that distinguish Taxodioxylon (Hartig) Gothan are as follows: distinct growth rings, bordered pits on tracheid radial walls arranged in 1–4 series, rounded and with opposite arrangement, abundant and diffuse axial parenchyma; radial parenchyma with smooth horizontal and axial walls, cross-fields with cupressoid or taxodioid pits and absence of normal resin canals (Yang & Zheng Reference Yang and Zheng2003; Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Li, Zhang, Li, Wang, Yang, Yi, Yang and Fu2008). Taxodioxylon cabullensis has all these characters and, in addition, it lacks radial tracheids – an attribute generally found in Sequoioxylon specimens. The species of Taxodioxylon that show greater similarity with the wood of Sonora are T. gypsaceum (Göppert) Kräusel, T. taxodii Gothan, T. drumhellerense Ramanujam & Stewart from the Upper Cretaceous of Canada, T. albertense (Penhallow) Shimakura from the Cretaceous of Korea and Taxodioxylon sp. from the Upper Cretaceous of Coahuila, Mexico (Table 2).

Table 2 Comparative wood anatomy of Taxodioxylon cabullensis and wood of related Upper Cretaceous fossil and extant species (Cupressaceae). Abbreviations: (c) = circular; (ct) = contiguous; (cu) = cupressoid; (df) = diffuse; (ds) = distinct; (gl) = glyptostroboid?; (ma) = marginal; (nb) = notched borders; (nd) = nodular; (op) = opposite; (pl) = polygonal; (pt) = pitted; (qd) = quadrangular; (sm) = smooth; (sp) = spaced; (tr) = traumatic; (tx) = taxodioid; (tz) = tangentially zonate. Symbols: (+) = present character; (++) = predominant character; (+–) = occasional character; (+––) = rare character; (–) = absent character; (?) = unknown character.

Taxodioxylon cabullensis differs from T. gypsaceum in that it has predominantly uniseriate bordered pits on tracheid radial walls, smaller diameter bordered pits, lower rays measured in cell number and mostly cupressoid pits in the cross-fields. They are also distinct in that the new wood neither has bordered pits on tracheid tangential walls, nor Sanio bars (Ramanujam & Stewart Reference Ramanujam and Stewart1969). It differs from T. taxodii as the tracheid pitting in the radial walls is predominantly uniseriate, has smaller diameter bordered pits, lower rays, radial parenchyma with completely smooth horizontal walls and mostly cupressoid pits in the cross-fields (Ramanujam & Stewart Reference Ramanujam and Stewart1969). Furthermore, in the new wood it is not possible to observe axial parenchyma with nodular transverse end walls and bordered pits on tracheid tangential walls (Ramanujam & Stewart Reference Ramanujam and Stewart1969). It is distinguished from T. drumhellerense because it lacks bordered pits on the tangential walls of the tracheids, tangentially zonate axial parenchyma, axial parenchyma cells with nodular transverse end walls and taxodioid and glyptostroboid pits in the cross-fields (Ramanujam & Stewart Reference Ramanujam and Stewart1969). The new wood is distinguished from T. albertense based on the presence of only vertically spaced bordered pits on the radial walls with smaller diameter, much lower rays and a greater number of cupressoid pits in the cross-fields, and the absence of bordered pits on tracheid tangential walls (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Jeong, Suzuki, Huh and Paik2002). Finally, it differs from Taxodioxylon sp. of the Upper Cretaceous of Coahuila because it has tracheids with square section, abundant axial parenchyma, lower rays and a greater number of cupressoid pits in the cross-fields (Cevallos-Ferriz Reference Cevallos-Ferriz1992).

Although there are several characters in common between these taxa and Taxodioxylon cabullensis, there are attributes that do not allow assignation of the new fossil wood to any of them. The characters that distinguish the Sonora wood are predominantly uniseriate tracheid pitting in the radial walls, 2–9 cupressoid pits per cross-field (arranged in up to four rows) and the lack of Sanio bars and bordered pits on tracheid tangential walls. Based on the above discussion, comparisons among extant woods with a similar anatomical structure (see the following section) and the geographical location of the fossiliferous outcrop where T. cabullensis was collected, this specimen is recognised as a new taxon.

4. Comparisons with extant taxa

The anatomical characters that share the Mexican Agathoxylon woods are as follows: growth rings distinct (with a discrete late wood development), araucaroid tracheid pitting in the radial walls (contiguous and alternate arrangement), mainly uniseriate rays, radial parenchyma with smooth walls, araucarioid cross-field pitting and the absence of axial parenchyma, resin canals and bordered pits on the tangential walls of the tracheids. Among extant gymnosperms, most of the aforementioned attributes are exclusively found in Araucariaceae (Barefoot & Hankins Reference Barefoot and Hankins1982; García et al. Reference García Esteban, de Palacios de Palacios, Guindeo Casasús, García Esteban, Lázaro Durán, Gonzáles Fernández, Rodríguez Labrador, Fernández García, Bodadilla Maldonado and Camacho Ayala2002; IAWA 2004).

Currently, Araucariaceae is composed of up of 37 species classified in three genera: Agathis Salisb. with 17 species, Araucaria Juss. with 19 species and Wollemia Jones, Hill & Allen with only one representative. All are restricted to the Southern hemisphere, except for some species of Agathis, which are present in the equatorial part of Southeast Asia (Farjon Reference Farjon2010). Although not all species have detailed wood descriptions, ten species of Agathis (Agathis australis (D. Don) Lindl., Agathis borneensis Warb., Agathis dammara (Lamb.) Rich. & A. Rich., Agathis labillardierei Warb., Agathis lanceolata (Lindl. ex Sébert & Pancher) Warb., Agathis macrophylla (Lindl.) Mast., Agathis microstachya J. F. Bailey & C. T. White, Agathis moorei (Lindl.) Mast., Agathis ovata (C. Moore ex Vieill.) Warb. and Agathis robusta (C. Moore ex F. Muell.)), 12 species of Araucaria (Araucaria angustifolia (Bertol.) Kuntze, Araucaria araucana (Molina) K. Koch, Araucaria bidwillii Hook., Araucaria columnaris (J. R. Forst.) Hook., Araucaria cunninghamii Aiton ex A. Cunn., Araucaria heterophylla (Salisb.) Franco, Araucaria humboldtensis J. T. Buchholz, Araucaria hunsteinii K. Schum., Araucaria montana Brongn. & Gris, Araucaria muelleri (Carrière) Brongn. & Gris, Araucaria rulei F. Muell. and Araucaria subulata Vieill) and Wollemia nobilis W. G. Jones, Hill & Allen represent a good comparative sample to sustain the proposed identification.

Agathoxylon gilii has tracheids with uniseriate and biseriate pits on the radial walls of the tracheids, rays with 1–15 cells high and, on average, five pits in the cross-fields. The co-occurrence in a single wood type suggests greater resemblance to the wood of Araucaria angustifolia, Araucaria araucana, Araucaria bidwillii, Araucaria heterophylla and Araucaria muelleri (Greguss Reference Greguss1955; García et al. Reference García Esteban, de Palacios de Palacios, Guindeo Casasús, García Esteban, Lázaro Durán, Gonzáles Fernández, Rodríguez Labrador, Fernández García, Bodadilla Maldonado and Camacho Ayala2002). Agathoxylon gilii is distinguished from the wood of the extant species in that it has biseriate bordered pits on the radial walls of the tracheids with occasional opposite arrangement, relatively higher rays (1–15 (23) cells), and it lacks bordered pits on the tangential walls of the tracheids, trabeculae and resinous contents in tracheids and radial parenchyma (Table 3).

Table 3 Comparative wood anatomy of the three Mexican fossil Agathoxylon woods and wood of related extant species (Araucariaceae). Abbreviations: (al) = alternate; (ar) = araucarioid; (c) = circular; (df) = diffuse; (ds) = distinct; (ids) = indistinct; (pl) = polygonal; (op) = opposite; (sc) = scarce. Symbols: (+) = present character; (++) = predominant character; (+––) = rare character; (–) = absent character; (?) = unknown character.

Agathoxylon jericoense is characterised by having tracheids with resin plugs, uniseriate to tetraseriate tracheid pitting in the radial walls, bordered pits with polygonal to rounded outlines, high rays, radial parenchyma with resinous contents and seven (3–12) pits per cross-field. This set of characters can be found in the wood of Agathis lanceolata, Agathis microstachya, Agathis robusta, Araucaria cunninghamii and Araucaria montana (Greguss Reference Greguss1955; García et al. Reference García Esteban, de Palacios de Palacios, Guindeo Casasús, García Esteban, Lázaro Durán, Gonzáles Fernández, Rodríguez Labrador, Fernández García, Bodadilla Maldonado and Camacho Ayala2002). Agathoxylon jericoense differs from the wood of the extant plants in having bordered pits on the radial walls with larger diameter, seven (3–12) pits per cross-field and absence of bordered pits on the radial walls of the tracheids (Table 3).

A. parrensis has mainly uniseriate tracheid pitting in the radial walls and cross-fields with four (2–6) pits. Comparison with the wood of extant plants suggest closest similarity with Agathis moorei, Araucaria araucana, Araucaria humboldtensis and Araucaria muelleri (Greguss Reference Greguss1955). Despite these similarities, A. parrensis is distinct from them because it has higher rays measured in cell numbers, bordered pits on the radial walls with larger diameter and because there are no bordered pits on the tracheid tangential walls (Table 3).

Characters of Taxodioxylon cabullensis, the cupressoid wood – such as distinct growth rings, tracheids with square cross-section, abietinean radial pitting, notched borders, cupressoid and sometimes taxodioid pits in the cross-fields and abundant axial parenchyma with dark contents – suggest that this wood is related to taxa that constituted the family Taxodiaceae. However, these taxa are currently classified within Cupressaceae, among five subfamilies: Athrotaxoideae L. C. Li, Cunninghamioideae (Zucc. ex Endl.) Quinn, Sequoioideae Saxton, Taiwanioideae L. C. Li and Taxodioideae Endl. ex K. Koch (Farjon Reference Farjon2010). The new Sonoran specimen was compared to the wood of all species of these five taxa, except Athrotaxis cupressoides D. Don. Among them, A. laxifolia, Cryptomeria japonica (Thunb. ex L.f.) D. Don, Cunninghamia lanceolata Hataya, Glyptostrobus pensilis (Staunton ex D. Don) K. Koch, Sequoia sempervirens (Don D.) Endl and T. mucronatum Ten. produce the most similar wood to T. cabullensis (Table 2). The latter is distinguished by having bordered pits arranged predominantly in a single series on the radial walls of the tracheids, and axial parenchyma with completely smooth transverse end walls. In addition, it lacks bordered pits on the tangential walls of the tracheids, Sanio bars and trabecula. Though these extant woods are most similar to the new fossil wood, their anatomical structure is so similar that it is very difficult to distinguish between them based only on secondary xylem characters.

5. Discussion

The anatomical similarity of the new conifer woods from Mexico, and their lack of anatomical diagnostic characters when compared with extant taxa, support the proposal of the presence of extinct plants. However, the type and number of cross-field pits, seriation and arrangement of pits on tracheid radial walls, dark contents in tracheids and/or the characteristics of axial parenchyma help to distinguish four species. The use of diagnostic characters was privileged for anatomical comparisons and identifications, but other characters, such as density of tracheid/mm2, diameter of bordered pits, etc., were used to further sustain taxonomical decisions. Three of these fossil woods are included in Araucariaceae based on their similar anatomical structure, which is close to that of extant species included in the family. Their occurrence coincides with the period (Jurassic) in which Araucariaceae had its greatest diversity and broader geographic distribution, including the northern hemisphere (Stockey Reference Stockey1982). Though the anatomical comparison suggests a relationship with Araucariaceae, it is important to highlight that this type of wood cannot necessarily be linked with plants of this family, and further information on other plant organs is needed to understand the systematic significance of these new records. Meanwhile, they certainly add to the biodiversity that is being documented and form part of the forests of low-latitude North America during the Mesozoic and Palaeocene.

Although the woods from the Todos Santos Formation come from the same stratigraphic horizon, they are described as different taxa (Agathoxylon gilii and A. jericoense). Differences in the seriation of the bordered pit in tracheid radial walls, the number of pits per cross-field and the presence of resin plugs in the tracheids distinguish them. The wood of the Las Encinas Formation (A. parrensis), although collected in Palaeocene strata, represents an important record for the northern hemisphere since it adds this geographical region to the distribution map of the taxon. Furthermore, this new report could not only represent the enlargement of the distribution area of Agathoxylon during the Cretaceous–Palaeocene (Wheeler & Lehman Reference Wheeler and Lehman2005), but may represent its last record in the area, since it began to decline, both in number of taxa and in geographic distribution, since the K/Pg boundary (Kunzmann Reference Kunzmann2007).

Branches with small leaves collected in other Jurassic and Cretaceous formations of South-Central and Northern Mexico have been suggested to represent members of Brachyphyllum, a taxon related to Araucariaceae (Harris Reference Harris1979) and/or Cheirolepidiaceae (Van der Ham et al. Reference Van der Ham, Van Konijnenburg-Van Cittert, Dortangs, Herngreen and van der Burgh2003). For example, Brachyphyllum sp. has been described from the Conglomerado Cualac Formation (Lower Jurassic) in the state of Guerrero (Silva-Pineda & Gonzales-Gallardo Reference Silva-Pineda and Gonzales-Gallardo1988), the Huayacocotla Formation (Lower Jurassic) in the state of Puebla (Díaz Lozano Reference Díaz Lozano1916), the Otlaltepec and Tecomazúchil Formations (Middle Jurassic) in Puebla/Oaxaca (Velasco de León et al. Reference Velasco de León, Ortiz-Martínez and Lozano-Carmona2013) and the Cerro de la Vieja Formation (Lower Cretaceous) in the state of Colima (Felix & Nathorst Reference Felix, Nathorst, Felix, Lenk, Nathorst, Boehm and Steinmann1899 in Villanueva-Amadoz et al. Reference Villanueva-Amadoz, Calvillo-Canadell and Cevallos-Ferriz2014). Fossils with affinity to these taxa have also been referred from the Tlayúa Formation (Applegate et al. Reference Applegate, Espinosa-Arrubarrena, Alvarado-Ortega, Benammi, Vega, Neyborg, Perrilliat, Montellano-Ballesteros, Cevallos-Ferriz and Quiroz-Barroso2006), and B. macrocarpum is known from the Olmos Formation (Upper Cretaceous) in the state of Coahuila (Weber Reference Weber1980). Pagiophyllum sp. is another taxon related to the aforementioned families. In Mexico, this taxon has been reported from a stratum without formal stratigraphic assignation in Huajuapan de Léon, Oaxaca (Weber Reference Weber1980), and in the La Casita Formation (Upper Jurassic), Coahuila (Weber Reference Weber1980). This information supports the idea of the presence of plants producing araucarioid wood in Mexico during that time (e.g., Ortega Chávez Reference Ortega Chávez2013; Grajeda Cruz Reference Grajeda Cruz2015), but highlights the need to reconstruct them to better understand the systematic significance of these findings, as the new plants may turn out to represent other taxa, like Pteridosperms, Caytoniales, Cordaitales and extinct conifers (e.g., Voltziales, Cheirolepidiaceae) (Zamuner Reference Zamuner1996; Brea Reference Brea1997; Philippe Reference Philippe2011; Rößler et al. Reference Rößler, Philippe, van Konijnenburg-van Cittert, McLoughlin, Sakala, Zijlstra, Bamford, Booi, Brea, Crisafulli, Decombeix, Dolezych, Dutra, Esteban, Falaschi, Feng, Gnaedinger, Sommer, Harland, Herbst, Iamandei, Iamandei, Jiang, Kunzmann, Kurzawe, Merlotti, Naugolnykh, Nishida, Noll, Oh, Orlova, de Palacios, Poole, Pujana, Rajanikanth, Ryberg, Terada, Thévenard, Torres, Vera, Zhang and Zheng2014). It can be hypothesised that several plants with similar wood and/or leaf types will be recognised.

Members of the Cupressaceae grow naturally in Mexico today (Gernandt & Pérez-de la Rosa Reference Gernandt and Pérez-de la Rosa2014), but it seems that this family has had a long history in this geographic region, as suggested by the wood of the Packard Shale Formation. However, it seems that its importance in the formation of plant communities has changed through time.

Taxa resembling members of Cunninghamioideae, Sequoioideae and Taxodioideae have been described from Upper Cretaceous to Palaeocene strata in North America. Fossils assigned to Athrotaxoideae from the lower Cretaceous have also been reported from this geographic region (Stockey et al. Reference Stockey, Kvacek, Hill, Rothwell, Kvacek and Farjon2005). Unfortunately, the fossil record of these groups in Mexico has not been thoroughly studied; however, some fossil reports include Sequoia sp. cf S. ambigua and Sequoia sp. (Felix & Nathorst Reference Felix, Nathorst, Felix, Lenk, Nathorst, Boehm and Steinmann1899 in Villanueva-Amadoz et al. Reference Villanueva-Amadoz, Calvillo-Canadell and Cevallos-Ferriz2014), a leaf–branch morphotype compared to Cryptomeria japonica and another to Glyptostrobus pensilis of the Sierra Madre Formation (Lower Cretaceous) in Chiapas (González-Ramírez et al. Reference González-Ramírez, Calvillo-Canadell and Cevallos-Ferriz2013); S. cuneata and Taxodioxylon sp. of the Upper Cretaceous Olmos Formation in Coahuila (Weber Reference Weber1980; Cevallos-Ferriz Reference Cevallos-Ferriz1992) and Podocarpoxylon sp. of the Javelina Formation (Upper Cretaceous) in Chihuahua, which, in the opinion of the authors, should be formally reassigned to Taxodioxylon Hartig emend. Gothan (Andrade Ramos Reference Andrade Ramos2003). All these records support the presence of representatives of taxodiaceous Cupressaceae (sensu Schulz & Stützel Reference Schulz and Stützel2007) in the Cretaceous of Mexico. In fact, it is likely that the lowland swamp forests that have been inferred in North America, particularly during the Upper Cretaceous, spread further south, reaching northern Mexico. The presence of this wood coincides with the palaeoenvironmental and palaeontological records of the Cabullona Group, which has been suggested to contain members of a dense palaeovegetation that grew along lakes, marshes and rivers (Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Kues, Gonzáles-León, Jacques-Ayala, Gonzáles-León and Roldán-Quintana1995). Palaeodiversity and the apparent dominance of Cupressaceae in plant communities during the Mesozoic in low-latitude North America was higher compared with its participation in extant communities. In the Pinaceae, a change from low to high diversity in the Mesozoic to the Cenozoic communities seems to be parallel to the trend for the Cupressaceae, and both highlight the need to study further the composition of palaeo-conifer forest in Mexico in order to generate a suitable hypothesis on the origin of extant plant communities. This proposal strengthens the need to collect new material for the reconstruction of whole plants; this would add information to generate a closer biological (not palaeobotanical species) concept of fossil plants that will support not only morphological, but also phylogenetic comparisons and proposals.

6. Acknowledgements

The authors thank PhD Francisco Vega Vera and MSc René Hernández Rivera, of the Geology Institute, UNAM, for collecting part of the studied material; MSc Manuel Javier Avendaño Gil, member of Museo de Paleontología Eliseo Palacios Aguilera of Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, who took us to the wood locality in Chiapas; and Mr Enoch Ortiz Montejo, technician of the Palaeobotany laboratory of the Geology Institute, UNAM, for his help in the production of thin-sections. We acknowledge the financial support to SRSCF by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT 221129) and Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico, programa PAPIIT (IN 210416).