Residues of liquid hydrocarbons (now solid bitumen; formerly inferred to be ‘coal’) occur in the Moinian metamorphic basement at Castle Leod, Ross-shire. The occurrence can be considered as a fossil example of a fractured basement reservoir, as the hydrocarbons occur in a fracture network over a plan area of about 1 km2, in sufficient abundance to be readily observable and to have been formerly mined in solid form.

The study site at Castle Leod is close to the boundary between a Proterozoic metamorphic terrain, the Moinian (variably described as gneiss and schist; we adopt the former term here), and a Phanerozoic sedimentary basin, the Devonian Orcadian Basin (Fig. 1). The Orcadian Basin contains several kilometres thickness of continental deposits, including coarse-grained siliciclastic fluviatile deposits and fine-grained lacustrine deposits (Trewin & Thirlwall Reference Trewin, Thirlwall and Trewin2002). The boundary between the gneiss and the sedimentary rocks is both faulted and unconformable, reflecting sedimentation in a basin that was modified by active strike-slip faulting (Rogers et al. Reference Rogers, Marshall and Astin1989; Underhill & Brodie Reference Underhill and Brodie1993). In the immediate vicinity (within 2 km) of the boundary, the sedimentary succession includes alluvial fan conglomerates, and organic-rich dolomitic shales (playa lake deposits) with pseudomorphs after sulphate evaporites (Parnell Reference Parnell1985a; Clarke & Parnell Reference Clarke and Parnell1999).

Figure 1 Map of Moinian basement and Devonian sedimentary rocks (Old Red Sandstone), Easter Ross, showing sample locations (outline after Mendum & Noble Reference Mendum, Noble, Law, Butler, Holdsworth, Krabbendam and Strachan2010). Abbreviations: CL=Castle Leod; I=Inchvannie; M=Mountrich; R=Rogie Falls; S=Strathpeffer.

An earlier account (Parnell Reference Parnell1996) focused on mineralogical alteration of the gneiss associated with the ingress of hydrocarbons into the Moinian gneiss. In the light of subsequent interest in fractured basement reservoirs (Trice Reference Trice, Cannon and Ellis2014) and subsurface biodegradation of hydrocarbons (Aitken et al. Reference Aitken, Jones and Larter2004; Parnell et al. Reference Parnell, Baba, Bowden and Muirhead2017), the rocks have been restudied with a focus on these new themes.

Samples of bitumen-bearing basement rock were analysed for organic biomarkers, to determine:

(i) Correlation to Devonian sedimentary rocks that are their assumed source;

(ii) if bitumen in the basement experienced a similar or more advanced alteration history to bitumen within the Devonian rocks;

(iii) if biodegradation contributed to the formation of the bitumen.

1. Historical context

Exploitation of ‘coal’ at Castle Leod dates back at least to the early 18th Century. The Third Earl of Cromarty was exiled for supporting the Jacobite cause and his estates, including Castle Leod, were forfeited. Fortuitously, correspondence relating to the resources available on Scottish annexed estates has been preserved (Millar Reference Millar1909). These include a letter from Captain Forbes at Castle Leod, dated 3 February 1759, reporting “As to the coal at Castleleod … the late Lord Cromarty did frequently cause dig several barrels of it, and … his family was supplied with it in fireing for a winter season”. A map, surveyed by Peter May in 1756 and drawn up in 1762, shows a site labelled “tryal made here for coal” (NOSAS 2013). Text on the map states “there has been some tryals made for coals … but these pitts are now filled up” (NOSAS 2013). As the industrial revolution gathered steam in the second half of the 18th Century, the search for coal resources brought the Welsh mining engineer John Williams to the Highlands. He reported to the Board for the Annexed Estates between 1763 and 1774 (Jonsson Reference Jonsson2013). In a major review of British coal and other resources (Williams Reference Williams1789), he provides several interesting perspectives on the deposits at Castle Leod:

“I have seen coal in the cavities of mineral veins at Castle Leod, in … perpendicular mineral fissures in the mountain rocks … running parallel to one another”

“The veins at Castle Leod open into bellies or concavities of different lengths and capacity, and close again”

“There is coal … as far as they could go down for water”

“The veins … were up to three or four feet wide.”

“It was water that carried and poured the fluid substance of the coal into the veins at Castle Leod”

Thus we have implications for veins that were wider than a simple open joint surface, reaching depths at which flooding occurred, and his understanding that this coal was not deposited at the surface but was an epigenetic deposit. The occurrence and interpretation was sufficiently important to be described subsequently in a German text (Williams Reference Williams1798). A review of Williams' work appreciated that an epigenetic origin of some ‘coal’, evidenced at Castle Leod, was an important novel interpretation (Society of Gentlemen 1791).

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, it was reported that “there are several appearances of coal mines, and some strata have been discovered of schistus strongly impregnated with bitumen” (Gazetteer of Scotland 1806). The latter observation of Moinian basement discoloured by black bitumen is a notably accurate description, which was eventually reported on the Geological Survey field sheet mapped at a scale of six inches to the mile. The exceptional nature of the deposit saw it described as “a singular coal” in several educational treatises, including The Hundred Wonders of the World (Polehampton & Good Reference Polehampton and Good1818; Clarke Reference Clarke1820). In the following decades, it became understood that the deposits were not in fact coal, but some kind of ‘pitch’; i.e., an organic mineral that had migrated into the gneiss from an external source (Witham Reference Witham1825). Nonetheless, there was renewed exploration of the deposits in the 1860s. A borehole to 53.5 feet (16.3 m) intersected an impressive 25 inches (64 cm) thick seam of bitumen (Inverness Courier 1866), from which an oil yield of 115 gallons per ton was obtained. Optimistically, it was speculated that “the working of such coal in the North may prove an addition to the revenue of the Highland Railway”. The results were enough to encourage commissioning of a contractor to drive a mine level five feet high, four and a half feet wide, incorporating train rails, “to intersect the mineral about 120 feet deeper than the old working” (Inverness Courier 1867); although this enterprise came to nothing. Morrison (Reference Morrison1883) records use of the bitumen, from E–W veins, as a substitute for coal by a local blacksmith, clearly recognizing that it was a distinct material.

2. Methodology

The study area at Castle Leod has been under dense forest for several decades. Recent clearance of part of the forest was followed by rapid growth of gorse. This vegetation cover places severe constraints on investigation. However, it is still possible to sample from forestry tracks, the roots of large trees uprooted by gales, and trenches thought to be the sites of former trials for ‘coal’. Bitumen was sampled from five settings in the Moinian gneiss (Fig. 2): bitumen-bearing fractures; bitumen on breccia zones; bitumen in porous weathered gneiss; vein bitumen from a trench; and nodular bitumen in gneiss. Bitumen was also sampled from a bedding surface and cross-cutting vein in the Devonian shales at the Heights of Inchvannie (National Grid Reference [NH 498603]) and a vein cutting Devonian conglomerate at Mountrich, [NH 565605]. The Devonian shale whole rock was sampled at Strathpeffer village, [NH 483582]. Jurassic shale samples were also collected for source rock evaluation, at Shandwick, [NH 857740] and Helmsdale, [ND 035153].

Figure 2 Schematic cross-section through faulted and unconformable margin between Moinian basement and Devonian sediments, showing settings for bitumen deposits.

Petrographic studies of bituminous rocks were made using an ISIS ABT-55 scanning electron microscope with Link Analytical 10/55S EDAX facility.

Rock samples were prepared by rinsing twice with distilled water and again with dichloromethane (DCM). The dry rocks were crushed and extracted using a soxhlet apparatus for 48 hours. Solid bitumen and tar samples were ultrasonicated with DCM and methanol (MeOH). All glassware was thoroughly cleaned with a 93:7 mixture of DCM/MeOH. Crushed samples were weighed, recorded and transferred into pre-extracted thimbles. The extracts were then dried down using a rotary evaporator, separated into aliphatic, aromatic and polar fractions via a silica column chromatography using hexane, hexane/DCM in the ratio 3:1 and DCM/MeOH respectively.

Prior to gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis, an internal standard (5β-Cholane, Agilent Technologies) was added to the saturate fraction before injection into the GC-MS machine, and subsequent biomarker identification. This was done using an Agilent 6890N gas chromatograph fitted with a J&W DB-5 phase 50m MSD and a quadruple mass spectrometer operating in SIM mode (dwell time 0.1 s per ion and ionisation energy 70eV). Samples were injected manually using a split/splitless injector operating in splitless mode (purge 40 ml min-1 for 2 min). The temperature programme for the GC oven was 80–295°C, holding at 80°C for 2 min, rising to 10°C min-1 for 8 min and then 3°C min-1, and finally holding the maximum temperature for 10 min-1. Quantitative biomarker data were obtained for isoprenoids, hopanes, steranes and diasteranes by measuring responses of these compounds on m/z 85, 125, 191, 217, 218 and 259 mass chromatograms and comparing them to the response of the internal standard.

Diasteranes are formed by a rearrangement of steranes during diagenesis and thermal maturation. Biodegradation causes the breakdown of steranes at a faster rate than diasteranes, including in the shallow subsurface in aerobic conditions; thus the ratio can be used as a measure of shallow biodegradation (Seifert & Moldowan Reference Seifert and Moldowan1979). The ratio of pristane to the C17 n-alkane can also be used to measure biodegradation, as isoprenoids (pristane) are more resistant to degradation.

3. Results

3.1. Petrography

New field and laboratory observations are pertinent to understanding the nature of the bitumen emplacement.

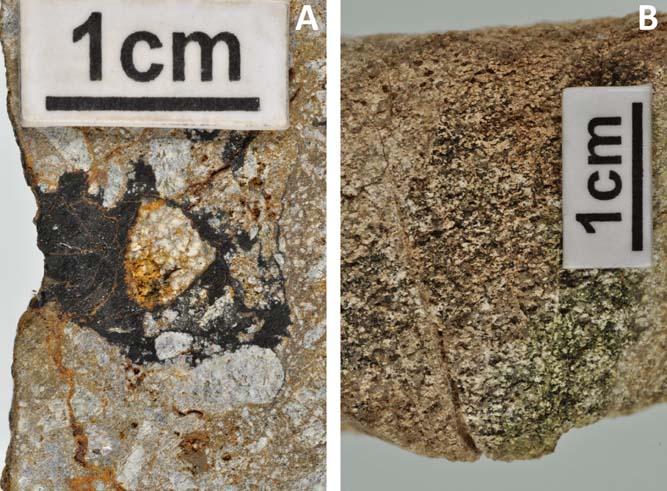

Field observations show that the bitumen infills extensional brittle fractures. In many cases, the fractures are coated with quartz pre-bitumen, whilst in other cases the bitumen coats unmineralised rock. The fracture-coating quartz contains sparse pyrite mineralisation. Bitumen infills porosity in discrete breccia zones (Fig. 3), and more generally infills a pervasive fracture network within 200 m of the boundary fault. Rediscovery of a linear trench with spoil containing bitumen suggests a bitumen-bearing vein of about 1 m width, consistent with historic reports of bitumen veins up to three or four feet wide. Although the Moinian gneiss generally has very low porosity and permeability (MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald, Robins, Ball and Ó Dochartaigh2005), samples of gneiss close to the projected unconformity with the overlying Devonian have porosity infilled with bitumen (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 Bitumen-bearing gneiss samples, Castle Leod: (A) bitumen (black) in brecciated gneiss from Breccia Zone; (B) bitumen (black) in porous gneiss.

Thin section and SEM studies show that bitumen emplacement was not a chemically passive process; authigenic minerals co-precipitated with the bitumen. An earlier study (Parnell Reference Parnell1996) reported authigenic quartz and feldspar in the bitumen, and the accretion of bitumen around detrital zircon grains due to irradiation-induced polymerisation of hydrocarbons. New studies show that authigenic quartz and feldspar overgrow the wallrock of fractures, and bridge the fractures to hold open fracture porosity now occupied by bitumen (Fig. 3). The interaction with radioactive phases is more complex than previously understood. Stringers of bitumen through the gneiss contain inclusions of thorium silicate (Fig. 4). Other samples show extensive clusters of spheroidal bitumen nodules (Fig. 4) containing inclusions of barite and the uranium minerals uraninite and coffinite. Another variety of bitumen nodule contains inclusions of monazite. The nodules are up to 0.5 mm in diameter, locally coalesced, in otherwise solid gneiss. The basement rocks in which these nodules occur have extremely low permeability: measurements from two samples at the same locality gave values of 0.001 and 0.002 mD. These values are three orders of magnitude less than the 1 mD minimum required for production from an oil reservoir (Law et al. Reference Law, Megson and Pye2001).

Figure 4 Backscattered electron photomicrographs of bitumen-bearing gneiss samples, Castle Leod: (A) fracture infilled with bitumen (black). Fracture was propped open by bridging quartz (grey) before bitumen infilling; (B) bitumen nodules (black), replacive in gneiss; (C) detail of bitumen (black) containing inclusions of thorium silicate (bright).

Beds of tightly cemented conglomerate–sandstone occur within the Devonian succession, 8 km to the east of Castle Leod, at Mountrich. Like the Moinian gneiss, the conglomerate–sandstone experienced brittle fracturing, and the fractures are coated with quartz (in conglomerate) and calcite (in sandstone) followed by solid bitumen. The bitumen fracture-fills are up to 9 cm in width (Mackenzie Reference Mackenzie1863). A total of 36 bitumen veins were encountered during construction of a railway cutting through the conglomerate and sandstone northeast of Dingwall (Anderson Reference Anderson1863; Mackenzie Reference Mackenzie1863), representing a marked development of extension.

3.2. Biomarkers

The bitumen in Moinian gneiss and Devonian sediments, and the Devonian organic-rich shales, all yielded biomarkers adequate for quantitative measurement of environmental and degradation parameters (Figs 5, 6, 7). Percentages of C27, C28 and C29 steranes, and the occurrence of β-carotane, were measured as indicators of source environment and, hence, for correlation to the source rock. The nodular bitumen had a lower yield of biomarkers than the other bitumen samples, and only steranes could be measured reliably. Degradation was measured by the ratios of diasteranes to steranes (peak identification shown in Fig. 6), and of pristane to the C17 n-alkane. Data are summarised in Table 1.

Figure 5 Chromatograms for m/z 85 and m/z 125, showing distributions of n-alkanes and prominent β-carotane: (a) Devonian shale, Strathpeffer; (b) Devonian-hosted bitumen, Inchvannie; (c) gneiss-hosted fracture-filling bitumen; (d) black gneiss; (e) trenched bitumen vein in gneiss; (f) bitumen in breccia zone in gneiss.

Figure 6 Chromatograms for bitumen sample from trenched vein in Moinian gneiss, Castle Leod. Chromatograms for m/z 217, m/z 218 and m/z 259 show steranes and diasterane identification.

Figure 7 Chromatograms for m/z 217, showing steranes: (a) Devonian shale, Strathpeffer; (b) Devonian-hosted bitumen, Inchvannie; (c) gneiss-hosted fracture-filling bitumen; (d) black gneiss; (e) trenched bitumen vein in gneiss; (f) bitumen in breccia zone in gneiss; (g) bitumen nodules in gneiss.

Table 1 Biomarker data for samples analysed from gneiss basement, Devonian sedimentary rocks and Jurassic sedimentary rocks

Abbreviations: EOM=extractable organic matter; n=normal alkane; ND=no data; Ph=phytane; Pr=pristane; SB=solid bitumen

Two analyses of the sulphur isotopic composition of pyrite from quartz-lined fractures at Castle Leod both yield δ34S values of −4.1 ‰ relative to the CDT standard.

4. Discussion

4.1. Correlation to source

The immediate proximity to Devonian sedimentary rocks very strongly suggests that the bitumen in the Moinian basement has a Devonian source. Jurassic (Kimmeridgian) organic-rich shales occur 30 km to the east in the Moray Firth region (Le Breton et al. Reference Le Breton, Cobbold and Zanella2013), but if the Jurassic once extended as far west as Strathpeffer, it would have been probably separated from the Moinian by several kilometres vertical thickness of intervening Devonian rocks.

Correlation with the Devonian is strongly supported by distinctive aspects of the biomarker composition. The Devonian shales were deposited in a terrestrial (lacustrine) environment (Clarke & Parnell Reference Clarke and Parnell1999). Characteristics of their non-marine organic matter include the prominent occurrence of β-carotane (Irwin & Meyer Reference Irwin and Meyer1990) and a high proportion of C28 steranes, which are more prominent in lacustrine than in marine environments.

β-carotane is evident in m/z 85 and m/z 125 chromatograms for the bitumens in the gneiss (Fig. 5). The percentage C28 steranes (of combined C27, C28 and C29 steranes) ranges from 36 % to 44 %, which is comparable with a value of 40 % from the Devonian shales and greater than values of 24 % and 25 % for Jurassic shales in the Moray Firth to the east (Table 1; Fig. 8).

Figure 8 Sterane compositions (percentage C27, C28, C29) for Moinian-hosted and Devonian-hosted bitumens, and Devonian and Jurassic shales, derived from m/z 217 fragmentograms. Data show all bitumens share a high C28 content, comparable with data for Devonian shale and distinct from data for Jurassic shales.

4.2. Biodegradation of bitumen

The ratio of diasteranes to steranes increases with biodegradation (Seifert & Moldowan Reference Seifert and Moldowan1979). The ratios of 0.95–1.70 for three of the four occurrences of bitumen from the Moinian gneiss are much greater than the ratio of 0.12 for the Devonian shale and 0.14–0.26 for the Devonian-hosted bitumen (Fig. 9). The other Moinian-hosted bitumen samples has a ratio of 0.20, more comparable with the Devonian samples. Similarly, the ratio of the isoprenoid pristane to the C17 n-alkane increases with biodegradation (Tissot & Welte Reference Tissot and Welte1984). The bitumen in all five of the Moinian samples yields ratios of 1.37–5.25, whilst the Devonian shale ratio is 0.58, and the ratio in the three Devonian hosted bitumen samples are up to 0.63. This suggests much higher levels of biodegradation in the gneiss than in the Devonian. The bitumen in the Devonian low-permeability shales has probably not migrated far from the source rock and had little interaction with water. In contrast, the bitumen in the Moinian basement has migrated further from the source rock, and had more opportunity for interaction with water, as evidenced by precipitation within quartz-bearing veins.

Figure 9 Cross-plot of diasterane/sterane ratios and pristane/nC17 alkane for samples of bitumen and Devonian shale. Moinian-hosted bitumen has higher diasterane/sterane ratios than Devonian-hosted bitumen and the Devonian shale source rock, indicating greater biodegradation.

The two S isotope measurements of pyrite from veins at Castle Leod are both isotopically light (negative δ34S values). These values are consistent with an origin from microbial sulphate reduction (Machel Reference Machel2001), but this small data base should be regarded as a pilot study.

4.3. Origin of fracture porosity

Fracturing of the Moininan gneiss, including bitumen-bearing fractures, is evident especially close to the fault separating it from the Devonian basin. The bounding fault was active at some time after sedimentation, as it cross-cuts the sediment–basement unconformity. The bounding fault is also displaced by faults trending approximately E–W, that may have originated in the Devonian but were reactivated during Permo-Carboniferous inversion and/or later (Underhill & Brodie Reference Underhill and Brodie1993).

The abundance of hydrocarbons represented by the bitumen veins at Mountrich suggests that high fluid overpressure caused by hydrocarbon generation may have triggered the fracturing, as inferred in other instances of bitumen vein formation elsewhere (Parnell et al. Reference Parnell, Geng, Fu and Sheng1994; Parnell & Carey Reference Parnell and Carey1995). Limited pyrolysis data for the Devonian shales (Parnell Reference Parnell1985b; Irwin & Meyer Reference Irwin and Meyer1990) record hydrogen indices exceeding 300 mg/g, confirming that large volumes of hydrocarbons could have been generated from a shale-rich sequence. Sandstones below the conglomerate in the vicinity of Dingwall also contain intergranular bitumen, representing oil trapped below the conglomerate seal before release upon fracturing. Detailed examination of the bitumen veins (Fig. 10) shows penetration of hairline fractures in the wallrock, rotation of displaced rock fragments and stripping of the mineral fracture-linings; all suggesting emplacement under high pressure. The fractures containing bitumen in the railway cutting are oriented E–W, like the bitumen-bearing veins in the Moinian basement (Morrison Reference Morrison1883). These fractures exhibit fault displacements downthrowing to the south, which were probably coeval with the E–W faulting attributed to basin inversion (Underhill & Brodie Reference Underhill and Brodie1993). The maximum bitumen vein width recorded at Castle Leod (4 ft/1.3 m) is comparable with widths in other instances of bitumen vein formation under high fluid pressure (Parnell et al. Reference Parnell, Geng, Fu and Sheng1994; Parnell & Carey Reference Parnell and Carey1995).

Figure 10 Schematic section through two adjacent bitumen veins cutting Devonian sandstone, Mountrich. Veins show penetration of hairline fractures in the sandstone wallrock, rotation of displaced sandstone fragments, and stripping of the calcite fracture-linings; all suggesting emplacement under high fluid pressure.

The timing of hydrocarbon generation in this region is difficult to constrain. Further north in the Orcadian Basin, the preserved basin thickness is great enough to predict confidently hydrocarbon generation in the Upper Devonian to Carboniferous, before Variscan inversion, then further generation offshore during renewed Mesozoic burial (Hillier & Marshall Reference Hillier and Marshall1992). Given the location at the basin margin, away from the basin depocentre, and the generally low thermal maturity in Devonian sediments in Ross-shire (Hillier & Marshall Reference Hillier and Marshall1992; Marshall & Hewett Reference Marshall, Hewett, Evans, Graham, Armour and Bathurst2003), hydrocarbon generation could have occurred later than in the north. However, evidence from other basins with bitumen veins suggests that the bitumen may be generated at a relatively early stage, before the source rocks reach the conventional oil window (Monson & Parnell Reference Monson, Parnell, Fouch, Nuccio and Chidsey1992). This appears to be the case especially where source rocks are carbonate-rich (Tannenbaum & Aizenshtat Reference Tannenbaum and Aizenshtat1985), for example in the Eocene Green River Formation, USA. The shales in the study area are markedly dolomitic, so a similar early generation may explain the occurrence of abundant hydrocarbons in a succession of low thermal maturity.

Biodegradation occurs at temperatures up to about 80°C (Wilhelms et al. Reference Wilhelms, Larter, Head, Farrimond, di-Primio and Zwach2001), lower than the temperatures at which most oil generation occurs. Thus biodegradation is not extensive within the source rock interval, or in underlying reservoir rocks at maximum burial. However, during and following basin inversion, the reservoir rocks may be elevated into the temperature range at which biodegradation can occur. This is consistent with the occurrence of bitumen in structures that may be associated with inversion.

4.4. Mineral precipitation

A coating of fracture walls with quartz prior to bitumen emplacement is evident in the Moinian gneiss basement and the Devonian conglomerate in the overlying sediment. In both rock types, the bridging of the fractures by quartz has held open the porosity to allow the flow of fluids including hydrocarbons. Previously reported fluid inclusion data for the quartz veins in the conglomerate (Parnell Reference Parnell1996) indicate temperatures of about 110–116°C. Assuming that these temperatures reflect heating due to burial, the conglomerate was at about 3 km depth, which could have been reached by the end of Devonian sedimentation.

The pyrite in the Moinian basement is most likely to be derived from sulphate from the Devonian succession. The dolomitic shales contain pseudomorphs after gypsum and anhydrite (Parnell 1995a), including pyritic pseudomorphs, indicating availability of abundant sulphate. Pyrite also occurs in the conglomerate close to the boundary fault with the Moinian basement. Microbial reduction of the Devonian sulphate would have yielded abundant hydrogen sulphide, precipitated as pyrite and still evident in the sulphurous spa waters that made Strathpeffer famous (Manson Reference Manson1879; Fox Reference Fox1889).

The inclusions of thorium silicate in bitumen imply replacement and re-precipitation of thorium minerals. This is a widely observed phenomenon where migrating hydrocarbons encounter irradiation from radioactive minerals and are polymerised to leave a residue of solid bitumen enclosing remains of the minerals (Parnell et al. Reference Parnell, Monson and Tosswill1990). Most occurrences are in sedimentary basins, but where hydrocarbons penetrate granite and other basement rocks, the availability of radioactive minerals such as monazite and zircon provides an opportunity for bitumen–thorium or bitumen–uranium complexes to form. The lack of biomarkers in the Castle Leod bitumen nodules is typical of bitumen that has experienced polymerisation due to irradiation (Landais et al. Reference Landais, Connan, Dereppe, George, Meunier, Monthioux, Pagel, Pironon and Poty1987; Court et al. Reference Court, Sephton, Parnell and Gilmour2006). Examples of radioactive bitumen nodules in several basement rocks (Ball et al. Reference Ball, Basham and Michie1982; Robb et al. Reference Robb, Landais, Meyer and Davis1994; McCready et al. Reference McCready, Stumpfl and Melcher2003; Lecomte et al. Reference Lecomte, Cathelineau, Deloule, Brouand, Peiffert, Loukola-Ruskeeniemi, Pohjolainen and Lahtinen2014) show that hydrocarbon migration through basement occurs widely. However, in most cases elsewhere, the bitumen complex forms individual nodules representing interaction with single grains of monazite and zircon. At Castle Leod, the bitumen forms continuous stringers containing thorium silicate inclusions (Fig. 4), which suggests some transport of the digested mineral. Thorium silicate is an alteration product of the phosphate mineral monazite in altered basement and other environments (e.g., Hecht & Cuney Reference Hecht and Cuney2000; Papoulis et al. Reference Papoulis, Tsolis-Katagas and Katagas2004). The observation of bitumen nodules containing monazite evinces the likelihood of monazite alteration by hydrocarbons. The occurrence of barite in some nodules has been recorded elsewhere (Monson Reference Monson, Parnell, Kucha and Landais1993), but the genesis has not been explained; the required barium may derive from alteration of feldspars, and the sulphur may have been introduced in the oil. As the source rocks are sulphur-rich (they contain replaced sulphate evaporites), the oil is likely to have been sulphur-bearing. The bitumen nodules occur in gneiss lacking any porosity excepting fractures, and must be replacive in nature, as observed in other cases elsewhere (Parnell et al. Reference Parnell, Monson and Tosswill1990). Penetration into the low-permeability gneiss emphasises the high fluid pressure under which hydrocarbons were emplaced.

4.5. Critical events in fractured basement reservoir filling

Several key factors have caused the Moinian basement to function as a fractured reservoir in the past:

(i) The basement experienced brittle fracturing due to movement on the basin bounding fault, which may have triggered the release of high fluid pressure.

(ii) The precipitation of quartz on the fracture walls propped the fractures open to create a network of interconnected secondary porosity.

(iii) Proximity to a compacting basin of sediments would have made the available fracture porosity a natural pathway for the expulsion of basinal fluids, including hydrocarbons.

The Moinian basement distant from the boundary fault (e.g., 3 km west at Rogie Falls, [NH 445584]; Fig. 1) lacks the fracture network found at Castle Leod, emphasising the importance of proximity to the fault for fracturing of the basement.

5. Conclusions

New data for organic biomarkers in the bitumens from the Moinian gneiss and the adjacent Devonian sediments help us to understand the origin of the bitumen. In particular:

(i) The occurrence of β-carotane, and relative abundance of C28 steranes, indicate correlation to a Devonian source rock.

(ii) The abundance of diasteranes and high pristane/nC17 indicates a high level of biodegradation.

(iii) Bitumens in the Devonian have lower diasterane/sterane and pristane/nC17 ratios, indicating less biodegradation than in the basement, which reflects more interaction with water in the basement.

The formation of bitumen veins, and abundant replacive bitumen nodules, implies high hydrocarbon fluid pressures. High pressures would have been generated when the Devonian shales entered the oil window. The occurrence of bitumen in E–W fault planes suggests that the migration may have been triggered during Permo-Carboniferous basin inversion.

6. Acknowledgements

MB is in receipt of a PTDF postgraduate studentship. The Figure from Mountrich (Fig. 10) was redrawn from a sketch by P Carey. J Johnston, J Bowie, C Taylor and J Still provided skilled technical support. Isotopic measurements were made at SUERC, East Kilbride, thanks to A Boyce and L Bullock. Help in the field was provided by J Armstrong, A Brasier and L Bullock. M Wilkinson and J Marshall kindly provided critical reviews, which helped to improve the manuscript.