Phytosaur skulls are abundant in the Upper Triassic Chinle Formation in the southwestern United States, especially those of pseudopalatine phytosaurs, the most derived clade of phytosaurs that includes various species that have been referred to Pseudopalatus Mehl, 1928 and Redondasaurus Hunt & Lucas, Reference Hunt, Lucas, Lucas and Morales1993. As a rough estimate, more than 75 skulls of these two genera have been recovered over the last hundred years in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas and Utah. This number represents approximately one-third of all phytosaur skulls known from North America. Given the abundance, it is striking how little information is available about the detailed cranial anatomy of this group. The seminal paper on phytosaur skull morphology is still Camp's (Reference Camp1930) study based on observations on the types of Smilosuchus gregorii (Camp Reference Camp1930) and Smilosuchus adamanensis (Camp Reference Camp1930). Because the configuration of the skull elements in many specimens of pseudopalatine phytosaurs, among them almost all type specimens, is rather imperfectly preserved, the majority of accounts deal more with the general appearance of the skull rather than with osteological details (Cope Reference Cope1881; Huene Reference Huene1915; Hunt & Lucas Reference Hunt, Lucas, Lucas and Morales1993; Long & Murry Reference Long and Murry1995; Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Heckert, Zeigler, Hunt, Heckert and Lucas2002). More recent accounts of older collections from Arizona (Heckert & Lucas Reference Heckert, Lucas, McCord and Boaz2000) and New Mexico (Zeigler et al. Reference Zeigler, Lucas, Heckert, Heckert and Lucas2002a, Reference Zeigler, Lucas and Heckert2003b) and recently discovered, well-preserved material of pseudopalatine phytosaurs from the Petrified Forest Member of the Chinle Formation and the Redonda Formation of New Mexico (Heckert et al. Reference Heckert, Harris, Lucas, McCord and Boaz2000; Zeigler et al. Reference Zeigler, Lucas, Heckert, Heckert and Lucas2002b, Reference Zeigler, Heckert, Lucas, Zeigler, Heckert and Lucas2003a) similarly provide few detailed osteological data. Parker & Irmis (Reference Parker and Irmis2006) have provided, to date, the most detailed cranial description of a North American pseudopalatine phytosaur, with their description of the partial skull of M. jablonskiae from the Petrified Forest. Other than that, the most informative overall studies of a pseudopalatine phytosaur from North America to date remain Camp's (Reference Camp1930) account on M. tenuis and Mehl's (Reference Mehl1922) description of M. andersoni. Parker & Irmis (Reference Parker and Irmis2006) defined a node-based clade for the Pseudopalatinae following Hungerbühler (Reference Hungerbühler2002). They defined the clade as Nicrosaurus, Mystriosuchus, Pseudopalatus, Redondasaurus, and all the descendants of their last common ancestor.

Here we present a detailed description of the cranial anatomy of the genus Machaeroprosopus on the basis of three skulls. The excellent preservation of the specimens provides a wealth of new morphological information on previously debated anatomical structures, in particular relating to the braincase and the palate, both regions of the skull that are either frequently inaccessible or rarely preserved because of their fragile nature. Moreover, two of the specimens represent a new species of Machaeroprosopus. They provide additional evidence for sexual dimorphism in phytosaurs, and their unusual combination of characters has important implications for the taxonomy of North American pseudopalatine phytosaurs.

Taxonomic note. Parker et al. (Reference Parker, Hungerbühler and Martz2013 (this volume)) demonstrate that Pseudopalatus Mehl, Reference Mehl1928 is a junior synonym of Machaeroprosopus Mehl, Reference Mehl1916. We argue below that there are good reasons to consider the genus Redondasaurus Hunt & Lucas, Reference Hunt, Lucas, Lucas and Morales1993 a junior synonym of Machaeroprosopus as well. Consequently, in the text we refer to all nominal species that are currently included in Pseudopalatus and Redondasaurus as species of Machaeroprosopus. We provisionally follow Stocker (Reference Stocker2010) in using the genus-group names Leptosuchus Case, Reference Case1922sensu strictu, Smilosuchus Long & Murry, Reference Long and Murry1995 and Pravusuchus Stocker, Reference Stocker2010 for taxa that were traditionally part of a more inclusive concept of Leptosuchus.

Institutional abbreviations. AMNH, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY; CM, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, PA; GPIT, Paläontologische Sammlung, University of Tübingen, Germany; NHMUK, The Natural History Museum, London, UK; NMMNH, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Albuquerque, NM; PEFO, Petrified Forest National Park, AZ; SMNS, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, Germany; TTU, Museum of Texas Tech University, Paleontology Division, Lubbock, TX; UCMP, University of California, Museum of Paleontology, Berkeley, CA; UMMP, Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI; UMo, University of Missouri, Department of Geological Sciences, Vertebrate Paleontology Collection, Columbia, MO; YPM Yale Peabody Museum, New Haven, CT.

1. Geological setting of the Patricia Site (locality number TTU VPL 3870)

Upper Triassic strata of the Dockum Basin are exposed along the eastern escarpment of the Southern High Plains in the Texas Panhandle, and continue along the western escarpment and the Pecos River Valley in eastern New Mexico. Researchers from New Mexico (e.g., Lucas & Hunt Reference Lucas, Hunt, Lucas and Hunt1989; Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Anderson, Hunt, Ahlen, Peterson and Bowsher1994, Reference Lucas, Heckert, Hunt, Lucas and Ulmer-Scholle2001) and Texas (Lehman Reference Lehman, Ahlen, Peterson and Bowsher1994a, Reference Lehmanb; Lehman & Chatterjee Reference Lehman and Chatterjee2005; Martz Reference Martz2008) advocate two competing stratigraphic schemes. We note that this debate is largely about priority and nomenclature, and both stratigraphic schemes agree that the units relevant here, the upper portion of the Cooper Canyon Formation in Texas and the Bull Canyon Formation in New Mexico, are equivalents in time. We follow the stratigraphic nomenclature as proposed by Lehman (Reference Lehman, Ahlen, Peterson and Bowsher1994a). Accordingly, the Dockum Group of Texas includes, in ascending order, four mappable units: the Santa Rosa Sandstone, the Tecovas Formation, the Trujillo Sandstone and the Cooper Canyon Formation (upper Cooper Canyon of Martz Reference Martz2008). A fifth and uppermost unit of the Dockum Group, the Redonda Formation, is restricted to eastern New Mexico and seems to grade eastward and southward into the upper part of the Cooper Canyon Formation.

The strata forming the Trujillo Sandstone and Cooper Canyon Formation represent a thick (maximum more than 150 m) alluvial depositional sequence, separated from the underlying Tecovas Formation by a locally angular unconformity. The basal part of the Trujillo Sandstone consists of thick, multistoried and laterally-extensive fluvial channel-sand bodies that reflect multiple phases of channel incision, lateral migration and aggradation. The Trujillo Sandstone grades and intertongues upward with an increasing proportion of fluvial flood-plain mudstone, and thus the overlying Cooper Canyon Formation is largely mudstone-dominated. Interbedded fluvial channel sandstone units in the Cooper Canyon Formation mostly reflect single phases of channel migration and aggradation, and so tend to be single-storied.

The Patricia Site TTU VPL 3870 served as an example for vertebrate bone accumulation in channel facies (Lehman & Chatterjee Reference Lehman and Chatterjee2005). The site is located about 13 km southwest of Post, in Garza County. Vertebrate fossils, along with carbonaceous plant remains, occur here within the upper part of the Cooper Canyon Formation, in channel deposits of fine-grained sandstone and green mudstone (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Patricia Site TTU Vertebrate Paleontology Locality 3870, Garza Co., Texas: (A) view of Site 1C, the locality of TTU-P10074; (B) composite section of Locality 3870, with depositional interpretation and the stratigraphic position of phytosaur specimens. Arrows indicate the position of the two characteristic conglomeratic beds that bracket the main fossiliferous strata.

The most abundant fossils collected from this site are phytosaurs, representing more than 90% of the identifiable remains. In addition TTU VPL 3870 yielded isolated remains of a palaeonisciform actinopterygian, a temnospondyl amphibian, the aetosaur Typothorax, the rauisuchid Postosuchus, the poposauroid Shuvosaurus and a theropod dinosaur (Cunningham et al. Reference Cunningham, Hungerbühler, Chatterjee and McQuilkin2002).

2. Systematic paleontology

Archosauriformes Gauthier, Kluge & Rowe, Reference Gauthier, Kluge and Rowe1988

Phytosauria Jaeger, Reference Jaeger1828sensu Reference NesbittNesbitt 2011

Phytosauridae Jaeger, Reference Jaeger1828sensu Doyle & Sues Reference Doyle and Sues1995

Pseudopalatinae Long & Murry, Reference Long and Murry1995sensu Parker & Irmis Reference Parker and Irmis2006

Machaeroprosopus Mehl, Reference Mehl1916

Synonyms.Arribasuchus Long & Murry, Reference Long and Murry1995; Pseudopalatus Mehl, Reference Mehl1928; Redondasaurus Hunt & Lucas, Reference Hunt, Lucas, Lucas and Morales1993.

Type species.Belodon buceros Cope, Reference Cope1881.

Diagnosis. Pseudopalatinae that are tentatively distinguished from the other pseudopalatine phytosaur genera Nicrosaurus and Mystriosuchus by several derived character states: ventrally convex suture of the maxilla with the premaxilla and nasal (also in Leptosuchus and Smilosuchus ssp.); exposure of supratemporal fenestra on skull roof reduced to narrow slit or entirely closed (also in Angistorhinopsis ruetimeyeri (Huene Reference Huene1911): Huene Reference Huene1922); distinct subsidiary opisthotic process of squamosal (also in Pravusuchus Stocker, Reference Stocker2010); lateral corner of posttemporal fenestra formed by squamosal, rather than by union of squamosal and paroccipital process; base of paroccipital process of opisthotic expands posteriorly in a sinuous curve, resulting in the exoccipital pillar being in extension of midline, rather than the posterior rim of the paroccipital process, and the posterior outline of the posttemporal fenestra being oblique rather than parallel to the axis of paroccipital process (also in Leptosuchus, Smilosuchus and Pravusuchus ssp.); basioccipital condyle receded under supraoccipital shelf and obscured in dorsal view (also in Leptosuchus, Smilosuchus and Pravusuchus ssp.); vomers on anterior half of interchoanal septum flat and broad, rather than narrow and sharp. The validity of these apomorphic characters as synapomorphies of Machaeroprosopus needs to be tested by a more comprehensive phylogenetic analysis.

Distribution. Restricted to the uppermost units of the Triassic of the southwestern USA (the stratigraphic nomenclature follows Parker & Martz (Reference Parker and Martz2011) for Arizona; Lucas (Reference Lucas1993, Reference Lucas, Dickins, Yang, Yin, Lucas and Acharyya1997) and Heckert & Lucas (Reference Heckert, Lucas, McCord and Boaz2000) for New Mexico; and Lehman (Reference Lehman, Ahlen, Peterson and Bowsher1994a) for Texas): Upper part of the Sonsela Member (Parker & Irmis Reference Parker and Irmis2006; Parker & Martz Reference Parker and Martz2011), Petrified Forest Member (Heckert & Lucas Reference Heckert, Lucas, Heckert and Lucas2002; Parker & Martz Reference Parker and Martz2011), and Owl Rock Member (Kirby Reference Kirby, Lucas and Hunt1989; Heckert & Lucas Reference Heckert, Lucas, McCord and Boaz2000; Parker & Martz Reference Parker and Martz2011) of the Chinle Formation of Arizona; Bull Canyon (Hunt Reference Hunt, Lucas and Ulmer-Scholle2001), Rock Point (Lucas & Hunt Reference Lucas, Hunt, Lucas, Kues, Williamson and Hunt1992), and Redonda (Hunt & Lucas Reference Hunt, Lucas, Lucas and Morales1993) Formations of north-central and eastern New Mexico; Cooper Canyon Formation of West Texas (Lehman & Chatterjee Reference Lehman and Chatterjee2005; this study).

Machaeroprosopus lottorum sp. nov.

(Figs 2–5, 7, 11–15, 18, 20–23)

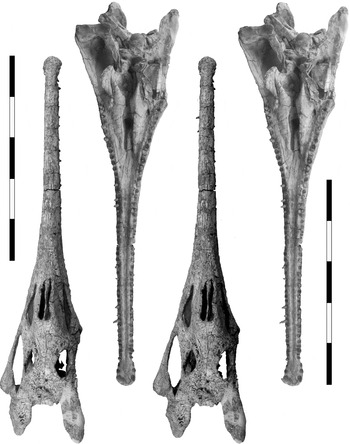

Figure 2 Stereopairs of the dorsal and ventral aspects of the skull of Machaeroprosopus lottorum TTU-P10076. Scale bars=100 mm.

Figure 3 Machaeroprosopus lottorum TTU-P10076: reconstruction of the skull in (A) ventral, (B) dorsal, (C) lateral and (D) occipital views. Scale bars=100 mm.

Figure 4 Stereopair of the dorsal aspect of the skull of Machaeroprosopus lottorum n. sp. TTU P-10077. Scale bar=100 mm.

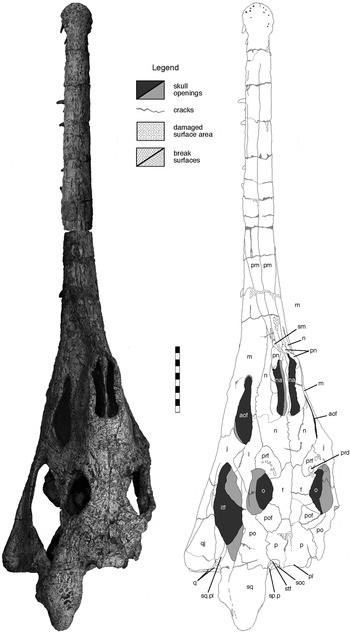

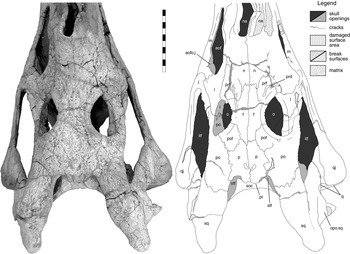

Figure 5 Machaeroprosopus lottorum TTU-P10076, skull in dorsal view. Scale bar=10 cm. Abbreviations: aof=antorbital fenestra; f=frontal; itf=infratemporal fenestra; j=jugal; l=lacrimal; m=maxilla; n=nasal; na=naris; o=orbit; p=parietal; pl=parietal ledge; pm=premaxilla; pn=paranasal; po=postorbital; pof=postfrontal; prd=preorbital depression; prf=prefrontal; q=quadrate; qj=quadratojugal; sm=septomaxilla; soc=supraoccipital; sp.p=squamosal process of parietal; sq=squamosal; sq.pl=squamosal platform; stf=supra-temporal fenestra.

Holotype. TTU-P10076, cranium.

Paratype. TTU-P10077, cranium, only referred specimen.

Type locality. TTU Vertebrate Paleontology Locality 3870 (exact locality data reposited at TTUP), 13 km South of Post, Garza County, Texas.

Type horizon. Upper part of the Cooper Canyon Formation, Dockum Group, Upper Triassic.

Age. Norian, Late Triassic.

Distribution. Restricted to type locality

Diagnosis.Machaeroprosopus lottorum is diagnosed by four characters which we interpret as autapomorphic for the taxon: (1) lateral rim of naris broad, flat, and rugose; (2) supratemporal fenestra fully closed in dorsal aspect, forming a shallow semicircular indentation into the skull roof (parietal, postorbital and squamosal) with strongly bevelled rim that continues onto the parietal; (3) free section of postorbital–squamosal bar (equalling in Machaeroprosopus the length of the dorsal surface of squamosal) short; (4) strongly developed horizontal medial laminae of palatines, that almost close the posterior section of the palatal vault in ventral view.

Differential diagnosis. In addition to the autapomorphic features, M. lottorum is distinguished from other species referred here to Machaeroprosopus by a number of characters that we assess as systematically important. The systematic validity of other variable features (see Table 1 and Appendix) is problematic because they differ in referred specimens from the type specimens (e.g., naris elevation: Camp Reference Camp1930; Zeigler et al. Reference Zeigler, Lucas, Heckert, Heckert and Lucas2002a, Reference Zeigler, Lucas, Heckert, Heckert and Lucasb, Reference Zeigler, Lucas and Heckert2003b) or they evidently vary within the hypodigms of other pseudopalatine taxa (see Hungerbühler Reference Hungerbühler1998). Machaeroprosopus lottorum differs from all species of Machaeroprosopus except M. gregorii by a comparatively broad dorsal surface of the squamosal; from both M. buceros (Cope Reference Cope1881), in which we include M. pristinus (Mehl Reference Mehl1928) and M. tenuis Camp Reference Camp1930, and from M. mccauleyi (Ballew Reference Ballew, Lucas and Hunt1989) by (1) the absence of a prenarial groove; (2) the lateral ridge of the squamosal being absent on the posterior process i.e., the dorsal and lateral surfaces of the process grade into each other; (3) a short and low rather than long and extensive flange of the squamosal; and (4) a rectangular rather than round top of the parietal–supraoccipital complex; in addition, from M. mccauleyi by (1) a shorter antorbital fenestra; (2) a parietal ledge that is twice as wide; and lateral walls of the parietal–supraoccipital complex that are (3) thick-based and (4) low; in addition, from M. buceros by a gently sloping rather than sinuous outline of the rostral crest in the morph with extended rostral crest; from both M. gregorii (Hunt & Lucas Reference Hunt, Lucas, Lucas and Morales1993) and M. bermani (Hunt & Lucas Reference Hunt, Lucas, Lucas and Morales1993) by a shorter and higher posttemporal fenestra; in addition, from M. gregorii by (1) a high posterior process of the squamosal with elevated dorsal surface; (2) a bulging lateral surface of this process; (3) a deep, rather than shallow supraoccipital shelf framed by squamosal processes of the parietals that are (4) sloping rather than vertical in their ventral section; and (5) the squamosal forming the lateroventral rim of the posttemporal fenestra by developing of a lamina onto the paroccipital process. M. lottorum differs from M. jablonskiae by having a lateral ridge on the squamosal, a knob-like tip on the squamosal, a rectangular outline of the parietal–supraoccipital complex, low lateral walls of the parietal–supraoccipital complex, and a beveled rim of the supratemporal fenestra that continues onto the parietal. A distinction from M. andersoni Mehl, 1922 is more difficult because of the incompleteness of the holotype of this species, but M. andersoni does not show the autapomorphic characters 1, 2, and 4 of M. lottorum, possesses a rounded, un-crested palatal ridge, and the maxillary furrow is absent.

Table 1 Character-taxon matrix used in the analysis of the phylogenetic position of Machaeroprosopus lottorum and TTU P10074. 0=primitive character state; 1, 2, 3=derived character states; A=character states 0 or 1; B=character states 0 and 1; ?=missing data.

Etymology. In honur of John Lott and Patricia Lott Kirkpatrick for their continuous support of this project.

2.1. Material and preservation

2.1.1. TTU-P10076 (Figs 2, 3)

Complete, 945 mm-long, slender-snouted and gracile cranium, including the most complete and informative dentition of a specimen of Machaeroprosopus known to date. The specimen was found lying on the left side and slightly tilted onto the skull roof, with the right posterior portion of the postorbital region broken up and scattered down the hill slope. Compaction resulted in a shearing of the skull to the right side, which affected in particular the narial region and the right postorbital region. The left side of the skull is thus flattened and appears more extended visually, the right side is verticalised. The right paroccipital process is crushed and was pushed dorsally. The right postorbital region was not reassembled with the cranium until after the description, to allow easy access to the braincase; it is not included in the figures. The cranium including the dentition is entirely freed of matrix.

2.1.2. TTU-P10077 (Fig. 4)

Almost complete, 1040 mm-long, robust cranium with a massive snout (altirostral sensu Hunt Reference Hunt, Lucas and Hunt1989, Reference Hunt1994). The skull was found dorsal side up and the occipital aspect partially was exposed, which explains the loss of the left squamosal and parts of the paroccipital processes and quadrates. The posterior portion of the narial region and the skull roof are crushed, and the entire skull is sheared to the right side. The skull deck was removed in pieces, prepared, and reassembled to its original shape. Similarly, the articular parts of both quadrates are kept separate from the skull. With exception of the rostrum, the skull is in parts strongly fragmented and the fragments are friable, the damage having been enhanced by root penetration. The fragments had to be fixed in their present distorted position before the matrix could be removed from the dorsal surface. On the ventral side, both tooth rows were fully exposed, but the palatal area is only prepared in broad outlines.

Machaeroprosopus sp.

Figure 6 Machaeroprosopus sp. TTU-P10074, postnarial part of the skull in dorsal view. Scale bar=10 cm. Abbreviations: aof=antorbital fenestra; aofo.j=jugular antorbital fossa; f=frontal; itf=infratemporal fenestra; j=jugal; l=lacrimal; m=maxilla; n=nasal; na=naris; o=orbit; opo.sq=opisthotic process of squamosal; p=parietal; pl=parietal ledge; po=postorbital; pof=postfrontal; prd=preorbital depression; prf=prefrontal; q=quadrate; qj=quadratojugal; soc=supraoccipital; sq=squamosal; stf=supra-temporal fenestra.

2.1.3. TTU-P10074

Almost undistorted slender-snouted cranium (dolichorostral sensu Hunt Reference Hunt, Lucas and Morales1993, Reference Hunt1994), lacking the anteriormost section of the rostrum because of surface exposure. A section of a right premaxilla including the alveoli pm4 (4th premaxillary alveolus) through pm6 was recovered later at the site and most likely belongs to this specimen. The cranium is entirely freed of matrix. The length is 815 mm from the anterior break of the premaxillae to the tip of the sqamosals; the total length is estimated to be 900 mm.

2.2. Description of Machaeroprosopus lottorum sp. nov.

The description of the cranial anatomy of Machaeroprosopus lottorum focuses on TTU-P10076, one of the best preserved skulls of this genus available to date. Additional information from TTU-P10077 is inserted at the appropriate places. The shape of a phytosaur skull traditionally is the more important part of its anatomy for comparative and phylogenetic purposes, and most previous studies focused on characters of the general skull morphology rather than on osteological details. For this reason, we feel justified in giving separate accounts of the external skull morphology, the major skull openings and important external structures that extend over several cranial elements. Structures that are restricted to single skull elements are described with the individual bones.

2.3. External skull morphology

2.3.1. Rostrum

In phytosaurs, the prenarial area includes the rostrum with the highly variable prenarial crest, if present. The area is shaped differently in the two specimens of M. lottorum, and both differ from that in TTU-P10074. In the slender-snouted (dolichorostral) TTU-P10076 (Fig. 5) and TTU-P10074 (Fig. 6), the rostrum is wider than high, flattened semicircular in outline, and narrows only insignificantly in anterior direction in the premaxillar section. The rostrum is almost imperceptibly curved upwards. In dorsal view, the outline is triangular with concave ventral rims of the maxillaries. A slight constriction marks the articulation of the premaxilla with the maxilla on the rostrum.

In TTU-P10076 (Fig. 7), the prenarial area drops steeply over a distance of 35 mm at an angle of 75° from the nares. A kink in the profile marks the point where the slope starts to level out in a gradual steady way, being level at 210 mm in front of the nares. The posterior one fourth of the slope is rounded, but narrow in cross-section, and visually demarcated from the ventral part of the rostrum by two lateral depressions below the narial cone. Anteriorly, the top surface increasingly grades into the rostrum, but is still distinguished visually by narrow extensions of this depression. It is only in the anterior one fourth that the slope merges with the rostrum to a semicircular cross-section as in TTU-P10074.

Figure 7 Machaeroprosopus lottorum TTU-P10076, skull in left lateral view. Scale bar=10 cm. Abbreviations: aof=antorbital fenestra; ect=ectopterygoid; f=frontal; itf=infratemporal fenestra; j=jugal; l=lacrimal; lsp=laterosphenoid; m=maxilla; n=nasal; n(r)=right nasal; opo.sq=opisthotic process of squamosal; pl=parietal ledge; pm=premaxilla; pn=paranasal; pn(l)=left paranasal; pn(r)=right paranasal; po=postorbital; pof=postfrontal; pop.opo=paroccipital process of opisthotic; pp.sq=posterior process of squamosal; prf=prefrontal; pt=pterygoid; q=quadrate; qj=quadratojugal; sm=septomaxilla; sm(l)=left septomaxilla; sm(r)=right septomaxilla; sopo.sq=subsidiary opisthotic process of squamosal; sq=squamosal; sq.pl=squamosal platform.

The left side of the prenarial area of TTU-P10077 (Fig. 4) is dislocated ventrally for 12 mm in front of the nares, but is undistorted otherwise. It slopes from the elevated anterior rim of the naris, situated 205 mm above the alveolar plane, at the gentle angle of 20° in a slightly undulating line to about the midpoint of the rostrum. Here, at a height of 80 mm, the slope changes fairly abruptly to continue at 3–4° to a point 140 mm in front of the tip of the rostrum, where the now 50 mm-high crest ends in a step. In the anterior half of the crest, the flanks are constricted by two large, triangular depressions, which separate the vertical top of the crest from the steeply sloping alveolar portions of the maxilla and premaxilla. The outline of the depression corresponds exactly with the prenarial section of the nasal, and is characterised furthermore by the deepest sculpture of the entire skull. In the anterior half, the crest grades into the steeply sloping flanks of the rostrum, resulting in a triangular cross-section. The top of the crest is narrow and sharp in front of the nares, but expands and becomes more rounded anteriorly.

2.3.2. Infraorbital area

The area just ventrally to the orbits, formed by the orbital process of the postorbital, the posterior section of the lacrimal behind the preorbital ridge and the orbital process of the jugal and leading into the preinfratemporal shelf, is distinguished in TTU-P10077 from the surrounding surface by the different surface sculpture. Most of the area is smooth, and forms a conspicuous strip set deeper than the flank of the naris and the preorbital area. A distinct feature is a narrow and deep groove along the rim of the infratemporal fenestra. In TTU-P10077, the posterior rim of the groove is drawn out to an extensive, laterally projecting flange. The groove is bounded posteriorly by a series of three ridges, which extend oblique to the long axis of the groove. Each of the ridges is separated by a distinct groove running into the infratemporal fenestra. TTU-P10076 lacks a differentiated infraorbital area (Fig. 7) and shows only a very faint groove.

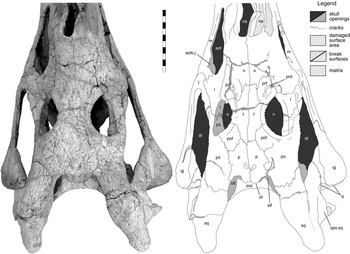

2.3.3. Parietal–supraoccipital complex. (Supraoccipital shelf, Figs 9, 10)

In posterior view, the shape of the parietal–supraoccipital complex in both TTU-P10076 and TTU-P10077 is rectangular, with a broad, horizontal parietal ledge. The lateral wall of the supraoccipital shelf, formed by the descending squamosal processes of the parietals, are vertical and, only in the ventral third of the complex they turn to the horizontal in a posterolateral direction in a gentle, steady curve. The supraoccipital shelf, including the supraoccipital and two lamella of the parietals, slopes continuously downward and posteriorly at an angle of 45°; the shelf is thus an inclined plane, neither curved and levelling out terminally as in Nicrosaurus and most specimens of Machaeroprosopus, nor vertical as in Mystriosuchus, Machaeroprosopus bermani and Machaeroprosopus gregorii.

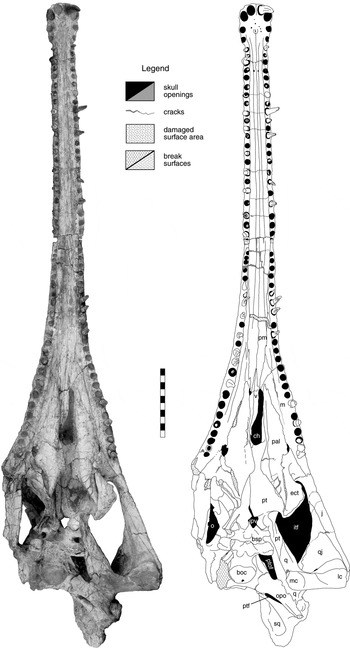

2.3.4. Palate. (Fig. 11.)

On the ventral surface of the rostrum of TTU-P10076, the raised alveolar ridges enclose a flat, wide interpremaxillary groove. About 50 mm anterior to the choana, the surface of the groove widens gradually and deepens to form the rounded concave prechoanal area. In the centre of the prechoanal area, the prechoanal section of the vomers is raised slightly to a broad elevated structure. The alveolar ridge parallels the tooth row medially, so closely that, in parts of the premaxilla, a concave indentation is formed opposite each alveolus. The ridge is asymmetrical, with vertical lateral and sloping medial rims. On the premaxilla and the anterior part of the maxilla, the ridge is broad, reaching a maximum width of 15 mm opposite maxillary alveolus 9 (m9). Here, an outward kink in the anterior third of the maxillary tooth row (opposite m12) effectively splits the alveolar ridge in two structures. The alveolar ridge continues along the diverging tooth rows, standing out as a much more prominent structure on the palate because of its now much diminished width. The height of the alveolar ridge also decreases rapidly, and it merges with the palatal plane in the posterior quarter of the maxilla (roughly opposite m19). A second sharp, but narrow and low ridge, on or parallel to the premaxilla–maxilla suture splits from the alveolar ridge and runs straight across the slope of the prechoanal area, converges slightly with the midline and disappears towards the raised prechoanal area.

The choanal and postchoanal palate is subdivided into two tiers: the lower tier of the horizontal palatal plane (including the palatine and the palatal parts of maxilla and ectopterygoid); and the dorsally arched, higher tier, which includes the choana (the choanal process of the maxilla, the interchoanal septum i.e., the anterior part of the vomers and the vertical dorsal ramus of the palatine), followed by the palatal vault (the posterior part of the vomer and the arched anterior ramus of the pterygoid).

The palatal plane is morphologically dominated by two elevations: the fading alveolar ridge and the raised ridge on the centre of the palatine. The palatine ridge extends anteriorly into the convex round, tapering tip of the element, and posteriorly into the overhang over the palatal vault to merge with the medial side of the pterygoid flange. These elevations frame an elongated depression, in which lies the suborbital fenestra. The midline of the semi-cylindrical palatal vault is elevated for 50 mm above the crest of the palatal ridge. The opening between the two halves of the palatal plane is 22–26 mm wide below the choana and the anterior half of the palatal vault. Because of the extensive overhang of the palatines, the palatal vault is actually much wider (60 mm). Posteriorly, the exposure of the palatal vault is constricted severely in TTU-P10076. The width increases posteriorly to 65 mm because of the divergence of the palatines. With the emergence of the pterygoid flange (the ventral ramus of pterygoid and ectopterygoid, plus the posterior tip of the palatine) out of the walls of the palatal vault and the horizontal overhang of the palatine, both horizontal tiers merge into a unified vertical structure.

2.4. Skull openings

2.4.1. Nares and associated structures

The nares of all specimens are considerably elevated above the centre of the skull roof (for 15 mm in TTU-P10076). The septomaxilla forms most of the internarial septum and the anteromedial rim of the naris; an additional bony element, named here the paranasal, occupies the anterolateral border to a variable extent (see below), and the nasal forms most of the lateral and the entire posterior rim.

The subrectangular naris of TTU-P10076 (Fig. 12C) is long (83–85 mm), but narrow, reaching a maximum width of 15 mm close to the posterior border. It extends about 10 mm anterior to the level of the anterior rim of the antorbital fenestra. Anteriorly, the naris is indented as a distinct, 20 mm-deep and 5 mm-broad, V-shaped outlet (Fig. 12C, ‘nou’). The anteriormost section of the lateral rim is thin and sharp. The lateral rim is straight and slopes slightly in anterior direction, the anterior rim being 11 mm lower than the posterior. In both TTU-P10076 and TTU-P10077, most of the rim is squared in dorsal aspect and deeply rugose by predominantly transverse, irregular grooves, suggesting the presence of a cartilaginous structure (Fig. 12). The narial cone seems to be slightly constricted at midlength, and shows two symmetrical, flat and broad depressions below the anterior third, which enhances the cone-like appearance of the narial bulb. The internasal septum is thin, posteriorly with a sharp edge that grades into a smoothly rounded but still narrow rim anteriorly. The dorsal rim is straight throughout and situated a few mm below the lateral rims of the nares.

A raised central prenarial hump anterior to the nares, including parts of the internarial septum, or a pair of paramedian prenarial grooves extending onto the rostrum out of the narial outlets, are absent in M. lottorum and TTU-P10074.

2.4.2. Orbit and preorbital ridge

The orbit is surrounded by the prefrontal anterodorsally, the frontal dorsally, the postfrontal posterodorsally, the postorbital posteriorly, and the lacrimal ventrally (Fig. 13). The jugal is excluded from the orbit in both specimens of M. lottorum and TTU-P10074. The undeformed orbit is oval, with a conspicuous straight and flat ventral rim and a long axis directed anteroposteriorly (Fig. 2). The plane circumscribed by the opening faces laterally and, for about 20 to 30 degrees, upward; the orbits are not turned anteriorly to any degree, and thus there is no indication of binocular vision. With to exception of the broad and smooth ventral rim, the orbital rim is sharp and raised above the surrounding skull surface, forming a conspicuous, 10 mm-broad, less sculptured zone around the opening. The elevation is particularly strong at the posterodorsal corner, in the form of an extensive hump, especially pronounced in TTU-P10074, and along the anterior rim. This anterior orbital ridge causes the preorbital depression (Fig. 6, ‘prd’), here, in contrast to the pseudopalatine phytosaur Mystriosuchus (GPIT 261/001; Hungerbühler Reference Hungerbühler2002), actually a series of smaller, deep pits separated by bridges of the surface sculpture. The ridge continues ventrally to the anterior corner of the antorbital fenestra onto the lacrimal, where it marks the anterior border of the less sculptured infraorbital area.

2.4.3. Antorbital fenestra and antorbital fossa

In TTU-P10076, the antorbital fenestra is surrounded anterodorsally by the dorsal, and ventrally by the ventral processes of the maxilla, the lacrimal posterodorsally, and the jugal posteriorly and posteroventrally (Figs 7, 12A, B, 13). The opening is oval, with an angular rather than round posterior corner. In the undeformed openings, the long axis, which is positioned at a low angle with the axis of the skull, measures 106 mm, the short axis 43·5 mm; the size is comparatively small for phytosaurs, with reference to naris length. The ventral edge is prominent and sharp, whereas the dorsal rim is broadly rounded and deep. TTU-P10076 (as is Machaeroprosopus sp. TTU-P10074) is among the few specimens of pseudopalatine phytosaurs that show remnants of an antorbital fossa. The anterodorsal part of the fossa appears as a small depression on the lateral face of the maxilla (Figs 7, 8, 12A; ‘aofo.ml’). Further posteriorly, the dorsal process of the maxilla and the anterior process of the lacrimal are folded over, forming the broad dorsal rim of the antorbital fenestra, but continue as a steeply medioventrally sloping plane, a 15 mm-deep maxillo–lacrimal antorbital fossa as overhang over the antorbital fenestra proper (Fig. 12A, C). In addition, there is a distinct jugular fossa in the posteroventral corner extending along the posterior rim of the antorbital opening, in the form of a narrow, thin lamella medial to the lacrimo–jugular rim of the antorbital fenestra, both of which enclose a deep, V-shaped recess (Fig. 12C, ‘aofo.j).

Figure 8 Machaeroprosopus sp. TTU-P10074, postnarial part of the skull in left lateral view. Scale bar=10 cm. Abbreviations: aof=antorbital fenestra; aofo.ml=maxillo-lacrimal antorbital fossa; ect=ectopterygoid; f=frontal; itf=infratemporal fenestra; j=jugal; l=lacrimal; m=maxilla; n=nasal; opo=opisthotic; opo.sq=opisthotic process of squamosal; pm=premaxilla; pn=paranasal; po=postorbital; pof = postfrontal; pp.sq = posterior process of squamosal; ppr.sq=parietal process of sqamosal; prf=prefrontal; pt=pterygoid; q=quadrate; qj=quadratojugal; sm=septomaxilla; sm(l)=left septomaxilla; sm(r)=right septomaxilla; sq=squamosal.

2.4.4. Supratemporal fenestra

The supratemporal fenestra is bounded by the parietal anteriorly, the postorbital and the medial lamella of the squamosal laterally, the parietal ledge medially, and the sloping squamosal process of the parietal and the horizontal parietal process of the squamosal posteriorly (Fig. 13). Because of the elongated squamosal, the posterior rim is actually positioned posterolaterally, and it is depressed on the undeformed right side for 36–42 mm below the level of the skull roof, or for about 30% of the skull height. In all specimens, the anterior rim of the fenestra is shallow, but broad compared to other species previously referred to Pseudopalatus. It forms a semicircular, 13 mm-deep excavation in TTU-P10076 (Fig. 5) that hardly indents the skull roof proper, i.e., the parietal. The excavation is, rather, caused by the projection of the parietal ledge to the rear. In both TTU-P10076 (Figs 5, 9) and TTU-P10077, the rim is distinctly bevelled, the ventral edge almost spanning the entire indentation. Thus, the supratemporal opening is in M. lottorum and TTU-P10074 effectively closed on the skull roof, and all three specimens are more derived than the deeper, slit-like, straight or medially curved openings seen in the type specimens of M. buceros, M. mccauleyi, M. jablonskiae and M. andersoni. The maximum length of the opening to the posterior extent of the paroccipital process is 85 mm, of which the posterior 50 mm are completely recessed below the horizontal surface of the squamosal (i.e., under the dorsal sulcus; Figs 9, 10) and are not visible in dorsal view. The supratemporal fenestra opens thus almost exclusively to the rear.

Figure 9 Machaeroprosopus lottorum TTU-P10076, skull in occipital view. Scale bar = 50 mm. Abbreviations: boc = basioccipital; bpt.bsp = basipterygoid process of basisphenoid; bpt.pt = basipterygoid process of pterygoid; bsp = basisphenoidal part of parabasisphenoid; cr = central ridge of quadrate; ds = dorsal sulcus; ect = ectopterygoid; eoc = exoccipital; fl.sq = squamosal flange; fm = foramen magnum; f.pat = facet for proatlas; fq = quadrate foramen; itf = infratemporal fenestra; j = jugal; la.p = lamina of parietal; lc = lateral condyle of quadrate; m = maxilla; mc = medial condyle of quadrate; nc = narial cone; opo.sq = opisthotic process of squamosal; p = parietal; pl = parietal ledge; po = postorbital; pop.opo = paroccipital process of opisthotic; pp.sq = posterior process of squamosal; ppr.sq = parietal process of squamosal; pro = prootic; ptf = posttemporal fenestra; ptof = pteroccipital fenestra; ptr.q = pterygoid ramus of quadrate; q = quadrate; qj = quadratojugal; qr.pt = quadrate ramus of pterygoid; r = recess; soc = supraoccipital; sopo.sq = subsidiary opisthotic process of squamosal; sp.p = squamosal process of parietal; stf = supra-temporal fenestra; vr.pt = ventral ramus of pterygoid; vs = ventral sulcus.

Figure 10 Machaeroprosopus sp. TTU-P10074, skull in occipital view. Scale bar = 10 mm. Abbreviations: boc = basioccipital; bpt.bsp = basipterygoid process of basisphenoid; cr = central ridge of quadrate; eoc = exoccipital; fl.sq = squamosal flange; fm = foramen magnum; fq = quadrate foramen; la.p = lamina of parietal; lc = lateral condyle of quadrate; l.sq = lamella of squamosal onto paroccipital process of opisthotic; mc = medial condyle of quadrate; opo.sq = opisthotic process of squamosal; p = parietal; po = postorbital; pop.opo = paroccipital process of opisthotic; pp.sq = posterior process of squamosal; ppr.sq = parietal process of squamosal; ptf = posttemporal fenestra; ptof = pteroccipital fenestra; ptr.q = pterygoid ramus of quadrate; q = quadrate; qj = quadratojugal; qr.pt = quadrate ramus of pterygoid; soc = supraoccipital; sopo.sq = subsidiary opisthotic process of squamosal; stf = supra-temporal fenestra; vr.pt = ventral ramus of pterygoid; vs = ventral sulcus.

2.4.5. Infratemporal fenestra

The infratemporal fenestra is bounded by, clockwise from the orbit, the postorbital, squamosal, quadratojugal and jugal (Fig. 13). The opening roughly forms a parallelogram with a concave dorsal rim, the anterodorsal corner being located below the centre of the orbit. The fenestra extends far forward in TTU-P10077 (and TTU-P10074; Fig. 8), the anteroventral corner being 10 mm in front of the anterior orbital rim, but terminates level with the orbit in TTU-P10076 (Fig. 7).

2.4.6. Posttemporal fenestra

The posttemporal fenestra of TTU-P10076 is short and oval, with a flat dorsal rim, 27 mm by 11 mm wide (Fig. 9). The opisthotic–squamosal suture is located in the angular medial corner of the fenestra. The parietal process of the squamosal forms the entire dorsal rim of the posttemporal fenestra, the paroccipital process of the opisthotic two thirds and an extension of the squamosal the lateral third of the concave ventral rim. The fenestra is set somewhat oblique with respect to the axis of the paroccipital process: the lateral corner is located deeper, and the lateral section of the fenestra is thus strongly roofed over by the parietal process of the squamosal. The rounded lateral rim grades smoothly into the ventral sulcus.

2.4.7. Foramen magnum. (Fig. 9.)

The foramen magnum is a transversely oval opening (TTU-P10076: 21 mm by 15·5 mm). The supraoccipital shelf overhangs the foramen magnum by 15 mm in both specimens. The condylar parts of the exoccipitals extend posteriorly, resulting in a concave posterior edge of the exoccipital pillars, and thus forms a distinct, slightly concave platform in front of the foramen.

2.4.8. Choana. (Fig. 11.)

The undistorted subrectangular left choana is 73 mm in TTU-P10076, and thus subequal in length with the naris. The posterior rim is exactly below the posterior rim of the naris, but the anterior rim extends further forward. Because of the vaulting of the prechoanal palate, the anterolateral rim of the choana formed by the maxilla is curved upward and, at the same time, widens in a broad lateral recess, being slightly overhung by the anterior section of the palatine. In the posterior two thirds, an extensive vertical lamella of the palatine forms a lateral wall. The palatine and the vomers also form the posterior rim. The interchoanal septum formed by the vomers is a 9–11 mm-broad, flat or slightly convex ventral plane, the ascending medial walls of the choana converge at each other and the septum becomes much narrower internally. At midlength, the septum narrow considerably and curves upward in a step-like fashion to level out on the deeper level of the palatal vault. Thus, the choana expands from 9 mm to 15 mm in width, and the plane of the opening is bent in the vertical plane.

Figure 11 Machaeroprosopus lottorum TTU-P10076, skull in ventral view. Scale bar=10 cm. Abbreviations: boc=basioccipital; bsp=basisphenoidal part of parabasisphenoid; ch=choana; ect=ectopterygoid; ipv=interpterygoid vacuity; itf=infratemporal fenestra; j=jugal; lc=lateral condyle of quadrate; m=maxilla; mc=medial condyle of quadrate; o=orbit; opo=opisthotic; pal=palatine; pm=premaxilla; pt=pterygoid; ptf=posttemporal fenestra; ptof=pteroccipital fenestra; q=quadrate; qj=quadratojugal; sq=squamosal; v=vomer.

2.4.9. Suborbital fenestra

In TTU-P10076, the area of the suborbital fenestra is fractured on the right side and the left side is cracked and the palatine telescoped underneath the palatal section of the maxilla. The suborbital fenestrae are well-delineated (Fig. 11). The suborbital fenestra lies on the palatal plane between the maxilla and the palatine, about 10 mm behind the choana (Fig. 14, ‘sf’). The opening is reduced compared to that of non-pseudopalatine phytosaurs, and appears as a narrow oval fenestra 17 mm by 7 mm wide, with pointed anterior and posterior corners. The maxilla forms the anterior and the ectopterygoid the posterior half of the lateral rim, while the palatine borders the opening laterally.

2.4.10. Subtemporal fenestra. (Fig. 11)

According to the less deformed right side, the subtemporal fenestra of TTU-P10076 is the large ventral, anteroposteriorly elongated opening of the adductor chamber. The shape is subrectangular with an oblique, posteromedially trailing margin and posteriorly slightly converging walls. It is bordered anteriorly by the broadly rounded palatal part of the ectopterygoid, and medially by the ventral surface of the pterygoid–quadrate plate (predominantly the pterygoid ramus of the quadrate). The quadrate forms the posterior margin and the jugal the lateral margin, with the quadratojugal contributing to the posterolateral corner.

2.4.11. Interpterygoid vacuity

The interpterygoid vacuity is reduced to a roughly 35 mm-long, roughly heart-shaped opening (Fig. 14). On the roof of the palatal vault, the vacuity indents the pterygoids in a 10-mm long, tapering slit. The concave lateral rims are formed by the basipterygoid processes of the pterygoids. The notch between the basipterygoid processes of the parabasisphenoid marks the posterior limit.

2.4.12. Pteroccipital fenestra. (Fig. 9)

The pteroccipital fenestra is a narrow, predominantly ventrally- and somewhat posteriorly-facing passage between the pterygoid–quadrate plate and the braincase. It is crescentic in outline, with straight lateral and convex medial rims. As an estimate, the length is 70 mm and the maximum width is 20 mm, although the latter is somewhat exaggerated by deformation in all specimens. The passage is framed laterally by the dorsal rim of the pterygoid–quadrate plate, anteriorly by the lateral edge of the basipterygoid process of the parabasisphenoid, and medially by the anterior wall of the stapedial groove and the base of the paroccipital process.

2.5. Individual elements

2.5.1. Premaxilla

The elongated subrectangular terminal rosette of the premaxillae is longer than wide, terminating by a slight constriction (Fig. 11). It is only moderately expanded laterally, being 47 mm wide, with a width of the rostrum of 31 mm at the constriction. The premaxillae curve ventrally to a moderate degree in front of pm3, the tip being situated 24 mm below the level of the alveolar plane (Fig. 7). In anterior view, the total height of the terminal rosette is subequal to the width (44·5 mm). The slender rostrum widens gradually from 33 mm at pm5 to 46 mm at the end of the premaxillae; there is an almost imperceptible lateral convexity along the last five premaxillary alveoli.

The suture between the premaxillae is present as a groove on the anterior surface of the rosette and along most of the dorsal surface of the rostrum, but the bones are fused without an external trace over the distance of 90 mm in the anterior section above pm3 to pm9 (Fig. 5). A well developed longitudinal groove with a rectangular cross-section is present on the lateral surface of the rostrum between pm10 and pm18, about 10 mm above the alveolar plane (Fig. 7). Anteriorly and posteriorly, the groove is dissociated into an array of short grooves or depressions. In a somewhat irregular pattern, foramina in the grooves and depressions enter into the rostrum, on average at every second tooth position. Some foramina take on the shape of fairly long slits. Because of the dorsal expansion of the maxillae, the posterior section of the premaxillae is developed as a narrow extension on the top of the rostrum. Posteriorly, each element splits into two tapering processes: a broader and shorter medial process along the median plane that is wedged for 13 mm between the septomaxillae, and a larger, narrower process that extends for about 20 mm on the lateral side of the crest between the septomaxilla and the nasal (Fig. 12A, C). The opposite is the case in TTU-P10077 (Fig. 15). The dorsal (medial) process is narrower, non-tapering, and 37 mm long, of which 20 mm are represented by a thin prong along the midline. The stout ventral (lateral) process is twice as broad, subequal in length, extends horizontally below the septomaxilla, and forms an anteroventrally sloping suture with the nasal. Moreover, a deep and narrow furrow, in parts resembling an almost closed channel, extends for 75 mm on both sides on the premaxilla, in extension of the ventral septomaxilla–premaxilla contact. Such a groove has not been identified before in, and is not homologue with, the prenarial groove of other phytosaurs, which extends out of the nares on the septomaxillae and nasals.

Figure 12 Machaeroprosopus lottorum TTU-P10076: details of the narial area in (A) lateral left view; (B) lateral right view; (C) anterolateral left view. Scale bars=50 mm. Abbreviations: aof=antorbital fenestra; aofo.j = jugular antorbital fossa; aofo.ml=maxillo–lacrimal antorbital fossa; f=frontal; f.pn=facet for paranasal; g=groove; itf=infratemporal fenestra; j=jugal; l=lacrimal; m=maxilla; n=nasal; nou=narial outlet; o=orbit; pis=preinfratemporal shelf; pm=premaxilla; pn=paranasal; po=postorbital; prd=preorbital depression; prf=prefrontal; sm=septomaxilla.

The interpremaxillary groove (Fig. 11), starting between both pm5, is rounded in cross-section anteriorly, but rapidly develops into a flat-bottomed channel posteriorly. The unpaired foramen incisivum is located on a central mound between pm3 and pm4. Anteriorly and laterally, there is a series of three (left) and two (right) nutritious foramina. A conspicuous pair of foramina that open posteriorly is situated in the bottom of the interpremaxillary groove at the level of pm8 (Fig. 11). The palatal surface of the premaxilla extends into a thin, tapering palatal process that runs on the maxilla (illustrated in TTU-P10074, Fig. 16A, ‘pap.pm’) and reaches the tip of the choana, overlapping the vomer medially (Fig. 11).

2.5.2. Maxilla

The maxilla appears on the lateral surface, forming two sharp, anteriorly-pointing, subequally long prongs that interdigitate with the premaxilla (Fig. 7). Posteriorly, the suture curves more and more dorsally, until the maxilla extends over two thirds of the height of the prenarial area and levels out into the narrow dorsal process above the antorbital fenestra, firmly sutured by a strongly serrated suture with the nasal. In TTU-P10077 (Fig. 15), the maxilla bulges distinctly along the posterior part of the premaxilla and the nasal in a strongly convex suture. This section of the element is extremely thin, being 2 mm thick medio-laterally in TTU-P10074 (Fig. 16A). The base of the dorsal process is marked by a concavity of the nasal-maxillary suture, and the process continues with a restricted width of 11 mm. TTU-P10077 (and Machaeroprosopus sp. TTU-P10074) show a peculiar sturdy prong of the maxilla into the premaxilla in front of the apex of the suture. The prong is absent in TTU-P10076, and the nasal–maxillary suture is almost straight (Fig. 12). The surface of the much higher ventral process is vertical and extends far posteriorly, forming two thirds of the antorbital rim, and meets the jugal in a subvertical suture, the ventral section of which trails obliquely toward the jugal notch.

On the ventral surface, the suture between maxilla and premaxilla appears laterally to alveolus m1, curves closely in front around the alveolus and extends posteriorly in the lateral edge of the alveolar ridge (Fig. 11). It crosses the ridge obliquely opposite to alveoli m4 to m12 and heads obliquely on a ridge over the prechoanal depression, straight towards the anteromedial corner of the choana. This choanal process extends, sloping to the midline and posteriorly because of the concavity of the prechoanal palate, between the tip of the palatine laterally and the palatal process of the premaxilla and the vomer medially. It forms the anterior rim of the choana, and continues below the palatine on the lateral side of the opening for 21 mm; i.e., for one fourth of the choana length. The contribution of the maxilla to the choanal rim is thick and rounded, and the anterolateral rim is concave, resulting in a broadened lobate expansion of the anterior part of the choana below the tip of the palatine. The suture with the palatine runs parallel to the alveolar rim in the elongate depression of the palatal plane to the suborbital fenestra. The maxilla continues along the base of the ectopterygoid, overlapping the bone, straight towards the anterolateral corner of the subtemporal fenestra, and ends in a blunt tongue lying ventrally on the ectopterygoid–jugal complex.

Figure 13 Machaeroprosopus lottorum sp. nov.: schematic reconstruction of the skull and the configuration of the cranial elements in (A) ventral, (B) dorsal, (C) lateral and (D) occipital views. Scale bars=100 mm.

Figure 14 Machaeroprosopus lottorum TTU-P10076: (A) right palate in ventral view; (B) with pterygoid flange removed, showing the steinkern of the sinus between ectopterygoid and palatine. Scale bars=50 mm. Abbreviations: ch=choana; ect=ectopterygoid; g=groove; ipv=interpterygoid vacuity; m=maxilla; pal=palatine; pt=pterygoid; sf=suborbital foramen; si=sinus; vr.ect=ventral ramus of ectopterygoid; vr.pt=ventral ramus of pterygoid.

Figure 15 Machaeroprosopus lottorum TTU P-10077, left anterial narial and prenarial region. In the interpretive drawing, the right side is not shown. Scale bar=50 mm. Abbreviations: m=maxilla; n=nasal; pm=premaxilla; pn=paranasal; sm=septomaxilla.

Figure 16 Machaeroprosopus sp. TTU-P10074: (A) cross-section through the rostrum 75 mm in front of the nares, view in anterior direction. Transverse break-surfaces unshaded, arrows indicate position of sutures on the outside; (B) counterpart of the right dorsal part of the same section to show the sutural configuration, view in posterior direction; (C) right prenarial area in lateral view. Scale bars = 10 mm. Abbreviations: ac = alveolar canal; ar = alveolar ridge; c.pm = premaxillary cavity; cv.m = maxillary cavern; cv.n = nasal cavern; m = maxilla; m12 = alveolus 12 of maxilla; m14 = alveolus 14 of maxilla; n = nasal; pap.pm = palatal process of premaxilla; pm = premaxilla; sm = septomaxilla; sm(l) = left septomaxilla; sm(r) = right septomaxilla.

Figure 17 Machaeroprosopus sp. TTU-P10074, cross-section through the rostrum 195 mm in front of the nares, view in anterior direction. Scale bar = 10 mm. Abbreviations: ac = alveolar canal; ar = alveolar ridge; c.pm = premaxillary cavity; ipmg = interpremaxillary groove; m = maxilla; m2 = alveolus 2 of maxilla; pm = premaxilla.

2.5.3. Septomaxilla

The sutural configuration of the immediate prenarial area is difficult to interpret in the slender-snouted TTU-P10076 because of fractures, intense superficial damage, the sculpturing and the lamellate interdigitation of the constituent elements. The septomaxilla forms much of the internarial septum and extends forwards, wedged between the paranasal, the nasal and the premaxilla.

The septomaxillae are asymmetrically developed on the internasal septum of TTU-P10076 (Fig. 12C). Thirty mm behind the anterior rim of the naris, the suture between the septomaxillae drops vertically on the right flank of the septum, which is, from this point backwards formed by the left septomaxilla alone. The suture with the nasal appears on the septum 27 mm in front of the posterior rim, running horizontally, and ascends to the dorsal surface right at the posterior rim of the opening.

In the anteriormost section of the naris, the septomaxilla forms a laterally concave flange, the floor of the narial outlet, and abuts against the paranasal. Externally, the septomaxilla extends as a thin strip forwards along the midline, apparently intensively covered by the paranasal. The element triples in width in front of the paranasal and seems to terminate 70 mm in front of the naris, at about the level of the anterior tip of the nasal (TTU-P10076, right side; Fig. 12C). Surface damage to the bone on the left side reveals several parallel suture lines (Fig. 12A, C) that mark the intensive interdigitation with the underlying premaxilla, as in Smilosuchus gregorii UCMP 27200 (Camp Reference Camp1930). On both sides, the sutures between the septomaxilla and the paranasal extend out of the naris through the narial outlets, separating two 4 mm narrow elements. The septomaxillae widen to 9 mm at 75 mm in front of the nares (gradually on the right side, abruptly at a point 40 mm in front of the naris on the left side), extending further forward than the nasal. The length of the septomaxilla of TTU-P10077 compares with that of TTU-P10076, but the element is much broader. It is still 14 mm wide at the anterior end, where it broadly interdigitates with the dorsal process of the premaxilla, and a bulge of the lateral rim down the flank of the rostral crest results in a maximum width of 28 mm.

2.5.4. Paranasal

An additional discrete skull element is outlined clearly in the anterior lateral corner of the nasal opening of TTU-P10076 (Fig. 12) and TTU-P10077 (Fig. 15). We refer to this element as the paranasal bone. It forms the thick, pillar-like anterior rim of the naris and the anteriormost part of the narial flank. The element is triangular in outline, with a blunt, ventrally pointing tip. The medial side lies on the septomaxilla and forms the lateral wall of the narial outlet. Laterally and posteriorly, it is overlapped by the nasal, forming a short squamal suture, as evidenced by the partially exposed sutural contact on the left side of TTU-P10076, and the oblique course over the dorsal rim of the naris (Fig. 12C). The posterior extent is restricted to the anterior one fourth of the side of the naris in TTU-P10076. In TTU-P10077, the nasal is detached from the paranasal along the posterior section of the suture line and crushed down, and extends externally along the anterior third of the naris. A cross-section of the narial rim reveals (Fig. 15, inset) that the nasal underlies the paranasal and reaches forward to a point 15 mm behind the anterior corner of the naris. This suggests that the extent of the paranasal may vary by expanding over the nasal. The element seems to be present also in TTU-P10074, according to a sigmoidal suture line on the left side that separate the anterior third of the lateral narial rim from the nasal (Fig. 8).

2.5.5. Nasal

The nasal is an extensive element that forms much of the interorbitonasal area and the narial cone. Anteriorly, the nasal is wedged as a thin, tapering prong between the convex maxilla and the posteriormost section of the premaxilla, terminating 75 mm in front of the naris (Fig. 7). The bone expands, however, much deeper internally below the premaxilla and the dorsal process of the maxilla, meets its counterpart along the midline, and forms much of the roof of the large antorbital cavity here (Fig. 12B); similarly, a thin wedge of the nasal is exposed in TTU-P10076 between the septomaxilla and the posterior lateral process of the premaxilla (Fig. 12A, C). In this region, the nasal contains a broad, dorsoventrally-compressed cavern that extends into the base of the premaxilla. The cavern extends posteriorly at least to a point 75 mm in front of the naris, and communicates with the antorbital cavity by means of narrow canals (Fig. 16A, B). The nasal forms the posterior three fourths of the lateral rim and the entire posterior rim of the naris, but seems to contribute little to the internasal septum. Posterior to the nares, the width of the nasal is restricted by the lacrimal, but in particular by the prefrontal posterolaterally to two processes that contact the frontal 10 mm in front of the orbit.

2.5.6. Frontal

Both frontals, are cross-shaped, as is typical for phytosaurs (Fig. 5). The subequally long anterior and posterior processes are wedged between the nasals and prefrontals, and the parietals and postfrontals, respectively. There is a remarkable left–right asymmetry in TTUP-P10076 (as is in TTU-P10074) regarding the length of these posterior processes. The orbital wing of each element expands laterally and dorsally to the centre of the raised dorsal rim of the orbit; both frontals thus enclose a depressed concave interorbital area. The interfrontal suture is located on a low and broad elevation along the midline of the skull.

2.5.7. Prefrontal

The prefrontal is about 1·5 times longer than the postfrontal. The element restricts the width of the posteriormost section of the nasal anteromedially and the anterior process of the frontal medially on the dorsal plane of the skull (Fig. 5), and extends onto the lateral side to form the anterodorsal and entire anterior rim of the orbit. At the level of the ventral rim of the orbit, the prefrontal meets the lacrimal; the suture is convex in TTU-P10076 (Fig. 7).

2.5.8. Lacrimal

The lacrimal is an elongated, but low element. The high anterior process forms the posterior section of the dorsal antorbital rim, including the inclined dorsal antorbital fossa (Fig. 12B). The process tapers slightly anteriorly to meet and interdigitate with the dorsal process of the maxilla at about midlength of the antorbital fenestra. The lacrimal is bounded dorsally by the posterior section of the nasal, and the prefrontal in a distinctly convex suture at the level of the ventral rim of the orbit, which results in a dorsally-directed prong between the nasal and the prefrontal. The lacrimal forms the anterior half (TTU-P10076) of the ventral orbital rim, and does not contribute to the anterior rim. Because of extensive fragmentation, no information is preserved regarding the opening of the lacrimal canal, which in phytosaurs is usually placed internally in the anteroventral corner of the orbit, at or close to the joint of lacrimal and prefrontal (Case Reference Case1929; Camp Reference Camp1930; Case & White Reference Case and White1934; Witmer Reference Witmer1997; Senter Reference Senter2002). The ventral process is absent in TTU-P10076 (Fig. 7), and does not contribute to the antorbital fenestra.

2.5.9. Jugal. (Fig. 7)

The maxillary process of the jugal is short and high. There is no jugal notch developed at the maxilla–jugal suture, but only a slight concavity of the ventral rim. The jugal contributes only to about one fourth of the ventral rim of the antorbital fenestra. The posteroventral antorbital fossa is exclusively in the jugal (Fig. 12C). The jugal forms here a thin lamina, 8 mm medial to the the posterior rim of the antorbital fenestra, that ascends parallel to the rim. The maximum width of the lamina is 7 mm. With the outer rim of the antorbital fenestra, it encloses a recess that leads into an ascending groove. A preinfratemporal shelf is present, but poorly defined in TTU-P10076. In the anteroventral corner of the infratemporal fenestra, the jugal holds a deep, posteriorly-facing oval recess enclosed by the bases of the quadratojugal process and the jugal process of the ectopterygoid. The orbital process is slender, and extends along the lacrimal in an ascending, slightly serrated suture to contact the postorbital about 25 mm below the orbit in a posterodorsally trailing suture. The jugal is thus excluded from the orbit. Posteromedially, the orbital process forms much of an extensive, 25 mm-broad medially-directed flange along the postorbital–jugal bar, and thus a deep, posteriorly-facing area developed as the anterior wall of the infratemporal fenestra. The jugal continues high up to about mid-height of the orbit, overlapping the postorbital in a broad tongue.

The quadratojugal process is low, being 24 mm high at its base, and only expands a little on the ventral side until it is enclosed, and topped, by the lateral and medial lamina of the quadratojugal. The ventral rim sharpens posteriorly and almost reaches the lateral condyle of the quadrate (Fig. 11). The dorsal rim is flattened and merges anteriorly with the area of the preinfratemporal shelf; posteriorly, the anterior process of the quadratojugal rides on the flattened surface of the jugal.

2.5.10. Postorbital

In dorsal view, the postorbital appears stout and truncated in comparison to other phytosaur taxa (Fig. 5). This is because of the short squamosal process of the postorbital that forms the anterolateral rim of the supratemporal fenestra. The process extends over only one fourth of the length of the postorbital–squamosal bar, which is mainly formed by the elongated squamosal. The postorbital reaches forwards along the parietal and the postfrontal to form the centre of the posterior rim of the orbit. The crescentic orbital process extending downward and forward is low, but strongly expanded transversally, being twice as broad as high. It is wedged as a thin but long prong between the lacrimal and the jugal (Fig. 7), rather than extending along the infratemporal fenestra and meeting the lacrimal anteriorly and the jugal ventrally. The postorbital also contributes little to the anterior rim of the infratemporal fenestra externally, although it extends downward on the medial rim of the postorbital flange to about mid-height of the infratemporal fenestra (Fig. 7).

2.5.11. Postfrontal

The postfrontal is the smallest element exposed on the skull roof (Fig. 5). It is almost semicircular in shape. The convex edge is surrounded, from front to back, by the frontal, the parietal and the postorbital, and the concave edge forms the posterodorsal rim of the orbit. A conspicuous broad hump on the postfrontal marks the highest point of the orbital rim (Fig. 8), and thus of the skull roof.

2.5.12. Parietal

The parietals extend forward to the level of the posterior rim of the orbits, forming a short transverse interdigitating suture with the frontals (Fig. 5). Anterolaterally, the parietal meets the postfrontal in a concave suture. Laterally, the bone is in contact with the postorbital, and it forms the entire anterior rim of the strongly reduced supratemporal fenestra posteriorly. In TTU-P10074 (left side, Fig. 6), it extends slightly farther posterior along the medial rim of the postorbital–squamosal bar. In the centre of the parietals, there are two oval depressions situated symmetrically along the midline, posterior to a marked central hump on the interparietal suture. In Mystriosuchus westphali GPIT 261/001 and Smilosuchus gregorii UCMP 27200, such an elevation marks a dome-like excavation of the internal side of the parietals that is confluent with the brain cavity (Camp Reference Camp1930; Hungerbühler Reference Hungerbühler1998). This structure has been interpreted as evidence for a pineal organ (Camp Reference Camp1930; Langston Reference Langston1949) or, alternatively, as the cartilaginous tips of the supraoccipital in the otherwise ossified skull roof (Roth & Roth Reference Roth, Roth, Thomas and Olson1980). The central skull roof terminates posteriorly with the conjoined parietal extensions that form a rectangular parietal ledge overhanging the supraoccipital shelf for 25 mm (Fig. 9). The corners of the ledge are extended into two posteriorly-pointing prongs, which are dorsoventrally flattened. In the cavity below the ledge, the parietals bear two symmetrical pits close to the midline, probably the origin of strong tendons of parts of the epaxial musculature (Anderson Reference Anderson1936). The corners of the cavity below the parietal ledge are deeply sculptured with ridges, protuberances and grooves, which provide further insertion points for musculature.

The squamosal processes of the parietals form almost vertically descending walls around the supraoccipital, then curve horizontally while diverging posterolaterally, and the pointed tips finally meet and overlap the parietal processes of the squamosals. An exception is the left side of TTU-P10077, in which the squamosal process of the parietal does not reach the squamosal on the dorsal face of the opisthotic process, but terminates in a broad end sutured to the supraoccipital (Fig. 20). The squamosal processes that form the lateral walls of the supraoccipital shelf and ride on the supraoccipital are low and stockily built, with a broad base that narrows rapidly to a sharp rim. They send a thin crescentic lamina onto the supraoccipital, both laminae together covering about one quarter of the surface of the shelf. The descending flange of the parietal anterior to the squamosal process extends forwards, forming about half of the lateral surface of the braincase, and meets the laterosphenoid, epiotic, and opisthotic in a straight oblique suture (Fig. 18).

Figure 18 Machaeroprosopus lottorum TTU-P10076, left side of the braincase. For details of the otic region, see Figure 24. Scale bar=50 mm. Abbreviations: cp.ps=cultriform process of parasphenoid; ept=epipterygoid; eptp.pt=epipterygoid process of pterygoid; g=groove; hypg=hypophyseal gap; pqg=palatoquadrate groove; ptr.q=pterygoid ramus of quadrate; qr.pt=quadrate ramus of pterygoid; V=trigeminal foramen; VII=foramen for facial nerve.

Figure 19 Machaeroprosopus sp. TTU P-10074, postnarial part of the skull in dorsal view. Scale bar=10 mm. Abbreviations: aof=antorbital fenestra; aofo.j=jugular antorbital fossa; f=frontal; itf=infratemporal fenestra; j=jugal; l=lacrimal; m=maxilla; n=nasal; na=naris; o=orbit; opo.sq=opisthotic process of squamosal; p=parietal; pl=parietal ledge; po=postorbital; pof=postfrontal; prd=preorbital depression; prf=prefrontal; q=quadrate; qj=quadratojugal; soc=supraoccipital; sq=squamosal; stf=supra-temporal fenestra.

Figure 20 Machaeroprosopus lottorum TTU P-10077, left bases of parietal–squamosal bar and paroccipital process: (A) dorsolateral view; (B) section along indicated crack. Scale bar=10 mm. Abbreviations: epi=epipterygoid; opo=opisthotic; p=parietal; pro=prootic; ptf=posttemporal fenestra; soc=supraoccipital; sq=squamosal.

2.5.13. Squamosal

A major distinction between M. lottorum TTU-P10076 and TTU-P10077 on the one hand, and all other nominal species of Machaeroprosopus including Machaeroprosopus sp. TTU-P10074 on the other is the shorter length of the free postorbital–squamosal bar i.e., the distance between the tip of the squamosal and the anterior rim of the supratemporal fenestra, which corresponds largely to the maximum length of the squamosal, in proportion to the distance between the anterior rim of the supratemporal fenestra and the orbit. The relative (and absolute) maximum width of the squamosal in the anterior third to midlength of the element is also larger in M. lottorum than in TTU-P10074 and in other species of Machaeroprosopus, with the exception of M. gregorii and M. bermani. The width increase is due to the expansion of the medial lamella of the squamosal. In TTU-P10076, the posterior section of the rim of the medial lamella is squared and the anterior section is rounded (Fig. 9), in contrast to a thin and sharp rim in TTU-P10077. Both specimens show a natural depression on the central medial part of the free postorbital–squamosal bar (e.g., Fig. 6), which enhances the elevated appearance of the posterior process.

The posterior process of the squamosal projects far beyond the extremity of the paroccipital process. Although almost identical in absolute length, the length of the posterior process of the squamosal in proportion to postorbital length is moderate in the larger skull TTU-P10077 (39 mm) than in TTU-P10076 (45 mm), which falls in the same longer relative size class as TTU-P10074. The overall shape of the process is, however, similar in all specimens. It forms a massive, broad, but in particular vertically expanded structure called the terminal knob of the squamosal by Ballew (Reference Ballew, Lucas and Hunt1989). The process is considerably narrower as the parietal–squamosal bar, which leads to a sinuous (in other specimens angular) curvature of the medial rim of the postorbital–squamosal bar (Figs 5, 19; indeterminate in TTU-P10077 because of incompleteness). The medial side of the knob is flattened and confluent with the flat medial rim of the parietal–squamosal bar, the lateral side is convex and bulgy. The verticalisation of the terminal knob results in a dorsal surface sculptured with faint pits and grooves that is significantly raised above the level of the postorbital–squamosal bar. The knob forms the posterior border of a lanceolate area on the horizontal face of the squamosal that show the typical sculpture of anastomosing blunt ridges and elongated grooves in TTU-P10074 and TTU-P10076 (Fig. 5), but is almost unsculptured in TTU-P10077 (Fig. 4). Both TTU-P10076 and TTU-P10077 show large, irregularly shaped pits, suggestive of insertions of tendons, on the lateral face of the ventral base of the posterior process (Fig. 7).

The opisthotic process (Figs 7, 9; ‘opo.sq’) of the squamosal (descending process in Long & Murry 1995; hook-like process in Mehl 1928), the origin of the m. depressor mandibulae profundus (Anderson Reference Anderson1936), projects downward for about 30 mm. The vertical, slightly sinuous anterior margin forming the posterior rim of the otic notch ends in two unequally sized prongs set transversally. The ascending posterior margin shows several protuberances and encloses an angle of 40° with the anterior margin (less steep with 55° in TTU-P10074), resulting in a triangular rather than hook-shaped outline of the process. The smooth lateral surface is confluent with the area for the m. depressor mandibulae superficialis. The dorsal half of the medial face is braced against the extremity of the anterior side of the paroccipital process of the opisthotic. The posterior surface and the lateral end of the paroccipital process merge to a single strongly rugose area that faces posteriorly.

The thin parietal process extends exactly anteromedially (Fig. 9, ‘ppr.sq’). The lateral half is expanded posteriorly by a thin lamella that forms a sharp posterior ridge running parallel to and below the medial rim of the postorbital–squamosal bar. A cross-section of the process is here teardrop shaped, with an extended sharp posterior rim. The broad base of the parietal process, the ventral and the medial surface of the squamosal body enclose the dorsal sulcus (‘ds’), which is the area of the adductor chamber that is open posteriorly because of the depression of the parietal–squamosal bar. The medial section of the bar is twisted for about 90° around the long axis. The posterior ridge is gradually reduced in size leading to an oval cross-section, shifts onto the dorsal surface, and merges with the descending rim of the supraoccipital shelf. Medially, the parietal process enters the corner of the supraoccipital shelf and interdigitates with the supraoccipital, excluding this element from the posttemporal fenestra. The anteromedial extent of the parietal process is largely destroyed on the right side of TTU-P10076 and difficult to access on the left side as well as in TTU-P10074, and accessible in TTU-P10077 only (Fig. 20). Here, the squamosal sends a narrow, 2 mm, thin extension that lies on the opisthotic onto the medial side of the braincase. The extension forms a marked ridge in continuation with the anterior edge of the parietal–squamosal bar. It continues below the anterior face of the squamosal process of the parietal, lying on the descending flange of the parietal, and makes contact with the prootic. The parietal process forms the entire upper rim of the posttemporal fenestra. The ventral surface of the base of the parietal process roofs over the paroccipital process of the opisthotic, and forms with the squamosal flange the ventral sulcus. The squamosal is firmly sutured with the paroccipital process along the distinct lateral edge of the ventral sulcus (Fig. 9, ‘vs’). On the lateral side, a shallow triangular and rugose pit, probably the origin of a tendon, is separated from the ventral sulcus by a broad, ventrally narrowing ridge. Anteromedially, the squamosal develops a thin lamella that overlies the posterior face of the paroccipital process forming the bottom of the vental sulcus. The lamella extends upon the dorsal surface of the paroccipital process and extends forward covering the opisthotic/quadrate suture. Thus, the squamosal does not only form the lateral corner of the posttemporal fenestra, but also the lateral one third of the ventral rim. It continues as a flat, broad process (pterygoid process sensu Mehl Reference Mehl1916) for a short distance anteromedially on the dorsal face of the paroccipital process along the inner side of dorsal rim of the pterygoid–quadrate plate, i.e. the quadrate ramus of the pterygoid.

The quadratojugal process is a broad vertical extension that articulates with the quadrate head medially. At the base of the upper one third of the infratemporal fenestra, the quadratojugal process juts out to form a laterally facing facet for the quadratojugal, which results in a narrow horizontal platform (Fig. 7). The quadratojugal overlaps the quadratojugal process, leaving a thin tapering prong visible along three quarters of the posterior rim of the infratemporal fenestra. Internally, the process extends broadly downward and covers a large area of the quadratojugal.

The sharp lateral edge of the postorbital–squamosal bar continues as a prominent ridge beyond the infratemporal fenestra, and outlines the base of the quadratojugal process as a depressed, smooth area, bordered ventrally by the horizontal platform of the squamosal. This area includes a funnel-shaped depression on the squamosal in extension of the infratemporal fenestra, which was interpreted as the origin of the m. adductor externus superficialis in Smilosuchus gregorii UCMP 27200 by Anderson (Reference Anderson1936). In TTU-P10076, this depression extends into a very faint groove that is cut off by the sculptured dorsal part of the lateral face of the squamosal. The ridge of the postorbital–squamosal bar is reduced to broad and low area, and the dorsal and lateral surface of the squamosal grade smoothly into each other in the centre of the bone and on the posterior process. The smooth area for the m. depressor mandibulae superficialis above the opisthotic process of the squamosal is poorly defined in TTU-P10076. It terminates posteriorly in a concave vertical edge that connects the posterior process with the opisthotic process of the squamosal, here called the squamosal flange (Fig. 9, ‘fl.sq’). The flange is comparatively small and thick, but quickly thins out to a sharp edge that extends only over a short distance on the ventral side of the posterior process. Ventrally, above the opisthotic process, this edge is drawn out into a short, knobby posteroventral projection; the subsidiary opisthotic process of the squamosal (‘sopo.sq’).

2.5.14. Quadratojugal