Since the time of its drilling in 1954, the Archerbeck Borehole has been considered the most representative Carboniferous succession in southern Scotland. The earliest results were documented in internal reports of the British Geological Survey. However, more complete results were published later by Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961) and Cummings (Reference Cummings1961), with appendices by numerous collaborators. The 1·4 km-deep Archerbeck Borehole (Fig. 1) is located 3 km NE of Canonbie (Dumfriesshire) [NY 4156 7815] in southern Scotland, close to the border with northern England, and details of the drilling operation can be found in Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961). The succession lies within the Solway Basin at the western end of the Northumberland Trough in an intermediate geographical position between the Pennines (northern England) and the Midland Valley of Scotland (e.g. Dean et al. Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011; Waters et al. Reference Waters, Somerville, Jones, Cleal, Collinson, Waters, Besly, Dean, Stephenson, Davies, Freshney, Jackson, Mitchell, Powell, Barclay, Browne, Leveridge, Long and McLean2011b). Hence, the borehole sequence bridges the lithostratigraphy and faunal assemblages between both regions. As a result, a perfect lithostratigraphical correlation should have been established. However, obvious differences were recognized with the type sections in the Pennines and the Midland Valley of Scotland by Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961) (see also Holliday et al. Reference Holliday, Burgess and Frost1975; George et al. Reference George, Johnson, Mitchell, Prentice, Ramsbottom, Sevastopulo and Wilson1976). As a consequence, new local names were defined for the limestone horizons in the borehole. In the earliest work, only a correlation with the Brampton succession (Northumberland Trough) was proposed, which is representative, in part, of the Alston Block succession of northern England. However, this correlation was based mostly on the correlation of the Catsbit Limestone with the Great Limestone, although as the authors recognised, palaeontological evidences were only obtained from the upper part of the Catsbit Limestone, where the base of the Pendleian was placed by Cummings (Reference Cummings1961). Since the earliest studies, the correlation below this boundary (most of the Alston Formation) was considered to be difficult (Lumsden & Wilson Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961). The most reliable palaeontological evidence for the correlation was the foraminiferal zones identified by Cummings in Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961). However, as discussed by other authors and herein (see section 2), those zones were recognised as out of place and, thus, the correlation presented by Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961) had little support.

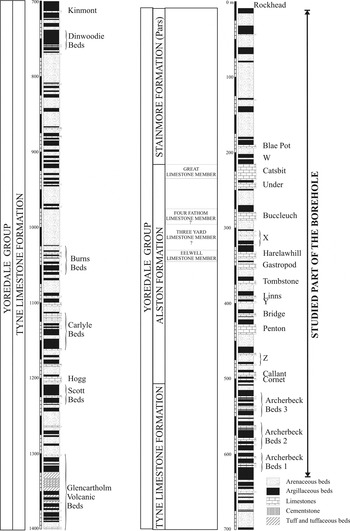

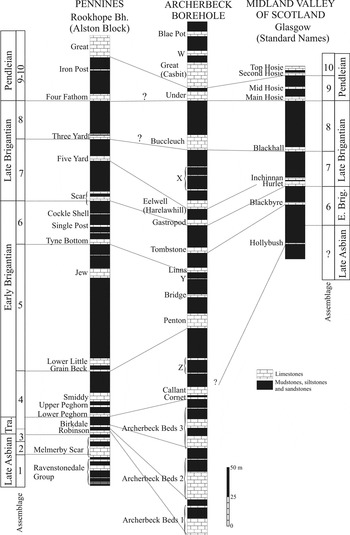

Figure 1 Lithostratigraphic log of the Archerbeck Borehole (after Lumsden & Wilson Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961). Lithostratigraphic nomenclature after Dean et al. (Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011) and Waters et al. (Reference Waters, Somerville, Jones, Cleal, Collinson, Waters, Besly, Dean, Stephenson, Davies, Freshney, Jackson, Mitchell, Powell, Barclay, Browne, Leveridge, Long and McLean2011b).

The correlation of the Alston Formation between the Solway Basin and the Pennines, comprising the Penton, Bridge, Linns, Tombstone, Gastropod, Harelawhill, unnamed Limestone X and Buccleuch limestones of the Archerbeck Borehole, were correlated with the Smiddy, Lower Little, Jew, Tyne Bottom, Scar, Five Yard, Three Yard and Four Fathom limestones of the Brampton area respectively. Most of the latter limestones have been recently elevated to member status by Dean et al. (Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011), of which the Four Fathom Limestone and the Great Limestone members were formally recognised in the Archerbeck succession to replace the Buccleuch and Catsbit limestones respectively (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the Eelwell Limestone Member (recorded in the Northumberland Trough, and laterally equivalent to the Five Yard Limestone Member in the Pennines) was proposed to replace the Harelawhill Limestone. Dean et al. (Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011) also documented the occurrence of the Three Yard Limestone Member in the Northumberland Trough between the Four Fathom Limestone and Eelwell Limestone members, although it was not extended across to the Solway Basin. This position would correspond to the unnamed Limestone X in the Archerbeck Borehole (Fig. 1). The same correlation is observed in Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961) and Dean et al. (Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011) and Waters et al. (Reference Waters, Somerville, Jones, Cleal, Collinson, Waters, Besly, Dean, Stephenson, Davies, Freshney, Jackson, Mitchell, Powell, Barclay, Browne, Leveridge, Long and McLean2011b), although no supporting palaeontological evidence was presented.

The Archerbeck Borehole drilling terminated at 4604′ (c. 1403 m), in the Glencartholm Volcanic Beds (Fig. 1), of an inferred Arundian age (early Viséan), owing to the occurrence of the foraminiferal genera Archaediscus and Glomodiscus (Cummings Reference Cummings1961). The age of the clastic rocks immediately below the rock-head at 37′ 8″ (11·5 m) was indeterminable, but in the interval below, down to 752′ (229 m), lower Namurian rocks (E1, Pendleian) were determined (including the Blae Pot Limestone and the upper part of the Catsbit Limestone). Thus, a continuous succession spanning much of the upper Viséan to the lower Serpukhovian (Asbian to Pendleian regional substages) was studied in detail (see sampling intervals and fossiliferous horizons in Lumsden & Wilson Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961; and in Cummings Reference Cummings1961). For this present study, limestones and calcareous argillites in the upper half of the borehole have been re-examined, from 2053′ upward (626 m depth in the borehole), starting just below the Archerbeck Beds (the base of the Archerbeck Beds was located at 2038′ 9″ (621 m) (Fig. 1). A total of approximately 550 large thin-sections were examined (housed in the British Geological Survey, Edinburgh), belonging to 475 calcareous horizons.

The biostratigraphy for those rocks and correlation with other successions in northern England and Scotland has been widely discussed, and several proposals have been published previously (e.g. Lumsden & Wilson Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961; Holliday et al. Reference Holliday, Burgess and Frost1975; George et al. Reference George, Johnson, Mitchell, Prentice, Ramsbottom, Sevastopulo and Wilson1976; Ramsbottom et al. Reference Ramsbottom, Calver, Eagar, Hodson, Holliday, Stubblefield and Wilson1978; Strank Reference Strank1981). As mentioned above, in a recent revision of the lithostratigraphy and correlation of the Carboniferous rocks in Great Britain (e.g. Dean et al. Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011; Waters et al. Reference Waters, Somerville, Jones, Cleal, Collinson, Waters, Besly, Dean, Stephenson, Davies, Freshney, Jackson, Mitchell, Powell, Barclay, Browne, Leveridge, Long and McLean2011b), some changes have been introduced in the formal lithostratigraphy of the borehole, as well as in the biostratigraphic dating. The lower part of the succession in the Archerbeck Borehole from the Glencartholm Volcanic Beds (now Member) at the base up to the base of the Callant Limestone (base of the Brigantian) was included in the Tyne Limestone Formation (Fig. 1). From the Callant Limestone up to the top of the Catsbit Limestone at 225 m (the base of the Catsbit Limestone was considered as the base of the Pendleian) was assigned to the Alston Formation, and the upper part of the borehole succession has been included in the Stainmore Formation (Dean et al. Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011; Fig. 1). All three formations belong to the Yoredale Group. The Namurian (Pendleian) upper part of the Archerbeck Borehole was compared to the Brampton area (Ramsbottom et al. Reference Ramsbottom, Calver, Eagar, Hodson, Holliday, Stubblefield and Wilson1978, fig. 10) and the Catsbit Limestone correlated with the Great Limestone and the Blae Pot Limestone with the Little Limestone. However, in both cases, no new palaeontological data was provided in support of these correlations.

As the age dating of the base of the borehole has not been revised in this present study, it is necessary to highlight that Dean et al. (Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011) considered the base of the Tyne Limestone Formation as Holkerian (mid Viséan) on the basis of brachiopods, whereas Waters et al. (Reference Waters, Dean, Jones, Somerville, Waters, Somerville, Jones, Cleal, Collinson, Waters, Besly, Dean, Stephenson, Davies, Freshney, Jackson, Mitchell, Powell, Barclay, Browne, Leveridge, Long and McLean2011a) considered the entire formation as Asbian (lower late Viséan), based on miospores (Fig. 2). Originally, Cummings (in Lumsden & Wilson Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961) assigned the base of the borehole as lowermost Viséan (Arundian).

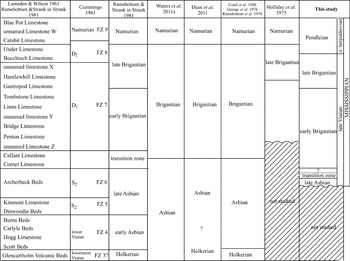

Figure 2 Ages and biozones attributed previously to the succession of the Archerbeck Borehole.

The aims of this study on the Archerbeck Borehole succession are to: (i) revise the biostratigraphy for the interval between the Archerbeck Beds and the Blae Pot Limestone (upper part of the Tyne Limestone Fm up to the lower part of the Stainmore Fm); (ii) clarify the position of the Asbian/Brigantian and Viséan/Serpukhovian boundaries; (iii) update the foraminiferal and algal taxonomic nomenclature published by previous authors; (iv) propose new foraminiferal assemblages; and (v) revise the correlation with the type sections in the Pennines and Midland Valley of Scotland areas, as well as elsewhere in Europe and N Africa.

1. Previous microfossil studies

Two aspects can be highlighted: the foraminiferal studies in the Archerbeck Borehole, and their implication for regional correlations. Within the foraminiferal studies carried out on the rock core, it is necessary to make some introductory remarks on the papers by Cummings (Reference Cummings1961), Cummings in Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961), Conil et al. (Reference Conil, Longerstaey and Ramsbottom1980) and Strank (Reference Strank1981).

Cummings' work on the microfossils established the first biostratigraphic study of the calcareous horizons in the borehole, in parallel with the lithological analysis undertaken by Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961). He recognised seven foraminiferal zones, from base to top (FZ?3 to FZ9), of his unpublished foraminiferal zonal scheme (Fig. 2). Those foraminiferal zones have been subsequently rarely used, and are commonly criticised due to the lack of a formal publication explaining their definition, and for not identifying the key foraminiferans used to define the zones. Furthermore, their correlation with the coral-brachiopod zones of Vaughan (Reference Vaughan1905) was questioned (Ramsbottom & Strank in Strank Reference Strank1981; Fig. 2) and the biostratigraphy of the assemblages were re-assigned to younger zones. In fact, some of the taxa used for the zonations are not foraminiferans, and are currently included within the aoujgaliids (a problematic group assigned to the Algospongia, Fig. 3; see details in Vachard & Cózar Reference Vachard and Cózar2010).

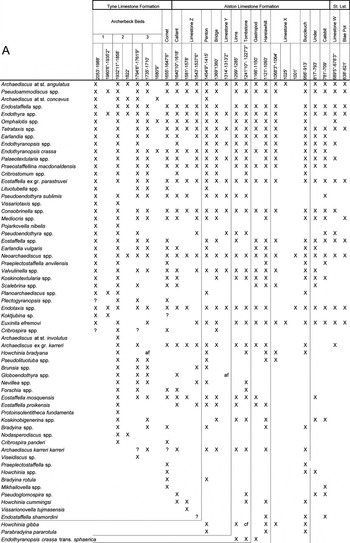

Figure 3 Algae (red and green) and Algospongia stratigraphic distribution in the Archerbeck Borehole (the acmes are highlighted in grey areas).

A thorough analysis of the documented database was undertaken because the systematics of the foraminiferans and calcareous algae has changed notably since the earliest publications in Cummings (Reference Cummings1961) and Cummings in Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961). Unfortunately, because Cummings did not illustrate any of the specimens from the borehole, it is difficult to suggest unquestionable synonymies of the microfaunal/floral elements. Any attempt at reidentification of the listed taxa has to be considered as tentative, and is based on similar morphology of the species and genera, as well as on the current knowledge of those foraminiferans in each revised bed. This attempt has been undertaken mostly for the genera, because it is virtually impossible to categorize the species. Consequently, when the genus has been recognised by the present authors in the same levels as that claimed in the published works, in general, species names have been respected (). The limited papers published on foraminiferans during the 1940s and 1950s (mostly Russian contributions) make it impossible to know exactly which taxa are included in the names used by Cummings in 1961, and the reliability of most of the data documented there is questioned. For instance, the Lasiodiscidae is one of the most confusing groups, of which Monotaxinoides, Monotaxis, Turrispira, Vissariotaxis (recorded almost in every limestone bed in the borehole), and Howchinia (common) were listed by Cummings in Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961) (). However, Vissariotaxis s.s. is extremely rare, with only three specimens recorded by the present authors in the Archerbeck Beds (Fig. 4A; see also ). Moreover, on examining Cummings' records of Howchinia, only H. bradyana coincides with our record of Vissariotaxis (Fig. 4A; ), and it cannot be confidently affirmed whether the taxa described originally were Vissariotaxis gibba, V. subconica, Howchinia sp. nov., or perhaps some other Lasiodiscidae.

Figure 4

Foraminiferal stratigraphic distribution in the Archerbeck Borehole: (A) taxa first occurring in the late Asbian and early Brigantian; (B) taxa first occurring from the late Brigantian and Serpukhovian.

A similar case can be mentioned involving the species of Bradyina: B. aff. cribrostomata, B. nautiliformis, B. rotula and B. spp. distinguished by Cummings (Reference Cummings1961). The first concern is related to the records of species left in open nomenclature by Cummings, in almost every bed from the top of the Archerbeck Beds, as well as B. rotula or B. cf. rotula from the Penton Limestone upward (). Bradyina is a historically well-known genus that is difficult to confuse with other Mississippian genera, because of its distinctive alveolar wall structure. However, we only recorded it in some sparse levels (Fig. 4A; see details in ). In addition, there is nothing to compare with the alleged species B. cribrostomata and B. nautiliformis. Specimens of B. rotula (3 thin-sections from separate horizons) and oblique sections of Bradyina have been only rarely recognised by the present authors (one record in the Archerbeck Beds, one in the Buccleuch Limestone and six in Harelawhill Limestone).

Brunsia is only recorded by the present authors up to the Penton Limestone (Fig. 4A), although it was commonly documented by Cummings (Reference Cummings1961) up to the Blae Pot Limestone, and with diverse species (). Climacammina spp. was also recorded by Cummings (Reference Cummings1961) from the base of the borehole, whereas our revised data suggests the genus first occurs in the Harelawhill Limestone (=Eelwell Limestone Member in Dean et al. Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011) (Fig. 4B). In that case, and also discussed by Ramsbottom & Strank in Strank (Reference Strank1981), in which Cummings (Reference Cummings1956) established clearly the differences between Climacammina and other Palaeotextulariidae, such as Cribrostomum, Koskinotextularia and Koskinobigenerina, but most of his records of Climacammina have to be re-assigned to the latter genera. Climacammina is unknown below the late Brigantian in the Pennines and surrounding areas (Cózar & Somerville Reference Cózar and Somerville2004; Somerville & Cózar Reference Somerville and Cózar2005; Cózar et al. Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2010).

Also, from the base of the Archerbeck Beds, according to data in Cummings (Reference Cummings1961), it is possible to identify Globivalvulina sp., and Globivalvulina spp. from beds between the Harelawhill Limestone and Buccleuch Limestone (i.e. between the Eelwell and Four Fathom Limestone members in Dean et al. Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011; Fig. 1). The latter member coincides with our record of Biseriella ex gr. parva (Fig. 4B), but the previous documentation of the genus might be attributed to oblique sections of Endotaxis (). Similarly, Biseriella is virtually unknown below the late Brigantian in northern England and Scotland (Cózar & Somerville Reference Cózar and Somerville2004, Reference Cózar and Somerville2012; Cózar et al. Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2010).

Those above-mentioned taxa share, in part, the same problem that exists for many other foraminiferans listed by Cummings (Reference Cummings1961); namely, that they are ‘out of time’ (stratigraphically incongruous). Furthermore, he records typical Pennsylvanian taxa in the Mississippian Archerbeck Borehole, such as Brunsiella, Deckerellina, Deckerella, Palaeobigenerina, Pseudobradyina and Glyphostomella, which clearly are misidentified.

Nevertheless, Conil et al. (Reference Conil, Longerstaey and Ramsbottom1980) and Strank (Reference Strank1981) illustrated numerous specimens from the same thin sections examined by the present authors from the Archerbeck Borehole. Hence, synonymies can be proposed with updated genera and species, although only a few changes are proposed herein (). However, the main problem related to these two previous studies is the absence of diagnostic taxa for biostratigraphic purposes. This is particularly the case in Strank (Reference Strank1981), where correlations of the Cummings' and Vaughan's biozones were revised and updated. Within the taxa recorded by the present authors can be highlighted the lack of reference to, or illustration of, Archaediscus at tenuis stage (or transitional forms), Euxinita, Biseriella, Climacammina, Planospirodiscus and Tubispirodiscus. These taxa are typical of the late Brigantian elsewhere (Cózar & Somerville Reference Cózar and Somerville2004; Cózar et al. Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2008a, Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2010). The absence of some other key taxa is readily explained, because Conil et al. (Reference Conil, Longerstaey and Ramsbottom1980) and Strank (Reference Strank1981) did not study the Serpukhovian levels in detail (e.g. Catsbit Limestone=Great Limestone Member and Blae Pot Limestone). According to our analysis of the borehole data documented in Cummings (Reference Cummings1961), some significant taxa typical of the Serpukhovian (Cózar et al. Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2008a, Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2010, Reference Cózar, Said, Somerville, Vachard, Medina-Varea, Rodríguez and Berkhli2011) are missing: e.g. Eosigmoilina, Monotaxinoides, Endothyranopsis plana, Eostaffella pseudostruvei, E. angusta, E. postproikensis, E. acutiformis, Loeblichia and Trepeilopsis.

The biostratigraphy of the Mississippian succession has also changed notably since Cummings' study in Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961) (Fig. 2), who assigned: (i) the Archerbeck Beds to the FZ6 (=upper S2), which corresponds to the upper Holkerian; (ii) from the unnamed limestone Z below the Penton Limestone to below the Buccleuch Limestone to the FZ7 (=D1=late Asbian); (iii) Buccleuch Limestone to the lower half of the Catsbit Limestone to the FZ8 (=D2=Brigantian); and finally (iv), the upper half of the Catsbit Limestone and Blae Pot Limestone to the FZ9 (=E1=Pendleian (lower Namurian)). Ramsbottom & Strank in Strank (Reference Strank1981) reassigned the age of almost all these limestones (Fig. 2): the Archerbeck Beds as late Asbian, the Cornet and Callant limestones as a transitional Asbian–Brigantian interval, the unnamed Limestone Z (below the Penton Limestone) as the base of the Brigantian, the Gastropod Limestone as the base of the late Brigantian, and the base of the Catsbit Limestone as the base of the Namurian. Previously, Ramsbottom et al. (Reference Ramsbottom, Calver, Eagar, Hodson, Holliday, Stubblefield and Wilson1978) had already considered the base of the Catsbit Limestone to coincide with the base of the Pendleian, and the Blae Pot Limestone was correlated with the Little Limestone in northern England, as suggested earlier by Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961). However, George et al. (Reference George, Johnson, Mitchell, Prentice, Ramsbottom, Sevastopulo and Wilson1976) and Conil et al. (Reference Conil, Longerstaey and Ramsbottom1980), in their correlation of the Archerbeck Borehole with the Pennines, considered the base of the Callant Limestone as the base of the Brigantian, and was followed recently in Waters et al. (Reference Waters, Dean, Jones, Somerville, Waters, Somerville, Jones, Cleal, Collinson, Waters, Besly, Dean, Stephenson, Davies, Freshney, Jackson, Mitchell, Powell, Barclay, Browne, Leveridge, Long and McLean2011a) and Dean et al. (Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011). On the other hand, Holliday et al. (Reference Holliday, Burgess and Frost1975) correlated the Scar Limestone (base of the late Brigantian in the Alston Block) with the Harelawhill Limestone and, although they did not study below the Penton Limestone, this was correlated to the Jew Limestone Member, in a relatively higher position in the early Brigantian of the Alston Block (only the Tyne Bottom Limestone Member is situated above; Johnson & Nudds Reference Johnson and Nudds1996). However, for Dean et al. (Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011), the Eelwell Limestone Member is considered as a lateral equivalent of the Five Yard Limestone Member in the Alston Block.

2. Foraminiferal, algal and Algospongia assemblages

In this section, detailed records of the foraminiferans, algae and Algospongia (mostly belonging to the suborders Moravamminina, Donezellina, Aoujgaliina and Calcifoliina – see Vachard & Cózar Reference Vachard and Cózar2010, tables 3, 4) are described, (documented in ), as well as their relative abundance, although in most cases, the biostratigraphically unimportant species have been grouped in open nomenclature. The assemblages described herein are a result of palaeobiological and palaeoecological changes. In some cases, these assemblages can coincide with important biostratigraphical changes (see section 3), but in other cases they only correspond to local environmental changes and several assemblages can be grouped as representative of a biozone. A summary of the database, following approximately the same stratigraphic intervals of those in Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961) is documented in Figure 3 (algae and Algospongia) and Figure 4 (foraminiferans). Illustrations of the most significant foraminiferans are displayed in Figures 5 to 11.

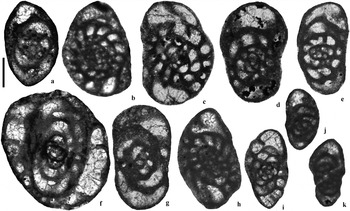

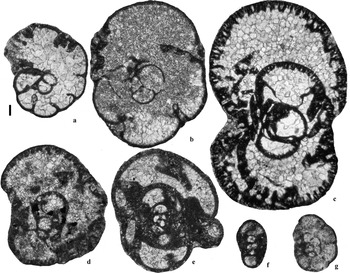

Figure 5 Selected Archaediscus of the group A. karreri (Scale bar=100 μm): (a) Archaediscus karreri grandis, 1794′, Archerbeck Beds; (b) Archaediscus karreri karreri 1724′, Archerbeck Beds; (c) Archaediscus karreri karreri 1637′, Callant Limestone; (d) Archaediscus ex gr. karreri, 1921′ 2″, Archerbeck Beds.

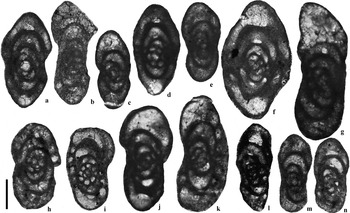

Figure 6 Selected Lasiodiscidae from the Archerbeck Borehole (Scale bar=100 μm): (a) Howchinia bradyana, 1228′, Tombstone Limestone; (b) Howchinia sp. A, 1116′, Eelwell Limestone Member (=Harelawhill Limestone); (c) Howchinia gibba, 1113′, Eelwell Limestone Member (=Harelawhill Limestone); (d) Howchinia sp. B, 930′, Buccleuch Limestone; (e) Monotaxinoides? sp., 747′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (f) Eolasiodiscus sp., 710′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (g) Howchinia cummingsi, 1236′, Tombstone Limestone.

Figure 7 Selected Euxinita and similar forms (Scale bar=100 μm): (a) Euxinita efremovi, 1901′ 11″, Archerbeck Beds; (b) Euxinita pendleiensis, 781′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (c) Euxinita pendleiensis, 626′ 9″, Blae Pot Limestone; (d) Praeostaffellina macdonaldensis, 1165′, Gastropod Limestone; (e) Praeostaffellina macdonaldensis, 1622′, Callant Limestone; (f) Vissarionovella tujmasensis, 1581′, unnamed Limestone Z; (g) Praeostaffellina macdonaldensis, 1166′, Gastropod Limestone; (h) Praeplectostaffella sp., 1653′, Cornet Limestone; (i) Praeplectostaffella sp., 948′, Buccleuch Limestone; (j) Praeplectostaffella anvilensis, 1110′, Eelwell Limestone Member (=Harelawhill Limestone); (k) Praeplectostaffella anvilensis, 951′, Buccleuch Limestone.

Figure 8 Selected Bradyinidae and Endothyranopsidae from the Archerbeck Borehole (Scale bar=100 μm): (a) Cribrospira panderi, 1861′, Archerbeck Beds; (b) Parajanischewskina brigantiensis, 951′, Buccleuch Limestone; (c) Parabradyina pararotula, 1418′, Penton Limestone; (d) Bradyina rotula, 1651′, Cornet Limestone; (e) Endothyranopsis sphaerica, 1161′, Gastropod Limestone; (f, g) Endothyranopsis plana, 751′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone).

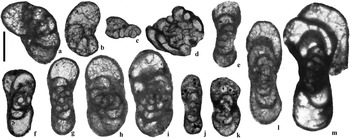

Figure 9 Selected Eostaffellidae from the Archerbeck Borehole (Scale bar=100 μm): (a) Eostaffella sp., 948′, Buccleuch Limestone; (b) Eostaffella sp., 944′, Buccleuch Limestone; (c) Eostaffella aff. acutiformis, 768′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (d) Eostaffella postproikensis, 747′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (e) Eostaffella acutiformis, 801′, Under Limestone; (f) Eostaffella proikensis, 1637′, Callant Limestone; (g) Eostaffella ex gr. pseudostruvei, 948′, Buccleuch Limestone; (h) Eostaffella pseudostruvei, 932′, Buccleuch Limestone; (i) Eostaffella pseudostruvei, 916′, Buccleuch Limestone; (j) Eostaffella pseudostruvei, 758′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (k) Eostaffella ex gr. pseudostruvei, 731′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (l) Eostaffella mutabilis, 934′, Buccleuch Limestone; (m) Eostaffella angusta, 809′, Under Limestone; (n) Eostaffella angusta, 748′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone).

Figure 10 Selected Biseriamminidae, Calcivertellidae and Endostaffellidae from the Archerbeck Borehole (Scale bar=100 μm): (a) Biseriella ex gr. parva, 1116′, Eelwell Limestone Member (=Harelawhill Limestone); (b) Biseriella ex gr. parva, 726′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (c) Calcitornella sp., 800′, Under Limestone; (d) Calcivertella sp., 803′, Under Limestone; (e) Endostaffella? sp., 809′, Under Limestone; (f) Endostaffella? sp. (=Cózar et al. 2010, fig. 4o), 1541′, unnamed Limestone Z; (g) Endostaffella shamordini, 774′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (h) Endostaffella sp., 947′, Buccleuch Limestone; (i) Endostaffella? sp., 748′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (j) “Millerella” aff. tortula, 713′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (k) “Millerella” aff. tortula, 934′, Buccleuch Limestone; (l) “Millerella” designata, 742′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (m) Planoendothyra? sp. (=Cózar et al. 2010, fig. 5k), 771′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone).

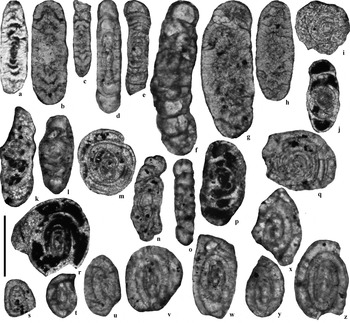

Figure 11 Selected Archaediscidae from the Archerbeck Borehole (Scale bar=100 μm): (a) Planospirodiscus sp., 1162′, Gastropod Limestone; (b) Planospirodiscus cf. taimyricus, 1001′, unnamed Limestone X; (c) Planospirodiscus taimyricus, 709′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (d) Tubispirodiscus aff. simplissimus, 714′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (e) Tubispirodiscus simplissimus, 714′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (f) Tubispirodiscus attenuatus, 1105′, Eelwell Limestone Member (=Harelawhill Limestone); (g, h) Neoarchaediscus postrugosus, 1001′, unnamed Limestone X; (i, j, k) Archaediscus spp., at angulatus stage transitional to tenuis stage, 1025′, unnamed Limestone X; (l) Archaediscus sp., 781′ Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (m) Archaediscus at tenuis stage (?), 1025′, unnamed Limestone X; (n) Archaediscus at tenuis stage, 714′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (o) Tubispirodiscus sp., at tenuis stage, transitional form to Brownediscus, 628′, Blae Pot Limestone; (p) Archaediscus at tenuis stage, 817′, Under Limestone; (q) Archaediscidae new genus cf. Cózar et al. (Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2010, fig. 7w), 714′, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (r) Quasiarchaediscus? aff. pamiriensis, 1025′, unnamed Limestone X; (s, t, u, v) Eosigmoilina sp. 1, 722′, 720′, 718′ and 719′ respectively, Great Limestone Member (=Catsbit Limestone); (w, x, y, z) Eosigmoilina robertsoni, 623′ 5″, 626′ 9″, 622′ 7″ and 622′ 7″ respectively, Blae Pot Limestone.

The Archerbeck Beds, a c. 338′ (103 m)-thick interval in the upper part of the Tyne Limestone Formation (between 622 m and 519 m depth), comprises alternating limestones, sandstones and shales. In terms of the foraminiferal assemblages, three intervals can be recognised. The first interval (Archerbeck Beds 1) is observed from the base of the studied part of the borehole, 2053′ (626 m) up to 1935′ 2″ (590 m); the second interval (Archerbeck Beds 2) between 1935′ 2″ (590 m) up to 1822′ (555·5 m); and finally, the third interval (Archerbeck Beds 3) from 1794′ 6″ (547 m) up to 1680′ 9″ (512 m) (Fig. 4A; ).

The Archerbeck Beds 1 interval is dominated by the foraminiferans Archaediscus at angulatus and concavus stages, Pseudoammodiscus, Endostaffella, Omphalotis, Tetrataxis, Endothyra, Endothyranopsis crassa, Praeostaffellina, Cribrostomum and Pseudoendothyra sublimis. Palaeotextularia, Consobrinella, Eostaffella parastruvei, Mediocris and Valvulinella are also relatively common. It is noteworthy, for the rare occurrence of Neoarchaediscus, Euxinita efremovi (Fig. 7a), Cribrospira?, Vissariotaxis, Pojarkovella nibelis, Praeplectostaffella (Fig. 7h–k) and Koktjubina (Fig. 4A). The more common Algospongia are Aoujgalia variabilis, A. skimoensis, Roquesselsia, Ungdarella, Kamaena and Palaeoberesella, and rare Claracrusta and Fourstonella densifolia. Related to the true green algae, the rare occurrences of Pseudokulikia and Windsoporella can be highlighted (Fig. 3).

Foraminiferans of the Archerbeck Beds 2 interval are similar to the previous one, but some taxa become relatively abundant, such as Neoarchaediscus, Praeplectostaffella, Euxinita efremovi and Archaediscus ex gr. karreri (Fig. 5a, d). The latter group also first occurs in these beds, together with Protoinsolentitheca, Howchinia bradyana (Fig. 6a), Nevillea, Forschia, Eostaffella mosquensis, Eostaffella proikensis (Fig. 9f), Bradyina and Nodasperodiscus (Fig. 4A). The main difference in these assemblages as compared with the Archerbeck Beds 1 interval is observed in the algae where, in addition to the Algospongia Aoujgalia, Kamaena, Roquesselsia and Ungdarella, the green algae Coelosporella, Koninckopora and Nanopora also become common, mostly in the upper part of this interval (Fig. 3; ). The Archerbeck Beds 2 interval also contains Saccamminopsis, the alga Kulikia, and the Algospongia Stacheia, Stacheoides, Exvotarisella, Fourstonella variabilis, F. johnsoni, Fasciella kizilia, Fascifolium, Kamaenella and Pseudostacheoides.

New occurrences in the Archerbeck Beds 3 interval are scarce, and can be highlighted by the foraminifer Archaediscus karreri karreri (Fig. 4A, 5c). However, this interval is characterised by a general decrease in diversity and abundance of the taxa, mostly related to the algae/aoujgaliids.

The next interval is assigned to the Cornet Limestone, where the assemblages are dominated by the foraminiferans Archaediscus at angulatus stage, Pseudoammodiscus and Endostaffella. Also relatively common are Endothyra, Omphalotis, Tetrataxis, Endothyranopsis crassa, Palaeotextularia, Neoarchaediscus, Endotaxis, Cribrospira (Fig. 8a), Archaediscus ex gr. karreri, Archaediscus k. karreri and Bradyina rotula (Fig. 8d). Also notable are the rare occurrences of Praeostaffellina (Fig. 7d, e), Howchinia and the first Mikhailovella, as well as the last occurrences of Plectogyranopsis and Koktjubina (Fig. 4A). Although these foraminiferal assemblages suggest a change compared to those of the Archerbeck Beds, the most dramatic change is observed in the algae and Algospongia, which virtually disappear (Fig. 3; ), and the possible first occurrence of the green alga Paraepimastopora? (poorly preserved).

A new foraminiferal assemblage can be recognised at the base of the Alston Limestone Formation, which occurs in the Callant Limestone, the unnamed Limestone Z of Strank (Reference Strank1981), Penton Limestone, Bridge Limestone and the unnamed Limestone Y of Strank (Reference Strank1981). This assemblage contains common foraminiferans, such as Archaediscus at angulatus stage, Endostaffella, Endothyra, Endothyranopsis crassa, Eostaffella parastruvei, Praeostaffellina, and relatively common Omphalotis, Tetrataxis, Neoarchaediscus, Archaediscus ex gr. karreri, A. k. karreri, and Eostaffella proikensis. Some other foraminiferans last occur in this interval, such as Archaediscus at concavus stage, Cribrospira, Brunsia and Lituotubella. Other taxa, such as Howchinia cummingsi (Fig. 6g) first occur in the Callant Limestone, H. gibba (Fig. 6c) in the Penton Limestone, and Parabradyina at the top of the Penton Limestone (Fig. 4A). The diversity of the algae and Algospongia increases significantly, but also progressively, and is noticeable as local peaks of the Algospongia Kamaena and Luteotubulus in the Penton Limestone, relatively common Palaeoberesella throughout the interval and Falsocalcifolium punctatum at the top of the Penton Limestone. The red alga Neoprincipia first occurs in the unnamed Limestone Z, and the Algospongia Fasciella crustosa at the top of the Callant Limestone (Fig. 3).

The fossil content of the unnamed Limestone Y is scarce, and it cannot be characterised precisely. The Linns and Tombstone limestones can be distinguished from the older assemblages by the more common foraminiferans Neoarchaediscus, Valvulinella, Archaediscus ex gr. karreri, as well as by common peaks of the Algospongia Falsocalcifolium and Kamaena. The Linns and Tombstone limestones are noteworthy for the first occurrence of transitional forms of the foraminifer Endothyranopsis crassa to E. sphaerica (Fig. 4A).

The Gastropod Limestone also shows a change in the assemblages. This is characterised by a general decrease in the diversity and abundance of foraminiferans, algae and Algospongia. Taxa which decrease more significantly are the foraminiferans Endostaffella, Endothyranopsis, Eostaffella, Pseudoendothyra, Valvulinella and Archaediscus ex gr. karreri, as well as the previously abundant Algospongia Kamaena and Falsocalcifolium. In general, the Gastropod Limestone is one of the most impoverished horizons, with regard to Algospongia and algae (except for the Catsbit and Blae Pot limestones). The first occurrences of significant foraminiferans can be highlighted: Endothyranopsis sphaerica (Fig. 8e), Planospirodiscus (Fig. 11a), Asteroarchaediscus and the first transitional forms to Archaediscus at tenuis stage (Fig. 11i–k) (Fig. 4B).

The assemblages of the Harelawhill Limestone, unnamed Limestone X (which comprises three separate beds) and the Buccleuch Limestone are relatively uniform. This interval can be characterised by a recovery in the diversity and abundance of many taxa. The only significant decrease is observed in the abundance of the foraminiferans Archaediscus at angulatus stage and Praeostaffellina. Other foraminiferans which show a higher recovery in numbers are Endostaffella, Neoarchaediscus, Eostaffella, Howchinia (in particular H. gibba), Parabradyina and Planospirodiscus, which become relatively common. The Harelawhill Limestone and the unnamed Limestone X also contain the highest abundance of the Algospongia Falsocalcifolium punctatum, which is replaced by common Calcifolium okense in the Buccleuch Limestone (Fig. 3). The most significant first occurrences in the Harelawhill Limestone are the foraminiferans Climacammina, Tubispirodiscus attenuatus (Fig. 11f), Chomatomediocris and Biseriella (Fig. 10a, b) (Fig. 4B). However, the increase in new appearances of foraminiferans is more important in the unnamed Limestone X, from which is recorded the first Asteroarchaediscus baschkiricus, A. rugosus, Neoarchaediscus postrugosus (Fig. 11g, h), Planospirodiscus cf. taimyricus (Fig. 11b), Tubispirodiscus cf. cornuspiroides, Quasiarchaediscus? aff. pamiriensis (Fig. 11r), and (?)Archaediscus at tenuis stage (which consistently occurs from the Under Limestone (Fig. 11m, n, p)). First appearances in the Buccleuch Limestone include the foraminiferans Parajanischewskina brigantiensis (Fig. 8b), (?) Euxinita pendleiensis (which consistently occurs from the Catsbit Limestone (Fig. 7b, c)), “Millerella” aff. tortula (Fig. 10j, k), Eostaffella ex gr. pseudostruvei (Fig. 9g, k) and, in the upper part, Eostaffella pseudostruvei s.s. (Fig. 9h–j) (Fig. 4B).

The next assemblage is recognised through the interval of the Under Limestone and the lower part of the Catsbit Limestone (below c. 770′–234 m depth in the borehole). This foraminiferal assemblage is characterised by the recovery of Archaediscus at angulatus stage, Endostaffella, Endothyra, Eostaffella, Endotaxis, the richest abundance of Neoarchaediscus, and common Eostaffella ex gr. parastruvei, Planospirodiscus, Climacammina, Biseriella and Asteroarchaediscus. This interval is also characterised by a higher diversification in species of Tubispirodiscus (T. hosiensis, T. simplissimus), calcivertellids (Fig. 10c–d) (e.g. Calcivertella and Calcitornella), Endothyranopsis plana (Fig. 8f, g), Eostaffella acutiformis (Fig. 9e), E. angusta (Fig. 9m, n), and Archaediscus at tenuis stage.

The middle part of the Catsbit Limestone (770′ to 746′/234 to 227 m) is different, and it highlights a marked impoverishment of the assemblages. The only new significant foraminiferal first occurrences are Monotaxinoides? (Fig. 6e), Eostaffella postproikensis (Fig. 9d) and large specimens of Asteroarchaediscus baschkiricus.

The youngest assemblages are observed in the upper part of the Catsbit Limestone, the unnamed Limestone W and the Blae Pot Limestone. These foraminiferal assemblages are similar to those in the Under Limestone and lower part of the Catsbit Limestone. In fact, all of this thick interval might be united in a single assemblage, although the marked impoverishment of the middle part of the Catsbit Limestone is in marked contrast with the assemblages above and below. The differences recognised in the upper part of the Catsbit Limestone and Blae Pot Limestone assemblage are limited to an enrichment in the foraminifers Euxinita, Planospirodiscus and Asteroarchaediscus, and the presence of Trepeilopsis, “Millerella” aff. tortula, “Millerella” designata (Fig. 10l), Pseudocornuspira and Eosigmoilina sp. 1. (Fig. 11s–v) Eosigmoilina robertsoni (Fig. 11w–z) and transitional forms to Brownediscus (Fig. 11o) first occur in the Blae Pot Limestone (Fig. 4B).

3. Biostratigraphy of Archerbeck Borehole

It is difficult to define the base of the Brigantian in the Archerbeck Borehole due to the paucity of diagnostic fossil markers, micro- and macrofossils (e.g. see Cózar & Somerville Reference Cózar and Somerville2004, Reference Cózar and Somerville2005a, Reference Cózar and Somerville2006). As described previously, the base of the Brigantian was located in the interval from the base of the Cornet Limestone to the unnamed Limestone Z (Fig. 2). Ramsbottom & Strank in Strank (Reference Strank1981) considered the Cornet and Callant limestone interval as transitional between the late Asbian and early Brigantian. In the Archerbeck Borehole, there are no substantial differences between the foraminiferal assemblages, which are rather uniform from the Callant to the Bridge limestones. In contrast, the Cornet Limestone shows the most dramatic turnover when analysing the algal and Algospongia assemblages. This event might help constrain the base of the Brigantian, as it cannot be positioned at the base of the unnamed Limestone Z, as no foraminiferal faunal changes are observed.

Analysing the first appearance datum (FAD) of the most significant taxa, several aspects can be highlighted. Archaediscus ex gr. karreri (e.g. A. karreri grandis) and Howchinia bradyana occur in the Archerbeck Beds (1931′=589 m, base of the Archerbeck Beds 2 interval), and Bradyina sp. in slightly younger beds (1871′=570 m) within the same interval. Those taxa are typically recorded from the uppermost late Asbian in the UK and Ireland (Conil et al. Reference Conil, Longerstaey and Ramsbottom1980, Reference Conil, Groessens, Laloux, Poty and Tourneur1991; Jones & Somerville Reference Jones, Somerville, Strogen, Somerville and Jones1996). In regards to the biostratigraphical assemblages (combining foraminifers and calcareous algae) defined in the Pennines, they correspond to Assemblage 4 of Cózar & Somerville (Reference Cózar and Somerville2004) (Fig. 12).

Figure 12 Correlation of the Archerbeck Borehole with the Pennines (northern England) and Midland Valley of Scotland. Abbreviations: Brig.=Brigantian; E=early; Tra=Transitional beds. X–Z are unnamed limestones. (Modified from Cózar et al. Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2010).

The FAD of Archaediscus karreri karreri is questionably located at 1794′ (547 m), almost at the base of the Archerbeck Beds 3 interval, but an undoubted record of this subspecies is at 1725′ (c. 526 m). In terms of the Algospongia and algae, in the upper part of the Archerbeck Beds 2 interval is observed the acme of Kamaena, Ungdarella uralica, Coelosporella jonesii, Koninckopora and Nanopora. Those associations, also with common green algae, can be compared with the Algal Assemblages C–D in Ireland (Cózar & Somerville Reference Cózar and Somerville2005b), which can be correlated to the Assemblages 3–4 of the N Pennine area (Cózar & Somerville Reference Cózar and Somerville2004). In the Archerbeck Beds 3 interval are observed the final peaks of Kamaena, the last specimens of Ungdarella and, in general, a disappearance of most algae and Algospongia, as well as a dramatic impoverishment (in abundance) of specimens of the survivor taxa. This event is recorded in Ireland in Algal Assemblage E and in northern England in Assemblage 4 and the base of Assemblage 5, of unquestioned Brigantian affinity. The problem with the assemblages in northern England is that Assemblage 4 in the deeper water platform facies of the regional substage boundary stratotype of the Brigantian, Janny Wood, is recognised in Asbian to Brigantian beds (from the Knipe Scar Limestone up to the Peghorn Limestone), whereas in the platform facies of the Alston Block, the Assemblage 3, is recognised up to the Robinson Limestone, and Assemblage 4 from the Birkdale Limestone (Cózar & Somerville Reference Cózar and Somerville2004, fig. 15). This suggests a transition from deeper to shallower water platform facies, with late Asbian rock (Knipe Scar Limestone), transitional horizons (Robinson and Birkdale limestones) and the Brigantian (Peghorn Limestone Member). A similar scenario can be proposed for the Archerbeck Borehole; the first interval of the Archerbeck Beds (Archerbeck Beds 1) of undoubted late Asbian age, the second and third intervals (Archerbeck Beds 2 and 3) as transitional, and the Cornet Limestone as more typically Brigantian. However, the only typically Brigantian taxon in the Cornet Limestone is the green alga Paraepimastopora? (Cózar & Somerville Reference Cózar and Somerville2005a, Reference Cózar and Somervilleb). Furthermore, it can also be suggested that, owing to the FAD of the foraminifer Archaediscus karreri karreri and the impoverished algal/Algospongia assemblages, the Archerbeck Beds 3 interval might represent the base of the Brigantian, and only the Archerbeck Beds 2 interval would contain the Asbian/Brigantian transitional fauna and flora. Even so, the latter proposal could be questioned, because the Algospongia Fascifolium, which occurs in the Archerbeck Beds 2 interval, has been recorded only in Brigantian or younger rocks (Vachard & Cózar Reference Vachard and Cózar2010), although the poorly known stratigraphic range of this taxon and its limited records prevent a definite biostratigraphic use. The above scenario would be also supported by the FADs of the foraminiferans Parabradyina pararotula (Fig. 8c), Howchinia gibba and common Algospongia Falsocalcifolium punctatum from the upper part of the Penton Limestone. These taxa are markers of Assemblage 5 in northern England, recognised from the middle part of the early Brigantian (Cózar & Somerville Reference Cózar and Somerville2004). Thus, Assemblage 5 is assigned to the Penton, Bridge and unnamed Y limestones (Fig. 12).

Assemblage 6 is assigned to the Linns and Tombstone limestones due to the more common Falsocalcifolium, although the acme of this genus is recognised in the younger Harelawhill Limestone (Assemblage 7). This fact contrasts with its distribution in the Pennine region, where although common in both assemblages, it was more abundant in Assemblage 6 than in 7. In the Midland Valley of Scotland, limestone horizons assigned to Assemblage 6 are not well-represented, and assemblages are rather poor (Cózar et al. Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2010).

Only two possible candidates have been proposed in the literature as the base for the late Brigantian, the Gastropod and Harelawhill limestones (Holliday et al., Reference Holliday, Burgess and Frost1975; Strank, Reference Strank1981). Foraminiferal markers for the recognition of the late Brigantian in northern England are Planospirodiscus, Asteroarchaediscus, Endothyranopsis sphaerica, Biseriella, Climacammina and Janischewskina typica (Cózar & Somerville Reference Cózar and Somerville2004). Although some specimens might occur just at the top of the early Brigantian (e.g. Asteroarchaediscus in the Tyne Bottom Limestone Member of the Rookhope Borehole, Fig. 12; Johnson & Nudds, Reference Johnson and Nudds1996; Cózar & Somerville Reference Cózar and Somerville2004), they progressively occur from the base of the late Brigantian elsewhere. In the Archerbeck Borehole, Asteroarchaediscus, E. sphaerica and Planospirodiscus first occur in the Gastropod Limestone. Furthermore, Biseriella and Climacammina first occur in the Harelawhill Limestone. Those markers suggest that the base of the late Brigantian should be positioned at the base of the Gastropod Limestone (Fig. 12). The Gastropod and Harelawhill limestones are assigned to Assemblage 7. Interestingly, the acme of the Algospongia Falsocalcifolium is recorded in the Harelawhill Limestone, which coincides with the acme of this genus in the Midland Valley of Scotland (Cózar et al. Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2010), in Assemblage 7 (Hurlet Limestone in Fig. 12).

Assemblage 8 of the N Pennine region in Cózar & Somerville (Reference Cózar and Somerville2004) was later subdivided into Assemblages 8 to 10 by Cózar et al. (Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2008a, Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2010) on the basis of a more detailed investigation in the Midland Valley of Scotland (MVS). However, in the Archerbeck Borehole, the sequence seems to be much closer to the Pennines than to the MVS, and markers used to distinguish individual limestone horizons/assemblages in the MVS first occur together in the limestones in the Archerbeck Borehole. The markers of Assemblage 8 (of the MVS) occurring in unnamed Limestone X and the Buccleuch Limestone are the foraminiferans Eostaffella ex gr. pseudostruvei, Neoarchaediscus postrugosus and the acme of the Algospongia Calcifolium okense. However, the foraminifer Tubispirodiscus attenuatus first occurs earlier (Harelawhill Limestone) and the calcivertellids and Eostaffella ex gr. postmosquensis (E. acutiformis) later (Under Limestone). Markers of Assemblage 9, such as Tubispirodiscus hosiensis and T. simplissimus occur in the Under Limestone (Fig. 12). However, both are very rare and other markers of this assemblage have not been recorded. Assemblage 10 in the MVS is characterised by the foraminiferans Rectocornuspira (common), Planospirodiscus taimyricus, Euxinita pendleiensis, Endothyranopsis plana, Tubispirodiscus absimilis and Archaediscus at tenuis stage. The first taxon is rare and only present in Limestone W. On the other hand, E. plana and A. at tenuis stage first occur in the Under Limestone. The other three taxa first occur in the Catsbit Limestone.

This mixture of FADs is interpreted as follows: unnamed Limestone X and Buccleuch Limestone are assigned to Assemblage 8, and the Under, Catsbit, unnamed Limestone W and Blae Pot limestones to a combined Assemblage 9–10 (Fig. 12). Thus, the recognition of Assemblage 9 is considered as highly regional, limited strictly to the MVS. Some implications arise from this rearrangement. First, the base of the Pendleian (Serpukhovian) has to be considered at least as Assemblage 9, despite the absence of key worldwide taxa in the MVS. This new assignment is based on the recognition that if, lithologically, the Top Hosie/Second Hosie limestones are correlated with the Catsbit Limestone and the latter in turn with the Great Limestone and Main Limestone in the Alston and Askrigg blocks respectively, it is now admitted that the base of the Serpukhovian is situated below the Four Fathom Limestone Member in northern England (Arthurton et al. Reference Arthurton, Johnson and Mundy1988), although this member generally lacks foraminiferal markers for the Pendleian. Secondly, this biostratigraphical correlation highlights a problem, because the lithological correlations of Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961) and Dean et al. (Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011) correlated the Buccleuch Limestone with the Four Fathom Limestone Member and, in fact, the latter authors assigned that formal member name to the horizon in the Archerbeck Borehole. The lithological description of the Four Fathom Limestone Member by Dean et al. (Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011) acknowledges that this member is not particularly fossiliferous in the Alston Block, which is corroborated by the poor microfauna in the Rookhope Borehole (Cózar and Somerville Reference Cózar and Somerville2004, figs 4–5), except for the acmes of Calcifolium okense and floods of Saccamminopsis. Lumsden & Wilson (Reference Lumsden and Wilson1961) described bands of Saccamminopsis and the microproblematicum Draffania in the Buccleuch Limestone, corroborated here (). Dean et al. (Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011) also considered the Three Yard Limestone Member to be more fossiliferous than the Four Fathom Limestone Member, although including bands of Saccamminopsis in the former member. Interestingly, Holliday et al. (Reference Holliday, Burgess and Frost1975) correlated the Buccleuch Limestone with the Three Yard Limestone (and the Acre Limestone) in the Northumberland Trough in which Calcifolium okense was recorded and in some sections represents its first occurrence. As a result of these contradictory data, it will be necessary for further studies to be undertaken on the Three Yard Limestone and Four Fathom Limestone members in order to obtain a better micropalaeontological characterisation for validating any correlation and to establish criteria for recognising the Viséan–Serpukhovian boundary.

3.1. Biozones in the British Isles and their correlation in Europe and N Africa

Since early times, the knowledge of the Carboniferous limestone horizons in Britain allowed a characterisation of the lithological and palaeontological features, and a subsequent detailed analysis has allowed a progressive enrichment in the palaeontological database of each horizon. Mississippian biozones proposed for the British Isles, thus, have a high degree of reliability and precision. However, most of those biozones can be only regarded as regionally significant and their use elsewhere beyond the British Isles is less precise. This problem is even more significant owing to the benthic nature of the Mississippian foraminiferans and their migrations from the central and eastern Palaeotethys (Mamet Reference Mamet, Kauffmann and Hazel1977). This constraint complicates notably the proposals for worldwide markers. With regard to all those proposed biozones for the uppermost late Viséan in the Russian and Ukraine basins (e.g. Lipina & Reitlinger Reference Lipina and Reitlinger1971; Stepanov & Donakova Reference Stepanov, Donakova and Sokolov1982; Poletaev et al., Reference Poletaev, Brazhnikova, Vasilyuk and Vdovenko1991; Kulagina et al. Reference Kulagina, Gibshman and Pazukhin2003), taxa used to distinguish zones occur in Britain at (i) different levels (e.g. Archaediscus gigas), (ii) synchronously (e.g. Eostaffella proikensis and Eostaffella ikensis) or (iii) are not present in the British upper Viséan carbonate platforms (e.g. Loeblichia ukrainica, Eostaffella tenebrosa). During the Serpukhovian, similarly, taxa occur at different levels in Britain than in Russia and the Ukraine (e.g. Tubispirodiscus cornuspiroides, Endostaffella parva, Neoarchaediscus postrugosus, Planoendothyra) or they are unrecorded (e.g. most species of Eolasiodiscus/Monotaxinoides of the Donetz region, Pseudoendothyra globosa, Millerella pressa, Globivalvulina moderata, Globivalvulina kamensis).

In basins of the western Palaeotethys closer to Britain (e.g. Belgium and N France), foraminiferal zones or markers are more similar to those recorded and used in the Archerbeck Borehole and elsewhere in Britain and Ireland, but precision of those zones is less refined. Compared with the markers used by Conil et al. (Reference Conil, Groessens, Laloux, Poty and Tourneur1991) in Belgium and N. France, Loeblichia coincides as a marker for the early Brigantian (lower Cf6δ subzone), although as demonstrated by Cózar & Somerville (Reference Cózar and Somerville2004), it never occurs from the base of this regional substage (in Assemblage 5 of the Pennines). Climacammina and Janischewskina are also used by Conil et al. (Reference Conil, Groessens, Laloux, Poty and Tourneur1991) as markers for the late Brigantian (upper Cf6δ subzone), which coincides with the Assemblage 6 in the Pennines. On the other hand, the records of Monotaxinoides in the Archerbeck Borehole are in younger rocks than those proposed by Conil et al. (Reference Conil, Groessens, Laloux, Poty and Tourneur1991) in the uppermost latest Viséan (approximately latest late Brigantian), as well as in the Ukraine (Vdovenko Reference Vdovenko2001). This resolution is virtually the same as that documented by Poty et al. (Reference Poty, Devuyst and Hance2006), between their zones MFZ14 and MFZ15 (late Asbian-Pendleian). The single difference is that the latter authors restricted the stratigraphic range of Biseriella parva to its co-occurrence with Janischewskina and Climacammina (late Brigantian, as previously proposed by Cózar & Somerville Reference Cózar and Somerville2004). The scenario for the Pendleian is much worse because Conil et al. (Reference Conil, Groessens, Laloux, Poty and Tourneur1991) did not propose any markers for this substage, and this substage is overlooked in the upper part of the MFZ15 of Poty et al. (Reference Poty, Devuyst and Hance2006), also without any foraminiferal markers.

The closest basins in which a comparison can be established, are in the Central Meseta of N. Morocco (Cózar et al. Reference Cózar, Vachard, Somerville, Berkhli, Medina-Varea, Rodríguez and Said2008b, Reference Cózar, Said, Somerville, Vachard, Medina-Varea, Rodríguez and Berkhli2011) and the Saharan basins in S. Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia (e.g. Lys Reference Lys, Wagner, Winkler Prins and Granados1985). However, the stratigraphic range of the taxa in the Sahara is controversial and not well-documented enough (see discussion in Cózar et al. Reference Cózar, Said, Somerville, Vachard, Medina-Varea, Rodríguez and Berkhli2011). In the Moroccan Meseta, similar stratigraphic ranges to the Archerbeck Borehole are observed in taxa such as Biseriella parva, Euxinita pendleiensis, Neoarchaediscus postrugosus, calcivertellids, Eostaffella pseudostruvei, Archaediscus at tenuis stage, “Millerella”, Endothyranopsis plana, although Tubispirodiscus, Monotaxinoides and Eosigmoilina occur later in Morocco.

It is difficult with this amount of range mismatch in different basins to establish solid markers, but from a worldwide biostratigraphical point of view, the FAD of some taxa in the Archerbeck Borehole can be closely compared to the known range of those taxa elsewhere outside the UK:

• FAD of Asteroarchaediscus baschkiricus, Planospirodiscus taimyricus, Eostaffella ex gr. pseudostruvei, Neoarchaediscus postrugosus and common Tubispirodiscus in the uppermost late Brigantian.

• Archaediscus at tenuis stage, Eosigmoilina, calcivertellids, Endothyranopsis plana, Eostaffella postproikensis and Eolasiodiscus as typically Pendleian (Serpukhovian) taxa.

4. Correlation with the Midland Valley of Scotland (MVS) and northern England

In general terms and despite the different local limestone names, the upper succession of the Archerbeck Borehole, from the Callant Limestone upwards, can be closely correlated with that of northern England, more so than with the MVS (Fig. 12). The assemblages show similar patterns, and the transitional beds and members equate to those observed in Janny Wood and in the Alston Block (e.g. in the Rookhope Borehole, see Johnson & Nudds Reference Johnson and Nudds1996). Markers and assemblages for the base of the late Brigantian seem to be uniform in both regions, and no conclusions of provinciality can be recognised. The Brigantian/Pendleian boundary is similar between the Archerbeck Borehole and the northern Pennines. Unfortunately, this Viséan/Serpukhovian boundary is not well documented in the MVS because of the poor development of limestone horizons for this interval and the absence of diagnostic ammonoids (Cravencoeras leion), and in the Pennines because of the poor micropalaeontological assemblages of the Four Fathom Limestone Member and the Iron Post Limestone. However, the proximity of the MVS dominates the distribution of some taxa, such as Falsocalcifolium. Moreover, there is an apparent major influence of the MVS on the composition of the foraminiferal assemblages of the Archerbeck Borehole, reflected by the occurrence of many taxa described from there (e.g. Praeostaffellina, Praeplectostaffella, Euxinita pendleiensis, Parajanischewskina, Tubispirodiscus hosiensis, Archaediscidae new genus; Cózar & Somerville Reference Cózar and Somerville2006; Cózar et al. Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2008a). However, it has to be acknowledged that more material (thin sections) from this interval has been examined by the present authors from the MVS. This is turn has meant that specimens of those taxa are more numerous in the MVS, a fact which allows for a better characterisation of the species. However, those taxa also occur in the N. Pennines (unpublished data). The most unusual taxon, Archaediscidae new genus (three specimens in the MVS, two in the Archerbeck Borehole), is also recorded in Morocco, North Africa (one specimen), but, thus far, has not been recorded in northern England. The positioning of the Viseán/Serpukhovian boundary in the Archerbeck Borehole is still enigmatic, with clear Serpukhovian markers from the Under Limestone but absent from the underlying Buccleuch Limestone. As a consequence, the proposal of Dean et al. (Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011) to correlate the Buccleuch Limestone with the Four Fathom Limestone Member in northern England has to be treated with circumspection. In contrast, the correlation of this upper part of the borehole by Holliday et al. (Reference Holliday, Burgess and Frost1975) biostratigraphically, seems to be more correct (the Buccleuch Limestone would be equivalent to the Three Yard Limestone Member; Fig. 12) and is supported by microfossil data presented herein.

Owing to their stratigraphical position and biostratigraphy, only the Eelwell Limestone Member (equivalent to the Five Yard Limestone Member) to replace the Harelawhill Limestone and the Great Limestone Member to replace the Catsbit Limestone as proposed by Dean et al. (Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011) could be confirmed here (Fig. 12).

5. Taxonomic remarks on the archaediscids

The archaediscids in Assemblages 8 to 10 in the Archerbeck Borehole are extremely rich and diverse, and interesting taxa have been recorded. Of particular note is the occurrence of a new genus of Archaediscidae characterised by the early development of septa (cf. Cózar et al. Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2010), which only occurs in the Great Limestone Member (Fig. 11q). It is similar to specimens recorded in the Midland Valley of Scotland from the Main Hosie Limestone, in Assemblage 9, which would corroborate the assignment of this assemblage to the Pendleian. Unfortunately, at present, there are not enough well-preserved and well-oriented specimens to enable this new genus to be formally defined.

The specimens of Archaediscus at tenuis stage occur consistently in the Under, Great and Blae Pot limestones (Fig. 11n, o), of Pendleian age. Doubtful specimens occurs in older levels (e.g., Fig. 11m) but they might correspond, however, to another transitional form between the angulatus and tenuis stages, which first occurs from the Gastropod Limestone (Fig. 11i-l).

Brownediscus is generally considered as endemic to the Tramaka encrinite in Belgium (Austin et al. Reference Austin, Conil, Groessens and Pirlet1974), and confined to the late Serpukhovian. However, a transitional form seems to exist in the Archerbeck Borehole in the Blae Pot Limestone (Fig. 11p). The inner whorls do not show a typical tenuis stage, but the middle and outer whorls reveal a reduced thin wall and evolute arrangement, more than in the typical Tubispirodiscus recorded here (Fig. 11e, f) and in the common assemblages in the Midland Valley of Scotland (see Cózar et al. Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2008a).

One of the most striking features of the archaediscids in the Archerbeck Borehole is the occurrence of two species of Eosigmoilina (Eosigmoilina robertsoni and E. sp. 1). The genus is first recorded elsewhere in the early Serpukhovian, although never at the base of this stage (see revision in Cózar et al. Reference Cózar, Said, Somerville, Vachard, Medina-Varea, Rodríguez and Berkhli2011). In addition, a second problem arises with the potential synonymy of Eosigmoilina explicata described by Ganelina (Reference Ganelina, Kiparisova, Markovsky and Radchenko1956) (subsequently split into numerous subspecies by Brazhnikova (Reference Brazhnikova1964)) with Trochammina robertsoni Brady, Reference Brady1876. This synonymy was first suggested by Armstrong & Mamet (Reference Armstrong and Mamet1977) and supported by Brenckle et al. (Reference Brenckle, Ramsbottom and Marchant1987) and Brenckle (Reference Brenckle1993). It is difficult to confirm or reject this synonymy, because specimens collected by Brady (Reference Brady1876) were extracted from shales, and he only illustrated external views. Brenckle (Reference Brenckle1993) illustrated, in a transparent medium, syntypes preserved in the Natural History Museum, London other than those whose microphotographs had been taken with transmitted light. Those microphotographs confirm the quinqueloculine coiling, and the apparent hyaline wall, faintly radial. According to Brady (Reference Brady1876), the original material was collected from old and disused quarries that are currently filled and resampling is not possible a common problem in those small outcrops of the Midland Valley of Scotland (see also Cózar et al. Reference Cózar, Somerville and Burgess2010). Furthermore, due to the disproportionate amount of local names within the Midland Valley of Scotland for limestone horizons, the location is also controversial, because Brady (Reference Brady1876) equated the Gair Limestone with Shales above No. 5 Limestone of the Midlothian Series. This level should correspond to the Passage Formation, mostly of Bashkirian age, and not to the Upper Limestone Formation, to which Brady (Reference Brady1876) assigned the outcrops (upper part of early Serpukhovian to late Serpukhovian). The closest sectioned specimen to the “stratotype” and type level is that illustrated by Fewtrell et al. (Reference Fewtrell, Ramsbottom, Strank, Jenkins and Murray1981) from the Castlecary Limestone (Upper Limestone Group) in Lanarkshire (Lanark is situated less than 10 km from the Carluke area in which were collected the original specimens of Trochammina robertsoni).

Brenckle et al. (Reference Brenckle, Ramsbottom and Marchant1987) and Brenckle (Reference Brenckle1993) also synonymised Eosigmoilina radtchenkovensis Ganelina, Reference Ganelina, Kiparisova, Markovsky and Radchenko1956nomen nudum, Archaediscus? namuriensis Dain in Bykova et al., Reference Bykova, Balakmatova, Vassilenko, Voloshina, Dain, Ivanova, Kusina, Kuznetsova, Koryseva, Morozova, Maitliuk and Subbotina1958 and Quasiarchaediscus pamiriensis Miklukho-Macklay, 1960 with Eosigmoilina robertsoni. As with any fossil species, it is difficult to establish which features can be considered as valid for species determination, but an approach in other groups or genera might be also applied to the eosigmoilinids. When considering the holotypes and paratypes, a clear morphological difference can be observed between those species, such as the angularity of the periphery: almost keeled (E. namuriensis), subangular (E. explicata), pointed (E. robertsoni), and subrounded (Q.? pamiriensis). Biometric analysis in Eoparastaffella characterised the morphology of the numerous species recorded in this genus around the Tournaisian–Viséan boundary (e.g. Devuyst & Kalvoda Reference Devuyst and Kalvoda2007). A similar study could be applied to the Eosigmoilina species, because, although in the holotypes the morphology is generally clear, other specimens illustrated in the literature are confusing (e.g. in Brazhnikova Reference Brazhnikova1964), and possibly correspond to a mixture of species in different oblique sections. Further biometric analyses would demonstrate with numerical ranges this difference observed in the periphery of the types.

Quasiarchaediscus was described as having a finely perforated wall, with pores more visible than in Eosigmoilina. It is difficult to be precise about the amount of pores, to decide if the genus can be admitted, because the preservation of those pores can be also conditioned by palaeoecological and diagenetic factors (Brenckle Reference Brenckle1993). However, Q.? pamiriensis is a much more rounded form than the rest of the Eosigmoilina species, of a greater size, and it first occurs much earlier, in the latest Viséan (Miklukho-Maklay Reference Miklukho-Maklay and Markovsky1960), whereas the rest of the species of Eosigmoilina have been never recorded below the Serpukhovian. A specimen, identified as Quasiarchaediscus? aff. pamiriensis has been recorded in the uppermost late Brigantian of the Archerbeck Borehole (Fig. 11r, unnamed Limestone X), which confirms the original stratigraphic range proposed by Miklukho-Maklay (Reference Miklukho-Maklay and Markovsky1960). The specimen seems to be a more oblique section than the holotype of the nominal species, and the poor preservation prevents any further interpretation on the wall structure. Thus, temporarily, the genus Quasiarchaediscus? is retained as valid (with a question mark). Higher up in the Serpukhovian, in the Blae Pot Limestone, Eosigmoilina with pointed peripheries are recorded (E. robertsoni; Fig. 11w–z). However, other specimens are recorded from the Great Limestone Member (Eosigmoilina sp. 1; Fig. 11s–v). The latter are smaller, and seem to present also pointed to subrounded peripheries. They might correspond to juveniles of E. robertsoni, but with the current data, and in the absence of an ontogenetic characterisation of the species, a positive identification cannot be confirmed.

Thus, assemblages of archaediscids are very rich and in which the phylogenetic lines are complete or virtually complete. This factor gives to the Archerbeck Borehole a further importance for the study of this group, namely to establish clear criteria for the Viséan–Serpukhovian boundary. Unfortunately, the scarce material already sectioned from the borehole is a drawback, as is the preservation of specimens, which is far from perfect (see Fig. 11). Other sections in natural outcrops from the Midland Valley of Scotland and northern England might contribute new specimens and more numerous material for establishing the criteria of the archaediscid genera and their precise stratigraphic range.

6. Conclusions

In terms of limestone horizons, the Archerbeck Borehole can be more closely compared with those in the Alston Block (northern England), mostly in the upper part of the borehole in the Alston Formation (from the Callant to Catsbit limestones), although this might be an effect of the poorly developed limestones during the Asbian and early Brigantian of the Midland Valley of Scotland. In terms of microfaunal/microfloral assemblages, they are generally rather uniform compared to the Pennines area, although the acme of the Algospongia Falsocalcifolium is stratigraphically higher, as it is in the Midland Valley of Scotland. On the other hand, the mixture of key taxa in the upper part of the borehole is closely comparable to that in the Pennines, and not observed in the well-“stratified” succession of occurrences of markers recognised for the Midland Valley of Scotland. Thus, the foraminiferal Assemblages 9 and 10 recognised in the latter, cannot be distinguished in the Archerbeck Borehole.

The Asbian–Brigantian boundary interval contains similar assemblages as those recognised in the Janny Wood stratotype section and in the Alston Block, with beds assigned to the late Asbian (Archerbeck Beds 1 interval), transitional beds in the Archerbeck Beds intervals 2 and 3, which are compared to the Robinson and Birkdale limestones, and above them, the Cornet Limestone, as the first typically Brigantian horizon, correlated with the Peghorn Limestone Member (Fig. 12). The Gastropod Limestone is considered to be the base of the late Brigantian, and correlated with the Scar Limestone Member and Hurlet Limestone, in the Alston Block and Midland Valley of Scotland respectively. The base of the Serpukhovian with foraminiferal markers is established in the Under Limestone, coinciding with the base of the Assemblage 9/10. This limestone is likely equivalent to the Four Fathom Limestone Member in the Alston Block and Main/Mid Hosie limestones (Midland Valley of Scotland; Fig. 12). In terms of lithostratigraphic nomenclature the recently defined members of the Alston Formation in the Alston Block by Dean et al. (Reference Dean, Browne, Waters and Powell2011) are not easily applied in the Archerbeck Borehole. Only the Eelwell Limestone and Great Limestone members seem to be lithostratigraphically and biostratigraphically well characterised (Fig. 12).

Numerous foraminiferal markers are identified, which allow the recognition of Assemblages 4 to 10 of those described in the N. Pennines and Midland Valley of Scotland. However, protista and algal communities were more diverse, and assemblages are recognised in terms of abundance and diversity. Most of them coincide with biostratigraphical zones or assemblages, but others are only related to particular palaeoecological conditions in the succession. In general, the assemblages are very rich and diverse from the base of the studied interval (Archerbeck Beds). Nevertheless, the diversity in the archaediscids in the upper part of the borehole (from the unnamed Limestone X to the Blae Pot Limestone), in which almost entire phylogenetic lineages are identified between Archaediscus and Eosigmoilina, as well as the incipient Tubispirodiscus–Brownediscus transition, should be noted particularly.

7. Acknowledgements

The revised version of this paper has been improved notably by comments by the reviewers Colin Waters and Jiri Kalvoda. The authors would like to thank Mark Dean of the British Geological Survey (Palaeontological Unit, Edinburgh), who kindly allowed the examination of the material from the Archerbeck Borehole. This research was supported by the projects CGL2009–10340/BTE, of the Ministerio Español de Economía y Competitividad.

8. Supplementary Material

and are published as Supplementary Material with the on-line version of this paper. This is hosted by the Cambridge Journals Online service and can be viewed at http://journals.cambridge.org/tre