The Hemiptera Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758 is one of the most successful lineages of insects, with over 300 families recognised during its geological history and high variability of morphology (Shcherbakov & Popov Reference Shcherbakov, Popov, Rasnitsyn and Quicke2002; Szwedo et al. Reference Szwedo2004; Grimaldi & Engel Reference Grimaldi and Engel2005; Szwedo Reference Szwedo2018). The order is divided into six suborders: the extant Sternorrhyncha, Fulgoromorpha, Cicadomorpha, Coleorrhyncha and Heteroptera, and the extinct Paleorrhyncha. The last one currently comprises only one family, Archescytinidae, which needs re-study and reconsideration. The Hemiptera have been known since the Late Carboniferous (Nel et al. Reference Nel, Roques, Nel, Prokin, Bourgoin, Prokop, Szwedo, Azar, Desutter-Grandcolas, Wappler, Garrouste, Coty, Huang, Engel and Kirejtshuk2013) and they are likely to have been exclusively represented in the Palaeozoic by herbivorous taxa. Advanced plant sucking was the primary feeding adaptation in this lineage, which probably originated from ancestral Hypoperlida. The Permian Paleorrhyncha show some characters suggesting that both immatures and adults could have fed on gymnosperm ovules and/or immature seeds in cones, which is in accordance with the postulated plesiomorphic feeding on reproductive plant organs in general. Hemipterans evolved to shift from reproductive organs to photosynthetic tissues. Most of the Hemiptera since the Palaeozoic have been phloem feeders, whereas xylem feeding appeared in the Cicadomorpha in the Early Mesozoic. Mesophyll feeding probably also evolved during the Mesozoic. In the Hemiptera, predation is rare and occurs sporadically in modern Heteroptera; however, true bugs adopted zoophagy at the earliest stages of their evolution in the Triassic (Shcherbakov & Popov Reference Shcherbakov, Popov, Rasnitsyn and Quicke2002; Zherikhin Reference Zherikhin, Rasnitsyn and Quicke2002; Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov2008). Sap-feeding Hemiptera present one of the most extraordinary systems of close and mutual relationships containing obligate bacterial symbionts (Moran et al. Reference Moran, Tran and Gerardo2005; Szwedo Reference Szwedo2018).

The Palaeogene record of the Hemiptera is based on both compression fossils and amber inclusions throughout the world (e.g., EDNA 2018; PalaeoBioDB 2018 and references there).

Fossil assemblages from the Palaeocene are often dominated by the representatives of Fulgoroidea or Cercopoidea, while the other groups are not so abundant. Aphidomorpha are sometimes abundant, but Psyllodea are rather rare. Both Aleyrodomorpha and Coccomorpha are not very common in fossil assemblages. The most abundant water bugs are Nepomorpha (mainly Notonectidae and Corixidae), and the most abundant land bugs are Cimicomorpha (Miridae) and Pentatomomorpha (mainly Coreoidea and Pentatomoidea). Dominance of fulgoroids is usually related to warmer climatic conditions whereas a predominance of cercopoids represents a cooler climate. At the beginning of the Palaeogene a rapid evolution of the most specialised plant-sucking lineages of the Hemiptera continued, connected with the diversification of angiosperms and Cenophytic conifer lineages.

The early Cenozoic (Palaeogene) Bembridge Marls of the Isle of Wight is well known. Within it, the Insect Bed (Insect Limestone) occurs only in the northern half of the Isle of Wight. Most information dealing with the palaeontology, lithology and the age was summarised by Jarzembowski (Reference Jarzembowski1980) and more recently by Ross & Self (Reference Ross and Self2014). There has been disagreement about the age of the Insect Bed and on the position of the Eocene/Oligocene boundary. It has been considered to be Late Eocene (late Priabonian) or Early Oligocene (early Rupelian) in age (Jarzembowski Reference Jarzembowski1980; Collinson Reference Collinson, Prothero and Berggren1992; Hooker et al. Reference Hooker, Collinson, Van Bergen, Singer, De Leeuw and Jones1995, Reference Hooker, Collinson and Sille2004, Reference Hooker, Collinson, Grimes, Sille and Mattey2007, Reference Hooker, Grimes, Mattey, Collinson, Sheldon, Koeberl and Montanari2009; Ross & Self Reference Ross and Self2014). Gale et al. (Reference Gale, Huggett, Pälike, Laurie, Hailwood and Hardenbol2006, Reference Gale, Huggett and Laurie2007) investigated magnetostratigraphy, clay mineralogy, cyclostratigraphy and sequence stratigraphy postulating an Early Oligocene age for the Insect Bed. However, Hooker et al. (Reference Hooker, Collinson, Grimes, Sille and Mattey2007, Reference Hooker, Grimes, Mattey, Collinson, Sheldon, Koeberl and Montanari2009) disagreed. Hooker et al. (Reference Hooker, Grimes, Mattey, Collinson, Sheldon, Koeberl and Montanari2009) indicated that the Bembridge Marls were deposited over about 300,000 years, which would date the Insect Bed at about 34.2Ma (±/∼100,000 years) and indicate that the Insect Bed was deposited over about 10,000–15,000 years, i.e., Late Eocene (Ross & Self Reference Ross and Self2014), which is followed here. The Bembridge Marls fauna, with regards to its family composition, differs from other European Eocene faunas: Baltic (including Bitterfeld and Ukrainian) amber, Oise amber and Messel. The Bembridge Marls age can be directly compared with that of the Florissant Formation in the USA, which is radiometrically dated at 34.07 million years old (Meyer Reference Meyer2003).

The Hemiptera from the Bembridge Marls, Isle of Wight, were studied by Cockerell (Reference Cockerell1915, Reference Cockerell1921b, Reference Cockerellc, Reference Cockerell1922, Reference Cockerell1926, Reference Cockerell1927) and Klimaszewski & Popov (Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993), and resulted in the description of several taxa of psyllids and aphids (Sternorrhyncha), planthoppers (Fulgoromorpha), leafhoppers (Cicadomorpha) and true bugs (Heteroptera).

The Palaeogene and Neogene record of Psyllodea is poor (Becker-Migdisova Reference Becker-Migdisova1985; Grimaldi & Engel Reference Grimaldi and Engel2005; Drohojowska Reference Drohojowska2011; Ouvrard et al. Reference Ouvrard, Burckhardt and Greenwalt2013). In addition to a few species from the Isle of Wight (Late Eocene), a few species are known from Eocene Baltic amber – Palaeopsylloides oligocaenicus (Enderlein, Reference Enderlein1915), Eogyropsylla eocenica Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski1993b, E. jantaria Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski1993b, Protoscena baltica Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski1997b, Eogyropsylla magna Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski1997c, E. parva Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski1997c, Parascenia weitschati Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski1997c (Enderlein Reference Enderlein1915; Klimaszewski Reference Klimaszewski1993b, Reference Klimaszewski1997b, Reference Klimaszewskic), Eogyropsylla sedzimiri Drohojowska, Reference Drohojowska2011 and E. paveloctogenarius Ouvrard et al., Reference Ouvrard, Burckhardt and Greenwalt2013 from the Middle Eocene Kishenehn Formation, Montana, USA, and a few from the terminal Eocene Florissant Formation in the USA (Scudder Reference Scudder1890). Representatives of the superfamily Psylloidea became more numerous in the fossil record from the Miocene, known from Dominican and Mexican ambers (Klimaszewski Reference Klimaszewski1993a, Reference Klimaszewski1996, Reference Klimaszewski1997a; Drohojowska et al. Reference Drohojowska, Wegierek and Solorzano-Kraemer2016).

Aleyrodomorpha are recorded in several Palaeogene ambers: ‘Aleurodes' aculeatus Menge, Reference Menge1856, Paernis gregorius Drohojowska & Szwedo, Reference Drohojowska and Szwedo2011b, Rovnodicus wojciechowskii Drohojowska & Szwedo, Reference Drohojowska, Perkovsky and Szwedo2015 in Drohojowska et al. Reference Drohojowska, Perkovsky and Szwedo2015 and Snotra christelae Szwedo & Drohojowska, Reference Szwedo and Drohojowska2016 from Baltic amber (Szwedo & Drohojowska Reference Szwedo and Drohojowska2016) and few additional specimens under survey; several taxa from the lowermost Eocene amber of Oise (Drohojowska & Szwedo Reference Drohojowska and Szwedo2013a) must be noted. Aleyrodomorpha as compression fossils from the Bembridge Marls were reported by Jarzembowski & Ross (Reference Jarzembowski and Ross1994). A few species were recorded from both compression fossils and amber from the Late Jurassic and Cretaceous (Schlee Reference Schlee1970; Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov2000a; Drohojowska & Szwedo Reference Drohojowska and Szwedo2011a, Reference Drohojowska, Szwedo, Azar, Engel, Jarzembowski, Krogmann, Nel and Santiago-Blay2013b, Reference Drohojowska and Szwedo2015), but this group remains poorly studied.

The scarcity of scale insect (Coccidomorpha) fossils is still a puzzle, but numbers of species representing both archeococcids and neococcids are known from fossil resins (Koteja Reference Koteja2000a, Reference Kotejab, Reference Koteja2001, Reference Koteja2008; Koteja & Azar Reference Koteja and Azar2008; Vea & Grimaldi Reference Vea and Grimaldi2012, Reference Vea and Grimaldi2015; Simon & Żyła Reference Simon and Żyła2015; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Xia, Wappler, Simon, Zhang, Jarzembowski and Szwedo2015). Compression fossils of scale insects are documented from the Lower Cretaceous of Transbaikalia (Koteja Reference Koteja1988, Reference Koteja1989) and England (Koteja Reference Koteja1999) – representing archeococcids (Matsucoccidae and Xylococcidae), Oligocene of North America (Scudder Reference Scudder1890), Miocene of Sicily (Pampaloni Reference Pampaloni1902, 1903; Koteja & Ben-Dov Reference Koteja and Ben-Dov2003), Eocene of Germany (Wappler & Ben-Dov Reference Wappler and Ben-Dov2008) and Miocene of Germany (Zeuner Reference Zeuner1938; Koteja Reference Koteja2000b) – representing neococcids (Diaspididae) – and the Miocene of Darjeeling in India (Bera et al. Reference Bera, Mitra, Banerjee and Szwedo2006).

Cenozoic fossil aphids (Aphidomorpha) have been studied in varying degrees. So far the largest number of species has been described from Baltic amber (about 100 species; Heie & Wegierek Reference Heie and Wegierek1998, Reference Heie and Wegierek2011). Late Eocene/Oligocene aphids (24 species) are known from several deposits around the world. Most of the compression fossils were described in the 18th and 19th Centuries: from Aix-en-Provence, France (Hope Reference Hope1847; Heer Reference Heer1856; Théobald Reference Théobald1937); Florissant, Colorado, USA (Scudder Reference Scudder1890; Cockerell Reference Cockerell1908b, Reference Cockerell1909, Reference Cockerell1913); Quesnel, British Columbia, Canada (Scudder Reference Scudder1890, Reference Scudder1894) and the Isle of Wight, UK (Cockerell Reference Cockerell1915, Reference Cockerell1921b). Some were later revised by Heie (Reference Heie1967, Reference Heie1970). Only specimens from East Siberia, Russia (Bolshaya Svetlovodnaya) and France (Céreste, Alpes de Haute Provence) were described much later (Heie Reference Heie1989; Heie & Lutz Reference Heie and Lutz2002). Where present, aphids are also numerous in Miocene insect deposits (20 species; Heie Reference Heie2005). Data on aphids from the more recent epochs (Pliocene and Pleistocene) are based on single species (Heie Reference Heie1968, Reference Heie1995).

The Fulgoromorpha is one of the most ancient lineages of the Hemiptera, and in the fossil record planthoppers have been known since the early Permian. The earliest Fulgoromorpha belong to the Permian superfamily Coleoscytoidea, the second taxon is the Permian–Triassic Surijokocixioidea; the Fulgoroidea have been known since the Jurassic. The Palaeogene record of Fulgoromorpha comprises both compression fossils and forms preserved in resins (ambers). These are present in the Palaeocene/Eocene Fur Formation of Denmark, Palaeocene/Eocene deposits of Menat in France, lowermost Eocene French amber, uppermost Palaeocene of Argentina, numerous specimens are known from Eocene Baltic amber, Eocene deposits of Germany, Eocene and Oligocene deposits of North America and China, and Miocene Dominican and Mexican ambers (Szwedo et al. Reference Szwedo2004; Petrulevičius Reference Petrulevičius2005; Szwedo Reference Szwedo2005a, Reference Szwedo2006a, Reference Szwedob, Reference Szwedo2007, Reference Szwedo2008, Reference Szwedo2011; Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov2006; Szwedo et al. Reference Szwedo, Bourgoin and Lefebvre2006; Szwedo & Wappler Reference Szwedo and Wappler2006; Stroiński & Szwedo Reference Stroiński and Szwedo2008, Reference Stroiński and Szwedo2011, Reference Stroiński and Szwedo2012; Emeljanov & Shcherbakov Reference Emeljanov and Shcherbakov2009; Lin et al. Reference Lin, Szwedo, Huang and Stroiński2010; Szwedo & Stroiński Reference Szwedo and Stroiński2010, Reference Szwedo and Stroiński2013, Reference Szwedo and Stroiński2017; Szwedo et al. Reference Szwedo, Stroiński and Lin2013, Reference Szwedo, Stroiński and Lin2015). Several fossil Fulgoroidea have been reported so far from the Late Eocene Bembridge Marls of the Isle of Wight. The first descriptions were by Cockerell (Reference Cockerell1921b), who described Poekilloptera melanospila Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921b (transferred to Orthoptera by Nel et al. Reference Nel, Prokop and Ross2008; see Fulgoromorpha section). Later, more species were added under the names Hastites muiri Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1922, Hooleya indecisa Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1922 and Myndus wilmattae Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1926. These taxa are discussed below.

The Cicadomorpha is the second suborder formerly placed together with Fulgoromorpha as ‘Auchenorrhyncha', but not related directly to planthoppers (Bourgoin & Campbell Reference Bourgoin and Campbell2002; Szwedo Reference Szwedo2002; Szwedo et al. Reference Szwedo, Bourgoin and Lefebvre2004). The Palaeogene record of Cicadomorpha is also rich and known throughout the world (Metcalf & Wade Reference Metcalf and Wade1966; Lewis Reference Lewis1989; Szwedo Reference Szwedo2005b), but many taxa require re-examination and revision (Gębicki & Szwedo Reference Gębicki and Szwedo2006). Only a few species of Cicadidae and Tettigarctidae are known from the Palaeogene of France, Scotland and North America (Boulard & Nel Reference Boulard and Nel1990; Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov2009; Moulds Reference Moulds2018); most of the known fossil cicadas are from the Miocene of Eurasia. Cercopoidea are quite common in Palaeogene deposits of North America, Greenland and Europe as well as in amber but most must be re-studied and their taxonomic status revised and/or confirmed. Membracoidea, Cicadellidae in particular, are frequently reported, but only a few species from the Palaeogene have been formally described (Szwedo Reference Szwedo2002; Szwedo Reference Szwedo2005b; Gębicki & Szwedo Reference Gębicki and Szwedo2006; Szwedo & Gębicki Reference Szwedo2008; Szwedo et al. Reference Szwedo, Gębicki and Kowalewska2010; Dietrich & Gonçalves Reference Dietrich and Gonçalves2014). Over 220 specimens from the Insect Limestone of the Isle of Wight, deposited in the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London, Maidstone Museum and Sedgwick Museum, Cambridge, representing Fulgoromorpha and Cicadomorpha were investigated.

The first true bugs from the Bembridge Marls were described by Cockerell (Reference Cockerell1921c, Reference Cockerell1927). He referred them to the Tingidae (Celantia? seposita Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921c), Lygaeidae (Lygaeites amabilis Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921b) and Pentatomidae – Pentatomites acourti (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921c). The last one was previously considered to be a lygaeid (Cockerell Reference Cockerell1921c). A list of families of Hemiptera recorded from the Late Eocene Insect Limestone of the Isle of Wight is presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Families of the Hemiptera recorded from the Late Eocene Insect Limestone of the Isle of Wight.

1 Including specimens recognised as representing separate species, but not formally described.

The insects are preserved in concretions or tabular bands of very fine-grained micrite, known as Insect Limestone. The unit where these concretions/bands occur is known as the Insect Bed, which lies towards the base of the Bembridge Marls Member (Solent Group: Bouldnor Formation). The most extensive collection from the Insect Limestone are specimens preserved at the NHM. They belong to the collections of E.J. A'Court Smith (purchased 1877 and 1883), Reverend P. B. Brodie (purchased 1898) and R. W. Hooley (purchased 1924). They are labelled ‘Gurnard Bay' or ‘Gurnet Bay' (which is an old name for Gurnard Bay); however, A'Court Smith collected specimens all the way from West Cowes to Newtown River on the NW side of the Isle of Wight (Jarzembowski Reference Jarzembowski1980; Ross & Self Reference Ross and Self2014). Most of the specimens probably came from Thorness Bay (Jarzembowski Reference Jarzembowski1976). Brodie and Hooley acquired parts of Smith's collection, so parts and counterparts of individual insects have turned up in all three collections. The parts and counterparts often have different numbers because they were registered at different times. An additional collection was discovered at the Sedgwick Museum, Cambridge, by A. J. Ross. This collection has also yielded counterparts of specimens at the NHM, which indicates that this is another part of the Smith collection. A label with ‘1883' on it suggests that the Sedgwick Museum acquired this collection in 1883, the same year that the NHM purchased specimens from Smith.

The following collections have been examined and contained the Hemiptera in their care:

BMB – Booth Museum of Natural History, Brighton

CAMSM – Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge.

MIWG – Museum of Isle of Wight Geology.

NHMUK – Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum, London.

USNM – Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA.

MNEMG – Maidstone Museum & Bentlif Art Gallery.

With the financial support of Project INTAS 03-51-4367, concerning the fauna and flora of the Isle of Wight, formerly described species were revised and additional material was examined resulting in new taxa that are described herein.

1. Systematic palaeontology

Order Hemiptera Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758

Jumping plant-lice (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Psylloidea)

by Jowita Drohojowska

The Eocene witnessed the emergence of the first representatives of the superfamily Psylloidea, commonly known as jumping plant-lice. The psyllid fauna of this epoch is known largely from Baltic amber (Enderlein Reference Enderlein1915; Klimaszewski Reference Klimaszewski1993a, Reference Klimaszewski1997a, Reference Klimaszewskib; Drohojowska Reference Drohojowska2011; Ouvrard et al. Reference Ouvrard, Burckhardt and Greenwalt2013). Late Eocene fossils from the Bembridge Marls of the Isle of Wight were studied by Cockerell (Reference Cockerell1915, Reference Cockerell1921b) and Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov (Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993). The record was not exceptionally rich, with all the species of this age classified in one family, the Aphalaridae, and even in one subfamily, the Aphalarinae. No new taxa are described here; however, there have been some taxonomic changes since Klimaszewski & Popov (Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) was published so the fauna is summarised below. All the specimen numbers in Klimaszewski & Popov (Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) are incorrect – they used field numbers, not registration numbers. Paratypes are from the same locality as the holotype unless stated otherwise.

In Early Miocene Dominican amber (Klimaszewski Reference Klimaszewski1996, Reference Klimaszewski1997c), species appear that belong to several other families. Apart from the Aphalaridae, there are also species of Psyllidae, Carsidaridae and Triozidae (Becker-Migdisova Reference Becker-Migdisova1964; Klimaszewski Reference Klimaszewski1993a). In the Miocene Mexican amber the first fossil psyllid from family Liviidae was described (Drohojowska et al. Reference Drohojowska, Wegierek and Solorzano-Kraemer2016). In the Paleogene the family Aphalaridae dominated, then in the Neogene the family Psyllidae outnumbered other forms. This has continued to the present day, with the domination of Triozidae (over 1000 described species) and Psyllidae (nearly 1200 species) (Ouvrard Reference Ouvrard2019).

Suborder Sternorrhyncha Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843

Infraorder Psyllodea Flor, Reference Flor1861

Superfamily Psylloidea Latreille, Reference Latreille1807

Key to the genera of jumping plant-lice from the Bembridge Marls

1. Cells m1 and cu1 large, vein M1+2 on the forewing the same length or longer than vein M Carsidarina

– Cells m1 and cu1 small, Vein M1+2 on the forewing visibly shorter than vein M 2

2. Cell cu1 relatively high, approximately as long as cell m1 Lapidopsylla

– Cell cu1 long and flat, distinctly longer than cell m1 3

3. Vein Cu1a very long and almost straight, cell cu1 almost flat (much longer than high) Paleopsylloides

– Vein Cu1a arcuate, cell cu1 not flat (much longer than high) Proeurotica

Family Aphalaridae Löw, Reference Löw1879

Subfamily Aphalarinae Löw, Reference Löw1879

Tribe Paleopsylloidini Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1985

Genus Proeurotica Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1985

Type species. Psylla exhumata Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915; by original designation.

Plesioaphalara Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993

Type species. Plesioaphalara arcana Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993; by original designation.

Diagnosis (after Becker-Migdisova Reference Becker-Migdisova1985 and Klimaszewski & Popov Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993). Length/width coefficient of forewing 2.3:1. Stem R+M short, slightly longer (1.1–1.2 times) than M+CuA and CuA. Rs long, straight, slightly curved at apex anteriad; stem R half of M+CuA stem length, 1.8 times shorter than stem CuA. Branches of M short, distinctly shorter than stem M. Cell cu1 with length/width coefficient 3.1–4.5.

Description. Forewing elongated, with long, narrow cell cu1. Stem R+M+CuA short, subequal to stem R. Cell m shorter than stem M.

Remark. The genus Plesioaphalara was synonymised under Proeurotica by Ouvrard et al. (Reference Ouvrard, Burckhardt and Greenwalt2013). Proeurotica exhumata (type species) differs from all other species recently moved by Ouvrard et al. (Reference Ouvrard, Burckhardt and Greenwalt2013) to the genus Proeurotica by the lack of a pterostigma. However, better preserved material is necessary to confirm or reject this situation.

Proeurotica exhumata (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915)

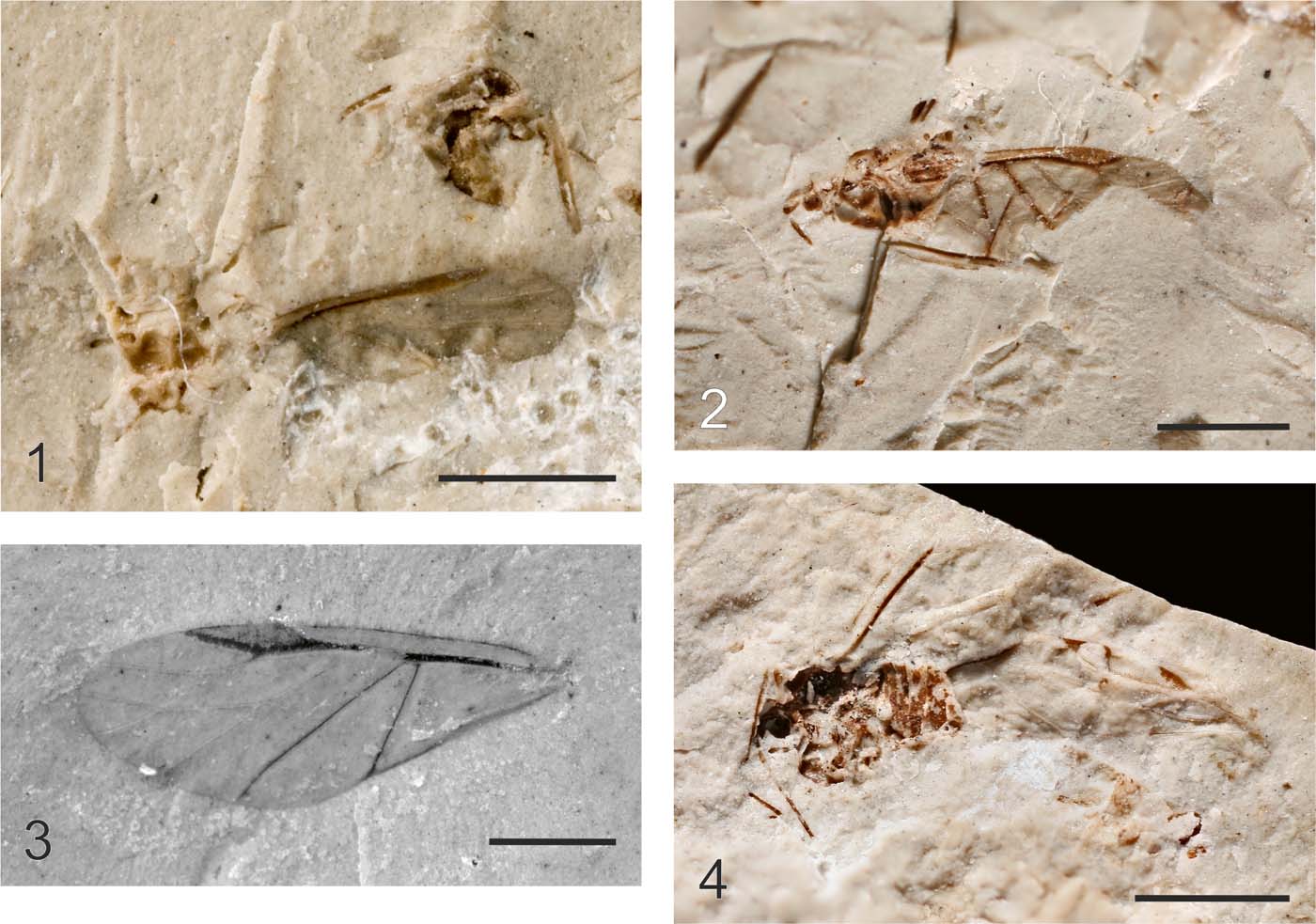

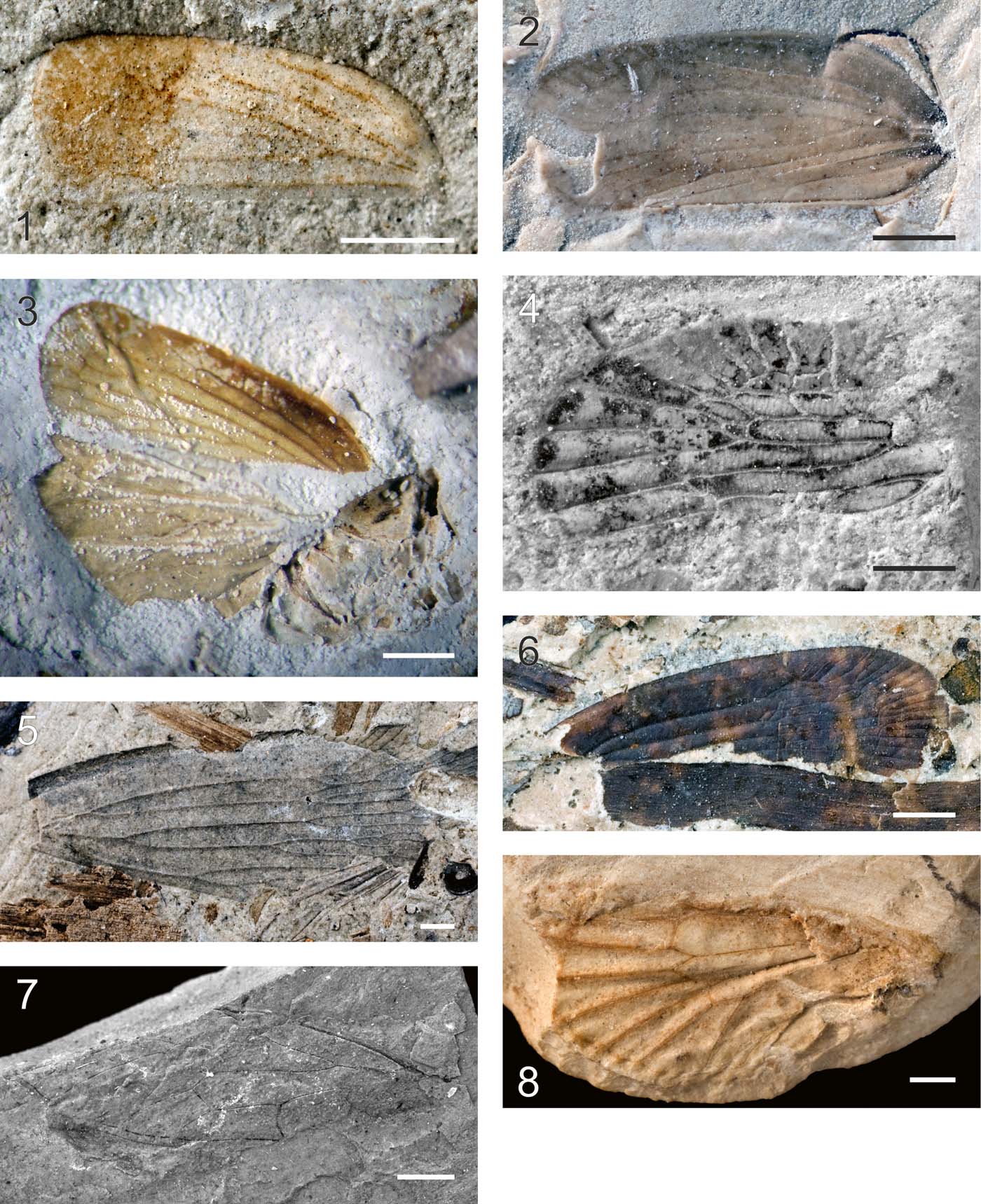

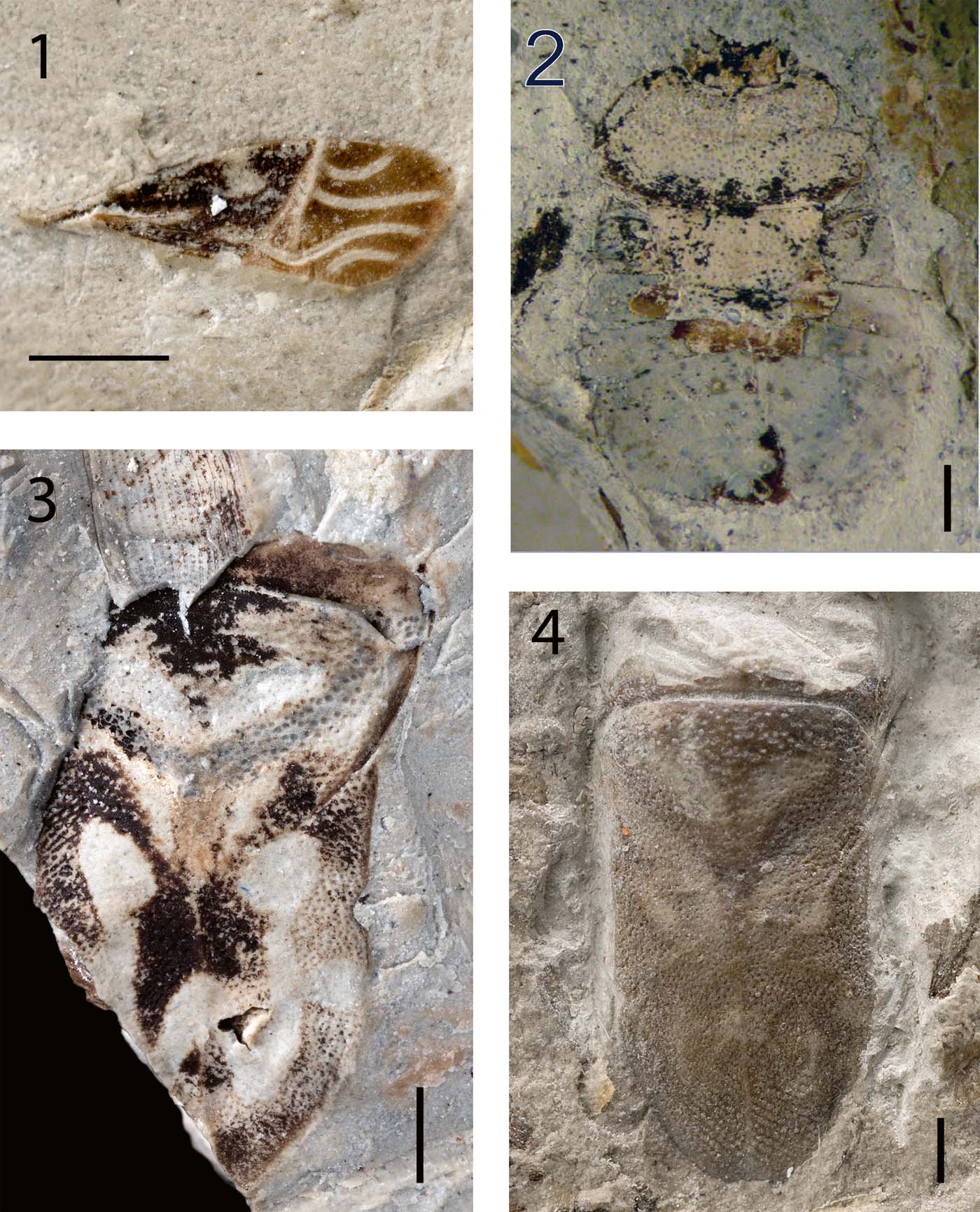

Plate 1 (1) Proeurotica exhumata (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915), holotype, USNM No. 61427. (2) Proeurotica arcana (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) holotype, BMB 018433, forewing. (3) Proeurotica paulula (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) holotype, BMB 018440, forewing. (4) Proeurotica inanima (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) holotype, BMB 018441, forewing. (5) Lapidopsylla thornessbaya Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993 holotype, BMB 018443, forewing. (6) Lapidopsylla memoranda Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993 holotype, BMB 018444, forewing. (7) Carsidarina hooleyi (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921) holotype, NHMUK In. 24358a, part, forewing. (8) Carsidarina jarzembowskii (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) holotype, BMB 018424-5, part, forewing. Scale bar=1mm.

Figures 1–8 Forewing. (1) Proeurotica exhumata (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915), holotype, USNM No. 61427. (2) Proeurotica arcana (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) holotype, BMB 018433. (3) Proeurotica paulula (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) holotype, BMB 018440. (4) Proeurotica inanima Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993 holotype, BMB 018441. (5) Lapidopsylla thornessbaya Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993 holotype, BMB 018443. (6) Lapidopsylla memoranda Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993 holotype, BMB 018444. (7) Carsidarina hooleyi (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921c) holotype, NHMUK In.24358a, part. (8) Carsidarina jarzembowskii (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) holotype, BMB 018424, part. Scale bar=1mm.

1915 Psylla exhumata Cockerell, p. 487, pl. 63, fig. 6.

1985 Proeurotica eshumata [sic]: Becker-Migdisova, p. 82.

1985 Proeurotica exhumata: Becker-Migdisova, p. 83, fig. 63.

1993b Paleopsylloides exhumatus: Klimaszewski, p. 10.

2013 Proeurotica exhumata Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915: Ouvrard et al., p. 24.

Holotype. USNM No. 61427, Lacoe Collection 7619, Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight.

Remarks. Klimaszewski (Reference Klimaszewski1993b) transferred Proeurotica exhumata (Cockerell Reference Cockerell1915) to the genus Paleopsylloides Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1985 on the basis of misinterpreted characters.

Proeurotica arcana (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) comb. nov.

1993 Plesioaphalara arcana Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, pp. 19–20; fig. 2b; pl. 2, figs 1–3.

2013 Plesioaphalara arcana Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993: Ouvrard et al., p. 24.

Holotype. BMB 018433 (BLS 1423); Insect Limestone, Thorness Bay, collected by A. A. Mitchell.

Paratypes. BMB 018434 (BLS 603), 018435 (BLS 1112), 018436 (BL 1319), 018437 (BL 131), 018438 (BL 145), all collected by A. A. Mitchell; 018439 (IL 61), collected by M. J. Warren.

Proeurotica paulula (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) comb. nov.

1993 Plesioaphalara paulula Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, pp. 20–21; fig. 3a; pl. 2, fig. 4.

2013 Plesioaphalara paulula Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski1993a: Ouvrard et al., p. 24.

Holotype. BMB 018440 (BLS 723–32); Insect Limestone, Thorness Bay, collected by A. A. Mitchell.

Proeurotica inanima (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) comb. nov.

1993 Plesioaphalara inanima Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, p. 21; fig. 3b; pl. 2, figs. 5, 6.

2013 Plesioaphalara inanima Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993: Ouvrard et al., p. 24.

Holotype. BMB 018441 (BLS 381); Insect Limestone, Thorness Bay, collected by A. A. Mitchell.

Paratype. BMB 018442 (BLS 978), Mitchell Collection

Key to the species of Proeurotica Becker-Migdisova

1. Costal margin of forewing straight, vein Rs subparallel to anterior margin of forewing exhumata

– Costal margin of forewing arcuate, vein Rs not subparallel to anterior margin of forewing 2

2. Length of forewing up to 1mm, width 0.45mm, very short and high cell m1 paulula

– Length of forewing more than 1mm, width more 0.5mm, cell m1 long 3

3. Length of forewing more 2mm, vein Cu1 longer than vein M+Cu1 inanima

– Length of forewing up to 2mm, vein Cu1 always shorter than vein M+Cu1 arcana

Genus Lapidopsylla Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993

Type species. Lapidopsylla thornessbaya Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993; by original designation.

1993 Lapidopsylla Klimaszewski: Klimaszewski & Popov, p. 21.

Lapidopsylla thornessbaya Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993

1993 Lapidopsylla thornessbaya Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993, p. 22; fig. 3c; pl. 2, fig. 7.

2013 Lapidopsylla thornessbaya Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski1993a, Reference Klimaszewski1993b: Ouvrard et al., p. 24.

Holotype. BMB 018443 (BLS 850-1); Insect Limestone, Thorness Bay, collected by A. A. Mitchell.

Lapidopsylla memoranda Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993

1993 Lapidopsylla memoranda Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993, pp. 22–23; fig. 3d; pl. 2, fig. 8.

2013 Lapidopsylla memoranda Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993: Ouvrard et al., p. 24.

Holotype. BMB 018444 (BLG 203); Insect Limestone, Thorness Bay, collected by A. A. Mitchell.

Key to the species of Lapidopsylla Klimaszewski

1. Length of forewing more than 2mm, vein M long, about twice as long as vein M1+2, vein Rs visibly, arched towards forewing margin memoranda

– Length of forewing about 1.5mm, vein M short, 1 5 times as long as vein M1+2, vein Rs almost straight thornessbaya

Genus Carsidarina Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1985

Type species. Livilla hooleyi Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921c; by original designation.

Remarks. Ouvrard et al. (Reference Ouvrard, Burckhardt and Greenwalt2013, p. 31) synonymised genus Palaeoaphalara Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski1993b with Carsidarina Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1985, thus three species described by Klimaszewski (in Klimaszewski & Popov Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) should be moved to Carsidarina. The genus Carsidarina Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1985 was moved from Carsidaridae to the tribe Palaeopsylloidini Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1985 of Aphalaridae: Aphalarinae (Ouvrard et al. Reference Ouvrard, Burckhardt and Greenwalt2013).

Carsidarina hooleyi (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921)

1921 Livilla hooleyi Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921c, p. 476, fig. 44.

1985 Carsidarina hooleyi: Becker-Migdisova, p. 86, fig. 66.

1992 Livilla: Carpenter, p. 253.

2013 Carsidarina hooleyi Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921 [sic]: Ouvrard et al., p. 24.

Holotype. NHMUK In. 24358a, b (H. 430/H.445) (part and counterpart) Hooley Collection, Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight.

Paratype. NHMUK In. 24359 (H. 449). Hooley Collection.

Carsidarina jarzembowskii (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) comb. nov.

1993 Palaeoaphalara jarzembowskii Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, pp. 16–17; fig. 1a–c; pl. 1, figs 1–4.

1996 Palaeoaphalara jarzembowski [sic!]: Klimaszewski, p. 25.

2013 Palaeoaphalara jarzembowskii Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993: Ouvrard et al., p. 24.

Holotype. BMB 018424-5 (IL 67 a, b) (part and counterpart); Insect Limestone, Thorness Bay, collected by A. J. Ross.

Carsidarina ampla (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) comb. nov.

Plate 2 (1) Carsidarina ampla (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) holotype, BMB 018431, forewing. (2) Carsidarina media (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) holotype, BMB 018426, forewing. (3) Paleopsylloides? anglica (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915), holotype, USNM No. 61426, forewing (arrowed), with the holotype of the ant Emplastus hypolithus (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915). (4) Aleyrodidae indet., MNEMG IB, SEM photo, puparium. (5–6) Aleyrodidae (?) indet., NHMUK II.2986a, b, puparium (?).

Figures 9–13 (9–11) Forewing: (9) Carsidarina ampla (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) holotype, BMB 018431, forewing; (10) Carsidarina media (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) holotype, BMB 018426; (11) Paleopsylloides? anglica (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915), holotype, USNM No.61426. Scale bar=1mm. (12) Schizoneurites brevirostris Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915, holotype, counterpart NHMUK I.9850: (A) general view; (B) right antenna. Scale bar=0.05mm. (13) Hormaphis? longistigma Wegierek sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK I.9595: (A) general view. Scale bar=0.05mm; (B) part of antennal segment. Scale bar=0.02mm.

1993 Palaeoaphalara ampla Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, pp. 17–18; fig. 2a; pl. 1, fig. 7.

2013 Palaeoaphalara ampla Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993: Ouvrard et al., p. 24.

Holotype. BMB 018431 (BL 64); Insect Limestone, Thorness Bay, collected by A. A. Mitchell.

Carsidarina media (Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) comb. nov.

1993 Palaeoaphalara media Klimaszewski in Klimaszewski & Popov, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993, p. 17; fig. 1d; pl. 1, figs. 5, 6.

2013 Palaeoaphalara media Klimaszewski, Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993: Ouvrard et al., p. 24.

Holotype. BMB 018426-7 (IL 62a, b) (part and counterpart); Insect Limestone, Thorness Bay, collected by A. J. Ross.

Paratypes. BMB 018428-9 (IL 6), collected by T. B. E. Jarzembowski; BMB 018430 (BL 50), collected by A. A. Mitchell.

Key to the species of Carsidarina Becker-Migdisova

1. Vein Rs straight, vein M in distal portion concave hooleyi

– Vein Rs gently curved, vein M in distal portion not concave 2

2. Cell m1 is shorter than cell cu1 jarzembowskii

– Cell m1 longer or the same length as cell cu1 3

3. Length of forewing more than 3mm, width about 1.4mm, vein M+Cu1 1.47 times as long as vein Cu1 ampla

– Length of forewing no more than 2.7mm, width no more than 1.15mm, vein M+Cu1 1.8–2.0 times as long as vein Cu1 media

Subfamily Aphalarinae Löw, Reference Löw1879

Tribe Aphalarini Löw, Reference Löw1879

Genus Paleopsylloides Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1985

Type species. Strophingia oligocaenica Enderlein, Reference Enderlein1915; by original designation by Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1985, p. 82.

Paleopsylloides? anglica (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915)

1915 Necropsylla anglica Cockerell, p. 487, pl. 63, fig. 5.

1985 Camaratoscena? anglica: Becker-Migdisova, p. 81, pl. 61.

1993b Paleopsylloides? anglica?: Klimaszewski, p. 11.

1993b Necropsylla angelica [sic]: Klimaszewski, p. 21.

2013 Camaratoscena? anglica (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915): Ouvrard et al., p. 24.

Holotype. USNM No. 61426, Lacoe Collection 7671. Next to the holotype ant (Formicidae) wing of Emplastus hypolithus (Cockerell Reference Cockerell1915), USNM No. 61411. Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight.

Remarks. This species has been described on the basis of a fragment of a forewing. The preserved part comprises only veins M1 and Cu1, the distal part of veins M+Cu1 and cells M1 and Cu1. Klimaszewski (Klimaszewski & Popov Reference Klimaszewski and Popov1993) suggested that this species should be transferred to the monotypic genus Paleopsylloides, distinguished by Becker-Migdisova (Reference Becker-Migdisova1985). Despite the paucity of data offered by the forewing, this suggestion seems plausible. The use of a synonymous name – Necropsylla angelica [sic] – in Klimaszewski (Reference Klimaszewski1993b) seems to have been a mere oversight.

Whiteflies (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Aleyrodidae)

by Jacek Szwedo and Jowita Drohojowska

The oldest known whiteflies so far are of the Upper Jurassic of Kazakhstan (Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov2000a); some others are recorded from the Early Cretaceous of England, Early Cretaceous Lebanese amber, Mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber Early Eocene Oise amber and Middle Eocene Baltic amber (Schlee Reference Schlee1970; Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov2000a; Azar Reference Azar2007; Drohojowska & Szwedo Reference Drohojowska and Szwedo2011a, Reference Drohojowska and Szwedob, Reference Drohojowska and Szwedo2013a, Reference Drohojowska, Szwedo, Azar, Engel, Jarzembowski, Krogmann, Nel and Santiago-Blayb, Reference Drohojowska and Szwedo2015; Drohojowska et al. Reference Drohojowska, Perkovsky and Szwedo2015; Szwedo & Drohojowska Reference Szwedo and Drohojowska2016), Middle Eocene Geiseltal fossil Lagerstätte (Weigelt Reference Weigelt1940). Whiteflies are also recorded in Miocene Mexican and Dominican ambers (Poinar Reference Poinar1992; Wu Reference Wu1996), and Miocene Ethiopian amber (Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Perrichot, Svojtka, Anderson, Belete, Bussert, Dörfelt, Jancke, Mohr, Mohrmann, Nascimbene, Nel, Nel, Ragazzi, Roghi, Saupe, Schmidt, Schneider, Selden and Vávra2010) and Pliocene of Germany (Rietschel Reference Rietschel1983).

Suborder Sternorrhyncha Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843

Infraorder Aleyrodomorpha Chou, Reference Chou and Cockerell1963

Superfamily Aleyrodoidea Westwood, Reference Westwood1840

Family Aleyrodidae Westwood, Reference Westwood1840

Aleyrodidae gen. and sp. indet.

1993 ‘aleyrodoid': Jarzembowski & Ross, p. 218, fig. 2.

2000a ‘pupal case of Aleyrodoidea': Shcherbakov, p. 35.

Material. Specimen No. MNEMG IB, collected by A. A. Mitchell. Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight.

Description. Fossil of pupal case, dorsal view, 0.9mm long, 0.65mm wide. Margin smooth, thoracic tracheal pore not differentiaded from the margin. Submarginal area wide, with distinct submarginal lines. Cephalothoracic suture absent. Longitudinal moulting suture not reaching margin; transverse moulting suture not reaching margin of pupal case, slightly curved anteriad, but lateral portions not distinctly bent, but gently curved at wide angle. Abdomen with intersegmental sutures distinct, not extending into subdorsum. Abdominal rhachis absent. Lateral portions of abdominal segments with eminences (subdorsal pores?, wax pores?). Vasiform orifice triangular. Operculum rounded, lingula spatulate.

Remarks. A SEM (scanning electron microscope) photograph of this specimen was figured by Jarzembowski & Ross (Reference Jarzembowski and Ross1994, fig. 2). The subfamilial and tribal placement of the specimen needs further studies. A few additional specimens, with numbers, MNEMG 2018.6.719; MNEMG 2018.6.773; MNEMG 2018.6.1478; MNEMG 2018.6.2717; MNEMG 2018.6.3060 (field numbers 719, 773, 1478, 2717 and 3060 respectively, collected by Tony Mitchell) preliminarily identified as Aleyrodidae are stored in the Maidstone Museum. One specimen was found in the collection of the NHM, London, NHMUK II.2986a, b (Pl. 2: 5–6), but only provisionally ascribed to Aleyrodidae.

The Aleyrodomorpha is a group with great taxonomic difficulties. In the Aleyrodomorpha, the taxonomy of recent forms is based on the last pre-adult instar, the so called ‘puparium', but that of the fossil forms, on winged adults (Gill Reference Gill and Gerling1990; Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov2000a; Martin Reference Martin2003). The Aleyrodidae comprises a single family including around 1550 currently valid species and subspecies names (Martin & Mound Reference Martin and Mound2007; Ouvrard & Martin Reference Ouvrard2019). Relationships between Aleyrodidae and their host plants are still unclear, and this problem was addressed by Manzari & Quicke (Reference Manzari and Quicke2006) and Dubey & Ko (Reference Dubey and Ko2006). Most studies on whitefly biology deal with plants of economic importance (Lenteren & Noldus Reference van Lenteren, Noldus and Gerling1990) and the lack of reliable behaviour and ecology data hampers the understanding of evolutionary patterns in this group. Few whitefly species are known as monophagous, most being oligo- or polyphagous. According to Mound & Halsey (Reference Mound and Halsey1978) the majority of aleyrodids are recorded only from dicotyledonous angiosperms and a smaller, but significant, number feed on monocots, particularly grasses and palms. Few present-day whiteflies feed on non-angiosperm hosts, the record of a whitefly feeding on a gymnosperm, involving the highly polyphagous Trialeurodes vaporariorum is exceptional (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Mifsud and Rapisarda2000; Manzari & Quicke Reference Manzari and Quicke2006). A few species habitually feed on ferns and other pteridophytes such as Selaginella (Mound et al. Reference Mound, Martin and Polaszek1994); these are very much exceptions to the rule (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Mifsud and Rapisarda2000). Whiteflies appear to have evolved quite a long time ago, with the oldest known fossil remains from the Late Jurassic – the extinct Bernaeinae Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov2000a surviving to the Mid-Cretaceous. The oldest Udamoselinae are recorded from Lower Cretaceous Lebanese amber (Hauterivian–Aptian), the first Aleurodicinae were found in Burmese amber (Cenomanian). No confirmed fossil record of Aleyrodinae is available at the moment (Shcherbakov Reference Shcherbakov2000a). The present-day distribution of Aleyrodidae lineages shows that Aleurodicinae are distributed mainly in the Neotropical and Australasian regions, while Aleyrodinae are distributed worldwide (Mound & Halsey Reference Mound and Halsey1978; Martin & Mound Reference Martin and Mound2007; Evans Reference Evans2008). This distributional pattern and the availability of fossil data suggest a Palaeotropical origin of the whiteflies (Mound Reference Mound1984; Bink-Moenen & Mound Reference Bink-Moenen, Mound and Gerling1990; Manzari & Quicke Reference Manzari and Quicke2006). The question of ancestral host plants of the Aleyrodidae is still open. It seems that the group evolved in relation to some Jurassic gymnosperms (or pro-angiosperms?); however, their accelerated diversification probably took place in concordance with the diversification of angiosperms and biotic reorganisation of the biosphere in the Mid-Cretaceous (Rasnitsyn Reference Rasnitsyn and Ponomarenko1988; Drohojowska & Szwedo Reference Drohojowska and Szwedo2015; Szwedo & Drohojowska Reference Szwedo and Drohojowska2016). Manzari & Quicke (Reference Manzari and Quicke2006) stated that the diversification pattern of Aleyrodidae with their host plants is obscured by widespread host switching. However, it could be said that the evolution of aleyrodid host plant affiliations appears not to be random as some groups have species feeding on related plants.

Coccids (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccidomorpha)

by Jacek Szwedo and Ewa Simon

The scarcity of scale insects among Palaeogene fossils is still a puzzle, but the number of species representing both archeococcids (Orthezioidea) and neococcids (Coccoidea) are known from fossil resins (Koteja Reference Koteja2000a, Reference Kotejab, Reference Koteja2001, Reference Koteja2004, Reference Koteja2008; Koteja & Azar Reference Koteja and Azar2008; Vea & Grimaldi Reference Vea and Grimaldi2012, Reference Vea and Grimaldi2015; Simon & Żyła Reference Simon and Żyła2015; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Xia, Wappler, Simon, Zhang, Jarzembowski and Szwedo2015). The oldest neococcids are known from Lower Cretaceous Lebanese amber, and in the Palaeogene they represent a diverse group. It would be interesting to know on which host plants ancestral and fossil scale insects fed on in various periods of geological time, and with which types of vegetation and climatic conditions they were associated. Scale insects appeared as an abundant and diversified group in the Early Cretaceous, but their roots are unknown even if the supposed time of their origin is Triassic (Koteja Reference Koteja1985, Reference Koteja2001). It is believed that the most recent periods of scale insects diversification are related to the evolution of two other groups of organisms intimately associated with coccids: angiosperm plants and ants (Koteja Reference Koteja1985; Grimaldi & Engel Reference Grimaldi and Engel2005). To test the hypothesis about scale insect phylogeny and relationships, data on their biology, host–parasite relationships, origins of gall induction, biogeography, evolution of chromosome systems and molecular characteristics (Cook et al. Reference Cook, Gullan and Trueman2002; Gullan & Cook Reference Gullan and Cook2007; Hodgson & Hardy Reference Hodgson and Hardy2013), as well as morphology-based palaeontological and neontological research and correlation of radiation events are necessary (Koteja Reference Koteja2000a, Reference Koteja2008; Koteja & Azar Reference Koteja and Azar2008; Vea & Grimaldi Reference Vea and Grimaldi2012, Reference Vea and Grimaldi2015; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Xia, Wappler, Simon, Zhang, Jarzembowski and Szwedo2015).

Suborder Sternorrhyncha Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843

Infraorder Coccidomorpha Heslop-Harrison, Reference Heslop-Harrison1952

Superfamily Coccoidea Fallén, 1814 indet.

(Pl. 3: 1)

Plate 3 (1) Coccoidea, MNEMG HL1b, male, forewing. (2) Schizoneurites brevirostris Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915, holotype, USNM 61428 part, dorsal part of body, without legs. (3) Hormaphis? longistigma Wegierek sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK I.9595. (4) Eriosoma gratshevi Wegierek sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK I.8585. Scale bar=1mm.

Material. Specimen No. MNEMG HL1a, b, Jarzembowski Collection, Maidstone Museum. Insect Limestone, Hampstead Ledge.

Description. Imago, male, lanceolate forewing, 2.15mm long, 1mm wide. Subcostal ridge curved along forewing margin, slightly sigmoidal at base, not strongly curved in apical portion.

Compression fossil scale insects (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccomorpha) were documented from the Early Cretaceous of Transbaikalia (Koteja Reference Koteja1988, Reference Koteja1989) and England (Koteja Reference Koteja1999) – representing archeococcid males (Orthezioidea: Matsucoccidae and Xylococcidae). Only adult male scale insects have wings and we cannot glean anything about insect and plant interactions because the adult males do not feed. These records provide only morphological details. However, feeding stages of females and larvae preserved on fossil dicotyledonous leaves were documented from the Middle Eocene of Messel, Germany (Wappler & Ben-Dov Reference Wappler and Ben-Dov2008), Miocene deposits of Sicily (Pampaloni Reference Pampaloni1902; Koteja & Ben-Dov Reference Koteja and Ben-Dov2003), Germany (Zeuner Reference Zeuner1938; Koteja Reference Koteja2000b), New Zealand (Harris et al. Reference Harris, Bannister and Lee2007) – representing neococcids (Coccoidea: Diaspididae) and unidentified scale insects (Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Kaulfuss, Bannister, Baranov, Beimforde, Bleile, Borkent, Busch, Conran, Engel, Harvey, Kennedy, Kerr, Kettunen, Philie Kiecksee, Lengeling, Lindqvist, Maraun, Mildenhall, Perrichot, Rikkinen, Sadowski, Seyfullah, Stebner, Szwedo, Ulbrich and Lee2018) – and India (Bera et al. Reference Bera, Mitra, Banerjee and Szwedo2006).

Aphids (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Aphidomorpha)

by Piotr Wegierek

The earliest published data on aphids from the Insect Limestone of the Isle of Wight concerned two species known from single specimens, which suggested that aphids were very rare in these strata and their taxonomic diversity was low. As a result of the present research, 25 fossils have been identified as Aphidoidea. The findings suggest a relatively high degree of taxonomic diversity (seven species representing one extinct and three extant families), comparable with Eocene/Oligocene deposits where aphids have been found (Scudder Reference Scudder1890; Heie Reference Heie1989). In the present paper aphid species formerly described from the Isle of Wight, i.e., Aphis gurnetensis Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921a, Reference Cockerellb, Reference Cockerellc and Schizoneurites brevirostris Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915 are revised, and other fossils are described for the first time.

Schizoneurites brevirostris Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915 redescribed below, is the last known representative of the extinct family Elektraphididae. In contrast to the Baltic amber fauna, most of the described species are placed within recent genera. The condition of specimens prevents a more detailed comparative analysis.

Suborder Sternorrhyncha Amyot & Audinet-Serville, Reference Amyot and Audinet-Serville1843

Infraorder Aphidomorpha Becker-Migdisova & Aizenberg, 1962

Superfamily Aphidoidea Geoffroy, 1762

Family Elektraphididae Steffan, Reference Steffan1968

Genus Schizoneurites Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915

Type species. Schizoneurites brevirostris Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915, Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight, UK; by original designation.

Remarks. This genus was redescribed by Heie (Reference Heie1970). He proposed that the genera Antiquaphis Heie, Reference Heie1967 and Elektraphis Steffan, Reference Steffan1968 should be regarded as junior synonyms and belonged to the family Elektraphididae (Heie Reference Heie1976). Steffan & Schlüter (Reference Steffan and Schlüter1981) restored the formerly synonymised genera. However, the systematic position of the genus Schizoneurites was not specified. In the original description Cockerell (Reference Cockerell1915) emphasised its similarity to the genera Schizoneura Hartig, Reference Hartig1839 or Eriosoma Leach, Reference Leach1818 of the family Eriosomatidae. The five-segmented antennae with transverse grooves, veins CuA1 and CuA2 connected basally suggest that this genus should be placed in the family Elektraphididae.

Schizoneurites brevirostris Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1915

1915 Schizoneurites brevirostris Cockerell, p. 488.

1992 Schizoneurites brevirostris: Carpenter, p. 248.

1970 Schizoneurites brevirostris: Heie, p. 114.

1976 Schizoneurites brevirostris: Heie, p. 54.

1998 Schizoneurites brevirostris: Heie & Wegierek, p. 183.

2011 Schizoneurites brevirostris: Heie & Wegierek, p. 56.

Holotype part. USNM 61428, Lacoe collection. Imprint of dorsal part of body, right antenna and fragments of legs preserved. Left fore- and hindwings visible, cubital veins on right wing distinct.

Counterpart. NHMUK I. 9850, Brodie Collection Imprint of ventral part of body, without legs. Right antenna and left forewing preserved. The counterpart was not seen for the original description.

Diagnosis. Veins CuA1 and CuA2 thick, with a common stem. Vein M undivided. Antennae five-segmented, with transverse grooves. Primary rhinaria invisible. In contrast to other representatives of this genus, the basal portion of vein M visible.

Redescription. Length of body 1.2mm. Antennae five-segmented, segment III as long as IV (0.05mm) and markedly shorter than longest segment V (about 0.06mm). Basal part of segment III narrow, apical part wide. Segment IV approximately cylindrical, segment V tapering apically. All segments of flagellum with distinct transverse grooves.

Compound eyes extend to the ventral part of head. Front coxae contiguous with clypeus. Forewings 1.3mm long. Pterostigma almost as long as the common stem of veins Sc+R+M, four times longer than wide. Cubital veins (CuA1 and CuA2) thicker than others, forming a short common stem (CuA1+2), whose length equals the width of the pterostigma. Bases of cubital veins close to the pterostigma, distanced from it by two widths of the pterostigma. Vein M distinct in the basal part, branching off from the basal part of the pterostigma, basal part of Rs invisible.

Family Hormaphididae Mordvilko, Reference Mordvilko1908

Genus Hormaphis Osten-Sacken, Reference Osten-Sacken1861

Type species. Hormaphis hamamelidis Osten-Sacken, Reference Osten-Sacken1861, recent species, by original designation.

Hormaphis? longistigma Wegierek sp. nov.

Etymology. From ‘longistigma', Latin – ‘elongated pterostigma'.

Holotype. NHMUK I.9595, Brodie Collection; Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight. Part of head, thorax, abdomen, forewings and part of antenna.

Diagnosis. Veins CuA1 and CuA2 connected basally to form a common stem. Vein M with a single fork. Pterostigma long. Antennae with annular rhinaria.

Description. Body about 1.0mm long and 0.4mm wide across abdomen. Antennae five-segmented, about 0.2mm long. Length of antennal segments in millimetres: II 0.04, III 0.06, IV 0.03-0.05, V 0.05–0.06. Last segment with annular rhinaria. Mesothoracic lobe not well developed. Forewings 1.3mm long, 0.35–0.5mm wide. Cubital veins CuA1 and CuA2 connected basally to form a common stem equal in length to vein CuA2 or half the length of CuA1. Vein M in the basal part invisible, in the apical part forked. Pterostigma thin and long, ten times longer than wide. Vein Rs s-shaped, branching off in the basal part of the pterostigma. Segment boundaries of abdomen well defined.

Remarks. Modern aphids rarely possess a common stem of CuA1 and CuA 2. Such wing venation with annular secondary rhinaria is typical for Hormaphididae. Similar branching of CuA veins is to be found in the recent European species Hormaphis betulae Mordvilko. The newly described species, contrary to the recent one, has a forked vein M and elongated pterostigma.

Family Eriosomatidae Kirkaldy, Reference Kirkaldy1905

Genus Eriosoma Leach, Reference Leach1818

Type species. Eriosoma lanigera Hausmann, Reference Hausmann1802 recent species.

Eriosoma gratshevi Wegierek sp. nov.

Figure 14 Eriosoma gratshevi Wegierek sp. nov. (A) General view, paratype NHMUK I.8712. Scale bar=0.02mm. (B) Left antenna, paratype NHMUK I.8712. Scale bar=0.05mm. (C) Part of antennal segment, holotype NHMUK I.8585. Scale bar=0.1mm. (D) Left forewing, holotype NHMUK I.8585. Scale bar=0.5mm.

Etymology. In honour of Vadim G. Gratshev, the late Russian entomologist and good friend of the author.

Holotype. NHMUK I.8585, Brodie Collection, Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight. Ventral part of head, right antenna and mesosternum. Right forewing well visible.

Paratype. NHMUK I.8712, Brodie Collection. Ventral part of body, basal portions of legs and fragments of antennae.

Diagnosis. As in recent representatives of the genus Eriosoma, antennal segment III very long, with annular rhinaria. Segments IV and V with single rhinaria, last segment only with primary rhinarium. Vein M forked. Veins CuA1 and CuA2 branch off independently. Siphunculi porous.

Description. Length of body 1.3mm. Compound eyes large, with distinct triommatidium, extending to the ventral side of head. Antennae six-segmented, 0.7mm long. Length of antennal segments in mm: I 0.05, II 0.05–0.06, III 0.29, V 0.11, VIa 0.10, VIb 0.03. Antennal segment III with many annular rhinaria, segments IV and V with single semiannular rhinaria, the last segment only with primary rhinarium. Front coxae 0.04–0.05mm long. Middle femora 0.28mm long. Forewings about 1.2mm long, 0.5mm wide. Veins CuA1 and CuA2 branch off from the common stem independently, CuA1 arcuate, CuA2 straight. Vein M close to the base of CuA1 but not reaching the common stem of Sc+R+M because its basal part is not developed; in the apical part forked. Pterostigma lenticular, four times longer that wide. Rs branching off in the middle of pterostigma. Segment boundaries of abdomen clearly marked; siphunculi porous, 0.04mm in diameter.

Genus Colopha Monell, Reference Monell1877

Type species. Byrsocrypta ulmicola Fitch, Reference Fitch1859, recent species; by original designation.

Colopha? incognita Wegierek sp. nov.

Plate 4 (1) Colopha? incognita Wegierek sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK I.9203. (2) Panfossilis anglicus Wegierek gen. et sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK I.9033. (3) Phyllaphis gurnetensis (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921b), holotype, NHMUK In.24357. (4) Betulaphis kozlovi Wegierek sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK I.9411.

Figure 15 Colopha? incognita Wegierek sp. nov. (A) Paratype, NHMUK In.24837, forewing and hindwing. (B) Holotype, NHMUK I.9203, right forewing. Scale bar=0.5mm.

Etymology. From ‘incognitus', Latin – ‘unrecognisable.'

Holotype. NHMUK I.9203 (Fig. 15B), Brodie Collection, Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight. Ventral side of body without abdomen, right forewing preserved.

Paratypes. NHMUK I.8662, Brodie Collection – forewings and hindwing; In.17178, Smith Collection – forewings; In.17198, Smith Collection – head with parts of antenna and fragments of dorsal part of thorax; In.24837 (Fig. 15A), Hooley Collection – thorax and side of head, forewings and hindwing.

Diagnosis. Vein Rs branches off approximately in the middle of pterostigma, the fork shifted towards its base. M with a single fork, hindwings with a single vein.

Description. Forewing 1.7–2.0mm long, 0.7–0.8mm wide. Pterostigma 4.5–5.5 times longer than wide, in the apical part pointed, in the basal part broadening rapidly. Vein Rs branches off approximately in the middle of pterostigma, the fork shifted towards its basal part. Vein M separates from the common stem Sc+R+M in the midpoint between the base of pterostigma and the base of vein CuA1, with a single fork. The common stem of M as long as M3+4. Veins CuA1 and CuA2 leave the common stem independently, almost parallel, CuA1 slightly arcuate. Hindwings 1.1mm long with a single vein.

Remarks. The preserved forewings resemble those in several genera of the subfamily Eriosomatinae (sensu Heie Reference Heie1980). However, the set of characters – with vein M forked, the unique shape of the basal part of the pterostigma and hindwings with a single vein – seems closest to the genus Colopha.

Family Drepanosiphidae Herrich-Schäffer in Koch, Reference Koch1857

Genus Panfossilis Wegierek gen. nov.

Etymology. The name of a recent genus Panaphis Kirkaldy, Reference Kirkaldy1904, to which it bears resemblance, and Latin fossilis, ‘fossil'.

Type species. Panfossilis anglicus sp. nov.; here designated.

Diagnosis. Circular rhinaria only on segment III, terminal process as long as the width of segment IVa at base. Pterostigma short, vein Rs short, bases of veins CuA1 and CuA2 wide apart.

Description. Antennae six-segmented; segment III with many circular secondary rhinaria along the whole segment. Other segments of flagellum without secondary rhinaria, with rows of small transverse depressions, which may be remnants of delicate spinules. Terminal process very short, blunt, as long as the width of segment VI at base. Pterostigma short and wide. Vein Rs short, arcuate, in the middle invisible. Veins CuA1 and CuA2 branch off independently, their bases wide apart.

Panfossilis anglicus Wegierek sp. nov.

Figure 16 Panfossilis anglicus gen. and sp. nov. (A) Holotype, NHMUK I.9033, part of antenna. Scale bar=0.1mm. (B) General view. Scale bar=0.5mm. (C) Paratype, NHMUK I. 8661, left antenna. Scale bar=0.1mm.

Etymology. From ‘Anglia' – the Polish name for England, part of Great Britain.

Holotype. NHMUK I.9033, Brodie Collection, Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight. Head with part of antenna, thorax in dorsal view, right forewing and base of left forewing.

Paratype. NHMUK I.8661, Brodie Collection Ventral side of body, whole left antenna preserved.

Diagnosis. As for genus as it is the only included species.

Description. Length of body 1.4mm. Compound eyes situated at sides of head. Antennal segment III shorter than the total length of other segments of flagellum. Length of antennal segments in millimetres: I 0.05–0.08, II 0.07, III 0.33, IV 0.15, V 0.15, VIa 0.13, VIb 0.02. Diameter of secondary rhinaria approximately as long as half the width of antennal segment III. Middle femora 0.32mm long, hind coxae 0.09mm long, hind femora 0.38mm long. Pterostigma three times longer than wide. Base of vein Rs shifted beyond the midpoint of the pterostigma towards the apex.

Bases of veins CuA1 and CuA2 wide apart. The distance between the bases of veins M and CuA1 equals the distance between the bases of cubital veins.

Genus Phyllaphis Koch, Reference Koch1856

Type species. Chermes fagi Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1761, recent species; by original monotypy.

Phyllaphis gurnetensis (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921b) comb. nov.

Figure 17 Phyllaphis gurnetensis (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921b). (A) Holotype NHMUK In. A 24357, forewing. Scale bar=0.5mm. (B) Part of antennal segment, NHMUK I.8512. Scale bar=0.02mm. (C) Forewing and hindwing, NHMUK I.8512. Scale bar=0.5mm. (D) NHMUK I.9098, forewing and hindwing. Scale bar=1mm.

1921 Aphis gurnetensis Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921b, p. 476, fig. 43.

1962 Aphis gurnetensis: Becker-Migdisova & Aizenberg, p. 198, fig. 577.

1967 Aphis gurnetensis: Heie, p. 13.

1991 Aphis gurnetensis: Becker-Migdisova & Aizenberg, p. 273, fig. 577.

1998 Aphis gurnetensis: Heie & Wegierek, p. 164.

Holotype. NHMUK In.24357 (H 1124) (Fig. 17A), Hooley Collection, Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight. Forewing.

Additional material. NHMUK I.8512 (Fig. 17B, C), Brodie Collection – distorted body, poorly preserved antenna, creased forewings and hindwings; I.9098 (Fig. 17D), Brodie Collection – part of thorax and abdomen in dorsal view, right forewing and hindwing.

Diagnosis. Antennal segment III with circular secondary rhinaria arranged in a single row. Pterostigma lenticular, vein Rs arcuate, vein M with two forks, M1 approximately as long as M1+2. Cubital veins branch off independently, not far away from each other. Hindwings with two veins, their bases close together.

Description. Antennal segment III with circular secondary rhinaria located along the lower margin, their diameter as long as 1/3 of the segment width. Forewings 2.5–3.8mm long and 1.0–1.5mm wide. Pterostigma lenticular. Vein Rs arcuate, branching off in the middle of pterostigma. Vein M with two forks, the common stem of M approximately as long as M3+4. M1 as long as or only slightly shorter that M1+2. Veins CuA1 and CuA2 branch off independently from the common stem, distance between their bases as long as or slightly shorter than the width of pterostigma. CuA2 straight, CuA1 slightly arcuate. Hindwings about 2.1mm long, with two transverse veins located in the middle part of the wing, distance between their bases shorter than the width of pterostigma on forewing.

Remark. Becker-Migdisova & Aizenberg (1962, 1991) erroneously listed this species as originating from ‘Oligocene, North America'. The species has been placed within the genus Phyllaphis on the basis of fore and hindwing structure and venation as well as on a highly characteristic shape of secondary rhinaria and their arrangement on antennal segment III.

Genus Betulaphis Glendenning, Reference Glendenning1926

Type species. Betulaphis occidentalis Glendenning, Reference Glendenning1926, recent species; by original designation.

Betulaphis kozlovi Wegierek sp. nov.

Figure 18 Betulaphis kozlovi Wegierek sp. nov. (A) Forewing and hindwing, paratype, NHMUK In.24499. Scale bar=1mm. (B) Part of antennal segment, holotype, NHMUK I.9411. Scale bar=0.1mm. (C) Forewing, holotype, NHMUK I.9411. Scale bar=0.5mm.

Etymology. In honour of the late Mikhail A. Kozlov, renowned Russian entomologist.

Holotype. NHMUK I.9411 (Fig. 18B, C), Brodie Collection, Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight. Head with part of antenna, dorsal side of thorax, fragment of front femur and tibia. Basal part of right forewing and creased left wing.

Paratype. NHMUK In.24499 (Fig. 18A). Forewing and hindwing.

Diagnosis. Antennal segment III with few semiannular rhinaria arranged in a single row. Pterostigma lenticular, vein Rs arcuate. Vein M with two forks, the common stem of M short, veins M1 and M2 very short. Veins CuA1 and CuA2 leave the common stem independently. Hindwings with two transverse veins.

Description. Compound eyes situated at sides of the head. Legs and antennae with rows of small transverse depressions, which may be remnants of delicate spinules. Antennal segment III with semiannular rhinaria arranged ventrally in a single row at a distance of at least the width of the segment from each other. Forewings 3.4mm long and 1.2mm wide. Pterostigma thin, lance-shaped, pointed, four to five times longer than wide. Vein Rs arcuate, branching off in the middle of the pterostigma, with the base shifted towards its basal portion. Base of vein M in the middle of the distance between the bases of CuA1 and Rs. Vein M with two forks. The common stem of M1+2+3+4 short, half the length of M3+4. Veins M1 (shorter than half the length of M1+2) and M2 (shorter than 1/3 the length of M1+2) very short. Veins CuA1 and CuA2 branch off from the common stem independently, their bases at the distance of the width of pterostigma from each other. Hindwings with two transverse veins.

Aphidoidea incertae sedis

Material. NHMUK I.9304, I.9596, I.9700, I.9943, I.10210, Brodie Collection; In.17198, In.17210 (2, 3) (with paratype of Aeolothrips jarzembowskii Shmakov, Reference Shmakov2014), In.17214, A'Court Smith Collection; In.24625, Hooley Collection; II.2766a, b, II.2861, II.2862, II.3028 [det. J. Szwedo]. Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight.

Discussion. Most of the described aphid fauna was probably associated with arborescent angiosperm plants or angiosperm shrubs, mainly of the families Fagaceae, Betulaceae, Ulmaceae, Juglandaceae and Lauraceae. Representatives of the family Eriosomatidae might have migrated onto secondary hosts of Asteraceae (Compositae), Cyperaceae or Poaceae (Graminae). Today a group of species of the family Hormaphididae is also associated with Poaceae (especially Bambuseae) or Palmaceae. It is possible that Elektraphididae, like recent Adelgidae, were associated with Pinaceae.

Planthoppers, froghoppers, singing cicadas, leafhoppers (Hemiptera: Fulgoromorpha & Cicadomorpha)

by Jacek Szwedo

The Fulgoromorpha comprises one of the most ancient lineages of the Hemiptera, and in the fossil record planthoppers have been known since the Early Permian (Szwedo et al. Reference Szwedo2004; Szwedo Reference Szwedo2018). The earliest Fulgoromorpha are placed in the Permian superfamily Coleoscytoidea Martynov, Reference Martynov1935; the second group is the Permian–Triassic Surijokocixioidea Shcherbakov, Reference Shcherbakov2000b and the Fulgoroidea have been known since the Jurassic.

Several fossil Fulgoroidea have been reported so far from the latest Eocene Bembridge Marls of the Isle of Wight. The first descriptions were by Cockerell (Reference Cockerell1921b), who described Poekilloptera melanospila Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1921b (transferred to Orthoptera, see Nel et al. Reference Nel, Prokop and Ross2008). Later, more species were added under the names Hastites muiri Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1922, Hooleya indecisa Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1922 and Myndus wilmattae Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1926. These taxa are discussed below.

Cicadomorpha is the second suborder formerly placed together with Fulgoromorpha as ‘Auchenorrhyncha', but not related directly to planthoppers (Bourgoin & Campbell Reference Bourgoin and Campbell2002; Szwedo Reference Szwedo2002, Reference Szwedo2018; Szwedo et al. Reference Szwedo, Bourgoin and Lefebvre2004). Cicadomorpha comprises ancient lineages, some of them extinct (Dysmorphoptiloidea Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906 (in 1906–8), Hylicelloidea Evans, Reference Evans1956, Palaeontinoidea Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906, Pereborioidea Zalessky, Reference Zalessky1930, Prosboloidea Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906 and Prosbolopseoidea Becker-Migdisova, Reference Becker-Migdisova1946). The placement of the paraphyletic Scytinopteroidea Handlirsch, Reference Handlirsch1906 – forms ancestral to Coleorrhyncha Myers & China, Reference Myers1929 and Heteroptera (Shcherbakov & Popov Reference Shcherbakov, Popov, Rasnitsyn and Quicke2002) – remains unresolved, but close to Cicadomorpha (Shcherbakov & Popov Reference Shcherbakov, Popov, Rasnitsyn and Quicke2002; Szwedo et al. Reference Szwedo, Bourgoin and Lefebvre2004; Szwedo Reference Szwedo2018). Only representatives of the superfamilies Cercopoidea, Cicadoidea and Cicadelloidea (together with the extinct Hylicelloidea Evans, Reference Evans1956, extant Myerslopioidea Evans, Reference Evans1957 and Membracoidea Rafinesque, Reference Rafinesque1815 forming the clade Clypeata Qadri, Reference Qadri1967) are reported here. Only a single representative of Cicadomorpha from the Bembridge Marls has been reported so far, named Aphrophora woodwardi Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1922.

The venation interpretations of Fulgoromorpha follow Szwedo & Żyła (Reference Szwedo and Żyła2009) and Bourgoin et al. (Reference Bourgoin, Wang, Asche, Hoch, Soulier-Perkins, Stroiński, Yap and Szwedo2015), and for Cicadomorpha follow interpretations of Emeljanov (Reference Emeljanov1987), Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Zhang and Szwedo2009) and Nel et al. (Reference Nel, Roques, Nel, Prokin, Bourgoin, Prokop, Szwedo, Azar, Desutter-Grandcolas, Wappler, Garrouste, Coty, Huang, Engel and Kirejtshuk2013).

Suborder Fulgoromorpha Evans, Reference Evans1946

Superfamily Fulgoroidea Latreille, Reference Latreille1807

Family Cixiidae Spinola, Reference Spinola1839

Subfamily Bothriocerinae Muir, Reference Muir1923

Genus Klugga Szwedo gen. nov.

Etymology. Name is derived from Proto-Celtic word ‘klugga' meaning ‘stone'. Gender: feminine.

Type species. Klugga gnawa sp. nov., here designated.

Diagnosis. Tegmen with venation similar to Bothriobaltia Szwedo, Reference Szwedo2002, but differs in having a larger stigma (stigma elongate and narrow in Bothriobaltia); wider basal cell (basal cell narrow and elongate in Bothriobaltia); shorter common stem ScP+R (common stem longer, reaching level of claval veins junction in Bothriobaltia); branching of vein ScP+RA1 slightly basad of forking of vein CuA (forking of ScP+RA1 slightly apicad of CuA forking in Bothriobaltia).

Description. Tegmen with costal margin slightly curved at base, striations on costal and apical margins distinct. Stigma distinct, about twice as long as wide, with corrugated texture. Basal cell about twice as long as wide. Stems of veins ScP+R, MP and CuA leaving basal cell independently; stem ScP+R leaving basal cell slightly basad of stem M; branch ScP+RA branched slightly basad of forking of stem CuA, terminal ScP+RA1 distinctly curved anteriad, widened in apical portion; vein RP forked at same level as forking of anterior branch of vein MP, with three terminals; stem M forked at level of nodal line, anterior branch forked again at level of RP branching, and again at level of posterior branch of vein MP forking, vein MP with five terminals; stem CuA forked slightly posteriad of ScP+RA branching, posteriad of claval veins junction. Nodal line distinct, veinlet rp-mp oblique, veinlet mp-cua more or less oblique. Clavus short with apex reaching nearly half of tegmen length; claval veins Pcu and A1 fused at about half of clavus length.

Klugga gnawa Szwedo sp. nov.

Plate 5 (1) Klugga gnawa Szwedo gen. et sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK In.24513, tegmen. (2–3) Klugga regoa Szwedo gen. et sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK In.24512: (2) tegmen; (3) SEM photo of stigma area. (4–7) Liwakka gelloa Szwedo gen. et sp. nov.: (4) holotype, NHMUK In.26034, tegmen; (5) SEM photo of the paratype NHMUK In.25457, tegmen; (6) SEM photo of stigmal area; (7) SEM photo of stigmal area sensory pores. Scale bars=1mm for 1, 2 and 4.

Figures 19–26 (19–24) Tegmen: (19) Klugga gnawa, Szwedo gen. et sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK In.24513; (20) Klugga regoa Szwedo gen. et sp. nov., holotype NHMUK In.24512; (21) Liwakka gelloa Szwedo, gen et sp. nov., holotype NHMUK In.26034; (22) Liwakka gelloa Szwedo, gen et sp. nov., paratype NHMUK In.25457; (23) Delwa morikwa Szwedo gen. et sp. nov., holotype NHMUK I.8657; (24) Kommanosyne wrikkua Szwedo gen. et sp. nov., holotype NHMUK In.24521. (25) Kernastirdius nephlajeus Szwedo gen. et sp. nov., holotype NHMUK I.9023, anterior part of body, parts of tegmina and hindwing. (26) Kernastirdius? sp., NHMUK In.25480, tegmen. Scale bar=1mm.

Etymology. Specific epithet is derived from Proto-Celtic word ‘gnawo' meaning ‘clear'.

Holotype. NHMUK In.24513; Hooley Collection, Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight. Tegmen with missing clavus and coloration partly preserved.

Diagnosis. Nodal veinlet m-cu not distinctly oblique; apical line of veinlets indistinct; cell C5 about as long as stigma; median portion of tegmen with darker, transverse, wide band.

Description. Length of tegmen 4.05mm, width at widest point 2.05mm. Basal and apical portion not coloured, median 1/3 of tegmen with darker transverse, wide band, with lighter portion mediad of stigma to anterior branch of vein M. Veins slightly darker.

Klugga regoa Szwedo sp. nov.

Etymology. Specific epithet is derived from Proto-Celtic word ‘rego' meaning ‘band'.

Holotype. NHMUK In.24512; Hooley Collection, Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight. Impression of median portion of tegmen.

Diagnosis. Nodal veinlet m-cu distinctly oblique; apical line of veinlets distinct; apical veinlet m-cu oblique; cell C5 slightly longer than stigma; tegmen with slightly darker, narrow band at level of nodal line, passing to apex of clavus, darker band at level of apical veinlets.

Description. Length of preserved portion of tegmen 2.75mm, width at widest point 1.9mm. Tegmen with veins slightly darkened, two slightly darker transverse bands, first at level of nodal line and second at level of apical line of veinlets.

Genus Liwakka Szwedo gen. nov.

Etymology. Name is derived from Proto-Celtic word ‘liwakk' meaning ‘stone'. Gender: feminine.

Type species. Liwakka gelloa sp. nov.; here designated.

Diagnosis. Venation similar to Klugga gen. nov., but differs in branching of vein ScP+RA slightly posteriad of vein CuA forking (branching of vein ScP+RA slightly anteriad of CuA forking in Klugga); claval veins Pcu and A1 fused at level of CuA forking (claval veins fused basad of CuA forking in Klugga); differs from Bothriobaltia Szwedo, Reference Szwedo2002 by shorter stem ScP+R (stem ScP+R longer in Bothriobaltia); bigger stigma (stigma narrow and elongate in Bothriobaltia).

Description. Costal margin slightly curved at base, costal and apical margin with distinct striations. Stigma about twice as long as wide, with corrugated texture. Basal cell twice as long as wide. Stems of veins ScP+R, MP and CuA leaving basal cell independently; stem ScP+R leaving basal cell slightly basad of stem MP; branch ScP+RA1 branched slightly apicad of forking of stem CuA, distinctly curved anteriad; vein RP forked at same level as forking of anterior branch of vein MP, with three terminals; stem MP forked at level of nodal line, anterior branch forked again at level of RP branching, and again at level of posterior branch of vein MP forking, vein MP with five terminals; stem CuA forked slightly basad of ScP+RA1 branching, at level of claval veins junction. Nodal line distinct, veinlet rp-mp oblique, veinlet mp-cua short, straight, parallel to veinlet icu. Clavus short with apex reaching half of tegmen length; claval veins Pcu and A1 fused apicad of half of clavus length.

Liwakka gelloa Szwedo sp. nov.

Etymology. Specific epithet is derived from the Proto-Celtic word ‘gello' meaning ‘yellow, brown'; it refers to the coloration of the specimen.

Holotype. NHMUK In.26034 (Pl. 5: 4; Fig. 21); Hooley Collection, Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight. Tegmen, with part of clavus missing.

Paratype. NHMUK In.24547 (Plate 5: 5–7; Fig. 22); Hooley Collection. Tegmen with basal and claval portion not preserved.

Diagnosis. Nodal line very distinct, veinlets mp-cua and both veinlets icu straight, subparallel. Wide, transverse, brown band at level of nodal line, second wide, transverse, brown band in subapical portion of tegmen; clavus pigmented; veins darkened, brown.

Description. Length of tegmen 3.75mm, width at widest point 1.9mm. Wide, transverse, brown band at nodal line arcuate apicad, wide, transverse, brown band in subapical portion not arcuate; clavus brown.

Genus Delwa Szwedo gen. nov.

Etymology. Name from the Proto-Celtic word ‘delwa' meaning ‘form'. Gender: feminine.

Type species. Delwa morikwa sp. nov.; here designated.

Diagnosis. Similar to Liwakka gen. nov., but differs by more basad forking of anterior branch of MP; longer common stem of veins ScP+R, longer than arculus (in Liwakka and Klugga common stem ScP+R about as long as arculus).

Description. Costal margin merely curved, costal and apical margins with distinct striations. Stigma distinct, about twice as wide as long. Basal cell about 2.5 times as long as wide. Stems of veins ScP+R, MP and CuA leaving basal call independently; stem ScP+R leaving basal cell slightly basad of stem MP; common stem of vein ScP+R about three times as long as arculus; branch ScP+RA1 branched slightly apicad of forking of stem CuA, distinctly curved anteriad; vein RP forked about at same level as forking of anterior branch of vein MP, with three terminals; stem MP forked at level of nodal line, anterior branch forked again at level of first RP branching, and again apicad of posterior branch of vein MP forking, vein MP with five terminals; stem CuA forked slightly basad of ScP+RA1 branching. Nodal line distinct, veinlet rp-mp oblique, veinlet mp-cua straight, parallel to veinlet icu. Clavus short, with apex reaching half of tegmen length.

Delwa morikwa Szwedo sp. nov.

Plate 6 (1–2) Delwa morikwa Szwedo gen. et sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK I.8657: (1) tegmen; (2) SEM photo of stigmal area sensory pores. (3) Kommanosyne wrikkua Szwedo gen. et sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK In.24521, tegmen. (4) Kernastiridius nephlajeus Szwedo sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK I.9023, anterior part of body, parts of tegmina and wings. (5) Margaxius angosus Szwedo sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK In.24620, tegmen with clavus missing. (6) Dweivera reikea Szwedo gen. et sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK I.10375, tegmen, counterpart. (7) Samaliverus bikkanus Szwedo gen. et sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK I.9199(2), tegmen. (8) Langsmaniko marous Szwedo gen. et sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK In. 25286(1), tegmen. (9) Komsitija tuberculata Szwedo gen. et sp. nov., holotype, NHMUK Pl II 2999, tegmen.

Etymology. Specific epithet is derived from Proto-Celtic word ‘morikwa' meaning ‘sea-shore'.

Holotype. NHMUK I.8657; Brodie Collection, Insect Limestone, NW Isle of Wight. Tegmen, with clavus missing.

Diagnosis. Tegmen twice as long as wide at widest point; cell C5 two times as long as stigma; nodal line distinct; stem MP thickened, branch MP3+4 at nodal line thickened; apex of clavus reaching half of tegmen length.