In the afternoon of Friday, 21 May 1604, four men walked purposefully down the streets of Toledo. Heading towards the cathedral, they were awaited for Vespers by the chapter canons, who had organised a competition to fill the post of choirmaster, a position vacant since Alonso Lobo had left for the cathedral of Seville. They would soon explain the nature of the contest meant to help them decide between the candidates. All four men had travelled far to come to Toledo. Francisco de Bustamante came from Coria and Juan Siscar from Valladolid. Diego de Bruceña and Lucas Tercero, who must have spent at least a few days on the road, travelled even further from their hometowns of Burgos and León. Although none of these men was in need of a job, as they all held positions as choirmasters of reputable cathedrals, they were attracted by the prestige of the post, which before Alonso Lobo had been filled most notably by Cristóbal de Morales and Andrés de Torrentes. According to Cardinal Martínez Silíceo, ‘it is a well-known and verified fact that the Cathedral of Toledo is the most illustrious, the richest, the most splendid, the best staffed, and the most completely staffed, of any in all the Spanish dominions. Except St. Peter's in Rome, in fact, there is no cathedral in Christendom to surpass it.’Footnote 1

Thanks to the care and attention to detail of the copyist who transcribed the chapter meeting's decisions, we know even to this day the details of the tests undergone by these four candidates. This document not only serves as a fascinating witness to the concrete realities of musical life at the end of the Renaissance; it also informs us about the abilities that were expected of a musician at the height of his profession.Footnote 2 It also remarkably contradicts our previous understanding of how such contests were organised. According to Robert Stevenson, the candidates eager to become Toledo Cathedral's next choirmaster during Cristóbal de Morales's era had to compose three-, four-, and five-part works based on plainchant melodies that were given to them. From other texts that they were given, these candidates were also asked to write a fabordón and a motet, in addition to an Asperges me for double choir.Footnote 3

This series of compositional tests does not correspond with the information regarding the process detailed in the minutes of 1604. This contradiction is problematic, unless we consider the variety of preferred compositional styles imposed during Alonso Lobo's era as somehow less expansive than during Morales's. Having arrived at the cathedral for Vespers, the four candidates all found themselves confronted with the same musical themes, from which they were asked to compose a motet and a villancico in twenty-four hours. Three days later these compositions would be sung in public by members of the chapel.Footnote 4 According to the rest of the minutes, however, it seems that this written test was not conclusive. In fact, the document in question details a series of twenty practical tests that the candidates underwent in the presence of the chapel choir, in order to ascertain their choral conducting skills (‘regir el fasistor en el coro y llevar el compas’) (see Appendix).

Modern readers may be surprised to discover that this document clearly establishes contrapunto as the most important musical ability required (the first fifteen tests focus on improvised counterpoint), and even more astonished by the complexity of the tests that were to be performed extempore. While a few of them match our notions of what improvised counterpoint during the Renaissance consisted of, namely spontaneously adding a voice to a plainchant or mensural melody (the first part of exercises nos. 1, 2, 3, and exercise no. 12 in triple metre), other tests, such as adding a vocal part to a duo, trio or even a quartet (no. 4), seem almost impossible without being given ample time to meticulously study the score. How were they able to produce a musically coherent result without a score in hand? In addition, while contemporary writings that document these practices make reference to some of the exercises in question, notably those dedicated to canons (nos. 14 and 15), they also reveal that the Toledo exams were far more demanding and restrictive than the examples given by music theorists because these tests not only imposed improvisation against a mensural melody (no. 14) but also demanded that candidates be able to improvise a canon at the interval of second below a cantus firmus sung by the soprano (no. 15).Footnote 5

Some of the tests imposed on these candidates clearly challenge our modern notions of Renaissance polyphonic creation. Was it truly possible to improvise a line on a plainchant melody (or even more inconceivable, on a mensural melody), while at the same time using the Guidonian hand to show one, or at times two, singers which notes to sing, thus adding a third and fourth voice? It is not only the ability to simultaneously add three voices to a given melody (previously thought of as a strictly compositional practice incompatible with the necessary time restraints of counterpoint extempore) that challenges our modern conception of Renaissance polyphony. Indeed, if we consider the sheer number of times this exercise appears and the eminent place it holds in the trials, the case can even be made that this practice was in fact commonplace.Footnote 6

Although no one can claim that one document can be singlehandedly responsible for shattering the musicological foundations on which our modern conceptions of Renaissance music are based, it is true that finding a place for this document in the standard narratives of musical history is problematic. A large majority of us think of a sixteenth-century choirmaster as a composer who directs a choir performing his own works as well as the works of others. While the Toledo contest partly confirms this opinion (nos. 16–20), it also draws our attention to its expectations of virtuosity in improvised counterpoint. It is of course a well-established fact that contrapunto was an important skill for any professional musician. Together with training in mensural music, it represented, after chant, the second step towards the mastery of musical practice. All of the treatises written from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century that offer a complete musica practica curriculum start with plainchant, then move on to mensural music and counterpoint in an interchangeable order, and eventually finish with composition, at least from the sixteenth century on.Footnote 7 This pedagogical progression has been considered by historians as a gradus ad Parnassum, in which counterpoint is regarded as a necessary prerequisite training for studying the art of composition. Until now, all the written documents that describe contrapunto technique only vaguely account for the precise methods involved. This has ultimately kept us from considering oral counterpoint as a sophisticated discipline. Not only do we not know how these techniques were taught, but more importantly, we have no idea what the aesthetic results of these techniques sounded like in the context of a musical performance. Although written sources exist explaining primary contrapuntal techniques, none of them is detailed enough for us fully to understand the nature of the fifteen exercises found in the Toledo contest.

Fifty years ago, Ernst Ferand tried to arouse the musicological community's interest in sources that document improvised counterpoint by writing an article that to this day is our most complete summary of the subject.Footnote 8 For Ferand, a treatise published in Rome in 1553 by a Portuguese musician holds a particularly important place among the sources that have survived: Vicente Lusitano's Introdutione facilissima & novissima di canto fermo, figurato, contraponto semplice & in concerto, con regole generali per far fughe differenti sopra'il canto fermo a 2, 3 & 4 voci & compositioni, proportioni, generi, s. diatonico, cromatico, & enarmonico. Despite its ambitious title, which promises to address every aspect of musica practica, this work is in fact an introdutione that does not enter into specific details in its forty pages. Even though Lusitano's essay contains interesting remarks about mental contrapuntal techniques, it still fails to give us a sufficient understanding of how the Toledo tests were tackled. We are therefore in need of a detailed text, one that can give its readers the tools necessary to understand such complicated exercises. This text exists, and although it has not been the object of any academic study to date, we cannot attribute this fact to its inaccessibility. Since a diplomatic edition was published in 1913, this treatise has been quite widely available, but it was not until its author was identified in 1962, however, that this otherwise anonymous Spanish text began to find its place in the musicological literature. Curiously enough, the attribution of this treatise to Lusitano, the author of the Introdutione, did not spark much interest in scholars, who are still widely unaware of its existence today. In this article I wish to fill this lacuna by providing a description of this manuscript and a discussion of its contents. The section dedicated to contrapunto, which contains over 200 music examples and serves as the most thorough document we have on this subject, will be at the centre of this study, and will allow us to address the even lesser-known subject of the oral tradition of sixteenth-century art music.

VICENTE LUSITANO'S ‘TRATTATO GRANDE DI MUSICA PRATICA’

As a whole, the manuscript Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France (hereafter BnF), Esp. 219 is a complex document; thorough study has not yet solved numerous problems, especially those relating to its history and to the various stages of writing. This in-quarto book is composed of eighty-five sheets measuring 280 × 205 mm, held together by a fine red morocco binding embossed with the seal of the French Royal Library. The manuscript entered the Royal Library before 1682, the year in which Nicolas Clément described it in his Catalogus Librorum manuscriptorum Bibliotecae Regiae: ‘Carc. 15—7817 Livre d’orgue en espagnol'.Footnote 9 Since Clément cites an older shelfmark, we are able to trace the manuscript's history back to its origin. The treatise came from the private library of Pierre de Carcavy (1603–84), a bibliophile originally from Toulouse who became curator of the king's library in 1663 thanks to his experience managing Colbert's collection. Going back even further in time, a signature found at the bottom of the first page tells us who had the manuscript in his possession before it was added to Carcavy's collection. The autograph is that of the famous poet and book collector Philippe Desportes (1546–1606), who, nearing the end of his life, started signing his name in this form on his books from 1595 on.Footnote 10 Following his death, Desportes's brother Thibaut inherited all the books in his collection, with the exception of the theological works. The books were then scattered after his death by his nephew Robert Tulloue around 1631.Footnote 11 It is undoubtedly around this date that Carcavy acquired the musical treatise now held in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

We owe the modern rediscovery of the manuscript to the remarkable Francisco Asenjo Barbieri who, at the end of the nineteenth century, spent most of his time gathering documents to enrich the history of Renaissance music in Spain. In an article published in 1882, he mentions the manuscript by describing a Spanish treatise held in Paris that includes the combination of a Spanish popular song and a Kyrie from a sixteenth-century mass.Footnote 12 A letter written in 1889 by Felipe Pedrell shows that he knew Barbieri's article; he later informed his friend Henri Collet (1885–1951) about the manuscript. Collet is a composer and musicologist known today for having been one of the most important Spanish music supporters in France at the beginning of the twentieth century.Footnote 13 He spent more than ten years in Spain, where he befriended the composers Enrique Granados and Joaquín Rodrigo and became intensely interested in the Renaissance. His doctoral thesis in literature, which he defended when he returned from Spain in 1913, is entitled Le mysticisme musical espagnol au XVIe siècle and is accompanied by a second work, a ‘complementary thesis’, written in Spanish, which is a diplomatic transcription and commentary of manuscript Esp. 219. Despite the fact that this complementary thesis was published immediately after its defence, thus making it accessible, it remained completely unknown to musicologists for another half century.Footnote 14

It was not until 1962 that the situation noticeably changed, thanks to Robert Stevenson's discovery of its author, who until that time was unknown.Footnote 15 Stevenson attributed the manuscript to Lusitano first by noting the particularities of the Spanish spelling, in which traces of Portuguese can be found (consonamcia, arismetica, pequenho).Footnote 16 He then drew attention to a reference to the Pantheon, which led him to believe that the author had spent time in Rome. Most importantly, however, Stevenson noted that the manuscript's music examples used the same cantus firmus that can be found in Lusitano's treatise published in 1553, and that some of these examples were in fact identical.Footnote 17 Thanks to this discovery, the manuscript could have become an important object of study, especially for those interested in the debate that opposed Nicola Vicentino and Lusitano. Oddly enough, this treatise has only been briefly referenced in academic literature since Stevenson's discovery, and so the following fifty-year-old quote still rings true today: ‘The analysis of Lusitano's Spanish treatise, if it be his, must await another occasion.’Footnote 18

Before proposing a first approach to studying the manuscript's section dedicated to counterpoint, it may be useful to strengthen Stevenson's argument as to the authorship of the treatise by Lusitano through a detailed look at the original source. As a matter of fact, a study of the manuscript shows that the paper used is of Italian origin. Some of the four watermarks identified are known to come from Rome and Naples sometime between 1530 and 1560.Footnote 19 We can thus conclude that Lusitano was already in Italy when he began writing his treatise. In addition to the Lusitanisms pointed out by Stevenson, we can find a number of Italianisms in his Spanish, such as the terms canto fermo (fols. 9v, 10 and 20), parlar (fol. 57v) and capitolo (fol. 48v, 57v).Footnote 20

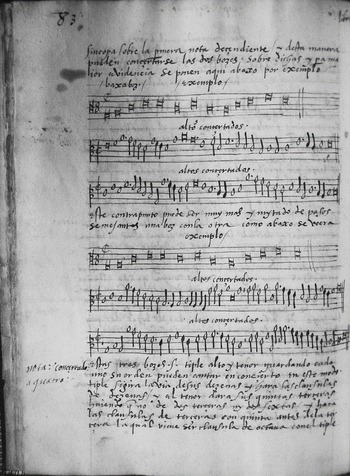

A careful analysis of the ink colour and handwriting also enable us to identify the successive stages of his drafts. The copyist began writing the treatise with great care. The text and musical examples were copied onto the pages with the help of a tabula ad rigandum, which allowed him to define the margins and to draw straight lines using a black lead (see Figure 1).Footnote 21 The work was not copied all at once, but was put together over a rather long period of time. In fact, the handwriting found in the initial draft evolves as the pages turn, particularly from fol. 43 (Figure 2) onwards, where the ductus becomes wider and more slanting, evoking a certain Italian aesthetic which could be explained by an interruption of the copying process.Footnote 22 The pages that follow show that these two apparently distinct handwritings progressively come together, creating an intermediary writing style that clearly belongs to the same copyist. Thus, much of the editing done subsequent to the initial drafting phase – including the addition of titles found at the top of the pages, headings and marginal glosses, captions, and even changes within sentences, adding a word, or replacing one word with another, all credited to the ‘second hand’ – were in fact done by the same copyist. These emendations to the original text – in which there were as many additions as deletions (several passages are crossed out, as in fols. 18, 58, 60v) – were made repeatedly, as indicated by the different colours of ink, the varying thickness of the stroke, and inconsistent written forms.

Figure 1 Paris, BnF Esp. 219, fol. 41v. Reproduced by permission of the BnF

Figure 2 Paris, BnF Esp. 219, fol. 43. Reproduced by permission of the BnF

The very end of the treatise bears evidence that identifies this singular copyist, who must necessarily be Lusitano himself. At the beginning of chapter 7 of the third book starting at the bottom of fol. 80v, which deals with the question of the diatonic, chromatic and enharmonic genera, we can find a line that has been crossed out and rewritten. The following page, which was undoubtedly the last page of the first draft, has been torn out. Radically different in appearance from the rest of the treatise, the following three folios (fols. 81–4) were added later as substitutes for the last page of the first draft. They were hastily written on unruled paper, and the non-rectilinear writing, and the lack of margins and paragraph divisions seem to indicate a sense of urgency that must have been due to the proximity of the debate with Nicola Vicentino. The last page serves as a post scriptum, and is symptomatically entitled ‘errores grandissimos’. Lusitano blames these errors on ‘alguno o algunos’, who, although not explicitly named, are most likely Vicentino and his supporters.

It is thus possible to date the first stage of the writing process to the period between Lusitano's arrival in Italy and June 1551.Footnote 23 The last three pages were certainly written after the dispute, and as for the different corrections, they might have been made in various stages both before and after 1551.Footnote 24 We must therefore reconsider Stevenson's opinion that the printed treatise was a starting point from which he developed his manuscript.Footnote 25 Contrary to this opinion, at least concerning the first draft of the text, this manuscript preceded the printing of the Introdutione, which is in fact a rather short summary of the manuscript. A final confirmation of this chronology is provided in print by Lusitano himself in 1553, where he cites the manuscript on two occasions, referring readers who were curious to learn more about the subject to ‘nostro trattato grande di musica pratica’.Footnote 26 This reference implies that Lusitano had clearly intended to have this ‘trattato maggiore’ printed. If this is the case, why would a Portuguese musician living in Italy choose Spanish as the language in which to write an important musical theory treatise? Another similar example that may come to mind is that of Pietro Cerone and his 1613 Melopeo. In all likelihood, however, Cerone wrote his treatise during his stay in Madrid, and his employment with the Viceroy of Naples further explains the choice of idiom.Footnote 27 A case more comparable to Lusitano's is that of Diego Ortiz, a Spanish musician who, while working in Naples, published two editions of his 1553 Trattado de glosas in Rome, one in Spanish, and the other in Italian. Printing texts in Spanish in Rome was nothing out of the ordinary. The Dorico brothers, who dominated the sixteenth-century Roman musical printing scene, even published works in Castilian.Footnote 28 Writing in Spanish was also a possibility in Portugal, where Matheo de Aranda in 1533 and 1535, followed by Gonzalo de Baena in 1540, published music theory writings in Spanish, their native language.Footnote 29 In addition, there were certainly more financial opportunities in the form of patronage than there would have been for a treatise in Portuguese, and a reading of his Introdutione shows that even years after having started writing his ‘trattato grande’, Lusitano still lacked a mastery of the Italian language.

This source raises one last question for which no definitive answer has yet been made: how did the manuscript end up in the hands of Philippe Desportes? We know that in his youth he spent some time in Rome in the service of the bishop of Le Puy, Antoine de Sénecterre.Footnote 30 Did he acquire the manuscript during his stay in Italy, or did he add it to his collection after his return to France in 1567? If, as I have tried to show above, the manuscript Esp. 219 was in fact written by Vicente Lusitano himself, under what conditions could he have parted with it? To address these questions, we must briefly reconsider Lusitano's career, which although filled with significant dark areas and numerous question marks, depicts a unique narrative in Renaissance music history. It is the story of a musician without any well-established ties, a mixed-race priest from the southern tip of Europe who, after having lived in Italy for ten years, renounced the Catholic faith, married, and tried in vain to make a name for himself in Germany, before disappearing from history without leaving a trace.

To reconstruct Lusitano's biography, the notice written about him in the third volume of Diogo Barbosa Machado's Biblioteca Lusitania (Lisbon, 1752) is of great use, despite the unverifiable nature of the information it contains.Footnote 31 According to Barbosa Machado, Vicente Lusitano was born in Olivença, the episcopal centre located on the border of Portugal and the Spanish Extremadura.Footnote 32 Although nothing is known about his musical education, which he could have acquired in his home town, it is important to note that not far from Olivença was the important musical centre of Évora, where the Portuguese court stayed occasionally, and whose choirmaster was the Spaniard Matheo de Aranda. The affinities that Lusitano's manuscript shares with certain aspects of Aranda's treatise on counterpoint, which will be identified below, along with the temporal and regional coincidences, suggest that the Portuguese musician may have been educated, either directly or indirectly, by his Spanish elder.Footnote 33

Other biographical information provided by Barbosa Machado speaks of his status as a priest (‘presbytero do habito de São Pedro’) and mentions a teaching post in the Italian cities of Padua and Viterbo. No documentation exists to confirm his stay in these two cities, but it is in Italy where we find his first historical trace, in Rome in 1551. It was in this year that the Dorico brothers published his book of motets and that he took part in the debate with Nicola Vicentino that made him famous.Footnote 34 According to Stevenson, the dedication found in his book of motets confirms that Lusitano arrived in Rome in 1551 following the nomination of Dom Afonso de Lencastre, father of the dedicatee, to be the Portuguese ambassador to the Holy See. Lusitano also dedicated a secular motet found in the book to the young Dinis de Lencastre, who was possibly his pupil. After analysing the text of this motet, Stevenson argued that the composer was already employed by this influential Portuguese family before coming to Rome.

The volume of motets also establishes the Neapolitan Giovanthomaso Cimello as Lusitano's only known musical friend, who dedicated a Latin epigram to him in which he emphatically praises his musical talent.Footnote 35 Cimello could have played a role in Lusitano's dedication of the first edition of his Introdutione facilissima to the eighteen-year-old Marc'Antonio Colonna two years later.Footnote 36 This short essay on musica practica must have had some public success since it was published in two subsequent editions. It is also Lusitano's work most studied by musicologists, who have focused on two aspects of the treatise: first, the few pages about improvised counterpoint, and second, the closing discourse on the question of genera, which justifies Lusitano's position and serves as the first public reference to his debate with Vicentino.Footnote 37

The Introdutione presents other issues worthy of mention as well. First, Lusitano uses a peculiar Guidonian hand that breaks from tradition in avoiding the commonly used spiral for its organisation. Lusitano's method progresses finger by finger, which logically organises the gamut by fourths, starting with the low C sol fa ut at the bottom of the index finger (the positions on the thumb are not changed, except that they include all the hexachord syllables).Footnote 38 The second issue concerns his dedication to Marc'Antonio Colonna, whose first sentence is nearly an exact quotation from St Paul's first letter to the Corinthians in Antonio Brucioli's Italian translation, which was put on the Index by Paul IV in 1555, two years after the first edition of the treatise.Footnote 39 It is possible to read this allusion to St Paul as a sign of Lusitano's adoption of the heterodox ideas favoured by the spiritualisti as early as 1553. Could the reference to a teaching post in Viterbo by Barbosa Machado be linked to the Portuguese priest's particular religious sensibility?Footnote 40 The lack of documentation prevents us from going any further in answering this question, but it should be noted that the dedication to Colonna remains unchanged in later versions of the treatise printed in 1558 and 1561. The first of these two editions was released by the Venetian Francesco Marcolini, a printer known to have worked almost exclusively with local authors.Footnote 41 Adding this to the fact that this edition contains substantial additions in comparison with the Roman version of 1553, we can be fairly certain that Lusitano personally supervised the printing in 1558. This may very well coincide with the period of the composer's life that Barbosa Machado mentions in which he held a teaching post in Padua.Footnote 42

This hypothetical narrative of a journey from the South to the North, from Rome to Venice and Padua, is further supported by the fact that while Franceco Rampazetto was printing the third edition of the treatise in 1561, Lusitano was in contact with Count Giulio da Thiene (1501–88), an aristocrat from Vicenza who had adopted Protestant ideas around 1530.Footnote 43 Thiene left Italy for Lyons in 1556, then lived in Strasbourg in 1561 before eventually settling down in Geneva. He was close to Pier Paolo Vergerio, former papal nuncio in Germany and bishop of Capodistria, who became a Lutheran in 1549 before passing four years later into the service of Christoph, Duke of Württemberg. On 30 May 1561, following Thiene's advice, Vergerio wrote the Duke a letter recommending that he employ Lusitano, who had just arrived in Baden-Baden from Strasbourg. In the letter, Vergerio states that the singer was married without children and was a good Lutheran. Lusitano's journey to Stuttgart was by no means successful, and the payment of the 10 thalers he received for a six-voice Beati omnes that speaks to his compositional talents represents the last known trace of his errant life. None of the different hypotheses that can be made regarding the end of his life are encouraging. What options were available to a former Portuguese priest who married, converted to Protestantism, and hoped to live off of his musical talents in a Europe beset by religious wars? If he still had the manuscript with him at this time, it is possible that Lusitano followed Giulio Thiene in his travels, eventually finding refuge in France in Huguenot circles. This possibility might help explain how his manuscript ended up in Philippe Desportes's library after a particularly eventful journey.

LUSITANO'S LESSONS IN CONTRAPUNTO

Vicente Lusitano's ‘Great treatise of practical music’ will be analysed here only for its contributions to the study of counterpoint, though its scope largely surpasses this subject. To understand the structure of the entire work, it can be useful to turn first to the printed version of 1553, which functions as a summary. As its title suggests, the work is made up of the following five sections:

1. Canto fermo (Guidonian hand, solmisation and mutations, psalm tones)

2. Canto figurato (rhythmic notation according to the principles of mensural music)

3. Contraponto (two-part [semplice] and three-part [in concerto] counterpoint based on plainchant, and rules for canons [fughe] based on different melodic chant intervals)

4. Compositione (rules for simple three-part compositions and for writing cadences in four-, five-, and six-voice works)

5. Proportioni, generi (the three musical genera)

Many of the treatises devoted to musica practica follow this order, especially those written in Spanish in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, by Bizcargui and Montanos in particular.Footnote 44 It should be noted that this order follows a pedagogical logic that starts with the basic knowledge needed to perform plainchant and moves on to considerations more in the realm of musica theorica. The manuscript treatise, which differs from the printed text in terms of its rigorous and careful internal organisation, provides a considerably enhanced version of sections 2 to 5:Footnote 45

Libro primero: [De canto d'organo] (fols. 1–13)

Libro segundo: De contrapunto (fols. 13–62)

Capitolo primero: [introduction] (fols. 13–17v); Del arte de contrapunto (fols. 17v–38)

Capitolo segundo: Del contrapunto concertado (fols. 38v–44)

Capitolo tercero: De las fugas (fols. 44–48v)

Capitolo quarto: Del contrapunto sobre canto de organo (fols. 48v–57v)

Capitolo quinto: De la compostura (fols. 57v–62)

Libro tercero: De las proporciones (fols. 62v–84)

The part focused on counterpoint makes up the second book: with its fifty folios, it constitutes more than half of the manuscript, mainly because of its large number of music examples. With the exception of the long ten-page introduction at the beginning of the first chapter, which considers intervals in arithmetical terms and proposes a mathematical explanation of consonances and dissonances, the entire libro segundo is highly practical, and reflects a logical progression that Lusitano probably carried out in his teaching. I propose here to follow this curriculum, highlighting the major contributions of this text to the contemporary theory of contrapunto.

Contrapunto suelto

The second section of his first chapter, entitled ‘Del arte de contrapunto’, focuses on what the Spanish call contrapunto suelto, or ‘detached counterpoint’, which consists in adding a single part to a plainchant. Even though this term does not appear in the title of the first chapter, Lusitano uses it later in the treatise to differentiate it from contrapunto concertado, which refers to a collective practice. This first part of the treatise on counterpoint is the largest, owing to the 123 music examples found within it. This profusion, which makes for the treatise's richness, is explained by the fact that each rule is illustrated not by one, but by four examples, one for each separate part of vocal polyphony. This rather special modus operandi is not unique in sixteenth-century music theory. In 1535, Matheo de Aranda used exactly the same procedure in his counterpoint treatise. The uncanny similarities between these two texts further support the above-mentioned hypothesis that these two musicians had a pupil–teacher relationship.Footnote 46

The treatises written by Aranda and Lusitano also share the same graphic presentation of their music examples, since they use black square notation for plainsong and mensural notation for counterpoint. However, while Aranda chose eight different plainchant melodies to illustrate the melodic characteristics of each of the eight modes, Lusitano chose to base all his examples on a single Gregorian chant, the Alleluia Dies sanctificatus from the third Christmas mass. In both cases the authors were influenced by a pedagogical preoccupation: for Aranda, to combine contrapuntal and modal teachings, and for Lusitano, to show the various contrapuntal possibilities that can stem from the same material. Unlike in the Introdutione, where examples were based only on the first thirteen notes of this Alleluia, Lusitano often included the whole chant melody in his manuscript version.

Shortly after he copied his first note-against-note example in the soprano line, Lusitano clarifies:

Notice that if we want to write plainchant in black square notation, as in the example above, a semibreve in counterpoint or composition is equivalent to a breve, as Francesco de Layolle has clearly shown us in the offices of the mass. This is reflected by many others who compose on plainchant, and the parts are written without circles or semicircles, so they are considered equal to plainchant.Footnote 47

The lack of time signature thus implies the equal value of a black square breve and a measured semibreve, even if at times a ![]() can appear in the upper line, as in Example 2 below. To support this choice, Lusitano relies on the only printed text of the period to mix the two notations, the famous Contrapunctus seu figurata musica super plano cantu missarum published in 1528 in Lyons.Footnote 48

can appear in the upper line, as in Example 2 below. To support this choice, Lusitano relies on the only printed text of the period to mix the two notations, the famous Contrapunctus seu figurata musica super plano cantu missarum published in 1528 in Lyons.Footnote 48

In Lusitano's classroom, counterpoint was methodically taught using ‘species’, a means that he seems to have been the first to use in the sixteenth century, at least in the printed tradition. After him, Sancta Maria (1565), Montanos (1592) and Cerone (1613) used this technique as a preparation for florid counterpoint.Footnote 49 The absence of species in the Italian texts, which pass directly from note-against-note counterpoint to florid counterpoint, suggests that it was a tradition peculiar to the Spanish.Footnote 50 In his Introdutione, Lusitano identifies four different species: note against note, two notes against one, four notes against one, and finally three notes against one, ‘alla battuta de proportione’. There are many more species described in the manuscript, not only because each one is presented in each of the four voices. In duple metre, Lusitano describes a fourth species with eight semiminims for each breve of the chant; on the other hand, counterpoint ‘sobre canto llano a manera de proporcion’, if it starts with three semibreves against one note, continues with six minims, before finishing with twelve semiminims (Example 1). This last exercise also serves as a way for the contrapuntist to improve in the art of diminution: ‘this is difficult for the tongue, which through this exercise may make itself disposed to diminution’ (fol. 23v: ‘esto por ser algo dificultoso a la lengua, la qual con el exerçiçio se haze disposta a la diminuçion’).

Example 1 Paris, BnF Esp. 219, fol. 23v: Semiminimas sobre el canto llano de proporçion

Another original aspect of the treatise lies in the use of dissonance, an area where Lusitano shows himself to be particularly tolerant. After stating that in counterpoint of the ‘second species’ (two notes against one), all notes must be consonant, he goes on to explain that tradition authorises exceptions to this rule. In fact, ‘with this diminished measure [i.e. two minims equalling one black square breve], some wanted that there could be dissonances, such as fourths or seconds on the first and second beats’.Footnote 51 Given the audacity of the proposed examples, which feature fourths, seconds and sevenths on the second minim, and even sometimes on the first (see Example 2), Lusitano felt the need to justify these exceptions by adding a note after rereading his work: ‘the reason is that the second and the fourth are among the Pythagorean consonances, on which music was founded, according to Boethius in chapter 10 of his first book’.Footnote 52

Example 2 Paris, BnF Esp. 219, fol. 19v: Exemplo de las 2as y 7as

The main interest of the contrapunto suelto section lies in the numerous comments supported by a great many examples concerning musical style, especially considering that the majority of Renaissance texts about contrapuntal practice primarily dictate rules concerning voice-leading, without addressing the question of style.Footnote 53 Here, style is a major concern, even in routine species exercises. Lusitano describes the species of four notes against one in the following way: ‘and we must create each part in this way so as to achieve gracefulness, because a graceless melody does not lead far, and many can do it easily, but it is more difficult if we seek elegance, which the contrapuntist must try to do’.Footnote 54 This initial point resembles those that show up in most Renaissance texts offering vague and general advice. Francisco de Montanos also writes: ‘counterpoint, in order to be good, must have three things: a good air, a diversity of passages, good imitation’.Footnote 55 In 1553, Lusitano had already distinguished himself by giving stylistic advice to the beginning contrapuntist: ‘the proper way to sing counterpoint is to choose a short motif, and [when it has been] sung once or twice, sing a fast scale or broad passo, ascending or descending, as you like’.Footnote 56 The manuscript version incorporates these principles in a much more explicit way.

How can we create graceful and elegant counterpoint? Lusitano explains the means to do so in a long section concerning florid counterpoint, which he calls ligado. Introducing dissonances is the first step, since they are ‘muy necesarias’, and without them, ‘we cannot make sophisticated counterpoint’.Footnote 57 To be able to ‘bind counterpoint with grace’, one must then ‘imitate the chant in various ways’, or ‘have motifs that answer one another’ (fol. 24v). The idea that a motif should be repeated at different pitch levels is not unique to Lusitano, and we find it called contrapunto fugato in other Spanish essays as well as Italian ones.Footnote 58

In the following pages, Lusitano offers more specific stylistic advice:

You should know that the best possible way to make a counterpoint is to start with a motif, and after singing other motifs, to return to the first as a theme, and then sing some passages with great descending or ascending range according to what seems best. Because sometimes a motif loops in such a way that it is better suited to one passage than another, which is left to a good judge, which is reason. And we must not forget that the beginning has to be quiet, which means starting slowly so that we can progress gradually with diminutions.Footnote 59

The examples that follow illustrate this general rule, and express a certain degree of musical sophistication. However, the lessons are not yet complete: Lusitano next explains how to make pasos largos and contrapunto fugado (he uses both the terms pasos semejantes and pasos fugados). It is only after having explored these techniques that Lusitano summarises what constitutes stylistic excellence in counterpoint:

We can perform in another way, one whose success is due to a combination of motifs that are in turn imitated, broad, in proportion [i.e., triple time], and very embellished; this style is far more satisfying than any other, because we can see many things, namely the variety of imitated and broad motifs, as well as proportion, and more importantly, diminution.Footnote 60

The four musical examples relating to this rule are all characterised by a melodic style that appears to be quite modern for the period. Some passages more resemble instrumental sonatas from the beginning of the seventeenth century than vocal duets from the mid-sixteenth, in particular because of the figures of sequential diminution and the insertion of triple-metre sections within duple time. (See Example 3.) He comes back to this style of contrapuntal performance at the end of the chapter when he examines triple metre. He then refers to this style as ‘mixed counterpoint’, which combines all the necessary elements of an elegant counterpoint: imitation, pasos largos, insertions of triple-time sections and diminution.Footnote 61

Example 3

Paris, BnF Esp. 219, fol. 30: Contrapunto mixto, tenor sobre el canto llano

The last pages of the chapter involve specific exercises that require the singer to have a perfect knowledge of what has been stated before. Three areas are addressed: paso forçado technique, the regular use of syncopation and triple metre.Footnote 62

It is not the slightest merit of Lusitano's manuscript that it sheds light on paso forçado, a term whose ambiguity has recently been the subject of discussion. Linking the paso forçado that Aranda mentions with the contrapunto forçoso described by Juan Bermudo in 1555, Stephen Rice suggests that the terms implied a rhythmic constraint that differentiated it from contrapunto libertado.Footnote 63 Although he acknowledges that this explanation is not enough to explain Aranda's understanding of paso forçado, Rice does not continue this discussion any further. To begin with, a look at other Spanish sources allows us to confirm that the adjectives forçado and forçoso are synonymous and interchangeable. In his 1554 book, Miguel de Fuenllana includes two fantasias for vihuela composed on a passo forçado or passo forçoso.Footnote 64 These passos are marked by a series of solmisation syllables, implying melodic obligations rather than rhythmic ones. Lusitano defines the term in the following way: ‘Musicians call “ostinato motif” [paso forçado] the act of always pronouncing a motif in the same way, even when it is different; this can be done by mixing the naturals and flats, provided that you pronounce the motif always in the same way and that nothing else is added, as we will see below.’Footnote 65

Thus contrapunto forçado involves the constant repetition of a motif using the same solmisation syllables, independent of a given hexachord. The most famous example is Josquin's use of the technique in his mass La sol fa re mi, a motif commonly reused until the end of the Renaissance, and which not surprisingly makes up the first of the four examples Lusitano provides (see Example 4).Footnote 66 This emblematic paso forçado appears in at least one other counterpoint treatise. Pietro Cerone used la sol fa re mi to illustrate a type of counterpoint he called ‘de un solo passo’, a definition close to Lusitano's.Footnote 67 In spite of the criticism it was sometimes subjected to, this exercise was widespread. It was particularly used to select the candidates for a choirmaster post in Spain, in 1604 Toledo as well as in 1682 Girona, although here passo forçado was part of the composition test.Footnote 68

Example 4 Paris, BnF Esp. 219, fol. 30v: Passo forçado, tiple sobre el canto llano

Even though Lusitano's definition helps clarify the precise meaning of the term, it should be noted that his examples are followed by a long section on the systematic use of syncopation on a cantus firmus, suggesting a link between the melodic constraints imposed by the paso forçado and the rhythmic ones attendant upon syncopations. As for Aranda, they are valued for helping the contrapuntist to learn to master the use of dissonance, and can thus be compared to the species exercise, as a pedagogical tool in the art of counterpoint.Footnote 69 The systematic fashion in which all these case studies are considered, including the more extreme examples suggest an exercise thanks to which, like paso forçado, the more skilled contrapuntists could show off their talents.

Contrapunto concertado

The following chapter about counterpoint with multiple parts upon the chant is of great interest, as this subject is rarely addressed in Renaissance theory treatises. In addition, the music examples already available are mostly limited to two voices added to a cantus firmus, such as those Lusitano included in the Introdutione.Footnote 70 Since these five printed examples all differ from the fourteen examples that appear in the manuscript, Lusitano's overall contribution adds much more to our understanding of this practice than any other source on the subject by other theorists.

Contrapunto concertado is notable for requiring agreement between the different contrapuntists who create their melodic parts independently of each other. In this regard the practice is quite different from creating canons based on plainchant, a subject that Lusitano addresses in the following chapter, and that has generated an important theoretical literature, especially in the early seventeenth century. In the case of canons, in fact, no particular coordination is expected, apart from the need for additional singers to repeat the exact melody invented by a single contrapuntist at a predetermined distance and interval.Footnote 71 Concerted counterpoint is therefore differentiated from all other so-called improvisational practices in that it is the result of many decisions, rather than of a single one. Aranda clearly explains this idea in the commentary he included as a post scriptum to his treatise. He explains that what he has called in the body of his text ‘contrapuncto en armonia de tres y de quatro vozes’ involves ‘three or four voices together in various ranges in consonant agreement, that is to say, three or four distinct voices, each in its own range, singing in harmony’.Footnote 72

Apart from Lusitano's examples, which enable us today to gain a concrete idea of what a collective polyphonic performance on a chant might have sounded like, not only in three, but also in four and five parts, the manuscript also provides valuable information on how to proceed, starting with the following advice:

After the one-part counterpoint, one has to know how two, three, four, or even more contrapuntists can sing in harmony; for this, the first thing they must look at is the mode of the melody on which they want to sing, considering the cadences and the order to follow . . .

The second thing they must consider is that both contrapuntal parts await each other to show the grace of counterpoint, which must never be confused with disorder. This wait and this agreement are difficult to make extempore, however talented the singers, and they should know their respective vocal ranges to sing in harmony more easily.

The third thing they need to know is with what voices they will sing contrapunto concertado, because it is one thing to perform a soprano and tenor line on a plainchant written in the bass, and another to make a soprano and alto line, although they have points in common; and another to make the soprano and bass on a tenor plainchant, another to make the alto and bass, another to make the tenor and the bass; yet another to make the soprano, alto and tenor upon a chant in the bass.Footnote 73

Lusitano comes back to each of these different vocal combinations with the help of additional advice and examples, but already we can see from this general view that preparation was essential to the success of contrapunto concertado. This preparation involved choosing where and how each cadence would be performed by the ensemble (Lusitano greatly emphasises this point, which appears to have been crucial), and knowing each other's respective vocal ranges perfectly. In short, it was impossible ‘however talented the singers’, for them to give a satisfactory performance without having prepared in advance, and having ‘concerted’ on some key decisions. Once the cadence placements were agreed upon, since each part knew his melodic pattern perfectly, singers could move from one cadence to another without risking chaos.

The basic principle of concerted counterpoint, which Lusitano also explains in the printed version, is for the highest voice part to produce parallel tenths above the cantus firmus. These tenths are ornamented so as to conceal the device's extreme simplicity, in particular through melodic motifs that are imitated by the third voice (see Example 5). The quality of concerted counterpoint can be judged through this imitation between voices. Simplicity was valued: diminutions apparently were reserved for contrapunto suelto.Footnote 74

Example 5 Paris, BnF Esp. 219, fol. 39v: Conçierto de tiple y alto

Lusitano addresses the different combinations of vocal ranges by explaining their characteristics: when the soprano and the bass perform a concerted counterpoint (the chant being placed in between the two voices), the style is ‘delicate, but difficult’ (‘dilicada, mas difiçil’, fol. 40). When two altos sing together upon a plainsong, the issue of cadences is particularly problematic since their ranges are identical. Concerning four- and five-part counterpoint, the principle of parallel tenths in the soprano voice is kept, but the musical examples show that imitation between the voices is no longer possible.Footnote 75 Finally, the chapter concludes with an explanation of multi-voiced counterpoint below the chant, which Lusitano tells us is the most elegant but also the most difficult type. Singing below a plainsong, in fact, requires the singers to adjust all their reflexes, since the intervals are not same as those used when singing above the same melody. Thirds become sixths and vice versa, the fifth becomes a fourth, etc. The most frequently seen combination consists in having two altos beneath a soprano line. Lusitano provides two examples of this, the second being more elaborate thanks to the addition of suspensions.

The practice of counterpoint below a plainsong was widespread enough to have been written about by Aranda (who gives the example of an alto and a bass under a higher voice) and Montanos, who also considers it to be the most difficult. Pablo Nassare, in the mid-eighteenth century, describes it as a still widespread practice, and explains that it must be performed without changing the original clef of the plainsong, which might be a source of confusion for the singers.Footnote 76 It is not difficult to understand the reason why he considers this type of counterpoint so important. This happened every time plainsong was sung by children, at the upper octave.

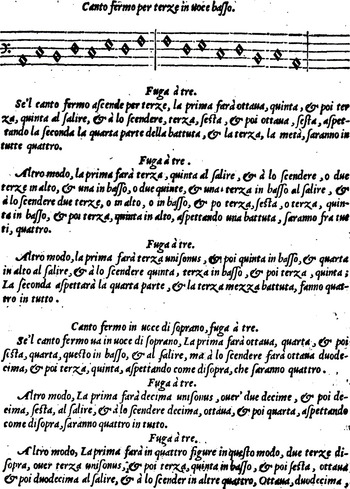

Abilidades

While concerted counterpoint requires that the musicians have an important common experience and prior agreement, the last two chapters come back to a type of counterpoint where musical performance depends on a single contrapuntist, able to generate two, three or even four-part polyphony. These last two chapters give the novice choirmaster the tools he will need to face the tests. In Lusitano's manuscript, as in other Spanish theoretical texts, these particular contrapuntal skills are often described by the term abilidades, which alludes both to the difficulty of those techniques and to the prestige associated with their mastery.Footnote 77 The first of these skills involves producing a canon above a plainsong, a common process in the late sixteenth and the beginning of the seventeenth century.Footnote 78 In his 1553 Introdutione, Lusitano was the first to take up the subject in print, but the section devoted to it is set out in such a way that it has never been studied in detail. Instead of giving practical examples, Lusitano follows a method similar to the one used in numerous counterpoint treatises since the thirteenth century to teach voice-leading, by imagining all the possible movements of regular interval progressions, from the second to the fifth, ascending or descending. The system is also the one by which the Renaissance diminution treatises pass on the knowledge of melodic ornamental patterns.Footnote 79 Lusitano's chapter entitled Regole generali per far fughe sopra il canto fermo follows that pattern, but it is difficult to understand today since it avoids every possible use of musical notation (see Figure 3). By learning these dozens of formulae by heart, and applying them to a given melody, it is possible to improvise two- or three-part canons at the unison, fourth and fifth above and below any cantus firmus. This section of the 1553 treatise therefore represents a major step in late Renaissance canon theory, but its historical importance has been overshadowed by the austerity of its presentation.Footnote 80

Figure 3 Introdutione (1558), fol. 20v

These seven pages of curt and arduous instructions end with the following statement: ‘Altre piu, & piu difficili fughe si truovano nel nostro trattato grande di musica pratica.’ This remark could lead the reader to believe that the manuscript contains additional instructions that follow the same method, but it has nothing of the sort. In fact, the chapter dedicated to canons includes thirty-two music examples based upon the usual Alleluia, which function as the practical implementation of the theoretical instructions of the printed version. As indicated by the author,

canons can be made in various ways, that is to say at the unison, fourth, lower fourth, fifth, lower fifth and octave. And they can be made above or below the chant. Other more laborious and less pleasant ones can be made, and for that reason we will not mention them. You note that canons can be made at the distance of a breve, semibreve or minim, except canon at the unison or octave, which is not made with a breve rest because it is too long.Footnote 81

The examples that follow respect the announced outline and end in a series of canons ‘far more delicate’ in that they are put below the plainsong. As a conclusion, Lusitano gives a final example that shows that from the mid-sixteenth century, some musicians were able to invent canons extempore at unusual intervals, as here at the lower second (see Example 6).Footnote 82

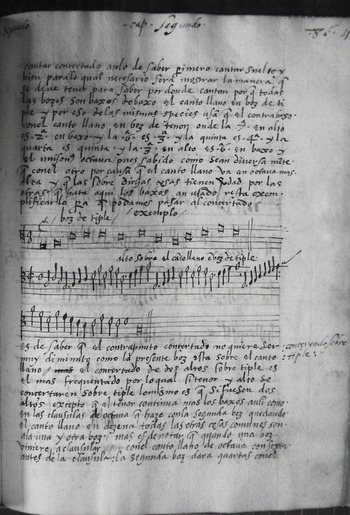

The last chapter, entitled Contrapunto sobre canto de organo, considers a type of counterpoint completely absent in the Introdutione. The thirty-seven music examples abandon the plainsong melody of the Dies sanctificatus Alleluia and take as support the superius of the first Kyrie from the Philomena mass by Nicolas Gombert, published in Venice in 1542 and reissued five years later.Footnote 83 Contrary to the rather small number of other Renaissance theorists who consider this practice, Lusitano is not interested in the ‘simple’ addition of a voice to a melody in mensural music. He is only interested in abilidades, and he considers them the pinnacle of practical music (‘la cumbre desta musica pratica’, fol. 49).Footnote 84

Example 6 Paris, BnF Esp. 219, fol. 48v: Fuga ad tonum sub, con pausa de breve, sobre el canto llano

The first series of skills consists in singing a melody while always using the same rhythmic value, from the long to the minim, either on the beat or syncopated. In some cases, as in long syncopations, the tolerance towards dissonances is particularly large, and even fourths can be considered as consonant. Some of these exercises, while presenting great difficulty for the performers, also offer an astonishing musical effect, as the one involving the syncopation of minims (Example 7).

Example 7 Paris, BnF Esp. 219, fols. 50v–51: Sincopadas sobre el Chirie, con pausa de seminima, en la qual sincopa se hallaran muchas falsas conpasibles

Afterwards, Lusitano shows us how to ‘fugar el canto de organo’ in six different ways: what the singer has to do here is to reuse Gombert's melody exactly, either at the unison, octave, lower or upper fourth or fifth, and to modify its rhythmic outline, so as to produce a duet with the original melody, creating the most possible harmonious counterpoint (see Example 8). These tours de force are followed by other exercises that offer singers even greater challenges:

After these abilities, we can do many other things, like singing a song; singing the psalm tone differentiae; singing the same melody in retrograde with itself; turn the book upside down; singing the prior abilities retrograde; make a canon at the unison with a minim rest upon a mensural melody. An expert can even make two plainsongs upon a mensural melody, which he must indicate with his hands while he is singing another voice, making four parts in total. And many other things mens' lively intelligence is accustomed to imagine and to do, the easiest of which we will mention here.Footnote 85

Example 8 Paris, BnF Esp. 219, fol. 51: Fuga en sub dyatesaron, del Chirie

The examples that follow, chosen to illustrate extremely refined contrapuntal techniques, show the ingenuity and virtuosity of the most gifted singers who are able to add a popular Spanish song upon a Kyrie by Gombert, or to combine the psalmodic differentiae of each of the eight tones on the same melody (which by definition corresponds to only one of the eight tones), or to again combine Gombert's superius with itself, but this time in retrograde motion (see Example 9).

Example 9 Paris, BnF Esp. 219, fol. 53v: En subdyapente al reves del Chirie

The last abilidades described in the manuscript allow a single contrapuntist surrounded by several singers to create three- or four-part polyphony from the superius of the Philomena mass Kyrie, using two different techniques. The first of these involves creating a canon at the unison or fifth, ‘which cannot be achieved without perseverance. And though these canons serve only to enliven the spirit, it is a great thing for a musician to have experienced these things, because it is through frequent contact with things like this that a man becomes an expert in the musical profession’.Footnote 86 The last examples of canons on the Kyrie even increase in difficulty by adding a fourth voice in breves signalled by the contrapuntist to the fourth singer ‘por la mano’, using the different places of the Guidonian hand (see Example 10). Thanks to this ingenious process, a musician singing counterpoint was able to enrich the polyphony with an additional voice, or even, as Example 11 illustrates, with two additional voices, by using his two hands to lead his partners. This latter case exactly corresponds to the sixth test of the 1604 Toledo contest: ‘upon a mensural music part, indicate two voices on the hand while singing another’.

Example 10

Paris, BnF Esp. 219, fol. 54v: Fuga en unisonus con pausa de minima sobre el Chirie (Canto llano y quarta boz sobre el Chirie y fuga)

Example 11

Paris, BnF Esp. 219, fol. 55v: Exemplo de todo sobre el Chirie

The coincidence of a theoretical document and an archival source referring to a common practice confirms my recent hypothesis regarding the use of the Guidonian hand in a contrapuntal context.Footnote 87 Another, much later, account shows that this practice lasted in Spain long after 1604. Antonio Eximeno (1729–1808), in his novel Don Lazarillo Vizcardi, describes this process and reports having seen it in his youth during a contest meant to nominate a choirmaster.Footnote 88 Actually, Eximeno's allusion to the use of the Guidonian hand results from a mistaken interpretation of a passage from Pablo Nassarre's treatise.Footnote 89 This is a very fortunate mistake for us, as it offers the only known accurate description of a process that must have spread to countries other than Spain, since the principle is also mentioned by Ludovico Zacconi.Footnote 90

Nassarre's chapter, read too quickly by Eximeno, is devoted to the possibility of the contrapuntist to add a third voice to a duet, or a fourth to a trio. This exercise is precisely the one the manuscript version of Lusitano's counterpoint manuscript ends with. The three examples that illustrate this point use two excerpts from the Credo of Gombert's Philomena mass. First, he shows how to add a middle voice ‘de inproviso’ to the duet Et resurrexit, an ability considered ‘difficult, but appreciated when done right’.Footnote 91 The difficulty is even greater, however, when adding a voice below polyphony: ‘the second way involves adding a low voice part to high ones, which is difficult and very laudable when it is made upon two voices. But if it is well done upon three voices, we reach the pinnacle of skill, as there is no greater ability in practical music.’Footnote 92 To illustrate the latter case, Lusitano uses the three-part Crucifixus in the Philomena mass. After giving some very practical advice on how to create a fourth middle voice upon a trio, he concludes: ‘if the fourth voice is performed in the bass part, there is no more advice to be given here other than to pay attention to the other three voices and to open your ears well, so as to make imitated motifs, and to listen to cadences, since the cadences of a bass part added to three concerted parts are very difficult’.Footnote 93

To pay attention to the parts, and to open one's ears: these words show how difficult it is for Lusitano to describe this ‘pinnacle of skill’ through written rules. If no other attempt comparable to the one in this manuscript seems to have survived, it is because to teach improvised counterpoint by means of a written treatise constitutes a challenge, to wit the written transmission of a practice that was deeply embedded in orality. A few pages earlier the author had already given up on showing certain abilidades on paper, because ‘one cannot illustrate them without the book’.Footnote 94

Counterpoint and compostura

It may seem paradoxical that at the very moment the author recognises that he has reached the limits of his ability to pass on his knowledge in written form, he devotes a final chapter to composition. What links are there between counterpoint and composition for Lusitano? How does he conceive the interplay between orality and written notation in the creation of polyphony? Though he does not directly provide an answer to a question that has been the subject of a long debate among scholars, the various remarks made throughout the treatise enlighten it in a singular way.Footnote 95

Lusitano's aim in teaching composition is set out at the beginning of the fifth chapter: he wants to show how compositions for three, four, five and six parts work, which means ‘namely to know how to start and how to make cadences’ (‘a tres y a 4 y 5 y a 6 se muestra la via, scilicet en los prinçipios y en las clausulas’; fol. 57v). In truth, the chapter's few pages only concern these two elementary compositional aspects, knowing how to start a piece, and how to write cadences. No other aspect is mentioned, apart from the last paragraph, where Lusitano gives his readers some general advice about word accentuation, and how to treat the length of the syllables in texts set to music. In short, although it is set at the end of the book, this chapter on composition is neither conclusive nor a crowning achievement after the study of counterpoint, and must be considered simply as an appendix to the treatise. What role and usefulness did Lusitano give the teaching of composition to the study of counterpoint? The answer is found towards the end of the third chapter, where he describes how to create canons below a plainchant:

When the plainchant is sung by the soprano voice, these canons are even more delicate, as is shown by the fact that only those well trained in composition can make them. It is therefore obvious that to invent them, composition is indispensable to a musician's training, and so we will briefly explain the stages of composition, because the methods are varied as are the choices of the composers.Footnote 96

Thus Lusitano here considers composition not as an end in itself, but as a useful tool to progress in the art of improvised counterpoint, a necessary exercise to master the most advanced techniques of cantus super librum. This idea is reiterated at the end of the fourth chapter concerning the addition of a fifth part to a quartet, a difficult exercise whose success ‘depends on the diligent and frequent use of composition’. This very idea is expressed by Diego Ortiz in 1553, concerning the same exercise.Footnote 97

Lusitano and Ortiz were not the only ones to think that composition was propaedeutic for the practice of counterpoint, since Juan Bermudo expresses this opinion in the same period. To practise contrapunto concertado, ‘the singer greatly employs composition so that he knows all the possible movements of each part by heart’.Footnote 98 Thus, singing upon the book and the res facta are not different in nature. As Lusitano says, ‘everything done in composition can be done in counterpoint alone because composition is nothing more than counterpoint’.Footnote 99 The two distinguish themselves as being different modes of polyphonic creation that are neither concurrent nor hierarchical. In certain places in the treatise, Lusitano nevertheless recognises that certain cadences or contrapuntal combinations are more suited to composition than to spontaneous performance ‘de inproviso’.Footnote 100 Through these remarks, Lusitano clearly separates improvisation from composition, and seems to praise the latter for being free from the constraints imposed by improvised creation. But one of the greatest merits of his treatise is the clarification he makes between notions that music history has perhaps assimilated too quickly. We would be wrong in fact to mistake singing upon a book for improvisation. What characterises contrapunto is orality, the act of creating without a written medium, and this must not be misunderstood as being a necessarily improvised practice. This is why, rather than a binary opposition between ‘improvised counterpoint’ and composition, Lusitano considers three different types of polyphonic creation: improvised counterpoint, prepared counterpoint, and composition.Footnote 101 It is a pity that he did not develop this idea further in the manuscript, but this hint is of extreme importance, since it explains how singers could build counterpoint just as elaborate as the examples noted in the manuscript by preparing them carefully, pondering over them exactly like composers over their works. When this preparatory process was over and they were singing upon the book, the role of improvisation during a performance was controlled enough so as to concentrate more on the ornaments than on the structure. In the same way, the difference was of course not so great between improvised and thought-out counterpoint as it was between the latter and composition. In short, assimilating ‘performed’ counterpoint and ‘improvised’ counterpoint both oversimplifies a complex phenomenon and overlooks the various practical details. For the importance and nature of improvisation during contrapunto practice undoubtedly varied according to circumstances.

CONCLUSION: CONTRAPUNTO IN CONTEXT

After reading the manuscript, it becomes obvious that in Lusitano's mind it is not composition but in fact the ability to perform contrapuntal feats extempore that constitutes both achievement in musical study and the criterion determining the artistic value of a musician.Footnote 102 It thus provides a theoretical and pedagogical support for the 1604 Toledo document, just as this document enlightens Lusitano's instructional text in return. Without it, it would appear to be disconnected from the reality of musical life. This treatise seems, however, to be deeply rooted in daily life, and has to be interpreted as the private specimen – the master's personal copy – that concerns a discipline compulsory in every musician's study curriculum during the period. To limit ourselves to a well-known contemporary case study, Francisco Guerrero's 1551 contract as master of the children at Seville Cathedral stipulates that he must teach them ‘plainsong, mensural music and counterpoint upon plainsong as well as on mensural music. He also must teach them composition as well as the other abilities needed by these children to become both accomplished musicians and authors.’Footnote 103

More than a hundred and fifty years later, counterpoint was still used to judge a musician's value and his ability to conduct a choir in the Spanish kingdom. The conditions required to become a choirmaster described by Nassarre in 1723 are identical in all points with those the four candidates in Toledo were subjected to in 1604.Footnote 104 This omnipresence of counterpoint in musical life can be explained by the simple reason of its usefulness. Lusitano reminds us of this in his treatise: ‘All the things that have been written above enliven the spirit and are very beneficial for the numerous needs found in music.’Footnote 105 Among the ‘numerous needs’ for singers of musical chapels, one of the most important was to produce polyphony for the Proper of the Mass. It is not by chance that Lusitano chose to present all of his musical examples on an Alleluia. In Burgos in 1533, the minutes of the chapter meeting specify that the Alleluia was sometimes sung in contrapunto concertado.Footnote 106 We can infer similar practices from the two following articles, extracted from the statutes of Charles V's and Philip II's chapels:

13: Also, when the choirmaster who is in charge of the said lectern or stand asks for singing a duet or a trio, those who have been asked must stand in front of the book and do what they were asked to do, at the risk of being punished and penalised.

14: Moreover, the verse and the Alleluia must be sung every day from now on as it was done on holy days until today, and the children's master has to make them sung by each singer, and they have to stand in order without mixing up, and none of them can refuse to sing the said duet or trio, or anything that suits the said service, when the master asks them, at the risk of receiving the given punishment, unless they have a legitimate reason.Footnote 107

Four reasons can be put forward to justify a reference to the practice of contrapunto in those two articles, even though the word is not quoted. First, the reference to a particular but adjustable (duet or trio) vocal combination leads back to a performance tradition. Secondly, the fact that this tradition of performance could possibly be refused by some singers underlines that it was optional, and that could be done without – doubtlessly by singing monodic plainsong. Thirdly, that the singers were obliged to stand ‘in front of the book’ alludes to the cantus super librum practice and finally, the particular liturgical occasion of the Mass itself constitutes a last argument in favour of that hypothesis.Footnote 108

Other sources indicate that the members of the Spanish royal chapel used to sing polyphony without written music at other times. Relying on the Calendarium capellae regiae, a document annexed to the Leges et constitutiones capellae Catholicae Maiestatis, Luis Robledo was able to demonstrate that Philip II's chapel seldom sang from written compositions, but that the vast majority of the polyphony was made of fabordón and contrapunto. The Calendarium designates four different ways to sing, each one corresponding to a particular liturgical occasion: in tono, contrapunto, fabordón, in musica. The first and the last one, that is to say plainsong and composed music (also called canto de organo), represented the exception, while the norm was fabordón and counterpoint. In the latter case, it concerned the antiphons at Vespers and Compline as well as the responds at the Palm Sunday procession and the antiphons at Lauds on Christmas Day.Footnote 109

Though it is impossible today to know the reality of what performed counterpoint sounded like during the Renaissance, Lusitano's treatise gives us access, thanks to his music examples, to a kind of ideal that was sought by the sixteenth-century singers. To what extent did reality match it? It certainly depended on places and moments. One will be convinced of this after reading the contradictory opinions of Nicola Vicentino and Juan Bermudo in their respective treatises, both published in 1555. Undoubtedly, the strong criticisms of the Italian musician levelled at contrappunto alla mente can be partly explained by his enmity with Lusitano, an eminent specialist on the subject, but the fact still remains that they must also have been based on actual experiences. On the other hand, we also know about Bermudo's wonderment, whose testimony reminds us that Toledo could lean on a solid and ancient contrapunto tradition:

In the supreme chapel of the late most reverend Fonseca, archbishop of Toledo, I saw singers so gifted in the art of counterpoint that if it had been written down, it could have been sold as a good composition. In the royal chapel of Granada, a place no less religious than learned, there are such great contrapuntal abilities that it would take far more delicate ears than mine to understand them, and another quill to explain them. . . . This is why some wished this art not to be called counterpoint, but rather composition.Footnote 110

Lusitano's treatise is part of the perspective described here by Bermudo, one of a polyphonic process that keeps privileged links with orality alive, a process that cannot be merely reduced to the performance of written compositions. From Matheo de Aranda to Pablo Nassarre via Bermudo and Montanos, numerous theoretical resources make the Iberian peninsula a privileged observation point of these phenomena, but it would be wrong to believe that counterpoint was specifically Spanish. One can find almost exactly the same opinion as Bermudo's in the writings of the Neapolitan Scipione Cerreto: ‘While I was in Rome in 1573, in the era of Pope Gregory XIII, and another time in 1601, in the era of Pope Clement VIII, I heard in the Pope's chapel a very elaborate counterpoint whose written transcription could not have improved what had been done extempore.’Footnote 111 Cerreto's memories remind us that Rome was a major centre of contrappunto alla mente practice in the second half of the sixteenth century and it was also the city in which Lusitano printed his Introdutione and wrote (at least a part of) his manuscript.Footnote 112

In the field of improvised counterpoint, there is still much to be understood about the specifics of the different local traditions. As far as the Roman and Iberian traditions are concerned, Lusitano's manuscript is a document of major importance for future research, and we may hope that its recent rediscovery will prompt many more works on a topic that has up till now been wrapped in mystery.

APPENDIX

The Twenty Tests for Applicants for the Post of Choirmaster at Toledo Cathedral in 1604

Source: Toledo, Catedral, Archivo y Biblioteca Capítulares, Actas Capítulares 23, fol. 183r–v. (The corresponding examples of Paris, BnF Esp. 219 are indicated in square brackets.)

1. Contrapunto suelto sobre canto llano de contrabajo [Lusitano, fols. 18–38], y de concierto, puntando dos vozes por la mano y cantando otra.

2. Contrapunto suelto sobre canto llano de tiple [Lusitano, fol. 43], y de concierto, puntando una voz por la mano y cantando otra.

3. Contrapunto suelto sobre canto de organo sobre qualquiera voz [Lusitano, fols. 49v–54], y de concierto, puntando una voz por la mano y cantando otra [Lusitano, fols. 54v–55].

4. Sobre un duo, tercera voz; sobre un tercio, quarta voz; sobre un quarto, quinta voz [Lusitano, fols. 56–57v].

5. Trocar las vozes del duo tercio y quarto, que el tiple se diga otava al bajo, y el contrabajo otava arriba.

6. Sobre una voz de canto de organo, puntar dos vozes por la mano y cantar una [Lusitano, fol. 55v].

7. Sobre un tiple y contralto, puntar una voz por la mano y cantar otra.

8. Sobre una voz de canto de organo, cantar un passo forçoso y puntar otra voz por la mano con el mismo passo [Lusitano, fol. 56: ‘these are things that should be shown in front of the book rather than in written form’].

9. Sobre un tercio, dezir una quarta voz, todos semibreves [Lusitano, fol. 56: ‘these are things that should be shown in front of the book rather than in written form’].

10. Sobre una voz de canto de organo, dezir breves todos, esperando dos pausas a lo mas largo [Lusitano, fols. 49v–50].

11. Sobre lo mismo, dezir todos semibreves en sincopa en regla y en espacio, y otra vez minimas en sincopa [Lusitano, fols. 50–1].

12. Contrapunto sobre una voz de proporcion [Lusitano, fols. 36–8].

13. Sobre un tiple de canto de organo, cantar una voz y pronuncie por solfa otra que cante un cantor.

14. Sobre una voz de canto de organo, fuga en 4a y 5a [Lusitano, fol. 54r–v] y lo mismo sobre canto llano de tiple [Lusitano, fol. 48v].

15. Una fuga en segunda sobre un tiple [Lusitano, fol. 48v, ‘sobre contrabajo’].

16. Composicion de todas maneras.

17. Regir el fasistor subiendo y baxando las vozes todas.

18. Canten los musicos sin pausas, aguardando al maestro los buelva.

19. En el discurso de la musica, calle algun musico para ver si el maestro echa de ver que falta aquella voz.

20. Examinese en la misa de Jusquin super voces musicales, y en los canones del Benedictus de la misma missa, o en otros del mismo autor.