The historiography of musical genres is interested in continuity: continuity in forms, structures, intent and function. Within the history of settings of the Christmas narrative, scholars have looked for and often found continuity between early examples such as Heinrich Schütz’s Historia der Geburt Jesu Christi (1660/64)Footnote 1 and Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio (1734). Both originated in a German, Lutheran environment, were settings of the Christmas narrative, and, to later interpreters, seemed to cater to a folk-like (‘volkstümlich’) sentimentality that was at least since the nineteenth century associated with the celebration of the birth of Jesus. In 1936, the Schütz biographer Hans Joachim Moser saw the folk-like sections in triple metre, which open several of the intermedi in Schütz’s piece, as a direct predecessor to some similarly lilting movements in Bach’s Christmas Oratorio.Footnote 2

While it is possible to argue for continuity between Schütz and Bach, a close reading of the historical circumstances of their inception and the performative function reveals discontinuity, even dissonance, between the compositions by the Dresden Kapellmeister and the Leipzig Cantor. This essay will explore these dissonances and discontinuities and locate Schütz’s work in a cultural context that is significantly different from Bach’s (and our own, for that matter). The first part of this study will introduce the piece by Schütz and its performative context; this will provide a canvas for an analysis of the shifts in the understanding as well as the ritual practices around Christmas in the late seventeenth century which separate the Historia der Geburt Jesu Christi (Christmas Historia) from the Christmas Oratorio.Footnote 3 The differences come into sharpest relief when we explore the tradition of Kindelwiegen, the physical rocking of a cradle or an imaginary baby, which is mentioned in Schütz’s piece but which had been prohibited in Bach’s time. The rejection of Kindelwiegen was part of a larger battle of Protestant theologians during the seventeenth century against folk traditions, such as carnival pageants, Christmas masks, and other forms of spectacle, which the literary theorist Michael Bakhtin has described as ‘carnivalesque’.Footnote 4 While the ritual rocking of the child was one of the least contested carnivalesque practices in the seventeenth century, it fell victim to fundamental reforms of the celebration of Christmas in the 1680s and it had mostly disappeared by the early eighteenth century.

The situation was still different when Heinrich Schütz composed his setting of the Christmas narrative for a performance on Christmas Day 1660. The first performance most likely took place in the afternoon Vespers, which began at 2 p.m. The piece retells the nativity story from Luke 2, the arrival of the Three Wise Men, and the flight to Egypt as well as the return, both transmitted in the Gospel of Matthew. The court diaries for that day report the performance of ‘die Geburth Christi in stilo recitativo’ (the birth of Christ in recitative style).Footnote 5 Even though the court records do not name the composer, it is safe to assume that the piece performed was Schütz’s Historia Der Freuden- und Gnadenreichen Geburth Gottes und Marian Sohnes. Parts of the composition appeared in print in 1664. According to the title page of the print, the composition was commissioned by Saxon Elector Johann Georg II.Footnote 6 Schütz highlights in the afterword that, to his knowledge, the piece was the first setting of the part of the evangelist in recitative style ever to have appeared in print in Germany.Footnote 7

PRINTING THE HISTORY

When the Christmas Historia was printed in 1664, the print only contained the recitatives for the evangelist; the intermedi were excluded. Schütz explains in the afterword that they could be obtained in manuscript from his agents, the organist Alexander Hering in Dresden and the cantor at St Thomas’s in Leipzig, Sebastian Knüpfer.Footnote 8 The composer justifies his decision in the afterword to the print:

it is not to be passed by without comment that the author had misgivings about issuing the same [concertos] in print, since he understands that, outside of princely well-appointed Kapellen, these inventions of his would scarcely achieve their proper effect elsewhere. It is left to each, however, may it perhaps please him to acquire a copy of the same, to contact either the cantor in Leipzig or else Alexander Hering, Organist at the Kreuzkirche in Dresden, where, for a small fee, these could be obtained with the permission of the author . . .Footnote 9

Alternatively, Schütz suggests that buyers of the recitative sections might compose their own intermedi or have them composed by someone else. Basil Smallman assumes that Schütz’s decision was motivated by a concern that the pieces could be performed at courts that had a musical infrastructure that was inferior to the conditions in Dresden. ‘Schütz fears that, if the work . . . were to be made too readily available, a number of smaller German courts without the adequate facilities might be tempted to mount performances of it and almost certainly with unfortunate results.’Footnote 10 Although this fear might have been justified in some cases, the situation was more complex. Schütz probably wanted to avoid performances in smaller cities and villages around Saxony and Thuringia. These smaller venues often had a very ambitious musical culture, supported by local school choirs and volunteer choirs (Adjuvanten) for whom the vocal and instrumental requirements of the piece might indeed have been too challenging. Schütz himself had in 1657 consented to a publication of his smaller and less demanding works, edited by his student Christoph Kittel. The Zwölf geistliche Gesänge (Twelve Sacred Songs) target in difficulty and repertory the demands of these ensembles in smaller churches.Footnote 11 While the singers in some Thuringian villages might have been technically able to perform the vocal parts, they often did not have the instrumental forces and number of singers available to follow the nuanced instrumentation Schütz intended for his intermedi. Consequently, the market for a work like the Christmas Historia was quite small and the costs for printing the parts for the whole piece was economically not reasonable. Therefore, as Stephen Rose suggests, ‘scribal transmission was the most feasible option’.Footnote 12 That way, Schütz could still publish the most innovative part of the piece, the part of the evangelist in recitative style, while avoiding the costs for the production of the other parts.

The intermedi have come down to us in two separate manuscript sources of different quality and authenticity. An earlier version (which preserves a version pre-dating the print from 1664) is now owned by the Düben Collection in Uppsala, Sweden, and a later version has survived in the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin. Because of the significant differences between the two manuscript sources (which also include the part for the evangelist) and the print of the evangelist’s part, the three versions have been assigned three different numbers in the catalogue of Schütz’s works: Uppsala (SWV 435a), print version (SWV 435), and Berlin (SWV 435b).Footnote 13

In order to give the buyers an idea of the complete historia, the afterword to the print from 1664 includes a description of the missing framing movements and eight intermedi. The descriptions also list the instrumentation for each section and indicate when the rocking of the child (Kindelwiegen) had to take place. While the use of the cradle was optional, it is worth noting that it still must have appeared so important to Schütz (and his editor) that these remarks were included in the descriptions of each intermedium. Table 1 gives an overview of the movements as well as their vocal and instrumental forces and the use of Kindelwiegen.Footnote 14

Table 1 Structure and instrumentation of Heinrich Schütz, Christmas Historia

As Tim Carter has pointed out, Schütz’s symbolic use of the instruments and voices conforms to seventeenth-century conventions.Footnote 15 The part of the angel is sung by a cantus and King Herod is represented by a bass. The shepherds are sung by three higher voices while three tenors perform the part of the Three Wise Men. Common for seventeenth-century conventions is also the use of the obbligato instruments, when Schütz assigns the regal trumpet to King Herod and the pastoral flutes to the shepherds. While the parts in and of themselves are not particularly challenging compared to other works from the second half of the seventeenth century, the performance with all its sonic symbolism requires a large vocal ensemble: four basses, at least three tenors (if the evangelist sang one of the Wise Men as well), three altos, and two cantus. The requirements for Schütz’s historia appear quite luxurious; the same is true for the obbligato instruments. Even if the flute parts in intermedium III were played by the violinists, which would have been quite common in the middle of the seventeenth century, and the clarini in intermedium VI by the players of the trombones, a performance would still have required at least seven instrumentalists plus the players of the basso continuo section. Altogether, the ensemble required for the performance would have been comprised of at least twelve skilled singers and about ten instrumentalists.

As Eva Linfield has argued convincingly, the composition of the large-scale piece was made possible by the extended performance forces after the succession of Johann Georg II as Elector of Saxony in 1656.Footnote 16 The combination of his own musicians with his late father’s chapel increased the number of performers available to Schütz and provided the ensemble necessary for a piece of the dimensions of the Christmas Historia.Footnote 17

MODELS AND TRADITIONS

Heinrich Schütz’s Christmas Historia was not the first of its kind that was performed at the court in Dresden. In 1602, his predecessor in the position of Hofkapellmeister, Rogier Michael (1554–1619), had composed a setting of the Christmas narrativeFootnote 18 and is likely that Schütz’s composition was written to replace Michael’s piece in the same way as his Auferstehungshistoria had in 1623 replaced an older setting of the Easter story by the sixteenth-century composer Antonio Scandello.Footnote 19 This is even more likely as Michael’s composition is transmitted in a manuscript that also contains the piece by Scandello.Footnote 20

The structure of Michael’s composition is similar to its later successor. The piece is framed by an introduction (‘Eingang’) and conclusion (‘Beschluß’) and most of the gospel text is sung by the tenor, while direct speech by one or more characters is sung in a polyphonic setting for two or more voices. The differentiation between evangelist and soloists conforms to the conventions of other historiae without instrumental accompaniment in the seventeenth century, such as Schütz’s own Passions. The polyphonic settings in Michael’s historia employ different singers, depending on the characters: Angel: AT; Herod: B1, B2; Simeon: TB.

Like Schütz’s Christmas Historia, Michael’s setting covers the Christmas narrative from the beginning of Luke 2 (‘But it happened at that time that a commandment went out from the Emperor Augustus’) to the return of Jesus and his parents from Egypt; but inserted here are also the stories about Simeon and Hanna (Luke 2:22–38), which are missing in Schütz’s composition. Like the later piece, the text compilation in Michael’s composition follows the arrangement in Johannes Bugenhagen’s Evangelien Harmonie (Gospel harmony) from 1554.Footnote 21

While Michael gives each of the polyphonic sections an individual treatment, the part for the Evangelist is based on a simple cantillation model in the fifth mode (Lydian), with B flat and the characteristic ascending triad (F–A–C) at the beginning of each sentence (see Example 1a below). When Schütz replaced the piece by his predecessor in 1660, he wrote a new part for the evangelist, which now featured a modern basso continuo accompaniment and was melodically more adaptable to the individual text. And yet, he maintained the key of Michael’s piece and his newly composed setting of the gospel text could easily be combined with Michael’s version of the sections in direct speech with the exception of the missing sections. It is possible that Schütz, who would then publish the part for the evangelist independently in 1664, originally conceived his new setting as a replacement for Michael’s formulaic gospel setting and only then decided the rewrite the polyphonic sections as well and turn them into intermedi. While it is impossible to prove this, Schütz himself suggests the possibility of combining his new setting of the evangelist in stile recitativo with other settings of the sections in direct speech:

Also on this account, he [Schütz] leaves it to the discretion of those, who might be inclined to use this evangelist [choir] of his for themselves, to compose these ten concertos (the texts of which are also to be found together with these prints) entirely anew in the manner preferred by them and for the available musical body [corpus musicum], or to have them composed by others.Footnote 22

Example 1 Reciting tones in (a) Michael’s and (b) Schütz’s Christmas Historiae

Instead of newly composing the ‘concerti’, a performance could also have used older settings of the texts. A piece that would have been fitting (at least in Schütz’s local tradition at the Dresden court) would have been Rogier Michael’s Weihnachtsgeschichte. Schütz’s print from 1664 even allowed for the use of a traditional reciting tone instead of his modern setting.Footnote 23 While the model he suggests is still quite formulaic, it avoids the ascending triad of the fifth tone and uses a as reciting tone instead; the result is smoother than in the older piece by Michael (see Example 1b).

The Dresden sources from the late sixteenth century do not mention when Michael’s historia was to be sung. The liturgical order from 1581 does not list a Christmas Historia; however, the court diaries from after 1650 mention that the historia replaced the Scripture reading during the Christmas Vespers and it is safe to assume that this was the place during which Michael’s piece was already performed in the first half of the century.Footnote 24 The structure of the Vespers service at the court in Dresden underwent several changes during the seventeenth century.Footnote 25 What remained relatively stable is the sermon in the centre of the liturgy, framed by readings and hymns on the one side and the Magnificat on the other side. Michael’s and Schütz’s settings of the Christmas story would therefore have been performed before the sermon. The liturgical placement will be significant when we discuss the function of Kindelwiegen in Heinrich Schütz’s piece, as this practice had traditionally been part of the singing of the Magnificat, usually performed during the German songs that were interpolated into the Latin text. Since these German songs are mentioned both in Vespers orders from the early seventeenth century as well as in the revised order from the 1660s,Footnote 26 it is clear that the tradition was maintained throughout the seventeenth century.Footnote 27

While Schütz’s setting of the Christmas narrative makes specific provisions for the rocking of the cradle (including a lilting triple metre in the specific sections), this is missing from Michael’s composition from the early seventeenth century. Most of the polyphonic movements are in alla breve time and even the only movement in triple time (no. 11, High Priests and Scholars of Scripture) does not feature the rhythm in a way that would invite physical action.Footnote 28 In short, there is no indication that the Kindelwiegen would have been practised during Michael’s Weihnachtsgeschichte. If it was practised during the liturgy, which is most likely, it would only have happened during the German interpolations in the Magnificat.

When Schütz made the Kindelwiegen part of the Christmas Historia, the Kindelwiegen was either moved from the Magnificat after the sermon to the setting of the Gospel text before the sermon, or – which is more likely – it occurred twice, both before and after the sermon. This not only meant a quantitative emphasis on the physical action but also a qualitative one: the rocking of the child now became part of the narrative action of the Gospel text. Instead of being a meditative act during the singing of the song, the performer now physically enacted a part of the story and thus became part of this action himself. While it would be hasty to relate this shift to contemporary opera, the two genres do share some similarities: not only does Schütz’s composition use the stile recitativo to set the text but it also employs physical movement in the ‘staging’ of a narrative. In this respect, the later piece is indeed more operatic than the composition from the early seventeenth century.

MULTI-SENSORY RITUALS

Basil Smallman has suggested that Schütz’s decision to set the Christmas narrative in such an elaborate way was in part due to a ‘Lutheran . . . reluctance to admit visual religious art, with its deeply-rooted Catholic associations, as an everyday medium for spiritual enlightenment’ and therefore ‘had engendered a reliance on the association between the textual imagery of the bible and music, as the most effective alternative from of religious stimulus for their [i.e. Lutheran] followers’.Footnote 29 While Smallman is correct that German Lutheranism did indeed develop a much richer musical than visual culture, this had very complex reasons and did not apply to the court in Dresden. The descriptions of the Christmas celebrations in Dresden, which relied to a large degree on visual stimuli as well, speak a very different language. The performance of the Christmas Historia in the princely chapel in the Saxon capital was embedded in a larger artistic, multi-sensory programme. Especially the liturgical reforms in the early 1660s, which were codified in the revised liturgical order of 1662, had as a goal a particularly splendid celebration of the court services.Footnote 30 A description of the Christmas service in 1678 might give an impression of the lavish character of the celebrations in Dresden, in which Schütz’s compositions were embedded. Even though the description post-dates the composition of the Christmas Historia, it reflects the ideals of the liturgical reforms that had been initiated in the early 1660s, and for which Schütz had composed his elaborate setting of the Christmas narrative. While not every detail might have been the same in 1660 (or 1664, when Schütz published the piece), the following description reflects the spirit and character of the Christmas liturgies at the court chapel in Dresden:

the church would be bedecked in the following manner: the parament of the pulpit would be of white satin, embroidered with silk flowers, upon which is depicted the throng listening to Christ in the temple. The altar would be bedecked with a red velvet parament, edged in gold, and embroidered with a depiction of Mary as she held Christ on her lap after he was taken down from the cross. On the altar would stand the ivory crucifix and the gilded silver embellished candlesticks with the wax candles. The choir would be decorated with tapestries, upon which the coats of arms of the electoral provinces are embroidered, and the floor covered with flowered tapestries, and prepared with red velvet chairs and cushions. The church would be decorated with gold and rich satin embroidered tapestries, which depict the following narratives: on the right side, ‘The Last Supper’, and on the left side of the same, ‘The Ascension of Christ’. Over the church door, the ‘Ecce Homo’. Beside it, under the arch where the councilors stand, ‘The Judgment and Hand washing of Pilate’; and the electoral loge, ‘The Ascension’; over the sacristy, ‘Christ led out to be crucified’; on the right side of the pulpit, ‘Christ on the Cross’; under the arch where the ladies-in-waiting stand, ‘Christ being taken down from the Cross’, ‘The Resurrection’, and ‘The Descent into Hell’; on the electoral balcony, ‘The Birth of Christ’ and ‘The Three Kings’; on the electoral box, a red velvet hanging, embroidered with the coats of arms of Denmark, Electoral Saxony, and Brandenburg. And this decoration would remain until [the following] Friday, when it would be taken down.Footnote 31

Another source, this time closer to Schütz’s composition, reports the use of expensively ornate vestments that depicted the Christmas story. We learn that the chasuble of the celebrant on New Year’s Day 1665 ‘was of black velvet, upon which the Nativity scene was . . . depicted in pearls’.Footnote 32 Even though we do not know which of these pieces of art were in place when Schütz performed his Christmas Historia, it is clear that music, at least at the court in Dresden, was not a substitute for visual art, but rather a supplement in a multi-sensory ritual that involved the spoken word, music and visual art. The physical enactment of the rocking of the child fitted well into this multi-sensory experience of the religious ritual.

INTERMEDI

As mentioned earlier, the text for Schütz’s Christmas Historia (like its predecessor by Rogier Michael) is based on Bugenhagen’s Evangelien Harmonie, a sixteenth-century synthesis of the stories of the four gospels, which was widely used in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Even later pieces such as Bach’s Ascension Oratorio BWV 11 still rely on Bugenhagen.Footnote 33 The two framing movements were added by Schütz but even they represent traditional material. The opening movement is a conventional announcement of the biblical story, similar to the one used by Michael.Footnote 34 The final movement in Schütz’s composition is a setting of the German translation of the Latin Christmas sequence Grates nunc omnes (Let us all give thanks), a text that belonged to the common elements of the liturgy during the Christmas season in German Lutheranism.Footnote 35 Rogier Michael had already used the same text in his setting from the early seventeenth century.

While the two framing movements serve as introduction and conclusion, the eight intermedi are part of the narrative and set passages in direct speech. The movements are more than merely a more elaborate setting of the biblical texts. Schütz sets the words as small-scale sacred concertos, interpreting the words, intensifying their expression though repetition, even creating independent musical structures by repeating musical and textual phrases to create ritornelli. The intermedi, while keeping the original biblical text, serve the function of arias in mid-seventeenth-century opera, by adding not only a dramatic element but by providing an opportunity for reflection and interpretation. The movements can be divided into two types:

-

1. turbae (with larger groups speaking): nos. II, III, IV, V

-

2. soliloquies (individuals speaking): nos. I, VI, VII, VIII

Three of the soliloquies are sung by an angel (I, VII, VIII), and it is these movements where Schütz suggests the inclusion of the rocking of the cradle in the performance.

Even though pastoral dramas were popular on the seventeenth-century stage and on the opera stage in particular, Schütz was not interested in highlighting the pastoral aspects of the nativity story.Footnote 36 Other composers and poets had taken advantage of the bucolic scenes and rendered their creation as a variation of the popular bucolic topoi. Some even gave their shepherds names that were directly lifted from Ovid’s Metamorphoses or other classical texts.Footnote 37 We also do not find a pastoral instrumental movement as in Johann Schelle’s Actus Musicus auf Weyhnachten from 1683 or even Handel’s Messiah or Bach’s Christmas Oratorio. Schütz’s setting begins in square common time and also the music of the lengthy first section of the evangelist (fifty-six bars long!) lacks allusions to bucolic topoi. The only moment when the composer leaves his pattern of strict syllabic declamation occurs in bars 36–7, when he graces the vocal line on ‘und wickelte ihn in Windeln’ (and wrapped him in swaddling clothes) with passing notes (see Example 2).

Example 2 Heinrich Schütz, Christmas Historia, Evangelist, bb. 36–8

What seems to be merely a musico-rhetorical painting of the wrapping of the little child also highlights one of the main foci of the whole piece, the care of the mother (and by extension, the whole holy family and the believer) for the little Christ Child. The following analyses of specific movements will make this clearer.

STRUCTURE AND TONALITY

The individual sections of Schütz’s Christmas Historia are self-contained, as were the sections in its predecessor by Rogier Michael. Each of the evangelist’s solos in Michael’s setting begins and ends in F, as do all the polyphonic interpolations. The harmonic progression (or rather, harmonic stasis) is predictable as the use of the simple cantillation model in the setting from 1602 suggests. By abandoning the traditional melodic model for the singing of the text for the evangelist, Schütz had more freedom to react to individual words or to capture the meaning of the text. Still, he mostly remains within the realm of F, beginning and ending each section of his historia either in F major or in closely related keys such as B flat major (before intermedi III and IV) or C major (before intermedi V and VI). All the intermedi begin in F and return to the home key at the end (which still left Schütz ample opportunities for more adventurous harmonic experiments within the intermedi). There are, however, two notable exceptions to this pattern. The gospel sections before intermedi VII and VIII end in an unexpected key. Before intermedium VII the evangelist ends on a D major chord, audibly conflicting with the F major in the following intermedium. And intermedium VIII is preceded by a turn towards A major. In both cases, the ‘foreign’ keys, both a third apart from the home key F, make the return to F in following intermedium an abrupt change.Footnote 38 Juxtapositions of third-related chords like this were often used by seventeenth-century composers to emphasise contrast in the text; for instance, in Monteverdi’s Nigra sum in the Vespers of 1610, where the phrases ‘Nigra sum’ and ‘sed formosa’ are not only logically opposite but also sonically clash in third-related keys (G vs. E, bb. 9–10). However, in Schütz’s Christmas Historia the third relations are not employed to establish a juxtaposition. The composer uses them for an interesting dramatic effect. Both intermedi VII and VIII report the words of an angel spoken to Joseph in a dream. Schütz invokes the otherness of this dream sequence by venturing (albeit briefly) into an unexpected, somewhat foreign key area. This is not radical harmonic shift, but given the established harmonic pattern in the historia, it is still remarkable and highlights the fact that the revelation of the angel takes place in a different reality, a different state of consciousness. Both dreams also return to the Kindelwiegen music from intermedium I, and Schütz’s ‘stage direction’ suggests that the rocking of the child could be performed here again.

THE PRACTICE AND TRADITION OF KINDELWIEGEN

It is not known whether and how the rocking of the Child was practised in Dresden during the early 1660s. Did the singers move their bodies, was a cradle placed on the altar or on the floor? While the Dresden sources remain silent about these questions, other sources from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries allow us to reconstruct some of the ritual practices of Kindelwiegen and the religious function of physical participation in this ritual.

The tradition of Kindelwiegen, the rocking of the cradle, has its roots in medieval folk piety; early sources for the practice date back to the twelfth century.Footnote 39 The cradle with a small puppet representing the Christ Child was usually located on top of the altar and moved either by hand or with an attached string. The practice had sometimes been criticised during the Protestant Reformation,Footnote 40 but at least in Lutheran territories is was still practised widely throughout the seventeenth century – not necessarily with a real cradle but rather pantomimic, by pretending to rock the child in one’s own arms. With the lack of a physical cradle, the human body was even more involved in the act, making the Kindelwiegen a physical representation of a religious ritual. Contemporary depictions of this practice are quite rare and they are frequently delivered with a critical overtone. However, the sources allow a reconstruction of some of the essential characteristics of this tradition. The Lutheran theologian Johann Martin Hommer writes in 1608:

And a chronicle from the Franconian city of Hof describes the following practice in the sixteenth century:

The negative views in the two quotations above are balanced by other, more positive assessments of the tradition. The Lutheran theologian Johann Mathesius (1504–65) stated in 1567: ‘Neither do the preachers object when the sexton and other children place the infant Jesus on the altar at Christmas, and when they sing lullabies to the child with the organ, with good pure songs . . . For we allow such innocent and harmless childlike customs to remain for what they are worth.’Footnote 43 It appears that Mathesius was not concerned about the practice or even the dancing; important to him was that this was done with ‘pure’ songs, that is, with songs that did not contradict the pure doctrine of the Lutheran Reformation.

Even more supportive of the practice of Kindelwiegen is a printed collection of Christmas songs by the seventeenth-century composer Ambrosius Profe (1589–1661). The collection was published in 1644, and while the music is lost, the title already gives a good idea of its content and function: ‘A Rattle at the Cradle of Christ, that is Several Christmas songs which can be used between and with the Magnificat at Vespers, in place of the Rotulae (as they were formerly called), with the rocking of the Christ Child. And they may also be sung without this at Christmas time.’Footnote 44 Profe, who was also very important for the importation and appropriation of Italian music in Germany during the mid-seventeenth century,Footnote 45 composed his songs as a replacement for the songs that had traditionally been used as interpolations in the Magnificat. While Profe’s compositions were not able to replace these older songs, the print attests to the fact that Kindelwiegen was not only an old tradition by the middle of the seventeenth century but even that new music was being created for this practice.

What both the positive and negative descriptions of the tradition have is common is that they portray a ritual that combines music (either for organ or songs) and a physical, corporeal activity, which can reach from the simple rocking of a real or imaginary cradle to actual dancing. As the chronicler from the early sixteenth century remarked, it was the ‘proportion’ of the hymn that not only resembled a dance but that actually incited the young boys and girls to dance. Dance during the liturgy was more common in the Middle Ages (and even the early modern period) than a modern observer might expect.Footnote 46 As Walter Salmen has pointed out, ‘dance rites were of great and varied significance in many churches of eastern and western Europe’, and he adds: ‘Dance customs in and around churches ranged from the devout bending of the knee, devotional gestures of prayer, processional steps, and the circumambulation of places of worship, to the dancing accompaniment of sequences and tropes, and round dances about the Christmas crib or around the altar.’Footnote 47

The rocking of the child during the retelling of the Christmas story has a longer tradition.Footnote 48 It goes back to medieval Christmas plays and survived the Reformation. A more recent musical setting of the nativity story from Breslau, composed about 1638, also incorporates the Kindelwiegen into the narrative action.Footnote 49 At several points during the Breslau Christmas play, the text mentions the Kindelwiegen, or rocking of the child: between the ‘Ehre sei God’ (Glory be to God) of the angels and the departure of the shepherds for the manger (‘Lasset uns nun gehen’); after the shepherds have seen the child; and after the shepherds have left the manger. The manuscript differentiates between ‘Wiegen zum Chor’ (rocking with the choir) and ‘Orgelwiegen’ (literally: organ rocking), which suggests that the organ played a lilting pastoral while the cradle with the child was being rocked.Footnote 50 The source also mentions the hymn Joseph, lieber Joseph mein, which had traditionally been the song that was sung during the Kindelwiegen.

The composer of the Breslau piece is not known and its relationship to Schütz’s Christmas Historia is not clear either; yet it shows that Schütz’s incorporation of the Kindelwiegen in the setting of the Christmas narrative followed an established pattern.

While the rocking of the Christ Child had originally developed as part of Christmas plays, in the sixteenth century it had mostly become part of the performance of the Magnificat on Christmas.Footnote 51 As Profe’s title page mentions, it was part of the singing of interpolated hymns between the verses of the (Latin) Magnificat. The hymns that were traditionally associated with this practice were Resonet in laudibus or and German equivalent Joseph, lieber Joseph mein. While both had late medieval roots, they remained part of numerous Protestant hymnals during and after the Reformation. They were still present in the Dresden Hymnal that was published in 1656, just a few years before the composition of the Christmas Historia.Footnote 52 Polyphonic settings of the songs were also readily available in collections such as Johann Walter’s Geistliches Gesangbüchlein (beginning with the edition of 1544) and others.Footnote 53

The Magnificat and the rocking of the cradle were part of the Vespers service on the afternoon of Christmas Day. While the details of the actual performance elude us, there is no question that the composer was familiar with this practice. When Schütz alluded to the ‘introduction of the cradle’ in the titles for three of the intermedi of his Christmas Historia, he was referring to a common and established practice that was already liturgically at home in the Vespers service, for which his piece had been composed. Schütz’s remarks are very specific about where the rocking of the child in the cradle should take place: in the first intermedium, which sets the announcement of the angel to the shepherds, and then again towards the end of the historia in intermedi VII and VIII, when the angel urges Joseph in a dream to gather his small family and first to leave for Egypt and then to return from exile. Why the physical action in these movements and not anywhere else? The first intermedium announces the great joy that is revealed to the shepherds but it also specifically mentions that they will find the child in a cradle in a manger. The rocking of the cradle becomes a physical commentary on the narrative. It is a mimetic representation of what is being said in the message of the angel.

The two later intermedi are more difficult to explain. Neither refers directly to the cradle or the manger. The speaker is again the angel but now he addresses Jesus’ father, Joseph. The choice becomes understandable when we consider the practice of Kindelwiegen in the sixteenth and seventeen centuries. The hymn that was primarily associated with this ritual was Joseph, lieber Joseph mein. Mary asks Joseph to help rocking the child. By extension, the congregation follows the example of Joseph: his physical action is mirrored by the congregants. The listeners become part of the staging of the narrative by following his example.

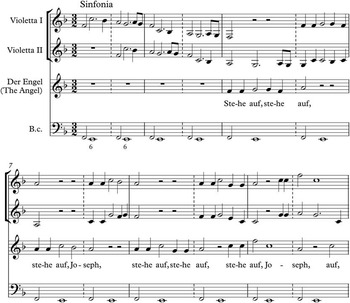

Musically, the three intermedi show clear similarities. For the most part, all of them are in triple metre, not unlike the hymn Joseph, lieber Joseph mein or the dance-like proportion the sixteenth-century chronicler had criticised.Footnote 54 As the title for the first intermedium explains, the rocking of the cradle should only happen ‘bisweilen’, occasionally. The score does not indicate when exactly but the music does provide hints. The movement begins with a short ‘Sinfonia’ featuring two ‘violette’ and basso continuo. The instrumental bass line has a rocking motif that continues when the soprano enters in bar 5. The triadic shape of the upper voices of the instrumental part is reminiscent of the melody of Joseph, lieber Joseph mein without quoting it directly (see Examples 3 and 4).

Example 3 Heinrich Schütz, Christmas Historia, Intermedium I, bb. 1–12

Example 4 Chorale melody Joseph, lieber Joseph mein

The ostinato-like rocking-motif ends in bar 21, leading to an extended cadential section that ends the first tutti section at bar 30. I would suggest that the rocking of the child lasts until this moment in the piece. The following bars feature the solo soprano only with the accompaniment of the basso continuo. The rocking motif returns at bar 36, when the instruments return as well. The remainder of the concerto is an alternation between solo sections (without the rocking motif) and sections featuring the whole ensemble, each one based on the distinct basso continuo motif. The result is a regular ritornello form, and within the suggested performance context, the Kindelwiegen creates a physical ritornello for the music.

The setting of the text in the intermedium is mostly syllabic. Exceptions are a rhetorical melisma on the phrase ‘allem Volk widerfahren’ (‘which will come to all people’) and a short melismatic gesture on ‘Windeln gewickelt’ (‘wrapped in swaddling clothes’), which directly refers back to the previous solo of the evangelist, which had the same words with a similar gesture.

In intermedium VII, Schütz establishes a greater contrast between the solo sections, which are all in common time, and the instrumental interludes, which are in triple metre. Three of the interludes feature the same musical motif as the first intermedium. In two cases, the rocking motif is inverted; instead of a short note followed by a long note, he now composes a long note followed by a short one. The difference is marginal; however, it shows Schütz’s interest in variety even on a small scale. While only the framing sections and one of the interludes feature the characteristic rocking motif, all the interludes do switch back to triple metre. They invite physical action as well (see Example 5).

Example 5 Heinrich Schütz, Christmas Historiae, Intermedium VII, bb. 1–12

The final intermedium states that the ‘cradle’ should only be introduced at the beginning. And it is only here (bb. 1–13, and a short interlude at bb. 17–21) that Schütz composes in triple metre; the rest of the movement stands in common time. The movement is also different insofar as the original rocking-motif is now inverted, with a long note on the downbeat and a short note on the off-beat.

The two earlier intermedi, and to a lesser degree the last one, are ritornello forms. Schütz not only composes a musical ritornello but the tutti sections feature a physical ritornello as well. The body of the listener becomes part of the ritornello structure. Its movement (almost dance-like) is a reaction to the texts in the solo sections, during which the body is inactive. The listener becomes a physical participant in the narrative, and thus also engages physically with the divine in the form of the newborn baby Jesus. The repetitive motion, combined with the simple music, might even have led to a short meditative state and a suspension of distance in time and space from the historical events. The performer not only rocks an imaginary child but is virtually transported into the stable of Bethlehem.Footnote 55

The liturgy at the court church in Dresden did not include liturgical dance; however, the physical action of the performers (and perhaps even the congregation) fits well with the elaborate and lavish celebrations of the Christmas services, as we have seen earlier. Images, vestments, music, and the rocking of the body created a multi-sensory experience of the meaning of Christmas. While liturgical dance proper was not part of this, the late Dresden court preacher Matthias Hoë von Hoënegg (1580–1645), who was still widely read in the second half of the seventeenth century, took a positive view of dancing in a sermon of 1614, as long as it remained proper and pure (similar to what Mathesius had written about the dance of the children on Christmas):

Hoë von Hoënegg does not mention the practice of Kindelwiegen even in his Christmas sermons, but the quotation shows that Dresden did not have a theological tradition that would have been opposed to dancing in general.

JOSEPH AND THE MEANING OF KINDELWIEGEN

The three intermedi that introduce the Kindelwiegen all have in common that they set text that was spoken by an angel; first to the shepherds and then to Joseph. But the focus of the practice of rocking the cradle is not so much on the angel but on the performer who creates a close, symbolic physical bond speaking with the newborn Jesus. The ritual symbolises the care for Jesus, which, in turn, establishes a corporeal and emotional connection with Christ. The text of the first intermedium admonishes the shepherds not to be afraid; but at the end of the text the shepherds are asked to find the child ‘wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger’. By rocking the imaginary child, the performer of Kindelwiegen puts himself in the stable, finds the child, and takes care of him by rocking him.

This enactment of physical and emotional proximity becomes clearer when we consider the hymn text that was commonly associated with Kindelwiegen, the song Joseph, lieber Joseph mein, the melody of which has also served as a model for Schütz’s intermedi I, VII, and VIII. In the first stanza, the Virgin Mary asks her husband, Joseph, to help her rock the child in the cradle:

By rocking the child, the participant in the ritual of Kindelwiegen became a helper of Mary and takes care of the child as his father and mother had done. The song Joseph, lieber Joseph mein became integral part of the ritual in the fifteenth century.Footnote 57 It was the same time when a cult around the father of Jesus developed as a supplement to the already widely accepted cult around the Virgin Mary. Compared to the veneration of the mother of Jesus, the Joseph cult developed rather late, as Rosemary Hale has shown in her study of Joseph as a model of motherly care in the late Middle Ages.Footnote 58 While the figure of Joseph already appears regularly in cradle plays in the early fifteenth century,Footnote 59 it was only later in the century that the cult became fully developed. The practice of Kindelwiegen became part of these rituals. Joseph’s model ‘exhorts others to “rock the cradle” privately and venerate the Child publicly and communally’.Footnote 60

While Joseph performs a maternal act, he also appears as the one who selflessly takes care of his family.Footnote 61 A theologian who laid the intellectual foundation for a re-evaluation of Joseph in the fifteenth century was the French scholar and poet Jean Gerson (1363–1429). He not only lobbied for an official feast day in honour of Joseph but also established the idea of Joseph as a model for guardianship, ‘as “lord” of the household’, who is ‘responsible for protecting and guarding the Child and his mother’,Footnote 62 and he explained:

Let us consider again who nourished the infant Jesus, led him to Egypt, disciplined him paternally. This was Joseph, his father. We must say, in short, that he accomplished all the necessary care of a good and loyal father. Even Jesus having been made by God honored Joseph as his father, his nourisher, his guide, his defender, his teacher and instructor.Footnote 63

While Mary was the model for the pious believer, Joseph was her first follower; and an imitatio Mariae could find its model in the father of Jesus. While the Protestant Reformation changed but never entirely abolished the veneration of the Virgin Mary, it also reconstructed the image of Joseph. Just as the Lutheran Reformation put particular emphasis on the family and the Christian household, Mary and Joseph become an example for family life,Footnote 64 in which Joseph still appears as a model for the father and as helper and nurturer.Footnote 65 Examples of this continuing view of Joseph in German Lutheranism are the Christmas sermons by Hoë von Hoënegg. In his sermon published in 1614 the preacher calls Joseph a ‘trewen Beystand vnd Pflegevater’ (faithful helper and foster father);Footnote 66 and in another sermon from the same collection, he describes Joseph as a model for a good stepfather:

The sermon shows that Gerson’s view of Joseph, even within a different theological context, was still popular. And also popular was the hymn that expressed Joseph’s care for the Christ Child. This view of Joseph within the cult around Mary and the Child explains the use of the Kindelwiegen in the final two intermedi of Schütz’s Christmas Historia. In both of them, Joseph is told by an angel in a dream to take his family; first to protect his son from being killed by King Herod and then to bring his family back from Egypt to the Holy Land. Joseph appears as the protector, as characterised by both the fifteenth-century theologian Gerson and the seventeenth-century preacher Hoë von Hoënegg. The use of Kindelwiegen in the last two intermedi again symbolises the care for the Christ Child in which the believer participates by rocking the cradle. In intermedium VII, the rocking motif frames the whole movement and also returns in one of the instrumental interludes. In the final intermedium, the motif only appears towards the beginning, when the angel admonishes Jesus’s father to take his family. Schütz abandons it when the text reports the death of the king and the return of the family. The focus of the text has shifted from the caring foster father so that a symbolic enactment of his care seemed less warranted.

The use of Kindelwiegen in Schütz’s historia, even though it was a popular folk ritual, had a defined purpose within the narrative and dramatic framework of the piece. The body of the performer symbolically enacts what the text relates. The rocking of the child becomes a physical ritornello within the intermedi, and the corporeal action becomes part of the rhetorical and interpretative function of the music.

THE BATTLE FOR CHRISTMAS AND THE END OF A TRADITION

Some of the descriptions of Kindelwiegen quoted earlier already showed that the practice was not uncontested. However, the tradition remained strong until the second half of the seventeenth century. Most cities in Lutheran Germany practised Kindelwiegen as well as other rituals that commemorated the birth of Christ with a celebration of corporeality.Footnote 68 In fact, the rocking of the cradle was only part of a number of traditions that involved the physical actualisation of the Christmas story. Another tradition was the so-called ‘Heilige Christ’ or ‘Christmas Larvae’ (Christmas Spirits). Jesus and a host of angels as well as other characters went from house to house, examining the children, and delivering either gifts or punishment. Jesus and the angels were dressed in costumes and with them often came a group of other characters, such as shepherds and especially a dark fellow, Knecht Ruprecht, who was responsible for punishing those children who had not diligently memorised their catechism. The tradition had grown out of the medieval Catholic rituals around St Nicholas, and Ruprecht was originally the side-kick of the saint. The Protestant tradition had simply paired him with the ‘Holy Christ’ (Christkind), who was now the bringer of the Christmas presents.

The tradition was a carnivalesque folk ritual. People dressed up, roamed the streets, celebrated not only the feast with their bodies but in numerous cases celebrated corporeality. The feast threatened public and also religious order. In a novel of 1673, the playwright Christian Weise describes one of these rituals quite vividly:

The ‘Heilig Christ’ plays and physical enactments of the Christmas story came under attack during the 1670s, in the wake of religious reforms that emphasised interiority and quiet devotion. In 1674 the theologian Johann Gabriel Drechssler published a treatise against the tradition, both in Latin and an abridged version in German.Footnote 70 A second, expanded version appeared in 1677,Footnote 71 and another edition in 1683.Footnote 72 Finally, the German translation alone was published in 1703 in the short-lived Leipzig journal Deliciarum Manipulus.Footnote 73 Drechssler’s treatise was frequently quoted by other authors who aimed to abolish this practice as well. Especially in the 1680s a large number of books and treatises appeared that criticised the established Christmas traditions. As a result, the practices were abolished in most German cities in the 1680s and 1690s. Attempts to revive them occasionally even led to arrests, as in Arnstadt in the early eighteenth century.Footnote 74

What Drechssler and others criticised were only the physical celebrations and the excesses. In fact, Drechssler saw some benefits in setting the Christmas story in a somewhat dramatic way, as long as the limits between musical and physical representation were maintained. He had nothing against dramatic plays (omnes actus dramaticos), comedies, representations of sacred histories, and sacred musical dialogues (dialogos sacros musicos).Footnote 75 His goal was only to abolish the abuse, and he criticised the problematic (if not heretical) theological underpinnings of contemporary plays in order to counteract a profanisation of Christmas.Footnote 76 In other words, while the carnivalesque excess had to be prohibited in Drechssler’s view, accurate and serious adaptations of the biblical narrative were not objectionable. On the contrary, it could be desirable to channel the energy from the excessive Larvae Natalitiae to more appropriate plays or dialogos sacros musicos.

The Pietist theologian David S. Büttner (1660–1719) argues in a similar vein in a treatise against the Christmas plays printed in 1702. He concedes that musical dialogues based on biblical texts were inherently different from the Christmas Larvae since performers were not dressed according to their characters and therefore could not be confused with the real biblical characters:

Büttner does not see a problem in the musical setting of the biblical narrative, nor in the representation in dialogue of different characters in the music. What he criticises is the ‘staging’, which leads to a suspension of disbelief and therefore to an identification of the characters with Christ and his angels. However, the tradition of Kindelwiegen operated with a certain suspension of disbelief. The performer physically enacted the rocking of the Christ Child in the cradle and did not only sing about it. While the Kindelwiegen was not under direct attack by Büttner or Drechssler, the tradition was affected as well. It was a physical celebration of the events around Christmas. The rocking of the cradle could be viewed not only as a symbolical act but as something that was done for the little baby Jesus – a view that had already been rejected as pagan by Martin Hammer in 1608.

The change in the celebration of Christmas is well documented in Leipzig. In 1681 the city abolished the Christmas Larvae and in 1702 the Kindelwiegen during hymns such as Joseph, lieber Joseph mein was prohibited as well. Faith was supposed to be an internal, not a physical, act. The theological focus of Christmas shifted towards the presence of Christ in the human heart in a mystical union between Christ and the believer, not a corporeal (and thus external) realisation of parts of the narrative.Footnote 78 The Larvae Natalitiae with their rituals and practices were occasions for carnivalesque behaviour, as described by the literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin.Footnote 79 Bakhtin differentiates between several forms of folk culture in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. One form was comprised of ‘Ritual spectacles: carnival pageants, comic shows of the market place’. The Christmas masks greatly resemble these pageants, albeit on a much smaller scale. An essential part of Bakhtin’s understanding of carnival (and the carnivalesque) is the physiological and bodily experience of the spectacle.Footnote 80 The physical experience of religiosity during the seventeenth century was increasingly replaced by a purely spiritual piety.Footnote 81 With the abolishing of the Christmas plays, the Christmas rituals also lost a participatory element. As Bakhtin points out: ‘Carnival is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it, and everyone participates because its very idea embraces all the people.’Footnote 82 While Bakhtin describes practices in Catholic areas, his observations still apply to Lutheran practices, which had survived the Reformation and were only questioned in the seventeenth century.

The metaphors and language for the new understanding of Christmas had already existed earlier. Settings of texts that celebrate the union of Christ and the believer were already popular throughout the seventeenth century and even in the works of Schütz. But this view now became more prominent, while the carnivalesque folk rituals were being suppressed. Physicality in religion was relegated to a metaphorical stratum. Meditations on the spiritual union with Christ could borrow images that were highly physical, and even erotic. But this came at the price of their complete separation from actual physicality.

Heinrich Schütz’s Christmas Historia, composed around 1660 and published in 1664, was printed at the end of a tradition that allowed the physical enactment of religiosity in German Protestantism. Virtually at the same time as Schütz’s piece was prepared for print, a prolific author in Leipzig, Johannes Praetorius (1630–80), handed his printer the manuscript for a book, Saturnalia, das ist, Eine Compagnie Weihnachts-Fratzen, oder Centner-Lügen und possierliche Positiones (Saturnalia, that is: a collection of Christmas-grimaces, or heavy lies and cute ideas),Footnote 83 which condemned the Christmas Larvae as being pagan and Catholic (almost equally appalling to a Lutheran author shortly after the Thirty Years War) and which labelled the tradition of Kindelwiegen as ‘popish and foolish’. Praetorius’s book summarises the criticism of these folk traditions, and within less than two decades they began to disappear all over Lutheran Germany.

According to Schütz’s instructions in the print from 1664, the inclusion of the cradle was optional. The music could easily have been used even after the abolition of the Kindelwiegen. However, Schütz composed his music in a way that not only accommodated the use of the cradle but the prominent triple metre sections also invited a physical response. Schütz composed movements that contained not only a musical ritornello but also a physical ritornello. The physical rocking of the Christ Child in the cradle was a symbolic enactment of the role of Joseph, who took care of the child on behalf of Mary. By rocking the cradle, the performer not only became part of the narrative but also symbolically established an emotional bond with the divine Child. Just as Baroque danceFootnote 84 and Baroque opera were a rehearsal and reflection of social order, the rocking of the child in Schütz’s Christmas Historia symbolically connected the performer with the newborn Jesus. This function of the Kindelwiegen becomes clear in the way Schütz employs it in his settings at those moments, when the text talks about the care of Jesus’ parents and in particular of his stepfather, Joseph.

The physical act of Kindelwiegen in the Christmas liturgy in Dresden in the 1660s was firmly embedded in other communicative rituals: spoken word, music, liturgical vestments and paraphernalia, and visual art depicting the Christmas narrative and other parts of biblical history. By participating in the Kindelwiegen, the body of the performer became part of this multi-sensory, ritual interpretation of the Christmas story. While some of these ritual practices continued, others were abandoned in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as obsolete or even contradictory to current beliefs, such as ornate vestments and the rocking of the child in the cradle. Especially if these traditions maintained a connection to medieval and Catholic predecessors, they seemed to threaten Lutheran identity and were discontinued.Footnote 85 The critique of what was perceived as ‘Catholic’ rituals was already older, also in Dresden. In 1617 the court preacher Hoë von Hoënegg criticised Catholic practices such as processions, parades with wooden effigies, and other rituals; ‘instead, we shall celebrate this feast [the 100th anniversary of the Lutheran Reformation] in spirit, we shall speak amongst each other of psalms, canticles and sacred songs, we shall sing and play to the Lord in our hearts’.Footnote 86 Yet, in spite of such criticism, the Lutheran church not only maintained some of the rituals but also established some new ones. The major shifts in the rejection of rituals in Lutheranism did not happen until later in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

What does that mean for the musical history of settings of the Christmas narrative? Already in 1683, Johann Schelle, cantor at Leipzig’s St Thomas church, composed a setting of the nativity story that did not refer to the old practice of Kindelwiegen. Instead, it relied exclusively on the musical setting of the biblical text and reflective hymns. Instrumental settings in a lilting triple metre now appear in two sinfonias (‘sonata pastorella’), played by reed instruments (Schryari), which sonically invoke the bucolic sphere. The closeness to Jesus is not realised physically but metaphorically by inviting the Christ Child to make the believer’s heart his bed (no. 16: ‘Ach mein herzliebes Jesulein, mach dir ein rein sanft Bettelein’). The body of the believer is still the locus of human–divine encounter, but now this encounter is not realised in a physical act but purely linguistically.

On a superficial level, it would be possible to draw a direct connection between Schütz’s Christmas Historia and Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio BWV 248 (1734). The ‘folk-like’ simplicity that Schütz interpreters such as Hans Joachim Moser had admired in the composition from the 1660s can be found in Bach’s music as well. And movements in BWV 248 like ‘Schlafe, mein Liebster’ (Sleep, my Most Beloved, no. 19) feature a rocking motion that has often been compared and related to the old practice of Kindelwiegen. However, Bach metaphorically alludes to the physical rocking of the cradle while Schütz’s music invites us to enact it. The human body in Bach’s oratorio is only the locus for the spiritual encounter with the divine, not for a physical encounter. What is externalised in Schütz is internalised in Bach. It is the difference between a dance to be danced and a stylised dance in a Bachian keyboard suite. The changes in the understanding and celebration of Christmas in the later decades of the seventeenth century with the abolition of the Christmas Larvae as well as the Kindelwiegen turned the celebration of the body into a celebration of the heart.