Marquis Yi of Zeng 曾侯乙 (d. c. 433 b.c.e.) was keenly interested, if not obsessed, with displaying his power and wealth. Rulers of all periods and places have shared his concern, but the Marquis's resting place stands out as particularly splendid among excavated tombs of Chunqiu 春秋 (770–475 b.c.e.) and Zhanguo 戰國 (475–221 b.c.e.) nobles.Footnote 1 Interring all of his vessels, weapons, and musical instruments, not to mention the Marquis himself along with 21 attendants and a dog, must have been an impressive affair, an elaborate spectacle that required extensive planning and the participation of many officials and dignitaries. We are thus extremely fortunate that scribes recorded the Marquis's funeral procession on bamboo strips, and then placed them in his tomb along with all of the other items. The strips, the earliest excavated texts written on bamboo currently known from China, provide a rare, detailed look at a funeral cortège of magnificent size and splendor.

Though several important studies of the strips have been published, most scholars have ignored them, for understandable reasons: their organization is extremely complicated; the proper strip sequence remains a matter of debate; scattered transcription problems prevent smooth reading; and even successfully transcribed characters elude our comprehension, since they refer to barely known or completely unknown people and places, as well as to details of early Zhanguo material culture that we can only begin to understand.Footnote 2 Beyond these palaeographical issues, however, lies a classification problem: most secondary works, following categories extrapolated from descriptions in the Yi li 儀禮 (compiled c. late third century b.c.e.),Footnote 3 have identified the strips as a qiance 遣冊 (“inventory of sent items” or, more commonly, “inventory”) or fengshu 賵書 (“funeral gift list”), or some combination of the two.Footnote 4 Inventories and gift lists are some of the most common texts we have from Zhanguo, Qin 秦 (221–206 b.c.e.), and Western Han 漢 (206 b.c.e.–9 c.e.) tombs, and scholars have focused on comparing the Zeng strips to such texts in order to detect shared characteristics in the inventory genre. The strips, however, are not an inventory of the tomb: they do not itemize individual goods that can be matched with items in the tomb, nor do they mention any of the tomb's musical instruments and bronze vessels.Footnote 5 Whether or not the strips were a precursor to later inventories is one possible question to be posed of the documents. This line of inquiry, however, ignores an arguably more important question: what functions did the strips serve in the context of the Marquis's funeral?

This article attempts to answer this question. It begins with a fresh overview of the strips, including their content, format, and presentation. Descriptions on the strips tell us who and what participated in the cortège, and in what manner, valuable information for understanding the material and political import of the procession for the state of Zeng. The article then moves on to a discussion of the organization and performance of the cortège by Zeng state officials and visiting dignitaries. The evidence suggests that the strips comprised two separate texts, which scribes composed in stages in order to first organize and then oversee and verify the procession's execution. The texts are thus both the products and key components of an elite Zeng political spectacle. A subsequent section compares the Zeng texts with select inventory texts in order to argue that the former had as much to do with Zhanguo politics as they did with notions of the afterlife, without denying the intimate links between the two. The director of the procession used the strips within the context of a funerary cortège that functioned in various ways to demonstrate the status, wealth, and power of the Marquis and his realm. We have no shortage of evidence from Zhanguo, Qin, and Han texts attesting to the importance of funerals and processions in early Chinese political culture, and we can surmise that funeral processions were important for ensuring the smooth transfer of power within Chunqiu and Zhanguo states. The strips provide a unique, direct perspective on how ruling houses employed these political spectacles, and demonstrate the key role texts could play in their organization and execution.Footnote 6

Location and Condition of the Strips

The Zeng texts were interred in the northern chamber of Marquis Yi's tomb. Measuring 4.25 (north-south) x 4.75 (east-west) m,Footnote 7 the chamber, while the smallest of the four in the tomb, contained a staggering amount of weapons, carriage parts, and horse tack.Footnote 8 Excavators found the strips mainly in two piles in the northwest quadrant of the chamber, pressed under piles of lacquer armor.Footnote 9 Small numbers of strips were also found scattered towards the middle of the chamber, slightly to the west of the center.

The dimensions, particularly the length, of the intact strips are impressive: 70–75 cm x 1 cm.Footnote 10 According to the excavation report of Marquis Yi's tomb, two sets of gaps between characters on the upper and lower portions of the strips indicate that they were bound together before scribes wrote on them.Footnote 11 The binding threads had decayed prior to excavation, with many of the strips out of order and broken. The excavators reported a total of 240 strips found in the chamber, not including “blank” strips.Footnote 12 Qiu Xigui 裘錫圭 and Li Jiahao 李家浩 recombined the broken strips together with the larger, more intact strips, creating a single text totaling 215 strips that they numbered sequentially. References to strip numbers will refer to this sequence of 215 strips.Footnote 13

The Content of the Strips: Describing the Funerary Cortège

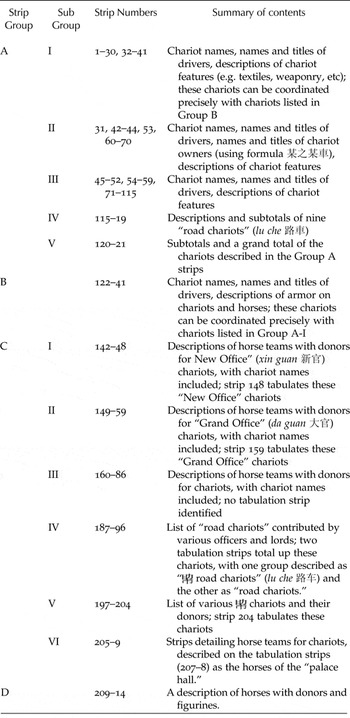

Two general characteristics of the strips provide organizational structure. First, the chariots used in the funeral procession are the focus of description throughout. Different sections of the texts detail different features of the chariots (see below), but the group of chariots they refer to is the same.Footnote 14 Second, the scribes who wrote the strips conceived of these different features as important categories, since some strips provide tabulations that label and sum them up (see Appendix A for translations of the tabulation strips). Largely following these features, Qiu and Li divided the strips into four categories, labeled A, B, C, and D. Ishiguro further divided groups A and C into subcategories, providing a more nuanced picture of details in content that distinguish strips within these groups (see Table 1). Note that all of these grouping schemes assume that the strips comprised a single text. As will be discussed in the next section, however, markings on the strips and differences in format and calligraphic style suggest otherwise.

Table 1: Strip Group Divisions, following Ishiguro

Ishiguro's analysis confirms a fact, already mentioned above, that emerges from a close reading of the strips: we can identify the same chariots across strip groups. The strips describe different features of the same chariots. The closest matches are between strips in Ishiguro's group A-I (strips 1–23, 25–29, 32–33, 36–41), group B (strips 122–37), and certain strips in groups C-I and C-II. Following one chariot across these groups will help illustrate how descriptions in many of the Zeng strips complement each other. Our guide will be the “grand forward banner chariot” (da pei 大旆) driven by an official named Jian 建. We know that the description of Jian's chariot comes on the first strip for two reasons. First, the entry describing Jian's chariot comes immediately after an opening line that provides a composition date for the strips (discussed below). Second, the backside of the first strip contains a title, a paraphrase of the opening line from the description of Jian's chariot. That description begins as follows:Footnote 15

右![]() Footnote 16 (令) 建所

Footnote 16 (令) 建所![]() (乘) 大

(乘) 大![]() (旆):雘輪,弼,

(旆):雘輪,弼,![]() (鞎),

(鞎),![]()

![]() ,畫

,畫![]() Footnote 17,

Footnote 17,![]() 韌,

韌,![]() 韔,

韔, ![]() (貘) 聶,

(貘) 聶,![]() (豻) 𣧻

(豻) 𣧻

The Director of the Right Jian drove a grand forward banner chariot. It had: red wheels; woven screens of bamboo and leather, with jade pendantsFootnote 18; painted hides; silken cordsFootnote 19; a tiger-skin bow case with panda-skin fringe; a quiver made of wild dog furFootnote 20…(end of strip 1)

The description of items carried on Jian's chariot extends to the top of the fourth strip. The passage mentions different fabrics and silks, as well as a wide array of weaponry, including spears and swords.Footnote 21 These descriptions are quite detailed; we even read of designs on the pennants flying from Jian's halberds and spears.Footnote 22 Group A strips all follow this format, with some variation. They give the name or title of the driver and the type of chariot that he commanded, followed by a list of decorations and weaponry. Some entries (Ishiguro's group A-II) describe a person driving a chariot donated by somebody else.Footnote 23 The repeated reference to drivers shows that the strips record the participants and chariots used in the procession itself. They might even loosely follow the order of chariots in the cortège, though we cannot assume that all of them drove along in a single file in the sequence given in the strips.

Moving into the B strips, we find Jian and his grand forward banner chariot, again first in the lineup of entries:

大![]() (旆):二真楚甲,索 (素),紫

(旆):二真楚甲,索 (素),紫![]() Footnote 24之

Footnote 24之![]() (縢)…

(縢)…

[The people inFootnote 25] the grand forward banner chariot wore two sets of Chu armor, painted white,Footnote 26 with purple cords… (strip 122)

The B strips follow the same chariots in the A strips, though the first five entries in the B strips do not give the names or titles of the drivers seen in the A strips. Starting with the fifth entry, however, we do read names, in the same order as in the A strips. The rest of the B strips follow the pattern seen in the grand forward banner chariot entry, noting the style of armor worn (either Chu or Wu 吳), and their different styles and colors of cording and leather. The strips also give similar descriptions of the horse armor, including their style and materials, and a few other design specifics.

Following Jian into the C strips we come to an entry describing the horse team that pulled his chariot, again right at the beginning:

莆之 Footnote 27 為左驂,慶 (卿) 事 (士) 之![]() (騮) 為左

(騮) 為左![]() (服),蔡齮之騍為右

(服),蔡齮之騍為右![]() (服),

(服), ![]() (

(![]() ) 君之騏為右驂。外新官之駟馬。大旆。

) 君之騏為右驂。外新官之駟馬。大旆。

The horse of Pu pulled at the outer left of the team; the roan horseFootnote 28 of the Ministerial OfficerFootnote 29 pulled at the inner left; the piebald horse of Cai Yi pulled at the inner right; the black horse of the Lord of Ji pulled at the outer right. This was the four-horse team of the Outer New Office. It pulled the grand forward banner chariot. (strip 142)

The strip presents three important pieces of information: the names of the donors of the horses that comprise the chariot team; the positions of the horses in the team; and the name of an office to which the chariot team has been assigned. All of this information is important for understanding how the procession was produced and how it functioned as a political spectacle. The following section, which discusses these issues in some detail, will thus revisit the C strips. For now, it is enough to emphasize that all of the C strips continue to take the chariot as the primary descriptive unit. As we will see, this method of noting donors is quite different from anything known from texts customarily labeled as inventories or gift lists.

Jian and his grand forward banner chariot do not appear in the D strips. They list different groups of like items in a manner very similar to the inventory texts discussed below. The strips enumerate horses and their donors, but their role in the procession remains unclear.Footnote 30 They also list what the transcription and editorial team have argued were “figurines” (yong 佣). This interpretation has been disputed, however,Footnote 31 and excavators did not find any figurines in the Marquis's tomb. It is possible that figurines were placed in accompanying burial pits, but on present evidence it appears that no such pits exist.Footnote 32 Finally, two much shorter strips that Qiu and Li transcribed separately from the rest were also found in the tombFootnote 33:

![]() 軒之馬甲

軒之馬甲

Armor for a horse of a battleFootnote 34 chariot

Qiu and Li argued that these were tags, which must have been attached to many of the interred items.

The Organization and Performance of the Cortège

The content reviewed above shows that officials and dignitaries honored Marquis Yi with an opulent procession, and scribes described it in detail using a relatively consistent format, noting different features of the overall spectacle. But how was such a procession organized and performed? How might it have been viewed and understood by onlookers and participants? An analysis of the content and a detailed look at the organization and format of the strips can address these complicated questions, if not fully answer them. This section will advance two points. First, evidence from the strips shows that the director of Marquis Yi's funeral combined materials donated from a vast geographic area, following an organizational logic, in order to create an original funerary spectacle. Second, the organization and format of the strips demonstrate that they in fact comprise at least two texts, which were essential to both the production and performance of this spectacle.

We return to the C strips to address the first point. As noted above, in most cases, we do not know the identity of the horse donors listed on the strips. They are presumably people of considerable importance: note that one of the donors given for Jian's chariot team is the lord (jun) of Ji ![]() . We know nothing about Ji,Footnote 35 but his name appears repeatedly in the strips as a horse and chariot donor. The following table lists only the individuals who donated chariots, and provides the number of horses and chariots that each contributed:

. We know nothing about Ji,Footnote 35 but his name appears repeatedly in the strips as a horse and chariot donor. The following table lists only the individuals who donated chariots, and provides the number of horses and chariots that each contributed:

Table 2: Chariot Donors and the Numbers of Horses and Chariots They Donated (strip numbers given in subscript)

The table does not list the many people who gave horses but no chariots. Some of those names suggest an even wider array of close relationships between Zeng and other states, including Chu.Footnote 39

Fortunately, among the chariot donors, we can gain some sense of the import of these relationships, since it is possible to identify with some degree of certainty the locations of three chariot donors: the Lord of Pingye, the Lord of Yangcheng, and the Duke of Luyang. People holding these titles are found in received texts, which record that the King of Chu gave them fiefs, where they established themselves as local rulers.Footnote 40 A recently excavated tomb, found partially looted, near the village of Geling 葛陵 in Henan 河南, has yielded weapons and strips inscribed with the title “Lord of Pingye” (Pingye jun 坪夜君).Footnote 41 Scholars have dated the tomb to the fourth century b.c.e.Footnote 42 Even if this is not the same “Lord of Pingye” seen in the strips, the discovery at least enables us to pinpoint the location of Pingye with some certainty. Like Yangcheng and Luyang, it is hundreds of kilometers away from the Marquis of Yi's tomb towards the north and east (see Map 1).

Map 1: Location of Luyang, Yangcheng, and Pingye relative to Zeng

Clearly, the Marquis was important enough to attract dignitaries, or at least goods donated by them, from distant areas (we can only know for sure that the drivers listed in the A strips actually attended and participated in the funeral procession; other dignitaries, including the donors, were likely present, but there is no way to prove this supposition). These people also donated just as many or more chariots than the “king” (wang 王) and “heir” (taizi 太子), who donated three chariots each. Qiu and Li plausibly claim that these figures were the king and prince of Chu.Footnote 43 If they are correct, then we can conclude that these lords from the northeast in total contributed more materials used in the funeral procession of the Marquis than the Chu royal house.Footnote 44

The procession could not have occurred without these donations from nobles, but the director and organizers of the cortège ultimately controlled how they were used. We have already seen that Jian drove a chariot harnessed to horses contributed by several donors. Donors thus did not contribute intact horse teams; the procession director mixed and then matched horses to chariots.Footnote 45 As seen in the table above, for example, the Fu Official contributed two horses and one chariot, but the chariot was pulled by two horses given by the Lord of Pingye. Meanwhile, the Fu Official's horses pulled a chariot contributed by the Duke of Luyang. We see the same dynamic in A-II strips that specifically note a chariot driven by somebody other than the owner:

哀立 ![]() (馭) 左尹之

(馭) 左尹之![]()

Ai Li drove the battle chariot of the Administrator of the Left… (strip 31).

Individual donors appear not to have had much say in how the procession director used the chariots and horses they donated. They certainly did not require that their horses pull their chariots in the procession. Rather, the director and his assistants decided how to combine all of the different items together. The organizers thus planned and controlled the tiniest details of the cortège. Surely there was a logical system or a design scheme behind their decisions, even if it escapes us today.Footnote 46

The tabulation strips in fact do hint at such a system. In the strip describing the horse team pulling Jian's chariot, Jian was characterized as being a member of the “Outer New Office” (wai xin guan). A related term appears in the strip tabulating the C-I strips:

■凡新官之馬六乘

In sum there were six chariots with horses of the New Office. (strip 148)

The difference between the “Outer New Office” and “New Office” is unknown; indeed, the meaning of “New Office” is unclear, as is “Grand Office” (da guan 大官) the category under which the C-II strips are tabulated in strip 159.Footnote 47 Ishiguro argues that all of the officers listed on the strips are Zeng officials, and that these categories divide up the Zeng bureaucracy. There is good reason to doubt that the strips give sufficient evidence to prove this hypothesis,Footnote 48 but we can still surmise that the categories provided a basis for the organization of the procession. For example, the first two C-I “New Office” chariots are also the first two chariots described in the group A chariot entries. The fifth chariot is found under the “Grand Office” category. The organizers clearly did assign particular meanings to chariots and arranged them in a sequence accordingly. If we knew what these categories meant, and if we assumed that the order in which chariots are listed in the A strips followed the order in which they were used in the funeral procession, we might be able to understand the logic behind the organization of the cortège. This appears to be impossible, but the evidence from the strips does at least assure us that such an organizational scheme existed.

Differences in the layout of the strips corroborate this evidence for elaborate planning prior to the procession. The most prominent distinction is between the A and B strips on the one hand and the C strips on the other. The chariot descriptions on the former extend across multiple strips, with each entry separated from the next by a stretch of blank space. Moreover, square black blots extend across the width of the strips either end or begin the A strip entries (the black squares in the transcriptions in this essay indicate these blots). If the scribe had enough room to start a new entry on the same strip as a just completed entry, he would leave a blank space, add a blot, and then start the new entry. If not, he would end the completed entry with a blot and leave the rest of the strip blank (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Blots on A Strips (strips read from upper left to lower right)

This coordinated variation in ending and beginning punctuation, as well as the fact that the chariot descriptions on the A and B strips continue across multiple strips, shows that a scribe composed the descriptions of the drivers, chariots, and horses in the procession at the same time.Footnote 49

The same cannot be said with certainty of the C strips, since the descriptions of chariot teams do not extend across multiple strips. Scribes fit the horses, donors, and chariot names for each individual chariot onto a single strip. They thus must have composed the C strips separately from the A and B strips. Differences in handwriting between the two further support this division (see Figure 2).Footnote 50

Figure 2. Format of the C Strips

We cannot say for sure which group was composed first. Nevertheless, the format and content of the C strips make them read like a series of planning documents. Chariots and horses, after all, were the basic raw material that the procession director had to work with when he started organizing the cortège. Upon receiving the donated chariots and horses, he must have first decided which horses would go with which chariots. He did this by arranging the horses and chariots together according to the logical scheme discussed above.Footnote 51 He also had to assign drivers to chariots. Once he had recorded these chariot team arrangements, he could then put the chariots into a procession sequence and record all of their decorative features, weaponry, and armor. This step must have been last, since as already noted some level of planning and training must have been required to ensure that horse teams would work well together pulling their chariots.Footnote 52

A closer look at the A and B strips that describe the procession reveals marks that not only further distinguish these strips from the C strips, but also demonstrate that scribes marked the A and B strips after they had completed the descriptions of the drivers, chariots, and horses. A series of oblong, ovular dots that occur only on A and B strips, the marks are not regularly shaped like the square blots found on the A strips. As seen in the close-up of strip 13 (Figure 3), they often have tails at the bottom, left by the trailing end of the scribe's brush stroke.

Figure 3. Counting Mark on Strip 13

Moreover, unlike the square blots, the marks are irregularly spaced within the text, crammed in between the characters and occasionally touching them. A scribe must have applied such inconsistently rendered and applied dots after the text was already written. Since they almost always lie next to the name of a chariot driver or the name of the chariot itself, they seem to be counting marks that note individual chariots. Possibly, the same scribe who made the counting marks finished by writing up the tabulation strips that come at the end of the A and B strip groups.

Indeed, differences in format and character size between the A and B tabulation strips and the main text show that the tabulations were written at a different time and perhaps by a different scribe (see Figure 4). Certain portions of the A and B tabulation strips in particular were likely written after a scribe had composed the entire text and after the counting marks had been added. These are the two “grand total” (da fan 大凡) statements that come at the end of the A and B tabulation strips, after a breakdown of the different subcategories of chariots and armor. The A strip “grand total” tabulation will serve as an example:

■ 大凡四十乘又三乘。 至紫(此)。

In total there were 43 chariots. They came here. (strip 121)

These “grand totals” are not seen in the C strips. They are obviously less discriminating than the careful notations of subcategories that immediately precede them. Their lack of specificity matches the oblong tallying marks of the A and B strips in spirit and execution, supporting the idea that a different scribe recorded both after the main descriptions of the drivers, horses, and chariots on the A and B strips were composed. The final statement on the grand total A tabulation strip, zhi ci 至紫, is crucial for understanding how the stages of composition fit into the performance of the procession itself. “Here” could presumably refer to Zeng, but it cannot refer merely to the Zeng polity, since the preponderance of evidence from the content and format of the strips shows that the A and B strips were composed after the chariots and other items had already been donated, and after the cortège director had reorganized them. “Here” must therefore refer to the funeral procession grounds or even to the tomb itself.Footnote 53

Figure 4. Comparison of character size and spacing between A-I strip and A-V tabulation strip

We are now in a better position to understand the opening statement on the first strip, which describes when and how the text was composed.

大莫 ![]()

![]() (陽)為適豧之春,

(陽)為適豧之春,![]() = (八月)庚申𩊄 (胄) 𧻿 執事人書入車。

= (八月)庚申𩊄 (胄) 𧻿 執事人書入車。

On the gengshen day of the eighth month of the year when the Great Mo'ao Yang Wei went to Fu in the spring, the armory officer recorded the chariots that were received. (strip 1)

The differences between the A and B strips on the one hand and the C strips on the other demonstrate that the armory officer could not have written all of the Zeng strips at the time of the procession. Moreover, the great detail of the chariot entries discussed in the previous section would have been impossible to record as the procession passed by. Incorporating all of the observations made above, a more likely scenario for the production and performance of the cortège is as follows: after the director of the funeral procession received all of the donated chariots and horses (this must have taken some days, if not weeks), he and his organizing team combined them into chariot teams, taking time to train the horse teams as needed. Once these teams were complete, scribes recorded them on the C strips; these were the “received chariots” and together constituted the first text. The armory officer then recorded these received chariots in the desired order, carefully noting all of the important items and decorations on each chariot in the A strips and the armor on the B strips. Then the procession was executed. While it went on, a scribe (perhaps the armory officer himself or somebody else) sat to the side, with the A-B text unrolled in front of him.Footnote 54 As each chariot passed by, he made a mark next to the appropriate entry, verifying its participation in the Marquis's cortège and by extension the accuracy of the descriptions of fittings, weaponry, and armor. When the procession was over and the chariots had arrived at the funeral procession grounds or the tomb, he counted up his marks and added the “grand total” tabulations, closing with a note that the chariots “went there” (zhi ci 至紫). The scribe thus tabulated and verified not just the number of chariots but also the performance of the chariots and drivers in the cortège. “This happened,” they say. The texts became a testament to the organization and execution of the entire procession, and the presence of all of the donated chariots, horses, and opulent materials, as well as the participation of officials and dignitaries.

Inventories, Gift Lists, and the Zeng Texts

Why did the procession directors write these strips and use them to verify the performance of a ceremony at the Marquis of Zeng's funeral? Surely there were a variety of motivations, practical, political, and religious, including beliefs about the afterlife. Comparison with texts commonly understood as inventories or gift lists, which often do show an explicit concern with the afterlife, however, suggests that this final concern is not as prominent in the Zeng strips. The inventory and gift list textual genres are now well established in studies of excavated texts from Zhanguo, Qin, and Han, and details of such finds are common in archaeological reports.Footnote 55 In the 1950s, archaeologists who first began to analyze excavated texts enumerating lists of goods immediately identified them as the bamboo slips (ce 策) described in the “Ji xi” 既夕 chapter of the Yi li. The Yi li says that scribes recorded ritual items that were donated and interred with the tomb occupant, and that the resulting text was also interred during the funeral ceremony. In the introduction to his 1955 study of the slips excavated from an early- to mid-third century b.c.e. Chu tomb at Yangtianhu 仰天湖, Shi Shuqing 史樹青 collected many of the relevant passages from the classical literature and commentaries on tomb inventories.Footnote 56 The picture they provide can be summarized as follows: 1) the inventories recorded both the items that were interred with the deceased, whatever their provenance, and those items that were given (feng 賵) to the deceased and his family by others; 2) these texts were read out loud during the funeral ceremony, taking special care to note the combined tabulations of the items; 3) the interment of funerary goods and reading of the inventory were necessary to act properly according to principles of ritual propriety (li 禮).

Shi and subsequent scholars have convincingly argued that certain texts do follow parts of this model. The Yangtianhu strips, for example, list a variety of items that were presumably originally in the tomb (it had been looted prior to excavation). The strips provide specific amounts for each item, and strip 18 (see Figure 5), though badly damaged and fragmented, shows what appears to be a name and the start of a list of textiles.Footnote 57 Quite possibly, this strip enumerated all of the items that the listed person contributed to be interred with the deceased.

Figure 5. Strip 18 from Yangtianhu

The strips from tomb no. 2 at Wangshan 望山, Hubei, dated to the late fourth to early third century b.c.e., provided a much longer and more intact example of an inventory and gift list text. Excavators found the strips in the side chamber of the tomb, and though most were broken, a few intact strips measured 64 cm x 0.6 cm. They list three chariots, followed by enumerations of textiles and vessels. There is also some evidence that the strips separated out the listed goods into categories:

…(strip broken) 金器:六貴鼎,又(有)盍(蓋)。四(盌),又(有)盍(蓋)。二卵缶,又(有)盍…

…Bronze items: six covered ding vessels; four covered yuan vessels; three covered luan fou vessels…Footnote 58 (strip 46)

Unfortunately, because the strip is broken, it is impossible to tell whether or not it gave a specific function for the goods categorized under “bronze items” (jin qi 金器).

A more intact example of an inventory text comes from tomb no. 2 at Baoshan 包山, dated 316 b.c.e., the largest and richest of five tombs excavated there. The inventory text had been separated into four different sections, each placed in one of the tomb's four chambers. The sections list items that were indeed found in the tomb, though not necessarily in the same chamber as the text that mentions them.Footnote 59 Each section begins with a heading that appears to designate the function of the listed items: “bronze items for the grand burial ritual” (大兆之金器),Footnote 60 “bronze items in the dining room” (食室之金器),Footnote 61 and so on. The Baoshan inventory thus constitutes an intact example of an inventory text with goods categorized by function. It also provides evidence that the funeral ceremony included items for the burial donated by participants:

苛郙受:一![]() (笮),䶂(豹)韋之盾,二十鉄(矢)…

(笮),䶂(豹)韋之盾,二十鉄(矢)…

Ke Fu donated: One bamboo quiver with a sable skin cover, and twenty bronze arrowheads…Footnote 62 (strip 277)

This strip and a multi-sided “board” (du 牘), composed of joined bamboo strips, record items that were “donated” (shou 受) by participants in the ceremony.Footnote 63 This strip and board thus constitute the gift-list (fengshu 賵書) portion of the Baoshan inventory text. It is on the basis of these two different types of texts that scholars have made distinctions between inventories and gift lists.Footnote 64

All of these texts share two elements: a) lists of individually enumerated items that were buried with the tomb occupant; b) the names of people who appear to have donated items that were either used in the funeral ceremony, buried in the tomb, or both. Moreover, the Baoshan text, and quite possibly the Wangshan text, divided the goods into functional categories. The Baoshan categories suggest both ritual functions important for the funeral ceremony and uses that would be important for the tomb occupant in the afterlife. These characteristics do not completely conform with the textual and commentarial understanding of the inventory and gift-list texts summarized above. The importance of “ritual propriety” (li) as a motivating factor for the production of the texts is a moralistic interpretation of their function, and it is difficult to discern evidence from the texts themselves that they were read aloud. Nevertheless, these problems aside, the characteristics seen in these texts generally support their inclusion in the inventory and gift-list textual genres.

Moreover, inventories and gift lists probably were an important aspect of Zhanguo, or at least late-Zhanguo, funerary ceremonies and ideas of the afterlife. On the evidence of the Baoshan inventory, Guolong Lai has argued that the inventory and gift-list texts reflect a major change in conceptions of the afterlife. People in Zhanguo times, according to Lai, believed that the soul of the deceased lived on, that ritual actions were required to provide for the afterlife of that soul, and that surviving descendants were eternally bound to perform these rituals. The funerary inventories and gift-lists were an important part of perpetuating the bond, since they connected the living and the dead together in a scheme of ritualized communication, display, and exchange.Footnote 65 Constance Cook went further, arguing that the Baoshan inventory text was “for use by the deceased to present to officers in the otherworld at various points in his journey to Heaven.”Footnote 66

These arguments, however, cannot fully apply to the Zeng strips. Their lists and verifications, not to mention their focus on chariots, drivers, and horses, do not point only to ritual concerns associated with beliefs about the afterlife. We of course do see donors in both the Zeng strips and the gift-lists, and it is true that the Zeng strips describe many items that were found in Marquis Yi's tomb. Moreover, it is quite plausible that Zeng officials buried the two texts in the northern chamber at least partially for the benefit of the deceased Marquis; perhaps his spirit was meant to have access to the texts and, by extension, the procession that they recorded and verified. Nevertheless, categorizing the strips as “inventories” or “gift lists” in the same vein as those from later periods obscures the complex role that the Zeng texts played in the Marquis's funeral. As demonstrated in the previous section, the Zeng texts are the products of a complex planning process for the Marquis's funeral procession that involved Zeng officials and dignitaries from a wide geographic area. The texts were in no way meant to be an accounting of what was actually interred in the tomb, and we do not learn much from them about specific funerary rituals and offerings, nor functional categories that point to an explicit concern with sending the Marquis off on his journey through the afterlife. They are rather the products and integral components of producing and performing a political spectacle, one to which the Zeng state and other states devoted significant material resources. The Zeng texts do share some characteristics with the inventory and gift-list texts. Categorizing the strips as “inventories,” however, ignores the particular role that they played in the Marquis's funeral, and cannot shed light on the function the strips had in documenting the organization and performance of the funeral cortège.Footnote 67

The Zeng Texts and Political Spectacles in Early China

This essay has emphasized the differences between the Zeng texts and tomb inventories, both descriptions in received texts and excavated examples, in order to demonstrate the integral role the strips played in the performance of a Zeng state funeral procession. The evidence from the Zeng texts shows that Marquis Yi's powerful political peers contributed high-status material goods, especially horses and chariots, to the funeral, which Zeng state officials manipulated in order to produce an original funerary spectacle. Political aims were at least as important as beliefs about the afterlife in organizing, performing, and documenting the procession. What were these aims, and what role did the Zeng texts play in realizing them?

Many political motivations must have driven the planning and performance of Marquis Yi's cortège. We hardly need to list them, since funerals and funeral processions were indeed part of the normal course of elite Chunqiu and Zhanguo political life (see Figure 6).Footnote 68 The death of a ruler of Marquis Yi's wealth and status would necessarily have required an impressive funeral. Ritual texts, however, suggest a more concrete motivation for Marquis Yi's procession: ensuring a proper transfer of power to the Zeng heir. Even though the strips do not mention him, we must imagine that Marquis Yi's heir participated in the preparation and execution of the Marquis's cortège.Footnote 69 Some received texts provide detailed descriptions of the heir's role in these activities. A long passage from a chapter of the Li ji 禮記 (compiled as late as first century c.e.), “Za ji shang” 雜記上, for example, details how the heir of a deceased ruler was meant to receive goods donated in the ruler's honor. The passage describes how an envoy and his entourage, sent by a lord of a different realm, are to announce themselves to the heir's officers and present their gifts. One passage details how an assistant to the envoy should offer over a chariot and horse team, outlining a scenario that presents striking parallels with the evidence from the strips:

上介賵,執圭將命,曰:「寡君使某賵。」相者入告,反命曰:「孤某須矣。」陳乘黃大路於中庭,北輈。執圭將命。客使自下,由路西。子拜稽顙,坐委於殯東南隅。宰舉以東。

The principal assistant to the envoy presents the chariot and horses. Carrying a jade tablet he announces his message: “My lord has sent so-and-so to present this chariot and these horses.”

The officer retreats within to report the message to the heir, and returns with his message, saying: “Our bereft heir so-and-so awaits you.”

They present the dalu chariot with huang horses in the center of the courtyard, with the yoke shaft pointing north. Holding the jade tablet, the principal assistant shows the message to the heir. The attendants to the envoy lead the horses to the western side of the chariot. The heir gets down on his knees and bows his head down to the ground. The principal assistant sits and places the jade tablet at the southeast corner of the coffin. The steward takes it up and places it to the east.Footnote 70

By humbly accepting the gifts from the envoy, the heir expresses his somber respect for both his deceased ruler and the recognition given to him by the envoy's ruler. All of the horses and chariots donated to Zeng for Marquis Yi's procession must have been received in some formal manner. Even if the “Za ji shang” passage cannot be used as a reliable description of how Zeng officials received donations, it does remind us that the Zeng heir was probably involved in the donation ceremony, not to mention the procession itself.Footnote 71 Indeed, many examples from even further beyond the spatial and temporal boundaries of mid-fifth century b.c.e. Zeng confirm that the pomp and circumstance of a ruler's burial were often for the benefit of a successor, who usually played an important role in all related ceremonies.Footnote 72 For both the anonymous heir in the Li ji passage and the Zeng heir, the contribution of chariots and horses by dignitaries was not just homage to the deceased but also acknowledgement of the heir's legitimacy as the new ruler, and thus an expression of confidence in the longevity of the Zeng state. The authors of the Li ji passage, the organizers of Marquis Yi's cortège, and the participating officials were all keenly interested in ensuring political stability via an orderly transfer of power.

The strips tell us a more complicated story about the importance of the donations for Zeng, however, than the Li ji passage would lead us to believe. The latter emphasizes above all how the donations are to occur, and how the various actors are meant to comport themselves. It provides detailed protocol for the presentation of the items, their placement, and even the statements that the donating and receiving parties are required to make. We read nothing, however, about what the heir and his officers are supposed to do with the chariots and horses after the various donation ceremonies are complete. The attendants must have unhitched the horses from the chariot yoke in order to array them on the western side of the chariot, but we do not read explicitly that the horses and chariots are to be separated permanently for the funeral cortège. The Zeng texts tell us, however, that this is exactly what happened for Marquis Yi's procession. The Li ji passage describes how items for a funeral are to be properly exchanged between donors and recipients. On the strips, we read only the names and titles of the donors, not how they donated the items. The strips tell us only about the process by which Zeng funeral directors combined items from high status donors together to create the procession. The strips do not record details of protocol, but rather demonstrate the control Zeng officials exerted over opulent items donated from afar. This contrast between the Li ji passage and the Zeng strips is a good example of the strikingly different perspectives that received and excavated texts can bring to the same phenomenon. In this case, the Zeng strips provide direct insight into the strategies, motivations, and official processes that rulers and elite officials brought to funerals and processions. Whether or not Zeng officials followed rules of protocol along the lines of those seen in the Li ji passage, the Zeng texts demonstrate that their primary concern was to create and carefully document a splendid funeral procession that displayed the wealth, status, and power of Marquis Yi.Footnote 73

The Zeng texts also provide an important illustration of the active role texts played in ensuring that Chunqiu and Zhanguo processions were executed correctly, and thus fulfilled their potential as political spectacles. As argued above, the strips were a testament: they documented the process of organizing donated goods into a grand procession, and verified the performance of that procession. The counting dots and totals on the strips demonstrate that it was important to verify that Marquis Yi's procession went off correctly, according to a scheme that effectively displayed the importance of Zeng and the Marquis, and demonstrated the legitimacy of the heir. With stakes this high, it was important to ensure for the benefit of all involved that the procession was executed properly. The Zeng texts provided that assurance. We see texts playing a similar role in a treatise written centuries later: “Yufu zhi” 輿服志 (Treatise on Chariots and Robes), completed by Sima Biao 司馬彪 (d. c. 306 c.e.) and eventually appended to Fan Ye's 范曄 (fl. 389–446 c.e.) Hou Han shu 後漢書 (compiled c. 440 c.e.).Footnote 74

行祠天郊以法駕,祠地、明堂省什三,祠宗廟尤省,謂之小駕。每出,太僕奉駕上鹵簿,中常侍、小黃門副;尚書主者,郎令史副;侍御史,蘭臺令史副。皆執注,以督整車騎,謂之護駕。

When traveling to give offerings to Heaven at the suburban altar, the emperor uses the fajia procession.Footnote 75 When giving offerings at the Temple to Earth or at the Bright Hall, reduce the number of chariots by thirteen. When giving offerings at the ancestral temple, make further reductions. These are the xiaojia processions. Every time they go forth, the Grand CoachmanFootnote 76 drives at the head of the procession (lubo 鹵簿), assisted by the Regular Palace Attendant and the Minor Attendant of the Yellow Gates. The Director of the Secretariat is assisted by a Palace Clerk. The Attending Secretary to the Imperial Counselor is assisted by the Foreman Clerk of the Orchid Terrace. All of them are in charge of recording the procession in order to inspect and regulate the chariots and horses. This is called monitoring the procession.Footnote 77

The parallels with the Zeng strips are striking. According to the “Yufu zhi,” recording (zhu 注) the procession is necessary in order to “inspect and regulate” (du zheng 督整) the order and arrangement of chariots and horses. The assisting clerks thus played a key role in the procession, even if the passage tells us little about how and when they did their recording. Regardless, the passage emphasizes that certain officials were charged with ensuring that the proper order and protocol for a given procession were properly followed. The Zeng texts, and the scribes and officials who produced them, served exactly the same function, even if the strips do not explicitly articulate the required order of the chariots and horses. Whether or not the order outlined in the “Yufu zhi” was actually followed all of the time in imperial processions is of course impossible to say.Footnote 78 Equally, we cannot say whether or not the organization of the Zeng funeral cortège followed an established protocol always used for Zeng funerals, or if the director of the procession created it specifically for Marquis Yi's ceremony. We can safely conclude, however, that both the author of the “Yufu zhi” and the Zeng cortège director were well aware of the power of processions as spectacles that displayed wealth, status, and power. Written records and texts that organized and documented the procession, such as those recovered from the tomb of Marquis Yi, were necessary to effectively employ that power.

Appendix A: Translations of Tabulation Strips

Strips 120–21

■凡![]() 車十乘又二。

車十乘又二。![]() =(乘車),四

=(乘車),四![]() 車,囩軒,攻(工)差(佐)坪所

車,囩軒,攻(工)差(佐)坪所![]() 行

行![]() 五乘。遊車九乘,囩軒,一

五乘。遊車九乘,囩軒,一![]() (畋)車。一椯

(畋)車。一椯![]() (轂)。一王僮車。一

(轂)。一王僮車。一![]()

![]()

…車。![]() (路)車九。▄Footnote 79 大凡四十乘又三乘。

(路)車九。▄Footnote 79 大凡四十乘又三乘。 ![]() 至紫。

至紫。

In total there were 12 broadFootnote 80 chariots. There were four battle chariotsFootnote 81 with curved railingsFootnote 82; five swift broad chariots built by the artisan assistant PingFootnote 83; nine touringFootnote 84 chariots with curved railings; one hunting chariot; one chariot with decorated hubcapsFootnote 85; one royal tong chariotFootnote 86; one covered chariotFootnote 87 [end of strip 120]…chariot; and nine road chariots.Footnote 88 This makes a grand total of forty-three chariots. [long gap in strip] They came here. [end of strip 121]

Strips 140–41Footnote 89

…Footnote 90□Footnote 91所![]()

![]() 十真

十真![]() =(又五) 真。Footnote 92大凡

=(又五) 真。Footnote 92大凡![]() =

= ![]() (六十) 真又亖(四)真。

(六十) 真又亖(四)真。

…□所![]() 丗(?)

丗(?)![]() (匹)之甲。大凡

(匹)之甲。大凡![]() (八十) 馬甲

(八十) 馬甲![]() (又六) 馬之甲。

(又六) 馬之甲。

…made fifteen armor sets.Footnote 93 In total there were 64 armor sets. [end of strip 140]

…made thirty horse armor sets. In total there were 84 horse armor sets. [end of strip 141]

Strip 148

■ 凡新官之馬六乘。

In total there were six chariots with New Office horse teams.

Strip 159

■ 凡大官之馬六乘。

In total there were ten chariots with Grand Office horse teams.

Strip 195

![]() (旅)

(旅) ![]() 公之

公之 ![]() (路)車三乘,屯麗。 凡

(路)車三乘,屯麗。 凡 ![]()

![]() (路)車九乘。

(路)車九乘。

There were three road chariots from the Duke of Lüyang with a team of black horses.Footnote 94 In total there were nine ![]() chariots.Footnote 95

chariots.Footnote 95

Strip 196

…■凡 ![]() (路)車九乘。

(路)車九乘。

In total there were nine road chariots.Footnote 96

Strip 204

■ 凡 ![]() 車:

車: ![]() =(

=(![]() 車),

車),![]() = (

= (![]() 車)

車)![]() = (

= (![]() 車)八乘。

車)八乘。

In total there were eight ![]() chariots, including broad chariots, bi chariots, and hunting chariots.

chariots, including broad chariots, bi chariots, and hunting chariots.

Strip 207

■凡宮廏之馬與 ![]() Footnote 97十乘 入於此

Footnote 97十乘 入於此 ![]() 官之

官之![]() (中)。

(中)。

In total there were ten chariots with horse and ?Footnote 98 teams from the Palace Hall. They were received here at the ![]() Office.Footnote 99

Office.Footnote 99

Strip 208

■凡宮廏之馬所入長 之![]() (中)五乘。

(中)五乘。

In total there were five Palace Hall horse and chariot teams that were received at Changhong.

Appendix B: Zeng-Chu Relations and the Zeng Strips

Ishiguro Hisako has advanced strong arguments about Zeng-Chu relations based on the Zeng strips; a brief overview of her ideas will offer a contrast with this essay's approach and illustrate the limitations of the strips as a source. Her general point that the strips mention officials and donors from both Zeng and Chu and thus provide insight into relations between the two states is helpful. She makes two specific claims that deserve greater scrutiny, however. First, she argues that whole strip groups can be identified as listing either “Zeng” or “Chu” officials. Second, she says that the word “king” (wang 王) refers in one case (strips 187–89) to the King of Chu and in another case (strip 54) to the King of Zeng (the heir), demonstrating a difference between the internal and external presentation of the Zeng state, with the Zeng ruler using “Marquis” in formal settings and “King” in “daily” (nichijō 日常) situations that would be unseen to the King of Chu.

At least three problems with this analysis can be identified. First, as Ishiguro herself frequently allows (e.g., 63n53), the strips never use “Zeng” or “Chu” to mark geographic identity, so we cannot be sure of our identifications of titles.Footnote 100 Second, there is no reason to suppose, as Ishiguro does, that if the “king” on strip 54 were the King of Chu, his status would have to have been more clearly demarcated from other titles. As this essay has shown, only C strips (which do not include strip 54) attempt to distinguish the status or identity of officials by listing them on separate strips. Moreover, there is good reason to believe that the wang 王 on strip 54 was a chariot donor, not a driver, and not necessarily a “king.”Footnote 101 Finally, the picture in the excavation report of strip 54 shows a badly smudged character, illegible to this author, where wang is supposedly located.Footnote 102 It hardly bears mention that it makes little sense to assume the strips record “daily” practice (a concept quite difficult to define), or that Chu scribes and officials could not have seen the strips. The procession itself was hardly a “daily” occurrence: this essay has shown that the strips were an integral part of a highly formal and regulated procession, the staging of which involved a large number of organizers and scribes. The strips themselves must have been handled and seen by many people, some of whom could have hailed from beyond Zeng's borders. If the authors of the strips used wang to refer to the Zeng heir, a Chu envoy at the procession would have been able to figure this out.

The strips thus do not easily yield detailed evidence for the specific dynamics of Zeng-Chu relations. They use a date marker commonly employed on Chu strips (see translation above), but little can be deduced from this fact. This essay, by showing how the funerary procession was organized and performed, and the role of the strips in the procession, has the specific aim of showing how the Zeng ruling house used the procession and the texts to effectively display its power and ensure a proper transfer of rule. This information might be used to help us imagine, in a general way, how Zeng-Chu relations played out in the context of a political spectacle, even if the details remain elusive.