The crossbow trigger, invented in or introduced into China around the sixth century b.c.e., was a powerful device that had a major impact on warfare in the ages to come. Ancient texts marveled at the efficacy of the crossbow as a killing machine. Military strategists made frequent use of it in tactical maneuvers.Footnote 1 Against such a background, the word for “trigger,” ji 機 or sometimes its cognate ji 幾 without the “wood” signific, became a pregnant metaphor in the early Chinese intellectual milieu. The basic meaning of this metaphor comes from how the trigger mechanism works—a small act of pulling the trigger leads to the death of a person a hundred yards away. Metaphorically, it stands for the correlation between a barely perceptible act and a far-reaching and potentially disastrous consequence.Footnote 2 The image was appropriated in a variety of contexts by thinkers with diverse and often opposing agendas. As it became increasingly paradigmatic, other images were assimilated into the same metaphorical scheme, which eventually developed into an intricate web of associated images.Footnote 3

The purpose of this article is not only to examine this metaphorical scheme but also to do so from a metaphorological point of view. The term “metaphorology” is coined by the German philosopher Hans Blumenberg (1920–1996), who argues in his early work Paradigms for a Metaphorology (1960) against the predominance of conceptual analysis in the history of ideas. For him, the long-standing obsession with well-defined terminologies masks the catalytic role images play in the historical transformation of thought patterns. The metaphors that a thinker favors often reveal deep-seated dispositions and orientations, which are otherwise buried under the explicit propositions made by the same person. These images, especially the way they are used, may reveal as much about the thinker's fundamental beliefs as pure concepts do.Footnote 4 Metaphorology is just that subterranean field that traces the way the meaning of an image changes from one thinker to another. It is not necessarily the antithesis of conceptual analysis but that which complements and enriches it.

After a brief opening section on metaphorology, I shall examine controversies over the original meaning of ji and then discuss examples of the trigger metaphor. In early Chinese texts, this metaphor is almost always used for dealing with practical issues concerning human action. Its meanings fall into two broad categories, the ethical and the instrumental. The ethical use serves primarily as admonitions, emphasizing that great caution is needed to prevent innocuous lapses from developing into great calamities. The instrumental use takes the crossbow trigger as a device that achieves great result with little effort, which enables a metaphorical conception of cost-efficient strategies. My analysis shall also demonstrate two opposite trends in the development of metaphorical meaning. There is, on the one hand, metaphorical divergence, or how the same image gets appropriated for different purposes, and, on the other, metaphorical convergence, or how different images are identified as having the same semantic structure.

METAPHOROLOGY AND EARLY CHINESE THOUGHT

Blumenberg's Paradigms for a Metaphorology, originally published in the Archiv für Begriffsgeschichte (Archive for the History of Concepts), is an influential critique of the methodological assumptions of the journal as well as the young discipline of conceptual history in Germany. For Blumenberg, the project of conceptual history adopts the Cartesian ideal of an “end state” of philosophy, which corresponds to “the perfection of a terminology designed to capture the presence and precision of the matter at hand in well-defined concepts.”Footnote 5 The teleological nature of this ideal would conceal the history of conceptual formation which lies in nothing but metaphor. Metaphor stands half way in the development from mythos to logos, from the life-world of concrete experience to the logical world of definitions. It is not an undesirable and provisional element to be eliminated at the end, but a “foundational element of philosophical language” and “a catalytic sphere from which the universe of concepts continually renews itself, without thereby converting and exhausting this founding reserve.”Footnote 6 Blumenberg calls the metaphors that can never be fully converted into precise definitions “absolute metaphors.” Absolute metaphors work as background ideas of an age that provide guiding structures for the possibilities and limitations of thought.

From a metaphorological point of view, therefore, metaphor is as fundamental a vehicle of thought as concept is, and intellectual history can be written by taking particular metaphors as its subject matter. Many of Blumenberg's works center on the contested meanings of an image throughout history, such as truth as light and life as seafaring. Although his philosophical interest lies mostly in metaphors for truth and theory, he is particularly concerned about the pragmatic implication of these metaphors as historical objects. Adopting a particular metaphor of truth, for example, means adopting a set of attitudes and pragmatic orientations towards truth. While the metaphor of “mighty truth” in classical times makes the human intellect a passive receptor overwhelmed by truth that forcefully reveals itself, the modern world turns this metaphor upside down with the Baconian metaphor “knowledge is power,” through which the mind toils at hypothesis and experimentation, testing theoretical models of its own design against nature.Footnote 7 As a historically conditioned way of seeing and acting, our truth metaphor predisposes us to a particular style of truth-seeking. If a metaphor of truth determines how truth is to be imagined and pursued, then the truth of that metaphor is undecidable, at least not within the conceptual framework determined by the same metaphor. Therefore, a truth metaphor is not a reflective, falsifiable theory about what truth is, but a historical testimony to the truth-perception and truth-pursuit of an age.

Interestingly enough, the main tenet of metaphorology loses a great deal of its polemical force when transplanted to the early Chinese soil. There is no need to argue, as Blumenberg does, against the Cartesian ideal of a philosophical terminal state in which everything is strictly defined and purely conceptual, for the insistence on terminological stricture never holds sway among the Warring States masters (perhaps with the only exception of Later Mohists), who feel comfortable about using metaphors to argue over even the most serious topics. Moreover, the pragmatic orientation of metaphor seems fully recognized—without a corresponding notion of theoria as spectatorship, classical thinkers use metaphor to remold their understanding of a social reality in which they are already involved. Due to the scarcity of theoretically oriented metaphors, the question of the justifiability of metaphorical thinking never receives much attention. In such a context, metaphorology would become a neutral and especially suitable frame of analysis rather than a manifesto.

It is worth noting that as early as in 1973, Tang Junyi 唐君毅 (1909–1978) already made a quasi-metaphorological analysis of dao, which holds the place of “truth” in Chinese thought, without using the word “metaphorology.” In his own words:

中國哲學中之基本名言之原始意義,亦正初為表此身體之生命心靈活動者。試思儒家何以喜言“推己及人”之“推”?莊子何以喜言“遊於天地”之“遊”?墨子何以喜言“取”?老子何以言“抱”?公孫龍何以言“指”? … 誠然,字之原義,不足以盡其引申義。哲學之義理尤非手可握持,足所行履,亦非耳目之所可見可聞。然本義理以觀吾人之手足耳目,則此手足耳目之握持行履等活動之所向,亦皆恆自超乎此手足耳目之外,以及於天地萬物。Footnote 8

The basic terms in Chinese philosophy originally stand for nothing but the living and mental activities of this body. Try to think about the following examples: Why do Confucians like speaking about “pushing,” as in “pushing oneself to reach others?” Why does Zhuangzi like speaking about “roaming,” as in “roaming between heaven and earth?” Why does Mozi like speaking about “taking?” Why does Laozi speak about “embracing?” Why does Gongsun Long speak about “pointing?”Footnote 9 … To be honest, the original meanings of characters are not enough to cover the full range of their derived meanings. Philosophical meanings and principles especially are not things that can be grasped by hands, stepped on by feet, seen by eyes, or heard by ears. Nevertheless, if one looks at eyes, ears, hands, and feet on the basis of those meanings and principles, then the activities of these organs (such as grasping and stepping) are so oriented that they constantly go beyond the organs themselves till they reach heaven, earth, and the ten thousand things.

此導論上文,言道之類比,則要在以人行之道路為類比,以使人對“道”作一圖像的思考。此圖像的思考吾不如今之西哲之或加以輕視。Footnote 10

The key to the above discussion of analogies of dao is that it uses the walking path as an analogy to make people think about dao with images. I do not have contempt for such imagistic thinking as contemporary Western philosophers do.

For Tang, the concept of dao is grounded in the living experience of the human body and must be understood by evoking the image of the walking path that functions as a master metaphor on which other philosophical metaphors such as “pushing” and “roaming” are based. His analysis is particularly meaningful in light of Blumenberg's theory, because the word dao means not only “path” but also “guidance,” pointing unequivocally to the pragmatic function of the metaphor itself.

Readers familiar with metaphor studies in sinology may wonder at this point why I opt for metaphorology rather than Lakoff and Johnson's conceptual metaphor theory that has been customarily cited by prominent scholars in the field, and whether my choice places me on the side of those who have voiced skepticism about the applicability of this theory to Chinese thought.Footnote 11 I do not intend to take sides in the debate; both the advocates and the critics seem to me to have made valuable points. Since the major insight of metaphorology about metaphor's irreducible cognitive value is undoubtedly compatible with the conceptual metaphor theory, to cite the former implies no substantial disagreement with the latter.Footnote 12 If one cites them only for that core insight, there is no need to draw any fine-grained distinction between the two, and even more candidates can be included for consideration. That being said, the nature of my topic, as well as the style of my analysis, belong more properly to metaphorology for at least two reasons. The conceptual metaphor theory is a branch of cognitive science that seeks to uncover universal cognitive mechanisms of the human mind. In its classic version, the object of analysis is, for the most part, dead metaphors in everyday linguistic expressions that native speakers constantly use but barely recognize, because the goal is to prove that the use of metaphor requires no special talent or poetic genius. A side effect of this approach, however, is that it tends to flatten out the intellectual sharpness of certain metaphors that are not artistic but still special, creative, and sometimes individualized. This is, to be fair, not a necessary corollary to the theory, but is often tacitly assumed in the choice of examples. Metaphorology, on the other hand, is a branch of intellectual history that works precisely in the space between codified banality and imaginative caprice. It deals not with highly conventionalized metaphors in everyday speech, but with epochal metaphors that indicate historical ruptures and epistemic changes. The function of such metaphors is not only to structure but also to restructure abstract domains of human experience. This is why Blumenberg describes his absolute metaphor as a “catalytic sphere” from which philosophers constantly draw inspiration.

Another important difference is that, whereas the conceptual metaphor theory thinks of metaphor as a matter of systematic mappings from one domain to another, metaphorology makes no use of that method of analysis. Instead, it pays close attention to the shades of meaning of paradigmatic images as they vary in the hands of different authors. This is especially relevant to a phenomenon that I would call “metaphorical divergence,” namely how the inherent ambiguity of a metaphor lends itself to different appropriations. The relationship between metaphorology and my analysis will become clearer toward the end of the article when all the examples have been examined. I shall then return to the theoretical problem with a more concrete understanding gained along the way.

THE MEANING OF JI

There is a long-standing controversy over the original meaning of ji, whether it refers to the loom or the crossbow trigger. The uncertainty is already implied in the definition of ji in the Shuowen jiezi 說文解字, the first comprehensive dictionary of Chinese characters completed in 100 c.e. The Shuowen defines ji 機 (*kəj) as an object that “governs the shoot” (zhufa 主發) and the cognate ji 幾 (*kəj) as “subtle” (wei 微) and “dangerous” (dai 殆 and wei 危), explaining that the “dangerous” meaning comes from the two semantic constituents, “silk” 𢆶 and “to guard” 戍.Footnote 13 These definitions seem to relate ji to the crossbow trigger; however, as Duan Yucai's 段玉裁 (1735–1815) commentary points out, the three characters that follow immediately are all names for different parts of the loom, whose definitions all use ji as the name of the loom.Footnote 14 It is difficult to reconcile the definition of ji with its lexicographical setting in the Shuowen.

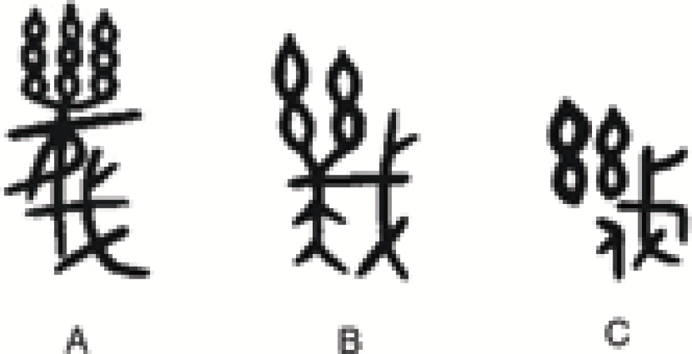

To test the validity of the Shuowen definitions, we need to turn to paleographic evidence. There is no documented use of ji 機 in pre-Warring States (453–222 b.c.e.) excavated texts. The cognate ji 幾, on the other hand, appears several times on pre-Warring States bronze vessels in the following forms:Footnote 15

While these graphic forms are close enough to the seal character given in the Shuowen, they are used only as personal or clan names. Nothing from the context provides any clue as to their original meaning. Ji Xusheng 季旭昇, who first relates A to ji 幾, analyzes it into three semantic constituents—“mother” 母 (or “person” 人 in B and C), “silk” 𢆶, and “dagger axe” 戈, arguing that the graphic form “obviously” depicts a dangerous situation in which the silk cords that suspend a person are about to be cut by a dagger axe.Footnote 16 Pankenier, on the other hand, argues that the presence of the “silk” signific indicates an evident link to weaving and loom.Footnote 17 Neither can be conclusive, because it is always risky to infer the original meaning of a character from its intrinsically ambiguous graphic form without sufficient contextual support. If Ji Xusheng is right, then one wonders why cutting the silk cords means “danger” rather than “releasing” or “setting free.”

If we look at material evidence, then it seems that the loom would be the primordial referent of ji. As Pankenier notes, the history of the loom goes all the way back to the Neolithic times.Footnote 18 If ji refers to the crossbow trigger, then this meaning cannot possibly predate the material technology itself. Nevertheless, the early existence of the technology alone is no proof of the character's original meaning, for there is no linguistic evidence that the character was used to refer to the loom before the Warring States. When ji appears in a Warring States text as the name of a material object, it almost always means “crossbow trigger,” “trigger mechanism,” or simply the unspecified “machine,” a fact hardly conceivable if the original meaning of ji had been “loom.” As Zhu Junsheng 朱駿聲 (1788–1858) notes, the word is never glossed as “loom” even in the first generation of commentaries to classical texts produced in the Han (202 b.c.e.–220 c.e.).Footnote 19 As far as I can tell, the earliest unquestionable evidence of ji's “loom” meaning is found in the compound jizhu 機杼 “loom and shuttle” that appears only in Han texts such as the Huainanzi 淮南子.Footnote 20 The discrepancy between material and linguistic evidence is no less puzzling than the one between ji's definition and its place in the Shuowen.

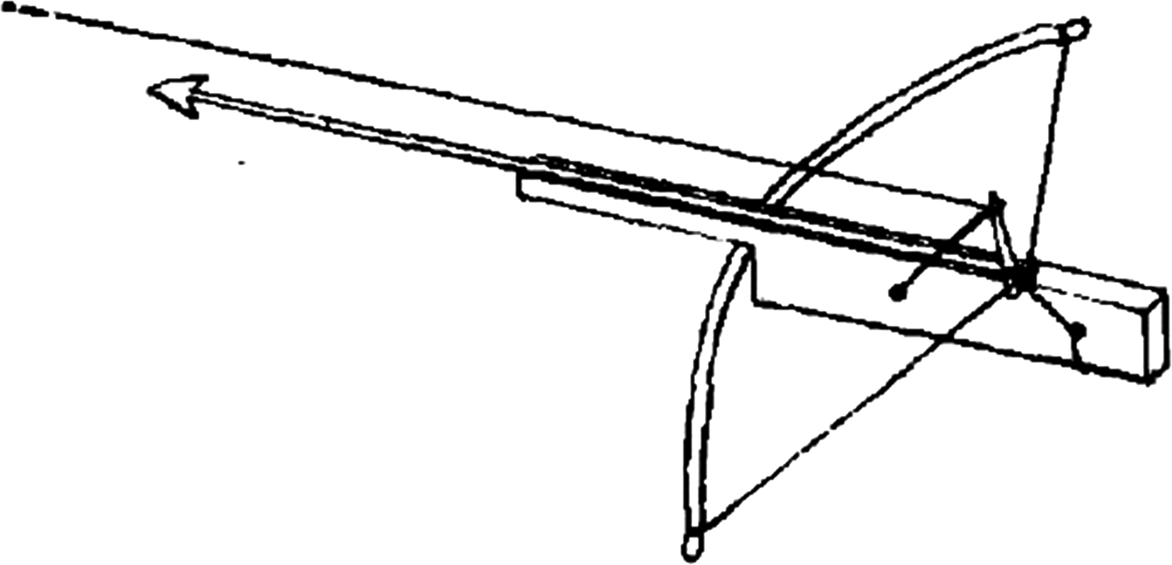

I believe this problem can be tackled, if not solved, by looking at a type of evidence rarely consulted by paleographers: ethnographic records. In a study of the possible origin of the crossbow in China, Song Zhaolin 宋兆麟 and He Qiyao 何其耀 report the widespread use of primitive wooden crossbows in tribal societies in China before 1949.Footnote 21 They observe that the majority of these ethnic groups, especially the Oroqen people in Heilongjiang and the Nakhi in Yunnan, use a kind of “ground bow” (digong 地弓) or “ground crossbow” (dinu 地弩) to set up animal traps. A ground crossbow installation usually consists of a simple crossbow fixed to the ground and a string attached to its wooden trigger, the other end of which is attached to a low branch at a distance (see Figure 1). When the animal touches the (sometimes baited) string, it triggers the crossbow and releases the bolt. Such an automatic trap saves the trouble of aiming and is reported to be much more effective than handheld crossbows.

Figure 1 The ground bow used by the Oroqen people.Footnote 22

The problem of origin aside, the relevance of the crossbow trap to our inquiry is that all the main elements of such an installation correspond to the semantic components of ji's archaic form: “person” 人 is the victim, “dagger axe” 戈 the weapon, and “silk” 𢆶 the string attached to the trigger. To be sure, this graphic interpretation is no less conjectural than those cited above, but it can also account for all the standard meanings of ji 幾 in early texts—(1) “subtle/minute” is derived from the string-trigger that must be concealed, (2) “dangerous” from the effect of the weapon, and (3) “close/nearly” from the situation in which a victim is about to fall prey to the crossbow trap (which is closely related to the “dangerous” meaning). Ji Xusheng leaves out (3), and Pankenier leaves out (2). We may also find vestiges of ji's primordial meaning in later texts—Sima Qian 司馬遷 (c. 145–c. 86 b.c.e.), for example, mentions the installation of jinushi 機弩矢 (literally “trigger-crossbow-bolt”) in the tomb of Qin Shi Huang for the purpose of guarding the treasures.Footnote 23 The compound most likely refers to unattended crossbow traps that resemble the ground crossbow but are far more advanced in design. The term ji in this compound certainly does not mean crossbow triggers that require human operators.

The merit of this interpretation, if still tentative, is that it explains away the contradiction between material and linguistic evidence. The elaborate crossbow triggers from Warring States tombs may be a late invention, but a wooden crossbow trap is simple enough to have had a much earlier origin. There is, however, one difficulty. My argument so far has in effect dissociated ji from a particular type of object, be it the loom or the bronze crossbow trigger, and instead related it to a general type of object, namely the trigger mechanism. Why, then, do we need to mention the crossbow at all? I can offer two reasons here. First, the original meaning of ji is still related to the crossbow as a killing machine, otherwise there would be no ground for its “dangerous” meaning. Second, with the advent of the bronze crossbow trigger, the new gadget quickly became the prototype of trigger mechanism due to its prominence in warfare. I believe this new technology does mark a decisive turn in the semantic history of ji from an ordinary word to a philosophically significant metaphor. The scarcity of evidence does not permit us a detailed account of the process, but a parallel development seems to have existed in the case of shi 勢. In pre-Eastern Zhou oracle bone and bronze inscriptions, shi meant, clearly and consistently, “to plant,” “to set up” or the nominal “setup,” and nothing else.Footnote 24 In the Warring States period, however, its meaning started to proliferate in the hands of newly emerged war experts who reflected on their technique and produced military texts. Their appropriation of an originally simple word culminated in a long list of possible translations such as “disposition,” “circumstance,” “power,” “positional advantage,” and so on.Footnote 25 While ji underwent no such proliferation, it evolved into a metaphorical keyword, probably also in the hands of the military specialists who put the crossbow to use.

Finally, the ambiguity of ji points to a conceptual affinity between the trigger and machine itself—that is, a device comes to be called a machine just by having some kind of trigger mechanism. When looking at the ancient Chinese concept of machine it is difficult not to project onto it our post-industrial mechanistic world picture, in which the “mechanical,” as opposed to the “organic,” implies automatic causal chains based on direct contact of lifeless physical bodies. It is unlikely, however, that such a dichotomy was even conceivable to the early Chinese mind. Classical texts depict ji or xie 械, the near equivalence of the modern “machine,” typically as tools that demand little effort but produce great result:

有械於此,一日浸百畦,用力甚寡而見功多。Footnote 26

There is a machine here, which can water a hundred fields in one day. It demands little force but produces many results.

明於權計,審於地形、舟車、機械之利,用力少致功大,則入多。Footnote 27

Be clear about the strategies of leverage. Examine the advantages of terrain, boats, chariots, and machines. Exert little effort but achieve great results. Then the income will be abundant.

行海者坐而至越,有舟也。行陸者立而至秦,有車也。秦越遠途也。安坐而至者,械也。Footnote 28

Those who travel by sea can sit and reach the state of Yue, because there is a boat. Those who travel by land can stand and reach the state of Qin, because there is a chariot. Qin and Yue are far away. That by which one reaches there by sitting peacefully is the machine.

What the concept of machine entails is the labor-saving capacity in difficult tasks. The focus is not on the theoretical relevance of the machine in explaining causalities in the world but on its pragmatic value in human life. As can be seen, the early Chinese concept of machine is semantically isomorphic to the crossbow trigger metaphor, which adds additional support to my claim that the original meaning of ji is “trigger.”

METAPHORICAL DIVERGENCE AND CONVERGENCE

What I call divergence and convergence are two contrasting trends in the development of the trigger metaphor—the same image gets interpreted and appropriated in divergent ways, and different images converge on the same semantic structure.Footnote 29 In this section, I shall use plenty of examples to illustrate them. My description of the two trends will show that ji is not just a simple trope but a metaphorical scheme with a complex structure.

The divergence of the trigger metaphor itself is metaphorically rooted in the ambiguity of the material device. The crossbow trigger has radically different meanings for the person being targeted and the person holding the crossbow, as the same act of shooting appears dangerous to the victim and efficient to the crossbowman. For the victim, who suffers the effect of the crossbow before realizing its subtle cause, the trigger means that great pain can result from even little mistakes, whereas for the crossbowman, who knows the cause before the effect, it means that a small, ingenious device can bring great advantage effortlessly. The trigger metaphor, accordingly, can be used either in an ethical sense, which usually serves in admonitions about potentially harmful consequences of one's action, or in an instrumental sense, which provides a model for conceiving efficient methods in various realms of techne including statecraft, military tactics, and medical therapy.

I do not want to maintain that all metaphorical uses of ji fall easily, obviously, and tidily into one of the two groups I have distinguished; they are only general tendencies in using this metaphor, not clear-cut, exhaustive semantic categories to which all nuances can be reduced.Footnote 30 I do think, nonetheless, that in most cases we should be at least fairly strongly inclined to assimilate a metaphorical use of ji to one group rather than to the other, because the divergence is a second-order ambiguity derived from the ambiguity of “subtle” and “dangerous” rooted in the material function of the trigger. The metaphorical scheme of ji, taken together, is complex and systematic, consisting of three levels of interwoven ambiguities: the ambiguity of the object that is disastrous and beneficial, the ambiguity of the word that means “subtle” and “dangerous,” and the ambiguity of the metaphor that has instrumental and ethical uses.

When the trigger metaphor is used to teach a moral lesson, it presupposes an analogy between social interaction and archery: the words, actions, and judgments that we “shoot” at other people may inflict pain on them like arrows do. Coupled with this analogy, the trigger metaphor creates disproportionate tension between the source and the target and magnifies the ethical significance of our daily activities. It can thus be easily blended with the Confucian belief that the key to government is the self-cultivation of the ruler or official. Therefore, our first group of examples come from Confucian or quasi-Confucian sources:

口,關也。舌,幾也。一堵失言,四馬弗能追也。Footnote 31

The mouth is a latch, the tongue is a trigger. Once one makes an indiscreet remark, four horses cannot catch it.

子曰:「君子居其室,出其言善,則千里之外應之,況其邇者乎?居其室,出其言不善,則千里之外違之,況其邇者乎?言出乎身,加乎民。行發乎邇,見乎遠。言行,君子之樞機。樞機之發,榮辱之主也。言行,君子之所以動天地也。可不慎乎?」Footnote 32

The Master said, “If the gentleman stays in his room and sends out good words, then those who are a thousand miles away respond to them, let alone those who are near. If he stays in his room and sends out mean words, then those who are a thousand miles away defy them, let alone those who are near. Words start out from oneself and act on common people. Actions start out near and manifest themselves in distant places. Words and actions are the axle-trigger of the gentleman. The shooting of the axle-trigger is the lord of honor and disgrace. Words and actions are that by which the gentleman moves heaven and earth. How can one not be careful?”

一家仁,一國興仁。一家讓,一國興讓。一人貪戾,一國作亂。其機如此Footnote 33

If one family is benevolent, benevolence will rise in the entire state. If one family yields, yielding behaviors will rise in the entire state. If one person is greedy and perverse, turmoil will be produced in the entire state. Such is what their trigger mechanism is like.

The first passage comes from an untitled late Warring States bamboo manuscript found in Shuihudi 睡虎地, Hubei in 1975, which contains assorted instructions and aphorisms used for the moral and professional training of local officials. The short passage in which it occurs seems to be an appendix attached to the end of the text. It compares the tongue to a trigger not because the tongue is a speech organ that controls the articulation of infinite meaningful sounds, but because of its capacity for causing others great distress. Words travel so incorrigibly fast that the official must keep a tight rein on them in hearing litigations or dealing with administrative affairs. In the second passage attributed to Kongzi 孔子 (trad. 551–479 b.c.e.), the metaphor goes beyond the administrative setting and applies to any gentleman devoted to moral cultivation. The semantic ambiguity of the trigger metaphor manifests itself in a series of contrasts: the near and distant, one's own room and a thousand miles away, as well as the gentleman's body and heaven and earth. In fact, it is slightly uncertain whether the metaphor here is ethical or instrumental. If the axle-trigger is that by which the gentleman manages honor and disgrace and moves heaven and earth, then it seems that the intended movement is from cause to effect. Nevertheless, the last sentence is a warning with an overall emphasis on caution rather than ingenuity. The third passage, from the “Great Learning,” metaphorizes the huge political fallout of the ruler's action in terms of the trigger mechanism. As is well-known, the beginning of “Great Learning” claims that self-cultivation is the root of politics because the virtue of the gentleman ripples through the whole state. The metaphor is embedded in one part of this claim that “to bring order to the state, one must regulate the family first” (zhi guo bi xian qi qi jia 治國必先齊其家). It refines the comparison made in the Analects 12.19 that the virtue of the ruler is like wind that easily bends the virtue of petty people.

The trigger metaphor is not only used for words and actions, but also for the mind capable of “shooting out” judgments at others in the Zhuangzi:

其寐也魂交,其覺也形開。與接為構,日以心鬪。縵者,窖者,密者。小恐惴惴,大恐縵縵。其發若機栝,其司是非之謂也。其留如詛盟,其守勝之謂也。Footnote 34

When sleeping, the souls cross their paths. When awake, the body opens. Reaching out and making contacts, each day we use our mind for strife. The calm ones. The deep ones. The secretive ones. Petty fears intimidate; great fears calm. Shooting forth like a trigger releasing the string on the notch: such is our arbitration of right and wrong. Holding fast as if to sworn oaths: such is our defense of our victories.

Zhuangzi offers a vivid description of the strife-loaded human life constantly disturbed by “arbitrations of right and wrong.” When the mind “reaches out and makes contact” with the world, it works like a trigger that hurts others by its own subtle turnings. Zhuangzi's metaphor does not convey a moral message in the normal sense, given his highly sophisticated pathology of value judgments, but it nonetheless alerts us to the precarious agency of our mind and its potential butterfly effect. A similar metaphor can be found in the Xunzi:

故《道經》曰:「人心之危,道心之微。」危微之幾,惟明君子而後能知之。Footnote 35

Therefore the Classic of the Way says: “The mind of man is precarious; the mind of the Way is subtle.” Only by being an enlightened gentleman can one understand the trigger mechanism of the precarious and the subtle.

The exact meaning of this statement is uncertain: by the phrase wei wei zhi ji 危微之幾, Xunzi could mean either “the trigger mechanism of the precarious and the subtle” or simply “the subtle difference between the precarious [mind] and the subtle [mind].” In the second case, ji could still mean “trigger,” but it would be a trigger of a different kind, not a crossbow trigger but a switch that controls the transition between two states of mind. The difference between the two possible meanings is perhaps not so significant, for either case involves the correlation between a subtle and a major change.

These trigger metaphors about speech, action, and the mind bear the hallmark of their age. In Warring States politics, a debate was often not a harmless academic dispute but a matter of life and death. One can get a visceral sense of the horrifying consequences of inappropriate speech at court by reading the Hanfeizi 韓非子. In the “Nan yan” 難言 “The Difficulty of Speaking” and “Shui nan” 說難 “The Difficulty of Persuasion,” Han Fei 韓非 (c. 280–233 b.c.e.) conveys a deep insecurity about choosing the correct rhetorical style, even though he makes no use of the metaphor itself.Footnote 36 Had he used it, the point of his metaphor would have been different from the teachings one finds in Confucian or Daoist writings, because he cared less about the harmful effect of speech on others than on himself. In other words, it would not have been about self-cultivation, but about self-preservation.

The next two examples pertain to the epistemological importance of ji as the barely detectable embryo of a thing. In the divination theory of the “Xi ci,” ji refers to the subtle omen of a favorable situation:

幾者動之微,吉之先見者也。君子見幾而作,不俟終日。Footnote 37

The trigger is a subtle movement where auspiciousness can be seen in advance. The gentleman acts upon seeing the trigger and does not wait till the end of the day.

The point is that these embryos are difficult to see but easy to remove. The ability to see the trigger of a situation is a perspicacious foresight that helps the gentleman take timely precautions and prevent future catastrophes without much effort. The same metaphor is illustrated by an extended anecdote without reference to divination in the “Cha wei” 察微 “Scrutiny of the Subtle” chapter of the Lüshi chunqiu 呂氏春秋 or The Annals of Lü Buwei:

鄭公子歸生率師伐宋。宋華元率師應之大棘,羊斟御。明日將戰,華元殺羊饗士,羊斟不與焉。明日戰,恕謂華元曰:「昨日之事,子為制;今日之事,我為制。」遂驅入於鄭師。宋師敗績,華元虜。夫弩機差以米則不發。戰,大機也。饗士而忘其御也,將以此敗而為虜,豈不宜哉?故凡戰必悉熟偏備,知彼知己,然後可也。Footnote 38

Prince Guisheng of Zheng led an army to attack Song. Hua Yuan of Song led an army to meet the enemy at Daji, with Yang Zhen serving as his charioteer. The next morning, as the battle was impending, Hua Yuan slaughtered a lamb to feed his knights but did not share any with Yang Zhen. As the battle began on the next day, Yang Zhen angrily said to him, “In yesterday's matter, you were in charge; in today's task I am in charge.” He then drove the chariot into the middle of the Zheng army, leading to the disastrous defeat of the Song army and Hua Yuan's capture. When the trigger mechanism of a crossbow is off by the length of a single grain of millet, it cannot shoot. A battle is a giant crossbow trigger. Hua Yuan fed his knights but forgot his charioteer; the outcome was the defeat of his army and his own capture. In this not fitting? Thus, as a general principle, in battle everything should be thoroughly considered and fully prepared; only when you know both the enemy and yourself may you proceed.

The story compares Hua Yuan's small negligence with the crossbow's being off by the length of a single grain of millet, and the defeat of the Song army with the shooting (or hitting the target for that matter). In fact, the entire chapter is about the importance of knowing ji, though only this passage uses the metaphor explicitly. I tend to think that these two examples, especially the second one, are more instrumental than ethical, although they are less characteristic than those discussed below.

When we turn to the instrumental use of the trigger metaphor, the “dangerous” meaning is almost totally ignored and replaced by an amoral (though not necessarily immoral) link between small input and great output. The amplification of effect, typically advertised with the motto “half the work, double the achievement” (shi ban gong bei 事半功倍), becomes a practical source of advantage. In a time of intense of political and military struggle, this is, not surprisingly, an attractive idea promoted by counsellors, generals, and diplomats to win the support of territorial lords. Sometimes, the instrumental metaphors look very similar to ethical ones and may be easily confused with the latter:

故口者,機關也,所以開閉情意也。耳目者,心之佐助也,所以窺見姦邪Footnote 39

Therefore the mouth is a trigger and latch by which emotions and intentions are opened and closed. The ears and eyes are assistants of the mind, by which the wicked and the crooked are spied out.

明君治國,三寸之機運而天下定,方寸之基正而天下治。故一言正而天下定,一言倚而天下靡。Footnote 40

When the enlightened ruler governs the state, he turns a trigger of three inches and the world is settled, squares a foundation of a square inch and the world is in order. Thus if his single word is upright, the world is settled; if his single word is perverse, the world topples.

The first metaphor, from the rhetorical treatise Guiguzi 鬼谷子, looks just like the comparison between the mouth and the trigger in the Shuihudi manuscript. The emphasis here, however, is obviously on the persuasive power of speech rather than its danger. One should take full advantage of the mouth's ability to create emotional stirs and use it as a device for manipulation in court politics. What holds this power in check is the mind assisted by eyes and ears, but the use of these “assistants” is not for any moral purpose either. The second metaphor, which closely resembles the one in “Great Learning,” comes from an extant fragment of the minister and political philosopher Shen Buhai 申不害 (c. 400–337 b.c.e.), who is known to have put in place one of the first legalist reforms in the state of Han. What Shen Buhai seeks to demonstrate with this metaphor is how a single person can govern the whole state in a time of crisis and frequent usurpation. With the collapse of the old aristocratic order, the territorial lords need to look for new forms of effective control that might help secure their increasingly fragile position. The trigger metaphor itself does not constitute a specific solution, but it opens up a conceptual space in which family bonds are replaced by a mechanical conception of leverage as the secret to stable government.

In military strategy, the trigger metaphor plays a similar role by enabling a conception of how a small army can defeat a large army. As mentioned above, the fifth century b.c.e. saw not only the spread of the crossbow trigger technology but also the emergence of war experts who were probably the first to use the trigger metaphor in the instrumental sense. If greater force can be controlled by little effort with the trigger mechanism, then, by analogy, there must be some kind of mechanism by which the few can gain strategic advantage over the many. Among the vast number of examples of this sort, I pick the following one that offers a compendium of the kinds of “triggers” that can be utilized in a campaign:

吳子曰:「凡兵有四機:一曰氣機,二曰地機,三曰事機,四曰力機。三軍之衆,百萬之師,張設輕重,在於一人,是謂氣機。路狹道險,名山大塞,十夫所守,千夫不過,是謂地機。善行間諜,輕兵往來,分散其衆,使其君臣相怨,上下相咎,是謂事機。車堅管轄,舟利櫓楫,士習戰陳,馬閑馳逐,是謂力機。」Footnote 41

Master Wu said, “In general, warfare has four [kinds of] triggers: the trigger of vapor, the trigger of terrain, the trigger of espionage, and the trigger of force. Amid the three armies and within the myriad hosts, the deployment of light and heavy troops depends on one man. This is called the ‘trigger of vapor.’ Narrow roads and perilous ways, famous mountains and great obstructions: what ten men guard cannot be passed by one thousand men. These are called the ‘trigger of terrain.’ Skillfully using spies, sending light troops back and forth to split up the multitude of the enemy force, making the enemy's ruler and ministers resent each other and higher and lower ranks reproach each other. These are called the ‘trigger of espionage.’ The chariots having solid axles and secure linchpins, the boats having well-suited rudders and oars, the soldiers being familiar with the battle formations, and the horses being skilled in galloping and pursuing, these are called the ‘trigger of force.’”

This list does not exhaust the possible kinds of strategic advantage proposed in early Chinese military thought, but it is a good summary of the range of things being considered. To highlight the metaphor, I preserve the “trigger” translation of ji even though it may seem awkward in many places. While “the trigger of terrain” does not make any sense in English, in the original text it means the topographical advantage of a piece of land, by occupying which ten men can defend themselves against a thousand. It is unclear why the first one is regarded as the “trigger of vapor,” but clearly it is something by which the general controls the three armies. The third one, espionage, is a kind of trigger because it fits with the “small input, great output” conception of ji by bringing victory without much physical struggle. Finally, the trigger of force means the material equipment and discipline of the army that may increase the efficacy of ordinary military action. The army with better equipment and discipline is likely to prevail over the other side even if the numbers are the same.

In medical literature, the trigger metaphor is used for a therapeutic technique in acupuncture. It helps to conceptualize why the piercing of a fine needle can have such power that it cures diseases. The underlying idea is that if the therapist applies the needle to the subtle “trigger” of the disease, the effect produced by it can be decisive. In the first dialogue from the first chapter of the medical classic Ling shu 靈樞 or Numinous Axle, the fundamental principle of acupuncture is explained as follows:

刺之微在速遲。麤守關,上守機。機之動不離其空。空中之機,清靜而微。其來不可逢,其往不可追。知機之道者,不可掛以發。不知機道,扣之不發。Footnote 42

The subtlety of piercing lies in doing it fast or slow. The crude method concentrates on the latch, while the advanced method concentrates on the trigger. The movement of the trigger never leaves empty spaces. The trigger in empty spaces is pure, quiet, and subtle. Its coming cannot be met, while its going cannot be chased. One who knows the way of the trigger [knows that it] cannot be off by a single hair. One who does not know the way of the trigger withholds and does not apply [the needle].

Again, at the cost of some awkwardness, I translate guan and ji literally as “latch” and “trigger” to highlight the metaphor. This passage draws a distinction between the crude and the advanced method, to which the two metaphors correspond. Their difference lies in whether the therapist focuses on substantial morphological joints or “latch” of the body or dynamic movements of vapor (qi) and blood in empty spaces. This is why the so-called “trigger” is described as “pure, quiet, and subtle.” The trigger metaphor plays a double role here. First, as noted above, the very use of the metaphor makes it less incredible that acupuncture can be a viable method. In this sense, the “trigger” is a critical turning point in the movement of vapor, which by seizing the therapist can effect a major change in the patient's body. Second, together with the latch metaphor, it differentiates the subtle skill of catching the tide in vapor circulation from the piercing of fixed spots. In this sense, ji can also be translated as “opportune moment,” a meaning probably derived from the experience of waiting for the correct time to pull the trigger. By analogy, piercing is a kind of aiming, or finding the opportune moment in the periodic rhythm of vapor. Since the circulation of vapor is a spontaneous, never-ending process, one cannot meet the fleeting moment before it comes or chase it after it has passed.

Having sketched the divergence of the metaphor, I shall now turn to other images infused with the same meaning. By taking ji as the prototype of a metaphorical scheme that includes a large group of images, I do not mean to suggest that it is necessarily the earliest in time. The reason for its primacy is that nowhere else do we find the ambiguity of “subtle” and “dangerous” explicitly assigned to a single word as its standard meanings. Since synonymous images are numerous, I shall give only a few examples that I find particularly relevant. There is no better place to start than the early imperial syncretic anthologies, which often contain direct evidence of metaphorical convergence due to their hybrid nature. The first example is the convergence of the trigger, the latch (guan 關 or jian 鍵), and the axle (shu 樞) in a passage from the Shuo yuan 說苑 or Garden of Sayings:Footnote 43

口者,關也。舌者,機也。出言不當,四馬不能追也。口者,關也。舌者,兵也。出言不當,反自傷也。言出於己,不可止於人。行發於邇,不可止於遠。夫言行者,君子之樞機。樞機之發,榮辱之本也。可不慎乎?故蒯子羽曰:「言猶射也。栝既離弦,雖有所悔焉,不可從而追已。」Footnote 44

The mouth is a latch, the tongue is a trigger. If uttered words are not appropriate, even four horses cannot catch them. The mouth is a latch, the tongue is a weapon. If uttered words are not appropriate, they return and hurt oneself. Words travel out from oneself, but they cannot be stopped at others. Actions travel out from nearby, but they cannot be stopped at distant places. Words and actions are the axle and trigger of the gentleman. The shooting of the axle and trigger is the root of honor and disgrace. How can one not be careful? Therefore Master Kuai Yu said, “Speaking is like shooting. Once the end of the arrow has left the string, one cannot pursue and catch it even though one regrets.”

The Shuo yuan passages are obviously a collection of smaller chunks of texts, two of which we have seen above; thus the convergence here is a familiar one. The axle can be either a door pivot or the hub of a wheel (the trigger turns around a static point too). As the motionless center of a rotating circle, it effortless “governs” the rotation. The latch, to which the mouth is likened due to its ability to “lock up” words shot by the tongue, “governs” entrance and exit through the door.

As for the instrumental side, there is a complex metaphorical blend in the “Zhu shu” 主術 or “The Art of Rulership” chapter from the Huainanzi:

攝權勢之柄,其於化民易矣。衛君役子路,權重也。景、桓臣管、晏,位尊也。怯服勇而愚制智,其所託勢者勝也。故枝不得大於榦,末不得強於本。言輕重小大有以相制也。若五指之屬於臂也,搏援攫捷,莫不如志,言以小屬於大也。是故得勢之利者,所持甚小,所任甚大。所守甚約,所制甚廣。是故十圍之木,持千鈞之屋。五寸之鍵,制開闔之門。豈其材之巨小足哉?所居要也。Footnote 45

Holding the handle of leverage makes it easy to transform the people. That the ruler of Wey took into service Zilu was because [the ruler's] leverage was heavy. That Dukes Jing and Huan of Qi made ministers of Guan Zhong and Yan Ying was because [the rulers’] position was exalted. That the cowardly can subdue the brave and the foolish can control the wise is because the positional advantage on which they rely prevails. Therefore that the limbs of a tree cannot be larger than its trunk and that the branches cannot be stronger than the root means that light and heavy, large and small, have that by which they control each other. It is like the way the five fingers are attached to the arm. They can grasp, extend, snatch, or grab, and nothing happens other than as we intend it. This is to say, the small are appendages of the large. Thus to have positional advantage means what one holds is very small, but what one manages is very large; what one guards is very compact, but what one controls is vast. Thus a tree trunk ten hand spans in circumference can support a roof weighing a thousand jun, and a latch five inches long can control the opening and closing of a door. How can this be just a matter of the size of the materials? The position they occupy is crucial.

The Huainanzi brings together four images that can be sorted into two pairs. On the one hand, the two limb metaphors (that is, tree and human limbs) are meant to show that the small/weak can only be controlled by the large/strong. On the other hand, the pillar and latch (both are parts of a room) metaphors show that the small can control the large. Although the two pairs seem contradictory at first sight, they are actually two sides of the same coin that flips around the core notion of “leverage” or “positional advantage.” The weak is controlled by the strong under normal conditions, but positional advantage may cause a reversal in power dynamics. Therefore, the reversal is only a special, manipulated case of the physical law that the strong always prevails. The four images are carefully chosen to distinguish the extraordinary from the ordinary, as the first two are biological organisms while the last two are technical artifacts.

To this metaphorical scheme we may add two more artifacts, the pulling rope of the fish net (gang 綱) and the chariot pin (ni 輗). These two are never grouped with the trigger metaphor in the same context, but they nonetheless have the same meaning. The Hanfeizi explains the art of rulership in terms of the fish net rope metaphor:

搖木者一一攝其葉,則勞而不徧。左右拊其本,而葉徧搖矣。臨淵而搖木,鳥驚而高,魚恐而下。善張網者引其綱。若一一攝萬目而後得,則是勞而難。引其綱而魚已囊矣。故吏者,民之本綱者也。故聖人治吏不治民。Footnote 46

If someone who wants to shake a tree pulls each leaf one after another, he works hard yet cannot shake the whole tree. If he shakes the stem back and forth, all the leaves will be shaken. If one shakes the tree by an abyss, birds will be scared and fly up and the fish will be scared and swim down. One who is skillful in spreading a net draws the pulling rope. If he pulls each mesh one after another so as to get the net, he works hard and meets difficulties. If he draws in the net by the pulling rope, the fish will have been trapped. Therefore, officials are the stem and pulling rope of the people. Therefore the sage governs the officials but not the people.

The gang is a thick rope on the fish net by which one pulls up the entire net with ease. Its modern Chinese meaning “outline” is derived from this metaphor, for the writer manages the contents or “meshes” (mu 目) of her work with the outline. Like the trigger, the gang is a labor-saving device for handling difficult tasks. It is blended with two tree metaphors, although there is no contrast between natural and technical imagery here.

The chariot pin is a piece of wood that fastens the vertical shaft to the horizontal drawbar. Small as it is, the pin is the only component of the chariot that connects the vehicle to its power source. In a famous story from the Hanfeizi, the craftsman philosopher Mo Di 墨翟 (c. 470–391 b.c.e.) is credited with having invented a wooden kite that flies on its own. When praised for his amazing toy, Mozi rated his skill below the artisans who made the chariot pin:

墨子為木鳶,三年而成,蜚一日而敗。弟子曰:「先生之巧至,能使木鳶飛。」墨子曰:「吾不如為車輗者巧也。用咫尺之木,不費一朝之事,而引三十石之任。致遠力多,久於歲數。今我為鳶,三年成,蜚一日而敗。」惠子聞之曰:「墨子大巧。巧為輗,拙為鳶。」Footnote 47

Mozi made a wooden kite, which took him three years to finish. After flying for one day it broke. His disciples said: “The master's skillfulness is supreme. He can make the wooden kite fly.” Mozi said: “I'm not as skillful as the maker of the chariot pin. He uses a piece of wood eight inches long, not wasting a single morning and yet pulling a load of 30 dan. It endures long distance and lasts for many years. Now I spent three years on making the wooden kite which broke after flying for one day.” Huizi heard this and said: “Mozi was exceedingly skillful, [for he] regards the making of the chariot pin as skillful and the making of the wooden kite as clumsy.”

Mozi's description of the chariot pin once again illustrates the semantic structure of “small input, great output”—the object is only “eight inches long” and can be made in “a single morning,” and yet it “pulls a load of 30 dan, endures long distance and lasts for many years.” In contrast, the wooden kite takes three years to make but flies for only a day. Here, the chariot pin does not appear as a metaphor. Its metaphorical use is found in the Analects:

子曰:「人而無信,不知其可也。大車無輗,小車無軏,其何以行之哉?」

The Master said: “I do not see how a person devoid of trustworthiness can be acceptable. When a large or small chariot has no pin for its shaft, how could it possibly be driven?” (2.22)

Kongzi uses the chariot pin as a metaphor for trustworthiness, without which the society is doomed to malfunction just like a chariot detached from the horses. Elsewhere, Kongzi seems to take trustworthiness similarly to be a kind of “foothold” in a society when he says that “without trustworthiness the people cannot stand” (12.7, min wu xin bu li 民無信不立). If the rope metaphor in the Hanfeizi is instrumental, the chariot pin metaphor in the Analects is ethical. The ethical meaning in this case is slightly different from those discussed above. It does not warn but reminds people of the centrality of trust in social interactions.

At the end of this section I would like to consider an interesting case that defies neat classification into either the ethical or the instrumental group. It is an anecdote from the Zhuangzi, quoted only partially here:

夔憐蚿,蚿憐蛇,蛇憐風,風憐目,目憐心。夔謂蚿曰:「吾以一足趻踔而行,予無如矣。今子之使萬足,獨奈何?」蚿曰:「不然。子不見夫唾者乎?噴則大者如珠,小者如霧,雜而下者不可勝數也。今予動吾天機,而不知其所以然。」蚿謂蛇曰:「吾以眾足行,而不及子之無足,何也?」蛇曰:「夫天機之所動,何可易邪?吾安用足哉!」Footnote 48

The unipede envied the millipede, the millipede envied the snake, the snake envied the wind, the wind envied the eye, and the eye envied the mind. The unipede said to the millipede, “I hop along on my one foot but barely manage. Now you are able to control your myriad feet. How do you do it?” The millipede said, “It's not like that. Haven't you ever seen a person spit? He just gives a hawk and out it comes, some drops as big as pearls, some as fine as mist, raining down in a jumble of countless particles. Now I move my heavenly trigger but have no idea how it is so.” The millipede said to the snake, “I move along on all these feet of mine, but it is still no match for the way you do it with no feet. How come?” The snake said, “As for what the heavenly trigger moves, how can I make any changes to it? What use would I have for feet?”

The first sentence mentions six figures and implies five potential conversations, but as it stands the anecdote stops at the third conversation between the snake and the wind. The first two conversations quoted here pivot on the term tianji, variously translated as “heavenly mechanism” (Watson), “natural inner workings” (Mair) and the capitalized “Heavenly Impulse” (Ziporyn).Footnote 49 Most translators seem to take ji in its general sense as “mechanism,” but the question is whether the “trigger” meaning is connoted in addition to the general sense. I believe the answer is yes. Note that the millipede introduced the idea of tianji together with the spitting analogy when it tried to explain the one secret of controlling many feet easily. While the unipede gave direct commands to its single leg, the millipede pulled the “heavenly trigger” (which I take to mean that the trigger is not of artificial design) and the myriad feet were coordinated all by themselves. From the millipede's point of view, the unipede misunderstood the nature of the activity (“It's not like that”), because the former did not really “control” (shi 使) the feet in the sense understood by the latter (that is, giving direct orders). When it was the millipede's turn to be amazed, the attempt to control was further diminished by a switch of the grammatical position of tianji from the object to the subject. It was no longer the snake's “I” that took command, but the tianji itself. The distinction between the controller and the controlled dissolved in the snake's whole-body, slithering movement.

What role does the trigger metaphor play here? As in the above examples, it is a practical metaphor for a certain kind of action, but the action here is the unusual Daoist wuwei or “non-action.” For this reason, we cannot simply label it as an instrumental use even though the metaphor is obviously picked for its “effortless” meaning. As a preliminary answer to the question of wuwei, offered only at the initial stage, the tianji provides a metaphorical model for wuwei as “effortless action,” but such a model would soon be modified and then rejected in favor of more advanced understandings. Following the snake, the wind represents a higher level of non-action because, unlike the snake that still has a body, it is formless. The eye represents yet another level because it does not have to travel from one place to another so as to reach its target. The mind resembles the eye in this regard, but there is no spatial limit to its reach. The last two levels are not even mentioned, probably because they are beyond language. Embedded in this scheme of progressive attainments, the trigger metaphor is both instructive and inadequate. It shows that while non-action is effortless, it cannot be defined by effortlessness alone. All this seems to show that we are dealing with a different type of metaphorical divergence, one between, as it were, purposive Daoism and contemplative Daoism.Footnote 50 By limiting the trigger metaphor to the first stage, the story distinguishes its own approach to non-action from the instrumental approach that one commonly sees in what has been traditionally labelled legalism.

CONCLUSION: JI AS AN EPOCHAL METAPHOR

What the crossbow trigger triggers in the Warring States intellectual landscape is not just a single metaphor, but a complex metaphorical scheme that consists of two interpretive tendencies (ethical and instrumental), a web of associated images (both natural and technical), and multiple levels of ambiguities (material, semantic, and intellectual). The complexity alone bespeaks its significance and fundamentality as a non-abstract vehicle of thought. In fact, it is nothing but the mechanical imagery that provides a common linguistic and cognitive form for organizing a wide range of heterogeneous life-world situations, from the precariousness of rhetorical speech at court to the vulnerability of an outnumbered army in battle. This is perhaps why classical thinkers kept feeding new images to this metaphorical scheme.

From a metaphorological point of view, ji is certainly an epochal metaphor that emerges and flourishes in an age of great upheaval. Although the word ji has a much earlier origin, as a metaphor it rises to prominence during the Warring States period as a result of the crossbow trigger's popularity in warfare. It is not one of those conventionalized metaphors analyzed by conceptual metaphor theorists, but a novel metaphor based on a new technology, an intellectual innovation with which philosophers try to navigate through their unprecedented historical situation. The crossbow trigger would almost be a natural device for conceptualizing a society in disorder. To appreciate its suitability, we only need to look at a modern parallel—the butterfly effect metaphor in chaos theory. In both cases, the metaphor foregrounds the sensitive dependence of consequences on initial conditions. The striking similarity suggests that the use of such a metaphor for chaos is not the idiosyncratic choice of a particular culture.

Yet the analogy only takes us so far. The butterfly effect metaphor is used to illustrate rather than to conceptualize; it belongs to a scientific theory about natural processes. The trigger metaphor, however, pertains in one way or another to human life and action in the vast majority of cases. In describing the function of the trigger, one has to make frequent use of causal language, but causality plays virtually no role in its metaphorical meaning. What captures the attention of classical thinkers is the asymmetry between cause and effect, as well as the inherent danger and advantage in the mechanism, but not the link itself. Even in medical literature, where a causal explanation is desirable, the metaphor is not used to provide any specific theory for the workings of vapor, but to teach and recommend a therapeutic technique. With only a few exceptions, the metaphor hinges on the practical utility of trigger and machine in maximizing benefit or harm. To use the “life as seafaring” metaphor discussed by Blumenberg in his Shipwreck with Spectator (1979), the metaphorics of the trigger would be an example of “shipwreck without spectator”—there is no dry land, or theoretical vantage point, from which a spectator (theoros) may calmly view the perilous voyages of others at sea.Footnote 51

This brings us back to the pragmatic orientation of metaphorology. Blumenberg, in his analysis of the metaphorics of the “naked” truth, claims that the metaphor says surprisingly little about the concept of truth that is supposed to be “naked” by definition, but it “projects conjectures and evaluations of a very complex kind over the top of the concept.” In our culture the notion of nakedness splits into a positive sense of uncovering a deception and a negative sense of shameless unveiling.Footnote 52 The naked truth metaphor carries with it not a semantic definition of truth, but ambivalent attitudes towards the cultural practice of decoration. In a similar vein, the metaphorology of ji belongs not only to an intellectual history, but also to a cultural and historical psychology. What the trigger metaphor carries is not just a semantic ambiguity, but also ambivalent attitudes towards the very experience of instability that defines the Warring States age. Ultimately, the divergent meanings of the crossbow trigger reveal that for some, the collapse of an existing order means a crisis (weiji 危機), a disturbing deviance from the norm, while for others, it means an opportunity (jihui 機會), a preliminary step towards a new power structure.