INTRODUCTION

A new account of the “Nine Provinces” (Jiu zhou 九州) discovered in the Rong Cheng shi 容成氏 (Mister Rong Cheng [?]) manuscript of Chu provenance dated to the late fourth century b.c.e. has resulted in the immediate addition of this text to the list of the key early Chinese sources describing terrestrial space. Its importance is enhanced by the general rarity of manuscripts among early Chinese terrestrial descriptions, its description of the “Nine Provinces” being the only manuscript version known to date. However, it has close affinity with a wide spectrum of transmitted texts and is distinguished by its combining of diverse spatial concepts with the central role of draining excess waters. Its eclecticism thus throws light on transmitted versions of the “Nine Provinces” more than it manifests any radically new or specifically Chu traits. This conclusion is true with respect to the description proper of the “Nine Provinces” and is based on parallels with other texts. In this study I reassess this conclusion with respect to the context of this passage in the Rong Cheng shi, challenging an initial impression of its lack of any Chu flavor.

While the parallels of the new description of the “Nine Provinces” with those in transmitted texts has attracted considerable scholarly attention, its relation to other issues concerning terrestrial space in the Rong Cheng shi has not yet been studied. Before discussing the spatial issues in this manuscript, I shall first revise all the reconstructed sequences of its slips (Introduction). Then I shall focus on the especially controversial slip 31, which appears to be of primary relevance to spatial concepts (Part I). It contains a reference to a “cosmograph”-like pattern followed by a description of managing landscape features, beginning with waterways. I shall discuss the place of this pattern in early Chinese cosmography, in particular the link of the “policy statement” on the predominance of waters to the version of the “Nine Provinces” in the manuscript. I suggest that, from the point of view of the revealed spatial concepts, slip 31 should be placed prior to the group of slips that describe terrestrial disasters that preceded the establishment of the “Nine Provinces.” Having concluded that the predominance of waters is the distinguishing feature of the representation of terrestrial space in the manuscript, and having compared the manuscript with another cosmographical manuscript of Chu provenance contemporary with the Rong Cheng shi, the Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1 (c. late fourth century b.c.e.), I suggest that this feature may be characteristic of Chu descriptions of terrestrial space. My main attention is focused on solving the spatial problem in the conclusion to the “Nine Provinces,” which up to now has been noted only in passing as somewhat confusing (Part II). It provides a summary of structuring terrestrial space through waterways, and cuts the space thus mapped into southern and northern halves along the Han River. I argue that this unusual usage of the Han River as the central axis implicitly shifts the mapped area to the South, and thus conveys a Chu view of space, while explicitly respecting the spatial framework of transmitted descriptions of the “Nine Provinces.” In addition to philological analysis of the descriptions of terrestrial space, I apply an innovative method of investigation of them through landmarks. Landmarks found in these descriptions, including the Han River, will be explored as elements of what can be tentatively defined as relational, positional, or diagrammatic maps. Such maps are characteristic of traditional Chinese cartography. The earliest specimens covering the entire imperial realm date from the twelfth century. Although the majority of these maps appeared as part of commentaries on early terrestrial descriptions and are products of a continuous tradition of representing space, they are rarely taken into consideration in studies of early texts. Finally, I discuss a correlation between structuring terrestrial space through waterways and the concept of Yu's personal and exhausting physical engagement in hard work (Part III).

The description of the “Nine Provinces” with the related preceding and following slips—slips 31 and 23-15-24-25-26-27-28-29—is provided in the Appendix).

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE RONG CHENG SHI MANUSCRIPT AND CONCURRING RECONSTRUCTIONS OF THE SEQUENCE OF ITS SLIPS

The Rong Cheng shi belongs to the Shanghai Museum Bamboo Slips Collection (Shangbo cangjian 上博藏簡). The corpus was purchased by the Shanghai Museum in 1994 in Hongkong, and the precise location and date of this find are still unknown. Compared to manuscripts discovered in situ, looted manuscripts pose two major research problems—the lack of archeological context and, thus, their being, by definition, of questionable authenticity.Footnote 1 There is general consensus that the Shanghai Museum corpus includes genuine manuscripts originating from a Chu aristocratic tomb closed shortly before the Chu court was obliged to leave the capital at Ying 郢 in 278 b.c.e.Footnote 2 No data contesting this point of view has been found to date.

The Rong Cheng shi is one of the largest (some 2,000 characters) and best preserved manuscripts in the corpus.Footnote 3 Its title is found on the verso of the last among the originally identified 53 surviving slips of the manuscript.Footnote 4 It is written as song cheng di 訟城氐, commonly accepted to stand for Rong Cheng shi 容成氏—Mister Rong Cheng.Footnote 5 Rong Cheng shi is one the sage rulers of High Antiquity.Footnote 6 The manuscript provides an overview of Chinese history, from the mythical sage rulers to the establishment of the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046—256 b.c.e.).Footnote 7 While having multiple parallels with transmitted texts describing the same historical periods and events, the manuscript is distinguished by its special emphasis on the “supremacy of power transfer through the ruler's abdication in favor of a worthier successor.”Footnote 8

The investigation of the content of unearthed manuscripts on bamboo slips depends on solving two basic technical problems—the transcription of characters, and the restitution of the sequence of slips. Though there are relatively few variations in the transcriptions of the characters of the Rong Cheng shi manuscript, the sequence of its slips still remains a highly controversial issue, even though this work is considerably facilitated by the narrative chronology. Once the slips of a manuscript have been arranged into a more or less meaningful sequence, the focus of scholarly discussion tends to move on from such basic technical problems to the content and the context of the manuscript, and unsolved techical issues fade into the background.Footnote 9 Instead of the common method of choosing one sequence and then discussing the content, I propose to discuss the content of the slips while considering all their possible arrangements. I shall demonstrate that this approach may provide conclusive arguments for determining the most plausible place for some controversial slips.Footnote 10

The first arrangement of the Rong Cheng shi slips and their transcription was proposed by Li Ling 李零 in the second volume of the Shanghai guji chubanshe edition of the corpus published in 2002.Footnote 11 Since then the sequencing of slips and transcription of certain characters have been continuously challenged.Footnote 12 Shortly after Li Ling's publication, Chen Jian 陳劍 substantially changed Li Ling's sequence:

Chen Jian

1–3, 35B, 4–7+43, 9–11+13–14+8+12+23+15+24–30+16–21+31–32+22+33–34+35A+38–41+36–37+42+44–53Footnote 13

Chen Ligui 陳麗桂Footnote 14 and Bai Yulan 白於藍Footnote 15 made further partial adjustments to the sequence, having restituted the succession of slips 21 and 22 proposed by Li Ling:Footnote 16

The articles surveying Chinese scholarship on the Rong Cheng shi by Sun Feiyan 孫飛燕 and Niu Xinfang 牛新房 distinguish the following main suggestions about the slips’ arrangements:Footnote 17

1) Chen Jian noticed that two damaged fragments, considered by Li Ling to constitute slip 35, are in effect pieces of two different slips, now referred to as slip 35A and slip 35B;Footnote 18

2) Dan Yuchen 單育辰 joins slips 15 and 24, arguing that these slips are pieces of one slip;Footnote 19

3) Guo Yongbing 郭永秉 links slips 31 and 32 with slips 4 and 5; Footnote 20

4) Guo Yongbing also proposes to insert slip 43, already advanced to the beginning of the text by Chen Jian, after slip 35A.Footnote 21

Niu Xinfang concludes his evaluation with a summarizing rearrangement of slips, where he proposes to distinguish eight coherent groups:Footnote 22

Niu Xinfang

I 1–3

II 35B + 43+7B

III 31–32+4–6+7A

IV 9–11+13–14+8

V 12+23+15=24–30+16–21–22

VI 33–34

VII 35A+38–41+36–37

VIII 42+44–53

Yuri Pines, the author of the first English translation of the manuscript, follows Chen Jian's sequence, with the exception of reinstating the place of slip 22 after slip 21, but expresses strong doubts about Chen Jian's placement of slips 31 and 32 (I distinguish them by italics):Footnote 23

Chen Jian/Pines

1–3, 35B, 4–7+43, 9–11+13–14+8+12+23+15+24–30+16–21–22+31–32+33–34+35A+38–41+36–37+42+44–53

Sarah Allan, who has provided a second translation of the manuscript with extensive commentary updated by recent studies, follows Guo Yongbing's sequence and the general consensus on reinstating Li Ling's sequence of slips 21–22; she also reinstates slips 36–37 before 38:Footnote 24

Guo Yongbing/Allan

1–3, 35B, 43, 31–32, 4–7, 9–11, 13–14, 8, 12, 23, 15, 24–30, 16–22, 33–34, 35A, 36–42, 44–53

In sum, each scholar who has tried to deal with the sequence of slips in the Rong Cheng shi has come up with more or less different suggestions about their arrangement. There are groups of slips the order of which is shared by the majority of scholars. These groups can be recognized as definitive sets. There are at the same time some errant slips, the placement of which differs, sometimes rather considerably, among the suggestions advanced.Footnote 25

PART I: THE “COSMOGRAPH” PATTERN AND PUTTING WATERWAYS FIRST IN CONSTRUCTING SPACE: REASSESSING SLIP 31

One especially controversial slip—No. 31—contains a “policy statement” for conceptualizing terrestrial space in the Rong Cheng shi. It is preceded by a description of a cardinally oriented twelve-fold pattern. Due to the conciseness of these references, neither the meaning of this spatial pattern, nor the significance of the “policy statement” have been fully appreciated in studies of this manuscript. Their profound implication emerges from an analysis within the broad context of early Chinese concepts of space derived from transmitted and manuscript texts. At the same time, the comparison of this passage with similar occurrences provides new arguments for determining the most plausible place of this slip in the Rong Cheng shi narrative.

Placements and Interpretations of Slip 31

Varying placements have been proposed for slip 31. Essentially there have been two approaches:

1) Li Ling, Chen Ligui, Bai Yulan, and Chen Jian associate slip 31 with Yu, whose deeds are featured around the middle of the manuscript.

2) Guo Yongbing and Niu Xinfang place slip 31 at the beginning of the manuscript, considering it to be part of the description of an ancient sage ruler named Youyu Tong 有虞通, who is not found in transmitted texts. Guo Yongbing identifies characters 又吴迵 on slip 5 with 有虞通, and further reconstructs the same name in a group of faint graphs on slip 32, which is damaged.

It should also be noted that some scholars regard slip 31 as a pair with slip 32, while others do not.

Yuri Pines follows the first approach in his translation, but he expresses doubts about its belonging to the “Yu part” of the manuscript and about the relationship to slip 32.Footnote 26 Sarah Allan's translation relies on Guo Yongbing's hypothesis about Youyu Tong and his placement of slip 31 at the beginning.Footnote 27

The passage in question occupies almost the whole of slip 31. Sarah Allan claims that it advocates musical harmony:Footnote 28

Rong Cheng shi, slip 31, beginning from character No. 2; translation by Allan:

Allan focuses her attention on the musical scale, which may be implied in the phrase jiu sheng zhi ji 救聲之紀. Allan translates it as “seeking a guide for the sounds (of a musical scale)” and identifies the character gao 俈 with gong 宮 (“tone”). In this case the total of twelve gao corresponds to the twelve-pitch scale 十二律 shi'er lü used in ancient Chinese music.

Allan (along with Li Ling, Chen Jian, and Guo Yongbing) begins the passage with the second character on slip 31, which she reads, having accepted one among its identifications, as shi 始, and ends it with the first character on slip 32, which is generally transcribed as ru 入 (“to enter, to penetrate”). Ru used as a predicate with forests makes a good match with sheng 陞 (“to mount, to ascend”) used as a predicate with mountains—gao shan sheng, zhen lin ru 高山陞,蓁林入 (“high mountains became ascendable, dense forests penetrable”). One issue with this reading is the fact that after ru 入follows yan 焉 (= yu zhi 於之). The combination of these two characters is quite common in early Chinese texts. It means “to enter somewhere” and as a rule is found at the end of a phrase. Ru yan at the beginning of slip 32 looks more likely to be the ending of another passage; so some scholars, including Bai Yulan and Chen Ligui, separate slips 31 and 32.

Although Yuri Pines in his translation of the Rong Cheng shi accepts a successive arrangement of slips 31 and 32, he tries to solve the problem of their mismatch by calling attention to the damaged nature of slip 32, suggesting that some neighbouring slips might be missing. He translates the beginning of slip 32 as the end of a lost piece of text: ru yan, yi xing zheng 入焉,以行政 “[he] entered there to perform administrative tasks.” Pines also feels that no satisfactory identifications of the character gao have been made and cautiously translates it as some type of ritual.Footnote 29 He gives credit to the musical aspect, but does not exaggerate it, and better fits the transmitted written tradition in translating the context:Footnote 30

Rong Cheng shi, slip 31, beginning from character No. 3; translation by Pines:

I give preference, with some minor amendments of my own, to Pines’ interpretation of the passage:

Rong Cheng shi, slip 31, beginning from character No. 3; translation by the author of this article:

A Twelve-to-Four Pattern for Tailoring Space

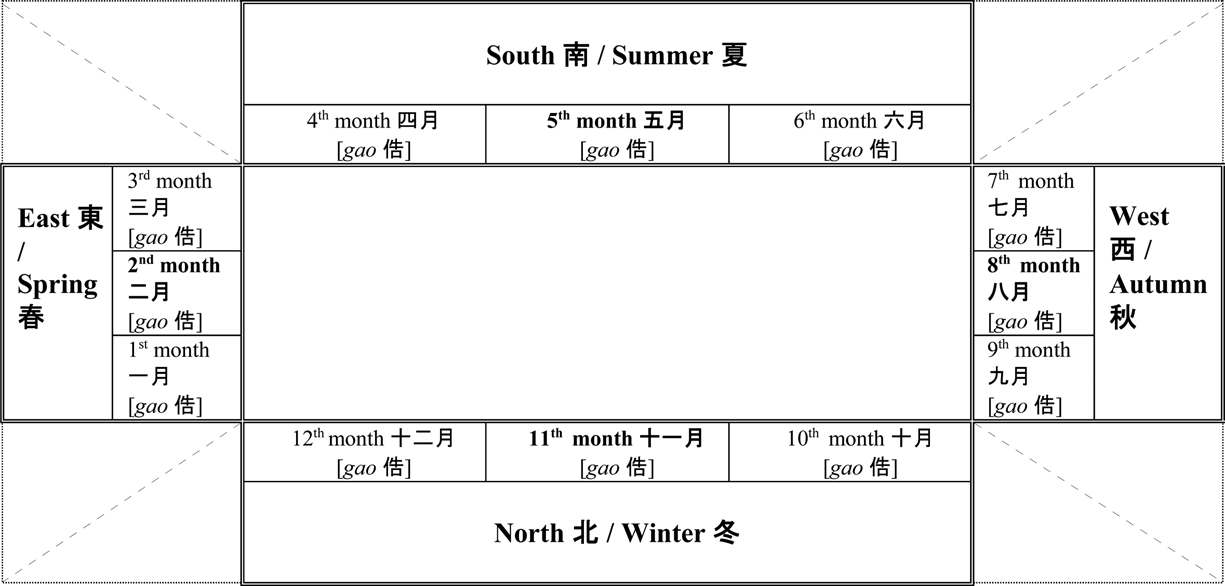

According to both interpretations, this passage first of all describes structuring space into twelve cardinally oriented units—three at each of the four cardinal directions. This spatial structure underlies all the other possible correlations, including the twelve-pitch scale. At the same time, the character ji 紀, designating here the order of sounds, in contemporary transmitted texts is systematically used in relation to duodecimal temporal cycles, in particular the system of twelve months of the year, the “Shi'er ji” 十二紀 (Twelve Monthly Records) section of the Lüshi chunqiu 呂氏春秋 (Springs and Autumns of Mister Lü, compiled shortly before 239 b.c.e.) and its counterpart, the “Yue ling”月令 (Monthly Ordinances, c. second century b.c.e.) chapter of the Li ji 禮記 (Records of Ritual, compiled about the first century c.e.), being the loci classici for the duodecimal calendar texts.Footnote 32 The twelve months arranged into four seasons correlated with the four cardinal directions constitute the Chinese cosmographical conception of space-time, which is in the first place evoked by the twelve-to-four pattern. Figure 1 shows the spatio-temporal deployment of the twelve months with a correlated cardinally oriented arrangement of twelve gao.

Figure 1 Twelve months of the year arranged into four seasons correlated with the four cardinal directions with superimposed twelve gao 俈.

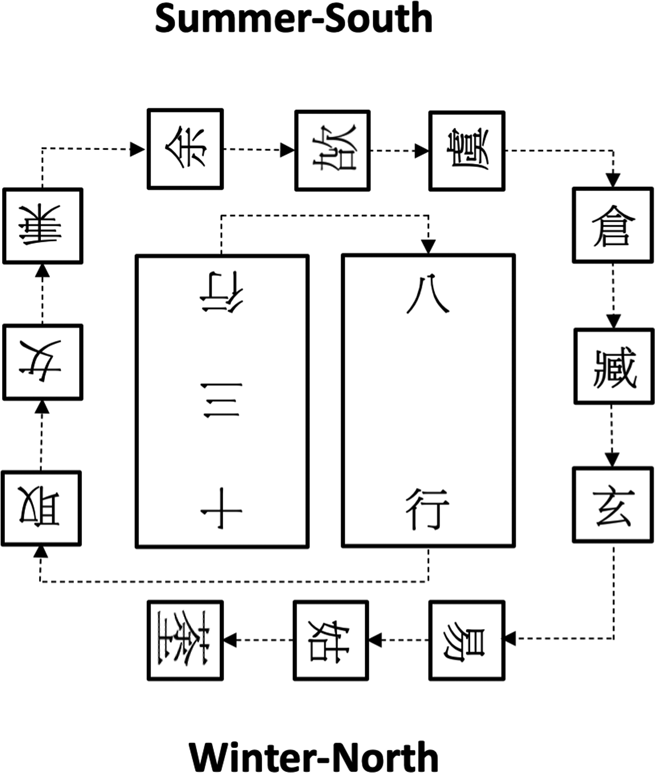

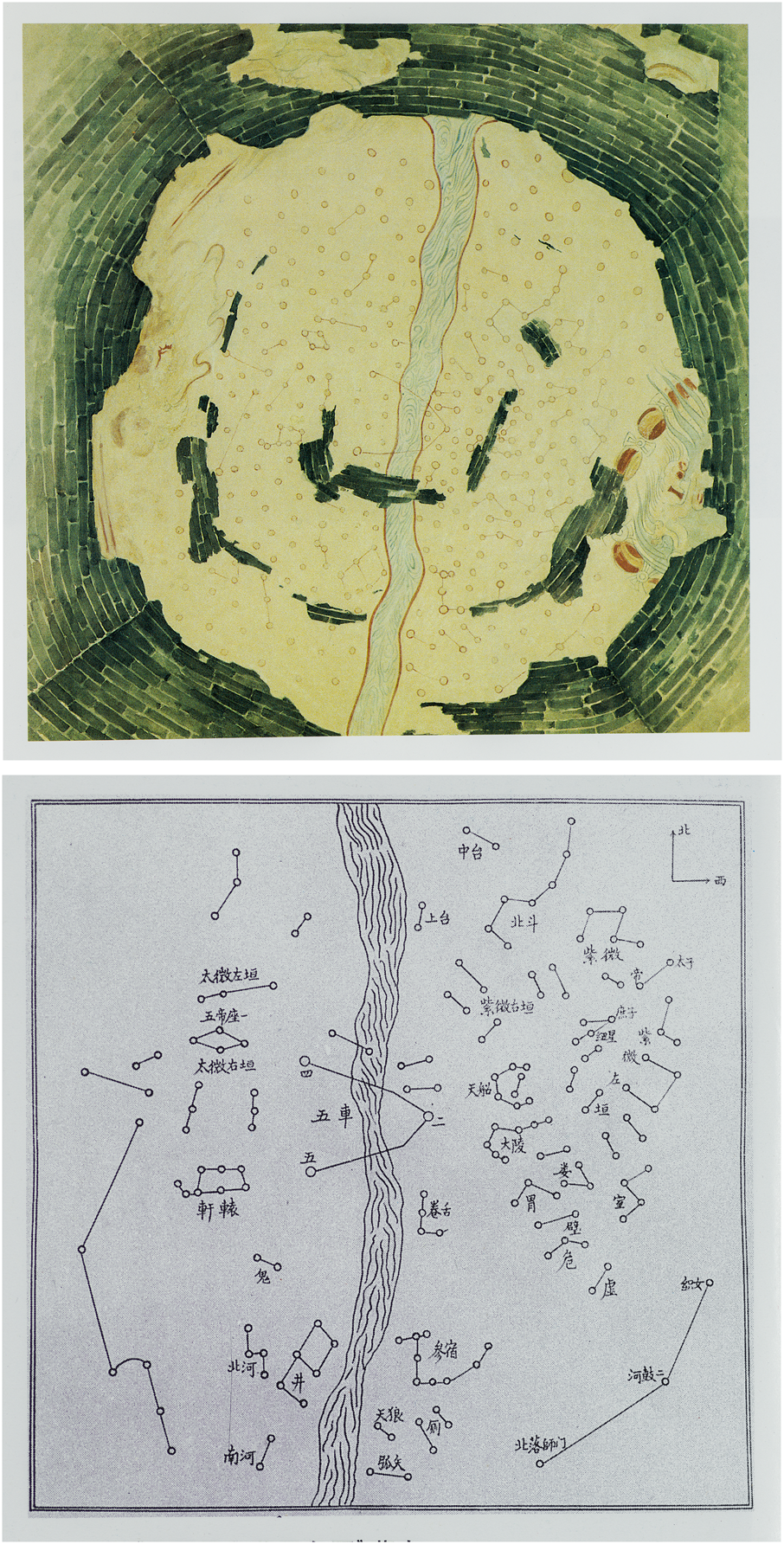

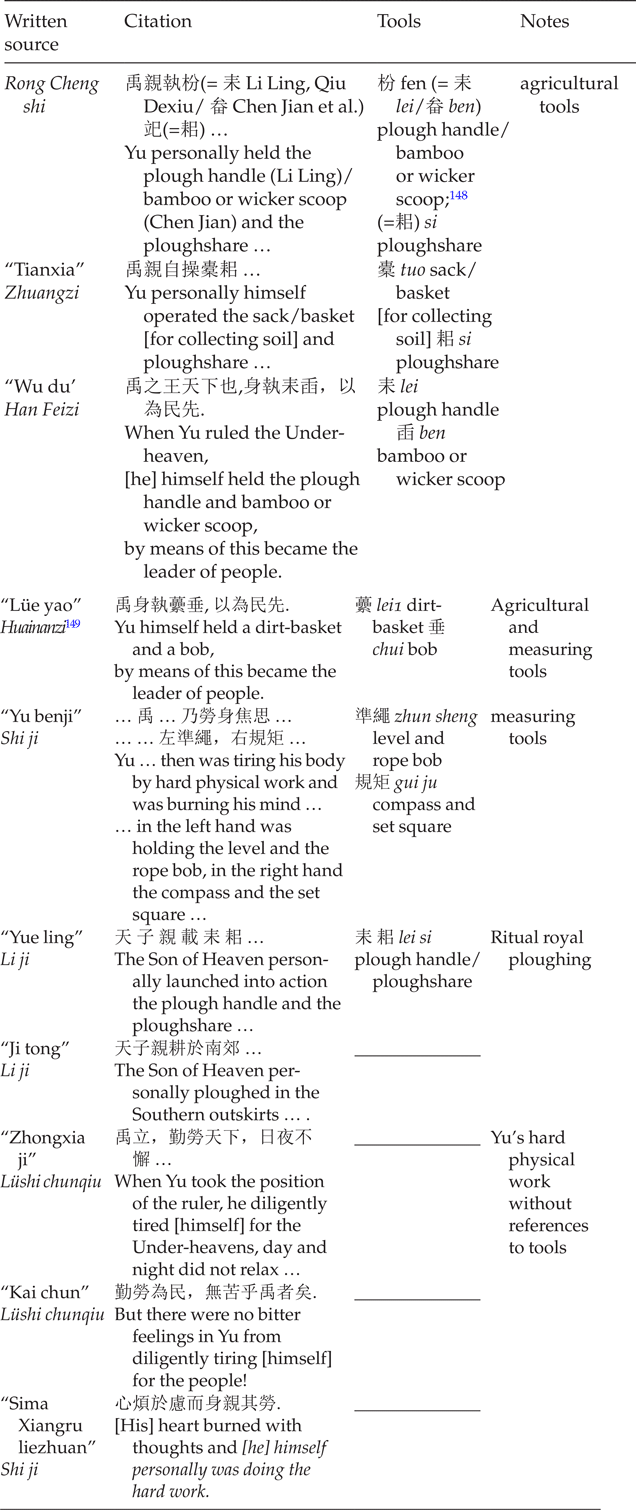

One could argue that the scheme in Figure 1 is a reconstruction and there are other possible ways to array the twelve months of the year. However, their pictorial representation, according to the pattern above, is found in another manuscript of Chu provenance roughly contemporary with the Lüshi chunqiu and the Rong Cheng shi, the so-called Chu Silk Manuscript, recently re-labelled as Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1 (c. 47 × 38.7 cm in its present condition, estimated original size 48 × 40 cm;Footnote 33 c. late fourth century b.c.e, unearthed by grave robbers sometime between 1934 and 1942 at Zidanku 子彈庫, Changsha, Hubei province). This has been studied intensively since the middle of the twentieth century. Among milestone studies are those by Li Ling, who not only takes notice of its peculiar spatio-temporal layout, which combines textual passages and pictures, but also calls attention to its meaning and a functional significance.Footnote 34 Having first explored various shapes of the shitu 式圖, which he translates as “a diagram of shi 式 (or cosmic model),”Footnote 35 Li Ling establishes the link between the layout of Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1 and cosmological devices shipan 式/栻盤, commonly referred to as divining or cosmic boards or cosmographs. The divining or cosmic board or “cosmograph” has a square base plate with a rotating disc on top, representing Earth and Heavens, respectively.Footnote 36 He supports his point of view with two diagrams, which demonstrate their parallels. The first diagram shows the arrangement of the manuscript's textual units supplied with indications to the reading direction of each unit and their tentative sequence—clockwise from the center to periphery. This requires the rotation of the manuscript by its “user” and makes the diagram a process-oriented scheme (Figure 2a; center: two long textual passages written inversely with respect to each other, one comprised of thirteen and the other of eight columns. Margins: twelve short textual passages related to the monthly divinities, the names of which are placed in the reading direction of the respective passage).Footnote 37 This diagram highlights the non-linear textual structure of the manuscript, which is especially valuable due to its being the original, not reconstructed textual arrangement.Footnote 38 The second diagram shows the pictorial images in a square pattern, that is, the twelve monthly divinities, three on each side of the manuscript, with four trees placed in the corners (Figure 2b; a group of three divinities at each side of the manuscript corresponds to a season. Cardinal orientation is not noted explicitely, but may be reliably derived from its correlation with the seasons).Footnote 39 The same pattern is found on the square bottom (=Earth) plate of the so-called Liuren 六壬 type of cosmograph, on which the twelve cyclic signs (Earth branches) are arranged within the second square zone from the outside (Figure 2cFootnote 40).

Figure 2a General arrangement of Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1 and its tentative reading sequence. Reproduced from Li Ling, Chuboshu yanjiu 楚帛書研究 (Shanghai: Zhongxi, 2013), 29, and re-oriented with the South on top; estimated size of the original diagram c. 40 × 40 cm.

Figure 2b Cosmograph-like square pattern marked by the twelve monthly divinities and four corner trees in Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1. Reproduced from Li Ling, Zhongguo fangshu kao 中國方術考 (Beijing: Renmin Zhongguo, 1993), 170, figure 47; estimated size of the original diagram c. 40 × 40.

Figure 2c The so-called Liuren 六壬 type of the divining or cosmic board or “cosmograph” from the tomb of Marquis of Ruyin 汝陰侯 closed in 165 b.c.e, Shuanggudui 雙古堆, Fuyang 阜陽. Redrawing with cross-section below, laquered wood, bottom plate: 13.5 cm, upper disc diameter: 9.5 cm. Reproduced from Yin Difei 陰滌非, “Xi-Han Ruyin hou mu chutu de zhanpan he tianwe yiqi” 西漢汝陰候墓出土的占盤和天文儀器, Kaogu 1978.5, 340, figure 1.

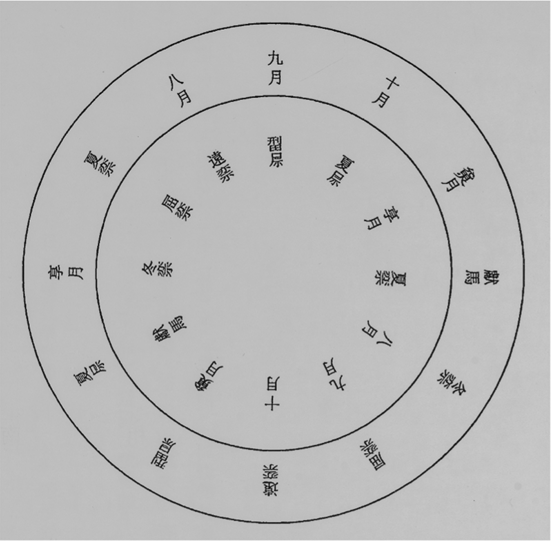

Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1 was accompanied by at least one text, which contains a diagram with a circular arrangement of months. The diagram is considerably damaged, but its colors and shape can still be ascertained from the surviving pieces—two concentric circles, both delineated in black and red, each with regular arrangements of the twelve months, see in Figure 2d (extant state) and Figure 2e (reconstruction).Footnote 41 The circular diagram has affinity with the “cosmograph's” heavenly disc and with the device composed of two discs conventionally referred to as a “lodge dial” found together with the Liuren “cosmograph” (see Figure 2f).Footnote 42

Figure 2d Diagram with two circular arrangements of the twelve months, extant state. Delineated in red and black, reproduced from Li Ling, Zidanku boshu 子彈庫帛書 (Beijing: Wenwu, 2017), 79, figure 1.

Figure 2e (middle) Diagram with two circular arrangements of the twelve months, reconstruction. Reproduced from Li Ling, Zidanku boshu 子彈庫帛書 (Beijing: Wenwu, 2017), 79, figure 2.

Figure 2f (right) The “lodge dial” device from the tomb of Marquis of Ruyin 汝陰侯 closed in 165 b.c.e, Shuanggudui 雙古堆, Fuyang 阜陽. Redrawing with cross-section below, laquered wood, bottom disc diameter: 25,5 cm, upper disc diameter: 23 cm; reproduced from Anhui sheng wenwu gongzuodui 安徽省文物工作隊, “Fuyang Shuanggudui Xi-Han Ruyin hou mu fajue jianbao” 阜陽雙古堆西漢汝陰侯墓發掘簡報, Wenwu 1978, no.8, 19, figure 8. For a slightly different redrawing, see Yin Difei 陰滌非, “Xi-Han Ruyin hou mu chutu de zhanpan he tianwe yiqi” 西漢汝陰候墓出土的占盤和天文儀器, Kaogu 1978, no.5, 342, figure 3.

The circular diagram in Chu Silk Manuscript no.2, which has become available to the scholarly community only recently, offers an important argument in favor of typological parallels of Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1 with a “cosmograph,” a divination device made up of a square plate representing the earth surmounted by a round heavenly one. The two manuscripts constitute a pair, as both convey schematic arrangements of the twelve months: their arrangement according to the square twelve-to-four pattern in Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1 was complemented by their circular arrangement in Chu Silk Manuscript no.2. The two manuscripts are therefore related, as with the earthly and the heavenly plates of a “cosmograph.”

The importance of Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1 for understanding the system of twelve gao in the Rong Cheng shi is not limited to structural parallels between the arrangement of the twelve monthly divinities in the former and the deployment of gao in the latter. Their pictorial content—symbolizing months by their divinities—points to a highly important role of divinities in the early Chinese conception of space, coordinated with the yearly cycle of seasons and months.Footnote 43 Yet this text, as well as being a “cosmograph,” provides a diagram or device imbued with some intrinsic techniques for process-oriented use—rotation—though they do not describe the process proper. Indeed, the process of managing this space–time, accomplished through sacrifices to divinities in charge of units of the spatio-temporal division, perfectly qualifies Emperor Shun's “tour of inspection” xun shou 巡狩, as described in a transmitted source roughly contemporary with the Rong Cheng shi, the “Shun dian” 舜典 chapter of the Shang shu 尚書 (Karlgren, “Yao dian 2” 堯典續; all in text references to Karlgren are to Karlgren, trans., “The Book of Documents,” Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 22 (1950)).Footnote 44 This description is a case of verbal mapping devoid of graphical illustrations, as is the description of the twelve gao. The juxtaposition of such verbal schemes or relevant texts with authentic visual aids, for some reason often missing in previous scholarly approaches, allows one to establish the missing links between scheme and action that are necessary for undersanding both.

Without going into the details of the various sacrifices, the “tour of inspection” may be summarized as follows:

In the second month of the year (sui eryue 歲二月 = mid-Spring) the “tour of inspection” goes in the Eastern direction towards the Taizong 岱宗 (= Eastern Peak) for performing a series of rites;

In the fifth month (wuyue 五月 = mid-Summer) the “tour of inspection” goes in the Southern direction towards the Southen Peak for performing the same series of rites;

In the eighth month (bayue 八月 = mid-Autumn) the “tour of inspection” goes in the Western direction towards the Western Peak for performing the same series of rites;

In the eleventh month (shiyiyue 十一月 = mid-Winter) the “tour of inspection” goes in the Northern direction towards the Northern Peak for performing the same series of rites.

One can see that the “tour of inspection” is accomplished according to the twelve-to-four pattern mapped out by the Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1. The “tour of inspection” can therefore be devined as a seasonal succession of rites, performed at the corresponding cardinal directions. The “tour” starts in Spring in the East and proceeds clockwise to the South in Summer, then to the West in Autumn and finally to the North in Winter, thus accomplishing a complete yearly cycle encompassing the entire terrestrial space. The space-regulating rites are performed in the middle month of each season at the true cardinal points marked by the four Peaks (yue 岳).Footnote 45

“Performing gao” (wei gao 為俈) described in the Rong Cheng shi also starts in the East, but proceeds crosswise—first from East to the West, then from the South to the North. Temporal correspondences are not in evidence in “performing gao,” as it regulates terrestrial space through delineating its crosswise/horizontal and lengthwise/vertical axes, unrelated to the seasonal sequence. Similarly to the arrangement of the monthly divinities in the Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1, the cardinally oriented threesomes of gao does not put any special emphasis on the central gao among the three at each cardinal direction.

Despite these structural variations, “performing gao” and the “tour of inspection” describe actions aimed at establishing a regular framework of terrestrial space, both being typologically similar process-oriented schemes. This is a strong argument in favor of understanding wei gao as the performance of certain space-regulating ceremonies. The ceremonies may have a musical aspect, but their main goal is spatial arrangement.Footnote 46

From Mountains to Waters or Vice Versa?

An even stronger argument in favor of the primary spatial significance of the twelve gao is the similar outcome of “performing gao” and the “tour of inspection”—to establish manageable elements of terrestrial space. Shun's “tour of inspection” results in the initiation of “provinces” as units of territorial division, twelve in total, followed by the establishment of a matching number of key mountains and making rivers deeper, the latter unnumbered. The repeated emphasis on the number twelve correlates with the twelve-to-four pattern underlying the “tour of inspection”:Footnote 47

Shang shu, “Shun dian,” (Karlgren, “Yao dian 2,” § 21):

肇十有二州, 封十有二山, 濬川.

[Shun] founded the “Twelve provinces,” assigned twelve mountains [and] deepened rivers.

The outcome of Shun's “tour of inspection,” in turn, is further paraphrased in the introduction to the establishment of the “Nine Provinces” (Jiu zhou 九州, literally “Nine Isle-lands”) by his subordinate and then successor, Yu the Great 大禹, as described in the “Yu gong” 禹貢 (Yu's [system] of Tribute) chapter of the Shang shu:Footnote 48

Shang shu, “Yu gong,” (Karlgren, § 1):

禹敷土, 隨山刊木, 奠高山大川.

Yu laid out the lands; moved along the mountains [as orientation marks and]

cut down trees (or made cuts [as signs] on trees)

[in order to blaze itineraries through forested highlands],

settled the high mountains [and] the big rivers.

According to these summaries, both Shun and Yu first put in order mountains and then rivers.

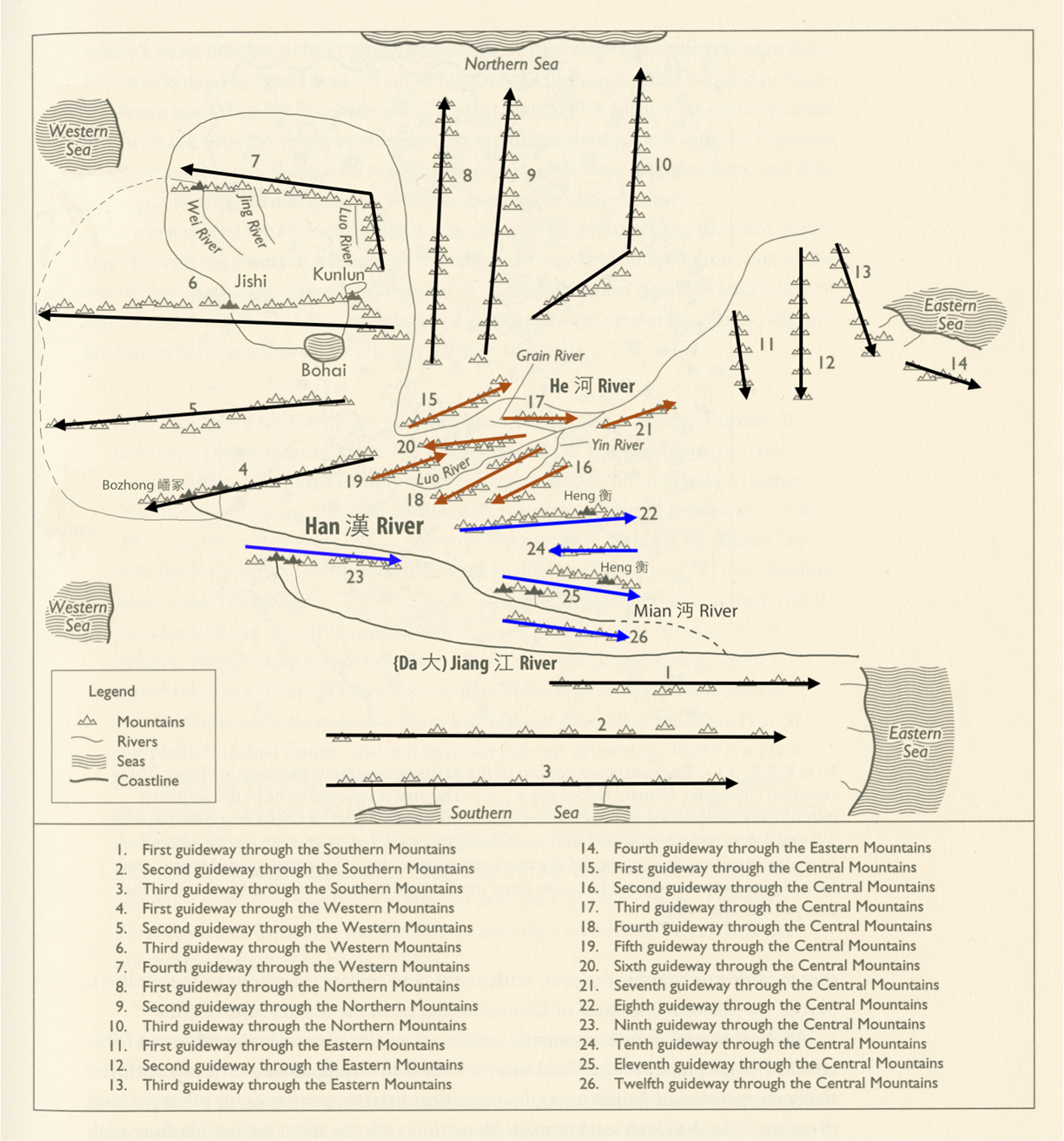

A detailed arrangement of terrestrial space in this particular sequence is developed further in the “Yu gong,” in the description of the ways of communication Yu paved through the “Nine Provinces”: first nine land itineraries marked by mountains, then nine river itineraries.Footnote 49 Another summary of Yu's regulations included into the “Yi [and Hou] Ji” 益 稷 (Karlgren, “Gao Yao mo 2”) chapter of the Shang shu contains the same phrase about mountains found in the introduction to the description of the “Nine Provinces” in the “Yu gong,” but is distinguished by paying special attention to regulating waterways:Footnote 50

Shang shu, “Yi [and Hou] Ji,” (Karlgren, “Gao Yao mo 2,” § 9):

予乘四載, 隨山刊木 …

予決九川, 距四海;

濬 畎 澮, 距 川.

I (= Yu) having mounted my four (kinds of) conveyances,

moved along the mountains [as orientation marks and]

cut down trees (or made cuts [as signs] on trees)

[in order to blaze itineraries through forested highlands] …

I (= Yu) released the flows of the nine [main] rivers and

led [them] into the seas of the four [cardinal directions],

deepened field-drains and [drainage] ducts and led [them] into the [main] rivers.

In contrast to the simple “deepening” of rivers by Shun and by Yu in the introduction to the “Nine Provinces,” the passage from the “Yi [and Hou] Ji” (“Gao Yao mo 2”) describes his arranging waterways into a two-level system of interconnected waterways for draining the excess waters of the Flood—the higher level of the “nine [main] rivers” jiu chuan 九川, which empty their waters into the seas of the four cardinal directions, and the lower level of “field-drains and [drainage] ducts” quan kuai 畎澮, which drain into the main rivers.Footnote 51 Yet, despite this focus on waterways, arranging space still starts from mountains.

A more elaborate and structurally perfect version of a successive drainage system of six levels is featured in the “Shi shui” 釋水 (Explaining Waterways), chapter 12 of the Erya 爾雅 dictionary (c. second century b.c.e.).Footnote 52 The waterways are also listed from large to small, as follows: chuan 川 [main] rivers ← xi 谿 creeks ← gu 谷gu [river] valleys ← gou 溝 [drainage] ditches ← kuai 澮 [drainage] ducts ← du 瀆 [drainage] trenches:Footnote 53

Waterways which pour into the [main] rivers are called creeks;

those which pour into creeks are called [river] valleys;

those which pour into [river] valleys are called [drainage] ditches;

those which pour into [drainage] ditches are called [drainage] ducts,

those which pour into [drainage] ducts are called [drainage] trenches.

While at first sight the richness of the vocabulary for types of waterways in the Erya is impressive, a closer look reveals that the vocabulary for mountains in this dictionary is even more abundant. Entries about mountains are divided with respect to two categories—“Shi qiu” 釋丘 (Explaining Peaks, chapter 10) and “Shi shan” 釋山 (Explaining Mountains, chapter 11). These two chapters precede chapter 12 on waterways, thus again respecting the sequence from mountains to waters. Finally, the sequence from mountains to waters determines the structure of the most comprehensive early Chinese description of the “natural” world—that of the Shanhai jing 山海經 (Itineraries of Mountains and Seas, compiled about the first century b.c.e.), composed of the “Shan jing” 山經 (Itineraries of Mountains) and the “Hai jing” 海經 (Itineraries of Seas). In addition, as in the case of the Erya, it is characterized by the quantitative prevalence of mountains over waters. Firstly, the “mountains” section is about twice as large as the “seas” section. Secondly, the itineraries of the “Shan jing,” a detailed version of Yu's land itineraries, are delineated from mountain to mountain. Rivers here are secondary landmarks, subordinated to mountains. They are registered only in cases where they have their source in mountains, and they are greatly outnumbered by mountains.Footnote 55

In sum, according to such representative texts as the Shang shu, the Erya, and the Shanhai jing, the conception of terrestrial space builds on the predominance of mountains over rivers. This point is of crucial importance for understanding the message behind the outcome of “performing the gao” in slip 31:

Rong Cheng shi, slip 31:

end of slip 31

The wording is very similar to the summaries of space regulation by Shun and Yu in the Shang shu, especially to those by Yu, which are more detailed—they include trees as attributes of mountains, and supply mountains and rivers with augmenting adjectives, though this is a difference of detail rather than substance. At the same time, in slip 31 the sequence of managing landscape features is inversed—arranging waterways precedes arranging mountains. In addition, moving across terrestrial space is effectuated not with respect to mountains—as a tour of cardinal peaks by Shun or “moving along mountains” (sui shan 隨山) by Yu, but through waterways—“traversing” and “crossing” them (wei [=yue] 躗(=越) and ji濟, respectively). This is a cardinally different view of terrestrial space, one in which the main structuring elements are waterways.Footnote 56 And, indeed, this characteristic perfectly matches the version of the “Nine Provinces” described in the Rong Cheng shi, which primarily builds on the idea of successive drainage. Its general principle, as mentioned above, is formulated in the “Yi [and Hou] Ji” (“Gao Yao mo 2”) and the “Shi shui” through a system of abstract waterways of hierarchically different types. The “Nine Provinces” of the Rong Cheng shi apply this principle to specific waterways and describe the well-known rivers of the Yellow River and the Yangzi River basins as such a system.Footnote 57 The emphasis on waterways in slip 31 correlates with the primary role of waterways in the “Nine Provinces” in this manuscript.

Proposed Placement Of Slip 31

The above comparison of slip 31 with transmitted texts, and the correlation of arranging landscape, beginning from waters, with the drainage concept of the “Nine Provinces” allows one to conclude that it most likely refers to the group of slips that describe Shun's and Yu's activities.

In the Shang shu, which became the canonical version of the origins of history in early imperial historiography, one finds an interesting phenomenon—the spatial arrangements of Shun and Yu are characterized by a certain replication with respect to each other. The similar summaries of Shun's and Yu's management of landscape features progressing from mountains to waters provide a good example. Although Shun's “Twelve Provinces” are only briefly mentioned, and Yu's “Nine Provinces” are described in much greater detail, both follow the same principle of managing terrestrial space, where the number of “provinces” is matched by the same number of arranged features of landscape, and is, therefore, also a replication. Shun's and Yu's spatial arrangements are distinguished on a formal level, from the attribution of different numbers to the separation of certain functions. Elsewhere I have discussed that the regulation of space through communicating with spirits shen 神 in the Shang shu is an exclusive prerogative of Shun, but that in transmitted texts not included into the Confucian “canon” this distinction is not respected.Footnote 58 The reason is that, with the exception of the Shang shu and its citations, the division into “provinces” is credited only to Yu, as is the major imput into regulating space in all its aspects. In the Shang shu the merit is divided between Shun and Yu: as ruler Shun initiated and inspired spatial regulation, while Yu successfully developed on them, having started as Shun's foreman.

The transmitted version of Shun's and Yu's spatial regulations found in the Shang shu, more precisely in the “Shun dian” (“Yao dian 2”), the “Yi [and Hou] Ji” (“Gao Yao mo 2”) and the “Yu gong” chapters, underwent considerable editing in becoming the canonical version, which allowed for replication. Replication is also apparent in Yu's regulations—the very similar summaries that precede the draining of excess waters in the “Yi [and Hou] Ji” (“Gao Yao mo 2”) chapter and the description of the “Nine Provinces” in the “Yu gong” can be regarded as such. Putting aside the reasons for such replications in the Shang shu, let us strip them down to the basic structural nodes of Shun's and Yu's spatial regulations. These are as follows: Shun performs the ritual regulation of space according to a twelve-fold “cosmograph”-like pattern → summary of managed landscape features → Yu realizes practical regulation of terrestrial space through draining floodwaters and establishing the “Nine Provinces.”Footnote 59 In the Rong Cheng shi one finds a concise version of these three nodes: a cardinally oriented scheme of performing twelve gao followed by a summary of managed landscape features in slip 31, and establishing the “Nine Provinces” in the drainage process in slips 24–27. If we take the canonical version of Shun's and Yu's regulations as a basis for comparison, slip 31 most likely refers to Shun's regulations and should precede the description of the “Nine Provinces.”

The description of the “Nine Provinces” in the Rong Cheng shi is the core of a definitive group of slips (23+15+/=24–30), nine slips in total, or eight if one considers slips 24 and 15 as pieces of the same slip, the sequence of which is not in doubt. Many scholars now consider slips 16–22 as belonging to this group, and place them immediately after slip 30. I suggest that a possible placement of slip 31 could be before slip 23.Footnote 60 The beginning of this slip is broken off, but the surviving piece is the second and the final reference to the general state of the landscape in the manuscript, this time in its negative state: after three years of Shun's rulership the landscape features became unmanageable and required Yu's appointment as a foreman:

Rong Cheng shi, slip 23:

… 舜聽政三年,

山𱀬 (=陵)不  (=凥= 處),

(=凥= 處),

水𰜉 (=潦)不湝(?),

乃立禹以為司工.

Shun administered the government for three years.

[During this time] mountains and hills were uninhabitable,

waterways and rainwaters did not flow,

[Shun] then established Yu as the Master of Public Works.

This description of terrestrial space as being in disorder follows the common sequence from mountains to waters, because in this way it prioritizes the main problem—the “uninhabitability” (bu chu 不處) of the land. Establishing the “Nine Provinces” in the Rong Cheng shi solves this problem, as “provinces” are conceived of as pieces of land which have become “suitable for inhabiting, habitable” (ke chu 可處) due to Yu's regulations of waterways.Footnote 61 The description of the disordered landscape in slip 23 alludes to the image of the Flood in the Shang shu—inundated mountains and hills:

Shang shu, “Yao dian,” (Karlgren, § 11), and “Yi [and Hou] Ji” (Karlgren “Gao Yao mo 2,” § 9):

懷山襄陵

[The waters of the Flood] encircled mountains and rose above the hills.

In addition, the occurrence in the “Yi [and Hou] Ji,” (Karlgren, “Gao Yao mo 2”) is followed by the phrase xia min hun dian 下民昏墊, which can be understood as “people [dwelling] below [live] in semi-darkness and make pillar constructions,” implying a difficulty of habitation.Footnote 62 The landscape becoming unmanageable after a certain period of time, as stated in slip 23, implies that it was manageable before, and from this point of view the proposed sequence of slips 31 and 23 fits. According to the proposed sequence of slips, the narrative on the regulation of terrestrial space matches the general logic of its development in the Shang shu: Shun made initial, but insufficient arrangements, and Yu completed them.

Apart from the summaries on the state of terrestrial space in slips 31 and 23, mountains are mentioned in the Rong Cheng shi only once more, in an enumeration of types of land suitable for habitation—highlands (mountains and hills) and lowlands (ping xi 平隰—plains and marshes):

Rong Cheng shi, slip 18:

禹乃因山陵平隰之可邦邑

[end of slip 18; beginning of slip 19:]

者而繁實之.

Yu then, having [established places] suitable for polities and settlements,

according to [the configuration of] mountains and hills, plains and marsches,

lavishly filled them [with population].Footnote 63

The Correlation of Mountains and Waterways in the Rong Cheng Shi and the Chu Silk Manuscript No. 1

References to mountains in this manuscript are not only quite rare—three in total—but in all these cases they refer to generic mountains.Footnote 64 In contrast to mountains, not only are references to waterways in the Rong Cheng shi numerous and diverse, but the majority are to specific rivers, lakes, and marshes.Footnote 65

Now the question is whether this emphasis on waterways in the Rong Cheng shi is only due to the central role of drainage in the conception of terrestrial space in this manuscript, or whether it may be considered generally characteristic of Chu texts. To this end, let us turn to the Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1, which is especially representative for its focus on cosmography. The Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1 always respects the sequence from mountains to waters. The traversable nature both of mountains and rivers, is, however, expressed by a term, the literal meaning of which is to “pass through rivers” (she 涉), similar to the terms for traversability in slip 31 of the Rong Cheng shi. In addition, the Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1 is distinguished by a rich diversity of waterway types, the passage below being an example of all three characteristics:

Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1, inner short text, column 3, characters 24–31:

… 以涉山陵瀧泔凼澫

… in order to pass through mountains [and] hills, fast waters, dirty waters, reservoirs(?), 10,000 rivulets(?)Footnote 66

At the same time, in the Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1, mountains are more prevalent than in the Rong Cheng shi. Mountains paired with hills are mentioned in this manuscript three times independent of waterways.Footnote 67 One of these occurrences is of special interest, as it is an attribute of the “Nine Provinces” similar to the pattern found in the “Yu gong”:Footnote 68

Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1, inner short text, column 5, characters 3–10:

Two more references to mountains are found in summaries of the main landscape features, where mountains appear first, but waterways are diverse and in a hierarchy:

Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1, inner short text, column 3, characters 11–14:

Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1, inner long text column 11, characters 15–18:

In sum, both the Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1 and the Rong Cheng shi pay considerable attention to waterways. In the former it is manifest through outstandingly diverse terminology for waters. In the Rong Cheng shi there is a quantitative and qualitative predominance of waters over mountains. Though the evidence of these two Chu manuscripts may not be conclusive, they are still representative enough to suggest that the emphasis on waters may be a manifestation of a Chu flavor in conceptualizing terrestrial space. Concepts of space are necessarily influenced by the nature of the territory where they are produced. In both manuscripts the traversability of territory is designated by terms for passing through waterways. This can only result from the practice of moving through territories with an abundance of waterways, which is, indeed, the case in the middle and lower parts of the Yangzi River basin. If the hypothesis that a pronounced emphasis on waterways may be characteristic of descriptions of terrestrial space of Chu provenance needs further confirmation, it is undeniable that in the Rong Cheng shi waterways constitute the main structural elements of the conception of space.

PART II: DRAWING A DEMARCATION LINE ALONG THE HAN RIVER: COSMOGRAPHIC IMPLICATION

This evidence for the predominance of waters in the conception of terrestrial space in the Rong Cheng shi provides the missing context for understanding the conclusion to the description of the “Nine Provinces” in the manuscript, which by definition points to the main outcome of Yu's regulations:

Rong Cheng shi, slips 27–28:

禹乃

從𤅩(=灘=漢)以南為名浴(=谷)五百,

從 [end of slip 27; beginning of slip 28:]

𤅩(=灘=漢)以北為名浴(=谷)五百.

天下之民  (=居) 奠.

(=居) 奠.

Yu then

to the South from the Han [River] created 500 named river valleys,

to the North from the Han [River] created 500 named river valleys.

The dwelling places of people through the Under-Heavens [thus] became settled.

This passage, in effect, concisely formulates the general premises of conceptualizing terrestrial space in the Rong Cheng shi. Firstly, waterways are explicitely recognized here as the main structural elements of the mapping of terrestrial space. Secondly, the orderly arrangement of waterways further assures the stability of “dwelling places” (ju 居) or inhabitable land in the Under-Heavens. As mentioned above, the establishment of the “Nine Provinces” is conceived of as a conversion of “uninhabitable” (bu chu) landscape into “suitable for inhabiting” (ke chu) pieces of land that emerged when the waters were drained.Footnote 72 The stability of “dwelling places” through the entire Under-Heavens is, therefore, the ultimate goal of the “Nine Provinces” in the Rong Cheng shi.

Yet, this does not solve the main puzzle—the unusual division of the mapped terrestrial space into South and North along the Han River. It is even more puzzling that the Han River is not mentioned in the description proper of the “Nine Provinces” or elsewhere in the Rong Cheng shi. This curious reference to the Han River has been noticed only in passing in previous scholarship. The first explorer of the Rong Cheng shi manuscript, Li Ling, simply mentions the noteworthiness of delineating a borderline between the North and the South along the Han River.Footnote 73 Pines is aware that the phrase “hints at the Han River being of central importance for the authors, which would fit nicely with a Chu location,” but still believes that “the association with Chu remains very meagre” in the manuscript.

I now argue that the demarcation line along the Han River between the South and the North is the crucial point in the description of the “Nine Provinces” in the Rong Cheng shi, if not the point of it. In order to clarify all the implications of the demarcation line along the Han River, it is necessary to determine how the position of this river was conceived of in early terrestrial descriptions and traditional historical cartography, beginning from the system of the “Nine Provinces.”

“Provinces” Described in the Rong Cheng Shi: The Method of Locating by Landmarks

The new version of the “Nine Provinces” discovered in the Rong Cheng shi attracted much attention from Chinese specialists on manuscripts and concepts of space.Footnote 74 The unusual names of many of the “provinces” in the Rong Cheng shi and the unusual way of describing them in pairs gave an initial impression that a Chu version of the “Nine Provinces” has been discovered.Footnote 75 However, multiple investigations of it showed that, apart from these, the Rong Cheng shi version of the “Nine Provinces” does not contain anything new in the description of the “provinces” with respect to transmitted texts. On the contrary, it has multiple parallels with a broad range of transmitted texts, in particular with descriptions of the “Nine Provinces.” My own input into these investigations was to evaluate the new version of the “Nine Provinces” with respect to their transmitted accounts and other references to them in terms of conceptualizing space. In this respect, this approach reveals the outstandingly eclectic character of the manuscript version of the “Nine Provinces.” It combines spatial concepts related to the “Nine Provinces” that became distinct in transmitted texts, and, therefore, throws new light on the group of transmitted sources concerned and their filiation. At the same time, the “Nine Provinces” in the Rong Cheng shi appear to have close affinity with the mainstream representation of the “Nine Provinces,” according to the “Yu gong” and its four derivations—the “Youshi lan” 有始覽 (Observations on the Beginnings) chapter of the Lüshi chunqiu, the “Shi di” 釋地 (Elucidations on the Earth) chapter of the Erya and the “Zhifang shi” 職方氏 (Officer in Charge of the Cardinal Directions) chapter of the Zhou li 周禮 (Zhou Rituals, compiled by the middle of the second century b.c.e.).Footnote 76 My method of determining their affinity was to explore the names and types of landmarks that occur in the Rong Cheng shi version of the “Nine Provinces” in comparison to their transmitted descriptions, combining a philological approach with their analysis as markers of “positions” in a conception of space.Footnote 77

First, I compared placenames and the context of their occurrence in the Rong Cheng shi version of the “Nine Provinces” with their transmitted descriptions and other relevant texts. As already mentioned, all landmarks found in the Rong Cheng shi description of the “Nine Provinces” are waterways, and all but one river, Lou 蔞, in the most northern “province,” overlap with rivers, lakes, and marshes found in descriptions of the “Nine Provinces” of the “Yu gong” group of accounts.Footnote 78 In many cases the context of their occurrence shares the same wording with the transmitted descriptions.

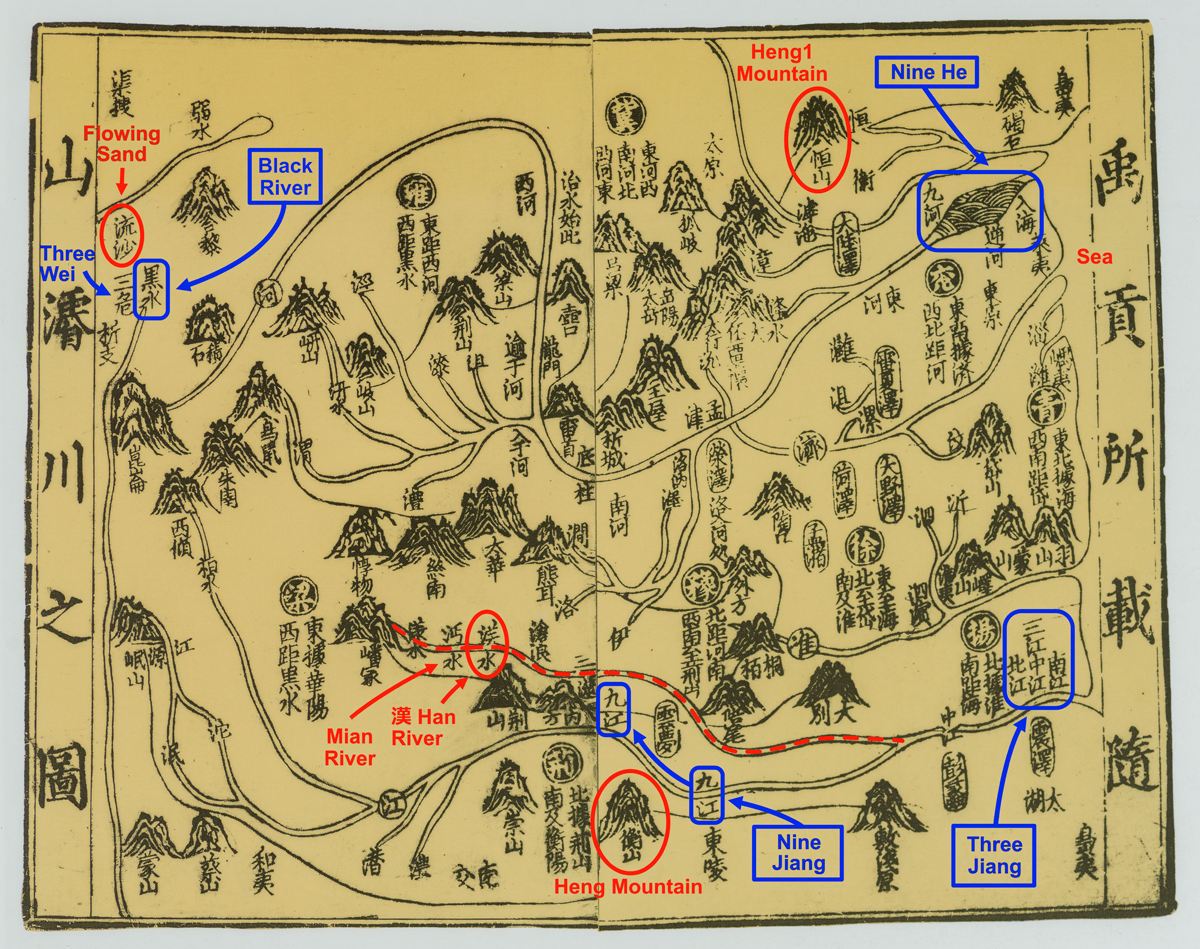

In addition to the usual philological analysis, I explored depictions of waterways found in the Rong Cheng shi description of the “Nine Provinces” in maps showing the “Yu gong” topography. The earliest extant maps of the “Nine Provinces” are known from the Southern Song dynasty.Footnote 79 These maps appeared as a form of commentary on the “Yu gong,” and continued to be produced and re-produced from then onwards. Formally referring to the “Yu gong” and mostly based on its topography, these maps sometimes include topographical data from other sources.Footnote 80 I argue that early Chinese descriptions of terrestrial space cannot be adequately comprehended without taking into consideration traditional Chinese cartography, which continues the same tradition of conceiving of space, and especially not without the historical maps drawn as visual elucidations on early texts. Modern Western maps, often used by default for illustrating early Chinese texts in contemporary studies, are aimed at a topographically accurate and complete representation of the terrestrial surface. Song maps of the “Yu gong” topography are of a radically different—relational, positional, or diagrammatic—category of maps, typologically similar to relational tree diagrams.Footnote 81 The Song dynasty maps build on a limited selection of landmarks and aim to show their arrangement with respect to each other, which serves to convey spatial ideas without much concern for topographical accuracy. The majority of landmarks listed in the “Yu gong” and then visualized in maps are inspired by the real topography of the Yellow and the Yangzi river basins; but once selected, these landmarks immediately become markers of relative positions.Footnote 82 Positions in maps can be shifted quite considerably with respect to the real locations of landmarks for the sake of the desired spatial arrangements. In addition, landmarks borrowed from real topography are often transformed and supplemented by landmarks that actually do not exist.Footnote 83

While using waterways found in the description of the “Nine Provinces” in the Rong Cheng shi as a means by which to approximate locations of each “province,” I combined the application of the Western maps and the “Yu gong” topography maps.Footnote 84 This is not simply circumscribing geographical areas. This method shows the “provinces” of the Rong Cheng shi and their landmarks as elements of relational mapping, and compares them with the relational topography of the “Yu gong.” Apart from sharing the same landmarks as markers of the same territorial core with the “Yu gong” group of the “Nine Provinces,” the Rong Cheng shi set of “provinces” manifests a typological affinity with them in terms of the relational arrangements of landmarks.Footnote 85

Following the text of the early Chinese written sources and the images of traditional “Yu gong” cartography, I refer to the rivers as they appear in these texts and maps, for instance, He and Jiang not the Yellow River and the Yangzi River. This is because these latter names, especially in the case of the Yangzi, do not always completely correspond to the configuration of landmarks listed in the early sources. In addition, Yangzi is a toponym current in the Western cartography, its Chinese equivalent is a derivate of Jiang—Changjiang 長江 (Long Jiang). This approach allows one to understand what precisely is meant in the references to these landmarks in early texts, and is one of the reasons why I provide, in the majority of cases, my own translations of textual passages.

The Limits of the “Nine Provinces”: The Transgressible and Non-Transgressible

The investigation by landmarks of the “Nine Provinces” described in the Rong Cheng shi summarized above was primarily aimed at approximating the areas of single “provinces.” Drawing a demarcation line between South and North along the Han River raises the issue of the general area of the territory thus divided and its limits. The limits of the area covered by different sets of the “Nine Provinces” have not yet been systematically discussed in scholarly literature. By the limits here I mean landmarks, which are conceived of as bordermarkers. I shall investigate them applying the same method, which combines philological analysis with the examination of their positions in maps of the “Yu gong” topography. The limits of the “Nine Provinces” described in the “Yu gong” are defined in the conclusion to their description:Footnote 86

Shang shu, “Yu gong” (Karlgren, § 38):

The East and West are delimited by “fluid” boundaries, the Sea and the Flowing Sand, inspired by the East China Sea and the Gobi-Taklamakan desert zone, respectively.Footnote 87 The zone of sand in the Chinese view of space was designated by “watery” characters—the character “sand” (sha 沙) has the “water” radical and and its adjective “flowing” (liu 流) is usually applied to rivers. In this way the sand zone in the West made a “fluid” counterpart to the Sea in the East. The indefinite northern and southern limits in the “Yu gong” are further determined in one of the latest texts related to the “Yu gong” group, the “Wang zhi” 王制 chapter (c. second century b.c.e.) of the Li ji. It does not feature any specific set of “provinces,” but instead provides a list of measurements, which allow one to assemble an ideal 3 × 3 square grid framework underlying the “Nine Provinces.” The Eastern boundary here appears with the adjective “Eastern”—the Eastern Sea, making it a better pair to the Flowing Sand, and the limits in the South and North are marked by mountains, Heng 衡 and Heng1 恆, respectively. Thus, there is the symmetry of the fluid boundaries in the East and West, and the mountains in the South and North:Footnote 88

Li ji, “Wang zhi” chapter:

Heng and Heng1 mountains are mentioned in the “Yu gong,” but not yet as markers of the cardinal points.Footnote 89 It is also noteworthy that in the “Yu gong” the definition of limits is centrifugal—the territories inside extend as far as the defined limits, while in the “Wang zhi” it is centripetal—the territories do not exceed them. The Heng and Heng1 mountains are now identified with real mountains having these names in southern Hunan and northern Shanxi, respectively. One should keep in mind, however, that their actual identifications may have been determined later, and that these mountains may have had alternative identifications, as is the case with many Chinese placenames. For this reason it is especially important to examine depictions of landmarks under these names in traditional Chinese maps, as they show their relative locations.Footnote 90

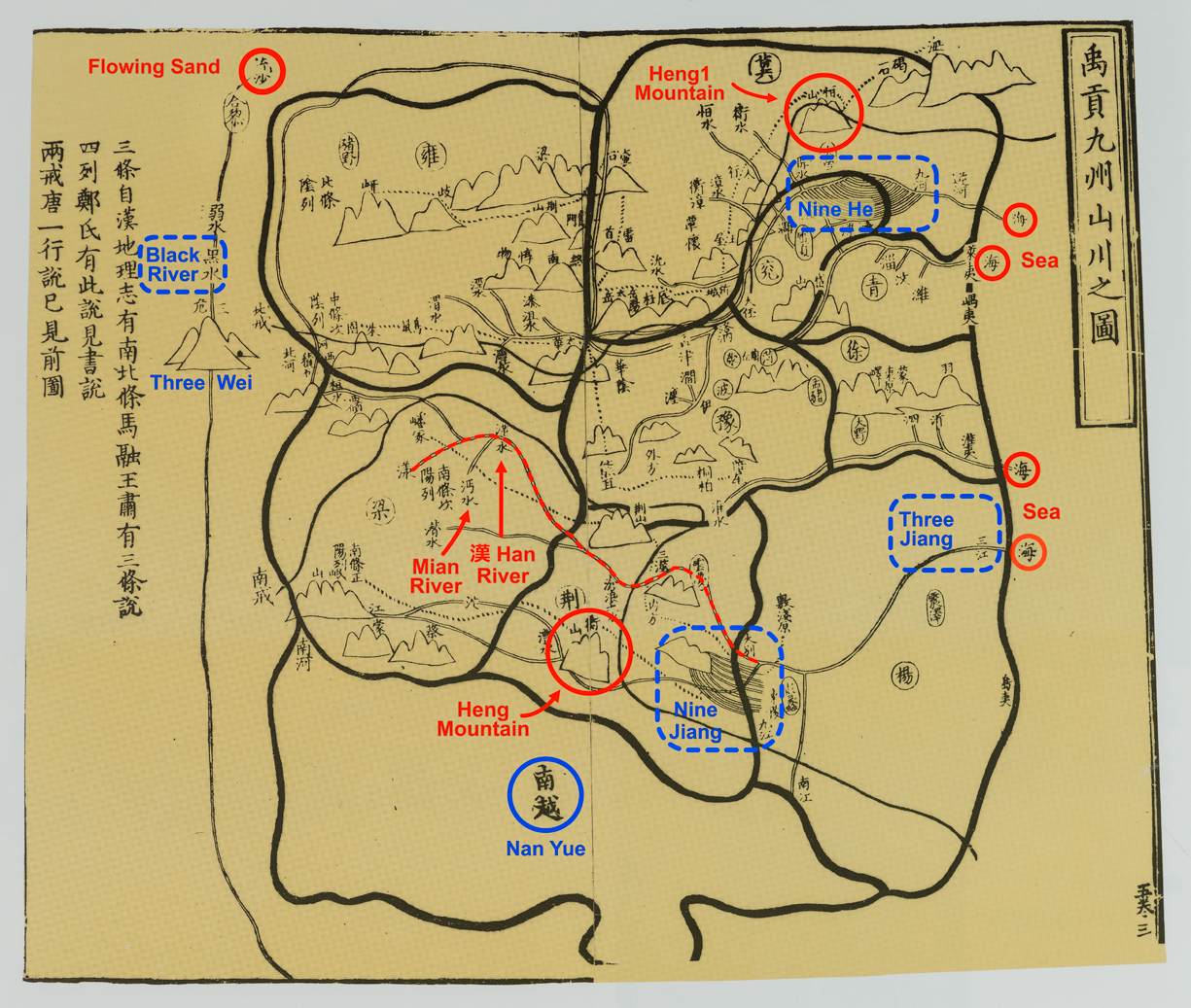

One of the earliest and the most clearly drawn example of the “Yu gong” maps is the “Map of moving along mountains and deepening rivers, as registered in the Yu gong” (Yugong suo zai suishan junchuan zhi tu 禹貢所載隨山濬川之圖) from the Collected Commentaries on the Book of Documents (Shu jizhuan 書集傳) completed in 1209 by Cai Shen 蔡沈, also known as Cai Jiufeng 蔡九峰 (1167–1230), see Map 1a. The Eastern Sea and the Flowing Sand, and Heng and Heng1 Mountains are prominently depicted at the corresponding cardinal sides of the map, thus showing how these landmarks demarcate the area, as described in the “Nine Provinces” of the “Yu gong.”

Map 1a “Map of moving along mountains and deepening rivers, as registered in Yu gong” (Yugong suo zai suishan junchuan zhi tu 禹貢所載隨山濬川之圖), in Collected Commentaries on the Book of Documents (Shu jizhuan 書集傳) completed in 1209 by Cai Shen 蔡沈 / Cai Jiufeng 蔡九峰 (1167–1230). National Library of China (Beijing) 中國國家圖書館. Reproduced from: Yan Ping et al., China in Ancient and Modern Maps (London: Sotheby's Publications, Philip Wilson Publishers, 1998), 65. Printed on two pages in a block-printed book, precise dimensions unavailable.

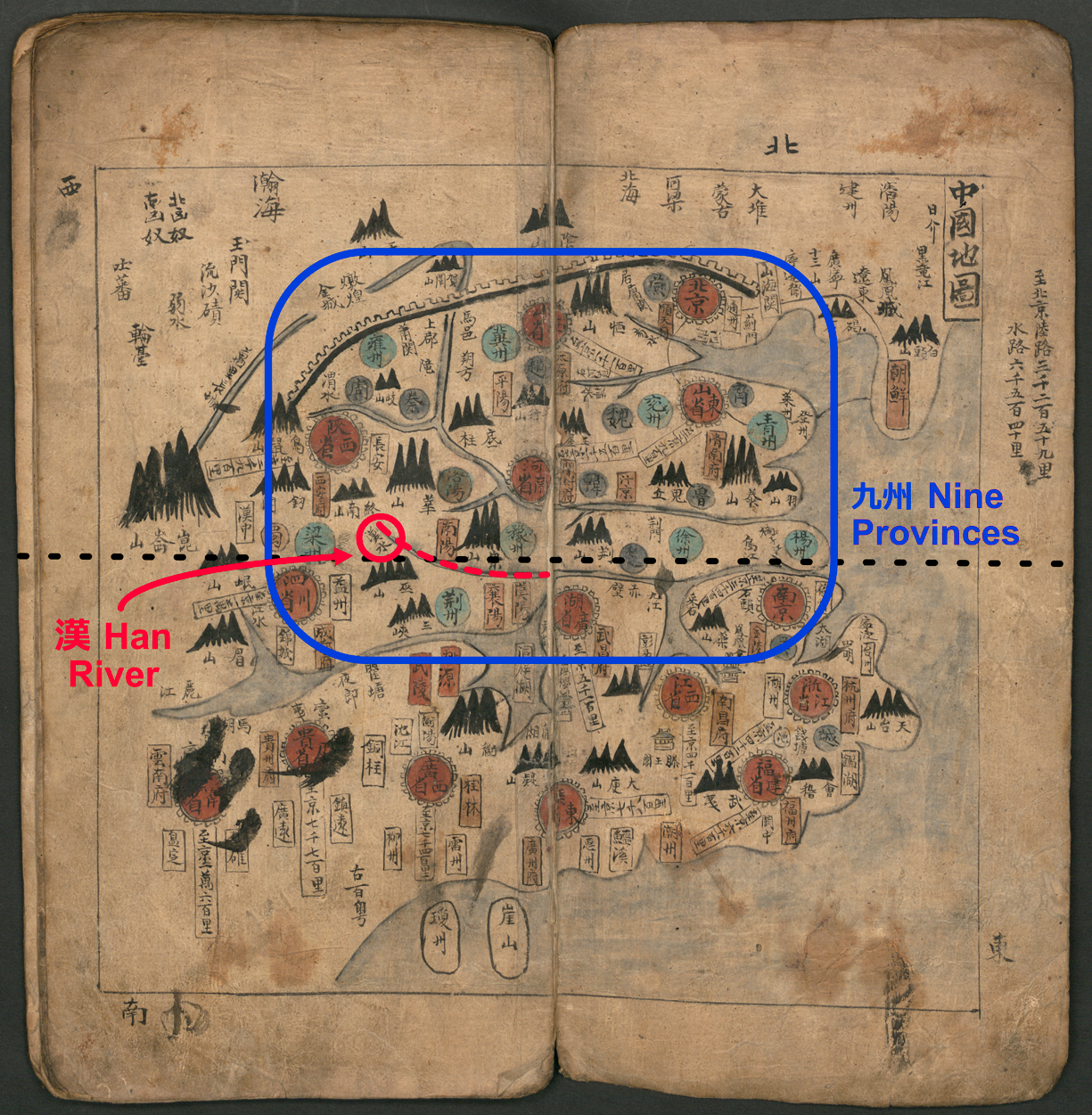

The key difference between the historical “Yu gong”-type maps and maps showing administrative divisions of the Chinese Empire consists in their southern limits. Those of the “Yu gong” topography do not include territories to the South of Heng Mountain, as is the case of the map by Cai Shen. Contemporary maps of the Song Empire, on the other hand, extend to the sea in the South. Especially instructive here are maps that combine both historical and contemporary topography and administrative divisions. One such example was drawn by Cai Shen for the Collected Commentaries on the Book of Documents and, according to its title, aimed at making a comparison between the “Yu gong” topography and the Song imperial realm—“Map of the Nine Provinces of the Yu gong of the contemporary provinces and commanderies” (Yugong Jiu zhou ji jin zhoujun zhi tu 禹貢九州及今州郡之圖), see Map 1b. Such maps include southern territories between Heng Mountain and the sea in the South, but historical place-names are only given for landmarks to the North of Heng Mountain and are distinguished from contemporary place-names through using different legends.Footnote 91 This way of the superimposition of historical cartography on the contemporary imperial realm became especially current in Ming cartography and after, see for instance Maps 3 and 5.

Map 1b “Map of the Nine Provinces of the Yu gong of the contemporary provinces and commanderies” (Yugong Jiu zhou ji jin zhoujun zhi tu 禹貢九州及今州郡之圖), in Collected Commentaries on the Book of Documents (Shu jizhuan 書集傳) completed in 1209 by Cai Shen 蔡沈/Cai Jiufeng 蔡九峰 (1167–1230). National Library of China (Beijing) 中國國家圖書. Reproduced from: Yan Ping et al., China in Ancient and Modern Maps (London: Sotheby's Publications, Philip Wilson Publishers, 1998), 64. Names of the “Nine Provinces” are marked by circles. Printed on two pages in a block-printed book, precise dimensions unavailable.

In terms of modern physical geography, the territory covered by the “Nine Provinces” is delimited in the South by the arc of the Nanling and Wuyi mountain ranges. These mountains are difficult to cross and thus formed a natural obstacle to going South.Footnote 92 The same applies to depictions of the eastern and the western borders of the “Nine Provinces” in Chinese cartography. These borders are also inspired by serious natural obstacles to territorial extension—the desert region in the northwest and the sea in the East. Maps of the “Nine Provinces” keep strictly to these borders, and in this respect differ from some maps of the contemporary Chinese Empire. Many contemporary maps include the Western Region, and the sea in the East contains the names of insular neighbours. In the “Yu gong” topography maps, the sea is reduced to a thin blank margin, and the Flowing Sand does not have a special cartographic image, being marked only by its name. It is also noteworthy that the Flowing Sand is a natural western limit only of the Yellow River basin, while the Yangzi River basin is delimited by mountaneous areas, though it was the view of the Yellow River Basin that determined the idea of the western boundary of the “Nine Provinces.” The “Yu gong” maps adhere to topographical reality and place the Flowing Sand in the northwest.

The situation with the northern boundary is different from all the other cardinal limits of the “Nine Provinces,” which are distinguished by the difficult nature of their transgressibility. Some of the “Yu gong” topography maps include landmarks mentioned in the “provinces,” which are missing in the initial “Yu gong” set. All these supplementary landmarks are small rivers draining into the Bohai Sea. In the maps in question, this region occupies the northeastern corner.Footnote 93 One can see from a physical map of China that the Bohai Sea is, indeed, surrounded by lowlands covered by a dense river network, which facilitated territorial expansion, and at the same time is delimited to the West by mountain ranges, thus chanelling expansion in a northeasterly direction (see Map 2a). It is also noteworthy that Heng1 Mountain located almost on the same longitude with Heng Mountain (113°44′08″E and 112°41′05″E, respectively) in the “Yu gong” maps, is considerably shifted to the northeast. This shift most likely reflects the impluse towards the northwest.Footnote 94

In sum, the “Nine Provinces” is a conception of space reflecting the reduced capacity for territorial expansion, with the exception of the northeastern corridor, as one can grasp from a scheme of the topographical areas of China, see Map 2b, The only flaw of this useful scheme is the lack of a special symbol for the desert area, encompassing the southern part of the Inner Mongolian Plateau and the Tarim basin. This is an interesting echo of the original absence of a special cartographic symbol for desert in Chinese cartography.

Map 2a Physical map of China.

Map 2b Topographical areas of China.

The “Nine Provinces” sets of the “Yu gong” group differ in one or two positions; altogether they include twelve names of “provinces.”Footnote 95 These dozen “provinces” are depicted in the “Map of demarcation between the Nine Provinces and the Twelve Provinces of Tang (= Yao 堯) and Yu1 (=Shun 舜)” (Tang Yu Jiu zhou shier zhou fenjie tu 唐虞九州十二州分界圖) from the Yue shi yue1 shu 閱史約書 (Reviewing history, weighing books) by Wang Guanglu 王光魯 in 5 juan, published in 1643, see Map 3.Footnote 96 In this map, the northeastern extension is distinguished by means of special cartographic symbols:

• in contrast with all the other sides of the mapped territory, the northeast is not circumscribed by a continuous boundary, thus staying open for further extension;

• “provinces” missing in the “Yu gong” set are delineated from each other by double borderlines.

From the point of view of its landmarks, the Rong Cheng shi set of the “Nine Provinces” follows the same tendency: it is characterized by a surprisingly large extension to the northeast, and contrary to expectations, does not include any specifically southern landmarks.Footnote 97

Map 3 “Map of demarcation between the Nine Provinces and the Twelve Provinces of Tang (= Yao 堯) and Yu1 (=Shun 舜)” (Tang Yu Jiu zhou shier zhou fenjie tu —唐虞九州十二州分界圖), in Yue shi yue1 shu 閱史約書 (Reviewing history, weighing books), by Wang Guanglu 王光魯 (fl. mid seventeenth century) in 5 juan (published in 1643). National Library of China (Beijing) 中國國家圖書館. Reproduced from: Yan Ping et al., China in Ancient and Modern Maps (London: Sotheby's Publications, Philip Wilson Publishers Ltd., 1998), 155. Printed on two pages in a block-printed book, precise dimensions unavailable.

In sum, from the point of view of textual parallels between transmitted descriptions of the “Nine Provinces” and that in the Rong Cheng shi version, and the areas that both the transmitted and the Rong Cheng shi sets of “provinces” fill out by landmarks, one can find no specifically Chu spatial concepts in the Rong Cheng shi. This conclusion matches the general impression of Yuri Pines, who notes “a curious lack of any Chu-related trait in the Rong Cheng shi” and its “absence of Chu flavour.”Footnote 98 Even if one may question considering the “Nine Provinces” as a “northern” view of the core Chinese territories,Footnote 99 it is still a view that includes a modest share of the southern territories in the Yangzi River basin and an expanding predominance of the “provinces” that belong to the basin of the Yellow River and further northeast.

Totals of Landscape Features as a Means of Measuring Space

Let us now return to the division of terrestrial space into the southern and the northern clusters of waterways by the Han River, begining with the quantitative implication with respect to the “Nine Provinces.” The use of quantitative topographical summaries per se is one of the distinguishing features of early Chinese descriptions of terrestrial space, specifically, the total numbers of waterways found in several Warring States—Former Han texts. Especially interesting is the passage from the “Tianxia” 天下 (The under-heavens) chapter of the Zhuangzi 莊子 citing the philosopher Mozi 墨子 (c. 470–c. 391 b.c.e.). The passage is not found in the transmitted version of the Mozi treatise and belongs to the latest layer (Miscellaneous Chapters zapian 雜篇) of the Zhuangzi, which consists of thirty-three chapters composed from the fourth through the second century b.c.e. “Tianxia” is the last—the thirty-third—in the list of chapters and was apparently composed by Zhuangzi's followers. Yet, the concept referred to in the passage may be dated to the end of Mozi's lifetime, which overlaps with the upper chronological limit of the Zhuangzi—the early fourth century b.c.e. Translations of this passage vary considerably in interpretation.Footnote 100 The detailed description in the Rong Cheng shi of how Yu established the “Nine Provinces” through “releasing” 決 and “communicating/linking” (tong 通) waterways seems to provide the missing details for a better understanding of this passage.Footnote 101 In it the excess waters are drained through a hierarchical system of rivers—300 big rivers, 3,000 of their tributaries, and countless small rivers:

“Tianxia” chapter of the Zhuangzi citing Mozi:

墨子稱道曰:

昔禹之湮洪水,

決江河而通四夷九州也.

名川三百,

支川三千,

小者無數.

禹親自操橐耜而九雜天下之川 …

Mozi, praising [his] teaching, said:

In former times when Yu was draining off the floodwaters,Footnote 102

[he] released the Jiang and He [rivers]

and made communicate [via waterways the territories of]

the barbarians of the four [cardinal directions] and the Nine Provinces.

The [number of resulted] named rivers is 300;

The [number of their] tributary rivers is 3,000;

Small [rivers] are countless.

Yu personally himself operated the sack/basket [for collecting soil] and ploughshare

and [thus within] the Nine [Provinces] interlaced the rivers of the Under-heaven …

A more complete hierarchy of waterways is provided in the “Youshi lan” chapter of the Lüshi chunqiu.Footnote 103 Here there are 6 magistral [river] valleys, 600 main rivers, 3,000 tributaries and more than 10,000 small rivers.Footnote 104 These totals are not strictly related to Yu's ordering of terrestrial space, but are part of the “fundamental structural principles (literally: “beginnings” shi 始)” of the Universe (Heavens and Earth) listed at the beginning of this chapter. Except for the mention of the Heavens at the head of the list, all other attributes are of ordered terrestrial space:

Lüshi chunqiu, chap. 13 “Youshi lan,” § 1 “You shi” 有始:

Each of these total numbers of attributes is further elucidated by names of their constituent elements, e.g. names of each “province,” mountain etc. The “Six [Main] Rivers” include the He 河, the Chi (=Red) 赤, the Liao 遼, the Hei (=Black) 黑, the Jiang 江 and the Huai 淮 rivers, but not the Han River, which is featured so prominently in the Rong Cheng shi. The list of rivers is followed by dimensions of the earth surface “Inside the Seas” (Hainei 海內) and the totals of its waterways:

“Youshi lan” chapter of the Lüshi chunqiu:

…

何謂六川?河水,赤水,遼水,黑水,江水,淮水。

凡四海之內,東西二萬八千里,南北二萬六千里,

水道八千里,受水者亦八千里,

通谷六,

名川六百,

陸注三千,

小水萬數.Footnote 105

What is meant by the “Six [Main] Rivers”? The He River, the Red River, the Liao River, the Black River, the Huai River.

In sum, the inside the four [cardinally oriented] seas is

28000 li long from the East to the West,

26000 li long from the South to the North.

River itineraries are 800 li long; rivers receiving confluents [= big rivers] are also 800 li long.

There are 6 magistral [river] valleys,

600 named rivers,

3,000 pouring from the [high]lands,

small waterways are counted in their 10,000's.

The 6 magistral [river] valleys apparently correspond to the six main rivers, as specified above, which gives a clear “point of entrance” into the waterway system. The “Youshi lan” totals are reproduced in a simplified way in the “Dixing xun” 墬形訓 chapter of the Huainanzi 淮南子 (compiled by 139 b.c.e.), and explicitly in the context of Yu's ordering of terrestrial space. The “Dixing xun” copies much of the “Youshi lan” passage, except for the names of the “Nine Provinces” and the detailed hierarchy of waterways. It only refers to unnumbered “magistral [river] valleys” tong gu 通谷 and 600 big rivers. However, the total length of “land itineraries” lu jing 陸徑 of 3,000 li is an interpretation of the ambiguous “land(?) confluents” (lu zhu 陸注) listed in the “Youshi lan” and indirectly continues the decimal sequence of totals of waterways:Footnote 106

Huainanzi, chap. 4 “Dixing xun”:

闔四海之內,東西二萬八千里,南北二萬六千里,

水道八千里,

通谷其名川六百,

陸徑三千里.

To sum up, the inside the four [cardinally oriented] seas is

28000 li long from the East to the West,

26000 li long from the South to the North.

River itineraries are 800 li long,

As far as the magistral [river] valleys [are concerned],

its named river flows are 600,

The land itineraries are 3,000 li long.

A list of distances totals, in its turn, derived from the “Dixing xun” is found in the conclusion to the first part of the Shanhai jing, the “Shan jing” or the “Wuzang Shanjing” 五臧山經 (Five Treasuries: the Itineraries of Mountains).Footnote 107 By definition, the “Shan jing” privileges total numbers related to mountains, and develops on the lengths of itineraries by land and by rivers, but total numbers of waterways are not included:

“Shan jing,” conclusion:

禹曰:

天下名山,經五千三百七十山,六萬四千五十六里,居地也.

言其五臧,蓋其餘小山甚衆,不足記云.

天地之東西二萬八千里,南北二萬六千里,

出水之山者八千里,受水者八千里,

出銅之山四百六十七,出鐵之山三千六百九十.

Yu said: [as far as] the named mountains of the Under-heavens [are concerned],

[I] passed through and thus linked by itinerariesFootnote 108 5370 mountains,

[the established itineraries are] 64056 li [long],

[these are the dimensions of] dwelling/inhabitable land.

They are called the “Five Treasuries,”

In sum, the other smaller mountains are extremely numerous, cannot even be recorded.

Heavens and Earth are 28000 li [long] from the East to the West,

26000 li [long] from the South to the North.

Mountains being sources of rivers, [these rivers are] 800 li long,

Rivers receiving confluents (= big rivers) are 800 li long,

There are 467 mountains producing copper, 3690 mountains producing iron.

The series of passages discussed above manifest a chain of filiations from the Mozi citation in the Zhuangzi to the “Youshi lan,” then the “Dixing xun” and, finally, the conclusion to the “Shan jing,” as summarized in Table 1.Footnote 109 The most structurally complete four-level system of waterways appears in the “Youshi lan.” It is typologically similar to the drainage systems described in the “Yi [and Hou] Ji” (Karlgren, “Gao Yao mo 2,” § 9) and the “Shi shui” chapter of the Erya discussed in Part I above, with the difference that the focus is not on the drainage aspect, but on the number of different types of waterways. In the “Youshi lan” the system of waterways also becomes supplemented by dimensions of inhabitable space and total lengths of river itineraries. The “Shan jing” develops the same template, having replaced rivers by mountains. The reference to the arrangement of waterways with respect to the Han River in Rong Cheng shi is a congener, but from an apparently different branch.

Table 1 Text filiations

The common feature of all these totals is the adjective ming 名 applied to the higher types of landmarks. It is usually translated as “famous,” but I suggest that they may rather mean “important landmarks with fixed names” versus smaller landmarks of no importance. Some evidence for this suggestion is found in the Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1, where the naming of landscape features is a means for putting them in order, possibly by the Emperor Yu, who may be mentioned just before (Chu Silk Manuscript, inner short text, column 2, character 26). The character ming 名 is replaced here by its homophone ming1 命:

Chu Silk Manuscript, inner short text, column 3, characters 5–14:

山陵不斌, 乃命山川四海

Mountains and hills were not refined, then named mountains and rivers, the four seasFootnote 110

At the same time, the total numbers of waterways in the Rong Cheng shi differ in several interesting respects from those found in the Zhuangzi, Lüshi chunqiu, and Huainanzi:

1) The Rong Cheng shi provides the total of “named” (ming 名) river valleys designated by the character yu 浴, which consists of the radical “water” 水 shui and the semantic element “valley” gu 谷, the radical accentuating its relation to waterways. The same vocabulary is found in the Chu Silk Manuscript no. 1 (shanchuan, wanyu 山川澫浴 “mountains [and] rivers, 10,000 rivulets(?) [and] river valleys”).Footnote 111

2) The “named river valleys” ming yu 名浴 is a fusion of the “magistral [river] valleys” tong gu 通谷 and the “named rivers” ming chuan 名川, distinguished in the Lüshi chunqiu and the Huainanzi, as the two higher levels of waterways.

3) In contrast to the transmitted texts, in the Rong Cheng shi there is no hierarchy of waterways. Instead they are arranged into two quantitatively equal cardinally oriented parts: 500 “named river valleys” in the South and 500 “named river valleys” in the North. This spatial arrangement of the total numbers of waterways is nowhere in evidence in transmitted texts. The equality of the southern and northern parts is accentuated by the term, which appears in the phrase, which immediately follows: 天下民居奠 Tianxia min ju dian (The dwelling places of people through the Under-Heavens [thus] became settled). 奠 depicts a ritual vessel on an altar and implies something being perfectly balanced.

4) The total number of 300 “named rivers” in the Zhuangzi is doubled to 600 in the “Youshi lan,” which also adds a matching upper hierarchical level of 6 “magistral [river] valleys.”Footnote 112 The southern and northern “river valleys” in the Rong Cheng shi altogether make up a considerably larger total number of 1,000.

I believe that the numerical rise in the total numbers of landscape features conveys an idea of territorial expansion. In the case of the “Youshi lan” it may correspond to the extension of this set of the “Nine Provinces” to the northeast. The 1,000 “named river valleys” have to be seen in the context of the spatial implication of the South–North division along the Han River.

The Han River in Chinese Cosmography and Cartography

To begin with, a territorial division into two equal halves along the Han River does not match the area encompassed by the transmitted and the Rong Cheng shi sets of the “Nine Provinces.”

In transmitted descriptions of the “Nine Provinces,” the Han River is used as a boundary marker between “provinces” twice—in the “Youshi lan” and the “Shi di.” According the “Youshi lan,” the Han River together with He delimit Yu 豫 “province”:Footnote 113

Lüshi chunqiu, chap. 13 “Youshi lan,” § 1 “You shi” 有始:

河漢之閒為豫

Between the He and the Han [rivers] there is Yu [province]

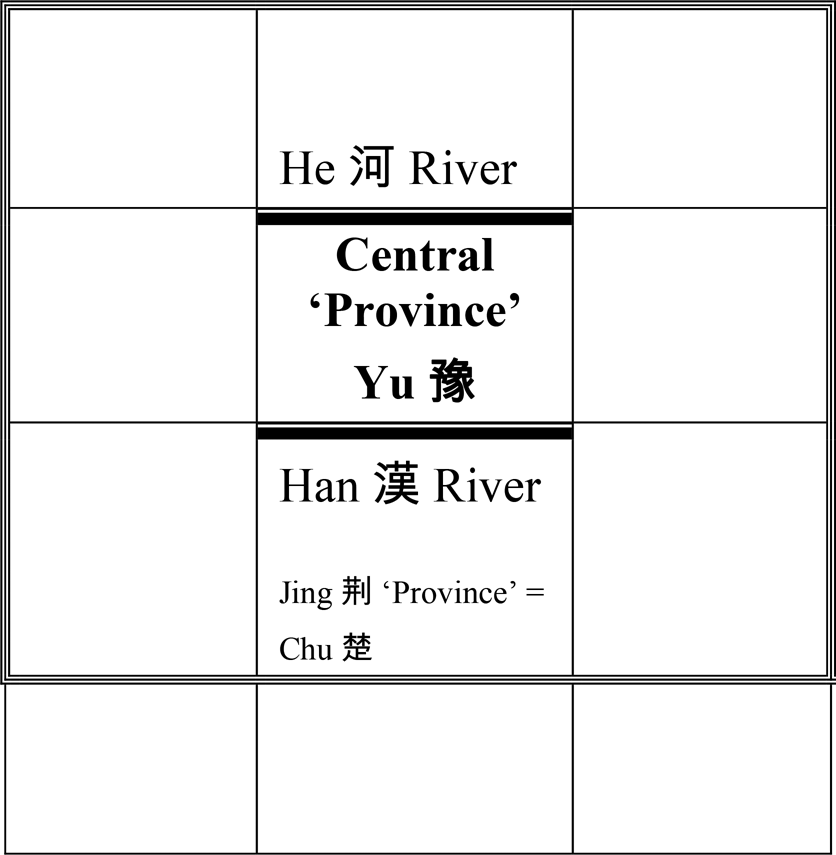

Yu “province” is found in all transmitted sets. In the Rong Cheng shi, Yu corresponds to Xu 敘 “province.”Footnote 114 Yu covers the region of Luoyang, the center of the ideal picture of the world under the Zhou dynasty. In representations of the “Nine Provinces” within the framework of the 3 × 3 grid, Yu occupies the central square.Footnote 115 The He and Han rivers, seen as boundaries of the central square of the 3 × 3 grid, divide the territory of the “Nine Provinces” into three equal thirds: the He River delimits the center from the North, and the Han River from the South (see Figure 3). In the “Shi di,” the Han River is referred to from the other side, as the northern boundary of Jing “province” (another name of the Chu Kingdom), which occupies the southern square of the grid:Footnote 116

Erya, chap. 9 “Shi di”:

漢南曰荊州

[The territory] to the South of the Han River: Jing “province.”

In the “Yu gong,” the Han River is not used as a “province” boundary, but is mentioned twice in the description of Jing “province.” If we accept that the Han River conventionally divides the mapped territory into equal northern and southern sections, then one must add another line of squares at the bottom or the South of the 3 × 3 grid.

Figure 3 Positions of Yu and Jing “provinces” within the 3 × 3 grid. Representation of the “Nine Provinces” (delimited by a triple line).

This simple scheme demonstrates the great impact of the South–North division along the Han River. It implies the extension of the “civilized world” to the South and shifts its center to the northern border of Chu. The scheme also demonstrates a 3 × 3 scheme for the “Nine Provinces,” which by definition cannot be divided into two halves by rivers as boundaries between the “provinces.” Rivers as boundaries between the squares of the 3 × 3 grid are described in the “Wang zhi,” where they complement the cardinal limits of the “Nine Provinces”:Footnote 117

Li ji, “Wang zhi” chapter:

North → South

From Heng Mountain to the Southern He River, it is as close as 1,000 li;

From the Southern He to the Jiang River, it is as close as 1,000 li;

From the Jiang River to the Heng1 Mountain, it is as far as 1,000 li.

East → West

From the Eastern He to the Eastern Sea it is as far as 1,000 li;

From the Eastern He to the Western He, it is as close as 1,000 li;

From the Western He to the Flowing Sand, it is as far as 1,000 li.