Introduction

In October 2018 a group of students at Texas A&M University in College Station, TX (hereafter TAMU) ignited controversy when they altered a portion of a ritual known as the Elephant Walk, which had, since 1926, gathered graduating seniors together at the foot of a Confederate statue on campus. The Elephant Walk, a tradition meant to foster a sense of nostalgia and community for the graduating class, had historically included a silent moment of reflection at the foot of a memorial statue that generations of AggiesFootnote 1 affectionately refer to as “Sully,” named for the Confederate general and quintessential Texas country boy, Lawrence Sullivan Ross (1838–1898). This statue and the kinds of identities it represents remain a flashpoint in conversations about Texas and the Confederacy not only because of Ross’s well-documented defense of slavery and segregation, but also because for generations, his role in the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) has been mythologized at TAMU.

The decision to skip the Elephant Walk’s “Sully stop,” as it is known among the students of TAMU, ignited outrage from alumni and from university officials. In response to the controversy, an undergraduate student in charge of the event reflected on the mounting criticism of the monument in an op-ed in the student paper, The Battalion:

Walking silently past the statue of Sul Ross is not disrespectful, and it should not be interpreted as such. It should not be interpreted as an angry call to remove the statue from campus, and definitely not as ignoring or erasing history. [We] are simply aware that Ross put his life on the line fighting against the U.S. to uphold the practice of slavery, among other political actions he took to disenfranchise people of color… No one is questioning or debating his great skill as a leader; some students are only concerned by the vision he had as one. Black students were not admitted under his watch, and the only female students were “honorary members,” exclusively the daughters of faculty…I merely state this as fact, not as retaliation to other public statements made about the statue

(Tisch Reference Tisch2018).The backlash against the statement above was swift. Though the debates about the Sully statue have existed primarily among the students for years now—this was how I came to become aware of the issue since these conversations often spilled into my classroom during my time as an assistant professor at TAMU—the chancellor of the university system and a self-professed country boy himself, John Sharp, felt strongly enough that he published a strong rebuke in the student paper on Thanksgiving Day. In his letter, he characterized any acknowledgement of Sul Ross’s ties to the Confederacy, segregation, and the KKK as an “attack” and declared that “Lawrence Sullivan Ross will have his statue at Texas A&M forever, not because of obstinance, but because he deserves the honor with a lifetime of service to ALL TEXANS and ALL AGGIES” (Sharp Reference Sharp2018, emphasis in original).Footnote 2

#yeeyeenation

The calls to remove or, at the very least, reframe the legacy of Sul Ross, and the controversy these calls have sparked in response, underscore who is or is not counted among “ALL TEXANS” or “ALL AGGIES.” In this article I refer to the collectivist signposting and semantic slippage on display in rhetoric like Sharp’s by one of the mechanisms through which such sentiments aggregate and produce intimacy in public spaces today—hashtags. The hashtags #yeeyee or #yeeyeenation, which circulate primarily on social media platforms like Instagram and Facebook, index what are broadly characterized as signs of a country boy life in Texas. These signs range from photos of lifted pick-up trucks with Confederate and Make America Great Again (MAGA) flags or blonde, White women in bikinis brandishing semi-automatic firearms, to celebratory scenes of hunting and fishing. In recent years these phrases and hashtags have increasingly been utilized by individuals on social media platforms to refer to the kind of life that is represented by TAMU alumnus, country music artist, and social media influencer, Granger Smith a.k.a. Earl Dibbles Jr. (see Figure 1). Since at least 2014, Smith has adopted the phrase “yee-yee” in his brand development and music—music which is then adopted by TAMU in its promotional materials. In other words, Smith and TAMU are tethered to each other through this phrase and the kinds of cultural processes and products it references in majority White public spaces.

Fig. 1. Screenshot from TAMU Athletics department, April 18, 2017

Mythopoetics

In this article I bring together analytical tools from country music and performance studies (Fox Reference Fox2004; Taylor Reference Taylor2003, Reference Taylor2012), digital and hashtag ethnography (Bonilla and Rosa, Reference Bonilla and Rosa2015; Hjorth et al., Reference Hjorth, Horst, Galloway and Bell2017; Postill and Pink, Reference Postill and Pink2012), and affect, critical race, and Black Feminist Theory (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2010; Cottom Reference Cottom2021; hooks Reference hooks1992) to interrogate the formations of history and power at work in the cultural space understood as #yeeyeenation. I refer to the racialized and aestheticized logics that characterize this cultural space using the term mythopoetics.Footnote 3 Mythopoetics captures the way country boy myths of White innocence, such as the ones found in and around Sul Ross, Granger Smith, and more generally across majority White spaces, overlap and aggregate through poetics—that is, the sonic, discursive, and expressive practices that engender “race-specific effects” and publics (Kerkering Reference Kerkering2003, p. 2). I argue that the logics of “White racial framing” (Feagin Reference Feagin2013) upon which such effects are predicated normalize a rhetoric—in this case, that something or someone “is not racist”—even in the face of evidence to the contrary.

Focusing on examples that extend from, but are not specific to Texas, I develop the theory of mythopoetics to expose the aestheticization of White male innocence and supremacy in public cultures.Footnote 4 Extending the insights of scholarship (see Strother et al., Reference Strother, Piston and Ogorzalek2017) on how the logics of “tradition” and “pride” often require and even endorse historiographical airbrushing, such as the kind found in Lost Cause narratives,Footnote 5 I examine how White identities and related genealogies in the U.S. context are not simply established to historicize expressions of racist, gendered, and exclusionary thought, but are sustained by empirical deceptions. These deceptions, which become embedded in public culture through mythopoetics, rely on myopic and materialist definitions of evidence or “proof” and support claims of deniability.

Mythopoetics are at work across a wide variety of public U.S. institutions—from electoral politics to higher education—and must be understood as existing on a spectrum considering the number of politicians who go on to join the ranks of the academy and vice versa. These social and political circuits in turn normalize discursive forms of White male hegemony within U.S. American public cultures, from linguistic practices of institutionalism and its legal parameters (see Lipsitz Reference Lipsitz1998, Moore and Bell, Reference Moore and Bell2017) to everyday sonic experiences and expressions of belonging (see Hill Reference Hill1998, Meek Reference Meek2006). It only follows, then, that such poetics are particularly on display when, for example, calls to remove a monument on the grounds that it represents racial injustice are answered, as Sharp’s words make clear, by a claim that there is a universal, singular way to experience citizenship or belonging as either a Texan or an Aggie.Footnote 6

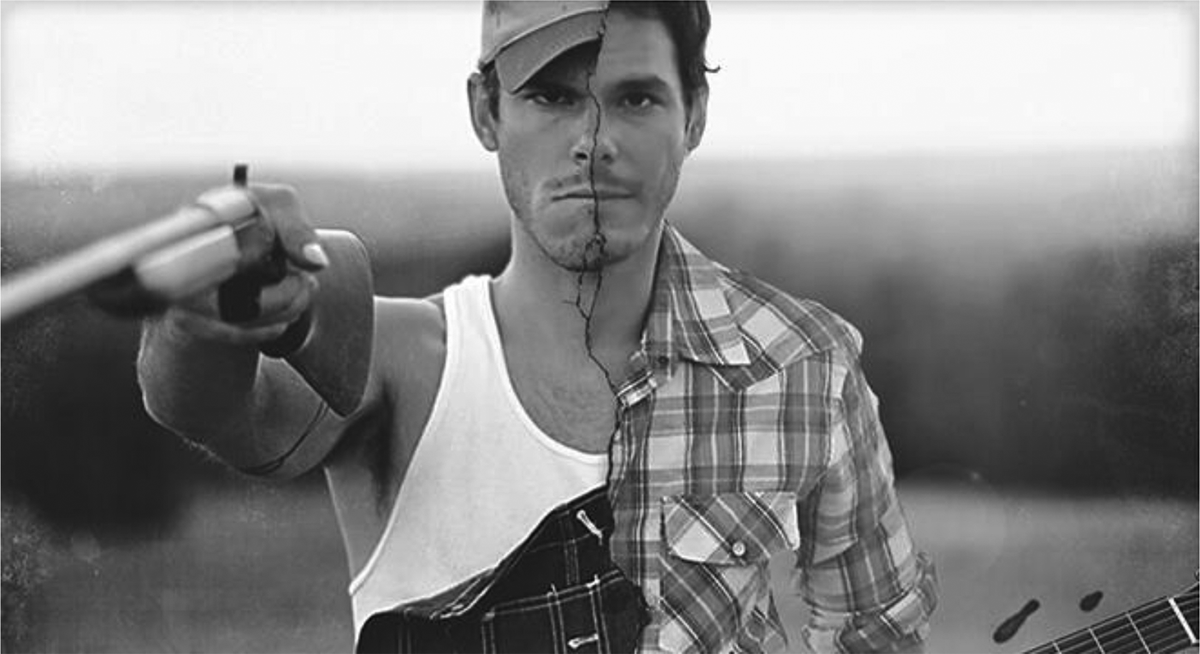

In this article I theorize mythopoetics to both illuminate the foundations of Sharp’s claim, which allow him to defend a segregationist, and to situate the cultural politics of Sharp’s position within a much larger conversation about the extractive and White replacement imperatives of settler colonialism in public institutions (see especially Stein Reference Stein2016 and Reference Stein2017).Footnote 7 In order to connect and theorize the performative space of a public institution to a more expansive and capacious category of public culture, I bring the rhetorical logics of mythopoetics that are used to defend Sully into conversation with those used to market Granger Smith and his brand. Smith’s dual persona (see Figure 2) demonstrates the role of mythopoetics and its raced as well as gendered imperatives in U.S. public cultures. Much like the defenses of Ross mounted by TAMU officials—that there is no concrete evidence of malintent or “true” racism—Smith’s cultural appeal is predicated on a carefully curated polysemic, innocently packaged by the nostalgia country music provides (Mann Reference Mann2008), and the affective power that expressions of Whiteness, especially working-class or “redneck” Whiteness, upholds in public culture (Hubbs Reference Hubbs2014; Roediger Reference Roediger1991). Like defenses of Sul Ross, Granger has also deployed ‘“plausible deniability,’ [which] is…central for the communication of modern racism,” to both build and maintain his brand, Yee-Yee (Liu and Mills, Reference Liu and Mills2006). Below, I examine Smith’s career to better understand the defenses of Sul Ross, particularly since Smith is also known for his “country” and patriotic alter-ego, Earl Dibbles Jr. In analyzing Smith’s career as well as the way he and his management team frame his appeal in interviews, I examine how his success is a testament to the power and reach of mythopoetics in a hegemonic White and heteropatriarchal society.

Fig. 2. Granger Smith (R) and Earl Dibbles Jr. (L) promotional photo

This article demonstrates why mythopoetics are essential to majoritarian cultural formations today and exposes how such discursive gestures normalize White supremacist thought to such a point that its violence can circulate without consequence and in plain sight. This is the political power of mythopoetics in the United States—the ability to operate with impunity on moral and legal registers known variously as “civility” or “free speech.” Indeed, mythopoetics form the foundation upon which two pillars of White public culture remain firmly situated in the U.S. context—institutions of higher education and country music publics. By bringing these two cultural spaces into one ethnographic frame and treating both as mutually constitutive forms of White publics, it becomes possible to see and hear the aestheticized means and affective methods by which White identity is predicated on racist thought, but performed as nostalgia and tradition.

To make this case, I first examine the career of Granger Smith and then connect his career to formations and expressions of White masculinity that emerge from Aggieland. Second, I explore how mythopoetics circulate through social media, overlapping with partisan affiliations and politics of recognition in the contemporary moment.Footnote 8 In the final section, I extend my analysis of #yeeyeenation to the events of January 6, 2021, when White nationalist mobs stormed the Capitol building in Washington D.C.

Country Boy Songs

I should admit at this juncture that I had never heard of Granger Smith until I began teaching at TAMU. Though he had been famous among Aggies for some time, with his track “We Bleed Maroon” (2006), dedicated to TAMU and now considered the unofficial song of Aggie football, he did not achieve commercial recognition until 2015 with the track “Backroad Song.” “Backroad Song” experienced notable commercial radio play while I was a faculty member at TAMU, playing as it did on FM 96.1 (KAGG) almost every hour, on the hour, for much of my first year there. In many ways, Smith’s success with “Backroad Song” can and should be attributed to the fact that he was signed by a major Nashville label, Wheelhouse Records (a subsidiary of BBR Music group), which also represented male cross-over artists like Zac Brown Band and Kid Rock. Like several male country artists recently, Smith did not register at all on country radio or Billboard charts until he secured himself a position in the Nashville “hit machine” (see Pecknold Reference Pecknold2007, Reference Pecknold, Lashua, Spracklen and Wagg2014; Sanjek Reference Sanjek1995). While “Backroad Song” is characterized by the label as “country,” the musical language, especially the instrumentation and twangy, yodel-esque vocals, rely on what could more broadly be described as rock or pop. Cross-over appeal is arguably a tried-and-true strategy for new artists to find a foothold, particularly those, like Smith, who exist primarily in the bro-country category, a raced and gendered aesthetic where White men sing about “trucks and dirt roads” (Neal Reference Neal, Pecknold and McCusker2016, p. 3). Male artists with similar sounds to Smith, like Cole Swindell, have followed related routes to commercial success, modeling their careers on the bro-country icon, Luke Bryan (see also Pruitt Reference Pruitt2019).

In this regard, Smith’s career prompts a consideration of the broader historical trajectory of commercial country music as well as the way Whiteness tends to remain deracinated in public culture. As many scholars have noted, country music has, since its earliest commercial iterations, revealed ongoing and emerging constructions of heteronormative and White masculinity in public culture (Bertrand Reference Bertrand2004; Miller Reference Karl Hagstrom2010; Pecknold Reference Pecknold2004; Peterson Reference Peterson1997). Specifically, Smith’s performance of White masculinity belongs to a well-established pattern of singing, guitar-playing, self-described “country boys.”Footnote 9 The country boy trope in commercial country music not only aestheticizes Whiteness and masculinity in ways that circulate and generate racial identities, but also suggests that the musical performances of these “boys” are youthful, harmless, or playful. Put another way, country boys are not to be taken seriously or at their word—a truism that captures the way the cultural valence of the phrase allows for moves to innocence in White public spaces.

To understand how these moves to innocence operate, both sonically and discursively, it is important to know that Smith became well-known as a county music artist on social media under the name Earl Dibbles Jr. During my time at TAMU, I learned from my students that years before Smith’s achieved commercial success, he and his brother had released a YouTube video in 2011 titled “The Country Boy Song.” This song, which is now one of many that Smith has released under the name of his alter-ego, Earl Dibbles Jr., is arguably meant to be understood as parody or satire.Footnote 10 In “Country Boy Song,” for example, Dibbles sings with an overwrought “twang” about the life of the average “boy” who lives in the “country” and enjoys the life such a location affords him:

“The Country Boy Song” and the accompanying music video provide an evocative example of how mythopoetics circulate and aggregate attachments to Whiteness and country music in the twenty-first century. Smith, like many male country artists before him, recycles a familiar series of signs of what a country boy life entails. For example, in the song, besides rehearsing a common White settler replacement narrative about having “Cherokee blood,” Smith glorifies what he describes as the “redneck life,” extolling its virtues (see TallBear Reference TallBear2021). Importantly, this life is contrasted with the city life, which is cast as wealthy, but otherwise lacking in substance. The country life is one of autonomy, signaled by morning beers and copious amounts of chewing tobacco. In “The Country Boy Song,” Smith’s alter-ego, Earl Dibbles Jr., sings about the personal agency he has compared to his city counterparts, a sense of freedom and patriotism that is signaled by his twang and his yodel-esque vocalization, “Yee-Yee!” In his songs (see figure 3), Dibbles often combines this call with hoisting his gun in the air or waving an adapted Gadsen FlagFootnote 11 that reads “Don’t Tread on Me.”

Fig. 3. Still from “Don’t Tread on Me” (2017) by Earl Dibbles Jr.

Early in 2017, at the behest of my students at TAMU, I reached out to Smith and was pleasantly surprised to receive a response. He and his brother-manager were going to be in the area, and they agreed to come speak to my class. After a brief presentation, in which Smith shared that he had grown up in a wealthy suburb of Dallas before attending TAMU, and his brother held up a few items from their new line of merchandise, Yee-Yee Nation, Smith agreed to field a few questions from my students. The questions were timid at first, mostly asking Smith about his time at TAMU when he was a student. After a few polite biographical questions, however, the front row of the classroom began to ask Smith about his politics. Specifically, how did he feel about the fact that his brand was often promoted on Instagram by those who were supporters of Donald Trump? Why did he allow his brand to draw on symbols of White supremacy, like the Confederate flag? Was he in favor of a ban on assault rifles? Had he or anyone in his family served in the military? Was that why his music had patriotic themes? Did he vote for Donald Trump? Did he vote for Barack Obama? The students pressed Smith for firm answers, even the ones I knew were star-struck fans. As I watched and listened to them repeat the same questions, despite not receiving different answers, it became clear, as they later admitted to me, that they wanted to hear him say something more genuine—that he did not support racist symbols, that he was not supporting racism, but rather “honoring tradition,” a common phrase for apologists and equivocators.

The questions caught me off guard, but Smith was ready for them. With expert ease, he sidestepped each question. He alluded to his support of Obama. He also seemed to indicate that he was not a supporter of Donald Trump’s policies, but redirected, stating again that his music was not meant to be interpreted through a political lens. He made music for people to “escape,” he said. He suggested that his music was meant for fun, as a respite from reality. More importantly, instead of speaking to the concern that his fans used his music to express affinity for White supremacist ideas, Smith deflected, stating that he personally never used a Confederate flag, nor did he draw upon Donald Trump’s MAGA symbols in his visuals, though his alter-ego Earl Dibbles Jr. might.

Despite his careful word choice, it is abundantly clear that Smith has consistently participated in blurring the lines between his identity and his alter-ego. Moreover, despite his attempts to distance himself from MAGA identity politics, Smith’s success is arguably both cause and result of the post-2016 political moment in which White nationalists have found an outlet through social media and the anonymity online spaces offer (Meyer Reference Meyer2021). In other words, Smith’s success, despite his claims to neutrality, can and must be understood as an extension of the broader political landscape where it has become increasingly acceptable for White protestors to, for example, rely on the polysemy of the Gadsen flag to make specious claims to constitutional rights. After all, to suggest, as one interlocutor did to me, that the phrase “Don’t Tread on Me” and the Gadsen flag are uncomplicated evocations of the U.S. American Revolution would be akin to suggesting that the swastika as a symbol is simply an expression of peace since that was its original use in the South Asian context.Footnote 12 Such willfully ignorant logic is common, not only among those who support more virulent forms of hate today, but notably, among even those self-identified “liberal” White populations in the United States who seem to misunderstand that the distinction between heritage and hate is not simply a matter of perspective, much less historicity (Kailin Reference Kailin1999).

Sonic Traditions and Hashtag Communities

In retrospect, I can understand why my students were asking Smith to disavow racism on behalf of all Aggies. There had recently been a controversy where two Black prospective students from Uplift Hampton Preparatory School in Dallas, Texas were confronted by a White, female Aggie during a campus tour. The confrontation stemmed from the White student asking the Black students for their opinion on her Confederate flag earrings. A group of White TAMU students reportedly overheard this and joining the student who was showing off her earrings, confronted the group of Uplift students telling them to “go back where you came from.” These White students reportedly used the N-word and made more references to the Confederate flag to underscore their allegiances to White supremacy. In the weeks that followed this event, the conversation seemed to focus on whether it was possible to use the visual significance of the Confederate flag or the spoken, sonic meaning of the N-word in a manner that did not represent racist beliefs. Defenders of the group of White students who had harassed the visiting Black students argued that the Confederate flag represented tradition and that their choice of language did not meet the standards for racist or discriminatory speech. The rhetoric of “it’s tradition” as well as “that’s not what it means” has long been wielded as a defense against any criticism of Aggie culture and its tacit support of White supremacy. Knowing this context, I understood why the students wanted to know how Smith, as a fellow Aggie-turned-country-star, felt about using symbols of White supremacy, like the Confederate flag. After all, his 2006 anthem, “We Bleed Maroon,” is often played during Aggie football games and his music is otherwise culturally synonymous with “Aggie Nation” as well as its identity as a militaristic, majority White, male student body (McCluskey Reference McCluskey2019; Newman Reference Newman2007).

In this regard, the TAMU identity that Smith-Dibbles represents is made particularly audible and visible through Aggie cultural symbols known as yell leaders (see Figure 4). Yell leaders at TAMU are White male students who, dressed in all white clothing, lead rituals known as “yells” during football games, wherein the student body supports their team by chanting phrases such as “Farmers Fight.”

Fig. 4. Aggie Yell Leaders.

Source: Houston Chronicle

Yell leaders are functionally Aggie celebrities, and so operate as icons for the institution and its cultural identity. The chorus of Smith’s Aggie anthem, “We Bleed Maroon,” explicitly signals the importance of yell leaders as well as Sul Ross’s monument within the ritual practices of Aggie identity:

Smith’s music, particularly the chorus (above) highlights the performative and sonic practices which tether Aggie identity to the mythopoetics of White public culture. Putting a penny on Sully’s statue and yelling “farmers fight,” for example, are both performative behaviors that define citizenship for Aggies. More importantly, both rituals rely on a very specific understanding of what Aggies value—namely a Confederate general and a vocal tradition that can be traced directly to the communal practices of the Confederate army. “Farmers fight” and other yells like Dibbles’ signature “yee-yee” are not simply innocent “cheers” that the student body passes down from generation to generation, but are vestiges of the Confederate army whose traditions remain central to sound cultures at institutions like TAMU. As scholars of the Confederacy and its recent expressions at the University of Virginia have noted, these White male sound cultures, particularly their linguistic, pitch, and timbrel qualities, cannot and should not be valorized as apolitical forms of tradition, but rather must be understood, as sonic “reverberations of white supremacy” (Chattleton Reference Chattleton2018).

On that day when Smith and his brother-manager, Tyler, visited my classroom, a series of follow-up questions asked Smith to clarify his position on several issues specific to Aggie politics. For example, the students wanted to know if he agreed with the decision to leave the Sul Ross statue on campus without modification. They also wanted him to acknowledge that his alter-ego, Earl Dibbles Jr., especially his signature twangy yell, “yee-yee,” was increasingly referenced by those supporting Donald Trump (see Figure 5).

Fig. 5. Still photo from Instagram aligning a Yee-Yee flag with a Trump 2020 MAGA flag

Tyler intervened at this point, telling the class a bit about the newest collaboration to which Yee-Yee Nation had agreed and revealed that they were excitedly looking forward to releasing their own line of beverages, likely energy drinks or beer. He held up a few items from their online store and mentioned that the new products would be marketed with the same imagery that both he and Granger were wearing that day on trucker hats: the phrase “Yee-Yee” and a shotgun. In shifting the conversation away from the implications of the Yee-Yee brand towards what amounted to a sales pitch, he encouraged my students to follow Yee-Yee Nation on Instagram and use the hashtags “#yeeyee” and “#yeeyeenation” in their everyday life to help “support a fellow Ag” as he built a name for himself in Nashville and the larger country music scene. Though my students tried to engage Granger more substantively a few more times before the end of the session, asking him, almost pleading with him to use his platform to stand against racist speech and symbols, Smith did not confirm or deny that he would. Instead, he flashed his signature, bright smile and took a photo with the class before he and his brother left for another meeting on campus, with the football program.

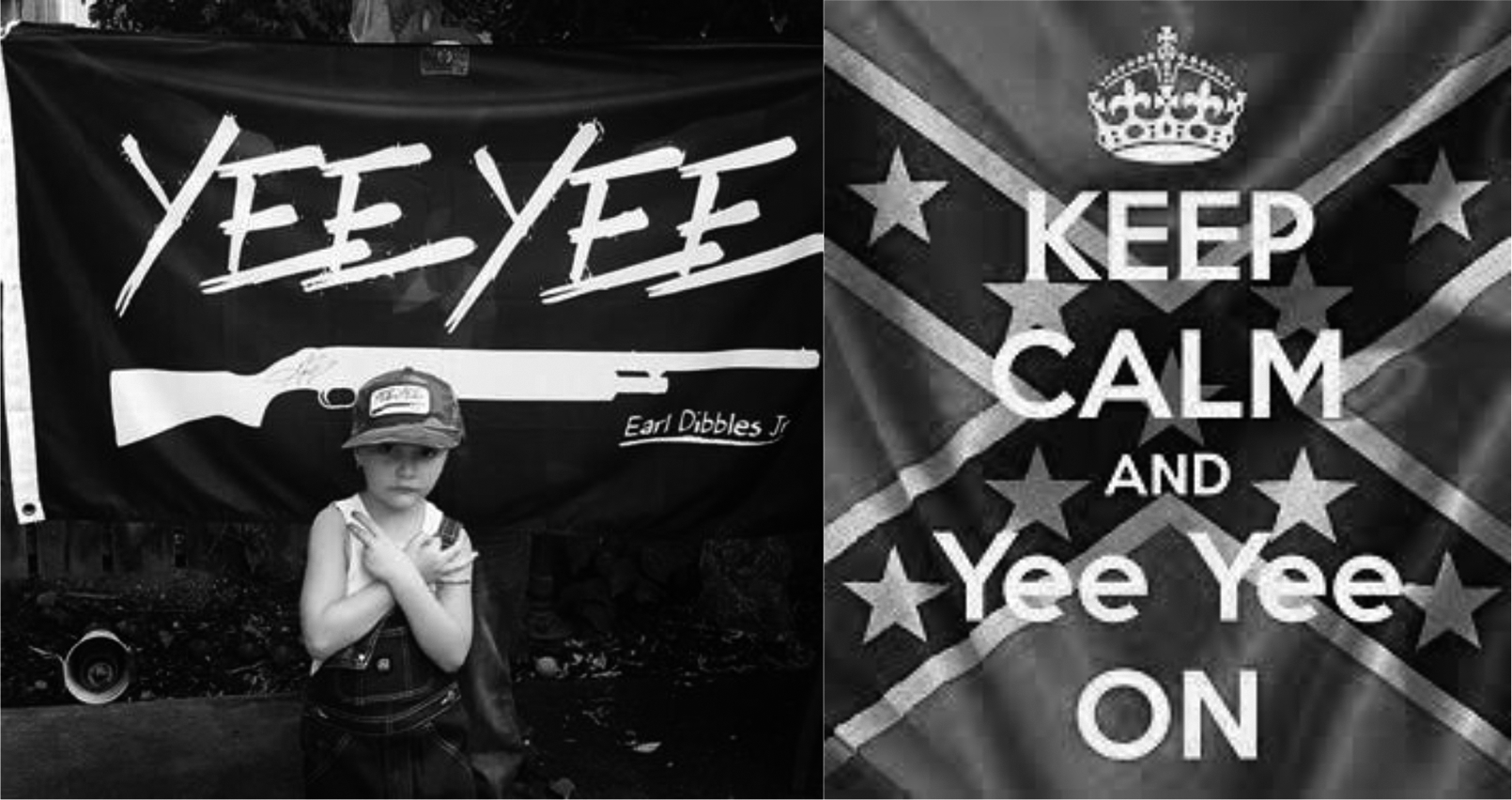

As has become his trademark since his interaction with my class, Smith rarely acknowledges the impact that his music and messaging have on political conversations. Whether he is willing to admit it or not, however, Smith has built a brand through, not in spite of, his dual identity. In his own words, “the blurrier we can make those lines, the better,” says Smith, of the distinction between his two personas. “If it’s a strict black and white — Earl and Granger — then it doesn’t connect the dots. And the whole purpose of Earl is to connect the dots back to Granger. It wasn’t to create a separate entity, a separate figure that had a separate following. The whole purpose was, it’s all one big following” (Smith quoted in Freeman Reference Freeman2016). In other words, the branding of Yee-Yee and the creation of a consumer product line predicated on White supremacist thought seems essential to Smith’s success. By his own logic, one could reasonably argue that Smith owes his success to Dibbles and the identifications Dibbles reflects. After “Backroad Song” charted it was Dibbles’ persona which set Smith apart from his competition—a strategy he acknowledges and embraces. To be sure, Smith has built his brand recognition through Dibbles’ signature gun-waving yell, “yee-yee.” And the Yee-Yee brand and its consumption are now unequivocally participating in White supremacist identity formation and expressions of “White power” (see Figure 6).

Fig. 6. Fan photos using various flags associated with Earl Dibbles Jr. (L) A young White girl is holding up white power hand symbols in front of Yee Yee flag. On right, the background flag is a confederate or “rebel” flag.

Through Yee-Yee Nation Smith has established a brand that aestheticizes White supremacy thus making its impact easy to deny. One need only spend a few moments browsing through the #yeeyeenation Instagram feed to understand how central Earl Dibbles Jr. and his rhetoric of “I’m just a country boy” are to political formations known colloquially today as the “Trump Train” or “MAGA”—both of which refer to supporters of former President Donald J. Trump and the denial that Trump lost the presidential election of 2020 (see also McVeigh and Estep, Reference McVeigh and Estep2019). Contrary to Smith’s equivocations, his influence on political conversations and partisan rhetoric is abundantly clear if one simply tracks the way #yeeyeenation circulates and is sourced to signal a wide variety of conservative political positions, from anti-gun control to anti-immigration. He and his brother have achieved success through a lifestyle brand loosely attached to a music career that curates and overlays existing symbols of White supremacy all while denying how and why such symbols produce affective tethers for consumers and participants. Put another way, the aestheticization of White supremacy produces rhetorical deniability—what I have theorized here as mythopoetics. In turn, this mechanism of deniability is foundational to both the construction and maintenance of White public cultures.

Conclusion

In the years since Smith and his brother visited my class, the controversy about Sul Ross’s statue on TAMU’s campus has grown louder. Since 2018, conversation has (re)emerged about how TAMU leadership might address the concerns expressed by the minority student population. Some have suggested managing the perception that TAMU harbors White supremacists by advocating for another statue—one of a Black senator, Matthew Gaines, the first African-American legislator in Texas.Footnote 13 The irony of erecting a monument to a Black senator on campus when he could not have attended TAMU during his own lifetime notwithstanding, the idea that a statue would somehow address student concerns points to how White institutions rely on the strategic deployment of mythopoetics to maintain the White racial frame. The proposal for the Gaines statue remains a point of discomfort among members of the TAMU majority White community, most recently because of a debate as to whether the words “former slave” should appear on the plaque beneath the statue.Footnote 14

The aesthetic, symbolic, and discursive strategies by which predominantly White institutions represent and remember their past, including connections to the economic legacy of slavery, require more attention, not just at TAMU or in the country music industry, but across public cultures in the United States. As these connections are exposed and addressed, we can expect ever more reliance on mythopoetics. In this regard, the mechanisms by which both institutions and individuals airbrush history function as a necessary tool in how White supremacy shapes what we consider history. As long as the primary target audience remains predominantly White, in both TAMU’s case as well as in Smith’s, the questions around whose history counts as history and what symbols mean, can be managed, curated, and denied.Footnote 15 As Smith’s brand relies on the innocence of “country boy” aesthetics to fan the flames of White supremacist thought while simultaneously denying any political intentions, TAMU can defend Ross’s legacy and continue to silence the past, all the while claiming to represent ALL AGGIES. To be sure, the consequences of such discursive gestures appeared in sharp relief on January 6, 2021, when a group of Trump supporters stormed the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, D.C., claiming that they were acting in the interest of all Americans. As footage from that day clearly demonstrates, both the Confederate and Gadsen flags, including updated designs and versions sold by Granger Smith on his website, featured prominently as symbols of the insurrection.

In the years since I began this research, #yeeyeenation has grown far beyond the scope of this article. Today #yeeyeenation not only signposts Granger Smith and his brand on social media platforms like Instagram, but also appears in tandem with insurrectionist and misinformation expressions like #stopthesteal, #trumpwon, #1776, #donttreadonme, and #letsgobrandon, among others. Ultimately, #yeeyeenation, exhibits but an instance of how mythopoetics can normalize violence through claims of innocence, often couched in the overdetermined morality of identity, patriotism, and, of course, country.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Sharon Stein, Aaron A. Fox, Travis. A. Jackson, Harris Berger, Anna Schultz, Jon Bullock, and three anonymous readers for their feedback and edits. I would also like to express my gratitude to my students and my intellectual community at Earlham College, with whom this research project first came into focus. At Texas A&M University, I want to thank Xóchitl Fuentes, Jonna Martin, Olivia Schutt, Chris Cepeda, and Ezra Skeete.