INTRODUCTION

Since the early 1900s, scholars have consistently documented a graded pattern such that higher levels of psychological distress are found among those with low socioeconomic status (SES) and diminish as SES increases (Adler and Rehkopf, Reference Adler and Rehkopf2008). Importantly, the bulk of population-based studies that have yielded these findings in the United States utilized datasets inclusive of all racial/ethnic groups, the samples of which are often dominated by Whites and therefore tend to highlight patterns among the White majority (e.g., Mirowsky and Ross, Reference Mirowsky and Ross2003). Scholarship examining the SES–psychological distress relationship among racial/ethnic minority groups, and African Americans in particular, has yielded inconsistent results (Pearson Reference Pearson2008; Williams Reference Williams2018), indicating that our understanding of how socioeconomic factors shape psychological distress among African Americans is an unresolved area of inquiry.

Exposure to economic, social, and legal discrimination throughout the eras of slavery, Jim Crow, and mass incarceration have uniquely shaped African Americans’ opportunities to access and accumulate socioeconomic resources. Today, African Americans are disproportionately represented among those who grow up poor, live in hyper-segregated neighborhoods, attend underperforming schools, or are unemployed. In addition, African Americans with higher educational attainment typically earn less and accumulate less wealth than equivalently educated members of other racial/ethnic groups (Williams and Collins, Reference Williams and Collins1995). Accessing socioeconomic resources may be even more difficult for African Americans residing in post-industrial cities such as Detroit, Flint, Buffalo, and Binghamton, where the combination of globalization, intense competition, technological advancements, and the movement of work from inner cities to the suburbs began to catalyze economic decline in the late 1950s (Farley et al., Reference Farley, Danziger and Holzer2000; Wilson Reference Wilson1997).

More recently, the Great Recession, which was particularly damaging for African Americans, resulted in a 10% rise in U.S. unemployment and the erasure of $7 trillion in household wealth (Mishel et al., Reference Mishel, Bivens, Gould and Shierholz2012). Prior scholarship has found that recessions induce changes in individuals’ and communities’ access to socioeconomic resources and are linked with poor mental health. Widespread loss of jobs, assets, and benefits are associated with increased stress, psychological distress, and depressive symptoms, especially among working-age individuals (Burgard and Kalousova, Reference Burgard and Kalousova2015; Riumallo-Herl et al., Reference Riumallo-Herl, Basu, Stuckler, Courtin and Avendano2014), while persistent unemployment can spur material hardship and subsequent mental health declines (Burgard et al., Reference Burgard, Ailshire and Kalousova2013). The housing instability and increased foreclosures associated with the Great Recession have been linked with increased psychological distress (Burgard and Kalousova, Reference Burgard and Kalousova2015), anxiety attacks (Burgard et al., Reference Burgard, Seefeldt and Zelner2012), and depressive symptoms (Cagney et al., Reference Cagney, Browning, Iveniuk and English2014; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Nandi, Keyes, Uddin, Aiello, Galea and Koenen2012; Settels Reference Settels2020) among U.S. adults. The Great Recession devastated African Americans’ access to material resources, as the Black unemployment rate rose to 16% and median wealth among Black households fell 33.7% to $11,000 (Kochhar and Fry, Reference Kochhar and Fry2014; Shapiro Reference Shapiro2017). Less is known, however, about how African American communities that were socioeconomically marginalized prior to The Great Recession fared psychologically in the wake of this financial crisis.

Guided by the Stress Process Model (Pearlin Reference Pearlin1989), this study uses data from the Detroit Neighborhood Health Study (DNHS) to advance understanding of how socioeconomic factors shape psychological distress among African Americans. I first examine the association between multiple dimensions of SES and two measures of psychological distress among working-age African Americans in the wake of the Great Recession. Second, I test whether social factors mediate the relationships between SES and psychological distress. Third, I examine whether gender modifies the SES–psychological distress relationship and/or the social factors that explain the SES–psychological distress relationship. This study advances prior research on socioeconomic differences in psychological health by examining these relationships, and testing the mediating and moderating processes that explain them, within a unique, population-representative sample of African Americans. Results highlight that among working-age African Americans residing in disadvantaged socioeconomic contexts, complex relationships between SES, gender, and social factors contribute to the etiology of psychological distress.

BACKGROUND

Socioeconomic Predictors of Psychological Distress

While scholars have studied the association between SES and psychological distress for over a century, debate over the causal direction of this relationship is ongoing. However, a preponderance of evidence suggests the causal direction depends on the mental health outcome or disorder under study. More specifically, accumulated evidence suggests that among psychological disorders that are severely disabling, and have high levels of inheritance and developmentally early biological origins (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder), causality tends to flow from psychological health to SES (the social selection hypothesis) (Eaton and Muntaner, Reference Eaton, Muntaner, Scheid and Wright2017; Muntaner et al., Reference Muntaner, Ng, Vanroelen, Eaton, Aneshensel, Phelan and Bierman2013). Conversely, among conditions that are less influenced by heritable factors and produce variable levels of disability (e.g., depression, anxiety) the bulk of evidence supports the social causation hypothesis, such that causality predominantly flows in a graded fashion from SES to psychological health (Eaton and Muntaner, Reference Eaton, Muntaner, Scheid and Wright2017; Muntaner et al., Reference Muntaner, Ng, Vanroelen, Eaton, Aneshensel, Phelan and Bierman2013).

Scholars first documented a graded association between SES and psychological distress in the early 1900s and repeatedly confirmed this finding in cross-sectional and longitudinal community-based and nationally representative studies throughout the twentieth century (Mirowsky and Ross, Reference Mirowsky and Ross2003; Muntaner et al., Reference Muntaner, Ng, Vanroelen, Eaton, Aneshensel, Phelan and Bierman2013). The most widely accepted causal explanation for this graded association is that increased stress accompanies lower socioeconomic standing, thereby inducing psychological distress (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Wheaton and Lloyd1995). This explanation is theoretically grounded in the stress process model, which postulates that population variation in psychological distress stems from the unequal distribution of stressors and protective resources, which are socially patterned. Acute and chronic stressors arise from the context of people’s lives and can increase psychological distress, while access to protective resources can mitigate the relationship between stressors and psychological distress (Pearlin Reference Pearlin1989). Within the context of SES, those with fewer socioeconomic resources are expected to experience more psychological distress and have fewer resources to cope with that stress than those with higher SES.

At the same time, socioeconomic indicators are not interchangeable; they each capture a unique dimension of the process linking access to resources and psychological distress (Braveman et al., Reference Braveman, Cubbin, Egerter, Chideya, Marchi, Metzler and Posner2005). For example, education enhances the knowledge and cognitive skills that facilitate problem solving and development of healthy lifestyles, including the ability to cope with acute and chronic stressors (Schnittker and McLeod, Reference Schnittker and McLeod2005). High educational attainment begets opportunities for fulltime employment, higher incomes, and wealth accumulation, which can also alleviate psychological stress generated from material hardship. Those with higher incomes can generally access resources to better cope with psychological distress, while those with very low household income may experience increased risk of psychological distress with fewer resources to cope with such distress (Sareen et al., Reference Sareen, Afifi, McMillan and Asmundson2011). In addition, employment status is a particularly salient component of SES among the working-age population. Prior work on the SES–psychological distress relationship has conceptualized employment status as a component of SES (Gavin et al., Reference Gavin, Walton, Chae, Alegria, Jackson and Takeuchi2010; Williams et al., Reference Williams, González, Neighbors, Nesse, Abelson, Sweetman and Jackson2007), as paid employment influences individuals’ social status, and poor-quality employment and unemployment, in particular, are linked with psychological distress. For example, perceived job insecurity and unemployment are associated with increased depressive symptoms due to chronic uncertainty, financial strain, loss of social status, and increased unstructured time (Burgard and Seelye, Reference Burgard and Seelye2017; Dooley Reference Dooley2003). A causal relationship between unemployment and depression has been found after controlling for the seqeulae of stressors that accompany unemployment (Zimmerman and Katon, Reference Zimmerman and Katon2005), and meta-analyses of longitudinal studies and natural experiments also support the assertion that unemployment causes psychological distress (Paul and Moser, Reference Paul and Moser2009). Importantly, employment status is a socioeconomic indicator that is inclusive of individuals both inside and outside of the labor force, and reduces underestimation of socioeconomic differentials that would otherwise occur through use of a measure of occupational prestige (Braveman et al., Reference Braveman, Cubbin, Egerter, Chideya, Marchi, Metzler and Posner2005; Galobardes et al., Reference Galobardes, Shaw, Lawlor and Lynch2006).

While prior research lays the foundation for understanding how various components of SES generally relate to psychological distress, the bulk of prior studies utilized samples that were entirely, or primarily, comprised of Whites. Given that African Americans’ lived experiences in a racially stratified society are qualitatively different from the majority of Whites, socioeconomic measures collected from African Americans capture lived experiences that are unique to this sociodemographic group and reflect barriers that have uniquely stymied opportunities to access and accumulate socioeconomic resources (Williams and Collins, Reference Williams and Collins1995; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Priest and Anderson2016). Scholars have argued convincingly that within-group analytical specifications are most appropriate for examining the mental health status and correlates of sociodemographic groups (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Donato, Laske, Duncan, Aneshensel, Phelan and Alex2013; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Brown and Hale2017). As such, it is important that research on the SES–psychological distress relationship uses data drawn specifically from African Americans.

The SES–Psychological Distress Relationship among African Americans

The extant literature on the patterning of African American mental health is complex. Studies conducted across several decades have shown that African Americans often report higher rates of psychological distress than Whites. However, some studies document elevated depressive and anxiety symptoms among Whites as compared to Blacks (Williams Reference Williams2018). African Americans also tend to experience lower rates of lifetime and past-year psychiatric disorders than Whites, but when they become ill, their episodes tend to be more severe and persist for longer periods of time (Williams Reference Williams2018). To my knowledge, eight studies have investigated the socioeconomic predictors of psychological distress among African Americans, specifically. These population-based studies yielded inconsistent findings (Assari Reference Assari2018; Assari and Caldwell, Reference Assari and Caldwell2017; Gavin et al., Reference Gavin, Walton, Chae, Alegria, Jackson and Takeuchi2010; Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Neighbors, Geronimus and Jackson2012; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Hooyman, Hill and Rue2013; Mouzon et al., Reference Mouzon, Taylor, Nguyen and Chatters2016; Williams et al., Reference Williams, González, Neighbors, Nesse, Abelson, Sweetman and Jackson2007; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Takeuchi and Adair1992), indicating a need for additional research examining whether and how socioeconomic factors are related to psychological distress among African Americans. Five studies found that African Americans with higher SES experienced lower psychological distress. Shervin Assari (Reference Assari2018) found that while educational attainment was protective against psychological distress and depressive symptoms for African American adults, educational attainment was more protective for African American women. Gillian L. Marshall et al. (Reference Marshall, Hooyman, Hill and Rue2013) documented associations between higher income, higher educational attainment, and lower depressive symptoms. Moreover, Dawne M. Mouzon et al. (Reference Mouzon, Taylor, Nguyen and Chatters2016) found associations between higher income and educational attainment and lower levels of psychological distress. Studies by Amelia R. Gavin et al. (Reference Gavin, Walton, Chae, Alegria, Jackson and Takeuchi2010) and David R. Williams et al. (Reference Williams, González, Neighbors, Nesse, Abelson, Sweetman and Jackson2007) found employed African Americans had lower risk of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Conversely, two studies document higher levels of psychological distress among higher SES African Americans in comparison to their lower-SES counterparts. Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Takeuchi and Adair1992) found that African American men who attained some college were more likely to be diagnosed with depression than their lower educated peers. In addition, Darrell L. Hudson et al. (Reference Hudson, Neighbors, Geronimus and Jackson2012) documented an association between higher household income and higher odds of twelve-month MDD among Black men. Five studies did not find associations between SES and psychological distress. Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Takeuchi and Adair1992) found that a composite measure of SES was unrelated to depression among Black women and men. Furthermore, Williams et al. (Reference Williams, González, Neighbors, Nesse, Abelson, Sweetman and Jackson2007) found that educational attainment and income were not related to MDD risk in African Americans. Gavin et al. (Reference Gavin, Walton, Chae, Alegria, Jackson and Takeuchi2010) did not find significant associations between educational attainment or household income and risk of MDD in African Americans, and Hudson et al. (Reference Hudson, Neighbors, Geronimus and Jackson2012) found that SES was not a significant predictor of depression among Black women. More recently, Shervin Assari and Cleopatra H. Caldwell (Reference Assari2017) found that high income was not protective against MDD among adolescent African American boys.

All but one study (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Takeuchi and Adair1992) utilized data from the National Survey of American Life (2001–2003), a cross-sectional, nationally representative survey of Black Americans. The study by Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Takeuchi and Adair1992) utilized pooled, cross-sectional data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program (1980–1983), which assessed the prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in large community samples across five sites in the United States. All study designs aligned with a social causation hypothesis such that SES predicted psychological health. The studies operationalized SES using measures of education, income, occupation, and/or employment status, and two studies (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Neighbors, Geronimus and Jackson2012; Mouzon et al., Reference Mouzon, Taylor, Nguyen and Chatters2016) incorporated measures of wealth or material hardship. Each study assessed depressive symptoms, MDD, or general psychological distress. No study formally tested the mediating role of social stressors in the SES–psychological distress relationship. Yet, formal tests of mediation in the SES–psychological distress relationship can advance the literature by helping to explain why these associations exist.

It is possible that the inconsistent findings of prior work stem from variation in the age ranges of the analytic samples. Assari and Caldwell (Reference Assari and Caldwell2017) studied African American adolescents; Marshall et al. (Reference Marshall, Hooyman, Hill and Rue2013) studied those age fifty-five and older; and Assari (Reference Assari2018), Gavin et al. (Reference Gavin, Walton, Chae, Alegria, Jackson and Takeuchi2010), Hudson (Reference Hudson, Neighbors, Geronimus and Jackson2012), Mouzon et al. (Reference Mouzon, Taylor, Nguyen and Chatters2016), and Williams et al. (Reference Williams, González, Neighbors, Nesse, Abelson, Sweetman and Jackson2007) included respondents who were eighteen and older. (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Takeuchi and Adair1992 did not specify the age range of their analytical sample.) Specific SES indicators may be more or less meaningful for health at different points in the life course, and the SES–psychological distress relationship may be particularly strong among those who are working-age (e.g., 25–64).

Indeed, working-age African Americans experience a unique set of psychosocial stressors. In contrast to youth or the elderly, the working-age population is most likely to simultaneously juggle multiple responsibilities at work, at home, and in the community. The pressure to fulfill obligations associated with these roles, given limited time and resources, can generate psychological distress (Duxbury et al., Reference Duxbury, Stevenson and Higgins2017). Moreover, working-age African Americans are subject to additional race-related stressors in the form of disproportionately high rates of incarceration, unemployment, and homelessness (Barnes and Bates, Reference Barnes and Bates2017); these experiences can be distressing for those directly affected and for their social and familial networks. The constant vigilance required to navigate structural or interpersonal discrimination in communities, workplaces, and through interactions with various institutions also adversely affects the mental health of African Americans across the life course (Lee and Hicken, Reference Lee and Hicken2016). These findings underscore the need to better understand how and why SES and other social factors are linked with psychological distress among working-age African Americans. Collectively, the broad literature on the SES–psychological distress relationship, as well as the studies specific to African Americans, suggest:

Hypothesis 1: Among working-age African Americans, lower SES individuals will experience higher levels of depression/anxiety than their higher-SES peers.

Social Factors Mediating the SES–Psychological Distress Relationship among African Americans

It is also important to examine possible social factors that link SES with African Americans’ experiences of psychological distress. Stressful life events, particularly those that are “unscheduled, undesired, non-normative, and uncontrolled” are particularly harmful and can increase psychological distress (Pearlin Reference Pearlin1989, p. 244). African Americans disproportionately experience unique social stressors, such as traumatic events (e.g., deaths of young family members; sexual assault), which are linked with elevated risk of psychological distress (Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Davis and Andreski1995; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Hudson, Kershaw, Mezuk, Rafferty, Tuttle, Rogers and Crimmins2011; Louie and Wheaton, Reference Louie and Wheaton2019; Umberson Reference Umberson2017). African Americans who reside in low-resourced urban areas may experience heightened risk of trauma, in part, due to the limited housing options located in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Living in a disadvantaged neighborhood is associated with constant threats of victimization, heightened violent crime, and increased psychological stress (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Ross and Angel2005). African Americans residing in urban contexts are also at increased risk of transportation accidents, physical assault, and assault with a weapon (Alim et al., Reference Alim, Graves, Mellman, Aigbogun, Gray, Lawson and Charney2006). Stress from exposure to multiple traumatic events across the life course can accumulate, substantially increasing mental health risk (Turner and Lloyd, Reference Turner and Lloyd1995). As such, exposure to traumatic events is likely an important mediator of the SES–psychological distress relationship among African Americans.

Social factors, including access to social support through social networks and neighborhood contexts, may also help to explain the consequences of low SES for psychological distress. Social networks are an important flexible resource that link SES to health (Phelan and Link, Reference Phelan and Link2015), in part, because they are a key source of social support. Social support can include provision of tangible resources, helpful information, emotional sustenance, and assistance with active coping, and has been shown to reduce the negative mental health impacts of financial and discrimination-related stress (Ajrouch et al., Reference Ajrouch, Reisine, Lim, Sohn and Ismail2010; Thoits Reference Thoits1995, Reference Thoits2011). At the same time, social context constraints can limit the quality or effectiveness of available support (Pearlin Reference Pearlin1989), and a social network comprised of members with strained emotional, tangible, or financial resources may be less able to support members in need. Many African Americans are collectively-oriented, and connected to social networks comprised of both high-and low-resourced immediate and extended family members, friends, and neighbors who are critical sources of resource sharing and mutual support (Danziger and Lin, Reference Danziger and Lin2000; Stack Reference Stack1974). Networks share household labor and caregiving responsibilities, pool financial resources, and exchange time and personal attention across kith and kin (Burton and Whitfield, Reference Burton and Whitfield2003; Danziger and Lin, Reference Danziger and Lin2000). Furthermore, African Americans often feel a strong sense of mutual responsibility for others in their network and may feel a moral, emotional, or social cost to refusing support (Danziger and Lin, Reference Danziger and Lin2000). The importance of social support garnered through the social networks of African Americans may help to explain the SES and psychological distress relationship among this demographic group.

Social support gleaned from the community may also help to explain the relationship between SES and psychological distress. Neighborhood social cohesion—an indication of community residents’ shared common values and willingness to intervene for the common good—as well as social capital and collective efficacy, have been shown to protect the mental health of individuals who reside in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities (Fone et al., Reference Fone, Dunstan, Lloyd, Williams, Watkins and Palmer2007; Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls1997; Stafford et al., Reference Stafford, Mcmunn and Vogli2011). Residents of socially cohesive neighborhoods may benefit from higher quality friendships and a greater sense of personal control, which have been linked with reduced depressive symptoms (Stafford et al., Reference Stafford, Mcmunn and Vogli2011). Predominantly African American neighborhoods in urban contexts are often characterized by socioeconomic disadvantage and thought to have low social cohesion (Wilson Reference Wilson1997). However, prior scholarship also documents cases in which African Americans who live in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods report high levels of social cohesion in their communities as well as associated health benefits (Geronimus et al., Reference Geronimus, Pearson, Linnenbringer, Schulz, Reyes, Epel, Lin and Blackburn2015; Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Child, Moore, Moore and Kaczynski2016). Collectively, this literature suggests that the characteristics of the communities and social networks in which African Americans are embedded may help to explain the SES–psychological distress relationship among African Americans, suggesting the following:

Hypothesis 2a. Traumatic events will mediate the relationship between SES and depression/anxiety among working-age African Americans.

Hypothesis 2b. Psychosocial support and neighborhood social cohesion will mediate the association between SES and depression/anxiety among working-age African Americans.

Gender Differences in the SES–Psychological Distress Relationship

Scholars have consistently found strong evidence of gender differences in mental health, such that women are more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety than men (Rosenfield and Mouzon, Reference Rosenfield, Mouzon, Aneshensel, Phelan and Bierman2013). This gap is generally much smaller among African Americans (when compared with Whites) because African American women tend to report low rates of psychological distress (McGuire and Miranda, Reference McGuire and Miranda2008). Less is known, however, about how gender moderates the SES–psychological distress relationship among African Americans, and some evidence that considers intersections between SES and gender suggests that women may not always experience a mental health disadvantage when compared to men. For example, high SES may reduce the risk of psychological distress among African American women (Assari Reference Assari2017, Reference Assari2018; Assari and Caldwell, Reference Assari and Caldwell2017; Rosenfield and Mouzon, Reference Rosenfield, Mouzon, Aneshensel, Phelan and Bierman2013), while increasing the risk of psychological distress among African American men (Assari Reference Assari2017; Assari and Caldwell, Reference Assari and Caldwell2017; Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Neighbors, Geronimus and Jackson2012; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Takeuchi and Adair1992). These counterintuitive findings suggest a need to examine the modifying role of gender in the SES–psychological distress relationship among African Americans.

It is possible for gender to moderate the relationship between SES and psychological distress among African American men and women because gender differentially influences socioeconomic opportunities for African Americans; differential access to socioeconomic opportunities can yield different levels of stress with negative implications for mental health. For example, when compared with African American men, a greater proportion of African American women attain college and advanced degrees (National Center for Education Statistics 2018). Additionally, while unemployment rates are higher for African American men (Buffie Reference Buffie2015), African American women are penalized by a wage gap due to their race and gender and are more likely to experience workplace discrimination from both White and Black men (Hegewisch and Hartmann, Reference Hegewisch and Hartmann2019; Paul et al., Reference Paul, Zaw, Hamilton and Darity2018). However, it is also possible for gender to modify the social processes, such as stress and social support, that link socioeconomic circumstances to psychological distress among African Americans, resulting in gender differences in the SES–psychological distress relationship. For example, African American women and men experience different forms and magnitudes of structural socioeconomic and race-related stress due to their gender (Greer et al., Reference Greer, Laseter and Asiamah2009; Pearlin Reference Pearlin1989). African American men may experience increased psychosocial stress stemming from the desire to attain educational and economic success, and improve their social class status in the midst of blocked opportunities and discriminatory labor market realities (Griffith et al., Reference Griffith, Cornish, McKissic, Dean, Burton, Burton, McHale, King and Van Hook2016; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Leashore and Toliver1988). In contrast, African American women may experience increased stress from juggling multiple work and caregiving roles with limited resources and are also are more vulnerable to specific types of stressors, such as gender-based violence (Hamilton-Mason et al., Reference Hamilton-Mason, Hall and Everett2009). Gender also shapes African Americans’ responses to social stressors and their access to coping resources, such as social support (Pearlin Reference Pearlin1989). For example, African American men may cope with stressors by isolating themselves from others, internalizing their feelings, and working harder to address their problems at the expense of their health (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Griffith, Allen, Thorpe and Bruce2015; Griffith et al., Reference Griffith, Ellis and Allen2013; Griffith et al., Reference Griffith, Cornish, McKissic, Dean, Burton, Burton, McHale, King and Van Hook2016). In contrast, African American women are more likely to employ relational coping strategies, seeking instrumental or emotional support from others (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Phillips, Abdullah, Vinson and Robertson2011; Hamilton-Mason et al., Reference Hamilton-Mason, Hall and Everett2009). Collectively, prior literature suggests the need to further investigate possible gender differences in the magnitude and direction of the SES–psychological distress relationship, as well as the extent to which gender modifies the social factors that mediate the SES–psychological distress relationship among African Americans, suggesting the following:

Hypothesis 3a: Gender will moderate the SES–psychological distress relationship such that the association between low SES and increased depression/anxiety will be stronger among working-age African American women than men.

Hypothesis 3b: The extent to which traumatic events, psychosocial support, and neighborhood social cohesion mediate the association between SES and depression/anxiety will depend on the gender of working-age African Americans, such that these effects will be stronger among working-age African American women than men.

DATA AND METHODS

Study Setting

The City of Detroit provides an interesting context for studying the SES–psychological distress relationship among African Americans. Once one of the wealthiest cities in America, racial conflicts between 1941 and 1973 over access to jobs, housing, neighborhood segregation, school integration, policing, and control over city government catalyzed White flight to the city’s surrounding suburbs (Farley et al., Reference Farley, Danziger and Holzer2000). From the late 1950s to the 1980s, globalization, the OPEC oil crisis, and technological advancement drove widespread factory closures, and movement of many of the remaining factories to the suburbs. By 1990, Detroit was the most racially segregated city in America, and led the nation in unemployment, poverty, abandoned factories, and crime (Farley et al., Reference Farley, Danziger and Holzer2000). The Great Recession further crippled the city, as some of the few remaining employers disappeared when General Motors and Chrysler declared bankruptcy. African American residents in Detroit with the financial means to leave also fled to the surrounding suburbs or other cities (Seelye Reference Seelye2011). By 2010, Detroit was $300 million in debt. One-third of the city was physically abandoned, and the population of about 700,000 was less than forty percent of its peak of over 1.8 million in the 1950s (Seelye Reference Seelye2011). Detroit’s African American residents who experienced the city’s long economic decline and were left behind may have been especially vulnerable to the risk of psychological distress.

Data and Analytic Sample

The Detroit Neighborhood Health Study (DNHS) contains a prospective, population-representative sample of Detroit residents. These data capture socioeconomic variability among participants, include valid measures of psychological distress, and facilitate examination of the relationships between socioeconomic resources, social factors, and psychological distress among African Americans living in a post-industrial city during a serious economic downturn.

Although the DNHS was not designed to examine the impacts of the Great Recession, a unique feature of these data is that data collection coincided with its occurrence. Data from Wave I (2008–2009) capture the period during which the Great Recession was beginning to unfold, but Detroit residents had not yet felt the full impacts of the economic downturn. The data from Wave II (2009–2010) capture a period during which Detroit residents were more fully experiencing the impacts of the Great Recession. At Wave I, researchers recruited 1547 participants using a two-stage area probability sample of households within Detroit city limits. Interviewers obtained consent from each participant prior to beginning a forty-minute telephone survey, which asked participants about their demographics, health status, access to social support, and more. Substantial attrition occurred between Waves I and II, and researchers lost approximately one-third of their initial sample. Due to this attrition, researchers drew a supplemental sample of 534 individuals at Wave II from the same population using the same dual frame sampling technique that was administered in Wave I. Ancillary analyses (not shown) indicate there were no differences in gender, unemployment, homeownership, or income between those who dropped out of the DNHS between Waves I and II and those who remained. Those who left the study were approximately two years younger than those who remained and had higher educational attainment.

The study presented here uses data from Waves I and II of the DNHS, facilitating assessment of how SES, largely prior to the Great Recession, influenced the mental health status of working-age African Americans when Detroit residents were grappling with the recession’s impact. Non-African American respondents (N=243), those who were not working-age (N=393), and those who did not participate in both Waves I and II (N=211) were removed from the analytic sample. After treating missing data (discussed below), the results presented here reflect the responses of African Americans, ages 25–64, who provided valid data for depressive (N=685) and anxiety (N=681) symptoms.

Measures

Psychological Distress

Depression. I estimated a latent variable using nine items from the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) at Wave II to operationalize depression. The PHQ-9 is a validated instrument based on DSM-IV criteria. Respondents reported whether, in the last two weeks, they experienced any of nine symptoms, which include “feeling down,” “having trouble sleeping,” “feeling bad about oneself,” etc. (0=none of the time to 3=nearly every day) (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001).

Anxiety was operationalized through the estimation of a latent variable using seven items from the General Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7) at Wave II. The GAD-7 is a validated measure that assesses the frequency and severity of anxiety symptoms. Respondents reported whether in the last two weeks they, for example, “felt nervous or on edge,” “worried too much,” “had trouble relaxing,” etc. (0=not at all to 3=nearly every day) (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Janet and Löwe2006).

Socioeconomic Status

Educational attainment was assessed using a series of indicator variables for each level of education: less than high school (1=yes), high school degree (1=yes), some college (1=yes), college degree or higher (1=yes; REF). Midpoint coding was used to create a continuous measure of total household income in the previous year from all sources before taxes (range: $5,000–$80,000). Total household income was log transformed to reduce the positive skew of the variable’s distribution. Unemployment and homeownership are indicator variables (1=yes). All of the SES measures were assessed at Wave I.

Social Predictors

Traumatic events experienced in the last year were assessed at Wave II using a count of thirty items, which included “sexual assault,” “shot or stabbed,” “mugged or threatened with a weapon,” “witnessed a murder,” etc. (range: 0–30). Psychosocial support was measured with three items asking whether respondents’ friends or relatives “make them feel better when they are feeling down,” “provide good advice,” or “would lend money if they needed it” (0=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree). Items were summed, yielding a scale ranging from 0–12 in which higher scores indicated greater perceived psychosocial support. Neighborhood social cohesion was assessed with five items asking whether neighbors are “close-knit or unified,” “willingly help each other,” “get along,” “share the same values,” and “can be trusted” (0=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree) (Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls1997). Items were summed to construct a scale ranging from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating greater perception of neighborhood social cohesion.

Gender

This analysis incorporates an indicator for gender (0=man; 1=woman). The analyses for Aims 1 and 2 adjust for gender, and gender interaction terms are incorporated into the analyses for Aim 3.

Controls

This study utilized a continuous measure for age (range: 25–64 years), and an indicator for whether the respondent is the primary caregiver of a child under age 18 (hereafter: caregiver, 1=yes). The models for depression are adjusted for depressive symptoms at baseline by including a latent variable composed of nine items from the PHQ-9 at Wave I. Similarly, the models for anxiety control for participants’ baseline anxiety symptoms by including a latent variable composed of seven GAD-7 items assessed at Wave I.

Analytic Approach

Structural equation models (SEM) with latent variables were used to address each research aim: the association between multiple indicators of SES and psychological distress among working-age African Americans (Aim 1); the extent to which social factors mediate the SES–distress relationship (Aim 2); and whether gender modifies the relationships among SES, social factors, and psychological distress (Aim 3). A benefit of this approach is that SEM facilitates the simultaneous inclusion of multiple mediators as well as convenience, precision, and parsimony during estimation (Preacher and Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008).

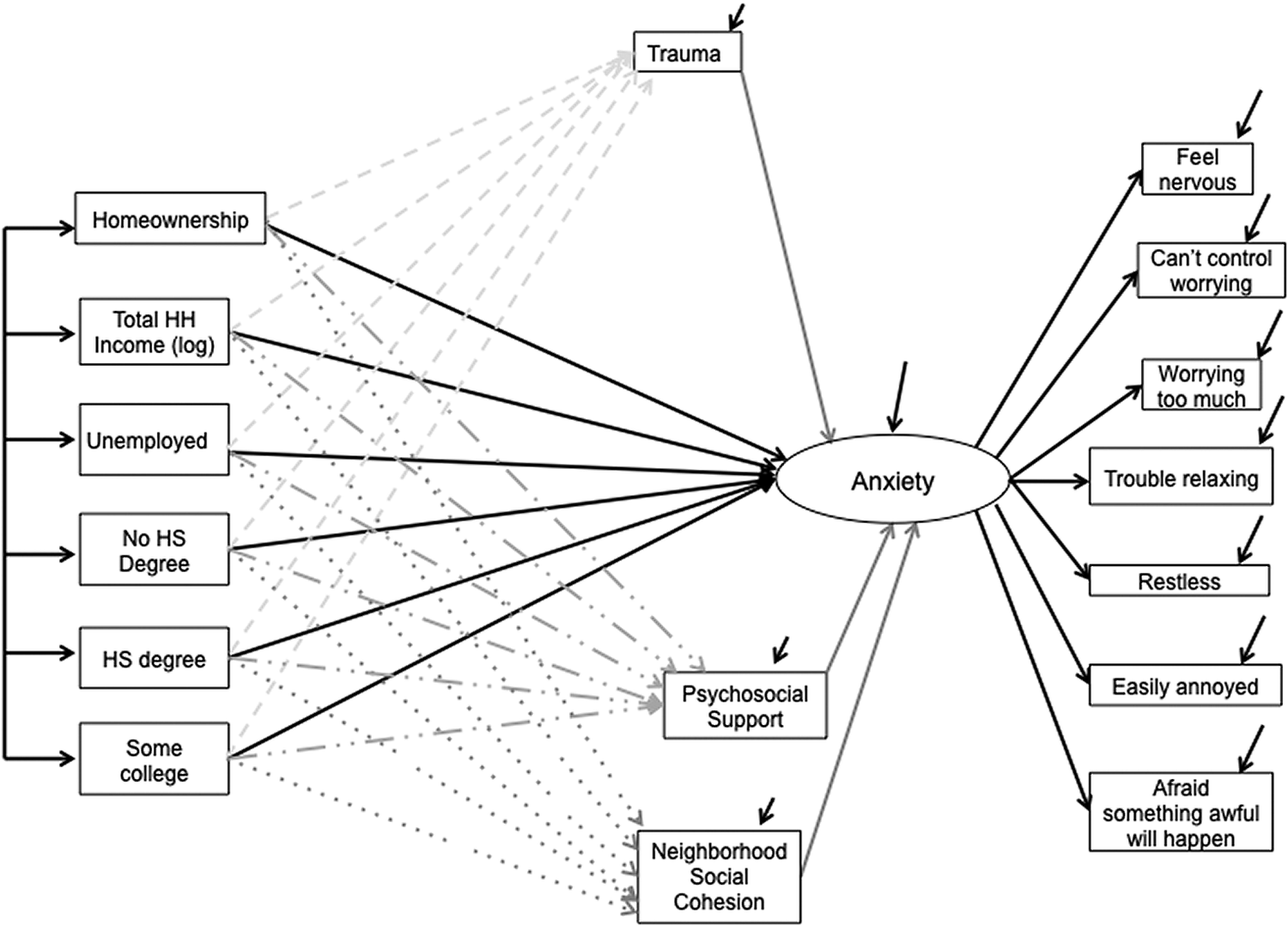

SEMs are composed of two components: a measurement portion and a structural portion. The measurement portion of the model links theoretically-derived, unobserved latent variable(s) with observed measures in a dataset that constitute their respective latent variable(s) (Bollen Reference Bollen1989). In this study, the measurement portions of the models are composed of the latent variables for depression/anxiety, and the indicators for the PHQ-9 / GAD-7, respectively. The errors of these indicators are not correlated with each other beyond their relationship with the latent variable, as indicated by the tiny free-hanging arrows pointing towards each PHQ-9 / GAD-7 item (Figures 1–6; Appendix, Figures A1–A4). Similarly, the error for the latent variables for depression/anxiety are uncorrelated with the errors of all other variables in each model. The factor loadings in the measurement models (Appendix, Figures A1–A4) represent the correlations between each observed indicator and the latent variable; they are akin to regression coefficients. For example, in Appendix Figure A1, the factor loading for item 1 of the PHQ-9 and the latent variable for psychological distress is

![]() $ \lambda $

= 0.89. The structural portions of the SEMs (Figures 1–6) represent the theorized relationships among the latent variable(s) for depression/anxiety and other endogenous or exogenous constructs in the model. In this study, exogenous socioeconomic indicators and endogenous social factors comprise the structural portion of the SEM. The coefficients in the structural portion of each SEM are partial regression coefficients that are interpreted as the degree of change in depression/anxiety per one-unit change in the independent variable when holding all other constructs in the model constant. The errors for all of the exogenous variables in each model are correlated with each other, as indicated by the long lines with several arrows. Conversely, the errors for the endogenous social factors in the model are uncorrelated with other variables in the model, as indicated by the tiny free-hanging arrows.

$ \lambda $

= 0.89. The structural portions of the SEMs (Figures 1–6) represent the theorized relationships among the latent variable(s) for depression/anxiety and other endogenous or exogenous constructs in the model. In this study, exogenous socioeconomic indicators and endogenous social factors comprise the structural portion of the SEM. The coefficients in the structural portion of each SEM are partial regression coefficients that are interpreted as the degree of change in depression/anxiety per one-unit change in the independent variable when holding all other constructs in the model constant. The errors for all of the exogenous variables in each model are correlated with each other, as indicated by the long lines with several arrows. Conversely, the errors for the endogenous social factors in the model are uncorrelated with other variables in the model, as indicated by the tiny free-hanging arrows.

Fig. 1. Theoretical Model of the Socioeconomic Predictors of Depression among African American Respondents in the Detroit Neighborhood Health Study

Estimation unfolded in two steps (Anderson and Gerbing, Reference Anderson and Gerbing1988). The first step entailed conducting confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to establish the best-fitting relationship between the observed PHQ-9 and GAD-7 items and their underlying latent construct(s) (Bollen Reference Bollen1989). The CFA results (see Appendix) indicated that modeling the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 items as two separate latent variables for depression and anxiety best fit the underlying structure of the DNHS data (Appendix Figure A4). The research hypotheses were tested in the second step by simultaneously estimating the measurement and structural portions of six SEMs. Diagonally weighted least squares regression (DWLS) was used for model estimation, which relies on polychoric/polyserial correlations, and provides more accurate parameter estimates and a more robust model fit than maximum likelihood estimation when categorical indicators are used to measure a continuous underlying latent variable (Mîndrilă Reference Mîndrilă2010).

More specifically, the first hypothesis asserts that lower SES will be strongly associated with depression and anxiety. Hypothesis testing involved estimating two SEMs in which several exogenous socioeconomic indicators were associated with an endogenous latent variable for depression (Figure 1)/anxiety (Figure 2). Evidence in support of this hypothesis would entail the following: a significant negative association between homeownership or total household income and depression/anxiety, a significant positive association between unemployment and depression/anxiety, or a significant positive relationship between lower-levels of educational attainment and depression/anxiety.

Fig. 2. Theoretical Model of the Socioeconomic Predictors of Anxiety among African American Respondents in the Detroit Neighborhood Health Study

To evaluate the second Aim, I tested the hypothesis that traumatic events, psychosocial support, and/or neighborhood social cohesion mediate the association between SES and depression/anxiety among working-age African Americans. The test for this hypothesis involved estimating the models depicted in Figures 3 and 4, and then decomposing the direct, indirect, and total effects of the socioeconomic and social variables on latent depression/anxiety. A direct effect captures the unmediated influence of one variable on another variable, whereas the indirect effect is the effect of one variable on another variable that is conveyed through at least one additional variable. A total effect is the sum of the direct effect(s) and the indirect effect(s) (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Lynch and Chen2010). Significant indirect effects provide support for whether mediation is occurring, and if so, identifies the mediator through which mediation occurs. Bootstrapping (with 2000 replications) was used to re-estimate the indirect effects, and the 95% confidence intervals around the indirect effects were examined to identify intervals that excluded 0 (Bollen and Stine, Reference Bollen and Stine1990). When assessing mediation, bootstrapping is preferred over the product-of-coefficients strategy because it has higher statistical power to detect indirect effects and does not assume that the sampling distribution of the indirect effect is symmetric or normal (Preacher and Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008).

Fig. 3. Theoretical Multiple Mediation Model for the Relationship between Socioeconomic Predictors of Depression among African American Respondents in the Detroit Neighborhood Health Study

Fig. 4. Theoretical Multiple Mediation Model for the Relationship between Socioeconomic Predictors of Anxiety among African American Respondents in the Detroit Neighborhood Health Study

To address Aim 3, first, I tested the equivalence of the models depicted in Figures 1 and 2 among women and men to test the hypothesis that gender moderated the SES–depression/anxiety relationship. Second, I tested the hypothesis that gender moderates the mediating effect of traumatic events, psychosocial support, and/or neighborhood social cohesion on the SES–depression (Figure 5)/anxiety (Figure 6) relationship, such that these relationships will be stronger among women than men. This entailed re-estimating the SEM from Aim 2, with the addition of an interaction term for gender on any indirect effects found to be significant in Aim 2. The interaction term facilitates a test of conditional effect(s), which exists when the strength of an indirect effect varies based on the value of a moderator (Preacher et al., Reference Preacher, Rucker and Hayes2007). Bootstrapping (with 2000 replications) was utilized to estimate the indirect effects at different levels of the moderator, and the 95% confidence intervals around the indirect effects were examined for intervals that excluded 0 (Preacher et al., Reference Preacher, Rucker and Hayes2007). Significant conditional effects provide support for the third hypothesis.

Fig. 5. Theoretical Conditional Effects of Gender Model on the Socioeconomic Predictors of Depression among African American Respondents in the Detroit Neighborhood Health Study

Fig. 6. Theoretical Conditional Effects of Gender Model on the Socioeconomic Predictors of Anxiety among African American Respondents in the Detroit Neighborhood Health Study

For each SEM, the following measures of overall fitness are reported: Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), the Relative Noncentrality Index (RNI), 1-Root Mean Square Error (1-RMSEA), and the BIC. For the TLI, RNI, and 1-RMSEA, a value of 1 represents an ideal fit, a value of 0.95 represents a good fit, and values below 0.90 indicate questionable fit (Hu and Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). Negative BIC values represent the best overall fit while positive values are indicative of poor fit (Raftery Reference Raftery1995).

Up to 26% of data were missing across the socioeconomic and social variables included in this study. Missingness in the structural portion of the models was addressed using multiple imputations by chained equations (MICE) (Allison Reference Allison2003). For each SEM, the fit indices and path coefficients in the models were averaged across ten datasets. The standard errors of the coefficients were averaged using Rubin’s rules, which combine the estimated variability within and across replications while correcting for variance (Rubin Reference Rubin1987). None of the analyses are weighted because the DNHS sample weights were constructed solely from independent variables included in this analysis and, if applied, would yield biased estimates and larger standard errors (Winship and Radbill, Reference Winship and Radbill1994). All analyses were conducted using the R package “lavaan.” The SEMs for Aims 1 and 2 were adjusted for age, gender, and caregiver status, and the SEMs for Aim 3 were adjusted for age and caregiver status.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows a summary of the observed variables in the SEMs. African American respondents reported that the most frequent and/or severe depressive symptoms experienced in the last two weeks were trouble sleeping (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.72) and feeling tired (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.72) and feeling tired (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.81). In contrast, respondents were least bothered by feelings of sluggishness or fidgetiness (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.81). In contrast, respondents were least bothered by feelings of sluggishness or fidgetiness (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.17) and suicidal thoughts (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.17) and suicidal thoughts (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.09). Regarding anxiety symptoms, respondents reported that worrying too much (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.09). Regarding anxiety symptoms, respondents reported that worrying too much (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.62) and trouble relaxing (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.62) and trouble relaxing (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.57) were most frequent and/or severe, whereas restlessness (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.57) were most frequent and/or severe, whereas restlessness (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.24) and fearing something awful will happen (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.24) and fearing something awful will happen (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.29) were the least bothersome. The majority of respondents completed some college (38.7%) or high school (21.7%), while about 22% of respondents had attained a college degree, and almost 18% of respondents did not complete high school. While 40% of respondents reported homeownership, average total household income was about $34,000, and about 19% of respondents were unemployed. Collectively, these figures illustrate the socioeconomic disadvantages experienced by working-age African American adults in twenty-first century Detroit. While respondents reported exposure to approximately three traumatic events in the last year, they also reported high levels of psychosocial support (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.29) were the least bothersome. The majority of respondents completed some college (38.7%) or high school (21.7%), while about 22% of respondents had attained a college degree, and almost 18% of respondents did not complete high school. While 40% of respondents reported homeownership, average total household income was about $34,000, and about 19% of respondents were unemployed. Collectively, these figures illustrate the socioeconomic disadvantages experienced by working-age African American adults in twenty-first century Detroit. While respondents reported exposure to approximately three traumatic events in the last year, they also reported high levels of psychosocial support (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=10.3) and neighborhood social cohesion (

$ \overline{x} $

=10.3) and neighborhood social cohesion (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=12.4). A majority of respondents were women (58.9%) and the average age was forty-eight years. Approximately 36% were primary caregivers of children ages eighteen or younger.

$ \overline{x} $

=12.4). A majority of respondents were women (58.9%) and the average age was forty-eight years. Approximately 36% were primary caregivers of children ages eighteen or younger.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of the Manifest Mental Health, Psychosocial, and Demographic Characteristics of African American Respondents

Source: Detroit Neighborhood Health Study. Traumatic events is a count variable with higher numbers referring to more traumatic events in the last year. Psychosocial support is a scale with higher scores indicating greater perceived support.

Neighborhood social cohesion is a scale with higher scores indicating greater perceptions of neighborhood social cohesion. The natural log of total household income was used in the analyses for Aims 1-3. Chi-Square and Independent Means T-Tests were used to assess gender differences.

There were also a few gender differences in the sample. When reporting depressive symptoms, feeling depressed (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.63 v.

$ \overline{x} $

=0.63 v.

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.45), trouble sleeping (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.45), trouble sleeping (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.81 v.

$ \overline{x} $

=0.81 v.

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.58), feeling tired (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.58), feeling tired (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=1.01 v.

$ \overline{x} $

=1.01 v.

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.54), poor appetite/overeating (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.54), poor appetite/overeating (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.69 v.

$ \overline{x} $

=0.69 v.

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.36) and trouble concentrating (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.36) and trouble concentrating (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.35 v.

$ \overline{x} $

=0.35 v.

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.22) were more severe and/or frequent for women than men. Moreover, when reporting the severity and frequency of anxiety symptoms, more women than men were bothered by the inability to control worrying (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.22) were more severe and/or frequent for women than men. Moreover, when reporting the severity and frequency of anxiety symptoms, more women than men were bothered by the inability to control worrying (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.51 v.

$ \overline{x} $

=0.51 v.

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.36), worrying too much (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.36), worrying too much (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.71 v.

$ \overline{x} $

=0.71 v.

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.49), and trouble relaxing (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.49), and trouble relaxing (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.65 v.

$ \overline{x} $

=0.65 v.

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=0.45). Women also reported more severe and more bothersome depressive and anxiety symptoms at baseline than men. Average total household income was higher for men than women (

$ \overline{x} $

=0.45). Women also reported more severe and more bothersome depressive and anxiety symptoms at baseline than men. Average total household income was higher for men than women (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=$37,776 v.

$ \overline{x} $

=$37,776 v.

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=$31,375). On average, women were also slightly older than men (

$ \overline{x} $

=$31,375). On average, women were also slightly older than men (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=49 v.

$ \overline{x} $

=49 v.

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=47), and more women were primary caregivers than men (

$ \overline{x} $

=47), and more women were primary caregivers than men (

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=40% v.

$ \overline{x} $

=40% v.

![]() $ \overline{x} $

=31%).

$ \overline{x} $

=31%).

Aim 1. Socioeconomic Predictors of Depression and Anxiety

The models in Figures 1 and 2 depict the association between multiple dimensions of SES in the wake of the Great Recession in 2008 and depression/anxiety among working-age African Americans, respectively, the next year. Results from testing whether lower SES was strongly associated with depression/anxiety can be found in Table 2. Two dimensions of SES were associated with depression a year later, net of other coefficients in the model. First, a one-unit increase in the log of total household income was associated with a reduction in depression (

![]() $ \beta $

=-0.12, p<0.05). Therefore, a person whose household income rose from $20,000 to $40,000 experienced a 0.08-unit reduction in depressive symptoms. Second, unemployment was associated with increased depression (

$ \beta $

=-0.12, p<0.05). Therefore, a person whose household income rose from $20,000 to $40,000 experienced a 0.08-unit reduction in depressive symptoms. Second, unemployment was associated with increased depression (

![]() $ \beta $

=0.21, p<0.05). There were no associations between educational attainment and depression or homeownership and depression. This model fit the underlying data structure well, as the BIC was negative, and the RNI, TLI, and 1-RMSEA were all greater than 0.90 (Hu and Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999).

$ \beta $

=0.21, p<0.05). There were no associations between educational attainment and depression or homeownership and depression. This model fit the underlying data structure well, as the BIC was negative, and the RNI, TLI, and 1-RMSEA were all greater than 0.90 (Hu and Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999).

Table 2. SEM Parameter Estimates and Overall Fit Statistics of the Socioeconomic Predictors of Depression and Anxiety among African American Respondents

Source: Detroit Neighborhood Health Study; both models adjust for age, sex, and caregiver status. The model for depression is adjusted for depressive symptoms at Wave I, and the model for anxiety is adjusted for anxiety symptoms at Wave I. *p < 0.05, ** p< 0.01, *** p< 0.001; The estimates for depression are derived from Figure 1, and the estimates for Anxiety are derived from Figure 2.

Holding other coefficients in the model constant, the results for anxiety were similar to those for depression. Again, a one-unit increase in the log of total household income was associated with reduced anxiety (

![]() $ \beta $

=-0.09, p<0.05) such that an individual whose household income rose from $20,000 to $40,000 experienced a 0.06-unit reduction in anxiety symptoms. Unemployment, in contrast, was associated with increased anxiety (

$ \beta $

=-0.09, p<0.05) such that an individual whose household income rose from $20,000 to $40,000 experienced a 0.06-unit reduction in anxiety symptoms. Unemployment, in contrast, was associated with increased anxiety (

![]() $ \beta $

=0.28, p<0.01). In addition, when compared with those who completed a bachelor’s degree or higher, having attained a high school degree was associated with increased anxiety (

$ \beta $

=0.28, p<0.01). In addition, when compared with those who completed a bachelor’s degree or higher, having attained a high school degree was associated with increased anxiety (

![]() $ \beta $

=0.24, p<0.05). Here, the overall fit statistics (i.e., TLI, RNI, 1-RMSEA, BIC) are all greater than 0.90, indicating a good model fit. Collectively, these results support the first hypothesis, as significant positive associations were found between unemployment and depression/anxiety and educational attainment and anxiety, whereas a significant negative association was found between total household income and depression/anxiety. The null association between homeownership and psychological distress, however, does not support this hypothesis.

$ \beta $

=0.24, p<0.05). Here, the overall fit statistics (i.e., TLI, RNI, 1-RMSEA, BIC) are all greater than 0.90, indicating a good model fit. Collectively, these results support the first hypothesis, as significant positive associations were found between unemployment and depression/anxiety and educational attainment and anxiety, whereas a significant negative association was found between total household income and depression/anxiety. The null association between homeownership and psychological distress, however, does not support this hypothesis.

Aim 2. Social Factors Mediating the SES–Depression/Anxiety Relationship

Next, the hypothesis that social factors will significantly mediate the association between SES and depression (Figure 3)/anxiety (Figure 4) among working-age African Americans was tested by adding mediators for traumatic events, psychosocial support, and neighborhood social cohesion to the SEMs examined in Aim 1. The total, indirect, and direct effects of the relationships between SES, social factors, and depression/anxiety are presented in Table 3, where significant indirect effects indicate mediation.

Table 3. Summary of Total, Indirect, and Direct Effects of Socioeconomic Predictors of Poor Mental Health among African American Respondents

Source: Detroit Neighborhood Health Study; both models adjust for age, sex, and caregiver status. The model for depression is adjusted for depressive symptoms at Wave I, and the model for anxiety is adjusted for anxiety symptoms at Wave I. Estimates for depression are derived from the model depicted in Figure 3. Estimates for anxiety are derived from the model depicted in Figure 4.

Trauma seemed to mediate the relationship between SES and depression. Specifically, while the total effect of unemployment remained significantly associated with increased depression (

![]() $ \beta $

=0.25) net of the other model coefficients, unemployment indirectly influenced depression through traumatic events, accounting for 80% of the total effect. In contrast, the total effect of total household income remained significant when holding the other model coefficients constant such that each one-unit increase in the log of household income was associated with reduced depression (

$ \beta $

=0.25) net of the other model coefficients, unemployment indirectly influenced depression through traumatic events, accounting for 80% of the total effect. In contrast, the total effect of total household income remained significant when holding the other model coefficients constant such that each one-unit increase in the log of household income was associated with reduced depression (

![]() $ \beta $

=-0.10). As such, a rise in income from $15,000 to $30,000 would result in a 0.07-unit reduction in depression. None of the theorized social factors, however, mediated this relationship. In addition, the total, direct, and indirect effects between homeownership and depression, as well as educational attainment and depression, were all insignificant. The TLI, RNI, 1-RMSEA, and BIC statistics indicated a strong overall fit of the underlying data structure.

$ \beta $

=-0.10). As such, a rise in income from $15,000 to $30,000 would result in a 0.07-unit reduction in depression. None of the theorized social factors, however, mediated this relationship. In addition, the total, direct, and indirect effects between homeownership and depression, as well as educational attainment and depression, were all insignificant. The TLI, RNI, 1-RMSEA, and BIC statistics indicated a strong overall fit of the underlying data structure.

Similar to the results for depression, when holding the other model coefficients constant, the total effect of unemployment remained associated with increased anxiety (

![]() $ \beta $

=0.32), and the indirect effect of unemployment on anxiety through traumatic events accounted for 72% of the total effect. Furthermore, when compared with those who attained a college degree or higher, the total effects of those who did not attain a high school degree (

$ \beta $

=0.32), and the indirect effect of unemployment on anxiety through traumatic events accounted for 72% of the total effect. Furthermore, when compared with those who attained a college degree or higher, the total effects of those who did not attain a high school degree (

![]() $ \beta $

=0.28), those who did attain a high school degree (

$ \beta $

=0.28), those who did attain a high school degree (

![]() $ \beta $

=0.25), and those who completed some college (

$ \beta $

=0.25), and those who completed some college (

![]() $ \beta $

=0.17) were all associated with increased anxiety when holding the other coefficients in the model constant. While none of the proposed mediators were significant among those who did not complete high school and those who attained a high school degree, the indirect effect of some college on anxiety through trauma was significant, accounting for 53% of the total effect. The total, direct, and indirect associations between homeownership and anxiety and total household income and anxiety, however, were not significant. Again, the overall fit statistics indicate a strong fit of the underlying data structure. Collectively, these results provide support for the hypothesis that a social factor—trauma—may mediate the relationship between unemployment and depression/anxiety. In addition, these results provide support for the hypothesis that trauma may mediate the relationship between having completed some college and anxiety. The insignificant indirect effects of other socioeconomic indicators on depression/anxiety through psychosocial support and neighborhood social cohesion, however, do not lend support to this hypothesis.

$ \beta $

=0.17) were all associated with increased anxiety when holding the other coefficients in the model constant. While none of the proposed mediators were significant among those who did not complete high school and those who attained a high school degree, the indirect effect of some college on anxiety through trauma was significant, accounting for 53% of the total effect. The total, direct, and indirect associations between homeownership and anxiety and total household income and anxiety, however, were not significant. Again, the overall fit statistics indicate a strong fit of the underlying data structure. Collectively, these results provide support for the hypothesis that a social factor—trauma—may mediate the relationship between unemployment and depression/anxiety. In addition, these results provide support for the hypothesis that trauma may mediate the relationship between having completed some college and anxiety. The insignificant indirect effects of other socioeconomic indicators on depression/anxiety through psychosocial support and neighborhood social cohesion, however, do not lend support to this hypothesis.

Aim 3. The Conditional Effects of Gender on the SES–Depression/Anxiety Relationship

Testing whether the models depicted in Figures 1 and 2 are equivalent among men and women facilitated a test of the hypothesis that gender moderated the SES–psychological distress relationship. Results (Table 4) indicate a gender difference in the unemployment–depression/anxiety relationship such that among women, net of the other model coefficients, unemployment was associated with increased depression (

![]() $ \beta $

=0.32, p<0.05) and anxiety (

$ \beta $

=0.32, p<0.05) and anxiety (

![]() $ \beta $

=0.44, p<0.01). In addition, a one-unit increase in the log of total household income was associated with reductions in depression (

$ \beta $

=0.44, p<0.01). In addition, a one-unit increase in the log of total household income was associated with reductions in depression (

![]() $ \beta $

=-0.13, p<0.05) and anxiety (

$ \beta $

=-0.13, p<0.05) and anxiety (

![]() $ \beta $

=-0.12, p<0.05) among women. This means that a woman whose household income rose from $20,000 to $40,000 experienced a 0.09-unit reduction in depressive symptoms and a 0.08-unit reduction in anxiety symptoms. In contrast, the relationships between unemployment and depression/anxiety, and total household income and depression/anxiety, were not significant among men. Finally, when compared to men and women who attained a college degree or higher, not attaining a high school degree (

$ \beta $

=-0.12, p<0.05) among women. This means that a woman whose household income rose from $20,000 to $40,000 experienced a 0.09-unit reduction in depressive symptoms and a 0.08-unit reduction in anxiety symptoms. In contrast, the relationships between unemployment and depression/anxiety, and total household income and depression/anxiety, were not significant among men. Finally, when compared to men and women who attained a college degree or higher, not attaining a high school degree (

![]() $ \beta $

=0.40, p<0.05) was associated with increased anxiety among men, whereas having attained some college (

$ \beta $

=0.40, p<0.05) was associated with increased anxiety among men, whereas having attained some college (

![]() $ \beta $

=0.09, p<0.05) was associated with increased anxiety among women when holding the other coefficients in the model constant. Among both women and men, however, homeownership was not significantly associated with depression/anxiety. These models are good overall fits of the underlying data structure. The results for unemployment and total household income support the hypothesis that gender may moderate the relationship between SES and depression/anxiety such that the relationship is stronger among women.

$ \beta $

=0.09, p<0.05) was associated with increased anxiety among women when holding the other coefficients in the model constant. Among both women and men, however, homeownership was not significantly associated with depression/anxiety. These models are good overall fits of the underlying data structure. The results for unemployment and total household income support the hypothesis that gender may moderate the relationship between SES and depression/anxiety such that the relationship is stronger among women.

Table 4. SEM Parameter Estimates and Overall Fit Statistics of Sex Differences in the Socioeconomic Predictors of Depression and Anxiety among African American Respondents

Now, recall that the results from Aim 2 revealed significant indirect effects of unemployment on depression/anxiety through trauma, as well as a significant indirect effect of some college on anxiety through trauma. Here, the dependence of these significant indirect effects on the gender of working-age African Americans is examined. To test the hypothesis that the indirect effects would be stronger among women than men, gender interaction terms were added to the indirect effects found to be significant in Aim 2 (Figures 5 and 6) with an eye towards identifying significant conditional effects. A significant conditional effect indicates moderated mediation, meaning that the strength or direction of the indirect effects identified in Aim 2 vary based on gender. Table 5 shows the results from these analyses.

Table 5. Summary of Conditional Gender Effects of Socioeconomic Predictors of Poor Mental Health among African American Respondents

Source: Detroit Neighborhood Health Study; both models adjust for age and caregiver status. The model for depression is adjusted for depressive symptoms at Wave I, and the model for anxiety is adjusted for anxiety symptoms at Wave I. Estimates for depression are derived from the model depicted in Figure 5. Estimates for anxiety are derived from the model depicted in Figure 6. Beta coefficients are standardized.

Findings suggest that gender may moderate the indirect effects of unemployment on depression/anxiety through trauma such that the associations are stronger among women than men. Specifically, among women, the indirect effect of unemployment, operating through traumatic events, was associated with a 0.25-unit increase in depression. Among men, however, the magnitude of the effect was smaller (

![]() $ \beta $

=0.19). Similarly, the indirect effect of unemployment on anxiety through trauma was stronger for women

$ \beta $

=0.19). Similarly, the indirect effect of unemployment on anxiety through trauma was stronger for women

![]() $ \left(\beta =0.30\right) $

than for men

$ \left(\beta =0.30\right) $

than for men

![]() $ \left(\beta =0.20\right) $

. The TLI, RNI, 1-RMSEA, and BIC indicate a good overall fit. These results provide support for the hypothesis that the mediating effect of trauma on the relationship between unemployment and depression/anxiety depends on gender, such that the effect is stronger among women than men. The results for some college, however, do not provide support for this hypothesis, indicating that the indirect effect of some college on anxiety via trauma is comparable for women and men.

$ \left(\beta =0.20\right) $

. The TLI, RNI, 1-RMSEA, and BIC indicate a good overall fit. These results provide support for the hypothesis that the mediating effect of trauma on the relationship between unemployment and depression/anxiety depends on gender, such that the effect is stronger among women than men. The results for some college, however, do not provide support for this hypothesis, indicating that the indirect effect of some college on anxiety via trauma is comparable for women and men.

DISCUSSION

This study examined associations between multiple dimensions of SES and two measures of psychological distress among working-age African Americans living in Detroit in the wake of the Great Recession. In addition, the mediating roles of trauma, psychosocial support, and neighborhood social cohesion, as well as the moderating role of gender, were tested to explain the SES–psychological distress relationship in this population. Findings from the first study aim revealed that total household income was associated with reduced depression/anxiety. In contrast, unemployment was associated with increased depression/anxiety. Moreover, when compared to those who attained a college degree or more, attainment of a high school degree was associated with increased anxiety. Results from the second aim revealed that trauma mediated the relationship between unemployment and increased depression/anxiety, as well as the relationship between having completed some college (in comparison to having attained a bachelor’s degree or higher) and increased anxiety. The results from the third aim revealed that the relationships between unemployment and depression/anxiety and total household income and depression/anxiety, as well as the meditational effect of trauma on the unemployment–depression/anxiety relationship, were moderated by gender, such that these effects were stronger among working-age African American women.

The findings from Aim 1 are consistent with prior scholarship of the SES–psychological distress relationship among African American adults that found an association between increased income (Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Hooyman, Hill and Rue2013; Mouzon et al., Reference Mouzon, Taylor, Nguyen and Chatters2016) and reduced depressive symptoms/risk of depression, as well as prior findings of an association between unemployment (Gavin et al., Reference Gavin, Walton, Chae, Alegria, Jackson and Takeuchi2010; Williams et al., Reference Williams, González, Neighbors, Nesse, Abelson, Sweetman and Jackson2007) and increased depressive symptoms/risk of depression. The results presented here advance the literature by extending these patterns to anxiety, and by also demonstrating an association between educational attainment and reduced risk of anxiety among African American adults. Collectively, these findings underscore the importance of including multiple indicators of SES in studies examining the SES–psychological distress relationship, as each measure of SES captures a unique aspect of this relationship (Braveman et al., Reference Braveman, Cubbin, Egerter, Chideya, Marchi, Metzler and Posner2005), and the associations may vary based on choice of socioeconomic indicator and the mental health outcome under study. In addition, these findings highlight the usefulness of incorporating a measure of employment status as a component of SES in future SES–psychological distress studies, particularly when studying historically marginalized populations or contexts in which a substantial proportion of the population is disconnected from the labor force, such as post-industrial cities or during recessions (Braveman et al., Reference Braveman, Cubbin, Egerter, Chideya, Marchi, Metzler and Posner2005; Galobardes et al., Reference Galobardes, Shaw, Lawlor and Lynch2006).