INTRODUCTION

Two indicators of race relations in the United States are interracial marriage and transracial adoption (Root Reference Root2001; Simon and Altstein, Reference Simon and Altstein2000). The rising prevalence of both phenomena suggests to some that barriers between racial groups have eroded in recent decades; however, others have challenged this optimistic interpretation, noting it is the continuing significance of racism, anchored in historically rooted beliefs about racial groups, that surrounds and even motivates these interracial crossings (Collins Reference Collins2004; Dalmage Reference Dalmage2000). These discourses inform individuals' attitudes toward racial and ethnic groups and thus potentially influence individuals' behavior, in this case, their engagement in social intimacy across racial lines (Bobo and Tuan, Reference Bobo and Tuan2006).

In this article, we examine the salience of race in the romantic involvements of Korean adoptees who were raised in White families, and we empirically specify the role of racial discourses in influencing romantic involvements. We view romantic involvements as an inclusive classification of the range of activities associated with dating, from casual interest to courtship, including marital and nonmarital unions—rather than as a measure of their “romantic” intensity. While scholars have closely examined interracial marriage, they have not paid equal attention to interracial dating, despite its important role as a precursor to interracial marriage (Joyner and Kao, Reference Joyner and Kao2005; Kalmijn Reference Kalmijn1998). Interracial marriage has been a legalized type of union since the 1960s (Rosenfeld and Kim, Reference Rosenfeld and Kim2005; Spickard Reference Spickard1989; Williams-León and Nakashima, Reference Williams-León and Nakashima2001); however, interracial romance and sexuality retain an air of mystery and taboo, as evidenced in both popular culture and subgenres of pornography (Childs Reference Childs2005). Our central argument is that racialized assumptions and beliefs, what we refer to as racial discourses, are salient for romantic involvements in ways that are independent of variations in personal dating experience and even in the structural location of those experiences.

Scholarship on race and ethnicity argues that racial discourses play a central role in race relations. Racial formation theory pioneers Michael Omi and Howard Winant (Reference Omi and Winant1994) posit a Gramscian conception of race as a cultural construct, anchored in political processes and reproduced at every level in society. Because the field of racial discourses in mainstream culture constitutes a dominant racial culture that rationalizes state policies and influences the common sense about race, racial and ethnic groups, social movements, and organizations all vie to rearticulate racial discourses. Also drawing on the ideas of Antonio Gramsci, feminist theorists identify the salience of race in the cultural division of masculinities into hegemonic and subordinated forms (Chen Reference Chen1999; Connell Reference Connell1987, Reference Connell2005; Pyke and Johnson, Reference Pyke and Johnson2003). In these theoretical accounts, however, racial culture defines individual identity, standpoint, and scope of action to a nearly Foucauldian degree that is at odds with the extent of variation evident in the quantitative literature on interracial marriage. We define racial culture as “the totality of racial attitudes, assumptions, and beliefs within the national mainstream culture,” and we define racial discourses as the discrete themes within this aggregate. In this article, we examine the extent to which racial culture is empirically salient in the narratives of Korean adoptees about their romantic involvements.

Korean adoptees are a useful case for exploring and empirically specifying the salience of race in romance. As Asian Americans raised in White families, they occupy a paradoxical social position: “Adoptees are racial/ethnic minorities in society, but they are perceived and treated by others, and sometimes themselves, as if they are members of the majority culture (i.e., racially White and ethnically European)” (Lee Reference Lee2003, p. 711). Raised by White parents, Korean adoptees confront mainstream culture without the cultural socialization of their nonadopted Korean American peers. This distinction is important because the research on Asian American intermarriage has found that an aversion to coethnic families is a strong motivation for outmarriage. Although these studies attribute this aversion to the mainstream stereotype of Asians as rigidly traditional, more sexist, and less nurturing (Chow Reference Chow2000; Fong and Yung, 1995–Reference Fong and Yung1996; Lee Reference Lee, Lee and Zhou2004; Qian Reference Qian2005), some of their respondents also invoke specific family dynamics, including abusive fathers, parents in unhappy marriages, and even encouragement from mothers to daughters to avoid sexism by seeking noncoethnic or even non-Asian husbands. In effect, dysfunctional family dynamics are defined as ethnic or racial in nature, rather than being simply regarded as characteristic of individual families. Unlike most members of the new second generation (Portes Reference Portes1996), Asian adoptees provide an opportunity to confirm the influence of mainstream stereotypes in the absence of coethnic family experience. Our central question, therefore, is whether racial culture has an independent influence on romance beyond serving more neutrally as a language for interethnic comparisons.

Korean adoptees are interesting to observers of race relations for other reasons as well. Historically, adoptions from South Korea started during the 1950s, prior to both the liberalization of U.S. immigration policy and the elimination of antimiscegenation laws. While China currently accounts for the majority of Asian adoptees coming annually to the United States (Tessler et al., Reference Tessler, Gamache and Liu1999), South Korea alone accounts for 34.8% of all children ever adopted from abroad (Shiao et al., Reference Shiao, Tuan and Rienzi2004). Positioned right on top of the juncture made by post-1965 immigration and historic racial and ethnic relations, Korean adoption provides an important case for researching important questions about the social differences that divide Americans and the prospects for their declining salience. When White Americans adopt children from South Korea, they create families that transgress racial, ethnic, and national boundaries. We examine the extent to which their Asian children continue these intimate social crossings in their own adult lives through the lens of dating and romance. Like the intermarriage patterns of mixed-ancestry persons (Lieberson and Waters, Reference Lieberson and Waters1988), the romantic involvements of transracial adoptees are an indicator of ongoing race relations and thus provide a window on their future direction.

To study the salience of race in romance, we devised a dating-history approach to analyzing life history interviews with our sample of fifty-eight adult Korean adoptees, focusing on their romantic preferences in the context of both their dating experiences and the structural conditions particular to their individual lives. We operationalized racial culture as the characterizations of racial and ethnic groups that adoptees voice to explain bias in their partner preferences or expectations, and we identified core themes from individuals who lack any history of romantic contact with the group in question. In this study, we primarily found discourses characterizing Asians and Whites and identified their major themes from our interviews with adoptees who have never dated another Asian. Subsequently, we compared these subjects with the adoptees who have had romantic contact with other Asians and examined their narratives for similarities and differences, attributing the similarities to the influence of racial culture and the differences to the effects of personal contact. We also assessed the extent to which structural conditions shaped the likelihood of interracial intimacy and thereby the scope of racial salience.

Using the case of Korean adoptees, we demonstrate that racial culture influences romantic preferences by shaping adoptees' interpretations of their romantic involvements across a range of structural conditions, and we identify some conditions that limit its salience. First, we explain our dating-history approach through a review of the literature on Asian American romance and intermarriage. Then we outline the combination of quantitative and qualitative methods we employed to implement our dating-history approach. We then examine our adoptee sample for the structural conditions shaping their dating histories and for the salience of race in their narratives on romantic involvements. We conclude by suggesting a conception of romantic preference that bridges the existing constructs in the qualitative and the quantitative literatures on interracial marriage and by discussing its implications for further research on race and intimacy.

A DATING-HISTORY APPROACH TO ASIAN AMERICAN ROMANCE AND INTERMARRIAGE

Sociological research on Asian American romance and intermarriage divides between a qualitative literature on how individuals navigate cultural messages regarding interracial intimacy and a quantitative literature on the social conditions that structure the incidence of interracial marriage. The qualitative literature examines the narratives of individuals for culturally derived beliefs and assumptions about group differences. The quantitative literature examines the distribution of spouses for statistical indicators of the structural conditions that affect the likelihood of intermarriage (e.g., marriage markets with distinct demographics and preferences for certain groups over others). Because dating or nonmarital contact precedes marriage, dating histories constitute the immediate context for the narrative construction of romantic preferences and also provide a more robust measure than marriages provide for the romantic behaviors that mediate group relations. We propose that the dating histories of individuals (i.e., their accumulated record of romantic involvements) contribute an important conceptual bridge between the two literatures. In brief, our analysis of romantic involvements within broader life histories uses personal history to connect qualitative discourses with quantitative conditions.

Qualitative Findings on Racial Status Inequality

For the qualitative literature, dating histories form the experiential stage on which individuals narrate their romantic preferences. Instead of treating these personal histories as the basis for romantic preferences, however, qualitative researchers treat experience as secondary to the cultural discourses that individuals deploy to frame their preferences. This search for racial discourses permits qualitative researchers to identify a common cultural repertoire (Frankenberg Reference Frankenberg1993), revealing the social character of romantic preferences regardless of whether individuals marry within or across group boundaries. In brief, our dating-history approach brings personal experience back into the qualitative literature by treating preferences as a function of not only cultural repertoires but also personal history.

Qualitative studies on Asian Americans and romance point to the salience of racial-status inequality in shaping the private behavior of Asian Americans (Chow Reference Chow2000; Fong and Yung, 1995–Reference Fong and Yung1996; Lee Reference Lee, Lee and Zhou2004). Colleen Fong and Judy Yung's (1995–Reference Fong and Yung1996) interviews with intermarried Chinese and Japanese Americans, one-third foreign-born, found that gendered racial stereotypes of Asian inferiority and White superiority pervaded motivations for outmarriage. Similarly, Sue Chow's (Reference Chow2000) interviews with second- and later-generation Chinese and Japanese Americans found that recognition of the status inferiority of Asians to Whites was salient to their spousal preferences, regardless of whether they preferred Whites, preferred Asians, professed no preference, or reported having shifted between preferring Whites and Asians. Sara Lee's (Reference Lee, Lee and Zhou2004) interviews with second-generation Korean Americans found that negative stereotypes of Asian men as inferior to White men were the basis for preferences of women who preferred non-Asian partners, while solidarity against White racism contributed to the preference of middle-class men and women for coethnic or Asian spouses. Other qualitative studies focusing not on romance but on the complex patterns of self-segregation evident among Asian Americans have also pointed to the salience of mainstream cultural assumptions in the prevalent practice of intraethnic othering (Duster Reference Duster1991; Pyke and Dang, Reference Pyke and Dang2003).

These studies document the salience of racial stereotypes in Asian American romantic involvements, especially in the form of internalized racism; however, they also mention another factor that competes with their attribution of preference to racial culture: personal dating history. Upon closer scrutiny, their common use of convenience samples had the unintended consequence of recruiting subjects with extensive dating histories and unusually diverse romantic opportunities. For some subjects, preferences can plausibly be attributed to racial culture because their dating histories are relatively homogeneous. For example, it is clear that some Asian Americans who voice preference for Whites (Chow Reference Chow2000) or claim no preference (Lee Reference Lee, Lee and Zhou2004) have never dated other Asians and therefore cannot be said to have based their preferences on actual experience. Similarly, a history of only or primarily dating Asians seems to characterize some subjects who prefer coethnics (Lee Reference Lee, Lee and Zhou2004) or other Asians (Chow Reference Chow2000). In these cases, the relative absence of experience dating non-Asians suggests that racial discourses, or factors other than personal evaluations, are indeed motivating these pro-Asian preferences.

For other subjects, we cannot set aside the contribution of personal experience because their dating histories are more racially balanced. These include those who voice aversions to prospective coethnic or same race partners that are clearly based in actual experiences dating other Asians (Fong and Yung, 1995–Reference Fong and Yung1996). Similarly, Chow's (Reference Chow2000) subjects who voice no preference report having had relationships with both Asians and Whites, as do half of her subjects who prefer Asian spouses. Without a systematic comparison of preferences narrated out of different dating histories, it is difficult to discern how much racial preferences are a function of controlling images internalized from mainstream culture—instead of personal experiences (Collins Reference Collins1990; Espiritu Reference Espiritu1997; Pyke and Johnson, Reference Pyke and Johnson2003).

As noted in the introduction, coethnic family experience is another aspect of the personal experiences whose effects might be conflated with those of mainstream stereotypes. For many Asian Americans, even if they have had no experience dating other Asians, a disinterest in Asian partners and spouses may exist not as the result of racial culture but instead from an aversion to coethnic families rooted in observations of their own families. Unlike most Asian Americans, Korean adoptees largely have White families and thus are not exposed to the confounding factor of coethnic family experience.

Quantitative Findings on Structural Conditions

Similarly, individual dating history is a missing yet implied variable within the quantitative literature. Mainly using U.S. census data on married couples, quantitative studies have estimated the effects of partner availability and preference on spousal choices, that is, the odds of marrying within or across group boundaries. Their statistical significance reveals the social character of romantic preference regardless of whether individuals voice recognizable cultural discourses. Because dating histories capture the transitions from first meeting to union formation, they provide both (1) more robust indicators of the romantic behaviors that mediate group relations and (2) more direct measures of the structural conditions that influence romantic behaviors. In brief, our dating-history approach expands the operationalization of romantic behavior in the quantitative literature to include nonmarital intimacy while also modeling this expanded conception as a function of the structural conditions that existed before the current distribution of romantic behaviors. These conditions are the conceptions of opportunity (partner availability) and social distance (preference) as developed in the three major approaches to measuring romantic preferences within the quantitative literature: (1) the distribution of marital choices controlling for group size, (2) the level of education required of lower-status partners to compensate higher-status partners for marrying “down” a status hierarchy, and (3) the local signals of relative group position or status. These three otherwise distinct approaches commonly model intermarriage as the result of (1) an insufficient supply of coethnic partners and (2) a preference for marrying certain noncoethnics over others, for example, not enough other Asians and feeling closer to Whites than to Blacks or Latinos.

Since Peter Blau (Reference Blau1977), intermarriage researchers have sought to estimate spousal preferences by adjusting marital distributions for the structural conditions that constrain them, principal among them the relative size of groups in the marriage market (Bratter and Zuberi, Reference Bratter and Zuberi2001; Feliciano Reference Feliciano2001; Harris and Ono, Reference Harris and Ono2005; Heaton and Jacobson, Reference Heaton and Jacobson2000; Kalmijn Reference Kalmijn1998; Lieberson and Waters, Reference Lieberson and Waters1988; Qian Reference Qian1997). We agree that partner availability is an essential component of romantic opportunities, but the absence of data on dating histories often forces researchers to make questionable assumptions about (1) the nature of endogamy, (2) the measurement of romantic behavior, (3) the definition of romance markets, (4) the formation of preferences, and (5) the collapsibility of individual and group preferences (Lieberson and Waters, Reference Lieberson and Waters1988).

First, researchers typically assume that cultural socialization channels individuals to prefer “their own” but also assume that individuals use their race to define their set of natural partners. This otherwise reasonable assumption is questionable for transracial adoptees who experience socialization in families headed by parents from the majority culture (i.e., racially White and ethnically European) (Lee Reference Lee2003).Footnote 2 In such settings, endogamy, or marrying one's own, may actually mean marrying across group boundaries, but secondary data, such as the U.S. census, do not include the information that might preclude this possibility. In contrast, the analysis of dating histories within life histories would provide the identity of the actual natural-partner groups. Indeed, we found that the majority of the Korean adoptees in our sample regard Whites as their natural partners for romantic involvements.

Second, the absence of information on dating histories in secondary data also forces researchers to measure romantic behavior primarily in terms of marital unions. As Kara Joyner and Grace Kao (Reference Joyner and Kao2005) have shown using longitudinal data, an exclusive focus on marriage data underestimates the extent of interracial contact in nonmarital relationships. In contrast, dating histories provide a more comprehensive record of romantic behavior and can thus provide a more robust indicator of how romantic involvements mediate group relations. The structural effects that quantitative researchers have discovered to influence marriages should, theoretically speaking, bear on the entire breadth of romance from casual interest through courtship. Instead of only examining the odds of intermarriage, a dating-history approach could examine the likelihood of increasing intimacy with particular racial and ethnic groups (e.g., never dated Latinos, dated Latinos, and married Latinos).

Third, researchers typically approximate romance markets at a scope substantially larger than the realistic market, traditionally at the level of national racial/ethnic composition (Feliciano Reference Feliciano2001; Kalmijn Reference Kalmijn1998; Qian Reference Qian1997). David Harris and Hiromi Ono (Reference Harris and Ono2005) have demonstrated that the common practice of collapsing local marriage markets into a national “market” can underestimate the effect of group size and overestimate the effect of racial-spousal preferences. In other words, the national adjusted distribution of marriages may still reflect the unmeasured effects of local opportunity constraints rather than only racial preferences. By contrast, dating histories could provide more direct information about the realistic romance market, in particular the local availability of the natural partner group.

In particular, early adulthood is an important life stage in which to assess romantic opportunities not only because most first marriages result from unions formed in this time but also because this life stage grants independence from family control and a significant fraction of the U.S. population spends early adulthood participating in the singular institution of higher education (Rosenfeld and Kim, Reference Rosenfeld and Kim2005). Echoing Zhenchao Qian and other researchers (Heaton and Albrecht, Reference Heaton and Albrecht1996; Heaton and Jacobson, Reference Heaton and Jacobson2000), Michael Rosenfeld (Reference Rosenfeld2005) argues that education acts primarily as a basis for interracial affinity, especially among college graduates.Footnote 3 Similarly, research on college diversity has shown that for young adults raised in predominantly White suburban geographies, college brings greater opportunities to meet non-Whites as peers, albeit with potentially divergent effects on White and non-White romantic opportunities (i.e., more interracial unions for Whites and more intraracial unions for non-Whites) (Duster Reference Duster1991; Tatum Reference Tatum1992, Reference Tatum1997; Valverde and Castenell, Reference Valverde and Castenell1998). In addition to providing non-Whites with opportunities for contact with other non-Whites, college also provides them with unique resources for ethnic exploration and identity development, including ethnic-specific social networks that might further increase the odds of romantic involvements within group boundaries (Shiao and Tuan, Reference Shiao and Tuan2008). In the quantitative literature's language of opportunity as constrained, we would expect ethnic exploration to constrain the opportunities of Korean adoptees for romantic involvements with Whites, their natural partners, while the effect of college participation might be somewhat mixed. Rather than using the racial distribution of current marriages to represent the romance market that produced the marriages, we might use dating histories, especially information about early adulthood, to approximate the realistic market for endogamy.

Fourth, most researchers infer preferences from the distribution of current marriages rather than measure them directly. The exceptions are group-position researchers who use metropolitan-level segregation and inequality indices as indicators of relative group status (Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Saenz and Aguirre1997; Okamoto Reference Okamoto2007). This research finds that local signals of subordinate group status shape Asian American marriage patterns, even controlling for local group size. Specifically, Okamoto finds that “as income inequality between Asians and whites increases, the odds of interracial compared to [intraethnic] marriages decreases” (Reference Okamoto2007, p. 1405). These findings suggest that individuals' exposure to signals of negative status, such as discrimination, might affect their romantic preferences and influence their behavior. However, even these researchers assume no net change in romantic preferences between the time and place individual preferences actually formed and the time and place the married currently reside. For example, an Asian-White couple residing in San Francisco would be modeled as having preferences that reflected the area's current distribution of marriages or level of racial inequality rather than the partners' separate upbringings in Cleveland and New York City. By contrast, dating histories could provide better indicators for the socialization of social distance in the form of (1) the relative presence of “nonnatural” partners in their childhood geography and (2) the extent to which individuals encountered signals of their relative group status in their formative years. We would expect Korean adoptees would feel greater social distance from other Asians if they were raised (1) in isolation from other Asians, (2) in settings characterized by less racial discrimination, or even (3) in historical periods where ethnic pride was less acceptable than assimilation.

Fifth and last, researchers typically do not measure individual preferences but instead infer or measure preference solely with aggregate indicators, conflating individual preference with group preferences, or what Matthijs Kalmijn (Reference Kalmijn1998) refers to as “the interference of ‘third parties.’” Instead of collapsing individual preferences into intergroup social distance, dating histories could provide direct information about individual preferences, similar to the preference narratives examined in the qualitative literature. In brief, we would expect variation among the individual preferences of Korean adoptees and be able to assess, rather than assume, the degree of homogeneity within these preferences.

We integrate our reviews of the qualitative and the quantitative literatures by offering a dating-history approach that combines a cultural analysis with an analysis of social structure. Specifically, we qualitatively analyze how much romantic discourses about race depend on personal dating histories (i.e., the level of intimacy with a particular group), and we quantitatively analyze how much structural location, namely our revised indicators for opportunity constraints and social distance, influences dating histories (i.e., the likelihood of increasing intimacy with a particular group). This approach permits us to address the question of how much the salience of race depends on socially structured personal experience. Is the influence of racial culture independent of personal experience, as the qualitative literature assumes? Is personal dating experience socially structured, as the quantitative literature predicts? How much does the structuring of individual history shape the reach of racial culture?

DATA AND METHODS

In this section, we describe our procedures for data collection and analysis before discussing their limitations. The data for this article come from our study “Asian Immigrants in White Families,” for which we interviewed fifty-eight adult Korean adoptees recruited from a gender-stratified random sample of international adoption placement records. Our sampling frame consisted of the 3255 placements of Korean children by Holt International Children Services to families living on the West Coast between the years of 1950 and 1975. We used semistructured interviews because they combine a rough standardization of questions with the opportunity for subjects and interviewers to expand in greater detail when appropriate. This method also allows us to reconstruct the sequence of events in our subjects' lives, or, in the language of historical analysis, to trace processes both within cases and across cases (Brady and Collier, Reference Brady and Collier2004).

We based our questionsFootnote 4 on the interview questionnaire used by Mia Tuan (Reference Tuan1998) in her study of the salience of race and ethnicity for multigenerational Chinese and Japanese Americans—refining and adding questions to make the instrument appropriate for the experience of Asian adoptees.Footnote 5 In this article, we focus on the data that revealed the adoptees' dating histories, though we also selectively employed elements from their broader life histories. During the interviews, we asked our subjects about the race and ethnicity of the people they had dated, including past and current relationships, probing for their reflections on the backgrounds of their partners to date and for details on the relative seriousness of romantic contacts with individuals in distinct groups, if any.

Holt International Children Services provided access to the placement records through procedures that protected the confidentiality of our subjects and their adoptive families. The complex recruitment process involved the agency's sending letters to the adoptive parents for randomly selected placements, at their last-known mailing address, typically when the adoptee had reached eighteen years of age. The letters asked parents to forward the invitation materials to their adult children, who in turn were asked to mail or fax their consent forms to us, the principal investigators. The final sampleFootnote 6 consisted of thirty-nine women and nineteen men, approximately the same proportions as in the target population despite their equal stratification during recruitment. They ranged in age from midtwenties to early fifties with a mean age of 35.9 years, while their ages at adoption ranged from two months to thirteen years, including 71% who were under two years of age and 7% who were six years or older. The interviews, which ranged in duration from one hour to five hours, were recorded on audio tape and transcribed.

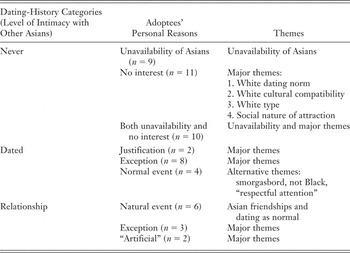

After coding the transcripts by topic, we extracted the text associated with romantic involvements, a first review that generated three dating-history categories.Footnote 7 These were (1) never dated another Asian, (2) dated Asians but not to the point of a relationship, and (3) had one or more relationships with other Asians. Table 1 presents the distribution of our subjects across the dating-history categories.

Table 1. Intimacy with Asians in the Dating Histories of Korean Adoptees

The extremely low rate of coethnic endogamy at either the ethnic- or racial-group level precluded the conventional approach of analyzing intermarriages as deviations from a coethnic norm. Among adoptees, 95% have had relationships with Whites, and only 5% (three adoptees) are married to other Asians, none of whom are Korean. In fact, our preliminary preference analysis revealed that the vast majority of our respondents consider Whites to be their natural partners and count Asians among their nonnatural partners. Instead of operationalizing the constraints on coethnic endogamy and social distance from exogamous alternatives, we examined (a) opportunity constraints on unions with Whites and (b) social distance with coethnics and other Asian Americans. In addition, we shifted our explanandum from interracial intimacy, per se, to “same-race exogamy.”

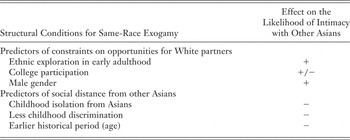

For our quantitative analysis, we employed ordered logistic regression (Hoffman Reference Hoffman2004) to test our expectations that particular structural conditions increased the likelihood of intimacy with other Asians. Because of the relatively small size of our sample, we operationalized these conditions mostly in terms of dichotomized categories for opportunity constraints and social distance. Table 2 presents our expectations for each condition in terms of its effect on the dependent variable, the log odds of increasing romantic intimacy with other Asians, specifically, from never dating Asians to dating them, and from only dating Asians to having relationships with them.

Table 2. Expected Effects of Opportunity Constraints and Social Distance on Adoptee Dating Histories

Note: The likelihood of intimacy refers to the log odds of increasing romantic involvement with other Asians, from never dating Asians to dating them, and from only dating Asians to having relationships with them.

For opportunity constraints, we used ethnic exploration during early adulthood, participation in higher education, and gender, with the general expectation that they constrain opportunities for unions with Whites and thus increase the likelihood of intimacy with other Asians. Specifically, we expect that ethnic exploration during early adulthood restricts the ability of Korean adoptees to meet prospective White partners. Focusing on their lives in the years immediately after leaving high school, we divided our measure between those who pursued any ethnic exploration (n = 32) and those who had no direct contact with other Asians or refrained from taking the opportunity to intensify any available contact (n = 26).

Similarly, we expect that individuals who had participated in higher education would be similarly constrained from meeting prospective White partners. We divided adoptees who did not participate in any form of higher education (n = 8) from those who were traditional college students, those who had other equally significant work or life commitments, and those for whom higher education supplemented more important commitments (n = 50).

Third, we added gender as a constraint on Asian adoptees' opportunities for a White romantic partner. Every qualitative study of Asian American intermarriage observes in some fashion the status inferiority of Asian males to White males in the U.S. courtship system. We expect that male adoptees (n = 19) will face, among available partners, a smaller pool of interested parties than female adoptees (n = 39), implying constrained opportunities for romantic contact with Whites.

As measures of social distance, we employed childhood social geography, the level of discrimination faced during childhood, and historical attitudes with the general expectation that they increase social distance from other Asians and thus decrease the likelihood of intimacy with Asians. Specifically, we expect adoptees raised in ethnic isolation far from coethnics and other Asians to feel a greater sense of social distance from other Asian Americans. We divided our measure of childhood social geography between those raised in predominantly White and rural settings (n = 25) and those raised in either metropolitan or diverse rural settings (n = 23).

Similarly, we expect adoptees who faced less racial and ethnic discrimination in childhood to feel less rejection by Whites and thus more distance from other Asians. We distinguished adoptees who reported no discrimination (n = 8) from those who reported occasional or frequent encounters with discrimination (n = 50).

Third, we expect that older adoptees came of age during historical periods when most Whites, including their adoptive families, unequivocally advocated for their assimilation in both cultural and romantic terms. As a result, older adoptees might feel a greater level of social distance from other Asians than younger adoptees. In contrast with the other independent variables, we employed continuous measures for age: (1) age in years and (2) age squared to test for nonlinear effects.

Turning to our qualitative analysis of discourses, we employed a variation of the constant comparative method of grounded theory (Charmaz Reference Charmaz2006; Glaser and Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967).Footnote 8 We began this analysis by sorting the interview transcripts according to their dating-history category. The primary analytic strategy was to review the interviews in a theoretically informed order for the themes within each dating-history category. We began with the never category on the assumption that the themes in these interviews most directly represented the discourses in the mainstream culture about Asians as romantic partners. We then reviewed the relationship interviews on the assumption that their themes most fully represented the effects of personal experiences of romantic intimacy with Asians. Third, we reviewed the “dated” interviews on the assumption that they revealed the interplay of racial culture and personal experiences of romantic contact.

This analytic strategy permits a heuristic evaluation of the relative influence of racial culture and personal experience. If racial culture is primary in influence, we expect the never themes to also dominate the dated and the relationship interviews. If personal experience is primary, we expect the relationship themes to dominate the dated interviews and the never themes to remain distinct. If racial culture and personal experience are equivalent, we expect the never and the relationship themes to differ substantially but to combine in some fashion in the dated interviews.

Last but not least, we recognize certain limitations in both our sampling procedures and the retrospective nature of our data on romantic preferences. First, although we cannot make a valid estimate of the nonresponse rate because the agency received an unknown number of envelopes returned for incorrect addresses and destroyed them in the interests of confidentiality, we can calculate its lower bound to be 16.3%.Footnote 9 This potentially low rate of response raises the question of sample bias (i.e., whether and how our respondents differ from the nonrespondents in ways that limit our analysis of ethnic exploration). We reason that our sample is directly biased by (1) the underrepresentation of adoptive families who moved away from the homes in which they raised their children and who did not maintain contact with the agency and (2) the absence of (a) adoptive placements that failed during childhood, (b) adoptees who broke contact with their families in adulthood, and (c) adoptees whose parents declined for whatever reason to inform their adult children of the opportunity to participate.Footnote 10

The first bias may have increased the representation of adoptive families that were either more geographically stable or remained interested in receiving the agency's newsletter. However, there is no reason to expect that either geographic stability or parental interest directly bears on adoptees' romantic involvements. The second set of biases may have reduced the representation of cases where family relations were more strained.Footnote 11 To the extent that family strain might lead adoptees to avoid potential White partners, the low level of intimacy with other Asians in our sample may be an underestimate; however, we found no evidence of this kind of aversion within our sample. Furthermore, our sampling procedures are an improvement on the convenience sampling typically necessary for studying such populations. It is practically a tradition within the sociology of transracial adoption to recruit subjects through adoptive parent organizations (Feigelman Reference Feigelman2000; Feigelman and Silverman, Reference Feigelman and Silverman1983; Silverman Reference Silverman1980; Simon Reference Simon and Bean1984, Reference Simon, Gabor and Aldridge1994; Simon and Altstein, Reference Simon and Altstein1977, Reference Simon and Altstein1987, Reference Simon and Altstein1992, Reference Simon and Altstein2000; Tessler et al., Reference Tessler, Gamache and Liu1999). In brief, these considerations suggest that our nonresponse rate actually represents an acceptable level of sample bias.

Second, the use of retrospective narrative typically introduces bias related to memory failure, social desirability, and endogeneity. Older subjects in particular may not accurately remember their more removed personal experiences, and subjects who have less than consuming levels of prejudice against any group may be able to suppress their expression. We cannot be sure of the validity of every interview, but we have taken note of claims that appear questionable, and in those cases we also report alternative explanations.

Ironically, these limitations result from decisions we made in order to address long recognized limitations in the traditional design of transracial adoption research (Hollingsworth Reference Hollingsworth1997). In brief, until recently, many studies of transracial adoptees have surveyed adoptive parents to assess adoptees' level of adoptive adjustment. We suggest that this narrow focus has been a legacy of the controversy that emerged in the 1970s surrounding the appropriateness of Black-to-White placements. More concerned with challenging the early objections of the National Association of Black Social Workers to transracial adoption than with examining the racial and the ethnic experiences of adoptees (Grow et al., Reference Grow, Shapiro and Center1974; Howe Reference Howe1995; Ladner Reference Ladner1977; Neal Reference Neal1996; Perry Reference Perry1993), researchers conducted “outcome-based studies [that] compared transracial adoptees with either same-race adoptees or nonadoptees on measures of psychological adjustment” (Lee Reference Lee2003, p. 716). With only rare or superficial measurements of racial and ethnic experience, much less ethnic identity, these policy-motivated studies interpreted the relative absence of behavioral and emotional problems as indicating the nonsignificance of race (Simon Reference Simon and Bean1984, Reference Simon, Gabor and Aldridge1994, Reference Simon1998; Simon and Altstein, Reference Simon and Altstein1987, Reference Simon and Altstein1992, Reference Simon and Altstein2000).

In contrast, we examined racial and ethnic experiences directly, rather than inferring them from the psychological outcomes of adoptive family placements; relied on the narratives of adoptees themselves, rather than adoptive-parent evaluations of their children; recruited subjects from placement records, rather than self-selected adoptive parent organizations; and interviewed adults who were in a position to reflect upon the development of their ethnic identities and racial experiences, not only within their families but also in broader social contexts as they moved through early adulthood. In sum, we traded the contemporary observations made by parents of their adoptive children for the retrospective narratives of adult adoptees themselves.

We are also mindful of a related issue raised by research in the sociology of culture, namely, that evaluations of current romantic relationships condition how Americans “talk of love” (Swidler Reference Swidler2001). The extent and the intensity with which our subjects use racial culture may depend not only on the power of culture but also on the amount of symbolic work necessary to frame their present relationships as fulfilling the traditional definition of love as “fated and permanent,” a definition proscribed by the institution of marriage. In particular, the adoptees presently attached to Whites might minimize the seriousness of their past intimacy with non-Whites, particularly Asians. To examine the possibility of this bias, we confirmed that our classifications of their romantic histories were statistically independent of their present romantic status.Footnote 12 In addition, we qualitatively confirmed that the adoptees who had had relationships with other Asians did not vary in their preference narratives by their romantic status and the race of their partner (i.e., attached to a White partner, attached to an Asian partner, or unattached). We also explored whether the interviewees who had dated Asians felt more compelled than the interviewees who had never dated Asians to use racial culture to justify their relationships with Whites.

Last but not least is the challenge of endogeneity to the qualitative interpretation of retrospective preferences as preexisting attitudes. In brief, our respondents may not be competent at distinguishing their past preferences from their current preferences that might result from their romantic histories. From a strict position on endogeneity, one cannot claim that the preferences found in our data caused the unions in question; however, one can still interpret these preferences as post hoc constructions that might affect future behavior. More importantly, our central question is not what causes unions but instead whether racial culture matters for preferences narrated from different levels of experience dating Asians; therefore, the post hoc nature of the preference data does not undermine our analysis. By comparison, endogeneity is a greater challenge for most of the existing quantitative research, as it seeks to explain marital decisions while estimating past preferences from the residual of current marriages.

MAPPING THE STRUCTURAL CONDITIONS FOR SAME-RACE EXOGAMY

The quantitative analysis of same-race exogamy confirms that adoptees' romantic histories do indeed vary with our revised measures of opportunity constraints and social distance. To be clear, our claims here are modest in scope. Although five of our six expected effects proved to be statistically significant, the small size of our sample prevents us from making reliable estimates of any interaction terms, forcing us to regard the individual parameter estimates as suggestive rather than conclusive. That said, we regard the results in aggregate as a strong confirmation of the general expectation that social structural location has a significant influence on romantic behavior. Table 3 presents the results of the ordered logit regression of adoptee intimacy with other Asians. As the table indicates, our model provided a significantly better fit than the baseline intercept-only model (p < 0.001), and the nested unordered multinomial model in the test of parallel lines failed to provide a significantly better fit than the ordered model (p = 0.318).

Table 3. Ordered Logit Regression of Romantic Intimacy with Other Asians

* p ≤ 0.05;

** p ≤ 0.01;

*** p ≤ 0.001

Despite the power of our overall model, however, we only found two structural effects that were fully consistent with our expectations in Table 2. Among the opportunity variables, ethnic exploration in early adulthood is associated with a greater likelihood of intimacy with other Asians and in fact increases the odds of intimacy by a factor of six. Among the social distance variables, growing up in a White rural geography is associated with a lesser likelihood of intimacy with Asians and decreases the odds of intimacy by a factor of four (0.238−1).

By contrast, a third effect proved to be more complex than expected, while the remaining two significant effects were in the opposite direction of our expectations. Although their statistical significance validates the general effect of social structure on dating experiences, their deviations suggest refinements for the quantitative literature. The effect of historical period, or more precisely childhood cohort, proved to be nonlinear. As age increases from the midtwenties to the midthirties, the likelihood of intimacy with other Asians decreases, whereas from the midthirties through the forties, the likelihood of intimacy increases. In other words, the oldest and the youngest adoptees in our sample evidenced the least social distance from other Asians, whereas those in their thirties, whose childhoods occurred in the 1970s, internalized the most social distance from other Asians.

Among the opportunity variables, college participation was actually associated with a lesser likelihood of intimacy with Asians and reduced the odds of intimacy by a factor of fifteen. We suggest that if it is true that higher education provides greater resources for ethnic exploration (Shiao and Tuan, Reference Shiao and Tuan2008), then its effects on romantic behavior as observed in the qualitative literature may be entirely mediated by exploration. In the absence of exploration, colleges may largely function for adoptees as opportunities for “different-race endogamy” with White partners. Among the social-distance variables, the absence of childhood discrimination was associated not with lesser intimacy with other Asians but instead with a greater likelihood of intimacy, increasing the odds of intimacy by a factor of seven. We suggest that discrimination, as experienced by Korean adoptees, may actually increase their social distance with other Asians, at least far more than it increases their distance with Whites. Lastly, male gender surprisingly did not show a significant association with the likelihood of intimacy with other Asians; however, gender does appear in the discourse analysis as moderating how adoptees interpret the same level of intimacy with other Asians.

In sum, our quantitative analysis shows that structural conditions influence the likelihood that adoptees will experience romantic intimacy with other Asians. The adoptees who are most likely to have experienced intimacy with Asians are those who grew up in either the 1960s or the 1980s, who did not experience racial discrimination in childhood, and who explored their ethnicity in early adulthood. The adoptees who are the least likely to have experienced intimacy with Asians are those who grew up in the 1970s, grew up in White rural geographies, and attended college. We next turn to the meanings that the adoptees invested in or associated with their personal dating histories and to the question of how much their use of racial culture depended on the structural conditions represented by the different levels of intimacy with other Asians. In brief, does the salience of race depend on socially structured romantic contact?

EXPLORING THE CULTURAL INFLUENCE OF RACE IN ROMANCE

Our qualitative analysis of preferences found race to be salient across all three levels of romantic contact with other Asians, despite each level's distinct structural conditions. The adoptees in the never category divided into three groups: (a) those who had never dated other Asians because Asians were unavailable, (b) those who had never dated other Asians because of no interest, and (c) those who invoked both unavailability and no interest to explain their never having dated Asians. We used the never/no interest group to identify the major themes in racial culture, and we confirmed the use of these themes with the never/both unavailable and no interest group. As shown in Table 4, these groups are part of a larger analytic system of categories, groups, and themes wherein the categories denote the levels of romantic intimacy, the groups distinguish the personal meanings of that category, and the themes identify the cultural elements that individuals deployed to construct their personal meanings.

Table 4. Analytic Framework for the Salience of Race in Romance

The adoptees who had dated other Asians but had not had relationships with them divided into three groups, two that drew extensively on the major themes and one that drew on a spate of alternative themes. These adoptees framed their experiences dating Asians as (a) justification for not dating Asians any further, (b) an exception to their usual practice of dating Whites, and (c) a normal event in special context, that is, a rare event that they nevertheless characterized as normal relative to certain extrinsic criteria.

The adoptees who had experienced at least one relationship with another Asian divided into three groups, two that also drew on the major themes and one that drew on a common alternative theme. For many, having had relationships with Asians was simply (a) a natural event, that is, an event they regarded as a natural outgrowth of their peer networks. Others characterized their relationships with Asians as (b) an exception in their dating histories. For yet other adoptees, their relationships were with Asian nationals in Asia and arose from (c) circumstances that we classified as “artificial.”

The Major Themes

The four major themes of racial culture were (a) dating Whites as an implicit norm, (b) compatibility with White culture, (c) having a “type” based in White looks, and (d) being aware of romantic attraction as socially shaped. First, the adoptees took for granted that Whites were the group they would date. They treated dating Asians as requiring a special interest that was nonexistent for them. Sometimes, adoptees voiced this theme by interpolating White friends who had questioned their noninterest in dating other Asians. As Ella Scott, a twenty-seven-year-old customer-service manager and marketing assistant, quipped, “I'm not attracted to Asians. Because I'm Asian, I guess, I look in the mirror, and that's enough for me.” She viewed dating Asians as a sort of overindulgence, and, later in our interview, she added that being seen dating another Asian was virtually an invitation to stereotyping. In the absence of being questioned, however, adoptees like Ella simply took dating interracially for granted.

Second, adoptees perceived themselves as more culturally compatible with Whites through vicarious comparisons that reflected a racialized division between “American” and “ethnic” cultures. Kirsten Young, a twenty-nine-year-old homemaker and administrative assistant, explained her dating preferences:

All Caucasian. I always, and I've been accused of being racist myself, because I always felt I did not want to date or marry anyone that was of another um, ethnicity…. Because I always thought, you know, relationships are hard enough as it is. And then when you throw different cultures in, it makes it even harder. Um, you know, a lot of, in a lot of races, or a lot of cultures, women are second to men. And I don't feel I should be second to any man [laughs]. And so I just never really felt comfortable dating other races. And so all my boyfriends have been Caucasian or of mostly, you know, American culture. Caucasian.

Adoptees like Kirsten assumed that personal interests, personality, and gender roles were culturally distinct, as if group differences existed categorically between White and Asian individuals. Furthermore, when she stated her lack of interest in partners of “another” ethnicity, she meant non-Whites, not non-Koreans. Indeed, her preferences are grounded in a perception of herself as ethnically White, rather than in an Orientalist compatibility of “Eastern” and “Western” traits (Said Reference Said1979).

Third, adoptees cast themselves as inexorably attracted to characteristically White body types and physical appearances. Some evaluated Whites as more sociobiologically attractive than Asian women and men. The comments of women confirmed the low status of Asian males, while the comments of men suggested that White women provoked a greater “gut-level” interest. Julia Reiner, a thirty-one-year-old legal assistant, recalled her dating history before her husband:

I had one boyfriend who was half Black and half Puerto Rican, and he was really handsome…. I knew after the half Black half that I never was attracted to Asian men, and I don't know why. I always kind of knew I'd find this tall, blond, green-eyed guy, and I did. And some Asian men are attractive to me, but for a husband…. I just thought I was more honed in on a Caucasian man for some reason.

In her mind, Blacks, Puerto Ricans, and Asians were all deviations from her “tall, blond, [and] green-eyed” type. Furthermore, she experienced having a type as not only a physical attraction but also as a fate that could be tested but only to be confirmed.

Fourth, adoptees recognized that romantic attraction was not purely between individuals but often involved social messages. Some saw their own White-oriented dating histories as a product of their environments, but most focused on how racial stereotypes complicated their search for good White partners. In particular, female adoptees recognized that the larger society categorically invested Asian women with a special kind of attractiveness, which made them feel ambivalent at best. As Ella Scott bluntly put it:

I don't know why they openly admit this to me. Um, they admit to me that they are attracted to Asian women … or they're attracted to ethnic women. That is a polite way of putting it…. That's a really big turnoff for me…. It makes me feel inferior.

Some were especially suspicious if they experienced the attraction as an unexpected shift after having spent their adolescence in the shadow of an “all-American,” blond-haired, blue-eyed ideal.

This concern for the recognition of their individuality appears to be female in character, as made most apparent in our interview with the only male adoptee to attribute his exclusively non-Asian dating history to a lack of interest. Ryan Hilyard, a twenty-nine-year-old internet-banking sales representative, did not cite this concern, but instead described the astonishment of his friends, who were largely White and male, that he, unlike them, was rarely attracted to Asian women. He mused:

It's a curiosity to my friends. It's somewhat a curiosity to myself…. I haven't really grasped it other than I can say that I grew up in this very White-oriented Caucasian upbringing … lifestyle situation, environment, socially, television, and all those typical things that they say.

And yet Ryan acknowledged that this explanation was not sufficient because his friends also grew up in the same kind of environment. His gut answer emerged when he tried to remember the few Asian women he had found attractive:

I think they might fit more into the—what the typical American would consider a beauty or … not as round, typical round or flat Asian features. I don't know. That's another one. It's somewhat of a difficult issue for me. Just because it's almost [like] I'm hitting on myself [laughs].

Ryan does share important similarities with his female counterparts by explicitly voicing the normality of dating Whites—defined against the redundancy of dating another Asian—and an awareness of the social nature of attraction. However, his reaction to the special interest in Asian women is less a concern for true acceptance than a challenge to his normality. For Ryan's friends, not being interested in Asian women is grounds for teasing. He quipped about their reaction: “It's almost, ‘What's wrong with you?’” Despite the gender difference, however, both cases share a common factor: the reference group is White men, whether as prospective romantic partners or as heterosexual peers with the prototypic masculine tastes in women.

As these adoptees have never dated another Asian, their sentiments are indicative of certain discourses privileging Whites as learned from the mainstream culture. Whether as a White racial frame (Feagin Reference Feagin2006) or a White normative perspective (Bell and Hartmann, Reference Bell and Hartmann2007), scholars have documented that Whiteness remains the center of gravity in contemporary racial culture such that non-Whites encounter the conception of Whites as the ingroup and non-Whites as the outgroup, not merely as a White standpoint but also as a broader social reality.

Racial Salience and the Moderating Role of Gender

The salience of these major themes did vary by the adoptees' level of experience dating Asians. That said, we found racial culture to be quite salient for two-thirds of our respondents, albeit nuanced in various ways by gender. As seen in Table 4, these adoptees included not only those who had never dated another Asian (the never/no interest and the never/both unavailability and no interest groups) but also the adoptees who had dated but had not had relationships with other Asians (the dated/justification and the dated/exception groups) and those who had had at least one relationship with another Asian (the relationship/exception and the relationship/“Artificial” groups).

Although the adoptees who had never dated other Asians because of both unavailability and lack of interest primarily gave the reason of the unavailability of Asians as romantic partners, these adoptees also drew on other themes, themes exclusively from the same repertoire as the adoptees from the never/no interest group. Among the never/both unavailability and interest group, gender influenced how frequently adoptees employed racial culture to give meaning to their romantic histories, with women more likely to draw on its normative, evaluative, and social characterizations to define their dating preferences.

Among the adoptees who had dated other Asians but not to the point of having relationships, most simply framed their experiences as exceptions to their dating norms and preferences; however, it was only women who framed their experiences as justification for a subsequent avoidance of Asians. For Ok-kyun Hollander, a thirty-four-year-old executive assistant, dating “two Asian boys” was her attempt at “just kind of trying them out to see if I liked them.” After high school, she had moved away from the White rural community of her childhood to work in a diverse metropolitan area. It was a new start away from the adolescents who had never asked her out for dates, and in her new surroundings she found that men were less shy about showing romantic interest, albeit also in unwanted ways. Sometimes it was the way they approached her:

That's kind of when I got inclinations that men—I knew the kind of guys who were looking strictly to date Asian girls. And I kind of got my first taste of that, I was like—'Cause you can—I swear you can tell. If they're coming from a mile away, you can just tell…. They don't have to even say a word … because they just look at you funny. And that's really uncomfortable. And I just want to deck 'em, you know.

Other times, it was her self-consciousness about her Asian appearance, particularly when she was near other Asians, particularly Asian men. As she put it, “To this day I am really uncomfortable around [other Asians]. I think it's because I'm just not used to it. I don't have any friends that are Asians.”

Despite the numerous White men who showed that special interest in Ok-kyun, they remained her dating norm, whereas it took dating only two Asian men to sour her on dating Asians. In particular, she felt appalled that these men felt an attraction to her based on appearance, and she wondered about its depth:

I knew that they liked me from day one. And I just thought, “Gosh, if they just like me on appearance alone, something's wrong.” Like, “What if I get into a horrible car accident?” But I gave it a try.

As a result, she realized that she had a preference for White men which she attributed to having had a “type” for a “clean-cut” look that she had seen in high school. She recognized the social nature of attraction not as distorting the authenticity of her type but instead as a future challenge for her favorite nephew who was also an Asian adoptee. In a matter of fact way, she confided that he was “going to have to learn … that not every girl's going to want to date him. They're not that high on Asian men, you know, and he's got to know that.” In brief, she expresses a double standard about the acceptability of preferences based on race and appearance: if the object of attraction is Asian, then the preference is superficial, but if the object of attraction is White, then the preference is inevitable.

Similarly, among the adoptees who had had at least one relationship with another Asian, it was only women who used racial culture to frame their relationships with other Asians as exceptions to their dating norms and preferences. Sharon Harding, a twenty-five-year-old human resources staffer, was in her second relationship with the same Chinese American man. During their first relationship, she remembered:

[I was] scared to meet his mom, I was scared to, you know, everything…. I'm like, “Oh, what if I do something that's completely offensive without,” you know—not even knowing it. [And] not only did I meet his mom, I met like his aunts and his cousins.

By comparison, in their present relationship, she reported, “This time it was a lot easier, because I knew everybody [laughs]. I was like ‘Oh, hi you guys.’” Nevertheless, when we asked whether his being Asian affected their relationship, she emphasized, “He's very, very Americanized. I think that if he was more traditional, I don't think we would have been dating.” In other words, Sharon still perceives her boyfriend as an exception from her expectations of Asians, despite her extensive contact with his friends, many of whom are second-generation Asian Americans.

The Limits of Racial Salience

By contrast, we did not find racial culture to be salient for one-third of our respondents, namely, those who had never dated other Asians simply because they were unavailable, those who had had at least one relationship and regarded the experiences as natural events, and those who had only dated other Asians but still characterized the experiences as normal events (Table 4). We suggest that the never/unavailable group was uniquely isolated from other Asians to a degree that precluded the need to deploy racial culture to explain their never having dated Asians. As Sherwin Wright, a forty-four-year-old finance manager, recalled, “I don't think I've ever dated anybody but Caucasian…. I think it's just the—mainly that's what I was around…. I can't even really think of any specific [opportunity]…maybe college a little bit, but not even that.” Placed with his adoptive family in the late 1950s, Sherwin arrived in advance of both the post-1965 resurgence of immigration and the demographic shifts that the new second generation would bring to college campuses. This isolation implies a condition limiting the influence of racial culture: a threshold level of contact with others of the same race.

Second, our interviews with the relationship/natural events adoptees suggest that the composition and culture of friendship circles may be a proximate mechanism through which racial discourses in the mainstream culture affect romantic preferences. Among those who invested their Asian relationships with normality, the primary reason seemed to be their unusually diverse social networks. “All my girlfriends have been Asian…. So either they're Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, Chinese, Japanese,” reported Brian Packard, a twenty-seven-year-old technical writer, who was, however, at a loss to explain why. When we questioned him about the racial composition of his friends, he responded in a telling fashion:

Interviewer: Is it maybe because your friends are—

Brian: Possibly. Most of my friends are Asian. So their friends are Asian.

Brian assumes that it is normal for an Asian such as himself to have Asian friends and for an Asian to prefer Asians as dating partners even across ethnic lines. These assumptions, of course, contrast with the normality of White friends and partners who are prevalent among most of the adoptees. In cases such as Brian's, having relationships with Asians is a natural outgrowth of belonging to panethnic but racially bounded social networks, parallel to the White networks surrounding other adoptees. Revealingly, those in the “naturally Asian” relationships are primarily members of the youngest cohort, aged twenty-five to twenty-nine years old, and are still dating or in nonmarital relationships.

Other adoptees attributed the normality of dating Asians to other kinds of social networks. For Charlene Jones, a thirty-year-old chemist, and Ruth Weasley, a forty-year-old homemaker, their relationships were natural in the context of having close friendships with both Asians and Whites, though only for Charlene were these friends clearly a part of an integrated network instead of separate circles. Currently married to a White man, Charlene reported:

My first boyfriend was Asian. My second was Caucasian. I alternated pretty regularly … Asian–Caucasian, Asian–Caucasian, Asian [pause], Caucasian [pause], and then, Caucasian. And then I was married…. It's kind of the—like the luck of the draw…. Like same with my friends. It was, I liked them, they happened to be Asian. Or, I liked them, they happened to be White.

Despite Charlene's apparent nonchalance, integrated friendship circles such as hers were extremely rare among our respondents. In brief, another possible limit to the influence of racial culture is based in social networks—especially a critical mass of coethnic or same-race potential partners.

Third, the narratives of adoptees who had only dated other Asians but still saw those experiences as normal events reveal how adoptees could redefine Asians as relatively normal partners even while primarily dating Whites. These adoptees invoked a range of meanings that positioned dating Asians as normal by relatively extrinsic criteria, such as completing a smorgasbord of dating experiences, not being Black, and satisfying a desire for respectful romantic attention as yet unfulfilled by White males. For example, some framed their Asian dating experiences as normal given their interest in dating a variety of men, a pro-diversity alternative to White norms and preferences. Tracey Tulane, a forty-seven-year-old music teacher, asserted, “I tried to have a nice variety [laughs],” and offered:

I did date a Black boy. Right before I got married [the first time]. And I always thought I wanted to, but I hadn't met anybody I wanted to date. But, you know, I was on a smorgasbord, and I wanted to give everything a try [laughs]. I even got a guy who wasn't circumcised [laughs].

Nonetheless, when she provided a detailed account of her boyfriends, the actual range was relatively homogeneous, mostly White men. Recognizing the inconsistency, she speculated, “Maybe they feel more confident. I don't know. But I used to be a hottie, see, so that's probably why. 'Cause when you're a hottie, a lot of guys don't look at you [laughs]…. [Are] afraid to approach you.” Rather than claiming to have a romantic type that explained her dating history, she suggested that a status hierarchy among men might have shaped what prospective partners imagined to be her type. In sum, the White orientation of racial culture can be amended to include Asians, though we cannot point to any common circumstances that facilitate the influence of these extrinsic criteria. However, both the relationship/natural event and the dated/normal event interviews do suggest the influence of alternative racial discourses distinct from mainstream racial culture.

CONCLUSION

We have explored the salience of race in the romantic involvements of Korean adoptees, using a probability sample of international adoptive placements into White American families from the 1950s to the mid-1970s. Our findings have implications for the literature on Asian American romance and intermarriage, as well as for broader research on race and intimacy. Foremost, we contribute a preliminary bridge between the quantitative and the qualitative definitions of partner preference in our conception of personal meanings that mediate (1) levels of romantic experience and (2) cultural themes deployed as assumptions and beliefs. Individuals draw upon a shared repertoire of cultural themes to invest meaning into their romantic histories; specifically, they deploy racial culture, constructing gender-moderated interpretations of their dating histories.

Sometimes this meaning is a personal preference in the conventional sense of either a “first choice” or “last choice,” while at other times it is a personal dating norm that functions more like a “rule of thumb” by which to evaluate prospective partners in combination with other nonracial criteria. In either case, the meaning for the adoptees amounts to a romantic orientation toward Whites. We find that racial culture is salient for adoptee preferences and dating norms across a broad range of romantic contact with Asians, even though the specific level of intimacy depends on distinct structural conditions.

We have largely confirmed the contention of qualitative researchers that racial culture is pervasive in its reach and have provided unique validation of the assumption that direct contact with racial others (i.e., personal experience) is the weaker partner in the interplay of experience and culture. However, we have also demonstrated the limits of racial culture's reach and therefore caution against the overgeneralization of discourse analysis to individuals' cultural repertoires. That said, only extreme isolation, certain social networks, and alternative discourses countered the propensity to draw on any racial culture in our study.

Regarding the content of racial culture, we cannot confirm recent assertions that the contemporary racial formation is dominated by color-blind racism (Brown Reference Brown2003) or a new non-Black over Black divide (Yancey Reference Yancey2003). Most of our subjects simply assume a White orientation to be normal or preferable, rather than defending it as nonracial or nonracist; and most do not treat Asians, at least in the romantic arena, as equivalent to Whites or indistinguishable as merely non-Blacks in combination with Whites, Latinos, and Native Americans. At best, our results are more consistent with a simple hierarchy of White over Asian over other non-Whites (Dhingra Reference Dhingra2003; Shiao Reference Shiao2005).

With respect to quantitative studies, we have also confirmed that the structural conditions of opportunity and social distance significantly influence the adoptees' level of romantic intimacy with other Asians. Our results also suggest alternative conceptualizations of opportunity and distance. Among the opportunity variables, college participation may polarize adoptees who use institutional resources to explore their ethnicity and those who choose not to explore. Among social-distance variables, the age effect may mask multiple historical mechanisms shaping the level of social distance with other Asians. Two of these mechanisms might be (1) the level of anti-Asian attitudes in the larger society and (2) the level of ethnic pride among Asian Americans. Both factors might promote racial solidarity, but the decline of the first before the rise of the second might have increased the sense of social distance internalized by adoptees whose childhood occurred during the historical transition. Also, since most who experienced childhood discrimination reported occasional rather than frequent encounters with discrimination, the effect of status signals like discrimination may depend on their magnitude. Counter to expectations that discrimination might generate reactive coethnic or panethnic solidarity (Jeung Reference Jeung1994), we find that “romantic solidarity” is greatest when discrimination is absent, suggesting that the internalization of a White romantic orientation is actually associated with a modest level of stigmatization. In addition, our qualitative results suggest that structural conditions indirectly shape the influence of racial culture. The groups that are arguably the most free from racial culture are (a) the never/unavailable adoptees who are uniquely isolated from other Asians and (b) the relationship/natural event adoptees who participate in Asian American social networks.

Further research, however, is necessary to elaborate our conception of individual romantic preference as a bridge between racial culture and socially structured experience. First, is the racial culture we identified generalizable to other populations? For example, Black, Latino, Native American, and even other Asian adoptees might confront other racial themes in the mainstream culture. Second, how does being raised in a coethnic or same-race minority family moderate the influence of racial culture? Nonadopted and same-race adopted Asian Americans and other non-Whites may receive racial culture in a different way, for example, using it more extensively if they possess an aversion to coethnic families.Footnote 13 Third, how do social networks mediate the significance of interracial intimacy? If the non-White partners largely come from White networks, it is questionable whether these unions are eroding barriers between groups, rather than expressing a more central role for friendships in maintaining racial boundaries and inequalities. More theoretically, do social networks function as mechanisms for racial culture or as the consequences of structural conditions?

Fourth, the collection of more detailed dating histories would refine our dating-history approach, expand the range of groups with which relative intimacy could be examined, and control for potentially important characteristics of individual dating histories. This paper analyzes a segment of broader data collected for a life history analysis, rather than data collected for a study with a primary focus on romantic involvements. Future research would benefit from a greater emphasis on the qualitative mechanisms identified in our study: extreme isolation, friendships, and alternative discourses. Similarly, our scope of data is sufficient for studying the Asian-White boundary in romantic unions but not for studying other romantic boundaries, for which more consistent inquiry about intimacy with other groups would have been necessary. In addition, collecting data on the technical characteristics of individual dating histories would permit controlling for important nonracial variations, such as the length of the dating history, the number of dating partners, and the number of exclusive relationships.

Fifth, an increase in sample size would also permit a fuller exploration of structural effects and a more conclusive test of our quantitative results. A larger data set would produce more reliable estimates of the opportunity and the social-distance effects, allow for an examination of their possible interactions, and permit more detailed measurements of structural conditions and more detailed estimates of their effects. On a related note, a multiregional or even national study would test the generalizability of our findings beyond adoptive placements in the western United States.