INTRODUCTION

“Race” is often understood as a way of categorizing groups of people according to a set of heritable physical characteristics associated with continental ancestry—including skin color, facial features, and hair texture. Blacks, Whites, Asians, and Native Americans are thought to be paradigmatic racial groups. “Ethnicity,” by contrast, is often understood as a way of categorizing people according to their cultural and linguistic heritage. In the United States, Chinese-Americans and Irish-Americans are examples of paradigmatic ethnic groups.

Almost every ethnic group—at least in North America—is thought to be a proper subset of some racial group. For example, all Chinese-Americans are Asian, but not all Asians are Chinese-American; all Irish-Americans are thought to be White, but not all Whites are Irish-American; and all Haitian-Americans are thought to be Black, but not all Blacks are Haitian-American.

This is, for the most part, reflected in the way federal agencies collect demographic data—except for the way they categorize Latinos. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) requires all federal agencies that collect racial and ethnic data to treat Latinos as an ethnic group whose members can be of any race (OMB 1994).Footnote 1 This raises a number of normative and conceptual questions about the relationship between race and ethnicity, and more generally about the kinds of demographic information governments can and should aim to know. Why, if at all, should federal agencies categorize Latinos as an ethnic group, rather than a race? And what are the reasons for government collection of racial and ethnic data in the first place?

The U.S. federal government has employed a huge variety of racial and ethnic classificatory schemes since it began systematically collecting data on the demographic makeup of the country’s population in 1790 (Bennett Reference Bennett2000). Since 1980, the decennial census has included a question about the respondent’s race along with a separate ‘ethnicity’ question asking whether the respondent is of Latino origin (Snipp Reference Snipp2003).

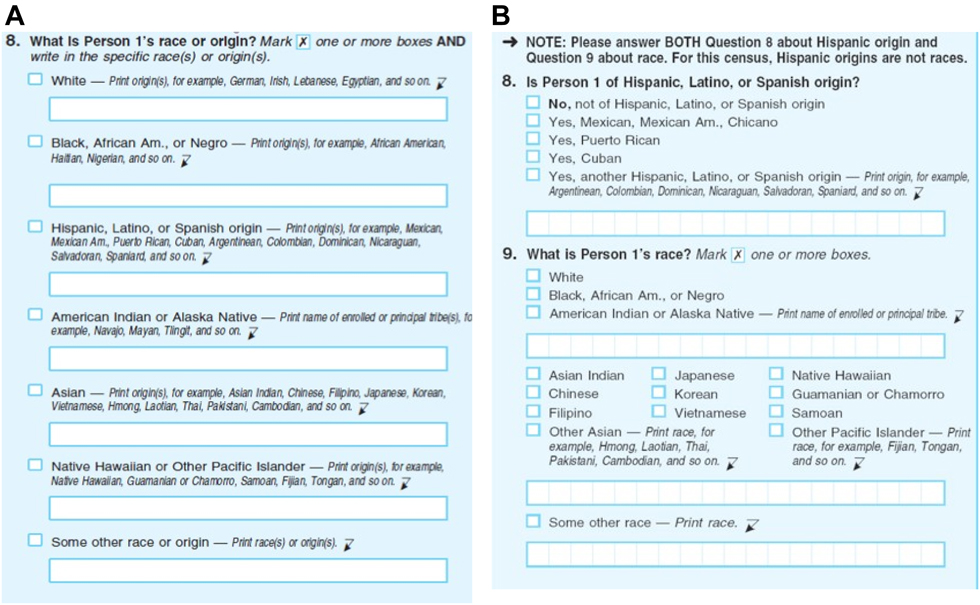

Around four out of every ten self-identified Latino respondents on the last three censuses have refused to identify with any of the OMB-designated racial options, instead reporting that they are of “some other race” (Compton et al., Reference Compton, Bentley, Ennis and Rastogi2013). In response, the Census Bureau has been experimenting with the possibility of combining the two questions on the 2020 survey, treating Latino origin as an alternative to the OMB-designated racial categories, rather than an overlapping ethnic category (Compton et al., Reference Compton, Bentley, Ennis and Rastogi2013). Below is a replication of the ‘race’ and ‘ethnicity’ questions on the 2010 census form and an example of the combined question format on one of the experimental alternative questionnaires.

Fig. 1. a) 2010 Census Ethnicity and Race Questions; b) Alternative Combined Race/Ethnicity Question.

The combined question format effectively equates Latino origin with race, by framing it as a genuine alternative to paradigmatic racial identifications like “Black” and “White,” rather than a category that must overlap with at least one of them. Census respondents cannot be expected to draw a distinction between racial and ethnic categories on a combined question format survey, and if that format is adopted, it could be a step toward the OMB revising its standards for the collection of racial and ethnic data yet again.Footnote 2

The political stakes surrounding this proposal are high. Government systems of racial categorization influence the racial identities of the population, and in turn, racial identity influences political attitudes and outcomes (Nobles Reference Nobles2000, Reference Nobles, Kertzer and Arel2002). As Victoria Hattam (Reference Hattam2005) puts it, “whether Hispanics identify as white or as people of color may shift the balance of power between the Democratic and Republican Parties, since racial identification and party allegiance have long been aligned” (p. 68). Administrative agencies cannot base their decisions on these political considerations, since it is not their job to manipulate the racial identities of the citizenry in order to produce some favored political climate or outcome. But these stakes give the general public reason to care about how agencies resolve debates about racial and ethnic demography.

The conceptual criteria needed to guide these decisions are complex, despite agencies being somewhat limited in the normative considerations they can legitimately bring to bear on them. In this paper, I attempt to shed some light on those criteria through a philosophical examination of the aims of racial demography, combined with a synthesis of a wide range of empirical research that bears on the racial status of Latinos in the United States. In principle, any federal agency responsible for collecting survey data on racial population demographics should be responsive to these considerations, though I focus on the decennial census as a central case study.Footnote 3

The thesis of the paper has two parts. First, I argue that racial data collection on Latinos should primarily aim to capture how Latinos are racially perceived in the United States rather than attempting to capture how they prefer to identify themselves, or facts about their continental ancestry. Second, I argue that to capture racial perceptions of Latinos, government surveys need to balance three subsidiary criteria: the ability to measure intra-group differences in how Latinos are racially perceived; the promotion of self-reported racial identifications that are useful as a proxy for social perceptions of race; and the extent to which Latinos are collectively perceived as a race. I show that a combined question survey format for racial and ethnic data collection would likely be more amenable to these goals than the current format and suggest some areas where further empirical research is needed.Footnote 4

The thesis I defend here should not be understood as an all-things-considered normative appraisal of the racialization of Latinos. I do not attempt to answer questions about whether administrative agencies ought to stop collecting racial and ethnic information completely (see Prewitt Reference Prewitt2013). Nor do I enter the debate about whether the category “Latino” should be eliminated from the government’s system of racial categorization, or from our popular consciousness altogether (see Beltran Reference Beltrán2010; Mora Reference Mora2014, pp. 155–171). I am concerned strictly with how U.S. federal agencies ought to categorize Latinos for the purpose of racial and ethnic data collection.

As mentioned above, the kinds of normative considerations that executive branch agencies can legitimately bring to bear on this question are limited in scope. For example, agencies cannot legitimately choose a system of racial categorization over other alternatives based on controversial views about the nature of social justice, or ideas about what might best serve some partisan political aim. This leaves a somewhat narrow space for the normative evaluation of systems of racial categorization where the executive branch of government is concerned. But that narrow space is complicated, and the existing literature to date has left it extremely underexplored. This paper picks up the task of explicitly charting the area.

THE AIMS OF RACIAL DATA COLLECTION

Proponents of both the alternative “combined question” format and the existing “separate question format” argue that their preferred approach would produce more accurate data (Lopez Reference Lopez2013; Prewitt Reference Prewitt2005). But neither side gives an explicit account of what the data should aim to be accurate about, or which aims their preferred data collection method better satisfies. There are a number of technical and methodological considerations that must inform these decisions. For example, it is desirable for data sets to allow for comparisons across different time periods, ceteris paribus; and some data collection methods are more costly to administer than others. But my arguments here will focus instead on the broader normative and conceptual considerations that ought to guide the inquiry.

In this section, I introduce and consider three conceptual criteria for measuring the accuracy of racial demographic data. The social perception method tells agencies to produce demographic data that reflects how people are racially perceived by one another in society. The identity-recognition method says that racial demography should aim to track how people personally identify themselves. The biomedical method tells agencies to design their survey methods so that racial demographic data best serves the needs of researchers in the health sciences.

It is conceivable that the best way to design the government’s system of data collection would be to structure it around an equilibrium point between these different (and at times conflicting) desiderata. But I will argue that only one—namely, the social perception method—should play a significant role in determining how the government collects data on Latinos.

The Social Perception Method

Federal, state, and local government agencies use racial and ethnic survey data to monitor inequalities in employment, educational achievement, criminal justice, health, and housing; for program administration and civil rights enforcement; and to draw legislative districts. With respect to race, antidiscrimination law is primarily a safeguard against people being mistreated on the basis of how they are racially perceived, not on the basis of deep truths about their actual racial status or facts about their continental ancestry. This is true in large part because of the way that racial discrimination paradigmatically and normally operates: as a response to racial perceptions, not facts about continental ancestry or personal identity.

This is easiest to understand in individual, micro-level cases of racial discrimination, rather than structural or macro-level cases of systemic racial discrimination. For example, in 2015, police officers in Madison, Alabama brutally body-slammed Sureshbhai Patel, a 57 year-old Gujarati man who was visiting his family from India, leaving him paralyzed after a neighborhood resident called 911 to report “a skinny black guy” who was “just kind of wandering around” and said “I’d like somebody to talk to him” (Fausset Reference Fausset2015). Patel was treated with suspicion, and brutally abused, on the basis of being perceived as Black, even though he is Asian. Similarly, having a “Black-sounding” name is disadvantageous for job applicants, regardless of how they conceive of their own racial identity, and regardless of what their continental ancestry is. These applicants are more likely to have their résumés discarded, and less likely to be called for an interview than equally qualified candidates (Bertrand and Mullainathan, Reference Bertrand and Mullainathan2004). A homebuyer who identifies herself as Black on a loan application could be steered toward subprime mortgages or less desirable neighborhoods by discriminatory lenders or real estate agencies even if she only accidentally checked the “Black” box on the application.

Even if there were facts about what races exist, and who belongs to which race, discriminatory actors could not discriminate directly on the basis of those facts. Nobody can be motivated by facts about the world in and of themselves (Hieronymi, Reference Hieronymi2011). An actor may know some proposition about the world to be true and perform some act on the basis of that knowledge, but the basis for the act cannot be that the proposition is true, or even that her belief in that proposition is justified. Rather, there must be some psychological mechanism that explains the act—and neither the truth of the proposition, nor the facts about whether or not the actor’s belief in that proposition is justified, can explain such a mechanism. That the belief is true, or that it is justified, might entail that the act is also justified (or at least be necessary for it’s being justified)Footnote 5, but those properties of the belief cannot themselves be part of the motivation for action, as an action must be motivated by the attitudes of the agent.

We might think, consistent with this uncontroversial view about the metaphysical limits on our potential motivations for action, that racial discrimination could be a response to something other than the perception of racial membership: namely, a response to perceptions about racial self-identification. That would be misguided, however. There is a well-documented phenomenon of discrimination on the basis of what we might call “racial performativity,” or the exhibition of behaviors or views commonly associated with one or another racial or racialized group—for example, “acting White” or “acting Black” (Carbado and Gulati, Reference Carbado and Gulati2013). But this kind of discrimination does not really target the victim’s racial self-identification as such; rather, it target’s the extent to which the discriminatory actor associates the victim’s mutable characteristics—patterns of speech, dress, grooming, cultural reference points, and the like—with a favored or disfavored racial group. For example, a Black associate at a large corporate law firm in New York City might be implicitly penalized for wearing her hair in dreadlocks, braids, or other “natural” hairstyles, speaking in African-American Vernacular English, or vocally supporting the Black Lives Matter movement. But she need not have any particular racial self-identification to do these things, and her self-identification is not what she is being penalized for; rather, she is being penalized for the perception that she is, or is acting, “too Black.” Similarly, we can imagine a “white shoe” firm that is considering a senior associate for partnership, but whose partners are worried that the associate considers her Blackness so central to her identity that making her a partner would distract from the firm’s current ethos. This kind of discrimination is in some (but not all) ways akin to discrimination on the basis of political affiliation. Here, what is being targeted is not so much the associate’s racial self-identification per se, but rather her conception of the normative mandates that her racial identity entails; in other words, her racial politics.

In order for an employer to discriminate against a particular racial self-identification as such, it would have to find a way to discern the racial self-identification of its actual or potential employees, and it would need to have some objection to either the content of that self-identification, or to having a racial self-identification in and of itself. Cases like this would seem to be either rare or far-fetched. For example, we could imagine a hypothetical firm that has collectively adopted an extreme form of the view known as “racial eliminativism,” which holds that there are no races, and that we should no longer think of ourselves as if there are any distinct racial groups, or even groups that have been treated as such. This firm might penalize all prospective employees who have a racial self-identification of any kind. But nobody is worried about this kind of discrimination in the actual world. And it is very hard to imagine a firm discriminating against an employee merely for thinking they are Black, if in fact they are Black, and are perceived as such by the firm and by everybody else. The point here is not that civil rights enforcement should focus on cases where racial perceptions fail to correspond to the apparent facts about the racial identities of victims of discrimination. Rather, the point is just that antidiscrimination law is (among other things) a safeguard against racial discrimination, and racial discrimination is a response to racial perceptions. So in order for antidiscrimination law to be effectively enforced, it needs data that tracks those perceptions.

The Identity-Recognition Method

One possible objection to the argument I have made so far, in favor of the social perception method, is that my focus on civil rights enforcement and antidiscrimination misses some important functions of racial and ethnic data that are tied to personal identity, rather than the external perceptions of others. In the 1990s, due in large part to pressure from multiracial advocacy groups, the census began to be perceived as a forum for “self expression,” in addition to a vehicle for data collection. Multiracial advocacy groups framed their demands for a “multiracial” option on the census form in terms of the right to express their own identity, and the right to have that identity recognized. Some Latino and Arab-American advocacy groups have framed demands for their own “racial check boxes” in similar terms.

This potential guiding value strongly supports the substantive (rather than methodological) conclusion I defend later in this paper—namely, that the U.S. government ought to effectively treat Latinos as a racial group for the purposes of data collection. The Census Bureau’s recent experiments showed that combining the “ethnicity” and “race” questions would almost completely eliminate the tendency for Latinos to check “some other race” option, reducing the frequency of that response from close to 40% to almost nil (Compton et al., Reference Compton, Bentley, Ennis and Rastogi2013, p. 73). If it is important to make sure that people are seeing themselves in the racial categories used on government survey forms, then that supports combining the “race” and “ethnicity” questions. Nonetheless, I argue against taking identity recognition as a guiding aim for racial data collection here.

We can distinguish two potential reasons why data-tracking how members of the polity identify themselves, rather than how they are perceived, could be important. First, we might think doing so is intrinsically valuable. Wendy Roth (Reference Roth2013) provides one such argument: “Allowing the data to serve this function,” she tells us, “provides identity groups with cultural recognition and a sense of belonging in a polity” (p. 1293). Second, we might think that data tracking survey respondents’ sense of racial self-identity would be more instrumentally valuable for certain kinds of public policy applications than data that tracks how people are racially perceived by others. Both of these ideas are misguided, however.

The goal of recognizing identity groups in racial data collection could conflict with the goal of trying to capture how people are racially perceived—given that many people racially identify themselves in ways that diverge from how others perceive them. If we think both aims are worth pursuing, how do we weigh them against each other where they conflict? Answering that question demands a cost-benefit analysis.

There are more effective ways to give identity groups a sense of cultural recognition and belonging in the polity than designing survey forms (especially forms that are only distributed once every ten years) with that in mind. For example, states, counties, and cities might tailor public school curricula to the history of a given identity group, or recognize figures, events, or traditions associated with an identity group through public holidays or festivals.

Agencies responsible for the enforcement of civil rights and antidiscrimination law have no substitute for accurate racial demographic data, on the other hand. Given that identity-recognition can potentially undermine the accuracy of social perception-based data, it makes sense to prioritize the latter in its system of racial data collection, at least if the value of the former is understood in terms of identity groups’ sense of cultural recognition or belonging in the polity, which can be achieved through other avenues outside of that system.

There are some public policy applications where one might think data tracking individuals’ sense of personal identity would be more instrumentally valuable than data tracking how others perceive them, however. Perhaps the most plausible of these potential applications are race-based affirmative action in the wake of the 1978 Regents of the University of California v. Bakke decision; and race-conscious legislative districting.

The Bakke decision entrenched a “diversity”-based rationale for affirmative action in higher education. The goal of affirmative action, per this rationale, is to promote a “robust exchange of ideas.” Racial diversity is taken as a means to this end, and race, as such, is taken as a proxy for knowledge, belief, or perspective. Public universities, for example, have a “compelling state interest” in a racially diverse student body on this rationale, because such a student body is thought to promote a more robust exchange of ideas than a racially homogenous student body would.

There is no single dominant, legally entrenched rationale for race-conscious legislative districting in the way that there is for race-based affirmative action. But defenders of race-conscious districting see the aim of the practice as empowering minority voters. According to some conceptions of voting power, we can measure the extent to which a voter (or group of voters) is “empowered” by looking at one or more of the following factors: (1) the likelihood that their vote(s) will be decisive; (2) the likelihood that their vote(s) will be among those necessary for the winning candidate to win; (3) the likelihood that their candidate of choice is elected; or (4) the percentage of the winning vote total that their votes constitute. If voting power depends on any combination of these four factors, then minority voting power depends fundamentally on the percentage of voters in any given district who vote the same way as members of the relevant minority group, rather than the percentage of voters in the district who are members of that group, or whether minority candidates are elected to office. Empowering minority voters, according to the various conceptions of voting power we could derive from these four criteria, thus demands data that can help district-drawers predict future voting patterns. So, it makes sense to think that the kind of racial demographic data most useful for this purpose will be data that is a good proxy for voting behavior.

Both of these applications appear on their face to demand data that tracks some aspect of people’s inner lives—their knowledge, beliefs, perspectives, or political preferences—rather than their external or “ascriptive” characteristics. It seems plausible to think that these aspects of our inner lives are more closely connected to our personal identities than they are to our external characteristics, or how others perceive us. As such, one might think that these public policy applications call for demographic data that captures the way people racially identify themselves, regardless of how they are racially perceived by others.

There are two problems with this line of argument, however. First, it is an open empirical question whether our knowledge, beliefs, and political preferences are more closely tied to the way we racially self-identify than they are to how others identify us. It is also quite plausible (and certainly possible) that those aspects of our inner lives are more closely connected to how others perceive us than how we self-identify. More research is needed in this area. Second, even if the connection between our inner lives and our personal identities is stronger than the connection between our inner lives and how we are perceived by others, taking this as a reason to focus the design of our racial data collection tools on capturing self-identification would miss the reason why we ought to collect racial data in the first place, rather than data that directly captures the relevant aspects of our inner lives.

Take the case of race-conscious legislative districting first in this regard. We can accept that (1) the goal of the practice is minority voter empowerment; (2) minority voting power is determined by the percentage of voters in any given district who vote the same way as members of the relevant minority group; and (3) racial self-identification is a better proxy for voting behavior than how one is racially perceived by others. But it does not follow that data-tracking people’s personal sense of racial identity would be more instrumentally valuable for the purpose of race-conscious districting than data-tracking how people are racially perceived by others.

This becomes clear when we consider more carefully what we mean by “minority empowerment,” as the aim of race-conscious districting. What defines the relevant minority groups that defenders of race-conscious districting want to empower though this process? The answer seems simple—race. Race-conscious districting has never been a tool for empowering political minorities in general; that is, it is a tool for empowering racial minorities. And there is longstanding bipartisan agreement that the purpose of the Voting Rights Act of 1965—the main statutory basis for race-conscious districting—was to counteract historical patterns of racial discrimination (Canon Reference Canon1999; Shelby County v. Holder, 2013; South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 1966). If we think of “minority empowerment” as counteracting historical patterns of discrimination, then the minority groups we would want to empower through race-conscious districting are those that have been historically discriminated against. These groups are defined by how they are perceived by others, not by how they self-identify, since racial discrimination is a response to perceptions of racial difference.

Consider the affirmative action case now. If the rationale for affirmative action in higher education were simply to promote the “robust exchange of ideas” in the classroom setting, then as Elizabeth Anderson (Reference Anderson2002) argues, “schools should select students directly for the ideological diversity they can be expected to bring to the classroom, rather than use race as a crude proxy for this” (p. 1221). But it is a mistake to identify the educational benefits of racial diversity in higher education with these purely academic goals. As Anderson (Reference Anderson2010) notes, if that were the only constitutionally acceptable rationale for the affirmative action, then it would be hard to see why the practice could be justified outside of liberal arts classrooms—for example, in mathematics and engineering, or in technical professions. “In principle, race should figure no more than other background factors that affect a person’s ideas and perspectives, such as belonging to a religion that is a tiny minority in the U.S., having lived abroad, or having grown up on a farm” (Anderson Reference Anderson2010, p. 142).

A racially diverse student body helps to promote a more practical kind of knowledge outside of the classroom, however; it helps citizens from otherwise segregated groups get to know one another, and learn how to live together as equals. Because K-12 schools in the United States are so racially segregated, “Colleges and universities provide a nearly unique opportunity for many middle-class Americans to learn how to live in integrated settings” (Anderson Reference Anderson2002, p. 1223). The kind of epistemic diversity that members of under-represented racial groups bring to a college or university campus comes from the ways that racial segregation and stigmatization shape their experience, not from a self-chosen identity or perspective. On this understanding of diversity, race is not understood as a proxy for cultural or ideological difference; rather, it is “a proxy for personal knowledge of what it is like to live as and be treated as a member of one’s race” (Anderson Reference Anderson2010, p. 142). And that depends fundamentally on how one is racially perceived, rather than on how one racially self-identifies.

So there are two reasons data collection methods should be designed to give the goal of enforcing civil rights and antidiscrimination law much more weight than the goal of recognizing identity groups, where the two conflict. First, even if it is intrinsically important to provide identity groups with a sense of political or civic recognition, we can do so outside of our data collection efforts; but we have no substitute for accurate data on how people are racially perceived, which is necessary for antidiscrimination and civil rights enforcement. Second, even public policy applications that seem to call for data that tracks aspects of our inner lives—our knowledge, perspectives, or preferences—are better served by data that captures how others racially perceive us, than data that captures how we self-identify.

The Biomedical Method

The Office of Management and Budget has recognized for decades that data on the country’s racial and ethnic makeup will be used for research in the health sciences. During the process of revising its system of racial categorization for federal data collection in the mid to late 1990s, the OMB made repeated reference to the rationale that various proposals to add racial categories to the system of classification would be unhelpful because the groups in question were “too heterogeneous for health research” (OMB 1995; 1997).Footnote 6

Some research in population genetics appears to support the current OMB system of racial categorization. The ability to investigate genetic causes of intergroup health disparities depends in part on having data on genetically clustered human subgroups. Latinos do not form such a group (Risch et al., Reference Risch, Burchard, Ziv and Tang2002). The current OMB designated racial groups do, however, match up very well with the genetically clustered groups identified by various researchers in population genetics (Spencer Reference Spencer2014). Despite Richard Lewontin’s (Reference Lewontin1972) well-known finding that just 5%–15% of genetic variation occurs between continentally-defined groups, and that the vast majority of human genetic variation occurs within such groups, a number of prominent contemporary medical scientists argue that what genetic variation does exist between those groups could potentially be of deep etiological and clinical significance (Burchard et al., Reference Burchard, Ziv, Coyle, Gomez, Tang, Karter and Mountain2003; Risch et al., Reference Risch, Burchard, Ziv and Tang2002). Risch and colleagues argue that “the greatest genetic structure that exists in the human population occurs at the racial level” (2002, p. 4). “Effectively,” they tell us, “these population genetic studies have recapitulated the classical definition of races based on continental ancestry—namely African, Caucasian (Europe and Middle East), Asian, Pacific Islander (for example, Australian, New Guinean and Melanesian), and Native American” (Risch et al., Reference Risch, Burchard, Ziv and Tang2002, p. 3). Those five categories are more or less identical to the current OMB racial categories.

If Latinos were treated as a racial or quasi-racial group in federal data collection efforts, it seems logical, as such, that this could potentially disrupt the usefulness of that data for genetics-oriented research in the health sciences. Instead of self-identified Latino respondents having to identify with one or more of the OMB designated racial groups, which correspond with genetically clustered human populations, they could (and likely would, as the Census Bureau’s Alternative Questionnaire Experiment (AQE) shows) simply identify as Latino. This could hypothetically leave health science agencies that rely on federal government data without any information about where Latinos fit into genetically clustered population groups.

One response to this worry, which has strong support in many parts of the public health and medical science community, is to argue that the social costs of conducting health research on genetic differences between racial groups, and of catering the government’s demographic data collection to that kind of research, outweigh the benefits.

Take one illustrative example of the kind of normative considerations that could make research on cross-racial genetic differences in disease susceptibility of limited value for public health administration. As Kaufman and Cooper (Reference Kaufman, Cooper, Whitmarsh and Jones2010) note, sickle-cell trait is “a condition that many would consider a paradigmatically racial trait” (pp. 190-191). According to various surveys, around 250 out of every 100,000 U.S. Whites have sickle-cell, compared to 7,000 of every 100,000 U.S. Blacks and just 100 of every 100,000 U.S. Asians. Latinos differ regionally with respect to the prevalence of sickle-cell, with those in the western states having only slightly higher rates of the trait than Whites, and those in the eastern states having rates approaching those of Blacks.Footnote 7 Since non-Blacks are so much less likely than Blacks to have the trait, race-specific screening of infants has often been suggested as an efficient use of scarce medical resources. But in light of the high cost of missing a true case of sickle-cell trait in, for example, a White or Asian infant, health agencies have by and large recommended universal screening for all newborns. These policy decisions need to weigh the risk of a child with sickle-cell trait going undetected against the cost of administering sickle-cell tests to White and Asian children unlikely to have the trait. So while it is conceivable that race-specific medical interventions might sometimes be warranted, the fact that some racial groups are more likely than others to be susceptible to some particular disease or condition does not by itself tell in favor of such arrangements.

But regardless of whether the benefits of health science research on genetic differences in disease susceptibility ultimately outweigh its costs, the goal of providing data that is useful for that research is irrelevant to how the U.S. government should categorize Latinos, given the way that Latinos tend to answer survey questions about their race.

Medical scientists have found that “…for many applications in epidemiology, as well as for assessing individual disease risks, self-reported population ancestry likely provides a suitable proxy for genetic ancestry” (Rosenberg et al., Reference Rosenberg2002, p. 2385). But recent population structure analyses show that this is markedly not the case for Latinos (Manichaikul et al., Reference Manichaikul, Palmas, Rodriguez, Peralta, Divers, Guo and Chen2012). The vast majority of self-identified Latinos who report an OMB-designated race identify as White, and White alone, even though every major Latino ethnic group in the U.S. has significant Native American or African ancestry (Ennis et al., Reference Ennis, Rios-Vargas and Albert2011; Manichaikul et al., Reference Manichaikul, Palmas, Rodriguez, Peralta, Divers, Guo and Chen2012).

In Manichaikul and colleagues’ recent study (2012), Cuban participants had the highest proportion of “Caucasian” ancestry at the K = 3 population level—73%. Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, South Americans, and Central Americans had just 47%, 62%, 50%, 50%, and 37% Caucasian ancestry, respectively. The K = 4 and K = 5 analyses yielded significantly smaller proportions of Caucasian ancestry for all six of these major Latino ethnic groups. Puerto Ricans, most notably, were found to have just 18% Caucasian ancestry at the K = 5 level, compared to 62% at the K = 3 level. While Latinos who identify with an OMB race are overwhelmingly likely to say that they are White, and White alone, this is not a reflection of their continental ancestry.

Most Latino groups in the U.S. have significant proportions of Native American ancestry. On Manichaikul’s K = 3 level analysis, Mexicans had 48% Native American ancestry; Central and South Americans had 45% and 40% Native American ancestry, respectively, and Puerto Ricans had 13% Native American ancestry. Dominicans and Cubans were the only groups with less than 10% Native American ancestry, at 6% each. Yet only 1.4% of all Latinos identified themselves as Native American. Guatemalans, who make up just 1.1% of the U.S. Latino population, were the most likely group to identify as Native American, and yet even they identified that way only 3% of the time (Manichaikul et al., Reference Manichaikul, Palmas, Rodriguez, Peralta, Divers, Guo and Chen2012).

Consider also the discrepancy between the proportion of Latinos with roots in the Caribbean to identify as Black or African American, and the proportion of actual African ancestry in those groups. According to Manichaikul’s (Reference Manichaikul, Palmas, Rodriguez, Peralta, Divers, Guo and Chen2012) K = 3 level analysis, Dominicans, Puerto Ricans, and Cubans had 43%, 25%, and 21% African ancestry, respectively. Yet just 12.9% of Dominicans, 8.7% of Puerto Ricans, and 4.6% of Cubans identified as Black on the 2010 Census.

This makes the federal government’s racial data on Latinos very unlikely to be useful for health science research, and potentially even harmful. For example, in one recent study, Yang and colleagues (Reference Yang, Cheng, Devidas, Cao, Fan, Campana and Yang2011) show that relatively poor survival rates for Latino and African-American children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) are likely explained in part by genetic factors, and that children with more than 10% Native American ancestry require an extra phase of chemotherapy treatment for ALL in order to abrogate their accelerated risk of relapse.

If health science agencies take government racial data on Latinos at face value under the current system, then they could conceivably miss opportunities to employ race-targeted treatment strategies such as the one recommended by Yang’s study. Paradoxically, as such, the population genetic rationale for keeping the current system of racial data collection could potentially support overturning it. But even if the racial data gathered from Latinos under the current system is not actively misleading, it is at best useless for the purposes of health science research in genetics, since Latino survey respondents are likely to identify themselves in ways that do not even come close to matching up with their continental ancestry.

RACIAL PERCEPTIONS OF LATINOS

I have argued for three premises above:

1. Racial discrimination is a response to racial perceptions, so in order for antidiscrimination law to be effectively enforced, we need data that tracks those perceptions.

2. Capturing how people are racially perceived by one another should take priority over tracking how they identify themselves in federal data collection.

3. Treating Latinos as a racial or quasi-racial group in federal data collection efforts would not disrupt the usefulness of that data for genetics-oriented research in the health sciences and might even prevent researchers from being misled.

In the rest of the paper, I want to show how this understanding of the aims of racial data collection should guide the decision about how the U.S. federal government collects data on Latinos.

Perhaps the most obvious way to implement the goal of capturing how people racially perceive one another in general, and how people racially perceive Latinos in particular, would be to simply go back to the method of collecting racial and ethnic data by using the visual and ethnographic observations of administrative officials sent out into the community. But that way of collecting data is both impracticable and undesirable.

Going back to a system of bureaucratic racial enumeration could be potentially demeaning for survey respondents. The OMB has repeatedly recognized this. The updated standards for racial classification in 1995 declare, for example, that “Respect for individual dignity should guide the processes and methods for collecting data on race and ethnicity; ideally, respondent self-identification should be facilitated to the greatest extent possible, recognizing that in some data collection systems observer identification is more practicable” (OMB 1995, pp. 44, 692). Still, any demeaning elements of bureaucratic racial enumeration would need to be weighed against the gains that such an approach might have for the quality of the data, and thus for civil rights enforcement and federal program administration. There is no reason to think the preservation of dignity is a value that takes lexical priority over all other values at stake in demographic data collection, or that respect for individual dignity should always be preserved at any cost.

However, putting aside some serious questions about the costliness of administering and overseeing the collection of racial demographic data by agency officials, it is not at all clear that going back to a visual or ethnographic system of racial enumeration would produce more accurate data on how people in the U.S. are racially perceived. In fact, it is quite plausible that, with the right survey design principles, self-identified race would be a better proxy for socially perceived race than the trained eye of an agency official ever could be.

One reason for this is that the way we are racially perceived by others depends a great deal upon context (Saperstein and Penner, Reference Saperstein and Penner2012). Observers are likely to racially categorize the same person in more than one way depending on a huge variety of contextual factors associated with social standing and racial stereotypes. For example, having contact with the criminal justice system, even as little as a single arrest, significantly increases one’s odds of being perceived as Black, and decreases one’s odds of being perceived as White (Saperstein et al., Reference Saperstein, Penner and Kizer2014). How a person did their hair, what they were wearing, who they were talking to, what neighborhood they were seen in, or what role they appeared to have been playing at any given moment, can affect how someone else racially categorizes them.

Given that one’s perceived race is partly a matter of one’s perceived social status, cultural affiliations, and other difficult-to-measure variables, it is hard to imagine how agency officials could possibly be trained to ascertain how every person in the United States would be perceived in a meaningful range of contexts by one-time visual or ethnographic observations. There is no reliable way for officials to know the kinds of contexts any given person is likely to find themselves in, even with extensive training which, if required, would simply add to the logistical reasons to retain the current practice of collecting self-reported data. If one talks to Census Bureau enumerators, one learns that it is hard enough for officials charged with collecting even the most basic demographic information to find people at home who will answer the door!Footnote 8

Perceived vs. Self-Identified Race

For the reasons outlined above, administrative agencies must use self-reported race as a proxy for perceived race. This leaves them in somewhat of a quandary, because Americans increasingly identify themselves differently, with respect to race, from how others perceive them (Saperstein Reference Saperstein2006). This is especially true of Latinos, along with Asians and Native Americans. For example, while respondents’ self-reported race on the 2000 census matched up with interviewer-observed race on the 2000 General Social Survey over 97% of the time for those who identified as White or Black, that was true only 58% of the time for those who identified as something other than White or Black. Dominicans and Puerto Ricans, who are often perceived as Black, but who do not usually identify that way, are especially likely to experience this kind of mismatch between perceived and self-identified race (Duany Reference Duany2002; Rodriguez Reference Rodriguez2000; Roth 2010).

Regardless of whether agencies continue to collect data on Latinos separately from racial data on other groups, or move to a combined format, there is likely to be a significant proportion of the population whose self-reported racial identity fails to match up with the racial identity most people perceive them to have. There is bound to be a certain amount of erroneous data. As such, the best we can do is to try to minimize the variability between self-reported and perceived race.

To see which question format is likely to minimize that variability, we need to know how self-identified Latinos are likely to classify themselves racially on a combined-question survey, compared to how they classify themselves on the current two-question survey.

On a combined-question format survey, Latinos are more likely to identify solely as Latino, rather than as ethnically Latino and racially White. Thus, if there is a worry about the proposed change increasing the variability between self-reported and perceived race, it can only be because the combined question would induce fewer Latinos to identify as White than are perceived that way. In order for that to give us reason to favor the current two-question format, it would also have to be true that the variability between self-reported and perceived race is greater on the combined question format survey than it is on the current format. Further empirical research is needed to test this, but from what we know already, we ought to be skeptical of that possibility.

On average, Latinos are much closer to Blacks than they are to Whites on various standard measures of socioeconomic status (Brown and Patten, Reference Brown and Patten2014). One locus of this phenomenon is their overrepresentation in the American criminal justice system (Lopez and Livingston, Reference Lopez and Livingston2009; Mauer and King, Reference Mauer and King2007). People who are socioeconomically successful are significantly more likely to be perceived as White than they would otherwise be (Saperstein and Penner, Reference Saperstein and Penner2012); and involvement in the criminal justice system has the opposite effect (Saperstein and Penner, Reference Saperstein, Penner and Kizer2014).

Since almost half of the self-identified Latino respondents to the 2010 census identified solely as White on the “race” question, it is easy to imagine that there is a great deal of variability between how they are presently self-reporting their race, and how they are being perceived, given their socioeconomic characteristics and the “Blackening” effect of low socioeconomic status and involvement with the criminal justice system. Moving to a combined-question format would likely reduce that variability, though more empirical work is needed to be sure.

Latinos as a Racialized Group

Agencies should also consider the extent to which Latinos are collectively perceived as racially heterogeneous, or as racially homogenous. If Latinos as a group are perceived as a race, then that perception of the group may be distributed to individual members when their Latinidad becomes known, despite intra-group differences in how individual Latinos are racially perceived through the visual assessment of phenotypic features like skin color. For example, many light-skinned Latinos might be visually perceived as White on the basis of phenotypic features alone, and many dark-skinned Hispanics might visually be perceived as Black. But Latinos who might be initially classified as White or Black, on the basis of visual perceptions about their phenotypic appearance alone, might be re-classified as neither Black nor White—but as racially Latino—In contexts where linguistic or cultural cues reveal their ethnic or pan-ethnic background.

Many Latinos think of themselves as mestizo, or mixed race. Mestizo is sometimes understood to imply a mixture of White, or European, and indigenous American ancestry, and sometimes—especially in the Caribbean context—understood to imply a mixture of White/European, indigenous American, and Black or African ancestry, though the African ancestry of some Hispanophone Caribbean populations, especially the people of the Dominican Republic, has been systematically wiped from the public consciousness and mainstream historical narrative (Winn Reference Winn2005). Both Mexicans and Puerto Ricans, as groups, seem to explicitly endorse this kind of self-conception in a variety of contexts (Duany Reference Duany2002; Massey and Denton, Reference Massey and Denton1992). And that conception is borne out both in the historical record and in recent surveys of the genetic makeup of various Latino groups, including Puerto Ricans.

According to Lawrence Blum (Reference Blum2002), this tells against the idea that Latinos are a “racialized group,” or a group that is perceived as a race. Blum argues that “…because of this historical mestizaje, persons of Latin American ancestry in the United States have a wide range of somatic characteristics, which span the conventional phenotypes of paradigmatic races—blacks, Native Americans, and whites” (p. 153).

Latinos may have a wide range of somatic characteristics, but so do other groups more conventionally thought of as races—especially Blacks. Hypodescent rules, which were both socially and legally entrenched throughout much of American history, treated descendants of Black and White ancestors as Black, even if the vast majority of their ancestors were White (Davis Reference Davis2001). Those rules encoded the idea that “one drop” of Black blood was enough to taint any amount of White blood; under the one-drop rule, it took just one drop of Black blood to be unequivocally Black, regardless of one’s somatic or phenotypic appearance. Blacks, as such, also have “a wide range of somatic characteristics, which span the conventional phenotypes of paradigmatic races.” The idea of “passing” bears this out. One can “pass” as White, but passing is a kind of deception. Passing as White was never thought to be a sufficient condition for actually being White. If Blacks themselves have such a wide range of somatic characteristics and are thought of as one of the paradigmatically racialized groups, then the fact that Latinos also have a wide range of physical appearances is not reason to think they are not widely regarded as a racial group.

Some recent studies suggest that Americans (in particular, American Blacks) may no longer believe in the one-drop rule per se (Glasgowet al., Reference Glasgow, Shuman and Covarrubias2009; Roth Reference Roth2005). But they still seem to weigh any perceived Black ancestry much more heavily than perceived White ancestry in the way they classify both themselves and one another, racially (Bratter Reference Bratter2007; Hirschfield Reference Hirschfield1996; Ho et al., Reference Ho, James, Levin and Banaji2011; Khanna Reference Khanna2010). That is, Americans adhere to a scalar form of hypodescent rule. This is evidenced not just in how people with Black and White ancestry are categorized, but also in how people with White and Asian ancestry are categorized. Americans with one Asian parent and one White parent are significantly more likely to be categorized by others as Asian than as White, and significantly more likely to think of themselves that way also, though the effect is not as strong as it is for those with one Black parent and one White parent (Ho et al., Reference Ho, James, Levin and Banaji2011).

Empirical research is not completely unanimous about this, but the emerging consensus is that, despite being treated as an ethnic group on the federal census and other government survey forms, Latinos are more and more widely regarded as a racial group in their own right (Roth Reference Roth2012).

Racial Disparity Within the Latino Population

Nancy Lopez (Reference Lopez2013), among some other prominent Latino scholars and policy advocates, argues that moving to a combined question format on the census would mask intra-group differences in how Latinos are racially perceived and treated. Lopez argues that if more Latino census respondents identify solely as Latino—rather than as ethnically Latino, and racially White, Black, or Native American, as the AQE shows they would if we moved to a combined question format—then the census would fail to capture a great deal of information. Lopez uses her own family to exemplify the kind of intra-ethnic racial differences the combined question would be unable to capture:

“…[A]lthough I was born and raised in public housing in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, New York City, I share the same ethnicity as my Dominican immigrant parents and Spanish is my first language. Despite all of these cultural similarities, my father, who is light-skinned and not of discernable so-called “African phenotype,” occupies a very different racial status than my mother and me who are racialized as Black women in most circumstances in the United States and Beyond” (Lopez Reference Lopez2013, p. 429).

Lopez provides a photograph of herself with her mother and father to substantiate this claim, and it is easy to see how she and her mother would be perceived as racially different from her father.

There is a relatively longstanding body of research documenting significant social and economic inequalities between Latinos who identify as White, and those who identify as Black or “some other race” (Massey and Denton, Reference Massey and Denton1989; Stokes-Brown Reference Stokes-Brown2012). Lopez implicitly claims that government agencies ought to be sensitive to these inequalities. There is no obvious reason to doubt that implicit claim. After all, government agencies have a mandate to monitor racial discrimination regardless of the ethnicity of those being discriminated against.

In an earlier article, Kenneth Prewitt (Reference Prewitt2005) argues that the problem Lopez raises would be addressed by allowing census respondents to identify with more than one racial or ethnic label. So, respondents who identify as “White Latino” could simply check both the “White” and the “Latino” boxes on the questionnaire, while those who identify as “Black Latino” could check both the “Black” and the “Latino” boxes. This would allow federal agencies to monitor intra-ethnic racial inequalities among Latinos, Prewitt argues, circumventing the potential problem Lopez identifies.

But Prewitt’s solution fails to recognize the two things a dual Latino-White, Latino-Black, or Latino-Native American identification could indicate. The ‘Latino’ in these dual identifications could signal either an overlapping ethnic identity, or a mixed racial identity. As such, if agencies were to move to a combined question survey format, there would be two kinds of respondents who might identify as both “Latino” and as a member of one or more of the traditional OMB racial groups: those who see themselves as ethnically Latino and racially White, Black, or Native American, etc. and those who see themselves as a racial mix of Latino and some other race.

For example, the combined format would fail to distinguish between a “White Latino” person whose parents immigrated from Italy to Argentina in the mid twentieth century, and who would be physically perceived as White, and a “White and Latino” person whose father is a dark-skinned Dominican, and whose mother is a White American descendant of seventeenth century Puritan immigrants to colonial Massachusetts. One might imagine that the former would be perceived as 100% ethnically Latino, and 100% racially White, while the latter would be seen as both ethnically and racially mixed—half Latino and half White. The combined question format is unable to distinguish between these two kinds of respondents.

It is highly plausible that there might be entrenched and systematic inequalities between these differently racialized populations, both nationally and in various local regions. So the option to “mark one or more” box on survey forms cannot comprehensively address the problem Lopez identifies: that a combined format question would fail to capture racial inequalities within the Latino population.

This is a genuine cost to a combined-question survey format that must be weighed against the benefits outlined above. But, as I have argued, the disparity between how Latinos are racially perceived, and how they self-identify on surveys with a separate “ethnicity” question for Latinos, is potentially vast. And the trend toward seeing Latinos as a racially homogenous group appears to be very strong. So it is likely that these costs are outweighed by the benefits of the potential change. More empirical research is needed in order to be sure, but it should be clear in principle how one could weigh these costs and benefits against one another: by measuring the extent to which each survey format encourages or discourages divergence between self-identified and socially perceived racial group membership.

CONCLUSION

I have argued that the U.S. government’s method for collecting racial demographic data on Latinos should be sensitive to several complex normative criteria. The overarching value I defended is that the government should strive to collect data that accurately captures how respondents are racially perceived, rather than any deeper metaphysical truths about what race they really are, data on continental ancestry that is useful for genetics-driven research in the health sciences, or information about how they prefer to identify themselves. In advancing that goal, administrative agencies need to balance three subsidiary values: the ability to capture intra-group differences in how Latinos are racially perceived; accounting for the extent to which Latinos as a group are perceived as a race; and the minimization of variability between self-reported and perceived race among Latinos. We have tentative reasons to prefer a combined-question survey format, given what we know already, but there are some areas where more empirical research is needed.