INTRODUCTION

Race is a categorical and hierarchical system of classification delineating groups of people from one another. However, the bounds of racial categorization are generally recognized as permeable and capable of change such that some groups may be able to move up or down the White-imposed racial hierarchy (Omi and Winant, Reference Omi and Winant1994). White racial classification has always been situated at the top of the U.S. racial order, yet its boundaries reportedly opened and expanded to include new immigrant groups in the early twentieth century (e.g., Italians, Irish, Polish, and other Southern and Eastern Europeans, particularly Russian and Polish Jews). Upon their arrival in the United States, these groups were effectively racialized as inferior to the dominant White group and received limited access to schools, jobs, and neighborhoods (Brodkin Reference Brodkin1998; Ignatiev Reference Ignatiev1995; Jacobson Reference Jacobson1998; Restifo et al., Reference Restifo, Roscigno and Qian2013; Roediger Reference Roediger2005). The salience of these distinctions decreased as these groups distanced themselves from other marginalized non-Whites and accordingly gained greater access to social institutions. State-sponsored social programs like the New Deal provided additional opportunities for structural assimilation into dominant forms of Whiteness (Fox Reference Fox2012; Roediger Reference Roediger2005). Today, Italians, Irish, Polish, Jewish, and other Southern Europeans are regularly afforded White racial status, and such ethnic distinctions remain mostly optional and symbolic in daily life (Gans Reference Gans1979; Waters Reference Waters1990).Footnote 1

In this vein, recent scholarship has considered how the arrival of more recent waves of immigrant groups may once again alter the U.S. racial order (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2004; Hochschild et al., Reference Hochschild, Weaver and Burch2012; Horton et al., Reference Horton, Branch, Hixson, Reynosa and Gallagher2008; Lee and Bean, Reference Lee and Bean2004; Michael and Timberlake, Reference Michael, Timberlake and Gallagher2008; Murguia and Forman, Reference Murguia, Forman, Doane and Bonilla-Silva2003; Roth Reference Roth2012; Stokes-Brown Reference Stokes-Brown2012). Some suggest that the increasing number of immigrants from Latin America and Asia could challenge the majority White-dominated society. Demographers and the popular press have noted that within the next couple of decades, the racial landscape will change such that Whites will no longer make up a majority of those living in the United States. If true, this could mark the first time in recorded history that the United States would be majority non-White. However, some researchers argue that Whiteness may once again open up and welcome new immigrants as members of the majority race (Gans Reference Gans and Lamont1999; Lee and Bean, Reference Lee and Bean2007; Warren and Twine, Reference Warren and Twine1997; Yancey Reference Yancey2003). In Who Is White, a key monograph extending this line of argument, George Yancey (Reference Yancey2003) writes, “The current predictions about whites becoming a numerical minority are wrong not because of incorrect assessments of the growth of racial minorities, but because the definition of who is white is not static” (p. 3). Yancey predicts that immigrants from Latin America and Asia will undergo a process of Whitening whereby boundaries of Whiteness will expand to include them. Concurrently, he argues that members of these once-minority groups will welcome a new dominant racialized position. If this argument holds true, popular racial demographic projections will prove grossly inaccurate, and the Whitening of new immigrant groups may help to sustain White racial dominance, especially over Blacks in the United States.

Latina/os are particularly important for understanding potential transformations to the racial order, because they are the largest non-White ethnoracial group in the country. Latina/os also exhibit a great deal of social-class and phenotypic diversity that can help to elucidate distinct forms of racial boundary change. With the transformation of racial boundaries in mind, recent research has analyzed where and how Latina/os currently “fit” in the U.S. racial order (Frank et al., Reference Frank, Akresh and Lu2010; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2008; Roth Reference Roth2012). Some researchers have pointed to the importance of traditional indicators of assimilation as evidence that Latina/os may be integrating into Whiteness (Yancey Reference Yancey2003). Others have closely considered how Latina/os view themselves in relation to the existing racial order by asking about their levels of social distance from Whites, Blacks, and Asian Americans (Marrow Reference Marrow2011; Murguia and Forman, Reference Murguia, Forman, Doane and Bonilla-Silva2003; Yancey Reference Yancey2003). Still others have focused primarily on how Latina/os self-identify on social surveys and the U.S. Census (Golash-Boza and Darity, Reference Golash-Boza and Darity2008; Stokes-Brown Reference Stokes-Brown2012).

Notably, though, where and how Latina/os fit in the racial order is informed by both individual choices about racial identification and how Latina/os are commonly racially classified by other Americans (Roth Reference Roth2012). While traditional indicators of assimilation, self-reports of social distance, and racial identification help to inform future projections of Latina/o Whitening, they do not fully consider the dynamic and mutually defined nature of racial categorization. As Richard Jenkins (Reference Jenkins1994) argues, racial group membership is a product of both internal definitions and external definitions. Internal definitions (or self-categorization) can provide information about how individuals perceive themselves vis-à-vis others. Yet racialized experiences like interpersonal discrimination or interactional elements of White privilege are most likely influenced by external categorization (i.e., how one is racially perceived) and the concomitant social-status appraisals associated with that categorization. In other words, the experience of Whiteness and its associated privileges may be at least as influenced by external definitions of race as they are by internal definitions.

Therefore, in order to examine if and how Latina/os may eventually “become White,” it is worthwhile to consider not only the conditions by which Latina/os self-identify as White, as previous research has already considered (Frank et al., Reference Frank, Akresh and Lu2010; Golash-Boza and Darity, Reference Golash-Boza and Darity2008; Michael and Timberlake, Reference Michael, Timberlake and Gallagher2008; Stokes-Brown Reference Stokes-Brown2012), but also the conditions under which Latina/os report being regularly perceived as White by other Americans (Gans Reference Gans2012). An empirical analysis of how Latina/os are racially classified by a wide variety of other U.S. adults has yet to be conducted with a nationally representative survey because such data does not yet exist.Footnote 2 However, this article examines an important and related notion: how many Latina/os report being perceived as White by other Americans and also analyzes the physical, socioeconomic, and cultural characteristics of individuals who report experiencing this aspect of Whitening.

Many researchers have attempted to predict the conditions under which some (or all) Latina/os might eventually be perceived and treated as White in the United States (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2004; Gans Reference Gans and Lamont1999; Haney López Reference Haney López2006; Lee and Bean, Reference Lee and Bean2007; Warren and Twine, Reference Warren and Twine1997; Yancey Reference Yancey2003). However, none of these predictions have been corroborated by data on how Latina/os are racially classified by others. This article serves as the first known empirical study with nationally representative data to examine variation in Latina/os’ reports of White racial categorization by other Americans. These analyses will be informative for contemporary research on racial boundary transformations, Latina/o racial classification, and for literature on the changing racial order in the United States.

It is plausible that a substantial portion of Latina/os already report that they are commonly perceived as White by other Americans. If true, we might surmise that the White-Latino boundary is already very porous. As with phenotypically ambiguous Eastern European Jewish immigrants before them, this could indicate that Latina/os’ varied phenotypical characteristics are beginning to be ignored by other Americans when making racial attributions (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008). If a majority of Latina/os report that they are perceived (and presumably treated) as White by other Americans, independent of skin tone, hair color, or eye color, this would be a strong signal that widespread Latina/o Whitening is already occurring (Gans Reference Gans2012). But if only Latina/os with high-socioeconomic-status levels are perceived as White, that might indicate that Whiteness is in large part defined by social class. If true, this would support previous research on how class and social status may be central to processes of racial categorization (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2004; Saperstein and Penner, Reference Saperstein and Penner2010). It could also be that Latina/os commonly self-identify as White, but they are not perceived as White by others, illustrating an asymmetrical consensus over how Whiteness is defined (Frank et al., Reference Frank, Akresh and Lu2010; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008).

BOUNDARY TRANSFORMATIONS?

In contemporary scholarship there are two primary approaches to examining where Latina/os currently fit in the U.S. racial order. The first approach relies on traditional measures of assimilation like interracial marriage and residential segregation among Latina/os. These measures generally indicate less social separation between Latina/os and Whites than between Blacks and Whites (Qian and Lichter, Reference Qian and Lichter2007). Recognizing differences in these assimilation rates, some scholars argue that Latina/os are on a trajectory of assimilation very similar to Southern and Eastern European immigrants of the early twentieth century (Yancey Reference Yancey2003). Yancey (Reference Yancey2003), for example, predicts that in time, the “Whiteness” of Latina/os will seem as natural as the “Whiteness” of Italian or Irish Americans. Other scholars are more cautious. Richard Alba and Victor Nee (Reference Alba and Nee2005), for example, argue that while Latina/os are assimilating, redefinition of the entire group as White is unlikely. Likewise, Tomas Jiménez (Reference Jiménez2008) argues that persistent immigration from Latin American countries may serve to reinforce the boundary between Whites and Latina/os. Most recent research on Latina/o assimilation indicators illustrate stalled residential integration with Whites and decelerated rates of Latino/White intermarriage, particularly among second-generation Latina/os (Lichter Reference Lichter2013; Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Carmalt and Qian2011). Third-generation Latina/o marital assimilation rates are substantially lower than they were for Eastern Europeans who came to be recognized as White (Feliciano Reference Feliciano2001). If one recognizes these traditional notions of assimilation as indicators of Latina/o Whitening, there is inconclusive evidence that such processes are unfolding.Footnote 3

The second major approach to examining where Latina/os fit in the racial order has been to analyze how Latina/os identify racially on the U.S. Census and other social surveys that exclude a Hispanic/Latino racial option (Darity et al., Reference Darity, Dietrich and Hamilton2001; Frank et al., Reference Frank, Akresh and Lu2010; Golash-Boza and Darity, Reference Golash-Boza and Darity2008; Stokes-Brown Reference Stokes-Brown2012; Waterston Reference Waterston2006). Since 1969, the U.S. Census classification system has separated questions about Hispanic/Latina/o origin and racial identification.Footnote 4 After asking if respondents are of “Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin,” those who answer in the affirmative are asked to choose the race that best describes them (White, Black, specific Asian nationalities, specific Pacific Islander nationalities, or American Indian/Alaska Native). There is, however, an opportunity to opt out of this racial classification system by choosing “other.” Self-categorization as “other” is common among Hispanic/Latino-identifying respondents, presumably because there is no Hispanic/Latino racial box to check.

According to the 2010 U.S. Census, nearly 40% of Latina/os identified racially as “other,” in the face of explicit instructions stating, “For this Census, Hispanic origins are not races.” Thus, self-classification indicators suggest that many Latina/os do not perceive of themselves as “becoming White,” but, in stark contrast, as favoring a racial order that recognizes them as a distinct racial group (Frank et al., Reference Frank, Akresh and Lu2010; Logan 2003; Michael and Timberlake, Reference Michael, Timberlake and Gallagher2008; Roth Reference Roth2012). However, it is also the case that 53% of Latina/os racially classified as White (Ennis et al., Reference Ennis, Rios-Vargas and Albert2011). According to some researchers, high rates of White classification could be an indication that Latina/o Whitening is occurring for significant subsets of the Latina/o population (Waterston Reference Waterston2006). Still, other scholars researching Latina/os’ racial identification choices have found that skin tone is significantly associated with identity selections. Latina/os with lighter skin tones are more likely to self-identify as White, while those with darker skin tones are more likely to self-identify as “other” or Black (Golash-Boza and Darity, Reference Golash-Boza and Darity2008). These results suggest that a more complex Whitening process may be occurring, and that it is largely influenced by phenotypic characteristics.

Clearly, measuring racial boundary change is a methodological challenge (Kim Reference Kim2007; Loveman and Muniz, Reference Loveman and Muniz2007). Rather than focus on rates of traditional assimilation indicators or rely solely on measures of self-identification to analyze previous predictions about Latina/o Whitening, this article examines the conditions under which Latina/os self-classify as White and report being perceived as White by others. By analyzing the physical, social, and cultural characteristics of Latina/os who report that they are commonly perceived as White today, it may be possible to distinguish multiple pathways through which Latina/os could potentially be recognized as White in the future.

WHO IS PERCEIVED AS WHITE? PHENOTYPICAL, CULTURAL, AND SOCIOECONOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

As previous research illustrates, many Latina/os recognize that whether or not they are perceived as White can influence important elements of daily life (Haney López Reference Haney López2006; Roth Reference Roth2012; Vasquez Reference Vasquez2010). So under what conditions do Latina/os report these experiences? Are they based primarily on how one appears phenotypically?

Skin tone is often the only physical feature analyzed in studies of how Latina/os racially classify themselves (Frank et al., Reference Frank, Akresh and Lu2010; Golash-Boza and Darity, Reference Golash-Boza and Darity2008). Is the White-Latino boundary then permeable only for individuals with a light skin tone, or do other physical features also play a role in Whitening? When making racial attributions, in addition to skin tone, people also tend to key in on hair color, eye color, and, to a slightly lesser extent, hair texture (Brown Jr. et al., 1998). Given the wide variety of phenotypic characteristics within and between different Latina/o groups, it will be worthwhile to consider whether alternative phenotypical characteristics are associated with White classification. If it is only individuals with definitively “light” phenotypic characteristics who report being perceived as White, we might gather that in terms of phenotype, the White-Latino boundary remains mostly rigid, and that Whiteness is not currently expanding to include large numbers of Latina/os.

But it is also crucial to examine nonphysical features. Perhaps it is not phenotype but cultural factors that primarily inform which Latina/os report external Whitening. Along these lines, generational status and language proficiency may yield influence for internal and/or perceived external racial categorization as White. Reanne Frank and colleagues (2010) found that among new Latina/o immigrants, those who had spent more time in the United States and those who were English-proficient were more likely to eschew federally mandated racial categories by neglecting to answer a racial classification question that did not include a Hispanic or Latina/o option in the 2003 New Immigrant Survey. Frank and colleagues (2010) argue that Latina/os with greater exposure to U.S. society are challenging traditional racial lines. Tanya Golash-Boza and William Darity (Reference Golash-Boza and Darity2008) report similar findings: bilingual and non-Spanish-speaking respondents to the 1989 Latino National Political Survey were more likely to self-identify as “other” over “White.” Interestingly, the Whitening hypothesis suggests that the opposite should be occurring: over time, immigrant groups should be more likely to claim Whiteness. In order to further examine potential Whitening processes, it will be worthwhile to consider if these cultural indicators (i.e., language proficiency and ancestral ties to the United States) relate to reports of external Whitening in the same ways that they relate to self-classification as White.

Additionally, a growing strand of research suggests that the relationship between race and social status may be reciprocal. While race has clear implications for shaping social status, social status concurrently plays a role in shaping the race that individuals are perceived as (Saperstein and Penner, Reference Saperstein and Penner2010, Reference Saperstein and Penner2012). Though illuminating, this strand of research has focused almost exclusively on the traditional Black/White dichotomy and has not considered racial boundary change among Latina/os or other immigrant groups. Rather, research on Latina/o Whitening has focused primarily on contexts outside of the United States (Golash-Boza Reference Golash-Boza2010; Schwartzman Reference Schwartzman2007). For example, Edward Telles (Reference Telles2004) finds that in Brazil, socioeconomic status influences Whitening, but primarily for those people who are phenotypically ambiguous. Absent clear visual cues as to how to racially categorize a person, Telles found that survey interviewers take socioeconomic status into consideration when racially classifying respondents. Interviewers classified highly educated respondents as “Whiter” than the same respondents classified themselves (Telles Reference Telles2004).

Herbert Gans (Reference Gans2012) predicts that as phenotypic variation increases in the United States, a similar process may unfold whereby people will look to class and other non-phenotypical indicators to make racial attributions. This may be currently true of Latina/os who have a diverse array of phenotypic characteristics. However, because most surveys have only measures of self-identified race, U.S.-based scholarship has considered only whether or not socioeconomic status influences racial self-identification for Latina/os and has produced mixed findings (Golash-Boza and Darity, Reference Golash-Boza and Darity2008). To further examine Latina/o Whitening, this study will examine if education and household income are associated with reports of external Whitening. Testing Gans’ (Reference Gans2012) hypothesis about the relationship between class and phenotypic ambiguity, this study will also investigate this relationship across different sets of phenotypic characteristics. Specifically, analyses examine how socioeconomic status is associated with perceived Whiteness for Latina/os with consistently “light” phenotypical features and those with consistently “dark” phenotypical features. This will provide an additional test of whether or not socioeconomic status is associated with Latina/o Whitening in the United States, and whether or not this process may be expedited for particular groups of Latina/os.

In summary this article extends research on supposed Latina/o Whitening by examining the frequency and conditions under which Latina/os in the United States self-identify and report being perceived as White. Though central to scholarship and previous predictions regarding Latina/o Whitening (Warren and Twine, Reference Warren and Twine1997; Yancey Reference Yancey2003), data limitations of national surveys have precluded such analyses. However, a recent national survey, the 2006 Portraits of American Life Study (Emerson and Sikkink, Reference Emerson and Sikkink2006), includes all of the aforementioned information regarding physical racialized cues, indicators of socioeconomic status, and also asks respondents directly about personal racial identity and external racial ascription.

DATA AND METHODS

For this study, I use data from the initial and only currently available wave of the 2006 Portraits of American Life Study (PALS), a nationally representative survey of 2610 non-institutionalized, English- or Spanish-speaking civilian households in the contiguous United States. Interviews were primarily conducted face-to-face but also included audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) for more sensitive questions about deviant and private behaviors. The survey yielded an 83% contact rate, an 86% screening rate, and an 82% cooperation rate, for an overall response rate of 58% (.83 x .86 x .82). Specific details about the study design can be found in an article authored by Michael Emerson and colleagues (2010). One of the key advantages of this study is the oversample of Latina/os (N=520). The PALS dataset is particularly suited for these analyses because it is the only nationally representative study that asks respondents if other Americans agree with their personal racial identity. According to Mary Campbell and Lisa Troyer (Reference Campbell and Troyer2011) this type of measure is a significant improvement over traditionally used measures of survey interviewer-respondent incongruence that likely underestimate experiences of racial contestation due to background information bias on behalf of the interviewers. I utilize multiple imputation procedures to manage missing data for these analyses.Footnote 5 Respondents who self-classified as “mixed race” are not included in these analyses.

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables in this study derive from multiple questions in the PALS survey that ask about racial self-classification and perceived external racial ascription. Early in the survey interview, respondents were asked, “What race or ethnic group do you consider yourself? That is, are you White, Black, Hispanic, Asian American, Pacific Islander, American Indian, or of mixed race?” Similar to the federally defined racial categories in the U.S. Census, self-identified Hispanics were then asked if they consider themselves to be “White, Black, Asian, American Indian, or something else.” Much later in the interview self-identified Hispanic/Latina/o respondents were asked, “Earlier you told us that you are Hispanic. Do you think other Americans would say that you are Hispanic or something else?” Response categories included “Hispanic,” “something else,” “varies,” and “doesn’t matter.” This measure was recoded into a dichotomous variable to represent a contested Latina/o identity when 1=“something else.” Contested Latina/os were then asked an open-ended follow-up question inquiring which race they are perceived as. This measure was coded so that any self-identified Latina/o respondent who is perceived as “White,” “Anglo,” “European American,” or other labels referring to the same is scored as a 1, while all other self-identified Latina/os are scored as a 0. A key strength of this measure is that it does not rely solely on one person’s classification of the respondent, but rather, on the respondent’s perceptions of how he or she is generally perceived by a wide swath of other Americans.

Independent Variables

According to previous research, skin tone, hair, and eyes are among the most important features for making racial attributions (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Dane and Durham1998). An additional advantage of the PALS data is that it includes a battery of questions on racial classification as well as racialized cues such as hair texture (scored 1–5, from “fine” to “thick”) and eye color (1=black/brown; 0=all other colors). Moreover, upon the completion of the surveys, interviewers were asked to identify the skin tone, hair color, and hair curl of respondents. In these analyses, skin tone is scored from 1–4, ranging from light to medium brown/dark. Hair color is scored from 1–6, with higher scores representing darker shades. Hair curl is scored from 1–4, covering a wide range of hair types including “straight,” “slightly curly,” “very curly,” and “tight and curly” respectively. The PALS data also include measures of height and weight. Height is measured in inches and weight in pounds. In order to assess how cultural factors may be associated with self-identified and perceived Whiteness, this study examines the potential influences of generational status and familial language use. The generational status measure derives from a question asking whether or not both the respondent’s parents were born in the United States (1=yes, 0=no). Language use was measured by whether or not either of the respondent’s parents are bilingual (1=yes; 0=no).

This study also examines the potential influence of socioeconomic status. In particular, respondents were asked about their household income as well as the highest level of education they had obtained. Household income is a nineteen–category response variable, ranging from less than $5000 annually to more than $200,000 annually. Education is a five–category ordinal variable and ranges from less than high school to graduate degree or more.

Additionally, I control for a number of other respondent characteristics including gender (1=male; 0=female); age (eighteen to eighty and above); national origin (Mexican descent=1; all other Latina/o descent=0); and political orientation (1–7), ranging from strong liberal to strong conservative. Given that Whites tend to lean conservative (Kohut Reference Kohut2012), it is plausible that Latina/os who are politically conservative may be more likely to self-identify as White.

RESULTS

The first set of results illustrates rates at which self-identified Latina/os self-classify as White when there is not a Hispanic/Latino option. Mirroring the race question on the U.S. Census, the Portraits of American Life Study asks Latina/o-identifying respondents if they consider themselves to be “White, Black, Asian, American Indian, or something else.” Approximately 42% of respondents self-classified as White, and over 50% identified as “something else.” These results are similar to the results of the 2010 U.S. Census (Ennis et al., Reference Ennis, Rios-Vargas and Albert2011). Interestingly, however, rates of self-identification as White contrast considerably with how commonly respondents report being perceived as White by other Americans. Though over 40% self-classify as White when there was no Hispanic/Latino option, only 6% report being regularly perceived as White by other Americans. Moreover, not all who report being perceived as White actually self-classify as White. Approximately one-third of respondents who report being regularly perceived as White chose to self-classify as “other” over White when not presented with a Hispanic/Latino option. These descriptive results indicate two key insights: 1) Very few Latina/os say that they are generally perceived as White (only 6%); and 2) many Latina/os who report that they are perceived as White do not claim a White identity.

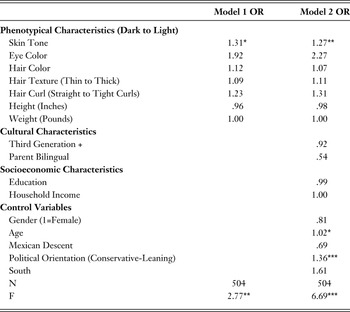

Though illuminating, descriptive statistics do not illustrate the social factors that are associated with self-classified and perceived Whiteness. Thus, Table 1 shows which physical, cultural, and social characteristics are most closely associated with self-classification as White when a Hispanic/Latino option is not available. Model 1 includes only phenotypic characteristics. Results suggest that among a multitude of commonly racialized phenotypic cues including eye color, hair color, hair texture, weight, height, and others, only skin tone is significantly associated with self-categorization as White.

Table 1. Binary Logistic Regression of White Self-Classification When Not Presented with a Hispanic/Latino Option

OR = Odds-Ratio; ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05

Model 2 includes all measures, including cultural characteristics, socioeconomic indicators, and controls. Results suggest that skin tone remains significantly associated with self-categorization as White even when controlling for a host of other racialized characteristics. Model 2 also illustrates that age and political party are significantly associated with self-classification as White. Respondents who have a lighter skin tone, who are older, and who are more politically conservative are significantly more likely to self-classify as White. Notably, income and education are unassociated with White self-classification.

Table 2 examines whether these same factors (skin tone, age, and political party) are significantly associated with respondents’ reports of whether or not they are generally perceived as White by other Americans. In Model 1 we see that skin tone, eye color, and, to a lesser extent, hair color (p<.10) are all significantly associated with reports of perceived Whiteness. Individuals with lighter skin tones, non-black and non-brown eyes, and lighter shades of hair are most likely to report being perceived as White by other Americans. Model 2 includes all measures, including cultural characteristics, socioeconomic characteristics, and controls. Again, results suggest that lighter skin tone, eye color, and hair color are significantly associated with perceived Whiteness. Model 2 also shows that Latina/os with established ancestral ties to the United States are more likely to report being perceived as White. Latina/os of the third generation and beyond have significantly higher odds of reporting that they are perceived as White than their first- and second-generation counterparts (OR: 3.274). Yet additional descriptive analyses indicate that nearly 90% of third-generation Latina/os do not report that they are perceived as White. Age is the only characteristic that remains statistically significant in both sets of analyses (Table 1 and Table 2). Interestingly, the results are in the opposite direction. Older respondents are more likely to self-classify as White when not given a Hispanic/Latino option (Table 1), but it is the younger respondents who are more likely to report being perceived as White (Table 2).

Table 2. Binary Logistic Regression of Reporting External Classification as White

OR = Odds-Ratio; ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05, +p < .10

Lastly, Model 2 also shows that socioeconomic indicators are significantly associated with whether or not Latina/os report being perceived as White after controlling for all other measures in the model. Those with higher levels of education and higher levels of income are more likely to report external categorization as White than are those with lower levels of education or income. Thus, similar to Aliya Saperstein and Andrew Penner’s (Reference Saperstein and Penner2012) finding that college education can Whiten respondents who were previously identified as Black, these results suggest that socioeconomic status may have the potential to Whiten Latina/os.

To test Gans’ (Reference Gans2012) hypothesis of whether or not the influence of income might vary by phenotype, I also analyze the probability of reporting that one is perceived as White for distinct ideal types of individuals across the income spectrum. First, I regressed the dependent variable from Table 2 on three multiplicative terms which correspond to the interaction between socioeconomic status and each statistically significant phenotypic characteristic (i.e., household income x skin tone; household income x eye color; household income x hair color), in addition to all other variables included in Model 2. Second, I set the conditions for a consistently “light” respondent (a respondent with the lightest score on skin tone; light blond, dark red or auburn, and strawberry blond; and non-black or non-brown eyes). Next, I considered a substantially “darker” counterpart based on the same list of variables (a respondent with the darkest score on skin tone, which corresponds to medium brown or darker; black hair; and brown eyes). The probability graph presented above is based on models that include statistical interactions between household income and each of the phenotypic characteristics listed above. Modeling the effects this way allows for heterogeneity in phenotype effects across household income.

Figure 1 illustrates that the probability of reporting external classification as White is low (under .3) for respondents from households that earn an annual income of $25,000 or less. According to recent estimates, approximately 30% of all Latina/o households earn less than $25,000 per year (U.S. Census Bureau 2012). Thus, it appears that low-income Latina/os may be unlikely to traverse the White/Latino racial boundary, even if they have very light phenotypical features. Notably, though, the relationship varies as income increases. For the ideal-type “light” respondent, the predicted probability of reporting that one is perceived as White increases as income increases even at very low levels of the income distribution. Yet the probability of reporting external categorization as White does not start to increase for our “dark” respondent until approximately $100,000 in annual income is reached. Furthermore it takes approximately $175,000 in household income for our ideal-type “dark” respondent to have a predicted probability of being perceived as White above .2. From these results, we can surmise that money may have the potential to Whiten Latina/os, but it would likely take drastic and unrealistic changes in income distributions for the vast majority of Latina/os who do not consistently exhibit “light” phenotypical features to start being perceived and treated as White in the foreseeable future.

Fig. 1. Probability of Perceived External Classification as White by Phenotype and Household Income

DISCUSSION

Cognizant of the racial changes occurring as a result of recent waves of immigration, Gans (Reference Gans and Lamont1999) once predicted an emerging Black/non-Black racial divide (rather than the traditional White/non-White divide) to explain the emerging U.S. racial order. Similar projections suggest that Latina/os (and Asian Americans) are Whitening or aligning with Whites and are therefore expediting the creation of a new Black/non-Black divide (Lee and Bean, Reference Lee and Bean2007; Marrow Reference Marrow2009; Sears et al., 2003; Warren and Twine, Reference Warren and Twine1997; Yancey Reference Yancey2003). However, post-SB-1070 and other immigrant-targeted policies, Gans (Reference Gans2012) has reconsidered his perspective: “…we should have realized that most Whites would strenuously reject being described as non-Blacks. For this reason, and because of the likelihood of continued White domination of the hierarchy, its description should have placed Whites at the top” (p. 272). Gans (Reference Gans2012) writes that he has now come to agree with a more complex tripartite system of White-imposed racial hierarchy akin to the one forecasted by Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (Reference Bonilla-Silva2004) and extended by Wendy Roth (Reference Roth2012). According to Bonilla-Silva (Reference Bonilla-Silva2004), a middle designation is beginning to emerge, effectively splitting the traditional Black/White poles. This middle designation is made up of medium- and lighter-skin-toned Latina/os, Asian Americans, and multiracials who he argues are being afforded honorary White status and are distinguished from Blacks and their darker-skinned counterparts. Roth (Reference Roth2012) goes on to explain that the boundary between the middle honorary White designation and the dominant White designation is relatively porous so that some individuals and groups can effectively cross racialized boundaries.

This study leads to some important conclusions about how “porous” the White/Latino boundary is by examining which Latina/os report that they can commonly cross it. Notably, I find that current perceptions of Whiteness are not entirely shaped by physical characteristics like skin tone and hair color, nor are they solely influenced by cultural traits like language. The White/Latino boundary is also influenced by socioeconomic characteristics like education and household income. Attributing socioeconomic status to Whiteness is likely informed by a present-day context of stark racial socioeconomic disparities in the United States. As Derrick Horton and colleagues (2008) argue, “Whites and by definition whiteness is the de facto standard for wealth, status and power in America” (p. 710). For example, recent federal data indicates that White households have eighteen times the wealth of average Latina/o households, and this disparity has been increasing over time (Kochhar et al., Reference Kochhar, Fry and Taylor2011). Given such stark racial and ethnic inequalities, perhaps it is unsurprising that higher levels of socioeconomic status are positively associated with Whiteness.

Of course, with only cross-sectional data one cannot make conclusive assertions about causality. It could be that the relationship between socioeconomic status and reports of perceived Whiteness runs only in the opposite direction such that those who are initially perceived as White have greater opportunities to obtain higher incomes. The probabilities illustrated in Figure 1, however, help to temper these concerns. In accordance with this alternative interpretation, findings from the predicted probability graph would suggest that phenotypically dark respondents who report being perceived as White earn much higher incomes than their phenotypically light counterparts who report the same. This reading of the results does not correspond with the vast literature on skin-tone stratification. Rather, many studies demonstrate just the opposite: that phenotypically lighter respondents earn higher incomes than those who are darker (Hunter Reference Hunter2007; Keith and Herring, Reference Keith and Herring1991). This is particularly true of Latina/os (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Telles and Hunter2000; Arce et al., Reference Arce, Murguia and Frisbie1987; Frank et al., Reference Frank, Akresh and Lu2010; Mason Reference Mason2004; Murguia and Saenz, Reference Murguia and Saenz2002; Telles and Murguia, Reference Telles and Murguia1990). Therefore, a more plausible reading of Figure 1 suggests that money can Whiten Latina/os in the eyes of many Americans, but it takes much higher incomes for Latina/os with darker phenotypical features to report that other Americans generally perceive of them as White. In this way, this study lends support to Saperstein and Penner’s (Reference Saperstein and Penner2012) research on how social status can shape experiences of race, and extends this line of thought to the case of Latina/os in the United States. Still, longitudinal data with multidimensional measures of racial classification, phenotype, and socioeconomic characteristics will go a long way toward examining if and how these processes that reinforce racial stratification may be operating simultaneously. I suspect that this is a dynamic, mutually reinforcing relationship whereby being perceived as White may provide for more opportunities to obtain income, while greater income simultaneously increases the odds of being recognized and treated as White. Future research on Latina/o Whitening would do well to consider these possibilities as paneled longitudinal data become available.

This research also illustrates that racial and ethnic boundary changes are two-sided processes that may require both personal identification with a new group as well as external validation by others. As Nadia Kim (Reference Kim2007) notes, the assumption is often made that non-Whites may have a desire to become White. Ian Haney López (Reference Haney López2006), for instance, predicts that “an increasing number of Latinos—those who have fairer physical features, material wealth, and high social status…will both claim and be accorded a position in U.S. society as fully white” (p. 153, emphasis added). Similarly, Yancey (Reference Yancey2003) proposes that discussions of whether or not Latina/os want to become White are mostly irrelevant because “…racial minority groups will usually attempt to assimilate when the majority group accepts them to a sufficient extent” (p. 135). Bonilla-Silva (Reference Bonilla-Silva2004) argues that middling members of his triracial model will embrace honorary White status and come to classify themselves as White. Based on their study of multiracials, Jennifer Lee and Frank Bean (Reference Lee and Bean2007) argue that Latinos are “more actively pursuing entry into the majority group” (p. 580) as compared to Blacks.

To date, this is the first known nationally representative study to corroborate some of these predictions about who can transcend the White/Latino boundary. In particular, this study provides support for Bonilla-Silva’s (Reference Bonilla-Silva2004) and Haney López’s (Reference Haney López2006) predictions that it will only be select Latina/os (those with light skin tones and higher levels of socioeconomic status) who are generally recognized as White by other Americans. However, this study also shows that some Latina/os who report having access to interactional elements of Whiteness (by being perceived as White) may not be particularly eager to self-classify as White. All respondents in this study self-classify as Hispanic/Latino over White when given a Hispanic/Latino racial option, and approximately one-third of those who report being perceived as White would rather self-categorize as “other” when a Hispanic/Latino option is unavailable. Thus, the results herein temper claims that Latina/os, in general, would welcome Whitening. Rather, these results lend support to assertions that the racial structure in the United States is changing whereby “Hispanic/Latino” is emerging as a salient racial category (Frank et al., Reference Frank, Akresh and Lu2010; Golash-Boza and Darity, Reference Golash-Boza and Darity2008; Roth Reference Roth2012).

CONCLUSION

This article sought to examine if Latina/os commonly self-classify and report external categorization as White—a potential indication that Whiteness is expanding to include a large and varied Latina/o population. At least three key findings illustrate how both personal racial classification and external validation of these classifications should be central to future investigations of Latina/o Whitening.

First, results suggest that over 40% of self-identified Latina/os demarcate their race as “White” when not presented with a Hispanic/Latino option. Older respondents, those with lighter skin tones, and those who are politically conservative are more likely to self-classify as White. It is plausible that if afforded the opportunity, some of these Latina/os might opt to “become White” in the ways that previous researchers have predicted. Yet it is also plausible that restricted racial options leave many Latina/os scrambling for a racial box to check on many social surveys. Over 90% of Latina/os who self-classify as White in the PALS data recognize that they are not actually perceived as White by others. With restricted options, many Latina/os appear to recognize that they may be arbitrarily choosing to identify with one inaccurate racial label over another by appealing to phenotypic or political similarities with other racial groups. In this way, social researchers who believe that White identification on social surveys is a useful indicator of societal Whitening may be giving undue credence to such choices. The vast majority of Latina/os who self-classify as White recognize that these identification choices do not match up with how they actually experience race in daily life. The Census Bureau appears to have acknowledged some of these discrepancies and may come to recognize Latina/os as an independent racial group in the 2020 Census.

Second, this study suggests that Latina/os generally report being perceived as White only if they match common indicators of Whiteness: very light phenotypic characteristics, well-established ancestral ties to the United States, and high levels of socioeconomic status. In this way, it does not appear as though the boundaries of Whiteness have expanded to include many new immigrants. Rather, it is likely that Latina/os are so diverse phenotypically, culturally, and socioeconomically that a small subset may have always exhibited traditional characteristics comparable to the dominant White group. Of course without longitudinal data, one cannot be sure. Still, the only indication that boundaries may be expanding is that some phenotypically dark Latina/os with exceptionally high levels of income report being perceived as White. In this way, the White/Latino boundary may be permeable for those Latina/os whose socioeconomic status dwarfs that of privileged Whites.

Third, results show that many Latina/os who report being perceived as White do not actually self-classify as White. While the White/Latino boundary may be permeable for a select few, this boundary is not always deliberately being crossed by those who have access. Contrary to popular projections, many Latina/os do not appear to be actively seeking Whiteness. Latino identity has codified politically and socially in ways that Irish, Italian, and early Eastern European Jewish identities likely did not. Thus, we might expect different routes to American incorporation among Latina/os than those taken by European immigrants at the turn of the twentieth century. It is plausible that Latina/os may simultaneously engage in moderate amounts of marital and residential assimilation, experience elements of racial marginalization (Telles 2008), and still seek to maintain a distinct racial/ethnic identity. Moreover, the recent and impending contentious debates over immigration and legality across the country may solidify even more the racial boundary between Whites and Latina/os.

In summary when analyzing two central indicators of racialization—self-classification and reports of external classification—it appears that only a very small subset of Latina/os today may be “becoming White” in the ways that some previous researchers have forecasted. This leaves little evidence that the boundaries of Whiteness are steadily expanding to include the vast majority of Latina/os in the United States. Of course, future studies will be necessary to consider whether or not a more diverse array of Latina/os may come to be recognized as White over time.