INTRODUCTION

One of the most important statements W. E. B. Du Bois made is that “the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line…” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1903, p. 7); a thought that continues to ring true in the twenty-first century. Race remains a critically important boundary in the United States, making the color line a central factor shaping the life chances of U. S. citizens in arenas far too numerous to list here. Although today’s biologists who study genetics have shown that race is not a useful scientific concept, the importance of a color line cannot be denied by asserting that race is a myth or social construction. Social constructions can be consequential even if not factually true. And, as Ira Berlin (Reference Berlin1998) reminds us, “the concept of race is not simply a social construction; it is a kind of social construction—a historical construction, it cannot exist outside of time and place” (p. 4).

Neither a color line nor the idea of race is a given in human experience; their origins and history are grounded in specific kinds of social relationships that appeared at certain points in time. Any color line is not an amorphous boundary such as a meteorological cold front where temperature and air pressure differentials dance back and forth within a mass of air. But a color line is similar to such natural phenomena in being fluid, dynamically changing, and shifting with the winds until it becomes a stabilized feature in people’s minds. It is when the boundaries separating groups become organized around the idea of race, fixed by some historical mechanism such as a law or legal code, that one can draw a color line in Black and White (Sweet Reference Sweet2005).

Rather than trying to resolve the debates about when the idea of race first appeared in human history, a matter that has received considerable attention, my research questions are more modest and limited to a very small part of the globe—the English colonies in the Chesapeake region of North America. There, three different descent groups from three different continents were thrown together by British colonialism into a new situation, and each had to figure out who the others were. It was upon the contested terrain around the Chesapeake Bay that the questions about who controlled the land and what kind of labor would work the land got answered, and not to the satisfaction of all involved.

The “facts” examined in this study are the Colonial Laws of Virginia which represent the views of only one of these descent groups, the English, who developed the power to name and classify others. History is written by the victorious and the data analyzed presents only one side of the complex triangular relationships. It is important to note that those views were not necessarily those of the English colonists in general, but the views of a patriarchal planter class who came to own most of the prime land in the colony of Virginia. They enacted laws to regulate the behavior of other people in ways that served their own class interests. A small group of landowners/planters who held land that was worthless without cheap labor determined the shape and course of law formation in the colony of Virginia. Their approach to governing was based on patriarchal premises modelled after a king leading a nation, a father heading a family, and an elite class in control of the body politic (Brown Reference Brown1996). There was no pretense to what we today would call democracy; the voices of women and people of color would have to wait three centuries to be heard, and only partially listened to.

SINGULAR AND OTHER TERMS OF IDENTITY

To analyze the historical aspects of a color line involves initially not invoking any reference to the concept of race; the major groups studied here are descent groups. And to focus directly on a color line emerging out of colonial legislation, a distinction between singular, dual, and multiple identities is critical.

The descent groups were different in many ways: histories, languages, religions, manners and morals, and, of course, physical appearance. By focusing on multiple bases of identity, rather than focusing on but one difference, we can trace the process by which some identities lose their salience over time in enacted law, and group boundaries are, over time, reduced to a simple dichotomy, a color line drawn in Black and White.

A singular legal identity is one that stands alone and is sufficient to identify a group or person on one side of a boundary vis-á-vis those on the other side. For example, in drawing the boundary between people who descended from some place in Europe versus other continents, the term “English” suffices; it needs no other descriptor such as free or Christian. A dual legal identity requires at least two terms to define a boundary. For example, if a law aims to distinguish English Christians from African non-Christians, two terms are necessary. Finally, if a boundary requires three or more legal identity terms it is multiple. The most common multiple identity patterns cited by past research are composites such as English, Christian, and Free versus Negro, Heathen, and Slave (Goetz Reference Goetz2012).

It is important to note that this research examines legal identities, those written in law books during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, not the personal identities of people in everyday life. The legal identity terms examined may or may not reflect the frequency with which the terms were used in everyday life by average citizens at that time. It is the legal apparatus that creates a color line or constructs the social idea of race, not informal everyday discourse (Higginbotham Reference Higginbotham1978).

LAW AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACE

This link between law and enslavement has been central for many historians of slavery. Frank Tannenbaum (Reference Tannenbaum1946) compared enslavement patterns in New World colonies of Catholic nations (Portugal and Spain) and Protestant nations (England and Holland). He showed how the presence of a legal definition of slavery in Iberia and the absence of such a legal status in English legal codes was related to a somewhat less repressive slave regime in Iberian colonies. There, the enslaved were allowed to participate in the life of the Roman Catholic Church which encouraged Christian baptism, marriage, and allowed for slaves to have some property rights and the option of self-purchase. In Virginia, by contrast, a more repressive regime developed more gradually where the enslaved were incorporated into the Church of England on a limited basis, were denied the right of marriage, were discouraged from baptism, and had no property or personal rights; African slaves became chattel owned by Europeans.

A. Leon Higginbotham (Reference Higginbotham1978) examined the legal apparatus of six British colonies, including Virginia, demonstrating how colonial law departed from English common law and was central to the creation of a degraded status for people of African descent. Rather than seeing the idea of race as an unconscious decision and gradual drift towards enslavement, with the law reflecting the wishes of the average colonist (Jordan Reference Jordan1968), Higginbotham emphasized the active, conscious intent of the planter class to control an unfree labor force.

Alejandro de la Fuente and Ariela J. Gross (Reference de la Fuente and Gross2020) also focus on legal boundaries in a comparative study of Cuba, Louisiana, and Virginia legal codes. They find more similarities than differences in these colonies, counter to Tannenbaum’s work, and view the law as defining possible paths to freedom rather than simply defining slave status. Important for the current research is their observation of the slower, more gradual development of slave law in Virginia, and the claim that by 1750 all three colonies had established slave regimes.

Although the particular issues these scholars addressed are varied, all support the proposition of a clear and necessary link between enacted law and the emergence of a color line. This study follows that emphasis on the law as central to the creation of property rights that included slaves as commodities that can be owned, traded, and otherwise used to produce and protect the wealth of the planter class.

SLAVERY IN THE COLONY OF VIRGINIA

Ira Berlin’s (Reference Berlin1998) idea of two distinct societal types, a “society with slaves” and a “slave society” aptly describes early and later patterns in Virginia. The former type has slaves doing some tasks, but they are not, as yet, the key component of the system of production, as is the case in a slave society. This distinction points to the idea that slave societies develop over time as the unfree labor of slaves comes to be the key to the production of wealth. In the early decades of the Virginia colony, European indentured workers were the main source of labor and Africans, both indentured and enslaved, worked alongside Europeans. It took many generations for a slave society to emerge in Virginia.

The slave society that the colony of Virginia became in the early to middle part of the eighteenth century was devoted to the production of wealth for some that rested on the unfree labor of others. The presence of law and its enforcement was central to a slave society’s operation. Plantation systems devoted to a single source of most wealth, in this case, tobacco, depended upon a stable supply of cheap or unfree labor. Enslavement of laborers was not possible as a “custom of the country” but rested on laws that sanctioned systematic violence, or its threat, in two arenas: (1) on the plantation itself, the free landowner could discipline those in bondage, both servants and slaves, and often used public whippings as a means of demonstrating the power of the planter class; and (2) outside the plantation in the public sphere, enacted law and its officials were there to control the possible flight of unfree labor. A purely customary system of slavery where people follow established roles containing the inequities, injustices, and violence central to how a slave society operates, is not imaginable.

Thus, in the search for the appearance of a color line I examine the evolution of “enacted law,” the claimed authority of the English to control the unfree labor of the other two descent groups: the indigenous native (Indian) population “discovered” by the English, and the African (Negro) population imported only for their labor. The initial encounters among these three groups were unstable and uncertain but eventually a social structure appeared, defined by legal codes resulting in the enslavement of both non-English descent groups (Moore Reference Moore1941).

THE ISSUE OF PRESENTISM

Looking back on collective life in centuries past means that analysis of the historical record must be sensitive to the dangers of what historians call presentism; in the words of sociologists, what C. Wright Mills (Reference Mills1940) called the danger of projecting our current vocabularies of motive onto past actions and behaviors. One cannot safely assume that people living centuries ago used words or phrases in the same way we use them today. The most important area in which caution is necessary in the present research lies in the meanings associated with the White and Black elements of a color line.

Many historians assume that the initial encounters in the Virginia colony in 1619 between Europeans and Africans were between White and Black people, terms meaningful in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. There, the English who had been relatively isolated from contact with Sub-Saharan Africans brought with them attitudes that viewed these imported “strangers” as different racial entities (Degler Reference Degler1959; Jordan Reference Jordan1968).

Theodore W. Allen (Reference Allen1994), a critic of such views suggests… “(W)hen the first Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619, there were no ‘White’ people there; nor, according to the colonial records, would there be for another sixty years” (Vol. 1, back cover). Looking back in time without the “lens of presentism” means that White was not then a current word for a person or a group of persons and had to be created. Further, the word Negro today has the sole meaning of a Black person, but we cannot assume that the word has always carried that singular meaning.

Historian James Sweet (Reference Sweet2003) argues that the idea of race developed prior to Iberian colonization of the New World and details the way the word Negro was used in the early stages of colonization. In both Spain and Portugal, the word Negro meant not only the color black and the idea of Black African descent but, more widely, simply denoted that a person was enslaved. In 1650, the Portuguese used the word Negro for a slave “regardless of skin color” and more tellingly, in Brazil, Negro was inclusive of both indigenous native slaves and African slaves (Sweet Reference Sweet1997, p. 8). Negro did not mean Black as a singular feature of an African’s identity. Such usage was present throughout the Atlantic world in which the slave trade was operating. In the words of a seventeenth century cleric while visiting Barbados and Virginia, “these two words, Negro and Slave, being by custom grown Homogeneous and Convertible; even as Negro and Christian, Englishman and Heathen are…made Opposites” (Godwyn Reference Godwyn1680, p. 36). The general import of examining multiple identities is reflected in historian Barbara J. Fields’ (Reference Fields1990) admonition to avoid the assumption “that any situation involving contact between people of European descent and people of African descent automatically falls under the heading of ‘race relations’” (p. 98).

DATA AND METHODS

To examine how a color line developed in the colony of Virginia, I carried out a case study of The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia (1619–1792), published by an act of the General Assembly of Virginia in 1809. This collection was created at that time in the interest of historical preservation because many 200-year-old original paper manuscripts were deteriorating, and some could not be transported or touched without damaging them. The collection of laws has more recently been transformed into accessible digital collections that are widely used by researchers of the colonial era. This collection of laws was accessed using two online databases: (1) The Hathi Trust Digital Library (https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009714930) and (2) Vagenweb.org (http://vagenweb.org/hening/). The Vagenweb data source was used for initial word searches and for combinations of words suggestive of a possible color line. This database is very speedy and allows for complex search statements. The Hathi Trust data source is slower but has the advantage of making searches within different time intervals more precise. Both data sources contain examples of “presentism” or “the imposition of different vocabularies” on past experience (these will be identified later) that resulted from editing the original manuscripts.

LEGAL IDENTITIES

The questions of how (by enacted law) and when (to be determined by the content of law over time) a color line was drawn between descent groups from different continents were approached by the creation of four broad analytical categories, and key words under each.

Descent

The three groups of central interest are the native “Indians” of North America, the “English” from Europe, and the “Negroes” from Africa. These terms best describe major descent groups whose relationships came to be defined by the English who developed the power to name and classify others. As noted above, history is written by the victorious and the data analyzed presents only one side of the complex triangular relationships.

Color Line/Race

Categories based on skin color as a marker of race are the most visible part of any color line. The three identity terms searched for are “White,” “Mulatto,” and “Black” when used to identify a person or a group. Uses of the terms as descriptors of natural phenomena such as a river or a tree were ignored.

The search for a color designation for Indians showed no color-related terms; consequently, some analyses exclude the English versus Indian boundary. Similarly, searches for a color gradation attached to Negroes showed nothing; nor did a search for any colored person. Apparently, the terms Indian and Negro were sufficient for legal purposes across the colonial era. This is noteworthy, suggesting that skin color was not salient in the minds of the lawmakers in making some distinctions. The fact that the Mulatto category straddles a potential color line means the Mulatto created a clear boundary problem for the political elite.

Status

The status of a person was designated by the terms “free,” “servant,” or “slave.” Much of the struggle for freedom for people of African descent revolves around these keywords and how they were related to different paths towards freedom.

The primary thrust of colonial legislation was to establish, in the language of the day, who was free to work for themselves and hire or purchase others’ labor, and who was legally bonded (required) to work for someone who was free, with servants and slaves differing in the length of the time period their labor belonged to another person.

The labor of a servant was under the control of the owner of an indenture (or contract) that specified a time interval, usually five years, within which the servant was required by English law to serve a free person. Most indentured servants were immigrants from England who contracted to work for a free person who paid the costs of their transportation to the Virginia colony, although some number of other Europeans were transported to the colony as punishment and sold as indentured workers. Also, some early arrivals from Africa were treated as indentured servants and worked through their contractual period and became free Negroes, a confounding identity category that would trouble the planter class for decades to come.

Slaves, by contrast, were legally required by Virginia law after 1662 to work for an owner for the rest of their natural lives. And, any child of an enslaved woman was condemned to that fate as well. A slave could not control his/her access to free status but could become free if the slave owner granted it. It is important to note that there was no legal provision in the laws of England for the enslavement of Indians and Africans, so the law of 1662 had to be enacted by the colony. This means there was a period from 1619 to 1662 when some Africans in the Virginia colony were treated as indentured servants rather than as slaves.

Religion

Attempting to find clear indicators for the legal religious identity of a person proved difficult. There were many possible choices of a religious boundary, but a simple dichotomy of Christian and non-Christian was used in this research. The Christian category is largely composed of members of the Church of England, the established religion of the Virginia Colony, but over the years could also include Roman Catholics, Puritans, and Quakers (although most Quakers and Puritans left the colony by 1660). The non-Christian category is a composite that is best explained by the classification operations used. The search statement language for the non-Christian category was: “heathen or pagan or savage or Jew or Moor or Mahometan or Infidel or atheist or deist.”

ANALYSIS STRATEGY

In looking for a color line, the procedure was to scan the electronic records of all of the laws of Colonial Virginia using search statements for each of the legal identities in singular, dual, and more complex forms and recording the frequency with which they appeared and the time period of the occurrence. Of course, some combinations such as English and slave were not attempted on the basis of prior knowledge. In searching for the key words within enacted laws at different time periods, I address the place and time questions raised by Berlin (Reference Berlin1998) concerning the drawing of a color line or, phrased differently, socially constructing race.

A color line was considered drawn when the boundaries between those of European versus African descent based on biological differences got codified in law; the “color line” and “race” become legal constructions. The above distinction between singular, dual, and multiple legal identities is important and introduced several questions. Do people on both sides of a color line have to think of themselves as members of a legal category based on biological variations between the groups? Probably not, because the essence of power is the ability to control others’ behavior despite resistance. So, the important question becomes: can a color line exist if those in power do not think of themselves as members of a group based on biological variations and deploy such an idea to maintain their position?

The position this research takes on that question is clearly no. A central thesis of this search for a “color line” in colonial Virginia is that only when those in power in the Virginia colony embrace the legally enacted identity of “White” as a singular identity can we conclude a clear color line has become a boundary and the social concept of race has been fully established.

Note that this thinking does not suggest that people in the colonial era did not perceive differences in color or other biological variations between descent groups. Rather, the premise is that only when skin color or other biological facts about people become the basis for a legal identity separating groups can one say a color line has been definitively drawn. Thus, the fact that the common term of Negro means black in Spanish and Portuguese but also meant slave without reference to skin color or continent of origin (Sweet Reference Sweet2003) means a color line was not constructed when the word Negro was used to define a boundary. Rather, the existence of a color line requires the dominant group to think of themselves in terms of color. In that sense, the key issue is not how Blackness is defined in law; the question is how and when the English defined their status by claiming to be White.

THE SALIENCE OF RELIGION

Most of the early settlers of the Virginia colony were citizens of England and many were fervent Christians, largely members of the Church of England that became the established religion of the colony and controlled the enforcement of moral codes. There were in the neighboring colony of Maryland a significant number of Roman Catholics who were major landowners and initially constituted the powerful political class. But whatever variety of Christian there was in the Chesapeake Bay region, the English were first and foremost Christians.

Upon initial encounters with the indigenous population, the salience of Christian identity for the English colonizers framed the way they labelled the natives—as non-Christians, savages, heathens, or pagans—and a missionary impulse of the English saw the natives as potential converts to the Christian religion. That impulse soon ended after the Indians ascertained that the English, unlike the French to the north and west, were not on their shores to trade but wanted to control Indian lands. A series of bloody wars that historian Bernard Bailyn (Reference Bailyn2012) has termed the “barbarous years” followed, and the Christian/savage distinction became central in English thinking about the native peoples. (Goetz Reference Goetz2012)

When Africans were imported to the colony, the most salient boundary between the English and what were then called “20 and odd Negars” brought to Jamestown was religion (Reuter Reference Reuter1918; Wilkerson Reference Wilkerson2020; Wood Reference Wood1997). Obviously, there were differences in skin color and other body features between the English and both the Indians and the Africans and, no doubt, the English perceived such differences. But, because the English did not think of themselves in color terms, the differences in skin color were not as salient as were ethno-religious or cultural differences. It was the centrality of religion in the vocabularies of motive that shaped the English colonial mind and established lines of demarcation between different groups (Goetz Reference Goetz2012; Wood Reference Wood1997).

When colonization was proceeding in the Atlantic world, religious wars in Europe had been frequent, with England throughout the sixteenth century preoccupied with religiously-based conflicts. Internally, the struggle was between Protestants and Catholics, who took turns at beheading or burning the “other” on a stake in alternating periods. More locally, struggles over whether the newly created Church of England could be also established in both Ireland and Scotland extended into the seventeenth century. Also, shaping the English attitude towards other groups was the fact that England suffered a long history of past invasions by heathens and infidels; the Vikings from the north and east, and the Moors from the Barbary coast to the south, who plundered English estates and enslaved English men and women (Davis Reference Davis2003).

Back in the Virginia colony, the lines of demarcation organized around a religious divide were established, and also changed during the first 100 years of colonization as a largely English planter class, dealing with their local issues and problems, abandoned central principles of English common law and enacted colonial laws generating new legal definitions that addressed the planter class’s economic interests. The new legal definitions were couched in the concepts of free and bonded labor because those were the legal categories that were at stake and subject to negotiation. Others might desire to use the terms White and Black, but words connecting race to the institution of slavery were not part of colonial discourse in the seventeenth century (Higginbotham and Kopytoff, Reference Higginbotham and Kopytoff1989) .

DATES AND LAWS

We now turn to an examination of possible dates that have been proposed as marking the color line that eventually emerged in Virginia law.

1619: The Arrival of “20 and odd Negars” in Jamestown

Some historians have argued that the color line was immediately drawn based on “race prejudice,” a longstanding attitude the Colonists brought with them from England (Degler Reference Degler1959; Jordan Reference Jordan1968). This view has been largely abandoned by later scholarship presenting a growing consensus that the initial differentiation between Europeans and the other groups was cultural, largely shaped by ethnic and/or religious differences. Indeed, many have pointed to the Christian/heathen distinction as the most important boundary that separated the English from the other descent groups (Berlin Reference Berlin1998; Reuter Reference Reuter1918). There is no doubt that the English were ethnocentric, perhaps even xenophobic, and had definite prejudices against “others” but they were not necessarily intensely “racial.”

1630: The Punishment of Hugh Davis

There is one fact in the historical record that is uncontested; in 1630 a resident of the Colony of Virginia was punished for a sexual offense. The widely quoted sentence of punishment was as follows:

“Hugh Davis to be soundly whipped, before an assembly of Negroes and others for abusing himself to the dishonor of God and shame of Christians, by defiling his body in lying with a Negro; which fault he is to acknowledge next Sabbath day” (Hening Reference Hening1809–1823, vol. 1, p. 146).

This case is commonly cited by historians of North American slavery as the first punishment for “interracial sex” and the initial sign of the virulent racism that characterized subsequent American attitudes towards people of African descent. But was this case about race? Recalling Fields’ admonition to not assume the presence of “race relations” whenever European and African descent people encounter each other, other possibilities are opened.

Alan Scott Willis (Reference Willis2019) has suggested there is only the presumption that Hugh Davis was an Englishman, although that is likely because of the naming practices of the time; the English were commonly identified with a first and a surname, while Africans were often only identified by one name at the most. Additionally, the fact that part of his punishment was to do penance in the local church, a common practice both in England and its colonies, lends credence to the odds that Davis was an Englishman. But who was the African?

The fact that the word Negro was used, rather than Negress or Negro wench, both commonly used terms, has been interpreted to indicate that Davis’s transgression was not fornication (a heterosexual relationship) but sodomy (a homosexual relationship) (Godbeer Reference Godbeer2002; Jordan Reference Jordan1968). Other legal scholars have parsed the words of Davis’s sentence and concluded that because Negroes had no legal standing as human beings, the offense was one of bestiality (Higginbotham and Kopytoff, Reference Higginbotham and Kopytoff1989) hence the “severe displeasure of God.” Even more confusion about this case can be found in the writing of one legal scholar—viewing the past through the “lens of presentism”—who was so convinced that the case was obviously about an interracial heterosexual relationship that he misrepresented the text of the above sentence by inserting the word Negress in place of the word Negro (Mumford Reference Mumford1999).

Further, the religious rhetoric of dishonoring God and shaming fellow Christians opens the possibility that the moral boundary that was violated was not a norm of “race relations” but a defiling of a Christian-heathen boundary, an important possibility raised by Edmund S. Morgan (Reference Morgan1975). The only reasonable conclusion about the Hugh Davis case is that it cannot be used to establish any element of a color line.

1662: Negro Womens [sic] Children to Serve According to the Condition of the Mother.Footnote 1

This law has been interpreted as evidence of a “color line” for specifying an increased penalty for fornication between people of European and African descent groups, doubling the fine that would be applied to two English or Christian fornicators. But, because the law reads “if any Christian lies with a Negro man or woman” (not “if any White”) it leaves open, as in the 1630 case of Hugh Davis, that the stronger penalty was possibly for Christian-heathen fornication. Of course, a reader might object that “everybody knows” that the legislation was about “race relations” but that stance ignores Fields’ (Reference Fields1990) cautionary note and may be an example of “presentism.” By assuming that “everybody knows” a color line was present any time Europeans and Africans interacted, one obscures alternative historical explanations that are not pursued.

The second part of this 1662 law reverses the English common law practice of a child’s status being determined by the father’s status and specifies that free or slave status is determined by the status of the mother. This shift was of profound importance to the way inter-generational status was defined but did nothing to clearly address the issue of a color line. The boundary specified was one of status and, as observed earlier, Virginia colonial law does not at this time invoke any reference to color or race as singular legal terms.

1667: An Act Declaring That the Baptism of Slaves Does Not Alter Their Status

This act established that conversion to Christianity (moving from being a heathen to becoming a Christian), did not alter a person’s status; converted slaves retained their status as slaves. Because the common law of England precluded any Christian from holding another Christian as a slave, the planter class removed that issue from Virginia colonial law. Helen Tunnicliff Catterall (Reference Catterall1926) interpreted this act to mean that by 1667 in Virginia, “baptism ceased to be the test of freedom and color became the ‘sign’ of slavery: black or graduated shades thereof. A negro was presumed to be a slave” (p. 57).

This interpretation is important because it reinforces the likelihood that the Christian/heathen boundary was operative in the early life of the colony, but any precise dating suggesting a firm “color line” in 1667 is premature. A law passed two years later in 1669 prohibited any free Negro or Indian, even if baptized, from purchasing a Christian servant. As stated, that law provides that “no Negroes or Indians though baptized and enjoined in their own freedom shall be capable of any such purchase of Christians but yet are not disbarred from buying any of their own nation.”

In retrospect, we can infer that the planter class was attempting to draw a color line without knowing how to do it; the identity of the European descent group remains that of Christian. Of course, one could argue that the English back then thought that the term “Christian” meant “White,” but that also then means that at that time any “color term” was in the background of the English mind and the term Christian was much more salient. Certainly, this law evidences the legislators’ concern with drawing a color line boundary, but it remains incomplete.

1691: An Act for Suppressing Outlying Slaves

This is an important law that has been referred to as the starting point of “race relations” for those who think the prior dates are not appropriate. This law contains the following language:

“whatsoever English or other white man or woman being free shall intermarry with a negroe, mulatto, or Indian man or woman bond or free shall within three months after such marriage be banished and removed from this dominion forever.” (Hening Reference Hening1809–1823, vol. 3, p. 86).

For the first time in my scrutiny of the words in Virginia colonial law, the term White is used as part of a legal identity, but it is not a singular legal identity. In the lawmaker’s phrasing “English or other white” the term “White” was likely used to include Scottish and Irish present in the colony. The Scots and the Irish came to Virginia in the early 1650s by being “transported” as prisoners of war, a punishment for fighting against England. Those “transported” were sold as indentured servants and by 1691 some may have become free and/or had free children that were part of the colony. If so, the retention in this law of the identity term of English and the inclusion of the category White may have had to do with the fact that the Scots and Irish were covered by the law. Given the conflict-laden history of these European groups, the Scots and Irish could not be squeezed into the English category as long as the English were writing the laws.

Although the law’s language clearly indicates that the English see themselves physically resembling other Europeans, their language shows that they continue to apply the ethnic label of English to themselves and it is not clear that the phrase “or other white” had anything to do with further separating the English from the Africans.

This point is reinforced nine lines down in this same law when bastardy is the object of legislation and the lawmakers speak only of “English women” bearing children out of wedlock. They do not say “English or other white women” (perhaps there were too few Scottish or Irish women in the colony at that time to worry about). It is also interesting that the nineteenth century editors of this law changed the reference to English women to White women in their marginal notes, a later step in creating the idea of race.

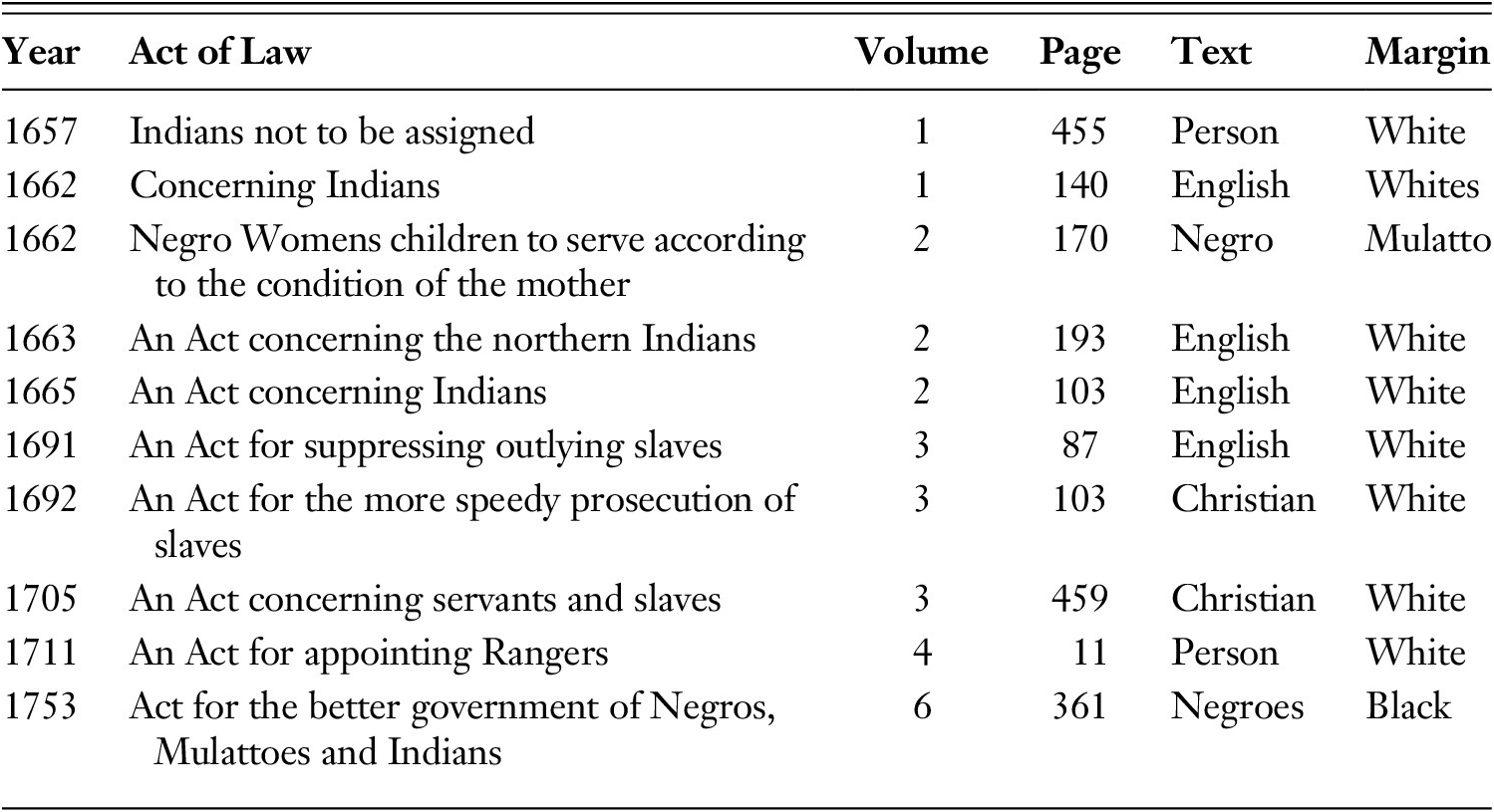

Such observations may seem trivial but see Table 1 for a list of rephrasing of original lawmaker language where the editors of the laws writing over a century or more later, change the meaning of words in the law.Footnote 2 These are good examples of the process of creating the idea of race by the nineteenth century editors suggesting what the writers of laws really meant. Could this be a form of presentism on the part of people in the nineteenth century trying to “clarify” what was meant in the seventeenth? And, is such “clarifying” any different from the present day thinking that projects thinking in “Black and White” on the experience of seventeenth century Virginians?

Table 1. Presentism Examples of “Creating Race.”

Further, a broader point is that this law does not begin to cover the sizable population of indentured servants in the colony who could presumably, under this law, marry whomever they wanted, contingent on what the owner of their indenture would permit. Only free English or other free persons were addressed by the law and subject to the penalty of banishment for a violation. Servants were bonded and were not free to leave the colony.

1705: An Act Concerning Servants and Slaves

This lengthy piece of legislation is a prime candidate for the marking point of establishing a color line. The act was an attempt to systematically bring together important seventeenth century laws into a single document that spoke to various forms of bondage or unfree labor. This law is too long to reproduce here as it consumes twenty-six pages of the Statutes (the reader is referred to volume 3, page 447 of Hening’s Statutes) but a careful reading of the law, and the marginal comments by the editors of the laws, makes it clear that a color line has yet to be neatly drawn.

The most important parts of the Act of 1705 repeat much the same ideas as the earlier 1670 law but one part adds more “religious others” to the list of those who are prohibited from purchasing a Christian servant. It reads, “no Negro, mulatto, or Indian, although a Christian, or any Jew, Moor, Mahometan, or other infidel, shall at any time purchase any Christian servant, nor any other except of their own complexion” (italics added).

The addition of more non-Christian categories to the list of prohibited purchasers is important in showing that religious boundaries remained relevant, but the most significant shift is the change of the 1670 Act allowing non-English persons to have “servants of their own nation” to allowing purchase of servants “of their own complexion.” This reference to complexion suggests an increased sensitivity on the part of the law makers to the factor of skin color and is a step closer to the firm establishment of a boundary of race.

Overall, these changes made in 1705 indicate that the thinking of the planter class remained rooted within a religious universe of discourse: they added an additional set of non-Christian others to the “cannot purchase” list and, they retained the language of Christian for the person who cannot be purchased. Yet, in one clause of this first major law of the eighteenth century, there are two mentions of White as a singular legal category, where the law prohibits ministers from marrying a White man or a White woman to a Negro. Does this mean that a color line has been drawn as many scholars, including Higginbotham (Reference Higginbotham1978) and Morgan (Reference Morgan1975), suggest?

That conclusion is possible only if one ignores the distinction between singular and more complex legal identities. Examining all twenty-six pages of this law that contains forty-one clauses yields only confusion. In all other forty clauses, the legal term to identify a person of European descent has the following distribution: twelve references to Christian and four references to Christian White. If a clear color line were being drawn, the term White could be the operative term in all of those places. Additionally, this law includes a very cumbersome phrase the that prohibits any Negro, Mulatto, or Indian, bond or free, from “raising his or her hand, in opposition to any christian, not being negro, mulatto, or Indian” (italics added). Although that complex phrasing suggests that the lawmakers clearly mean “not being negro, or mulatto or Indian” means Christian equals White, they somehow cannot bring themselves to use White as the central legal identity, which apparently still resides in the background of the English mind. Additionally, note the phrasing of Christian White as opposed to how it would likely be phrased today as a White Christian, indicating the differing salience of identity terms in different historical eras. On balance, one can only conclude that a color line was in the in process of being created yet not finalized in the major race code of 1705.

1723: An Act for the Settling and Better Regulation of the Militia

In the language of this Act a color line was sharply drawn. This law did two things to make the color line more visible. The legal term White is used as a singular identity, one that stands alone as a definition of a type of person. This law speaks of an “able-bodied white man” as a possible replacement for members of the political elite who did not want to serve in the militia and preferred to hire a “white man” to serve in his place.

Another important thing this law did was to dramatically degrade the status of free Negroes in multiple ways. Because of the increasing fear of invasion or slave insurrection, the freedom of all persons of African descent to assemble was restricted. Slaves were prohibited from assembling in groups larger than five and if any free Negro were found in such a grouping they, as well as the slaves, could be punished by death or dismemberment. Another way the rights of free Negroes as citizens of the colony were attacked was to deny them their previously held right to vote, an important limitation of freedom. The act also undermined the status of free Negro married women by making them tithable, that is taxable persons—an exception to the way married women of European descent were shielded from taxation. And one final way the meaning of free was altered for free Negroes was that their role in the militia was reduced from being armed for combat to being “drummers or trumpeters” and/or performing any “servile duty” assigned to them. While free Negros retained that label and could not be enslaved, they were effectively moved across a firmer “color line” that assigned unfettered freedom only to people of European descent.

While this act is clear that White had become a singular legal term and the color line was hardening, did this 1723 law set the precedent for White as a legal identity? We need to examine one last piece of legislation to see what happened.

1753: An Act for the Better Government of Servants and Slaves

This act is a refinement of the 1705 act that attempted to codify seventeenth century legislation on servants and slaves. It, perhaps predictably, repeats the language of major elements of that legislation continuing to use English and Christian as legal identities. But, does that mean no shift was started in the 1723 legislation?

Recall that the 1723 legislation was carving out new ground, the creation of a militia, and there was no earlier law to reiterate. The 1753 Act on servants and slaves covered old legal turf and, perhaps, used older language without much reflection. If so, it demonstrates once again how the planter class, assuming its goal was to create a clear color line, was so accustomed to thinking in ethno-religious terms they did not sharpen their language to make the color line clear.

Because of the continuing repetition of legal language, I decided to simply search for the last time English and Christian appeared as a legal identity in the Colonial era and when White and White only appeared as the legal descriptor. English disappeared from Virginia colonial law after 1753 and Christian no longer appeared after 1765 where the term was used to differentiate free Christian White women from White women, a distinction having nothing to do with a color line.

By 1765, after African slavery was firmly institutionalized in Virginia (de la Fuente and Gross, Reference de la Fuente and Gross2020), White as a singular legal identity began appearing consistently. Laws clearly identify White men and White women as legal actors and by an Act in 1769 the attempt of any slave to ravish any “White woman” was met with the strong punishment of castration. In subsequent years White and White only became the term of law identifying people of European descent and Black entered as a legal identity in 1782 when each new state was given the task by the federal government to conduct a census of its population. In Virginia, in each county, the master of a family was charged with reporting the number of persons in the household, listed separately as White and Black.

The fact that it took well over 100 years for the English colonists to think of themselves as “legally White” speaks to the early power of ethno-religious vocabularies as the customary language the English used to name and classify themselves. Sometime around the middle third of the eighteenth century the words English or Christian were no longer needed as legal identity terms in colonial Virginia; being White became enough.

IMPORT OF THE FINDINGS

This research has documented a long and convoluted process wherein a planter class created enacted law that culminated in the creation of a color line. No precise date can be designated as the moment a color line was drawn, but this research suggests that it was not in the seventeenth century but only well into the eighteenth century in colonial Virginia. Interestingly, that is the general time-frame when Virginia moved from being a society with slaves to a slave society (Berlin Reference Berlin1998; de la Fuente and Gross, Reference de la Fuente and Gross2020; Parent Reference Parent2005) Recalling Table 1 that documents the way the nineteenth-century editors of Virginia’s legal codes changed seventeenth-century words like Christian or English to White, it becomes clear that there was no use of White as a legal identity in the text of colonial law throughout the seventeenth century. The editors’ marginal notes that injected the category of White during the nineteenth century are best seen as a part of a long process of the continuing construction of the White component of the color line that we take for granted today. To rephrase and extend the ideas of Theodore W. Allen (Reference Allen1994) cited earlier in this paper, there were no Whites at the initial meeting of Europeans and Africans at Jamestown in 1619 nor throughout the whole of the seventeenth century.

We turn now to addressing some of the implications of these findings for future research. The conclusion of a mid-eighteenth century time period for the social, historical construction of race departs from much prior thinking and rests upon the presumed importance of (1) legal acts as defining the steps towards a color line; (2) a process in which multiple identities devolve into a singular legal identity; and (3) a general transition from ethno-religious demarcations to the invention of a racialized boundary.

Colonial law was a major force in attempting to keep descent groups separate, especially by the severe sanctions placed on sexual contacts between members of different groups. As noted above, laws aimed at the prevention of mixed descent-group children whose status as free persons was ambiguous, were critical. The offspring of European males and enslaved African women did not pose boundary issues for the colony but simply meant another slave was added to an owner’s property. But, while the free Mulatto population was small and produced by an African male and European female—the combination, some historians claim, that produced more Mulattoes than the European slave owner’s sexual exploitation of African slave women (Berlin Reference Berlin1998; Reuter Reference Reuter1918; Williamson Reference Williamson1980)—their growing presence and likely darker skin color was possibly part of the general shift of the boundary from a belief system rooted in less visible traits (religion) to one based on a more visible difference (skin color as a marker of race). One empirical issue that might be addressed is whether representatives to the General Assembly from counties where free Mulattoes were disproportionately present were more active in creating a color boundary in law.

Another area needing more research is how the arrival of other Europeans to the Virginia colony affected the English colonial identity. Past work on “race codes” focuses on the status of the enslaved and the creation of a binary boundary. The legal color line defining freedom and enslavement became based on the presence of, indeed the proportion of, African descent of a person (leading eventually to a “one drop” rule). This suggests that the “slave laws” were implemented to create an unfree labor force based on a singular color identity. What most past research does not emphasize is how the English could accomplish that goal only by first creating Whiteness as a feature of themselves and others of European descent.

The English had at their disposal relatively stable terms of identity for the two other descent groups. Indians were Indians without any color term attached and Africans were labeled Negroes, a term that signified both the color black and the status of slavery, the exception being that special category of “free Negro.” But, after the reduction of the rights and privileges of free Negroes in the eighteenth century, a color line emerged that based African enslavement on an imputed essence rooted in their darker skin color.

For the English, there was a complex process of shifting from being free, English, and Christian to White as the definer of freedom. Most past research has assumed that the English came to see themselves as White because of their contact with darker Africans. But, to pose a hypothetical, had the English been able to create an all-English colony in which other European groups were not members of the polity, would they have automatically, over time, shifted from being English to being White before the Revolutionary War when the identity of American was created? Phrased differently, which set of comparisons was more critical in the process of the English becoming White; the color contrast between Europeans and Africans, or the perceived commonality the English saw between themselves and other Europeans vis-á-vis those of African descent who constituted the unfree labor force? How which or both became part of the color line is an open question.

The hypothesis that the English grew aware of an interest-group commonality between themselves and other formerly antagonistic European groups like the Scots and the Irish, might be explored by looking at protests among Europeans against the established, planter class. Although occurring before the eighteenth century transition from religion to race, Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676 was a largely English movement that included an ethnically diverse number of Scottish, Irish, French, and Dutch indentured servants and African slaves—the social alignment the planter class most feared. Indeed, Morgan (Reference Morgan1975) saw a rising class protest in Bacon’s Rebellion and then later servant and slave unrest as a key reason the planter class attempted to separate European servants and African slaves in the race code of 1705. These ideas suggest the need for additional research on the possible role of European ethnic complexity in the formation of a color line. Such a line of research would not assume sheer contact is “race relations,” which leaves open the exploration of other factors (Fields Reference Fields1990).

One other important neglected factor is religion. The present interpretation of Virginia’s colonial era enacted law shows how, over time, religion was replaced by a socially constructed concept of race, shifting the bases upon which Africans were excluded from the world of free persons. The law draws a line between those who are free and those carrying the weight of bondage, a line crossed by some Africans in the first several decades of the seventeenth century that was gradually closed by virtue of a series of legislative acts defining who was free largely on skin color as a marker of race.

The importance of the connection between religion and race can be illustrated by research from the last decade. Rebecca Goetz’s The Baptism of Early Virginia: How Christianity Created Race (Reference Goetz2012), and Katherine Gerbner’s Christian Slavery (Reference Gerbner2018), attempt to document the importance of Protestantism in shaping slavery in the wider British Atlantic world. These works seek to show that the concept of race is not reducible to psychological attitudes nor material, economic interests, but is a factor in which religious practices and beliefs played an important role in shaping the contours of what becomes slavery as a form of “race relations.” Goetz sees the debate around baptism not leading to a slave’s freedom as a critical step in a process by which religion creates race. And, both Goetz and Gerbner examine how the planter class worked against the idea that Africans could become true Christians, providing a religious boundary that provided the moral and intellectual foundations for the creation of the concept of race; in short, over time they see race coming to replace religion as the factor that determined the boundary between Europeans and Africans.

This case study makes no claims to having identified all the steps involved in the creation of a color line. In fact, different color lines were likely drawn at other times in different places around the globe. While Du Bois spoke of the color line as an emerging global pattern of European expansion of power, it is likely that he would agree with the view of the color line as an aggregation of a large number of lines drawn at particular, different times and places. The study has addressed how and where a particular line in Colonial Virginia was drawn and supports Berlin’s (Reference Berlin1998) view that the concept of race is “a historical construction, it cannot exist outside of time and place” (p. 4).

The most general import of the present research is that when the concept of race is seen as something automatically triggered by sheer contact or reflects current forms of race-thinking projected on the past, research becomes constrained and fails to see the complexities of the social concept of race as a historical, contingent outcome. Further, any role of factors other than psychological reactions or economic interest, the usual suspects as causes of enslavement, such as legal codes, ethnic complexity, mixed-descent persons, and religious factors, are relatively unexplored. When social structures are seen as historical processes, changing with the way the interactions of people within them are shaped by the identities assumed and attributed to others, research imaginations are opened to the multiplicity of factors that help us better understand what unites and divides people.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank Matthew Hunt, John Pease, and Nancy Sullivan for their comments on earlier editions of this manuscript. Appreciation is also due the referees of this journal for their helpful critiques.