Of all forms of inequity, injustice in healthcare is the most shocking and inhumane.

—Martin Luther King, Jr., National Convention of the Medical Committee for Human Rights, Chicago (Reference King1966)INTRODUCTION

Over the past two decades, thousands of studies have demonstrated that BlackFootnote 2 adults and children are less likely to receive appropriate, guideline-concordant, and cutting-edge medical care than their White counterparts, independent of disease status and other clinically relevant factors. These inequities are mediated through and persist independently of Blacks' lower access to health insurance, lower average socioeconomic status (SES), and lower access to care at high-performing medical-care facilities (Moy et al., Reference Moy, Dayton and Clancy2005; Smedley et al., Reference Smedley, Stith and Nelson2003). Furthermore, high SES, private health insurance, high-performing health plans, and receipt of care at high-performing hospitals and clinics, while beneficial, do not consistently afford the same quality of medical care to Black patients as they do White patients (Eberly et al., Reference Eberly, Davidoff and Miller2010; Epstein et al., Reference Epstein, Gray and Schlesinger2010). The massive evidence of racial inequities in care and outcomes reveals deeply entrenched institutional racism in the U.S. health-care system. Institutional racism refers to a set of organizational practices that create unequal outcomes between groups on the basis of their race or ethnicity. It does not necessarily imply conscious intent and can occur outside the awareness of organizational members. Institutional racism is shaped by, and reinforces, societal racism, defined here as a pattern of deeply entrenched and culturally sanctioned beliefs, practices, and policies which, regardless of intent, serve to provide or defend the advantages of Whites and disadvantages to groups assigned to other racial or ethnic categories.

The medical professions have a historical commitment to principles of fairness, equity, and distributive justice. Over the past decade every influential organization with a stake in medical-care delivery has responded to evidence about racial inequity in medical care by acknowledging and condemning it. There has been an avalanche of policy statements, reports, and publications, and a great deal of private foundation and public funding targeted towards addressing institutional racism in medical care. While this response represents significant improvement over the doubt, denial, and silence that characterized the policy and medical leadership fifteen years ago, there has been very little actual progress towards eliminating racial inequities in medical care (Kelley et al., Reference Kelley, Moy, Stryer, Burstin and Clancy2005; Le Cook et al., Reference Le Cook, Mcguire and Zuvekas2009).

Clinician bias is one of several contributors to racial inequalities in care and outcomes (Fincher et al., Reference Fincher, Williams, Maclean, Allison, Kiefe and Canto2004). Bias includes generally negative feelings and evaluations of individuals because of their group membership (prejudice), overgeneralized beliefs about the characteristics of group members (stereotypes), and inequitable treatment (discrimination). These biases may be conscious and intentional (explicit) or unconscious and automatically activated (implicit). Explicit biases have traditionally been assessed with self-report measures whereas implicit biases are usually assessed with validated tests of unconscious associations (e.g., the Implicit Association Test (Greenwald et al., Reference Greenwald, Poehlman, Uhlmann and Banaji2009)).

Almost a decade ago we proposed a conceptual model, shown in the center of Figure 1,that suggested a set of hypothesized mechanisms through which clinicians' behavior, cognition, and decision making might be influenced by patient race to contribute to racial inequities in care (van Ryn and Fu, Reference van Ryn and Fu2003). While still under-studied, empirical evidence has supported the hypothesized mechanisms, demonstrating that White clinicians: (1) hold negative implicit racial biases and explicit racial stereotypes, (2) have implicit racial biases that persist independently of and in contrast to their explicit (conscious) racial attitudes, and (3) can be influenced by racial bias in their clinical decision making and behavior during encounters with Black patients (Cooper Reference Cooper2008; Green et al., Reference Green, Carney, Pallin, Ngo, Raymond, Iezzoni and Banaji2007a; Hirsh et al., Reference Hirsh, Jensen and Robinson2010; Penner et al., Reference Penner, Dovidio, West, Gaertner, Albrecht, Dailey and Markova2010; Sabin et al., Reference Sabin, Rivara and Greenwald2008; van Ryn and Burke, Reference van Ryn and Burke2000; van Ryn et al., Reference van Ryn, Burgess, Malat and Griffin2006; White-Means et al., Reference White-Means, Zhiyong, Hufstader and Brown2009). Despite the evidence that health professionals are (however unintentionally) perpetuating discriminatory practices, there has been little action and minimal progress toward eliminating the clinician contribution to racial inequities in care. Why has there been so little progress in response to evidence of pervasive and grave injustice?

Fig. 1.

Writing this paper led us to examine our own contribution to the lack of progress in rectifying this situation. While there are a variety of factors that impede action, our own framing and discourse on this topic may have impeded public support for policy solutions to eradicate racial inequities in care. In examining the impact of “patient race” on clinicians' implicit cognitive processes, we may have inadvertently reinforced a sense of the problem as a property of the patients (“their” race) and the solution outside health professionals' control (uncontrolled cognitive processes). The emphasis on unconscious processes may have lowered feelings of moral responsibility and accountability for rectifying unjust practices.

To a large extent, our prior emphasis on the role of implicit bias, an unconscious and automatic process, was, while grounded in theory and existing research, intentional and strategic. We wished to work effectively within the existing sociopolitical structure of medical care. When we first started presenting the concept that clinicians' actions were perpetuating institutionalized racism to physician audiences in the 1990s, many in the audience reacted negatively, expressing hostility, mistrust, and dismissal of the topic. While intellectual doubt and criticism is productive when it creates interest in and advances discourse on a problem, strong negative arousal and aversion is rarely productive. Thus, we chose to use terms like “the impact of race” (van Ryn and Fu, Reference van Ryn and Fu2003; van Ryn et al., Reference van Ryn, Burgess, Malat and Griffin2006) rather than emphasizing the role of racism, in the hopes of reaching our target audience and creating openness to the need for change.

We have, however, continued to struggle with the possibility that our efforts to work within the power structure of the medical professions may have helped perpetuate the very problem we have been addressing. Using language such as “the impact of patient race” rather than “the impact of societal racism” on clinician cognition, behavior, and clinical decision making may have deflected discourse from the ways in which group stereotypes and institutional arrangements are products of racism and serve to reinforce racial inequality (Jost and Banaji, Reference Jost and Banaji1994; Sidanius et al., Reference Sidanius, Levin, Federico, Pratto, Jost and Major2001). This strategy ignored the sociopolitical function of racism and may have failed to fully and unquestionably communicate the clinical professions' moral responsibility for eliminating injustices embedded within their own institutions and clinical practice patterns. Hence here we have shifted our framing of the problem, from “the impact of patient race …” to the more accurate “impact of racism … on clinician cognitions, behavior, and clinical decision making.” The fact that automatic and frequently unconscious processes are in play reduces blame but not responsibility. Bioethical principles of justice and benevolence require medical-care systems and clinicians to do everything in their power to prevent these processes from causing unjust and harmful inequities in care.

This paper applies evidence from several disciplines to further specify our original model of the way racism interacts with common human social cognitive processes to affect clinicians' behavior and decisions and, in turn, patient behavior and decisions, with special attention to modifiable factors, leverage points, and avenues for intervention. We apply the existing evidence to concrete action steps in a set of recommendations for medical care organizations and leaders.

REVISED MODEL OF THE HYPOTHESIZED MECHANISMS THROUGH WHICH RACISM INFLUENCES CLINICIANS TO CREATE INEQUITIES IN CARE

The model we explicated in earlier work can be found in the center of Figure 1 and in the corresponding hypotheses in Table 1. Because this portion of the model has been discussed thoroughly elsewhere, we refer the reader to an earlier article (van Ryn and Fu, Reference van Ryn and Fu2003) and focus here on new material. In this model, the impact of societal racism is seen to be pervasive and its influence on the health-care encounter and outcomes is seen to be moderated by the setting of the encounter (health-care organization and clinic environment) as well as interpersonal and individual (clinician and patient) factors.

Table 1. Summary of Core Hypotheses in the Previously Published Model, Presented in the Center of Figure 1 (adapted from van Ryn and Fu, Reference van Ryn and Fu2003)

We added two constellations of hypothesized mediators and moderators of the effect of societal racism on clinician behavior and decision making. Addition A, in the bottom part of the model, focuses on patient factors. Addition B focuses on clinician characteristics. Both influence each other and are affected by setting characteristics (medical-care organization and policies, and clinical environment) and we apply this evidence to specific recommendations for action in medical care organizations.

Addition A, shown in the lower third of Figure 1, adds the concept of stereotype threat to our previous model. Stereotype threat occurs as a result of environmental or interpersonal cues that signal that an individual may be at risk of a situational threat of judgment or mistreated based on personal characteristics. It may be experienced explicitly or implicitly (triggered outside of awareness). In a conversation with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Claude Steele explains:

Stereotype threat … refers to being in a situation or doing something for which a negative stereotype about one of your identities—your age, your race, your gender—is relevant to you. You know then that you could be seen and treated in terms of that stereotype…. as a member of this society, I know that your mind knows a number of negative stereotypes … and that if you wanted to—or even without thinking about it very much—you could judge me in terms of those bad stereotypes

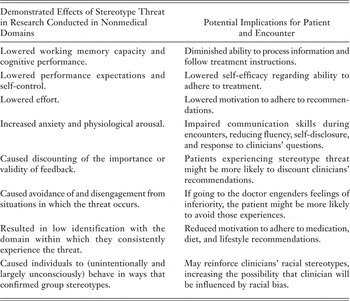

(Gates and Steele, Reference Gates and Steele2009, pp. 251–252).Over 300 experiments have been published in peer-reviewed journals demonstrating that experiencing stereotype threat can significantly reduce performance on cognitive and social tasks; increase anxiety, frustration, disappointment, and sadness; and generate coping strategies that may have undesirable effects (Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Warren, Phelan, Dovidio and van Ryn2010; Schmader et al., Reference Schmader, Johns and Forbes2008; Steele and Aronson, Reference Steele and Aronson1995). Although there have been no published studies of stereotype threat in clinical settings, the robust findings in other arenas may have powerful implications for medical care.Footnote 3Table 2 provides the most important and well-replicated findings regarding the impact of stereotype threat, as well as their implication for minority patients in clinical settings.

Table 2. Potential Consequences of Stereotype Threat for Patients (adapted from Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Warren, Phelan, Dovidio and van Ryn2010)

Addition A also describes how clinicians' interpersonal behavior and clinical setting characteristics may potentiate stereotype threat, impair patients' cognitive resources, cognition, and behavior, and in turn reinforce negative clinician attitudes, potentially creating a negative spiral (Street et al., Reference Street, Gordon and Haidet2007). Many studies have shown that clinicians' interpersonal behavior influences patient behaviors, including communication, adherence, and health care utilization (Roter, Reference Roter2000; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Brown, Donner, Mcwhinney, Oates, Weston and Jordan2000; Street et al., Reference Street, Gordon and Haidet2007). When clinician behavior is influenced by racial bias, it may induce stereotype threat among patients. This may in turn negatively impact patient communication, adherence, and utilization, such that the original racial bias becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Patients' prior experiences of disrespect and discrimination, which are associated with higher treatment dropout, lower participation in screening, avoidance of health care, delays in seeking help and filling prescriptions, and lower ratings of health-care quality, may amplify this negative cycle (Blanchard and Lurie, Reference Blanchard and Lurie2004; Hausmann et al., Reference Hausmann, Jeong, Bost and Ibrahim2008; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ayers and Kronenfeld2009; Sorkin et al., Reference Sorkin, Ngo-Metzger and De Alba2010). Clinical settings, and the structures and cultures embodied within them, have the potential to exacerbate or mitigate stereotype threat and its negative consequences.

It is important to note that disparities in performance between stigmatized and nonstigmatized groups have been reduced or eliminated when stereotype threat is alleviated (Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Steele and Quinn1999). It is possible to create environments in which people feel safe from negative stereotypes (Steele Reference Steele1992). Table 3 provides a set of recommendations for heath-care environments that were adapted and slightly expanded on from those made by Burgess et al. (Reference Burgess, Warren, Phelan, Dovidio and van Ryn2010).

Table 3. Strategies for Creating “Identity-Safe” Clinical Environments and Reducing Stereotype Threat,Translated from Findings in Nonmedical Domains (adapted from Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Warren, Phelan, Dovidio and van Ryn2010)

Addition B highlights the role of individual clinician factors in mediating and moderating the impact of societal racism on clinicians' beliefs, attitudes, and expectations of patients, and points to setting factors that can be targeted to reduce inequities in care. It reflects a large body of evidence regarding situational and contextual factors as well as stable characteristics of individuals that influence the likelihood that racial (and other) biases will be activated and adversely affect judgment and behavior. We first review relevant clinician factors and then apply the evidence on contextual factors to recommendations to medical organizations regarding strategies that can create identify-safe environments and assist clinicians in their goal of providing high-quality and equitable care.

Clinician Characteristics

Racial Bias

Like the general population, clinicians vary widely in their levels of both implicit and explicit racial biases. Moreover, implicit and explicit biases are only weakly correlated (Dovidio et al., Reference Dovidio, Kawakami, Beach, Brown and Gaertner2001). Most Whites are low in explicit and high in implicit prejudice, although there are Whites who are consistently low in both forms of bias (i.e., both explicit and implicit) and those who are high in both. The combination of high explicit with low implicit bias is rare.

High Explicit And Implicit Racial Bias

To our knowledge there have been no representative studies of clinicians to ascertain the proportion who are high on contemporary measures of explicit racial bias. Little is known about the impact of explicit racism on provision of care. Two sociopolitical orientations have been shown to predict explicit biases in numerous studies: Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) and Medical Authoritarianism (MA), an offshoot of Right Wing Authoritarianism (RWA). SDO represents the degree to which people value hierarchically structured relationships among social groups, such as the dominance of Whites over Blacks (Pratto et al., Reference Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth and Malle1994). RWA reflects the level of belief in traditional authority structures. MA is specific to the health-care context; it has been found to predict medical students' tendencies to stereotype and make negative attributions about patients from stigmatized groups and, unfortunately, appears to increase over the course of medical education (Merrill et al., Reference Merrill, Laux, Lorimor, Thornby and Vallbona1995).

High levels of explicit bias (as predicted by SDO, RWA, and MA) among clinicians may be difficult to change, so interventions that effectively limit how these personal orientations translate into bias in clinical decision making and behavior are needed. In our prior work we advocated interventions that appealed to clinicians' prosocial motivations to provide the highest quality of care for all patients. However, appeals to such prosocial motivations may be less effective for clinicians who do not have egalitarian standards (Monteith et al., Reference Monteith, Mark and Ashburn-Nardo2010). Even for those who do, efforts to address explicit bias should be approached cautiously. Concerns about appearing biased can actually accentuate stereotypic thinking (stereotype rebound (Monteith et al., Reference Monteith, Sherman and Devine1998)) and interfere with communication and rapport (Goff et al., Reference Goff, Steele and Davies2008). Instead, bias might be more effectively reduced among clinicians high in SDO or RWA by emphasizing universal application of norms, rules, and guidelines. In fact, clinicians high on RWA and MA may be particularly likely to be compliant with guidelines (Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Phelan, Dovidio and van RynForthcoming; Phelan et al., Reference Phelan, van Ryn, Wall and Burgess2009). For this group, then, guideline-driven quality improvement efforts may be the most effective pathway to more equitable care.

Low Implicit and Explicit Racial Bias

There is a subset of White clinicians who are low on both implicit and explicit racial bias measures. Sabin et al. (Reference Sabin, Rivara and Greenwald2008; Reference Sabin, Nosek, Greenwald and Rivara2009) examined a large sample of physicians and found that a small minority of White physicians did not have an implicit pro-White bias, that women physicians had lower levels of pro-White implicit bias than male physicians, and Hispanic and Asian physicians had levels of pro-White implicit bias that were similar to White physicians. Black physicians, on average, did not show a systematic implicit preference for either White Americans or Blacks. Furthermore, implicit bias may differ by specialty and or site; Penner et al. (Reference Penner, Dovidio, West, Gaertner, Albrecht, Dailey and Markova2010) found that their sample of fifteen family medicine clinicians working in an inner city had less implicit pro-White bias than other clinician samples.

Low Explicit and High Implicit Racial Bias

Dovidio and Gaertner (Reference Dovidio, Gaertner and Zanna2004) use the term aversive racism to describe people who have low levels of explicit bias and high levels of implicit bias—because consciously egalitarian people experience the idea that they are racially biased as aversive. White aversive racists are more likely to experience anxiety and discomfort than hostility when interacting with Blacks. Because explicit bias affects verbal behavior and implicit bias influences nonverbal behavior, the combination of high implicit and low explicit bias has negative implications for clinician-patient encounters. For example, Whites with high implicit racial biases and low explicit bias were found to have less direct eye contact with Blacks than with Whites (Dovidio et al., Reference Dovidio, Kawakami, Johnson, Johnson and Howard1997b). Clinicians may be aware that what they say is consistent with their explicitly egalitarian attitudes but unaware of the way their implicit biases influence their nonverbal behaviors (McConnell and Leibold, Reference McConnell and Leibold2001). The lack of correspondence between nonverbal behavior and verbal friendliness may lead to suspicions of duplicity among Black patients because inconsistency between positive overt expressions and negative subtle displays is generally perceived to reflect deceitfulness (Dovidio et al., Reference Dovidio, Penner, Albrecht, Norton, Gaertner and Shelton2008). Consistent with this finding, Black patients were least satisfied with their medical encounter when physicians were relatively high on implicit but low on explicit bias compared to every other combination, including clinicians who were high on both explicit and implicit bias (Penner et al., Reference Penner, Dovidio, West, Gaertner, Albrecht, Dailey and Markova2010). Reducing this adverse consequence of the combination of high implicit and low explicit bias may be achieved through efforts to increase clinicians' awareness, motivation, and skills, as well as decrease interracial anxiety, as described below.

Awareness of Racial Inequities

In order to create a felt need and motivation for change, clinicians must be aware of both overall racial inequities in care as well as their own potential to be biased in their care of patients (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Betancourt, Wynia, Bussey-Jones, Stone, Phillips, Fernandez, Jacobs and Bowles2007). The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) 2002 National Survey of Physicians found that only 25% of White physicians versus 77% of Black physicians believed that patients are treated unfairly due to their race or ethnicity very or somewhat often (KFF 2002). A few years later, a 2005 survey of approximately 2000 physicians found that 55% of White physicians agreed that minority patients generally receive lower quality care than White patients, 21% were unsure, and 24% disagreed (AMA 2005). Furthermore, a recent qualitative study of twenty-six doctors and nurses found the majority questioned the validity of studies reporting disparities (Clark-Hitt et al., Reference Clark-Hitt, Malat, Burgess and Friedemann-Sanchez2010). Clearly, more effective strategies are needed to ensure the majority of clinicians are aware of this problem.

Personal Bias Awareness

Clinicians who are aware of inconsistencies between their subtly biased behaviors and egalitarian attitudes may be more likely to “correct” for potential bias in the short term and be more motivated to engage in self-regulatory processes that can inhibit even subtle expressions of bias in the longer term (Devine and Monteith, Reference Devine, Monteith, Mackie and Hamilton1993). Consistent with this notion, Perry and Murphy (Reference Perry and Murphy2011) found that, in a stressful interracial context, Whites who felt that they may harbor subtle racial biases toward Blacks (what they have termed “bias awareness”) responded with more guilt and willingness to dedicate time to activities aimed at improving racial diversity than did Whites with low bias awareness. Thus, clinicians' bias awareness may affect their willingness to participate in bias reduction interventions.

Motivation to Control Prejudice

Contrary to early fears about the uncontrollable automaticity of implicit bias, a number of studies have found that people who are high on internal motivation to control prejudice and have sufficient cognitive resources can be very successful at limiting the impact of implicit biases (Monteith et al., Reference Monteith, Mark and Ashburn-Nardo2010; Plant and Devine, Reference Plant and Devine2009). With sufficient cognitive resources and practice, people are able to focus on the unique qualities of individuals, rather than on the groups they belong to, in forming impressions of and behaving toward others.

Skills

Several general interpersonal abilities are associated with lower racial bias. Both the cognitive and affective components of empathy ultimately produce more positive orientations toward another person and a greater interest in the other's welfare (Batson et al., Reference Batson, Polycarpou, Harmon-Jones, Imhoff, Mitchener, Bednar, Klein and Highberger1997); focusing on the other's feelings engenders greater empathy than “being objective” (Batson et al., Reference Batson, Polycarpou, Harmon-Jones, Imhoff, Mitchener, Bednar, Klein and Highberger1997). Perspective-taking (the cognitive component of empathy) has been shown to reduce bias toward a range of stigmatized groups, including Blacks, at least in the short term, and to inhibit the activation of unconscious stereotypes and prejudices (Dovidio et al., Reference Dovidio, Gaertner and Validzic1998, Reference Dovidio, Penner, Albrecht, Norton, Gaertner and Shelton2008; Galinsky and Moskowitz, Reference Galinsky and Moskowitz2000). Many studies have documented the positive effects of clinician empathy on patient satisfaction, self-efficacy, perceptions of control, emotional distress, adherence, and health outcomes (Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Van Ryn, Dovidio and Saha2007).

Recent research outside the medical domain suggests that clinicians who have good emotional regulation skills and experience positive emotion during clinical encounters may be less likely to categorize patients in terms of their racial, ethnic, or cultural group and more likely to view patients in terms of their individual attributes (Johnson and Fredrickson, Reference Johnson and Fredrickson2005). They also use more inclusive social categories, so that people are more likely to view themselves as being part of a larger group (Dovidio et al., Reference Dovidio, Gaertner, Isen and Lowrance1995, Reference Dovidio, Gaertner and Validzic1998). This can facilitate empathy and increase the capacity to see others as members of a common “ingroup” as opposed to “outgroup” (Dovidio et al., Reference Dovidio, Gaertner, Isen and Lowrance1995; Dovidio and Gaertner, Reference Dovidio, Gaertner and Zanna2004; Gaertner and Dovidio, Reference Gaertner and Dovidio2000) Likewise, partnership-building skills can reduce the likelihood that implicit bias will affect clinician behavior and decision making; clinicians who have skills at creating partnership with patients are more likely to develop a sense that their partner is on the same “team,” working together towards a common goal, and developing a common ingroup. This is also likely to reduce patients' experiences of stereotype threat. Perceptions of common ingroup membership, of being on the same team, also facilitate perspective-taking (Dovidio et al., Reference Dovidio, Gaertner, Stewart, Esses, Ten Vergert, Stephan and Vogt2004) and affective empathy (Dovidio et al., Reference Dovidio, Gaertner, Validzic, Matoka, Johnson and Frazier1997a).

Interracial Anxiety

Researchers have found that White people who sincerely want to behave in a nonprejudiced manner often manifest anxiety and heightened levels of arousal when interacting with minority or other stigmatized group members (Dovidio and Gaertner, Reference Dovidio, Gaertner and Zanna2004). Intergroup anxiety leads people to avoid intergroup contact, negatively impacts the nature and experience of intergroup interaction, interferes with effective communication, and may exacerbate negative feelings about members of the other group, which reinforces the desire to avoid such contact in the future (Plant and Butz, Reference Plant and Butz2006). Furthermore, anxiety absorbs cognitive resources, so that interracial anxiety may produce lower-quality judgments and behavior. In addition, many of the nonverbal expressions of anxiety (e.g., averted gaze, closed posture) are similar to those associated with dislike, so anxiety may be interpreted as indicating racial prejudice (Dovidio et al., Reference Dovidio, Penner, Albrecht, Norton, Gaertner and Shelton2008). Nevertheless, intergroup anxiety is very different from racial prejudice or stereotypes and requires a different intervention.

In this section we reviewed characteristics of clinicians that have been shown in social-psychological studies to affect the likelihood of racial biases in behavior and decision making. Clinician characteristics such as awareness of racial bias, empathy, emotional regulation, and partnership-building skills are promising targets for intervention as they are mutable skills and have potential impacts on both bias and interracial anxiety. However, institutional racism is so entrenched that new behaviors are more likely to persist if supported by the social environment; interventions targeting clinician factors may be most successful if aimed at all personnel and embedded in overall organizational change.

Setting Factors and Recommendations to Medical Care Organizations

Evidence from a variety of disciplines points to a number of promising approaches to eradicating inequities in care.

Establish Ongoing Procedures for Monitoring and Assessing Equity in Care

Because many different elements contribute to individual assessments and decisions, bias is much more difficult to recognize in a specific instance than when information is aggregated across cases (Crosby et al., Reference Crosby, Clayton, Alksnis and Hemker1986). Systematically collecting data on race and other indicators of social position is necessary if care systems are to meet their obligation to self-assess, monitor, and evaluate the effectiveness of their strategies for eradicating inequities in care. Frameworks for data collection have been or are being developed that may prove very helpful for monitoring inequities (Newhouse Reference Newhouse2009; Siegel et al., Reference Siegel, Andres and Mead2009). When inequities are found, providing targeted feedback, supporting creative solutions for remediation, and creating accountability for improvement may inspire the development of a number of innovative and effective correction strategies.

Reduce Stressors that Increase Clinicians' Cognitive Load

Racial bias and stereotypes are more likely to influence cognitions and behaviors when individuals' cognitive capacity is low or overtaxed (called “high cognitive load”). Furthermore, when cognitive capacity is taxed, memory is biased toward information that is consistent with stereotypes, and individuals are less able to override automatic processes of racial categorizing and stereotyping (Burgess Reference Burgess2010). Practice setting characteristics that create high cognitive load include productivity pressures, time pressure, high noise levels, inadequate staffing, poor feedback, inadequate supervision, inadequate training, high communication load, and overcrowding (Croskerry and Wears, Reference Croskerry, Wears, Markovchick and Pons2002). Conversely, established routines, adequate time per patient and between patients, and sufficient staffing resources are protective factors (Burgess Reference Burgess2010). This recommendation is also responsive to evidence that physician stress and time pressure are associated with a greater likelihood of making errors and providing suboptimal patient care (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Manwell, Konrad and Linzer2007) and inappropriate prescribing (Tamblyn et al., Reference Tamblyn, Berkson, Dauphinee, Gayton, Grad, Huang, Isaac, Mcleod and Snell1997). Notably, a study of guideline implementation found that the only strategies that improved hypertension management were those designed to reduce physician time pressure and task complexity (Green et al., Reference Green, Wyszewianski, Lowery, Kowalski and Krein2007b).

Improve Organizational Racial Climate

Racial (or diversity) climate has been defined as employees' shared perceptions of the policies and practices that communicate the extent to which fostering diversity and eliminating discrimination is a priority in the organization (Pugh et al., Reference Pugh, Dietz, Brief and Wiley2008). The benefits of medical-school diversity have been shown to vary by the degree to which there was a positive climate for interracial interaction (Saha et al., Reference Saha, Guiton, Wimmers and Wilkerson2008). In a recent national survey, over 70% of Black physicians reported experiencing racial discrimination in their workplace (Nunez-Smith et al., Reference Nunez-Smith, Pilgrim, Wynia, Desai, Jones, Bright, Krumholz and Bradley2009). In another study, 62% of physicians reported that they had witnessed a patient receive poor quality health care because of the patient's race or ethnicity (AMA 2005). These findings indicate medical-care organizational climates that are, perhaps subtly, tolerant of racism. Informal organizational norms that are supportive of racism potentiate the expression of implicit and explicit racial bias and can trigger patient stereotype threat.

Ensure Racial Diversity at All Levels of the Organizational Hierarchy and Promote Positive Intergroup Contact

A meta-analysis of 713 independent samples from 515 studies concluded that intergroup contact typically reduces intergroup prejudice and that institutional support for interaction can increase the benefits of intergroup contact. Contact can reduce future feelings of interracial anxiety and has been shown to generalize from the participants in the immediate contact situation to attitudes toward the entire outgroup (Pettigrew and Tropp, Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2008). A clinic setting with Black staff at all levels is less likely to trigger stereotype threat among Black patients and interracial anxiety among clinicians than one with little diversity or in which only jobs at lower levels of the organizational hierarchy have a diverse workforce (Purdie-Vaughns et al., Reference Purdie-Vaughns, Steele, Davies, Ditlmann and Crosby2008).

Mandate Appropriate and Effective Training Programs and Hold Clinicians and Staff Accountable for Skills and Knowledge

Improving the racial climate includes ensuring that all employees are aware of the impact of racism on quality of care, understand the evidence regarding disparities in care, recognize the impact of stereotype threat, appreciate the importance of respectful interactions, and recognize the potential for bias in their own behavior. Providing training and support for acquiring the skills described above (practicing perspective-taking, partnership building, and emotional regulation) can help clinicians reduce the impact of racism on the care they provide. It is worth noting that some “cultural competence” programs focus on these skills and these may be helpful models, pending evaluation results (Beach et al., Reference Beach, Price, Gary, Robinson, Gozu, Palacio, Smarth, Jenckes, Feuerstein, Bass, Powe and Cooper2005; Betancourt and Green, Reference Betancourt and Green2010).

Existing evidence suggests that with sufficient organizational support, skills training, and available cognitive resources, clinicians high on internal motivation to control prejudice and bias awareness will have considerable success at preventing racism from affecting the quality of care they provide. However, the strategies that will be effective with those who are low on internal motivation to control prejudice are less clear. Awareness that they will be evaluated on their ability to provide equitable care and periodic feedback on equity-related metrics might be very motivating for clinicians and staff. If whole teams or units are evaluated, social norms and pressures may also help clinicians in their goal to provide equitable and just care. A whole-unit (clinic or office) approach is important as nonclinician staff can have a significant effect on patients' medical-care experiences (Barr and Wanat, Reference Barr and Wanat2005).

Carefully Implement Quality Improvement Initiatives, Decision Aids, and Reminder Systems

A number of quality improvement (QI) initiatives have been very successful at reducing inequities in care for a specific condition. Studies involving clinician reminder systems for provision of standardized services (mostly preventive) have had good outcomes (Beach et al., Reference Beach, Gary, Price, Robinson, Gozu, Palacio, Smarth, Jenckes, Feuerstein, Bass, Powe and Cooper2006). QI is likely to be most effective at reducing inequities when there is a clear consensus on the specific steps needed to diagnose and treat a condition and little opportunity for bias in the diagnostic processes. However, in some cases QI strategies have not closed gaps or have been applied unevenly so that White patients were more likely to receive and benefit from the initiative than Black patients (Olomu et al., Reference Olomu, Grzybowski, Ramanath, Rogers, Vautaw, Chen, Roychoudhury, Jackson and Eagle2010).

Partner with Grant Agencies and Researchers to Test Creative, Innovative Strategies

There are some very promising innovative strategies that may seem nonnormative in health care organizations, but have demonstrated impact in other settings that may generalize to clinical environments. Structuring clinician and patient opportunities for self-affirmation may reduce bias and stereotype threat. Self-affirmation treatments have been shown to decrease outgroup derogation, rejection of threatening information, and improve Whites' understanding of racism (Burgess Reference Burgess2010).

Creating an environment in which positive images of Blacks are prominent, for example by filling clinics with artwork and brochures that show admired Blacks and/or Blacks in a positive context, has considerable potential. Evidence from several studies indicates that these strategies may lower both stereotype threat in patients and implicit biases in clinicians (Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Warren, Phelan, Dovidio and van Ryn2010a). Using stories (narrative fiction) to influence perceptions of social norms may be more effective at influencing implicit attitudes than current educational approaches. For example, a radio intervention in Rwanda using stories that portrayed intergroup cooperation changed perceptions of social norms as well as behaviors related to trust, empathy, and cooperation (Paluck Reference Paluck2009).

Summary

It has been eight years since we first proposed an integrated model of the way racism can influence clinician cognition, behavior, and clinical decision making. In this paper we have revised and more fully specified our prior conceptual model in light of recent literature. We made several key points and recommendations, summarized in Table 4. There are significant gaps in knowledge that, if addressed, might substantially advance our ability to make progress in eliminating inequities in health care; these are also listed in Table 4.

Table 4. Summary of Recommendations and High Priority Research Questions

CONCLUSION

There have been over two decades of consistent findings of racial inequities in medical care, including among children, the elderly, cancer patients, and veterans. What explanations are there for the deplorable lack of progress in addressing these morally reprehensible, unjust inequities? In our early writings we avoided using the term “racism” because we were concerned that automatic negative arousal in response to the concept of racism would undermine our effectiveness in drawing attention to the role of clinician bias in perpetuating inequities in care. We face a similar dilemma here. Critical Race Theory points to the way Whites view their social, cultural, and economic experiences as a norm that everyone should experience, rather than as an advantaged position. Explanations for inequality then focus on the failure of outgroups—in this case Blacks—to achieve normal social status (Delgado and Stefancic, Reference Delgado and Stefancic2001; Ford and Airhihenbuwa, Reference Ford and Airhihenbuwa2010). This theory would explain our tendency to focus on Black patients' mistrust and culture rather than White clinicians' racism. However, the notion of “White privilege” is extremely uncomfortable to nonegalitarians and egalitarians alike and has been shown to create hostility and increase racially biased responses (Branscombe et al., Reference Branscombe, Schmitt and Schiffhauer2006; Powell et al., Reference Powell, Branscombe and Schmitt2005). Furthermore, the threat of appearing racist has been shown to trigger stereotype threat for Whites, resulting in higher levels of stereotype-confirming behavior (Goff et al., Reference Goff, Steele and Davies2008).

As individuals and members of institutions in the society in which we live and work, we are all responsible for contributing to solutions and actively striving to eliminate racism. Thus we end with three questions. Why have we devoted so much attention to research and interventions that focus on Black patient mistrust, belief systems, communication and nonadherence and have focused so little on racial bias among clinicians? Why have we done so little to address the health-care-policy and societal factors that cause Blacks to get care at facilities that provide suboptimal quality of care? Are our current dominant approaches the right and appropriate responses given our lack of progress in rectifying the egregious inequities in health care?