The election of President Barack Obama reflects and constructs a new era in racial stereotypes. The good news is that images of Black Americans have quantifiably improved over eighty years of measurement. So-called “Negroes” in 1932, the first year of systematic stereotype measurement, were among the least respected groups in U.S. society but now, by the same measures, fare better than generic Americans and equal other ethnic and national groups (Bergsieker et al., Reference Bergsieker, Leslie, Constantine and Fiskeunder review). Several empirical trends support this salutary state of stereotypes, but each strikes a cautionary note. A running theme will show that social groups and their exemplars, such as Obama, need to be viewed as being simultaneously warm and competent in order to succeed in society (Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Cuddy and Glick2007) and in elections (Abelson et al., Reference Abelson, Kinder, Peters and Fiske1982). Three processes—stereotyping by omission, subtyping by class, and habituating by mere exposure—all framed in the Warmth × Competence model, help explain the Obama phenomena.

STEREOTYPE CONTENT MODEL: IT'S THE WARMTH AND COMPETENCE, STUPID

To understand all these trends, two fundamental dimensions matter: (dis)liking and (dis)respecting (Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Cuddy and Glick2007). Together, these two dimensions of social cognition, respectively warmth-morality and competence-agency, account for as much as 90% of the variance in impressions of individuals and groups (Abele and Wojciszke, Reference Abele, Rupprecht and Wojciszke2008; Wojciszke Reference Wojciszke2005). The dimensions make intuitive, theoretical, and empirical sense. When people first encounter a stranger, they need to know immediately whether the other intends good or ill, hence the sentry's cry: “Halt! Who goes there, friend or foe?” If the other has good intentions, then the other is warm, friendly, and trustworthy. If the other does not have good intentions, then one must be vigilant. Second, people need to know whether the other can enact those intentions: “What can you do [to me or for me]?”

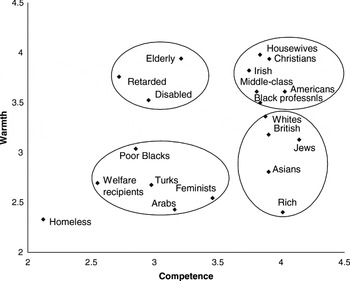

These two arguably adaptive dimensions result in a two-dimensional space, described as the Stereotype Content Model (SCM; see Figure 1). SCM's questionnaire studies ask respondents to describe how society views various groups (see Cuddy et al., Reference Cuddy, Fiske, Glick and Zanna2008, for a detailed review). Ingroups and societal reference groups occupy the proud high-warmth, high-competence quadrant: Americans, Christians, the middle class. At the opposite extreme are society's discards, low-warmth (hostile, untrustworthy, exploitative), low-competence (useless) outsiders, the lowest of the low: poor people of any race, drug addicts, and the homeless. People even dehumanize these lowest of the low, according to both questionnaire and neuro-imaging data: perceivers respond as if these allegedly disgusting outcasts have no mind worth acknowledging (Harris and Fiske, Reference Harris and Fiske2006; Reference Harris, Fiske, Hewstone and Stroebein press).

Fig. 1. Stereotype Content Model placement of common social groups along two fundamental dimensions of warmth and competence, student sample

The remaining, mixed combinations reflect ambivalences that are more novel to consider as stereotypes. Liked but disrespected groups include the elderly and disabled, groups seen as well intentioned but incapable and low status. They elicit pity and tend to receive paternalistic help but also passive neglect. Black people as figures of ridicule (Sambo, minstrels), women as paternalized dolls, and gay men as fey buffoons all inhabit this quadrant.

Finally, another ambivalent combination describes respected but disliked groups who elicit envy, including rich people, all over the world, and in the United States: Asians, Jews, and female professionals. They tend to receive the volatile combination of a going-along-to-get-along obligatory association during periods of stability but active attack when the societal chips are down.

The battle over presidential candidate images illustrates the SCM quadrants. Hillary Clinton struggled for an all-American, middle-class image, rejecting the cold-but-competent female-professional image, as well as the elitist rich-person image in the same part of the space. Housewives sometimes land in the high-high quadrant, but their competence is valued only inside the domestic sphere. And sometimes housewives land in the low-competence, high-warmth part of the space, along with elderly and mentally challenged people. But neither of these roles plausibly fit Clinton. (Sarah Palin, on the other hand, moved between these poles.)

John McCain's image battle was to occupy the American hero, high-high part of the SCM space, avoiding images of both the rich elitist (too many houses to count) and the out-of-touch old guy (can't use the Internet). Surveys suggest that he tripped especially over the age hurdle (Popkin and Rivers, Reference Popkin and Rivers2008).

A later section details Obama's image, but for now, how does the SCM illuminate images of Black Americans in general? Gordon Allport (Reference Allport1954) was one of the first academics to point out the possibilities of mixed stereotypes, when Jews were respected but disliked and “Negroes” were liked but disrespected. We have moved beyond these particular contrasts, but the two core dimensions remain in every country tested (Cuddy et al., Reference Cuddy, Fiske, Kwan, Glick, Demoulin, Leyens and Bond2009) and for all societal groups measured. As the next sections show, the Warmth × Competence space reveals the changing image of Black Americans over time.

Images matter because they predict emotions, which in turn predict behavior (Cuddy et al., Reference Cuddy, Fiske and Glick2007). Intergroup reactions especially demonstrate the way gut feelings drive behavior. Affective prejudices show twice the predictive power of cognitive stereotypes and beliefs in a fifty-year meta-analysis of racial attitudes predicting discrimination (Talaska et al., Reference Talaska, Fiske and Chaiken2008; on individual differences, see Dovidio et al., Reference Dovidio, Brigham, Johnson, Gaertner, Macrae, Stangor and Hewstone1996; on intergroup contact, see Tropp and Pettigrew, Reference Tropp and Pettigrew2005). Clearly, in the extreme cases of hate crimes, people's fringe convictions catalyze strong emotions that drive their murderous behavior (Glaser et al., Reference Glaser, Dixit and Green2002; Pettigrew and Meertens, Reference Pettigrew and Meertens1995). Differentiated emotions target distinct outgroups (see Mackie and Smith, Reference Mackie and Smith2002, for a collection of theories, and Giner-Sorolla et al., Reference Giner-Sorolla, Mackie and Smith2007, for a collection of research), including the special case of African Americans.

And what about presidential voting in particular? The path from images to emotions to behavior describes how people vote (Abelson et al., Reference Abelson, Kinder, Peters and Fiske1982). People's voting decisions derive partly from images: trait judgments of warmth-integrity and competence. For example, in 1980 Ted Kennedy might have seemed competent but untrustworthy (post-Chappaquiddick), whereas Jimmy Carter was less known. Kennedy elicited intense ambivalence, both strongly negative and strongly positive emotions. Carter elicited fewer negative feelings and enough positives to prevail. Overall, people's emotional reactions to the candidates, generated by the two core dimensions of warmth and competence, predict their vote better than that political science workhorse, party identification (Abelson et al., Reference Abelson, Kinder, Peters and Fiske1982). With the SCM Warmth × Competence space and the dominance of emotions as background, we now turn to three stereotyping principles that account for Obama's success.

STEREOTYPING BY OMISSION: ROCK STAR, BUT …

First, as is well-known, most Americans have increasingly rejected publicly maligning ethnic and racial groups, especially when White Americans speak of Black Americans. For example, surveys show a dramatic 75% drop in Americans' racial prejudices reported to interviewers over the twentieth century (Bobo Reference Bobo, Smelser, Wilson and Mitchell2001). Americans' self-presentation and self-concept as nonracist contribute to the emergence of more subtle forms of bias. Unobtrusive measures indicate continuing prejudices (Crosby et al., Reference Crosby, Bromley and Saxe1980; Saucier et al., Reference Saucier, Miller and Doucet2005). These subtle prejudices are more automatic, ambiguous, and ambivalent than lay people suspect (Fiske and Taylor, Reference Fiske and Taylor2008, chap. 11–12). One result of the SCM's ambivalence, just described for the majority of social groups, is an increase in a particular kind of innuendo only possible in a polite society where aversive undercurrents are silenced but understood.

Besides merely suppressing prejudice (though that occurs, too), people increasingly engage in a demonstrable process of stereotyping by omission. In this ambivalent twist, public communication accentuates the positive dimension but by omission implies the negative. For example, in a work setting, solely emphasizing a minority candidate's likeability can implicitly impugn competence. Our data show that moderation of negative stereotypes corresponds to stereotyping by omission (Bergsieker et al., Reference Bergsieker, Leslie, Constantine and Fiskeunder review), and informal observation suggests that this phenomenon appeared in early descriptions of Obama.

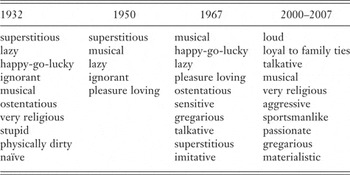

Specifically, a series of studies have detailed American's racial stereotypes since the 1930s. Given the cultural centrality of racial prejudice, social psychology's first studies immediately measured racial and ethnic attitudes (Bogardus Reference Bogardus1933; Katz and Braly, Reference Katz and Braly1933; Thurstone Reference Thurstone1928; see Allport Reference Allport and Murchison1935 for an early review). Particularly enduring, the Daniel Katz and Kenneth Braly (Reference Katz and Braly1933) study documented Princeton undergraduates' stereotypes of ten ethnic, racial, and national groups, and their method replicated twice over the century (Gilbert Reference Gilbert1951; Karlins et al., Reference Karlins, Coffman and Walters1969) and again in twenty-first-century samples (Bergsieker et al., Reference Bergsieker, Leslie, Constantine and Fiskeunder review). Admittedly not representative, but nonetheless a bellwether, this over-time record of stereotypes reveals several notable patterns. Taken all together, the patterns document moderation, ambivalence, and stereotyping by omission—all ultimately setting the stage for Obama's victory.

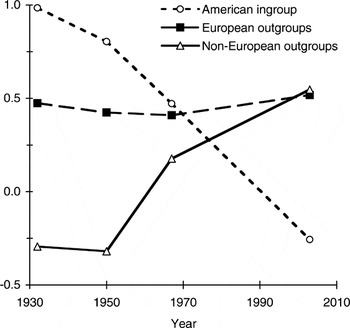

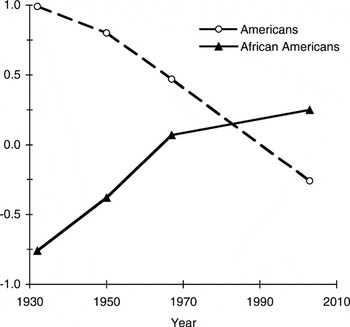

Our analysis, combining the four samples, examined reported stereotypes of ten racial, ethnic, and national outgroups (e.g., Germans, Chinese, African Americans, Jews) from 1932 to 2007 by using the adjective-checklist, “Princeton trilogy” method (Katz and Braly, Reference Katz and Braly1933; Gilbert Reference Gilbert1951; Karlins et al., Reference Karlins, Coffman and Walters1969) with a modern sample. Trend analyses of the top five stereotypic adjectives selected for each group's data gathered in 1932, 1950, 1967, and 2000–2007 revealed that stereotypes remained positive for European outgroups and grew more favorable for “non-European” outgroups, including Black Americans (see Figures 2a and 2b). For groups stereotyped negatively on warmth or competence in 1932, contemporary participants reported either neutral or no stereotypes on the respective negative dimension, whereas stereotypes that were initially positive or neutral did not change—a trend consistent with the stereotyping-by-omission hypothesis. Indeed, Black Americans showed the most dramatic change, over time omitting negative competence-related adjectives such as lazy, ignorant, superstitious, and stupid, while adding positive warmth-related adjectives such as gregarious, passionate, and talkative (see Table 1). A second study, replicating these effects using Likert-scale instead of checklist ratings, also revealed that negative domain-specific stereotypes from 1932 were omitted rather than converted to positive stereotypes over time. (Notably, these results demonstrate that the stereotyping-by-omission phenomenon in the first analysis did not arise from the zero-sum nature of the adjective-checklist task.)

Fig. 2a. Favorability trends for stereotypes of ten social groups, collapsed into European (British, French, German, Italian, Irish, and Jewish), non-European (“Negro” or African American, depending on the sample, Chinese, Japanese, Turkish), and American

Fig. 2b. Favorability trends for stereotypes of African Americans contrasted with generic Americans

Table 1. Changing Content of Black American Stereotypes across Seventy-Five Years

Note: The top ten adjectives selected by Princeton undergraduates in each time period appear in order of descending frequency. For the 1950 sample, G. M. Gilbert (Reference Gilbert1951) reported only the top five adjectives.

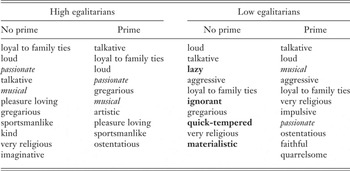

The stereotyping-by-omission pattern over time plausibly relates to changing norms against voicing prejudice—“accentuate the positive, eliminate the negative,” applied to intergroup descriptions. But the causal inference is merely correlational, so a third study manipulated social pressures and measured racial descriptors (Bergsieker et al., Reference Bergsieker, Leslie and Fiske2009). Undergraduates took an ostensible personality quiz that either primed thinking about how others view them (self-presentational pressures) or contained no prime, then completed the adjective-checklist task. Social dominance orientation (SDO; Sidanius and Pratto, Reference Sidanius and Pratto1999) served as an individual-difference measure likely related to reporting stereotypes. As predicted by the stereotype-by-omission hypothesis, making societal norms salient (vs. not) led participants to “omit” mention of lingering negative stereotypes and to select more favorable descriptors instead, but this effect was evident mainly for participants with higher SDO scores. These results suggest that negative stereotypes may still be accessible for less egalitarian participants but will nonetheless be omitted from mention when self-presentation is salient. Black American images show a dramatic effect of social-pressure priming on low egalitarians (see Table 2). Without a social-pressure prime, they alone mention the outdated negative traits “lazy,” “ignorant,” “quick-tempered,” “materialistic,” but when primed, like the high egalitarians, they omit the negative and add the positive traits “passionate” and “musical.” Thus, self-presentational social pressures demonstrably create selective omission of the negative, not the reverse. The competence-related traits “lazy” and “ignorant” do not become “hardworking” and “educated,” but rather give way to warmth-related traits. Negativity on the one dimension is omitted and replaced by positivity on the other dimension.

Table 2. Expression of Black Stereotypes by Level of Egalitarianism and Social Pressures Prime in 2007

Note: The top ten adjectives (including ties) selected by Princeton undergraduates are reported in order of decreasing frequency. Participants were classified as high versus low egalitarians, based on their social dominance orientation scores. The low egalitarian participants who were not primed with social pressures reported the most negative Black stereotypes, as indicated by boldface (for traits that only they selected, including negative competence descriptors) and italics (for positive traits that everyone else selected).

These data demonstrate that racial stereotypes moderate systematically over time, and that stereotyping by omission of the negative dimension while accentuating the positive is a plausible mechanism. First, individuals tend to omit negative dimensions of stereotypes rather than converting them to positive stereotypes, and second, concerns about self-presentation—at least in a context with strong antiprejudice norms—lead people to report more positive stereotypes. Specifically, these findings suggest that negative racial stereotypes do not readily reverse, although they may fade from prominence. Moreover, some increases in reported stereotype favorability may be driven by self-presentation and strategic expression of positive stereotypes for ambivalently stereotyped groups rather than complete changes in stereotype content, particularly among less-egalitarian individuals.

That negatively stereotyped groups may come to be seen more favorably over time is widely accepted; precisely how and why such stereotypes change is less well understood. We assert that negative stereotypes rarely reverse over time (e.g., shifting from “ignorant” to “intelligent”), but instead are omitted and replaced by positive stereotypes in other domains (e.g., “passionate”). We also argue that self-presentational pressures moderate the expression of negative stereotypes.

Stereotyping by Omission, Applied to Obama

Generic stereotypes of Black Americans, at least among relatively egalitarian undergraduates (who arguably provide leading indicators), now emphasize a positive dimension of high warmth-related traits (passionate, gregarious, loyal to family ties, talkative, musical, very religious, sportsmanlike) with some ambiguous potential negatives on that same warmth-sociality dimension (loud, aggressive, materialistic). The very few negative warmth-related traits each provide cover for the respondents because they have mixed connotations: “loud” suggests both gregarious and intrusive; “aggressive” suggests both assertive-competitive and hostile; “materialistic” suggests both U.S. consumption and flamboyance.

Obama's competence has long been unassailable on the credentials front, given his impeccable résumé. Both Maureen Dowd's famous “Obambi” moniker and Hillary Clinton's inexperience argument during the primary attempted to undermine his perceived competence. Attacks on his alleged inexperience attempted to move him from the high-competence part of SCM space, where Black professionals normally land, to the nice-but-incompetent, pitied part of the space.

Obama's Aloha spirit and calm tolerance saved him on the warmth front: even the ambiguously negative warmth-dimension racial images (loud, aggressive) could not plausibly stick. That left microdebates over his fit to other positive warmth stereotypes (passionate, gregarious, loyal to family ties, talkative, musical, very religious, sportsmanlike). Perhaps the most prominent debates were over his being religious enough (and what kind of religion, anyway) and his being passionate enough. But these charges did not stick because of the evidence he relentlessly provided.

Stereotyping by omission occurred when opponents focused on his alleged elitism, implying a lack of warmth and a weak link to Main Street. Overt racism manifested in attempts linking him to aggressive Black power rhetoric, mostly through Reverend Wright, and to alleged terrorism, through ex-Weatherman Bill Ayres. Note that these innuendoes would especially suit low egalitarians not reminded to be socially acceptable, who stereotype Black Americans as aggressive and quick-tempered.

Within the SCM Warmth × Competence space, generic images of Black Americans have measurably improved by focusing on the positive and omitting the negative. This pattern does not eliminate stereotypes but acknowledges their multidimensional ambivalence, which helps explain shifting reactions to Obama.

SUBTYPING BY SOCIAL CLASS: HUXTABLES OR SANFORD AND SON?

The second pattern applies the SCM beyond generic images of Black Americans to subgroup stereotypes held by the general population as well as Black Americans themselves. Barack and Michelle Obama represent to many a healthy Black American middle-class family, fitting television's already-arrived Huxtables or up-and-coming Jeffersons better than down-and-out junkyard owners Sanford and Son. Class distinction matters. Black Americans increasingly distinguish themselves, and are viewed by others, along the lines of class (Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002; Williams and Fiske, Reference Williams2006). Subtyping by class demonstrably divides both self-images and public images of Black Americans.

Starting with public images, early SCM studies, using student and adult samples, located Black Americans in the neutral middle part of the Warmth × Competence space. Gay men also landed in the middle of the model. Because this flew in the face of numerous other indicators of racism and heterosexism, perhaps observers were imagining subgroups that, on average, cancelled out each other's extremes. For gay men, a dozen pretested subgroups ramified out across SCM space, fitting the hypothesis that the whole was the average of its parts (Clausell and Fiske, Reference Clausell and Fiske2005). For societal views of Black Americans, a simple division by social class arrays poor Blacks and Black professionals in SCM space, analyzed in varied convenience samples and a representative sample survey (Cuddy et al., Reference Cuddy, Fiske and Glick2007; Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002) (see Figure 3). Poor Blacks land with poor Whites in the United States and indeed with poor people in a dozen other countries, namely in the contemptible, low-low part of the space (Cuddy et al., Reference Cuddy, Fiske, Kwan, Glick, Demoulin, Leyens and Bond2009; Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002). Black professionals straddle two clusters: On the one side, they appear among the envied high-competence but low-warmth cluster of other professionals, rich people, and ethnic groups stereotyped as entrepreneurs. On the other side, they move toward the pride-inspiring ingroup/reference-group clusters of Americans, the middle class, and Christians.

Fig. 3. Stereotype Content Model placement of common social groups along two fundamental dimensions of warmth and competence, national representative sample. Note placement of poor Blacks and Black professionals

To the extent, then, that Obama achieved prominence as a Black professional and could not plausibly own a poor-Black current identity, he was well positioned in the U.S. public. Viewing Black professionals as embodying the American Dream contributes to non-Black respondents' pride and assurance that the system somehow works. Comparable data in Germany now place Jews, a national group previously subject to genocide and enslavement, in the high-high ingroup space (Eckes Reference Eckes2002). Arguably, such reports might be suspect for groups formerly targeted for the worst subjugation but now at least publicly assimilated. No doubt some social desirability norms enter such reports. But the recent U.S. voting-booth results suggest the reports are not all for show. Arguably, also, the student sample would be especially prone to such biases, although the SCM studies never show demographic differences among respondents, and the student samples replicate the national representative sample. Everyone can report how society views these groups. Thus, the SCM helps to plot the progress of Black American images in the public mind.

From these public images, the SCM moves to intraracial subtypes (Williams Reference Williams2006). Black Americans' heterogeneous experiences generate a variety of Black psychological identities (Sellers et al., Reference Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley and Chavous1998). Especially because discrimination is often more subtle than before, Black Americans have variable race-relevant experiences that depend on context and their own interpretation (Shelton and Sellers, Reference Shelton and Sellers2000). What's more, the growing Black middle class reflects increased disparities in economic, educational, and integration experiences (Massey Reference Massey2007). With variability comes subtyping, including potential for subtyping one's ingroup.

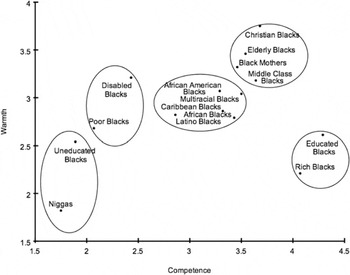

To document this potential variety of intraracial subtypes, twenty Black Princeton undergraduates and eleven Black clients of the Trenton Crisis Ministry community-outreach center listed “different kinds of Black people in America” in response to a young Black male interviewer. The most frequent responses to this open-ended questionnaire were: uneducated Blacks, educated Blacks, rich Blacks, middle-class Blacks, poor Blacks, African Blacks, Caribbean Blacks, multiracial Blacks, Latino Blacks, and “Niggas” (an epithet referenced by comedian Chris Rock for poor urban Blacks). For comparison with prior SCM data, additional subtypes added Christian Blacks, disabled Blacks, elderly Blacks, and Black mothers.

Thirty Princeton undergraduates, self-identified as Black or “Other” (but visually identified as Black by the interviewer), reported being predominantly middle middle-class (43%) or lower middle-class (33%). They rated the fifteen subgroups each on warmth and competence, resulting in a Warmth × Competence space subject to cluster analysis (see Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Stereotype Content Model placement of intraracial Black American subgroups

The resulting subtypes revealed, first, an ingroup/reference-group cluster of Black mothers and middle-class, Christian, and elderly Blacks. For Black voters, Obama's status would have importantly included being middle-class and Christian.

Subtypes for educated and rich Blacks appear even more competent, but significantly less warm; these envied subtypes risk being not “with us” or perhaps “not Black enough.” Some intraracial doubters about Obama probably initially placed him in this quadrant.

The Figure 4 middle neutral cluster could represent intraracial subgroups that had no significant meaning for respondents, genuinely neutral reactions, or combinations that subsume disparate subtypes (for example, multiple kinds of Caribbean Blacks). Obama would not especially inhabit this cluster, there being no neutral subtypes for Hawaiian or Kansan Black people.

A pair of clusters essentially replicates the more general SCM data: the warm-but-incompetent subtypes of poor and disabled Blacks elicit pity. And the low-low, allegedly contemptible “Niggas” and uneducated Blacks bring up the bottom on both dimensions. Even within race, poor people regardless of race may still be subject to ambivalence at best (Russell and Fiske, Reference Russell and Fiske2009) and dehumanization at worst (Harris and Fiske, Reference Harris and Fiske2006).

The poisonous effect of class bias pervades SCM data, regardless of respondent ethnicity or status, and regardless of target race. Socioeconomic status dramatically predicts perceived competence, with correlations hovering above 0.7 across national samples; in the United States, the European Union, and Asia, correlations respectively average 0.81, 0.89, and 0.74 (Cuddy et al., Reference Cuddy, Fiske, Kwan, Glick, Demoulin, Leyens and Bond2009). On a more personal level, in a pair of laboratory experiments, participants expecting to interact with a low-income partner predicted both trait incompetence and low test scores, even after a fully standardized interaction (Russell and Fiske, Reference Russell and Fiske2008; see also Darley and Gross, Reference Darley and Gross1983). And people high on SDO (low egalitarians) especially endorse this status-competence stereotype (Oldmeadow and Fiske, Reference Oldmeadow and Fiske2007). Regardless of race, poor people allegedly deserve their status, through perceived incompetence. The poorest of the poor, homeless people, and their stereotypic cousins, drug addicts, elicit reported emotions of disgust and contempt (Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002). Worse yet, when people view images of various easily identified social groups, along among all outgroups, images of the homeless and the addicted fail to activate brain regions otherwise reliably implicated in appreciating another person's mind (Harris and Fiske, Reference Harris and Fiske2006). This dramatic reversal of established social neuroscience findings shows how low the poor can go in the minds of others.

The poor can aim for ambivalence at best, moderated by their apparent work ethic, struggling against the incompetence image. Undergraduate and adult samples respond to vignettes describing poor people by scorning the lazy and pitying the hard working (Russell and Fiske, Reference Russell and Fiske2009). The default, lazy-poor image is worst off (cold/immoral, incompetent), generating anger and contempt, but the hardworking poor person is apparently more competent, more warm, more pitied, more actively helped.

Notably, social-class bias is hardly confined to intraracial subgroups identified by Black Americans. One implication for Obama is that he totally avoided the low-low stereotype of coming from a poor family because of his evident strong work ethic and his resulting successes later in life. Another implication is that even potentially dehumanized poor people can be rehumanized in other people's view: if perceivers have to think about the target's preferences on matters even as trivial as taste in vegetables, the social-cognition brain regions come back on-line (Harris and Fiske, Reference Harris and Fiske2007). Certainly, voters with any initial images of Obama's low-income origins would have long since preoccupied themselves with at least some of his more important preferences, thereby not easily dehumanizing him as low-class.

Increased complexity allows ingroup differentiation between various low-income Black subtypes and various higher-income Black subtypes for both Black and non-Black voters. Across ethnic lines, Americans generally report pride in middle-class Black professionals as embodying the American Dream. The evolving image of Obama over the campaign, landing in a Huxtable warm-competent role, illustrates this point.

HABITUATION: GROWING ACCUSTOMED TO YOUR FACE

Finally, non-Black Americans are habituating to Blacks in politics, and to Obama in particular. This habituation proved critical because of the automatic emotional reactions of many non-Blacks to Black people. Although many non-Black Americans have rapid, unconscious vigilance reactions to Black faces, these immediate reactions can habituate, with familiarity and empathy (Phelps et al., Reference Phelps, O'Connor, Cunningham, Funayama, Gatenby, Gore and Banaji2000; Wheeler and Fiske, Reference Wheeler and Fiske2005).

First, consider the emotionality of non-Black responses to Black Americans. The speed of people's emotional responses to other people operates in fractions of a second. People register another's race in less than 100 milliseconds (Ito and Urland, Reference Ito and Urland2003), about the same timeframe as deciding whether that other is trustworthy (Willis and Todorov, Reference Willis and Todorov2006). People distinguish ingroup from outgroup and evaluate accordingly, all in half a second or less (Ito et al., Reference Ito, Thompson and Cacioppo2004). Immediate neural responses reflect affect-laden reactions to race (see Eberhardt Reference Eberhardt2005 for a review). The amygdala, a small, deep brain structure, is key here. Implicated in emotional responses, it operates as a kind of vigilance alarm, setting in motion a variety of emotional and cognitive systems (Phelps Reference Phelps2006).

Interracial encounters carry a particular emotional load, according to social neuroscience. Amygdala responses correlate not only with negative implicit associations test (IAT) results but also with indicators of vigilance and arousal, especially in Whites responding to Blacks (Cunningham et al., Reference Cunningham, Johnson, Raye, Gatenby, Gore and Banaji2004; Hart et al., Reference Hart, Whalen, Shin, McInerney, Fischer and Rauch2000; Lieberman et al., Reference Lieberman, Hariri, Jarcho, Eisenberger and Bookheimer2005; Phelps et al., Reference Phelps, O'Connor, Cunningham, Funayama, Gatenby, Gore and Banaji2000; Wheeler and Fiske, Reference Wheeler and Fiske2005).

Whites' control systems also kick in rapidly and successfully, according to neural activity (Amodio et al., Reference Amodio, Harmon-Jones, Devine, Curtin, Hartley and Covert2004; Cunningham et al., Reference Cunningham, Johnson, Raye, Gatenby, Gore and Banaji2004; Lieberman et al., Reference Lieberman, Hariri, Jarcho, Eisenberger and Bookheimer2005; Richeson et al., Reference Richeson, Baird, Gordon, Heatherton, Wyland, Trawalter and Shelton2003). Thus, Whites immediately respond to Blacks as emotionally significant, but also invoke control almost as quickly. Neural activity indexes the speed of these responses. Whites interacting with Blacks show threat-related cardiovascular reactivity, especially if they have limited prior experience in cross-racial interactions (Blascovich et al., Reference Blascovich, Mendes, Hunter, Lickel and Kowai-Bell2001; Mendes et al., Reference Mendes, Blascovich, Lickel and Hunter2002).

None of this vigilance necessarily indicates negative responses, just overactive nerves and internal conflict. After an interracial interaction, Whites also perform poorly on subsequent cognitive tasks, consistent with other evidence that executive control over prejudiced responses has mental costs (Richeson and Shelton, Reference Richeson and Shelton2003). The reverse is also true; Blacks who especially favor their ingroup also incur cognitive costs after interracial interaction (Richeson et al., Reference Richeson, Trawalter and Shelton2005).

Perhaps because of the speed and discomfort of these emotional responses, people avoid interracial interactions from the first moments of attention. People's face-sensitive fusiform gyrus activates less to cross-race than to same-race faces and correlates with whether one remembers them (Golby et al., Reference Golby, Gabrieli, Chiao and Eberhardt2001). This phenomenon is, in effect, a form of perceptual avoidance. And both Blacks and non-Blacks avoid interracial interactions deliberately as well, thinking that the other group will reject them (Shelton and Richeson, Reference Shelton and Richeson2005). To summarize, the emotional loading of race relations has a heavy component of shame and anxiety for Whites, with automatic and more deliberate reactions.

Clearly, non-Blacks differ in their motivation to inhibit prejudice, depending largely on their upbringing (Towles-Schwen and Fazio, Reference Towles-Schwen and Fazio2001). And social norms can override expressed prejudice even for nonegalitarians (as noted earlier, Bergsieker et al., Reference Bergsieker, Leslie and Fiske2009). Salient norms can motivate Whites to inhibit prejudice, to acknowledge discrimination, and to resist hostile jokes (Crandall et al., Reference Crandall, Eshleman and O'Brien2002). Indeed, under pressure of appearing racist, the best-intentioned people actually look even worse than the less well-intentioned people (Frantz et al., Reference Frantz, Cuddy, Burnett, Ray and Hart2004; Shelton et al., Reference Shelton, Richeson, Salvatore and Trawalter2005; Vorauer and Turpie, Reference Vorauer and Turpie2004), and they feel worse about it (Fazio and Hilden, Reference Fazio and Hilden2001). No wonder race is so fraught an issue, making many Whites feel uncertain and anxious in interracial encounters, especially unstructured ones (Towles-Schwen and Fazio, Reference Towles-Schwen and Fazio2003).

Given these automatic—instantaneous and nonconscious—racial reactions, many social psychologists especially worried that the non-Black electorate simply would not be able to shake their first impressions of Obama as Black. Swing voters did at first voice vague discontent, consistent with avoiding the racial issue—“He is too foreign,” “He makes me uncomfortable,” “I'm not sure he is up to the job” (Popkin and Rivers, Reference Popkin and Rivers2008). Much of the campaign debate cited Obama's alleged Muslim identity, his alleged ties to a supposed terrorist, his supposedly not being a “real American,” or doubts over “not knowing what he would do.” One voter whom the senior author canvassed claimed even that Obama would not salute the flag and asked how that squared with her support. Efforts to define Obama as “Other”—such as Sarah Palin's repeated “Do we really know who he is?”—were apparent attempts to play the race card, without seeming to impugn his African ancestry. And they mostly failed. But how could they indeed fail when racial prejudice is so insidious and so underground?

One answer builds on research about overcoming everyday phobias: People grew accustomed to Obama. Over the course of the campaign, and especially the debates, the voters habituated to him. Though they never forgot that he was African American and had a funny name, they experienced two significant things: one, a series of events and the other, a series of nonevents. The series of events created an accretion of evidence that Obama is a three-dimensional human being, closer to a smart middle-class professional with a nice family than to a one-dimensional bogeyman. When people get to know someone from a different category, they add information to the initial automatic category (Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Neuberg, Beattie and Milberg1987). People do not forget the category (Black, female, old, poor). But, on acquaintance, they can overwhelm it with additional individuating information, if that information is available, if it is unambiguous (so they can't distort it), and if they are motivated to acquire it (Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Lin, Neuberg, Chaiken and Trope1999; Fiske and Neuberg, Reference Fiske, Neuberg and Zanna1990). All these conditions held for the undecided but open-minded voters. Balanced against all that additional knowledge, especially because new information was unambiguous and not stereotypic, the category could recede. In the end, voters probably subtyped him as a Black professional, and given that the average American reports being proud of Black professionals, seeing them as competent, good people, this helped Obama's chances. In any event, people learned enough about Obama to complicate any initial stereotypes.

The campaign created not only the image-refining events that individuated Obama and thereby habituated voters, but the campaign also created a series of nonevents. Part of what happened was what did not happen. To the extent that non-Black people found him alarming at first, their brain's amygdalae would have been on high alert, vigilant for danger. But they kept encountering him in the least alarming, most reassuring series of nonevents. He never lost his temper. He never appeared hostile. He hardly ever even frowned. Frequent exposure to an otherwise fear-inducing stimulus in a safe environment allows people to relax. And they evidently did.

Over the course of the campaign, non-Black voters habituated to Obama, getting used to him. They could let down their guard because of both events and nonevents. The events included his performance, his race speech, and his featuring his family; all this provided competence and warmth information beyond category membership. The nonevents were his outer calm; despite provocation and fatigue, he never appeared hostile, angry, or disapproving. These safe, warm responses allowed nervous non-Blacks to grow accustomed to him. The downside of this requirement for habituation is that a Black public figure cannot afford to display anger, as many people know privately.

CONCLUSION

Three social psychological processes—stereotyping by omission, subtyping by class, and habituating by exposure—not only help explain Obama's ascendance but also suggest how images of Black Americans and Obama could change in the future. These processes may well determine whether positive evaluations of Obama generalize to Black Americans more broadly, and how perceptions of Obama evolve as his presidency progresses and his performance undergoes continual scrutiny. Will non-Blacks who have come to identify with Obama (as was perhaps most evident in the “I am Obama” messages that emerged on YouTube and in pro-Obama ad contests) now feel more strongly connected to their Black neighbors, co-workers, and classmates? Will Obama pay a higher popularity price than most for the missteps common to all leaders? The social psychological evidence supports cautious optimism.

In a sense, our nation is enacting in its highest office the “talented tenth” approach advocated by W. E. B. Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1903) a century ago, insofar as it is enabling a gifted and well-educated Black man to rise to prominence and potentially reshape perceptions of Black Americans. Du Bois recognized lack of familiarity with outstanding Blacks as one source of Whites' negative stereotypes about Blacks, noting, “You misjudge us because you do not know us” (p. 34). This intuition also relates to our habituation argument: the extended attention that Obama garnered during the primary and general election campaigns allowed non-Blacks to come to know and ultimately like and respect him. That more exposure typically leads to liking is well established (Zajonc Reference Zajonc1968) and generally holds true for intergroup contact (Pettigrew and Tropp, Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006). Nevertheless, the precise amount of neutral-to-positive Obama exposure needed to counteract negative portrayals of Blacks that are habitual in the media (Entman Reference Entman1994) remains an open question. As the term talented tenth implies, Du Bois's vision involved a critical mass of gifted Blacks attaining an education and rising to positions of influence, thus generating broad-based habituation to Black excellence, not just a “talented one” (or “talented few,” if including Obama advisors Susan Rice, Eric Holder, and Valerie Jarrett and supporters Oprah Winfrey and Colin Powell). Unless non-Blacks can habituate to a broad array of exemplary Black Americans, their positive views of these exemplars may not extend to Blacks whom they encounter in everyday life.

Probably the largest obstacle to impressions of Obama generalizing is subtyping, with subtyping by social class particularly potent. Have non-Blacks come to see Obama as an “American like us, who happens to be Black” or an “American, unlike other Blacks”? This concern, too, harks back to Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1903), who observed that as soon as the talented tenth emerges, people “cry out in alarm: ‘These are exceptions, look here at death, disease, and crime—these are the … rule’” (p. 43). Social psychological research suggests that this perceptual gap between a proverbial talented tenth and other group members can be bridged, but with limitations. Exposure to Black celebrities who are liked and respected (e.g., Oprah Winfrey, Colin Powell) leads Whites to respond more favorably to Blacks both explicitly (Bodenhausen et al., Reference Bodenhausen, Schwarz, Bless and Wänke1995) and implicitly (Dasgupta and Greenwald, Reference Dasgupta and Greenwald2001). Strikingly, however, this generalization from Black celebrities to Blacks in general disappears when Whites are first asked to consider how typical the individuals are of Blacks as a group (Bodenhausen et al., Reference Bodenhausen, Schwarz, Bless and Wänke1995, study 3). Moreover, Whites are slower to categorize admired Black individuals as Black than they are to categorize disliked Black individuals (Richeson and Trawalter, Reference Richeson and Trawalter2005), a bias that could also inhibit a positive Obama aura from impacting images of Black Americans.

Non-Blacks (as well as Blacks, of course) also respond to Blacks' skin tone (Maddox Reference Maddox2004). Obama is biracial, a fact relevant to his popular acceptance. Indeed, he referred quite often to his upbringing by hardworking White Kansans both because it was true (and formative) and because his White heritage made him more palatable to his White public. Although he is phenotypically identifiable as Black, his biological connection to the White community means he is not completely an outgroup, and some discourse within the Black community doubts he would have been elected without it. Also, children of immigrant Blacks tend not to be as handicapped by racial prejudice as native-born Black Americans (e.g., Deaux et al., Reference Deaux, Bikmen, Gilkes, Ventuneac, Joseph, Payne and Steele2007). These factors also led to subtyping him by class (and status), which would slow the generalization from him to other Black Americans.

If typicality and categorization impediments can prevent positivity from generalizing to Blacks as a group, the subtyping barrier that separates liked and respected Black celebrities from disliked and disrespected poor Blacks could prove almost insurmountable and a contrast effect could predominate.

Whereas habituation and subtyping both explain how an extraordinarily talented Black individual can rise to power despite negative stereotypes about Blacks, the stereotyping-by-omission phenomenon highlights that Obama's success may be to some extent due to the ambivalent, multidimensional, and partially omitted content of these stereotypes. Because Blacks in general may be seen as warm, loyal, outgoing, and pious (yet incompetent), while Black professionals are seen as competent and successful (yet elitist), Obama managed to incorporate the positive elements of each of these stereotypes. At the same time, these ambivalent stereotypes highlight his areas of vulnerability: His first missteps, depending on their domain, may readily be judged as reflections of stereotypic general Black incompetence or professional Black elitism. Indeed, women and minorities who achieve positions that are not stereotypical for their group may experience “status fragility” in which they are penalized more harshly than male or White counterparts for comparable mistakes (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Brescoll and Uhlmann2008). Especially if the negative elements of these stereotypes have merely gone undercover, rather than disappearing—as evidenced by the negative stereotypes that low egalitarians who were not primed with social pressures reported (Bergsieker et al., Reference Bergsieker, Leslie and Fiske2009)—people may interpret any Obama failures through the lens of these negative images. Also, returning to the implications for Black Americans collectively, the stereotyping-by-omission phenomenon suggests stagnation rather than progress in domains of historically negative stereotypes. Stereotypes of Black incompetence, for example, prove persistent—insofar as the contemporary failure to describe positive competence implies neutral or even negative competence. Non-Blacks may take a long time to see Blacks just as positively on that dimension as any other group.

Simultaneous processes of stereotyping by omission, social-class subtyping, and habituating by exposure can explain how changing images of Black Americans enabled Obama's election. Few realistic observers expect Obama's presidency to introduce overnight a utopian era in interracial understanding. Nevertheless, during his first term in office, these three phenomena offer valuable insights about whether, how, and to what extent his success can transform images of Black Americans, as well as whether racial stereotypes may constrain or enable him.