Introduction

At the end of World War II, with thousands of troops returning home from Europe and the Pacific Islands, American political elites faced a dilemma. Having spent years fighting a war caused in large part by a global depression, they now confronted the very real risk of yet another significant economic downturn (Tooze Reference Tooze2014).Footnote 1 The combined effects of high unemployment, low economic growth, and a restive population of returning soldiers, threatened to produce dangerous political instability at home. Policymakers addressed these linked threats by encouraging home buying and new home construction. Making use of agencies created in the early years of the New Deal—like the Federal Housing Administration (FHA)—federal officials issued loans that made possible the construction of public housing within American cities, and huge numbers of single-family homes in the emerging American suburbs (Jackson Reference Jackson1985; Sander et al., Reference Sander, Kucheva and Zasloff2018).

One feature of the federal government’s broader housing program, we now know, was residential segregation by race (Rothstein Reference Rothstein2017). Redlining, restrictive covenants, and the explicitly discriminatory practices of banks and developers, ensured that new suburbs would be reserved for White Americans. “From its inception,” explains urban planner Charles Adams, “FHA set itself up as the protector of the all-White neighborhood” (quoted in Jackson Reference Jackson1985, p. 214).Footnote 2 Housing patterns in the post-war era were primarily characterized by White families financing their escape from areas experiencing racial change. The consequences of “White flight” from America’s urban centers were dramatic. Kenneth Jackson (Reference Jackson1985) demonstrates a clear link between income and suburbanization, finding that “in 1970, the median household income of cities was 80 percent of that in the suburbs. By 1980 it had fallen to 74 percent, and by 1983 to 72 percent” (p. 8). At the same time, public housing was increasingly “ghettoized” in American cities. By the 1960s, living conditions for Black citizens in many American cities were unbearable. Urban neglect, segregation, and White flight produced an environment ripe for unrest, and violent uprisings soon spread across the country.Footnote 3

The epidemic of urban disorder revealed that America’s race problem was not confined to the South, so voting rights alone could not be a solution. Riots in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, for example, took place less than one week after President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.Footnote 4 To address the social and economic problems caused by residential segregation, the federal government would need to intervene in the housing market, a choice that would have a dramatic impact on property owners both North and South. Fair housing legislation would challenge the rules and practices that allowed northern and midwestern cities to segregate. National implications of this kind are particularly problematic because, as had been true since the “first civil rights era” (1861–1918), White northern support for civil rights policies held only so long as most of the rules applied to southerners alone.Footnote 5 Indeed, per Joshua Zeitz (Reference Zeitz2018), northern Whites “instantly revolted against the Great Society when that struggle came to their schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods. The backlash that LBJ’s team had feared in 1964 finally seemed primed to materialize, and in 1966 it crystallized around the issue of open housing” (p. 242).Footnote 6

We pursue two goals in this paper, following from the dynamic we have just described. First, we provide a legislative policy history detailing how Congress came to enact the fair housing provision of the Civil Rights Act of 1968. Unlike the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Johnson’s administration’s third civil rights initiative has received considerably less scholarly attention.Footnote 7 We remedy this through an examination of congressional proceedings, individual roll-call votes, and eventual policy outcomes associated with fair housing legislation. We also pay particular attention to the pivotal role played by a small group of Republican legislators whose strategic behavior helped defeat fair housing legislation in 1966, and then helped pass a significantly weakened version two years later.

Second, we identify the politics of fair housing as an important turning point in the long history of race politics in the United States. Just as the first civil rights era stalled in the mid-1870s as Congress considered policy that would significantly impact the lives of White northerners, we argue that the “second civil rights era” (1919–1990) witnessed a similar challenge.Footnote 8 Congress’s pursuit of legislation to make housing discrimination illegal would apply to properties in both the North and the South, which led many ostensible allies of the civil rights movement in the North to hesitate and thus threaten the entire project. While a bill did eventually pass in 1968, after three years of heated politicking, it fell far short of its sponsors’ initial aspirations. The fight over fair housing, we argue, foreshadows more than a decade of virulent battles on race-related policy that would be structured by both region and party. From the congressional perspective, momentum from this point forward now shifted back toward those seeking to block or reverse gains made in the early part of the 1960s.

To guide the analysis, we begin by detailing the first, failed effort to enact fair housing policy beginning in 1966, during the 89th Congress (1965–1966). Next, we detail its eventual success (in a lesser form) in 1968, during the 90th Congress (1967–1968). In conclusion, we discuss how the politics of fair housing legislation follows a pattern that has long defined congressional action on civil rights policy.

Political Misjudgment: Fair Housing Legislation in the 89th Congress

Not long before the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which held that school segregation violated the equal protection clause of Fourteenth Amendment, a different integration struggle came to a far more ambiguous conclusion. In the early 1950s, the NAACP and local civil rights advocates in Chicago, IL sought to integrate that city’s residential neighborhoods. These activists were ultimately defeated by the city’s political leadership, who proved more than willing to abide violent opposition from White Chicagoans opposed to integration. Ten years later, Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Congress (SCLC) renewed the fight to integrate Chicago, braved a violent White backlash, and were forced to leave the city having achieved few of their aims. The problems that plagued King and his allies in Chicago demonstrate the extent to which residential integration “exposed the political and ideological limits of the civil rights era” (Hirsch Reference Hirsch1995, p. 523).Footnote 9

At almost the same time SCLC activists were struggling to end housing discrimination in Chicago, some members of Congress sought a federal policy outlawing racial discrimination in the sale, purchase, and rental of homes. This was not Congress’s first effort to ban race-based housing discrimination. Almost one century earlier, the Republican Party included a provision in the Civil Rights Act of 1866—the first civil rights bill to ever pass Congress—formally prohibiting discrimination in the “inheritance, purchase, lease, sale, holding, or conveyance of real and personal property.”Footnote 10 Despite this provision, with the end of the “first civil rights era” and the rise of Jim Crow, significant housing segregation emerged in both the North and South. As late as 1930, the federal government had taken no action to regulate or monitor local housing markets and at the outset of the Great Depression, residential segregation was “firmly established” throughout the country (Sander et al., Reference Sander, Kucheva and Zasloff2018, p. 84).

Civil rights activists recognized and worked to end the social and economic inequality resulting from residential segregation. When announcing his plans to begin SCLC’s Chicago Freedom Movement, Martin Luther King identified his “primary objective” as the “unconditional surrender of forces dedicated to the creation and maintenance of slums and ultimately to make slums a moral and financial liability upon the whole community” (quoted in Garrow Reference Garrow1999, p. 457). He was echoed by northern activists like Clarence Funnye—one-time director of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in New York—who sought to eliminate “the ghetto, with its attendant ills of slums, inadequate schools, high crime rates, poor police protection, inadequate services, and feeling of hopelessness on the part of the inhabitants” (quoted in Sugrue Reference Sugrue2008, p. 413). Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the “open housing movement” attracted supporters from across the country. The number of local branches of the National Committee Against Discrimination in Housing (NCDH)—the most significant open housing advocacy organization in the country—grew from eighteen in 1959 to more than one thousand in 1965 (Sugrue Reference Sugrue2008).

Reflecting these trends, President Johnson used his 1966 State of the Union Address to call on Congress to “prohibit racial discrimination in the sale or rental of housing.”Footnote 11 Three months later, in April 1966, the administration went a step further, sending Congress a broad civil rights bill aggregating various policy proposals supported by different factions of the broad Civil Rights Movement.Footnote 12 The bill sought to end discrimination in the selection of federal and state jurors (Titles I and II), to authorize the Attorney General to initiate legal action against those suspected of discriminating in public schools and accommodations (Title III), and to provide federal protection to civil rights workers (Title V). The fair housing provision (Title IV) proved to be its most controversial section. It aimed to make illegal discrimination in the sale and rental of all new and existing housing stock. To enforce this prohibition, the plan relied on victims of discrimination to pursue damages in the court. The bill also would have empowered the Attorney General to bring so-called “pattern-of-practice” lawsuits against those suspected of repeated, systematic discrimination in the sale or rental of housing.Footnote 13

The Democratic Party controlled both chambers in the 89th Congress. In the House of Representatives, they held a commanding 295-140 advantage; in the Senate, they retained a majority of 68-32. Northern Democrats had overseen the passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act earlier in the Congress, in August 1965, which complemented and extended the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (enacted in the 88th Congress). But the political world had changed in a short amount of time. As Gary Orfield (Reference Orfield1975) notes: “Urban riots, the emergence of the Black power movement fragmenting civil rights organizations, and a strong movement of White public opinion against further rapid change” coalesced and stymied the Democrats (p. 87). Case in point: the number of Americans who viewed civil rights as “the most important problem” in the country, per the Gallup Poll, declined from 52% in March 1965 to 27% in September 1965 to 9% in May 1966.Footnote 14 For many White Americans, the CRA of 1964 and VRA of 1965 were sufficient when it came to new federal civil rights policy, and they preferred lawmakers to move on to other matters. Amid this public opinion change, southern Democratic members, who were dead-set against any civil rights legislation, stood in opposition. To pass, a new civil rights bill would need support from sympathetic Republicans representing largely non-southern, White constituents. Given the new context, northern Democrats would need to fight hard for their votes.

Well aware of the political headwinds they faced, the administration pursued what Hugh Davis Graham (Reference Graham1990) describes as its “customary House-first strategy.” In the House, the bill would be sent to the Judiciary Committee led by Emmanuel Celler (D-NY), a northern liberal. In the Senate, it would have faced immediate opposition from James Eastland (D-MS), who led the Judiciary Committee. Under Celler’s leadership, the House Judiciary Committee would work to craft a bill that took into consideration the policy preferences of “dependable Republican moderates … whose bargains tended to command bipartisan respect and hence to stick” (Graham Reference Graham1990, p. 260). Once persuadable House Republicans bought in, the administration and its supporters believed, it would be easier for Senate Democrats and moderate Republicans to overcome the inevitable, southern-led filibuster.

In early May 1966 the administration began its push to win support for the bill (H.R.14765), as Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach was dispatched to the House to give testimony on its behalf. In his opening statement, Katzenbach highlighted the fact that 100 years after Congress approved the housing provision of the 1866 Civil Rights Act, housing remained “the one commodity in the American market that is not freely available on equal terms to everyone who can afford to pay” (United States Congress 1966, p. 1067). “Segregated living is both a source and an enforcer of involuntary second-class citizenship,” he continued (United States Congress 1966, p. 1070). The constitutionality of Title IV—of which Katzenbach claimed to have “no doubts whatsoever”—was therefore guaranteed by both the Fourteenth Amendment and the Commerce Clause (United States Congress 1966, p. 1070). Importantly, Katzenbach also signaled to the committee that the Administration was open to compromise on the bill. In particular, he suggested that they would be willing to exempt particular kinds of residences from the law (United States Congress 1966, p. 1201). Compromise of this kind would prove particularly important in the weeks ahead.

Despite Katzenbach’s best effort to both defend the bill and demonstrate the administration’s flexibility, pivotal Republicans immediately condemned the housing language. After reading the proposal, Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen (R-IL) told an interviewer, “if you can tell me what in interstate commerce is involved about selling a house fixed on soil, I’ll eat the chimney on the house” (Freeburg Reference Freeburg1966). Senator Jacob Javits (R-NY), usually one of the “dependable Republican moderates” needed to push civil rights legislation through the upper chamber, also predicted that the housing provision would destroy any chance for the bill to overcome a filibuster (Albright Reference Albright1966). Making matters worse, Title IV provoked sustained opposition from the National Association of Real Estate Brokers (NAREB). This organization boasted 83,000 members, many of whom deluged Congress with calls and letters declaring, “a man’s home is his castle” to dispense with however he chose (Franklin Reference Franklin1966a). For the bill to pass, it would need to calm those members who argued that, as written, it would deprive citizens of the basic right to choose how best to rent or sell personal property.

Celler also led the subcommittee responsible for marking up H.R. 14765, and he commenced a series of hearings for that purpose in 1966. In June, the subcommittee met in executive session for nine days to craft new language reflecting the testimony they received. The full committee then met for an additional nine sessions, during which time Charles Mathias (R-MD) crafted an amendment to Title IV intended to win over moderate Republican holdouts. According to Mathias, it was important to distinguish “the large-scale commercial activities involved in selling or renting … from the property transactions of the individual homeowner or small landlord” (Mathias and Morris, Reference Mathias and Morris1999, p. 22). Stated differently, the Mathias compromise would have allowed individuals, “small landlords,” or sellers who did not use brokers/agents to discriminate against renters/buyers without fear of being punished. Fair housing “compromises” repeatedly make provision for some forms of intentional discrimination against Black citizens.

On June 27, the administration made public its willingness to accept exemptions (Herbers Reference Herbers1966a). Then, on the following day, the committee met in executive session to vote on a number of amendments aiming to make the bill palatable to conservatives. The Mathias exemption was one of those considered and, on the first vote in committee, it went down to defeat. The committee then took up a motion to remove the housing provision entirely. This motion failed 15-17, thereby allowing for additional negotiations (Herbers Reference Herbers1966b). After another night of wrangling, Mathias brought his amendment back to the committee where, on June 29, it was adopted in a vote of 21-13. On this vote, Democrats voted 17-6 in favor of Mathias’ proposal while a majority of Republicans, 4-7, opposed (Congress and the Nation 1969). The House Judiciary Committee also adopted, by a vote of 13-4, an amendment offered by John Conyers (D-MI), which proposed to create a Federal Fair Housing Board with enforcement powers like those of the National Labor Relations Board.Footnote 15 With these two changes made, the committee then sent H.R. 14765 to the floor.

In order to force the House of Representatives to consider H.R. 14765, Celler chose to maneuver around the Rules Committee which, being led by Howard Smith (D-VA), was likely to scuttle the bill. Celler invoked the 21-day rule, which allows bills approved by a committee but bottled up without a rule to govern debate on the floor, to be brought up for consideration by a majority vote of the entire House. Celler’s strategy engendered opposition from minority leader Gerald Ford (R-MI), who condemned the move and called upon his members to oppose Celler.Footnote 16 Democrat Howard Smith responded by pledging that his committee would hold hearings on the bill if only members would vote against Celler’s resolution.Footnote 17

Despite bipartisan opposition, the vote to invoke the twenty-one-day rule (formally taken through a roll call vote on H.R. 910) passed, 200-180. As Table 1 illustrates, Northern Democrats, aided by just enough southern Democrats and Republicans, pushed the resolution through.Footnote 18 Opposition to H.R. 910 came from the “conservative coalition,” as an overwhelming majority of Republicans voted with a majority of southern Democrats to try and block consideration of the measure.

Table 1. Votes on Civil Rights Act of 1966, 89th Congress

Source: Congressional Record, 89th Congress, 2nd Session (July 25, 1966), 16058; (August 9, 1966), 17914; (August 9, 1966): 17914; August 9, 1966): 17915.

Source: Congressional Record, 89th Congress, 2nd Session (August 9, 1966), 17916; (August 9, 1966), 17916; (September 14, 1966): 22670; (September 19, 1966): 23042-43.

(1) To agree to H. Res. 910, the rule permitting consideration of H.R. 14765, the Civil Rights Act of 1966.

(2) To amend H.R. 14765, the Civil Rights Act of 1966, by permitting a real estate broker or his agent to discriminate in the sale or rental of a dwelling on express written instruction to do so from an owner otherwise exempt, provided the broker or agent did not encourage or solicit the instruction. (Mathias Amendment)

(3) To amend H.R. 14765, the Civil Rights Act of 1966, by making it a federal crime to travel in interstate commerce or to use the mails with intent to incite or commit riot, to commit an act of violence or any state or federal felony or to assist or encourage commission of such acts. (Cramer Amendment)

(4) To amend H.R. 14765, the Civil Rights Act of 1966, by requiring a complaint in writing to the attorney general from a person deprived or threatened with loss of equal protection of the laws before the attorney general filed suit to desegregate public schools or facilities. (Whitener Amendment)

(5) To recommit H.R. 14765, the Civil Rights Act of 1966, to the judiciary committee with instructions to delete Title IV, the open housing title.

(6) To pass H.R. 14765, the Civil Rights Act of 1966.

(7) To invoke cloture on Hart motion that the Senate proceed to consider H.R. 14765, the Civil Rights Act of 1966

(8) To invoke cloture on Hart motion that the Senate proceed to consider H.R. 14765, the Civil Rights Act of 1966.

This procedural victory, however, did not signal that the Judiciary Committee’s version of H.R. 14765 had the votes to pass. In the days immediately afterward, the bill’s supporters were forced to concede that winning a majority would likely require the fair housing provisions to be weakened (Lyons Reference Lyons1966a; Stewart Reference Stewart1966a, Reference Stewart1966b). These rumors, in turn, angered important supporters of the bill. Roy Wilkins, then-executive director of the NAACP, responded to rumors that further compromises would be needed by declaring that exempting any more homes from coverage would ensure “that the suburbs would remain virtually lily-white and the center city ghettos would become poorer, blacker, and more desperate than at present” (Franklin Reference Franklin1966b). Stokely Carmichael, then leading the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, referred to the bill as “a sham” (Franklin Reference Franklin1966b). The New York Times even quoted one “high administration official’s” lamentation about the dilemma faced by the administration and its allies in the House. “If we get the bill passed it’s a fraud,” argued this source, “but if we don’t it looks like another racial insult” (Franklin Reference Franklin1966c). Republicans, meanwhile, refused to take a formal position. After a meeting with Roy Wilkins, Gerald Ford told reporters that “it was his disposition not to support open housing” but that “aside from the open housing section … the bill deserves support” (Chicago Tribune Press Service 1966).

Mathias soon validated the rumors about changes to further weaken Title IV. On August 3, he offered a perfecting amendment to the Judiciary Committee’s bill stipulating that agents/brokers would be allowed to discriminate without threat of punishment when selling/renting an already exempted home/apartment. Defending this change, Mathias claimed that his amendment “neither strengthens nor weakens the bill. It simply repeats in the active, permissive tense what is already passively implicit.”Footnote 19 Anticipating objections from more liberal members and from civil rights activists, Celler defended Mathias’ amendment. “The all-or-nothing attitude produces nothing except a slogan,” he asserted.Footnote 20 Celler recognized that strong fair housing provisions simply could not pass. Compromise meant allowing discriminatory practices to continue.

In order to demonstrate that stronger language would not pass, Democratic leadership allowed a teller vote on a substitute amendment offered by Clark MacGregor (R-MN). The MacGregor amendment proposed a uniform prohibition on discrimination in the sale of all housing. It failed 186-76. Next came a teller vote on the Mathias amendment. It passed 180-179, when the presiding officer, Richard Bolling (D-MO), cast the tiebreaking vote.Footnote 21 While no official vote roll call record exists, news accounts suggest that the Mathias amendment won only 20-25 Republicans. These same reports also suggest that the opposition came from a coalition of conservatives who wanted no housing legislation whatsoever, and liberals who believed that the amendment would fatally weaken the bill (Lyons Reference Lyons1966b). Gerald Ford was reportedly not one of the “yea” votes (Herbers Reference Herbers1966c).

For civil rights advocates seeking open housing language closer to what the administration submitted to Congress, the Mathias amendment was difficult to accept. Contemporaneous estimates suggested that when put into effect the Mathias amendment would reduce the number of homes covered under fair housing protections from sixty million to twenty-three million (United Press International 1966a). Yet after six additional days of debate on the overall bill, hesitant liberals would need to accept more disappointment. On August 9, a rewritten Mathias amendment came up for a roll call vote. The new language allowed homeowners of all existing homes the freedom to direct their agents/brokers to discriminate, but made clear that such direction could not be legally solicited by the agent/broker. As long as the order to discriminate against Black buyers came from the seller, it was legal. Table 1 records the vote on the Mathias amendment. Here we see that the Republican Party split, with nearly an equal number of Republican members voting for and against the Mathias proposal. Northern Democrats voted overwhelmingly for the amendment, while southern Democrats overwhelmingly opposed.Footnote 22

Mathias’s amendment was not the only change to H.R. 14765 put to a roll call vote. The House also voted overwhelmingly, 389-25, to adopt an amendment written by William Cramer (R-FL) making it illegal to travel between states for the purpose of “inciting a riot.”Footnote 23 Anti-riot legislation emerged at this point as a tool used by segregationists to punish those suspected of organizing protests and civil disobedience in American cities.Footnote 24 The House also voted for language crafted by Basil Whitener (D-NC) requiring the Attorney General to “have received a written complaint of denial of equal protection of the laws before instituting a suit to desegregate public schools or facilities” (Congress and the Nation 1969, p. 370). This provision made it more difficult for employees of the Justice Department to spearhead discrimination suits against places ostensibly covered by civil rights laws already on the books. As Table 1 illustrates, this amendment won overwhelming support from the “conservative coalition.” It only passed, however, because 29 Northern Democrats voted with the conservatives.Footnote 25

Before the final passage vote, proponents of H.R. 14765 faced one more obstacle. Representative Arch Moore (R-WV), seeking to kill Title IV specifically, introduced a motion to recommit the bill to the Judiciary Committee with instructions to strike the housing provisions.Footnote 26 Moore’s motion won support from the conservative coalition: 80 of 92 southern Democrats and 86 of 146 Republicans voted for it. Moore’s effort failed, however, 190-222 (See Table 1). The Republicans displayed the most heterogeneity on this key procedural vote, so we examine the determinants of GOP vote choice. Specifically, we examine the ideological, racial, electoral, and state-level factors that may explain why these Republicans voted as they did.

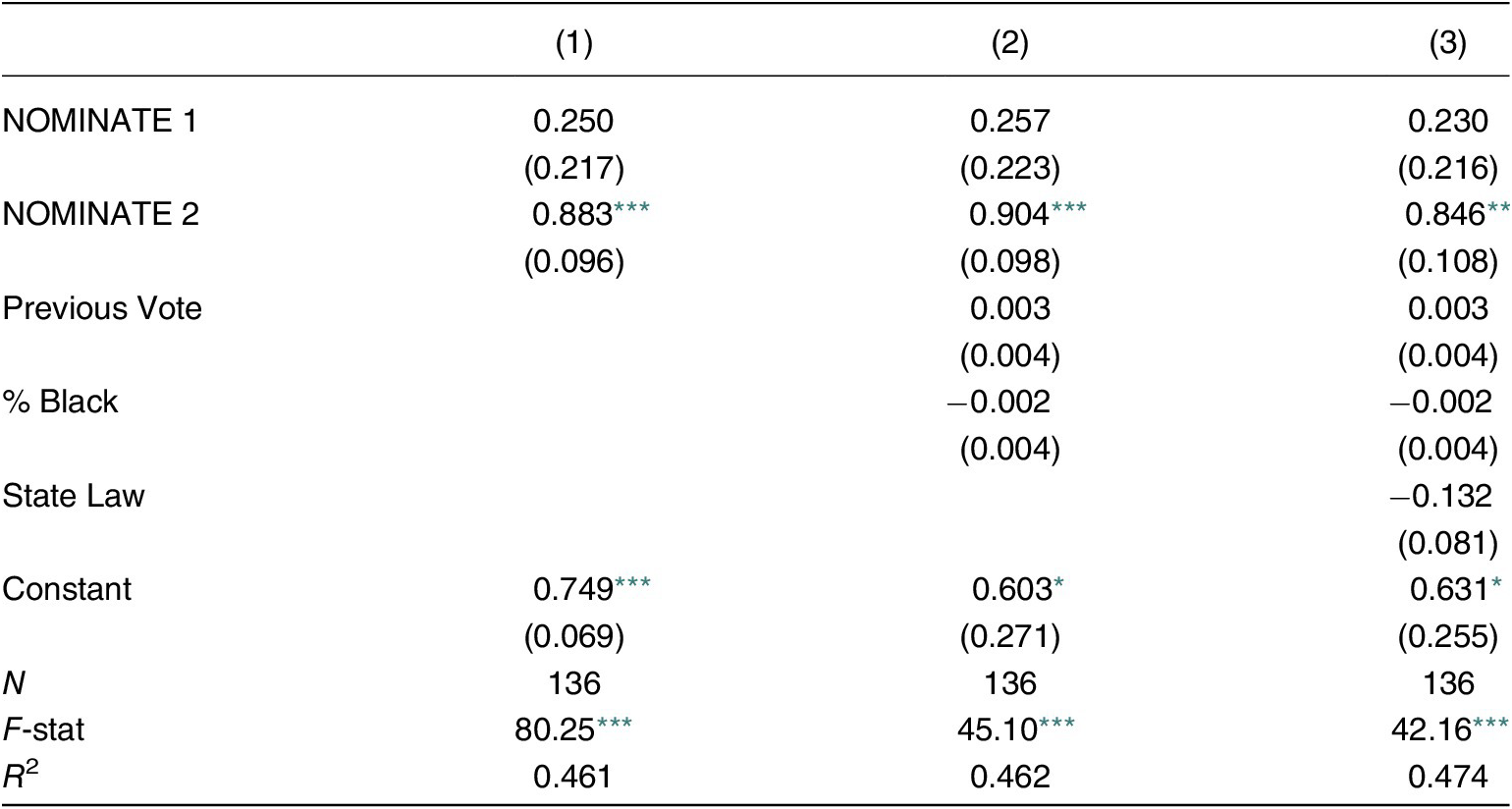

The dependent variable in this model takes a value of 1 for those members who voted “yea” on the proposal to recommit H.R. 14765 with instructions to strip out the housing language, and 0 for those members who voted “nay.” In terms of independent variables, we include standard measures of member ideology, first- and second-dimension DW-NOMINATE scores.Footnote 27 NOMINATE stands for “nominal three-step estimation,” and uses roll-call votes as inputs to scale legislators from left to right on one or more issue dimension. NOMINATE scores —the outputs from the estimation procedure—range from -1 (liberal) to +1 (conservative), with a single (first) issue dimension (capturing conflict over economic redistribution, or the role of the government in the economy) having the most explanatory power. A second issue dimension is sometimes important, as it was during the 1960s, and captured preferences on civil rights—again ranging from -1 (liberal) to +1 (conservative).Footnote 28 We also include the percentage of Black voters in the member’s home district, the member’s percentage of the two-party vote in 1964, and whether a switcher’s home state already had enacted a strong fair housing law. Results of a linear probability model on Republican votes on the motion to recommit appear in Table 2, in three columns (with various independent variables included).

Table 2. Linear Probability Model of House Republican Votes on Motion to Recommit with Instructions, 89th Congress

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. The DV =1 if the Republican House member voted “yea” on the motion to recommit with instructions (to return the bill to committee and delete the fair housing provision), and 0 if “nay.”

* p < .05

** p < .01

*** p < .001

We find that ideological differences along the civil-rights dimension do most of the work explaining this vote, as the second NOMINATE dimension is positive and significant.Footnote 29 This indicates that House Republicans who were more conservative on racial issues were more likely to vote to recommit H.R. 14765 and seek to delete the fair housing title. None of the other variables, including intra-GOP differences along the first NOMINATE (economic) dimension, add anything meaningful.

When H.R. 14765 came up for a final vote it passed 259-157.Footnote 30 The vote margin suggests that some Republicans voted to recommit the bill and to pass the bill with the housing provisions included. Interested in the inconsistency of this position, we identified twenty-six Republican “switchers”—those who voted “yea” to recommit the bill and “yea” for the overall proposal. We assign a value of 1 to those Republican members who voted “yea” on the proposal to recommit H.R. 14765 with instructions to strip out the housing language, and “yea” on the final passage vote. Republicans who voted “yea-nay” are assigned a value of 0. Independent variables, as in the Table 2 analysis, include DW-NOMINATE scores, the percentage of Black voters in the member’s home district, the member’s percentage of the two-party vote in 1964, and whether a switcher’s home state already had enacted a strong fair housing law. The results of a linear probability model are presented in Table 3, in three columns (with various independent variables included).

Table 3. Linear Probability Model of House Republican Vote Switchers on Fair Housing, 89th Congress

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. The DV =1 if the Republican House member voted “yea” on the recommital motion and then “yea” on final passage, and 0 if “yea-nay.” See the 2x2 table for the vote distributions.

* p < .05

** p < .01

*** p < .001

Here we find that the second NOMINATE dimension is significant, indicating that House Republicans who were more liberal on racial issues were more likely to switch. Neither margin of victory in 1964 nor percent of Black voters in the district prove to be significant predictors of switching. Finally, and perhaps most interestingly, those Republicans from states with a strong fair housing law on the books were significantly (thirty-nine percentage points) more likely to have voted for both recommittal and final passage. This indicates that when the procedural vote failed (which was the party position), a number of Republicans from states with strong fair housing laws pivoted and followed constituent sentiment. This is consistent with political scientist David Mayhew’s (Reference Mayhew1974) argument focusing on the electoral connection between a member of Congress and her constituents. These Republican members recognized local support for fair housing laws and did not wish to motivate protests through their opposition to the overall bill.

Even as they were fighting to see H.R. 14765 passed in the House, administration officials and supportive Democrats recognized that its ultimate fate hinged on the disposition of Senate Republicans. If the conservative coalition in the Senate coalesced against the bill, they could filibuster it to death. In the days immediately after H.R. 14765 passed, Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D-MT) made clear that he hoped the Senate Judiciary Committee would act on the administration’s original bill (S. 3296). Yet he lamented the fact that the Judiciary Committee, run by James Eastland, was unlikely to bring something to the floor “at the end of two weeks, or two months, or two years” (Herbers Reference Herbers1966d). Mansfield pledged to give Eastland until at least September 6, 1966, but he also directed Senate Democrats to invoke Rule 14 which allowed Democrats to bypass the committee stage and place the House-passed bill directly on the Senate calendar.Footnote 31

All eyes now turned to Minority Leader Everett Dirksen (R-IL). As Mansfield told The New York Times, “The key to it is Dirksen. Without him we cannot get closure” (Herbers Reference Herbers1966e). Administration officials agreed, with one telling the Times, “Senator Dirksen stands at the pass, anything that he is not going to buy is just not going to be bought” (Franklin Reference Franklin1966c). President Johnson himself also testified to Dirksen’s influence: “I would hope that we could find some way to get his (Dirksen’s) support because I think whether it passes or fails will depend largely upon what the minority leader does about it” (United Press International 1966b). Dirksen was quick to dash the hopes of those who supported the House-passed bill. “I know nobody under the bright blue sky who can say anything to change my mind,” he declared in an interview (Semple Reference Semple1966). While Dirksen had worked with the Johnson administration to enact previous civil rights bills, he was not interested in brokering a deal this time around. He invoked a few rationales to justify his opposition: that the law infringed upon private property, that the law would reward purveyors of violence (i.e., the rioters), and that law was unconstitutional. But as Rigel Oliveri (Reference Oliveri and Squires2018) argues, “Ultimately Senator Dirksen’s resistance came down to that voiced by so many of the bill’s opponents: that the law simply could not—or at least should not—compel people of different races to live together” (p. 31).

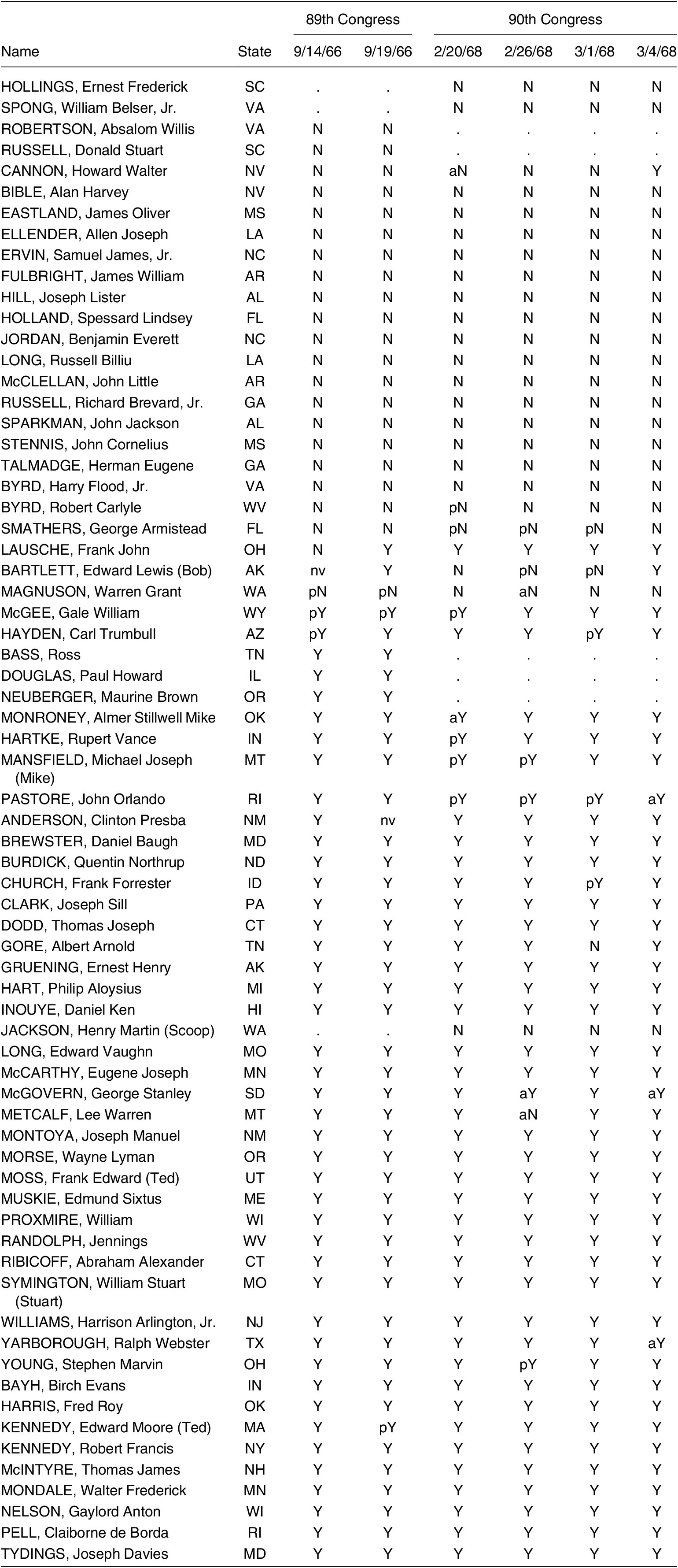

Dirksen’s vocal opposition successfully rallied Republicans against the bill. As Table 1 demonstrates, the conservative coalition worked to defeat cloture votes held on September 14 and September 19. In both cases, nearly double the number of Republicans voted with the southern Democrats to prevent debate on H.R. 14765 than voted for cloture. Following the failure of the second cloture motion, the civil rights bill of 1966 was dead.

The Johnson Administration misjudged the political environment in 1966. LBJ and some Democrats in Congress saw fair housing as just the next item on the broader civil rights agenda, which they believed could win public and elite support. They underestimated the level of opposition that would emerge, even among traditional allies of the civil rights movement. For example, with the midterm elections quickly approaching and the filibuster looming, an anonymous Midwestern Democrat noted: “It’s just not worth sacrificing my political hide [to back the bill]” (Hunter Reference Hunter1966). And one administration official acknowledged to The New York Times that “we are probably running the risk of losing some shaky seats in the House by making our guys walk the plank on a bill that we are not sure can get by the Senate” (Franklin Reference Franklin1966c). Recognizing that federal efforts to integrate northern neighborhoods would generate significant opposition, the liberal Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) in August 1966 called on President Johnson not to push Congress to take up fair housing legislation (Congress and the Nation 1969). These dire predictions proved true when, in the November elections, Republicans picked up three seats in the Senate and forty-seven in the House.

Pyrrhic Victory: Fair Housing Legislation in the 90th Congress

Lyndon Johnson was determined to enact fair housing protections despite Congress’s failure in 1966 and the significant losses the Democrats absorbed in the November midterms. Accordingly, he pushed his civil rights initiatives as the new (90th) Congress opened. In his January 10, 1967, State of Union message, Johnson asked Congress to legislate on the same civil rights matters that had formed the core of the 1966 bill: federal protection of civil rights workers, nondiscrimination in federal and state jury selection, nondiscrimination in employment, and fair housing (Johnson Reference Johnson1967). And on February 15, 1967, LBJ fleshed these proposals out, noting the similarities from the previous bill as well as a significant change in how the fair housing provisions would be enforced. This time around he sought to empower the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to hold hearings and issue cease-and-desist orders.Footnote 32

Yet the Administration’s omnibus civil rights legislation—H.R. 5700 and S. 1026—went nowhere in 1967. “A major reason for this,” as Graham (Reference Graham1990) explains, “was widespread resentment among the House members that they had been required to cast a vote on the bill’s most controversial provision, open housing, just prior to the fall [1966] election, but the Senate had not” (p. 267). The House expected the Senate to act first, and beyond some perfunctory hearings by the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights, nothing got done (CQ Almanac 1968b). No committee recommendations were made in either chamber.

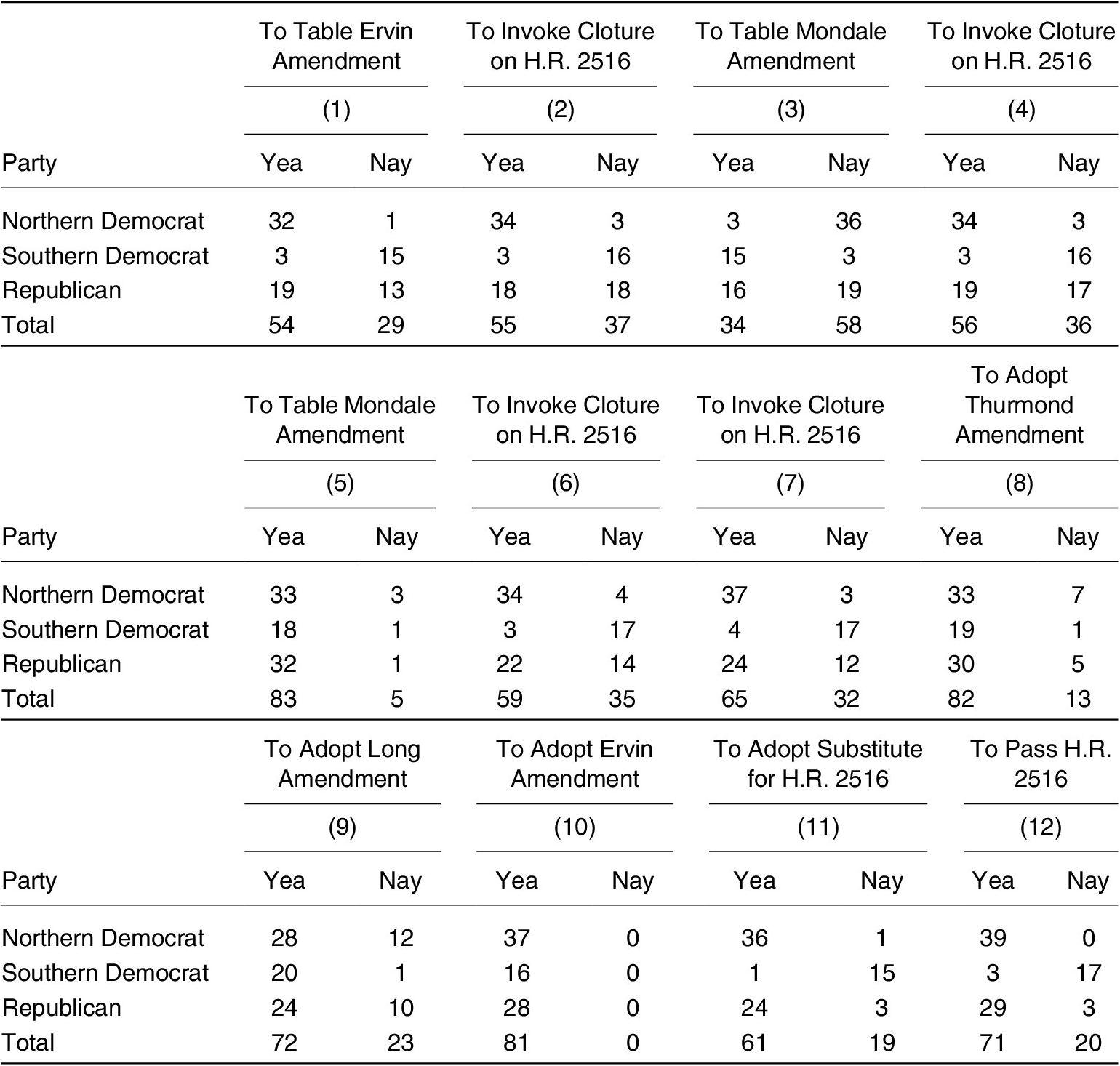

As a result, civil rights advocates in Congress broke LBJ’s omnibus legislation into separate bills and worked to pass each individually (CQ Almanac 1968c). This strategy produced a bit of success. A five-year extension of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, generally considered the least controversial of the president’s proposals, was enacted.Footnote 33 In December 1967, the Senate passed by voice vote a bill (S. 989) to prohibit discrimination in the selection of federal juries (CQ Almanac 1968d). The House took no action on the bill before the end of the first session, but passed it in February 1968.Footnote 34 On August 16, 1967, the House passed a bill (H.R. 2516) to protect civil rights workers (and others from having their civil rights threatened in a range of activities) against violence on a 327-93 vote (see Table 4),Footnote 35 but it got bogged down in the Senate; by the end of the first session, it had finally made out of the Senate Judiciary Committee by the narrowest of margins (an 8-7 vote).

Table 4. House Votes on Civil Rights Act of 1968, 90th Congress

Source: Congressional Record, 90th Congress, 1st Session (August 15, 1967): 22678; (August 16, 1967): 22778; 2nd Session (April 10, 1968): 9620; (April 10, 1968): 9621.

(1) To pass H. Res 856, providing an open rule with 3 hours of debate on H.R. 2516, a bill to establish penalties for interference with civil rights.

(2) To pass H.R. 2516, a bill to establish penalties for interference with civil rights. Interference with a person engaged in one of the eight activities protected under this bill must be racially motivated to incur the bill’s penalties.

(3) To order the previous question on H. Res. 1100, a resolution providing that immediately upon the adoption of this resolution, the bill (H.R. 2516) to prescribe penalties for certain acts of violence or intimidation, and for other purposes, with the Senate amendment thereto, be, and the same hereby is, taken from the speaker’s table, to the end that the Senate amendment be, and the same hereby is, agreed to. The bill is the civil rights bill, combining anti-riot legislation and prescribing penalties for interfering with any person in the performance of his civil rights. The Senate amendment referred to in H. Res. 1100 prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, religion, color, or nationality in the sale or rental of housing.

(4) To pass H. Res. 1100, a resolution providing that immediately on the adoption of this resolution, the bill (H.R. 2516) prescribing penalties for interfering with any person in the performance of his civil rights, and making certain anti-riot legislation, shall, together with a Senate amendment thereto, providing penalties for discrimination in the sale or rent of housing, be taken from the speaker’s table, to the end that said amendment is agreed to.

Lawmakers also sought to crack down on the violence associated with urban unrest across the United States. Between April and early September 1967, more than 100 cities experienced some form of disorder (U.S. News Staff 1967), resulting in eighty-three killed, more than 3200 injured, over 8700 arrests, and property damages estimated at $524.8 million.Footnote 36 In response, William Cramer (R-FL) once again sponsored a bill (H.R. 421) to establish federal penalties for those accused of “inciting riots.” Here Cramer simply reintroduced as a standalone bill the amendment that he had offered to the Civil Rights Act of 1966. Cramer’s bill passed 348-70.Footnote 37 By 1967, it was easy for Congress to pass legislation cracking down on angry residents of American cities. No progress, however, was made on open housing.

As the first session of the 90th Congress ended, Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield made H.R. 2516 (the civil rights protection bill) the pending business when the chamber reconvened on January 15, 1968. Mansfield’s decision prevented a subsequent motion to bring the bill up for floor consideration (CQ Almanac 1969b). Moreover, as Graham (Reference Graham1990) notes, “once the bill was the Senate’s order of business, proposed amendments could not be procedurally filibustered” (p. 270). While the Senate began debate on H.R. 2516, President Johnson again sent a message to Congress, imploring the body to pass the remaining elements of his civil rights agenda. On the issue of fair housing, LBJ stated: “A fair housing law is not a cure-all for the Nation’s urban problems. But ending discrimination in the sale or rental of housing is essential for social justice and social progress” (CQ Almanac 1969c).

In the Senate, Sam Ervin, Jr. (D-NC) introduced a substitute amendment, retaining the language of the protection coverage of H.R. 2516 for federal activities only (and thus eliminating protections for state and local activities) and deleting the phrase “because of his race, color, religion, or national origin” as a provision of the law. On February 6, the Senate voted to table Ervin’s weakening amendment, 54-29.Footnote 38 (For this and all Senate votes on the Civil Rights Act of 1968, see Table 5). But while Senate liberals and conservatives fought about the appropriate language of H.R. 2516 (and whether it should be based on the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment or the Commerce Clause), a movement was under way to greatly expand the scope of the bill. More specifically, Clarence M. Mitchell, Jr., the chief lobbyist for the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, “set out to make the bill a vehicle for an open-housing amendment” (CQ Almanac 1969d). In late December 1967, Mitchell worked with Senators Phillip Hart (D-MI), Joseph Tydings (D-MD), and Walter Mondale (D-MN) to draft a bill that would be cosponsored by Mondale and Edward Brooke (R-MA). While Mansfield and Attorney General Ramsey Clark resisted such an amendment, as they feared it would jeopardize passage of H.R. 2516 (and then the civil rights coalition would get nothing), Mitchell slowly built support for his initiative. By early February, the pro-civil rights senators agreed to make a go of it.

Table 5. Senate Votes on Civil Rights Act of 1968, 90th Congress

Source: Congressional Record, 90th Congress, 2nd Session (February 6, 1968): 2269-70; (February 20, 1968): 3427; (February 21, 1968): 3807; (February 26, 1968): 4064-65.

Source: Congressional Record, 90th Congress, 2nd Session (February 28, 1968): 17916; (March 1, 1968): 4845; (March 4, 1968): 4960; (March 5, 1968): 5214.

Source: Congressional Record, 90th Congress, 2nd Session (March 6, 1968): 5539; (March 8, 1968): 5838; (March 8, 1968): 5839; (March 11, 1968): 5992.

(1) To table Ervin Amendment no. 505 to H.R. 2516, a bill to provide penalties for racially motivated interference with civil rights. The Ervin Amendment would restrict the bill’s coverage to rights extended under the interstate commerce clause of the constitution and programs involving federal funds and would make it unlawful to interfere with the performance of these rights, no matter whether interference was racially motivated or not.

(2) To close debate (cloture) on H.R. 2516, a bill to prescribe penalties for racially motivated interference with civil rights.

(3) To table Sen. Mondale’s amendment no. 524 to H.R. 2516, which would add a new Title to provide for implementing a policy of open housing.

(4) To close debate (cloture) on H.R. 2516.

(5) To table modified Mondale Amendment no. 524 to H.R. 2516, adding a new Title to provide for implementing a policy of open housing.

(6) To close debate on modified Dirksen amendment no. 554 to H.R. 2516, consisting of Title I on interference with federally protected activities, and Title II on fair housing.

(7) To close debate (cloture) on modified Dirksen Amendment no. 554 to H.R. 2516 consisting of Title I on interference with federally protected activities, and Titles II and III on fair housing.

(8) To amend H.R. 2516, by modifying the anti-riot provisions of the bill so that it be unlawful to use interstate facilities with intent to incite a riot. The amendment was substantially modified by requiring proof of intent to riot rather than presumption of intent as evidenced by certain activities.

(9) To amend H.R. 2516, by adopting proposition 2 of chapter on civil disorders of modified Long (La.) Amendment no. 517, which attaches penalties for teaching use of weapons and for the transport and manufacture of certain weapons for civil disorder.

(10) To amend H.R. 2516 by adding six new titles on the rights of American Indians.

(11) To adopt a committee amendment, in the nature of a substitute for H.R. 2516. The committee amendment had previously been modified by the adoption of the Dirksen amendment in the nature of a substitute for the committee amendment.

(12) To pass H.R. 2516, a bill to prohibit discrimination in sale or rental of housing, and to prohibit racially motivated interference with a person exercising his civil rights, and for other purposes.

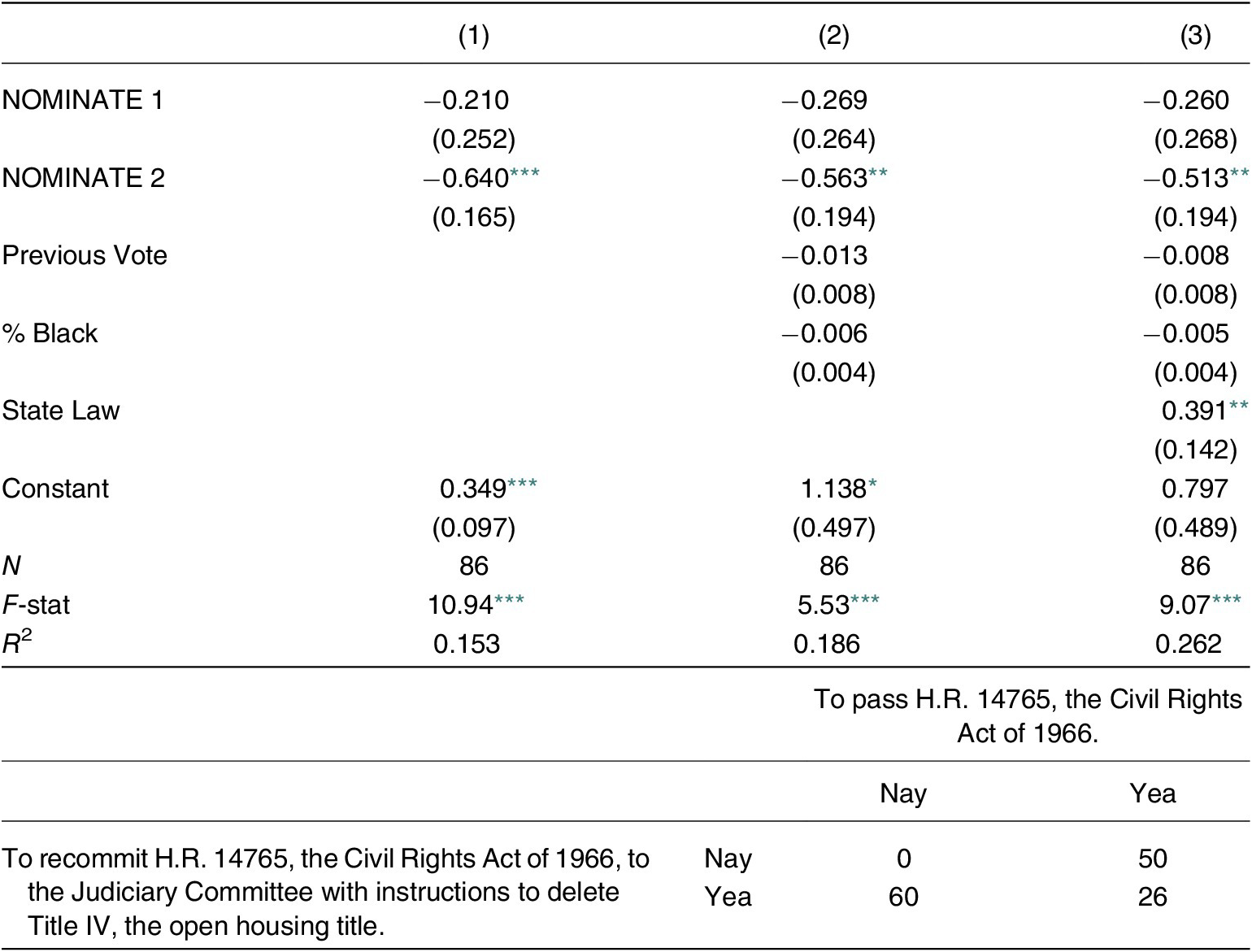

After Ervin’s amendment was tabled, Mondale offered an open housing amendment (co-sponsored by Brooke). The “Mondale Amendment” (as it became known) differed from the Administration’s open housing bill (S. 1358) by providing an exception for “Mrs. Murphy housing,” dwellings of up to four separate living units in which the owner maintained a residence. Once the provisions of the Mondale Amendment were fully enacted, it would cover around ninety-one percent of the nation’s housing (CQ Almanac 1969b). Not surprisingly, conservatives, led by southern Democrats, objected to the proposal. Speaking for this group, Ervin stated that the amendment sought “to bring about equality by robbing all Americans of their basic right of private property.” It allowed, he claimed, “one Cabinet official sitting on the banks of the Potomac” the authority to decide how a homeowner may dispense with her property (CQ Almanac 1969b). Here again we see the position of those opposing fair housing laws: “private” discrimination carried out in the “market” is acceptable.

As expected, Ervin and his southern Democratic colleagues sought to filibuster the amendment on its merits. A cloture vote was attempted on February 20, and it failed, 55-27.Footnote 39 While not garnering the necessary two-thirds majority of members present and voting, it was closer than many expected: a shift of seven votes would have produced success. Northern and southern Democrats voted in opposite directions, while Republicans were evenly split (18-18). The following day, Mansfield and Minority Leader Everett Dirksen filed a tabling motion on the Mondale Amendment, which failed, 34-58.Footnote 40 Northern and southern Democrats again voted in opposite directions, while a majority of Republicans voted against tabling (16-19). After the failed tabling motion, Dirksen announced to the Mondale group that he was ready to work with them on a compromise open-housing amendment (CQ Almanac 1969b).

Another cloture vote was held on February 26 after the failed motion to table the Mondale Amendment. It failed by six votes, 56-36.Footnote 41 Northern and southern Democrats voted exactly as they did on February 20; this time, a majority of Republicans (19-17) voted in favor of cloture, as Norris Cotton (R-NH) changed his vote. On February 27, Dirksen met with Mansfield and announced his support for a new open-housing amendment, built around compromise language from Jacob Javits (R-NY). The compromise would exempt all owners of free-standing homes for sale or rental, if they sold or rented themselves rather than through a real-estate broker/agent. Javits’ exemption proposed to reduce the law’s coverage of the nation’s housing from ninety-one percent to around eighty percent.

Along with a significant decrease in coverage, Javits’ compromise also eliminated language allowing the Chairman of the Department of Housing and Urban Development to enforce the law. HUD was allowed to investigate potential cases of discrimination, but all enforcement actions would need to be taken by the Department of Justice.Footnote 42 According to Irving Bernstein (Reference Bernstein1996), this change guaranteed that the enforcement mechanism included in the bill was “fatally defective” because the DOJ lacked the “stomach for enforcement” (p. 499).

Yet Mondale and his supporters were pleased with Dirsken’s efforts. On February 28, Mondale paved the way for the “Dirksen Amendment” by moving to table his own proposal. This motion passed, 83-5.Footnote 43 The following day, March 1, a third cloture vote was attempted. This one—on the Dirksen compromise—failed by four votes, 59-35.Footnote 44 Northern and southern Democrats continued their opposition to one another, and larger majority of Republicans now voted in support (22-14), as three more Republicans switched their votes: Dirksen, Howard Baker (TN), and Len Jordan (ID). Dirksen was exhausted from the negotiation with his caucus members, so other party leaders, including Richard Nixon, stepped into the fray (Hulsey Reference Hulsey2000). On the next (fourth) cloture vote, on March 4, the necessary two-thirds, 65-32 was achieved.Footnote 45 Two additional Republicans—Frank Carlson (KS) and Jack Miller (IA)—switched to supporting cloture. Two Democrats—Howard Cannon (NV) and Albert Gore (TN)—also switched to supporting cloture. (A number of other senators switched from a paired vote to an active vote, or vice versa.)Footnote 46

As we have already noted, Dirksen had been an active and vocal opponent of fair housing in the 89th Congress, and he used his influence to keep a majority of Republicans voting to oppose cloture, thus dooming the legislation. He began the 90th Congress with the same negative position. Why did he switch? Dirksen himself offered a number of explanations: he suggested he changed his mind on the notion that fair housing was a state, rather than a federal, problem; he suggested that doing nothing on fair housing may lead to more riots; he mentioned the need that veterans returning from Vietnam would have for open housing; and he noted the absence of fair housing laws in many states. It was also clear that his hold on the leadership of his caucus was more tenuous than in the past. While the forty-seven-seat pickup for House Republicans had made the chamber more conservative, the three-seat pickup for Senate Republicans had in fact made the chamber more liberal (Graham Reference Graham1990). According to Byron C. Hulsey (Reference Hulsey2000), “What moved Dirksen to support fair housing in 1968 was an accurate sense that he had lost control of his caucus” (p. 255).

With cloture invoked, the Senate moved to end consideration of H.R. 2516. A host of amendments—more than eighty in all—had been submitted, and more than forty votes were taken. Some small adjustments were made to the open housing title but the “Dirksen Compromise” largely held. Importantly, a couple of additional titles were added. One was an anti-riot amendment, introduced by arch segregationist Strom Thurmond (R-SC) and co-sponsored by Frank Lausche (D-OH). Modeled after the Cramer Amendment in the House, the Thurmond Amendment made it a federal offense to travel across states or use interstate facilities (mail, telephone, radio, and television) for purposes of participating in or inciting a “riot.” Thurmond’s amendment achieved widespread support, passing 82-13.Footnote 47

A second amendment, offered by Russell Long (D-LA), pursued a similar goal. It laid out criminal penalties for manufacturing, transporting, or training another person in the use of a firearm or explosive device with the intent that it would be used across states in a civil disorder. The Long Amendment also passed easily, 72-23.Footnote 48 Lastly, Sam Ervin (D-NC) proposed an amendment to protect American Indians from tribal rules that attempted to deprive them of their constitutional rights. The Ervin Amendment passed unanimously (81-0).Footnote 49

The Senate then proceeded to vote on the Dirksen Amendment (as amended) as a substitute for H.R. 2516. This passed, 61-19, with large majorities of northern Democrats and Republicans voting against all but one southern Democrat.Footnote 50 Finally, the Senate passed H.R. 2516 (as modified) by a similarly large margin, 71-20, with the voting coalitions largely repeating themselves.Footnote 51

H.R. 2516 (as modified by the Senate) was now sent to the House, where it received a mixed response.Footnote 52 Liberals wanted the chamber to accept the Senate-amended bill without change, while southern Democrats and many Republicans wanted the bill sent to conference. The conservative argument was that the early version of H.R. 2516 was considerably narrower in content (containing only the civil rights protections provision), and that the House deserved to consider the additional provisions adopted in the Senate. Doing so would necessitate the appointment of a conference committee. In effect, the battle was between the Senate-amended bill and a stripped-down version of H.R. 2516, as many believed House conferees (should a committee be appointed) would work to eliminate important elements of the bill, such as the open-housing provision.

While supporters of the modified H.R. 2516, like President Johnson, sought quick action, the House Rules Committee met on March 19 and voted 8-7 to delay action until April 9. In the interim, LBJ kept the pressure on, and various Republican leaders like Richard Nixon and Governor Nelson Rockefeller (NY) also urged the House (and Republicans specifically) to back the Senate amendments. On April 4, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, which created additional pressure on the House to act (Brown Reference Brown2018). Finally, on April 9, the Rules Committee met, and a motion to send the bill to conference was defeated, 7-8.Footnote 53 The swing vote was John Anderson (R-IL), who had previously voted with the majority to delay consideration. The Rules Committee then voted 9-6 to report H. Res. 1110—agreeing to the Senate-amended H.R. 2516—to the floor.Footnote 54

The showdown vote came the next day, March 10, which involved ordering the previous question on H. Res. 1100. Ray Madden (D-IN), sponsor of H. Res. 1110, urged that the chamber order the previous question. “If the previous question is voted down,” he said, “this legislation is almost certain to be sent back to the other body for probably certain delay, filibustering, and stagnation. This procedure no doubt will mean no civil rights, housing, or antiriot bill in the 90th Congress.”Footnote 55 Minority Leader Gerald Ford (R-MI) instead advocated that the bill be sent to conference (and thus that the previous question be voted down). “If we take the path of expediency, we will live to regret it. I say to you in my judgment we should follow time-tested procedures of parliamentary procedure,” he argued, “because they are primarily in the best interests of our minority groups, and also in the best interests of our citizens.”Footnote 56 A host of other members, on both sides, made similar arguments.

As the time for debate was about to expire, H. Allen Smith (R-CA), the final speaker, made the following announcement:

Mr. Speaker, I yield myself my remaining 30 second to refresh the minds of the Members that the gentleman from Indiana [Mr. Madden] will move the previous question. I will request a yea and a nay vote. A “yea” vote for the previous question will send this bill to the White House. A “nay” vote, if carried, will vote down the previous question. I will offer an amendment to send the bill to conference if a “nay” vote prevails.Footnote 57

The House then voted on ordering the previous question on H. Res. 1100, and it passed, 229-195 (see Table 4).Footnote 58 A large majority of northern Democrats opposed a large majority of southern Democrats. Republicans split, but a significant majority (106 of 183) joined the majority of southern Democrats in voting against the compromise. Enough Republicans (77) joined with nearly all northern Democrats, however, to successfully order the previous question.

In a set of linear probability models, we examine the Republican votes in more detail, (similar to our 1966 analysis in Table 2). Our goal, as before, is to examine the ideological, racial, electoral, and state-level factors influencing Republicans votes. The dependent value takes a value of 1 for those Republicans who voted “yea” on the previous-question motion on H. Res. 1100 (to take up the Senate-amended bill), and 0 if “nay.” Independent variables include first- and second-dimension DW-NOMINATE scores, the percentage of Black voters in the member’s home district, the member’s percentage of the two-party vote in 1966, and whether a switcher’s home state already had enacted a strong fair housing law.Footnote 59 Results appear in Table 6. We find that both economics and civil rights do explain this vote, as both NOMINATE dimensions are negative and significant.Footnote 60 This indicates that House Republicans who were more liberal on both economic and racial issues—those Republicans closer to the preferences of northern Democrats —were more likely to vote in support of ordering the previous question on H. Res. 1100. As in the 1966 analysis, none of the other variables add anything meaningful.

Table 6. Linear Probability Model of House Republican Votes on Ordering the Previous Question on H. Res. 1100, 90th Congress

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. The DV =1 if the Republican member voted “yea” on the previous−question motion on H. Res. 1100 (to take up the Senate-amended bill), and 0 if “nay.”

* p < .05

** p < .01

*** p < .001

The House then immediately moved to the vote on the resolution itself, and this passed, 250-172.Footnote 61 A set of Republicans (22 of 106) switched from “nay” to “yea,” and as a result a majority of Republicans voted with nearly all northern Democrats against nearly all southern Democrats. Thus, H.R. 2516, as amended by the Senate, was passed by the House and sent to President Johnson for his signature. Johnson signed the bill into law the following day (April 11), and the Civil Rights Act of 1968 became Public Law 90-284.

Why did those twenty-two House Republicans switch on fair housing, by voting against ordering the previous question on H. Res. 1100 (and thus against the Senate bill) and then voting for the Senate bill when the previous question was ordered? To examine this, we conduct a similar analysis to the one in Table 3, by exploring the ideological, electoral, racial (district), and legal (state) determinants of the likelihood of a “switch.” The dependent value is equal to 1 if the Republican member voted “nay” on the previous-question motion and then “yea” on final passage, and 0 if he voted “nay-nay.”

Linear probability model results appear in Table 7. Just as in the 1966 analysis, the second NOMINATE dimension is significant. House Republicans who were more liberal on the second dimension—that is, more liberal on civil rights—were more likely to switch. The inclusion of a member’s previous share of the two-party vote and the percent Black in the district add a bit, as previous vote share is significant, with Republicans who won their prior election by a slimmer margin were more likely to switch. Finally, when the incidence of a strong state fair housing law is included in the model, this proves to be highly significant (and washes out the previous two-party vote result). A House Republican who represented a state with a strong fair housing law already in place was almost thirty-five percentage points more likely to switch. Like in 1966, when the procedural vote failed (the party position), a number of Republicans from states with strong fair housing laws pivoted and followed constituent sentiment. Here again we see Republican members behaving in a way that is consistent with the “electoral connection.”

Table 7. Linear Probability Model of House Republican Vote Switchers on Fair Housing, 90th Congress

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. The DV =1 if the Republican member voted “nay” on the previous−question motion and then “yea” on final passage, and 0 if “nay−nay.” See the 2x2 table for the vote distributions.

* p < .05

** p < .01

*** p < .001

Thus, Congress in 1968 did what it failed to do two years prior: it passed a new civil rights law with a formal prohibition on housing discrimination. The bill that passed won support from a bipartisan coalition because, with near universal opposition from the southern wing of the Democratic Party, that was the only option available to its supporters. The compromises required to get the bill through both the House and Senate, however, turned the fair housing provision into an “empty gesture” (Carter Reference Carter2009, p. 238). Meeting the demands of northern White voters led lawmakers to exempt millions of homes from the bill’s legal protections. And after making these exemptions, lawmakers gutted the original enforcement mechanism. In response, as Bernstein (Reference Bernstein1996) contends, “the real estate industry—builders, realtors, appraisers, insurance companies, banks, mortgage lenders, sellers, and buyers—systematically defied and undermined the statute with virtual impunity” (p. 499). Moreover, overwhelming bipartisan majorities voted to include “anti-riot” provisions in the bill, which were understood to be tools for smearing and then punishing those involved with the broader civil rights movement. While the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act were hailed as landmark laws signaling progress for Black citizens, the bill Congress passed in 1968 did not have the same effect. Instead, it shed light on an important new political reality: White opinion was turning against efforts to end segregation in the Northeast and Midwest. For those who believed in the value of prohibiting forms of discrimination like housing segregation, the 1968 Civil Rights Act previewed many disappointments that lay in store over the coming decades.

Conclusion

For President Johnson and his allies in Congress, ending discrimination in the sale and rental of housing was supposed to be the next stage of the civil rights agenda. Having pushed through Congress two landmark civil rights laws in 1964 and 1965, they could be forgiven for believing that further progress was achievable. The epidemic of urban rioting driven by the unbearable living conditions in northern and western urban centers seemed, to them, a demonstration of the need for additional federal action. Testifying before Congress in August 1966, Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach gave voice to this position when he attributed the terrible civil unrest to “disease and despair, joblessness and helplessness, rat-infested housing and long-impacted cynicism” (Sloyan Reference Sloyan1966). Putting an end to the ostensibly private practices leading to segregated housing was seen by civil rights activists at the time as one possible way to counteract the social and economic forces producing unequal life outcomes between Black and White Americans. This bill would not meet their expectations.

Passing and then enforcing the fair housing provision of the 1968 Civil Rights Act proved difficult because support from northern and midwestern White voters, a prerequisite for all civil rights initiatives, was very difficult to win. As we have described, the administration’s effort to enact fair housing language in 1966 first required persuading ostensible allies to go along by significantly weakening their proposal. Once weakened, it passed in the House but failed to win enough support from Republican moderates in the Senate to overcome a filibuster. The administration renewed the fight two years later, and a similar dynamic took hold, as the original proposal won supporters only after it was amended to exempt millions of homes and to weaken its enforcement mechanism. This time around, however, Everett Dirksen’s decision to support the proposal, pushed along by more Republicans in the Senate being amenable to the legislation, ensured it would be included in the 1968 Civil Rights Act.

In this way, the battle to see fair housing legislation enacted reaffirms a pattern that has long influenced congressional action on civil rights policy: legislative proposals to end particular forms of discrimination run contrary to the preferences of northern White voters and, as a consequence, fail to achieve their ostensible aims. Almost one century earlier, a very similar dynamic played out as Congress considered legislation authored by Senator Charles Sumner (R-MA). Sumner played an integral role in crafting laws designed to protect the rights of the previously enslaved who had been freed by the Civil War. Late in his life, Sumner continued working to end “social” segregation in businesses and other “personal” aspects of society both North and South.Footnote 62 Sumner took aim at the effects of segregation in terms that would apply just as well in 1968. Discussing segregated schools, for example, he argued that they could “not fail to have a depressing effect on the mind of colored children, fostering the idea in them and others that they are not as good as other children” (quoted in Wyatt-Brown Reference Wyatt-Brown1965, pp. 763–764). The bill Sumner first proposed in 1872 therefore aimed to ensure that any “legal institution, anything created or regulated by law … must be opened equally to all without distinction of color.”Footnote 63 We could easily apply Sumner’s thinking to the sale or rental of homes in the United States.

When Sumner first introduced his civil rights bill it met immediate opposition from more “moderate” Republicans. They believed it was unconstitutional to try to legislate “social” equality. The bill went nowhere until 1875 when, after Sumner’s death, the GOP passed legislation in “honor” of Sumner that ran contrary to all of the goals he had pursued. Most importantly, it explicitly endorsed the principle of “separate but equal.” William Gillette (Reference Gillette1982) describes the bill as representative of “the bankruptcy of legislative sentimentalism and reconstruction rhetoric, which demeaned noble ideals and undercut vital interests” (p. 279). In short, the Civil Rights Act of 1875 demonstrated to the country that the civil rights coalition responsible for landmark achievements—like the 1866 Civil Rights Act and the Fourteenth Amendment—could not put together the votes required to address forms of segregation that diminished the lives and livelihoods of Black Americans living outside the South. From this moment until the beginning of the second civil rights Era, all the momentum was behind those who sought to block new civil rights laws or to reverse those which were already on the books.

The political process that led to enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 played out in very similar ways. Once again, support from White voters outside the South was required to get an important civil rights law passed. Those voters were hesitant to endorse provisions that would impact their social and economic lives. Their representatives in Congress behaved accordingly by ensuring that the legislation Congress did pass could not possibly counteract the problem it was supposed to address. What happened in 1968 also previews what was to come as the Great Society gave way to the Nixon years: once federal civil rights policies started to bear directly on the lives of northerners, they became much harder to pass and implement. These battles in the 1970s, on issues like busing and school integration, split the parties and sometimes split the Democrats by region (Delmont Reference Delmont2016). Republicans had joined with northern Democrats on civil rights legislation through 1965, while working to weaken said legislation for their constituents, wherever they could. Beginning in 1966, the GOP would move to the right on civil rights legislation and quickly establish racial conservatism as the party’s congressional position.

Acknowledgments

Jeffery A. Jenkins thanks the Lusk Center for Real Estate at the University of Southern California for a research award to help support the research conducted for this article.

Appendix

Table A1. Democratic Votes to Invoke Cloture on Civil Rights Acts of 1966 and 1968

Note: Y=Yea, N=Nay, pY=paired Yea, pN=paired Nay, aY=announced Yea, aN=announced Nay, nv=not voting, .=not a member.

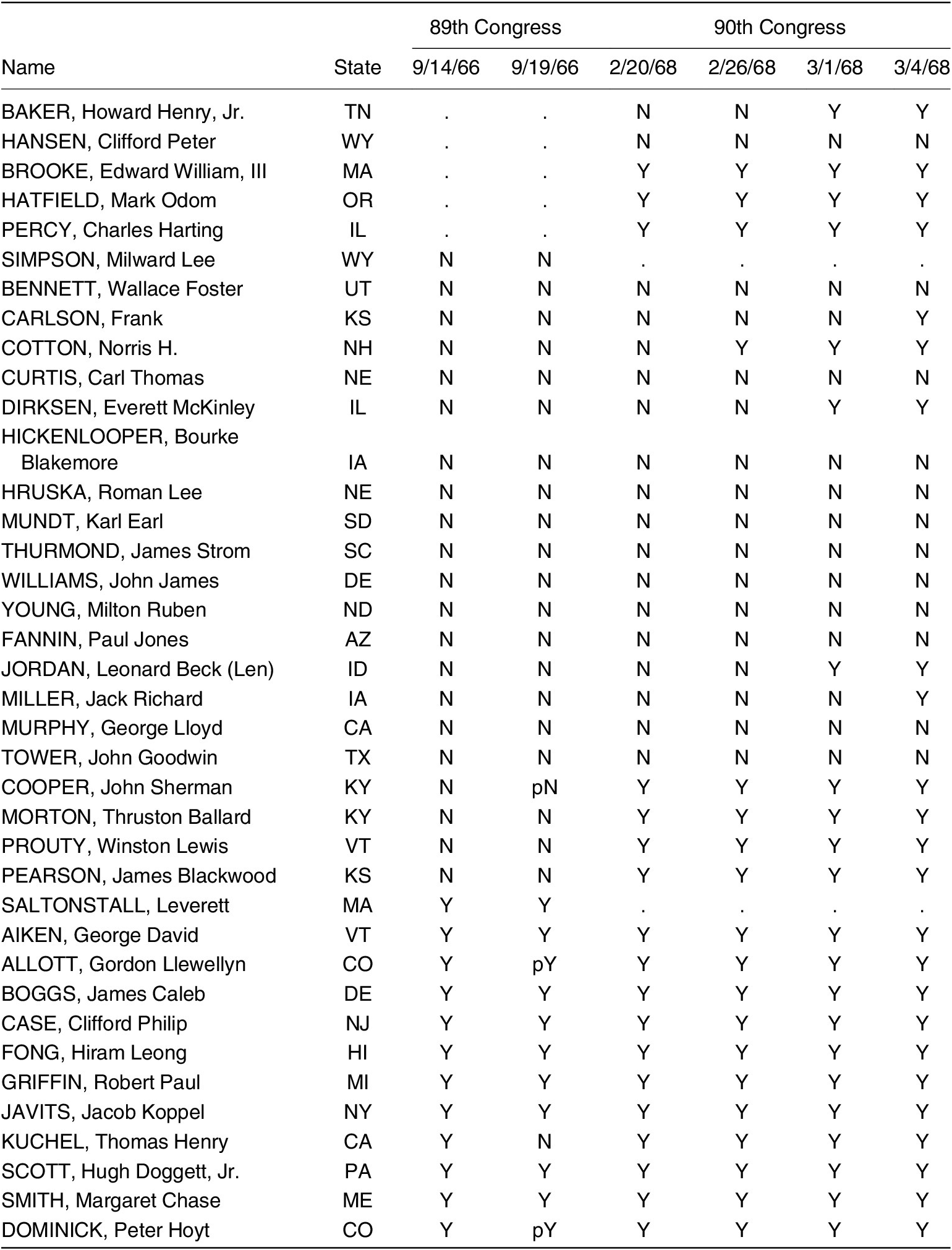

Table A2. Republican Votes to Invoke Cloture on Civil Rights Acts of 1966 and 1968

Note: Y=Yea, N=Nay, pY=paired Yea, pN=paired Nay, aY=announced Yea, aN=announced Nay, nv=not voting,.=not a member.