INTRODUCTION

Despite considerable scholarship about Black people in Latin America, the study of the Black middle class, which has become an established field in the United States, has not yet been fully articulated in the study of Latin American societies. It is important to study the Black middle class because of its potential role in Black politics in the region. Yet it is also important not to assume that such Black middle-class politics actually exist. To that end, we use a convenience survey and qualitative interviews with twenty-two Black professionals in Cali, Colombia to explore the following questions: Does the intersection of being Black and being middle class cohere into a group identity? If so, does it translate into a Black political consciousness? And if not, what are the obstacles?

Cali, Colombia, is a city of over two million residents. Over 25% of the population identify as Afro-Colombian (Duarte et al., Reference Mayorga, Natalia, Alvarez Rivadulla and Rodríguez2013),Footnote 1 and between 6% and 11% of Black Caleños have a college degree (Urrea Giraldo and Botero-Arias, Reference Urrea Giraldo and Botero-Arias2010; Viáfara et al., Reference López, Augusto, Moreno and Aguiar2011).Footnote 2 Yet, as Rogers Brubaker and Frederick Cooper (Reference Brubaker and Cooper2000) argue, identification “does not presuppose that such identifying (even by powerful agents, such as the state) will necessarily result in the internal sameness, the distinctiveness, the bounded group-ness that political entrepreneurs may seek to achieve” (p. 14). In this article, we follow Brubaker’s (Reference Brubaker2002) charge to analyze identity and groupness as possible outcomes of social processes, interactions, and explicit racial projects (Omi and Winant, Reference Omi and Winant2014), rather than as essential qualities of some demographic denominated as “the Black middle class.” In particular, we inquire about the identity and groupness of Black professionals in Cali in order to better understand the character of and potential for something that might be called Black middle-class politics.

We find that while respondents individually identify with a Black middle-class label, they do not experience it as a group with symbolic bonds of attachment or by acting in a coordinated or mutually cognizant manner. It is a category without shape or coherence; it is amorphous. We use the adjective “amorphous” rather than “divided” or “fragmented” so as not to make a normative claim that the Black middle class should be unified. Instead, we explore what such amorphism might mean for Black politics.

BLACK POLITICS IN LATIN AMERICA

While this study is rooted in one city in one Latin American country—Cali, Colombia—we aim to be in conversation with the broader literature on Black politics across the Americas in order to recognize how “previously disparate black communities [are] in affinity and dialogical networks of discourses and activities” (Hesse and Hooker, Reference Hesse and Hooker2017, p. 444). The diversity of Black Latin American politics encompasses multiculturalism, struggles for collective land rights, corporatist inclusion into civil society, affirmative action, and insurgent and anti-hegemonic disruption (Bailey Reference Bailey2009; Hooker and Tillery, Reference Hooker and Tillery2016; Lao-Montes Reference Lao-Montes2009; Mitchell-Walthour Reference Mitchell-Walthour2018; Paschel Reference Paschel2016; Paschel and Sawyer, Reference Paschel and Sawyer2008; Rahier Reference Rahier2012). Many of the leaders of these movements are involved in Black transnational networks organized around a “similar history of slavery in the Americas as well as similar conditions of marginalization, discrimination, and inequality today” (Paschel and Sawyer, Reference Paschel and Sawyer2008, p. 198). Other movements are deeply rooted in place and the local cultures born of those places, which can pose problems for the development of a group consciousness, especially for those living in cities who have little connection to ancestral lands, languages, practices, or cosmologies (Hooker Reference Hooker2005).

Contemporary Black struggles in Colombia have been characterized by a strong connection to place and culture. The Constitution of 1991 explicitly recognized and established rights to land ownership among Black communities on the Pacific Coast of Colombia. Law 70 (“The Law of Black Communities”) of 1993 added rights to representation in national politics, an Afro-Colombian curriculum, and promises for social and economic development (Paschel Reference Paschel2010). During this period, Black activists in Colombia moved from making “claims based on the right to equality to making them on the basis of the right to difference” (Paschel Reference Paschel2010, p. 754). The concept of “difference” in Colombia is highly spatialized, growing out of the experience and efforts of activists in the Colombian Pacific region who promoted it. Moreover, the rural territorialization of Black politics in Colombia has created challenges for translating the political gains of the 1990s to the emerging Black middle class in cities.

Black Upward Mobility and Politics

As the population of Black college graduates grows across Latin America, a Black middle-class demographic is emerging (Benavides et al., Reference Benavides, León, Galindo and Herring2019; Viáfara López and Banguera Obregón, Reference López, Augusto and Obregón2019; World Bank 2018). Several studies have explored Black middle-class experiences of discrimination across national contexts (da Silva and Reis, Reference da Silva and Reis2011; Lamont et al., Reference Lamont, Silva, Welburn, Guetzkow, Mizrachi, Herzog and Reis2016; Twine Reference Twine1998). Experiences of racial discrimination in social and labor market settings could strengthen a Black identity and generate greater racial self-awareness or greater commitment to political activism (Mitchell-Walthour 2016). Alternatively, such incidents could be minimized as rare or interpreted as resulting from the behavior of Black people themselves (Viveros Vigoya and Gil Hernández, Reference Viveros Vigoya and Hernández2010), which would have the opposite effect.

For a Black middle class to exist, individuals must continue to identify as Black once they have reached the middle class. Previous assumptions about “whitening”—the idea that upward mobility increases the chances of identifying as White—have recently been questioned and complicated (Golash-Boza Reference Golash-Boza2010; Osuji Reference Osuji2019), but not wholly discarded (Paredes Reference Paredes2017; Viveros Vigoya Reference Viveros Vigoya2015). For the Colombian case, Edward Telles and Tianna Paschel (Reference Telles and Paschel2014) find that more education does not lead to whitening, but rather to mestizoizing. Controlling for skin tone, more education increases a person’s likelihood of self-identifying as Mestizo, which in Colombia refers to a lighter-skinned mixed person with considerable European ancestry (also see Hooker’s (Reference Hooker2008) category of Afro-mestizos). While there may not be whitening, there is still some departure from Black categorization among upwardly mobile Colombians. For example, Mara Viveros Vigoya and Franklin Gil Hernández (Reference Viveros Vigoya and Hernández2010) found that some younger generation, middle-class Black Colombians eschewed a Black self-identification by emphasizing instead their sameness with their non-Black peers. The authors note: “We might describe the identities that they construct for themselves as ‘postracial’ in a country that at the same time experiences great difficulty in overcoming, in practice, the ideology of mestizaje that constituted its national identity” (p. 124, authors’ translation; also see Wade Reference Wade1993).

The contemporary Colombian Black middle class has been explored through two major research projects directed by Mara Viveros Vigoya at the National University of Colombia in Bogotá.Footnote 3 The present study builds where those studies left off, especially upon the work of Viveros Vigoya and Gil Hernández (Reference Viveros Vigoya and Hernández2010), who interviewed sixty Black professionals in Cali and Bogotá about their mobility trajectories. They found that “in the Colombian case, the upward mobility of Black people has been an individual process, in contrast with the group upward mobility that the Black population in the U.S. experienced” (p. 125). They argued further that the focus on individual effort, investment, and success “limits any suggestion that puts the middle classes at the vanguard, per se, of offering answers to the problems of social marginality of Colombia’s Black population” (p. 127-128; also see Viveros-Vigoya Reference Viveros-Vigoya2012). Although politics was not their main topic of inquiry, the authors were not sanguine about the development of a Black middle-class politics. We replicate their findings and probe deeper to ask why.

Viveros Vigoya and Gil Hernández (Reference Viveros Vigoya and Hernández2010) make an explicit comparison to the upward mobility of Black people in the United States as one model of how Black middle-class identity might manifest. Decades of legal segregation and discrimination reinforced by violence and terror in the U.S. set the foundations for a Black professional class that was deeply embedded in Black communities for the sake of their livelihoods and protection (Drake and Cayton, Reference Drake and Cayton2015; Du Bois Reference Du Bois1899). This resulted in a sense of “linked fate” with other Black people (Dawson Reference Dawson1995). The Black middle class also attempted to set itself apart in its own social clubs, churches, universities, economic institutions, and neighborhoods, which facilitated shared experiences and worldviews and coordinated social and political action—that is, a strong sense of groupness (Frazier Reference Frazier1957; Hine Reference Hine2003; Landry Reference Landry1987; Pattillo Reference Pattillo2013). The U.S. Black middle class constitutes just one possible trajectory, however. While it animates the comparative question about the positionality of middle-class Black people in Latin America (in this case, specifically in Cali), we purposefully avoid a normative stance on how the Colombian Black middle class should develop. Instead, in the Discussion section, we consider what different trajectories might mean for Black politics in Colombia.

Despite a robust literature on the Black middle class in politics in the United States, the question of the class status of Black activists and the political outlook of middle-class Black people in Latin America has merited only passing mention in most research to date. In their comparative look at Black politics in the region, Tianna S. Paschel and Mark Q. Sawyer (Reference Paschel and Sawyer2008) write, “While activists are frequently middle class, the mass of the population struggles for everyday survival” (p. 201). France Winddance Twine (Reference Twine1998) echoes this observation for Brazil, writing “with a few exceptions…the struggle against racism has involved a minority of Afro-Brazilian professionals” (p. 2; also see Dixon Reference Dixon2016, p. 73). Few studies focus on the middle-class positionality of Black leaders, and even fewer study the politics of middle-class Black people unaffiliated with Black social movements. Gladys L. Mitchell-Walthour (Reference Mitchell-Walthour2018) offers the most explicit and comprehensive study of the relationship between race, class, and politics, focusing on Brazil. She finds that highly educated Black Brazilians are more likely than Black Brazilians with less education to see their fate as linked with other Black people. We focus on this sense of groupness or solidarity within the Black middle class and across class within the Black community, which are important building blocks for political consciousness and action (Hooker Reference Hooker2009).

Our contribution to the literature is to investigate the simultaneity of a Black and middle-class group identity and political consciousness outside of the networks of political activists in order to capture everyday experiences of being Black and middle class in Colombia. By “group identity” we mean two interrelated processes: First that the individual evinces a “self-understanding” that accepts and deploys both a Black (Afrocolombiano, Afrodescendiente, Negro, Afro, etc.) racial label, and a middle-class label, as well as what those labels connote in social settings; and, second, that the person feels a symbolic (if not literal) attachment to other members of the group based on “physical, psychological, sociopolitical, and cultural elements of life” (McClain et al., Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Walton and Watts2009, p. 474). It is the “sentiment that members of a social category belong together, even if there is little or no interaction among them” (Osuji Reference Osuji2019, p. 5). A sense of attachment represents a relatively weak indicator of groupness, while “Black political consciousness” adds action. It is an “in-group identification politicized by a set of ideological beliefs about one’s group’s social standing, as well as a view that collective action is the best means by which the group can improve its status and realize its interests” (McClain et al., Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Walton and Watts2009, p. 476, emphasis in original). This is the strong test of a group, one that requires coordinated or mutually cognizant activities. While group consciousness does not require agreement on specific strategies or policies, it rests upon a shared desire for and commitment to a collective effort towards improving the lives of Black people (Pattillo Reference Pattillo2007).

The groupness of a category is not given, but comes only as the result of effort from both group insiders and outsiders (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2002). A constructivist approach to groupness focuses on the work of insiders who create and deploy historical, cultural, and material resources and references to bring the group into being and constantly reinforce its salience. A more structural approach recognizes how groups are named, circumscribed, and excluded or included through legal, economic, ideological, discursive, and physical mechanisms (Omi and Winant, Reference Omi and Winant2014). Our method in this research is best suited for following the constructivist approach, as we explore internal processes of group-making, or their absence. Moreover, we focus on the intersection of two potential identities at the same time: Blackness and middle-classness. Do they cohere? Is Blackness inflected by middle-classness for our interviewees, and vice-versa?

DATA AND METHODS

Cali is the capital city of Valle del Cauca, a department that also encompasses several cities and towns on the Pacific Coast, which is the region with the country’s greatest Black representation.Footnote 4 For example, 88.5% of the residents of the port city of Buenaventura are Black. Cali has been a migration destination for Black people from the Pacific region and other rural towns for decades (Barbary et al., Reference Barbary, Ramírez and Urrea2002). Cali represents better educational and labor market opportunities, and thus the chance for upward mobility. As a result, the city is an appropriate locale to ask whether Black middle-class subjectivities are forged, or not (Barbary and Urrea, Reference Barbary and Urrea2004).

The interview sample consists of twenty-two Black middle-class professionals, all but two residing in the city of Cali. We were referred to one interviewee in Cartagena and one in Bogotá because of their unique employment positions. We deferred to respondents’ modes of racial self-identification. All interviewees used the terms Negro, Afrodescendiente, or Afrocolombiano to self-identify, except for one person who self-identified as Mulato. Regarding class status, we followed Fernando Urrea Giraldo and Waldorf F. Botero-Arias (Reference Urrea Giraldo and Botero-Arias2010) in defining middle-class as having a college degree.

Our strategy was to identify people based on their profession and to cover the following occupational fields: higher education, primary/secondary education, law, banking/finance, the arts, NGOs, real estate, industry (sugar, mining, etc.), health, and social services. We identified initial interviewees through participants in a gathering of Black professionals in the early 2000s; an online service for connecting professionals with clients; the alumni network of a local university; and personal contacts. Then we asked for referrals to expand our sample. This strategy yielded a diverse sample by age, gender, profession, social class background, and educational experiences.

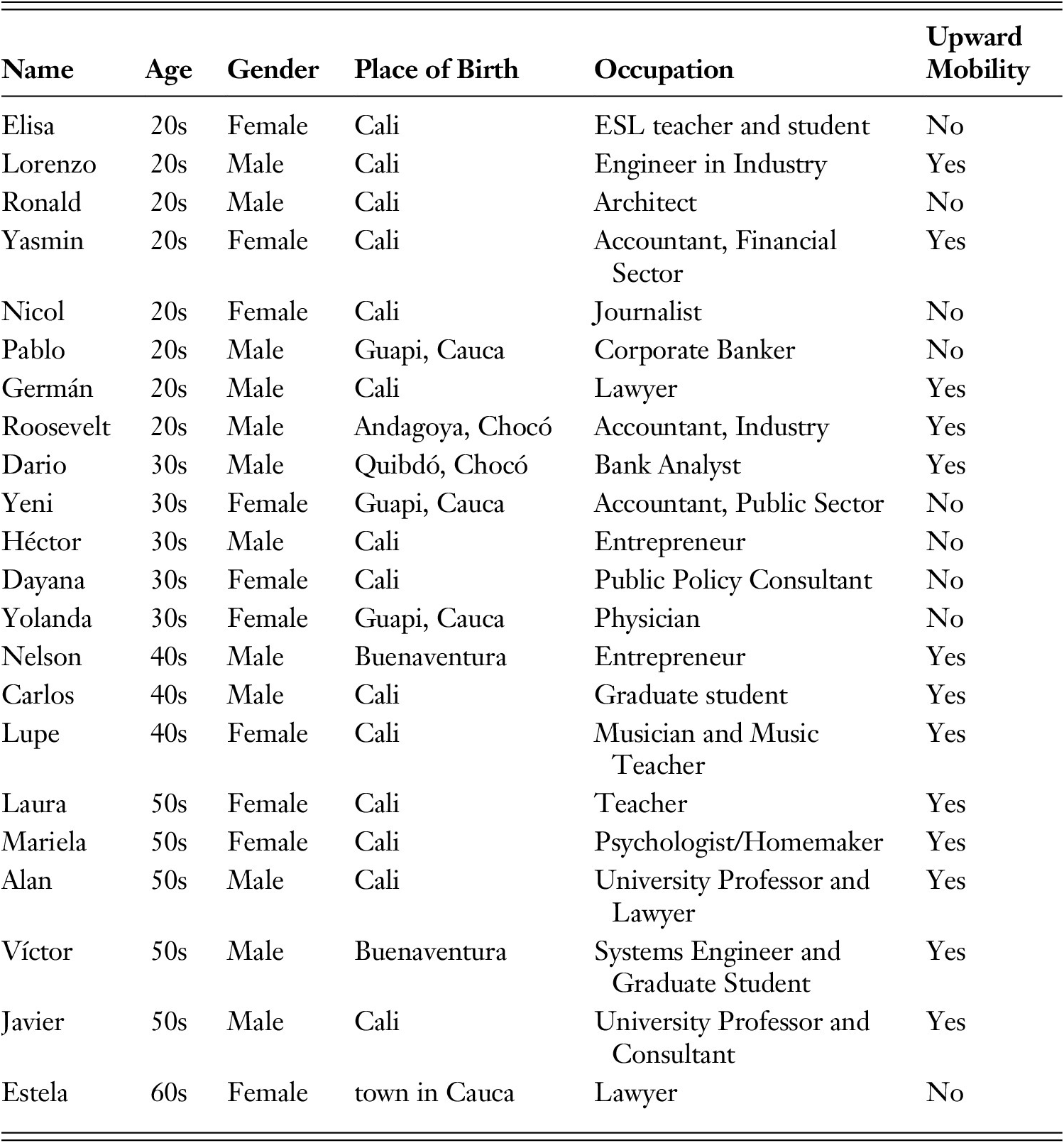

Table 1 describes our sample. Interviewees’ ages ranged from their twenties to sixties. Ten interviewees were women and twelve were men. Fourteen were born in Cali—most with parents or grandparents who migrated to the city—and eight were born outside of the city. Thirteen were cases of upward mobility, defined as neither parent having a college degree. Interviewees came from a wide variety of fields. The youngest was finishing a second undergraduate degree in foreign languages; the oldest was an accomplished lawyer working in the public sector.

Table 1. Interview Sample

Interviews were semi-structured and asked respondents to elaborate on five themes: their childhood and adolescence; their primary/secondary schooling; their university years; their work lives; and their reflections on the concept of the Black middle class. The interviewer used the explicit phrase la clase media Negra (“the Black middle class”) to describe the study. We asked if the respondent thought such a thing existed in Cali, and if they were a part of it, or not, and why. We also asked about Black social, political, or organizational events or activities in Cali, and about the role of the Black middle class in the Black community. The interviews ranged in length from one to two hours. All interviews were conducted in and transcribed into Spanish. Quotations in the article represent our translations into English. We occasionally share the Spanish original in order to signal the variety of terms that people used to refer to Black people, or other important concepts. All names are pseudonyms.Footnote 5

We used NVIVO qualitative data analysis software for coding. We developed a codebook of fifty-seven topics that were derived both deductively from the theoretical interest in Black middle-class consciousness, and inductively after listening for unexpected themes. We arrived at our findings through an iterative process of writing reflections after the interviews, coding, writing memos, and reviewing code output. Our argument is supported by much more interview data than we have space to present here. Thus, our strategy for writing was to choose exemplary quotes and to ensure that each interviewee’s voice was represented at least once in the article.

We also conducted a short survey with a convenience sample of thirty-two respondents who were current or former participants in a university seminar on Afro-diasporic Studies. The survey sample was split roughly evenly between current undergraduates and college graduates. Just over three-fourths were women. All but four self-identified using one of the many terms for Black. The survey gathered opinions on the frequency of discrimination and on the role and behavior of the Black middle class. A final open-ended question asked if there was anything else the respondent wanted to share about the topic. We report findings and quotes from this survey throughout the article.

Our collaboration developed organically. Mary Pattillo proposed the project under the auspices of a Fulbright/ICETEX fellowship, which funded the authors’ stay in Cali to conduct interviews. Rosa Emilia Bermúdez Rico hosted Pattillo at the Universidad del Valle, helped with the design of the interview guide, and facilitated and participated in interviews. Ana María Mosquera Guevara was a research subject and then became a research assistant for the project, helping with survey development, cleaning of interview transcripts, identifying codes and themes, and the translation of Colombian Spanish. All three of us identify as Black women. We see this collaboration as a way to check both the U.S.-based author’s outsider information gaps and biases and the Colombian-based authors’ insider interpretations and blind spots. In many ways, this paper is a dialogue between three Black middle-class women scholars on questions that are not only academic, but also personal.

FINDINGS

Black Middle-Class Category

In the final part of the interview, we asked respondents if they thought that a Black middle-class category existed in Cali, or in Colombia, and if they fit within it. Everyone we asked answered in the affirmative to both questions. Yasmin was in her twenties and worked as an accountant for an elite private firm. She was medium-brown skinned with straightened hair past her shoulders. She offered a very straightforward answer to the question:

Yes, because physically it’s clear that I am of the Black race [raza negra]. I accept that without any problem. Actually, I don’t have any complex about it. And I belong to the middle class. I wasn’t born into a family of millionaires. We are a family that’s had to fight for things and work hard. Yes, I consider myself Black middle class.

The category of Black in Colombia is very much connected to physical appearance, particularly brown or dark skin, curly or kinky hair, and facial features more common in people of African descent. Yasmin’s mother was White (Blanca) and her father was Black. She came out “physically” Black, as she put it. Still, being Black is a choice for all but people with the darkest skin tone and the kinkiest hair. That’s why Yasmin clarified that “she accepts [it] without any problem,” because embracing Blackness is a problem for some people who look like Yasmin and have her background. She could choose not to self-identify as such—and use, instead, Mestiza (mixed), or Morena (brown), or Mulata (mixed)—even if other people might read her as Black (Wade Reference Wade1993).

At the same time, being light-skinned does not rule out being Black. Yolanda, a doctor in her thirties, mentioned that her light skin meant she sometimes had to work to express a Black identity. Born in the predominately Black coastal town of Guapi, Yolanda said that her whole family—of which she was the lightest skinned—had always identified as Black. “Obviously, I wear it with pride,” she said about being Black. But, she continued, “in my case there is something very particular, and it’s that by me being light-skinned, I’m not defined [as Black]. So, I always try to emphasize it more than someone who has darker skin.” For Yolanda, being Black consisted partially of physical appearance—it was her kinky hair, she said, that made it clear she was Black—partially of effort, and partially of culture. “No one can take away my last name. No one can take away my cultural heritage,” she said about having a Black-identified surname and about her roots in the Pacific Coast. Like Yasmin, Yolanda was, personally, “unproblematically” Black.

Nicol, a journalist in her late twenties, offered more information about being Black and middle class.

Yes, I think I’m a part of Cali’s Black middle class because it’s a middle class that did not start in the middle. It began as emergent… Now, it’s not the “average” Colombian middle class. It’s a Black middle class, which is the special thing. With one being marked, once again, in an ethnic framework, it’s a bit more difficult to emerge or rise in a society like Colombia. Nonetheless, even with all of that, it’s been possible to have a kind of upward mobility, so to speak. Today, thank God, we live in a house in a neighborhood of Cali that is stratum-5, but we weren’t raised in a stratum-5 neighborhood. We grew up in a difficult neighborhood, a low-income Cali neighborhood with difficulties. And little by little, over time, we’ve been overcoming those difficulties by being at the precise edge of Cali’s emerging Black middle class.

We sat in the living room of the house that Nicol mentioned in her comments. The furniture was new with a Victorian-era flair. We sat across from each other, a glass table separating us. Her small dog with a pink bow sat on her lap. The neighborhood clearly corresponded with the stratum-5 (estrato 5) designation, a public classification that translates to upper-middle class (DANE 2020). Aesthetically, this meant a quiet and clean street of single-family homes freshly painted in bright colors with decorative gates and prominent garages. Living in an upper-middle-class neighborhood was evidence of upper-middle-class status. But, as Nicol explained, the Black middle class was still in process, still emergent. Most of the people we interviewed (59%) were the first in their families to graduate from college (see Table 1). Nicol’s mother got her degree while raising her children, so even though Nicol was not a case of upward mobility, she nonetheless knew firsthand the newness of the Black middle class.

Most of our respondents emphasized the importance of higher education in defining and creating the Colombian Black middle class. Elisa, the youngest of our interviewees, had finished one degree in International Business and was working on a second in Foreign Languages. She talked about the role that education played in her family. The lessons began with her paternal grandfather, Elisa narrated, as we sat in her family’s spacious old home with an indoor swimming pool and a colorful portrait of Nelson Mandela hanging prominently in the living room.

My grandfather strongly insisted that his children study. He would tell them, “You all are Black [Negros] and as Black people in this country, the only way to be successful, to triumph in life, is studying. If you study, you will see that there won’t be a way for them to discriminate against you, because you will be the best at all that you do.

This is a very classic mobility story. Work hard, study hard, and you will be judged for your accomplishments, not for your physical appearance. It was a message that all our interviewees took to heart. The fact that we defined middle class as having a college degree no doubt contributed to the importance that our respondents placed on education. Yet it came up spontaneously and without inquiry in the interviews. And not just as empty words, but often connected to some family story or example that proved the point. The richness of the attestations illustrates that getting an education is a core part of a Black middle-class self-understanding.

The existence of a Black middle-class identity in Cali seemed self-evident to most of the people we interviewed. It combined a Black self-identification based on physical appearance, personal conviction, and/or culture, with a middle-class status connected to education, occupation, neighborhood, and behaviors. Yet the existence of a category and an individual identity is not sufficient to constitute a group. Next, we turn to the equally broadly held view that the Black middle class is not at all unified, and then we explore why.

…But Not a Group

“Estamos distanciados,” Roosevelt explained. We are separated. Roosevelt, twenty-nine, worked as an accounting director in an industrial firm. He rose quickly at his company and was better compensated with each promotion. We talked in a Starbucks near his house. He elaborated on his sense that the Black middle class was both separated from each other and from less advantaged Black people.

There are movements that I’ve read about, they are organized movements that have certain Black people [Afros] at the national level that are recognized because they are a part of the top political sphere, or because they are a part of the entertainment world, or because they have high corporate positions. But I feel like they don’t connect all of the people that they could connect. Like I said, we are separated.

Roosevelt highlighted the risk of studying groupness based on the actions of ethnic entrepreneurs (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2002). From his perspective, there were movements and their leaders, and then everyone else. A study of movement leaders might conclude that the Black middle class is a unified force but focusing on racial and class identity among the uninvolved tells another story. The most basic component of groupness is a sense of attachment to others in the group, the majority of whom are perfect strangers but nonetheless (historically, symbolically, culturally, politically) related. The phrase “we are separated” is clear evidence that such attachment does not exist, and we heard it repeatedly.

Víctor and Laura—a couple in their fifties, systems engineer and teacher, respectively, and both with roots in Black towns outside of Cali—voiced a similar sentiment as Roosevelt, using different words. We talked in their home in a gated community in South Cali. They couldn’t agree if there were other Black residents in their residential complex or not. “The thing is, sometimes people don’t accept (no se asume)” being Black, Laura said. Both Víctor and Laura were dark skinned and accepted being Black without a problem. When we asked if they thought the Black middle class was united in any way, Laura answered easily, “No, I don’t think so. Each person lives their life… There isn’t unity. That’s how I see it.” Víctor was in full agreement, repeating: “No, the people aren’t united at all.” This inspired Laura to continue:

Even more, it seems to me that once people become a professional, they alienate themselves. It seems like they forget those who haven’t left, who still haven’t become professionals. It seems that in that way we lack being more united… There isn’t like a team, a group that says, “What can we do for Black communities?”

Whereas Roosevelt characterized the Black middle class as separated, Laura saw it as alienated (or isolated) and as alienating themselves (“la gente se aliena”). Alienation meant there were few groups working on issues affecting Black people and an unwillingness to connect with Black people still struggling to get ahead.

The isolation was also spatial. Héctor, an entrepreneur in his mid-thirties, described how upward mobility often meant outward mobility. “Sometimes, when a Black person has some money the first thing that they do is leave from where Black people are and go to surround themselves with White people.” Héctor was referring as much to the migration from Black towns to multi-racial Cali as to the move from Blacker to Whiter neighborhoods within Cali. This was a story that we heard several times in people’s life histories. For Héctor, this was another indication that the Black middle class was distanciada.

Yet it was not just distance, but also animus that characterized the social relations of the Black middle class. Mariela, a homemaker and volunteer in her fifties with a degree in psychology, told us “Sometimes, you could think that the people who most throw darts at you are people of the same race.” Nicol put it another way. “If there were unity, there wouldn’t be a Black person that screws another Black person, or the Black person that creates space for only himself. Those things wouldn’t exist because there was unity.” Nicol argued that the Black middle class “lacked the unity necessary to make itself visible. Because we all know that [the Black middle class] exists, but there isn’t a clear feature that identifies it.” This lack of clarity, lack of form, lack of coherence is what we characterize as amorphism. Our respondents were unanimous in their opinion that the Black middle class was not a group. It did not act collectively, nor was such collectivism seen as an important goal.

The survey data equally supported the finding of Black middle class amorphism. We asked how much people agreed with the following statement: “People in the Black middle class in Colombia show a commitment to the Black community.” Only 25% agreed, 41% disagreed, and 34% were neutral on the issue. In the comments to the survey two people mentioned that the Black middle class was more committed to the project of blanqueamiento, or whitening (Viveros Vigoya Reference Viveros Vigoya2015). “I feel that the Black middle class in Colombia tends to work more on whitening themselves, uprooting from their origins,” one person wrote. Another echoed, “Social mobility for the Black population in the Colombian stratification system is very associated with whitening in ways and manners and with mixing with White people.” Black middle-class individuals were neither connected to each other nor to more disadvantaged Black people, except for within their own close families, and then sometimes only tenuously. The Black middle class did not constitute a group. In the following sections we elaborate why.

The Absence of Collective Cultural Referents

The basis for Black identification and identity is probably the question most widely addressed in the literature on Blackness in Latin America. Scholars have approached this topic from the perspective of race-making in censuses (Loveman Reference Loveman2014; Nobles Reference Nobles2000), inter- and intra-racial familial relationships (Hordge-Freeman Reference Hordge-Freeman2015; Osuji Reference Osuji2019), sociodemographic determinants (Telles Reference Telles2014), migration (Joseph Reference Joseph2015; Roth Reference Roth2012), and law and politics (Hanchard Reference Hanchard1998; Hernández Reference Hernández2012; Mitchell-Walfour 2018; Paschel Reference Paschel2016), among other topics. The takeaway from decades of this research is that Blackness is complicated, place and time specific, individually fluid, and always in flux. Part of the reason for the varying levels of groupness across contexts is the association of Blackness with so many negative stereotypes. While the emergence of a Black middle-class demographic might create the conditions for the development of a positive set of associations around which to organize and cohere, we find that this is not the case in Cali. Instead, our respondents knew well what it meant to be stereotypically Black and did not want to be associated with that stigmatized identity. Instead, the cultural references about which they could be proud were deeply regional, often from their or their extended family’s rural hometowns, and thus not capable of unifying Black people from numerous distinct places, or people born and raised in Cali.

“In Colombia, Black people [las personas Negras] are marked as bad for the simple fact of being Black. We are criticized and generally every bad thing that happens is Black people’s fault [culpa de los Afro].” This was a comment in the open response section of our survey. Yasmin offered a similar reflection: “Many Black people feel ashamed of being Black and that shame makes them isolate themselves a bit from society and not fight as much for their rights.” Our interviewees easily elaborated on all the bad things that Black people stereotypically represented in Colombia. Desorganizados, desordenados, bullosos, cabeza gacha, hablando duro, acento marcado, muy alegres, quieren sacar doble, bailan salsa, super rumberos, colores extravagantes, les gusta el trago, pobre, alborotados, ruidosos, expresivos, espontáneos. That is, Black Colombians are supposedly loud, happy, always dancing and drinking, dirty, disorganized, spontaneous, and often have a strong regional accent. Rarely did we ask directly about stereotypes about Black people. Instead, as the interviewees described their own behaviors, likes, and dislikes, they compared or contrasted themselves to these ideas about Black people.

Lorenzo, a recent college graduate working as an engineer in a small industrial firm, noticed that his White co-workers held their tongues just before saying something derogatory about Black people. Lorenzo’s father was Mestizo and his mother was Negra and he self-identified as Negro. He was light-skinned with curly hair and said that “it always happens to me that, like, I am not recognized on either of the sides.” Because of his appearance, White people often let down their guards around him about racial issues. Lorenzo explained:

This even happened with my boss, or my boss’s brother, I don’t remember. It so happens that in order to get to our [factory] we have to pass through Puerto Tejada. It’s an all-Black town [un pueblo completamente Afro]. That town has the distinction of, and I’m saying this, you pass through it and you see all the Black stereotypes, the dirt, the noise. At the entrance to the town there are two stoplights and it’s like they don’t even exist. The disorder. Also, the danger, because there is also that stigma. I remember that we were driving, going from the office to the factory, like, he was starting to complain about the behavior, like, he was going to start to get to, like, attribute that behavior to the Black community, to put a specific name to that behavior, to those stereotypes, and he, like, stopped…. He didn’t get to any derogatory terms or anything. But, yes, when he got to that part, he used more caution in his use of words, so to say.

Lorenzo’s story repeats some of the common stereotypes about Black people and shows that Black people themselves observe those stereotypical behaviors. “Lo digo yo,” Lorenzo said when he described what he saw at the entrance to Puerto Tejada. Lorenzo did not convey any sense of shame when riding through the town, but he did name and recognize the stereotypes as being a part of a general stigma. The negative public identity of Blackness makes it a difficult category around which to create symbolic group attachment.

The people we interviewed reported experiencing little racial discrimination in their lives, except for the ubiquity of these negative stereotypes.Footnote 6 A structuralist perspective on racial categories would see such pervasive stigma as a catalyst for group salience. Indeed, negative tropes about Blackness and Black people are salient in Colombian media and culture and contribute to processes of marginalization and exclusion (Gil Hernández Reference Gil Hernández2010; Valle Reference Valle2019; Wade Reference Wade1993). However, these imaginaries are not how Black people constitute themselves. Instead, the weight of the negative associations that accompanied Blackness made it a difficult identity around which to cohere.

Performing middle-class Blackness meant eschewing stereotypically Black behaviors in order to avoid stigma. For example, when Yeni moved to Cali from Guapi with her sister Yolanda and their family, she had a rough time in school. “When I arrived, I had a very strong accent [from the coast] and I spoke really loud. The teacher was always correcting me…and the students at first made fun of the way I talked.” As she experienced more bullying from peers and disapproval from the teacher, Yeni started to change. “I started to speak softer, to use other types of words,” she said. Yeni became more Caleña and less Guapireña. Her own individual Black identity remained strong, but she disconnected it from behavioral qualities associated with Black people as a group.

Nelson, an entrepreneur and promoter of Black cultural events, was in his forties, and was born in Buenaventura on the Pacific Coast. He stated that his family moved to Cali to leave the underdevelopment and hard life behind. But in the process, they also shunned parts of their practices and traditions.

They didn’t talk like Black people. They didn’t want to hear anything about fish. “I don’t like seafood,” [they would say] because it signified in their psyche that that was the definition of being Black. “Chontaduro? What is that? I don’t know it.” They came fleeing, not just from poverty but also from being Black, because Black and poor were synonymous.

Language and food items common on the coast—fish, seafood, the chontaduro fruit—were part of the representations of Blackness that travelled with migrants to Cali, even as they tried to escape them.

Efforts to distance, isolate, or alienate sometimes extended to one’s family. Nelson continued: “I’ve noticed that when you live in stratum-5, 6, you don’t want to invite your poor relatives to your party so that your neighbors don’t see them.” Nelson was critical of this practice and jibed that “the day you die, [those family members] are the people that will go to your funeral.” Nevertheless, the possibility that a Black family member would come and be loud, get drunk, or wear bright colors was enough to chip away at the family bond. If the stigma of Blackness eroded bonds within families, it did even more damage to the possibility of Black (middle-class) groupness.

Many of our younger interviewees, however, had a romantic and nostalgic view of the majority-Black towns where their families had roots. When we asked Dayana, a woman in her thirties, where she was from, she answered:

For me always, when someone asks me that question, I like to say where my family comes from. Because the fact is that I was born in Cali. But the fact that I was born in Cali was a practice of my mother who lived in Timbiquí, Cauca, [on] the Caucan Pacific Coast. My mother was, she’s now deceased, Timbiquireña, and my father’s family is from Guapi, a nearby town…. My mother would come and have her babies in Cali, and then take us back there.

Despite having been born and mostly raised in Cali, Dayana still felt a connection to her parents’ hometowns. She visited the Pacific Coast regularly as an adult, especially for her work as a policy and development consultant. She considered the region as part of her personal history. When she went to visit the port city of Buenaventura, she described how she “travelled all of the rivers of Buenaventura, a marvelous experience of connecting with my roots.”

Carlos, a graduate student, answered in a very similar manner as Dayana to the question of where he was from. “Actually, I always say I am a Barbacoano born in Cali.” Barbacoas is a majority-Black town of roughly 40,000 people in the southernmost Colombian department of Nariño. When Carlos was younger, his parents regularly took him back to visit family in Barbacoas. Carlos remembered fondly and vividly a visit when he was ten years old:

I arrived there to Barbacoas, specifically an area that they call Chimbuza, Lake Chimbuza. There I learned the greater part of that relationship, of what it is to live by the river, what it is to not have electricity, what it is to not have toys… I learned that there is a way to celebrate, you know, in that place, like the vigils to the saints, which has to do with protection. It was there that I also saw my grandfather and grandmother sing and play instruments… And I said, look, cool!

Carlos’s reference to living by the river, which he later expressed as living the river (vivir el río), elucidates the centrality of the water—rivers, streams, lakes, sea—for many of the people we spoke to with roots in the Pacific (Oslender Reference Oslender2016). There were also references to the distinct rituals, foods, musical rhythms, dances, and slang that filled those visits. These were the positive cultural materials that were at the center of the social movement demands for the right to Black difference, autonomy, ethno-education, and land titling (Paschel Reference Paschel2010). In the struggle for recognition, these practices were presented as the proof that Black people were indeed a group, connected by behaviors and beliefs that even the second generation were exposed to on these trips home.

Our interviews made it clear, however, that these ingredients of a supposedly shared Blackness could not be untied from their geographic specificity, and the groupness only extended as far as the town limits. As a respondent wrote on the survey “Black people [in Colombia] have a strong sense of territory” (see Escobar Reference Escobar2008; Offen Reference Offen2003; Paschel Reference Paschel2016; Wade Reference Wade1993). Ronald, a young architect, remembered such territorial attachments and how they created factions at his private university. He described that “at times it’s people from Buenaventura, or from Chocó, and amongst themselves they put together their posse. When they go to lunch it’s only them and they don’t let anyone join their space.” This was also Yasmin’s experience in college. “They got together because they came from Chocó, from Buenaventura… because they knew each other better, not because they were forming a group dedicated to Afrocolombians.”Footnote 7 The students from those coastal cities constituted a Black “other” for Yasmin, who was born and raised in Cali, not one that worked towards or contributed to a sense of pan-regional Blackness on campus.

The idea that there can be multiple “others” amongst the category of Black people was echoed in the comments of Lupe, a musician in her forties. Even though both of her parents were from the Pacific Coast, she had not gone there much, and her description illustrated her distance from that kind of Blackness. When she went to Quibdó, the capital of Chocó, as an adult to play a concert, it was like any other outsider visiting somewhere new.

What really stands out about these Black towns is the joy. It’s impressive how they sing songs. The same in Buenaventura. With [our musical group] we would go there a lot to parties in Buenaventura and the energy of the people and the joy is impressive. They are very beloved in that sense.

Lupe’s father was from Chocó and her husband was from Buenaventura, yet she experienced both places as representing a different kind of Blackness than what she knew in Cali. When she took her oldest children to Buenaventura, she said “obviously they could see how they talk there, how they dress, what the environment is like.” It was a lesson in difference. Like Carlos, Lupe had positive reactions on her trips, but like Ronald those trips also made it evident that they performed a certain kind of Blackness that was not generalizable, and not something that Lupe saw as representing her.

The people we interviewed roundly rejected the bad stereotypes about Black people. Some embraced the cultural practices of the Pacific, but these were too narrow and excluded people born in Cali who could not reproduce the coast in the city. There was no clear sense of what it meant to be a Black Caleña/o—or, even more broadly, a Black Colombian—to replace or add to the nostalgia of life on the coast. There was nothing firm to latch onto, no contents around which to form a group. Blackness, and by extension Black middle-classness, was an amorphous category without shape or referents. Of course, group consciousness need not be based on any shared cultural practices or worldviews. A shared narrative around African roots, slavery in the Americas, experiences of discrimination, a set of heroes, or a commitment to service could be the ethos or anchor that binds a group (e.g., Hirsch and Jack, Reference Hirsch and Jack2012). Likewise, group consciousness could be forged in resistance to, or strategic reclamation and deployment of, negative stereotypes (Cohen Reference Cohen2004; Harris-Perry Reference Harris-Perry2011; Kelley Reference Kelley1993). Creating a group narrative is the work of actors and organizations who devise and execute specific racial projects. The people we interviewed, however, did not do this work as individuals and saw a distinct void of catalysts in the way of Black organizations.

Weak Black Organizational Infrastructure

Over 80% of the survey respondents agreed with the statement that “members of the Black middle class should support the Afrocolombian community and especially those who are less privileged.” The disconnect, however, was in the conversion of wishes and expectations into organized action to do that work. As reported previously, only 25% of our survey respondents agreed that middle-class Black people showed a commitment to the Black community. Lupe, the musician, voiced this dilemma:

On the issue of Black communities [las Negritudes], sometimes I feel powerless because sometimes in the street I see young girls of my race and I see them with their skimpy clothes…or that live in the Aguablanca district, and I know that things are difficult there and that sometimes they face really hard situations. That breaks my heart. What can I do for them?

Lupe did not have an answer to her question about what to do. Instead, she turned to her work as a music teacher, offering music lessons to young people in her own neighborhood. Yet unlike the Aguablanca area that Lupe referenced, which has a high percentage of Black residents, her neighborhood was “very mixed…without a large group of Black people clustered in any sector.” Lupe’s question about helping the young Black girls she saw might represent a latent Black middle-class consciousness, but it was not sufficient to motivate her to act, nor was it being cultivated by existing Black organizations.

In 2020, there were 1782 registered Black organizations in Colombia, both active and inactive (DACN 2020). Registering as a Black organization offers rights to be consulted over land and community development issues, and to be able to sponsor students for scholarships and affirmative action slots. There were ninety-one such registered organizations in Cali, but their capacity was questionable. For example, Yaneth Consuelo Angulo Angulo (Reference Angulo and Consuelo2012) documented that fifty-two Black organizations participated in the election of representatives to Cali’s Public Policy Coordinating Roundtable for the Black Population, but many of them were small, family-run foundations with few resources. She characterized the Black organizational infrastructure as weak, fragmented, and not mobilized (also see Quiñones Castro Reference Castro and Estiven2018).

What kinds of organizations did the people we interviewed envision as able to foster greater Black middle-class cohesion? Roosevelt, the accountant, wanted to affiliate with some group “that made social contributions so that, just like I came up, those that are coming behind us can also come up, or so that those who are in problematic situations can get out of them.” In other words, respondents were not talking generally about social clubs or professional guilds that were exclusive to middle-class Black people, but instead about what might be called, in the U.S. context, Black self-help or uplift organizations, be they economic, educational, or political (Butler Reference Butler2012; Gaines Reference Gaines1996; McCallum Reference McCallum2017). Roosevelt had a nagging sense that he should be doing more. When a friend referred him to our study, he said to himself, “Great, I want to be more involved with these kinds of activities. I like these kinds of things. But how I see it, there isn’t a movement, [but rather] there are small cells of people who are interested.” Roosevelt had not even found (or looked hard for) the small cells. Instead, he fed his curiosity by watching documentaries about Black people and history in the United States. To be sure, there are organizations working to push forward agendas to improve the lives of Black people in Cali and Colombia. However, our interviews indicate that they are not sufficiently visible, plentiful, coordinated, powerful, or relevant to gain the attention of the Black professional class.

Alan—a senior university professor and labor rights lawyer—saw this dearth of Black organizations as a real travesty. “That’s the saddest part,” he commented. “The only organizations that I haven’t represented [as a lawyer] are Black ones because we aren’t organized… We are in diapers. We don’t have anything.” As an example of why he thought the Black community was still in its infancy, organizationally, Alan described the recent election of the first Black governor of the nearby department of Cauca. The candidate won with very little initial support from Black mayors throughout the department. Each person was out for his or her own best interest, Alan opined, and there was no coordinated effort to convince Black mayors to support the Black candidate. They did not have a sense of attachment to another Black (middle-class) politician. It exemplified a lack of both mutual recognition and organizational capacity. Ultimately, however, the people of Cauca (a department that is 22% Black) decided, and the Black candidate won.

Everyone we interviewed—even those who themselves were members of Black organizations—thought there were few Black organizations in Cali, and even fewer that appealed to or were comprised of Black professionals. Moreover, organizing in the domain that might be especially fruitful for cultivating a Black middle-class consciousness—the workplace—was almost unthinkable.

Taboo against Black Professional Organizations

The original design for the project was to identify research subjects by contacting Black professional organizations and asking for referrals. This proved impossible in Cali.Footnote 8 The repetition of “no” answers to our question about Black professional organizations made this point definitive. We asked Mariela, “Is there an association of Black psychologists? A union or some type of organization?” Her answer was: “No, no, I realize, that I know of, no.” We asked sisters Yolanda, a doctor, and Yeni, a public accountant, about organizations of Black doctors or accountants. “Not that I know of,” answered Yolanda. “There is not,” answered Yeni more definitively. We asked Ronald, an architect, “Is there an organization of Black architects, a guild, a professional association?” His answer was less certain, but nonetheless telling. “Actually, I don’t know. I haven’t done the work to look. I don’t know what to tell you, really.” We asked Germán, a young lawyer who hailed from a family of Black lawyers, about a professional association of Black lawyers. We shared with him examples of such groups in the United States, where he had lived for a year. “Like a caucus,” he responded, showing that he understood the concept, and then continued, “There is a very clear predicament… When there is an organized movement…it causes a lot of push back.” Germán pointed out the resistance that Black professional organizing meets among White and Mestizo Colombians, but also sometimes among Black people as well. This taboo was especially strong in the work setting.

The fact that there were over one thousand Black organizations registered with the Colombian government is proof that there is no generalized prohibition against Black congregation. Belonging to a hometown association of Black people from Guapi, or to an Afrocolombian dance troupe, or to an association of women of African descent is a personal thing, away from the workplace and out of sight for most non-Black people. For Black professionals, however, the expectation is to fit in, to embrace one’s professional identity, and to not disrupt the façade of racial harmony by self-segregating. In our interview with Estela, an accomplished lawyer, we told her that we had learned in another interview that there was no organization for Black teachers. Estela knew the issue before we could even finish our question:

Interviewer: In the work world, for example, I interviewed a Cali public school teacher and I asked if they had an organization of Black teachers, and she told me, “No, because the others would say…”

Estela: That we are discriminating.

Interviewer: Discriminating, right, that they were racist.

Estela: They, when they see any identity, it’s racist. Here you can’t have that because they say it’s racist.

Labeling Black organizing as racist is related to the silences around Whiteness in Colombia. Neither White nor Mestizo appear as categories on the Colombian census. Instead, they fall under the rubric of “no ethnic group.” Whiteness represents the default, the unmarked, the normal, and the mainstream. Workplaces, and especially professional workplaces, are the places that instantiate and reproduce the mainstream. Racialized organizations would disrupt the silence of unmarked Whiteness and call into question myths about harmonious race relations and a lack of discrimination (Rodríguez, et al., Reference Garavito, César and Adarve2009; Twine Reference Twine1998). That Black employees or professionals may have grievances, want to mentor each other, celebrate the success of Black colleagues, or facilitate the entry of a next generation of Black professionals into that occupation, is viewed as divisive. The appearance of putting the interests of one race over another is racist (see Paschel Reference Paschel2016, p. 74).

We asked Pablo, a financial consultant in his late twenties in Bogotá, if it would be possible to organize a social project at his job to support Black communities. He responded:

Truthfully, no. My perception, because I haven’t asked myself this before, but I think it doesn’t work in the given conditions. Because, precisely what I was telling you about the race topic, it’s not like other issues that we might expose in a negative light. It’s also not something that we should privilege in any sense. Instead the approaches are more on social conditions, does that make sense? That in a certain place there might coincidentally be many Afros, fine, but it’s not attached to this specific racial population. Poor people, people in X sector of society, but we talk about the people in that sector, and not in race terms. That’s why, let’s say, we don’t split [groups] up like that. It doesn’t work that way.

Pablo had been so deeply socialized by this taboo that he had not before considered organizing something explicitly around Black people. Black upward mobility required silencing (or at least masking) racial issues in order to integrate into the silence of White predominance, power, and control of the professional sphere. Black middle-class amorphism, thus, mirrors the shapelessness of Whiteness. The taboo against Black professional organizing inhibits the formation of a Black middle-class political consciousness and leaves the individual as a singular actor focused on personal success and gain.

Individualism and Personal Status

An individualist ethos directly contradicts the definition of group consciousness, which stresses collective responsibility and action (McClain et al., Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Walton and Watts2009). Many interviewees saw an individualist streak even among Black leaders whose job it was to work on behalf of the group. Dario—a banker in his thirties who lived in Cartagena but was from the department of Chocó—was critical of some Black middle-class leaders who worked in government and non-profit organizations meant to improve the condition of Black people in Colombia. He argued: “Those spaces are also littered with people that use the ethnic fight and the racial inequalities that exist to benefit themselves. And they slow down the whole process of effective policy.” Dario offered several examples of organizations and roles that he thought were ineffective because the person was just there to protect their status. While the constitutional openings and the Law of Black Communities were meant to increase participation by Black citizens in securing their rights, Dario saw the Black organizational sphere as paradoxically like a “political fortress” that was too closely linked to “elite economic interests represented by this or that congressperson,” and that operated like a bunch of “favors traders.”

Many other interviewees shared this critique of Black elected officials, bureaucrats, and people who had risen to posts of leadership to supposedly advance the Black agenda. Víctor complained that the Black people who occupied the two guaranteed seats in congress did not really represent Black people but were instead concerned about their own gain. They were controlled by Mestizos. “You know there is the direct purchase of votes?” he asked us in the interview to make sure that we were aware of the level of self-dealing. He continued:

[Mestizos] throw in a lot of money, they buy votes and then the seats are theirs. The person who is in the seat is a Black person, but the seat belongs to a person that is not Black, and it is not used to help the Black population [la población Negra]…They are driven by politics, for their own political work, to see how they can maintain their own wealth, their power, their things, but the community is not important to them.

Víctor was identifying a clear clientelist relationship between Black professional leaders and White/Mestizo sponsors, to the detriment of the Black community (Cárdenas et al., Reference Cárdenas, Rojas, Restrepo, Rosero and Hooker2020). Personal power among “emerging elites and Black political classes” perverted the purpose of the work and overshadowed the needs of intended beneficiaries (Lao-Montes Reference Lao-Montes2009, p. 231).

Another interpretation we heard was that such patronage was intended to divide, corrupt, and weaken. This was Nelson’s perspective on the same topic. He argued:

When the government says “Okay, you all are a collective of fifty people, divide up these three bananas.” That’s what the government does. “Divide up these three bananas amongst yourselves.” Obviously, there are going to be problems. The problem isn’t the community, but rather the government that gives three bananas to fifty people.

The two seats in congress, the meager support for Black organizations, the few affirmative action seats in universities—all these things generated competition. Whether it was betrayal, as Víctor saw it, or manipulation, as Nelson interpreted it, the result was personal profit and benefit among Black professionals who were supposed to be acting on behalf of the collective. Such individualism created a wedge against unification (Viveros-Vigoya Reference Viveros-Vigoya2012).

If leaders were distanciados because of their personal ambition, this was also true at the local level and among everyday middle-class Black people. Javier was a university professor and business consultant in his fifties with brown skin who self-identified as Mulato, but generally preferred not to talk in racial terms. Yet he had taught many rising Black professionals and worked with Black businesses and organizations in Cali. He had watched more than a few well-meaning Black professionals become more self-interested. He told us:

There are many very intelligent Black men and women, college graduates that are looking to start projects for the community, but unfortunately when they do the projects they forget about the people and start to benefit themselves, appropriate [the benefits]. They say, “We’re going to start a foundation and we are going to create educational opportunities for all of the Black community, the kids of such-and-such area that need it.” They get, to pick a number, 200 million pesos [over $50,000]. Only twenty million pesos enter the organization and the rest, they change, their status changes… I have seen it.

Javier described a chain of events, even among middle-class Black people who began with a desire to contribute to Black progress. The temptations of personal gain—of, as Estela put it in her interview, “let’s see what more can I get”—take over quickly and the commitment fades. They focus more on protecting their own status. Javier said they become conceited. Nelson and Nicol called it selfishness, or egoismo, llenarse de ego. The work of working together, as a group, toward a shared end, is a casualty of this individual ethos. The possibility of a Black middle-class political consciousness gets thwarted.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

We have shown that the Black professionals we interviewed saw themselves as part of a Black middle class in Cali and affirmed that such a category existed. Yet they were similarly in agreement that they did not feel attached to others in this category and that the Black middle class did not act as a group and, instead, was internally disconnected, not tied to any larger Black social movement, nor collectively interested in supporting the upward mobility of less advantaged Afrocolombians. In addition to replicating the findings of Viveros Vigoya and Gil Hernández (Reference Viveros Vigoya and Hernández2010), we have deepened their analysis by systemizing the reasons for this alienation: no collective cultural signifiers, weak organizations, charges of reverse racism, and a strong focus on personal advancement and gains. As a result, Black middle-class status fails to bind Black middle-class Colombians into a group.

Why does Black Colombian middle-class amorphism matter? To answer this question, we broaden our scope to ask what role the Black middle class has played in politics in various contexts. The middle is a place of relative and constrained power because it is subjected to the power of some higher entity (Pattillo Reference Pattillo2020). In the Colombian case, the recognition of White/Mestizo patrons of Black political and organizational figures illustrates those constraints. Yet, the middle also offers opportunities to broker resources for people below (Pattillo Reference Pattillo2007). Many Black organizations in Colombia do this through their management of university scholarships and special admissions routes. In other words, the allegiances and commitments of the Black middle class can be variable and unpredictable, group-minded or self-interested.

In the U.S. context, there are as many examples of Black middle class self-sacrifice and selflessness in politics (Higginbotham Reference Higginbotham2001; Pichardo Almanzar and Herring, Reference Almanzar, Nelson and Herring2004; Shaw Reference Shaw1996) as there are of Black middle class appropriation of resources and the silencing and control of more marginalized Black people (Arena Reference Arena2012; Cohen Reference Cohen1999; Forman Reference Forman2017). Most examples fall in the middle, with Black middle-class people meaning well, but often doing some harm in the process (Pattillo Reference Pattillo2007). There has not been the same kind of focus on the Black middle class as a set of actors—as a group or not—in the Latin American context.

Hence, we stress a dilemma that faces Black political actors. On the one hand, Black middle-class amorphism can deny Black-movement organizations access to Black professional expertise and connections. This was a concern of some of our respondents who thought that the egoism of those who were supposed to represent Black people cut off access for making real changes in where and how monies were spent. The people we interviewed had many talents, with experience in finance, psychology, writing, researching, and engineering. These skills could be put to use in managing infrastructure projects to improve roads in Black rural areas or offering counseling services to Black migrants in Cali traumatized by episodes of violent displacement. Of course, not everyone’s formal employment will be in service of Black progress, but the skills and networks of the Black middle class could be used in every sector—from banking to education to journalism to science to government. Outside of the workplace, Black professionals have access to the technologies, resources, institutions, and communication media to amplify a range of Black political projects.

On the other hand, strong participation by an organized Black middle class might suppress or obstruct more radical political demands. Upward mobility is rewarded with comfortable pleasures: nice houses, neighborhoods, cars, leisure, and frequent or occasional escapes from the stigma of the intertwined identities of Blackness and poverty. Radical protest would risk such comforts. Even simply organizing along racial lines at work raises the eyebrows of White/Mestizo colleagues and reminds Black professionals that their racial difference might close off further opportunities. These facts have a conservatizing effect, a narrowing of the imagination of what Black people might achieve as a collective, because what Black middle-class people have achieved individually seems quite good already. Upward mobility itself is deeply rooted in an individualistic and capitalist paradigm (Román Reference Román2017), hence it is unlikely to yield political subjects who would work to correct the most stratifying aspects of capitalism. Agustín Lao-Montes (Reference Lao-Montes2009) critiques the “alliances between Black conservative elites in Colombia and the United States” who push a neoliberal agenda that, he argues, further impoverishes most Black Colombians (p. 210). In this way, the fact that the Black middle class in Colombia has not congealed into a group could disencumber grassroots Black political movements in Colombia from narrow consumerist political goals or from the respectability politics that Black middle-class leaders often proffer (Higginbotham Reference Higginbotham1993; Kelley Reference Kelley1993).

The greater socioeconomic diversity within Black communities across the globe calls for investigation into how upward mobility intersects with Blackness at the local level (Marsh Reference Marsh and Hunter2018). We present our findings as a contribution to this new conversation, with a particular emphasis on what the Black middle class might mean for Black politics. In the case of Cali, Colombia, the category of the Black middle class is amorphous, it is not a group, and there is no mutually cognizant political consciousness. Gathering additional empirical cases will facilitate comparison and ultimately the development of further theorizing about the conditions under which such groupness materializes and its effects on the collective wellbeing of Black people, both locally and globally.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was co-funded by the Fulbright Commission and ICETEX in Colombia and housed in the research group “Estudios Étnico-raciales y del Trabajo en sus Diferentes Componentes Sociales,” in the School of Social and Economic Sciences at the Universidad del Valle. Fernando Urrea Giraldo provided crucial support in securing the funding and in offering feedback on the research project. We also thank Jan Grill, Beatriz Guerrero, Mariela Palacios, Aurora Vergara, Carlos Viáfara, and the Centro de Estudios Afrodiaspóricos at ICESI University for additional guidance, support, and access. We are especially grateful to the interviewees and survey respondents for sharing their perspectives.