Hurricane Katrina hit the US Gulf Coast as a category 3 storm on August 29, 2005, causing extensive damage to parts of Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama. No one foresaw the extent of the damage it would cause. Hurricane Katrina was the costliest storm in US history, causing $80 billion worth of immediate and eventual damage and taking approximately 1800 lives.1, 2 Adding to the atrocity, the areas hit were already financially crippled—Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama are the first, second, and eighth poorest states, respectively.3

Thousands of people were evacuated from flooded areas of the 3 states. Most of them were transported in buses heading for safer ground in Georgia and other parts of Louisiana, Alabama, and Texas. Unfortunately, a portion of New Orleans' older adult population either refused or could not evacuate because of lack of transportation. Only 35% of New Orleans' older adult population had their own vehicles before the storm. Of the deaths in New Orleans, mostly drowning victims, 74% were people older than age 60, and 50% were older than age 75.Reference Simerman, Ott and Mellnik4

In the days and weeks following the storm, more than 200,000 men, women, and children were evacuated from the New Orleans area where Katrina had caused the majority of its damage, flooding 80% of the city and causing the deaths of 1100 people. Approximately 23,000 people were brought to the Reliant Astrodome Complex (RAC) in Houston, Texas. The American Red Cross organized housing at the Astrodome, and the Harris County Hospital District organized a comprehensive medical unit for the evacuees. Medical school faculty from the Baylor College of Medicine worked with the Harris County Health Department and the Harris County Hospital District to provide the clinician infrastructure. Health care professionals and physicians from every discipline were deployed to the facility to address the medical and social needs of the shelters' residents.

A large percentage of evacuees seen in the Reliant Astrodome Medical Complex were 65 years old or older, and many of these people were too frail to access the services provided. Physical impairments kept some from being able to walk to the bathroom, eat on their own, or hear and see announcements being made over the loudspeaker and broadcast on the electronic display sign. The most urgent cases were gravely ill older people needing to be hospitalized immediately. Many others were less ill, without family, and were placed on cots on the Astrodome's large shelter floor.

Among the health care workers at the Astrodome were gerontological health professionals including geriatric physicians, nurses, social workers, adult protective service workers, members of the Area Agency on Aging, and other gerontological professionals who were skilled in addressing the complex needs of frail older adults. They observed that the older adult population's unique medical and social needs were not being met adequately by the center's current facilities, that some older people had no one to advocate for them or help them access medical and social resources, and that a special approach would need to be developed to minimize further suffering. A team of gerontologists from varying disciplines gathered and formed a team to help vulnerable older people with no family members access medical and social services at the shelter and from the county government. They concluded that a rapid screening tool was needed to determine who needed help, how imminent their needs were, and what interventions could be offered. This team adopted the name Seniors Without Families Team (SWiFT) and developed, piloted, and implemented a rapid triage tool to address the needs of frail older adult disaster victims. During the subsequent 2 weeks, until the RAC closed, the SWiFT team successfully assessed and triaged 228 vulnerable older adults using the SWiFT tool.

METHODS

SWiFT Tool Development

SWiFT members devised a tool to screen and triage vulnerable elders with the most urgent needs by assessing cognition, medical status, financial assistance needs, social service needs, and the ability to perform activities of daily living. The tool was designed to facilitate the triage of vulnerable elders so that proper and timely care would occur. Items were chosen based on the expert's knowledge of the literature and their collective clinical experience. After the first day of assessment, SWiFT members reconvened to discuss what worked effectively and what alterations needed to be made to the SWiFT tool. The tool was finalized and the SWiFT triage system was established after modifications were made to rearrange the ordering of the questions.

The SWiFT Tool

The SWiFT tool (Fig. 1) consists of 13 questions partitioned into 3 categories (medical/mental health, financial, and social) that assess each individual's current level of needed assistance. There were 3 interventions at the RAC: medical/placement, case management support, and referral to a Red Cross volunteer. A SWiFT level 1 indicated the need for immediate medical/placement care, whereas a level 3 represented minimal necessary assistance, thus establishing a prioritized triage system. Individuals who received a SWiFT level 1 designation generally exhibited cognitive deficits, the need for assistance in basic activities of daily living (eg, walking, bathing, eating, medication administration), and/or reported an untreated medical condition such as diabetes, heart disease, and/or hypertension. The selected medical conditions were chosen because diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, and memory problems are the most common conditions affecting the health of elders. Basic activities of daily living were assessed along with medical conditions, because impairments in these activities directly affect the outcome of vulnerable elders during disaster times. For instance, with the disruption in care it was important to be able to assess each older person's ability to care for him- or herself, especially the ability to properly administer medications. The cognitive components incorporated into the SWiFT level 1 focused on assessing orientation to place and time and working memory. Despite its relevance, the orientation to person was not assessed because it was important to assess for cognitive impairments using questions that could easily be substantiated under the current conditions.

FIGURE 1 SWiFT tool.

A SWiFT level 2 designation identified individuals who needed assistance with housing, changing of residence and locating established income and entitlements such as Social Security, Section 8 housing funds, Medicare, and many others. These financial needs were chosen because they were thought to be the most important and most relevant financial matters needed to aid proper placement once the shelter closed. A SWiFT level 3 designation indicated a need for assistance in locating family and friends or having other problems that were handled by Red Cross volunteers. Vulnerable older adults who arrive at the shelter alone are not likely to fare well without assistance.

Tool Pilot Testing

To administer the tool, SWiFT field teams comprising a social worker and a medical professional, such as a nurse or nurse practitioner, walked among the cots on the Astrodome floor looking for elders who were by themselves. The teams included both a social worker and medical professional so that they could act quickly if they saw an urgent medical or social need. The purpose of selecting elders without family members was that those with family members already had advocates. Because the major task was to appropriately place the senior, SWiFT members also wanted to avoid separating families, as had happened during the flood evacuation process from New Orleans. Each team of 2 walked through the shelter area and talked with the vulnerable older adults that they found and completed the assessment forms. Approximately 3 to 10 minutes were needed to complete the SWiFT assessment on each older person.

The SWiFT members used donated cell phones, land line telephones, and computers with Internet access to communicate among themselves and with the RAC's central command. Clipboards with the SWiFT tool were distributed to field teams every morning to be returned to the SWiFT leadership desk. Despite the chaos and disorder at the RAC and the lack of a study coordinator, the SWiFT team was able to use the tool for 2 more weeks, assessing as many vulnerable elders as possible until the clinic closed and the evacuees had been relocated to more permanent housing.

RESULTS

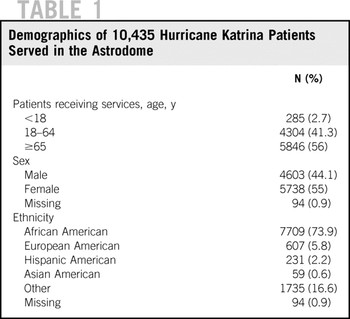

Using standard descriptive statistical techniques, the results describe 2 different subsets of individuals. Table 1 describes the demographics of the majority of individuals serviced in the Astrodome in Houston following Hurricane Katrina. Physicians and other health care professionals at the RAC Medical Clinic saw 10,435 patients; 56% (5846) were 65 years of age or older and 55% were female. Of patients for whom ethnicity was known (83% of patients overall), 73.9% (7709) were African American.

TABLE 1 Demographics of 10,435 Hurricane Katrina Patients Served in the Astrodome

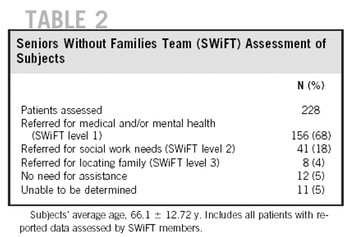

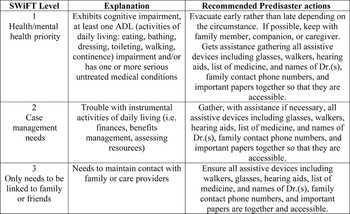

Table 2 describes the subset of individuals receiving services in the Astrodome shelter who were also triaged for care based on the SWiFT tool. The average age of the older people served by the SWiFT members was 66.1 ± 12.72 (years ± SD). Of those, 68% were classified as SWiFT level 1, 18% as SWiFT level 2, 4% as SWiFT level 3, and 5% needed no further assistance. Hypertension was the most common diagnosis among the 228 patients, with 54% of them having the condition. Also, 27% had diabetes, 22% had heart disease, and 10% had memory problems. Figure 2 suggests some preparatory steps associated with the SWiFT tool assessment for disaster preparedness.

TABLE 2 Seniors Without Families Team (SWiFT) Assessment of Subjects

FIGURE 2 SWiFT tool use in disaster preparedness.

DISCUSSION

Vulnerable older people evacuated to disaster shelters vary greatly in their physical and social needs. Some elderly residents are fully independent, without chronic disease, cognitive impairment, or any limitations in their ability to perform the activities of daily living. Others may have chronic disease with mild limitations in their ability to perform activities of daily living, but still manage to function independently at home and can do so in the shelter setting.

Because more vulnerable elders are likely to have difficulty in evacuating during a disaster, it is not surprising that such a large percentage of the Superdome evacuees received a designation of SWiFT level 1. Many likely had difficulty performing activities of daily living before the disaster. Others may have functioned well before the disaster but suffered from disruption of medical care systems since the event, leaving them without support or assistance with the activities of daily living. To varying degrees, many older adult shelter residents may experience increased disability brought on by of the stress of the disaster.

Vulnerable elders who arrive at the shelter with friends or family, or meet people who take them into their care, have a greater likelihood of obtaining access to the medical services they need as well as assistance with the activities of daily living. Friends and family also can assist them with obtaining needed benefits and services, mitigating psychological trauma, and planning for a return to their homes or appropriate placement.

Vulnerable elders who arrive at the shelter alone are not likely to fare well without assistance. The challenge for those organizing and planning disaster relief efforts is the triage of those who need extra assistance. Generally, shelters are not staffed with people trained in geriatric medicine or gerontology. Many facilities lack formal systems to provide assistance with the activities of daily living. Even when there are medical and social services on site, vulnerable older adults often lack the physical or cognitive ability to access those services. Some may have medical needs that exceed the scope of services provided by the facility. In some cases, elders arrive with life-threatening conditions, are demented, delirious, and/or require total care.

To meet the needs of vulnerable older people who lack support in the shelter setting, it is necessary to devise a system to identify them and assess their medical, functional, and social needs, including their mental status. Based on the results of the SWiFT tool assessments, vulnerable elders whose medical needs could be met by on-site medical services were treated in the RAC medical clinic. Elders whose medical needs exceeded the capacity of on-site services were transported to hospitals, nursing facilities, or other appropriate placements. Similarly, those who needed assistance in performing activities of daily living were placed in settings where those needs could be met. The tool also elicited information related to financial needs (SWiFT level 2) that were later addressed by local case managers who volunteered their time. An older adult with a SWiFT level 3 designation was referred to a Red Cross volunteer.

CONCLUSIONS

The SWiFT tool provided a common language for the various professionals and facilitated assessments and data collection. Furthermore, its simplicity and brevity made it well suited for administration in the chaotic and stressful disaster shelter setting. Systems similar to the SWiFT triage system are necessary to screen vulnerable older people for medical, financial, and social needs to ensure proper and timely care during disaster situations. The SWiFT tool could likely be adapted for different disaster situations in different locales. Assigning a SWiFT designation could provide a universal language for health professionals and disaster planners alike, which may lead to a uniform and more rapid approach to caring for elders during disaster situations. In fact, SWiFT levels can indicate the appropriate level of care for people who must be transferred from a temporary shelter to a more comprehensive and advanced care facility.

The SWiFT tool may also be useful in disaster preparations. It establishes a uniform designation of level of need and provides general guidelines for the type of assistance required. Individuals, family members, home health nurses, or physicians could easily designate that a frail or vulnerable elder was a SWiFT level 1, 2, or 3. Appropriate steps based on SWiFT designation could be undertaken by the older adult or his or her caregivers to ensure proper care and evacuation in preparation or response to a disaster. People who are completely independent regardless of age would not have a SWiFT designation and would follow the guidelines for the general population regarding emergency preparedness. Because one's SWiFT designation may change owing to new health conditions or positive health interventions, a yearly evaluation with the SWiFT tool could be performed on an individual's birthday.

Tools are available to triage vulnerable elders in times of disaster; however, these tools provide triage based on physical trauma–related scores and have been reported as lacking sensitivity in assessing older people.Reference Almogy, Luria and Richter5, Reference Scheetz, Zhang and Kolassa6 This lack of sensitivity may be in part due to the fact that elderly trauma victims present unique challenges.Reference Callaway and Wolfe7 The SWiFT tool integrates cognitive, physical, social, and financial domains that provide a brief but informational global needs assessment. Future research should be conducted on the SWiFT tool to assess interrater reliability and validity. Drills could be conducted in nursing and continuing care facilities, assisted living facilities, and retirement communities, and with older adults still living in their own homes to determine the efficacy of this rapid screening tool. These approaches would provide known-groups analyses and thus potentially establish the reliability and validity of the tool. The tools could then be reanalyzed in real-time disaster situations. Studies also should analyze experience from previous disasters regarding the efficacy and outcomes of early transfer versus late transfer for nursing facility residents. Vulnerable elders are much more likely to experience ill effects in disaster situations; research is needed to develop the instruments and interventions that can limit the loss of life and suffering in this population.

Authors' Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank all of the individuals and organizations, especially the Harris County Hospital District, who graciously provided help and support during the disaster relief efforts following Hurricane Katrina. It was the collective efforts of each and every person involved that created an unprecedented and highly successful response to this unfortunate historical event.