Emergencies and disasters can cause disorder in social and organizational activities; such disorder may be more than the capacity of the damaged area to cope with associated financial and physical damages. On other hand, effective management of these destructive and damaging events depends on predicting the problems associated with these events and planning to respond to them effectively.Reference Khankeh and Zavareh 1 The first and most important demand of people in these events is their health and well-being; therefore, health systems should play a key role in reducing mortalities and injuries.Reference Khankeh and Zavareh 1 Hospital preparedness to cope with disasters is an important part of health system programs to reduce loss and disabilities. In fact, the international slogan of preparedness for coping with emergencies and disasters, especially hospital preparedness, is the main program in disaster management at the national level, especially in disaster-prone countries.Reference Mehta 2 The ability to provide medical and health care during a sudden increase in the number of patients or victims of emergencies and disasters is the main concern of health systems and hospitals, in particular, preparing for and improving surge capacity.Reference Terndrup, Leaming and Adams 3 There are several definitions of surge capacity. According to the American College of Emergency Physicians, surge capacity is the health care system’s ability for timely management of situations such as a sudden increase in the number of patients admitted to the hospital using available resources. 4 In addition to the use of available resources to manage a sudden influx of injured people or patients, several studies consider surge capacity as the ability of hospitals to increase available resources in response to disasters.Reference Dayton, Ibrahim and Augenbraun 5 , Reference Hick, Barbera and Kelen 6 Surge capacity of hospitals has 3 main components: human resources, specialized and nonspecialized equipment, and physical space.Reference Hanley and Bogdan 7 Surge capacity programs should be developed and implemented on the basis of evaluation and risk analysis. Therefore, before developing this program, risks or hazards threatening hospitals must be identified, and hospital vulnerability characteristics must be extracted.Reference Khankeh, Mohammadi and Ahmadi 8 The hospital surge capacity program is dynamic and must be revised and updated constantly.Reference Kelen, McCarthy and Kraus 9 , Reference Schultz and Stratton 10 The aim of the current study was to perform a systematic review of hospital surge capacity in emergencies and disasters with a preparedness approach. The results of the current study may help health field managers in hospitals with capacity-building on the basis of surge capacity components (staff, stuff, system, structure) and may help to promote hospital preparedness for appropriate response to emergencies and disasters.

METHODS

The present study was a systematic review of publications and documents relating to hospital surge capacity in emergencies and disasters with a preparedness approach. The review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 11

Search Strategy

This study was conducted during November 2015 to review all published articles in the field of surge capacity of hospitals in emergencies and disasters. For this purpose, we studied databases including Google Scholar (Google Inc, Mountain View, CA), ISI Web of Science (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY), Science Direct (Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands), PubMed (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD), Scopus (Elsevier), Ovid (New York, NY), ProQuest (Ann Arbor, MI), and Wiley (Hoboken, NJ) from January 1, 2000, to October 22, 2015. The search key words included “surge,” “surge capacity,” “preparedness,” “hospital emergency department,” “hospital,” “surge capability,” “emergency,” “hazard,” “disaster,” “catastrophe,” “crisis,” and “tragedy.” Using MeSH (Medical Subject Headings; National Library of Medicine), synonyms of these keywords were also extracted. These included “hospital communication,” “hospital department,” “high volume hospital,” “hospital information system,” “hospital planning,” “hospital rapid response,” “hospital material,” “hospital personnel,” “hospital bed capacity,” “equipment,” and “supplies of hospital.” Using OR and AND, key words were combined and entered in the search box of the databases as follows: (surge capacity) AND (hospital OR hospital communication OR hospital department OR high volume hospital OR hospital information system OR hospital planning OR hospital rapid response OR hospital material OR hospital personnel OR bed capacity OR hospital equipment and supplies) AND (disaster OR emergency OR hazard OR crisis OR tragedy OR mass casualty incident OR catastrophe).

Selection of Articles and Documents

Independent reviewers (HS and FR) screened abstracts and titles for eligibility. When the reviewers felt that the abstract or title was potentially useful, full copies of the article were retrieved and considered for eligibility by both reviewers. If discrepancies occurred between reviewers, the reasons were identified and a final decision was made on the basis of agreement by a third reviewer (AR).

Evaluation of Selected Publications

Inclusion Criteria

The first inclusion criterion was articles or documents that investigated the surge capacity of public and private hospitals in emergencies and disasters. The second inclusion criterion was consideration of at least one of the components of hospital surge capacity in any real disaster.

Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion criteria included studies published in languages other than English. In addition, editorial studies, studies conducted before 2000, and studies that investigated the surge capacity of treatment locations other than hospitals were excluded. To obtain authoritative information, this review included only peer-reviewed journal articles. Selection bias might therefore exist in this study in terms of publication bias, especially concerning government reports that were not accessible.

RESULTS

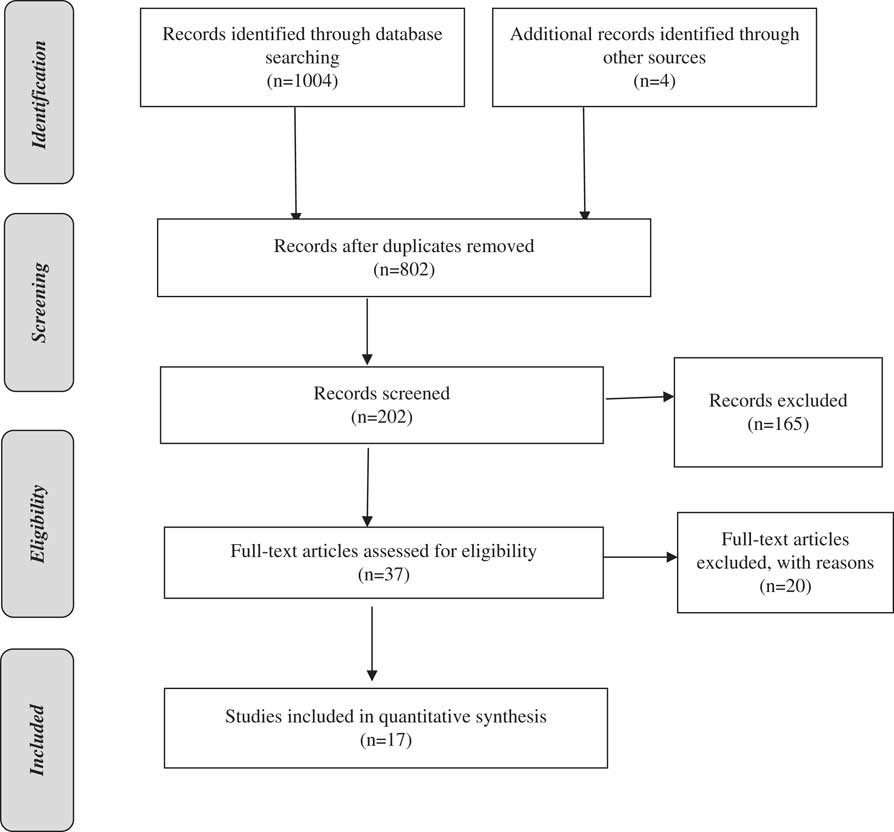

The initial electronic database search of the literature resulted in a total of 1008 articles. At the next step, duplicate articles were eliminated and the number decreased to 802 articles. Using systematic screening, we reviewed the titles to find those related to hospital surge capacity and selected 202 articles. In the next step, abstracts of the articles were studied and 37 articles were selected to be fully reviewed. In this step, 165 articles were excluded. After that all of the selected articles were completely read and on the basis of the inclusion criteria only 17 articles (1 randomized controlled trial, 2 qualitative studies, and 14 cross-sectional studies) that reported the surge capacity of hospitals in emergencies and disasters were selected. Figure 1 shows the strategy for searching and selecting the articles in accordance with the PRISMA Guidelines.Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 11 All studies focused on hospital surge capacity in different types of real or potential disasters. The studies were mainly conducted in the United States, Australia, Taiwan, South Africa, and Japan. The results showed that most studies conducted on surge capacity related mainly to hospitals in different states in the United States. Of the total extracted papers, 384 different hospitals were investigated.

Figure 1 Flow Diagram Showing Selection of Articles Reviewed in Accordance With the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines.

Details of each study and their special features regarding authors, year, sample size, study type, hospital location, type of components, and main concepts were evaluated. The summaries of each article related to hospital surge capacity in emergencies and disasters are shown in Table 1.Reference DeLia 12 - Reference Traub, Bradt and Joseph 25 The study results indicated that there are various ways to increase surge capacity in 3 domains: staff, stuff, and structure. The most important way to improve surge capacity in the staff category is to call shift workers to the hospital emergency department and alternative spaces, to request workforces from other hospitals and medical centers, and to call for volunteer and retired employees with the aim of increasing the personnel capacity of the emergency department as the first-line encounter with the disaster. In the stuff section, using existing equipment in the crisis warehouse of the hospital, transferring medical equipment from unnecessary units to key units, and providing required equipment from organizations outside the hospital with the aim of increasing the capacity of the main units in the hospital can enable appropriate responses to emergencies and disasters. In the structure section, we can increase the physical treatment space, including space for entrance and exit of the injured; categorize and discharge inpatients via reverse triage with the aim of evacuating the emergency department and evacuating patients from inpatient units whose treatments can be postponed; prepare alternative places with the aim of increasing the physical capacity for triage and emergency treatment of the patients; integrate hospital wards; cancel elective surgeries with the aim of increasing the capacity of the surgery rooms in order to be properly ready to do emergency surgeries; use spaces like parking, amphitheaters, halls, dining rooms, and other hospital areas for therapeutic spaces according to the recommendations of the hospital’s crisis committee; exercise incident response operational programs with a focus on providing surge capacity for different hazards; and finally, increase capacity to transfer and displace intra- and interhospital victims.

Table 1 Summary of Articles on Hospital Surge Capacity in Emergencies and Disasters

DISCUSSION

Different meanings and classifications of emergencies and disasters are given in various studies. 26 Most studies have classified surge capacity concepts in 3 general sections of stuff, including supplies and equipment; staff, including all types of personnel; and structure, including facilities and programs.Reference Kaji, Koenig and Bey 18 , Reference Nager and Khanna 27 - Reference Hotchkin and Rubinson 31 Various other studies have also stated that hospital surge capacity should include a system component in addition to staff, stuff, and structure. These studies also stressed that all 4 concepts of surge capacity are important and that the concept of system is a main and necessary concept and that surge capacity cannot be managed appropriately without it. This concept has various components, including command and control, communication, coordination, continuity of operations, and community infrastructure.Reference Hick, Christian and Sprung 23 , 32 , Reference Barbisch and Koenig 33 A number of studies have classified surge capacity of hospitals in other forms, including space, staffing, supplies, and system.Reference Bradt, Aitken and FitzGerald 15 , Reference Hick, Hanfling and Burstein 34 There is no specified or single standard criterion for evaluating hospitals’ surge capacity. In the United States, surge capacity is considered when hospitals can increase their current resources in various areas at the rate of 5% to 15%.Reference DeLia 12 Other studies reported that surge capacity is acceptable when this rate is 20% to 35%.Reference Schultz and Stratton 10 The difference can be due to the diversity in structural, economic, facilities, and demographics of various countries. One of the studies emphasized that surge capacity is the ability of the hospital to provide necessary concepts during the occurrence of emergencies and disaster and does not include current hospital programs.Reference DeLia 12 Considering the concept of stuff, based on the Health Resources and Services Administration, 500 beds are required and necessary in an incident per 1 million people.Reference DeLia and Wood 19 On the other hand, the surge capacity of a hospital is not only limited to an increase in the number of beds, but these beds must be ready to provide medical and health services under normal conditions and be equipped with expertise, human resources, and sufficient facilities and be accessed quickly.Reference DeLia 12 , 35 , 36 Studies have also shown the relationship between the surge capacity of hospitals and the occupancy rate of beds. When the occupancy rate of beds is high and unoccupied beds are low in a hospital, surge capacity is limited and this relationship can be reversed.Reference DeLia 12 , Reference Kanter and Moran 13 Hospitals require both specialized and nonspecialized equipment in a disaster, and this equipment must be available in the crisis storehouse so that it can be added to the current equipment level when needed. Various studies have reported different methods for increasing the capacity of hospitals in the structure dimension, especially physical space, and these cases include lack of admission of outpatients who are able to walk, transfer of admitted patients from the emergency department to hospital corridors, canceling of selective operations, discharge of patients with appropriate status, redesigning of physical space of departments in terms of arrangement of beds and equipment to create accessible space, expansion of portable hospitalized units, and use of physical nontreatment spaces of the hospital such as dining halls, auditoriums, and hallways to care for disaster patients.Reference Schultz and Stratton 10 , Reference Kelen, Kraus and McCarthy 14 , Reference Bradt, Aitken and FitzGerald 15 , Reference Welzel, Koenig and Bey 21 , Reference Hick, Hanfling and Burstein 34 , Reference Mahoney, Harrington and Biffl 37 Other strategies to increase the capacity of hospitals in the structure dimension are coordination of public and nonpublic organizations to provide resources required by hospitals in the time of disaster, having operational programs to respond to emergencies and disasters, and having performance programs such as activating the hospital response program, activating Hospital Incident Command System, practicing operational programs of response to emergencies with centrality of surge capacity for various hazards, coordinating the prehospital system with both the hospital and the emergency operations center, and systematic triage of victims at both the hospital and prehospital systems.Reference Lee, Ghee and Wu 16 , Reference Peleg and Kellermann 38 - Reference Bloch, Schwartz and Pinkert 40 During emergencies and disasters when hospitals are faced with increased demands, one of the programs to increase capacity is reverse triage.Reference Kelen, Kraus and McCarthy 14 , Reference Satterthwaite and Atkinson 17 , 41 In the reverse triage method, victims’ status and patients’ transfer hazard must be considered in emergencies and disasters. In this regard, staff of hospitals must be trained and educational workshops are required for better reverse triage in order to increase knowledge and experience of staff. To increase capacity in the staff dimension, various studies have referred to several cases, including the use of all medical and nonmedical hospital staff and determining their tasks and training during disasters, issuing valid certificates to be used in disasters, preparing a list of staff and updating it, and using medical and nursing students as well as volunteer and retired forces. On the other hand, countries can use medical and nonmedical military forces such as the army to meet human resource needs.Reference Bradt, Aitken and FitzGerald 15 , Reference Satterthwaite and Atkinson 17 , Reference Stratton and Tyler 20 , Reference Welzel, Koenig and Bey 21 , Reference Hick, Christian and Sprung 23 , 41 In contrast, one study reported that using volunteer forces to increase capacity could be a factor in reducing the quality of services provided in hospitals. If use of these forces is not planned appropriately, it could be a deficient factor in establishing surge capacity in hospitals, because initial resources may be wasted in managing these volunteers.Reference Kaji, Koenig and Bey 18 It is still impossible for hospitals to determine the competence, skill, and certification of volunteers, and this factor causes increased disorder in response to disasters. Therefore, having a database for collecting information from therapeutic and nontherapeutic volunteers will be helpful for identifying these people and improving hospitals’ surge capacity response.Reference Abir, Davis and Sankar 24 , Reference Traub, Bradt and Joseph 25 , Reference Schultz and Koenig 28

CONCLUSION

Hospital surge capacity is one of the most important hospital preparedness programs for appropriate response to emergencies and disasters. The present review revealed different classifications for surge capacity methods and concepts. We found no consensus on a unified classification. Also, studies showed that there are different ways to increase hospitals’ surge capacity. Therefore, the results of the current study could help health field managers in hospitals prepare for capacity-building based on different surge capacity components. These results may also help to improve and promote hospital preparedness programs for appropriate response to emergencies and disasters according to a situational assessment of each hospital’s environmental requirements.