Following the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the historical increase in the frequency and intensity of natural disasters and mass shootings in the United States, disaster nursing as a field has experienced unprecedented growth both in participant interest and in the advancement of the science to support practice. NojiReference Noji 1 described disasters quite simply as “events that require extraordinary efforts beyond those needed to respond to everyday emergencies” (p 1). In the United States, the number of disaster events has been steadily increasing over the last 6 decades (Figure 1) 2 and the rate of mass shootings has tripled since 2011.Reference Cohen, Azrael and Miller 3 This increased frequency and intensity in natural and man-made disasters has necessitated an expansion of preparedness and disaster response activities and training and warrants an understanding of the roles of various health professional groups in responding to a disaster. Nurses play a pivotal role in disaster preparedness and response; therefore, it is imperative that all nurses and the larger health care community understand the unique characteristics associated with the role of disaster nursing. We suggest that the time has come to collectively define our scope of practice, establish standards for care and identify best practices, and pursue the establishment of an independent professional organization within the field of disaster nursing. This will establish the necessary foundation for recognition and eventually national certification of disaster nursing as a bona fide specialty within the profession of nursing.

Figure 1 Major Disaster Declarations Over the Last 6 Decades. Adapted from FEMA Disaster Declarations by Year, available at http://www.fema.gov/disasters/grid/year. 2

Nursing’s unique contribution to crisis management and the clinical care of disaster victims has been frequently underreported in the literature. The absence of a robust literature base for disaster nursing further complicates our ability to articulate best practices and standards for care. This situation raises the questions, “How does disaster nursing differ from generalist, public health, or emergency nursing?” and “What defines the specialty care of disaster nursing?” In order to answer these questions and accurately describe disaster nursing roles to others in the health care and emergency management community, it is helpful to review our historical roots as a profession and the path taken to this point.

HISTORICAL FOUNDATION

Nursing as a profession has a rich history with the roots of modern nursing practice as we know it founded in the arena of disaster nursing. Florence Nightingale’s work as a disaster nurse during the Crimean War reveals her demonstration of modern disaster nursing competencies when one considers the knowledge and resources of the time. A competent practitioner, Nightingale understood the basic concepts of environmental and public health now widely recognized as the bedrock of disaster nursing. One of Nightingale’s central themes was the importance of nursing’s role in the management of the patient environment.Reference Nightingale 4 She began her Notes on Nursing Reference Nightingale 4 by stating that the incidence of disease is related to “...the want of fresh air, or of light, or of warmth, or of quiet or of cleanliness” (p 5). All of these factors are viewed as being within the purview of nursing. Nightingale also provided an example of the importance of civic responsibility in time of war, disease, and disaster. Indeed, by her definition, “a nurse means any person in charge of the personal health of another.”Reference Nightingale 4 Nightingale demonstrated skills in triage, information management, procurement of supplies, and equipment. Over the past 150 years, nursing has evolved considerably, experiencing impressive achievements in establishing a scientific foundation for evidence-based practice, broadening its scope into advanced practice and specialty care settings, and expanding the nurse’s role in disaster preparedness and response.

While Clara Barton was not trained formally as a nurse, she is often cited as a nurse and in 1881 founded the American chapter of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent. 5 Barton provided nursing care to hundreds of injured soldiers during the height of the Civil War and clearly demonstrated a solid understanding of risk communication and psychosocial first aid. Barton’s organizational abilities, and her scientific approach to nursing, greatly impressed the Union leaders. By 1864, she was running Union hospitals in Virginia and North Carolina, sometimes working under fire.

Retrospective review of the nurses’ role in civil defense and disaster response provides greater understanding of today’s need for nurses’ involvement in disaster preparedness and response. During World War I, nurses from the US Army Corps were stationed in Europe before the troops were. Under Civil Defense plans of World War II, nurses were expected to assume an expanded clinical role, performing health care services not allowed during peacetime. In the 1950s, in their expanded role under Civil Defense, nurses became leaders, directing teams of laypersons volunteering in the medical mission. It was the nurses’ responsibility to redirect and evacuate the less critical patients to make room for incoming casualties by freeing bed space and grouping patients within the treatment units according to nursing needs and injury severity to make best use of personnel and supplies. Recognizing changes and complications in patients’ conditions and deciding on the most judicious use of scare resources, the nurse could do the greatest good for the greatest number of people, the basic principle of triage.Reference Poole 6

UNIQUE CHALLENGES OF DISASTER NURSING

Effects of climate change and weather patterns, volatility in both the national and international political arenas, and emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases have created a renewed awareness of the need to prepare for all types of disasters and have heightened the importance of identifying nurse leaders in disaster and public health emergency management. Nurses play an integral role in meeting the National Preparedness Goal, a part of the National Preparedness System that establishes “a secure and resilient nation with the capabilities required across the whole community to prevent, protect against and mitigate, respond to and recover from the threats and hazards that pose the greatest risk.“ 7 Nurses will certainly play an integral role in achieving the Global Health Security Agenda. 8 Nursing practice is an important thread throughout the national planning framework and the disaster life cycle of preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery. As disasters increase in frequency and response becomes more intentional, nurses will have a significant role to play in the field of research, incident management, and direct care. Current studies show, however, that in general, nurses report inadequate confidence and knowledge levels for responding appropriately to disasters, which suggests a need for increased training opportunities that are encouraged and supported by knowledgeable leaders.Reference Baack and Alfred 9

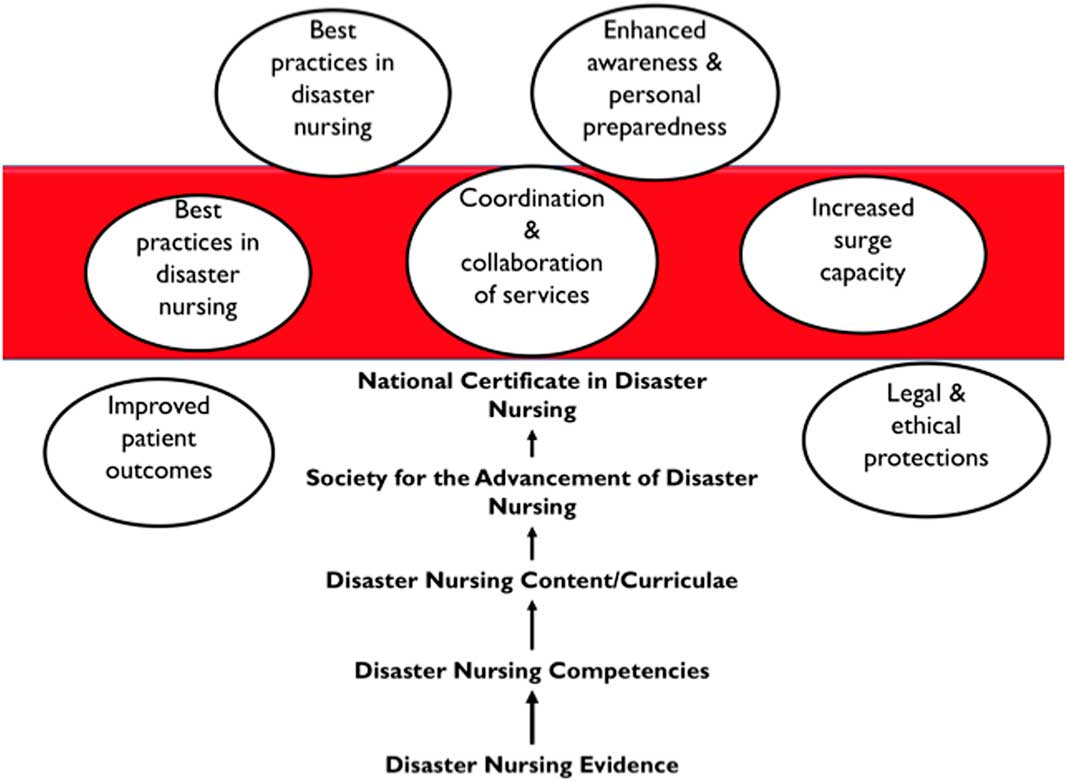

In the face of a worst-case scenario such as a nuclear disaster or pandemic, US nurses do not, as a rule, possess the specific knowledge, skills, and abilities that they will need to respond in a timely and appropriate manner. Large-scale disasters such as Hurricanes Katrina (2005) and Sandy (2012) revealed the rapid expansion of the nurse’s scope of practice to meet the reality of the health care demands, regardless of the nurse’s education or skill set. This sudden expansion of nursing’s role illustrates the need for a professional organization for the advancement of disaster nursing with membership of disaster nursing specialists who possess education and training in the field. The time to determine who has the necessary specialty knowledge and skills to respond with an extended and well-defined scope of practice is not during the disaster. It should be determined by the profession in advance through competency-based education and certification (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Pathway to Disaster Nursing Specialists Through Competency-based Education and Certification. Figure copyright Tener Goodwin Veenema, Tener Consulting Group LLC. Reprinted with permission.

During a time of major crisis, all US nurses will be needed to provide care to their patients, their neighbors, their community, and their nation—it is expected that they will do their civic and professional duty. While it is unrealistic to expect that all nurses will become disaster nurses, it is both realistic and pragmatic to plan for a cadre of nurse specialists in disaster response and public health emergency preparedness who can serve as nursing leaders and managers for disaster preparedness (planning), response, and recovery efforts. The profession needs nurses who understand an all-hazards approach to planning and preparedness and the fundamental concepts and principles of health systems management during large-scale disaster events and possess expertise in disaster nursing across the entire spectrum of care. These nurses will be the leaders within the field and facilitate the planning, supervision, and coordination of disaster nursing care. Disaster and public health emergency response is every health care provider’s “second specialty.” Generalist nurses responding to disaster events would benefit by a clearly defined scope of practice, standards for care, and guidance from those who are experts in disaster nursing. Because of the extent of the clinical challenges encountered in disaster situations and the potentially significant contributions nurses make to advancing population-based outcomes, the establishment of a professional organization to advance disaster nursing is essential.

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF DISASTER NURSING

Clara Barton once famously said, “I may be compelled to face danger, but never fear it, and while our soldiers can stand and fight, I can stand and feed and nurse them.” 5 In an effort to ensure we are adequately prepared to “nurse them,” it is time to firmly and finally establish the necessity of specialized education in disaster nursing and to ensure that subject matter experts are leading the way in the development of scope, standards, ethics, and values. Currently, a national effort exists to establish the American Society for the Advancement of Disaster Nursing. The effort was initiated by the Veterans Emergency Management Evaluation Center (VEMEC) and a group of subject matter experts in disaster nursing in the fall of 2014. Originally intended to strengthen nurse readiness within the Veterans Administration (VA), a groundswell of support has propelled the continuation of the project and has engendered support from nurses across the country. Input from nursing professionals who have been deployed or who have had actual disaster experience has been solicited throughout the project. In addition to those nurses within the VA, US Public Health Service, and current and past policy officers from the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), nurses from the American Red Cross and other National Voluntary Organizations in Disaster (NVOADs), the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA), the Association for Public Health Nurses (APHN), and other relevant nursing subspecialty organizations contributed to the formulation of a broader perspective of disaster nursing practice and the need to organize for response. “The aims of the project were to develop a vision for the future of disaster nursing, identify barriers and facilitators to achieving the vision, and develop recommendations for nursing practice, education, policy, and research.”Reference Veenema, Griffin and Gable 10 More information can be found at http://societyfortheadvancementofdisasternursing.org.

The mission of the society is envisioned to go beyond the role of education and information. The goals are to spur disaster-nursing-related research and policy that leads to publication and changes practice, subject matter expertise that guides educational design and raises public awareness and preparedness, and recognition of contributions to the field that encourage all to respond. The work currently being conducted to establish a society also recognizes and respects the interprofessional nature of disaster response and the critical importance of communication, collaboration, and coordination with physicians and other members in disaster response. Nurses work side by side with physicians and other members of the team during all phases and across all actions of a disaster. Nursing has a role in disaster preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery care coordination and in efforts aimed at strengthening community resiliency. The establishment of a professional society for disaster nursing would provide both leadership and a bridge between health care providers and their professional organizations committed to response. We anticipate improved channels for communication and the establishment of multiple new projects and partnerships leading to greater clarity in nursing’s role in improving population-based outcomes. The new society would welcome opportunities to support interprofessional disaster practice, policy, and research initiatives at the federal, state, and local levels.

The new society would also better align the multiple perspectives needed for clinical disaster response between emergency, trauma, and critical care nurses and public health and community nurses. Disasters are not solely limited to intensive critical care and the mobilization of Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (DMATs). When a disaster occurs, much of a nurse’s time spent in the field may be devoted to linking victims with health and human services that have been disrupted as a result of the event. The society would work to identify distinctions between the various roles of different types of nurses and work to define and coordinate the clinical care with the community and public health aspects of disaster response.

Additionally, establishing a society for disaster nursing will give the profession a stronger voice to agencies such as ASPR and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The new society can work with existing groups (eg, the Society for Disaster Medicine and Public Health [SDMPH] and the World Association for Disaster Medicine [WADEM]) to advocate and influence policy decisions that will capitalize upon nursing’s full potential to improve health outcomes in individuals, families, and communities affected by disaster.

ESTABLISHING A FRAMEWORK FOR DISASTER NURSING SPECIALTY DESIGNATION: ANA SCOPE AND STANDARDS OF PRACTICE

In Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, “scope of practice” is defined by the who, what, where, when, why, and how of nursing practice, including advanced practice nursing. 11 A disaster or public health emergency has the potential to overwhelm daily capacity and capabilities. Although no emergency changes the basic standards of practice, code of ethics, competence, or values of the profession, 12 expanding the scope of nursing practice has been proposed as a solution to situations where available resources are overwhelmed by a surge of patients.Reference Veenema, Griffin and Gable 10 , Reference Courtney 13 , 14

Becoming recognized as a specialty within nursing means meeting certain criteria for approval based on “a definition of the nursing specialty that discusses the parameters for the specialty nursing practice, practice characteristics, and the phenomena of concern unique to the specialty practice.“ 15 Disaster nursing as a specialty practice requires a similar foundational framework as other ANA-recognized nursing specialties within a model of professional practice regulation to ensure outcomes that are reflective of safe, quality, evidence-based practice (Figure 3). This framework builds upon the exiting evidence for the field, consensus-based competencies for clinicians and nurse administrators, and national guidelines for advanced education, training, and, ultimately, certification. The principles that underlie specialty practice in disaster nursing are as follows:

-

1. Disaster nursing roles are consistent with the scope of nursing practice and are articulated specifically in those standards and scope. 11

-

2. The components of the nursing process align with the National Planning Framework phases of preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery. 15 , 16

-

3. Competencies provide a framework for defining disaster nursing roles and standards of practice across the disaster life cycle.Reference Gebbie 17 , 18

-

4. Disaster nursing bring leadership, scientific rigor, policy, planning, and practice expertise to preparedness, response, and recovery from disasters, mass casualty events, and public health emergencies.

-

5. A professional disaster nursing organization provides national leadership to serve as a resource, support advocacy, establish and maintain of standards, and set requirements for future credentialing (Figure 2).

Figure 3 Model of Professional Nursing Practice Regulation. Outcome=safe, quality, and evidence-based nursing practice. Source: © 2008 American Nurses Association. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

SUMMARY

We propose that efforts begin in earnest to pursue professionalism and specialty designation specific for disaster nursing. Our recommendations would result in a framework grounded in evidence that would include:

-

1. Establishment of the American Society for the Advancement of Disaster Nursing to focus on threats and disaster nursing needs specific for our nation.

-

2. Establishment of Scope of Practice and Standards for Care during disasters.

-

3. Resolution of the disaster competency debate and the articulation of minimum and advanced competencies required for the specialty. Such would delineate nursing competencies that span public health, human services, community-based and acute care services for disaster planning, prevention, response, and recovery efforts where nursing can make a contribution.

-

4. Establishment of a mechanism for credentialing and professional oversight, which would include levels of education required as well as competency verification through either an exam or portfolio.

CONCLUSION

The roots of modern-day professional nursing emanate from the disaster nursing efforts of Florence Nightingale during the Crimean War. Generations later, disaster nursing represents a complex arena in which the intersection of competence, scope of practice, regulation, and clinical guidelines continues to evolve. These policy issues must be addressed in a systematic, organized, and evidence-based manner. Our credibility and our potential contribution to large-scale disaster response lies in our ability to clearly articulate and advance professionalism within disaster nursing. We see a future where disaster nursing specialists will work collaboratively to contribute to disaster planning, preparedness, response, and recovery at the federal, state, and local levels. Disaster nursing specialists will set the standards for disaster nursing that are based on research and the best evidence, influence policy, and contribute to overall disaster preparedness for our nation and communities. The time has arrived to establish an independent professional organization for the advancement of disaster nursing, collectively define a disaster nursing scope of practice, establish standards for care, and identify best practices. This will set the stage to pursue specialty designation within the field.