A natural disaster is an unpredictable, unexpected, and uncontrollable event occurring in nature and typically results in a sense of collective stress and social disruption, with the extent of its impact spanning social, health, and economic realms.Reference Tremblay, Blanchard and Pelletier 1 Floods are the most common type of natural disaster and tend to have the highest cost burden.Reference Fernandez, Black and Jones 2 Beyond their physical impacts, natural disasters can also lead to a wide range of mental health issues, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety.Reference Goldmann and Galea 3 , Reference Mason, Andrews and Upton 4 However, natural disasters can also have strengthening outcomes, such as an increased sense of community, because people share an experience and work together on recovery efforts after a major event.Reference Kaniasty and Norris 5 , Reference Patterson, Weil and Patel 6

The risk factors for negative mental health outcomes following natural disasters have been previously reviewed.Reference Fernandez, Black and Jones 2 , Reference Goldmann and Galea 3 , Reference Norris, Friedman and Watson 7 , Reference Stanke, Murray and Amlôt 8 Common demographic pre-disaster risk factors for poor mental health outcomes include being of a younger age, female gender, lower socio-economic status, and of a minority ethnic status.Reference Goldmann and Galea 3 , Reference Norris, Friedman and Watson 7 , Reference Stanke, Murray and Amlôt 8 Psychosocial risk factors include previous mental health problems and lower social support.Reference Goldmann and Galea 3 , Reference Kaniasty 9 Disaster-related risk factors include level of exposure (level of damage to personal property or injury), previous exposure to natural disasters, and loss of services or employment.Reference Fernandez, Black and Jones 2 , Reference Mason, Andrews and Upton 4 , Reference Paranjothy, Gallacher and Amlôt 10 - Reference Alderman, Turner and Tong 12

Reports of the impact of flooding events vary in terms of who was sampled and the outcomes assessed. A study on the effect of the 2011 Brisbane floods in Australia found that, overall, 22% of flood-impacted respondents had elevated levels of psychological distress, and that those who were directly impacted by the flood (damage to property or possessions) had higher odds of elevated distress (OR 1.9; 95% CI: 1.1, 3.5).Reference Alderman, Turner and Tong 12 A study of communities affected by flooding in the United Kingdom in 2007 found elevated levels of anxiety (48%) and depressive symptoms (43%) among those with damage to their homes.Reference Paranjothy, Gallacher and Amlôt 10 A study on the impact of Hurricane Ike, which caused major flooding in Texas in 2008, found only 5% of those who sustained damages to their homes to have probable depression.Reference Tracy, Norris and Galea 11

Previous reviews have identified broad limitations in the literature regarding disasters and mental health, specifically regarding the cross-sectional nature of the majority of data.Reference Goldmann and Galea 3 , Reference North 13 Cross-sectional data limit assessment of a mental health sequela because it is difficult to determine whether the natural disaster triggered the mental health problem, increased the severity of a pre-existing condition, or was unrelated.Reference North 13 Studies that exclusively measure poor mental health prevalence after a disaster cannot conclude that the disaster caused the conditions, as they may simply reflect a pre-disaster burden.Reference Goldmann and Galea 3 Adequate control groups are difficult to identify, and they may be systematically different from exposed groups in other ways, which will result in inappropriate comparisons. Studies that attempt to retrospectively assess mental health before the disaster are subject to recall bias, primarily due to underreporting of previous conditions.Reference Goldmann and Galea 3 , Reference Moffitt, Caspi and Taylor 14

The evidence on what contributes to the strengthening effects of natural disasters, such as community cohesion, is mixed. Community cohesion refers to a sense of trust, honesty, and sincerity toward others in their community or neighborhood.Reference Kaniasty 9 Kaniasty’s research after flooding in Poland suggested that those who received support after flooding felt a greater sense of community.Reference Kaniasty 9 Research in the United Kingdom suggested that greater exposure to a disaster (more physical or material harm) was associated with more community cohesion, but that this relationship is inversed at very high levels of exposure.Reference Chang 15 Initial community cohesion after a natural disaster may also deteriorate over time, as people become dissatisfied with the help received.Reference Kaniasty and Norris 5 , Reference Kaniasty 9 , Reference Sweet 16

Over 3 days in June 2013, torrential rains and flooding in southern Alberta led to the evacuation of over 100,000 residents in the region. Major flooding in Calgary (pop. 1.2 million), a center for energy and finance in Western Canada and the largest city affected by the disaster, caused the closure of the central business district for over a week and severe disruptions to schools and utility services. In Calgary, overland flooding affected the downtown core communities as well as several higher- and lower-income residential communities along the river. 17 The damage from the flood in the entire region was estimated at over 6 billion Canadian dollars, making it the second most expensive natural disaster in Canadian history. 18

To date, there is little in the peer-reviewed literature examining the public health impacts of this disaster, with the exception of one study that documented increased rates of prescriptions for anti-anxiety medication and sleep aids after the flood.Reference Sahni, Scott and Beliveau 19 The current study examines both negative and strengthening outcomes of this natural disaster among mothers of young children living in Calgary. Using data from an ongoing longitudinal cohort study that began in 2008, the current analysis uses prospectively collected data on mental health to assess mental health and community cohesion after the 2013 flood. Specifically, we address the risk and protective factors associated with 4 outcomes: post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, and community cohesion.

Methods

Study Design

The All Our Families (AOF) study (previously All Our Babies) is a longitudinal prospective cohort study initiated in 2008 in Calgary, Alberta. Women completed questionnaires twice during pregnancy and at 4, 12, 24, 36, and 60 months postpartum with data collection for the 8-year point underway. The study has a 77% longitudinal retention rate and the questionnaires address lifestyle, behavior, resource utilization, child development, parenting, maternal physical and mental health, and early childhood experiences. Further information on the AOF study is described elsewhere.Reference McDonald, Lyon and Benzies 20

At 5 months after the flood in 2013, AOF participants who had previously agreed to participate in further research were sent a questionnaire to better understand their flood experience as well as damages sustained, help or aid provided and received, post-traumatic stress, maternal psychological distress, and social cohesion. The questionnaire was constructed based on the disaster impact literature, consultations with experts in the field, and on information from the 2011 Alberta Slave Lake Fires and the 1998 Quebec Ice Storm. To ease participant burden, shorter validated versions of mental health scales were used in the post-flood questionnaire. The overall response rate to the flood impact questionnaire was 67% (1913/2861). The current sample includes the 923 participants who completed both the flood impact questionnaire and the 36-month questionnaire before the flood.

Measures

All outcome measures as well as flood-specific questions are from the flood questionnaire. All other pre-flood variables are from previous questionnaires with baseline mental health data specifically from the All Our Families 36-month questionnaire, which some participants completed up to 18 months preceding the flood.

Post-flood outcome constructs included post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, and community cohesion. Post-traumatic stress was measured using the Impact of Events Scale-Revised.Reference Horowitz, Wilner and Alvarez 21 , Reference Weiss 22 For this study, a cut-off point was set at the 90th percentile to indicate high levels of post-traumatic stress. Depressive symptoms after the flood were assessed using the 12-item short version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies - Depression Scale (CES-D). A score of 12 or higher indicates somewhat-elevated to very-elevated depressive symptoms.Reference Poulin, Hand and Boudreau 23 , Reference Kozyrskyj, Letourneau and Kang 24 Anxiety symptoms after the flood were measured using the 6-item short version of the Spielberger State Anxiety Scale (SSA), with a cut-off point at 1 SD above the mean to indicate clinically relevant symptoms.Reference Marteau and Bekker 25 Four items from the Perceived Post-Disaster Community Cohesion Scale (PDCC) were used to measure beliefs and perceptions on community cohesion following a disaster.Reference Kaniasty 9 Respondents were asked about the sense of solidarity and unity after the flood compared with that before the flood (people are nicer toward each other than before the disaster; people are more sincere, honest and open toward each other; people in this community are more integrated and united; people have a stronger sense that we are all part of a community). Reliability for the 4 items in this sample was high (Cronbach’s α: 0.86). Higher scores indicate a greater sense of post-disaster community cohesion in the longer term, and a score of 1 SD above the mean was used as a cut-off point to indicate high community cohesion.

As part of the flood questionnaire, participants were also asked to indicate any damages sustained to personal property (dwelling, vehicle, infrastructure, and possessions) and community services (library, school, neighborhood, etc.). Participants also provided information on the provision of aid to family, friends, and the wider community.

Pre-flood variables included socio-demographic factors such as age, education, income, ethnicity, and immigrant status. Baseline psychosocial variables included mental health (depression, anxiety), social support, and partner relationship. Depressive symptoms before the flood were assessed using the twenty item CES-D with a score of 16 or more indicating clinically significant levels of distress.Reference Radloff 26 Anxiety symptoms before the flood were assessed using the Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory (SSAI), with a cut-off score of 40 for clinically relevant symptoms.Reference Speilberger, Gorsuch and Lushene 27 , Reference Knight, Waal‐Manning and Spears 28 Social support before the flood was assessed using the National Longitudinal Study of Children and Youth social support scale. 29 This scale measures perceived social support with a series of questions about whom the respondent can rely upon for guidance, about the assurance that others will provide help, and about attachment. A cut-off point at 1 SD below the mean was used to indicate low social support.Reference McDonald, Kehler and Tough 30

Using postal-code data, participants living in a community that had been identified as being at a high risk for flooding by the city of Calgary in 2012 were classified as living in an at-risk community.Reference Calgary 31

Analysis

Participants who lived in Calgary, had agreed to additional research, and had completed the 36-month questionnaire before completing the flood-impact questionnaire were eligible for inclusion in this study (N=923). Descriptive statistical analyses were carried out for all outcomes and covariates of interest. For each of the 4 outcomes, a multivariable logistic regression model was built using a manual backward elimination procedure to determine the relevant predictors of each outcome and potential confounders.Reference Kleinbaum and Nizam 32 Variables considered for inclusion in all 4 models were all demographic factors, flood-related factors, and factors related to the provision of help. For the first 3 models (predictors of post-flood stress, depressive symptoms, and anxiety), we considered psychosocial factors before the flood. This allows for temporal ordering of mental health variables measured before the flood, and for assessing their association with mental health after the flood. For the fourth model (predictors of community cohesion), we considered psychological symptoms after the flood because a person’s current level of mental health might impact their sense of community. Modeling began by including all candidate variables and eliminating them one-by-one, beginning with those with the highest P-value based on the Wald test. Covariates were retained in the model if they had a significant association with the outcome of interest (P≤0.05), or if they changed the point estimate of other covariates by over 10% (indicating confounding). The final parsimonious model was compared with the initial fully adjusted model to ensure the robustness of the estimates and confirm that all confounders had been included. Possible effect modification by baseline mental health and geographical location (living in a flood-risk community) was examined in stratified analysis. All analyses were conducted in STATA v.13. 33 Using postal-code data from participants, AOF families were plotted on the map of Calgary using ARC GIS software. 34

Results

Descriptive statistics for the sample are available in Table 1. The mean age of the women in our sample was 34 years (SD 4.4), and ~80% had at least post-secondary education, had a higher income (>$80K), were Caucasian, and were born in Canada. Of the participants, 27% had previously been exposed to a natural disaster, but only 8% lived in a community listed as being at a high risk for flooding. Baseline depressive and anxiety symptoms were 13% and 15%, respectively. A total of 11% of respondents indicated elevated levels of post-traumatic stress. Only 5% of respondents indicated depressive symptoms after the flood, and 12% had high levels of anxiety symptoms after the flood. In all, 17% of participants indicated that they had a high sense of community cohesion after the flood.

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics

Abbreviations: CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies - Depression Scale; NLSCY, National Longitudinal Study of Children and Youth PDCC, Perceived Post-Disaster Community Cohesion Scale; SSA, Spielberger State Anxiety Scale; SSAI, Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory.

a Some variation in denominator due to missing data.

Of the participants, 17% (n=157) indicated suffering any loss or damage to personal property, to community services, or to the neighborhood. The losses and damages reported were primarily to community property (library, school, etc.) (n=141) with only 21% (n=33) of those who reported any loss indicating that this was personal property loss (dwelling, vehicle, or possessions).

Almost two-thirds (65%, n=603) of respondents provided flood relief or support and participated in dispensing aid, with some providing multiple types of support to multiple groups. Among those who provided support, the majority provided support to community organizations and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) (71%, n=425), followed by support to friends and neighbors (51%, n=311), family (28%, n=166), or their employer (14%, n=82). Of those who provided aid to families, the majority did so in the form of emotional and practical aid (66%, n=110 and 59%, n=97, respectively). Of those who provided aid to community organizations and NGOs, the majority did so in the form of supplying goods (72%, n=304), followed by financial contributions (38%, n=161).

Risk and protective factors for post-flood outcomes:

Multivariable logistic regression for the risk and protective factors associated with negative mental health outcomes (post-traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety) are presented in Table 2. All covariates that were significant predictors or confounders for each of the outcomes are presented, with statistically significant factors indicated in bold. For the first outcome of post-traumatic stress, having a higher income, being born in Canada, and being Caucasian reduced the risk for high levels of post-traumatic stress. Living in a flood-risk community as well as having previous symptoms of anxiety were risk factors (AOR: 3.90; 95% CI: 1.69, 9.01 and 2.49; 95% CI: 1.17, 5.26, respectively) for post-traumatic stress.

Table 2 Factors Associated with Negative Mental Health Outcomes

Abbreviations: CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies - Depression Scale; NLSCY SSS, National Longitudinal Study of Children and Youth social support scale; SSAI, Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory.

For the second outcome of increased risk for depressive symptoms, living in a flood-risk community, having anxiety symptoms before the flood, and having low levels of social support were all associated with an increased risk for depressive symptoms after the flood (Table 2), even when controlling for baseline depressive symptoms. For the third outcome of anxiety symptoms, having anxiety symptoms at baseline was associated with increased odds of experiencing anxiety symptoms after the flood (AOR 7.07; 95% CI: 4.36, 11.45). Previous exposure to a natural disaster was also associated with increased odds of anxiety after the flood (AOR 1.63; 95% CI: 1.01, 2.67).

Table 3 shows the results of the fourth logistic regression, risk and protective factors associated with high community cohesion. Elevated post-traumatic stress, experiencing damage to personal property, or participating in community services and providing help to others were associated with increased odds of reporting a high levels of community cohesion after the flood.

Table 3 Factors Associated with High Levels of Community Cohesion

Discussion

This study assessed the mental health and community cohesion outcomes of participants in a longitudinal pregnancy cohort 5 months after major flooding in Calgary, leading to 3 broad findings.

First, most respondents in our sample did not experience major psychological distress 5 months after the flood. This may be reflective of the different type of sample used in our study compared with traditional post-disaster samples.Reference Goldmann and Galea 3 Traditional post-disaster samples tend to be concentrated in highly affected zones, who experience the most visible impact. Our sample was comprised of a much more diverse population, living across Calgary, with only 8% living in flood-risk communities and 17% experiencing loss to property or services. Very few studies of this type measure the impact of a disaster within an existing cohort, but one study in New Zealand on the impact of an earthquake in an existing cohort found similar low levels of major psychological distress.Reference Fergusson and Boden 35

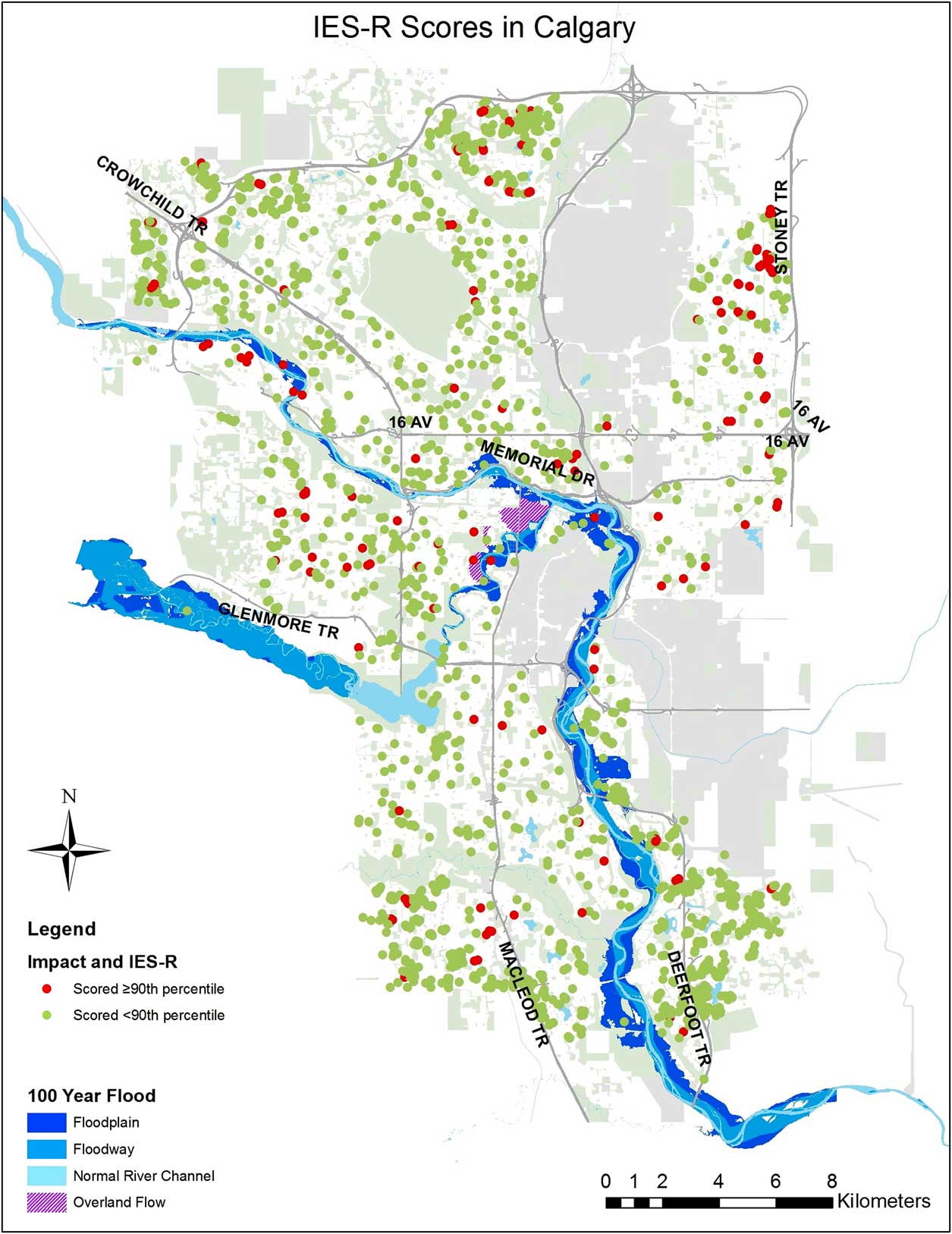

Second, a higher level of exposure to the flood (living in a community at a risk for flooding, or experiencing loss or damage to property or services) was not the only factor that was associated with high levels of post-traumatic stress or other mental health outcomes after the flood. The map of families (Figure 1) shows that many families with high levels of post-traumatic stress did not reside near a high-risk flood area. This is consistent with the results of the multivariable analysis, which indicate that demographic factors as well as pre-existing high levels of anxiety are associated with increased odds of experiencing post-traumatic stress, regardless of whether families lived in a flood-risk community. The vulnerability of people with pre-existing mental health problems to natural disasters is well documented in the literature using retrospective assessments of mental health.Reference Goldmann and Galea 3 , Reference Mason, Andrews and Upton 4 This study adds to this evidence with prospectively collected data. The results also suggest that vulnerability to the impact of a natural disaster may not always be obvious, and that families with no tangible damage from a disaster may also suffer psychological effects, which is consistent with literature suggesting that disasters affect a broader community beyond those directly impacted.Reference Kaniasty 9 , Reference Bonanno, Brewin and Kaniasty 36

Figure 1 Shows the All Our Families Who Scored High Levels of Post-Traumatic Stress in Red, and Families Scoring Low Levels in Green. Abbreviation: IES-R, Impact of Events Scale-Revised.

Finally, our results suggest that in addition to the negative impacts of natural disasters, there may be supportive impacts as well. In our study, those with high levels of post-traumatic stress were also more than twice as likely to report high levels of community cohesion. Increased community cohesion after natural disasters has also been reported in Poland, the United States, the United Kingdom, and in New Zealand.Reference Kaniasty 9 , Reference Chang 15 , Reference Sweet 16 , Reference Fergusson, Boden and Horwood 37 In an examination of community cohesion in Carlisle, after major flooding, ChangReference Chang 15 found that the level of community cohesion varied by severity of exposure to the flood. Our analysis lends support to this finding, as those who had suffered a loss to personal or community property also felt a higher degree of community cohesion. Previous literature has focused on how receiving aid after a disaster increases people’s sense of community cohesion.Reference Kaniasty 9 , Reference Chang 15 Our study adds to this finding by showing that the provision of aid—that is, the act of helping others—also increased people’s sense of community. This is not unexpected, and it helps build on the theory that communities can be resilient to natural disasters through the provision of aid and services to disaster victims via existing social networks.Reference Norris, Stevens and Pfefferbaum 38 Norris et alReference Norris, Stevens and Pfefferbaum 38 suggest that community resilience is important not only in the recovery from a disaster, but also in terms of preparing for future events. Community and civic leaders can use the language of community resilience to mobilize support in the aftermath of a disaster. For example, encouraging people to help others not only because it benefits the recipients of aid but also because it benefits those giving help by strengthening community cohesion for current and future events.

Strengths and Limitations

The response rate to the flood survey was 67% and respondents were more likely to be married, have a higher income, have a higher level of education, be born in Canada, and be Caucasian compared with non-respondents. This is not uncommon in longitudinal cohorts; however, it may affect the generalizability of our study, and the findings may not be applicable to more vulnerable women. All participants in this study were women, and mothers of young children, and, consequently, findings may not apply to all populations.

Results regarding risk factors for depression should be interpreted with caution as only 5% of participants screened positive for depressive symptoms. Estimates of the prevalence of depression and its association with natural disasters are variable and generally do not control for baseline depressive symptoms.Reference Fernandez, Black and Jones 2 , Reference Goldmann and Galea 3 A study of major depression after Hurricane Ike reported a similar prevalence (4.9%), whereas a study in England after the 2007 flooding measured over 13% prevalence of depression, with both samples including directly and indirectly affected individuals.Reference Paranjothy, Gallacher and Amlôt 10 , Reference Tracy, Norris and Galea 11 In our sample, 15% of respondents had depressive symptoms before the flood and only 5% did afterwards. This decrease in prevalence is unexpected and may indicate a measurement error associated with the shorter scale used in the post-flood questionnaire. It is also likely an underestimate of the prevalence of depressive symptoms. Finally, all measures were self-reported, which can bias the results.Reference Radloff 26

The major strength of this study is the availability of prospectively collected mental health data allowing us to consider baseline mental health in assessing post-disaster psychological distress and its ability to examine factors associated with strengthening outcomes such as community cohesion that have implications for post-disaster recovery.

This study captures a broader sample than the traditional post-disaster research that focuses on those that are in visibly or tangibly affected zones. Our study shows that being in the immediate proximity of a natural disaster, in this case the river, was not the only factor, and sometimes not the most influential factor, for mental health outcomes. These findings suggest that disasters affect the broader community in both negative and supportive ways.

Conclusions

Our study revealed generally low levels of post-traumatic stress after the 2013 Southern Alberta flood among mothers with young children in Calgary. Our sample included women who were well-educated, had higher incomes, were Caucasian, were born in Canada, and had access to a publically funded health-care system. In this study, vulnerability to mental health challenges after a natural disaster was associated with both the level of exposure to the disaster and pre-existing mental health conditions. Finally, greater exposure to the disaster and participating in the provision of aid were both associated with an increased sense of community cohesion after the flood. First responders, civic leaders, and mental health professionals should recognize that numerous factors influence vulnerability to catastrophic events, with pre-existing mental health challenges playing a significant role. Yet, considerable benefits can be achieved by engaging in help or aid activities following a natural disaster.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the families who participated in the All Our Families study. They also thank Pablo Pinapoujol for his assistance with mapping.

Funding

Funding for the All Our Families study and the flood follow-up was provided by Alberta Health Services, Alberta Innovates Health Solutions, the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation, and the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute. Erin Hetherington has scholarship support from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research Vanier Scholarship, Alberta Innovates Health Solutions Studentship, and the University of Calgary Eyes High Doctoral Recruitment Scholarship. Suzanne Tough receives a salary award from Alberta Innovates Health Solutions.