Disasters are associated with a continuum of mental health consequences. Although emergency medical responders exhibit considerable resilience, 10%-20% may also develop single or comorbid psychiatric disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression.Reference Goldmann and Galea 1 For example, 11.7% of emergency medical responders responding to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks were found to have clinical PTSD 3 years after the event.Reference Berninger, Webber and Cohen 2 Natural disasters have also demonstrated psychological risk in emergency responders. One month after the 1999 Chi-Chi Earthquake in Taiwan, 19.8% of professional responders and 31.8% of volunteer responders were found to have provisional clinical levels of PTSD.Reference Guo, Chen and Lu 3 Although PTSD has been identified in emergency medical responders, the process of identifying those at risk early in the response period has not been studied as extensively or used to develop timely early evidence-based intervention strategies. It is important to counteract the risk from response in emergency medical responders to not only protect the mental health of these individuals and their families, but to also preserve their ability to carry out their life saving missions.

There is now evidence regarding the salience of “dose of exposure” to predict psychological risk in disaster victims. For example, the Psychological Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (PsySTART)Reference Schreiber, Pithia and Kusel 4 mental health triage system has demonstrated a predictive relationship for clinical PTSD and depression in victims of a disaster. This tool, initially designed for disaster victims, relies not on symptoms but on discrete, observable doses of exposure, traumatic loss of loved ones, and other discernible disaster adversities such as displacement from home. The PsySTART mental health triage system for victims is the first step of a “stepped care” approach to matching those at risk with secondary assessment and access to acute evidence-based interventions that have shown to reduce or prevent PTSD when applied within 30 days after the event.Reference Shalev, Ankri and Israeli-Shalev 5 A comparable approach specifically focused on emergency medical responders has not yet been reported. With this in mind, a cohort of deployed emergency medical responders involved in Typhoon Haiyan completed a novel PsySTART responder version to assess the ability of PsySTART risk factors to predict levels of PTSD and/or depression in a responder population. The PsySTART responder version utilized in this study includes candidate risk factors derived from the PsySTART mental health triage victim version as well as emergency medical role-specific exposure factors hypothesized to be predictive based on previous pilot testing in a simulated large-scale mass casualty disaster drill in which emergency medical responders rated both the frequency and perceived stressfulness of each candidate risk factor.Reference Schreiber, Pithia and Kusel 4

In November 2013, Typhoon Haiyan made landfall in the Philippine province of Eastern Samar, and subsequently made its path across Leyte, Northern Cebu, Capiz, Aklan, Northern Iloilo, and Northern Palawan. The official death toll reached 6069 according to the Philippine National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council and affected nearly 16 million people. There was a significant medical response, which heavily involved emergency medical responders, including nurses, physicians, and emergency medical technicians (EMTs). These response teams moved in from other areas of the country to augment the local response.

METHODS

A convenience sample of 75 emergency medical responders were recruited 60 days after the event by the National Institute of Health (NIH) of the Philippines as part of a comprehensive worker follow-up strategy. Of the 75 eligible responders, 46 (response rate=61.3%) completed consent forms and all measures including the PsySTART responder version, PTSD Checklist (PCL-5), and Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8) ~4 months after Typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines. Responders who completed the survey were nurses (n=22), EMTs (n=8), physicians (n=7), medical students (n=4), and other health professions (n=5). The 46 respondents cared for 27,523 patients during their 60-day period in the Philippines. Caring for trauma patients and treating communicable diseases were the 2 most common tasks performed by the cohort with primary casualties (drowning, hypothermia, failed resuscitation) outnumbering secondary casualties (diabetes, hypertension). This is a similar context to other reported medical responses during Typhoon Haiyan.Reference Brolin, Hawajri and von Schreeb 6

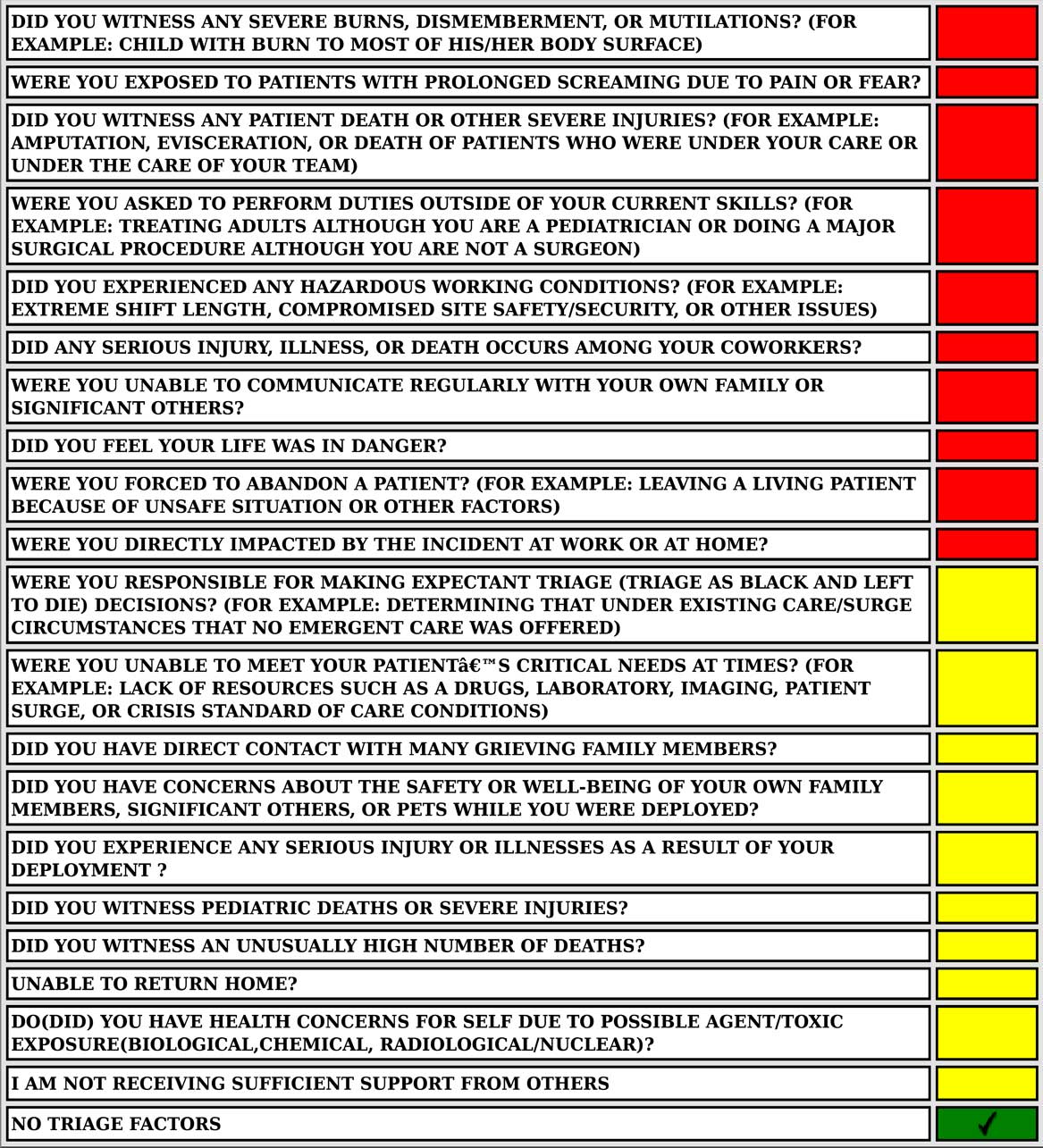

The PsySTART responder version assessed exposure-based risk factors specific to the responder medical response role as well as evidence-based risk factors adapted from the PsySTART mental health triage system for victims. PsySTART items for the responder version are displayed in Figure 1. The PCL-5 was utilized to measure PTSD.Reference Weathers, Litz, Keane, Palmieri, Marx and Schnurr 7 Scores created from this checklist range from 20 to 100. A score of ≥38 is the threshold for a provisional diagnosis of PTSD. The PHQ-8 measured depressive symptoms with possible scores ranging from 0 to 24. For the PHQ-8, a score of ≥10 is the threshold for a provisional diagnosis of clinical depression.Reference Kroenke, Strine and Spitzer 8 Individual risk factors and the total number of risk factors were used to predict provisional PTSD and depression diagnoses based on the triage tool threshold scores.

Figure 1 PsySTART Responder Version Triage Form.

RESULTS

Responders indicated positive responses ranging from 0 to 11 for the 14 PsySTART risk factors [median=6 (95% CI 5-8), interquartile range 4-9]. A total of 14 responders (30%,) had PCL-5≥38, indicating PTSD, and 3 (7%) had PHQ≥10, suggesting clinical depression. The number of positive PsySTART risk factors positively correlated with the number of both PCL-5 and PHQ-8 symptoms (Table 1). In addition, the total number of PsySTART risk factors was significantly related to PCL-5 scores ≥38 indicating a provisional clinical PTSD diagnosisReference Weathers, Litz, Keane, Palmieri, Marx and Schnurr 7 (Figure 2). A cut-off point of 6 on PsySTART identified all 14 responders with PCL-5≥38 (sensitivity=100%, 95% CI 81-100%) and 11/32 responders with lower PCL-5 scores (specificity=66%, 95% CI 47-81%). This yielded an area under the receiver operating curve of 0.80, meaning PsySTART ≥6 would correctly classify 80% of pairs of PCL-5≥38 respondents (95% CI 0.68-0.93). Of these, 3 risk factors, “Were you ever asked to perform duties outside of your current skills?,” “Did any serious injury, illness or death occur among your coworkers?,” and “Did you ever feel your life was in danger?,” were independently associated with PCL-5≥38. The sum of these 3 risk factors yielded an area under the receiver operating curve of 0.88 (95% CI 0.79-0.97).

Figure 2 Plot of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5) Scores by PsySTART Positive Items with Regression Line (n=46). The horizontal line shows the threshold for the clinical diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Table 1 Correlation Coefficients with P-values Among 3 Scores Derived from PsySTART, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder-5 (PCL-5) Score, and Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8) Score (n=46).

DISCUSSION

A subset of deployed emergency medical responders in Typhoon Haiyan demonstrated a risk for the development of provisional PTSD diagnoses and subclinical depressive symptoms based on their PHQ-8 and PCL-5 scores. Despite the small number of subjects, the PsySTART Responder version predicted provisional clinical PTSD and subclinical depressive symptoms ~4 months after Typhoon Haiyan deployment. The preliminary data presented here support the continued study of the PsySTART responder version to quickly identify the emergence of risk for clinical PTSD and subclinical depressive symptoms in emergency medical responders working in a catastrophic medical context. It also supports the feasibility of responders to efficiently and effectively use a self-triage tool to identify a risk to themselves and linkage to stepped care. The combination of PsySTART responder risk factors: “Were you ever asked to perform duties outside of your current skills?,” “Did you ever feel your life was in danger?,” and “Did any serious injury, illness or death occur among your coworkers?” were associated with clinical levels of PTSD in health-care responders independent of the total number of positive PsySTART risk factors. These findings are consistent with the literature, which shows direct personal threat of harm to self or coworkers demonstrates a positive predictive relationship with the occurrence of clinical PTSD.Reference Alexander and Klein 9 The finding regarding increased risk associated with performing duties outside of current skills is a novel finding, The potential use of the PsySTART responder version as a component of a comprehensive strategy to manage responder mental health consequences may identify potential risk trajectories early without disclosure of more stigmatizing psychiatric symptoms as is common practice at present. In addition, the potential to build resilience to these risk factors before deployment/response with proper training is another important potential benefit. In the aftermath of response, early identification of any of these areas of concern after exposure can identify those at highest risk for mental health disorders so that early evidence-based acute interventions such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy can be providedReference Castillo, Chee and Nason 10 to reduce the risk for poor outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

First-line medical responders can struggle with PTSD symptoms as they continue to acclimate back into their daily routines at home and further utilize their skills to respond to disasters.Reference Roberts, Kitchiner, Kenardy and Bisson 11 There is emerging evidence that certain early interventions can prevent or reduce the long-term consequences of PTSD.Reference Schreiber, Pithia and Kusel 4 For those that put their lives at risk for others, such as the emergency medical responders described here, the PsySTART responder version can be utilized as a tool to quickly identify those most at risk for PTSD and depression. PsySTART triage enables a “stepped care” approach starting with triage, followed by secondary clinical assessment, and finally providing access to early evidence-based interventions to maximize medical responder resilience. The data presented here suggest that the PsySTART mental health triage system originally designed for victims can be translated to use with emergency medical responders. However, further work to replicate and refine the PsySTART responder version with larger groups of responders across a variety of disaster settings and events is urgently needed.