The Radiation Injury Treatment Network® (RITN) is comprised of medical centers with expertise in the management of bone marrow failure which are preparing to care for patients with acute radiation syndrome following a mass casualty disaster.1 RITN plans to accomplish this throughout each phase of the event. In anticipation of a disaster RITN hospitals have developed treatment guidelines for managing hematologic toxicity among victims of radiation exposure and educate health-care professionals about pertinent aspects of radiation exposure management through training and disaster exercises. During a disaster, RITN hospitals will provide comprehensive evaluation and treatment in an inpatient and outpatient setting for these victims; the RITN control cell helps to coordinate the response through sharing critical information about the disaster between United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (DHHS-ASPR), and RITN hospitals. After a disaster occurs, RITN hospitals will collect patient treatment data for retrospective research through the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplantation Research.1

Many of the casualties with radiation injury from the detonation of an improvised nuclear device will be salvageable but only if they receive the proper outpatient or inpatient care needed to treat their hematologic acute radiation syndrome.Reference DiCarlo, Maher and Hick2 Recognizing this, in 2006 the US National Marrow Donor Program/Be The Match, US Navy Office of Naval Research, and American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (formerly American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation) collaboratively developed RITN (www.ritn.net). RITN is a group of 74 hospitals, academic medical centers, and cancer treatment centers preparing to respond to a large-scale radiological incident that results in casualties with acute radiation syndrome. These centers have expertise in the management of bone marrow failure through the hematology and oncology medical teams who care for patients every day with similar medical complications (ie, neutropenia, graft rejection, graft versus host disease, etc…) that result from the patient’s treatment (deliberate injury to their marrow by means of ionizing radiation or chemo-therapy). These teams are preparing to care for patients with acute radiation syndrome following a radiological mass casualty disaster.Reference Weinstock, Case and Bader3,Reference Murrain-Hill, Coleman and Hick4 RITN physicians, advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, and registered nurses, as part of the US health-care workforce, will be critical to the effectiveness of response to a disaster resulting from the large-scale release of radiation into the environment or nuclear war.Reference Burkle and Dallas5-Reference Hrdina, Coleman and Bogucki8

It is anticipated that during the disaster RITN hospitals will provide comprehensive evaluation and treatment in inpatient and outpatient settings for these victims, and should an event occur in their local area, may need to provide more extensive care, including performing the initial screening for contamination, stabilization of life-threatening conditions due to blast or burns, decontamination, and triage to definitive care.1 Physicians and other advanced practice providers will require knowledge of the medical effects of radiation exposure and contamination and the medical management of such effects. Much of the clinical care of radiation contaminated patients (eg, thermal/radiation burns, fluid management, infection control), screening for radiation exposure, triage, decontamination, administration of medical countermeasures and the provision of supportive emotional and mental health care will be overwhelmingly nurse intensive.Reference Veenema and Thornton9-Reference Karam11 Empirical evidence suggests that health-care providers may not possess the knowledge needed to provide clinical care during these events.Reference Veenema, Walden and Feinstein12-Reference Murray, Kim and Ralston14 The purpose of this study was to explore RITN program centers health-care workforce knowledge of the medical effects of radiation, medical and nursing management of victims, and self-perceptions of clinical competence and willingness to respond to radiation/nuclear events. The research team established a partnership with RITN to conduct this study. Specifically, this research project considered: (1) What are RITN HCPs’ level of knowledge regarding preparedness and response to radiation emergencies/nuclear events? (2) Are RITN HCPs clinically competent to respond to radiation emergencies/nuclear events? (3) Are RITN HCPs willing to respond and provide care to patients during radiation emergencies/nuclear events?

METHODS

This study used a cross-sectional survey administered in April and May 2019 to a purposive sample of health-care providers currently employed at RITN centers. The National RITN Program Coordinator sent out an email invitation to the 74 RITN hospital and blood bank centers to participate in this study. Each RITN center coordinator then sent out the link to the online anonymous survey to their respective health-care providers. Health-care providers were put into 2 groups: physicians and advanced practice providers (physician assistants and nurse practitioners) abbreviated from here on out as MDs/APPs and registered nurses (RNs). Study participants were asked to click on a Web link to access a multi-item survey in the Qualtrics Research Suite Software specific to their discipline’s scope of practice. Participation was voluntary, responses were anonymous, and all surveys included information detailing the purpose of the study and contact information for the research team. The email invitation was sent out 3 times by RITN over a period of 3 wk.

Survey Development

Two unique RITN health-care workforce surveys were developed, 1 for MDs/APPs and 1 for RNs (Online Appendix A), based upon the specific scope of practice and the roles and responsibilities of each discipline. Each survey is a rapid self-administered questionnaire and survey questions were derived from previously published studiesReference Veenema, Walden and Feinstein12,Reference Murray, Kim and Ralston14,Reference Charney, Lavin and Bender15 addressing workforce development for radiation and nuclear events. The survey questions were reviewed for validity by subject matter experts at the Radiation Emergency Assistance Center Training Site (REAC/TS) in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The survey contained 10 knowledge questions for MDs/APPs and 12 knowledge questions for RNs. Additional questions addressed self-perception of clinical competence, willingness to respond to a radiation event, and education and training. Finally, 2 questions asked about tools and opportunities that would advance knowledge, skills and abilities to respond to a large-scale radiation event.

Ethical Considerations

This study and the supporting survey instruments were approved by both the Johns Hopkins and Emory Institutional Review Board, and were reviewed and approved by RITN leadership before distribution (Johns Hopkins Institution Review Board #IRB00206042).

Statistical Analyses

A summary report was generated using the “Reports” feature and was exported in comma-separated values (CSV) format to Excel for data analysis. Survey questions were grouped into knowledge domains: Medical management/medical effects of radiation (MME) and radiation emergency response (RER). The MD/APP participants were asked 10 knowledge questions: 7 MME and 3 RER. Registered nurses were asked 12 knowledge questions: 4 MME and 8 RER. Additionally, all participants were asked to respond to the following 2 statements, “I consider myself clinically competent to participate in patient care during a radiation emergency” and “I am willing to respond and participate in patient care during a radiation emergency.”

Continuous variables were described using medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were described using percentages and 95% confidence intervals. Ordinal logistic regressions were used to evaluate predictors of knowledge test performance as well as willingness and competence to respond to emergencies. Odds ratios (OR), P-values, and CIs were computed using bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping (5000 resamples). Because the knowledge tests differed across provider types, analyses involving the knowledge test were conducted separately for MDs/APPs and RNs. Across the data set, 11.4% of the data were missing (not answered). The patterns of missingness were consistent with missing-completely-at-random mechanisms for both MDs/APPs (P = 0.29) and RNs (P = 0.15). Twenty complete data sets were imputed using fully conditional specification. All variables were used in the imputation model. All analyses were conducted using SPSS v25 (Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

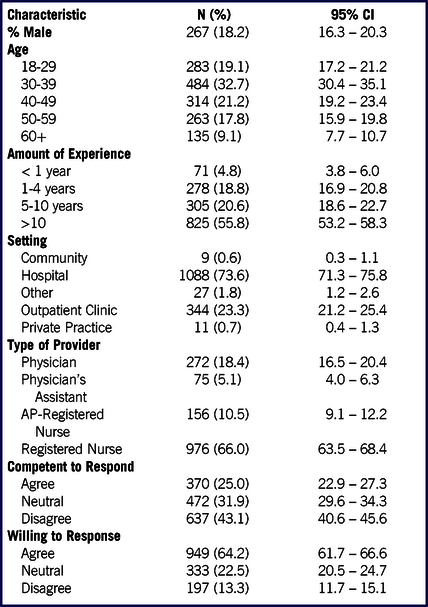

The survey was sent to 6826 potential respondents, and we received a response from 1635 providers (23.7%). Of the 1635, 156 respondents (9.5%) provided few-to-no responses (eg, provided consent to participate but did not continue with the survey). This resulted in a final sample size of 1479 (976 RNs and 503 MDs/APPs). Respondent characteristics are presented in Table 1. Most respondents identified as female (81.8%). The majority of respondents were registered nurses (66.0%) followed by physicians (18.4%), advanced practice registered nurses (10.5%), and physician assistants (5.1%). Just over half of the respondents reported having 10 or more years of full-time work experience in their respective health-care discipline, and nearly one-third of them indicated they were between the ages of 30 and 39 y of age. The majority of those who responded work in a hospital, followed by those who work in an outpatient clinic. Physicians/APPs were more likely to be male (OR = 1.32; 95% CI: 1.26-1.37), were older (OR = 2.17; 95% CI: 1.77-2.67), and had more experience (OR = 1.86; 95% CI: 1.49-2.32) than RNs.

TABLE 1 Respondent Characteristics

N: Frequency

%: Percentage

95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval

Knowledge Scores

For MDs/APPs, the median test score was 60% (IQR: 40-70). Both AP-RNs (OR = 0.51; 95% CI: 0.35-0.74) and PAs (OR = 0.44; 95% CI: 0.26-0.74) received lower scores than physicians. 10+ y of experience was associated with higher scores than <1 y (OR = 3.46; 95% CI: 1.20-9.98). Neither 1-4 y (OR = 1.53; 95% CI: 0.46-4.98) nor 5-10 y (OR = 2.70; 95% CI: 0.86-8.52) were associated with greater scores than 0-1 y. Those who agreed that they were willing to respond/participate in a radiation emergency received higher scores (OR = 2.94; 95% CI: 1.18-7.35) than those who disagreed. Those who responded “neutral” did not receive higher scores than those who disagreed (OR = 2.03; 95% CI: 0.74-5.52). Respondents who either considered themselves competent to respond to a radiation emergency (OR = 2.01; 95% CI: 0.94-4.33) or responded “neutral” (OR = 1.69; 95% CI: 0.91-3.15) did not receive higher scores than those who did not consider themselves competent. Respondents who had taken 2 or more courses received higher scores than those who had completed no prior coursework (OR = 2.18; 95% CI: 1.28-3.70). Those who had taken a single course outside of initial training (OR = 1.23; 95% CI: 0.74-2.07) or 1 course as part of their initial training (OR = 1.34; 95% CI: 0.74-2.41) did not score higher than those who had completed no prior coursework.

For RNs, the median test score was 50% (IQR: 33-58). Both those with 10+ y of experience (OR = 3.56; 95% CI: 1.96-6.47) and 5-10 y of experience (OR = 2.88; 95% CI: 1.56-5.3) received higher scores than those with less than 1 y of experience. Those with 1-4 y of experience did not receive higher scores (OR = 1.67; 95% CI: 0.91-3.07). Those who agreed that they were willing to respond/participate in a radiation emergency received higher scores (OR = 1.77; 95% CI: 1.14-2.74) than those who disagreed. Those who responded “neutral” did not receive higher scores than those who disagreed (OR = 1.24; 95% CI: 0.78-1.97). Both respondents who considered themselves competent to respond to radiation emergencies (OR = 1.74; 95% CI: 1.26-2.41) and those who responded “neutral” (OR = 1.40; 95% CI: 1.06-1.84) received higher scores than those who did not consider themselves competent. Both those who had taken 2 prior courses (OR = 3.81; 95% CI: 2.49-5.82) and those who had taken a course outside of their initial training (OR = 1.95; 95% CI: 1.31-2.92) received higher scores than those who had never taken a course. Those who had completed 1 course as part of their initial training did not (OR = 1.05; 95% CI: 0.75-1.48).

Education and Training

When asked about prior attendance at radiation emergency management courses, nearly two-thirds of respondents (64%) reported having never attended an emergency management course. Twelve percent reported having attended a course as part of their initial training in nursing or medical school and 11% reported having attended a course outside of their initial training. Only 12% said they have attended 2 or more emergency management course trainings. When asked if they had personally experienced a radiation emergency event, only 2% reported that they had experienced a radiation emergency event. Working in a clinic versus working in some other setting was unrelated to course attendance (P = 0.19).

Willingness to Respond

When asked the question “I am willing to respond and participate in patient care during a radiation emergency,” 64% indicated that they agreed with the statement. However, 22% responded “neutral” to this statement, and 13% said they disagreed with the statement. Predictors of willingness to respond to an emergency are presented in Table 2. Respondents who were older, more experienced, employed in a hospital, more knowledgeable, and who had received training rated themselves more willing to respond.

TABLE 2 Predictors of Willingness and Competence to Participate

Abbreviations

APP: Advanced Practice Provider, one category consisting of all data for Physicians, Advanced Practice Registered Nurses and Physician Assistants

MD: Physician

PA: Physician Assistant

OR: Odds Ratio

95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval

p: p value

Clinical Confidence to Respond

When asked the question “I consider myself clinically competent to participate in patient care during a radiation emergency,” only 25% of respondents said they agreed with the statement whereas 32% responded “neutral” and 43% disagreed with that statement. Therefore, 75% responded that they either did not consider themselves clinically competitor to provide care to patients in a radiation emergency or they were neutral to this task. Predictors of competence to respond to an emergency are presented in Table 2. Respondents who were older, more experienced, physicians, employed in a hospital, more knowledgeable (for RNs), and who had received training considered themselves more competent to respond to emergencies.

Just-in-Time Education and Training Delivered by Means of App

When asked the question “In the event of a large-scale radiation release or nuclear event, how valuable would an online/downloadable ‘just-in-time’ education & training program (App) be to help you respond?”, 64.3% of MDs/APPs said this method of content delivery would be “very valuable.” Additionally, 14.3% of MDs/APPs said they would find this method of content delivery “somewhat valuable.” Registered nurses were similarly receptive to this form of content delivery with 68.7% indicating they would find this form of education and training “very valuable” followed by 22.0% who indicated this would be “somewhat valuable.” Overall, 78.5% of MDs/APPs and 90.7% of RNs said they would find this form of education and training “valuable” should a radiation emergency or nuclear event happen in their area.

Advancing Knowledge Skills and Abilities to Respond to a Large-Scale Radiation Event

Respondents were asked to identify education and training opportunities that would assist them in advancing their knowledge skills and abilities to respond to a large-scale radiation event. They were given 4 options as well as an “other” category where they could fill in additional information. They could choose as many options as applied. For MD/APP/, the most common selection was an App (57.8; 95% CI: 53.7-62.0). This was followed by an online module (57.2%; 95% CI: 53.0-61.4), in-person education (49.4%; 95% CI: 45.2-53.7), and drills and exercises (42.7%; 95% CI: 38.5-46.9). A total of 12.9% indicated some other preference. For RNs, the most common selection was an online module (60.2%; 95% CI: 56.0-64.3). This was followed by in-person education (57.7%; 95% CI: 53.5-61.9), drills and exercises (47.2%; 95% CI: 43.0-51.5), and an App (41.1%; 95% CI: 36.9-45.3). A total of 4.7% indicated that they have some other choice.

DISCUSSION

The RITN concept of operations is based on the anticipated surge in distant communities following the large-scale release of radiation or the detonation of an improvised nuclear deviceReference Charney, Lavin and Bender15 in which tens of thousands of patients will need to be cared for by specialists who have dealt with the complications resulting from hematopoietic transplantation that mimic the symptoms of acute radiation syndrome.16 RITN collaborates with the US federal Department of Health and Human Services-Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response to coordinate the movement of patients through its National Disaster Medical System (NDMS). The NDMS transports patients to hospitals to provide definitive care for trauma and other medical needs following national disasters. RITN has worked diligently to prepare for the potential medical surge as well as developing materials to assist medical professionals to prepare to receive and care for these casualties, recognizing that the RITN health-care workforce will play a critical role in the effectiveness of a disaster medical response to a disaster resulting from the release of radiation into the environment. Radiation emergency events are so rare that the majority of the respondents in this study had never cared for a patient with radiation exposure not related to medical/therapeutic treatment.

Overall, knowledge scores were low for both groups, with MD/APPs performing slightly better than RNs. Evaluation of the knowledge test questions across domains revealed that HCPs with greater number of years of experience had a higher score on the knowledge test. HCPs who reported being willing to respond generally scored higher on the knowledge test. For registered nurses, those who considered themselves competent to respond scored higher on the knowledge test.

Evaluation of attendance at education and training was dramatically lower than what was expected. Of note, the RITN centers offer a multitude of educational offerings, workshops, and training opportunities, yet HCPs who took the survey mainly reported they have not had any training. This finding raises several questions. How does RITN identify and engage their specific RITN-affiliated health-care providers, and how do they communicate to increase awareness of the availability of radiation emergency training and resources? Generally, the RITN centers report that they typically disseminate educational resources and training to a small engaged group; however, this study revealed that this group is not clearly defined. RITN needs to provide guidelines as to who is a RITN provider, so they can focus education and training on this sector of the workforce. By more accurately defining the denominator, RITN can administer training and measure outcomes. Additionally, it has been found that the training materials and the lengths of the trainings can vary across centers. The question remains as to how much beyond this small group do these trainings reach.

Our findings are in accordance with the limited but expanding evidence-based literature on the perceptions of the hospital-based workforce toward radiation emergency response,Reference Karam11-Reference Murray, Kim and Ralston14,Reference Knebel, Coleman and Cliffer17,Reference Balicer, Catlett and Barnett18 which have articulated gaps in HCP awareness, knowledge of radiation, and willingness to respond. Veenema et al. documented nurses’ lack of self-perceived clinical competence and the relationship between perception of personal safety and willingness to respond. Others have documented limited knowledge of radiation and willingness for radiation response among medical residents, physicians, nurses,Reference Veenema, Walden and Feinstein12,Reference Knebel, Coleman and Cliffer17-Reference Becker and Middleton19 and medical toxicologists in particular.Reference Sheikh, Mccormick and Pevear13 Most notable is that schools of medicine, nursing, and public health are not adequately preparing HCP students for radiation response.Reference Murray, Kim and Ralston14,Reference Veenema, Lavin and Bender20 This failure to adequately prepare HCP students translates into our findings that substantiate a lack of radiation response knowledge in the health-care workplace.

CONCLUSIONS

In the event that a large-scale release of radiation into the environment were to occur, a surge of patients would present to RITN centers through transfer or self-referral demanding care. Physicians, advanced practice providers, and registered nurses will be needed to respond quickly and competently to meet the needs of these patients. This study explored RITN program center’s health-care workforce knowledge of the medical effects of radiation, medical, and nursing management of victims, and self-perceptions of clinical competence and willingness to respond to radiation/nuclear events. Attendance at previous radiation emergency management courses and knowledge scores were disappointedly low for all HCP respondents. While the majority indicated they were willing to respond to a radiation event, few believed they were clinically competent to do so.

Analysis of the results suggest that RITN and the RITN center coordinators should consider more clearly defining their RITN affiliated health-care workforce and establishing an ongoing education and training program to engage and sustain their staff. It would be helpful to define core competencies for RITN affiliated health-care workforce, design a curriculum that addresses them, and to increase communications to ensure that their HCPs are aware of the broad spectrum of education and training resources that RITN offers. RITN center coordinators would be well served to advocate to hospital/health center administration for just-in-time training for all health-care providers and to consider other sources for workforce training and preparedness if on the job training is not adequate to prepare their workforce. Integrated training involves time and money, and while both may be in short supply in most health-care settings, training is critical for an effective response. Exploration of incentives and outreach to engage higher participation in RITN education and training activities would be a valuable action step. RITN and RITN center coordinators may be able to help advance the development of social media and digital resources for providing just-in-time training for radiation emergency response and medical management of radiation effects. Finally, increased federal government support for the RITN education and training programs would advance a better response when these resources are ultimately needed.

Limitations of the Study

This study used self-reported data and is thus subject to the limitations associated with survey research. The overall response rate to the survey was relatively low (21.7%), and the sample may not be representative. RITN center coordinators were asked to send the Web link to the surveys to their staff and other HCPs who would be expected to participate in the immediate response to a radiation event (eg, emergency department HCPs, and hematology/oncology HCPs), leading to some confusion at some of the RITN centers as to who the appropriate target population was for the study. It is possible that the survey was sent to people who were not in the RITN provider network.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Cullen Case, Senior Manager of Business Continuity and Program Manager of Radiation Injury Treatment Network (RITN) and Jen Aldrich, Radiation Injury Treatment Network (RITN) Program Coordinator for Emergency Preparedness, National Marrow Donor Program (NDMP) & Be the Match, for their input and ongoing support of this study. The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Carol Iddins and Angie Bowen at the Radiation Emergency Assistance Center and Training Site (REAC/TS) for their review of the survey tools.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.253.