Of all the new challenges that outbreak communication faces in the 21st century, the revolution in the field of information and communication technologies has produced a new set of challenges. The risk-communication aspect of pandemic outbreaks has developed to such an extent that it almost threatens to overshadow the pure health care aspect of virus containment. To cope with epidemic crises, advances have been made in theories and models of risk communication and crisis communication and specifically emerging infectious disease communication. Some of these theories and models draw heavily from crisis management theory, such as the Three-Stage ModelReference Ray 1 and Fink’s four-stage cycle.Reference Fink 2 The limitations of these models are that they are overly general and tend to be structured in linear, hierarchical terms that downplay the environmental and cultural aspect of the public. Few models of crisis management have attempted to address the environmental and cultural aspects of crises, such as Turner’s Six-Stage Sequence of Failure in Foresight,Reference Turner 3 which emphasizes social processes that help to constitute order, including the development of social norms, processes, and practices. Turner’s work conceptualized the crisis as a “cultural collapse” in which the normative and social structure is no longer “accurate or adequate.”Reference Turner 3

The understanding that coping with an epidemic crisis should occur by situating the public sociologically and psychologically has led to changes regarding the role of communication in crisis management. Much progress has been made since the predominance of the principle of the hypodermic needle, whereby the public is “injected” with the message. For example, the Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication (CERC) model of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has given pride of place to feedback and two-way communication between the organization and the public.Reference Courtney, Cole and Reynolds 4 Another notable model is the Four-Channel Model, which focuses on transactive communication, situating the public at the center and viewing it as an active partner and not merely a recipient.Reference Pechta, Brandenburg and Seeger 5 This repositioning of the public as an active participant is facilitated by new mobile technologies, especially smartphones and Internet-based tools.

Although the consensus is that this theory is updated and relevant, in practice, information flow remains unilateral in many countries. The call for “engagement” of the public is a concept that still reflects a passive audience to be engaged, and does not take into account the polyvocality of the public and a reality in which the opinions and knowledge of the public “compete” with those of the health authorities. Moreover, the understanding that the public in the 21st century is a full partner necessitates a greater understanding of the social and technological realms in which the public operates.

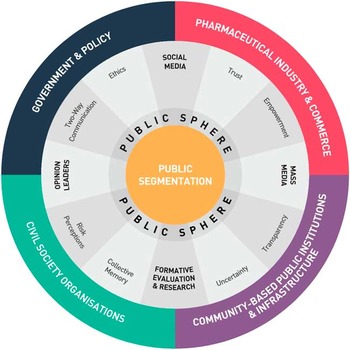

With this in mind, this article addresses the challenges that organizations face when communicating with the public sphere. We conceptualize our approach through a framework formulated in the TELL ME (Transparent communication in Epidemics: Learning Lessons from experience, delivering effective Messages, providing Evidence) FP7 project.Reference Gesser-Edelsburg, Valter and Shir-Raz 6 The present article will not concentrate on the framework as a whole, but rather will examine its central component, namely, the public sphere. The framework—unlike models such as those mentioned above—is not predicated on arrows connecting the organizations and the public, but refocuses in greater detail behind the scenes of the public sphere. Like the rhizome theory proposed by the philosophers Deleuze and Guattari, which emphasizes multiple connections and heterogeneity,Reference Bogue 7 the TELL ME project aimed to map a reality in which communication is multidirectional, proliferating in many directions, and in which the average citizen plays an active role in the communication process. The model is designed to identify misconceptions related to various stakeholders functioning in crisis communication and shows how each of them can work in a manner that exploits the new social and technological reality. The model encompasses existing stakeholders but points to gaps and challenges that must be considered in light of health crises that have occurred in recent years. Before continuing to expand on the public sphere, which is the subject at the crux of this article, we will briefly describe the various stakeholders in our model and the misconceptions regarding them.

MASS MEDIA

The mass media is a dominant component in our model. The present-day media map has undergone a revolution, making it more varied and complex than ever and transforming its role in outbreak communication, including new potential for two-way communication. Communication between formal organizations and the press should be routine and frequent. According to our findings, however, official meetings between health organizations and the press occur mainly in the context of outbreaks. As a result, the press becomes fixated by the notion that “conference” equals “outbreak.”

Mass media should voice public concerns, while the organizations should provide convincing responses to mitigate ongoing concerns. Because of this misconception, health organizations often fail to respond directly to public concerns in actuality and instead focus on sharing epidemiologic information. Sensationalism often characterizes media reporting on disease outbreaks. It is not uncommon for journalists to report by appealing to emotion through the use of powerful metaphors, intimidation, and in some cases, apocalyptic predictions about the future.Reference Nerlich 8 , Reference Wallis and Nerlich 9 Another tendency is to define something or to describe a situation in absolute terms (eg, good/bad, true/false), which often leads to contradictions. Our model reevaluates the role of journalists in the communication process to present accurate risk information and empower the public.

SOCIAL MEDIA

The next component is social media, which extends to include different types of channels, including Internet forums, social blogs, social networks, weblogs, wikis, and podcasts. Each channel has different features and sometimes targets a specific audience. Social media constitutes an excellent resource to approximate and address general public concerns in real time, without the need for intermediaries (ie, the traditional media). Information flows and messages arrive “clean” to and from the source, without emotion-driven elements.

Social media discourse affects outbreak communication and our ability to reach the public.Reference McNab 10 We highlight two prominent conceptions in outbreak communication models, arguing that they actually constitute misconceptions. The first is that messages are unequivocal. It is not enough to construct a powerful and persuasive message, because many variables change over the course of an outbreak. The second is that an organization can choose not to respond. The 2009 H1N1 outbreak suggests that silence on the part of official organizations sets the stage for misinformation.

These misconceptions are relevant for the present model. Because encoding does not equal decoding, and the same words or messages can have different meanings depending on context, messages are not unequivocal in all circumstances. On the contrary, messages can be interpreted differently by different people in different contexts.Reference Hall 11 In determining or predicting how a message may be understood, the interaction between the sender and the recipients is affected by several categories that are part of discourse analysis, including genre, rhetoric devices, narratives, characters, visual representations, and language. Later in this article, when we describe changes that occurred in the public sphere, we will expand on the dilemmas that arise during a crisis and how organizations cope with these dilemmas.

OPINION LEADERS

The next component of outbreak communication is the opinion leaders.Reference Katz and Lazarsfeld 12 Opinion leaders are trustworthy members of our social network. A common misconception regarding opinion leaders is that they hold an official leadership position and have high social status. However, this is not necessarily the case. Opinion leaders can also be charismatic laypeople, such as neighbors, friends, or colleagues, whose ability to engage and influence others puts them in a position to distill information from the mass media and pass along the condensed version through an additional filter of subjectivity. In the context of new media, this definition can be extended to people with a large number of followers who are considered to have expertise on specific domains. We can harness the potential inherent in such grass-roots opinion leaders for spreading messages of outbreak communication. The concept of opinion leaders explains the dominance of interpersonal relations in the media. According to the two-step flow theory, opinion leaders have more influence on people’s opinions, actions, and behaviors than do the media.Reference Nisbet and Kotcher 13

INSTITUTIONAL STAKEHOLDERS

Our model redefines the category of stakeholders by moving health care workers from this category, seeing them instead as part of the public sphere. The model defines stakeholders as follows. Each group of stakeholders has its own set of challenges, which are briefly outlined below. The first group is government and institutional actors (policy makers). The national subgroups include surveillance, institutes, medicine regulatory agencies, and national health ministries. The local subgroups include the local public health authorities, prefectures, and local political parties. Transnational subgroups include the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Tourism Organization of the United Nations (UNWTO), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), and the World Bank. European subgroups include the European Commission, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and the European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines (EDQM). With regard to communications, this group faces key challenges such as increased demand for information from multiple sources, lack of inter-governmental dialogue on an international level, and inter-sectorial coordination on a national level and prioritization of actions and allocation of resources.

The second group of stakeholders is the pharmaceutical industry and commerce. The national subgroups include manufacturers, suppliers, distributors, and exporters. The local subgroups include storage depots and professional representatives of the industry. The transnational subgroups include manufacturers and wholesalers. The European subgroups include associations such as the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries (EFPIA), the European Association of Pharmaceutical Full-line Wholesalers (Groupement International de la Repartition Pharmaceutique [GIRP]), and EuropaBio. Key challenges these organizations face include liability issues and that they can become the primary target of anti-vaccine groups.

The third group of stakeholders comprises community-based public institutions and infrastructure. The local subgroups include primary schools, hospitals, day care centers, clinics, and public transport. Key challenges in the event of an infectious disease outbreak are varied levels of knowledge, experience, and resources, as well as the fact that any shift from normal has an immediate impact on the entire community.

The fourth group consists of civil society organizations. National subgroups include nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), foundations, and charities. Local subgroups include community-based organizations, faith-based groups, and anti-vaccine alliances. Transnational groups include the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and other NGOs. The European subgroups include associations such as European Public Health Alliance (EPHA), the European Forum of Vaccine Vigilance, and Alliance for Natural Health (ANH) Europe. The key challenges to these subgroups are that communication needs are not usually fully explored (at a local level) and that there is heavy reliance on the media as a channel for the reception of information and the transmission of messages.

RESEARCH

Research constitutes a crucial component of the model that enables organizations to locate stakeholders and to pinpoint misconceptions. The common practice regarding the evaluation of health crises is to conduct an evaluation before or after a crisis. Examples include pro-vaccination campaigns and epidemiologic surveillance. Instead, our model suggests building public profiles through qualitative and quantitative studies pinpointing different subpopulations and identifying different trends in public discourse. According to our model, research should initiate and shape discourse and then help to shape campaigns and policies. Moreover, research should be conducted both on a community level as part of an ethnographic effort to build profiles and also on an aggregative level as part of discourse surveillance. Later in this article, we will expand on the importance of research in identifying public discourse in the public sphere.

All the components of our model encompass the public sphere. We present the framework diagram in order to illustrate that the public sphere is positioned at the center, deemphasizing boundaries between it and 7 key components (such as opinion leaders, formal stakeholders, the media, etc) that encompass and embody it (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 Communication Framework.

This article is divided into 2 parts. The first part treats the public sphere in the context of health and pandemics. The second part treats how organizations cope with the transformation of the public from recipient to equal partner. How do health organizations deal with the public’s anxiety and concerns that arise in the new media during outbreaks? To what extent do the organizations address these concerns?

THE PUBLIC SPHERE IN THE CONTEXT OF PANDEMICS

Our framework refocuses the center of communication on the public sphere. Because communication evolves from within the public sphere, it must take into account an in-depth understanding of it. This is where communication occurs and where other components or actors operate (eg, stakeholders, opinion leaders, and social and mass media). This is where concepts like transparency, risk perception, collective memory, trust, and ethics come into play.

The public sphere is critically important for modern societies. Its value lies in its ability to facilitate uninhibited and diverse discussion of public affairs. It presents a domain of social life in which public opinion is expressed and collectively relevant issues are communicated.Reference Ray 1 Most contemporary conceptualizations of the public sphere are based on the ideas expressed by Jurgen Habermas in his book The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere – An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society.Reference Habermas 14 According to Habermas, the public sphere is a neutral social space for critical debate among private persons who gather to discuss matters of common concern in a free and rational way. This sphere is open and accessible to the public. Habermas’s public sphere is characterized by 3 major elements: (1) disregard of status (rejection of hierarchy), (2) domain of common concern and interest, and (3) inclusivity (everyone must be able to participate).Reference Habermas 14 Thus, engagement within the public sphere according to Habermas is blind to class positions, and the connections between those active in the public sphere are formed through a mutual will to take part in matters of general interest.

Habermas claimed that the new type of bourgeois public sphere that had emerged in Western Europe in the 18th century began to decline in the first half of the 20th century owing to educational and capitalistic progress resulting in a stratified society with fewer mutual concerns. He pointed out that mass media contributed to the decay of the rational-critical discourse, turning the public sphere into a space where the rhetoric and objectives of public relations and advertising are prioritized, and thus, into a vehicle for capitalist hegemony and ideological reproduction.Reference Habermas 15

Today, however, many media researchers, as well as political scientists and political activists, believe that the new media have given a renewed spirit to the concept of the public sphere and that new media have the potential to change societal communication from its foundations.Reference Jankowski and van Selm 16 - Reference van Os, Jankowski and Vergeer 18 Indeed, the World Wide Web has become a domain in which people can openly express and share concerns about broader societal issues. This is because it is widespread and its infrastructure promises unregulated and unlimited discourse that operates beyond geographic boundaries.

Pandemic Outbreaks and the New Public Sphere

The massive changes in the media environment and its technologies have transformed the mass media in ways that have made audiences less predictable, more fragmented, and more variable in their engagement.Reference Silverstone 19 Since most of the traditional news media have established websites and many of their readers are using them, the distinction between traditional media and new media is not clear-cut. Moreover, there is an intensive dialogue on whether these new communications technologies have revitalized the public sphere in ways that have created a real change in the discourse or are actually reproducing the traditional media discourse in new platforms.Reference Fenton 20 Clearly, there are pros and cons to the speed and accessibility of information in the new media. The current article focuses mainly on the civil aspect of new media usage, namely, as a tool used by the public to search for information.

The public takes great interest in media coverage of health issues.Reference Jankowski and van Selm 16 - Reference van Os, Jankowski and Vergeer 18 Studies and polls have indicated that the new media have become an important source of health-related information.Reference Cline and Haynes 21 , Reference Tustin 22 These findings indicate how wide the use of new media is, not only by those who create information, but also by the vast majority of people who search for health information. In fact, the reliance on new media for this purpose has become so widespread that Internet health consumers have been dubbed “e-patients.”Reference Masters, Ng’ambi and Todd 23 For instance, in the case of influenza, search engine query data from YahooReference Polgreen, Chen and Pennock 24 and GoogleReference Ginsberg, Mohebbi and Patel 25 and tweets mentioning the flu and related symptomsReference Lampos and Cristianini 26 were found to be closely associated with seasonal influenza activity. Also, the Internet is a major source of information about vaccines.Reference Larson, Smith and Paterson 27

There has been a recent increase in research on the use of new media in response to emergent situations, including pandemic outbreaks.Reference Bults, Beaujean and Richardus 28 - Reference Zhang and Gao 31 In 2003, the world first learned of SARS through a post written by a Chinese citizen. SARS broke out in November 2002, and killed 774 people and infected 8000 persons in 27 countries.Reference Gordon 30 The initial post quickly spread through e-mail to tens of thousands of Americans. This is remarkable given that at that time, the most popular social networking sites of today were yet to be established, not to mention the censorship policy in China, where the virus originated. The importance of the role of the public in spreading information can be seen from a study by Vultee and VulteeReference Vultee and Vultee 32 that examined Twitter messages following 4 US disasters in 2009. The investigators found that 94% of the messages on Twitter came from the public sharing information and only 3% were from government agencies. The 2009 H1N1 outbreak also caused an increase in social networking activity and in blogs. Twitter was used to disseminate information from credible sources to the public and as a platform to share personal experiences and opinions.Reference Chew and Eysenbach 29 Twitter messages containing the term “swine flu” rose from almost zero to 125,000 per day by May 1, 2009. Blogs showed a similar pattern, with a large increase in the percentage of blogs mentioning “swine flu.”Reference Petrie and Faasse 33 Additionally, at the height of the flu pandemic, there were more than 500 Facebook groups dedicated to H1N1 discussions.Reference Davies 34 Another example is the 2011 H7N9 flu pandemic in China. Zhang and Gao found that during the pandemic, social media was used as a platform to share information and for collaboration among different users.Reference Zhang and Gao 31

The new media have become not only an important source of health information during epidemics, but also a medium for expressing anxiety and discussing concerns about the illness,Reference Petrie and Faasse 33 , Reference Tausczik, Faasse and Pennebaker 35 treatments, and prevention measure.Reference Bults, Beaujean and Richardus 28 , Reference Signorini, Segre and Polgreen 36 Findings suggest that the new public sphere and its discourse during health crises should be of great interest for health authorities.Reference Bults, Beaujean and Richardus 28 , Reference Signorini, Segre and Polgreen 36 Despite high vaccination rates across the world, 37 - 39 increasing numbers of parents tend to delay vaccination for their children or refuse selected vaccines. This trend, in which benefits and dangers of vaccines are evaluated rationally,Reference Jacobson 40 , Reference Velan, Boyko and Lerner-Geva 41 is often defined as “vaccination hesitancy.” Such anti-vaccination and selectivity messages are more widespread on the Internet than in other media,Reference Davies, Chapman and Leask 42 and social media more critically evaluates vaccination information than does the news media.Reference Lehmann, Ruiter and Kok 43 During the 2009 H1N1outbreak, there was a pronounced rise in use of social media to express concerns related to vaccine side effects or to vaccination risks.Reference Signorini, Segre and Polgreen 36 Furthermore, those who refused to vaccinate reported information-seeking behavior more often and more frequently solicited advice from their social network than did vaccine accepters.Reference Bults, Beaujean and Richardus 28 This discourse of doubts and concerns, as well as the anti-vaccination messages, may influence parents’ vaccination decisions and increase vaccination hesitancy and refusal trends.Reference Betsch, Renkewitz and Betsch 44 , Reference Kata 45

Organizations’ Challenges and Dilemmas When Facing the Public Sphere

In the current reality in which the public sphere gives laypeople increasing influence and control, the question is how organizations can respect the power emanating from the public sphere, while still exerting influence based on their professional knowledge and expertise in order to manage the outbreak. As mentioned above, one of the three main characteristics of Habermas’s public sphere is rejection of hierarchy and disregard of status.Reference Habermas 14 This means that in the public sphere, the word of health organizations—even central organizations with international authority such as the WHO—is equal to the word of charismatic bloggers and other Internet users. Unofficial posts and blogs can have influence equal to or greater than organizations’ assessments and recommendations. However, crisis situations such as pandemic outbreaks present a challenge to the idea of the public sphere. On one hand, a dialogue between equals, or two-way communication, has the potential to enhance organizational relationships with the public and help them achieve their goals.Reference Thackeray, Neiger and Burton 46 On the other hand, the organizations are still the ones who have the professional knowledge, and they are the ones who manage the crisis. The question we raise in this study is how this duality works. How in this situation, in a sphere that gives much more power to the public, can organizations act in a way that respects the equal powers and yet expresses their professional knowledge and allows them to manage the outbreak?

The lessons learned during the SARS outbreak in 2002 to 2003 and the experience of communicating this crisis led the WHO to develop the WHO Outbreak Communications Guidelines. 47 The Guidelines stipulate that all acute public health event communications should be planned, organized, and executed according to 5 main principles: trust, announcing early, transparency, listening to the public, and planning.Reference Härtl 48 Furthermore, the WHO has also conducted considerable training—both of its own and of health ministry staff around the world—in the art of communicating quickly and effectively according to the 5 principles established by the organization.Reference Härtl 48

During the past decade, owing to the vast changes in the online communication environment, and particularly following the H1N1 influenza pandemic, there has been a growing interest by public health organizations in the use of social media as part of their communication strategies,Reference Jones 49 - Reference Thackeray, Neiger and Smith 51 and in fact as a central means of getting news out quickly.Reference Härtl 48 For example, the WHO, CDC, and Health Protection Agency (HPA) all have Twitter accounts, Facebook pages, and YouTube videos.Reference Jones 49 The CDC’s Facebook page was launched in May 2009 to communicate information and safety updates about the H1N1 flu. 52

In addition, the CDC used YouTube videos to provide information, in addition to traditional media channels, and one of the first videos released garnered 2.1 million views on YouTube.Reference Walton, Seitz and Ragsdale 53 At the same time, the number of people following the CDC’s “emergency profile” on Twitter increased from 65,000 to 1.2 million within a year, and the agency created online applications, or widgets, that provided information that could be displayed on other Web sites.Reference Merchant, Elmer and Lurie 50 The 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic was the WHO’s first experience with social media as well. The organization used Twitter to update regarding the daily increases in case numbers and also monitored what was being said about the WHO in social media. However, without a clear policy or experience of how to deal with this new public sphere, its engagement was limited at that time.Reference Härtl 48 In addition to international organizations, health organizations at the national level also began to use social media during the 2009 outbreak. For example, tweets made by the Virginia health department about the location of vaccination sites led people to flock there within minutes.Reference Merchant, Elmer and Lurie 50

While the literature indicates that international and national health authorities are actively using social media such as Twitter and Facebook, it also shows that this use is still very limited, because these tools serve as one-way communication tools, instead of two-way, interactive communication mechanisms. As Danforth et al noted, “Although other research has shown that the public uses sites such as Twitter and Facebook to communicate in emergency situations, response agencies have been slow in tapping into this type of communication tool.”Reference Danforth, Doying and Merceron 54

Several studies found that although Twitter and other social media tools are being adopted by state and local health departments, their primary use involves one-way communication on personal health topics and on organization-related topics.Reference Thackeray, Neiger and Burton 46 , Reference Thackeray, Neiger and Smith 51 , Reference Neiger, Thackeray and Burton 55 The organizations’ use of social media mainly as a one-way communication tool is also evident in recent guidelines and textbooks. For instance, in the Pandemic Influenza Risk Management WHO Interim Guidance, published by the WHO in 2013, 56 the few times social media is mentioned, it is portrayed as a tool for messages and information dissemination alongside traditional media.

Although social media is indeed used by health organizations on all levels—local, national, and international—the use of social media involves one-way communication only, ie, “injecting” information, recommendations, and guidelines into the social media space. While this kind of activity is important for educating and engaging the public during a crisis, it is not the same as sharing or creating a dialogue with the public.

Furthermore, as the organizations’ guidelines and reports demonstrate, the public is still perceived as a recipient, not a partner. For example, the CDC’s report addressing lessons learned about H1N1, 2009 H1N1: Overview of a Pandemic, stresses that the CDC’s goal during the event was to inform the public. The report emphasizes that communications messages were tempered by the values “Be first, be right, and be credible.” 57 This well-known crisis communication mantra describes the characteristics of a top-down communication process: from the organization to the public.Reference Falls and Deckers 58 Although organizations do seem to realize the importance of the new public sphere, they do not act upon the criteria, as delineated by Habermas, because their activity does not treat the public as an equal partner, which deserves and demands cooperation, not just information.

Segmentation in the Public Sphere

Another basic condition that characterizes Habermas’s public sphere is inclusivity, ie, it has to be accessible to all participants, so that everyone can participate.Reference Habermas 14 However, a pre-condition for accessibility to the discourse conducted in the public sphere is the ability to understand and make sense of it. To participate in the communication process, the information presented in it must be clear and understandable to all. People understand and interpret risks differently based on various factors, including gender, education level, income, culture, and ethnicity.Reference Slovic 59

Organizations must convince the public to adopt their messages about protective measures such as vaccines, and in order to do so effectively, must tailor their messages according to socioeconomic, cultural, educational, and other contexts, rather than using one-size-fits-all messaging.Reference Furgal, Powell and Myers 60 - Reference Lindell and Perry 62

Indeed, international health authorities have addressed the subject of segmentation in their outbreak communication guidelines and reports.Reference Gesser-Edelsburg, Mordini and James 63 For example, the WHO’s International Health Regulations (2005) highlighted the importance of “taking into consideration the gender, sociocultural, ethnic or religious concerns of travelers.” 64 The 2008 edition of the World Health Organization Outbreak Communication Planning Guide stressed the need to “Conduct an assessment of existing public communication capacity and existing research of community understanding, including demographics, literacy levels, language spoken as well as socio-economic and cultural backgrounds.” 65 The CDC’s publication Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication: Pandemic Influenza recognized that “Nonetheless, one size fits all never fits all people equally well,”Reference Reynolds 66 and noted that it was important to “understand audience by age/culture/level of experience or familiarity with the subject/language/geographic location.”Reference Reynolds 66 The idea of segmentation is also addressed in reports that have examined how the messages in the guidelines were conveyed to the public. These reports have indicated that special populations were targeted with specific prevention and control messages; key messages were provided to specific groups; and articles were targeted to specific audiences.Reference Lam and McGeer 67

However, despite the theoretical foundation and understanding exemplified in the guidelines and reports, this understanding is not translated into practical “how-to” recommendations at the local level, ie, how exactly national health authorities should build segmented profiles of their publics.Reference Gesser-Edelsburg, Mordini and James 63 The gap between understanding and practice is indeed evident when examining local levels. In a Global Communications Conference, which took place in the midst of the H1N1 pandemic, countries were called on to adapt the communication strategies to their specific cultural needs.Reference Brennan and Hall 68 The mere fact that such a call was made points to a general lack of such cultural and social adaptation.Reference Gesser-Edelsburg, Mordini and James 63 Although government agencies have long recognized their responsibility to be sensitive to problems with one-size-fits-all messaging,Reference Fischhoff 69 several studies have indicated that the idea of segmentation is still far from being adequately implemented. For example, an evaluation of how First Nations and Metis people in Manitoba, Canada, responded to the public health management of the H1N1 pandemic concluded that to better tailor both the messages and delivery, public health agencies need to devote more attention to the specific socioeconomic, historical, and cultural contexts of such communities. This is because they are most at risk when planning for, communicating, and managing responses associated with pandemic outbreaks.Reference Driedger, Cooper and Jardine 70 Similarly, evaluations of the risk communication practice during the H1N1 outbreak involving Pacific Peoples and Māori in New Zealand,Reference Gray, MacDonald and Mackie 71 Australian Aboriginal, and Torres Strait Islander communitiesReference Massey, Miller and Saggers 72 - Reference Rudge and Massey 74 concluded that more community-based information dissemination mechanisms were needed to avoid problems created by generic prevention and control messages.

These examples demonstrate that although the idea of segmentation is addressed in the international health authorities’ guidelines and reports, the recognition of its importance still does not translate into practical recommendations. As a result, segmentation does not occur at the local level, so that national authorities still use standardized and uniform messages and delivery channels for the various groups that comprise the public sphere.

HOW TO TREAT THE PUBLIC’S CONCERNS

Another central challenge facing health organizations during outbreaks is dealing with the public’s anxiety and concerns. The gaps that remain in the emerging infectious disease communication field are demonstrated by outbreaks such as H1N1 in 2009 to the ongoing Ebola crisis in Western Africa, indicating that basic tools are still needed. In the Ebola crisis, cases were first reported on February 9, 2014, 75 yet the WHO did not declare an outbreak until March 23. 76 Hence, for almost 2 months, there was hardly any news coverage or social media response. In addition, the overt messages delivered by health authorities regarding the risk degree contradicted the covert ones. Whereas the overt messages stressed that the risk of contracting the disease was very low because the virus spreads mainly through direct contact with body fluids,Reference Cassoobhoy 77 the articles describing the 2 infected American aid workers who had returned to the United States, and their admission into hospitals with special containment units,Reference Achenbach, Dennis and Hogan 78 sent a different message. This recent example and many others from various outbreaks indicate that notable gaps remain between the degree of severity as perceived by the public and the actual severity.

According to Sandman, risk perception comprises hazard plus outrage.Reference Sandman 79 This means that other than the scientific aspect, feelings of outrage toward the risk must be considered. People associate high risk with issues toward which they have negative attitudes, regardless of the proved risk. The public’s view of risk (as opposed to that of the experts) reflects not just the danger of the action (hazard), but also how they feel about the action and what emotions it produces (outrage). Lack of agreement between experts’ and the public’s perception of hazard and outrage can lead to controversy. According to Sandman, one of the most important ways of dealing with the negative feelings of a population toward a certain issue is continuous communication with that population.Reference Sandman 79 The success of risk communication depends on the communicator’s efforts to minimize the gap between the expert’s risk assessments and the public’s perceptions in order to create mutual feedback between experts and the public.Reference Fischhoff 80

Uncertainty about health issues often prompts individuals to seek information.Reference Tausczik, Faasse and Pennebaker 35 , Reference Rosen and Knäuper 81 In the case of outbreaks, recent studies have demonstrated that Internet tools such as blogs and Twitter reflect the public’s anxiety and concerns.Reference Tausczik, Faasse and Pennebaker 35 , Reference Signorini, Segre and Polgreen 36 For instance, during the H1N1 outbreak, blogs mentioning “swine flu” used significantly more anxiety, health, and death words and fewer positive emotion words than did control blogs.Reference Tausczik, Faasse and Pennebaker 35

How do health organizations deal with the public’s anxiety and concerns voiced in the new media during outbreaks? To what extent do health organizations address these concerns? Some recent examples demonstrate that health organizations fall short in handling this topic. For instance, in press conferences held by the WHO during the H1N1 outbreak, as concern surrounding the vaccine’s safety surged, the WHO experts were asked several times by members of the media to address these concerns. Instead of tracking these concerns and addressing them in an immediate, accurate, and transparent manner, as the following quote illustrates, they expressed a dismissive attitude toward them, calling those concerns “rumors” and “disinformation.” They tried to recruit the media to help eliminate the “rumors” and to convince the public of the vaccine’s safety and importance:

“…vaccines are really one of prevention methods against infectious diseases which is the best in terms of efficacy, the safest and really we are always worried when there are rumors of vaccine safety and most times, these rumors are unfounded so it needs to be reacted to very quickly… we hope that we will have the assistance of the press to help us dissipate, when it is appropriate, as soon as possible these rumors about vaccines being unsafe.” 82

Furthermore, the WHO representatives even call the concerns related to the vaccine’s safety “conspiracies”:

“Really… this is not the time to discuss or try to work out whatever conspiracies there may be. This is a time to work together, to produce more, to distribute more and to protect as many people as possible against this pandemic virus.” 83

An example of the way health authorities use new media to deal with concerns raised by the public is illustrated by Doshi:Reference Doshi 84

“In October 2009, the US National Institutes of Health produced a promotional YouTube video featuring Fauci. Urging US citizens to get vaccinated against the H1N1 influenza, Fauci stressed the vaccine’s safety: ‘the track record for serious adverse events is very good. It’s very, very, very rare that you ever see anything that’s associated with the vaccine that’s a serious event.’”

To deal with the challenge and meet the public’s concerns, first and foremost, the public’s concerns must be tracked and monitored. In past years, health authorities did try to track the public’s concerns and monitor perceptions of health threats through the use of telephone surveys.Reference Lau, Kim and Tsui 85 - Reference Rubin, Amlôt and Page 88 Such surveys provided valuable information about the public’s concerns during the H1N1 outbreak.Reference Rubin, Amlôt and Page 88 Nevertheless, telephone surveys are limited in their ability to provide up-to-date information and they provide only a narrow window into public perceptions at the time the data are gathered.Reference Groves 89

To help assess anxiety and concerns, scholars have suggested using Web-based methodologies as an insight into public response to infectious disease outbreaks.Reference Tausczik, Faasse and Pennebaker 35 , Reference Signorini, Segre and Polgreen 36 These types of methodologies are increasingly used in medical contexts with informal surveillance systems, such as Google Flu TrendsReference Brownstein, Freifeld and Madoff 90 , Reference Dukic, Lopes and Polson 91 or FluBreaks.Reference Pervaiz, Pervaiz and Abdur Rehman 92 Specifically, online data mining analyzes the public via social discourse trends, noting correlations between the search words people use online and current events. This approach, known as “Internet-based bio-surveillance,” “digital disease detection,” or “event-based surveillance,” has been described and analyzed in the literature.Reference Brownstein, Freifeld and Madoff 90 , Reference Hartley, Nelson and Walters 93 , Reference Hartley, Nelson and Arthur 94 In the context of outbreak communication, this simple discourse surveillance tool can be used to identify people’s fears and concerns as the outbreak unfolds, both on local and international levels, even focusing on specific areas or specific group profiles. Data mining is crucial for locating misinformation and disinformation as well as trends in public health concerns regarding the outbreak and treatments recommended, such as vaccines and medications. Data mining is likewise crucial for developing an appropriate response for facilitating communication with the public. Nevertheless, on the level of communication systems, it has not yet been widely implemented. Evidence for its usefulness is provided by several recent studies. For example, Tausczik et al investigated the effectiveness of new web-based methodologies in assessing anxiety and information seeking in response to the 2009 H1N1 outbreak by examining language use in weblogs, newspaper articles, and web-based information seeking. They concluded that these methodologies may be a useful early marker of public anxiety and provide new insight into public response to infectious disease outbreaks.Reference Tausczik, Faasse and Pennebaker 35 Similarly, Signorini et al found that estimates of influenza-like illness derived from Twitter chatter accurately track reported disease levels and concluded that Twitter could be used as a measure of public interest or concern about health-related events.Reference Signorini, Segre and Polgreen 36 These findings demonstrate that monitoring web-related activity provides a dynamic picture of the way the public responds to an outbreak and that fluctuations in public anxiety about the outbreak can be detected in online writing and searching trends.

DISCUSSION

This article has addressed the challenges that organizations face in communicating with the public sphere. For each of the dilemmas presented in the article, we suggest the following lines of thought to possible solutions to be examined in further research:

Dilemma No. 1: How to Convey information?

The solution suggested: Instead of speaking in all-or-nothing slogans, convey precise and updated information that includes elements of uncertainty

The public sphere in the 21st century is predicated on 2 main components: technology and globalization. Technology facilitated the growth of the new media that has eased public access to information that had been exclusive to health and government organizations. Moreover, technology has bridged geographic distances in order to create partnerships between communities and to heighten their capacity to make appropriate health-related decisions. The public sphere empowers the layperson. Although, as noted above, international organizations have aspired for years to relate to the public as a partner, notable gaps remain that must be bridged. The public desires explanations that go beyond messages like “It is important to vaccinate” or “There is a health crisis.” The public instead is seeking in-depth explanations and to be kept abreast of all developments, including situations of uncertainty and ambiguity. A study examining the public’s reaction to the immunization campaign launched by the Israeli Health Ministry following the 2013 polio outbreak in the country has shown that rather than all-or-nothing slogans, the public demands full information.Reference Gesser-Edelsburg, Shir-Raz and Green 95 Poor communication by the relevant health care provider might lead parents who are not “vaccine refusers” and who usually comply with routine vaccination programs to hesitate or refuse to vaccinate their children. Furthermore, it has been argued that access to honest and diversified information can encourage the public’s participation in decision-making about health risks.Reference Beierle 96 - Reference Palenchar and Heath 98 The importance of conveying risk information, including issues regarding uncertainty, is emphasized by Johnson and Slovic,Reference Johnson and Slovic 99 who argue that, “Some analysts suggest that discussing uncertainties in health risk assessments might reduce citizens’ perceptions of risk and increase their respect for the risk-assessing agency.” Maxim et alReference Maxim, Mansier and Grabar 100 found that uncertainty did not elicit panic in their case study. Rather, conveying uncertainty by the authorities was reassuring, except in certain cases. Sandman emphasizes the need to “proclaim uncertainty.” He advises as follows: “When imperfect, tentative information is all you have, then imperfect, tentative information is what you must give people so they can decide how best to cope.”Reference Sandman and Lanard 101

Dilemma No. 2: How to Get the Public to Cooperate?

The solution suggested: Involve the public and take into account cultural characteristics

In order to involve the public and obtain cooperation, it is important to take into account cultural characteristics. To this end, an efficient tool would be to conduct formative research aimed at constructing profiles of diverse risk groups participating in the public sphere, emphasizing their beliefs, and pinpointing community leaders and ideologies around preventive measures. The best time to conduct this kind of research is in the interpandemic phase, the period between influenza pandemics, so that as the outbreak unfolds, these group profiles can be used to adjust the messages to the specific audiences. A good example is Al Gore’s Climate Project. Like vaccination, climate change can also be very controversial. Gore’s site identified 1000 local-level opinion leaders. These leaders were then contacted, sent formal material, and personally trained by Gore. Each opinion leader passed this information on to the public through lectures in public spaces. These campaigns were extremely successful because the messages were mediated through trusted sources.

Dilemma No. 3: How to Respond to the Public’s Concerns?

The solution suggested: Respect the public’s concerns and identify them in order to address them

One of the most important ways to address the public’s concerns and deal with negative feelings of a population toward a certain issue is continuous communication with that population.Reference Sandman 79 In order for serious consideration of public concerns to occur, it is crucial for organizations to forgo a judgmental stance toward public concerns that contradicts the opinions of health experts and to take into account cultural sensitivities. Instead of responses that revolve around “misconceptions” and “misinformation” regarding concerns expressed by the public, organizations must conduct dialogues free of prejudices and preconceptions in order to address the public as a partner.

Furthermore, as Slovic et alReference Slovic, Finucane and Peters 102 demonstrate, the public’s risk perception is composed of both emotionality and rationality. The “analytical system” model was presented as a person’s ability to analyze rules and norms and calculate risks and opportunities, whereas the “experiential system” model was presented as intuitive, quick, automatic, and partially subconscious. They claimed that the rational and the experiential systems operate simultaneously and that each seems to depend on the other for guidance. Rational decision-making requires proper integration of both modes of thought. Other solutions include developing discourse surveillance as a tool to identify trends in public health concerns regarding the outbreak and treatments recommended, such as vaccines and medications; locating misinformation and disinformation; and developing an appropriate response for facilitating communication with the public.

Dilemma No. 4: How to Cope With the Transformation of the Public From Recipient to Equal Partner?

The solution suggested: Share management considerations with the public

As mentioned above, crisis situations such as pandemic outbreaks present a challenge to the idea of the public sphere. On one hand, a dialogue between equals has the potential to enhance organizational relationships with the public and help them achieve their goals.Reference Thackeray, Neiger and Burton 46 On the other hand, the organizations who have the professional knowledge are still the ones who have to manage the crisis. The solution suggested to this dilemma is to share management considerations with the public. Although using social media as a tool to convey information is important for educating and engaging the public during a crisis, it is not the same as sharing or creating a dialogue with the public. Sharing management considerations can bring the organizations closer to consensus communication, and as a result, to improved cooperation of the public with the organizations’ recommendations.

Limitations

This article had limitations that warrant discussion. First, the recommendations suggested above are meant to serve as an infrastructure or a thinking mode that needs to permeate from the level of international organizations to the level of local organizations. We are aware that some of the solutions we listed exist in one form or another in the literature. However, it seems to us that on a practical level, these solutions are not applied. In addition, we recognize that it is not an easy task to turn these recommendations into a tool kit, and we did not presume to present a detailed one. This task should be addressed in future work. Second, the framework we used represents a theoretical approach that emphasizes the importance of the public sphere in order to examine how organizations function within it. Validating this framework requires performing simulations and case studies that will examine how various stakeholders operate within the public sphere in real time.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 278723 (TELL ME).