The treatment of acute injuries, management of environmental risks, and prevention of the spread of infectious diseases take precedence in most disaster response models.Reference Ford, Mokdad and Link1 As made painfully evident by Hurricane Katrina, such models should be augmented to include the provision of continued care to patients with chronic conditions (eg, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, cardiovascular disease, cancer). Reference Kario, McEwen and Pickering2–Reference Mokdad, Mensah and Posner4 Estimates of the proportion of Katrina-affected individuals with 1 or more chronic illness diagnoses range from 41%Reference Brodie, Weltzien and Altman5 to 74%.Reference Kessler6 Continuity of care for chronic diseases (CDs) has been identified as the major health care provision issue in the storm’s aftermath.Reference Ford, Mokdad and Link1,Reference Brodie, Weltzien and Altman5,Reference Edwards, Young and Lowe7–Reference Krol, Redlener, Shapiro and Wajnberg12

Disasters have the potential to damage the health care infrastructure, which is the basis for the provision of continued care to patients with CDs. Indeed, Katrina crippled the medical care fabric of the Gulf Coast.Reference Madamala, Campbell and Hsu13, Reference Weisler, Barbee and Townsend14 Federally funded community health centers (CHCs)—the safety net of the region’s underinsured and uninsured—sustained an estimated $65 million damage in Louisiana and Mississippi. Of the estimated 288 health center sites operating in those states in 2004, 32% were lost or severely damaged.15 Health and social service providers were displaced, with an estimated 28% drop in the number of board-licensed primary care physicians in Louisiana alone between 2005 and 2006.Reference Madamala, Campbell and Hsu13

We sought to identify major elements of disaster preparedness and response that should be integrated in the formulation of models that incorporate provisions for continuity of care to patients with CDs in the aftermath of a disaster. We used qualitative research methodology to document and analyze the experiences of individuals and institutions involved in the delivery of health care to Katrina-affected populations. We report a data-driven, collective assessment of the problems faced, strategies used, and policy recommendations formulated to effectively prepare for and support adequate care for chronically ill people in the aftermath of a disaster.

METHODS

Interviews, work groups, focus groups, and electronic communications were used to collect qualitative data in 3 phases from July 2006 to June 2007. Semistructured, in-depth key informant (KI) interviews were conducted with 30 health and social service providers from organizations in coastal Mississippi and Alabama (Table 1). Four focus groups were conducted with patients with CDs (n = 28 participants). Two of the focus groups were made up of HIV/AIDS patients, recruited from support organizations; the other 2 included patients with various CDs recruited from CHCs. Facilitators used an open-ended question guide to elucidate from participants the chronic diseases deserving priority and their postdisaster management needs. Sessions were recorded and professionally transcribed for analysis. Written informed consent was obtained from all of the participants, in accordance with institutional review board protocol.

TABLE 1 Participating Types of Institutions and Job Descriptions of Key Informants

In phase II, 1 KI from each organization was invited to participate in an advisory panel (AP) workshop. Panel members (n = 11) were divided into 2 work groups and discussed topics that were unclear or unaddressed in KI interviews: the critical components of postdisaster CD management, resources needed, and actions that could streamline patient care across organizational boundaries. In a plenary session, each group presented a summation of findings to the project’s external advisor, a New Orleans-based physician who worked after Katrina in both the hospital and CHC settings.Reference DeSalvo16–Reference DeSalvo and Kertesz20 Work groups and the plenary session were recorded for transcription and analysis.

Using a grounded theory approach,Reference Patton21 2 research team members (R.D.F., M.L.I.) independently analyzed and coded phase I transcripts for emerging concepts using Atlas.ti software version 5.2.9.22 The use of emergent (as opposed to predetermined) coding promotes the inductive identification of patterns among the responses from which conceptual hypotheses are developed without forcing the data into preset categories or theories. Instead, identified patterns in the data are grouped into categories, which summarize the underlying thematic constructs and provide explanations of the experiences of participants.Reference Glaser23

Code families, or groups of salient themes, were used to generate lists of quotations relevant to each theme. This computer-generated narrative was then analyzed for content and summarized by a multidisciplinary team composed of a medical doctor (E.D.C.), a medical anthropologist (RDF), and a doctor of business management (M.L.I.). The team wrote a comprehensive report compiling phase I and II findings for distribution to all KIs.

In phase III, advisory panel members were invited to submit electronic feedback on the report, and other KIs were invited to join work groups. A questionnaire designed to identify perceived gaps or flaws in the report draft was distributed to all phase III participants. Results presented below focus on comments, opinions, and proposed solutions regarding CD management after a disaster. Findings specific to HIV/AIDS will be reported in a forthcoming manuscript.

RESULTS

Chronic Diseases of Priority

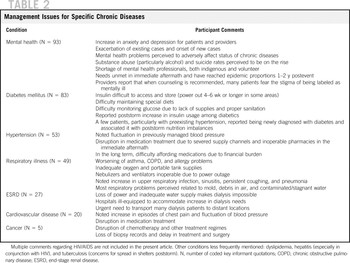

Chronic diseases identified as medical management priorities by KIs are mental health (n = 93 times referenced in transcripts), diabetes mellitus (n = 83), hypertension (n = 53), respiratory illness (including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma) (n = 49), end-stage renal disease (n = 27), cardiovascular disease (n = 20), and cancer (n = 5). A summary of diseases and comments related to their postdisaster management is presented in Table 2. CDs discussed by patients were mental health (n = 35), respiratory illness (n = 19), diabetes (n = 15), hypertension (n = 13), cardiovascular disease (n = 2), and cancer (n = 1).

TABLE 2 Management Issues for Specific Chronic Diseases

Chronic Disease Management Issues

Aside from the specific needs of oxygen-dependent patients and those requiring dialysis, CD management needs revolved around maintaining the continuity of medication regimens. One KI stated, “Diabetics could not get their insulin. Or they could not keep their insulin refrigerated. Then blood sugar was a big problem. Appropriate food—and so they are eating 4000-calorie Meals Ready to Eat with no insulin. For hypertensives, it was getting medicines and keeping control of their blood pressure. Getting medicines. Keeping medicines.” Specific problems encountered, strategies that worked in solving those problems, and policy-related recommendations are detailed below.

Medical Records

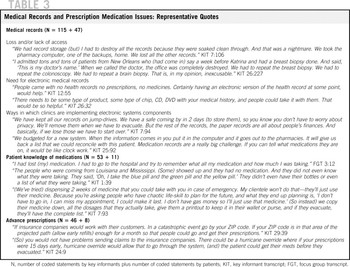

Accessing medical records onsite (lost to flood waters) or at a distance (for displaced patients) was virtually impossible after Katrina (n = 115 + 47; KI mentions plus focus group mentions). Lack of appropriate medical records required providers to run new diagnostic tests, causing delays in resumption of treatment regimens. KIs agreed that electronic medical records would solve this problem. Providers recommended that portable or distally accessible personal electronic health records should be made available to patients (eg, central server, jump drive, DVD). An alternative is to encourage patients to carry a card containing frequently updated health and medication information. See Table 3 for representative statements.

TABLE 3 Medical Records and Prescription Medication Issues: Representative Quotes

Medication Issues

Medication-related problems (n = 333), particularly medication procurement (n = 183 + 68), were the most frequently mentioned challenges to CD management by both patients and providers. Factors affecting the provision of medications included the system’s appropriate supply of medications (n = 75 + 0), the patient’s knowledge of medications (n= 53 + 11), patients’ financial abilities (n = 25 + 10), and the regulations that govern the dispensing of medications (n = 15 + 5) (Table 4).

TABLE 4 Medication Procurement Issues: Representative Quotes

Many patients arrived at new provider facilities without their prescriptions or bottles, and with inadequate knowledge of their medical histories or medication names and dosages. Providers had to be creative in helping people remember: “One of our nurses, our case manager (glued) our top 100 medicines on a peg board and said, ‘Point to your medicines.’” To circumvent financial barriers, many providers and some pharmacists reportedly distributed small supplies of medications free of charge or pharmaceutical samples to their patients. Churches, pharmaceutical companies, and large drugstore franchises dispensed and accepted medication vouchers.

KIs thought patients should have at least a 1-month extra supply of medications to avoid therapy interruptions postdisaster. Regulations dictating the periodicity of refills in Medicaid and some private insurance policies, however, prevent patients from stocking more than the usual monthly allowance (n = 46 + 8). In such cases, KIs recommended overrides with patient education for appropriate storage. Immediate action by public authorities—such as relaxing Medicaid regulations to permit claims to be transmitted across state lines, and allowing pharmacists to refill up to a 30-day supply of medications as long as patients had some proof of current prescriptions—went a long way in facilitating the dispensation of medications (Table 3).

Donated Medications and Supplies

Although providers received helpful donations of medications, many—often cut off from communication channels—reported receiving large quantities of unrequested, inappropriate, and expired medications from unidentified sources. Classifying medications and disposing of unusable items was a burden on providers already struggling to dispose of disaster-related debris. In some instances, providers were forced to let surpluses become ruined in inclement weather due to lack of storage space. Others sorted donated medications and networked to redistribute surpluses to facilities in need. KIs recommended increased communication between potential donators and target health care facilities to assess needs. When the power supply returned, e-mail communications in conjunction with volunteer-run databases worked well for some KIs, linking potential donors, volunteer pools, and sites in need.24, 25

Critical Medications Needed

KIs stressed the need for antibiotics, antihypertensives, oral glucose–lowering agents in addition to insulin, medications for anxiety and depression, lipid-lowering agents, and asthma medications: “Our main focus is on maintenance medications for chronic-type conditions like high blood-pressure, high cholesterol, heart disease, diabetes. There was (also) quite a spike in demand for anxiety medications (and) various forms of heart disease. Probably (also) a considerable spike in asthma medication (and) for pulmonary conditions.” With regard to medical supplies, the most pressing need was for oxygen and oxygen tanks.

Provider and Patient Disaster Planning

KIs identified planning and preparedness as essential elements to effective natural disaster response (n = 186 + 19). Provider’s recommendations include: backing-up of medical records, stocking and protecting essential medications, ensuring that all staff know the disaster plan and their roles, and preparing back-up communications systems in case of telephone and Internet outage.

KIs believed that patients should take a more proactive role in the management of their disease. Cultivating patient responsibility requires enhanced patient education and empowerment. This is a challenge among at-risk populations with unstable housing, employment, and transportation situations. Providers also stressed the importance of using multiple media to reach patients (eg, newspapers, radio, provider letters, television).

Operational and Networking Issues

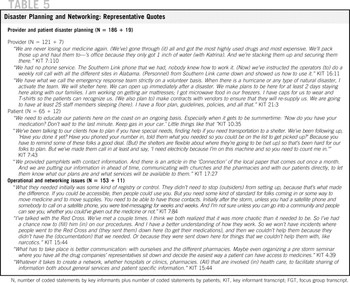

KIs (n = 153 + 11) believed that aid from volunteers, aid agencies, and governmental groups was vital to disaster relief and recovery. They stressed that it is crucial, however, that outside aid groups coordinate efforts with local organizations and work alongside local organizations and providers to meet the community’s needs (n = 26 + 9). Coordinated efforts need to start predisaster if possible. Response/recovery efforts with leadership (or co-leadership) originating from within the disaster area worked well to ensure that aid reached the community (n = 23 + 2). Moreover, such efforts had a greater likelihood of sustainability, some transcending short-term outcomes to continue to affect the health and recovery of the community today (Table 5).

TABLE 5 Disaster Planning and Networking: Representative Quotes

Providers emphasized the importance of centralized receipt and sorting followed by the decentralized distribution of medicines, medical supplies, and basic necessities. KIs proposed that a community-based group in constant contact with the local emergency operation center and with local and state officials should be responsible for such coordination. Predisaster, the group should network with faith-based groups, relief organizations, and even pharmaceutical companies. Networking predisaster ensures familiarity of entities with the local health care infrastructure. In the event of a disaster, the group would assess and communicate to the network the medical supply and medication needs of health care entities and facilitate the movement of these to areas of greatest need.

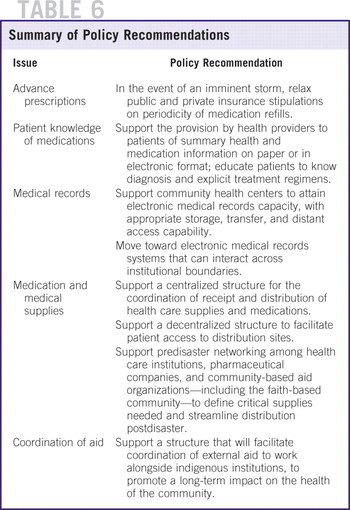

Table 6 provides a summary of the policy-related solutions proposed by KIs to the problems discussed in the sections above.

TABLE 6 Summary of Policy Recommendations

DISCUSSION

This study recorded and analyzed the experiences and perceptions of frontline medical care responders in the aftermath of Katrina. We systematically documented the CD management challenges experienced by indigenous health care providers, administrators, pharmacists, and community-based support organizations in the Mississippi and Alabama Gulf coasts. Challenges included inadequacy of predisaster preparation; lack/loss of medical and prescription medication records; insufficient patient knowledge of CD medications; regulatory, financial, and insurance barriers to medication purchase; inadequate and/or insufficient medication supplies; and lack of an effective structure to coordinate internal and external operations. Furthermore, we recorded field strategies used to provide continuity of care after Katrina and, through qualitative analysis, extracted policy recommendations formulated by study participants.

The major challenges to CD management were availability and affordability of prescription medications.Reference Edwards, Young and Lowe7,Reference Millin, Jenkins and Kirsch8,26,Reference Versel27 Strategies that could ensure the immediate availability of medications postdisaster are predisaster stockpiling coupled with safe storage, and the staging of supplies in locations just outside the perimeter of a potential disaster area under imminent threat. Reference Millin, Jenkins and Kirsch8,Reference Versel27,Reference Braun, Wineman and Finn28 Coordination of the receipt and distribution of medical/medication supplies is a key operational element in adequate CD management postdisaster. KIs advocated for a centralized structure for receiving supplies and medications, but a decentralized access model with patients retrieving medications at multiple community sites. Such a model is a recommended standard for the management of international drug donations.Reference Hogerzeil, Couper and Gray29

Given the added financial stressors after major disasters, the affordability of medications becomes a key barrier to CD management, especially for subpopulations living in poverty.Reference DeSalvo, Hyre and Ompad19, 26 Goodwill solutions (eg, free samples, cash vouchers) can solve immediate needs. Broad and equal access to free or reduced-cost medical care and prescription medications for underserved populations can be realized only through legislative channels, a point made by KIs. Emergency expansion of Medicare/caid coverage that allows for transstate coverage and shields individual states from matching fund contributions has been discussed by Congress.Reference Rosenbaum30, Reference Kutner31 Institutions such as the Kaiser Family Foundation32 and the Children’s Health Fund33 continue advocating for a comprehensive legislative solution to affordable medical care for underinsured or uninsured populations affected by disasters.

Donated medications increased the availability and affordability of prescription drugs after a disaster. Antihypertensives, glucose-lowering agents, medications for anxiety and depression, asthma medications, and antibiotics were identified as the most useful medications for major CD management needs. A formulary should be developed to guide medication donations postdisaster and should be widely circulated among potential donating institutions.Reference Hogerzeil, Couper and Gray29

Some of the problems regarding donations sent to Katrina-affected areas have also been widely experienced by international recipients of aid.Reference Khare34 These have given rise to the formulation of 4 core principles for drug donations: maximum benefit to the recipient, respect for the wishes and authority of the recipient, no double standards in drug quality, and effective communication between donor and recipient.Reference Hogerzeil, Couper and Gray29 Although we can trace many of our study participants’ recommendations back to each of those principles, effective flow of communication stands out as one of the most important elements advocated by KIs in this study. A potential communication solution is programs such as “Rx Response,” designed to create a single forum for medication suppliers, community volunteer relief organizations, and local, state, and federal agencies responding to major disasters.35

To circumvent patients’ inability to remember the names and doses of their medications, our study participants advocated for a personal health record or continuity of care record, preferably in electronic format but alternatively in a paper copy. Patient-based medical information data repositories become mandatory in disaster situations in which patients need to access health care away from their usual providers. There are several major initiatives—from the centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the private sector—to implement the use of standardized, interoperable personal health record functions in medical care.Reference Versel27, Reference Endsley, Kibbe, Linares and Colorafi36 Primary care clinics in the Gulf Coast should be supported with funding to educate patients and staff on the use of personal health records or continuity of care records and to secure the technology infrastructure and supplies for incorporating these into day-to-day operations.

Another major area of system improvement considered critical by KIs was the use of information technology to record patient information, facilitate medical record sharing within and across institutions, support access to information at a distance, and ensure routine and emergency storage of data. The Department of Veterans Affairs health record system provides a model for such a system and it proved successful in support of evacuee health care after Katrina.Reference Brown, Fischetti and Graham37 The Department of Health and Human Services has stated its commitment to the formation of a national health information network. 36,38,39 The Gulf Coast region should be slated as a priority in establishing the local, state, and regional platforms of such a network.

The seminal elements in effective disaster response identified by participants in the present study and by other investigators are provider and patient disaster planning and the establishment of strong networks to support collaboration and synergy among the multiple response actors. Reference Atkins and Moy40–Reference Walsh, Orsega and Banks42 Achievement of their translation into operational practices hinges on 2 major facilitating streams: explicit policies that address the legal and liability roadblocks (eg, licensure reciprocity for volunteer health professionals, liability protection, interjurisdictional coordination, privacy) and appropriate funding to ensure that critical personnel and resources are available to develop, rehearse, and implement plans, as well as to create and sustain the necessary networks.Reference Gavagan, Smart and Palacio10,Reference Braun, Wineman and Finn28,Reference Atkins and Moy40,Reference Walsh, Orsega and Banks42–Reference Katz, Staiti and McKenzie45

Limitations

The present study is limited in that many other disaster response actors involved directly in or making decisions that affect the provision of health care were not included as participants. We are confident that the majority of institutions involved in providing care to underserved Gulf Coast inhabitants (the focus of the present study) were represented. By design, we limited data collection to the Gulf Coast counties of Mississippi and Alabama. Therefore, our results do not provide direct information on health care challenges experienced in Louisiana, but likely encompass the CD management needs of displaced Louisianans who sought refuge in Alabama and Mississippi.

Because the majority of health care institutions included in the study are primary care clinics, the information recorded relates to CDs usually managed in such settings and provides limited information on diseases typically managed in specialty clinics (eg, cancer, end-stage renal disease). Likewise, our study does not provide information on the postdisaster management of less prevalent diseases (eg, sickle cell disease). Another limitation is the small size and scope of the patient sample. Our sampling method—provider nomination for participation in focus groups with an emphasis on patients with HIV/AIDS—precluded the gathering of a broadly representative sample of CDs. Furthermore, we focus only on the adult population, given that KIs interviewed were mainly devoted to adult care. We oversampled patients with HIV/AIDS to document specific circumstances and strategies related to HIV/AIDS management; for example, issues of confidentiality and maintenance of complex highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens. Findings pertaining to HIV/AIDS are described in a separate article.

Conclusions

In addition to documenting and describing the most pressing CD management needs in the aftermath of a disaster—especially those burdening the underinsured and uninsured—the present study describes field strategies that effectively maintained continuity of care after Hurricane Katrina, documents major challenges faced, and lists policy-related recommendations to streamline health care response in the event of future disasters. Although some steps have been taken to improve the system’s response 4 years after Katrina, the challenge still lies in ensuring the political will and resource commitment that are necessary to systematically implement such recommendations.Reference Gavagan, Smart and Palacio10,Reference Braun, Wineman and Finn28,Reference Walsh, Orsega and Banks42,Reference Johnston and Redlener43

Authors' Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank our partners and participants for sustained dedication to this project amidst the hardships of recovery. We also thank Nicole Guidry, Tracey Henry, Mary McLean, and Susan Nelson for their invaluable contributions to data collection.

Supported, in part, by grant US2MP002001 from the US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health, to the Morehouse School of Medicine for the Regional Coordinating Center for Hurricane Response, with additional support from the National Institutes of Health, National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities grant 5P20MD002314-01.