Older adults are often among the most vulnerable to the adverse physical and mental health consequences ensuing from natural disasters. Reference Okamoto, Greiner and Paul1 - Reference Pekovic, Seff and Rothman7 For instance, older adults who experience a flood-related disaster tend to demonstrate more anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms than young or middle-aged adults who experience similar flood-related disasters. Reference Bei, Bryant and Gilson8 During the response and recovery phases of a natural disaster, pre-existing health problems may be exacerbated for some older adults, while new health conditions may develop among other older adults. Reference Pekovic, Seff and Rothman7 , Reference Kamo, Henderson and Roberto9 , Reference Zhang, Shi and Wang10 The availability of social support from family members, friends, neighbors, and others in the community can be crucial in mitigating negative, disaster-related effects among older adults. Reference Kamo, Henderson and Roberto9 , Reference Ngo11 The number of natural disasters in the United States has increased over time, and the country’s changing demographics have resulted in a larger older-adult population with variations in health and independence levels. Reference Tuohy and Stephens2 , Reference Brown and Frahm12 - Reference Van Der Vink, Allen and Chapin14 Thus, disaster-related research among older adults must expand to determine their access to social support and identify social network characteristics that may facilitate or inhibit this access.

Even though social network systems may be crucial for access to resources and the well-being of older adults, such systems may be disrupted or severed, especially when older adults must relocate from their homes because of a natural disaster. Reference Brown and Frahm12 , Reference Jungers15 , Reference Lutgendorf, Reimer and Harvey16 Relocation occurs when a person temporarily or permanently moves to a new place, and the type of relocation may depend on the impact of a disaster on an older adult’s home. Reference Brown and Frahm12 Relocation among older adults is problematic because limitations in health, frailty, and economic resources can decrease their capacity to adjust to a new environment while recovering from the disaster. Reference Okamoto, Greiner and Paul1 , Reference Chao17 Furthermore, the relocation process and the perceived lack of control of unfolding circumstances can cause additional stressors that complicate pre-existing health conditions that an older adult may have. Reference Kamo, Henderson and Roberto9 Brown and Frahm Reference Brown and Frahm12 have indicated that emergency preparedness protocols often include arrangements for residential care facilities for older adults, with limited attention being provided to the community-dwelling elderly (CDE) who may live independently or with family members. There is little evidence of the differences in social support, especially when comparing relocating CDE to nonrelocating CDE. Examining how CDE cope with disaster-related relocation may yield key insights about their access to support, their resilience, or lack thereof, and the impacts on the long-term recovery processes.

Increasingly, social support (emotional and instrumental support) has become essential for older adults’ successful recovery from disasters. Reference Heid, Schug and Cartwright18 - Reference Claver, Dobalian and Fickel20 Emotional support refers to the availability and quality of care, love, and empathy that a person receives from someone else with whom he or she can discuss various issues. Reference Berkman and Glass21 We define instrumental support as the provision of tangible, disaster-related needs such as food, transportation, and housing. Some studies on natural disasters among older adults have focused on the availability of network members to provide social support, analyzed satisfaction with social support, examined a single form of support, or combined several types of support to create a composite score. Reference Watanabe, Okumura and Chiu4 , Reference Chao17 , Reference Tyler22 - Reference Ticehurst, Webster and Carr25 Very few have identified the support that CDE need or receive immediately after a natural disaster, particularly in the context of relocation. Examining received and perceived support may provide more comprehensive information about potential gaps in disaster-related support provision for older adults.

Although social network characteristics, such as gender and composition, have previously been linked to social support provision for various circumstances, Reference Kawachi and Berkman26 - Reference Benkel, Wijk and Molander32 few studies have examined whether these network characteristics are also relevant for support provision among US CDE who are affected by natural disasters. Findings from other countries suggest, when older adults relocate because of natural disasters, social support from family members and friends is valuable. Reference Watanabe, Okumura and Chiu4 , Reference Chao17 , Reference Norris, Baker and Murphy33 Kin-based or friend-based networks may, therefore, be more important than other networks among CDE. Additionally, women are more likely than men to provide social support to network members, Reference Kawachi and Berkman26 , Reference Taylor27 but few studies have identified whether this relationship between gender and support exists with respect to older adults and natural disasters. Haines and colleagues Reference Haines, Beggs and Hurlbert34 demonstrated that having a higher proportion of female network members was associated with lower depressive symptoms, but not perceived adequacy of social support, among US hurricane victims. A focus on CDE may identify whether gender is a critical social network characteristic that is linked to support provision during natural disasters.

This study focused on the social support experiences of CDE who were living in and around Columbia, South Carolina, during the historical flood in October 2015. Five days of unprecedented rainfall resulted in major flooding, widespread property damage and infrastructural failure across the state. 35 The extraordinary level of flooding, with several inches of rainfall, was nicknamed the “1000-year” flood because of the low probability that such amounts of rain could occur in a year. 36 During the storm, many individuals were trapped by rising floodwaters and thousands lost access to power. 35 In October, more than 20,000 people were displaced, and 32 shelters were available in South Carolina. 37 The aim of the study was to examine social support for flood-affected CDE and to determine whether the types of social support received differed between relocating older adults and nonrelocating older adults. Specifically, we were interested in evaluating whether the emotional and instrumental support that CDE received was linked to relocation, and in identifying social network members who provided those types of support.

METHODS

Sample

Interviews with a convenience sample of CDE were conducted between December 2015 and May 2016 to learn about their experiences in the immediate aftermath of the flood. Twenty-five CDE were recruited through word of mouth, flyers, and an advertisement in The State, a local newspaper. Eligible participants spoke English and were aged 50 or older. During recruitment and at the time of the interviews, our study sample of individuals was still addressing some level of impact from the flooding. This impact ranged from clearing debris and draining flooded backyards to moving to a new home; thus, it was a challenge to obtain a larger sample. Face-to-face interviews, which involved the administration of semi-structured, paper-based questionnaires, lasted approximately 40 minutes and were conducted in restaurants, office spaces, and participants’ homes. The University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol (#Pro00050118) in November 2015.

Measures

Information on CDE’s social networks was gathered using name generator and name interpreter instruments. Name generators allow respondents to identify specific people within their social networks, using a real name or an alias. Reference Hlebec and Kogovšek38 Name interpreters are additional questions that provide in-depth information on named individuals and may identify links among those named individuals and the respondents. Reference Perkins, Subramanian and Christakis39 In the present study, there were two name generator questions. CDE were asked to name a maximum of three people who provided assistance at the time of the flooding. They were also asked to name a maximum of three people who assisted with their various needs since the flood ended. In response to the name interpreter instrument, CDE then provided demographic information about their social network members, indicated their relationship to each social network member (alter), and identified the specific types of social support that they had received from each alter.

To capture the complexity of social networks ties and the fact that alters were nested within CDE (egos), we measured variables at two distinct levels. Alter-related information was examined as level-1 variables while ego characteristics were examined as level-2 variables. The two types of variables are described below:

Level-1 Variables

Study participants reported details for each of the alters that they named. To reduce respondent burden and recall biases, we provided participants with dichotomous response options for alter variables. For example, instead of using a Likert-scale to measure support, we asked participants to identify whether they received support or not. Reference Adams, Urosevich and Hoffman40 - Reference Haines, Hurlbert and Beggs42 We examined five level-1 variables, including emotional and instrumental support as dependent variables:

-

(i) Emotional support: CDE were asked if each of the alters within their networks provided emotional support by being someone with whom they could talk. The response options for this question were yes and no; thus, the focus here was on the availability of emotional support. Emotional support was treated as a binary variable in the statistical analyses.

-

(ii) Instrumental support: CDE were asked whether each of the alters whom they named provided (a) food, (b) medication, (c) legal assistance, (c) housing, and (e) financial assistance. The response options for each of these instrumental support items were yes and no. Participants’ responses to each form of instrumental support were added together. To measure instrumental support, this count was converted into a binary variable. If an alter provided any of those five types of support, we considered the alter to have provided instrumental support to the participant. If not, we considered the alter to have not provided instrumental support.

-

(iii) Alter gender: Study participants provided information on the gender of each named alter.

-

(iv) Alter relationship: Study participants were asked to identify if each named alter was a family member, friend, or some other acquaintance. “Other acquaintance” was used as the reference group in the analyses.

-

(v) Flood-affected alters: CDE were asked whether each named alter was also affected by the Columbia floods. The response options were yes and no. This was one of the control variables for the study.

Level-2 Variables

-

(i) Ego gender: Study participants were identified as male or female.

-

(ii) Ego relocated: Each study participant indicated whether he/she had to move to a new location since the flooding. The response options were yes and no.

-

(iii) Need for emotional support: CDE were asked if they needed emotional support because of the floods. The response options were yes and no.

-

(iv) Need for instrumental support: CDE indicated if they needed instrumental support, specifically in the form of (a) food, (b) medication, (c) legal assistance, (d) housing, or (e) financial assistance, because of the floods. The response options for each type of support were yes and no. Each CDE’s responses were summed and converted into a binary variable. If he/she mentioned at least one of those items, then we assumed that individual needed instrumental support. If not, then we assumed that individual did not need instrumental support.

Analytic Strategy

To examine the associations between emotional and instrumental support and a person’s social network characteristics, statistical analyses proceeded in three steps using Stata version 14. 43 First, descriptive statistics for both egos and alters were calculated, with two-sample proportion testing used to examine whether the social networks of CDE who relocated were different from those of CDE who did not relocate. Second, bivariate analyses were conducted by examining the association between each independent and control variable and emotional support and instrumental support. Third, multilevel logistic regression was used to assess the association between emotional and instrumental support and the independent variables, while adjusting for significant control variables. This multilevel modeling approach was considered appropriate because network members (alters) were nested within CDE (egos), and it allowed for an estimate of the variance in emotional and instrumental support at both the alter level (level 1) and the ego level (level 2), using methods for calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient for logistic regression. Reference Merlo, Chaix and Ohlsson44

RESULTS

Descriptives

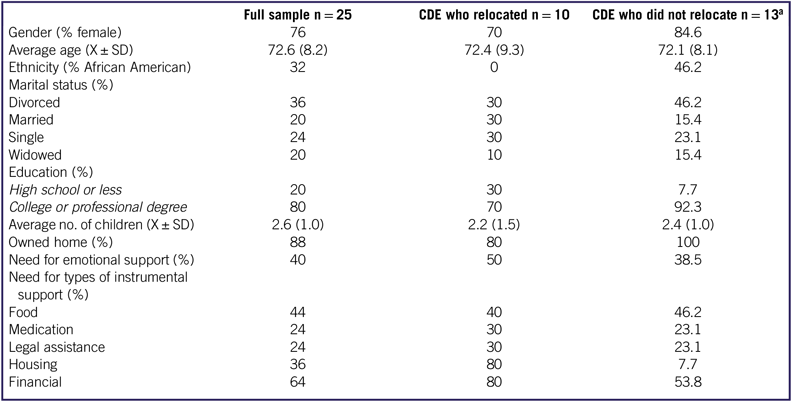

The sample characteristics of CDE who were affected by the 2015 flood in South Carolina are shown in Table 1. Their ages ranged from 52 to 91 years, with a mean of 72.6 years; most participants (68%) were white and female (76%). Most older adults (88%) were home owners, and 40% of them relocated because of the flood. Ego network sizes ranged from 0 to 6, with an average size of 4.3. Three older adults did not name any alters, and 14 (56%) older adults named a maximum of 6 alters.

TABLE 1 Characteristics of Flood-Affected CDE in Columbia, South Carolina

Standard deviations are shown in parentheses for average values.

a Relocation information was missing for 2 CDEs.

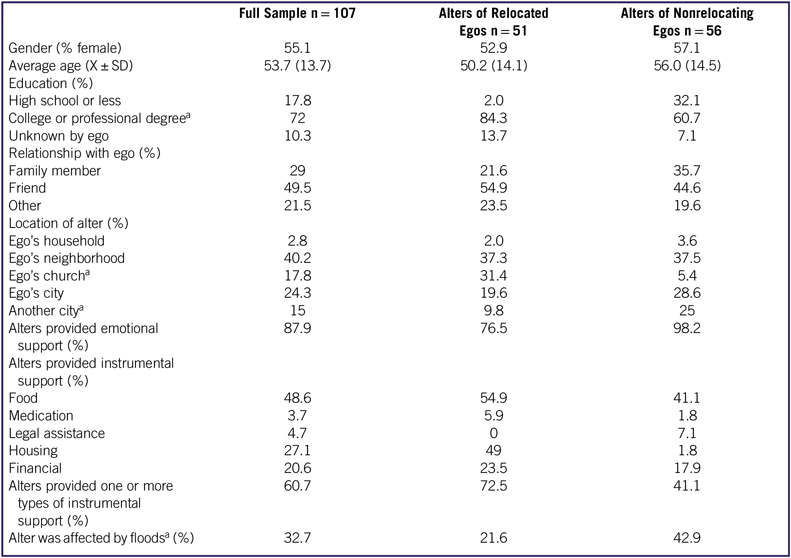

The sample characteristics of alters are shown in Table 2. There were 107 alters who provided flood-related support to CDE. Their average age was 53.7 years, and slightly more than half (55.1%) were female. A few alters (32.7%) were affected by the flood. Most alters (87.9%) provided emotional support to CDE. Additionally, 60.7% of the alters provided at least one type of instrumental support to CDE. Among the CDE who relocated, approximately 73% of their alters also provided at least one form of instrumental support. Food was the most frequent type of instrumental support that CDE reported that they received (48.6%).

TABLE 2 Characteristics of Alters Based on Relocation of CDE (or Egos)

Standard deviations are shown in parentheses for average values.

a Significant differences between alters of relocated egos (CDEs) and alters of nonrelocating egos (CDEs).

Significant differences existed between the social networks of older adults who relocated compared with those who did not relocate (Table 2). CDE who relocated had a larger proportion of alters with a college degree in comparison to the alters of CDE who did not relocate (z = 2.7; P = 0.007). Additionally, among CDE who relocated, a significantly larger proportion of their networks came from the church in comparison to the networks of CDE who did not relocate (z = 3.5; P = 0.0004). When compared with CDE who relocated, those who did not relocate had significantly more social network members living in another city (z = 2.1; P = 0.04). CDE who relocated had a significantly smaller proportion of social network members who were also affected by the flood (z = 2.3; P = 0.02). No other significant differences were observed between the social network characteristics of CDE who relocated and those who did not relocate.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Models

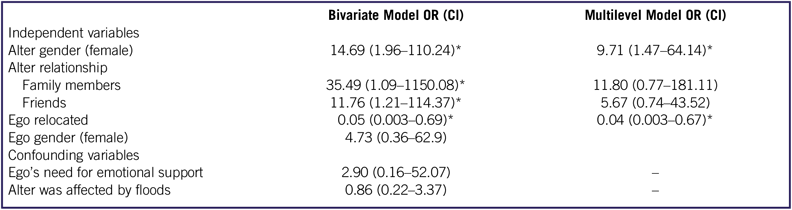

Emotional Support

Bivariate analyses indicated that CDE relocation, alter gender, and alter relationship were each significantly associated with emotional support (Table 3). Thus, all three variables were retained for the adjusted, multilevel model examining emotional support. This model showed that the odds of receiving emotional support were 9 times higher when the alter was female rather than male (P = 0.02). Additionally, the odds of receiving emotional support were 11 times higher if the alter was a family member, and 5 times higher if the alter was a friend in comparison to other acquaintances; however, the associations were not significant (P = 0.08 and P = 0.1, respectively). CDE who relocated were 96% less likely to receive emotional support in comparison to CDE who did not relocate (P = 0.02). Approximately 31.9% of the variance in emotional support was attributable to differences among CDE.

TABLE 3 Emotional Support Received by Egos:-Results From Bivariate and Multilevel Analyses

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

* P<0.05.

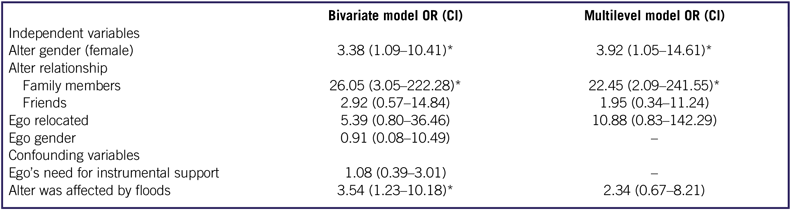

Instrumental Support

Bivariate analyses showed that instrumental support was significantly associated with alter gender, alter relationship (specifically being a family member), and whether the alter was also affected by the flood (Table 4). Thus, all three variables were examined in the adjusted, multilevel model for instrumental support. Although CDE relocation was not significant in the bivariate analysis (P = 0.08), it was retained for the model, because it was a main variable of interest. Results from the adjusted model showed that the odds of CDE receiving instrumental support were approximately 4 times higher if the alter was female rather than male (P = 0.04). The odds of receiving instrumental support were 22 times higher if the alter was a family member in comparison to other acquaintances (P = 0.01). For older adults who relocated, the odds of receiving instrumental support were nearly 11 times higher in comparison to nonrelocating older adults, although these results were not significant. Approximately 59.3% of the variance in instrumental support was explained by differences among CDE.

TABLE 4 Instrumental Support Received by Egos: Results From Bivariate and Multilevel Analyses

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

* P < 0.05

DISCUSSION

Regardless of whether they relocated or not, all but three CDE in our sample received instrumental and emotional support from various sources, including family members, friends, and others from the church. Although CDE who relocated had more alters from the church in comparison to CDE who did not relocate, this finding is in agreement with other research showing that the church is an important avenue for the provision of social support for older adults.Reference Roberto, Kamo and Henderson19, Reference Krause45, Reference Krause46 Additionally, considering the role that churches have played in providing emergency relief and humanitarian assistance,Reference Ferris47 it seems natural that these informal communities offered various forms of assistance to CDE who may have limited resources.

Compared with other acquaintances, family members were more likely to provide emotional and instrumental support to CDE in the study. The likelihood of receiving instrumental support from family members was significantly higher in comparison to receiving this form of support from other acquaintances. Evidence from previous research corroborates this finding about the role of family members in providing emotional and instrumental support.Reference Watanabe, Okumura and Chiu4, Reference Chung, Jeon and Song29, Reference Rosland and Piette48, Reference Shor, Roelfs and Yogev49 Older adults may feel more comfortable seeking support from these network members because of the potentially close ties they share. As Cohen and SymeReference Cohen and Syme50 have suggested, family members may also feel more obligated to provide support to CDE who may experience increased vulnerability during floods and other disasters. Consequently, a combination of both factors may explain why family members were more likely to provide support in comparison to other types of alters.

In comparison to male alters, female alters provided more emotional and instrumental support for CDE. This is consistent with previous research indicating that women are more likely to provide social support to network members. Reference Kawachi and Berkman26 , Reference Taylor27 In the current study, bivariate associations did not reveal any links between CDE gender and receiving social support; however, there is evidence that older females are more likely to receive flood-related support in comparison to older males. Reference Tyler22 It is possible that receiving support may be linked to one’s previous provision of support to network members, but exploring this concept was beyond the scope of the current study. Future research can potentially examine how support reciprocity functions among relocated and nonrelocating older adults in a disaster context.

There were differences in the availability of instrumental and emotional support within the context of CDE relocation. First, CDE who relocated were more likely to receive instrumental support in comparison to CDE who did not relocate, but this difference was not significant. Within a disaster context, instrumental support for CDE from family members was predominantly in the form of food. Many CDE indicated that they had legal, housing, and financial needs (Table 1). Few alters could provide support for those specific needs (Table 2). The current data do not provide clarity on how those needs were met, although they suggest that there may be a gap in what older adults need and what they receive from family, friends, and others within a disaster context.

Second, even though the findings showed that relocating CDE received significantly less emotional support in comparison to nonrelocating CDE, the level of emotional support provided for both groups of older adults appeared to be higher in comparison to instrumental support. Previous research has shown that family members are often a main source of emotional support, particularly among older adults. Reference Chung, Jeon and Song29 Thus, in the present study, even though friends were more prevalent within CDE’ social networks, family members were the ones who predominantly provided emotional support. Some scholars suggest that relocation may not necessarily impact access to emotional support among older adults Reference Wu, Penning and Zeng51 ; however, our findings were contrary to this as relocation was linked to less emotional support.

Relocation causes emotional distress as it interrupts routine activities in which individuals engage. Reference Xi, Hwang and Drentea52 Among relocating CDE in the current study, the frequency and type of communication with important alters may have changed, especially if those individuals were also flood-affected and could not engage or provide the same level of care or assistance as before. Consequently, the opportunity to receive emotional support either diminished or may have been lost after forced relocation. It is also possible that adjusting to a new home or environment brought its own set of challenges and stressors, which made it more difficult for some relocating CDE to engage in regular communication with existing supportive networks that were located elsewhere. Proximal network members have previously been linked to the provision of greater emotional support for older adults. Reference Seeman and Berkman41 Among relocating CDE in our study, not having confidants or important alters in close proximity may have further decreased the availability of emotional support.

The variance in instrumental support (59.3%) was nearly twice as high as the variance in emotional support (31.9%). The finding suggests that differences among older adults in our sample were more important for receiving instrumental support than for receiving emotional support, while differences among alter characteristics were more important for receiving emotional support than for receiving instrumental support. Older adults in our study may have received adequate levels of certain types of instrumental support in comparison to other types of instrumental support, so this may explain why differences in their characteristics were more important for receiving this form of support. It appears alter gender is influential as it is the only alter characteristic that increased the odds of receiving emotional support; thus, this may have been captured in the variance measure. Future studies can explore why differences among older adults and differences among alter characteristics may have unique effects on access to disaster-related, social support.

Our study has provided evidence that relocating and nonrelocating CDE have some important differences in social support needs and support received within a disaster context. However, the study has certain limitations. The small sample size restricts the generalizability of the results and the precision of the statistical estimates. Yet, because flooding and disasters often cause displacement, the strategy to collect data as close to the flood as possible contributed to richer and more comprehensive data. Additionally, the sample was not ethnically diverse, and CDE of other ethnicities may have had unique circumstances that influenced their access to social support. Because this was a cross-sectional study, it is possible that CDE may have received more support after being interviewed. Future studies on disaster-affected CDE may benefit from a longitudinal design that enables the tracking of additional types and sources of social support over time. It is also possible that alters may have provided more emotional support than CDE perceived.

CONCLUSIONS

As Watanabe and colleagues Reference Watanabe, Okumura and Chiu4 have indicated, social support that is most useful for postdisaster recovery must be timely, suitable, and from the right source. This study suggests that, for older adults, family members and other acquaintances give immediate assistance during and after a natural disaster. Specifically, family members and female network members tend to provide social support (emotional and instrumental support) to relocating and nonrelocating CDE within a flood context. However, there may be additional levels of ongoing support that CDE require to adequately overcome the effects of floods or other disasters over time, especially when relocation is mandatory. State and federal-level emergency preparedness protocols could include steps to quickly identify and provide timely and adequate social support to CDE who are in vulnerable social and economic positions or who have restricted access to social support networks during natural disasters.

Funding Statement

Funding for this study was provided by the University of South Carolina Office of the Vice President for Research through the South Carolina Resilience to Extreme Storms: Research on Social, Environmental, and Health Dimensions of the October 2015 Catastrophic Flooding funding initiative.