Principal-based strategies for mental health triage are needed during postdisaster emergencies when resources are limited.Reference Brandenburg and Arneson1 Identification and early intervention to address the mental health issues in disasters can help reduce negative sequelae and improve the quality of care.Reference Baren, Mace and Hendry2, Reference Shafiei, Gaynor and Farrell3 In both an emergency setting and a major incident, psychiatric and other triage tools have been shown to be successful, feasible, time-efficient, and accurate in prioritizing the allocation of resources.Reference Schumacher, Gleason, Holloman and McLeod4-Reference Culley and Effken6 For example, brief training in systematic rapid triage methods has allowed novice medical students to achieve triage accuracy scores similar to those of emergency physicians, registered nurses, and paramedics.Reference Petrie and Zatzick7 A conceptual model of the design and information necessary to support effective triage in mass casualty situations suggests that an emergent but managed structure to response is needed.Reference Sapp, Brice, Myers and Hinchey8

According to the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), rapid assessment identifies the most acute distressed survivors who need medical attention.9 Mental health disaster assistance may be practical or psychological in nature, and a dedicated mental health triage tool to use following medical triage may help disaster survivors receive needed mental health services in a timely fashion. The tools presented here are intended to provide a simplified, field-expedient method for immediate sorting and routing to available mental health services until more robust services are accessible.

The goal of this study was to determine the effectiveness of 2 field-expedient mental health triage tools in helping disaster responders (Medical Reserve Corps [MRC] volunteers, public health workers, and others) to correctly route medically triaged survivors to immediate medical attention, mental health services within 24 hours, psychological first aid (PFA) within weeks, or long-term public health surveillance.

Methods

Development of the Mental Health Triage Tools

In 2009 the National Association of County and City Health Officials, in conjunction with the National Child Traumatic Stress Network and the National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, sponsored PFA facilitator trainings for MRC unit leaders across the United States. PFA is designed to reduce the initial distress caused by traumatic events and to foster short-term and long-term adaptive functioning.Reference Brymer, Jacobs and Layne10 Evaluations of PFA have demonstrated the feasibility of providing training to staff to administer PFA during disasters.Reference Thienkrua, Cardozo and Chakkraband11

As part of the Greene County, Ohio, MRC program, training in PFA and medical triage was offered over 2 consecutive years to MRC volunteers, public health workers, and others. Two questions emerged from these trainings: Will a tool help in routing medically cleared disaster victims to needed mental health services? If so, what form should such a tool take: a flowchart or a scale? As a result 2 tools were developed by MRC volunteers and public health workers to help disaster workers efficiently route survivors to suitable mental health services. In the development of the tool and the scale, the need for parsimony to link the fewest number of mental health triage decision nodes to principles and to postdisaster survivor science was considered paramount.

The physiological response to mental stress is increased cortisol levels and is associated with coronary artery calcification in healthy persons.Reference Hamer, Endrighi, Venuraju, Lahiri and Steptoe12 One aspect of the tools’ development that is not included in other psychological triage systems is a temporal indication of past traumatic experience.Reference Adams and Boscarino13 In a seminal meta-analysis of postdisaster psychopathology, the predictors of mental status of disaster survivors was reviewed, but the preexisting mental health status was not evaluated.Reference Rubonis and Bickman14 However, the researchers found that the number of weeks since the event was predictive of the effect size of the post-disaster psychopathology. Even attenuated mental health symptoms may be predictors of later mental health status, especially within one year, and even later.Reference Werbeloff, Drukker and Dohrenwend15 A growing body of evidence suggests an interaction between the time since last psychopathological impact, the presence of comorbidities, and the experiential effect of the current disaster, including the responsibility of the current event, whether natural or human cause, and the number of deaths observed.Reference Rubonis and Bickman14

While pediatric susceptibility to postmental health effects appear to be linked to family resilience, vulnerability factors for disaster-induced mental health effects increase with age.Reference Seng, Graham-Bermann, Clark, McCarthy and Ronis16-Reference Fan, Zhang, Yang, Mo and Liu18 An increased percentage of psychiatric disorders has been associated with asthma severity in emergency department asthmatic patients with no psychiatric diagnosis.Reference Feldman, Siddique, Morales, Kaminski, Lu and Lehrer19 Traumatic medical events and sequelae can have an inherent psychopathological impact; others, if well controlled, would have no physiological basis to increase vulnerability to adverse mental health effects. In the development of the tools, the allocation to high-priority mental health follow-up, in the presence of a medical comorbidity, was considered discretionary.

The Fast Mental Health Triage Tool (FMHT) (Figure 1) and the Alsept-Price Mental Health Scale (APMHS) (Figure 2) were designed to improve mental health triage performance. Both tools screen for the ability to follow simple commands; the presence of chronic medical conditions, occult injuries, or diagnosed mental health conditions; access to prescribed psychiatric medication or psychological services; and a history of traumatic events in the past year.

Figure 1 Fast Mental Health Triage Tool.

Figure 2 Alsept-Price Mental Health Scale.

The tools were adapted from approved medical triage and PFA trainings and reviewed by mental health and other medical specialists. In addition, they were developed to be consistent with the standards recommended in the US DHHS’ Mental Health Response to Mass Violence and Terrorism: A Training Manual. 9 For instance, mental health specialists may inquire about event-related traumatic experiences, which would not be especially advisable for untrained responders to conduct in the immediate aftermath of a disaster. These tools are designed for use after disaster victims have been medically triaged to a safe green zone where the incident command system does not yet have enough mental health services immediately available.

The FMHT was designed by public health workers as an algorithm that screeners follow to triage survivors to recommended mental health follow-up time frames. The APMHS was designed by MRC volunteer nurses to score survivors’ answers to screening questions and triage them to a recommended follow-up schedule.

Raters

MRC volunteers and public health workers not involved in the design of the tools provided the pool of raters. All raters began the survey with a baseline task of completing 10 clinical vignettes without the use of any tool. They then triaged 10 clinical vignettes in sequence using the FMHT flowchart, the APMHS, or no tool to assist them with mental health triage. These 3 conditions are here after called “the tools.” The raters used the tools in their review of the clinical vignettes to assign survivors to immediate medical treatment, mental health follow-up within 24 hours, PFA within weeks, or long-term public health surveillance. MRC volunteers (n = 204) and public health workers (n = 66) were randomized into 3 groups; of these, 79 chose to participate.

Fifty-nine raters triaged or completed 20 each of 1180 mental health clinical vignettes of disaster survivors. In compliance with federal regulations, this research met the requirements for the policy of exemption of institutional board review, because it is research that examines the public benefit of the effectiveness of training programs for the MRC volunteers and public health workers, who are considered to be experts in the areas evaluated by the tools. Further, this evaluation is distinguished from nonexempt research because it is focused on public health practice in protecting the public's health through programmatic evaluations by a public health authority, under a duly appointed board of health.Reference Hodge and Costin20

Study Design

The study was a baseline run-in, random crossover design. The 2 phases of the study consisted of a baseline and random assignment to 1 of 3 experimental conditions. The experimental conditions consisted of raters using 1 of 2 mental health triage tools, or no tool, to triage disaster survivors. Twenty clinical vignettes of disaster survivors who had been appropriately medically triaged to the green zone were presented to raters randomly assigned to an experimental condition. Each clinical vignette was designed by MRC volunteers using the tools to provide the pertinent presentation of decision nodes to allow for only one correct answer per case. Since each rater evaluated 10 clinical vignettes at baseline and 10 in the evaluation period, the proportion of outcomes was selected based on the number of mental health issues expected to present. If all of the clinical vignettes were chosen correctly, this would result in the following: 40% of clinical vignettes would be assigned to PFA referral, 30% would continue long-term public health surveillance, 20% would be referred to mental health services within 24 hours, and 10% would be sent for immediate medical reevaluation. The baseline phase, which included 10 different clinical vignettes, was the same for all of the raters. The next 10 cases, numbers 11 to 20, differed between experimental conditions in the triage tool provided. The first experimental condition was the APMHS; the second experimental condition used the FMHT flowchart; and the third group was given no tool.

The surveys were conducted using an online methodology. The subjects were randomly assigned to receive 1 of the 3 experimental conditions and were given only the corresponding link to complete their respective Internet-based surveys.

Statistical Methods

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Version 19. The raw data responses were coded as 0 and 1 for internal consistency, because unidimensionality of measurement scales was a requirement to check for internal consistency and reliability. Guttman split-half coefficient was calculated using the formula for Cronbach's alpha for 2 items to estimate reliability of the survey used to evaluate the scales. Cronbach's alpha coefficient is important to consider when aggregate scores across multiple items are evaluated, such as in this evaluation in which baseline versus experimental conditions are compared, and between the triage tools within the experimental study phase. Cronbach's alpha usually ranges from minus infinity to 1, with scores closer to 1 showing internal consistency of the items. The reliability alpha level set for this study was that 0.7 was acceptable and 0.5 was unacceptable.

The baseline and experimental conditions (or treatment phase) provided a split point to compare these groups as if they were 2 separate administrations of the same survey. Splits of the questions that were justified as highly correlated responses should be paired between splits. The questions between the baseline and treatment varied only in their details, not in the ideal triage assignment or in the presence or absence of the randomly assigned mental health triage tool. Guttman's lambda reliability statistic was used to provide the lower bound for the true reliability for the split of the test. The parallel model hypothesized that the surveys’ baseline and treatment scores are parallel or have the same mean and variance. The reliability of scorers to rate the survivor's mental health triage in the same pattern as other raters was examined using a measure of interclass correlation. For the evaluation of interclass correlation, the data were transposed with 74 raters as variables with the 1480 survivors as cases.

The raters’ experience and the courses taken on medical triage and PFA were stratified by percent correct. The standard error and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. The baseline values were compared using a one-way analysis of variance to ensure that randomization was successful in spite of having unequal numbers in each arm. An analysis of covariance was conducted after exploratory analysis to determine if there were significant interactions. While the interaction of the tool available and triage experience was significant, the resulting stratum was too sparse to be useful in subsequent analysis. The main effects model across the groups in the treatment phase was conducted using the percentage of the victims triaged to the appropriate mental health services.

Sample Size

In estimating the required sample size, the proportion of clinical vignettes assigned to each triage category was estimated from known proportions of mental health presentations to a metropolitan emergency department.Reference Shafiei, Gaynor and Farrell3 The triage mix presented in the clinical vignettes of persons medically triaged to green was identical among the experimental arms of the trial. Poisoning, intoxication, drug withdrawal, suicidality, psychosis, or schizophrenia would ideally be considered a medical emergency and not be medically triaged green. Any residual cases of, for example, suicidal ideation or psychosis, would need immediate medical service. Depression without any other factors would be designated for mental health services within 24 hours (mental health triaged red). Survivors with psychosocial or situational disorders or those needing a psychiatric examination were deemed to need mental health services within a month. Persons with other health conditions or no mental health diagnosis were coded as not requiring a specific mental health referral. Not including the non-mental health persons who would make up approximately 95% of the population, the hypothetical proportions of mental health triaged cases to mental health service within 24 hours should be 10%. Sixty percent should be seen as soon as possible within weeks, and 30% should require no mental health referral. The discharge-diagnosis proportions were adjusted so that each rater would be presented with a batch of cases to evaluate, in which 10% would be mental health triaged back to medical, 20% would be mental health triaged to red (within 24 hours), 40% would be triaged to yellow (scheduled a mental health referral within a month), and 30% would not be scheduled a mental health referral. The sequential presentation of cases to raters is a research construct of a nested sample among a vast majority of non-mental health persons who have also been medical triaged to green. While the allocation of triage types approximates the proportions of real world mental health cases, the proportions were slightly adjusted so that skill at differentiating cases could be efficiently tested. For example, 1 additional case of 10 per study phase was assigned to the red mental health category to test the ability of the raters to adequately assign persons to the red category.

A sample-size calculation with a frequency of 70% correctly triaged cases showed that 51 raters would provide a 95% confidence limit and 57 raters would provide a confidence limit of 99.99%. MRC volunteers (n = 204) and public health workers (n = 66) were randomized into 3 groups with 79 choosing to participate; 5 of these were incomplete; 15 had partial data. A total of 59 raters triaged/completed 20 each of 1180 mental health clinical vignettes of disaster survivors included in the final model.

Results

Reliability

The presentation of the reliability results are followed by the statistical tests of reliability and inter-item correlations. No indication of subgroups of respondents affecting the pattern of responses was identified. Specifically, no clusters exceeded 30% either overall or among the experimental conditions. When comparing the pattern of responses in the experimental phases to those at baseline, the percent correct was similar at baseline between groups and higher from baseline to experimental phases. The standard errors, however, were smaller, suggesting that the clinical vignettes did a good job at differentiating the knowledge of the evaluators. Showing that the distribution of types of clinical vignettes was largely independent in the information presented and in testing the experience and professional category of the evaluators (Table 1); only 3 of 45 baseline and 7 of 45 inter-item correlations were greater than 50%.

Table 1 Professional Category by Experience of Evaluators Included in Final Analysis

Abbreviations: EMT, emergency medical technician; ER, emergency department; PFA, psychological first aid; RN, registered nurse.

The lower bound of the survey's reliability was indicated by a Cronbach's alpha of 0.892. The Cronbach alpha for baseline and treatment phases were 0.793 and 0.864, respectively. The Guttman split-half coefficient (also called lambda 4) was 0.771. The baseline and treatment surveys had a goodness of fit of 1.000, indicating that there was no statistical reason to reject the models. The reliability of the raters to make similar observations of the same event was highly significant: for 1480 observations, the average of 74 raters of clinical vignettes of 20 disaster survivors was highly reliable, with an interclass correlation of 0.852 (interval of 0.743 to 0.931 with 95% confidence). In summary, the reliability statistics of the survey presenting the clinical vignettes was acceptable at 0.771; the study design was robust, the model was parallel, and the interclass correlation among raters was good at 0.852.

Baseline Comparisons

Baseline clinical vignettes of disaster survivors were evaluated by the raters before the mental health triage tools were randomly provided. The baseline used no tools, so the amount correctly triaged should have been relatively low. For example, the percent correct of a fair choice of selecting the right triage is 25% without other prior knowledge; however, the comparison within baseline subcategories was presented to highlight similarities (not differences) to further validate the randomization process. No significant difference was found between licensed medical professionals (registered nurse, licensed practicing nurse, physician assistant, or emergency medical technician) versus non-licensed persons on the baseline percent correctly triaged to mental health services: 49.4% (95% CI 41.6 to 57.1; n = 31); 52.9% (95% CI 38.9 to 67.6; n = 28). Two emergency medical technicians (EMT) and one emergency department (ER) worker had the highest baseline correct: 73.3% (95% CI 59.0 to 87.7; n = 3), compared with everyone else: 49.8% (95% CI 45.0 to 54.7; n = 56). No differences were noted among occupational categories (allied health, n = 4; medical, n = 27; mental health, n = 27; public health, n = 18; and others, n = 7) in the number of baseline vignettes correctly triaged to mental health services.

The courses taken by the MRC volunteers and public health workers in PFA and in medical triage had no effect on baseline scores of mental health triage. Self-rated experience in PFA or in medical triage also was not significantly different at baseline, in spite of the fact that self-rated experience in the mental health field predicted having more cases correctly triaged to mental health services: 56.1% versus 45.4% (P < .05); the Levene statistic accepted the null hypothesis that the baseline group variances were equal (P = .237) between randomization arms, allowing for comparison between triage tool groups.

Comparison of Experimental Conditions

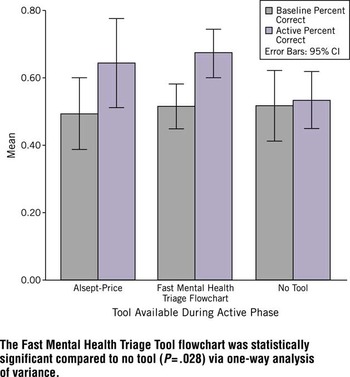

Based on the exploratory analysis of the baseline values, the variables included in the model were the randomly assigned tool available during the active phase, the level of triage experience, and the level of mental health experience. The within-subject effect of the baseline and active phase was significant for study phase and by the interaction of study phase by tool by triage experience (Table 2). The between-subject effect was significant for the tool used to provide a field expedient mental health triage (Table 3). The one-way analysis of variance of the tools used reached a trend level of significance for the number of medically cleared disaster victims correctly triaged to mental health services: F(2, 56) =2.638, MSE = 0.101, P = .080. Table 4 shows that the FMHT flowchart was significantly better than no tool in helping allocate survivors to the correct mental health services. During the one-way analysis of variance of tools, use of the FMHT flowchart increased the number correctly triaged over no tool (P = .028). Figure 3 shows the percent correctly assigned for the baseline vs the active phase by which tools were available to the raters: no tool (baseline 51.8% to 53.5% no tool), APMHS (baseline 49.4% to using the scale 64.4%), and the FMHT (baseline 51.5% to using the flowchart 67.3%).

Table 2 Within-Subject Effects of Baseline Study Phase

Table 3 Between-Subject Effects of Mental Health Assessment Triage Tool

Table 4 One-Way Analysis of VarianceFootnote aFootnote b

a Effect of three assessment tool conditions on the amount of medically cleared disaster victims correctly triaged to mental health services.

b Mean difference is significant at the .05 level.

Figure 3 Comparison of Average Scores per Assessment Tools Used to Provide Mental Health Triage for Medically Cleared Disaster Victims.

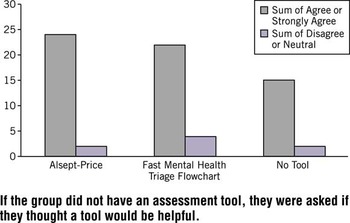

Figure 4 shows that the study subjects predominantly agreed that the tools were helpful in triaging the survivors to the appropriate mental health conditions, with 61 of 69 raters agreeing or strongly agreeing that the assessment tool was helpful. If the group did not use an assessment tool, they were asked if they thought such a tool would be helpful.

Figure 4 Total Number of Subjects Who Agree or Strongly Agree That the Assessment Tool Was Helpful.

Comment

Both PFA and the triage tools were designed for use by either mental health professionals or non-mental health professionals. The objective was to consume fewer professional mental health resources during the initial phase of disaster response, allowing those with advanced training to concentrate their skills on those in the greatest need. After initial screening, certain survivors may be referred to PFA, similar to other mental health field triage systems.Reference Brown, Bruce, Hyer, Mills, Vongxaiburana and Polivka-West21 The tools in this study were designed to be used as field-expedient tools for use after medical triage to augment and not replace PFA. For instance, it is not necessarily advisable for psychologically untrained responders to ask about events related to traumatic experiences in the immediate aftermath of a disaster. The mental health triage tools intentionally do not address the psychological impact of the survivor's disaster experience. Care must be taken not to evoke or trigger an acute traumatic reaction but rather minimize the effect of the disaster.

The clinical vignettes were pared to their essential elements to allow for customizing each client presentation in the vignette. Our anecdotal and empirical observations showed that clinicians who present triage tend at times to veer off to treatment. In one example of the elusive search for diagnostic perfection, a few simple questions along with an electrocardiogram are, on average, better in the triage of chest pain in emergency settings than individual diagnosticians.Reference Goldman and Kirtane22 One reason are the myriad data clouding essential details, preventing correct triage of the case. Our development goals were parsimonious in the number of decision points, the association of skills essential to rapidly evaluate multitudes, and the efficacious allocation to the correct triage schemes. The ethical principle of not doing maleficence prevents testing the research construct of the clinical vignette in the real world. However, future studies could incorporate a retrospective design to test the impact of the tools on real life mental health outcomes in a disaster.

Because the participants in this study represent a cross section of disaster personnel, it seems reasonable to expect the results to generalize to other disaster response personnel. Those participating in this study either responded to disasters in their roles with the medical system, MRC, public health, disaster medical assistant teams, or citizen's corps. They were nurses, physician assistants, emergency medical technicians, mental health workers, allied health professionals, public health workers, and concerned citizens. The baseline results across categories were similar, except as noted, for the several emergency responders with higher baseline scores. The effect of occupational category on baseline percent correctly triaged showed that the EMT or ER worker scored the highest, while mental health professionals had lower scores of those correctly triaged. In contrast to carefully constructed, long-term mental health treatment paradigms, mental health triage uses quick, simplified, decision-making processes over the fewest decision points. The reasons to include an exploration of professions are first to determine the effect of covariates in the model and the final factors that were allowed in through the steps of the modeling process and to see the applicability to other MRC and public health workers who may benefit from using augmentation of mental health triage before their disaster response. Also, no significant differences were found between experimental groups at baseline, which adds credence to the generalizability of these results, as the randomization seems to have worked. A limitation is that the randomization had unequal arms, but no difference in variance was shown across baseline conditions. This finding permitted continuation of comparisons between baseline and the experimental conditions when the randomly assigned triage tools were used by the evaluators to provide mental health triage.

There was resounding agreement that the tools would be helpful in live disaster situations. This finding was especially true for those less experienced in mental health triage. Tool helpfulness and effectiveness should be congruent to provide for the best optimal response during public health emergencies.

The training evaluations of the medical triage and PFA courses for public health workers and MRC volunteers were uniformly positive. However, course work in medical triage and in PFA did not seem to transfer to the ability to correctly conduct mental health triage. This finding suggests that mental health triage is a separate set of skills, knowledge, and abilities that could benefit from its own dedicated tool. Nonetheless, those with greater self-reported disaster experience did better on the triage task, lending support to the validity of this study.

The assumptions specific to the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) were that the covariate and dependent variables within baseline and assessment phases were linear. The within-group residuals were normal and the slopes across groups were parallel. The ANCOVA allowed for statistical control in place of the lack of experimental control of the scale-level variables that otherwise would potentially affect the outcome. Another purpose was to obtain a more sensitive analysis of variance (ANOVA) by reducing the within-group variability. The ANCOVA was conducted on baseline and active phases, showing the effects during each phase. Then the one-way ANOVA was conducted overall. The presentation of these 3 analyses builds an incremental powerful argument to accept the results of the ANOVA.

While enough statistical power was available to detect differences between the experimental tools, when the baseline results were stratified by professional class or occupational category, the power to detect true differences was diminished. The public health occupational category had the fewest correct at baseline. It is not that the trainings were failures; rather the need for practical experience in applying the newly acquired knowledge is suggested. In the medical triage course, there were extensive hands-on simulated victims with moulage, and the participants were coached through the disaster scene by expert triage trainers. An explanation for the lack of an effect from PFA and medical triage courses on mental health triage is that those courses do not apply directly to a field-expedient method, because they are not necessarily stand-alone tools but systems. There is a need for principle-based strategies for mental health to be part of an overall system for medical and mental health triage.Reference Brandenburg and Arneson1, Reference Culley and Effken6

Another surprising effect was that nurses had the lowest baseline scores (although nurses who had triage experience scored the highest). In the report-out sessions during the medical triage training course, one observation was that nurses who were not experienced in triage had to overcome their innate training to provide needed medical care rather than limiting their actions to triage. The nurses did as well as other occupational groups outside of the EMT or ER workers. This finding is important because the vast majority of the MRC volunteers in this study were nurses. The significant effect of previous mental health field experience provides evidence that more training is needed in disaster event-based fast mental health triage for public health workers and MRC volunteers.

Recommendations for Future Research

The role of this research was to evaluate mental health triage and to make it available to the public. It is unclear now whether parts of the tool can be incorporated into other preexisting mental health systems or if it will be a stand-alone tool. Comparison to other triage paradigms is warranted. For example, the PsySTART field triage tag would present a reasonable comparison, as this mental health triage system may have different efficacies across disaster types. To determine whether mental health triage is a separate set of skills, knowledge, and abilities, a study could randomly administer mental health triage training to half of the MRC volunteers, and then test all of the students in mental health triage. Using retrospective data in a reality simulation with either the FMHT flowchart or PsySTART field tag could test the effectiveness of training to real life mental health outcomes in a disaster. The variance between the flowchart and the field tag could be evaluated, understanding that the 2 systems do not have to be mutually exclusive. Indeed, the field tag could be modified if the temporal component in the flowchart was found to significantly improve outcomes.

Other researchers have started exploring how PFA could be adapted to nursing home residents.Reference Brown, Bruce, Hyer, Mills, Vongxaiburana and Polivka-West21 One pilot study demonstrated that mental health disaster services can be adapted to special populations, suggesting other avenues for future research. Finally, retrospective evaluation could focus on what worked in the management of a mental health disaster response. For example, it could be interesting to explore what allocation of available mental health and non-mental health professionals is needed to balance resources with health outcomes.

Summary

Self-rated experience in mental health is predictive of better performance in baseline fast mental health triage. The FMHT flowchart was more useful (P = .039) than the APMHS and was better than no tool (P = .028) in correctly triaging the medically cleared survivors to the correct mental health services. The FMHT flowchart improved baseline mental health triage scores from 51.5% to 67.3%. Over 88% of public health workers and MRC volunteers agreed or strongly agreed that a mental health flowchart or scale assessment tool was or would be useful. The significant effect of past mental health field experience provides evidence that more trainings are needed for public health workers and MRC volunteers in disaster event-based fast mental health triage. Mental health triage is a separate set of skills, knowledge, and abilities that benefits from a tool. The incorporation of a temporal component should be evaluated for potential inclusion in existing mental health triage systems.

About the Authors

Unit Coordinator, Greene County Medical Reserve Corps (Mr Brannen) and Greene County Combined Health District (Mr McDonnell and Ms Caudill), Xenia; Yellow Springs Psychological Center, Yellow Springs (Dr Barcus); and Sinclair Community College, Dayton (Mss Price and Alsept), Ohio.

Support

This study was supported by the Greene County Combined Health District. Some of the content the raters evaluated was sponsored through a capacity building award from the National Association of County and City Health Officials.

Published online: October 29, 2012. doi:10.1001/dmp.2012.49