“…the failure of telecommunications infrastructure [during a disaster] leads to preventable loss of life and damage to property….Yet despite the increasing reliability and resiliency of modern telecommunications networks…the risk associated with communications failures remains serious because of growing dependence upon these tools in emergency operations.” —Anthony M. Townsend and Mitchell L. MossReference Townsend and Moss 1

Communication is essential to patient care and important for coordinating responses and allocating resources during major disasters. 2 , Reference Richards 3 One consequence of major disasters is a surge in patients and requests for health care services.Reference Tran and Pedler 4 , Reference WS and PG 5 Yet studies indicate that during such emergencies, 10% to 40% of hospital staff may be out of touch because they are incapacitated by the event, unable to contact the institution, or cannot get to it.Reference Chaffee 6 , Reference Stergachis, Garberson and Lien 7 Therefore, medical facilities may need to operate at higher service levels with fewer personnel. When communications are disrupted in a disaster, managers in health care settings may lose the ability to request help and resources, maintain situational awareness, coordinate assistance, maintain leadership coordination, or gather information for decision-making.Reference Richards 3 , Reference Wohlstetter 8

Although valuable communications lessons have been drawn from the severe impact of Hurricane Katrina and 9/11,Reference Wohlstetter 8 disasters continue to affect the ability of health organizations to communicate during disasters. For example, in 2011 a tornado devastated the town of Joplin, Missouri, including St. John’s Mercy Hospital. Phone lines were down, electricity was out, and even emergency generators were inoperable.Reference Carter 9 In 2012, Hurricane Sandy hit the coast of New Jersey and created a 250-square-mile communications blackout zone that lasted several days.Reference McKay 10

The reasons for telecommunications failures during disasters are numerous. Telecommunications relies on complex infrastructure. Maintaining redundant systems or resilient commercial alternatives is often prohibitively expensive. Damage done to a telecommunications system during a disaster may be extensive and restoration of service may be time-consuming and expensive and require specialized resources and skills. The solution developed by the National Library of Medicine (NLM), the Bethesda Hospitals’ Emergency Preparedness Partnership (BHEPP)–Army Military Auxiliary Radio System (Army MARS)–assisted Emergency Radio System, or BMERS,Reference Cid and Mitz 11 , Reference Conuel 12 supports the functioning of a health care facility during major emergencies by providing emergency managers and health care staff a mechanism by which to communicate under extreme conditions. BMERS combines Wi-Fi, specialized software, and current amateur radio technologies to provide an email service for medical staff when normal telecommunications systems have failed or are compromised. Through BMERS, email messages can be sent and received via the Internet by reaching beyond a communications blackout zone that may extend from a few to hundreds of miles. The system also keeps key incident management personnel at medical facilities connected via a low-cost, rapidly deployable intranet. BMERS does not enhance communications and medical care, but it can preserve them at a time when normal communications are severely disrupted. This article introduces the BMERS emergency communications technology and provides guidance for implementing it at medical facilities.

THE BEGINNINGS OF BMERS

Creation of BMERS by the NLM began in 2008 as a research and development project for BHEPP. 13 BHEPP is the first military-civilian-federal partnership in the United States and comprises the National Naval Medical Center (which was replaced in 2011 by the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center, the Suburban Hospital–Johns Hopkins Medicine, and NLM. Experts at NLM’s Disaster Information Management Research Center (DIMRC) were tasked with designing an emergency backup communication system to support the 3 allied hospitals in BHEPP during emergencies. BMERS has much broader applications, however, because it supports the function of the Hospital Incident Command System (HICS) used by hospitals throughout the country to manage threats, planned events, and emergency incidents that present significant risks to the facility and its occupants. In emergencies, the HICS facilitates sharing of resources and management of patient surge, but coordination among the hospitals can only be effective if the organizations can communicate.

The overarching objective of the project was to develop a cost-effective, easy-to-use, and adaptable telecommunications solution that can be employed by Incident Command staff at medical facilities for exchanging information efficiently during severe disasters (Table 1). The developers at NLM/DIMRC hypothesized that digital amateur radio could fill a key communications gap for BHEPP hospitals because it does not have the burdens of commercial solutions and has a proven record of service during disasters (Table 2).Reference Zuetell 14 - Reference Palm 21 Unlike satellite-based solutions,Reference Bowman, Graham and Gantt 22 , Reference Nagami, Nakajima and Juzoji 23 digital amateur radio does not require service subscriptions or pay-as-you-go service fees for access. BMERS does not require roof-mounted equipment, as would be the case with commercial radio systems. It also does not involve additional infrastructure, institutional licensing, or permits, which are typical requirements of commercial wireless telecommunications services.

Table 1 Goals of the BMERS ProjectFootnote a

a Abbreviations: HCC, hospital command center; HICS, Hospital Incident Command System; MARS, military auxiliary radio system.

Table 2 Benefits of Using BMERS for Last-Resort Communications During Disasters

Use of amateur radio in medical facilities is not new but rates of adoption remain low because commercial communications products and services are ubiquitous and there is insufficient motivation to maintain redundant telecommunications.Reference Zuetell 14 , Reference Farnham 16 , Reference Petrescu and Toth 24 However, new emergency preparedness requirements in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services rules could provide additional incentives for US medical facilities to consider amateur radio in their disaster plans. 25

The United Nations International Telecommunications Union and governments around the world recognize the value of amateur radio and allocate frequency bands throughout the electromagnetic spectrum for licensed amateurs to advance the art, science, and public benefit of radio communication. Other volunteer-based radio communications services that can play a supporting role during disasters, such as Army MARS, 26 have additional frequency allocations for properly credentialed volunteers. The BMERS system can be adapted to these other services if necessary.

Radio amateurs must obtain a license to operate radio transmitters. Licensing involves passing an examination on radio theory, regulations, safety, and operating practices. The United States has an incentive licensing structure to encourage proficiency, which typically is acquired by peer training and operating experience. Specialized training and credentialing in emergency communications is available from organizations such as the American Radio Relay League (ARRL). 27

TECHNOLOGICAL AND HUMAN CHALLENGES

The technological disadvantages of using digital amateur radio for disaster communications include its very slow data rate speeds due to US federal government bandwidth regulations. Data rates are also limited by transmitter power and technical limitations of radio propagation through the atmosphere. Radio equipment must be operated by a Federal Communications Commission (FCC)-licensed amateur radio operator (informally called a ham radio operator). With a unique professional collaboration and specific hardware and software, however, the BMERS developers were able to manage these limitations to provide an effective solution.

BMERS improves upon previous amateur radio models for providing emergency communications at hospitals. With the traditional model, the Incident Command staff at the hospital complete standard messaging forms that are handed to a radio operator for transmission. Analogously, messages that are received at the hospital via radio are transcribed by the radio operator onto a standard form that is handed to the local Incident Command staff. Communications follow the same telegram-like protocol reminiscent of early Morse code operations, which is laborious and can be error-prone. Not all radio operators are familiar with medical terminology and logistics, which may hamper manual handling of messages. To eliminate the radio operator bottleneck, BMERS developers looked to Winlink 2000 (WL2K).Reference MacDonnell 28 - 30 The Amateur Radio Safety Foundation developed WL2K in 1999 as a free messaging system for ham radio operators. It is both a technology and an infrastructure that provides radio interconnection services, automatic routing of email with attachments, geolocation, graphic and text weather bulletins, and emergency relief communications. More than 100 automatic radio access points for WL2K exist across the United States and worldwide. Although the infrastructure of WL2K is supported by volunteers, its effectiveness in real disasters has been documented repeatedly. 30 These access points support the full range of amateur radio frequencies (medium frequency [MF], high frequency [HF], very high frequency [VHF], and ultra high frequency [UHF]) that, as a group, maximize the data bandwidth for a given communications distance.

The WL2K system was originally designed to allow a single licensed radio operator to send and receive email messages via radio using the manual transcription process described earlier. The BMERS system re-envisioned the radio operator’s role. In this new incarnation, radio exchange of email becomes a service that meets the needs of Incident Command staff. The amateur radio operator becomes the manager of the service but is not directly involved with message exchange.

The next challenge was to identify personnel who could be trained to operate the software and radio equipment required to connect with WL2K during a disaster. Most emergency personnel in hospitals are not ham radio operators. WL2K technology requires that operators have sufficient practical experience with ham radio technology, and relying solely on enthusiasts from the community was not the best option, because only a minority have the necessary skills. Often, the skilled operators are already committed to other support operations during disasters. It was essential to find or create a separate pool of reliable, trained radio operators available during emergencies. The solution was to collaborate with Army MARS 26 and the NIH Radio Amateur Club (NIHRAC). 31 Both organizations committed to this undertaking and have provided experienced emergency communications operators.

Army MARS is a Department of Defense program that trains, organizes, and tasks volunteer amateur radio operators with the mission of providing contingency radio communications to Department of Defense and priority civil authorities. Through the alliance with Army MARS, the BMERS system gained access to technology usually beyond the reach of most amateur radio operators. Army MARS also has its own exclusive set of WL2K resources nationwide, which became the primary resources used by BMERS.

The NIHRAC was founded for the purpose of providing emergency communications to NIH. The organization has a natural vested interest in supporting the project because the NIH Clinical Center is part of the BHEPP organization. The NIHRAC’s members also brought to the project a high degree of technical expertise, and Army MARS staff had significant experience building reliable custom radio communications solutions for rugged conditions using amateur radio technology. By partnering with NIHRAC and Army MARS, and later other amateur radio groups, BMERS gained access to enhanced technology and skilled human resources for developing the system and provided communications operators to support hospitals during times of crisis.

BMERS COMPONENTS AND PROCESS

The collaboration with Army MARS resulted in the creation of an enhanced model for use of amateur radio in disaster communications. With BMERS, end users send and receive emails without any direct radio operator intervention by integrating custom and commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) software, a local Wi-Fi/Ethernet local area network (LAN), and other COTS communications devices. The BMERS radio operator establishes radio links and maintains the email service, much like other modern information technology systems. Message content is managed by the user and through a rule-based system that elicits efficient use of the communications resources.

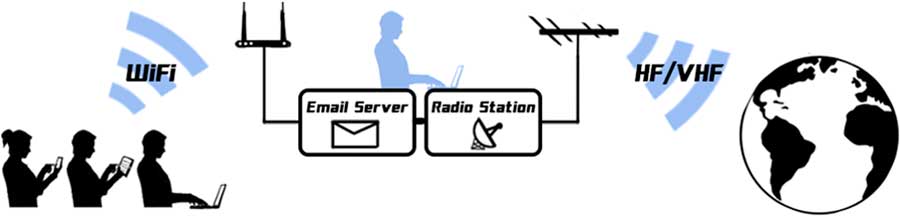

Figure 1 and Table 3 illustrate the service architecture of a BMERS station. A portable version of BMERS can be deployed and activated at a moment’s notice to provide user accounts and web email access to laptops or other computer devices connected to a LAN provided by the BMERS system in the hospital. A ruggedized laptop powered by a gas generator, batteries, or the power grid serves as the computer server and the operator’s console. BMERS operates on MF, HF (both long range), and VHF (short range/higher bandwidth) amateur radio and Army MARS frequency bands. Because MF and HF share a similar set of technical constrains, for most of the remaining of this article we use HF to refer to both MF and HF bands.

Figure 1 BMERS Bridges the Communications Gap During Disasters.

Table 3 BMERS Portable Station ComponentsFootnote a

a Abbreviations: HF, high frequency; VHF, very high frequency.

BMERS also can be connected to an existing LAN to provide resilient communications services to anyone using that network. For example, at NIH, a BMERS server is connected to a private high-speed network that interconnects the 3 hospital command centers of the BHEPP hospitals. The HICS staff from the 3 hospitals can use the BMERS server to exchange email and text messages with each other (intranet service) and to communicate via email with the rest of the world when institutional Internet services fail.

In advance of an emergency, the BMERS operator creates and assigns an email account to each HICS role, such as the Incident Commander and the Public Information Officer. Only authorized users can access the service.

To communicate during an emergency, authorized users at a hospital’s command center assume their designated HICS roles, access the email accounts for those roles as assigned by the Incident Commander, and point their web browsers to the BMERS mail server. The users do not need FCC amateur radio licenses and they require only minimal training. The web-based design of the user interface offers a familiar web mail look and functionality. Hospital command center personnel can access BMERS with any Wi-Fi or Ethernet-capable device (personal computer, laptop, tablet, or smart phone) that can run a standard web browser. No additional software or special equipment are needed, only the BMERS email credentials provided by the station operator. Additionally, BMERS provides powerful but simple-to-use system management tools to the radio station operator.

BMERS FUNCTIONALITY

The user interface, shown in Figure 2, is intuitive to anybody who has used web-based email. If the facility prefers to use formal emergency communications methods, the interface also includes common ICS forms. To send email to a recipient outside the hospital, a hospital command staff member presses a “New Radio Message” button on the web mail page, which provides access to the WL2K service via a familiar email composing interface. Outgoing messages have the local user’s email address embedded in the body text and include instructions telling the recipient how to reply. When an individual addresses a reply properly, it is received through WL2K and automatically ends up in the original hospital command center user’s mailbox. Thus, the radio operator is not directly involved with mail content or delivery. Only one operator is needed to serve multiple groups of end users. This is a new model for WL2K and represents a vast improvement in trained radio operator utilization during disasters. In our test system, the user-to-radio operator ratio can be 10:1 or greater.

Figure 2 BMERS User Interface.

BMERS provides an integrated communications service for local and long-distance communications. For local communications, BMERS enables hospital command center users within a hospital to exchange emails among themselves or with a group of hospitals associated with the BMERS system via wide-area network (WAN) technology such as a long-distance Wi-Fi system. Hospitals in close proximity in Bethesda, Maryland, have used a private wireless network to share a single BMERS system this way. That system can handle a virtually unlimited number of user accounts, and users can exchange locally an unlimited number of emails (with and without attachments) at high speed. For such local intranet communications, BMERS also provides a “chat” or instant messaging feature for real-time communications. Regarding long-distance communications, email messages addressed to locations outside of the LAN or WAN are sent by radio to a high-reliability WL2K server outside the disaster area. BMERS provides the gateway between the local hospital users and the Internet. The traffic through the local network flows at high speed, but the emails that go to or come from the Internet flow slowly due to limitations of the radio technology, as described below.

Email messages are automatically routed to and from the email accounts used directly by the local hospital command center users; therefore, no manual message routing by the operator is necessary. In contrast, the traditional amateur radio model described previously requires the operator of the WL2K radio to be on site to interact with users, copy emails from one system to another, and track all incoming and outgoing messages. The operator would also have to reroute messages as necessary when the staff of a hospital command center changed, whereas in the BMERS email system, users’ addresses are based on ICS roles and are in the address books of every user account. More importantly, automatic routing provides the freedom to move the radio system to an optimal operating location independent of the location of the hospital command center users. Efficient radio operation is highly dependent on the location of the radio equipment, especially the associated antennas.

Finally, BMERS can be operated remotely through a direct Wi-Fi connection. The radio system can be placed at an optimized location near the radio antennas, but the operators and its end users can be located in a more comfortable or protected location, which is particularly useful under inclement weather or other risky environmental conditions.

TECHNOLOGICAL LIMITATIONS

BMERS relies on the WL2K infrastructure available primarily in North America. In addition, it has a number of challenges that are inherent in amateur radio technology, as described in this section.

Antenna Placement

Placement of antennas is critical for any radio solution like BMERS. In many cases the ideal location for the radio equipment in a facility may be inadequate. Certain antennas must be kept close to the radio and other antennas require a large space for placement. For example, VHF and UHF antennas can be just a few feet long, but their efficient operation may require placement above the roof of a building. VHF and UHF operation typically reaches around 30 miles by using antennas that are practical for emergency deployment. Higher antenna placement and higher radio transmission power can extend this range. In contrast, HF radio can use the ionosphere to send signals to receivers hundreds of miles away. However, practical HF antennas with good propagation characteristics typically require wire antennas of 100 feet or longer at the frequencies of interest. Smaller antenna solutions exist, 32 but their efficiency can suffer from the reduced length.Reference Rauch 33 , 34 BMERS radio stations can be designed with a variety of portable antennas for different settings.

Radio Operating Skills

A trained and licensed radio operator familiar with radio equipment and the art of exploiting atmospheric radio propagation is required for BMERS. If the communications gap that needs to be bridged by radio signals is beyond the reach of VHF/UHF radio frequency bands, use of MF/HF bands (1 to 30 MHz) becomes necessary. BMERS is designed to operate on any of the bands allowed by amateur radio and the Army MARS service, but the vagaries of HF radio propagation require radio operators with training and experience beyond the casual amateur radio enthusiast. Although we collaborate with many amateur radio hobbyists who are highly skilled in HF bands and eager to help during crisis situations, their availability and commitment during actual disasters can be uncertain. For this reason, we also collaborate with experienced emergency communicators from Army MARS and local emergency communications organizations.

Radio Frequency Bandwidth Regulations and Physics

Current FCC regulations regarding “symbol rates” and bandwidth allowances for amateur radio communications only allow for very limited data throughput in HF/VHF/UHF bands. 35 Radio amateurs continue to develop and utilize new digital transmission modes that maximize symbol rate while conserving radio bandwidth, along with transmission modes that are effective even with low-power signals below the level of average background noise.Reference Taylor 36 - 38 However, physical and technological conditions such as atmospheric phenomena, transmission power, and electromagnetic interference limit the maximum information rate over a long-distance wireless channel on these bands. Practical limits are well below the maximum theoretical bandwidth (Nyquist-Shannon theorem).Reference Shannon 39 , Reference Nyquist 40 As a result, under the best conditions it is difficult to transmit more than a dozen pages of single-spaced text per minute using WL2K (see the section “BMERS Performance”). Indeed, the slow communications pathway in part justified the traditional WL2K model of using an operator to review each message before transmission. Unmanaged email, laden with graphics, copies of previous messages, or large attachments are not problematic on modern networks but can overwhelm the WL2K system. With very slow connection speeds, a single email with multimedia components or one requiring acknowledgment from multiple recipients would not only dominate the resource as outgoing mail but could trigger a backlog of replies that overload the available bandwidth. To address this danger of overload, BMERS software has usage-control mechanisms that reduce the likelihood of such an event. The system also has rescue techniques to resolve this problem if overload does occur. That enhanced bandwidth management feature eliminates the need for operator intervention in each message by enforcing restrictions on the size and overall volume of messages allowed through BMERS.

Data Protection

FCC regulations do not permit transmission of encrypted messages using the amateur radio service. However, Army MARS does not have such a restriction. Therefore, Army MARS message encryption tools can be used to protect the content of email messages transferred through BMERS when Army MARS frequencies are used (an authorization from Army MARS is required). In some jurisdictions, health organizations may be able to obtain access to other emergency communications radio frequencies that also allow data encryption.

BMERS PERFORMANCE

The time to send or receive an email via BMERS and WL2K is determined by the sum of link establishment time and transmission time. Link establishment is the process of getting the BMERS station into a conversation with the remote station that can reach the Internet. Transmission is the process of moving the awaiting email messages once the link is established. The rate at which BMERS handles both of these processes depends largely on factors that affect radio signal propagation: antenna type and location, chosen radio frequency, and atmospheric fluctuations that shift the way radio waves reflect off the ionosphere. The art of managing these factors depends on the radio operator’s experience. The operator’s options often depend on available resources (eg, safe antenna location) and the vagaries of weather patterns. We address this wide range of factors by testing throughput benchmarks across a wide range of operating conditions and across weak to robust propagation conditions. The benchmarks show that BMERS can handle on the order of 500 1-kB email messages per hour when UHF or VHF (UHF/VHF) frequency bands can be used. Beyond about 30 miles, the HF frequency band becomes the only option. In our hands, the HF band supports around 50 1-kB messages per hour. Under robust conditions, the delay between clicking “send” on the BMERS side and email arrival at its Internet destination is less than 1 minute via UHF/VHF and HF radio bands. However, HF is more susceptible to atmospheric conditions and service-related delays and therefore arrival time can increase to 2 minutes or more when HF bands are used. These times are dominated by the time required for link establishment. By rule (FCC and Army MARS) and by design, the radio communications link is established only when necessary to check for incoming mail or to transmit an outgoing message. Establishing a radio link can take from a few seconds to several minutes and often longer when HF bands are used. Once the link is established, practically any number of messages can be sent. Using UHF/VHF bands, for example, sending additional 1-kB messages adds only 5 to 10 s per message. Large messages can be sent when necessary. Our benchmarks show that a 100-kB image requires about 10 minutes to transmit through UHF/VHF bands. Under close-to-ideal conditions, the same 100-kB message can take a similar time via HF, but the usually longer time to establish a connection and larger influence of environmental conditions in the data throughput can extend the total transmission time through HF considerably, potentially up to 1 hour or more.

FIELD TESTS

One of the first tests of the portable version of BMERS was at the Collaborative Multiple-Agency Exercise (CMAX) in October 2009. Held at National Naval Medical Center (now called the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center) in Bethesda, Maryland, the exercise simulated an explosion at that facility that triggered a building collapse with multiple casualties. More than 5000 people were involved and BMERS was used during a simulated communications breakdown to keep the hospitals connected with the county emergency management agency. Other field exercises involving BMERS included simulating backup communications for an alternative Emergency Operations Center on the NIH campus and the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, and in demonstrations at full-scale exercises, such as CMAX/Capital Shield. Multiple demonstrations also have been conducted at NIH, Walter Reed Army Hospital, Fort McNair, Suburban Hospital–Johns Hopkins Medicine, emergency preparedness fairs, and other venues. Most recently, attendees at the “Sharing To Accelerate Research—Transformative Innovation for Development and Emergency Support” (STAR-TIDES, a project coordinated by the National Defense University) Annual Technology Demonstration at Fort McNair in Washington, DC, in September 2015 had an opportunity to gain first-hand experience with BMERS. A BMERS exercise is also held every year during the ARRL’s Field Day training exercise.Reference Ford 41 At that time, BMERS is deployed and operated using only emergency power from the Appalachian Mountains at Washington Monument State Park in Maryland. The medical staff who communicated with external entities (county emergency operations center, remote medical personnel, and others) via BMERS during drills had no difficulty maintaining communications during a simulated total communications outage. The staff used a standard laptop to connect wirelessly to their local BMERS station and successfully conducted communications activities with minimal support from the amateur radio operator managing the BMERS station. User feedback was collected after each deployment via interviews with the BMERS development team. The feedback was then incorporated in the subsequent version of the software as part of the engineering-testing cycle.

CONCLUSIONS

BMERS was developed to complement and augment the emergency communications resources of medical facilities and enable their incident management staff to remain connected during a catastrophic disaster. BMERS is not nearly as fast as typical Internet email, but when it becomes necessary to restore and maintain communications for the provision of health care services at a medical facility deeply affected by a major incident, a few minutes of turnaround time for brief messages are exactly what the doctor ordered. Medical organizations can use the BMERS software and involve their local amateur radio clubs in the development of this system in their facilities. Possible future enhancements to BMERS include expansion of the number of standard messaging forms built into the system and the ability to automatically encrypt transmissions for more secure messaging. The radio station equipment can also be made more portable and easy to deploy and operate, and the email accounts defined in the system can be adapted to other Incident Command positions and other roles, such as those needed for public health disaster response incidents. BMERS is under evaluation for use as a supplementary disaster communications resource by emergency management departments in Kent County and Carroll County in Maryland. Work is also underway to add BMERS servers to the Mid-Atlantic IP Network, a private amateur radio–supported microwave network in the Mid-Atlantic region intended to support emergency preparedness.Reference Mid-Atlantic 42

BMERS is a stable “product.” The software and hardware design are open source and free to use for noncommercial purposes. They can be obtained from the NIHRAC website at http://www.nihrac.org/home/bmers. Enhancements to improve ease of deployment, communications security, and overall system performance are under consideration. Meanwhile, the BMERS project team is focused on encouraging others to adopt and adapt the current system to their own needs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Department of the Navy, the National Naval Medical Center/Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, the Intramural Program of the National Institutes of Health, the NIH Radio Amateur Club, and the National Library of Medicine.