On March 11, 2011, at 1446, a 9-magnitude earthquake hit the coastal area of northern Japan, followed by a tsunami and an accident of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant (FDNPP).Reference Brumfiel and Cyranoski 1 - 6 This disaster comprised equipment failures, nuclear meltdowns, and release of radioactive materials, raising the possibility of health concerns in nearby residents. 6

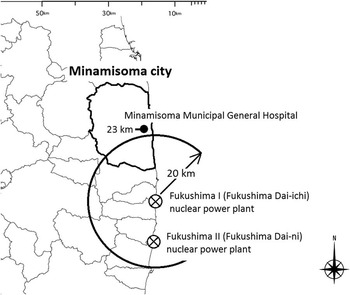

Minamisoma City is located north with distances from FDNPP to its southern and northern ends of 10 to 35 km, respectively (Figure 1). Before the earthquake, the population of Minamisoma City was 70,878 with 27% over the age of 65.Reference Muramatsu and Akiyama 7 The local death toll due to the earthquake and tsunami was 636 people. 8 Minamisoma Municipal General Hospital is the central hospital in this city. Before the earthquake, we usually treated 350 outpatients and 175 inpatients daily. Minamisoma Municipal General Hospital is the general hospital closest to FDNPP, located 23 km north of the plant (Figure 1). Before the earthquake, there were 16 departments, 4 wards, and 230 beds, with 13 full-time doctors, 164 nurses, and other medical staff. When the earthquake developed, 151 employees were working.

FIGURE 1 Locations of Minamisoma City, Our Hospital, and the Two Nuclear Electric Power Plants. Two nuclear electric power plants existed along the coastal area of Fukushima; the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plants (F1) and the Fukushima Daini Nuclear Power Plants (F2).

Construction of nuclear power plants has increased recently. They have been pointed to as potential targets of terrorism.Reference Bowen, Cottee and Hobbs 9 The risk from nuclear plant accidents seems to be elevated, as the World Nuclear Association has suggested. 10 However, little information is available on the effects of nuclear power plant accidents on local medical services in surrounding areas. We reviewed the operational issues of our hospital during the first 10 days after the earthquake and subsequent nuclear plant accident until completion of patient evacuation.

Methods

Participants

Participants included hospital staff and patients who were admitted to our hospital or came to our outpatient clinic between March 11 and 20, 2011.

Data Collection

Patients’ data were extracted from their medical records. Information on working conditions was collected by using hospital administrative records. Information on damages to the building and examination equipment was collected from the remaining recorded data. The hospital indoor and outdoor radiation measurements were collected from the data record. Factual information on the disaster was obtained from public access media.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the ethical review board of Minamisoma Municipal General Hospital (Study code: 24-12) and the Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo (Study code: 24-8-0606, 23-46-0113).

Results

Preparedness

Prior to the earthquake, we had a disaster plan with its targets including fires, tsunami, and earthquake, and we repeated regular training for injured individuals who were transferred to our hospital. Concerning nuclear disasters, how to treat irradiated individuals was a significant concern; however, we had never conducted an evacuation drill for nuclear disasters.

When the earthquake hit on March 11, the outpatient department was providing its usual services. We discontinued them promptly, initiating preparation for injured patients. No patients were in surgery or under artificial respiratory management. No patients in our hospital were injured directly due to the earthquake.

Several technological problems developed. Immediately after the earthquake, a power blackout occurred. The emergency power supply was activated. The water supply, sewer system, and oxygen supply operated normally. X-ray and radiation diagnostic equipment were out of service for 40 minutes. Computed tomography, blood count examination equipment, and biochemical analysis equipment were halted for 3 hours. All communication devices including telephone, cell phones, and internet access were not available until March 15. We did not receive any information on the nuclear plant accident from the public administration office of the central government. On March 12 at 2200, we set up a television, from which we obtained information on the accident.

Evacuation instructions from the central government and the hospital conditions are shown in Table 1. Until March 18, we had not received any information from the central government. Our information source was limited to television news. On March 16, the Mayor of Minamisoma City contacted the Japan Self Defense Forces (JSDF). Thereafter, we initiated evacuation with the support of JSDF.

TABLE 1 Timeline of Events and Condition of the Nuclear Plants and Our Hospital Following the Earthquake

a F1 Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant station.

b F2 Fukushima Daini Nuclear Power Plant station.

c Atomic reactor using MOX (mixed oxide fuels).

Outpatients

Many patients crowded the outpatient department after the earthquake, causing considerable confusion. Some medical records including triage tags were lost in the confusion, and we were not able to retrieve them. We could not confirm the number of patients with black tags who were transferred directly from the emergency room to the mortuary. Those with confirmed records were 659 patients, but the number of visits was 681 during the study period. The patients’ median age was 68 years (range, 0-104 years). The patients were 317 males and 342 females.

Causes of patient visits included chronic conditions (n=596), injury due to the earthquake or tsunami (n=39), cold syndrome (n=22), and trauma not related to the earthquake (n=4). Injury due to the earthquake or tsunami included drawing (n=30), amputation (n=2), fracture (n=2), crushing death/shock (n=1), pelvic fracture (n=2), and other fracture (n=2). Injury not related to the earthquake included traffic injury, bite wound, stroke, and cervical sprain.

Of the 596 patients with chronic conditions, 285 had visited our hospital regularly before the earthquake. The remaining 311 were transferred from other hospitals, because their family doctors evacuated. Their conditions included hypertension (n=210), diabetes (n=90), cardiovascular diseases (n=56), hyperlipidemia (n=53), cancer (n=44), cerebrovascular diseases (n=12), and psychiatric diseases (n=12), and 554 (84%) received regular prescriptions.

Among the 43 patients with injuries, 6 were in cardiopulmonary arrest on arrival. No visits related to radiation exposure were documented.

Patients obtained medicine from pharmacies outside our hospital before the earthquake. These pharmacies were closed, and stock delivery was disrupted between March 12 and 15. Patients were restricted to receiving only 3-day prescriptions at a time, which were provided by our hospital.

Hospitalized Patients

We treated 241 inpatients (Table 2) during the study period; 195 had been admitted prior to the disaster, and the remaining 46 were admitted after. The patients’ median age was 74 years (range, 0-95 years). Reasons for hospitalization included respiratory illness (n=40), cerebrovascular events (n=35), cancer (n=27), orthopedic cases (n=18), cardiovascular disease (n=13), pregnancy (n=10), neonatal illness (n=9), and others.

TABLE 2 Details of Admission, Discharge, and Transfer of Patients from 11 to 20 March 2011

a Everyone who was injured in the tsunami.

b Two patients were pregnant; one was injured in the tsunami.

c They were transferred to a medical facility 78 km away by using the hospital ambulance.

A total of 44 patients were newly admitted after the earthquake, comprising 18 males and 26 females. Their median age was 56 years (range, 0-92 years). Details were as follows: 26 were injured or nearly drowned in the tsunami, 4 were pregnant women, and 14 were other patients. Five died, all of whom were in the terminal phase. Owing to the difficulty in continuing routine medical care, we requested that patients who did not require continuous medical support be discharged. Among the remaining 238 patients, 134 were self-discharged or discharged with their families. The number of discharged patients on March 11 was 4, whereas 8 asked for self-discharge on the morning of March 12. The other 122 were discharged on the afternoon of March 12. The remaining 99 patients were transported to other facilities between March 12 and 20. The mean distance between our hospital and the designated hospital was 60 km (range, 56-348 km). No patients died during transfer. The priority of transfer was determined by attending physicians from March 12 to 17; however, the transfer itself was carried out pursuant to the evacuation instruction from the Mayor of Minamisoma City after March 18.

The transfer was assisted by the Disaster Medical Assistance Team (DMAT). However, DMAT stopped its activity on March 15 at 1100. Thereafter, patients who were transferred were handed over at the transit point, which was set up outside the 30-km range. The hospital ambulance and JSDF cars were used from the hospital to the transit point. DMAT was responsible for transfer from the transit point to the designated medical institutions. During transfer, several staff members who had stayed after the earthquake copied each patient’s data onto a CD-ROM, including a summary of their disease, examination data, and imaging data. The CD-ROM was sent to the transfer hospital with each patient.

Hospital Employees

Among the 254 employees, 1 nurse died in the earthquake. Six lost their families. The director of our hospital decided to hold regular meetings twice a day, beginning on March 14 at 0800.

On March 14 at 1100, FDNPP No. 3 exploded. Because this utilized plutonium and uranium fuel, the potential for health damages was initially thought to be severe. An employee emergency meeting was held on March 14 at 1130 to convey the message that employees could evacuate if they wished. Six doctors, 80 nurses, and 96 staff members evacuated. The number of employees was reduced from 239 pre-earthquake to 71. The remaining employees wore Tyvek suits (DuPont™ Tyvek®) as they worked after 1400 on March 14.

All of the 39 outsourced workers who were responsible for office work, cleaning, and meals left their jobs after March 14. Accordingly, the remaining medical staff had to fill these roles.

Supply of Goods

Medical and food supplies were completely disrupted; subsequently, drug wholesalers stopped delivering goods within a radius of 30-km. The first supply of goods arrived on March 16. After March 17, the goods requested by our hospital, such as water, food, medicines, fuel oil, and oxygen cylinders, were delivered by JSDF. However, food supplies were all regular food. Thus, the soft rice usually used for patients with dysphagia had to be reprocessed. Meals were prepared by nurses from the remaining ingredients available.

Response to Radioactivity

The first radioactivity level was measured by using a survey meter and the Geiger counter on March 12 at 1900. Radiologists conducted the radioactivity surveys. The level at the initial measurement was 20µSv/h, whereas at 2000, it was 12µSv/h. Indoor and outdoor fixed-point measurements were performed every hour after 2000 on March 12 (Figure 2). Results were shown on the message board in the outpatient clinic.

FIGURE 2 Changes in Radioactivity Levels in and Around the Hospital. From 1900 on March 12, 2011, the radioactivity level was measured every hour in and around the hospital. The outdoor level was measured on March 12 at 2000, and the maximum level was 12 μSv/h. We did not examine the inside levels. The minimum level was 0.25 μSv/h as measured on March 18 at 1500 and on March 20 at 0500, 0600, and 2300. The maximum difference between indoor and outdoor radiation levels was 7.7 μSv/h (outside 10.00-inside 2.30) on March 12 at 2243.

We conducted the internal exposure examination of 101 hospital employees from July to August 2011, and some data were reported previously. 6 , 11 Cesium-134 was detected from 24 hospital staff. The median body burden of cesium-134 was 16.7Bq/kg (range: 13.0 to 20.2Bq/kg). The committed effective dose, indicating the magnitude of health risks due to an intake of radioactive cesium-134 into the human body was calculated at under 1mSv among all the hospital staff.

DISCUSSION

This study showed that medical staff encountered a lack of human resources, material resources, and information after the nuclear accident such that it became difficult to maintain the health care provider system.

Lack of human resources was particularly significant. Approximately 70% of hospital employees chose to evacuate. Fear of radiation was not a major cause of their evacuation; rather, many employees were troubled with concern about their loved ones and work responsibilities, resulting in a decision to evacuate. These findings were comparable to those from a previous report on the Three Mile Island nuclear plant accident.Reference Maxwell 12

External support was limited. After the announcement to stay indoors within a 20- to 30-km radius from the plant by the government, DMAT voluntarily withdrew. There were concerns over the harmful effects of radioactive materials on health, in addition to unpredictable repeated critical situations. As a result, only JSDF provided assistance at this hospital.

Lack of material resources was another concern as supplies of medicine, food, and water stopped after the accident. Accordingly, administration of drugs to outpatient clinic patients was shortened, and meals were insufficient. This situation was comparable to previous reports on natural disasters, such as earthquakes or hurricanes.Reference Scanlon, McMahon and Haastert 13 However, there was a significant difference between natural disasters alone and those combined with nuclear accidents, because considerably more time was required until the delivery was resumed. Actually, delivery of supplies was resumed only on the fifth day after the earthquake. 14

To prevent these problems, it is important to provide fast and accurate information on the status of the plant and on the spread of radioactive materials. The spreading of radioactive materials depends on wind direction. Based on the spatial dose forecast information, the level around the hospital was actually lower than at other places located more than 30 km from the plant.Reference Katata, Terada and Nagai 15 Further, such knowledge could have been useful for the selection of evacuation areas and evacuation routes, which could have reduced the anxiety of the hospital staff.

Medical demands increased in the affected area after the earthquake. Among 618 outpatient clinic patients, 596 had chronic diseases. Of these, 311 had commuted to the surrounding clinics before the earthquake. Because the attending physicians at the surrounding clinics evacuated, these patients flooded this hospital for continuing their medical treatment. The number of patients including the 311 “new patients” was more than expected, and the stock of drugs was depleted faster than expected. Accordingly, the prescription period was restricted to less than 3 days. Such limitations on prescriptions can cause medication cessation, which might be related to worsening of conditions.Reference Tsubokura, Takita and Matsumura 16

Both patients and medical staff had significant concerns about irradiation. This study suggested that staying at the hospital was effective for reducing the external radiation dose of the hospital staff. The concrete reduced the spatial dose from outdoor concentration levels by one-fifth to as much as one-half because of the wall thickness.Reference Jacob and Meckbach 17 Keeping patients and employees inside the hospital as long as possible after the accident and away from highly contaminated areas can be useful in reducing the exposure amount.

Our study had several limitations. First, this was a single-center study; therefore, it should be interpreted with caution. This study was carried out in a developed country and in a region with an advancing elderly population. Therefore, we should be careful in applying the results of this study to developing countries with young populations.

CONCLUSIONS

Hospitals close to a damaged nuclear power plant may easily be isolated and may find it difficult to provide medical care. Especially, future nuclear-oriented disaster planning in hospitals should include action for shortage of manpower and the medical resources needed to address a minimum of 5 days of isolation.

Funding and Support

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 24792383.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the staff who have worked very hard in our hospital from immediately after the earthquake until the present. We would like to express our gratitude to the following: all the staff, Ms Minako Horiuchi, and Ms Yuuki Hamasu from Minamisoma Municipal General Hospital who helped us carry out all procedures in this study. Many nursing students and student doctors devoted themselves to data collection. We express sincere gratitude to Ms Natsumi Tsubura, Naoki Okada, Ms Manami Kohata, Takanori Honmura, Ms Natsumi Sasaki, Yuki Watanabe, Ms Miwa Uwadaira, Sho Shinoda, and Shu Hayakawa. Ms Sachiko Banba helped with recruiting nursing students and making arrangements for our schedules. Mr Tatsuya Ozaki from the World Children Foundation, Mr Yasuo Miyazawa, and all others from the foundation who supported this study. Mr Shuhei Nomura and Ms Amina Sugimoto who have provided technical information. Ms Kyoko Harada from the Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo, who helped with data collection; Ms Tomoyo Nishimura, Ms Zhu Xujin, Ms Noriko Miura, and everyone from our laboratory who helped with the office administration of the study. Finally, we thank everyone who has made it possible for this study to be carried out.